Submitted:

29 January 2025

Posted:

30 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

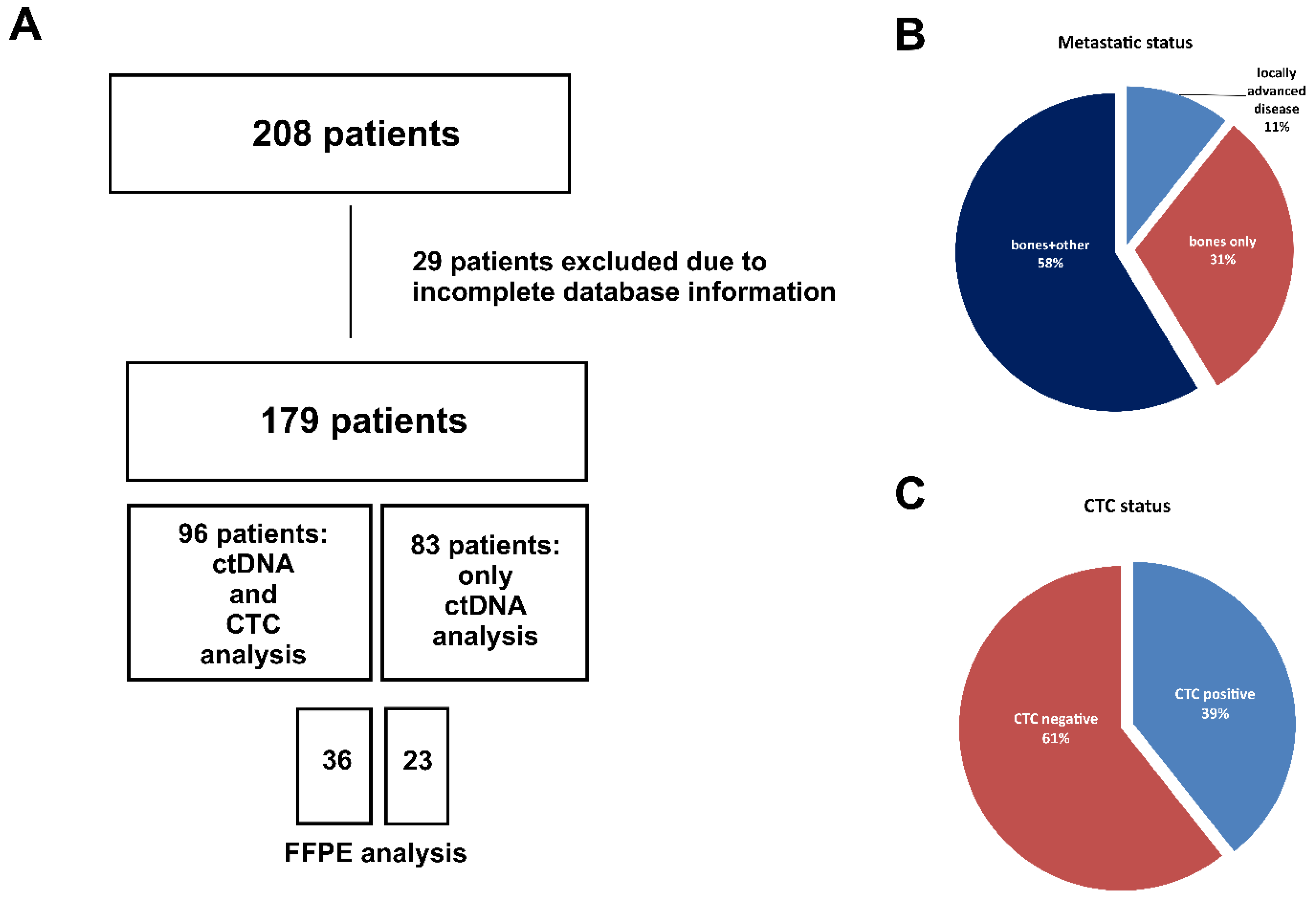

2.1. Patients Characteristics

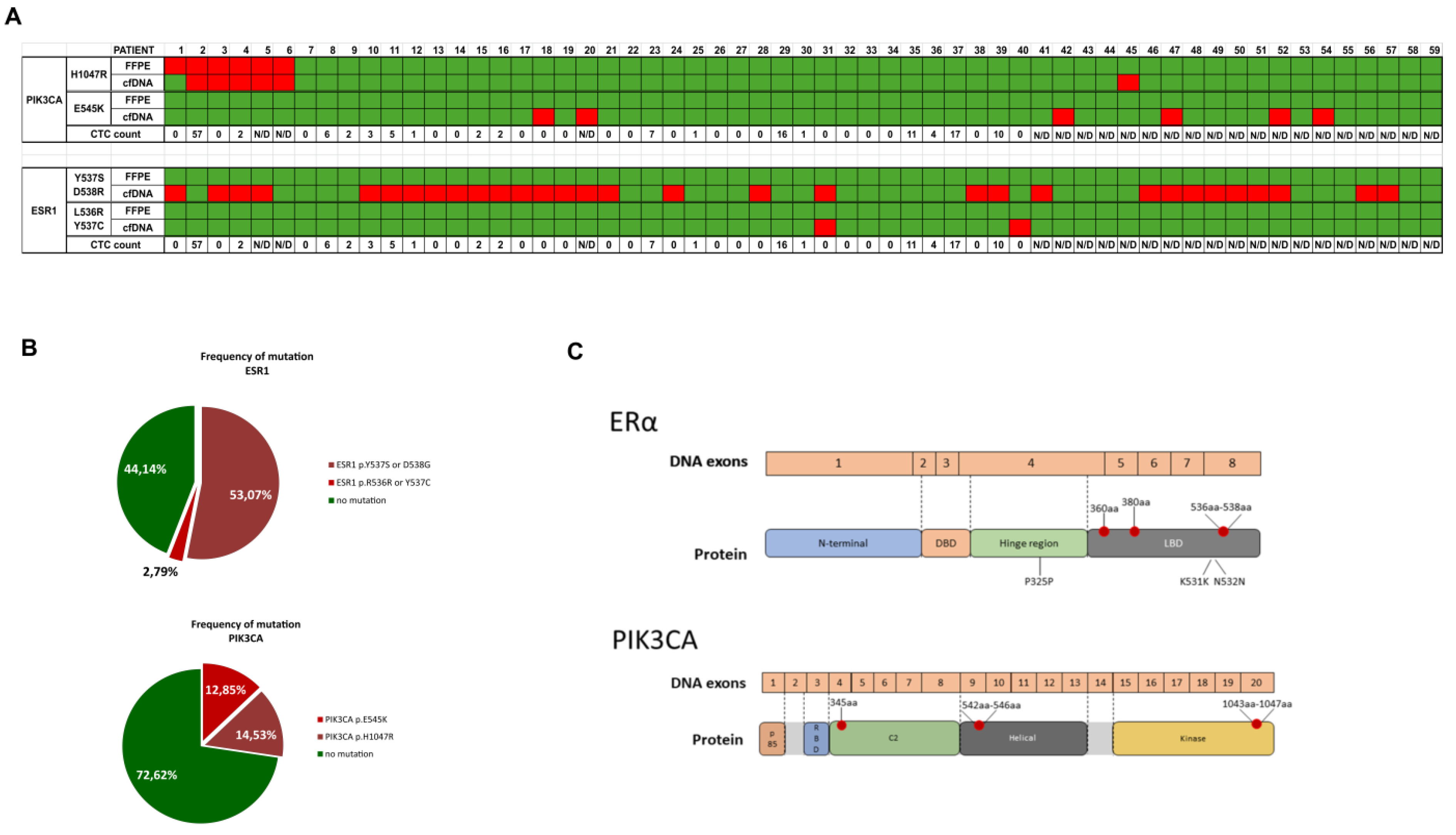

2.2. Mutations in cfDNA

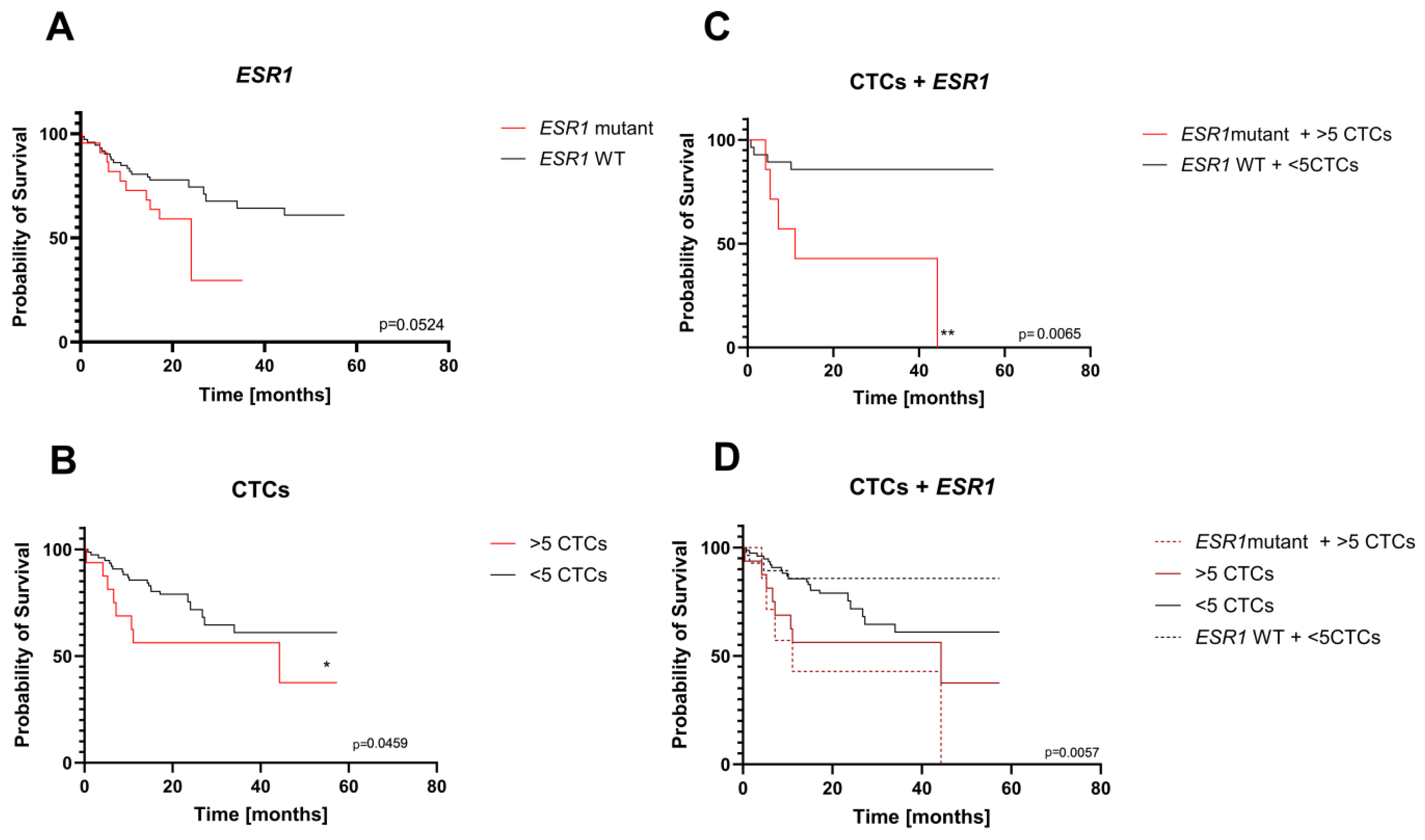

2.3. Clinical Value of Liquid Biopsy

- CTC evaluation

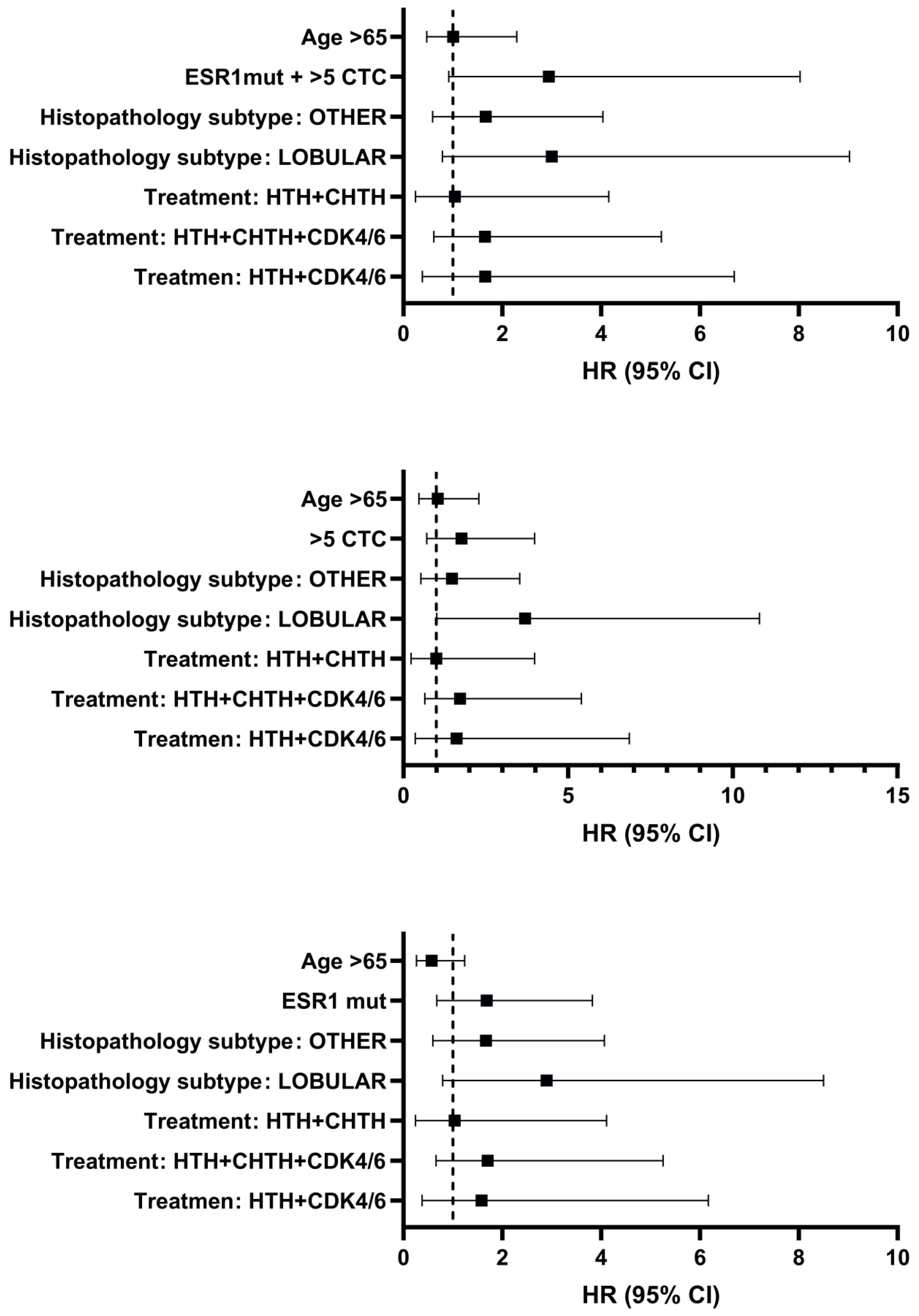

- Multivariable COX proportion and hazard regression analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients Samples

4.2. Isolation and Preparation of cfDNA

4.3. ddPCR Analysis

4.4. Post-Analysis for ddPCR

4.5. CTCs Assessment

4.6. FFPE Analysis

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| mBC | metastatic breast cancer |

| CTC | circulating tumor cell |

| ctDNA | circulating tumor DNA |

| cfDNA | circulating free DNA |

| ER | estrogen receptor |

| PR | progesteron receptor |

| LBD | ligand binding domain |

| PDX | patient-derived tumor xenograft |

| EV | extracellular vesicle |

| HR | hazard ratio |

| CI | confidence intervals |

| PFS | progression free survival |

| OS | overall survival |

| MAF | mutant allele frequency |

References

- Kittaneh, M.; Montero, A. J.; Glück, S. Molecular profiling for breast cancer: a comprehensive review. Biomark. Cancer 2013, 5, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedersen, R. N.; Esen, B. Ö.; Mellemkjær, L.; Christiansen, P.; Ejlertsen, B.; Lash, T. L.; Nørgaard, M.; Cronin-Fenton, D. The incidence of breast cancer recurrence 10-32 years after primary diagnosis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2022, 114, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aitken, S. J.; Thomas, J. S.; Langdon, S. P.; Harrison, D. J.; Faratian, D. Quantitative analysis of changes in ER, PR and HER2 expression in primary breast cancer and paired nNodal metastases. Ann. Oncol. 2009, 21, 1254–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, C.; Miller, N.; Geddie, W.; Gianfelice, D.; Oldfield, M.; Dranitsaris, G.; Clemons, M. J. Does confirmatory tumor biopsy alter the management of breast cancer patients with distant metastases? Ann. Oncol. 2009, 20, 1499–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeselsohn, R.; Yelensky, R.; Buchwalter, G.; Frampton, G.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A. M.; Ferrer-Lozano, J.; Perez-Fidalgo, J. A.; Cristofanilli, M.; Goḿez, H.; Arteaga, C. L.; Giltnane, J.; Balko, J. M.; Cronin, M. T.; Jarosz, M.; Sun, J.; Hawryluk, M.; Lipson, D.; Otto, G.; Ross, J. S.; Dvir, A.; Soussan-Gutman, L.; Wolf, I.; Rubinek, T.; Gilmore, L.; Schnitt, S.; Come, S. E.; Pusztai, L.; Stephens, P.; Brown, M.; Miller, V. A. Emergence of constitutively active estrogen receptor-α mutations in pretreated advanced estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1757–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.R.; Wu, Y.; Vats, P.; Su, F.; Lonigro, R.J.; Cao, X.; Kalyana-Sundaram, S.; Wang, R.; Ning, Y.; Hodges, L.; Gursky, A.; Siddiqui, J.; Tomlins, S.A.; Roychowdhury, S.; Pienta, K.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Roberts, J.S.; Rae, J.M.; Van Poznak, C.H.; Hayes, D.D.; Chugh, R.; Kunju, L.P.; Talpaz, M.; Schott, A.F.; Chinnaiyan, A.M. Activating ESR1 mutations in hormone-resistant metastatic breast cancer. Nat Genet. 45. [CrossRef]

- Toy, W.; Shen, Y.; Won, H.; Green, B.; Sakr, R. A.; Will, M.; Gala, K.; Fanning, S.; King, T. A.; Hudis, C.; Chen, D.; Hortobagyi, G.; Greene, G.; Berger, M.; Baselga, J.; Chandarlapaty, S. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations in hormone-resistant breast cancer. Nat. Genet. 2013, 45, 1439–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toy, W.; Weir, H.; Razavi, P.; Lawson, M.; Goeppert, A. U.; Marie, A.; Smith, A.; Wilson, J.; Morrow, C.; Wong, W. L.; De, E.; Carlson, K. E.; Martin, T. S.; Uddin, S.; Li, Z.; Katzenellenbogen, J. A.; Greene, G.; Baselga, J.; Chandarlapaty, S. Activating ESR1 mutations differentially affect the efficacy of ER antagonists. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7(3), 277–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciruelos Gil, E. M. Targeting the PI3K/AKT/MTOR pathway in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2014, 40, 862–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, N.; Malapelle, U.; Fassan, M.; Marchiò, C.; Buglioni, S.; Zupo, S.; Criscitiello, C.; Vigneri, P.; Dei Tos, A. P.; Maiorano, E.; Viale, G. PIK3CA mutations as a molecular target for hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuels, Y.; Wang, Z.; Bardelli, A.; Silliman, N.; Ptak, J.; Szabo, S.; Yan, H.; Gazdar, A.; Powell, S. M.; Riggins, G. J.; Willson, J. K. V.; Markowitz, S.; Kinzler, K. W.; Vogelstein, B.; Velculescu, V. E. High Frequency of mutations of the PIK3CA gene in human cancers. Science. 2004, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- André, F.; Ciruelos, E.; Rubovszky, G.; Campone, M.; Loibl, S.; Rugo, H. S.; Iwata, H.; Conte, P.; Mayer, I. A.; Kaufman, B.; Yamashita, T.; Lu, Y.-S.; Inoue, K.; Takahashi, M.; Pápai, Z.; Longin, A.-S.; Mills, D.; Wilke, C.; Hirawat, S.; Juric, D. Alpelisib for PIK3CA -mutated, hormone receptor–positive advanced breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1929–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schagerholm, C.; Robertson, S.; Toosi, H.; Sifakis, E. G.; Hartman, J. PIK3CA mutations in endocrine-resistant breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Abreu, M. T.; Palafox, M.; Asghar, U.; Rivas, M. A.; Cutts, R. J.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Pearson, A.; Guzman, M.; Rodriguez, O.; Grueso, J.; Bellet, M.; Cortés, J.; Elliott, R.; Pancholi, S.; Baselga, J.; Dowsett, M.; Martin, L. A.; Turner, N. C.; Serra, V. Early adaptation and acquired resistance to CDK4/6 Inhibition in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 2301–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, K.; Liu, P.; Geng, Y.; Wang, B.; Gan, W.; Guo, J.; Wu, F.; Chin, Y. R.; Berrios, C.; Lien, E. C.; Toker, A.; DeCaprio, J. A.; Sicinski, P.; Wei, W. Inhibition of Rb phosphorylation leads to MTORC2-mediated activation of Akt. Mol. Cell 2016, 62, 929–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X. Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2015, 5, 402–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alix-Panabières, C.; Pantel, K. Liquid biopsy: from discovery to clinical application. Cancer Discov. 2021, 11, 858–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Lin, H.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, D.; Lai, M.; Xi, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, T. Research progress of CTC, CtDNA, and EVs in cancer liquid biopsy. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawson, S.-J.; Tsui, D. W. Y.; Murtaza, M.; Biggs, H.; Rueda, O. M.; Chin, S.-F.; Dunning, M. J.; Gale, D.; Forshew, T.; Mahler-Araujo, B.; Rajan, S.; Humphray, S.; Becq, J.; Halsall, D.; Wallis, M.; Bentley, D.; Caldas, C.; Rosenfeld, N. Analysis of circulating tumor DNA to monitor metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013, 368, 1199–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Guo, X.; Ma, X. Predictive value of circulating cell-free DNA in the survival of breast cancer patients a systemic review and meta-analysis. Med. (United States) 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. H.; Jeong, H.; Choi, J. W.; Oh, H. E.; Kim, Y. S. Liquid biopsy prediction of axillary lymph node metastasis, cancer recurrence, and patient survival in breast cancer a meta-analysis. Med. (United States) 2018, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavon, G.; Hrebien, S.; Garcia-murillas, I.; Cutts, R. J.; Tarazona, N.; Fenwick, K.; Kozarewa, I.; Lopez-knowles, E.; Ribas, R.; Nerurkar, A.; Osin, P.; Chandarlapaty, S.; Dowsett, M.; Smith, I. E.; Turner, N. C. Analysis of ESR1 mutation in circulating tumor DNA demonstrates evolution during therapy for metastatic breast cancer. Sci Transl Med. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moynahan, M. E.; Chen, D.; He, W.; Sung, P.; Samoila, A.; You, D.; Bhatt, T.; Patel, P.; Ringeisen, F.; Hortobagyi, G. N.; Baselga, J.; Chandarlapaty, S. Correlation between PIK3CA mutations in cell-free DNA and everolimus efficacy in HR+, HER2-advanced breast cancer: results from BOLERO-2. Br. J. Cancer 2017, 116, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Leary, B.; Hrebien, S.; Morden, J. P.; Beaney, M.; Fribbens, C.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Bartlett, C. H.; Koehler, M.; Cristofanilli, M.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Bliss, J. M.; Turner, N. C. Early circulating tumor DNA dynamics and clonal selection with palbociclib and fulvestrant for breast cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaney, S. M.; Toi, M.; Neven, P.; Sohn, J.; Grischke, E. M.; Llombart-Cussa, A.; Soliman, H.; Wang, H.; Wijayawardana, S.; Jansen, V. M.; Litchfield, L. M.; Sledge, G. W. Clinical significance of PIK3CA and ESR1 mutations in circulating tumor DNA: analysis from the MONARCH 2 study of abemaciclib plus fulvestrant. Clin. Cancer Res. 2022, 28, 1500–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandarlapaty, S.; Chen, D.; He, W.; Sung, P.; Samoila, A.; You, D.; Bhatt, T.; Patel, P.; Voi, M.; Gnant, M.; Hortobagyi, G.; Baselga, J.; Moynahan, M. E. Prevalence of ESR1 mutations in cell-free DNA and outcomes in metastatic breast cancer: a secondary analysis of the BOLERO-2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1310–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosele, F.; Stefanovska, B.; Lusque, A.; Tran Dien, A.; Garberis, I.; Droin, N.; Le Tourneau, C.; Sablin, M. P.; Lacroix, L.; Enrico, D.; Miran, I.; Jovelet, C.; Bièche, I.; Soria, J. C.; Bertucci, F.; Bonnefoi, H.; Campone, M.; Dalenc, F.; Bachelot, T.; Jacquet, A.; Jimenez, M.; André, F. Outcome and molecular landscape of patients with PIK3CA-mutated metastatic breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 377–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’leary, B.; Cutts, R. J.; Huang, X.; Hrebien, S.; Liu, Y.; André, F.; Loibl, S.; Loi, S.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Cristofanilli, M.; Bartlett, C. H.; Turner, N. C. Circulating tumor DNA, markers for early progression on fulvestrant with or without palbociclib in ER+ Advanced Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2021, 113, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, J.; Gil-Gil, M.; Proszek, P.; Zielinski, C.; Reay, A.; Ruiz-Borrego, M.; Cutts, R.; Ciruelos Gil, E. M.; Feber, A.; Muñoz-Mateu, M.; Swift, C.; Bermejo, B.; Herranz, J.; Vila, M. M.; Antón, A.; Kahan, Z.; Csöszi, T.; Liu, Y.; Fernandez-Garcia, D.; Garcia-Murillas, I.; Hubank, M.; Turner, N. C.; Martín, M. Baseline mutations and CtDNA dynamics as prognostic and predictive factors in ER-Positive/HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 2023, 29, 4166–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janni, W. J.; Rack, B.; Terstappen, L. W. M. M.; Pierga, J. Y.; Taran, F. A.; Fehm, T.; Hall, C.; De Groot, M. R.; Bidard, F. C.; Friedl, T. W. P.; Fasching, P. A.; Brucker, S. Y.; Pantel, K.; Lucci, A. Pooled analysis of the prognostic relevance of circulating tumor cells in primary breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 22, 2583–2593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidard, F. C.; Michiels, S.; Riethdorf, S.; Mueller, V.; Esserman, L. J.; Lucci, A.; Naume, B.; Horiguchi, J.; Gisbert-Criado, R.; Sleijfer, S.; Toi, M.; Garcia-Saenz, J. A.; Hartkopf, A.; Generali, D.; Rothe, F.; Smerage, J.; Muinelo-Romay, L.; Stebbing, J.; Viens, P.; Magbanua, M. J. M.; Hall, C. S.; Engebraaten, O.; Takata, D.; Vidal-Martınez, J.; Onstenk, W.; Fujisawa, N.; Diaz-Rubio, E.; Taran, F. A.; Cappelletti, M. R.; Ignatiadis, M.; Proudhon, C.; Wolf, D. M.; Bauldry, J. B.; Borgen, E.; Nagaoka, R.; Carañana, V.; Kraan, J.; Maestro, M.; Brucker, S. Y.; Weber, K.; Reyal, F.; Amara, D.; Karhade, M. G.; Mathiesen, R. R.; Tokiniwa, H.; Llombart-Cussac, A.; Meddis, A.; Blanche, P.; D’Hollander, K.; Pantel, K. Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients treated by neoadjuvant chemotherapy: a meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2018, 110, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerratana, L.; Davis, A. A.; Zhang, Q.; Basile, D.; Rossi, G.; Strickland, K.; Franzoni, A.; Allegri, L.; Mu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Flaum, L. E.; Damante, G.; Gradishar, W. J.; Platanias, L. C.; Behdad, A.; Yang, H.; Puglisi, F.; Cristofanilli, M. Longitudinal dynamics of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor DNA for treatment monitoring in metastatic breast cancer. JCO Precis. Oncol. 2021, 5, 943–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magbanua, M.J.M.; Hendrix, L.H.; Hyslop, T.; Barry, W.T.; Winer, E.P.; Hudis, C.; Toppmyer, D.; Carey, L.A.; Partidge, A.H. ; Pierga, JY; Fehm, T.; Vidal-Martinez, J.; Mavroudis, D.; Garcia-Saenz, J.A.; Stebbing, J.;Gazzaniga, P.; Manso, L.; Zamarchi, R.; Antelo, M.L.; De Mattos-Aruda, L.; Generali, D.; Caldas, C.; Munzone, E.; Dirix, C.; L Delson, A.; Burstein, H.J.; Quadir, M.; Ma Cynthia; Scott, J.H.; Bidard, F.C.; Park, J.W.; Rugo, H.S. Serial analysis of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. [CrossRef]

- Szostakowska-Rodzos, M.; Fabisiewicz, A.; Wakula, M.; Tabor, S.; Szafron, L.; Jagiello-Gruszfeld, A.; Grzybowska, E. A. Longitudinal analysis of circulating tumor cell numbers improves tracking metastatic breast cancer progression. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Riethdorf, S.; Wu, G.; Wang, T.; Yang, K.; Peng, G.; Liu, J.; Pantel, K. Meta-analysis of the prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 5701–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riethdorf, S.; Muller, V.; Loibl, S.; Nekljudova, V.; Weber, K.; Huober, J.; Fehm, T.; Schrader, I.; Hilfrich, J.; Holms, F.; Tesch, H.; Schem, C.; von Minckwitz, G.; Untch, M.; Pantel, K. Prognostic impact of circulating tumor cells for breast cancer patients treated in the neoadjuvant "Geparquattro" trial. Clin Cancer Res. 5384. [Google Scholar]

- Smit, D. J.; Schneegans, S.; Pantel, K. Clinical applications of circulating tumor cells in patients with solid tumors. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2024, 41, 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, S. L.; Liu, X.; Tan, S. J.; Tai, J. A.; Phua, L. Y.; Poh, H. M.; Yeo, T.; Chua, Y. W.; Haw, Y. X.; Ling, W. H.; Ng, R. C. H.; Tan, T. J.; Loh, K. W. J.; Tan, D. S. W.; Ng, Q. S.; Ang, M. K.; Toh, C. K.; Lee, Y. F.; Lim, C. T.; Lim, T. K. H.; Hillmer, A. M.; Yap, Y. S.; Lim, W. T. Complementary sequential circulating tumor cell (CTC) and cell-free tumor DNA (CtDNA) profiling reveals metastatic heterogeneity and genomic changes in lung cancer and breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 698551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, G.; Mu, Z.; Rademaker, A. W.; Austin, L. K.; Strickland, K. S.; Costa, R. L. B.; Nagy, R. J.; Zagonel, V.; Taxter, T. J.; Behdad, A.; Wehbe, F. H.; Platanias, L. C.; Gradishar, W. J.; Cristofanilli, M. Cell-free DNA and circulating tumor cells: comprehensive liquid biopsy analysis in advanced breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 24, 560–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madic, J.; Kiialainen, A.; Bidard, F. C.; Birzele, F.; Ramey, G.; Leroy, Q.; Frio, T. R.; Vaucher, I.; Raynal, V.; Bernard, V.; Lermine, A.; Clausen, I.; Giroud, N.; Schmucki, R.; Milder, M.; Horn, C.; Spleiss, O.; Lantz, O.; Stern, M. H.; Pierga, J. Y.; Weisser, M.; Lebofsky, R. Circulating tumor DNA and circulating tumor cells in metastatic triple negative breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, 2158–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto-Ibusuki, M.; Tomiguchi, M.; Sueta, A.; Murakami, K.; Omoto, Y.; Iwase, H. Analysis of ESR1 and PIK3CA mutations in plasma cell-free DNA from ER-positive breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 52142–52155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuqua, S. A. W.; Rechoum, Y.; Gu, G. ESR1 mutations in cell-free DNA of breast cancer: predictive “Tip of the Iceberg. ” JAMA Oncol. 2016, 2, 1315–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raei, M.; Heydari, K.; Tabarestani, M.; Razavi, A.; Mirshafiei, F.; Esmaeily, F.; Taheri, M.; Hoseini, A.; Nazari, H.; Shamshirian, D.; Alizadeh-Navaei, R. Diagnostic Accuracy of ESR1 mutation detection by cell-free DNA in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. BMC Cancer 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, Y.; Zhao, F.; Song, G.; Rugo, H. S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, X.; Shao, B.; Yang, L.; Liu, Y.; Ran, R.; Zhang, R.; Guan, Y.; Chang, L.; Yi, X. Plasma PIK3CA CtDNA specific mutation detected by Next Generation Sequencing is associated with clinical outcome in advanced breast cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2018, 8, 1873–1886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Shen, D.; Shao, J.; Crowder, R.; Liu, W.; Prat, A.; He, X.; Liu, S.; Hoog, J.; Lu, C.; Ding, L.; Griffith, O. L.; Miller, C.; Larson, D.; Fulton, R. S.; Harrison, M.; Mooney, T.; McMichael, J. F.; Luo, J.; Tao, Y.; Goncalves, R.; Schlosberg, C.; Hiken, J. F.; Saied, L.; Sanchez, C.; Giuntoli, T.; Bumb, C.; Cooper, C.; Kitchens, R. T.; Lin, A.; Phommaly, C.; Davies, S. R.; Zhang, J.; Kavuri, M. S.; McEachern, D.; Dong, Y. Y.; Ma, C.; Pluard, T.; Naughton, M.; Bose, R.; Suresh, R.; McDowell, R.; Michel, L.; Aft, R.; Gillanders, W.; DeSchryver, K.; Wilson, R. K.; Wang, S.; Mills, G. B.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.; Edwards, J. R.; Maher, C.; Perou, C. M.; Mardis, E. R.; Ellis, M. J. Endocrine-therapy-resistant ESR1 variants revealed by genomic characterization of breast-cancer-derived Xenografts. Cell Rep. 2013, 4, 1116–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keup, C.; Storbeck, M.; Hauch, S.; Hahn, P.; Sprenger-Haussels, M.; Hoffmann, O.; Kimmig, R.; Kasimir-Bauer, S. Multimodal targeted deep sequencing of circulating tumor cells and matched cell-free DNA provides a more comprehensive tool to identify therapeutic targets in metastatic breast cancer patients. Cancers 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeshita, T.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yamamoto-Ibusuki, M.; Inao, T.; Sueta, A.; Fujiwara, S.; Omoto, Y.; Iwase, H. Clinical significance of monitoring ESR1 mutations in circulating CfDNA in ER positive breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 32504–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zundelevich, A.; Dadiani, M.; Kahana-Edwin, S.; Itay, A.; Sella, T.; Gadot, M.; Cesarkas, K.; Farage-Barhom, S.; Saar, E. G.; Eyal, E.; Kol, N.; Pavlovski, A.; Balint-Lahat, N.; Dick-Necula, D.; Barshack, I.; Kaufman, B.; Gal-Yam, E. N. Erratum. ESR1 mutations are frequent in newly diagnosed metastatic and loco-regional recurrence of endocrine-treated breast cancer and carry worse prognosis. Breast Cancer Res. 2020, 22, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, S. H.; Yang, H. N.; Jeon, S. Y.; Lee, K. S.; Park, I. H. Mutation analysis using cell-free DNA for endocrine therapy in patients with HR+ metastatic breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, D. J. E.; Van Dam, P. J.; Van Den Eynden, G. G. M.; Rutten, A.; Wuyts, H.; Pouillon, L.; Peeters, M.; Pauwels, P.; Van Laere, S. J.; Van Dam, P. A.; Vermeulen, P. B.; Dirix, L. Y. Detection and prognostic significance of circulating tumour cells in patients with metastatic breast cancer according to immunohistochemical subtypes. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisiewicz, A.; Szostakowska-Rodzos, M.; Zaczek, A. J.; Grzybowska, E. A. Circulating tumor cells in early and advanced breast cancer; biology and prognostic value. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Q.; Gong, L.; Zhang, T.; Ye, J.; Chai, L.; Ni, C.; Mao, Y. Prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2016, 18, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magbanua, M. J. M.; Savenkov, O.; Asmus, E. J.; Ballman, K. V.; Scott, J. H.; Park, J. W.; Dickler, M.; Partridge, A.; Carey, L. A.; Winer, E. P.; Rugo, H. S. Clinical significance of circulating tumor cells in hormone receptor–positive metastatic breast cancer patients who received letrozole with or without bevacizumab. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 4911–4920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabisiewicz, A.; Szostakowska-Rodzos, M.; Grzybowska, E. A. Improving the prognostic and predictive value of circulating tumor cell enumeration: is longitudinal monitoring the answer? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandez-Garcia, D.; Hills, A.; Page, K.; Hastings, R. K.; Toghill, B.; Goddard, K. S.; Ion, C.; Ogle, O.; Boydell, A. R.; Gleason, K.; Rutherford, M.; Lim, A.; Guttery, D. S.; Coombes, R. C.; Shaw, J. A. Plasma cell-free DNA (CfDNA) as a predictive and prognostic marker in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Z.; Wang, C.; Wan, S.; Mu, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Abu-Khalaf, M. M.; Fellin, F. M.; Silver, D. P.; Neupane, M.; Jaslow, R. J.; Bhattacharya, S.; Tsangaris, T. N.; Chervoneva, I.; Berger, A.; Austin, L.; Palazzo, J. P.; Myers, R. E.; Pancholy, N.; Toorkey, D.; Yao, K.; Krall, M.; Li, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, X.; Xing, J.; Hou, L.; Wei, Q.; Li, B.; Cristofanilli, M.; Yang, H. Association of clinical outcomes in metastatic breast cancer patients with circulating tumour cell and circulating cell-free DNA. Eur. J. Cancer 2019, 106, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <63 | 89 |

| ≥63 | 90 |

| HER2 status | |

| HER2+ | 5 |

| HER- | 161 |

| N/D | 13 |

| No of meta sites | |

| 1 | 83 |

| 2 | 49 |

| ≥3 | 47 |

| Meta sites | |

| Bones | 133 |

| Liver | 67 |

| Lung | 58 |

| Other | 81 |

| Hitological subtype | |

| NST | 133 |

| Lobular | 16 |

| Other | 30 |

| Treatment | |

| HTH | 32 |

| HTH+CHTH | 36 |

| HTH+CDK4/6 | 26 |

| HTH+CHTH+CDK4/6 | 85 |

| Radiotherapy | |

| RTH+ | 100 |

| RTH- | 79 |

| Mutation | Frequency |

|---|---|

| PIK3CA p.E545K | 12,85% |

| PIK3CA p.H1047R | 14,53% |

| ESR1 p.Y537S or D538G | 53,07% |

| ESR1 p.R536R or Y537C | 2,79% |

| Variables | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| <65 | 50 |

| ≥65 | 46 |

| HER2 status | |

| HER2+ | 5 |

| HER- | 86 |

| N/D | 5 |

| No of meta sites | |

| 1 | 58 |

| 2 | 27 |

| ≥3 | 21 |

| Meta sites | |

| Bones | 70 |

| Liver | 32 |

| Lung | 26 |

| Other | 36 |

| Hitological subtype | |

| NST | 75 |

| Other | 21 |

| Treatment | |

| HTH | 22 |

| HTH+CHTH | 15 |

| HTH+CDK4/6 | 14 |

| HTH+CHTH+CDK4/6 | 45 |

| Radiotherapy | |

| RTH+ | 46 |

| RTH- | 50 |

| ESR1 status | |

| ESR1 mutation | 58 |

| ESR1 WT | 38 |

| Clinical variable | Reference level |

|---|---|

| Treatment | HTH |

| Histopathological subtype | NST |

| Age | <65 |

| Univariable analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95 CI | p-value |

| ESR1 mutation | 0,5832 | 0,2853-1,186 | 0,1339 |

| >5 CTCs | 1,775 | 0,7423-3,821 | 0,1636 |

| ESR1 mut + >5CTCs | 3,496 | 1,173-8,484 | 0,0113 |

| Multivariable analysis | |||

| Variable | HR | 95 CI | p-value |

| ESR1 mutation | 0,5616 | 0,2686-1,165 | 0,1197 |

| >5 CTCs | 1,814 | 0,7310-4,124 | 0,1714 |

| ESR1 mut + >5CTCs | 3,538 | 1,126-9,403 | 0,0172 |

| Mutation | Probe sequence | Primer sequence | |

|---|---|---|---|

| L536R | [6FAM]TGGTGCCCCGCTATGACC[BHQ1] | F | F 5’AGGCATGGAGCATCTGTACA3’ |

| R | 5’TTGGTCCGTCTCCTCCA3’ | ||

| Y537S | [6FAM]TGGTGCCCCTCTCTGACCT[BHQ1] | F | F 5’AGGCATGGAGCATCTGTACA3’ |

| R | 5’TTGGTCCGTCTCCTCCA3’ | ||

| D538G | [6FAM]CCCTCTATGGCCTGCTGCT[BHQ1] | F | F 5’AGGCATGGAGCATCTGTACA3’ |

| R | 5’TTGGTCCGTCTCCTCCA3’ | ||

| Y537C | [6FAM]TGCCCCTCTGTGACCTGCT[BHQ1] | F | F 5’AGGCATGGAGCATCTGTACA3’ |

| R | 5’TTGGTCCGTCTCCTCCA3’ | ||

| WT ESR1 | [HEX]TGGTGCCCCTCTATGACCTG[BHQ1] | F | F 5’AGGCATGGAGCATCTGTACA3’ |

| R | 5’TTGGTCCGTCTCCTCCA3’ | ||

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer | Product lenght |

|---|---|---|---|

| ESR1 exon 8 | 5’- TCTGTGTCTTCCCACCTACAGT-3’ | 5’- ATGCGATGAAGTAGAGCCCG-3’ | 200bp |

| PIK3CA exon 9 | 5’- AGCTAGAGACAATGAATTAAGGGA -3’ | 5’- TCCATTTTAGCACTTACCTGTGAC -3’ | 130bp |

| PIK3CA exon 20 | 5’- AACTGAGCAAGAGGCTTTGGA -3’ | 5’- CAATCGGTCTTTGCCTGCTG -3’ | 200bp |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).