1. Introduction

The complex interaction between telomeres and mitochondria is directly responsible for cellular homeostasis in the development of neoplasia and oncogenic transformation [

1]. The biological behavior of the cell is mediated by RNA-telomere interaction, particularly through telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA) which plays a crucial role in telomere maintenance and regulation [

2]. Long non-coding RNAs have emerged as key regulators in cancer pathways, influencing various aspects of tumor development and progression [

3]. In malignant cellular transformation, both microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs act as central players in cell fate differentiation, with microRNAs specifically regulating cancer stem cell characteristics and tumor development [

4]. Non-coding RNA (ncRNA) accounts for over 90% of human RNA; microRNA (miRNA) is a short ncRNA, typically 22-23 nucleotides long, its coding genes are transcribed by ARN polymerase II, they regulate mRNA expression by binding to the 3’untranslated region (3’UTR)of mRNA[

1]. The study of the molecular interaction networks between RNA, telomere and mitochondria is important for the development of diagnosis methods and therapeutic strategies in cancer.

2. Cellular Organization and Energy Metabolism

Cellular organelles in eukaryotes are highly complex that maintain intricate bidirectional signaling relationships. These signaling pathways result in cellular metabolism regulation and evolution towards a healthy state, cell death, or malignant transformation [

5]. Smaller molecules have the advantage of being able to diffuse more easily across the cell membrane compared to larger molecules. However, within the cell, specifically in the mitochondria, the membranes are highly complex, which is related to their energy production function [

6]. Mitochondrial membranes interact in a distinct manner with molecules and mediators, compared to the cytoplasmic membrane. Specifically, in mitochondria, the membrane folds or cristae facilitate a larger surface area for ATP production during the electron transport process in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, as well as other metabolic regulations and cell proliferation [

7].

Inside the mitochondria, within the mitochondrial matrix, lies the mitochondrial genome, which is structurally different from nuclear DNA. Mammalian mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is a compact circular genome of approximately 16.5 kb that encodes 13 subunits of the oxidative phosphorylation system, along with the tRNAs and rRNAs required for their expression. The mtDNA system, which resembles bacterial DNA in its organization, is capable of synthesizing proteins that operate in close coordination with nuclear-encoded proteins imported into the mitochondria [

8].

The electron transport complexes (I through V) in the inner mitochondrial membrane generate ATP mainly through oxidative phosphorylation. This process results in the formation of reactive oxygen species as a byproduct of biochemical reactions in ATP production [

9]. Additionally, mitochondria are associated with several pathways outside the tricarboxylic acid cycle, including fatty acid oxidation and amino acid metabolism. The varying energy requirements should in principle be met by the cell through plasticity in metabolic pathways to maintain homeostasis and survive in changing local microenvironment. The basic mechanisms are modified to produce metabolic shifts in the energy systems that are highly activated in cancer cells, supporting tumor progression and survival of neoplastic cells [

10].

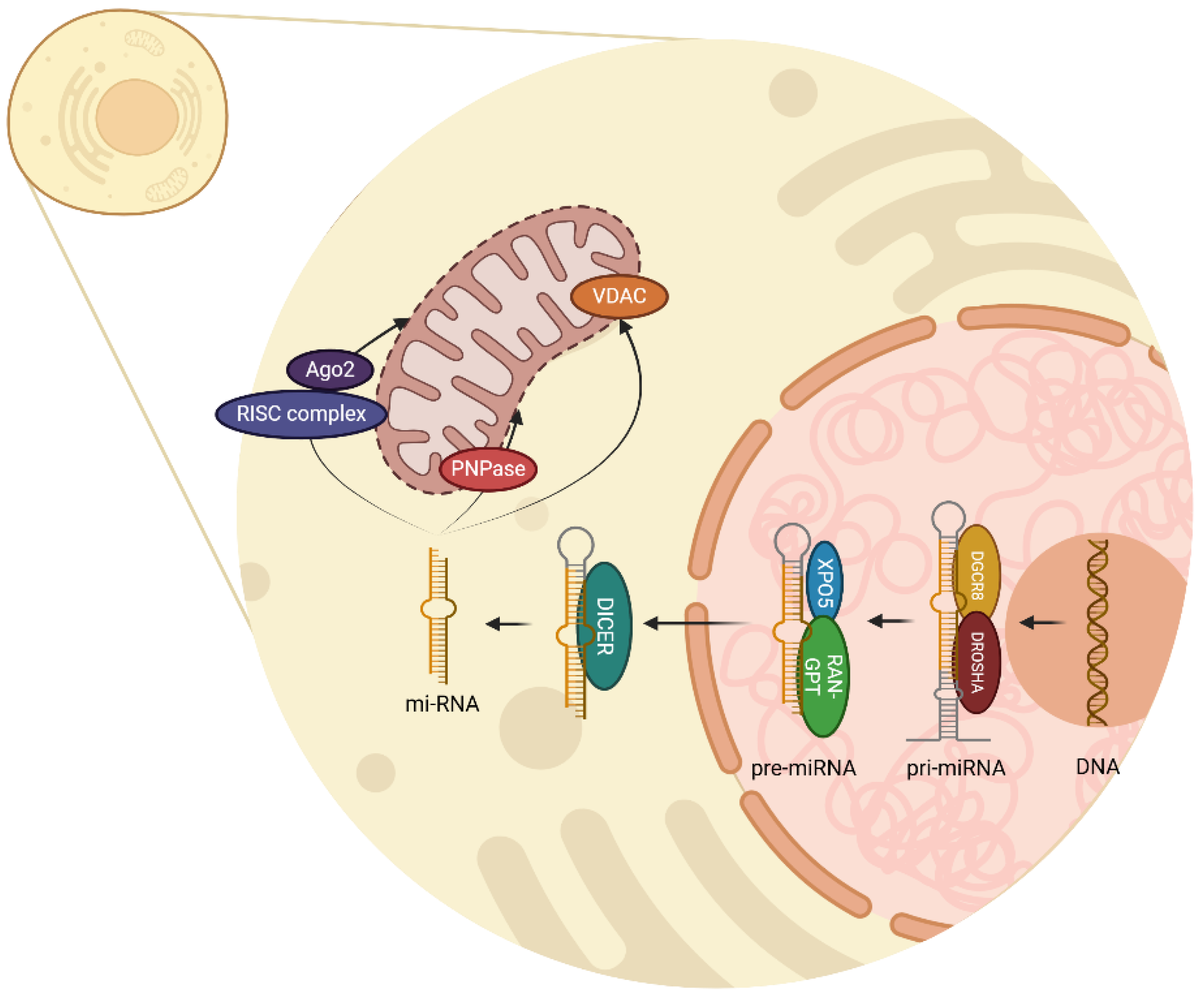

3. miRNA Biogenesis

miRNA biogenesis begins in the cell nucleus with the transcription of a DNA chain to create primary miRNA (pri-miRNA) by RNA polymerase II enzyme [

11]. This primary transcription is mediated by the complex DROSHA-DGCR8 which acts as an enzyme and removes the non-structured endings of the pri-miRNA, therefore creating pre-miRNA as a precursor [

11,

12]. DROSHA is a ribonuclease type II which cuts pri-miRNA, meanwhile DGCR8 acts as a cofactor to recognize and stabilize pri-miRNA structure [

13].

Once pre-miRNA is recognized by XPO5, and RAN-GTP provides the energy required, pre-miRNA is transported outside the nucleus within the cytoplasm. Then the enzyme DICER, a ribonuclease type III, recognizes and processes the chain by cutting the hairpin, thus a double-stranded miRNA of approximately 22 nucleotides is generated [

11,

12]. This miRNA duplex has two strands, the mature miRNA which will be the functional guide strand, and the passenger strand which will be degraded.

In the cytoplasm, miRNA can conjugate with various complexes and regulate important functions. When incorporated with the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and Argonaute 2 (Ago2) protein, this complex can identify complementary sequences in mRNA and regulate two mechanisms: mRNA degradation and translation inhibition [

14]. Additionally, it is known that several miRNAs can be found inside the mitochondria, accomplishing regulatory processes in mitochondrial genes. Polynucleotide phosphorylase (PNPase) facilitates the importation of miRNA into mitochondria, and voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) participates in RNA and proteins transportation through external mitochondria membrane [

15,

16]. All these processes are illustrated in

Figure 1.

4. Fusion and Fission Mitochondrial Processes and its Relationship with Telomeres

Mitochondria are a complex organelle that can fuse and divide to some degree, similar to bacterial cell division. Under certain conditions, mitochondria fuse specifically depending on the context, microenvironment, and cellular stress [

6,

17,

18]. Golgi apparatus-dependent mitochondrial fusion is achieved through GTPases such as Mitofusin 1 (MFN1) and Mitofusin 2 (MFN2), which coordinate the fusion of the outer mitochondrial membrane, while the fusion of the inner mitochondrial membrane is mediated by OPA1 [

6,

17,

19].

Dysregulation of fusion and fission promotes the survival of malignant cells; dysfunctional mitochondria lead to abnormalities in both mitochondrial morphology and function [

17,

18]. Fusion processes are particularly important when metabolic demand is high, and therefore mitochondria can fuse and share components to maintain their functionality and energy efficiency [

6,

18,

19].

The mitochondrial fission machinery depends on dynamin-related protein 1 (DRP1) and its receptors FIS1, MFF (mitochondrial gene-specific protein), and MiD49/51 to preserve mitochondrial morphology and their distribution in the cell matrix [

6,

17,

19]. In cancer cells, aberrant fission is observed that further promotes the proliferation and survival of malignant neoplastic cells, making it a stress response process [

17,

18,

19].

5. Mitochondrial-Telomere Communications in Cancer

4.1. Molecular Basis of Crosstalk Communication Between the Mitochondria and Telomeres

The bidirectional interrelation between mitochondria and telomeres at the molecular level plays a fundamental role in cellular homeostasis and adaptation. Recent research has revealed that this interaction is more complex than previously thought, particularly regarding oxidative stress and cellular signaling pathways [

20,

21].

A significant breakthrough in understanding this relationship comes from studies showing that mitochondrial H2O2 release and ROS production affect nuclear DNA and telomeres through sophisticated signaling mechanisms rather than direct oxidative damage, challenging previous assumptions about these interactions [

20,

22].

The telomere-mitochondria axis is particularly relevant in cellular senescence and aging processes. Research has demonstrated that telomere damage influences mitochondrial function through specific signaling pathways, notably the p53-PGC-1α pathway [

23]. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that interventions targeting this axis, such as metformin treatment, can influence both telomere stability and mitochondrial function, potentially mitigating cellular senescence [

24].

This complex interplay between telomeres and mitochondria represents a critical regulatory mechanism in cellular aging and disease progression, where dysfunction in either component can trigger a cascade of cellular responses affecting both structures [

20,

23]. Understanding these interactions has important implications for developing targeted therapeutic strategies for age-related diseases and cancer [

22,

24].

5.2. Mitochondrial-Telomere Communication via Non-Coding RNAs

Non-coding RNAs play a crucial role in mediating communication between mitochondria and telomeres. Recent research has revealed sophisticated mechanisms through which these RNA molecules coordinate various cellular processes, particularly in the context of senescence and cancer [

25].

A key discovery involves telomeric repeat-containing RNA (TERRA), which are long non-coding RNAs transcribed from dysfunctional telomeres. These TERRA transcripts have been shown to interact specifically with ZBP1 (Z-DNA binding protein 1) on the outer mitochondria membrane, where they form distinct oligomeric structures [

26,

27].

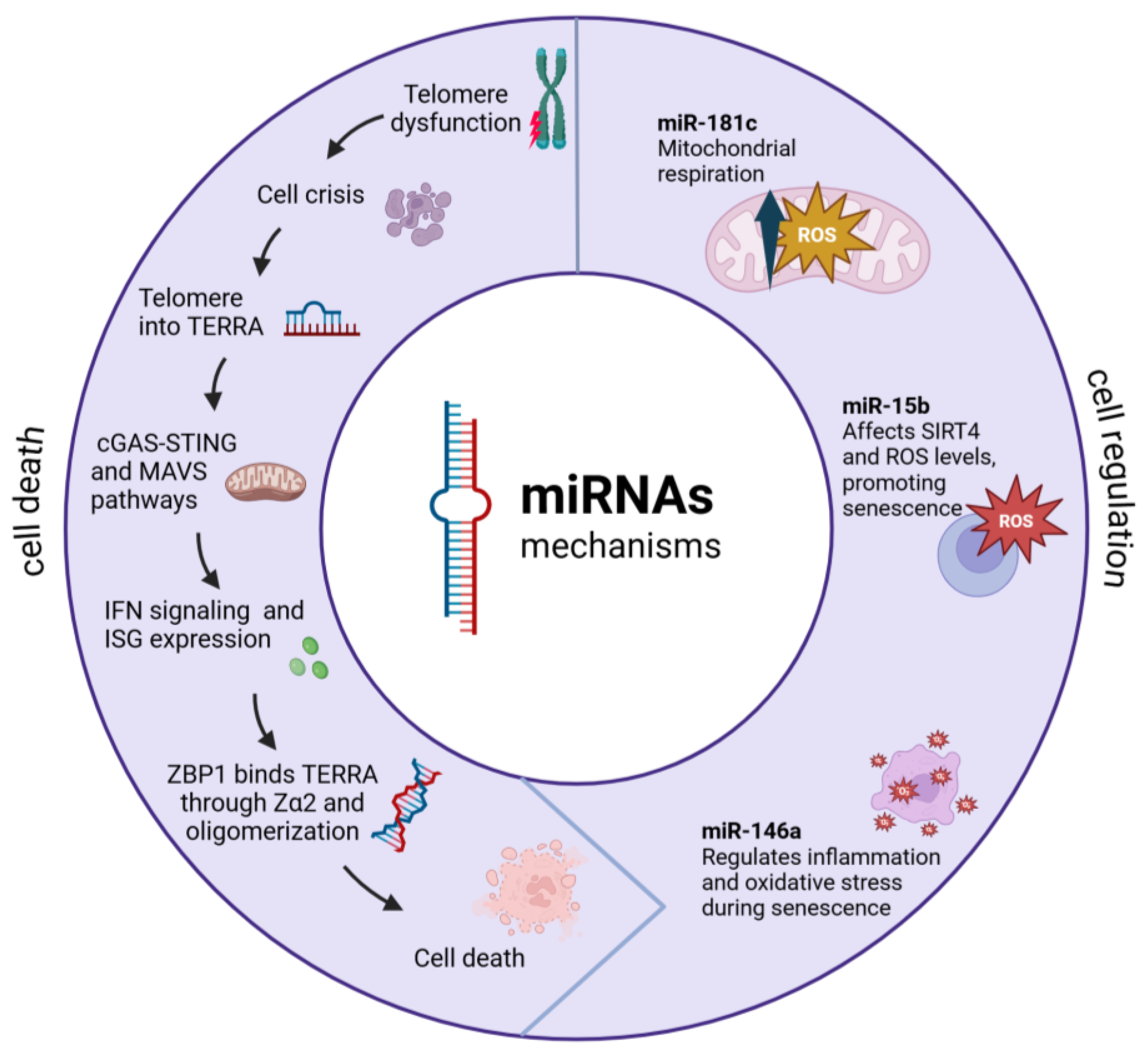

Dysfunctional telomeres trigger cellular senescence through the activation of DNA damage response pathways (

Figure 3). While senescence is mediated by p53 and RB pathways, cells with disrupted checkpoints bypass this protective mechanism [

28]. Therefore, these cells enter replicative crisis characterized by transcriptional changes due to an overlap of upregulated genes [

25,

29]. During crisis, telomeres undergo active transcription, producing TERRA, which consists of long non-coding RNA sequences containing UUAGGG repeats and subtelomeric-derived RNA [

29]. TERRA has been involved in the sensing innate immune system pathways, through the induction of interferon stimulated genes (ISGs) [

25]. Among ISG products, ZBP1 protein has emerged as a key mediator in the regulation of cell death and innate immunity, by the induction of type I IFNs. The production of ZBP1 appears to be related through to the cGAS-STING pathway in response to an accumulation of nucleic acids in the cytosol also DNA sensing by cGAS-STING upregulates the expression of ZBP1 [

25,

30].

The conformation of ZBP1-TERRA complex through the Za2 domain leads to activation of the MAVS pathway, resulting in ISG expression [

25]. Additionally, the complete activation of IFN-dependent ZBP1 requires the previous upregulation of ZBP1 by cGAS-STING and a signal from dysfunctional telomeres. When these conditions are fulfilled, an inflammatory loop is established, leading to an enhanced ISG expression and leads to cell death [

25]. This interaction triggers a cascade of events that can lead to programmed cell death in cancer cells, representing a novel tumor-suppressive mechanism [

14].

MicroRNAs, particularly those targeting mitochondrial functions (mitomiRs), have emerged as important regulators of cellular metabolism and cancer progression. These mitochondria-localized miRNAs can originate from both nuclear and mitochondrial genomes, impacting various aspects of energy metabolism and cellular defense mechanisms [

31]. Research has shown that specific mitomiRs are differentially expressed in various cancer types, affecting both mitochondrial function and metabolic reprogramming of cancer cells [

32].

Figure 2.

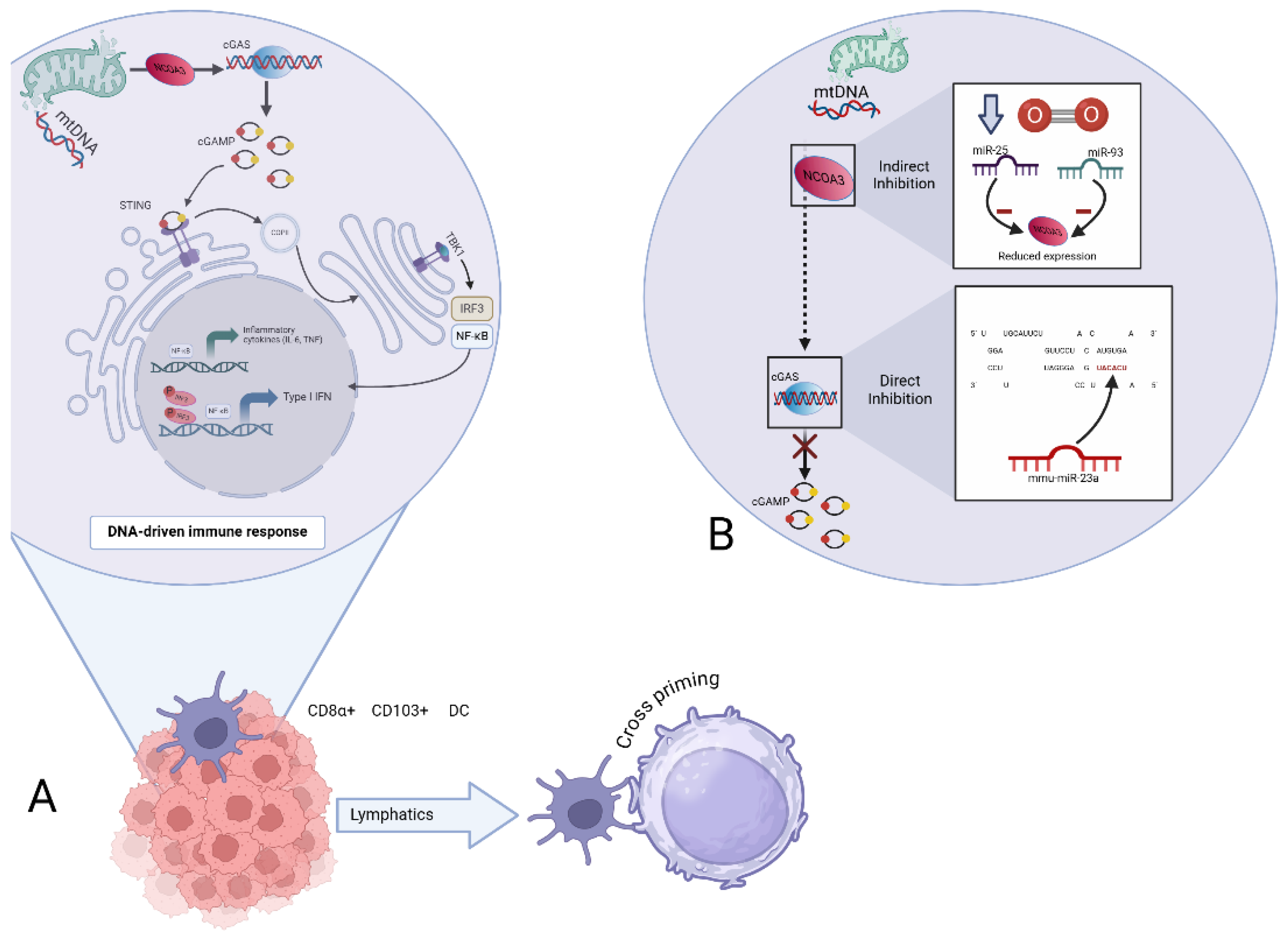

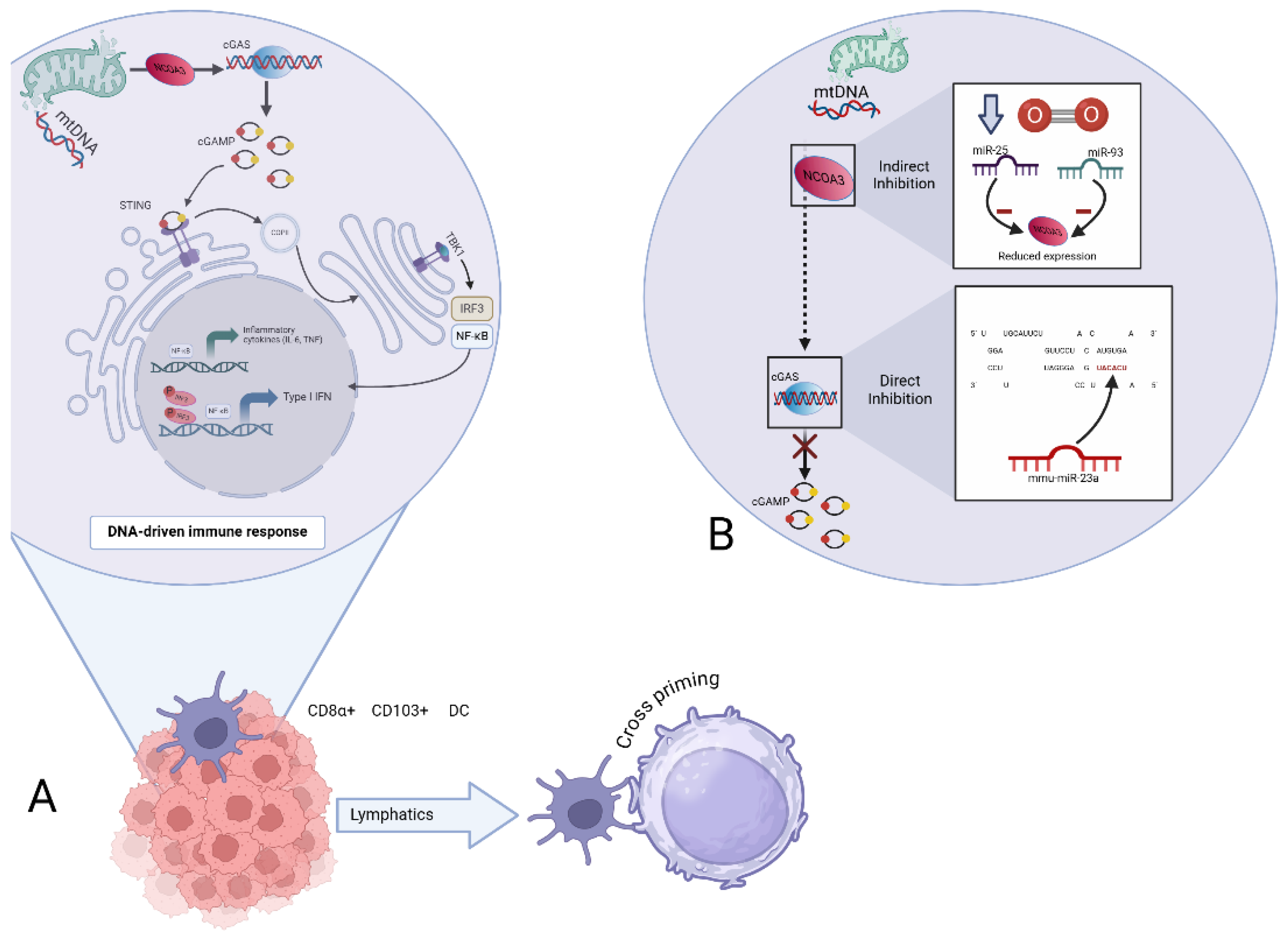

A. mtDNA dependent cGAS/STING signaling pathways and its suspected role in cancer approach. A schematic detailing double-stranded mtDNA is released into the cell due to minori-ty mitochondrial outer membrane permeability (miMOP). NCOA3 aids in maintaining cGAS expression. On binding mtDNA, cGAS dimers assemble on mtDNA resulting in enzymatic activa-tion of cGAS and synthesis of 2’3’cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP). cGAMP binds to stimulators of in-terferon genes (STING) dimers localized at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, leading to STING oligomerization and incorporation into coatomer protein complex II (COPII) vesicles. STING then recruits TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), promoting TBK1 autophosphorylation, STING phosphorylation at Ser366 and recruitment of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF 3). IRF3 phosphorylates, enabling its dimerization and translocation to the nucleus to induce gene expres-sion of type I interferons (IFN) and induction of genes encoding inflammatory cytokines (IL-6), finally enhancing DNA-driven immune response in dendritic cells (DC) leading to cross priming. B. Role of miRNAs in mtDNA-dependent cGAS/STING signaling. Under hypoxic conditions, miR-25 and miR-93 interact with the epigenetic factor NCOA3, indirectly affecting its ability to posi-tively regulate cGAS expression. On the other hand, miR-23a/b directly regulates the cGAS/STING pathway by binding to the 3’ region of cGAS. Either way resulting in restricting synthesis of cGAMP and therefore Type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines.

Figure 2.

A. mtDNA dependent cGAS/STING signaling pathways and its suspected role in cancer approach. A schematic detailing double-stranded mtDNA is released into the cell due to minori-ty mitochondrial outer membrane permeability (miMOP). NCOA3 aids in maintaining cGAS expression. On binding mtDNA, cGAS dimers assemble on mtDNA resulting in enzymatic activa-tion of cGAS and synthesis of 2’3’cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP). cGAMP binds to stimulators of in-terferon genes (STING) dimers localized at the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, leading to STING oligomerization and incorporation into coatomer protein complex II (COPII) vesicles. STING then recruits TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), promoting TBK1 autophosphorylation, STING phosphorylation at Ser366 and recruitment of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF 3). IRF3 phosphorylates, enabling its dimerization and translocation to the nucleus to induce gene expres-sion of type I interferons (IFN) and induction of genes encoding inflammatory cytokines (IL-6), finally enhancing DNA-driven immune response in dendritic cells (DC) leading to cross priming. B. Role of miRNAs in mtDNA-dependent cGAS/STING signaling. Under hypoxic conditions, miR-25 and miR-93 interact with the epigenetic factor NCOA3, indirectly affecting its ability to posi-tively regulate cGAS expression. On the other hand, miR-23a/b directly regulates the cGAS/STING pathway by binding to the 3’ region of cGAS. Either way resulting in restricting synthesis of cGAMP and therefore Type I IFN and proinflammatory cytokines.

Figure 3.

Telomere dysfunction triggers a complex molecular signaling cascade integrating innate immune responses. Telomere erosion and shelterin loss induce TERRA RNA transcription, which acts through two parallel pathways: forming complexes with ZBP1 (via Zα2 domain) that activate MAVS at the mitochondrial surface. These converging pathways lead to type I interferon signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. The response is amplified through feedback loops involving mitochondrial ROS production and sustained IRF3/7 and NF-κB activation. This mechanism serves as a tumor suppression pathway where telomere dysfunction couples to innate immunity through mitochondrial signaling, ultimately triggering cellular senescence or cell death programs based on telomeric damage severity.

Figure 3.

Telomere dysfunction triggers a complex molecular signaling cascade integrating innate immune responses. Telomere erosion and shelterin loss induce TERRA RNA transcription, which acts through two parallel pathways: forming complexes with ZBP1 (via Zα2 domain) that activate MAVS at the mitochondrial surface. These converging pathways lead to type I interferon signaling and pro-inflammatory cytokine production. The response is amplified through feedback loops involving mitochondrial ROS production and sustained IRF3/7 and NF-κB activation. This mechanism serves as a tumor suppression pathway where telomere dysfunction couples to innate immunity through mitochondrial signaling, ultimately triggering cellular senescence or cell death programs based on telomeric damage severity.

5.3. Mitochondrial Nuclear-Encoded MitomiRs

Nuclear-encoded miRNAs targeting mitochondria (mitomiRNAs) act as essential post-transcriptional regulators. Recent studies have shown that these miRNAs require specific targeting mechanisms and specialized transport systems for proper mitochondrial localization [

33]. Research has demonstrated that these regulatory molecules play crucial roles in maintaining mitochondrial function and cellular homeostasis [

34].

The regulation of mitochondrial function by nuclear mitomiRNAs occurs through multiple pathways. A well-documented example is miR-181c, which has been shown to significantly affect mitochondrial function by modulating ROS production and glucose oxidation patterns in cancer cells. Recent 2024 research has revealed its role as a tumor suppressor and its impact on drug response [

14].

Alterations in mitomiRNA expression are closely linked to cancer metabolism and mitochondrial stress signaling. The latest evidence from 2024 demonstrates that tumor cells process mitochondrial ROS regulation to interact with various components in the tumor microenvironment, thereby affecting cancer progression [

34]. Furthermore, these miRNAs can translocate into the mitochondria and regulate mitochondrial gene expression, which has important implications for cellular energy metabolism [

35].

5.4. Mitochondria-Encoded miRNAs

Mitochondrial-encoded miRNAs have recently begun to be studied, and while not much is known, it is understood that they are encoded in mitochondrial DNA and are processed by fine and specific machinery within the mitochondria [

19]. These unique miRNAs have been shown to have distinct processing mechanisms that differ from their nuclear counterparts, suggesting specialized regulatory functions [

14].

Initially, their existence was doubted; however, several studies have confirmed not only their existence but also their crucial participation in cellular metabolism and mitochondria-nucleus communication [

35]. Recent research has demonstrated their important role in the regulation of both nuclear and mitochondrial proteins, establishing a complex network of cellular regulation [

36].

Their processing is not traditional like nuclear miRNAs, suggesting a divergent evolution of these processing mechanisms. This evolutionary adaptation appears specifically aimed at regulating mitochondrial processes and facilitating communication with the nucleus [

19,

36]. Recent studies have shown that these mitochondrial-specific miRNAs play crucial roles in maintaining cellular homeostasis and energy metabolism [

14].

5.5. RNA-Dependent Modulation of the cGAS-STING Axis: Convergence of Mitochondrial Dynamics, Telomeric Integrity, and Programmed Cell Death Pathways

Non-coding RNA (ncRNA) accounts for over 90% of human RNA [

37]. MicroRNA (miRNA) is a short ncRNA, typically 22-23 nucleotides long, its coding genes are transcribed by ARN polymerase II, and very importantly they regulate mRNA expression by binding to the 3’untranslated region (3’UTR) of mRNA [

38].

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) are of great importance in the innate immune system,it is well known that PRRs recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and host damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) on the surface of innate immune cells [

39].

The PRRs that have been mainly related to the cGAS/STING pathways are melanoma deficiency factor 2 like receptors (ALRs) and 2’-5’oligoadenylate synthetase like receptors (OLRs). Once DNA is detected in the cell, ALR activates the STING-dependent interferon-stimulated gene (ISG) pathway through the endoplasmic reticulum-associated adapter stimulator of interferon genes (STING). This mechanism was originally studied in antiviral responses [

32]. OLR, on the other hand, refers to a group of cytoplasmic nucleic acid sensors, including cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS). When activated by double-stranded nucleic acids in cytoplasm, these sensors produce second messenger molecules like cGAMP. These molecules bind to and activate STING, triggering a downstream innate immune response [

38,

40].

cGAS activation leads to the synthesis of cGAMP from ATP and GTP, which then binds to STING dimers localized in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane, resulting in its incorporation into coatomer protein complex II (COPII) which then recruits and promotes autophosphorylation of TANK-binding kinase 1 (TBK1), STING phosphorylation at Ser366, recruitment and further phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), ultimately leading to the dimerization and translocation to the nucleus to induce gene expression of type I interferon, ISGs, along with other inflammatory mediators. Type I IFN-dependent STING-activating CD8α+/CD103+ cDC1 boosts cross-presentation of antigen to CD8+ T cells. IRF3 activity is also required for the induction of genes encoding inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-12) [

41,

42].

The causal link between sublethal stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, cytosolic mtDNA release, cGAS/STING pathway activation, senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) induction, chronic inflammation, senescence, and muscle and brain degeneration. Thus, it was demonstrated that mitochondria undergoing minority mitochondrial outer membrane permeability (miMOP) release mtDNA into the cytosol [

43].

The result of the release of mtDNA in the cell takes to induction of mtDNA-dependent cGAS-STING signaling, synthesis of type I interferon and inflammatory cytokines leading to SASP, senescence, and inflammation [

42,

43].

It can be inferred that mtDNA-dependent cGAS/STING signaling acquires great importance not only in senescence but also in certain illnesses such as cancer where it has been shown that the cGAS/STING axis signaling is crucial for antitumor immunity. STING activation is believed to promote tumor rejection by eliciting CD8+ T cell responses in various preclinical tumor models [

37]. It facilitates the recruitment of immune effector cells, such as T cells and NK cells, into the tumor microenvironment. Additionally, activation of the cGAS/STING pathway can suppress metastasis by enhancing the immune response against circulating cancer cells. As cancer cells attempt to spread to distant sites, an active STING pathway aids immune cells in recognizing and destroying these cells, thereby restricting the formation of new tumors [

44,

45,

46].

miRNAs have an essential role in the regulation of cGAS/STING signaling pathways. The 3’UTRs of cGAS and STING messenger RNA (mRNA) contain potential binding sites for some miRNAs. Various studies have demonstrated that miRNAs can suppress the immune response through different mechanisms. For instance, certain miRNAs, such as miR-23a/b, directly bind to the 3’ UTR of cGAS, inhibiting its expression and thereby suppressing the cGAS-mediated innate immune response [

47]. Indirectly, under hypoxic conditions, miR-25 and miR-93 regulate cGAS expression by targeting the epigenetic factor NCOA3, which is crucial for maintaining cGAS expression levels. This regulation results in the downregulation of cGAS mRNA levels, facilitating hypoxic tumor cells to evade immune detection by modulating the cGAS/STING pathway [

48].

Figure 1.

6. Metabolic Reprogramming in Cancer

Malignant cells are profoundly reprogrammed in terms of energy metabolism; these changes are linked to and affect telomere and mitochondrial function. Aerobic glycolysis is prominently used by tumor cells; this has been called the Warburg effect (Warburg, 1925). Cancer cells maintain a balance between aerobic glycolysis, which involves glucose fermentation even in the presence of oxygen, and oxidative phosphorylation that forms ATP through the oxidation of glucose carbon bridges [

49].

The balance in energy acquisition is directed towards the prolonged cellular survival characteristics of certain malignant tumor clones. This type of mixed metabolism favors the maintenance of telomere integrity, a characteristic of cancer cells [

50]. Thus, this type of cancer cell metabolism promotes proliferation and telomere length maintenance through modification of the tricarboxylic acid cycle, fatty acid oxidation, and amino acid metabolism [

51].

The AMPK-mTOR axis controls cellular energy metabolism and then mitochondrial function as well as a regulator for telomere maintenance. This pathway is tightly dysregulated in cancer cells; therefore, these changes support both metabolism and cell survival [

52]. Also, sirtuins, particularly SIRT1 and SIRT3, act as metabolism-associated sensors that regulate mitochondria and telomeres in cellular stress responses and cancer cell adaptation to specific context [

50].

Central in cellular metabolism regulation, the mTOR pathway, acting aberrantly in cancer cells, has multiple effects on cellular metabolism. Indeed, mTOR and AMPK are regarded as metabolic sensors that relay cell survival signals under stress, and such crosstalk with mitochondrial function and telomere maintenance is essential for promoting cancer [

49,

51]. This means that cancer cell metabolic plasticity, mitochondrial and telomere structure and function changes play an important role for the survival of neoplastic cell survival and proliferation [

52].

7. Clinical Implications and Therapeutic Applications

The relationship between mitochondria and telomeres and their connection to senescence and malignant transformation processes represents an opportunity for the diagnosis and monitoring of multiple diseases, especially oncological diseases. RNA species associated with oncological processes and cellular senescence can be useful as diagnostic markers and for monitoring disease progression, potentially adding greater specificity to traditional oncological markers [

53,

54].

In this sense, miRNAs are known to interact with several pathological conditions; high miR-181c expression was associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and differences in miR-138 levels with telomere abnormalities [

55]. The miRNAs as an entire family of transcriptional regulators and molecular receptors are likely to be useful in the clinical assessment for improved subtypes and prognostication of oncological diseases [

53,

54].

In this regard, these molecules can also be used as RNA-based therapy, which can be directed at specific therapeutic targets and especially as regulators of mitochondria and telomeres. This represents a new frontier in personalized medicine, as miRNAs can be used to regulate metabolic pathways that can be utilized according to the context of the tumor type and the pathways that are altered [

54,

56].

The goal is to restore cellular functions, specifically mitochondria and telomeres, through synthetic RNA or regulatory molecules of these RNAs. In the case of miR-34a, molecules that mimic it can be developed for the treatment of certain neoplasms to regulate mitochondrial functions and telomere maintenance and restore the homeostasis of both organelles [

57,

58].

8. Current Challenges and Future Directions

Developing these kinds of RNA-based therapeutics is challenging, including the intrinsic stability of RNA-based therapeutic agents and their delivery to the cellular compartments in which they are needed to modulate cellular functions. Nanoparticle delivery and other transport focused on the specific cells have been applied for reducing side effects as well as therapeutic efficacy [

59,

60].

Basic and clinical research is required to understand the complex network of molecular interactions of miRNAs and other RNA species. Bioinformatics and the development of highly complex and sophisticated computational models can shed light on the network of interactions between RNA, telomeres, and mitochondria, thereby enabling the development of appropriate and personalized therapies [

61,

62].

The integration of artificial intelligence methods and machine learning can lead to precise predictions and characterizations of different types of RNA and their relationship with mitochondrial and telomeric function and structure [

63,

64].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.A.C.R.; methodology, J.A.C.R.; software, B.A.L.C.; investigation, B.A.L.C. and A.L.F.R.; resources, E.M.J. and J.A.C.R.; data curation, B.A.L.C.; writing—original draft preparation, J.A.C.R.; writing—review and editing, E.M.J. and A.L.F.R.; supervision, E.M.J.; funding acquisition, E.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

Dulce Lizbeth Valdez Sánchez student of Universidad de Guadalajara for editing and figures.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Assalve, G.; Lunetti, P.; Rocca, M.S.; Cosci, I.; Di Nisio, A.; Ferlin, A.; Zara, V.; Ferramosca, A. Exploring the Link Between Telomeres and Mitochondria: Mechanisms and Implications in Different Cell Types. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 993. [CrossRef]

- Cusanelli, E.; Chartrand, P. Telomeric Repeat-Containing RNA TERRA: A Noncoding RNA Connecting Telomere Biology to Genome Integrity. Front. Genet. 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Statello, L.; Guo, C.-J.; Chen, L.-L.; Huarte, M. Gene Regulation by Long Non-Coding RNAs and Its Biological Functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 96–118. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.Q.; Ahmed, E.I.; Elareer, N.R.; Junejo, K.; Steinhoff, M.; Uddin, S. Role of miRNA-Regulated Cancer Stem Cells in the Pathogenesis of Human Malignancies. Cells 2019, 8, 840. [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, H.; Li, Y. Mitochondrial Dynamics in Health and Disease: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Ng, C.P.; Jones, O.; Fung, T.S.; Ryu, K.W.; Li, D.; Thompson, C.B. Lactate Activates the Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Independently of Its Metabolism. Molecular Cell 2023, 83, 3904-3920.e7. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson, C.M.; Falkenberg, M.; Larsson, N.-G. Maintenance and Expression of Mammalian Mitochondrial DNA. Annual Review of Biochemistry 2016, 85, 133–160. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; An, Y.; Ren, M.; Wang, H.; Bai, J.; Du, W.; Kong, D. The Mechanisms of Action of Mitochondrial Targeting Agents in Cancer: Inhibiting Oxidative Phosphorylation and Inducing Apoptosis. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14, 1243613. [CrossRef]

- Zou, W.; Rohatgi, N.; Brestoff, J.R.; Li, Y.; Barve, R.A.; Tycksen, E.; Kim, Y.; Silva, M.J.; Teitelbaum, S.L. Ablation of Fat Cells in Adult Mice Induces Massive Bone Gain. Cell Metabolism 2020, 32, 801-813.e6. [CrossRef]

- Ha, M.; Kim, V.N. Regulation of microRNA Biogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 509–524. [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.; Hayder, H.; Zayed, Y.; Peng, C. Overview of MicroRNA Biogenesis, Mechanisms of Actions, and Circulation. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2018, 9, 402. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Lee, Y.; Yeom, K.-H.; Kim, Y.-K.; Jin, H.; Kim, V.N. The Drosha-DGCR8 Complex in Primary microRNA Processing. Genes Dev 2004, 18, 3016–3027. [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; An, X.; Xiao, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, W.; Yu, D. Mitochondrial-Related microRNAs and Their Roles in Cellular Senescence. Front Physiol 2024, 14, 1279548. [CrossRef]

- Shoshan-Barmatz, V.; De Pinto, V.; Zweckstetter, M.; Raviv, Z.; Keinan, N.; Arbel, N. VDAC, a Multi-Functional Mitochondrial Protein Regulating Cell Life and Death. Mol Aspects Med 2010, 31, 227–285. [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Chen, H.-W.; Oktay, Y.; Zhang, J.; Allen, E.L.; Smith, G.M.; Fan, K.C.; Hong, J.S.; French, S.W.; McCaffery, J.M.; et al. PNPASE Regulates RNA Import into Mitochondria. Cell 2010, 142, 456–467. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Xiao, C.; Long, J.; Huang, W.; You, F.; Li, X. Mitochondrial Dynamics and Colorectal Cancer Biology: Mechanisms and Potential Targets. Cell Commun Signal 2024, 22, 91. [CrossRef]

- Darvin, P.; Sasidharan Nair, V. Editorial: Understanding Mitochondrial Dynamics and Metabolic Plasticity in Cancer Stem Cells: Recent Advances in Cancer Treatment and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1155774. [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y.; Li, H.; Liao, P.; Chen, L.; Pan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Zheng, M.; Gao, J. Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mechanisms and Advances in Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- van Soest, D.M.K.; Polderman, P.E.; den Toom, W.T.F.; Keijer, J.P.; van Roosmalen, M.J.; Leyten, T.M.F.; Lehmann, J.; Zwakenberg, S.; De Henau, S.; van Boxtel, R.; et al. Mitochondrial H2O2 Release Does Not Directly Cause Damage to Chromosomal DNA. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 2725. [CrossRef]

- Jagaraj, C.J.; Shadfar, S.; Kashani, S.A.; Saravanabavan, S.; Farzana, F.; Atkin, J.D. Molecular Hallmarks of Ageing in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2024, 81, 111. [CrossRef]

- Zeinoun, B.; Teixeira, M.T.; Barascu, A. Hog1 Acts in a Mec1-Independent Manner to Counteract Oxidative Stress Following Telomerase Inactivation in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhang, H.; Shi, Y.; He, X. Telomeres and Mitochondrial Metabolism: Implications for Cellular Senescence and Age-Related Diseases. Stem Cell Rev and Rep 2022, 18, 2315–2327. [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.Y.; Kim, S.G.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, J.-R.; Choi, H.C. Telomere Stabilization by Metformin Mitigates the Progression of Atherosclerosis via the AMPK-Dependent p-PGC-1α Pathway. Exp Mol Med 2024, 56, 1967–1979. [CrossRef]

- Nassour, J.; Aguiar, L.G.; Correia, A.; Schmidt, T.T.; Mainz, L.; Przetocka, S.; Haggblom, C.; Tadepalle, N.; Williams, A.; Shokhirev, M.N.; et al. Telomere-to-Mitochondria Signalling by ZBP1 Mediates Replicative Crisis. Nature 2023, 614, 767–773. [CrossRef]

- Strzyz, P. From Shortening Telomeres to Replicative Crisis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2023, 24, 239–239. [CrossRef]

- Gaela, V.M.; Chen, L.-Y. Ends End It via Mitochondria: A Telomere-Dependent Tumor Suppressive Mechanism Acts during Replicative Crisis. Molecular Cell 2023, 83, 1027–1029. [CrossRef]

- Nassour, J.; Radford, R.; Correia, A.; Fusté, J.M.; Schoell, B.; Jauch, A.; Shaw, R.J.; Karlseder, J. Autophagic Cell Death Restricts Chromosomal Instability during Replicative Crisis. Nature 2019, 565, 659–663. [CrossRef]

- Azzalin, C.M.; Reichenbach, P.; Khoriauli, L.; Giulotto, E.; Lingner, J. Telomeric Repeat–Containing RNA and RNA Surveillance Factors at Mammalian Chromosome Ends. Science 2007, 318, 798–801. [CrossRef]

- Zhan, J.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Wang, L.; Huang, L.; Liu, S.; Zeng, X.; Zeng, E.; Wang, H. Apoptosis Dysfunction: Unravelling the Interplay between ZBP1 Activation and Viral Invasion in Innate Immune Responses. Cell Communication and Signaling 2024, 22, 149. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, L.; Aikhionbare, K.; Banerjee, S.; Peagler, K.; Pitts, M.; Yao, X.; Aikhionbare, F. Differential Expression Profiles of Mitogenome Associated MicroRNAs Among Colorectal Adenomatous Polyps. Cancer Res J (N Y N Y) 2021, 9, 23–33.

- Feng, Y.; Huang, W.; Paul, C.; Liu, X.; Sadayappan, S.; Wang, Y.; Pauklin, S. Mitochondrial Nucleoid in Cardiac Homeostasis: Bidirectional Signaling of Mitochondria and Nucleus in Cardiac Diseases. Basic Res Cardiol 2021, 116, 49. [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C.-L.; Lin, Y.-C.; Lo, Y.K.; Lu, Y.-Z.; Babuharisankar, A.P.; Lien, H.-W.; Chou, H.-Y.; Lee, A.Y.-L. The Mitochondrial Stress Signaling Tunes Immunity from a View of Systemic Tumor Microenvironment and Ecosystem. iScience 2024, 27. [CrossRef]

- Maurya, A.K.; Rabina, P.; Kumar, V.B.S. In-Silico Analysis of Important Mitochondrial microRNAs and Their Differential Expression in Mitochondria 2024, 2024.04.25.591201.

- Dasgupta, N.; Peng, Y.; Tan, Z.; Ciraolo, G.; Wang, D.; Li, R. miRNAs in mtDNA-Less Cell Mitochondria. Cell Death Discovery 2015, 1, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yang, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Ma, L.; Shen, Y.-Q. Mitochondrial DNA-Targeted Therapy: A Novel Approach to Combat Cancer. Cell Insight 2023, 2, 100113. [CrossRef]

- Slack, F.J.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. The Role of Non-Coding RNAs in Oncology. Cell 2019, 179, 1033–1055. [CrossRef]

- Gareev, I.; de Jesus Encarnacion Ramirez, M.; Goncharov, E.; Ivliev, D.; Shumadalova, A.; Ilyasova, T.; Wang, C. MiRNAs and lncRNAs in the Regulation of Innate Immune Signaling. Non-coding RNA Research 2023, 8, 534–541. [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.-W.; He, J.; Yu, Y.; Liu, C.; Luo, Z.-Y.; Li, Z.-M.; Weng, S.-P.; Guo, C.-J.; He, J.-G. The Roles of Mandarin Fish STING in Innate Immune Defense against Infectious Spleen and Kidney Necrosis Virus Infections. Fish Shellfish Immunol 2020, 100, 80–89. [CrossRef]

- Hornung, V.; Hartmann, R.; Ablasser, A.; Hopfner, K.-P. OAS Proteins and cGAS: Unifying Concepts in Sensing and Responding to Cytosolic Nucleic Acids. Nat Rev Immunol 2014, 14, 521–528. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wu, J.; Du, F.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.J. Cyclic GMP-AMP Synthase Is a Cytosolic DNA Sensor That Activates the Type I Interferon Pathway. Science 2013, 339, 786–791. [CrossRef]

- Decout, A.; Katz, J.D.; Venkatraman, S.; Ablasser, A. The cGAS–STING Pathway as a Therapeutic Target in Inflammatory Diseases. Nat Rev Immunol 2021, 21, 548–569. [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, J.M. Mitochondria-cGAS-STING Axis Is a Potential Therapeutic Target for Senescence-Dependent Inflammaging-Associated Neurodegeneration. Neural Regen Res 2025, 20, 805–807. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Wedn, A.; Wang, J.; Gu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Z.; Zhou, R.; Pang, X.; Cui, Y. IUPHAR ECR Review: The cGAS-STING Pathway: Novel Functions beyond Innate Immune and Emerging Therapeutic Opportunities. Pharmacological Research 2024, 201, 107063. [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, C.J.; Wolf, N.; Chang, I.-C.; Kirn, G.; Marcus, A.; Ndubaku, C.O.; McWhirter, S.M.; Raulet, D.H. NK Cells Mediate Clearance of CD8+ T Cell-Resistant Tumors in Response to STING Agonists. Sci Immunol 2020, 5, eaaz2738. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, T.; Miyabe, H.; Hyodo, M.; Sato, Y.; Hayakawa, Y.; Harashima, H. Liposomes Loaded with a STING Pathway Ligand, Cyclic Di-GMP, Enhance Cancer Immunotherapy against Metastatic Melanoma. J Control Release 2015, 216, 149–157. [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Chu, L.; Li, Y.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, J.; Wang, C.; Cui, S. miR-23a/b Suppress cGAS-Mediated Innate and Autoimmunity. Cell Mol Immunol 2021, 18, 1235–1248. [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.-Z.; Cheng, W.-C.; Chen, S.-F.; Nieh, S.; O’Connor, C.; Liu, C.-L.; Tsai, W.-W.; Wu, C.-J.; Martin, L.; Lin, Y.-S.; et al. miR-25/93 Mediates Hypoxia-Induced Immunosuppression by Repressing cGAS. Nat Cell Biol 2017, 19, 1286–1296. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Guo, M.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y. Targeting P53 Pathways: Mechanisms, Structures and Advances in Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 1–35. [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, F.; Collavin, L.; Del Sal, G. Mutant P53 as a Guardian of the Cancer Cell. Cell Death Differ 2019, 26, 199–212. [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Liu, M.; Wang, R.; Man, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xu, Z.-X.; Wang, Y. The Crosstalk between Glucose Metabolism and Telomerase Regulation in Cancer. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 175, 116643. [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Dwivedi, Y. An Insight into the Sprawling Microverse of microRNAs in Depression Pathophysiology and Treatment Response. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2023, 146, 105040. [CrossRef]

- Pistritto, G.; Trisciuoglio, D.; Ceci, C.; Garufi, A.; D’Orazi, G. Apoptosis as Anticancer Mechanism: Function and Dysfunction of Its Modulators and Targeted Therapeutic Strategies. Aging 2016, 8, 603–619. [CrossRef]

- Ibragimova, M.; Kussainova, A.; Aripova, A.; Bersimbaev, R.; Bulgakova, O. The Molecular Mechanisms in Senescent Cells Induced by Natural Aging and Ionizing Radiation. Cells 2024, 13, 550. [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Qi, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Qin, Z. Targeting Sirtuins for Cancer Therapy: Epigenetics Modifications and Beyond. Theranostics 2024, 14, 6726–6767. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, L.; Qiu, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, X.; Guan, X.; Cen, X.; Zhao, Y. Tumor Biomarkers for Diagnosis, Prognosis and Targeted Therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 1–86. [CrossRef]

- Boccardi, V.; Marano, L. Aging, Cancer, and Inflammation: The Telomerase Connection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 8542. [CrossRef]

- Witten, J.; Hu, Y.; Langer, R.; Anderson, D.G. Recent Advances in Nanoparticulate RNA Delivery Systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2307798120. [CrossRef]

- Paunovska, K.; Loughrey, D.; Dahlman, J.E. Drug Delivery Systems for RNA Therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet 2022, 23, 265–280. [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, S.N.; Dahlman, J.E. RNA Delivery Systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2024, 121, e2315789121. [CrossRef]

- Winkle, M.; El-Daly, S.M.; Fabbri, M.; Calin, G.A. Noncoding RNA Therapeutics — Challenges and Potential Solutions. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2021, 20, 629–651. [CrossRef]

- Zarnack, K.; Eyras, E. ‘Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in RNA Biology.’ Briefings in Bioinformatics 2023, 24, bbad415. [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, D.D. From Sequences to Therapeutics: Using Machine Learning to Predict Chemically Modified siRNA Activity. Genomics 2024, 116, 110815. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).