Submitted:

18 November 2024

Posted:

19 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Cancer is the second leading cause of death worldwide, with 27.5 million new cases projected by 2040. Disruptions in cell cycle control cause DNA errors to accumulate during cell growth, mak-ing proteins that regulate cell cycle progression crucial targets for cancer therapy. NIMA-related kinases (NEKs) are involved in regulating the cell cycle and checkpoints in humans. Among these, NEK10 is the most divergent member and has been associated with both cancer and ciliopathies. Despite its biological significance and distinctive domain architecture, structural details of NEK10 remain unknown. To address this gap, we modeled the complete structure of the NEK10 protein. Our analysis revealed a catalytic domain flanked by two coiled-coil domains, armadil-lo-type repeats, an ATP binding site, two putative UBA domains and a PEST sequence. Further-more, we mapped a comprehensive interactome of NEK10, uncovering previously unknown in-teractions with the cancer-related proteins MAP3K1 and HSPB1. MAP3K1, a serine/threonine kinase and E3 ubiquitin ligase frequently mutated in cancers, interacts with NEK10 via its scaf-fold regions. The interaction with HSPB1, a chaperone associated with poor cancer prognosis is mediated by NEK10’s armadillo repeats. Our findings underscore a connection of NEK10 with ciliogenesis and cancer, suggesting its important role in cancer development and progression.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Modeling and Characterization of NEK10

Domain Architecture

Secondary Structure Prediction (SSP), and Prediction of Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

Tertiary Structure Prediction of NEK10, Evaluation, Refining and Visualization

Protein-Protein Interaction Predictions for NEK10

Interactome for NEK10

Modeling and Characterization of Interaction Partners of NEK10

Prediction of NEK10–MAP3K1 Interaction and NEK10–HSPB1 Interactions

3. Results

Modeling and Characterization of NEK10

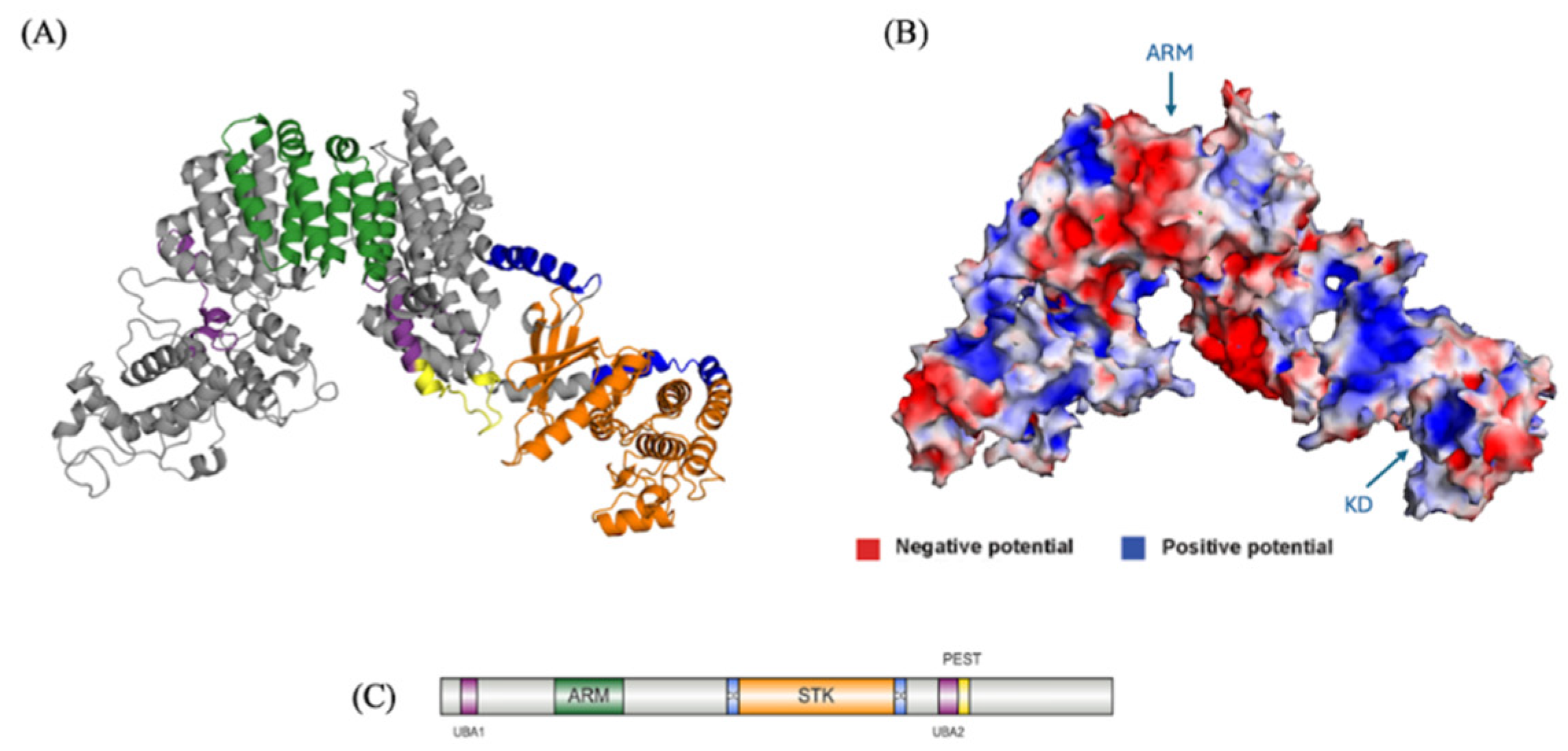

Tertiary Structure Prediction of NEK10

Comparison Between NEK10 Predicted Models: AlphaFold Versus Our Model

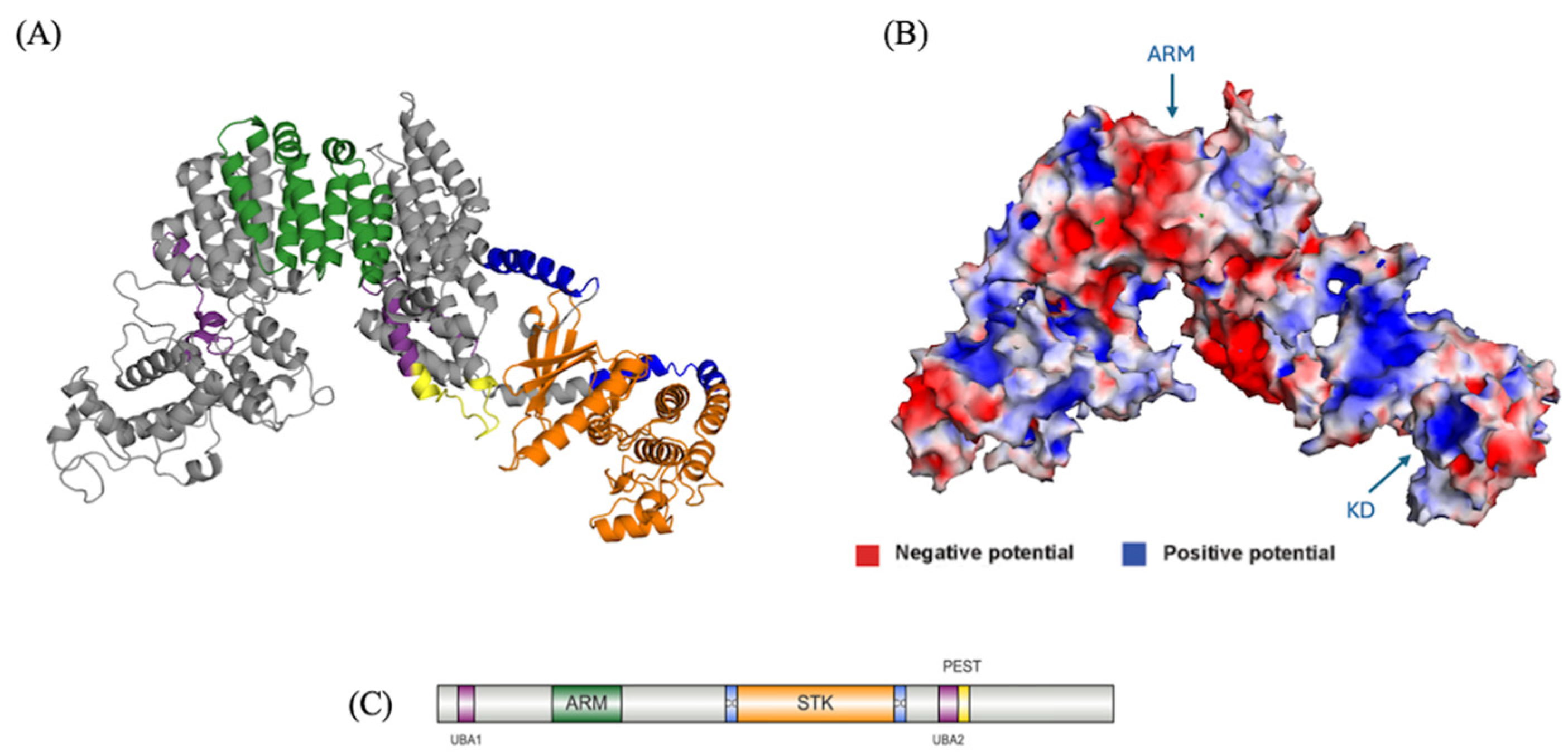

Protein-Protein Interaction Predictions for NEK10: Mapping a Comprehensive Interactome for NEK10

Investigation of NEK10’s Previously Uncharacterized Protein-Protein Interactions of NEK10

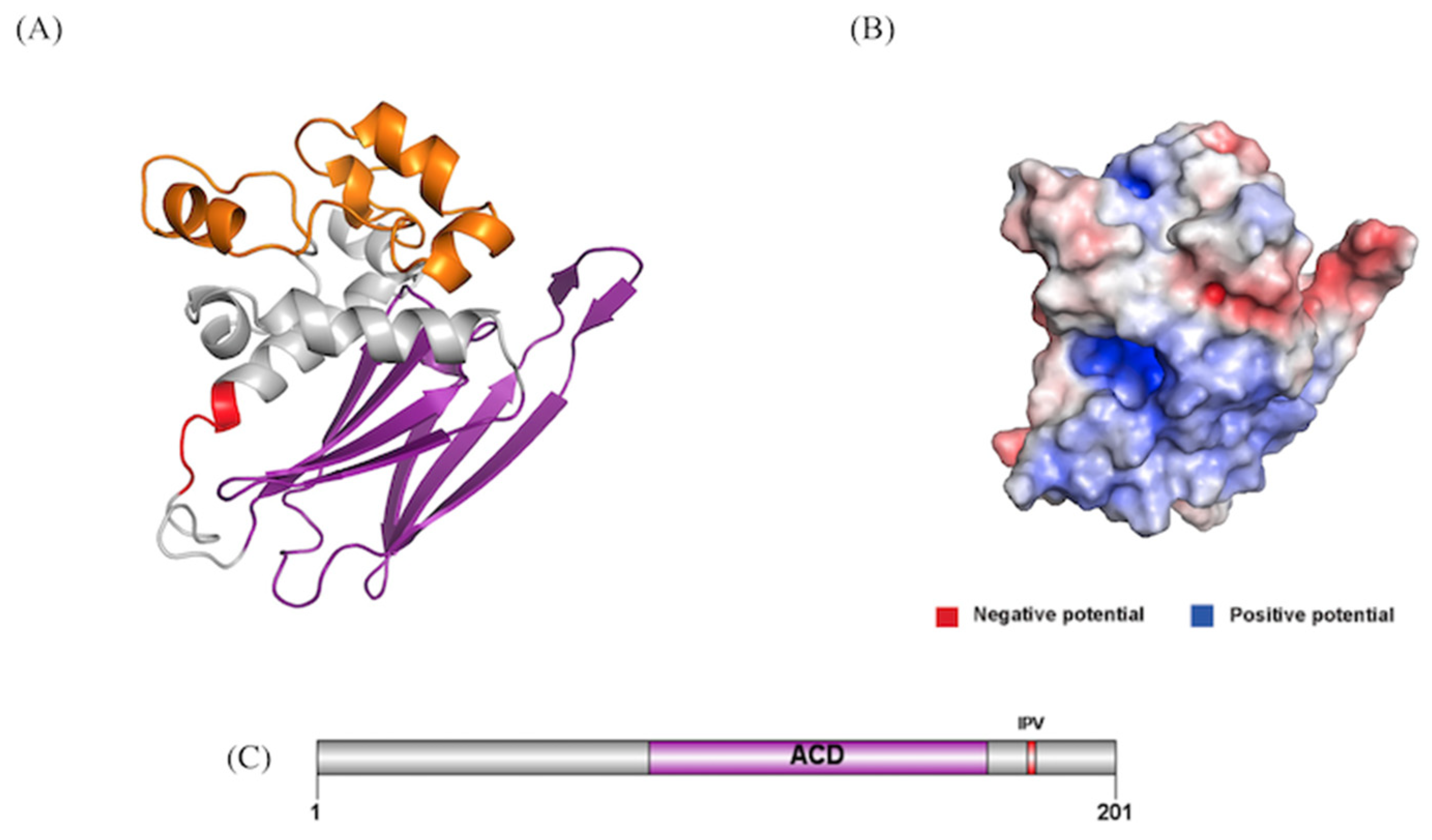

Prediction of NEK10–HSPB1 Interaction

Modeling and Characterization of HSPB1

Tertiary Structure Prediction of HSPB1

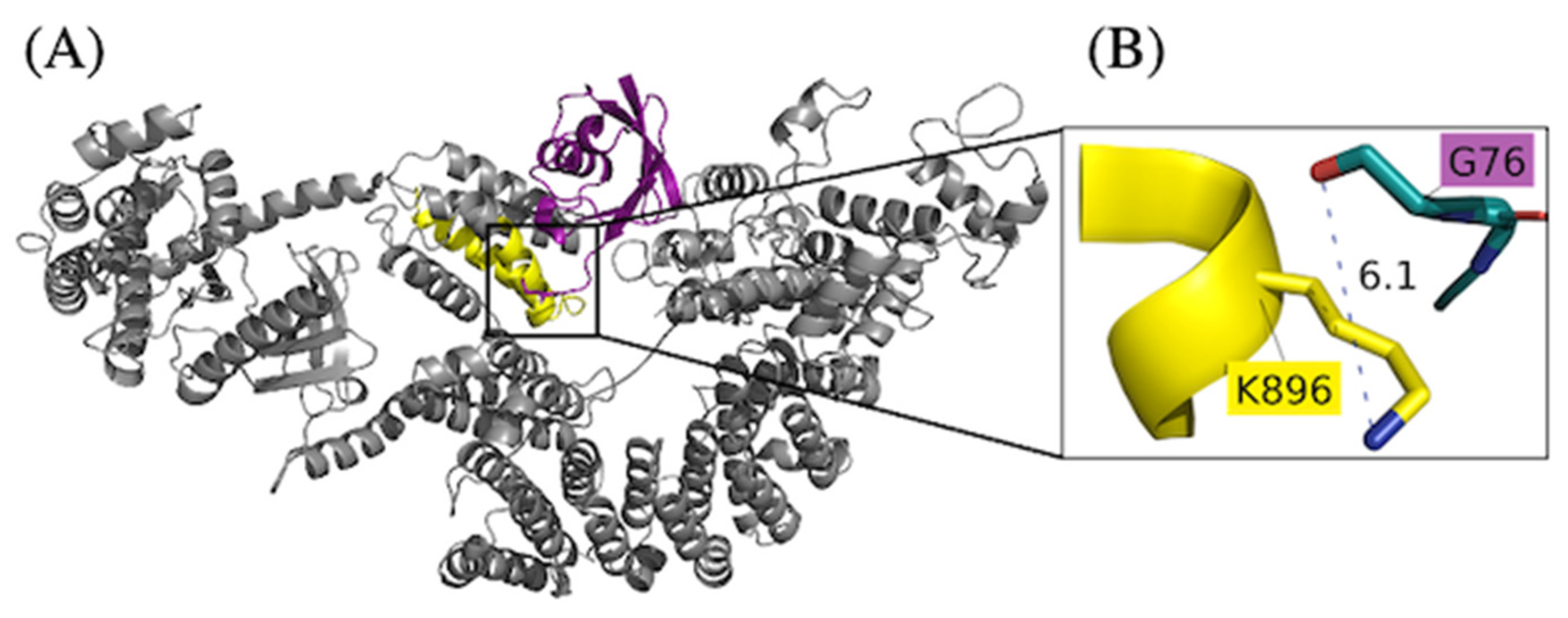

Prediction of NEK10 – HSPB1 Interaction

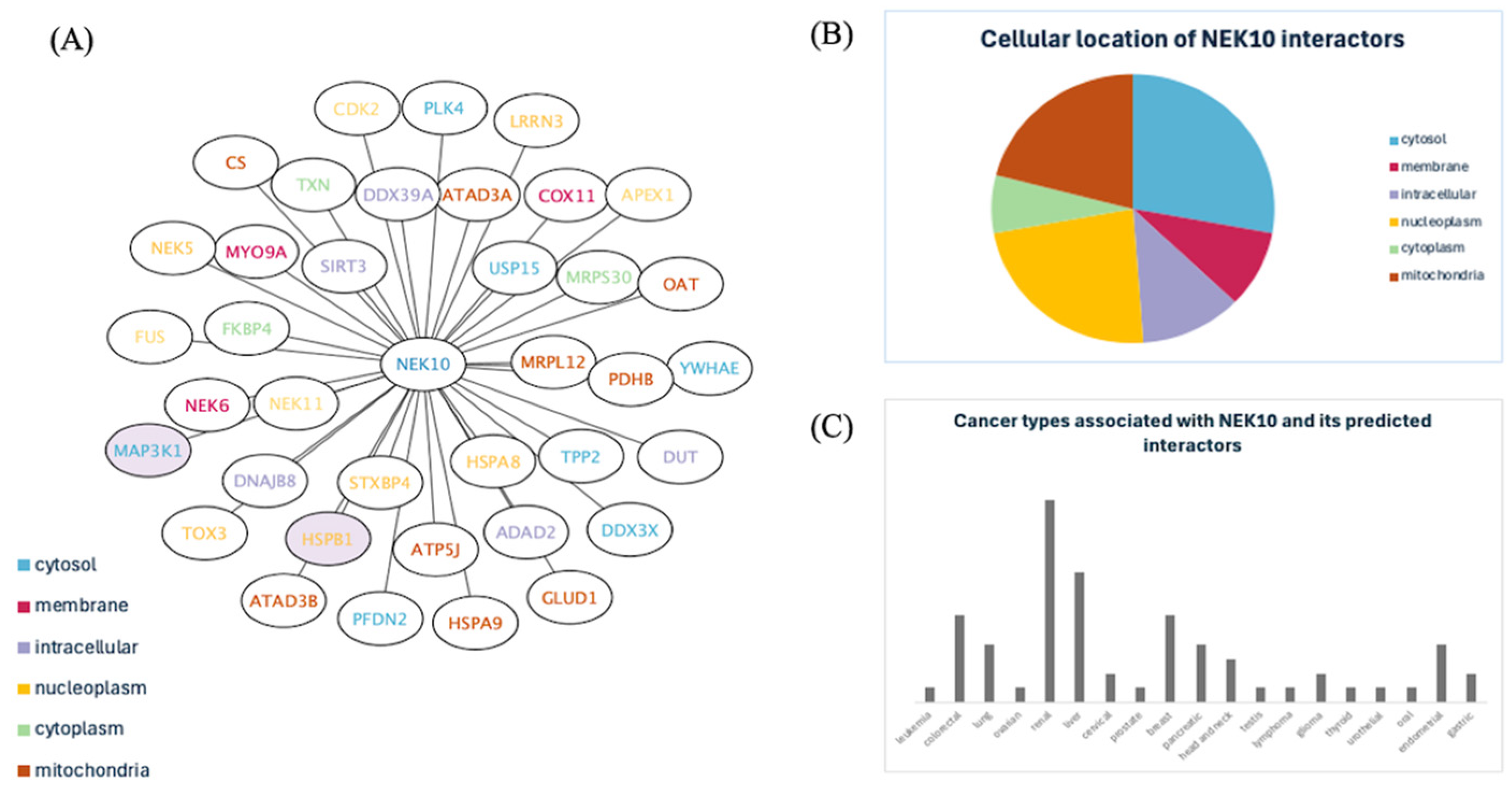

Modeling and Characterization of MAP3K1

Tertiary Structure Prediction of MAP3K1

Prediction of NEK10 – MAP3K1 Interaction

The Presence of a PEST Sequence and Putative UBA Domains Suggest it is Regulated via Ubiquitination

4. Discussion

Functional Insights of NEK10 Revealed from the NEK10 Full Length Model

The Comprehensive NEK10 Interactome Suggests Key Roles in Cellular Processes, Subcellular Localization, and Cancer Associations

NEK10’s Interaction with HSPB1 Is Mediated by Its Armadillo Repeats, with Key Residues Forming Crucial Protein-Protein Interaction Hotspots

NEK10-MAP3K1 Interaction Connects Kinase Activity and Microtubule Regulation, with Implications for Ciliogenesis and Cancer Progression

Regulation of NEK10 by Ubiquitination May Be Linked with a Cancer Phenotype

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nowell, P. C. (1976). The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science, 194(4260), 23–28. [CrossRef]

- Moniz, L. S., & Stambolic, V. (2011). Nek10 mediates G2/M cell cycle arrest and MEK autoactivation in response to UV irradiation. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 31(1), 30–42. [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, L., Blot, J., & Fry, A. M. (2007). Mitotic regulation by NIMA-related kinases. Cell Division, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Quarmby, L. M., & Mahjoub, M. R. (2005). Caught Nek-ing: cilia and centrioles. Journal of Cell Science, 118(22), 5161–5169. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A. M., Schultz, S. J., Bartek, J., & Nigg, E. A. (1995). Substrate specificity and cell cycle regulation of the Nek2 protein kinase, a potential human homolog of the mitotic regulator NIMA of Aspergillus nidulans. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 270(21), 12899–12905. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, S. J., Fry, A. M., Sütterlin, C., Ried, T., & Nigg, E. A. (1994). Cell cycle-dependent expression of Nek2, a novel human protein kinase related to the NIMA mitotic regulator of Aspergillus nidulans. PubMed, 5(6), 625–635. PMID: 7522034.

- Bahmanyar, S., Kaplan, D. D., DeLuca, J. G., Giddings, T. H., O’Toole, E. T., Winey, M., Salmon, E. D., Casey, P. J., Nelson, W. J., & Barth, A. I. M. (2008). β-Catenin is a Nek2 substrate involved in centrosome separation. Genes & Development, 22(1), 91. [CrossRef]

- Fry, A. M., Mayor, T., Meraldi, P., Stierhof, Y. D., Tanaka, K., & Nigg, E. A. (1998). C-Nap1, a novel centrosomal coiled-coil protein and candidate substrate of the cell cycle-regulated protein kinase Nek2. The Journal of Cell Biology, 141(7), 1563–1574. [CrossRef]

- Upadhya, P., Birkenmeier, E. H., Birkenmeier, C. S., & Barker, J. E. (2000). Mutations in a NIMA-related kinase gene, Nek1, cause pleiotropic effects including a progressive polycystic kidney disease in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97(1), 217–221. [CrossRef]

- Vogler, C., Homan, S., Pung, A., Thorpe, C., Barker, J., Birkenmeier, E. H., & Upadhya, P. (1999). Clinical and pathologic findings in two new allelic murine models of polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN, 10(12), 2534–2539. [CrossRef]

- Haider, N., Dutt, P., Van De Kooij, B., Ho, J., Palomero, L., Pujana, M. À., Yaffe, M. B., & Stambolic, V. (2020). NEK10 tyrosine phosphorylates p53 and controls its transcriptional activity. Oncogene, 39(30), 5252–5266. [CrossRef]

- Polci, R., Peng, A., Chen, P. L., Riley, D. J., & Chen, Y. (2004). NIMA-related protein kinase 1 is involved early in the ionizing radiation-induced DNA damage response. Cancer Research, 64(24), 8800–8803. [CrossRef]

- Basei, F. L., Meirelles, G. V., Righetto, G. L., Migueleti, D. L. dos S., Smetana, J. H. C., & Kobarg, J. (2015). New interaction partners for Nek4.1 and Nek4.2 isoforms: from the DNA damage response to RNA splicing. Proteome Science, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, K., & Sawasaki, T. (2013). Nek5, a novel substrate for caspase-3, promotes skeletal muscle differentiation by up-regulating caspase activity. FEBS Letters, 587(14), 2219–2225. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, E. E., Hehnly, H., Da Silva Perez, A. P., Meirelles, G. V., Smetana, J. H. C., Doxsey, S., & Kobarg, J. (2015). Human Nek7-interactor RGS2 is required for mitotic spindle organization. Cell Cycle, 14(4), 656–667. [CrossRef]

- De Oliveira, A. P., Basei, F. L., Slepicka, P. F., De Castro Ferezin, C., Melo-Hanchuk, T. D., De Souza, E. E., Lima, T. I., Santos, V. T. D., Mendes, D., Silveira, L. R., Menck, C. F. M., & Kobarg, J. (2020). NEK10 interactome and depletion reveal new roles in mitochondria. Proteome Science, 18(1). [CrossRef]

- De Souza, E. E., Meirelles, G. V., Godoy, B. B., Perez, A. M., Smetana, J. H. C., Doxsey, S. J., McComb, M. E., Costello, C. E., Whelan, S. A., & Kobarg, J. (2014). Characterization of the human NEK7 interactome suggests catalytic and regulatory properties distinct from those of NEK6. Journal of Proteome Research, 13(9), 4074–4090. [CrossRef]

- Kooij, B. van de, Creixell, P., Vlimmeren, A. van, Joughin, B. A., Miller, C. J., Haider, N., Simpson, C. D., Linding, R., Stambolic, V., Turk, B. E., & Yaffe, M. B. (2019). Comprehensive substrate specificity profiling of the human Nek kinome reveals unexpected signaling outputs. ELife, 8. [CrossRef]

- Porpora, M., Sauchella, S., Rinaldi, L., Delle Donne, R., Sepe, M., Torres-Quesada, O., Intartaglia, D., Garbi, C., Insabato, L., Santoriello, M., Bachmann, V. A., Synofzik, M., Lindner, H. H., Conte, I., Stefan, E., & Feliciello, A. (2018). Counterregulation of cAMP-directed kinase activities controls ciliogenesis. Nature Communications, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Chivukula, R. R., Montoro, D. T., Leung, H. M., Yang, J., Shamseldin, H. E., Taylor, M. S., Dougherty, G. W., Zariwala, M. A., Carson, J., Daniels, M. L. A., Sears, P. R., Black, K. E., Hariri, L. P., Almogarri, I., Frenkel, E. M., Vinarsky, V., Omran, H., Knowles, M. R., Tearney, G. J., … Sabatini, D. M. (2020). A human ciliopathy reveals essential functions for NEK10 in airway mucociliary clearance. Nature Medicine, 26(2), 244. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K., Julia, B., Tran, T., Rivera, A., Collins-Burow, B. M., … & Burow, M. E. (2023). Nek family review and correlations with patient survival outcomes in various cancer types. Cancers, 15(7), 2067. [CrossRef]

- Sigrist, C. J. (2002). PROSITE: A documented database using patterns and profiles as motif descriptors. Briefings in Bioinformatics, 3(3), 265–274. [CrossRef]

- Mistry, J., Chuguransky, S., Williams, L., Qureshi, M., Salazar, G. A., Sonnhammer, E. L. L., Tosatto, S. C. E., Paladin, L., Raj, S., Richardson, L. J., Finn, R. D., & Bateman, A. (2021). Pfam: The protein families database in 2021. Nucleic acids research, 49(D1), D412–D419. [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J., Milpetz, F., Bork, P., & Ponting, C. P. (1998). SMART, a simple modular architecture research tool: identification of signaling domains. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(11), 5857–5864. [CrossRef]

- Marchler-Bauer, A., Panchenko, A. R., Shoemaker, B. A., Thiessen, P. A., Geer, L. Y., & Bryant, S. H. (2002). CDD: a database of conserved domain alignments with links to domain three-dimensional structure. Nucleic acids research, 30(1), 281–283. [CrossRef]

- Rogers, S., Wells, R., & Rechsteiner, M. (1986). Amino acid sequences common to rapidly degraded proteins: the PEST hypothesis. Science, 234(4774), 364–368. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T. D., & Feigon, J. (2002). Solution structures of UBA domains reveal a conserved hydrophobic surface for protein-protein interactions. Journal of molecular biology, 319(5), 1243–1255. [CrossRef]

- Hagemans, D., van Belzen, I. A., Morán Luengo, T., & Rüdiger, S. G. (2015). A script to highlight hydrophobicity and charge on protein surfaces. Frontiers in molecular biosciences, 2, 56. [CrossRef]

- Holder, T. (2016, December 15). Anglebetweenhelices. PyMOLWiki. https://pymolwiki.org/index.php/AngleBetweenHelices.

- Jurrus, E., Engel, D., Star, K., Monson, K., Brandi, J., Felberg, L. E., Brookes, D. H., Wilson, L., Chen, J., Liles, K., Chun, M., Li, P., Gohara, D. W., Dolinsky, T., Konecny, R., Koes, D. R., Nielsen, J. E., Head-Gordon, T., Geng, W., Krasny, R., … Baker, N. A. (2018). Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society, 27(1), 112–128. [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., & Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of molecular biology, 215(3), 403–410. [CrossRef]

- Okonechnikov, K., Golosova, O., Fursov, M., & UGENE team (2012). Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 28(8), 1166–1167. [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Huang, Mumtaz, and S. Singh. Secondary structure visualization app.

- McGuffin, L. J., Bryson, K., & Jones, D. T. (2000). The PSIPRED protein structure prediction server. Bioinformatics, 16(4), 404–405. [CrossRef]

- Lin, K., Simossis, V. A., Taylor, W. R., & Heringa, J. (2005). A simple and fast secondary structure prediction method using hidden neural networks. Bioinformatics, 21(2), 152–159. [CrossRef]

- Yan, R., Xu, D., Yang, J., Walker, S. E., & Zhang, Y. (2013). A comparative assessment and analysis of 20 representative sequence alignment methods for protein structure prediction. Scientific Reports, 3(1), 2619. [CrossRef]

- Drozdetskiy, A., Cole, C., Procter, J., & Barton, G. J. (2015). JPred4: a protein secondary structure prediction server. Nucleic Acids Research, 43(W1), W389–W394. [CrossRef]

- Adamczak, R., Porollo, A., & Meller, J. (2004). Accurate prediction of solvent accessibility using neural networks-based regression. Proteins, 56(4), 753–767. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Li, W., Liu, S., & Xu, J. (2016). Raptorx-property: A web server for protein structure property prediction. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(W1). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J., Randall, A., Sweredoski, M. J., & Baldi, P. (2005). Scratch: a protein structure and structural feature prediction server. Nucleic Acids Research, 33(Web Server), W72-W76. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W., Xie, Y., Ma, J., Luo, X., Nie, P., Zuo, Z., Lahrmann, U., Zhao, Q., Zheng, Y., Zhao, Y., Xue, Y., & Ren, J. (2015). IBS: an illustrator for the presentation and visualization of biological sequences. Bioinformatics, 31(20), 3359–3361. [CrossRef]

- Ward, J. J., McGuffin, L. J., Bryson, K., Buxton, B. F., & Jones, D. T. (2004). The DISOPRED server for the prediction of protein disorder. Bioinformatics, 20(13), 2138–2139. [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, B., Erdős, G., & Dosztányi, Z. (2018). IUPRED2A: Context-dependent prediction of protein disorder as a function of redox state and protein binding. Nucleic Acids Research, 46(W1). [CrossRef]

- Mizianty, M. J., Stach, W., Chen, K., Kedarisetti, K. D., Disfani, F. M., & Kurgan, L. (2010). Improved sequence-based prediction of disordered regions with multilayer fusion of multiple information sources. Bioinformatics, 26(18), 489–496. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, I., Martin, A. J. M., Di Domenico, T., Vullo, A., Pollastri, G., & Tosatto, S. C. E. (2011). CSpritz: accurate prediction of protein disorder segments with annotation for homology, secondary structure and linear motifs. Nucleic Acids Research, 39(Web Server issue), W190. [CrossRef]

- Webb, B., & Sali, A. (2016). Comparative Protein Structure Modeling Using MODELLER. Current protocols in bioinformatics, 54, 5.6.1–5.6.37. [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D., Lüthy, R., & Bowie, J. U. (1997). VERIFY3D: Assessment of protein models with three-dimensional profiles. Methods in Enzymology, 396–404. [CrossRef]

- Wiederstein, M., & Sippl, M. J. (2007). ProSA-web: interactive web service for the recognition of errors in three-dimensional structures of proteins. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(Web Server), W407–W410. [CrossRef]

- Olechnovič, K., & Venclovas, Č. (2017). VoroMQA: Assessment of protein structure quality using interatomic contact areas. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics, 85(6), 1131–1145. [CrossRef]

- Uziela, K., Shu, N., Wallner, B., & Elofsson, A. (2016). ProQ3: Improved model quality assessments using Rosetta energy terms. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 33509. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D., & Zhang, Y. (2011). Improving the physical realism and structural accuracy of protein models by a two-step atomic-level energy minimization. Biophysical Journal, 101(10), 2525–2534. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, D., Nowotny, J., Cao, R., & Cheng, J. (2016). 3Drefine: An interactive web server for efficient protein structure refinement. Nucleic Acids Research, 44(W1). [CrossRef]

- Schrödinger, LLC. (2015). The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.8. Retrieved from https://pymol.org/.

- Pettersen, E. F., Goddard, T. D., Huang, C. C., Couch, G. S., Greenblatt, D. M., Meng, E. C., & Ferrin, T. E. (2004). UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. Journal of Computational Chemistry, 25(13), 1605–1612. [CrossRef]

- Oughtred, R., Rust, J., Chang, C. S., Breitkreutz, B., Stark, C., Willems, A., Boucher, L., Leung, G., Kolas, N. K., Zhang, F., Dolma, S., Coulombe-Huntington, J., Chatr-aryamontri, A., Dolinski, K., & Tyers, M. (2020). The BioGRID database: A comprehensive biomedical resource of curated protein, genetic, and chemical interactions. Protein Science, 30(1), 187–200. [CrossRef]

- Orchard, S., Ammari, M., Aranda, B., Breuza, L., Briganti, L., Broackes-Carter, F., Campbell, N., Chavali, G., Chen, C., Del-Toro, N., Duesbury, M., Dumousseau, M., Galeota, E., Hinz, U., Iannuccelli, M., Jagannathan, S., Jiménez, R. C., Khadake, J., Lagreid, A., . . . Hermjakob, H. (2013). The MIntAct project—IntAct as a common curation platform for 11 molecular interaction databases. Nucleic Acids Research, 42(D1). [CrossRef]

- Snel, B., Lehmann, G., Bork, P., & Huynen, M. A. (2000). STRING: a web-server to retrieve and display the repeatedly occurring neighbourhood of a gene. Nucleic acids research, 28(18), 3442–3444. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q. C., Petrey, D., Garzón, J. I., Deng, L., & Honig, B. (2012). PrePPI: a structure-informed database of protein–protein interactions. Nucleic Acids Research, 41(D1), D828–D833. [CrossRef]

- Calderone, A., Castagnoli, L., & Cesareni, G. (2013). mentha: a resource for browsing integrated protein-interaction networks. Nature Methods, 10(8), 690–691. [CrossRef]

- Breuer, K., Foroushani, A. K., Laird, M. R., Chen, C., Sribnaia, A., Lo, R., Winsor, G. L., Hancock, R. E., Brinkman, F. S., & Lynn, D. J. (2013). InnateDB: systems biology of innate immunity and beyond--recent updates and continuing curation. Nucleic acids research, 41(Database issue), D1228–D1233. [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, A., Gulfidan, G., Sinha, R., & Arga, K. Y. (2021). Differential Interactome Proposes Subtype-Specific Biomarkers and Potential Therapeutics in Renal Cell Carcinomas. Journal of personalized medicine, 11(2), 158. [CrossRef]

- Uhlén, M., Fagerberg, L., Hallström, B. M., Lindskog, C., Oksvold, P., Mardinoğlu, A., Sivertsson, Å., Kampf, C., Sjöstedt, E., Asplund, A., Olsson, I., Edlund, K., Lundberg, E., Navani, S., Szigyarto, C. A., Odeberg, J., Djureinovic, D., Takanen, J. O., Hober, S., . . . Pontén, F. (2015). Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science, 347(6220). [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P., Markiel, A., Ozier, O., Baliga, N. S., Wang, J. T., Ramage, D., Amin, N., Schwikowski, B., & Ideker, T. (2003). Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Research, 13(11), 2498–2504. [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. E., Chivian, D., & Baker, D. (2004). Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic acids research, 32(Web Server issue), W526–W531. [CrossRef]

- Kozakov, D., Hall, D. R., Xia, B., Porter, K. A., Padhorny, D., Yueh, C., Beglov, D., & Vajda, S. (2017). The ClusPro web server for protein–protein docking. Nature Protocols, 12(2), 255–278. [CrossRef]

- Yan Tao, H., He, J., & Huang, S. (2020). The HDOCK server for integrated protein–protein docking. Nature Protocols, 15(5), 1829–1852. [CrossRef]

- Laskowski, R. A. (2001). PDBsum: summaries and analyses of PDB structures. Nucleic Acids Research, 29(1), 221. [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J., Evans, R., Pritzel, A., Green, T., Figurnov, M., Ronneberger, O., Tunyasuvunakool, K., Bates, R., Žídek, A., Potapenko, A., Bridgland, A., Meyer, C., Kohl, S. a. A., Ballard, A. J., Cowie, A., Romera-Paredes, B., Nikolov, S., Jain, R., Adler, J., . . . Hassabis, D. (2021). Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature, 596(7873), 583–589. [CrossRef]

- Senior, A. W., Evans, R., Jumper, J., Kirkpatrick, J., Sifre, L., Green, T., Qin, C., Žídek, A., Nelson, A. W. R., Bridgland, A., Penedones, H., Petersen, S., Simonyan, K., Crossan, S., Kohli, P., Jones, D. T., Silver, D., Kavukcuoglu, K., & Hassabis, D. (2020). Improved protein structure prediction using potentials from deep learning. Nature, 577(7792), 706–710. [CrossRef]

- Park, H., Lee, G. R., Kim, D. E., Anishchenko, I., Cong, Q., & Baker, D. (2019). High-accuracy refinement using Rosetta in CASP13. Proteins, 87(12), 1276–1282. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Dong, X. S., Gao, H. Y., Jiang, Y. F., Jin, Y. L., Chang, Y. Y., Chen, L. Y., & Wang, J. H. (2016). Suppression of HSP27 increases the anti-tumor effects of quercetin in human leukemia U937 cells. Molecular Medicine Reports, 13(1), 689–696. [CrossRef]

- Cox, D., Selig, E., Griffin, M. D. W., Carver, J. A., & Ecroyd, H. (2016). Small Heat-shock Proteins Prevent α-Synuclein Aggregation via Transient Interactions and Their Efficacy Is Affected by the Rate of Aggregation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 291(43), 22618–22629. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. C., Sargsyan, K., Wright, J. D., Chen, Y. H., Huang, Y. S., & Lim, C. (2024). PPI-hotspotID for detecting protein-protein interaction hot spots from the free protein structure. eLife, 13, RP96643. [CrossRef]

- Mueller, T. D., & Feigon, J. (2002). Solution structures of UBA domains reveal a conserved hydrophobic surface for protein-protein interactions. Journal of molecular biology, 319(5), 1243–1255. [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, C. R., Seeger, M., Hartmann-Petersen, R., Stone, M., Wallace, M., Semple, C., & Gordon, C. (2001). Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nature cell biology, 3(10), 939–943. [CrossRef]

- Kim, W., Bennett, E. J., Huttlin, E. L., Guo, A., Li, J., Possemato, A., Sowa, M. E., Rad, R., Rush, J., Comb, M. J., Harper, J. W., & Gygi, S. P. (2011). Systematic and quantitative assessment of the ubiquitin-modified proteome. Molecular cell, 44(2), 325–340. [CrossRef]

- Peifer, M., Berg, S., & Reynolds, A. B. (1994). A repeating amino acid motif shared by proteins with diverse cellular roles. Cell, 76(5), 789–791. [CrossRef]

- Choi, H. J., & Weis, W. I. (2005). Structure of the Armadillo Repeat Domain of Plakophilin 1. Journal of Molecular Biology, 346(1), 367–376. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y., Jiang, Z., Gao, X., Luo, P., & Jiang, X. (2021). ARMC subfamily: Structures, functions, evolutions, interactions, and diseases. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 8. [CrossRef]

- Sahota, N., Sabir, S., O’Regan, L., Blot, J., Zalli, D., Baxter, J., Barone, G., & Fry, A. (2018). NEKs, NIMA-Related Kinases. Encyclopedia of Signaling Molecules, 3407–3419. [CrossRef]

- Sarfraz, M., Afzal, A., Khattak, S., Saddozai, U. A. K., Li, H. M., Zhang, Q. Q., Madni, A., Haleem, K. S., Duan, S. F., Wu, D. D., Ji, S. P., & Ji, X. Y. (2021). Multifaceted behavior of PEST sequence enriched nuclear proteins in cancer biology and role in gene therapy. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 236(3), 1658–1676. [CrossRef]

- Thrower, J. S., Hoffman, L., Rechsteiner, M., & Pickart, C. M. (2000). Recognition of the polyubiquitin proteolytic signal. The EMBO Journal, 19(1), 94–102. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W. L., Niu, L., Chen, W. L., Zhang, Y. Q., & Huang, W. H. (2022). Integrative Analysis of the Expression Levels and Prognostic Values for NEK Family Members in Breast Cancer. Frontiers in genetics, 13, 798170. [CrossRef]

- Rajagopal, P., Liu, Y., Shi, L., Clouser, A. F., & Klevit, R. E. (2015). Structure of the α-crystallin domain from the redox-sensitive chaperone, HSPB1. Journal of Biomolecular NMR, 63(2), 223–228. [CrossRef]

- Hochberg, G. K. A., Ecroyd, H., Liu, C., Cox, D., Cascio, D., Sawaya, M., Collier, M., Stroud, J. C., Carver, J. A., Baldwin, A. J., Robinson, C. V., Eisenberg, D., Benesch, J. L. P., & Laganowsky, A. (2014). The structured core domain of αB-crystallin can prevent amyloid fibrillation and associated toxicity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(16), 6726–6731. [CrossRef]

- Freilich, R., Betegon, M., Tse, E., Mok, S. A., Julien, O., Agard, D. A., Southworth, D. R., Takeuchi, K., & Gestwicki, J. E. (2018). Competing protein-protein interactions regulate binding of Hsp27 to its client protein tau. Nature Communications, 9(1). [CrossRef]

- Lang, B., Guerrero-Gimenez, M. E., Prince, T., Ackerman, A., Bonorino, C., & Calderwood, S. K. (2019). Heat shock proteins are essential components in transformation and tumor progression: cancer cell intrinsic pathways and beyond. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 20(18), 4507. [CrossRef]

- Davis, R. J. (1995). Transcriptional regulation by MAP kinases. Molecular Reproduction and Development, 42(4), 459–467. [CrossRef]

- Pham, T. T. T., Angus, S. P., & Johnson, G. L. (2013). MAP3K1: Genomic alterations in cancer and function in promoting cell survival or apoptosis. Genes & Cancer, 4(11–12), 419–426. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Wu, Z., Su, B., Murray, B., & Karin, M. (1998). JNKK1 organizes a MAP kinase module through specific and sequential interactions with upstream and downstream components mediated by its amino-terminal extension. Genes & Development, 12(21), 3369–3381. [CrossRef]

- Rieger, M. A., Duellman, T., Hooper, C., Ameka, M., Bakowska, J. C., & Cuevas, B. D. (2012). The MEKK1 SWIM domain is a novel substrate receptor for c-Jun ubiquitylation. Biochemical Journal, 445(3), 431–439. [CrossRef]

- Chamberlin, A., Huether, R., Machado, A. Z., Groden, M., Liu, H. M., Upadhyay, K., Vivian, O., Gomes, N. L., Lerario, A. M., Nishi, M. Y., Costa, E. M. F., Mendonca, B., Domenice, S., Velasco, J., Loke, J., & Ostrer, H. (2019). Mutations in MAP3K1 that cause 46,XY disorders of sex development disrupt distinct structural domains in the protein. Human Molecular Genetics, 28(10), 1620–1628. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., Geh, E., Meng, Q., Mongan, M. M., Wang, J., & Puga, A. (2011). MAP3K1 Integrates Developmental Signals for Eyelid Closure. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science, 52(14), 1186–1186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102297108.

- Filipčík, P., Latham, S. L., Cadell, A. L., Day, C. L., Croucher, D. R., & Mace, P. D. (2020). A cryptic tubulin-binding domain links MEKK1 to curved tubulin protomers. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 117(35), 21308–21318. [CrossRef]

- Wloga, D., Joachimiak, E., Louka, P., & Gaertig, J. (2017). Posttranslational Modifications of Tubulin and Cilia. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 9(6). [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, K., & Bucher, P. (1996). The UBA domain: a sequence motif present in multiple enzyme classes of the ubiquitination pathway. Trends in biochemical sciences, 21(5), 172–173.

- Yu, S., Yan, X., Tian, R., Xu, L., Zhao, Y., Sun, L., & Su, J. (2021). An Experimentally Induced Mutation in the UBA Domain of p62 Changes the Sensitivity of Cisplatin by Up-Regulating HK2 Localisation on the Mitochondria and Increasing Mitophagy in A2780 Ovarian Cancer Cells. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(8), 3983. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, K., & Mahajan, N. P. (2013). ACK1 tyrosine kinase: targeted inhibition to block cancer cell proliferation. Cancer letters, 338(2), 185–192. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H., Liu, P., Wang, Z. C., Zou, L., Santiago, S., Garbitt, V., Gjoerup, O. V., Iglehart, J. D., Miron, A., Richardson, A. L., Hahn, W. C., & Zhao, J. J. (2009). SIK1 couples LKB1 to p53-dependent anoikis and suppresses metastasis. Science signaling, 2(80), ra35. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. J., Kim, Y. M., Jeong, J., Bae, D. S., & Lee, K. J. (2012). Ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain in human Fas associated factor 1 inhibits tumor formation by promoting Hsp70 degradation. PloS one, 7(8), e40361. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).