1. Introduction

The EPR paradox notes the following property of quantum mechanics. Given a correlated pair of say two quantum subsystems, a measurement on one subsystem influences the other subsystem non-locally. This property has been confirmed by experiments and is equivalent to the confirmation that quantum systems violate Bell’s inequalities. Such a Bell-type measurement cannot be used to transmit information faster than light; therefore the laws of special relativity are not violated, in spite of there being a nonlocal influence. One could accept this peculiarity as an inevitable feature of quantum mechanics and assert that the collapse of the wavefunction is accompanied by a nonlocal effect, and there is nothing more to be explained. Alternatively, one could insist that the following needs to be explained: what is the physical mechanism whereby subsystems in a correlated quantum system impact each other outside the light cone [

1,

2]? Could it be that our understanding of spacetime structure in quantum theory is incomplete? It is this latter stance which is adopted in the present brief article, and a simple solution is proposed, which removes this tension between quantum mechanics and special relativity, without altering the laws of either theory.

Our proposal is that the spacetime of our universe is not four-dimensional, but six-dimensional. And that the two extra dimensions are timelike. Laws of special relativity hold also in this bigger spacetime with signature and influence of wave function collapse takes place locally in 6D spacetime. Correlated events that are time-like separated in 6D can appear to be spacelike separated in 4D, giving rise to the EPR paradox. Bell’s inequalities continue to be violated, in 6D as well as in 4D. This is so because the violation is equivalent to ruling out a deterministic locality. Indeterministic locality is permitted (which is what gives rise to higher-than-classical quantum correlations). In 4D, this translates into an apparent indeterministic nonlocality, giving rise to the illusion of a conflict between quantum mechanics and relativity.

In the next section, we briefly introduce the Dirac equation in 6D spacetime. Also, one can embed two 4D spacetime manifolds in 6D, having relatively flipped signatures. Classical systems, including detectors, live in only one of the two 4D submanifolds. In

Section 3 we use the Dirac equation to derive spin matrices in 6D and then in 4D. In

Section 4, we explain the resolution of the EPR paradox in some detail and comment on the hypothetical possibility of its experimental validation. In

Section 5 we describe the motivation for extra time-like dimensions coming from our ongoing research program of gravi-weak unification. In

Section 6 we note that the Tsirelson bound in the CHSH inequality can sometimes be violated.

4. Proposed Resolution of the EPR Paradox

4.1. Proposal

Suppose Alice and Bob are spacelike separated inertial observers in our 4D spacetime who are stationary with respect to each other. Both of them have one electron/positron each from a pair in an entangled state. When Alice makes an observation on her electron, the wave function of Bob’s positron seems to collapse as if it violates locality. Local hidden variable theories were introduced to understand this but Bell inequalities show that such theories have an upper bound, and quantum theories violate that bound showing that local hidden variable theories cannot explain experiments. Quantum theory goes against local realism, and any hidden variable theory must be non-local.

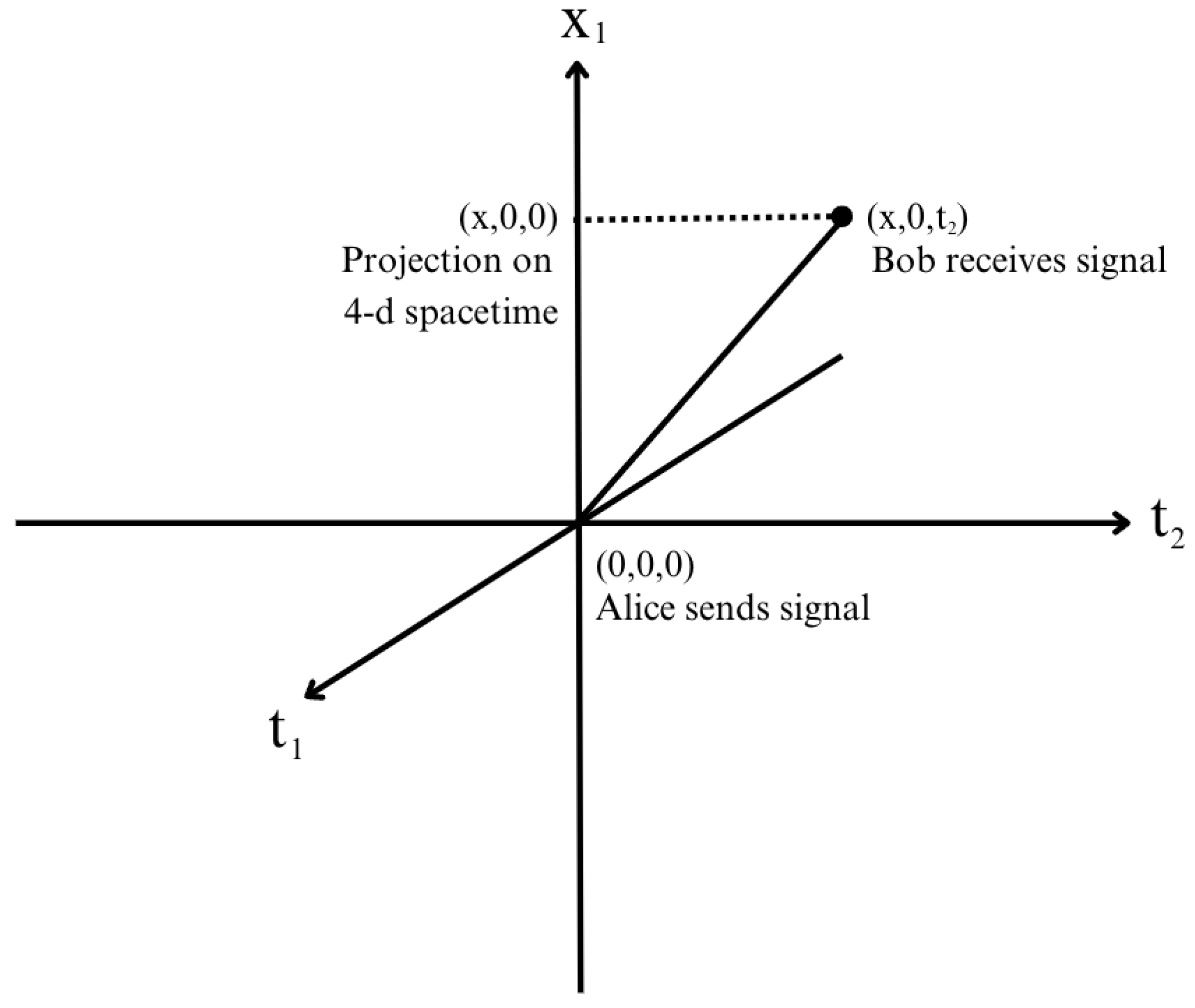

We propose that the non-locality puzzle can be resolved in the presence of a 6D spacetime of signature

, and by assuming that the electron-positron pair traverse the 6D spacetime, not 4D spacetime. Consider the 3D illustration of

Figure 1 where

are dimensions in our 4D spacetime and

is a timelike dimension in 6D.

From

Figure 1, the Minkowski space-time interval can be mathematically expressed as the following line element:

Choose

,

, and

such that the path defined by this line element is inside the light cone of this 3D spacetime

which has signature

, namely two time-like and one space-like directions. In other words,

. Now consider the case that even when

, the line element is time-like. That is,

is positive.

Consider the 2D spacetime [which represents our spacetime in which Alice and Bob make measurements]. In such a case, while observing the event, we will naturally assume and conclude that and that the separation between the sending of a signal and the receiving of the signal is spacelike and hence nonlocal. This is as though faster-than-light influence has taken place. However, in the 3D universe, the event is local and obeys special relativity.

Thus, the EPR paradox can be resolved if there is an additional time-like direction in the universe. Classical systems do not probe the direction. Only quantum systems, which obey quantum linear superposition, probe . A photon travelling from Alice to Bob travels along a path which is a quantum superposition of a path in and a path in . If we do not know of the photon path in the other submanifold, that lack of knowledge gives rise to the EPR paradox.

In essence, we are saying that the path through the other sub-manifold is shorter than the path in ours and takes less time to traverse. The spatial coordinate separation is just , which is the same in both submanifolds. But the proper physical spatial distance depends on the spacetime metric, and this metric can be different in the two sub-manifolds, making the path in the other sub-manifold shorter in spatial distance, and hence it is covered in less time. If is the proper spatial distance in the other submanifold and is the proper spatial distance in the usual 4D spacetime, then . Light takes time to travel from Alice to Bob in the other submanifold. In our 4D spacetime, the amount of time elapsed while a distance is covered in the other universe is , which is far less than the actual travel time in our 4D spacetime. The arrival at Bob appears instantaneous to us; which is why we set .

4.2. Experimental Validation

Consider that Alice makes a measurement that causes the electron state to collapse. The signal carrying information about the collapse travels from Alice to Bob (through ) at the speed of light, arriving at the correlated positron after a time . Clearly, the influence on the positron is not instantaneous but takes a finite time (howsoever small). If Bob makes his measurement on the positron prior to time , i.e., prior to the arrival of information of collapse from Alice, evidently the correlation will not have been established. The results of Bob’s measurements in this case will not show a violation of Bell’s inequalities. The inequalities will only be violated if Bob’s measurements are made later than time . In principle, this feature can be tested experimentally.

In practice, however, the experiment is extremely challenging, and essentially impossible, with current technology. This is because, in our research program of gravi-weak unification, the pseudo-Riemannian geometry of the manifold

is determined by the weak force. Whereas in our spacetime

, the cosmic horizon is at about

cm, in

this same horizon is at the range of the weak force, namely about

cm. In other words, lengths are scaled down by an enormous factor

, and through

light will travel from our location to the cosmic horizon in merely

s, which of course for all practical purposes is instantaneous. Therefore, in reality,

s and a Bell test of the 6D spacetime idea is simply impossible. An observer unaware of the 6D spacetime will infer that the signal travelled through our 4D spacetime at a staggering speed of

c. This is far, far greater than the lower experimental bound of about

c on the speed of such a correlation signal (assuming that collapse information travels through our 4D spacetime at the speed of light) [

5]. This experimental bound also tells us that the shrinking of lengths in

, relative to

, is at least by a factor of

.

An important caveat in the above reasoning was brought to our attention by Gisin [

6]. When the measurements by Alice and Bob are spacelike separated, there is no definite causal order (past to future) between Alice’s measurement and Bob’s measurement - the ordering is frame-dependent. Therefore, such an experiment as the one proposed above, if at all it could be done, will have to be in a universal absolute time, say in the rest frame of the cosmic microwave background.

The second path through

could be suggestively called a `quantum wormhole’. Our proposal can also be viewed as a rigorous realisation of the ER=EPR idea [

7]. Instead of the Einstein-Rosen bridge, we have an extremely short space-time path connecting Alice and Bob through the second spacetime. It will be interesting to study black-hole solutions in 6D spacetime, and enquire how such black holes relate to black hole solutions in

and in

.

5. Physical Motivation for Two Timelike Extra Dimensions

There is considerable literature on physics in six-dimensional spacetimes with signature

. The motivations for such considerations are varied, starting with desiring as many time dimensions as spatial ones. Quaternions also point to a 6D spacetime, as Lambek explains in his paper titled `Quaternions and three temporal dimensions’ [

8]. He writes in the abstract of his paper: “The application of quaternions to special relativity predicts a six-dimensional universe, which uncannily resembles ours, except that it admits three dimensions of time. Yet its mathematical description with the help of quaternions gains in transparency, due to the crucial observation that every skew-symmetric four-by-four real matrix is the sum of two matrices representing multiplication by vector quaternions on the left and the right respectively.”

In an insightful paper titled `Germ of a synthesis: space-time is spinorial, extra dimensions are time-like’ Sparling [

9] observes the relation of null twistor spaces with 6D spacetime. It is worthwhile to quote from his abstract:

First, an integral transform is introduced into Einstein’s general relativity that is non-local and spinorial. For Minkowskian space-time, the transform intertwines three spaces of six dimensions, which a priori are on an equal footing, linked by the octavic triality of Cartan. Two of these spaces are interpreted as null twistor spaces; the third may be regarded as giving space-time two extra time-like dimensions, for which the ordinary space-time is an axis of symmetry.

Second, it is suggested that the extra dimensions perdure for a general space–time: the overall structure is controlled by a generalized Fefferman tensor. Accordingly, it is posited that the additional time-like dimensions arise naturally and constitute an aspect of space-time reality that ultimately will be amenable to experimental investigation.

Highly relevant for us is also the (1985) paper of Patty and Smalley [

10] titled `Dirac equation in a six-dimensional spacetime’. The authors show that a (3+3) spacetime can be divided into six copies of (3+1) subspaces. 6D spaces are also of interest from the viewpoint of a superluminal extension of (3+1) special relativity, and it has been shown that a 6D spacetime is the smallest one which can accommodate a superluminal as well as a subliminal branch of (3+1) spacetime [

11]. Six dimensional = (3+3) spacetimes were studied extensively in a series of papers by Cole [

12] and also by Teli [

13]. An early work on `quaternions and quantum mechanics’ is Conway (1948) [

14]. Very relevant for us is also Kritov (2021) [

15] who shows that the Clifford algebra

can be used to make two copies of 4D spacetime with relatively flipped signatures. Dartora and Cabrera (2009) [

16] have studied `The Dirac equation in six-dimensional SO(3,3) symmetry group and a non-chiral `electroweak theory’. An old (1950) paper by Podolanski [

17] studies unified field theory in six dimensions, and in fact the abstract starts by saying `The geometry of the Dirac equation is actually six-dimensional’. An elegant (2020) paper by Venancio and Batista [

18] analyses `Two-Component spinorial formalism using quaternions for six-dimensional spacetimes’. An insightful (1993) work by Boyling and Cole [

19] studies the six-dimensional (3+3) Dirac equation and shows that particles have spatial spin-1/2 and temporal spin-1/2. See also Brody and Graefe (2011) [

20]. Shtanov and Sahni studied a five-dimensional cosmological model with two time-like dimensions [

21]. Interestingly, such a universe bounces at high densities and the nature of the bounce is similar to that in loop quantum cosmology.

Our interest in 6D spacetime stems from the ongoing research program on unification, known as the

octonionic theory of unification, and recently reviewed in Singh (2024) [

3]. This pre-spacetime, pre-quantum theory is a matrix-valued Lagrangian dynamics on a split bi-octonionic space, which obeys the

unified symmetry prior to the electroweak symmetry breaking. This is also the gravi-weak symmetry breaking, wherein each of the two

-s branch into four

s. The net result is a 6D spacetime of signature

broken into two overlapping 4D spacetimes

and

and six emergent forces. Four of these are currently known to us, and two new forces are predicted, these being

and

. On

, the breaking

gives rise to the weak force as pseudo-Riemannian geometry of

, with the unbroken sector

providing the geometry of the vector bundle. The quantum number associated with

is the electric charge

e. Correspondingly, on

, the breaking of another

gives rise to general relativity as the pseudo-Riemannian geometry of

, with the unbroken sector

providing the geometry of the vector bundle. DEM stands for dark electromagnetism and the quantum number associated with

is the square root of mass

(this is the reason for the interchange

in

Section 3 when going from

to

).

Thus, the weak force is the space-time geometry of

and general relativity is the space-time geometry of

. Both interactions are chiral, the former being left-handed, and the latter right-handed. Together, they are unified into a (non-chiral) gravi-weak symmetry on 6D spacetime, prior to the electroweak symmetry breaking. A detailed analysis leading to these results will be presented in a forthcoming paper [

22]. Thus, in our unification program, it is natural to consider a 6D spacetime with signature (3,3) as physical reality.

6. Tsirelson Bound

Bell’s theorems are a set of closely related results which imply that quantum mechanics is incompatible with local hidden variable theories. Bell’s inequality is the statement that when measurements are performed independently on two space-like separated particles in an entangled pair, the assumption that outcomes depend on local hidden variables implies an upper bound on the correlations between the outcomes. As we know, quantum mechanics predicts correlations which violate this upper bound. The CHSH inequality is a particular Bell inequality in which classical correlation (i.e., if local hidden variables exist) can take the maximum value of 2. Quantum mechanics violates this bound, allowing for a higher bound on the correlation, which can take the maximum value

, known as the Tsirelson bound [

23]. Popescu and Rohrlich [

24] showed that the assumption of relativistic causality allows for an even higher bound on the CHSH correlation, this value being 4. It is important to ask why the bound coming from causality is higher than the Tsirelson bound. Are there relativistic causal dynamical theories which violate the Tsirelson bound? In a recent paper [

25], we found this to indeed be the case. We showed that the pre-quantum theory of trace dynamics, from which quantum theory is emergent as a thermodynamic approximation, permits the CHSH correlation to take values higher than

. We interpreted our findings to suggest that quantum theory is approximate and emergent from the more general theory of trace dynamics.

What impact does the extension of spacetime to 6D have on the Tsirelson bound on quantum correlations? Our analysis below suggests that in this scenario as well, the Tsirelson bound could be beaten.

Suppose the system under analysis is entangled, described by

, the state prepared by us. The situation is the same as what is discussed in the EPR paradox. Consider the superposition state

(over the two spacetimes

and

) and let us find out what happens to the correlations

. The expectation value of the correlation

is given by:

Substituting

, we get

Using the linearity of the inner product and factoring out constants:

There is an important contribution from cross-terms that may not be zero even if the states are orthogonal. This occurs because the operator AB defined on the complete Hilbert space can rotate

in such a way that it positions it at an angle other than

relative to

. This happens because of the off-block-diagonal terms in (

5). Note that the states are normalised, that is,

. What we can now do is identify the real number coming from the cross-terms as

The CHSH correlation function

F is given by:

This can be expressed as:

where

and

are defined as :

We compute the squares of

and

The square of

F, i.e.,

, in terms of

,

and

r is given by:

Now for the case of the normalized state

, where

and

. Using the upper bounds

and

and the AM-GM (arithmetic mean - geometric mean) inequality, the expression simplifies to:

which then gives us

This shows the possibility that the Tsirelson bound can be violated in some cases, provided

, or

. If

the CHSH inequality is obeyed. For

, the Popescu-Rohrlich bound of 4 on the CHSH correlation

F is reached. Curiously, this numerical value

is precisely the gap between the PR value 4 and the Tsirelson bound of

. By defining the variable

the contribution of the cross-terms can be suggestively written as

, showing

z to be the measure of violation of the Tsirelson bound. The bound is obeyed when

and violated if

. The PR bound is equivalent to

. Considering how

r was defined in Eqn. (

79) above, it seems to be the case that these cross-terms are precisely the missing link between the Tsirelson bound and the Popescu-Rohrlich bound.

It could be that current experiments are unable to detect supra-quantum nonlocal correlations precisely because the consequences of the cross-terms (which make

r non-zero) are very hard to detect. This is for the same reasons as mentioned in

Section 5; i.e., the transmission through the path in

is enormously quick.

Also, the challenge for appropriate experiments is that whichever observables we currently measure act only on

, they never rotate

outside of

; at least, we cannot claim this theoretically. For the observables that do such rotations, one might wonder if they correspond to any physical quantity. Our assessment is that such observables will be physical; they likely relate to the weak interaction, since the weak interaction determines the spacetime geometry of

. Therefore, it could be that high energy experiments proposed to test Bell’s inequalities at colliders [

26] might be the ideal place to look for violation of the Tsirelson bound. Because such experiments are likely to be sensitive to the weak scale.

Considering that the weak force is the spacetime geometry of , there ought to exist weak waves, analogous to gravitational waves and electromagnetic waves, but having wavelengths smaller than cm. If ever such waves are detected in experiments, they could be a possible indicator of 6D spacetime.

The presence of three times sometimes raises enquiry as to their physical implications. For instance, which of these is the time that flows, and hence defines an arrow of time? Our stance is that these three times are time

coordinates, on the same footing as the three spatial coordinates. They are mechanistic and reversible, and cannot by themselves provide a time arrow. The role of fundamental time is played by a parameter which by itself is not part of the space-time manifold. In our research program, such a parameter is the so-called Connes time in non-commutative geometry, whose origin lies in the Tomita-Takesaki theorem for von Neumann algebras [

27].