1. Introduction

The extensive utilization and continuous progress of digital technology across different domains result in manufacturing transformation, the emergence of new economic sectors, and a higher demand for engineering knowledge, influencing higher education. Employers value a combination of technical understanding, interdisciplinary knowledge, and soft skills that enable employees to excel in their roles. Furthermore, the percentage of graduates employed in their specialty is a vital indicator of universities' efficiency that has demanded the development of a learning environment that is conducive to the professional self-determination of students, their success and well-being in professional life [

1,

2,

3]. Equipping students for success in the workplace implies comprehensive and multidimensional approach combining academic education with industry- academia practical experience, and lifelong learning as an integral part of students' future careers. Regarding this issue, one of the top challenges in today's higher education is promoting equitable and responsive students' employability that is necessary for job seekers and highly valued by employers.

Employability, being a complex phenomenon, has definitions that vary greatly. Some approaches prioritize students' knowledge and skills, while others focus on their willingness to adapt to the demands of the labour market. Researchers state that employability skills, or soft skills related to personality, attitude and behaviour could allow graduates to apply better their academic skills [

4,

5,

6].

Sanders and de Grip (2004) considered employability definitions to be diverging because of changing labour market landscape and government policies [

7]. The definition of employability by Davies (2000) highlights the utilization of employability skills learned in one situation across various workplace scenarios [

8]. Employability skills are personal qualities that help future specialists take initiative, bring innovation to their workplace, and succeed in the labour market [

9].

Employability skills can be defined as the combination of skills and attributes necessary to secure and maintain meaningful employment over one's professional journey [

10]. 60% of employees strongly believe that soft skills are a significant factor while hiring [

11].

This research views employability as the 'transferable skills' required for effective performance in any job sector and are not limited to a specific career. These skills include leadership and teamwork qualities, effective communication, self-management abilities, and problem-solving skills being essential for the successful career development.

Some researchers argue that the curriculum should prioritize employability and develop creative, confident, and articulate graduates [

12]. Social cognitive career theory, being the extension of career theory, emphasizes feedback and feed-forward mechanisms and explains how motivation, self-efficacy, and interest influence career development and decision-making. Syrkov A. states that when students believe their goals are important, they will experience higher motivation [

13]. Developing employability skills relies on the pedagogical conditions [

14,

15].

Metacognition pedagogy implies students actively participating in the studies, considering their cognitive styles [

16,

17,

18].

In the study, Rothwell A. analyzes the factors that contribute to readiness for professional activity, giving particular attention to abilities and personal qualities [

19]. Zyberaj J. and other researchers focus on motivation in career development learning and students' professional plans during a Pandemic [

20,

21,

22].

In the scientific literature, two ways of perceiving employability are described: an individual-centered approach focusing on self-assessment of one's potential for employment and situational one aimed at considering situational factors like socio-economic situation, industry–academic partnerships, particularities of the labour market [23,24]. Situational factors are what set perceived employability apart from self-efficacy [

25,

26]. Although the problem of readiness for professional activity and employability of students is of high importance, the ways of the development of employability skills of engineering students are not well-explored yet.

When it comes to the competencies of engineering students, technical aspects come to mind, while foreign language skills and soft skills also increase employability. ESP course often focuses on technical vocabulary only and aims at developing reading and writing skills without giving enough time to soft skills. However, soft skills and command of English are important employability factors [

27,

28,

29].

This study aims to develop an ESP course that can scale up students’ employability enhancing their strengths and developing soft skills.

The study addresses the following research questions:

-What soft skills do students consider to be relevant in order to get a job in their field?

-What can be done to improve the employability of engineering students within ESP classes?

Based on the data we collected, we identified the skills that graduates are lacking and the skills that are adequately addressed in the current curriculum. The identified soft skills including social and personal serve as the foundation of the ESP course proposed framework.

The ESP course developed allows a better alignment between students' soft skills they need and the aimed skills covered in the academic curriculum, and thus enhancing graduates' future employability.

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical data processing and data graphical presentation were performed by means of the computer programme Statistica 12.0 (StatSoft). For the variables under study, sample averages, standard deviations (SD), midpoints, first and third quarters are calculated. The nonparametric Mann-Whitney Z-criteria for independent samples and the Wilcoxon Z-criterion for dependent (correlated) samples were used to compare student groups. Statistically significant differences were considered at p<0.05, where p is the Type I error probability when testing the null hypothesis.

2.1. Research Design

The theoretical foundations of our research are based on metacognition pedagogy and social cognitive theory. We consider metacognition pedagogy to support the purpose of learning, develop the students' metacognitive understanding. Social cognitive theory examines learning’s cognitive aspects within social contexts, highlighting the interplay between individuals, surroundings, and actions. In their turn, personal outcome expectations, goals, and values are manifested in the students' actions. We have formulated the following contextual factors of employability pedagogy based on the theories of Pintrich, and Yorke and Knight [

30,

31] (

Table 1).

Experimental English language training for specific purposes was conducted within the second-year curricula of undergraduate students of Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University during the 2023–2024 academic year (two academic semesters). The Mining University was chosen as an experimental base because its graduates traditionally excel in the engineering field. Additionally, the university ranked in the top 20 of Quacquarelli Symonds rankings, with a score of 94.3 out of 100 based on employers' opinions. We formed the experimental and control groups using the randomization method.

Our mission was seen as the simultaneous development of engineering students' English proficiency and employability skills through an integrative approach. The research process included identifying the needs of ESP engineering students, collecting data, planning the research, designing instructions, developing an interdisciplinary course for foreign language teaching, conducting pre and post-experiment tests, and analyzing the test results.

An integrative model was used to teach engineering students in the ESP course, aimed at enhancing employability skills.

Each group comprised 100 students, chosen based on their proficiency in English at the B1 level, in accordance with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. The control group included 100 students, consisting of 39 men and 61 women, all aged between 17 and 19. In contrast, the experimental group also comprised 100 participants, with 46 boys and 44 girls, within the same age range of 17 to 19. Students in the control group were taught via traditional teaching methods and resources during the educational experiment.

In order to determine the needs of the engineering students studying English at Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University, a needs analysis test was administered including a diagnostic testing and the learning style assessment.

We ensure that every willing participant is informed about the research goal, and we guarantee the confidentiality and anonymity of their data.

Engineering students are often the target group for soft skills development as traditionally their hard skills outweigh [

32,

33].

Researchers and training practitioners focus on various aspects of soft skills and apply different technologies to develop them [

34,

35]. Soft skills are commonly defined as nontechnical skills enabling individuals to perform effectively when communicating with colleagues or partners. Soft skills are considered to be as important as hard skills for a professional in any field [

36].

For the purpose of this research we divide soft skills into two major groups, namely social skills and personal skills. Within the first group we focus on effective communication, empathy, active listening, and conflict resolution. The second group contains motivation, self-regulation, critical thinking, and self-awareness (

Table 2).

Soft skills are difficult to measure as they are mostly revealed in practical activity. The performance or result of certain work where soft skills are deployed is often a criterion of their development.

However, the following assessment methods allow us to find correlations between soft skills and factors that can be measured.

2.1.1. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale

To assess the development of soft skills two methods were used. We compared the results of the two methods to see whether they aligned. It ensured reliability of the experimental results. The first method used is the Career Adapt-Abilities Scale (CAAS) that is a tool for assessing the adaptive resources that an employee has and uses to solve occupational tasks. This form consists of four scales measuring concern, control, curiosity, and confidence as psychosocial resources indicating readiness for professional activities. Divided into four subscales, these 24 items evaluate adaptability traits, including concern, control, curiosity, and confidence, with equal distribution [

37]. The concern subscale assesses the level of students' focus and readiness for their professional future. The control subscale measures a student's willingness to take responsibility for their professional growth. The curiosity subscale reflects a student's capacity to explore and acquire relevant information about the professional field and career prospects. The confidence subscale represents students' awareness of their competence in making professional decisions, reaching professional goals, and effectively handling stress. The CAAS can be completed in about 20 minutes. Participants rate their level of career adaptability on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1 = not strong, 5 = strongest) for each of the 24 items. Total score on each subscale ranges from 6 to 30 points, and overall employability skill rating is between 24 and 120 points.

This method is favoured for its simplicity and accuracy in evaluating career adaptability skills including soft skills. Furthermore, it allows investigating relationships between career adapt abilities factors and soft skills. The four factors of CAAS reflect the targeted soft skills (

Table 3).

Table 4 shows the questions suggested by students to assess employability skills.

2.1.2. Johari Window questionnaire

Students either aren't aware or do not realise their strengths and weaknesses or do not understand how other people perceive them. Johari's window questionnaire enabled us to understand the interconnectedness and interdependence of personal qualities seen from both the personal perspective and assessed by others. The engineering students were asked to select five adjectives to describe themselves and then their peers chose five ones which described their partner. Inserting these adjectives in a two-by-two grid of four cells is claimed to help students see themselves as others see them and be better able to use insight and introspection. This test provides a clear picture of the soft skills development (

Table 5).

2.2. Research Instruments

As the preliminary part of the study revealed a lack of English skills necessary to succeed in the workplace, we created an ESP course with an emphasis to the functional language use in context. Communication English skills are essential for engineering students since English is the dominant language of science and technology. Engineering students should be able to work with information in research periodicals and journals, take part in conferences, symposia, and seminars held in English. That’s why technical vocabulary, special terms used for describing experiments and research results, as well as soft skills serve as a base and target for the designed ESP course.

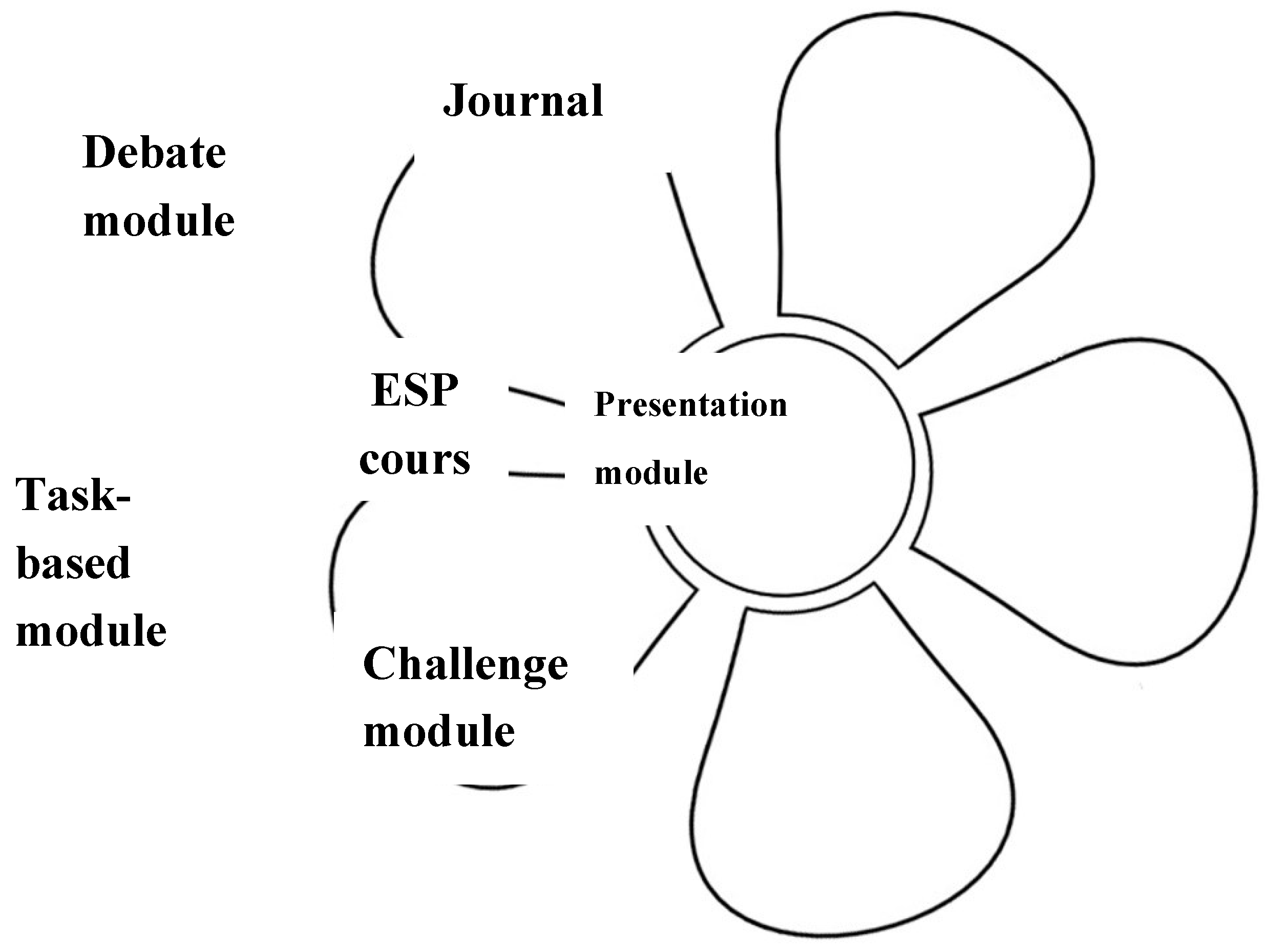

We selected authentic professionally oriented materials related to students’ motivation and effective leadership, with a view to gaining a competitive edge for the ESP course. The unique aspect of our ESP course is the emphasis on applying a holistic approach addressing soft skills along with technical vocabulary. The course consists of five modules, each corresponding to the career adapt abilities factors (concern, control, curiosity, confidence) and soft skills (social and personal) (

Figure 1).

All the modules improved career adaptability and developed soft skills with a focus on a particular factor and skill. The factors and soft skills corresponding to the modules are shown in

Table 6.

Research highlights that close connection of career adapt abilities factors results in the development of soft skills as part of employability skills.

Table 7 provides the ESP course description.

The debate module covers key terminology (argument, rebuttal, counterargument), debate structure (opening, rebuttals, closing statements) and roles (proposition, opposition, moderator). Having conflict resolution and self-regulation skills students navigate disagreements constructively and empathetically that is a key to productive debates and brings mutually beneficial outcomes. As far as career adapt abilities factors are concerned, control indicates the level of personal responsibility within debates. While fostering personal responsibility, students are taught to evaluate what they can control at each debate stage through completing a check-list as well as a to-do list in English.

Presentation module teaches students to deliver a tremendously impactful presentation following its preparation, delivery and assessment instructions. Students’ confidence directly impacts their communication skills. Active listening, asking questions, and feedback activities allow students to become confident in public speaking being essential at studies and the future work place.

Task-based learning module focuses on empathy and motivation skill development. Innate empathic ability is known to be more pronounced in some people compared to others. Learning empathy requires reflective feelings practice based on integrating thinking tasks and trigger questions into English language teaching. Development of control, concern career adapt abilities factors require active participation and interaction of students. In contrast to the traditional teaching approach, team-based learning aims at self-managed learning and enables the instructor to provide content expertise and at the same time monitor the whole group studies.

Challenge module allows students to build internal strength to cope with uncertainty through the exercises like sorting unforeseen events by risk level, reacting to changes, putting feelings into words and developing personal motivation. Active listening, self-presentation and asking open-ended questions to gather insights help students increase their self-regulation.

Journal module aims at ESP written communication. Students are taught how to read formulas, describe graphs and diagrams, use technical terminology and linking words, write abstracts, introductions, conclusions, and references. Critical thinking skills determine curiosity career adapt abilities factor development through considering different perspectives and using storytelling in English lessons. In the ESP course we give a ‘motivational text’. We compiled these texts in such a way that, after working with them, the students get ‘saturated’ with information on the topic; work with thematic vocabulary in the text; apply their knowledge in practice and finally give effective presentations delivering the results of their individual or group projects and drawing the conclusions (

Table 8).

Ongoing assessment and final assessment are used to evaluate what knowledge, abilities, and skills students have acquired.

The ongoing assessment is conducted through tests that contain questions on each module and are taken throughout the course upon completion of the experiment, the participants completed the ESP final test, indicating the results of English language acquisition in the experimental and control groups.

3. Results

The paper explores the ways of soft and foreign language skills simultaneous development being necessary for the engineering students to work in the mineral resource sector.

3.1. Outcome 1: the ESP course design

Since soft skills are seen as the basis of graduates’ employability, we have created the ESP course aimed at simultaneous development of the English proficiency and soft skills. Results of a needs analysis test and the learning style assessment showed that students’ needs are focused in their professional field.

3.2. Outcome 2: Participants’ employability skills development

A Diagnostic Test, CAAS papers and Johari Window Perspectives tests were administered before the ESP course and afterwards. Differences between students' results collected before and after studying the integrative course were examined.

The quantitative data collected through two sets of both CAAS papers and Johari Window Perspectives as well as processed by the statistical analysis methods have proved that we were able to simultaneously scale up employability and English proficiency of the engineering students in English lessons. The results showed a significant increase in the soft skills development between the pre- and after-ESP studies. Similarly, results of the experiment demonstrated a significant increase in the English language skills development.

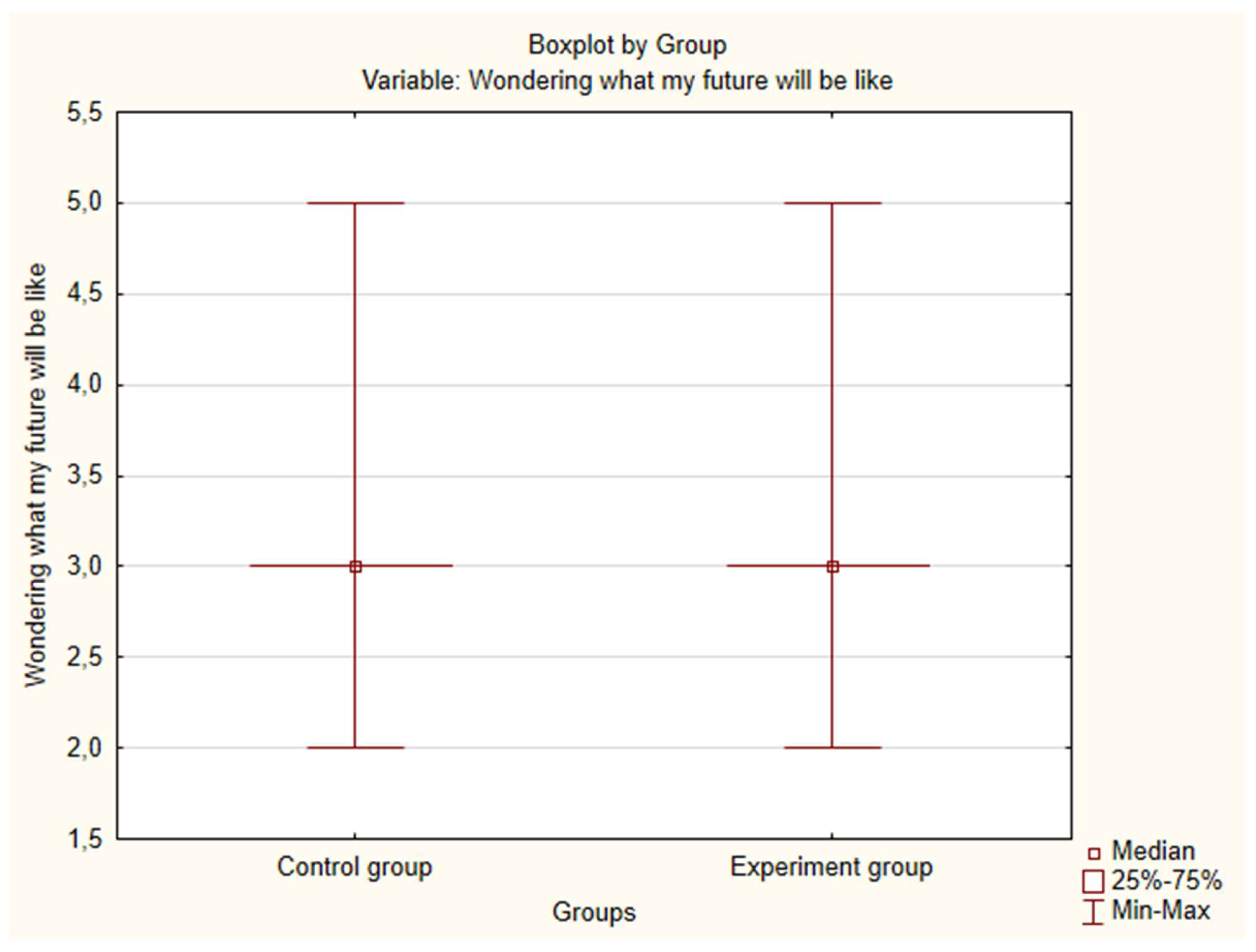

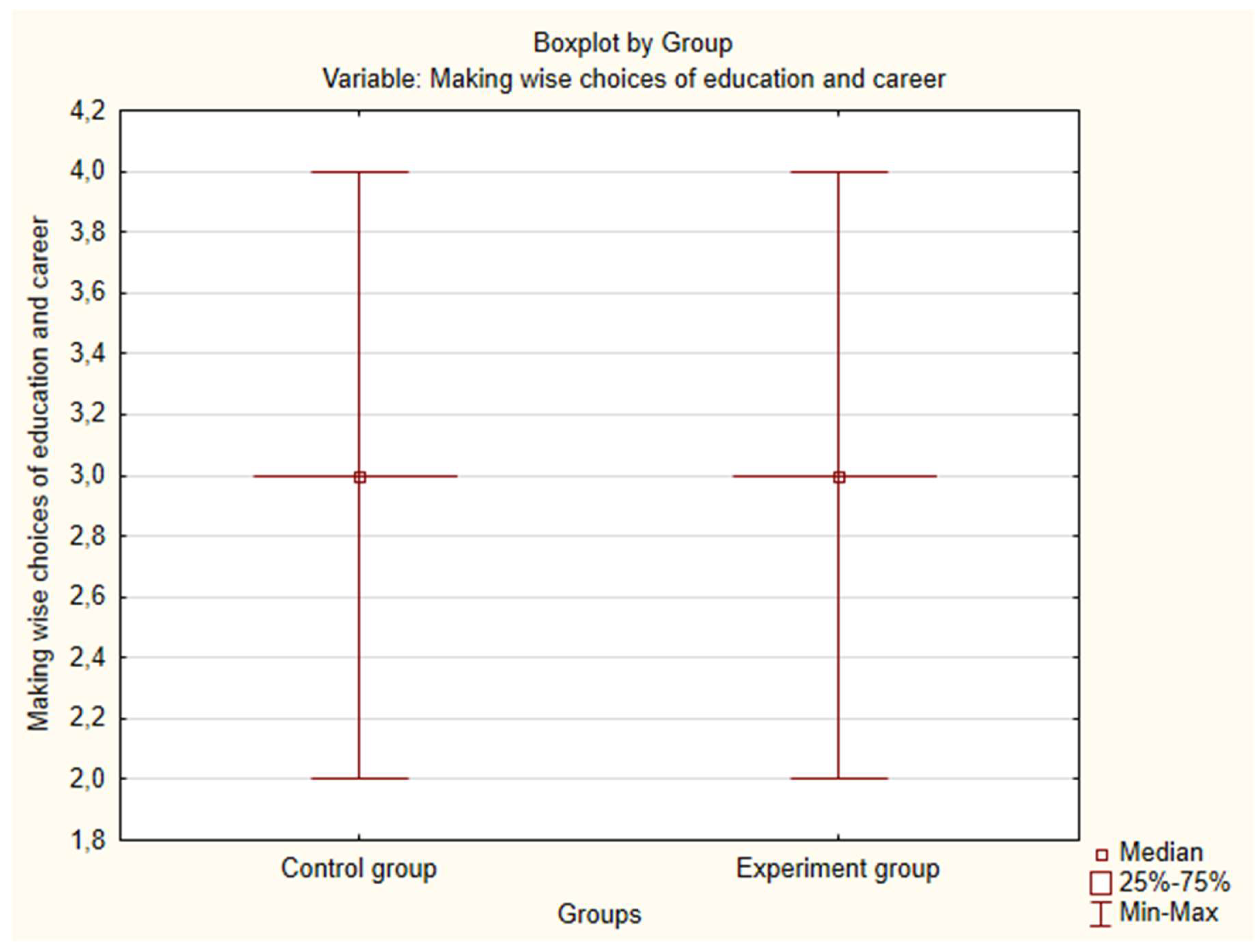

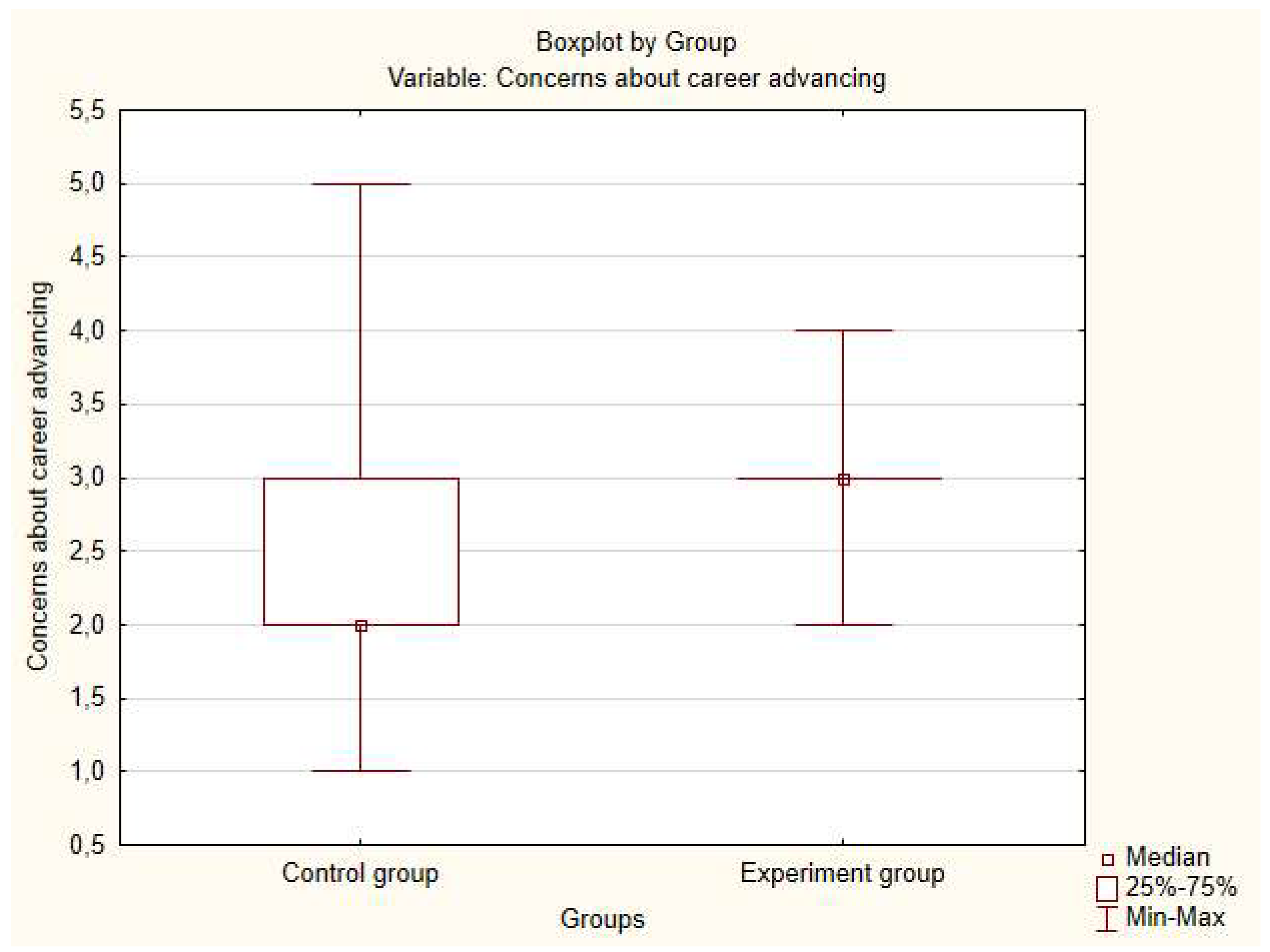

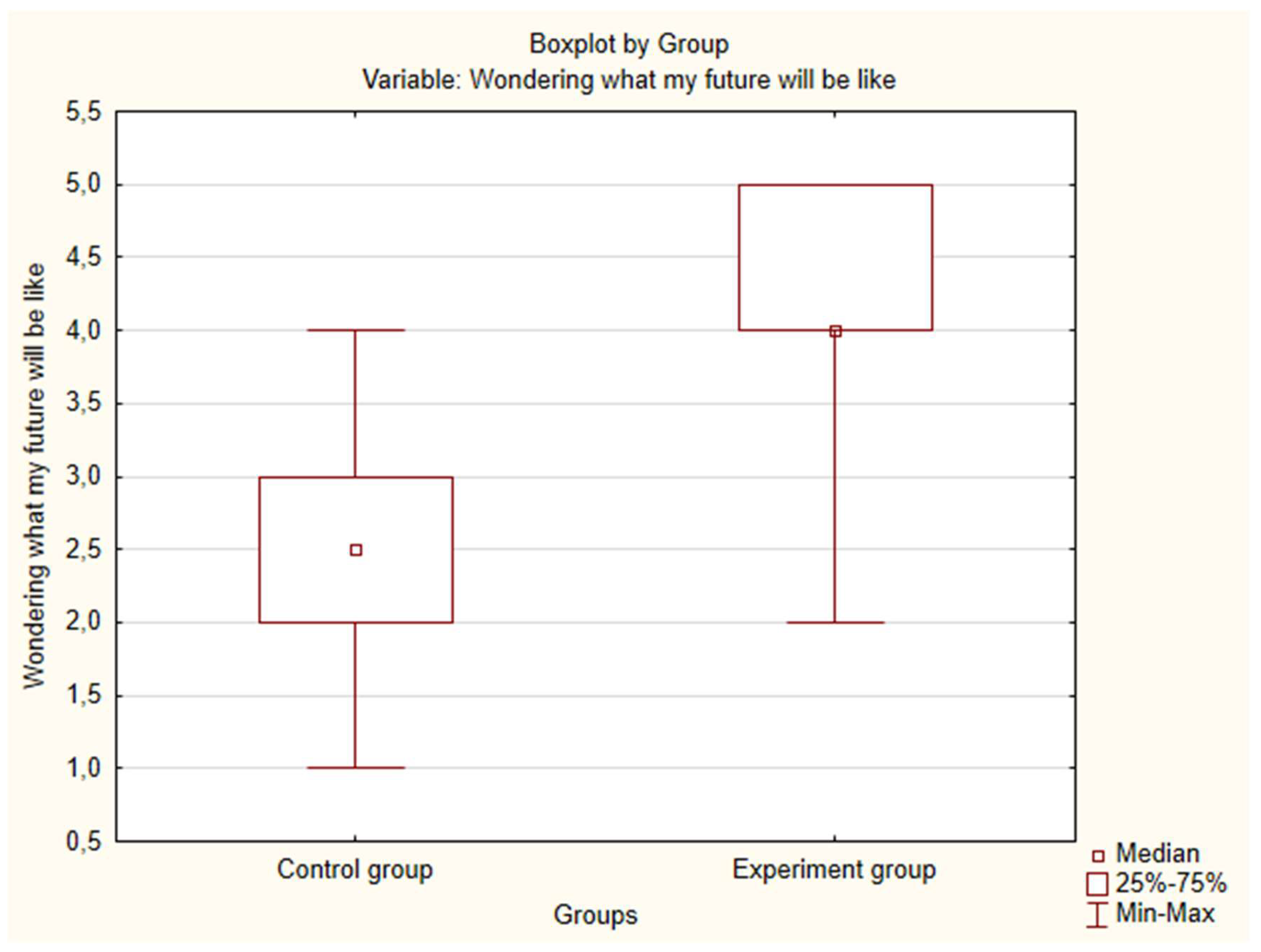

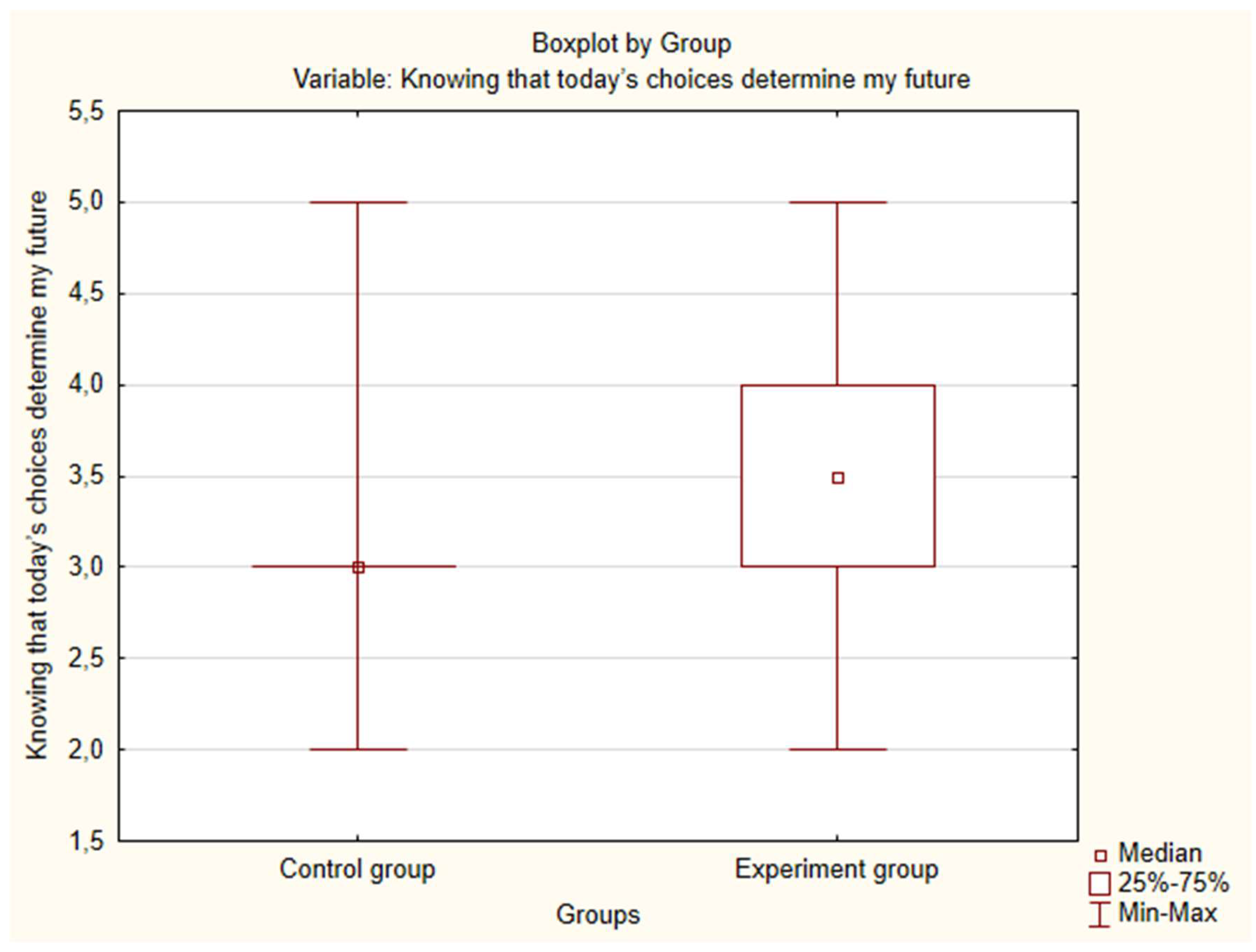

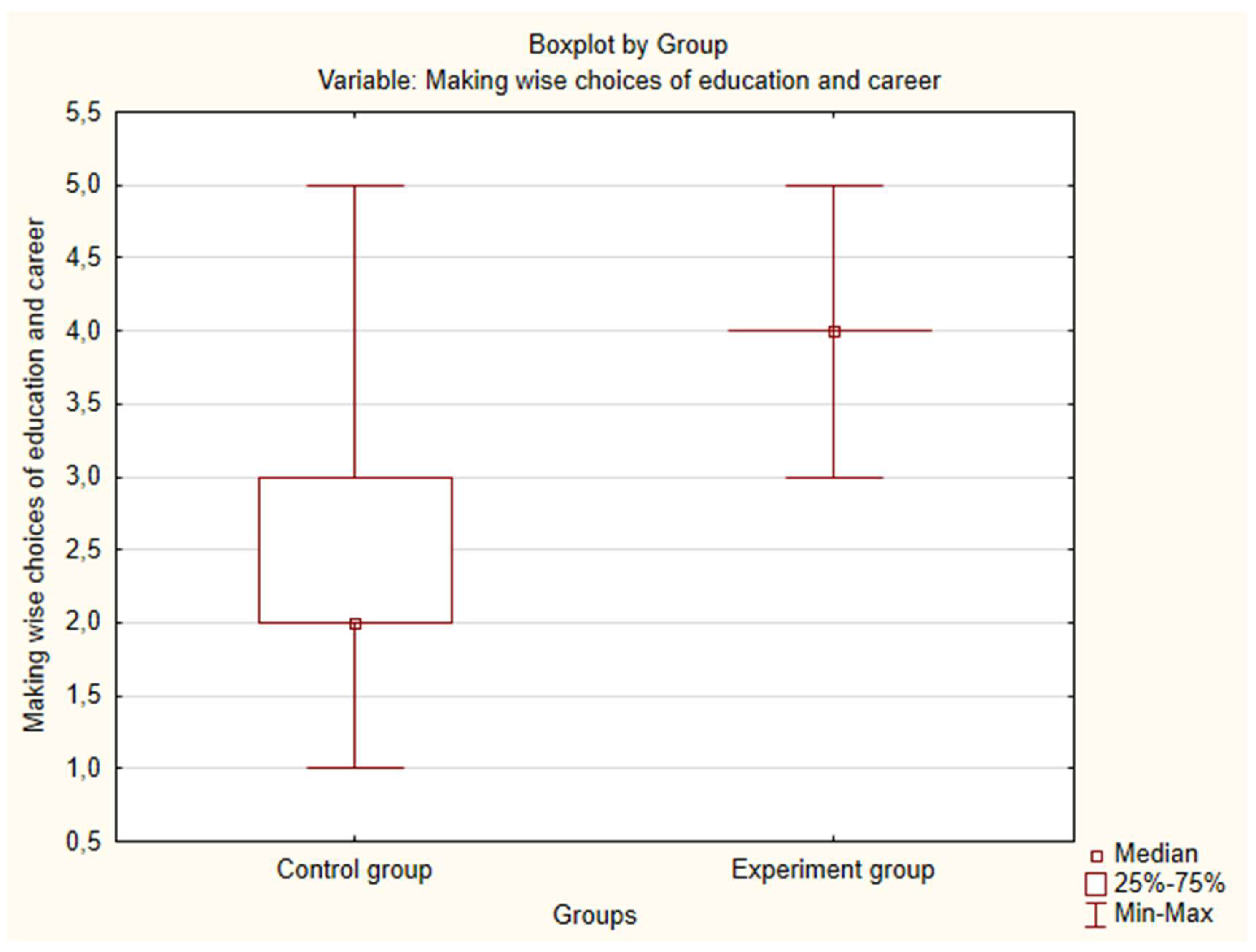

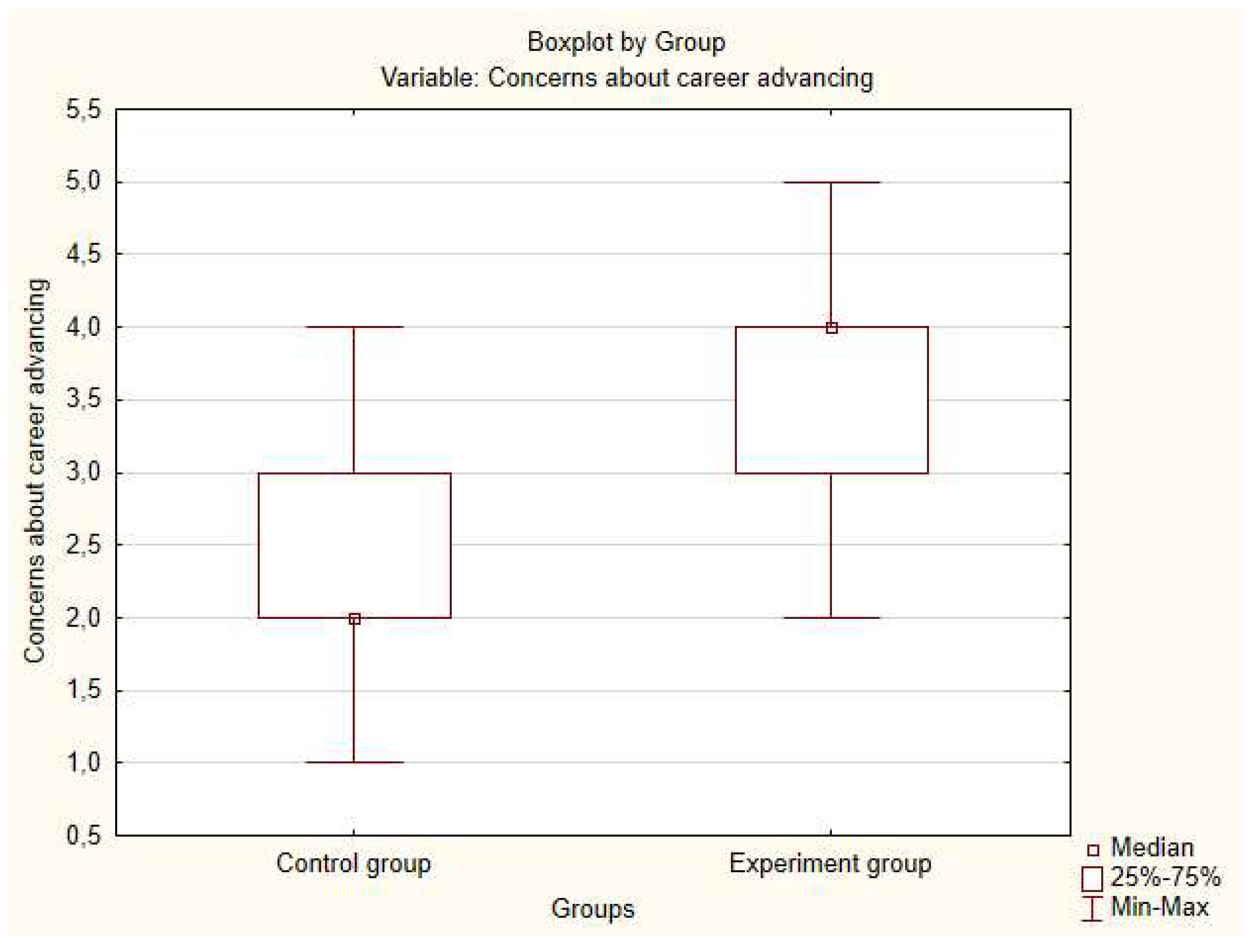

The experiments showed that after training values of the attributes “Wondering what my future will be like”, “Making wise choices of education and career” statistically significantly decreased with P being less than 0.05. The values of the attributes “Knowing that today’s choices determine my future”, “Concerns about career advancing” increased. The remaining data were unchanged with P>0.05 (

Table 9).

*The percentage differences between the mean values are shown in yellow.

** Statistically significant differences are highlighted in red.

After the end of the experiment, the majority of students in the experimental group noted a statistically significant improvement in values of all attributes by 33.3 – 50%. At the beginning of the experiment the attributes were basically the same in the experimental and control groups (P>0.05), apart from the value of the attribute “Concerns about career advancing” that was higher in the experimental group.

In the control group having been taught under standard curriculum the median of “Wondering what my future will be like” decreased statistically by 16.7% (P<0.001).

In the control group, the median of the attribute “Knowing that today's choices determine my future” increased statistically significantly by 20.0% (P<0.001) after the standard training.

In the control group after standard training, the median of the attribute “Making wise choices of education and career” decreased statistically by 33.3% (P<0.001). The mean of “Concerns about career advancing” was statistically significant at 17.4% (P<0.001) after undergoing the standard training.

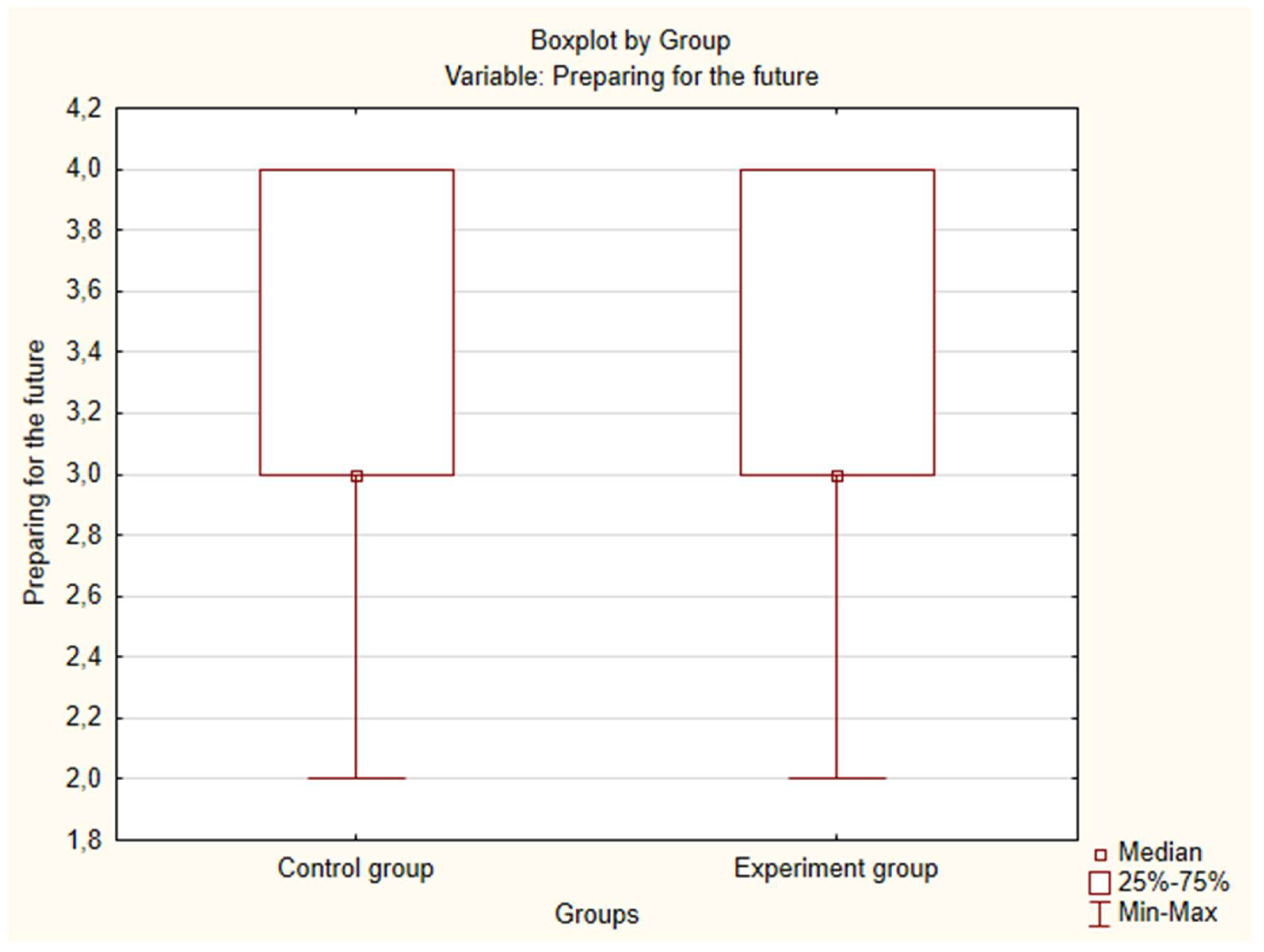

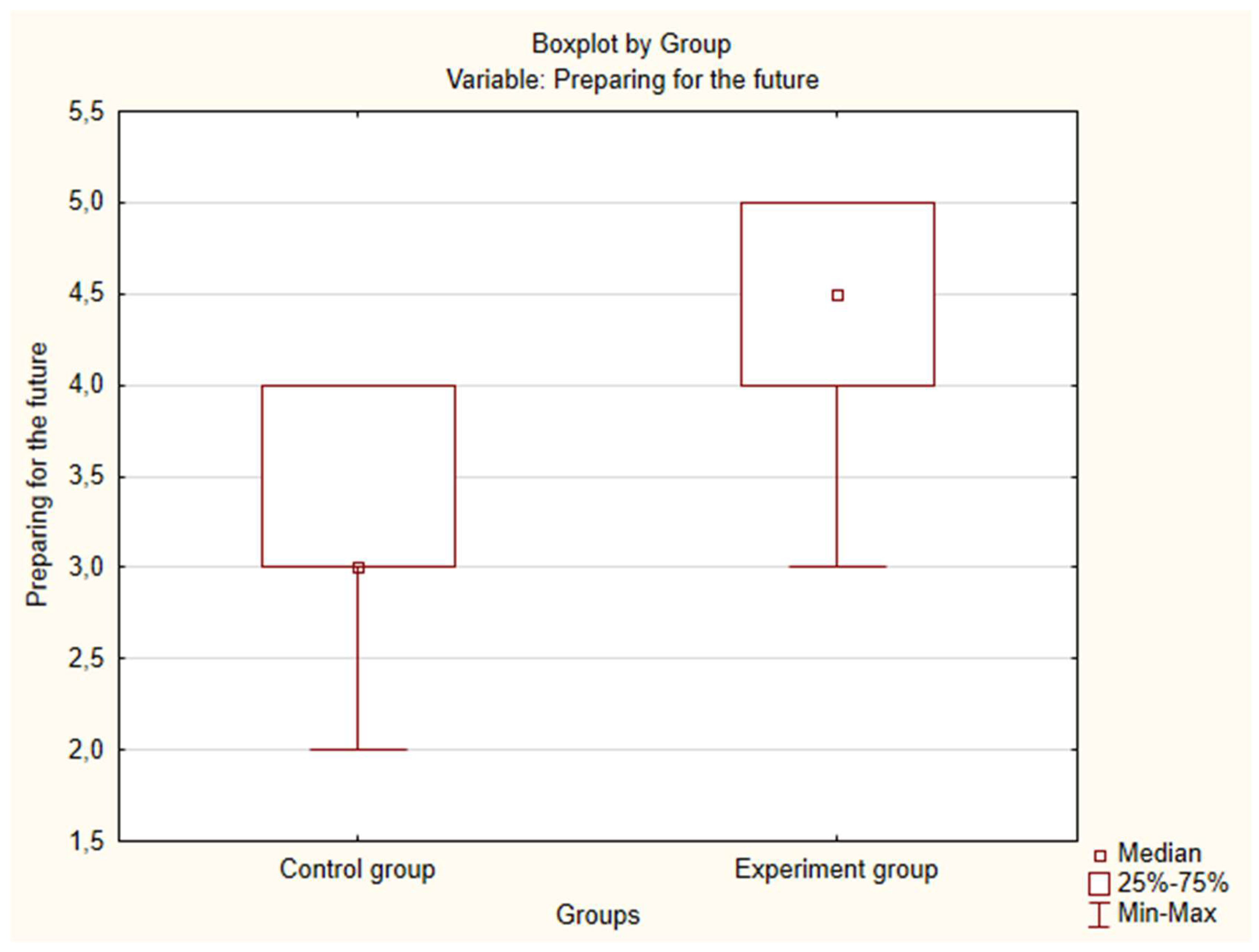

The experimental group demonstrated the increase by 33.3% of the median of the attribute “Wondering what my future will be like” (P<0.001). In the experimental group, at the end of the experiment the median of “Knowing that today’s choices determine my future” increased by 40.0% statistically (P=0.003). Whereas the median “Preparing for the future” increased statistically by 50.0% (P<0.001). At the end of the research the experimental group showed the increase by 33.3% of the median of “Making wise choices of education and career” (P<0.001).

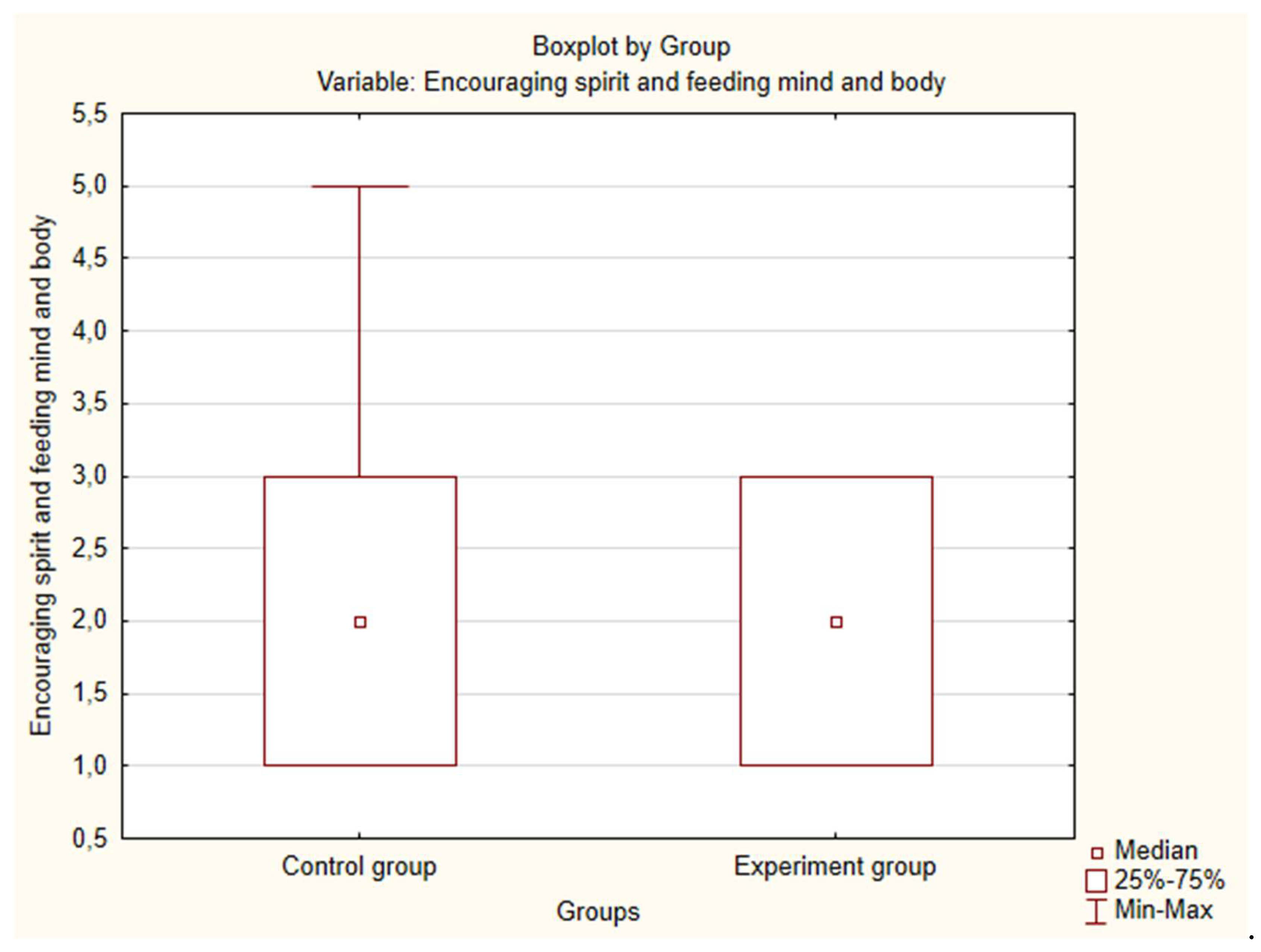

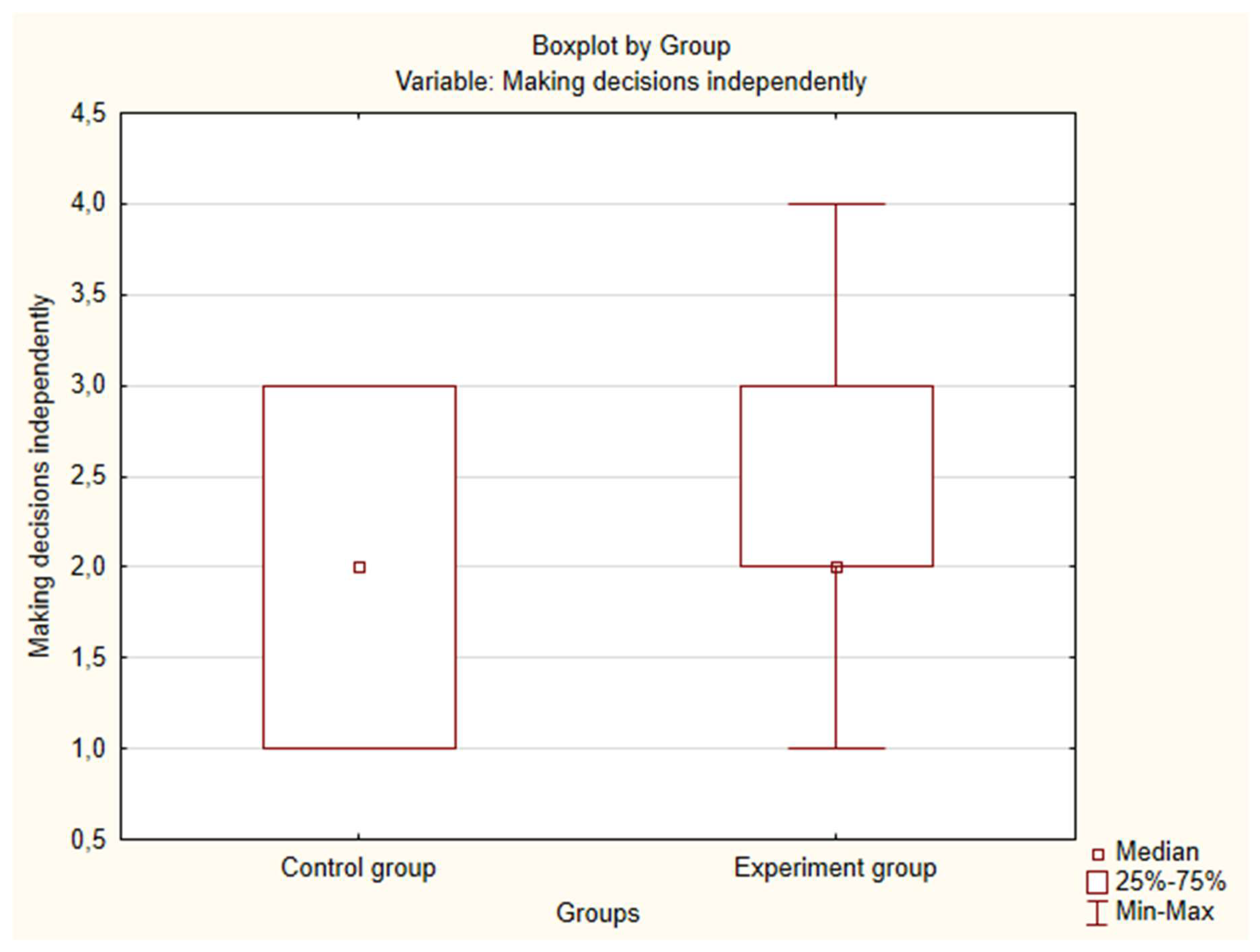

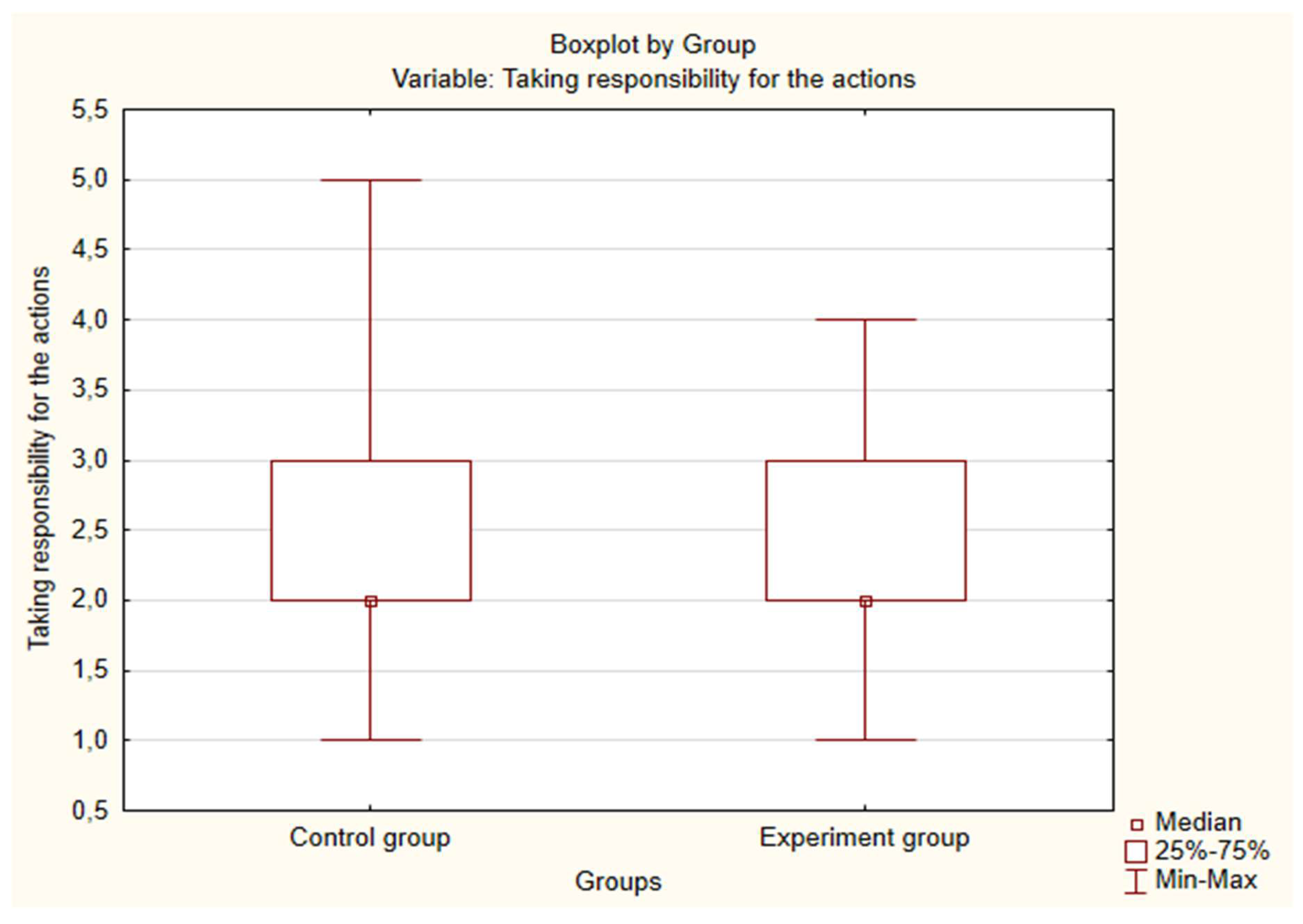

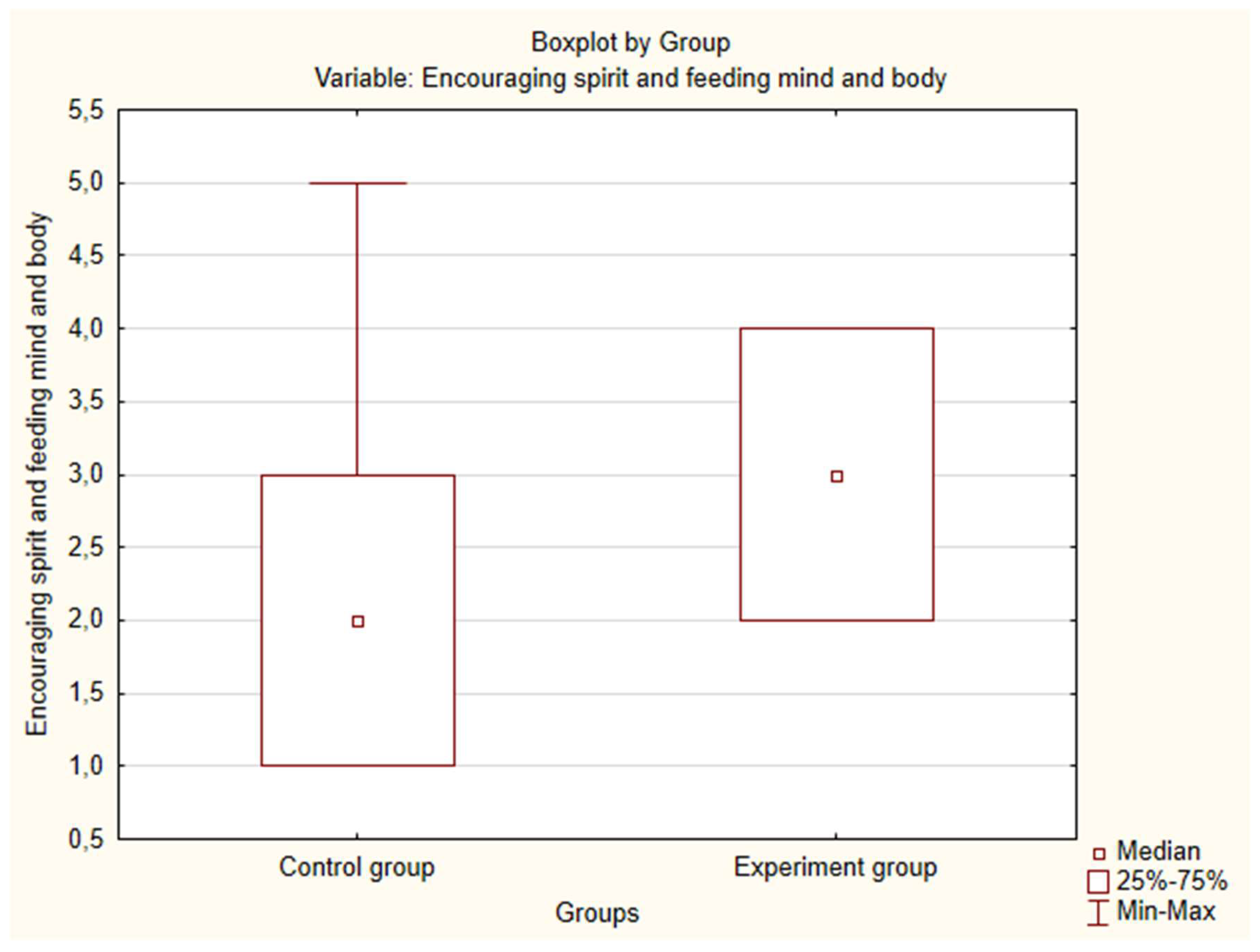

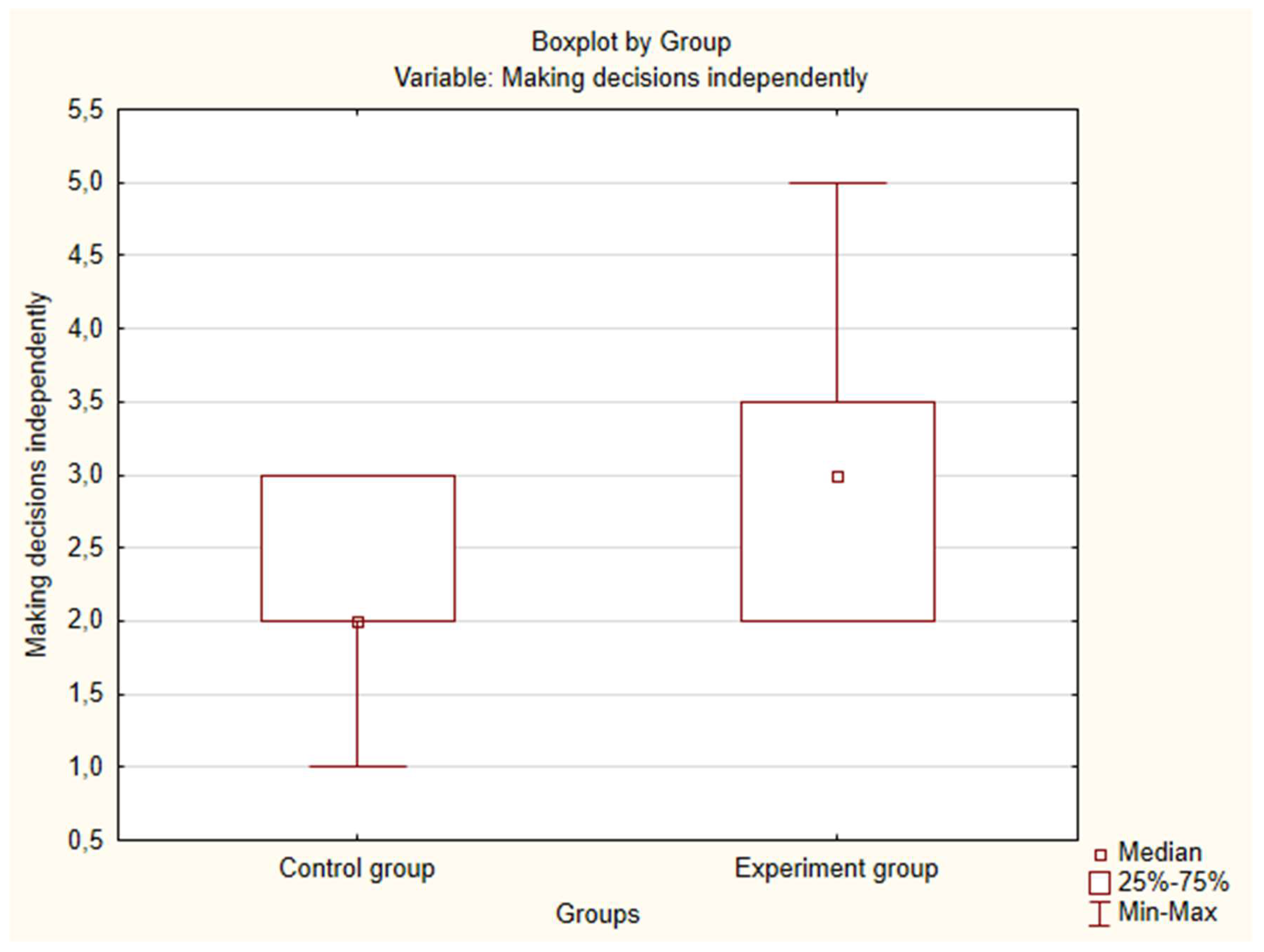

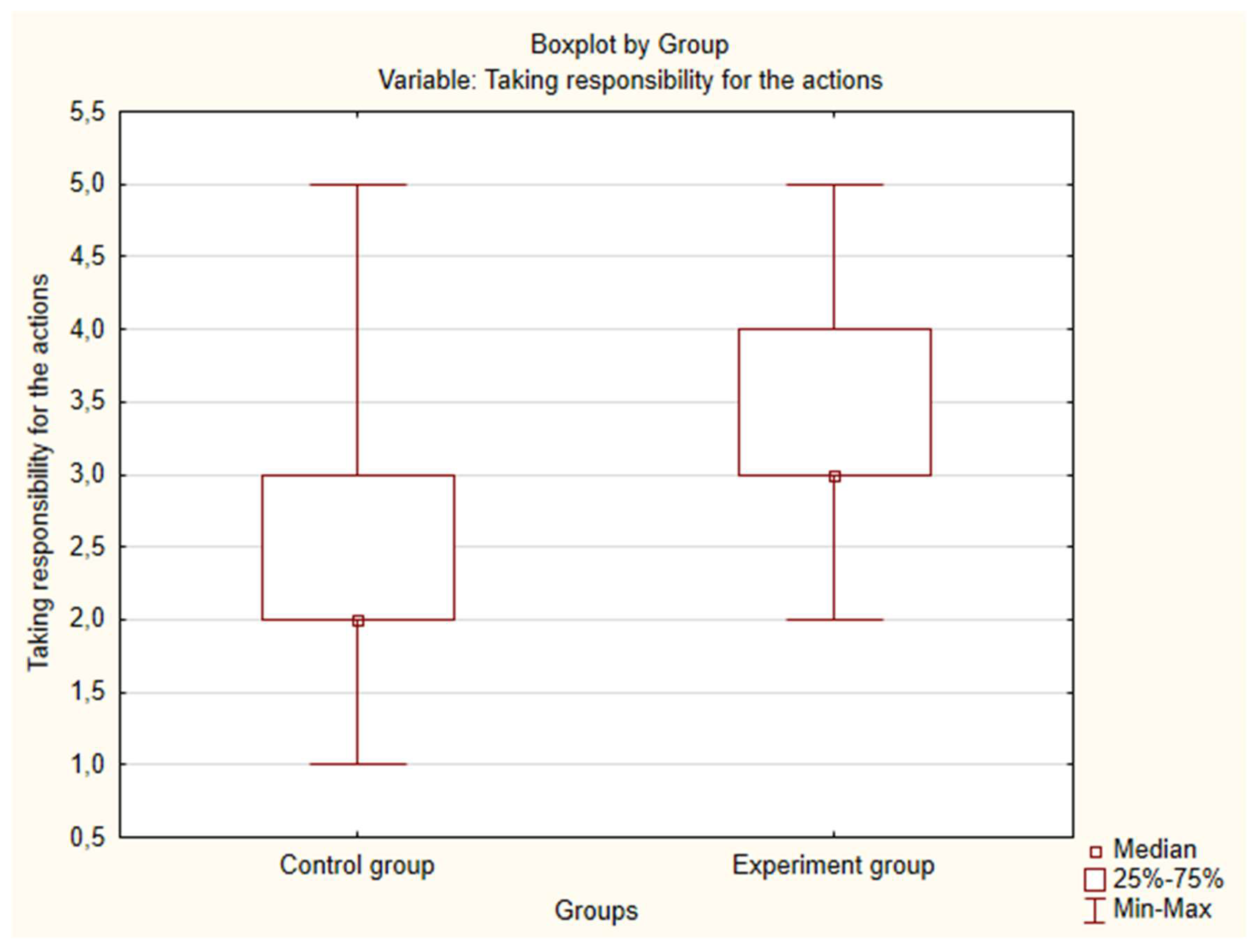

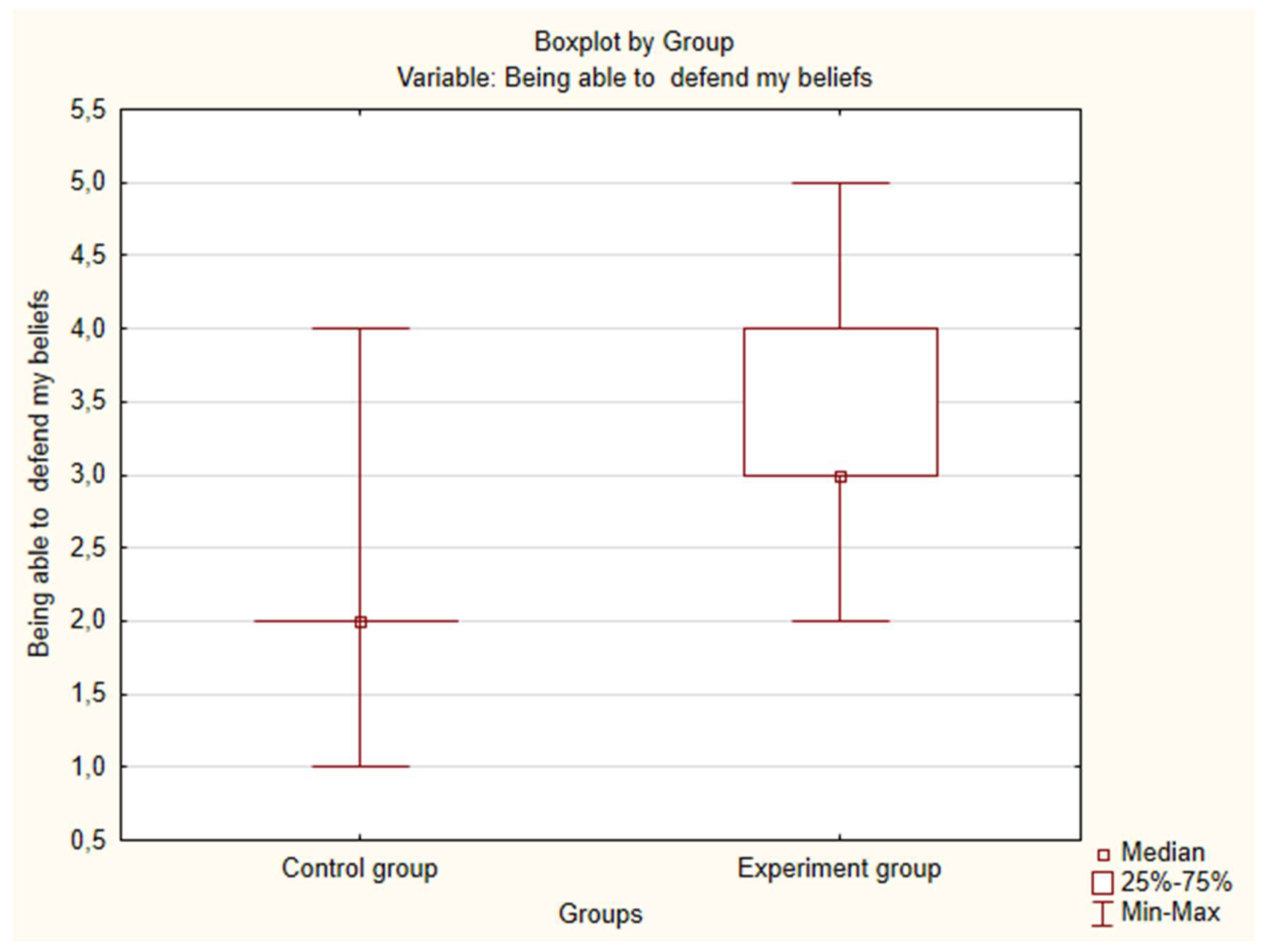

At the end of the research the control group demonstrated increase by 2.5 - 26.1% of all attributes (P<0.05) except “Encouraging spirit and feeding mind and body”. After training the experimental group showed an increase of all attributes by 50% (P<0.05). Before the training there were no differences between the groups (P>0.05). After training, all indicators became higher in the experimental group by 50% (

Table 10).

*The percentage differences between the mean values are shown in yellow.

** Statistically significant differences are highlighted in red.

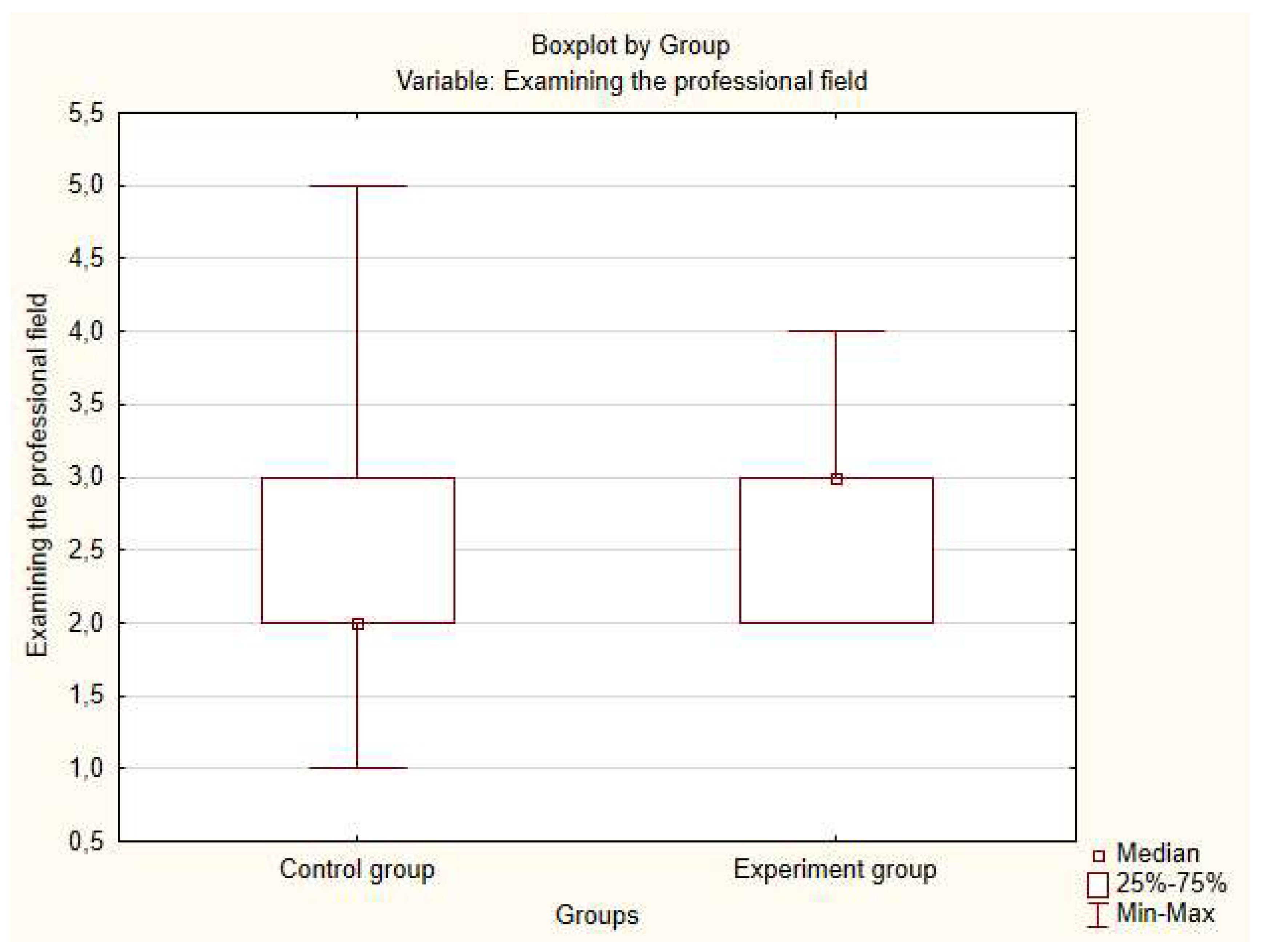

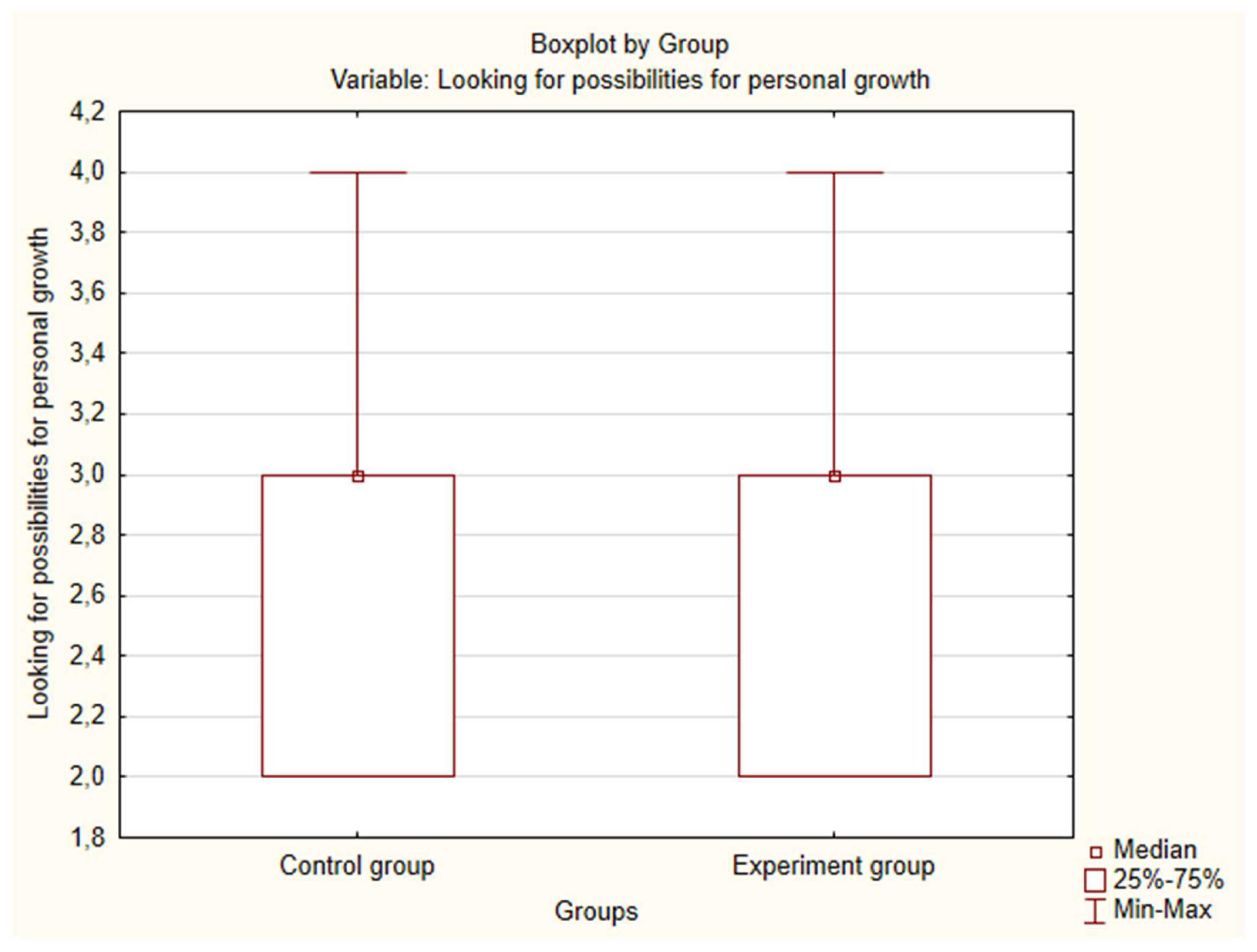

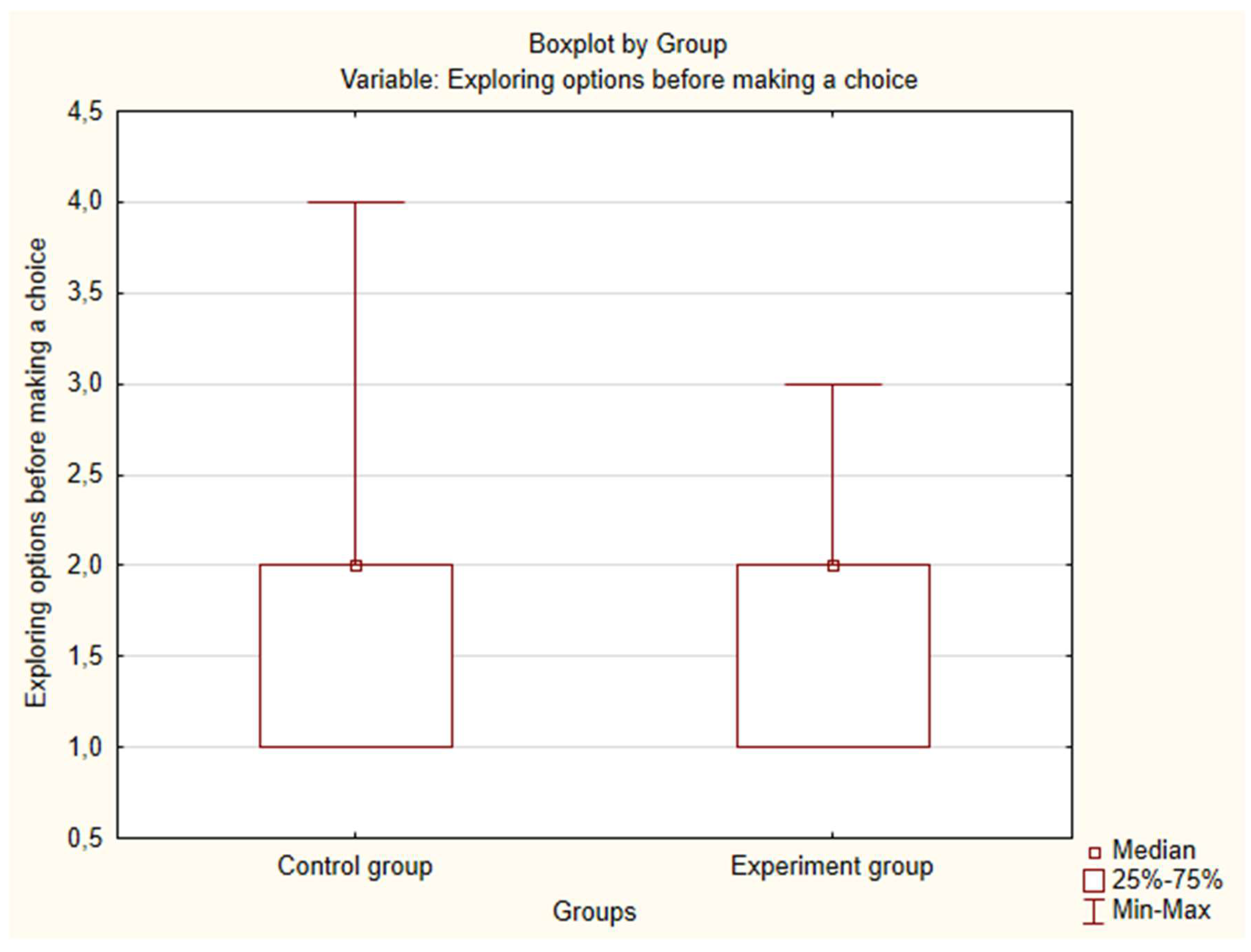

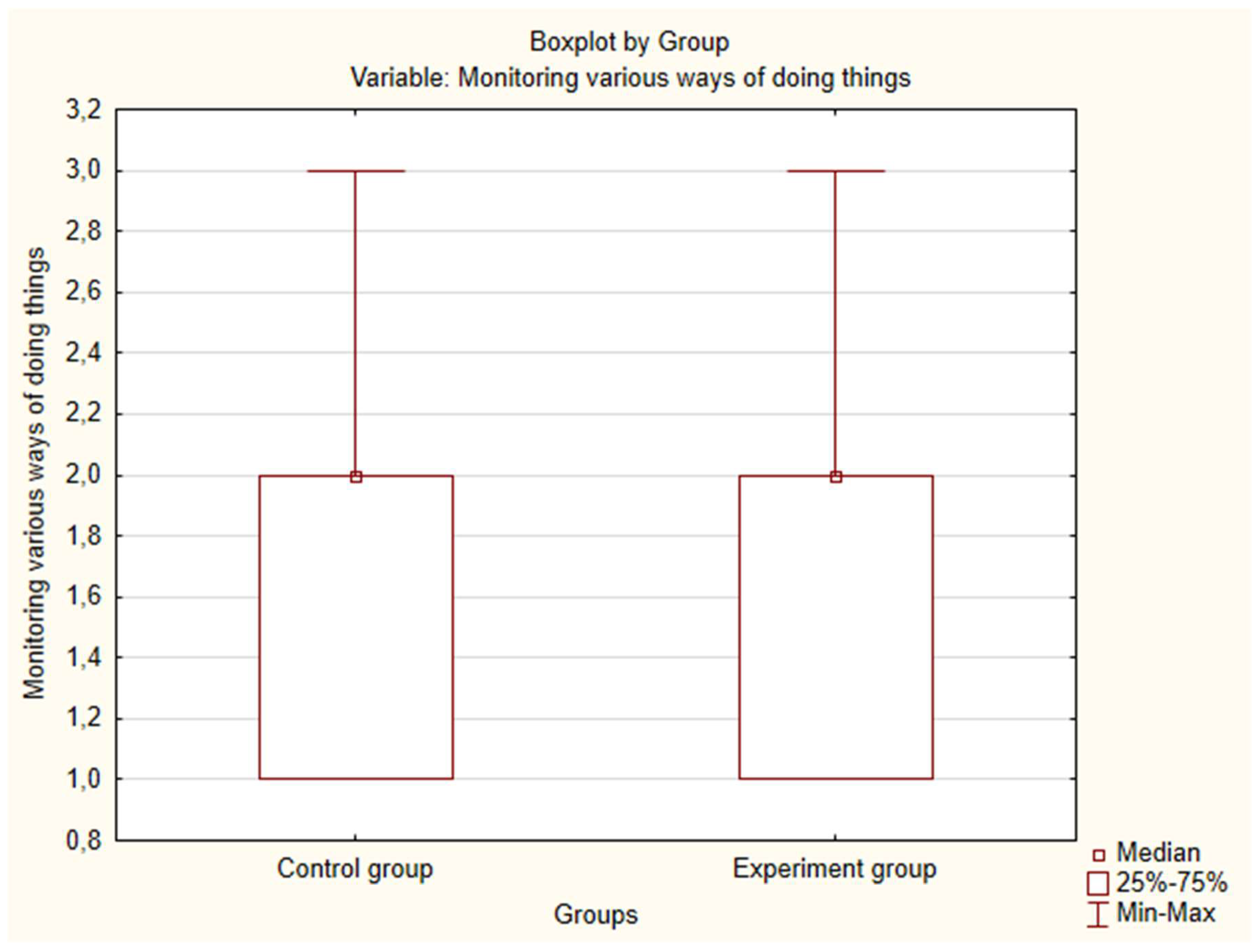

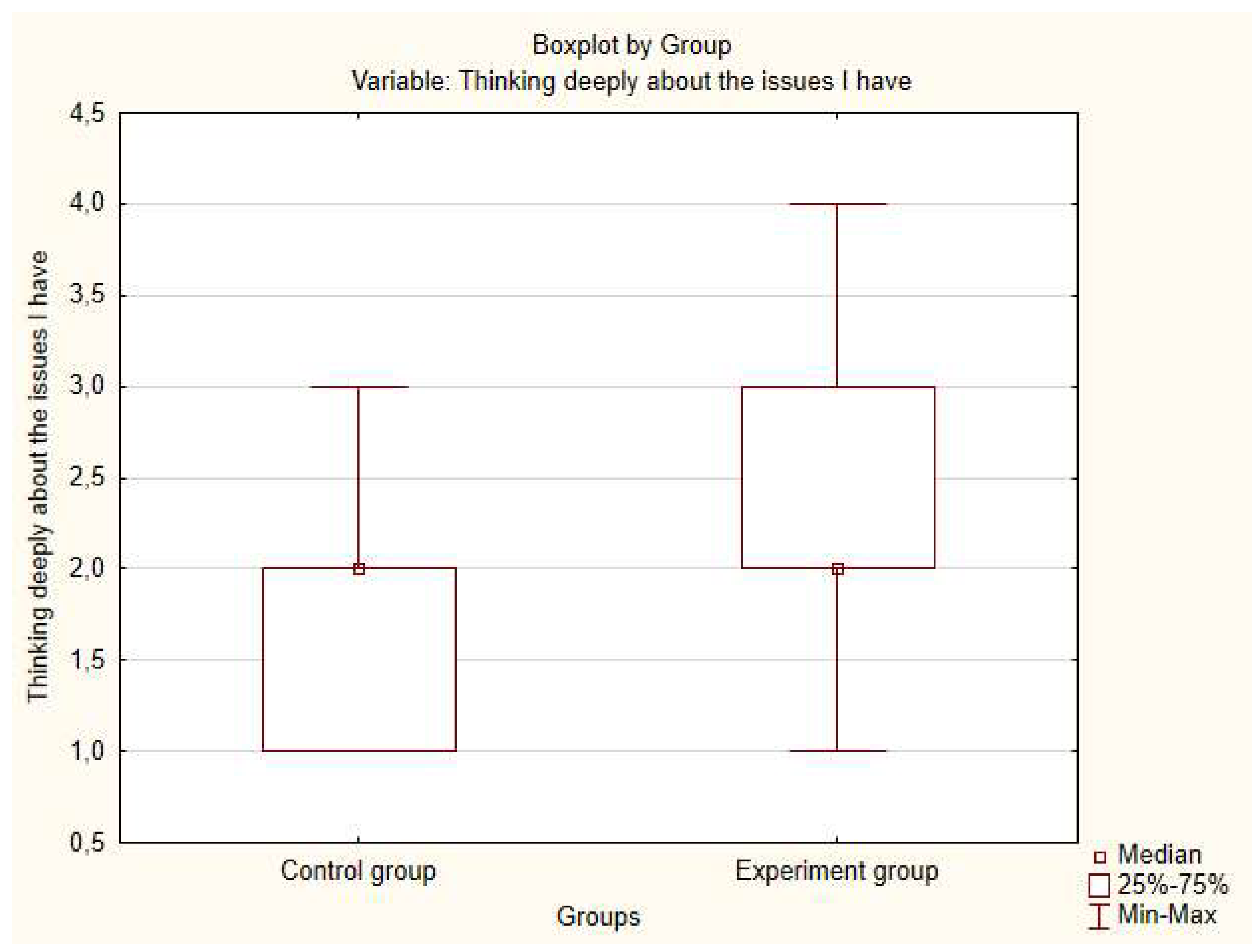

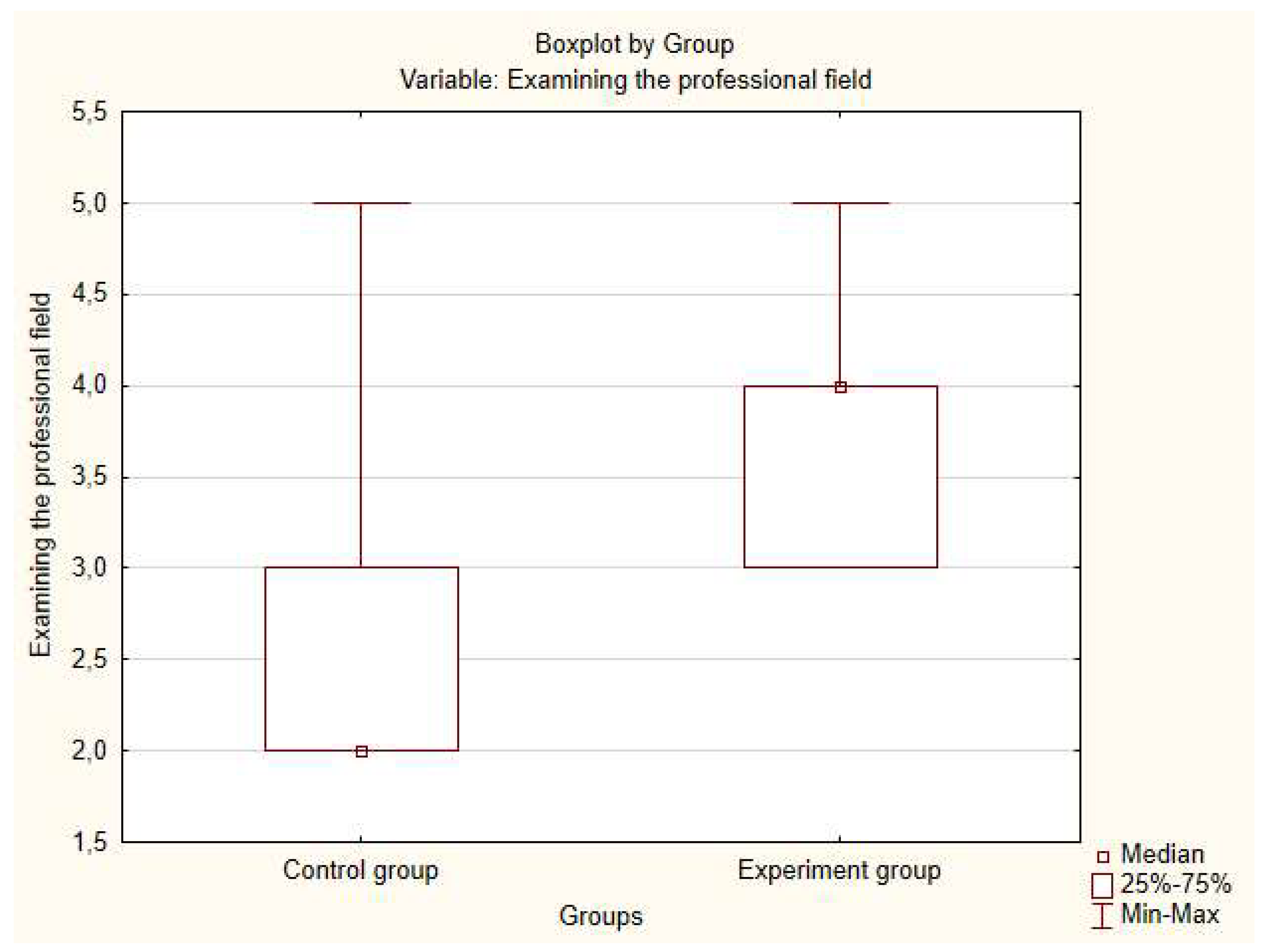

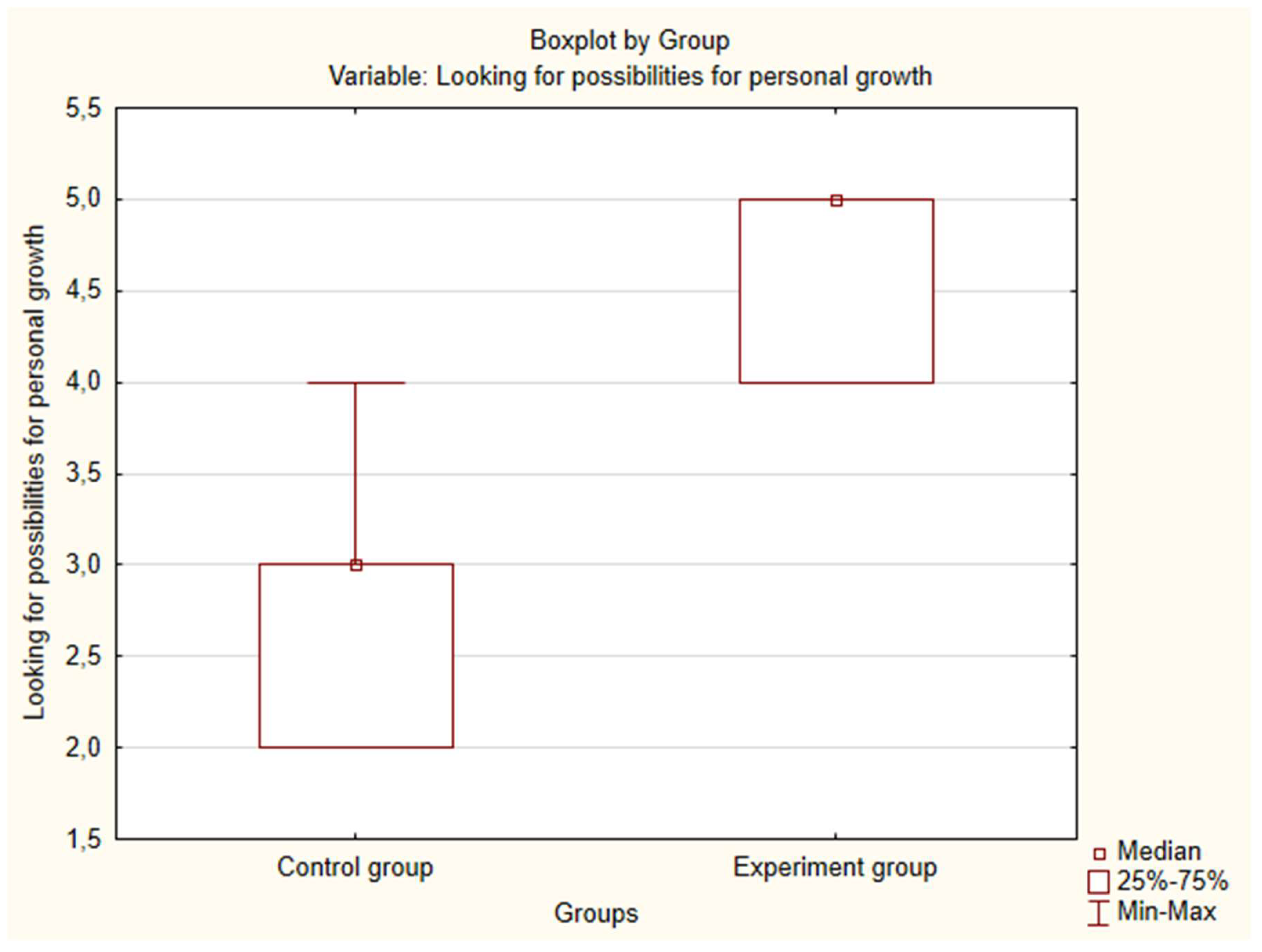

After training the control group’s attribute “Looking for possibilities for personal growth” increased statistically significantly by 6.7 - 34.4% (P<0.05). After ESP course studies all attributes of the experimental group improved statistically significantly by 33.3 - 100% (P<0.05). Before training, there were no differences between the groups (P>0.05) except for the attribute “Examining the professional field” as well as “Thinking deeply about the issues I have”. After ESP training, all attributes improved by 66.7 - 100% in the experimental group (

Table 11).

*The percentage differences between the mean values are shown in yellow.

** Statistically significant differences are highlighted in red.

As it can be seen from taable 12 the values of all attributes increased statistically significantly by 11.9 - 150% (P<0.05). After training in the experimental group, all values increased by 33.3 - 200% (P<0.05). Before training, there were no group differences indicated (P>0.05) except for the attributes “

Finding the most efficient way of performing tasks” and “

Overcoming obstacles”. After the ESP course studying, all values of the attributes except “

Being responsible for the choice” became higher in the experimental group by 33.3 - 150% (

Table 12).

*The percentage differences between the mean values are shown in yellow.

** Statistically significant differences are highlighted in red.

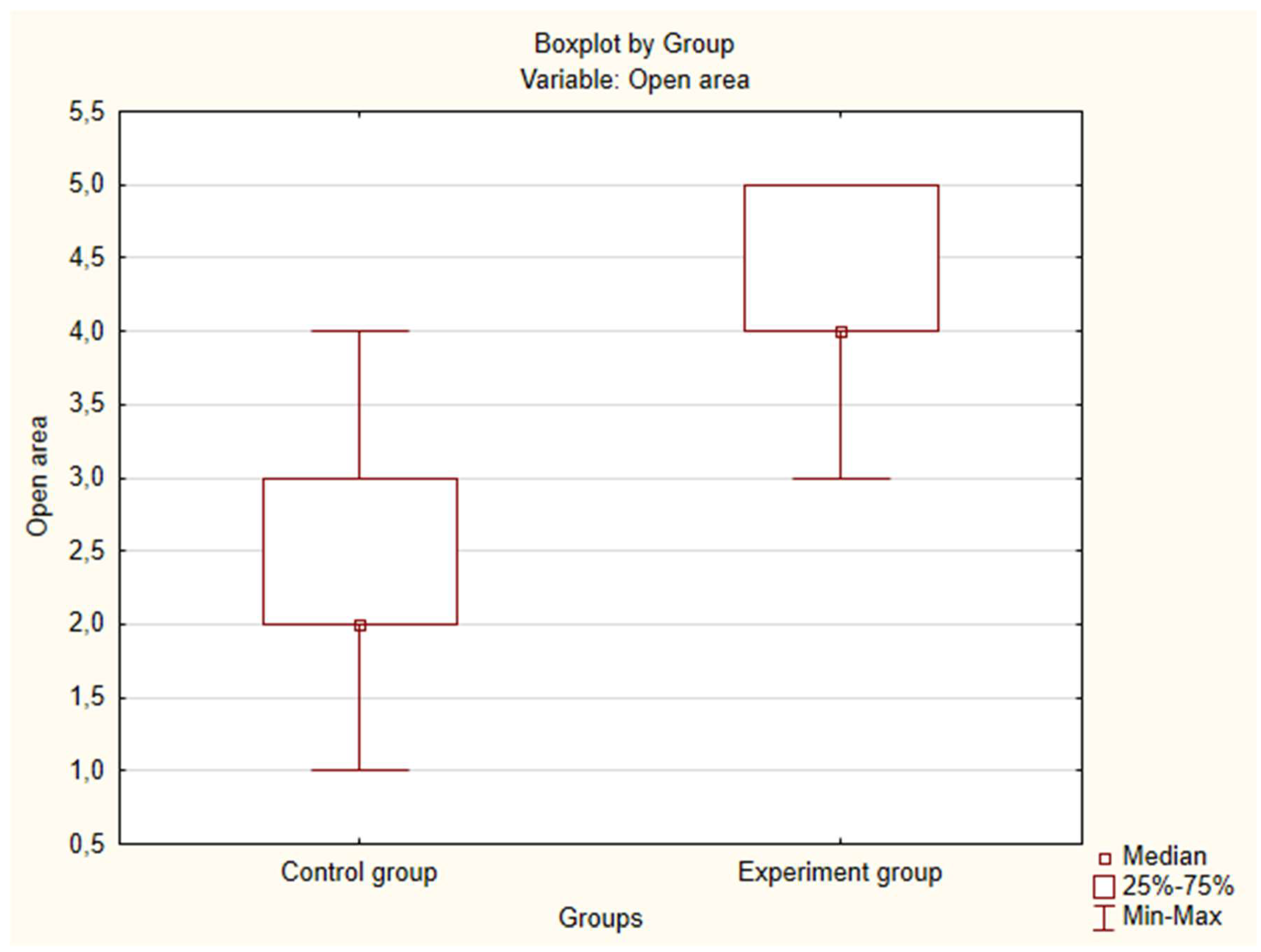

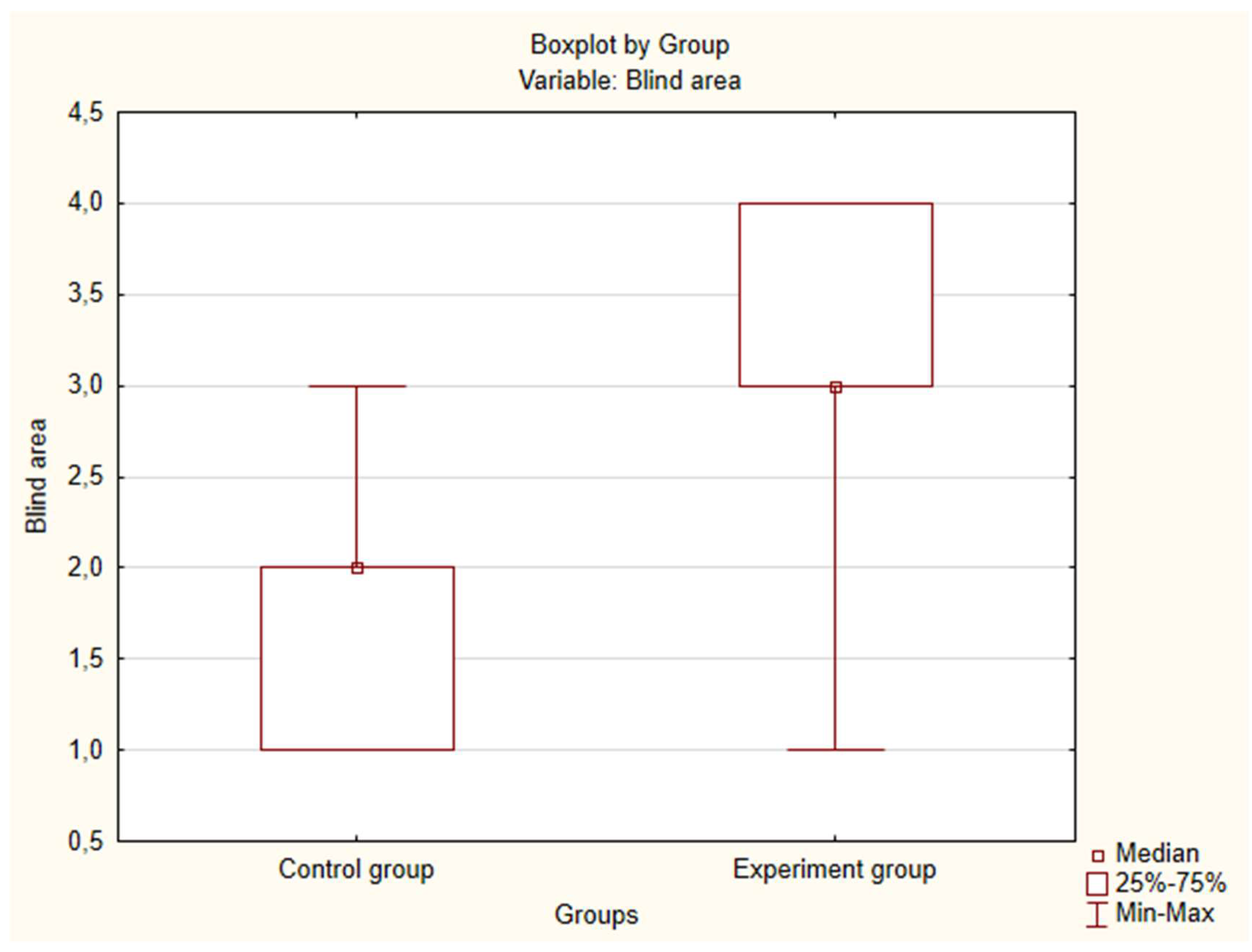

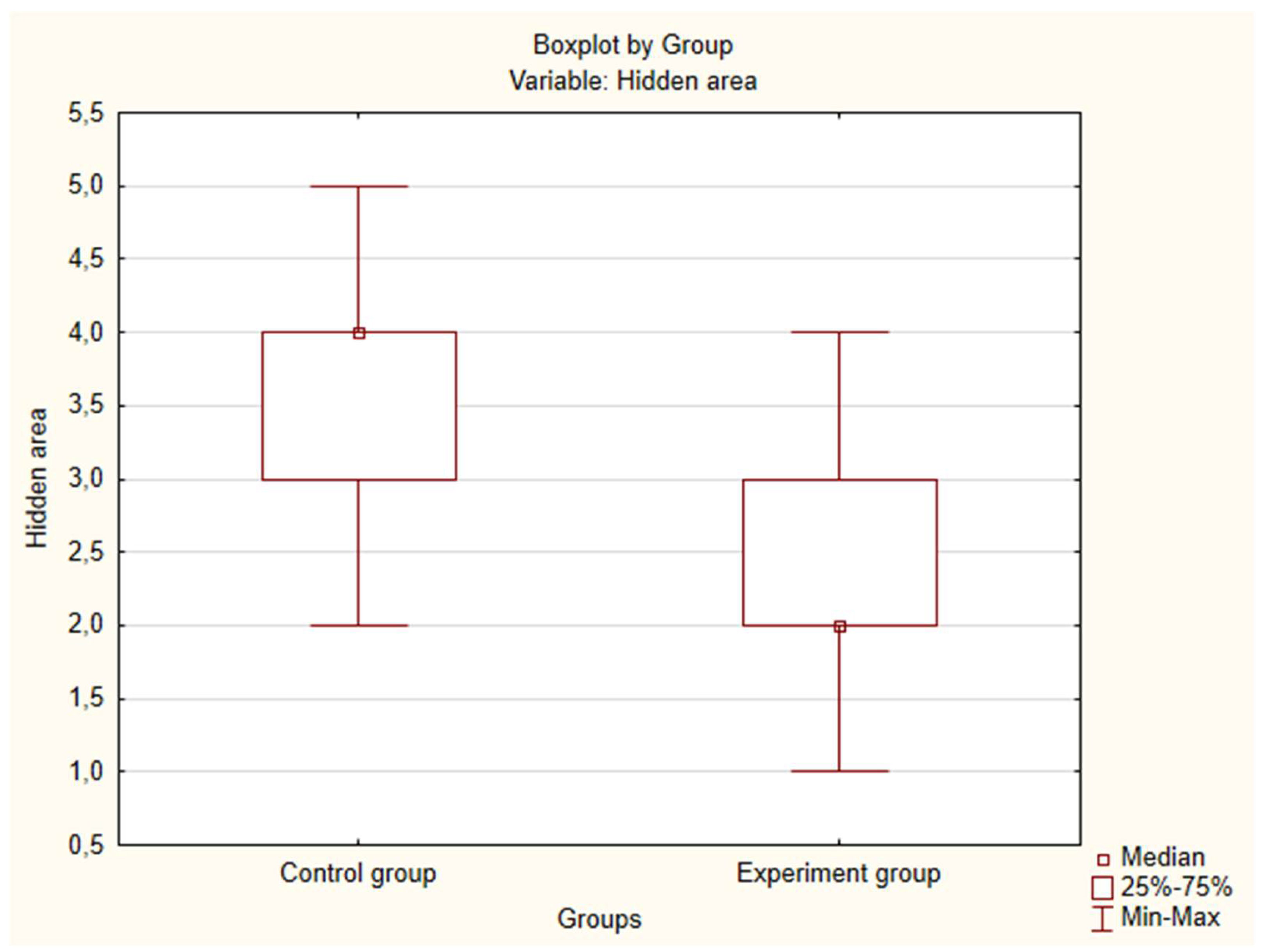

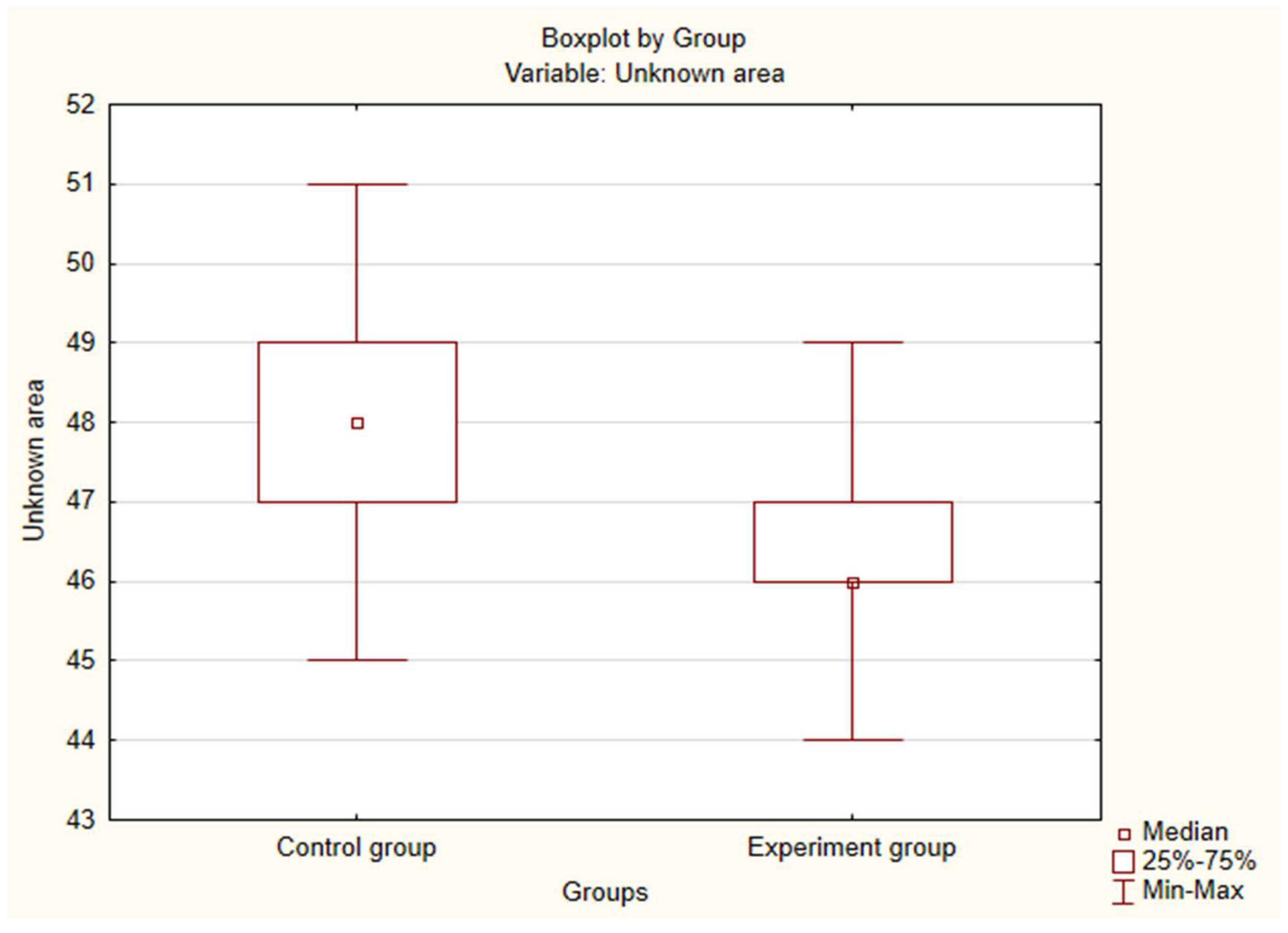

The Johari Windows test administered after the experimental ESP course showed that the differences between how students see themselves and each other in terms of students' attitudes, beliefs, skills and experiences towards others decreased.

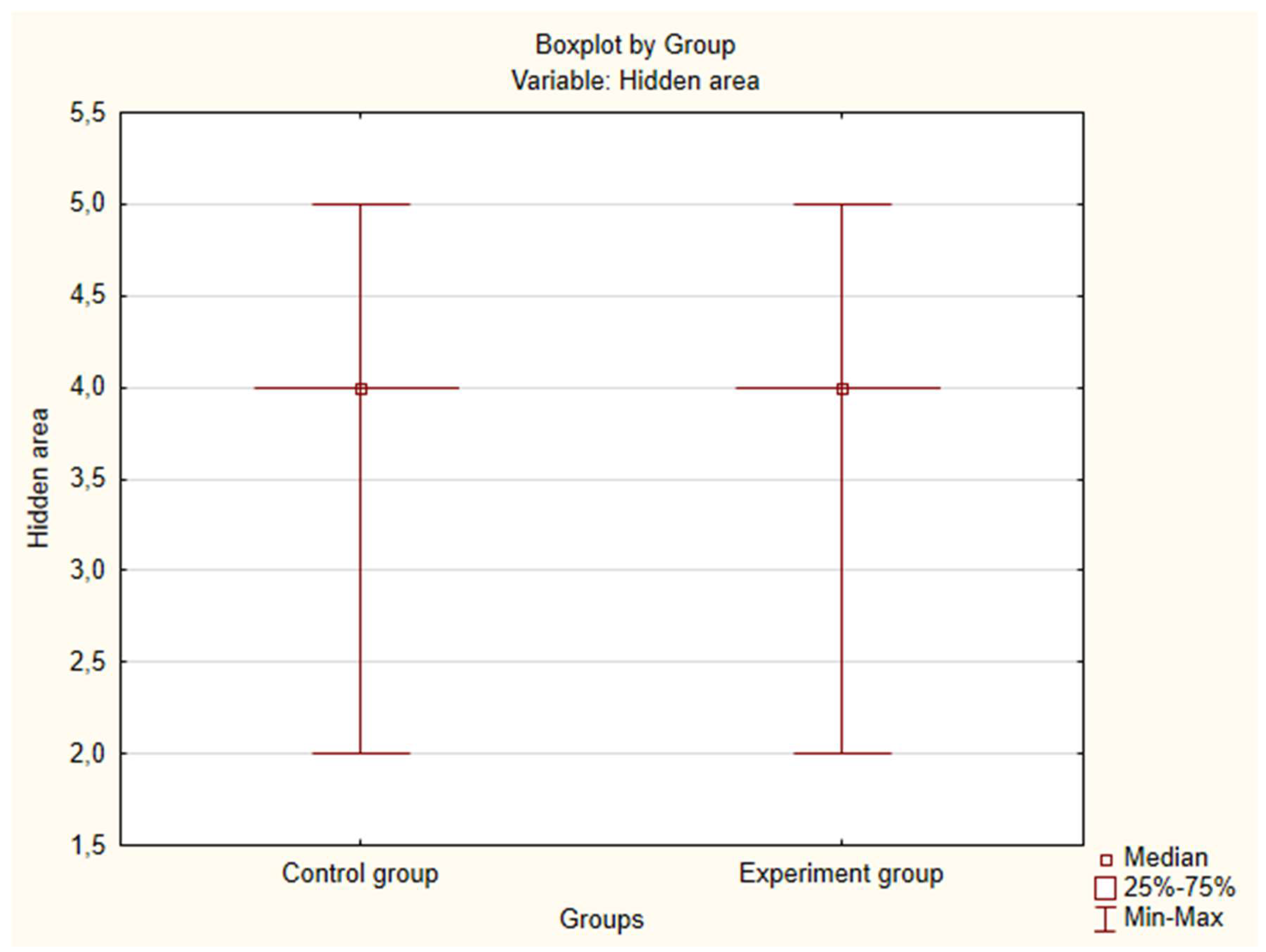

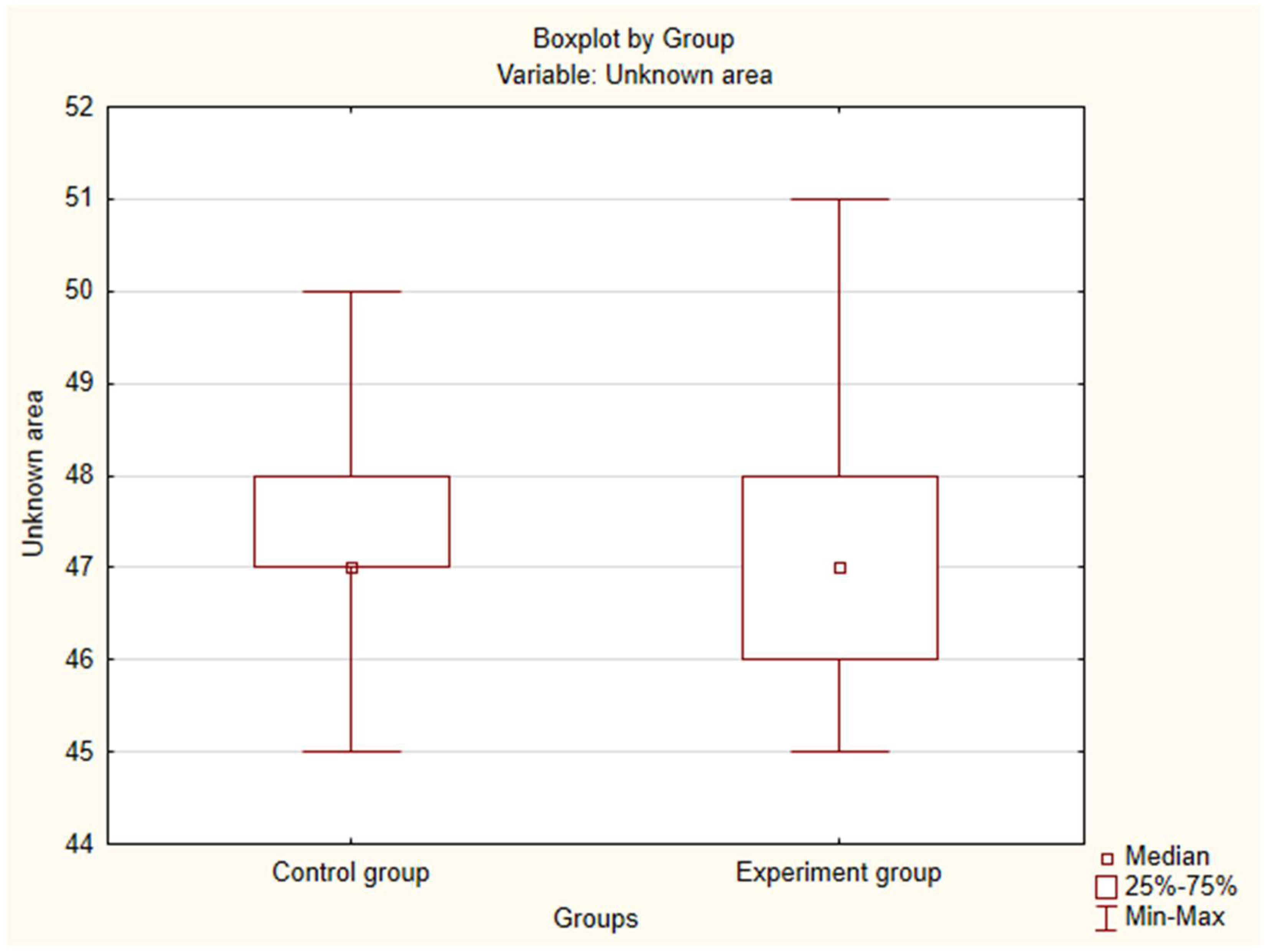

Thus, the open/free area (Arena) expanded, the blind area shrank, the unknown area (Unconscious) became more observable, the hidden area (Facade) revealed. The interpretation of adjectives in the Johari Window quadrants showed that internal and external self-awareness of the experimental group has increased. Thus, interpersonal communication has been improved in the experimental group.

After training the control group’s indices, for example, quadrants “Arena” and “Façade/Hidden area” decreased by 33.3 and 3.6% (P<0.05). The Unknown area increased by 2.1%. The Blind spot did not change (P>0.05). After ESP training the experimental group demonstrated an increase of the Arena and Blind spot by 33.3 and 50.0% (P<0.05). Façade and Unknown area decreased statistically significantly by 50.0 and 2.1% (P<0.05). Before training, there were no differences between groups concerning quadrants Arena and Façade (P>0.05). Blind spot was higher by 12.6% in the experimental group (P<0.05). There was a decrease by 0.5% in the Unknown area. In the experimental group the Arena, Blind spot widened by 100 and 50% in the experimental group. After training, the Façade, Unknown area became lower in the experimental group by 50 and 4.2% (

Table 13).

*The percentage differences between the mean values are shown in yellow.

** Statistically significant differences are highlighted in red.

Interpretation of adjectives in Johari quadrants showed that the performance of the experimental group improved. Thus, students in the experimental group improved their interpersonal communication skills.

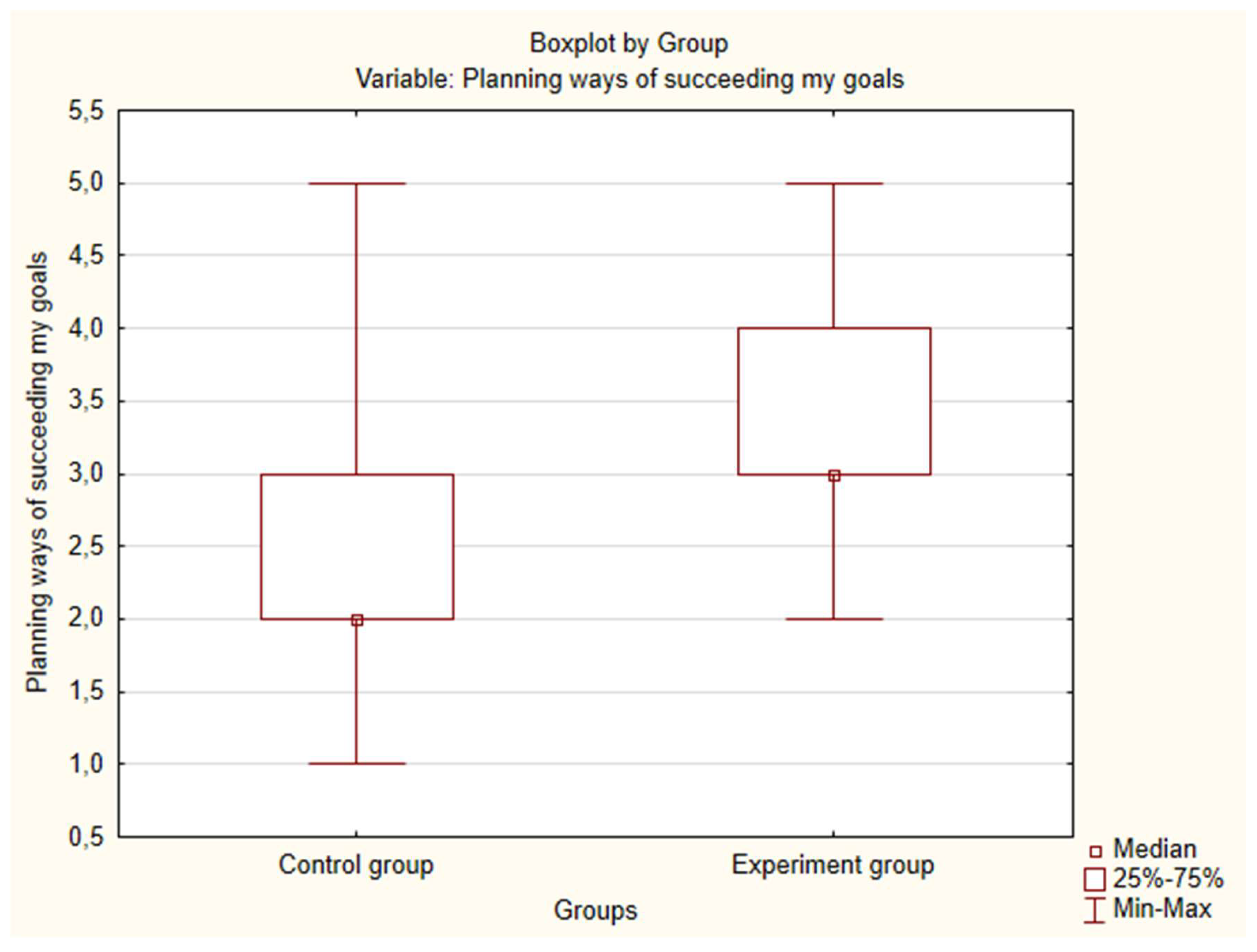

Appendices A-D contain diagrams illustrating the changes in the flexible skills of engineering students of the control and experimental grpoups before and after the experiment.

4. Discussion

The aim of the study was to find a way to develop English language skills and employability skills of engineering students within English classes engineering students within English classes. The key practical outcomes of this research are the ESP course design and both development of employability (personal and social) skills of engineering students. We achieved the study aims through the design of the ESP course.

This discussion centres around two main topics: development of foreign language competence of students and their soft skills, being part of the employability skills. Our findings within the employability skills development have broadened the results of some other researchers in this field [

39,

40]. However, their level of communicative competence is not as high as the one discovered in a previous study on L2 students’ and L2 [

41,

42]. This difference can be explainedby the fact that students in engineering education typically have an inherently lower level of the English command comparing with humnitarian students. The level of English proficiency can be increased based on the ESP course. This finding is not surprising inthe light of previous research results [

43,

44].

We have classified skills into four different categories. By revealing a connection between career adapt abilities factors and soft skills, our study offers compelling insight into the nature of employability skills.

Our results are consistent with previously published data [

45,

46,

47]. Fundamental academic competencies were divided into cognitive abilities such as reasoning, problem solving, creativity, decision-making skills; abilities in conflict resolution, leadership, and negotiation (interpersonal and teamwork); personal traits and mindsets - confidence, and readiness for personal development. However, in our present research the role of an ESP course was emphasized.

We agree with the findings of [

48,

49,

50] who suggest that students should be given an opportunity to develop complement skills associated with employability classifying as personal ethics and social awareness; intellectual abilities to think critically, analitical skills; and performance – the application of skills and intellect in the workplace and engagement – the willingness to meet personal, employment and social challenges. We enhanced the results gained by Mallough S. (2001), Mazalin K. (2015), Ramisetty J. (2017) and employed two methods to evaluate employability skills development.

The authors of this paper align with scientists who believe employability skills like soft skills are as vital as technical skills (Fugate et al., 2004; Mazalin et al., 2015; Jantassova et al.,2024 ).

5. Conclusions

There is a critical need to create the pedagogical conditions that develop employability skills of engineering students who are to possess technical and interdisciplinary knowledge and have highly developed soft skills..

This experimental ESP learning performed at Saint Petersburg Mining University under the curriculum of the second-year specialists, in the 2023-2024 academic year ensured development of employability skills concurrently with the English language skills. Calculated results of the control group compared to the experimental group lead us to the conclusion that additional ESP course in the experimental learning confirms its effectiveness. The results prove that ESP course at technical universities helps widen the Arena quadrant that proves the development of some soft (personal and social) skills of engineering students.

The results of the study can be useful for future researchers in this field as well as professors, students, and methodologists as it proposes an English for specific purpose course to develop students' employability skills and validates it at the level of confirmation. The experiment was conducted to test the effectiveness of applying pedagogical conditions for developing students' readiness for their future professional work. Students and tutors are provided with a tool to develop attributes that can enhance employability. Ultimately, it assists methodologists in pinpointing activities that cultivate essential student attributes.

6. Limitations

The present study had a number of limitations. The students’ foreign language proficiency (B1) was assessed by Saint Petersburg Mining University's annual introductory test. Only the second-year undergraduate engineering students were asked concerning employability skill development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G. and I.O.; methodology, investigation, data curation, and formal analysis, I.G.; resources, I.O.; writing—original draft preparation, I.G.; writing—review and editing, I.G. and I.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Empress Catherine II Saint Petersburg Mining University (protocol code 004-14.01-25 dated 14.01.2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request from the editorial board representative.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A Career Adapt Abilities Scale

Before ESP training

Figure A1.

Median variable “Wondering what my future will be like” (before the experiment).

Figure A1.

Median variable “Wondering what my future will be like” (before the experiment).

Figure A2.

Median variable “Knowing that today's choices determine my future” (before the experiment).

Figure A2.

Median variable “Knowing that today's choices determine my future” (before the experiment).

Figure A3.

Median variable “Preparing for the future” (before the experiment).

Figure A3.

Median variable “Preparing for the future” (before the experiment).

Figure A4.

Median variable “Making wise choices of education and career” (before the experiment).

Figure A4.

Median variable “Making wise choices of education and career” (before the experiment).

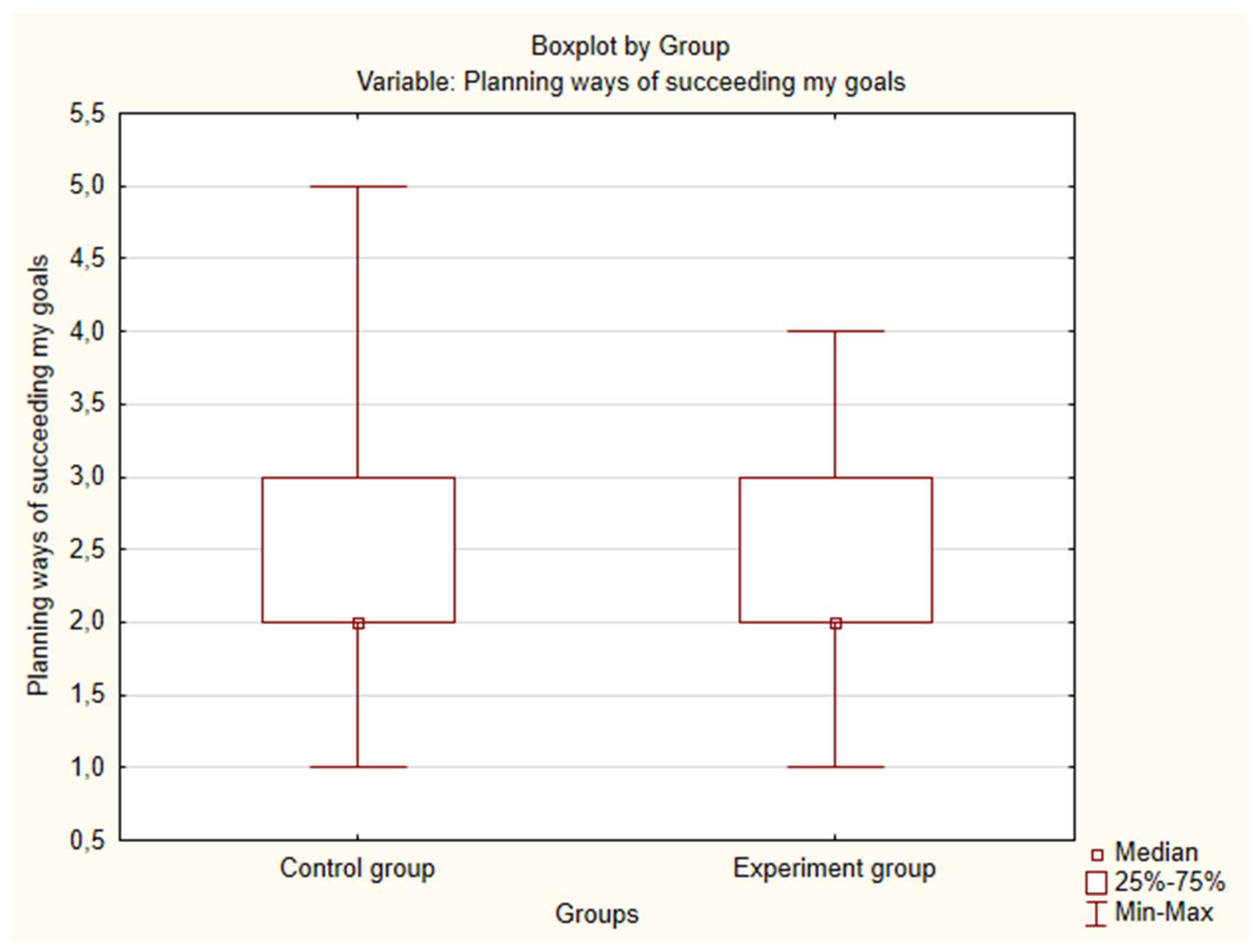

Figure A5.

Median variable “Planning ways of achieving my goals” (before the experiment).

Figure A5.

Median variable “Planning ways of achieving my goals” (before the experiment).

Figure A6.

Median variable “Concerns about career advancing” (before the experiment).

Figure A6.

Median variable “Concerns about career advancing” (before the experiment).

Figure A7.

Median variable “Encouraging spirit and feeding mind and body” (before the experiment).

Figure A7.

Median variable “Encouraging spirit and feeding mind and body” (before the experiment).

Figure A8.

Median variable “Making decisions independently” (before the experiment).

Figure A8.

Median variable “Making decisions independently” (before the experiment).

Figure A9.

Median variable “Taking responsibility for the actions” (before the experiment).

Figure A9.

Median variable “Taking responsibility for the actions” (before the experiment).

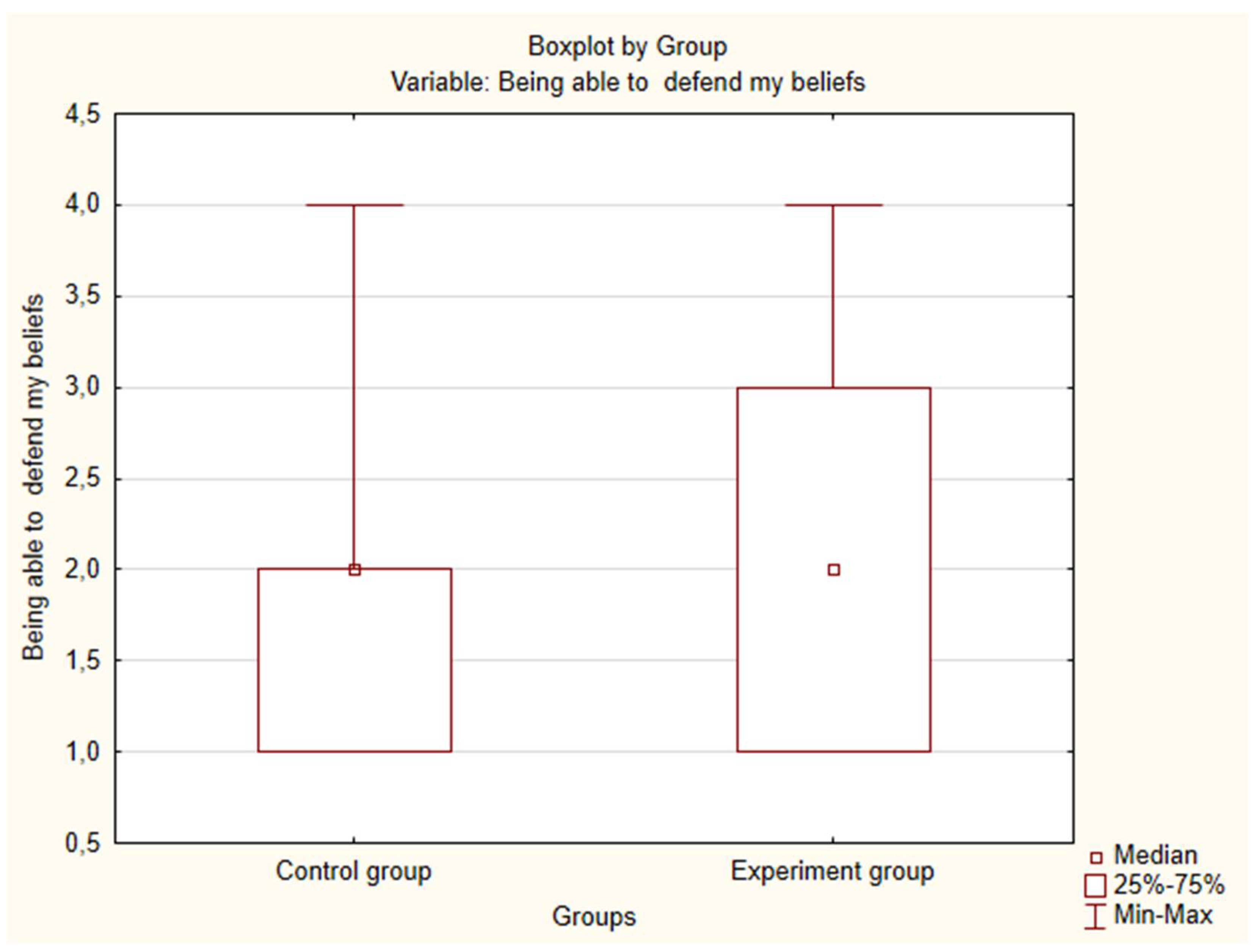

Figure A10.

Median variable “Being able to defend my beliefs” (before the experiment).

Figure A10.

Median variable “Being able to defend my beliefs” (before the experiment).

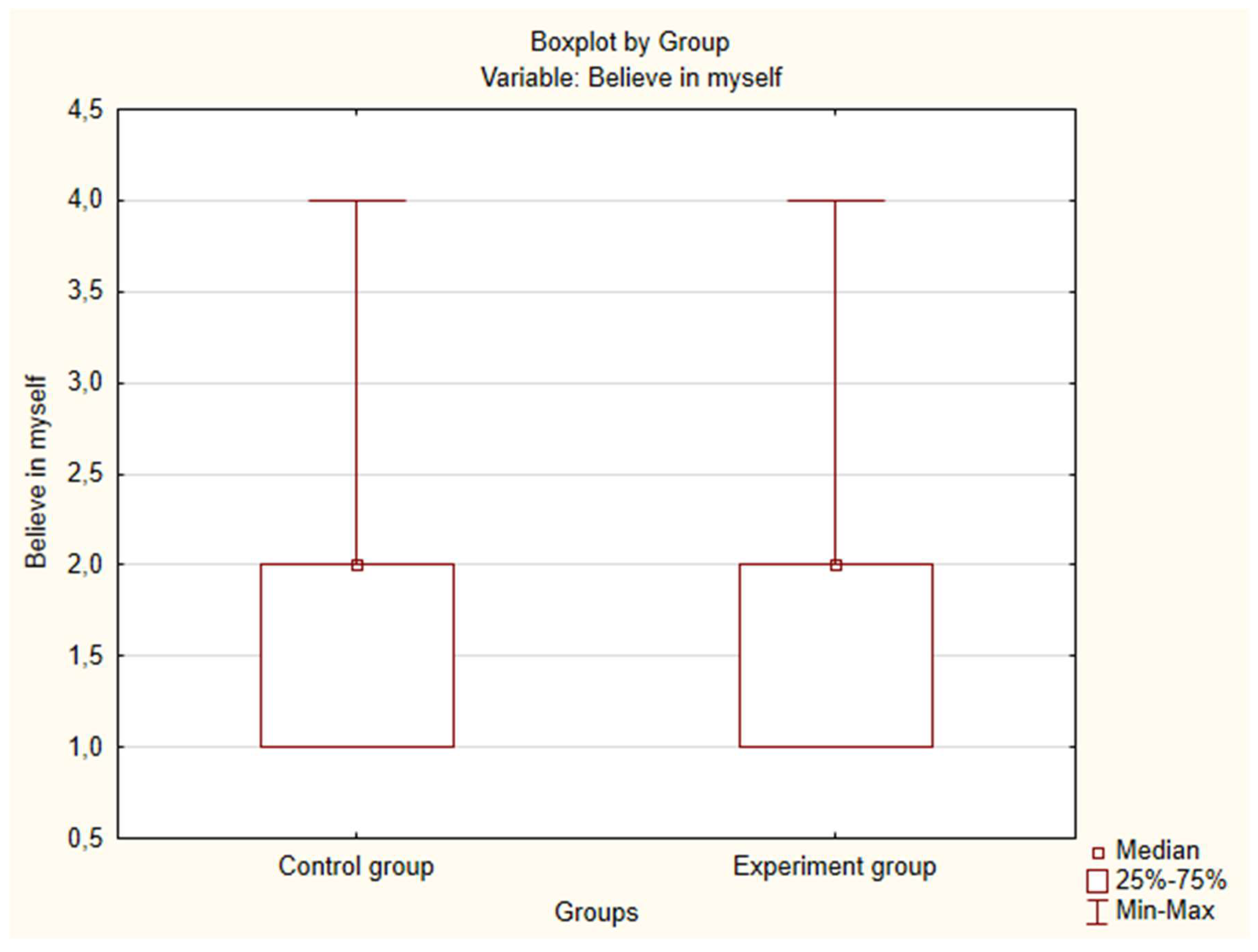

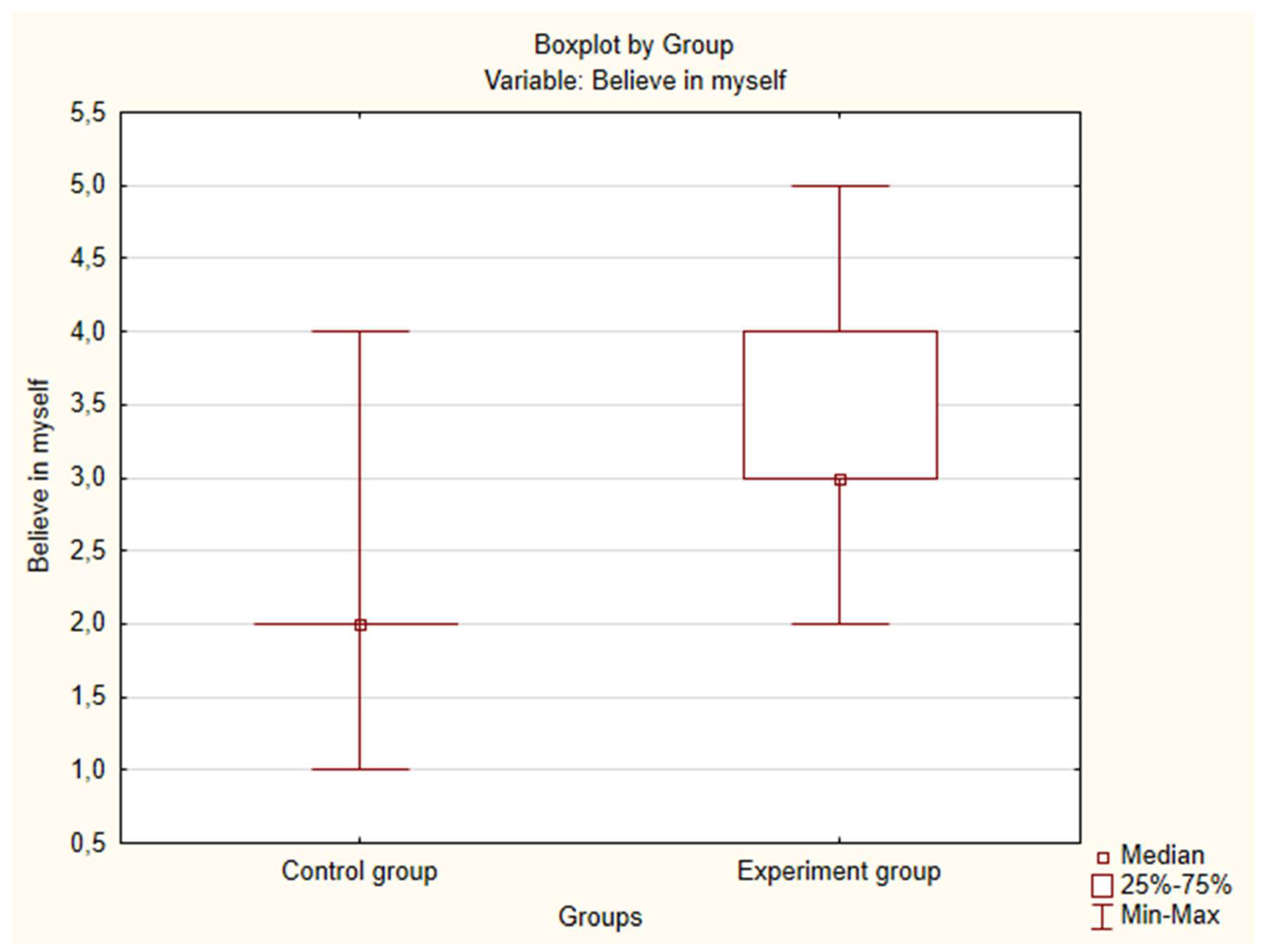

Figure A11.

Median variable “Believe in myself” (before the experiment).

Figure A11.

Median variable “Believe in myself” (before the experiment).

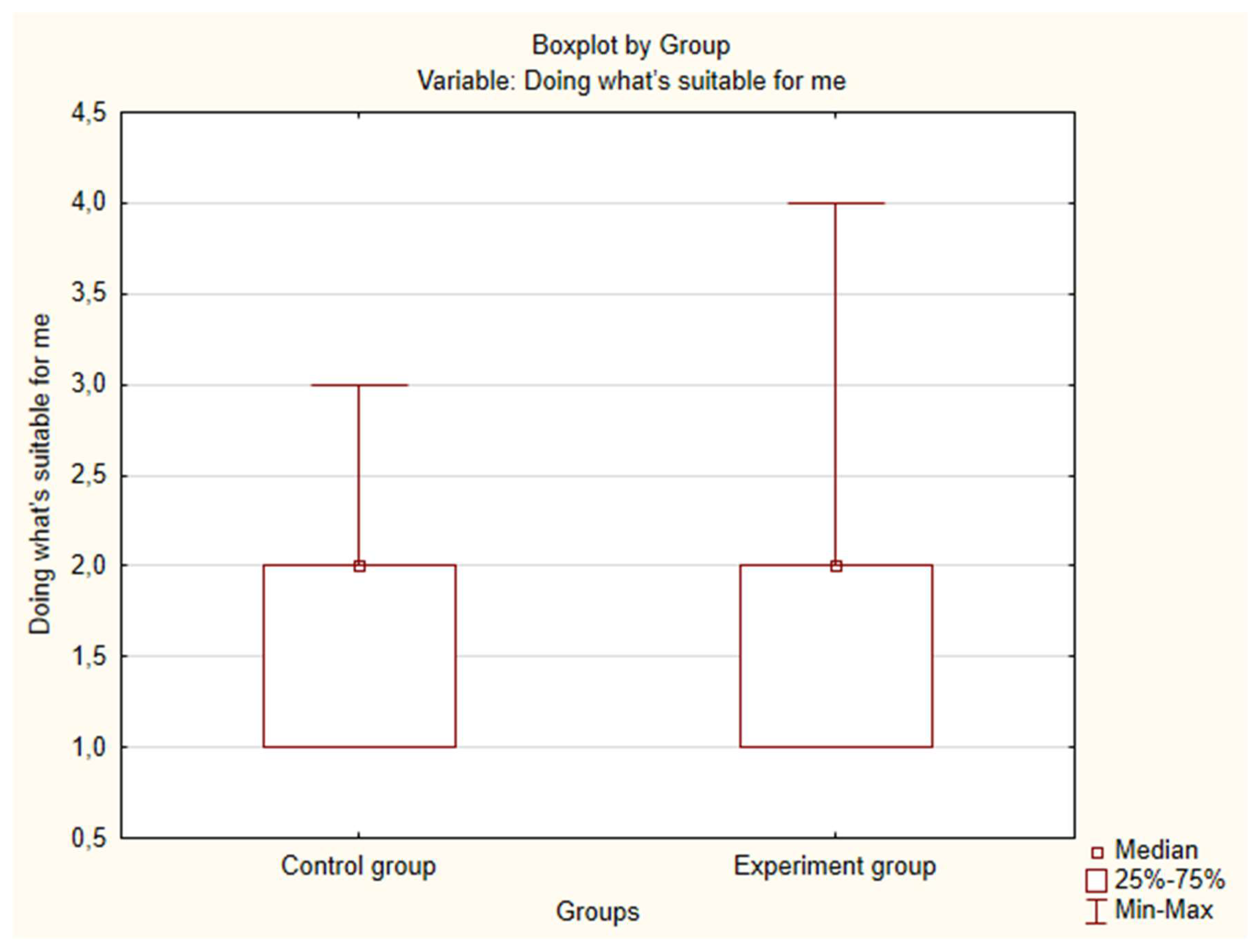

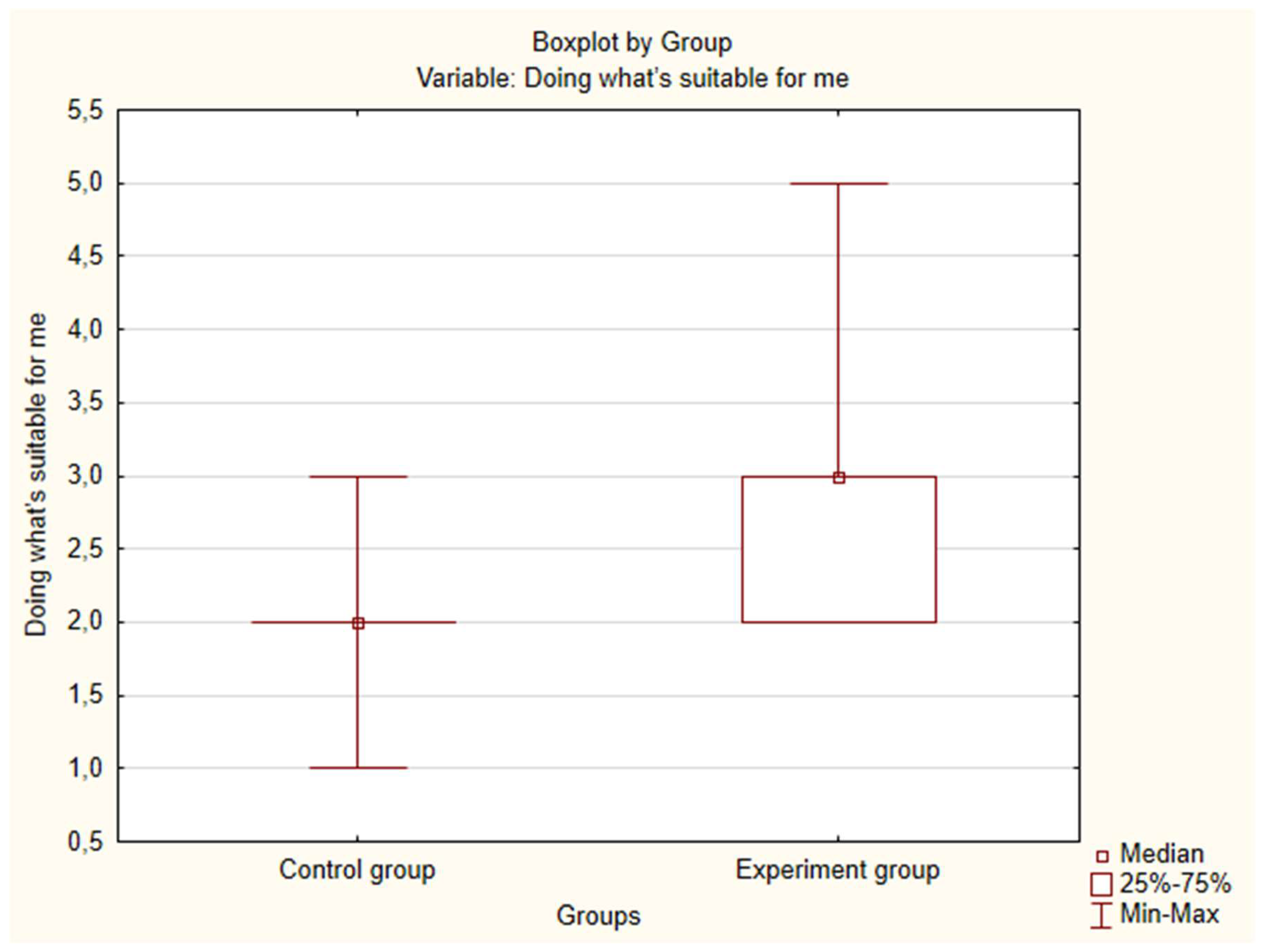

Figure A12.

Median variable “Doing what's suitable for me” (before the experiment).

Figure A12.

Median variable “Doing what's suitable for me” (before the experiment).

Figure A13.

Median variable “Examining the professional field” (before the experiment).

Figure A13.

Median variable “Examining the professional field” (before the experiment).

Figure A14.

Median variable “Looking for possibilities for personal growth” (before the experiment).

Figure A14.

Median variable “Looking for possibilities for personal growth” (before the experiment).

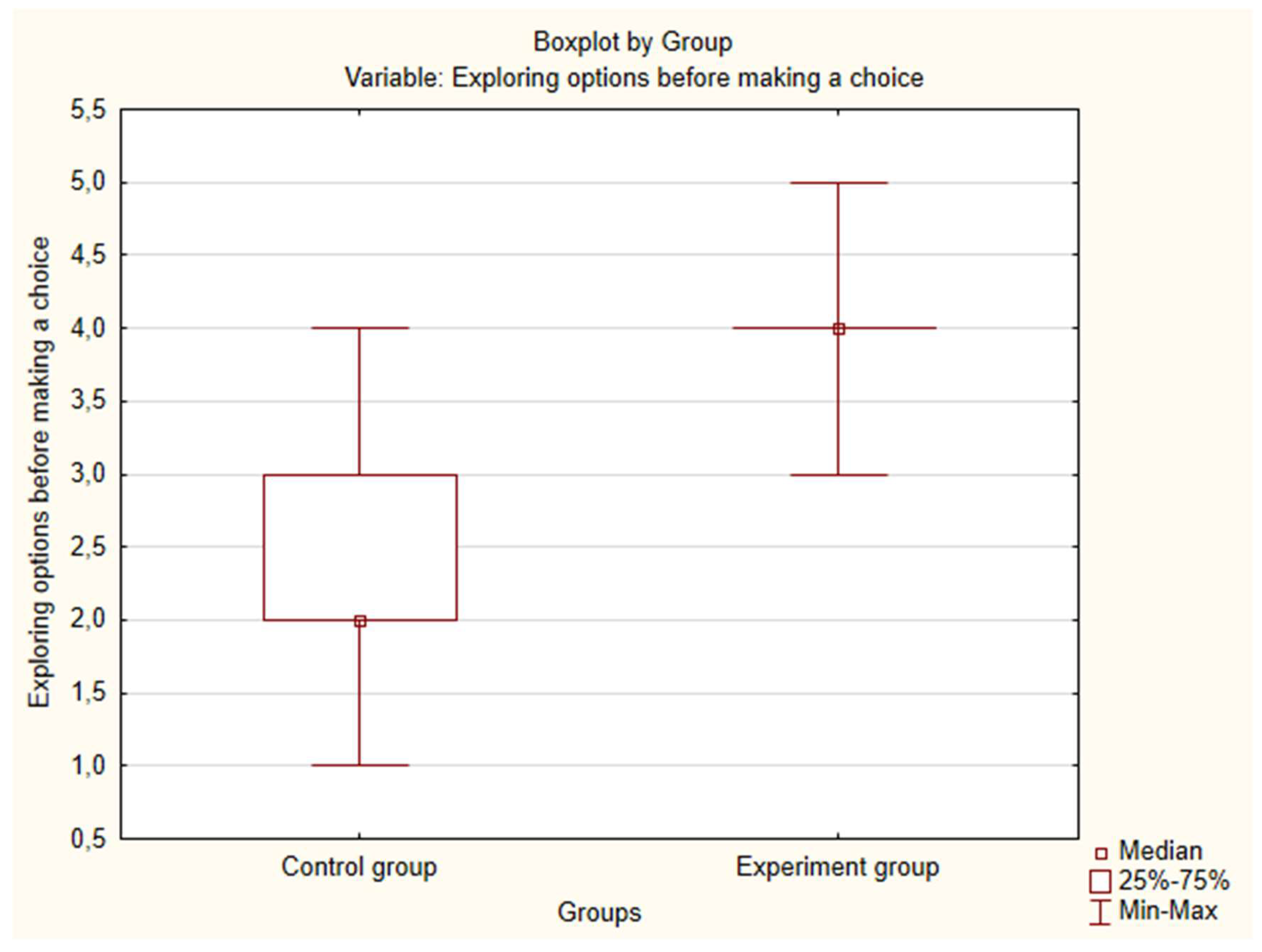

Figure A15.

Median variable “Exploring options before making a choice” (before the experiment).

Figure A15.

Median variable “Exploring options before making a choice” (before the experiment).

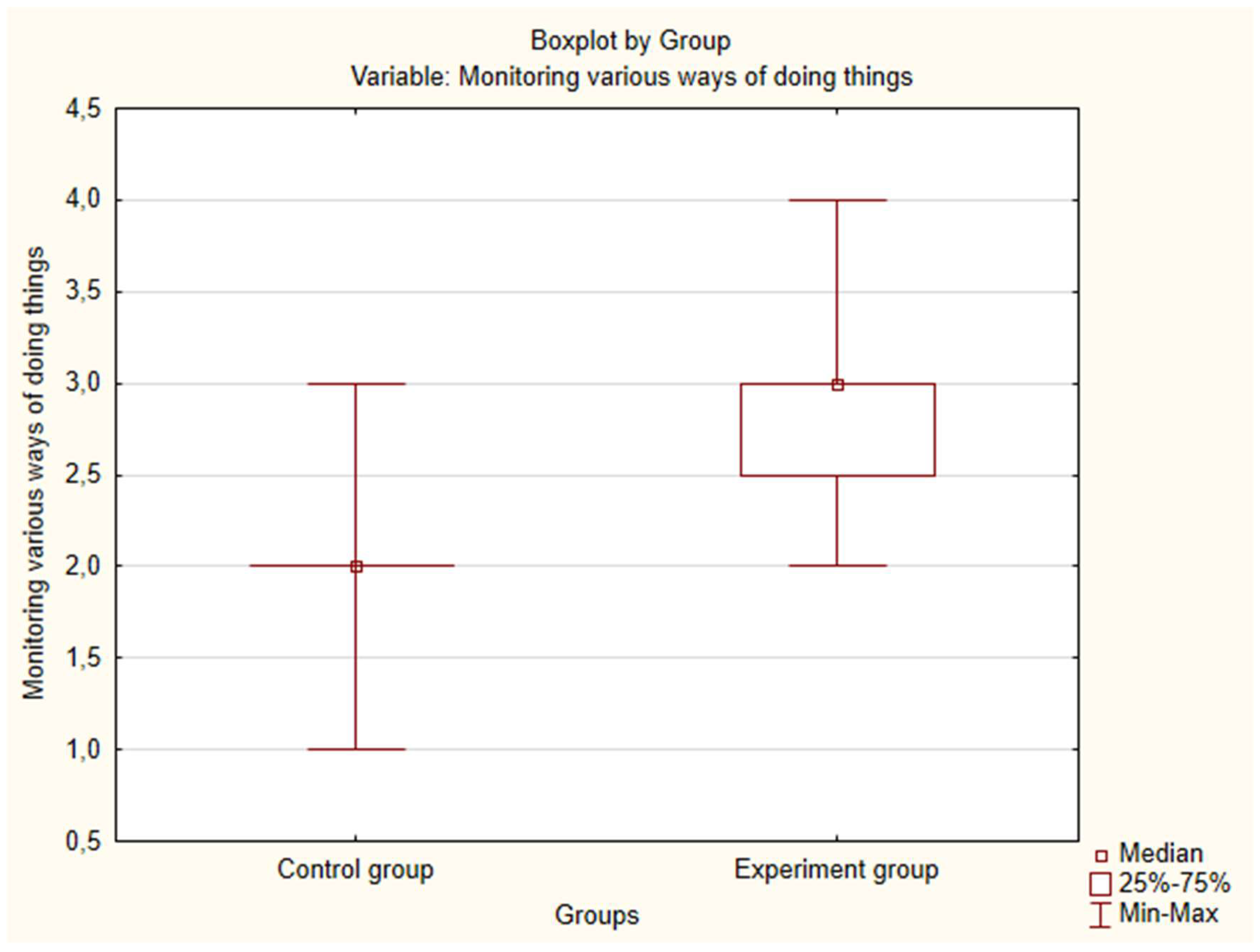

Figure A16.

Median variable “Monitoring various ways of doing things” (before the experiment).

Figure A16.

Median variable “Monitoring various ways of doing things” (before the experiment).

Figure A17.

Median variable “Thinking deeply about the issues I have” (before the experiment).

Figure A17.

Median variable “Thinking deeply about the issues I have” (before the experiment).

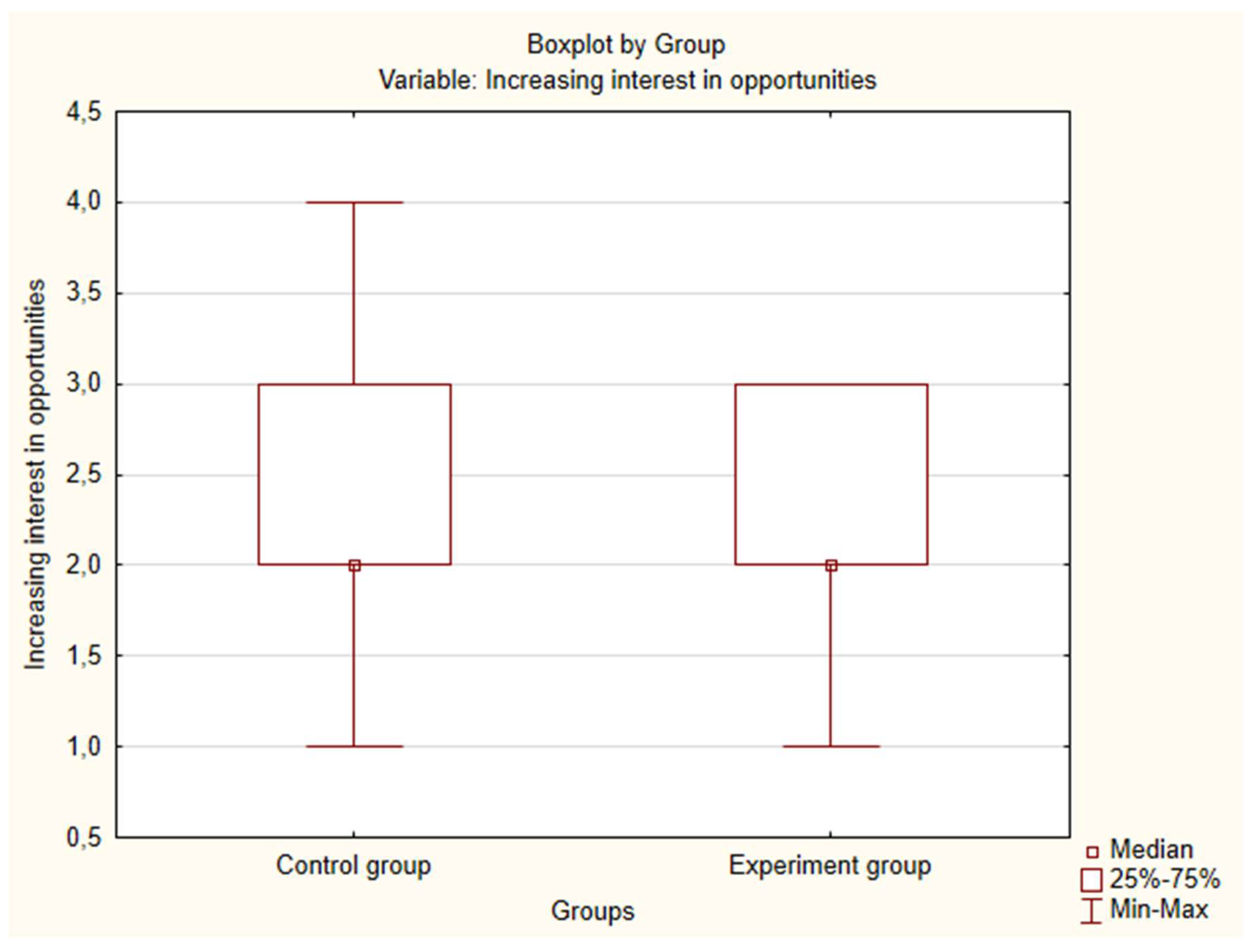

Figure A18.

Median variable “Increasing interest in opportunities” (before the experiment).

Figure A18.

Median variable “Increasing interest in opportunities” (before the experiment).

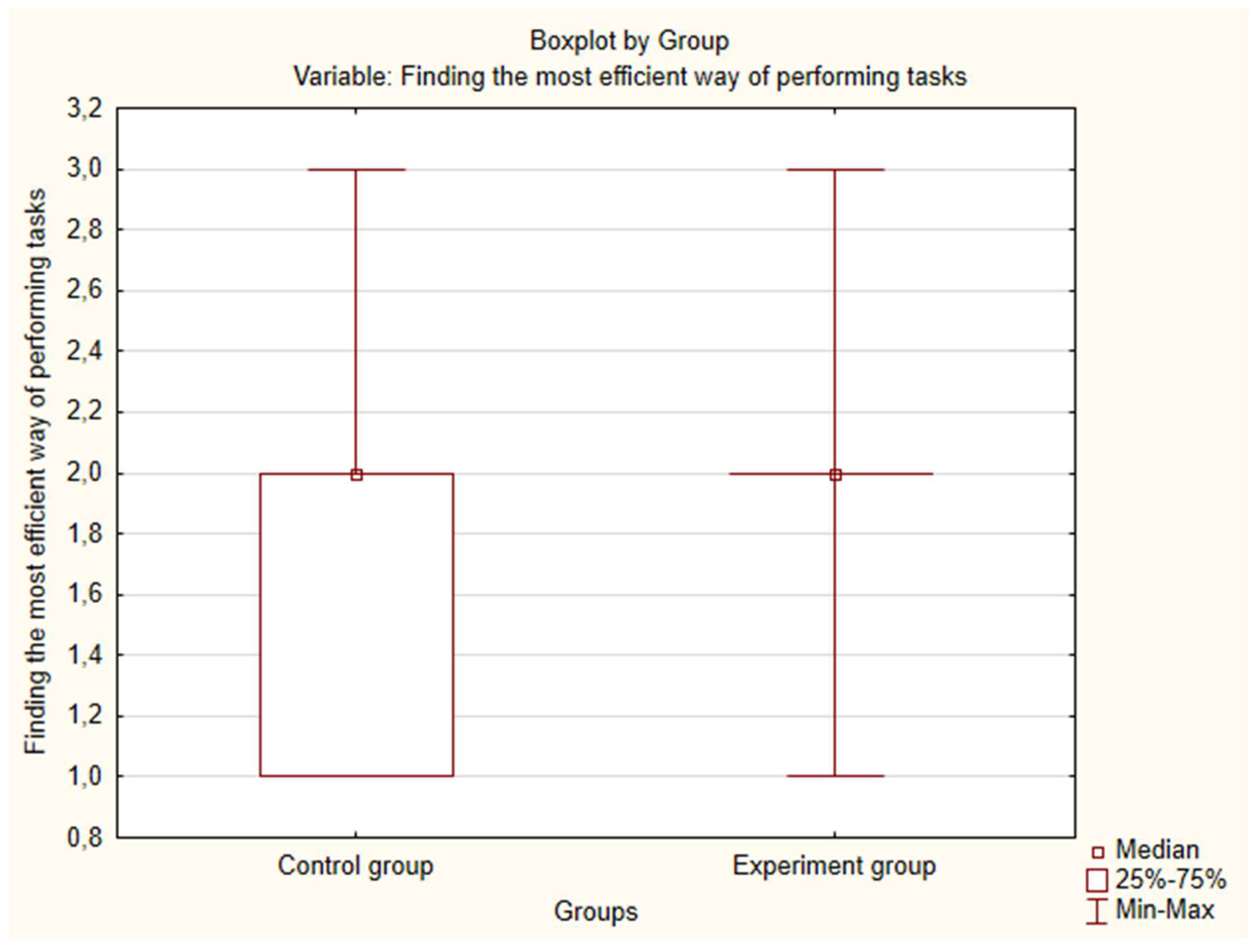

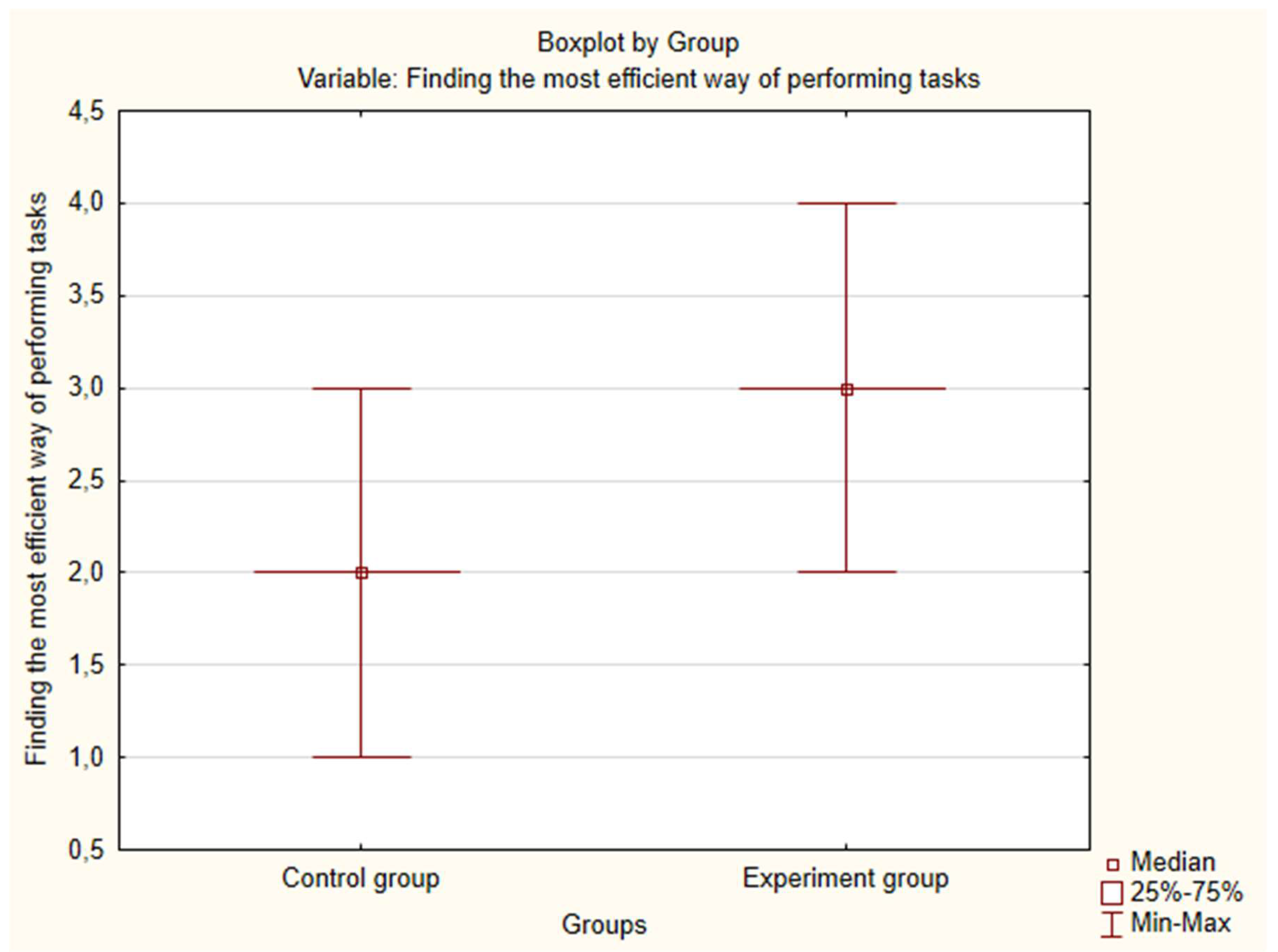

Figure A19.

Median variable “Finding the most efficient way of performing tasks” (before the experiment).

Figure A19.

Median variable “Finding the most efficient way of performing tasks” (before the experiment).

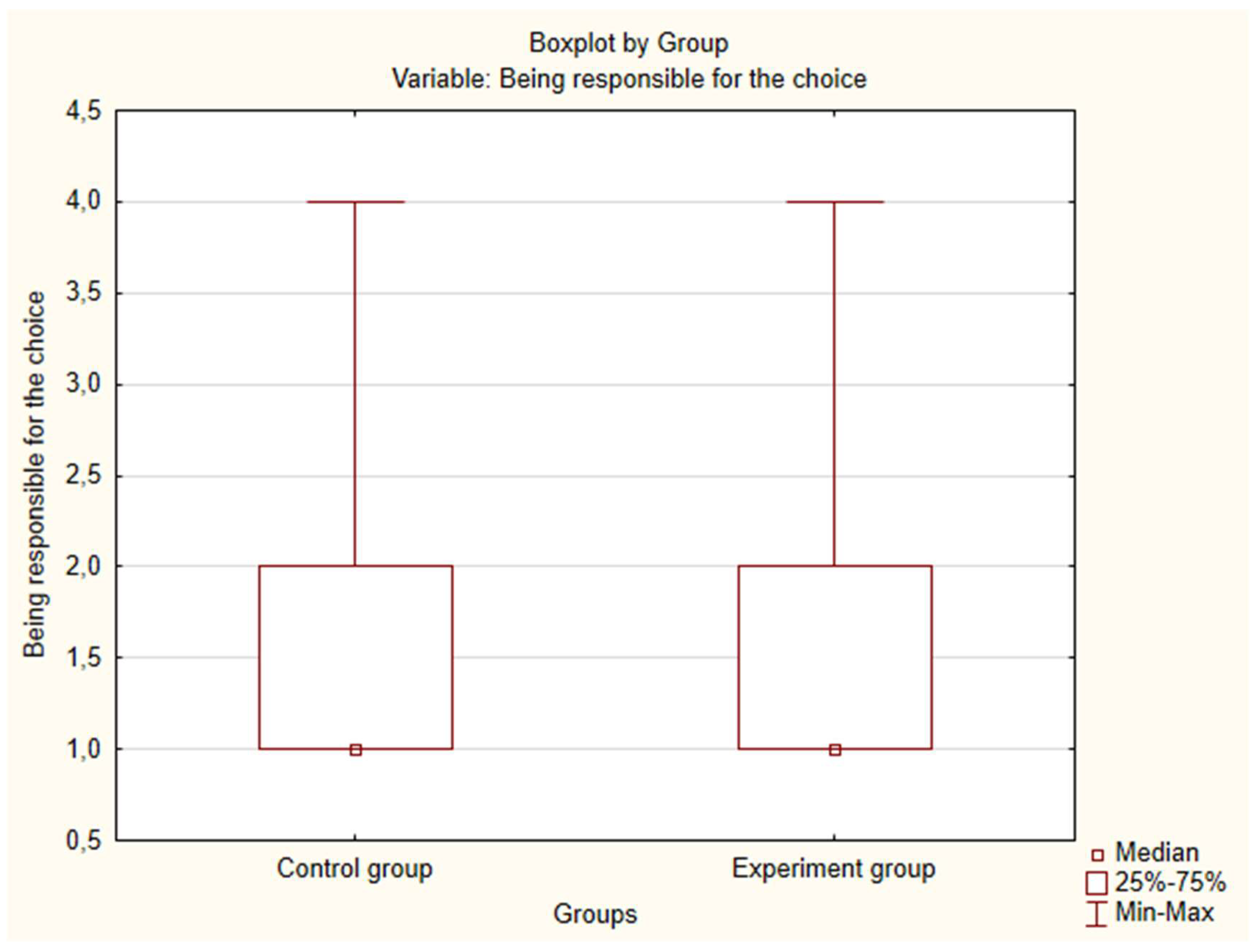

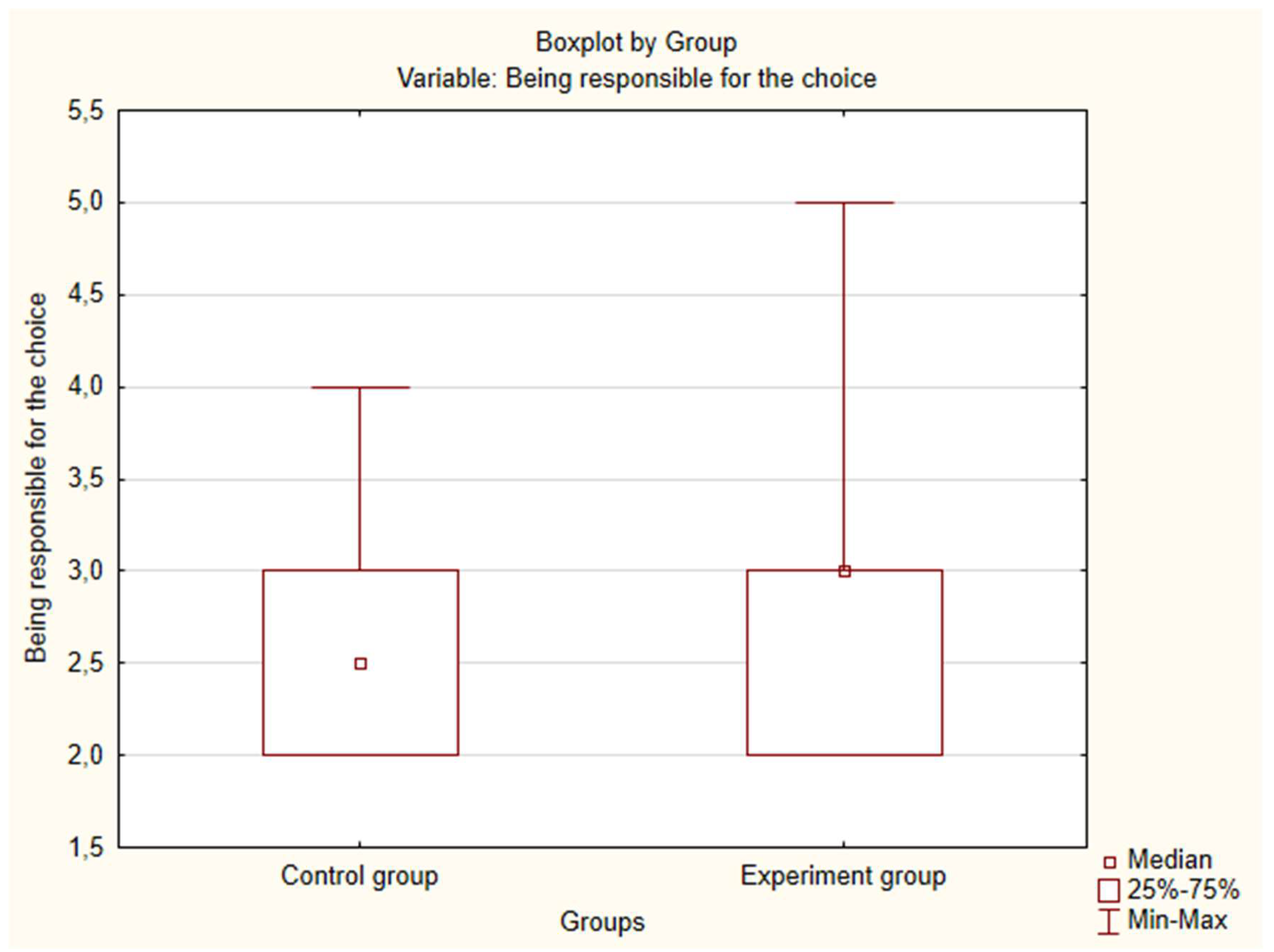

Figure A20.

Median variable “Being responsible for the choice” (before the experiment).

Figure A20.

Median variable “Being responsible for the choice” (before the experiment).

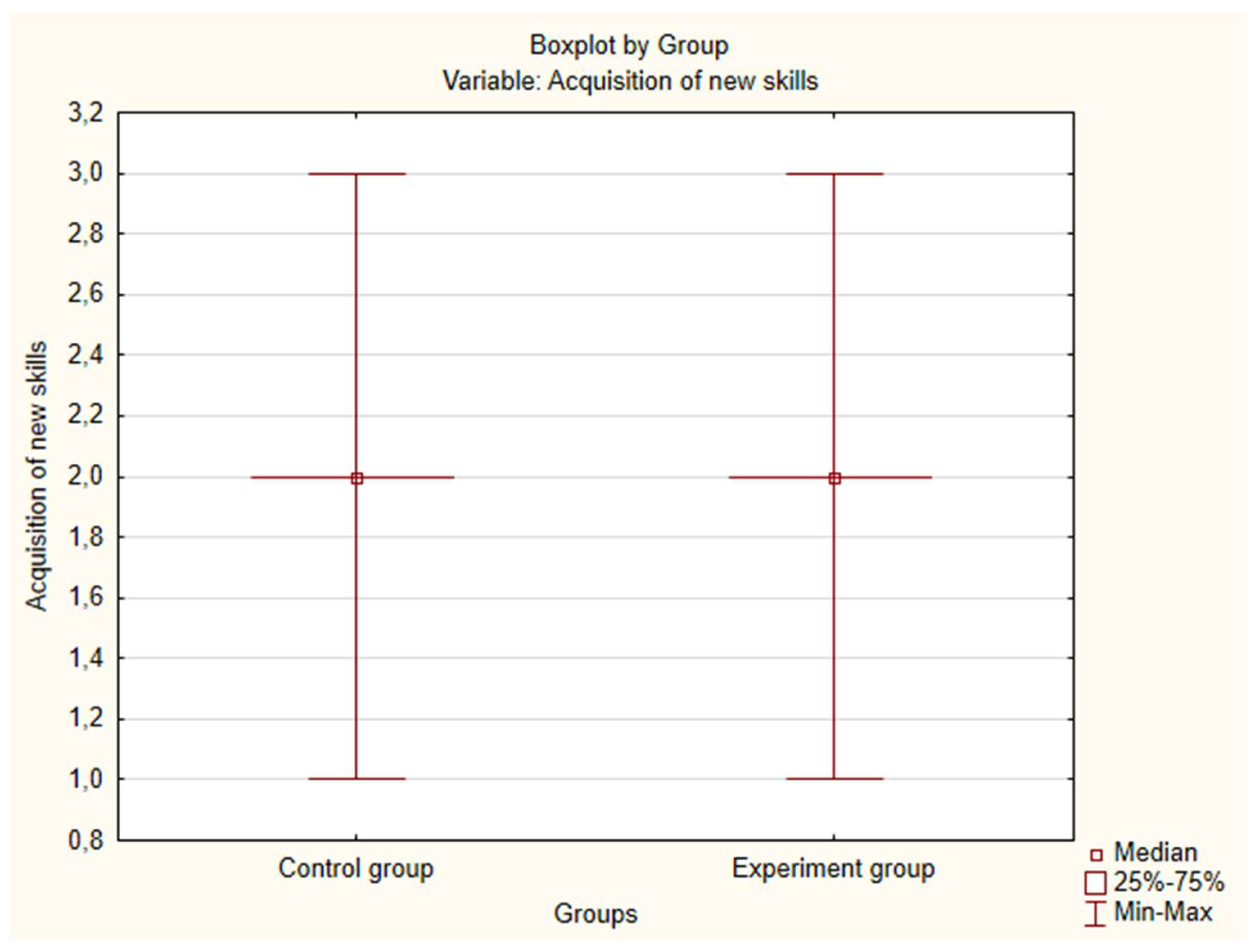

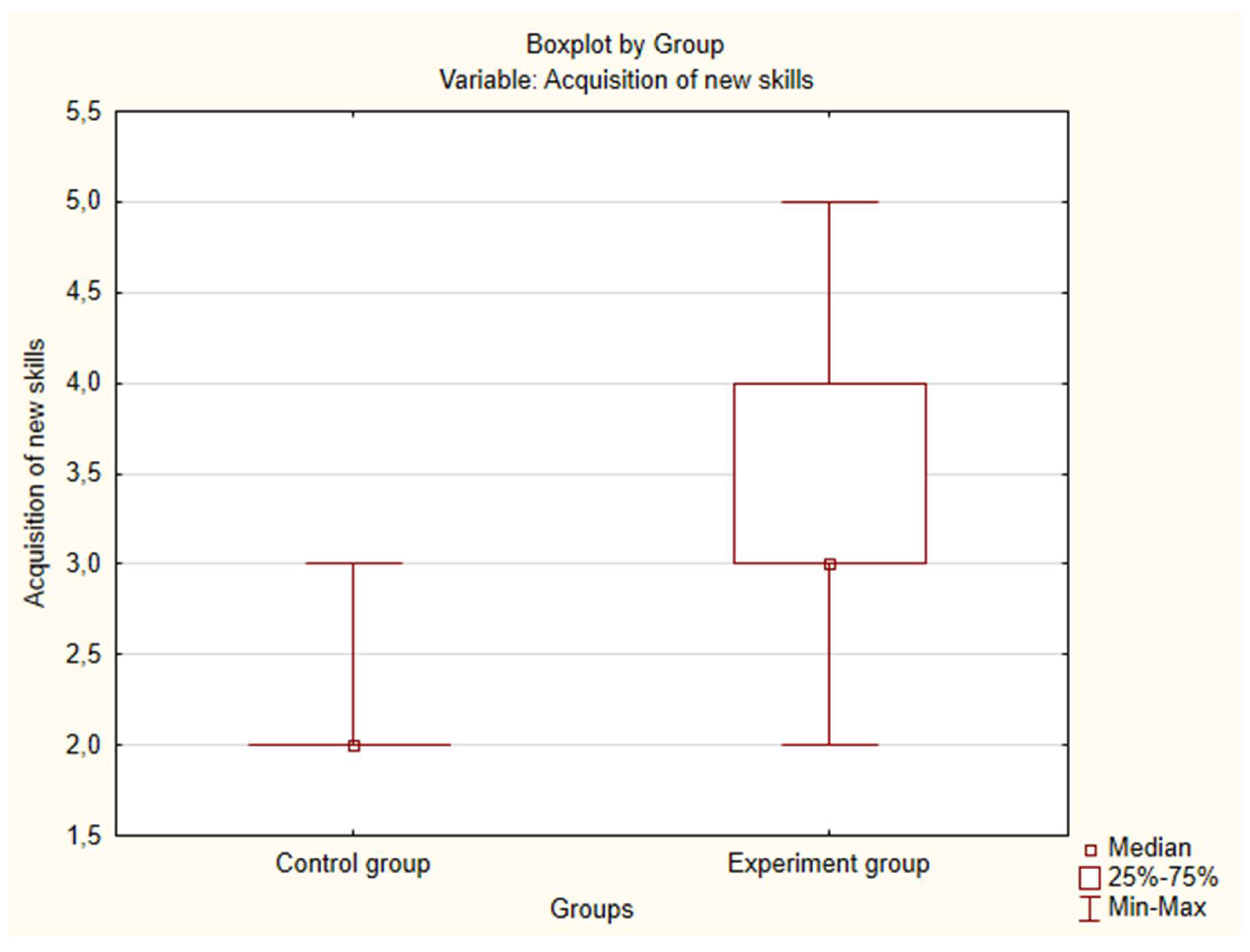

Figure A21.

Median variable “Acquisition of new skills” (before the experiment).

Figure A21.

Median variable “Acquisition of new skills” (before the experiment).

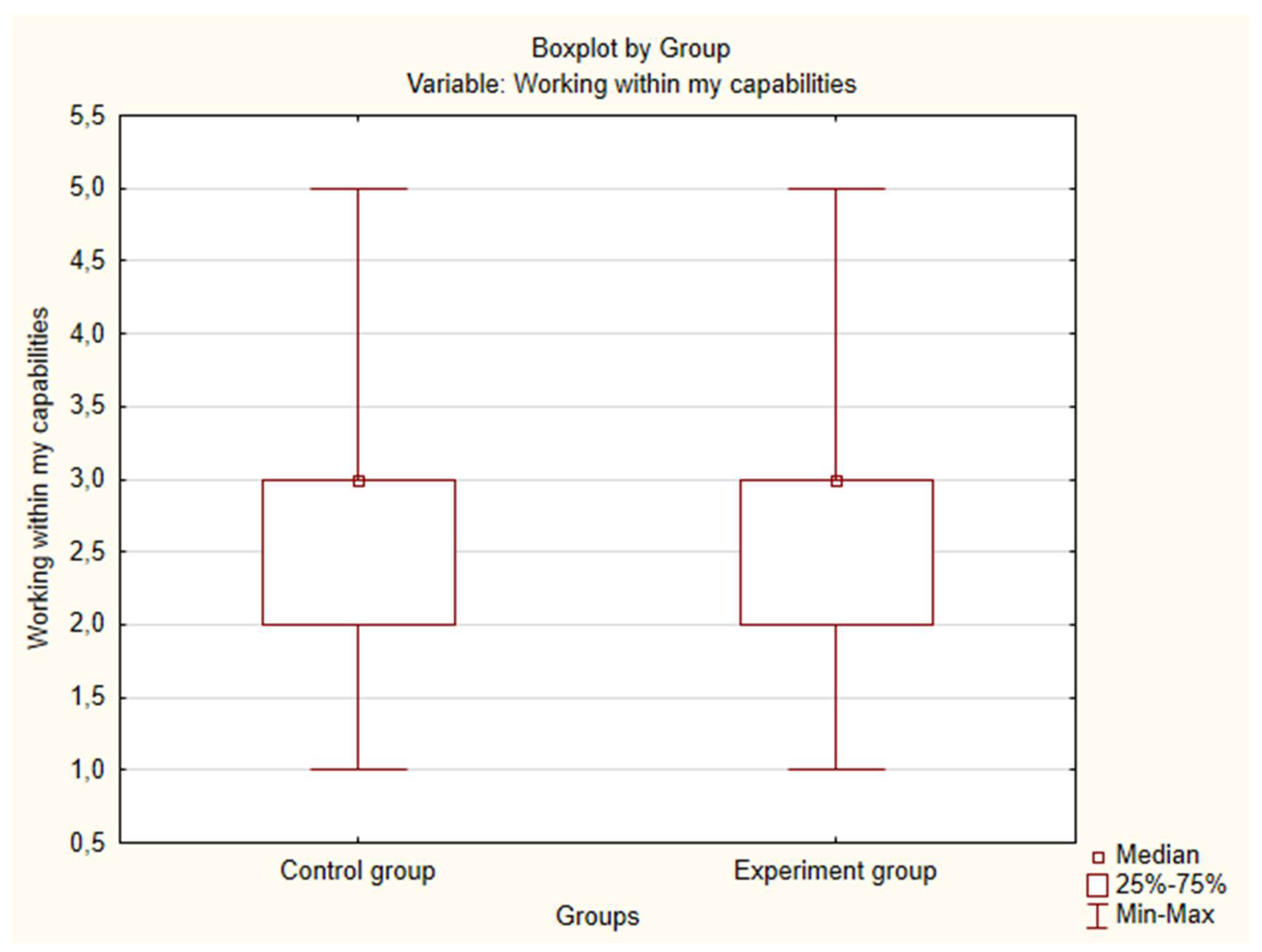

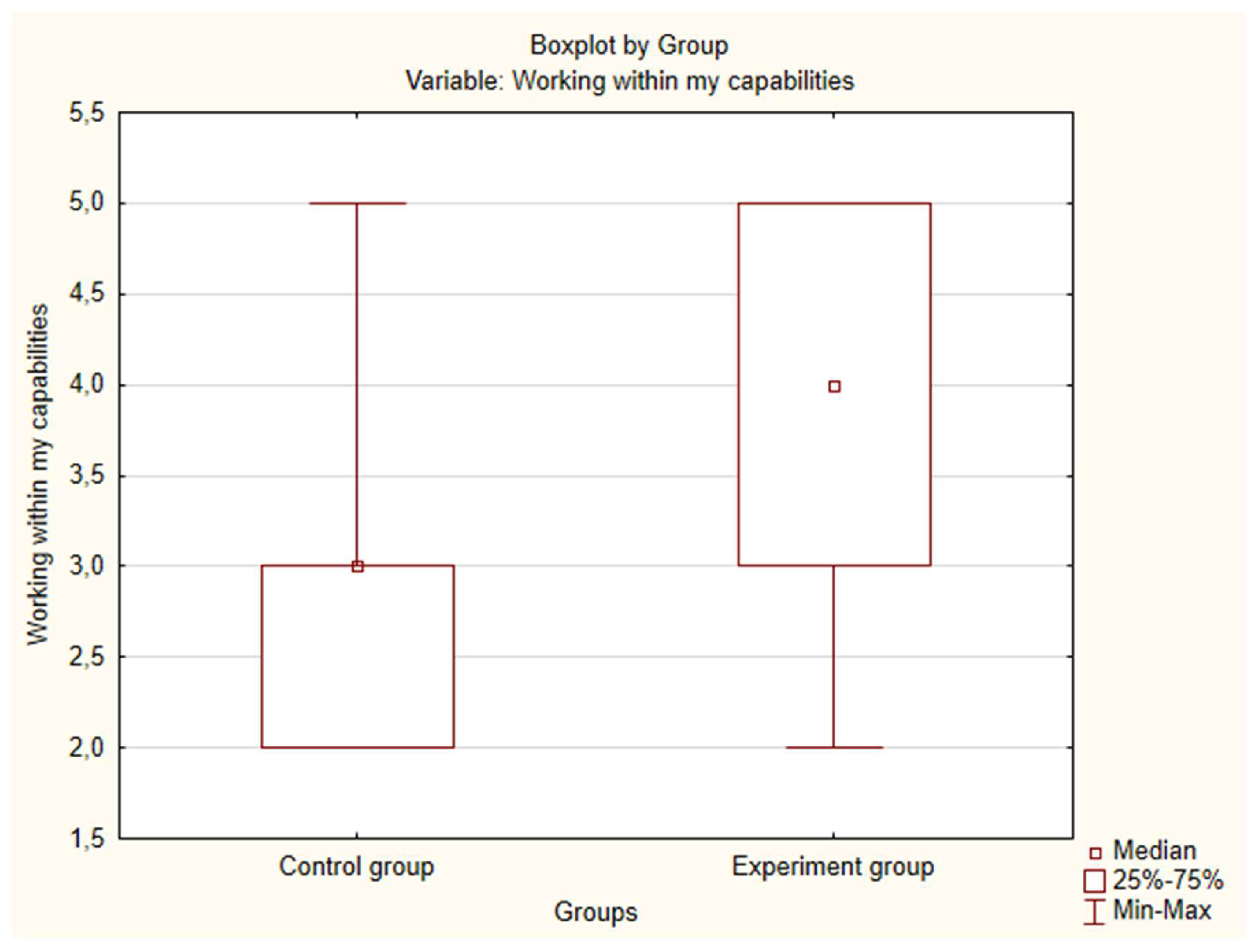

Figure A22.

Median variable “Working within my capabilities” (before the experiment).

Figure A22.

Median variable “Working within my capabilities” (before the experiment).

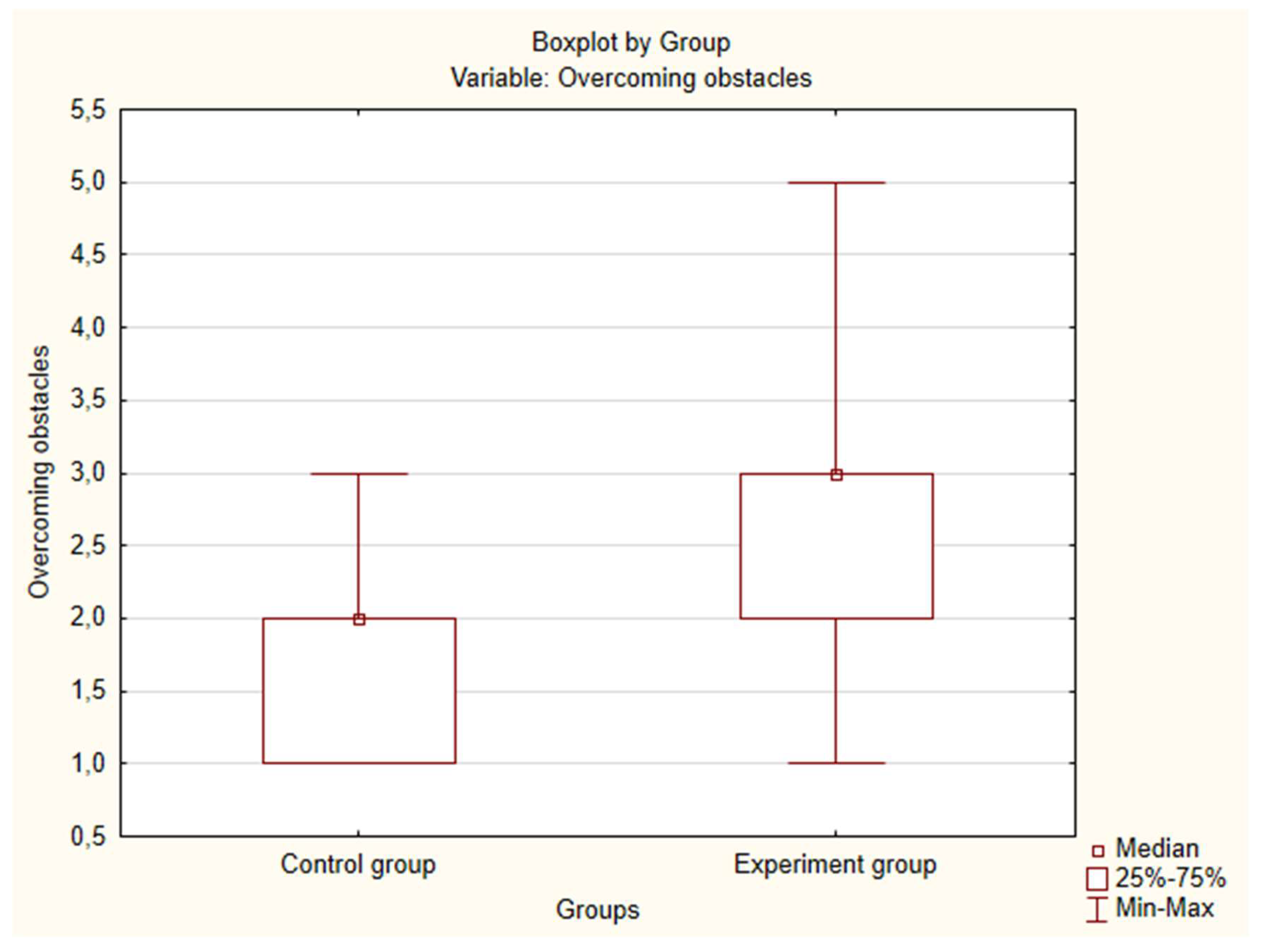

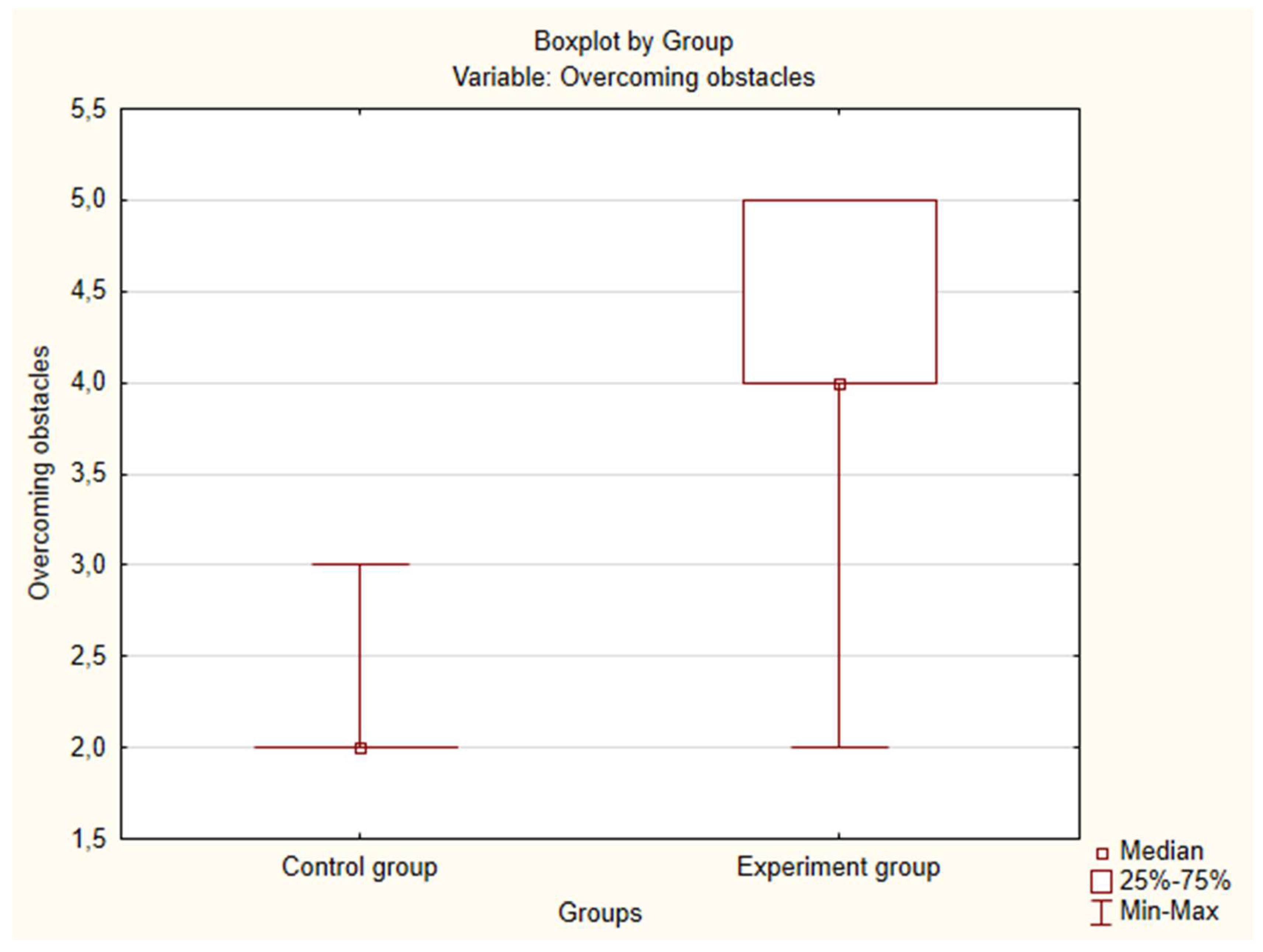

Figure A23.

Median variable “Overcoming obstacles” (before the experiment).

Figure A23.

Median variable “Overcoming obstacles” (before the experiment).

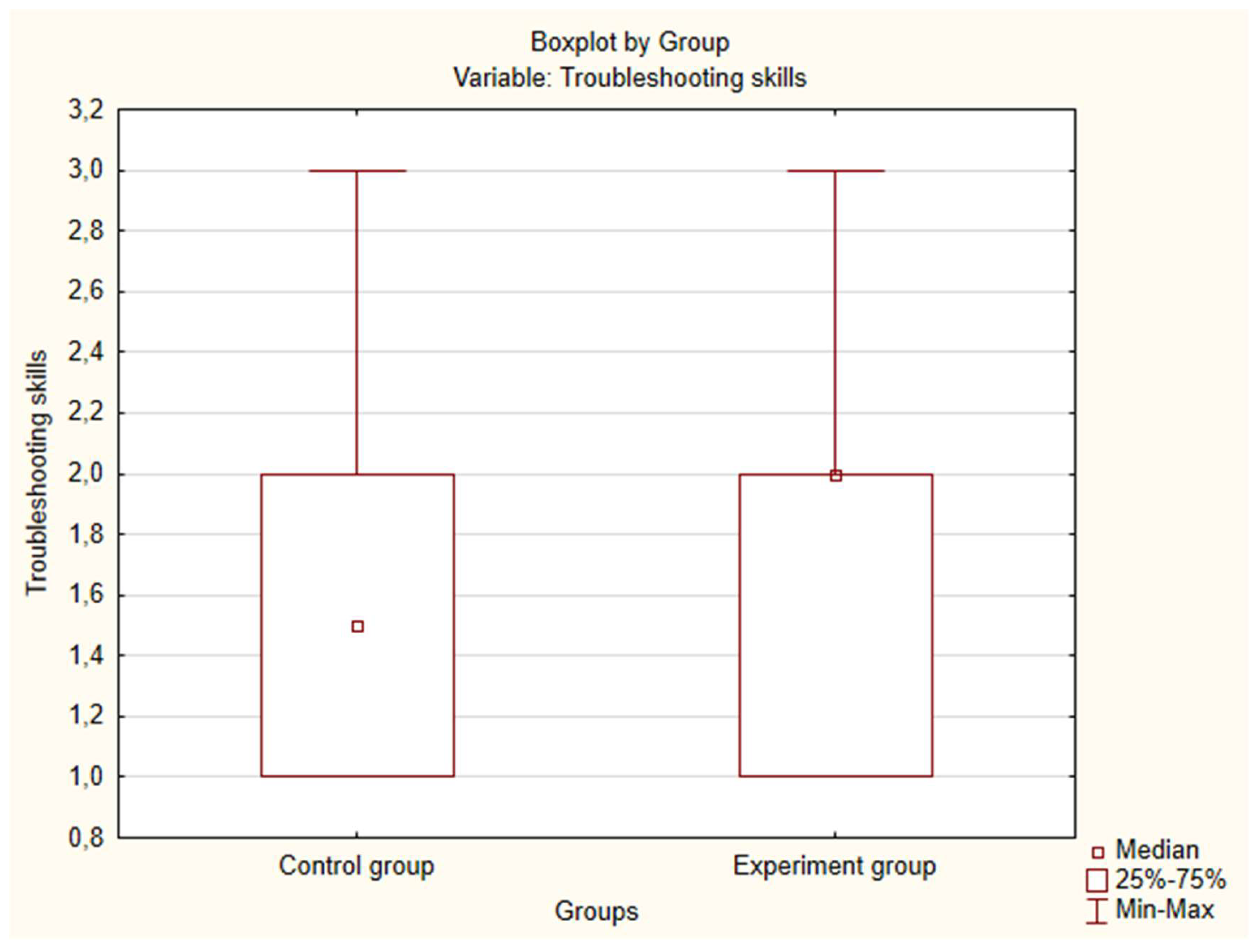

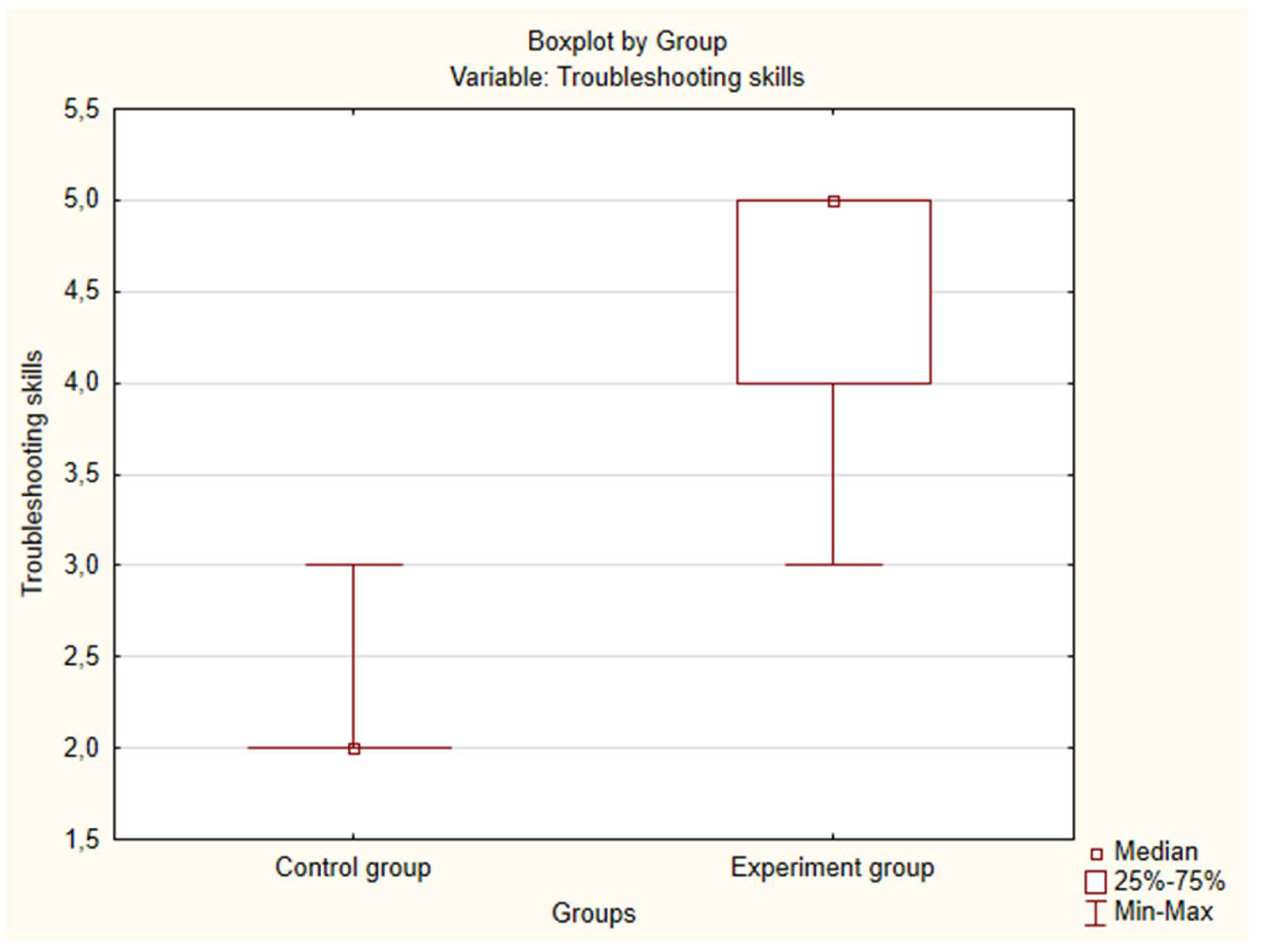

Figure A24.

Median variable “Troubleshooting skills” (before the experiment).

Figure A24.

Median variable “Troubleshooting skills” (before the experiment).

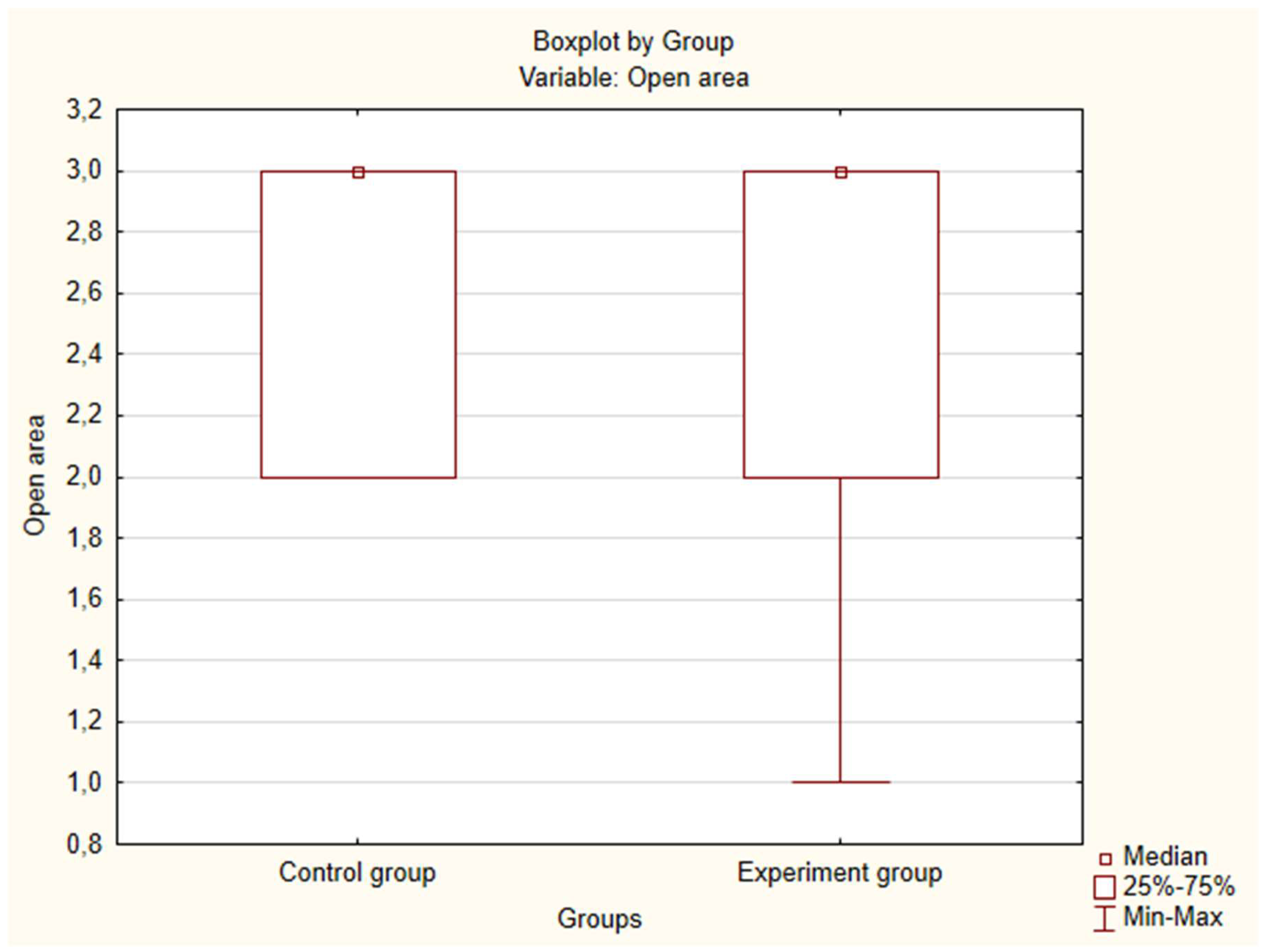

Appendix B. Johari Window test

Figure 1.

Median variable Open area (before the experiment).

Figure 1.

Median variable Open area (before the experiment).

Figure 2.

Median variable Blind area (before the experiment).

Figure 2.

Median variable Blind area (before the experiment).

Figure 3.

Median variable Hidden area (before the experiment).

Figure 3.

Median variable Hidden area (before the experiment).

Figure 4.

Median variable Unknown area (before the experiment).

Figure 4.

Median variable Unknown area (before the experiment).

Appendix C Career Adapt Abilities Scale

After ESP training

Figure 1.

Median variable “Wondering what my future will be like” (after the experiment).

Figure 1.

Median variable “Wondering what my future will be like” (after the experiment).

Figure 2.

Median variable “Knowing that today's choices determine my future” (after the experiment).

Figure 2.

Median variable “Knowing that today's choices determine my future” (after the experiment).

Figure 3.

Median variable “Preparing for the future” (after the experiment).

Figure 3.

Median variable “Preparing for the future” (after the experiment).

Figure 4.

Median variable “Making wise choices of education and career” (after the experiment).

Figure 4.

Median variable “Making wise choices of education and career” (after the experiment).

Figure 5.

Median variable “Planning ways of achieving my goals” (after the experiment).

Figure 5.

Median variable “Planning ways of achieving my goals” (after the experiment).

Figure 6.

Median variable “Concerns about career advancing” (after the experiment).

Figure 6.

Median variable “Concerns about career advancing” (after the experiment).

Figure 7.

Median variable “Encouraging spirit and feeding mind and body” (after the experiment).

Figure 7.

Median variable “Encouraging spirit and feeding mind and body” (after the experiment).

Figure 8.

Median variable “Making decisions independently” (after the experiment).

Figure 8.

Median variable “Making decisions independently” (after the experiment).

Figure 9.

Median variable “Taking responsibility for the actions” (after the experiment).

Figure 9.

Median variable “Taking responsibility for the actions” (after the experiment).

Figure 10.

Median variable “Being able to defend my beliefs” (after the experiment).

Figure 10.

Median variable “Being able to defend my beliefs” (after the experiment).

Figure 11.

Median variable “Believe in myself” (after the experiment).

Figure 11.

Median variable “Believe in myself” (after the experiment).

Figure 12.

Median variable “Doing what's suitable for me” (after the experiment).

Figure 12.

Median variable “Doing what's suitable for me” (after the experiment).

Figure 13.

Median variable “Examining the professional field” (after the experiment).

Figure 13.

Median variable “Examining the professional field” (after the experiment).

Figure 14.

Median variable “Looking for possibilities for personal growth” (after the experiment).

Figure 14.

Median variable “Looking for possibilities for personal growth” (after the experiment).

Figure 15.

Median variable “Exploring options before making a choice” (after the experiment).

Figure 15.

Median variable “Exploring options before making a choice” (after the experiment).

Figure 16.

Median variable “Monitoring various ways of doing things” (after the experiment).

Figure 16.

Median variable “Monitoring various ways of doing things” (after the experiment).

Figure 17.

Median variable “Thinking deeply about the issues I have” (after the experiment).

Figure 17.

Median variable “Thinking deeply about the issues I have” (after the experiment).

Figure 18.

Median variable “Increasing interest in opportunities” (after the experiment).

Figure 18.

Median variable “Increasing interest in opportunities” (after the experiment).

Figure 19.

Median variable “Finding the most efficient way of performing tasks” (after the experiment).

Figure 19.

Median variable “Finding the most efficient way of performing tasks” (after the experiment).

Figure 20.

Median variable “Being responsible for the choice” (after the experiment).

Figure 20.

Median variable “Being responsible for the choice” (after the experiment).

Figure 21.

Median variable “Acquisition of new skills” (after the experiment).

Figure 21.

Median variable “Acquisition of new skills” (after the experiment).

Figure 22.

Median variable “Working within my capabilities” (after the experiment).

Figure 22.

Median variable “Working within my capabilities” (after the experiment).

Figure 23.

Median variable “Overcoming obstacles” (after the experiment).

Figure 23.

Median variable “Overcoming obstacles” (after the experiment).

Figure 24.

Median variable “Troubleshooting skills” (after the experiment).

Figure 24.

Median variable “Troubleshooting skills” (after the experiment).

Appendix D. Johari Window test

Figure 1.

Median variable “Open area” (after the experiment).

Figure 1.

Median variable “Open area” (after the experiment).

Figure D2.

Median variable “Blind area” (after the experiment).

Figure D2.

Median variable “Blind area” (after the experiment).

Figure 3.

Median variable “Hidden area” (after the experiment).

Figure 3.

Median variable “Hidden area” (after the experiment).

Figure 4.

Median variable “Unknown area” (after the experiment).

Figure 4.

Median variable “Unknown area” (after the experiment).

References

- Bazhin, Issa, 2021 – Bazhin, V.Yu., Issa, B. (2021). Influence of heat treatment on the microstructure of steel coils of a heating tube furnace. Journal of Mining Institute. 249: 393-400. [CrossRef]

- Bernstrøm, V. H., Drange, I., & Mamelund, S. E. (2019). Employability as an alternative to job security. Personnel Review, 48(1), 234–248. [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, N. (2011). Management education: An approach towards nurturing students' employabilityskills–A study on Tripura students. International Journal of Educational Research and Technology,2(2), 20–29.

- Chell, E., & Athayde, R. (2011). Planning for uncertainty: Soft skills, hard skills and innovation. Reflec-tive Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, 12(5), 615–628. [CrossRef]

- Cullen, R. & Harris, M. (2009) Assessing learner-centrednessthrough course syllabi, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34:1, 115-125. (PDF) Assessing Learner-Centredness Through Course Syllabi. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233056548_Assessing_Learner-Centredness_Through_Course_Syllabi [accessed Dec 10 2024]. [CrossRef]

- Dash, K. K., Satpathy, S., & Dash, S. K. (2020). English languageteaching: Exploring enhanced employability through soft skills.Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities,12(6), 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Davies, L. (2000). Why kick the “L” out of “LEarning”? The development of students’ employability skillsthrough part-time working. Education + Training, 42, (8), 436-445. Economic Times. [CrossRef]

- Evans, C. (2015) Exploring students’ emotions and emotional regulation of feedback in the context of learningto teach. In: Donche, V., De Maeyer, S., Gijbels, D. and van den Bergh, H. (eds.) (2015) Methodologicalchallenges in research on student learning. Garant: Antwerpen, pp. 107-60.

- Forrier, A., & Sels, L. (2003). The concept employability: a complex mosaic. International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management, 3, pp. 102–124. [CrossRef]

- Fugate, M., Kinicki, A. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (2004). Employability: a psycho-social construct, its dimensions, and applications. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 65(1), pp. 14–38. [CrossRef]

- Hinchliffe, G.W. & Jolly, A. (2011). Graduate identity and employability. British Educational Research Journal, 37(4), 563-584. [CrossRef]

- Johari Window of Personality Test online. Available from: https://kevan.org/johari [accessed Dec. 26 2024].

- Jantassova, D.; Churchill, D.; Tentekbayeva, Z.; Aitbayeva, S. STEM Language Literacy Learning in Engineering Education in Kazakhstan.Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1352. [CrossRef]

- Kharlamova, O.Yu., Zherebkina, O.S., Kremneva, A.V. (2023). Teaching Vocational Oriented Foreign Language Reading to Future Oil Field Specialists. European Journal of Contemporary Education. 12(2): 480-492. [CrossRef]

- Knight, P. T., & Yorke, M. (2004). Learning, curriculum and employability in higher education. London: Routledge Falmer. Pp. 203-256. [CrossRef]

- Kochetova N.G., Stelmakh Ya. G., Kochetova T.N. Criteria and indicators of graduates' readiness for professional activity. 2020. Samara Journal of Science 9(2):244-247. [CrossRef]

- Koltsova E. A., Boyko S.A. Flipped Classroom Approach in Language Classes for Oil and Gas Engineering Master Students Integration of Engineering Education and the Humanities: Global Intercultural Perspectives. IEEHGIP 2022. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. 2022, 449, pp. 207-215. [CrossRef]

- Kretschmann, J., Plien, M., Nguyen, T.H.N., Rudakov, M.L. (2020). Effective capacity building by empowerment teaching in the field of occupational safety and health management in mining. Journal of Mining Institute. 242: 248-256. [CrossRef]

- Lamri, J., & Lubart, T. 2023. Reconciling Hard Skills and Soft Skills in a Common Framework: The Generic Skills Component Approach. Journal of Intelligence 11: 107. [CrossRef]

- Litvinenko, V.S., Petrov, E.I., Vasilevskaya, D.V., Yakovenko, A.V., Naumov, I.A., Ratnikov, M.A. (2023). Assessment of the role of the state in the management of mineral resources. Journal of Mining Institute. 259: 95-111. [CrossRef]

- Mallough, S., & Kleiner, B. H. (2001). How to determine employability and wage earning capacity? Management Research News, 24(3/4), 118–122. [CrossRef]

- Matrokhina, K.V., Trofimets, V.Y., Mazakov, E.B., Makhovikov, A.B., Khaykin, M.M. (2023). Development of methodology for scenario analysis of investment projects of enterprises of the mineral resource complex. Journal of Mining Institute. 259: 112-124. [CrossRef]

- Mazalin, K., & Parmac Kovacic, M. (2015). Determinants of higher education students' self-perceived employability. Drustvena Istrazivanja, 24(4), 509–529. [CrossRef]

- Mikeshin, 2022 – Mikeshin, M.I. (2022). Technoscience, education and philosophy. GORNYI ZHURNAL. 11: 78-83. [CrossRef]

- Mwita, K.M., Kinunda, S., Obwolo, S., Mwilongo, N. H. (2023) Soft skills development in higher education institutions: students’ perceived role of universities and students’ self-initiatives in bridging the soft skills gap. Research in Business & Social Science. Vol. 12 (3) ISSN: 2147-4478. [CrossRef]

- Pegg, A., Waldock, J., Hendy-Isaac, S. and Lawton, R. (2012), Pedagogy for employability, Higher Education Academy, York, England.

- Pereira, E.T., Villas-Boas, M., Rebelo, C.C. Does Entrepreneurship and Innovative Education Matter to Increase Employability Skills? Chapter 13 In book: Global Considerations in Entrepreneurship Education and Training. 2018. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331390267_Does_Entrepreneurship_and_Innovative_Education_Matter_to_Increase_Employability_Skills.

- Petruzziello, G., Chiesa, R., & Mariani, M. G. (2022). The Storm Doesn’t Touch me!—The Role of Perceived Employability of Students and Graduates in the Pandemic Era. Sustainability, 14(7), 4303. [CrossRef]

- Pintrich, P. R. (2002). The Role of Metacognitive Knowledge in Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 219–225. [CrossRef]

- Pitan, O. S., & Muller, C. (2020). Students' self-perceived employability (SPE): Main effects and interactions of gender and field of study. Higher Education, Skills and Work-based Learning, 10(2), 355–368. [CrossRef]

- Porfeli, E.J., Savickas, M.L. Career Adapt-Abilities Scale –USA form: psychometric properties and relation to vocational identity // Journal of Vocational Behavior. 2012. Vol. 80. Pp. 748–753. Пинтр. [CrossRef]

- Ramisetty, J., Desai, K., Ramisetty-Mikler, S. Measurement of Employability Skills and Job Readiness Perception of Post-graduate Management students: Results from A Pilot Study. July 2017. International Journal of Management and Social Sciences 0508(Vol.05 Issue-08,):82-94. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320735657_Measurement_of_Employability_Skills_and_Job_Readiness_Perception_of_Post-graduate_Management_students_Results_from_A_Pilot_Study [accessed Sep 22 2024].

- Rothwell, A., Arnold, J. (2007), "Self-perceived employability: development and validation of a scale", Personnel Review, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 23-41. [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, A., Jewell, S., & Hardie, M. (2009). Self-perceived employability: Investigating the responses of post-graduate students. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75, 152–161. [CrossRef]

- Sanders, J. & De Grip, A. (2004) Training, task flexibility & employability of low-skilled workers. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, 25(1), pp. 73-89. [CrossRef]

- Skornyakova, E.R., Vinogradova, E.V. (2022). Fostering engineering students’ competences development through lexical aspect acquisition model. International Journal of Engineering Pedagogy. 12(6): 100-114. [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J. & Knowles, V. (2000). Graduate recruitment and selection practices in small businesses.Career Development International, 5 (1), 21-38. [CrossRef]

- Sveshnikova, S.A., Skornyakova, E.R., Troitskaya, M.A., Rogova, I.S. (2022). Development of Engineering Studens' Motivation and Independent Learning Skills. European Journal of Contemporary Education. 11(2): 555-569. [CrossRef]

- Syrkov A.G., Makhovikov A. B., Tomaev V. V., Taraban V. V.. Priority in the field of nanotechnology of the Mining University in St. Petersburg - a modern center for the development of new nanostructured metallic materials. Tsvetnye Metally. 2023, 8. Pp. 5-13. [CrossRef]

- The Economic Times, 2023. Jun 01. Six must-have soft skills for freshers in 2023 by Riya Tandon. Available from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/jobs/fresher/six-must-have-soft-skills-for-freshers-in-2023/articleshow/100518650.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst [accessed Dec. 26 2024].

- Van Horne, C.; Rakedzon, T. Teamwork Made in China: Soft Skill Development with a Side of Friendship in the STEM Classroom. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 248. [CrossRef]

- Van der Vleuten, Cees, Valerie van den Eertwegh, and Esther Giroldi, 2019. Assessment of communication skills. Patient Education and Counseling 102: 2110–13. [CrossRef]

- Vanhercke, D.; De Cuyper, N.; Peeters, E.; De Witte, H. Defining Perceived Employability: A Psychological Approach. Pers. Rev. 2014, 43, 592–605. [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R., Sánchez-Queija, M.I., Rothwell, A., & Parra, Á. (2018). Self-perceived employability in Spain. Education + Training, 60(3). Pp. 226–237. [CrossRef]

- Varlakova, E.V., Bugreeva, E.A., Maevskaya, A.Y., Borisova, Y.V. (2023). Instructional Design of an Integrative Online Business English Course for Master’s. Education sciences. 13(1). Pp. 41-54. [CrossRef]

- Wenjing L., & Liu, J. 2021. Soft skills, hard skills: What matters most? Evidence from job postings. Applied Energy 300: 117307. [CrossRef]

- Yorke, M. & Knight, P. (2007). Evidence-informed pedagogy and the enhancement of student employability. Teaching in Higher Education, 12(2), 157-170. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L, Li, W, Zhang, H. Career Adaptability as a Strategy to Improve Sustainable Employment: A Proactive Personality Perspective. Sustainability. 2022; 14(19):12889. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Feng, Y.; Jiang, X.How Does Forgone Identity DwellingFoster Perceived Employability: ASelf-Regulatory Perspective.Sustainability 2024, 16, 9614.(PDF) How Does Forgone Identity Dwelling Foster Perceived Employability: A Self-Regulatory Perspective. [CrossRef]

- Zyberaj, J., Seibel, S., Schowalter, A. F., Pötz, L., Richter-Killenberg, S., & Volmer, J. (2022). Developing Sustainable Careers during a Pandemic: The Role of Psychological Capital and Career Adaptability. Sustainability, 14(5), 3105. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).