Submitted:

30 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

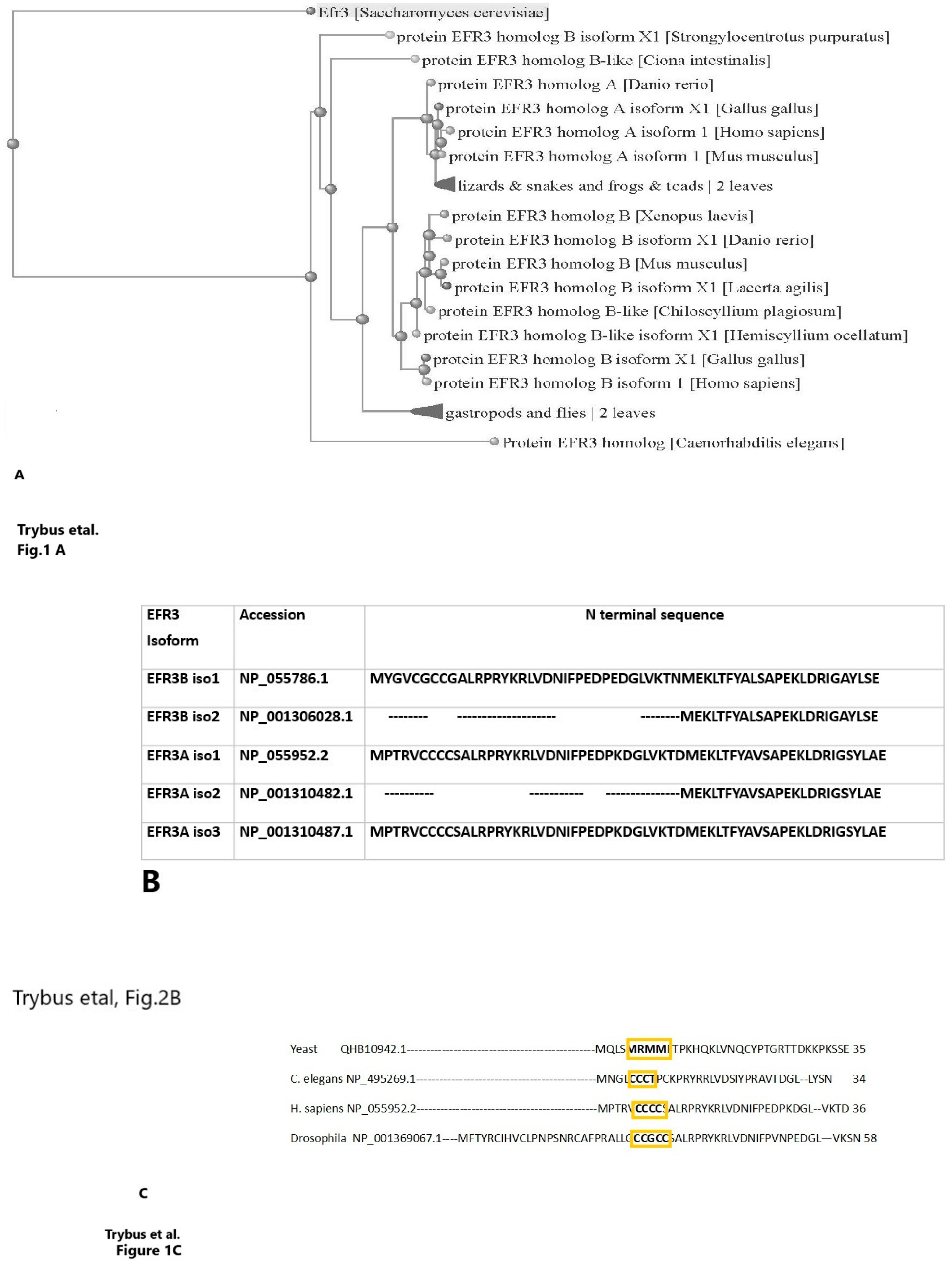

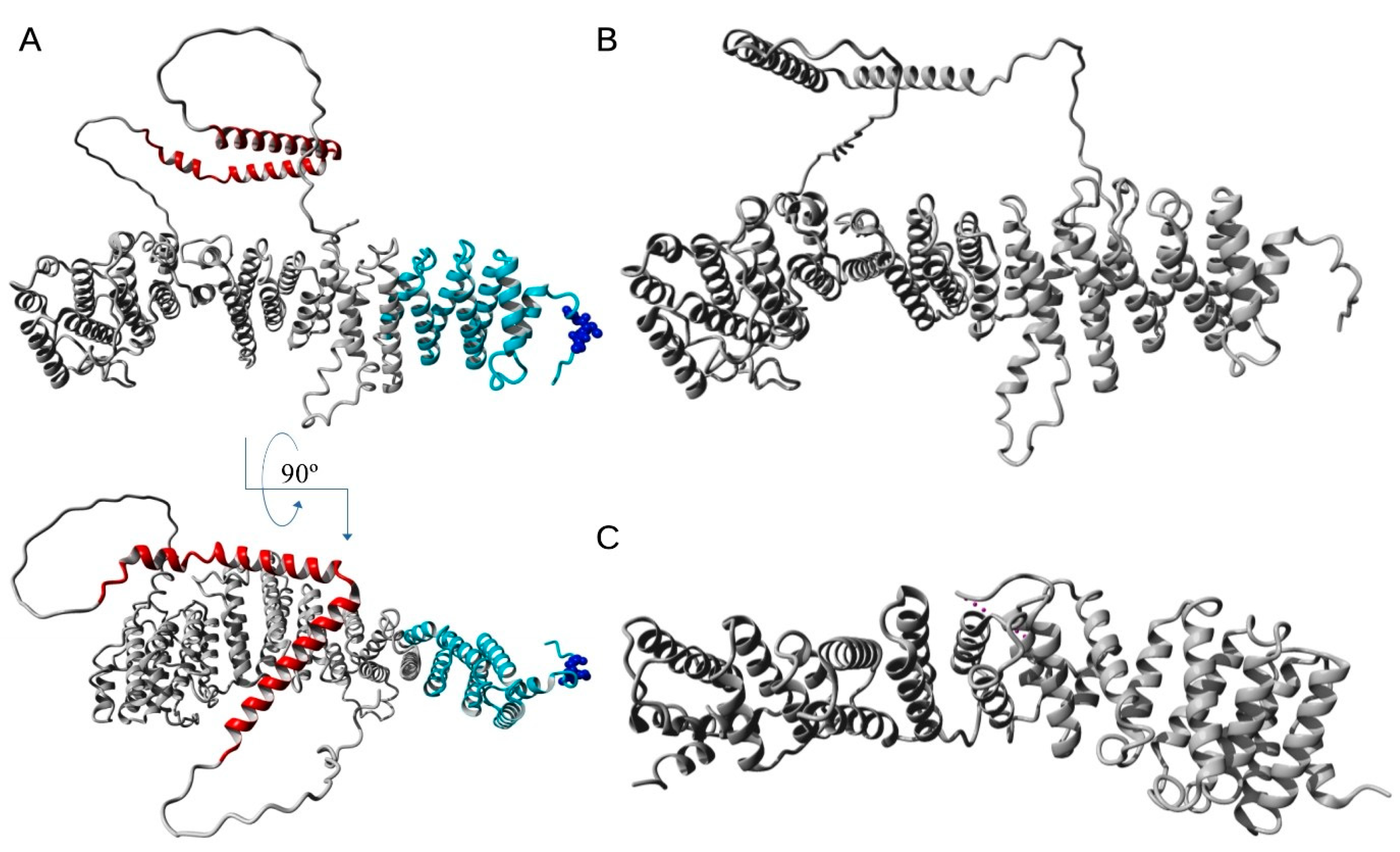

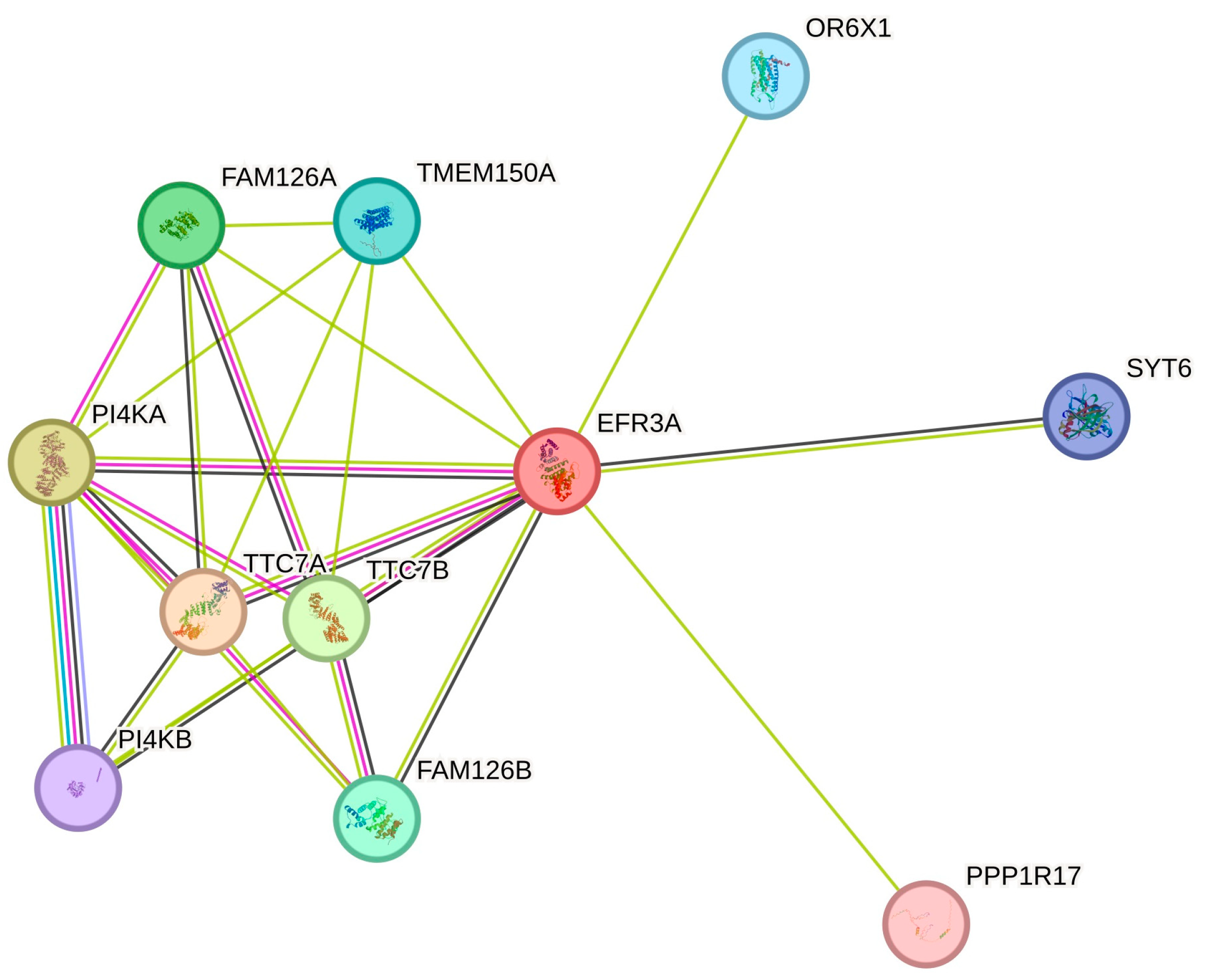

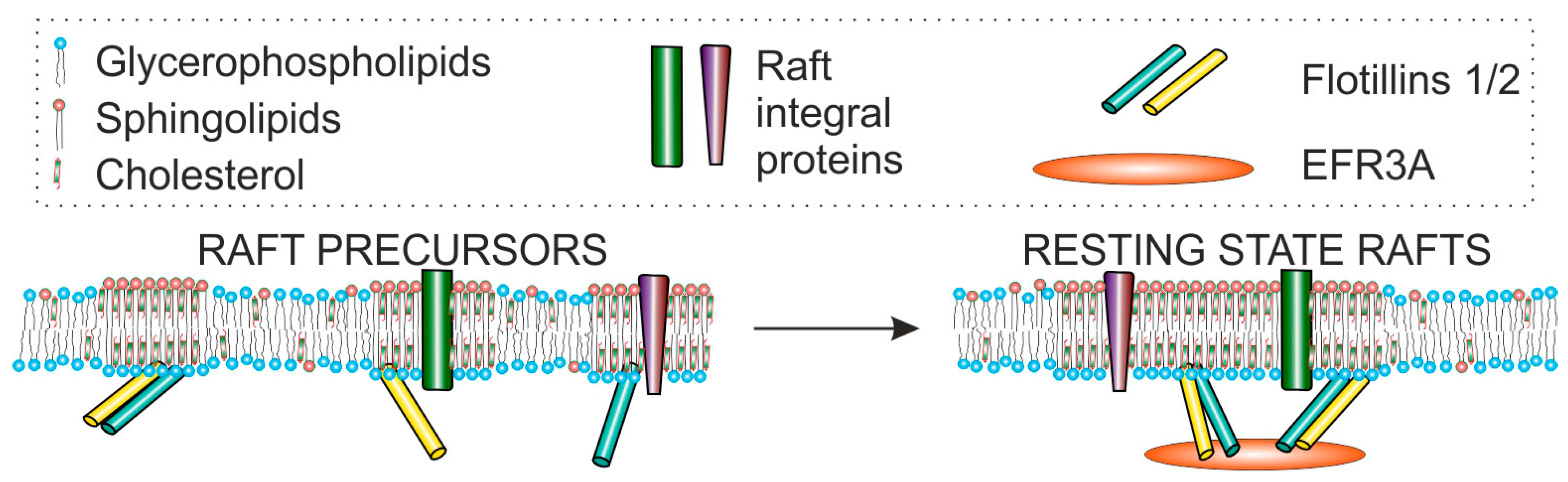

EFR3 (Eighty-Five Requiring 3) protein and its homologs are rather poorly understood eukaryotic plasma membrane peripheral proteins. They belong to the armadillo-like family of superhelical proteins. In higher vertebrates two paralog genes, A and B were found, each expressing at least 2-3 protein isoforms. EFR3s are involved in several physiological functions, mostly including phosphatidyl inositide phosphates, e.g. phototransduction (insects), GPCRs, and insulin receptors regulated processes (mammals). Mutations in the EFR3A were linked to several types of human disorders, i.e. neurological, cardiovascular, and several tumors. Structural data on the atomic level indicate the extended superhelical rod-like structure of the first two-thirds of the molecule with a typical armadillo repeat motif (ARM) in the N-terminal part and a triple helical motif in its C-terminal part. EFR3s' best-known molecular function is anchoring the giant phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase A complex to the plasma membrane crucial for cell signaling, also linked directly to the KRAS mutant oncogenic function. Another function connected to the newly uncovered interaction of EFR3A with flotillin-2 may be the participation of the former in the organization and regulation of the membrane raft domain. This review presents EFR3A as an intriguing subject of future studies.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Physiological Roles of EFR3A

2.1. Drosophila Melanogaster Phototransduction

2.2. EFR3 Proteins Affect GPCR Responsiveness by Regulating Receptor Phosphorylation

2.3. EFR3A and Insulin-Mediated Dispersal of GLUT4

2.4. Brain-Specific EFR3A Knock-Out Promotes Hippocampal Neurogenesis in Mice

3. Association of EFR3A Protein with Disease States

4. EFR3 Structural Features—Atomic Structure and Domain Organization

5. Post-Translational Modifications

5.1. S-Palmitoylation

5.2. Phosphorylation

5.3. Other Post-Translational Modifications

6. Functional Complexes

6.1. PI4K Anchoring in the Plasma Membrane

6.2. EFRA Possibly Plays a Role as Membrane Raft Organizer—Interaction with Flotillin-2

7. Concluding Remarks and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACS | acute coronary syndromes |

| ARM | armadillo |

| ASD | autism spectrum disorders |

| AT1R | angiotensin II receptor type 1 |

| BDNF | brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CAD | coronary artery disease |

| CID-MIA | combined immunodeficiency with multiple intestinal atresias |

| CRC | colorectal cancer |

| DAG | diacylglycerol |

| DRM | detergent-resistant membrane |

| EFR3A | eighty five requiring 3 |

| GPMVs | giant PM vesicles |

| IRV | insulin-responding vesicles |

| NPC | nasopharyngeal carcinoma |

| PDAC | pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma |

| PI(3,4,5)P3 | phosphatidyl inositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate |

| PI(4,5P)2 | phosphatidyl inositol (4,5)-bisphosphate |

| PI4KA | phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase alpha |

| PLCγ1 | phospholipase Cγ1 |

| PM | plasma membrane |

| SAD | Single-wavelength Anomalous Dispersion |

| SNP | single nucleotide polymorphism |

| TRP | transient receptor potential |

| TTC7 | tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7 |

References

- Lenburg, ME,O'Shea, EK, Genetic evidence for a morphogenetic function of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Pho85 cyclin-dependent kinase. Genetics. 2001. 157(1): p. 39-51. [CrossRef]

- Faulkner, DL, Dockendorff, TC,Jongens, TA, Clonal analysis of cmp44E, which encodes a conserved putative transmembrane protein, indicates a requirement for cell viability in Drosophila. Dev Genet. 1998. 23(4): p. 264-274. [CrossRef]

- Huang, FD, Woodruff, E, Mohrmann, R,Broadie, K, Rolling blackout is required for synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J Neurosci. 2006. 26(9): p. 2369-2379. [CrossRef]

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/protein/.

- https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/protein/UniProt/Q14156/entry/pfam/#table.

- Noack, LC, Bayle, V, Armengot, L, Rozier, F, Mamode-Cassim, A, Stevens, FD, Caillaud, MC, Munnik, T, Mongrand, S, Pleskot, RJaillais, Y, A nanodomain-anchored scaffolding complex is required for the function and localization of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase alpha in plants. Plant Cell. 2022. 34(1): p. 302-332. [CrossRef]

- AceView: a comprehensive cDNA-supported gene and transcripts annotation, GB, 7(Suppl 1):S12.

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/22979.

- Liu, CH, Bollepalli, MK, Long, SV, Asteriti, S, Tan, J, Brill, JA,Hardie, RC, Genetic dissection of the phosphoinositide cycle in Drosophila photoreceptors. J Cell Sci. 2018. 131(8). [CrossRef]

- Hardie, RC,Juusola, M, Phototransduction in Drosophila. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2015. 34: p. 37-45. [CrossRef]

- Montell, C, Drosophila visual transduction. Trends Neurosci. 2012. 35(6): p. 356-363. [CrossRef]

- Hardie, RC, Liu, CH, Randall, AS,Sengupta, S, In vivo tracking of phosphoinositides in Drosophila photoreceptors. J Cell Sci. 2015. 128(23): p. 4328-4340. [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, SS, Basu, U, Shinde, D, Thakur, R, Jaiswal, M,Raghu, P, Regulation of PI4P levels by PI4KIIIalpha during G-protein-coupled PLC signaling in Drosophila photoreceptors. J Cell Sci. 2018. 131(15).

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/datasets/gene/id/23167.

- Vijayakrishnan, N, Phillips, SE,Broadie, K, Drosophila rolling blackout displays lipase domain-dependent and -independent endocytic functions downstream of dynamin. Traffic. 2010. 11(12): p. 1567-1578. [CrossRef]

- Bojjireddy, N, Guzman-Hernandez, ML, Reinhard, NR, Jovic, M,Balla, T, EFR3s are palmitoylated plasma membrane proteins that control responsiveness to G-protein-coupled receptors. J Cell Sci. 2015. 128(1): p. 118-128. [CrossRef]

- Gironacci, MM,Bruna-Haupt, E, Unraveling the crosstalk between renin-angiotensin system receptors. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2024. 240(5): p. e14134. [CrossRef]

- Forrester, SJ, Booz, GW, Sigmund, CD, Coffman, TM, Kawai, T, Rizzo, V, Scalia, R,Eguchi, S, Angiotensin II Signal Transduction: An Update on Mechanisms of Physiology and Pathophysiology. Physiol Rev. 2018. 98(3): p. 1627-1738. [CrossRef]

- Guo, DF, Sun, YL, Hamet, P,Inagami, T, The angiotensin II type 1 receptor and receptor-associated proteins. Cell Res. 2001. 11(3): p. 165-180. [CrossRef]

- Nadel, G, Yao, Z, Hacohen-Lev-Ran, A, Wainstein, E, Maik-Rachline, G, Ziv, T, Naor, Z, Admon, A,Seger, R, Phosphorylation of PP2Ac by PKC is a key regulatory step in the PP2A-switch-dependent AKT dephosphorylation that leads to apoptosis. Cell Commun Signal. 2024. 22(1): p. 154. [CrossRef]

- Streb, H, Irvine, RF, Berridge, MJ,Schulz, I, Release of Ca2+ from a nonmitochondrial intracellular store in pancreatic acinar cells by inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate. Nature. 1983. 306(5938): p. 67-69. [CrossRef]

- van Gerwen, J, Shun-Shion, AS,Fazakerley, DJ, Insulin signalling and GLUT4 trafficking in insulin resistance. Biochem Soc Trans. 2023. 51(3): p. 1057-1069. [CrossRef]

- Bogan, JS, Regulation of glucose transporter translocation in health and diabetes. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012. 81: p. 507-532. [CrossRef]

- Geiser, A, Foylan, S, Tinning, PW, Bryant, NJ,Gould, GW, GLUT4 dispersal at the plasma membrane of adipocytes: a super-resolved journey. Biosci Rep. 2023. 43(10). [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y, Jaldin-Fincati, J, Liu, Z, Bilan, PJ,Klip, A, A complex of Rab13 with MICAL-L2 and alpha-actinin-4 is essential for insulin-dependent GLUT4 exocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2016. 27(1): p. 75-89. [CrossRef]

- Stenkula, KG, Lizunov, VA, Cushman, SW,Zimmerberg, J, Insulin controls the spatial distribution of GLUT4 on the cell surface through regulation of its postfusion dispersal. Cell Metab. 2010. 12(3): p. 250-259. [CrossRef]

- Wieczorke, R, Dlugai, S, Krampe, S,Boles, E, Characterisation of mammalian GLUT glucose transporters in a heterologous yeast expression system. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2003. 13(3): p. 123-134. [CrossRef]

- Boles, E,Oreb, M, A Growth-Based Screening System for Hexose Transporters in Yeast. Methods Mol Biol. 2018. 1713: p. 123-135.

- Schmidl, S, Tamayo Rojas, SA, Iancu, CV, Choe, JY,Oreb, M, Functional Expression of the Human Glucose Transporters GLUT2 and GLUT3 in Yeast Offers Novel Screening Systems for GLUT-Targeting Drugs. Front Mol Biosci. 2020. 7: p. 598419. [CrossRef]

- Koester, AM, Geiser, A, Laidlaw, KME, Morris, S, Cutiongco, MFA, Stirrat, L, Gadegaard, N, Boles, E, Black, HL, Bryant, NJGould, GW, EFR3 and phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha regulate insulin-stimulated glucose transport and GLUT4 dispersal in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Biosci Rep. 2022. 42(7).

- Koester, AM, Geiser, A, Bowman, PRT, van de Linde, S, Gadegaard, N, Bryant, NJ,Gould, GW, GLUT4 translocation and dispersal operate in multiple cell types and are negatively correlated with cell size in adipocytes. Sci Rep. 2022. 12(1): p. 20535. [CrossRef]

- Qian, Q, Liu, Q, Zhou, D, Pan, H, Liu, Z, He, F, Ji, S, Wang, D, Bao, W, Liu, X et al., Brain-specific ablation of Efr3a promotes adult hippocampal neurogenesis via the brain-derived neurotrophic factor pathway. FASEB J. 2017. 31(5): p. 2104-2113. [CrossRef]

- Nie, C, Hu, H, Shen, C, Ye, B, Wu, H,Xiang, M, Expression of EFR3A in the mouse cochlea during degeneration of spiral ganglion following hair cell loss. PLoS One. 2015. 10(1): p. e0117345. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H, Ma, Y, Ye, B, Wang, Q, Yang, T, Lv, J, Shi, J, Wu, H,Xiang, M, The role of Efr3a in age-related hearing loss. Neuroscience. 2017. 341: p. 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Hu, H, Ye, B, Zhang, L, Wang, Q, Liu, Z, Ji, S, Liu, Q, Lv, J, Ma, Y, Xu, Y et al., Efr3a Insufficiency Attenuates the Degeneration of Spiral Ganglion Neurons after Hair Cell Loss. Front Mol Neurosci. 2017. 10: p. 86. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, AR, Pirruccello, M, Cheng, F, Kang, HJ, Fernandez, TV, Baskin, JM, Choi, M, Liu, L, Ercan-Sencicek, AG, Murdoch, JD et al., Rare deleterious mutations of the gene EFR3A in autism spectrum disorders. Mol Autism. 2014. 5: p. 31. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K, Bai, X, Wang, X, Cao, Y, Zhang, L, Li, W,Wang, S, Insight on the hub gene associated signatures and potential therapeutic agents in epilepsy and glioma. Brain Res Bull. 2023. 199: p. 110666. [CrossRef]

- He, Y, Wei, M, Wu, Y, Qin, H, Li, W, Ma, X, Cheng, J, Ren, J, Shen, Y, Chen, Z et al., Amyloid beta oligomers suppress excitatory transmitter release via presynaptic depletion of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. Nat Commun. 2019. 10(1): p. 1193.

- Wei, X, Wang, J, Yang, E, Zhang, Y, Qian, Q, Li, X, Huang, F,Sun, B, Efr3b is essential for social recognition by modulating the excitability of CA2 pyramidal neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024. 121(3): p. e2314557121. [CrossRef]

- Sun, J, Shen, C, Jin, X, Li, X, and Wu, D. , Mir-367 is downregulated in coronary artery disaese and its overexpression exerts anti-inflammatory effect via inhibition of the NF- κB-activated inflammatory pathway. . International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Patholology 2017. 10(4): p. 4047-4057.

- Liu X, XH, Xu H, Geng Q, Mak W-H, Ling F, Su Z, Yang F, Zhang T, Chen J, Yang H, Wang J, Zhang X, Xu X, Jia H, Zhang Z, Liu X, and Zhong S. , New genetic variants associated with major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with acute coronary syndromes and treated with clopidogrel and aspirin. Pharmacogen. J. 2021. 21(6): p. 664-672.

- Zhou, D, Yang, L, Zheng, L, Ge, W, Li, D, Zhang, Y, Hu, X, Gao, Z, Xu, J, Huang, Y et al., Exome capture sequencing of adenoma reveals genetic alterations in multiple cellular pathways at the early stage of colorectal tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2013. 8(1): p. e53310. [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, H, Kattan, WE, Kumar, S, Zhou, P, Hancock, JF,Counter, CM, Oncogenic KRAS is dependent upon an EFR3A-PI4KA signaling axis for potent tumorigenic activity. Nat Commun. 2021. 12(1): p. 5248. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J, KRAS mutation in pancreatic cancer. Semin Oncol. 2021. 48(1): p. 10-18. [CrossRef]

- Kattan, WE, Liu, J, Montufar-Solis, D, Liang, H, Brahmendra Barathi, B, van der Hoeven, R, Zhou, Y,Hancock, JF, Components of the phosphatidylserine endoplasmic reticulum to plasma membrane transport mechanism as targets for KRAS inhibition in pancreatic cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021. 118(51). [CrossRef]

- Yang, J, Gong, Y, Jiang, Q, Liu, L, Li, S, Zhou, Q, Huang, F,Liu, Z, Circular RNA Expression Profiles in Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma by Sequence Analysis. Front Oncol. 2020. 10: p. 601. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P,Xia, B, Circular RNA EFR3A promotes nasopharyngeal carcinoma progression through modulating the miR-654-3p/EFR3A axis. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2023. 69(12): p. 111-117. [CrossRef]

- Conn, VM, Chinnaiyan, AM,Conn, SJ, Circular RNA in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2024. Online ahead of print.

- Toledo, CM, Ding, Y, Hoellerbauer, P, Davis, RJ, Basom, R, Girard, EJ, Lee, E, Corrin, P, Hart, T, Bolouri, H et al., Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 Screens Reveal Loss of Redundancy between PKMYT1 and WEE1 in Glioblastoma Stem-like Cells. Cell Rep. 2015. 13(11): p. 2425-2439. [CrossRef]

- Hoellerbauer, P, Biery, MC, Arora, S, Rao, Y, Girard, EJ, Mitchell, K, Dighe, P, Kufeld, M, Kuppers, DA, Herman, JA et al., Functional genomic analysis of adult and pediatric brain tumor isolates. bioRxiv. 2023.

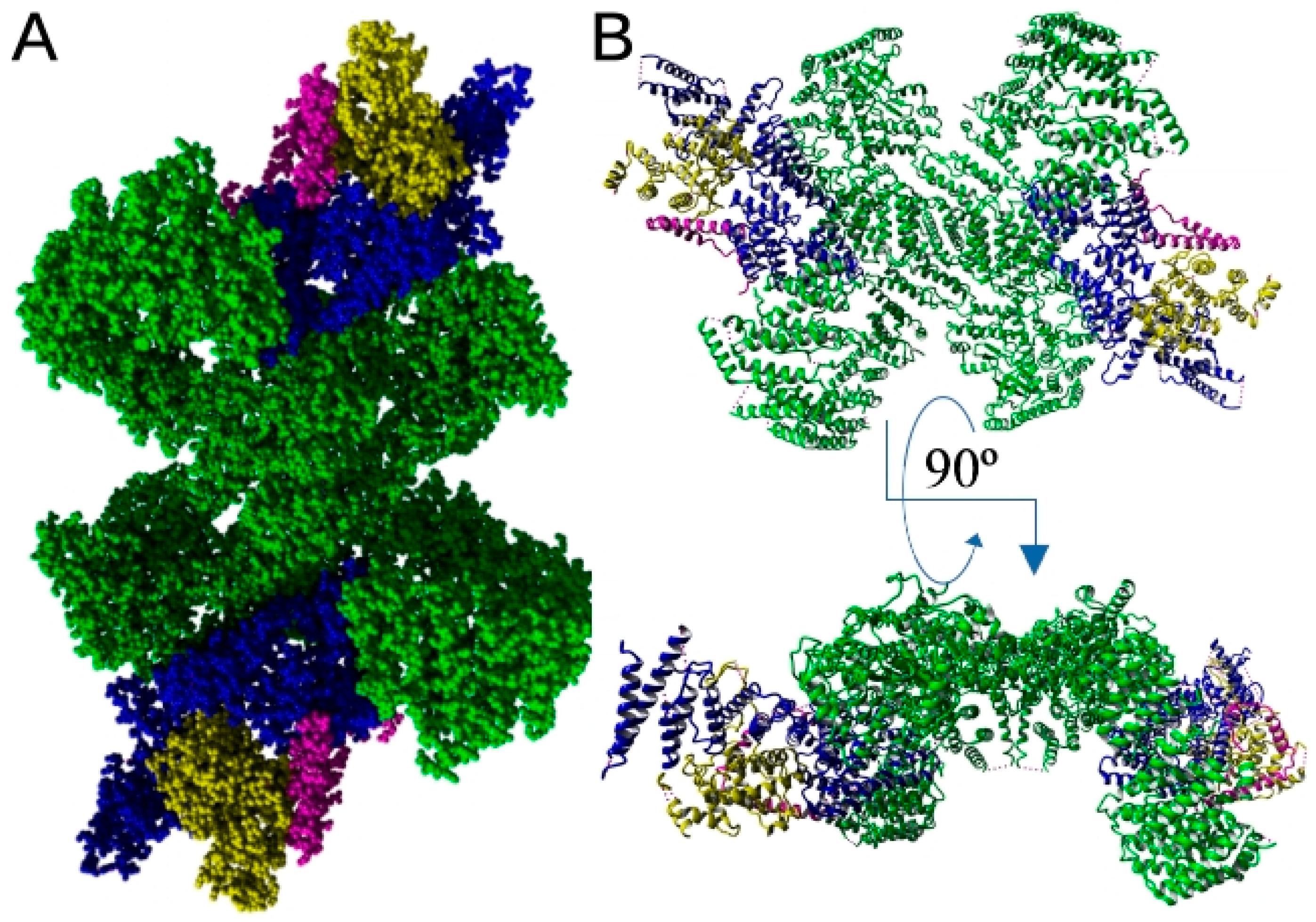

- Wu, X, Chi, RJ, Baskin, JM, Lucast, L, Burd, CG, De Camilli, P,Reinisch, KM, Structural insights into assembly and regulation of the plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase complex. Dev Cell. 2014. 28(1): p. 19-29. [CrossRef]

- Misra, S, Beach, BM,Hurley, JH, Structure of the VHS domain of human Tom1 (target of myb 1): insights into interactions with proteins and membranes. Biochemistry. 2000. 39(37): p. 11282-11290. [CrossRef]

- Boal, F, Mansour, R, Gayral, M, Saland, E, Chicanne, G, Xuereb, JM, Marcellin, M, Burlet-Schiltz, O, Sansonetti, PJ, Payrastre, BTronchere, H, TOM1 is a PI5P effector involved in the regulation of endosomal maturation. J Cell Sci. 2015. 128(4): p. 815-827. [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y, Nickitenko, A, Duan, X, Lloyd, TE, Wu, MN, Bellen, H,Quiocho, FA, Crystal structure of the VHS and FYVE tandem domains of Hrs, a protein involved in membrane trafficking and signal transduction. Cell. 2000. 100(4): p. 447-456. [CrossRef]

- https://doi.org/10.2210/pdb1ELK/pdb.

- Lohi, O, Poussu, A, Mao, Y, Quiocho, F,Lehto, VP, VHS domain -- a longshoreman of vesicle lines. FEBS Lett. 2002. 513(1): p. 19-23.

- Andrade, MA, Petosa, C, O'Donoghue, SI, Muller, CW,Bork, P, Comparison of ARM and HEAT protein repeats. J Mol Biol. 2001. 309(1): p. 1-18. [CrossRef]

- (http://pfam.xfam.org/).

- Kippert, F,Gerloff, DL, Highly sensitive detection of individual HEAT and ARM repeats with HHpred and COACH. PLoS One. 2009. 4(9): p. e7148. [CrossRef]

- Baskin, JM, Wu, X, Christiano, R, Oh, MS, Schauder, CM, Gazzerro, E, Messa, M, Baldassari, S, Assereto, S, Biancheri, R et al., The leukodystrophy protein FAM126A (hyccin) regulates PtdIns(4)P synthesis at the plasma membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2016. 18(1): p. 132-138. [CrossRef]

- Lees, JA, Zhang, Y, Oh, MS, Schauder, CM, Yu, X, Baskin, JM, Dobbs, K, Notarangelo, LD, De Camilli, P, Walz, TReinisch, KM, Architecture of the human PI4KIIIalpha lipid kinase complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. 114(52): p. 13720-13725.

- Suresh, S, Shaw, AL, Pemberton, JG, Scott, MK, Harris, NJ, Parson, MA, Jenkins, ML, Rohilla, P, Alejandro Alvarez, P, Balla, T et al., Molecular basis for plasma membrane recruitment of PI4KA by EFR3. bioRxiv. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Suresh, S, Shaw, AL, Pemberton, JG, Scott, MK, Harris, NJ, Parson, MAH, Jenkins, ML, Rohilla, P, Alvarez-Prats, A, Balla, T et al., Molecular basis for plasma membrane recruitment of PI4KA by EFR3. Sci Adv. 2024. 10(51): p. eadp6660. [CrossRef]

- Korycka, J, Lach, A, Heger, E, Boguslawska, DM, Wolny, M, Toporkiewicz, M, Augoff, K, Korzeniewski, J,Sikorski, AF, Human DHHC proteins: a spotlight on the hidden player of palmitoylation. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012. 91(2): p. 107-117. [CrossRef]

- Tabaczar, S, Czogalla, A, Podkalicka, J, Biernatowska, A,Sikorski, AF, Protein palmitoylation: Palmitoyltransferases and their specificity. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017. 242(11): p. 1150-1157. [CrossRef]

- Pei, S,Piao, HL, Exploring Protein S-Palmitoylation: Mechanisms, Detection, and Strategies for Inhibitor Discovery. ACS Chem Biol. 2024. 19(9): p. 1868-1882.

- Ren, J, Wen, L, Gao, X, Jin, C, Xue, Y,Yao, X, CSS-Palm 2.0: an updated software for palmitoylation sites prediction. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2008. 21(11): p. 639-644. [CrossRef]

- Blanc, M, David, FPA,van der Goot, FG, SwissPalm 2: Protein S-Palmitoylation Database. Methods Mol Biol. 2019. 2009: p. 203-214.

- Batrouni, AG, Bag, N, Phan, HT, Baird, BA,Baskin, JM, A palmitoylation code controls PI4KIIIalpha complex formation and PI(4,5)P2 homeostasis at the plasma membrane. J Cell Sci. 2022. 135(5).

- Nakatsu, F, Baskin, JM, Chung, J, Tanner, LB, Shui, G, Lee, SY, Pirruccello, M, Hao, M, Ingolia, NT, Wenk, MRDe Camilli, P, PtdIns4P synthesis by PI4KIIIalpha at the plasma membrane and its impact on plasma membrane identity. J Cell Biol. 2012. 199(6): p. 1003-1016.

- Hornbeck, PV, Zhang, B, Murray, B, Kornhauser, JM, Latham, V,Skrzypek, E, PhosphoSitePlus, 2014: mutations, PTMs and recalibrations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015. 43(Database issue): p. D512-520. [CrossRef]

- https://string-db.org/.

- Roux, KJ, Kim, DI, Burke, B,May, DG, BioID: A Screen for Protein-Protein Interactions. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2018. 91: p. 19 23 11-19 23 15. [CrossRef]

- Dong, JM, Tay, FP, Swa, HL, Gunaratne, J, Leung, T, Burke, B,Manser, E, Proximity biotinylation provides insight into the molecular composition of focal adhesions at the nanometer scale. Sci Signal. 2016. 9(432): p. rs4. [CrossRef]

- Falkenburger, BH, Jensen, JB, Dickson, EJ, Suh, BC,Hille, B, Phosphoinositides: lipid regulators of membrane proteins. J Physiol. 2010. 588(Pt 17): p. 3179-3185. [CrossRef]

- Katan, M,Cockcroft, S, Phosphatidylinositol(4,5)bisphosphate: diverse functions at the plasma membrane. Essays Biochem. 2020. 64(3): p. 513-531. [CrossRef]

- Audhya, A,Emr, SD, Stt4 PI 4-kinase localizes to the plasma membrane and functions in the Pkc1-mediated MAP kinase cascade. Dev Cell. 2002. 2(5): p. 593-605. [CrossRef]

- Posor, Y, Jang, W,Haucke, V, Phosphoinositides as membrane organizers. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022. 23(12): p. 797-816. [CrossRef]

- Ray, J, Sapp, DG,Fairn, GD, Phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate: Out of the shadows and into the spotlight. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2024. 88: p. 102372. [CrossRef]

- Hammond, GR, Machner, MP,Balla, T, A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J Cell Biol. 2014. 205(1): p. 113-126. [CrossRef]

- Salazar, AN, Gorter de Vries, AR, van den Broek, M, Wijsman, M, de la Torre Cortes, P, Brickwedde, A, Brouwers, N, Daran, JG,Abeel, T, Nanopore sequencing enables near-complete de novo assembly of Saccharomyces cerevisiae reference strain CEN.PK113-7D. FEMS Yeast Res. 2017. 17(7). [CrossRef]

- Wong, K,Cantley, LC, Cloning and characterization of a human phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase. J Biol Chem. 1994. 269(46): p. 28878-28884. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S, Ohya, Y, Goebl, M, Nakano, A,Anraku, Y, A novel gene, STT4, encodes a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase in the PKC1 protein kinase pathway of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1994. 269(2): p. 1166-1172. [CrossRef]

- Cutler, NS, Heitman, J,Cardenas, ME, STT4 is an essential phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase that is a target of wortmannin in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1997. 272(44): p. 27671-27677. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rodas, R, Labbaoui, H, Orange, F, Solis, N, Zaragoza, O, Filler, SG, Bassilana, M,Arkowitz, RA, Plasma Membrane Phosphatidylinositol-4-Phosphate Is Not Necessary for Candida albicans Viability yet Is Key for Cell Wall Integrity and Systemic Infection. mBio. 2021. 13(1): p. e0387321.

- Scheufler, C, Brinker, A, Bourenkov, G, Pegoraro, S, Moroder, L, Bartunik, H, Hartl, FU,Moarefi, I, Structure of TPR domain-peptide complexes: critical elements in the assembly of the Hsp70-Hsp90 multichaperone machine. Cell. 2000. 101(2): p. 199-210.

- Izert, MA, Szybowska, PE, Gorna, MW,Merski, M, The Effect of Mutations in the TPR and Ankyrin Families of Alpha Solenoid Repeat Proteins. Front Bioinform. 2021. 1: p. 696368. [CrossRef]

- Baird, D, Stefan, C, Audhya, A, Weys, S,Emr, SD, Assembly of the PtdIns 4-kinase Stt4 complex at the plasma membrane requires Ypp1 and Efr3. J Cell Biol. 2008. 183(6): p. 1061-1074. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, NS, Northrop, L, Anyane-Yeboa, K, Aggarwal, VS, Nagy, PL,Demirdag, YY, Tetratricopeptide repeat domain 7A (TTC7A) mutation in a newborn with multiple intestinal atresia and combined immunodeficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2014. 34(6): p. 607-610. [CrossRef]

- Jardine, S, Dhingani, N,Muise, AM, TTC7A: Steward of Intestinal Health. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019. 7(3): p. 555-570. [CrossRef]

- Sharafian, S, Alimadadi, H, Shahrooei, M, Gharagozlou, M, Aghamohammadi, A,Parvaneh, N, A Novel TTC7A Deficiency Presenting With Combined Immunodeficiency and Chronic Gastrointestinal Problems. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2018. 28(5): p. 358-360. [CrossRef]

- Mou, W, Yang, S, Guo, R, Fu, L, Zhang, L, Guo, W, Du, J, He, J, Ren, Q, Hao, C et al., A Novel Homozygous TTC7A Missense Mutation Results in Familial Multiple Intestinal Atresia and Combined Immunodeficiency. Front Immunol. 2021. 12: p. 759308. [CrossRef]

- Dannheim, K, Ouahed, J, Field, M, Snapper, S, Raphael, BP, Glover, SC, Bishop, PR, Bhesania, N, Kamin, D, Thiagarajah, JGoldsmith, JD, Pediatric Gastrointestinal Histopathology in Patients With Tetratricopeptide Repeat Domain 7A (TTC7A) Germline Mutations: A Rare Condition Leading to Multiple Intestinal Atresias, Severe Combined Immunodeficiency, and Congenital Enteropathy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2022. 46(6): p. 846-853.

- https://www.malacards.org/card/hypomyelinating_leukoencephalopathy.

- Gazzerro, E, Baldassari, S, Giacomini, C, Musante, V, Fruscione, F, La Padula, V, Biancheri, R, Scarfi, S, Prada, V, Sotgia, F et al., Hyccin, the molecule mutated in the leukodystrophy hypomyelination and congenital cataract (HCC), is a neuronal protein. PLoS One. 2012. 7(3): p. e32180. [CrossRef]

- Traverso, M, Yuregir, OO, Mimouni-Bloch, A, Rossi, A, Aslan, H, Gazzerro, E, Baldassari, S, Fruscione, F, Minetti, C, Zara, FBiancheri, R, Hypomyelination and congenital cataract: identification of novel mutations in two unrelated families. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013. 17(1): p. 108-111. [CrossRef]

- Li, S,Han, T, Frequent loss of FAM126A expression in colorectal cancer results in selective FAM126B dependency. iScience. 2024. 27(5): p. 109646. [CrossRef]

- Dornan, GL, Dalwadi, U, Hamelin, DJ, Hoffmann, RM, Yip, CK,Burke, JE, Probing the Architecture, Dynamics, and Inhibition of the PI4KIIIalpha/TTC7/FAM126 Complex. J Mol Biol. 2018. 430(18 Pt B): p. 3129-3142.

- Chung, J, Nakatsu, F, Baskin, JM,De Camilli, P, Plasticity of PI4KIIIalpha interactions at the plasma membrane. EMBO Rep. 2015. 16(3): p. 312-320.

- Simons, K,Ikonen, E, Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997. 387(6633): p. 569-572. [CrossRef]

- Sezgin, E, Levental, I, Mayor, S,Eggeling, C, The mystery of membrane organization: composition, regulation and roles of lipid rafts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017. 18(6): p. 361-374. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Z,Hansen, SB, Cholesterol Regulation of Membrane Proteins Revealed by Two-Color Super-Resolution Imaging. Membranes (Basel). 2023. 13(2). [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, KGN,Kusumi, A, Refinement of Singer-Nicolson fluid-mosaic model by microscopy imaging: Lipid rafts and actin-induced membrane compartmentalization. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2023. 1865(2): p. 184093. [CrossRef]

- Saldana-Villa, AK,Lara-Lemus, R, The Structural Proteins of Membrane Rafts, Caveolins and Flotillins, in Lung Cancer: More Than Just Scaffold Elements. Int J Med Sci. 2023. 20(13): p. 1662-1670. [CrossRef]

- Neumann-Giesen, C, Falkenbach, B, Beicht, P, Claasen, S, Luers, G, Stuermer, CA, Herzog, V,Tikkanen, R, Membrane and raft association of reggie-1/flotillin-2: role of myristoylation, palmitoylation and oligomerization and induction of filopodia by overexpression. Biochem J. 2004. 378(Pt 2): p. 509-518. [CrossRef]

- Fantini, J,Barrantes, FJ, How cholesterol interacts with membrane proteins: an exploration of cholesterol-binding sites including CRAC, CARC, and tilted domains. Front Physiol. 2013. 4: p. 31. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, KGN, Single-Molecule Imaging of Ganglioside Probes in Living Cell Plasma Membranes. Methods Mol Biol. 2023. 2613: p. 215-227.

- Komatsuya, K, Kikuchi, N, Hirabayashi, T,Kasahara, K, The Regulatory Roles of Cerebellar Glycosphingolipid Microdomains/Lipid Rafts. Int J Mol Sci. 2023. 24(6). [CrossRef]

- Ruzzi, F, Cappello, C, Semprini, MS, Scalambra, L, Angelicola, S, Pittino, OM, Landuzzi, L, Palladini, A, Nanni, P,Lollini, PL, Lipid rafts, caveolae, and epidermal growth factor receptor family: friends or foes? Cell Commun Signal. 2024. 22(1): p. 489.

- Isik, OA,Cizmecioglu, O, Rafting on the Plasma Membrane: Lipid Rafts in Signaling and Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023. 1436: p. 87-108.

- Shouman, S, El-Kholy, N, Hussien, AE, El-Derby, AM, Magdy, S, Abou-Shanab, AM, Elmehrath, AO, Abdelwaly, A, Helal, M,El-Badri, N, SARS-CoV-2-associated lymphopenia: possible mechanisms and the role of CD147. Cell Commun Signal. 2024. 22(1): p. 349.

- Teixeira, L, Temerozo, JR, Pereira-Dutra, FS, Ferreira, AC, Mattos, M, Goncalves, BS, Sacramento, CQ, Palhinha, L, Cunha-Fernandes, T, Dias, SSG et al., Simvastatin Downregulates the SARS-CoV-2-Induced Inflammatory Response and Impairs Viral Infection Through Disruption of Lipid Rafts. Front Immunol. 2022. 13: p. 820131.

- Zhang, S, Zhu, N, Li, HF, Gu, J, Zhang, CJ, Liao, DF,Qin, L, The lipid rafts in cancer stem cell: a target to eradicate cancer. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022. 13(1): p. 432. [CrossRef]

- Erazo-Oliveras, A, Munoz-Vega, M, Salinas, ML, Wang, X,Chapkin, RS, Dysregulation of cellular membrane homeostasis as a crucial modulator of cancer risk. FEBS J. 2024. 291(7): p. 1299-1352. [CrossRef]

- Mollinedo, F,Gajate, C, Lipid rafts as signaling hubs in cancer cell survival/death and invasion: implications in tumor progression and therapy: Thematic Review Series: Biology of Lipid Rafts. J Lipid Res. 2020. 61(5): p. 611-635.

- Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A, Augoff, K, Biernatowska, A, Podkalicka, J,Sikorski, AF, Membrane rafts as a novel target in cancer therapy. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014. 1845(2): p. 155-165. [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, I, Amyloid-beta Pathology Is the Common Nominator Proteinopathy of the Primate Brain Aging. J Alzheimers Dis. 2024. 100(s1): p. S153-S164.

- Kwiatkowska, K, Matveichuk, OV, Fronk, J,Ciesielska, A, Flotillins: At the Intersection of Protein S-Palmitoylation and Lipid-Mediated Signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. 21(7). [CrossRef]

- Trybus, M, Niemiec, L, Biernatowska, A, Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A,Sikorski, AF, MPP1-based mechanism of resting state raft organization in the plasma membrane. Is it a general or specialized mechanism in erythroid cells? Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2019. 57(2): p. 43-55.

- Chytla, A, Gajdzik-Nowak, W, Olszewska, P, Biernatowska, A, Sikorski, AF,Czogalla, A, Not Just Another Scaffolding Protein Family: The Multifaceted MPPs. Molecules. 2020. 25(21). [CrossRef]

- Biernatowska, A, Podkalicka, J, Majkowski, M, Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A, Augoff, K, Kozak, K, Korzeniewski, J,Sikorski, AF, The role of MPP1/p55 and its palmitoylation in resting state raft organization in HEL cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013. 1833(8): p. 1876-1884.

- Podkalicka, J, Biernatowska, A, Majkowski, M, Grzybek, M,Sikorski, AF, MPP1 as a Factor Regulating Phase Separation in Giant Plasma Membrane-Derived Vesicles. Biophys J. 2015. 108(9): p. 2201-2211. [CrossRef]

- Biernatowska, A, Wojtowicz, K, Trombik, T, Sikorski, AF,Czogalla, A, MPP1 Determines the Mobility of Flotillins and Controls the Confinement of Raft-Associated Molecules. Cells. 2022. 11(3). [CrossRef]

- Podkalicka, J, Biernatowska, A, Olszewska, P, Tabaczar, S,Sikorski, AF, The microdomain-organizing protein MPP1 is required for insulin-stimulated activation of H-Ras. Oncotarget. 2018. 9(26): p. 18410-18421. [CrossRef]

- Biernatowska, A, Augoff, K, Podkalicka, J, Tabaczar, S, Gajdzik-Nowak, W, Czogalla, A,Sikorski, AF, MPP1 directly interacts with flotillins in erythrocyte membrane - Possible mechanism of raft domain formation. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembr. 2017. 1859(11): p. 2203-2212. [CrossRef]

- Biernatowska, A, Olszewska, P, Grzymajlo, K, Drabik, D, Kraszewski, S, Sikorski, AF,Czogalla, A, Molecular characterization of direct interactions between MPP1 and flotillins. Sci Rep. 2021. 11(1): p. 14751. [CrossRef]

- Trybus, M, Hryniewicz-Jankowska, A, Wojtowicz, K, Trombik, T, Czogalla, A,Sikorski, AF, EFR3A: a new raft domain organizing protein? Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2023. 28(1): p. 86.

- Brown, DA, Analysis of raft affinity of membrane proteins by detergent-insolubility. Methods Mol Biol. 2007. 398: p. 9-20.

- Sezgin, E, Kaiser, HJ, Baumgart, T, Schwille, P, Simons, K,Levental, I, Elucidating membrane structure and protein behavior using giant plasma membrane vesicles. Nat Protoc. 2012. 7(6): p. 1042-1051. [CrossRef]

- Simons, K,Toomre, D, Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000. 1(1): p. 31-39. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z,MacKinnon, R, Structure of the flotillin complex in a native membrane environment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024. 121(29): p. e2409334121. [CrossRef]

- https://www.ebi.ac.uk/jdispatcher/msa/clustalo, The EMBL-EBI Job Dispatcher sequence analysis tools framework in 2024. accessed November 4th, 2024.

- https://www.rcsb.org/ank, RCSB Protein Data. accessed November 2024.

- Krieger, E,Vriend, G, YASARA View - molecular graphics for all devices - from smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics. 2014. 30(20): p. 2981-2982.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).