1. Introduction

At present, quantum technologies are gaining momentum in multidisciplinary fields and is one of secure technologies based on unconditional security of quantum postulates which is different from its classical counterpart where security is measured in terms of computational complexity. Various security tests have been performed by researchers under different realistic conditions and further concluded that performance of quantum cryptography systems also depend on the source characteristics e.g., single photon sources or entangled [

6,

12,

23,

59]. In 1992, the first implementation of QKD was proposed, and with time further improvements were accomplished in [

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

34,

59]. In the current industrial revolution, quantum technologies are being deployed in a number of applications [

39,

40,

41]. Nowadays, specialty optical fibers are available in the market, which offers very low losses in the range from 0.15 dB/km to 0.17 dB/km at the third telecom window i.e., 1550 nm [

47,

48]. This 1550 nm wavelength is the best suitable telecom wavelength as compared to 1310 nm; the reason being having less attenuation losses as compared to 1310 nm for real field practical QKD applications. Here, we deploy frequency up-conversion method [

22] to ensure the optimum detection of single-photons at 1550 nm. As per the literature, silicon-APD is the best candidate for such applications at telecom wavelengths which offers many significant advantages [

19,

34,

35,

36,

37,

46]. As the technological advancements and improvement in the optical fiber manufacturing, we are deploying speciality fibers, (ultra-low loss fibers [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

47,

48]) in the current research work.We analyze the relation between produced error rate and communication rate with distance for the QKD protocols (Bennett-Brassard 1984 (BB84) and Bennett-Brassard-Mermin 1992 (BBM92)). Further, we investigate the security of BBM92 and BB84 QKD protocols under various attacks.

2. Detectors in Telecom Range

2.1. Single Photon Detectors

An effective method for efficient detection of single photons at 1550 nm is frequency up-conversion [

19]. InGaAs/InP avalanche photodiodes have low quantum efficiencies and suffer from after-pulse problems generated by trapped charge carriers, which are responsible for generating large-dark count rates. Hence, the generated high dark counts further work as an obstacle in gated mode operation. At this stage, an avalanche photo detector is allowed to rise above the breakdown threshold for a few nanoseconds, which indicates low dark count probabilities with greater efficiency for light detection. Further, it is returned to below breakdown for enough time for any trapped charge carrier to leak away. For example,for a given trapping lifetime in the order of microseconds, this stage permits mechanism at mega hertz rates, where the after pulse probability is minimized by the ratio of gate width to the time gap between gates. This gate frequency is highly important in many QKD (Quantum Key distribution) applications, which decides the signal pulse repetition rate, and hence restricts the achievable communication rate. Dark count rate is decided by the gate width, restricted by the semiconductor material’s response time.

In

Figure 1 and

Figure 2, InGaAs/ InP as an avalanche photodiode was deployed to test its performance in many optical fiber based quantum key distribution applications where its experimental feasibility was investigated to perform as a single photon detector [

15,

16,

18,

21,

34]. During these experiments, it was observed that this single photon detector has many limitations and performs with poor efficiency due to the existing problems such as severe after pulse probabilities [

17], high background count rates, low value of quantum efficiency, high value of dark count rate. Hence, it is not the right candidate to perform well in gated-mode operation due to the generated trapped charge carriers. It is specifically desired to operate single photon detectors above the breakdown threshold in gated mode for a short duration so that high photon detection events can be achieved where less dark counts exist. Also, in a short span of time, it regains its original state, attains state below breakdown for enough time for trapped charge carriers to leak away. This gated mode operation where single photon detectors work at mega-hertz rates and achievable trapping lifetime exists in microsecond duration. Hence, it is after pulse probability which is reduced at this point by the amount of gate width to the time separation between gates. It is the gate frequency which decides the pulse repetition rate and affects the final communication rate in most of the quantum key distribution (QKD) protocols. The generation rate of dark counts depends on the semiconductor material’s response time which further decides the QKD communication distance, and moreover these are affected by gate width. The value of dark counts in the order of

is achieved with 1-2 ns gate width at the value of ∼ 1 MHz pulse repetition frequency.

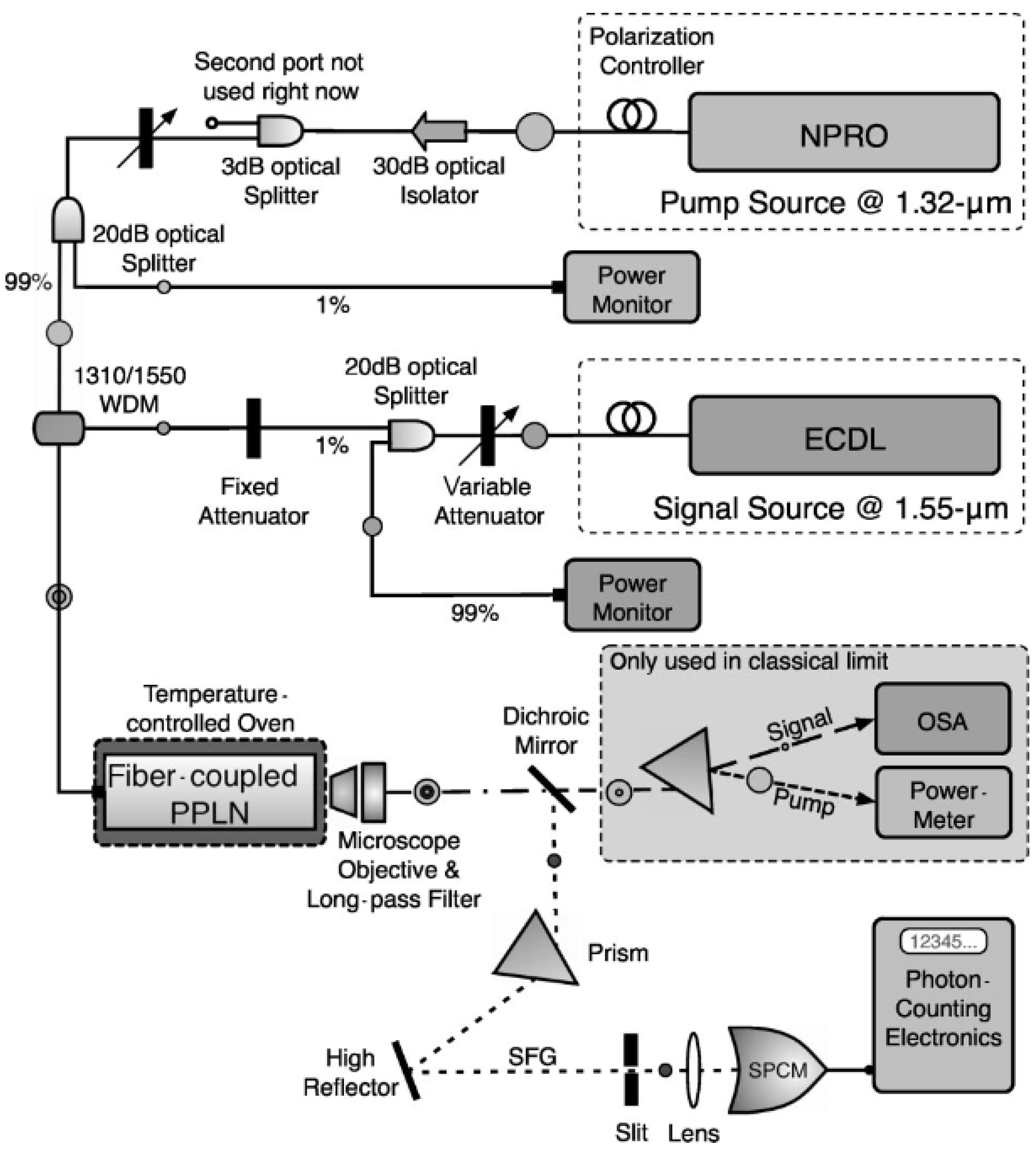

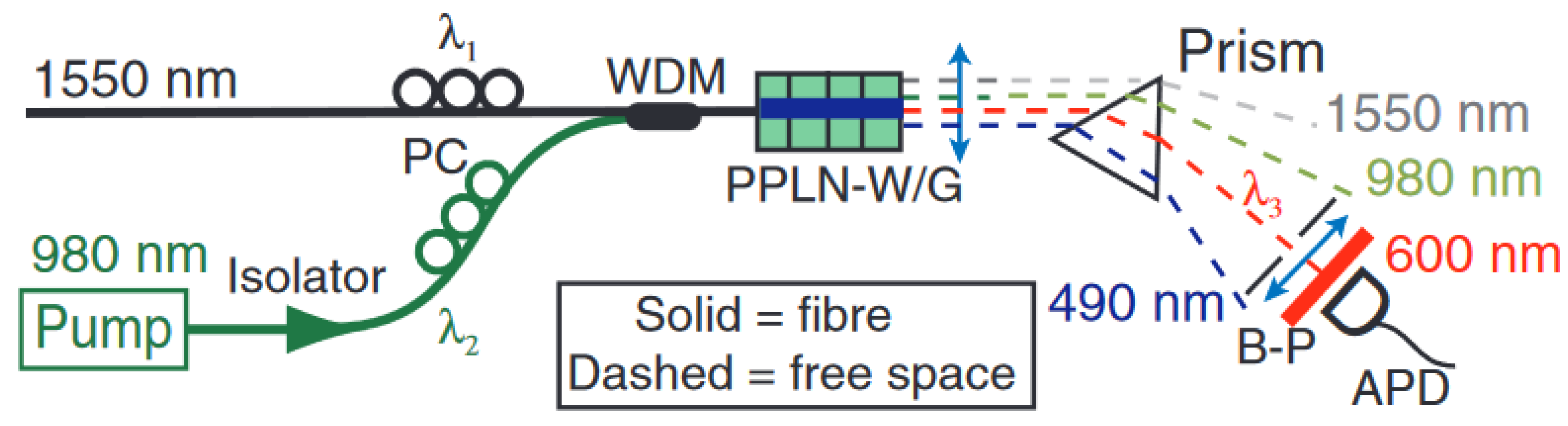

2.2. Photon Detection Using Frequency Up-Conversion

In the sum frequency generation method [

22], periodically poled lithium niobate (PPLN) is used; a single photon at 1550 nm interacts with a strong pump at 1320 nm. This is the method which is deployed in 1550 nm up-conversion for single photon detection [

19]. A signal of very high conversion efficiency is converted to an output of 700 nm sum-frequency with the help of PPLN waveguide. Due to the presence of guided wave structure in PPLN, this conversion becomes possible, where longer interaction length, tight mode confinement and quasi-phase-matching patterns perform this mechanism, as shown in

Figure 1 and

Figure 4. Hence the converted photons are detected by silicon APD using these operations. In most of the QKD industrial applications, out of these two detectors, Si-APD is one of the preferred detectors. It has some important merits over InGaAs/ InP APDs such as a timing resolution as low as (40 ns) [

37], low dead time (45 ns), low value of dark-count rates, low value of after-pulse, at near infrared regions [

34]. These characteristics of Si-APD makes it a suitable candidate over InGaAs/ InP APDs for real field quantum key distribution with high stability count rate of 20 MHz [

34,

35,

37] and better timing accuracy [

31,

32,

34]. In real-field QKD applications, high communication rate is achieved with the use of Si-APD in Geiger mode, which has low after pulse probability. This Geiger mode is also known as nongated mode of operation of Si-APD. One added advantage of low dead time (45 ns) of Si-APD helps in achieving improved secure key generation rate. During this period, a larger photon flux saturates the set-up , no response is obtained from the photodiode from successive events. As per the standard theory of up-conversion process, the dark count rate

and quantum efficiency

depend on the parameter

p ( pump power) [

19]. When phase-matching and sufficient pump power available in the said waveguide, maximum (100%) photon conversion is achieved which results in getting high quantum efficiency of Si-APD i.e., 0.46. The fitting curve is drawn with the help of following equations, which is based on three-wave interactions coupled mode theory

where

p is in mW, and values of

, and

are 0.465, and 79.75, respectively.

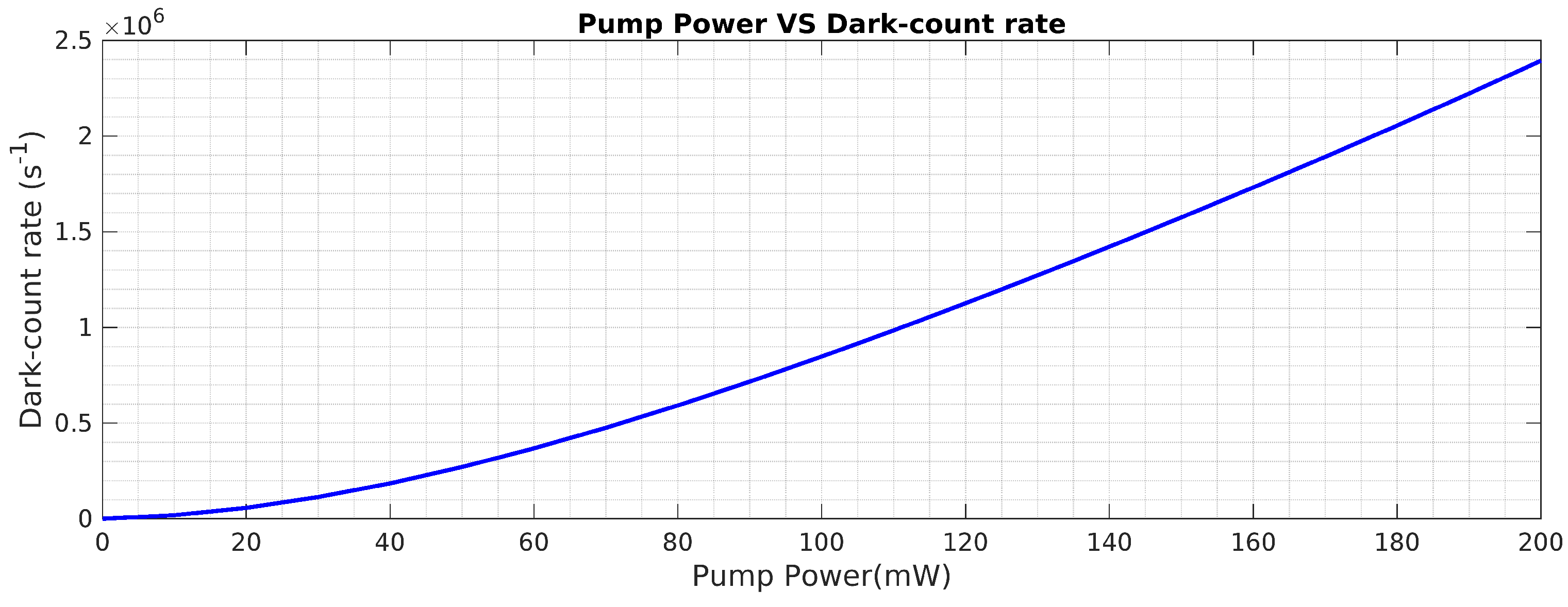

Here we discuss how the dark counts are controlled by a nonlinear process. First of all, the fiber and phonons of the PPLN disperse the pump photons using spontaneous Raman scattering. Hence, photon generation is achieved at 1550 nm signal wavelength with proper setting of pump power. Further, dark counts are produced due to a combination of pump photons and noise photons in the waveguide through phase-matched sum-frequency generation methods. From

Figure 3, we can observe the quadratic dependency of dark counts and pump power. The below equation produces an exact polynomial fitting curve

where the values of b0, b1, b2, b3, and b4 are 50, 826.4, 110.3, -0.403, and 0.00065, respectively.

Figure 3.

Effect of pump power on produced dark counts.

Figure 3.

Effect of pump power on produced dark counts.

Figure 4.

Experimental Setup for Single Photon Detection at Telecom Wavelength [

19].

Figure 4.

Experimental Setup for Single Photon Detection at Telecom Wavelength [

19].

The other sources responsible for producing dark counts are up-converted noise signal photons and parametric fluorescence processes [

47,

50]. According to the described process and spontaneous Raman scattering extra dark counts are generated. The reason for such an effect in the frequency conversion detector , the absorption of 8.9

m idler photons which are absorbed in lithium niobate. Hence in such fluorescence processes the produced dark counts further limits the QKD performance parameter. To overcome the effects of these unwanted dark counts, the signal wavelengths and pump [

18] must be interchanged. All these operations happen within the waveguide and thermal processes of excited vibrational states generate anti-Stokes scattering gain [

18].

It is the waveguide bandwidth which has to be tuned properly to adjust both the generated noise photons and the number of dark counts. For a detector, the term

is written as

, where

is the dark count per mode. From the principle of communication systems,

B is the bit rate defined for an ideal communication system, having bandwidth

B with a matched filter, where the term

is defined for an ideal communication system. The term,

is the dark count per time window, which is equal to

Hz and is one of the QKD performance deciding factors. Here the dark count per time window does not depend on the bit rate

B which is the optimum filtering case. In the gated mode of InGaAs/ InP APD, the term

is the dark-count rate of the InGaAs/ InP APD,

is gate width,

is the dark counts per gate calculated by the expression

. All the required parameters like dark-counts are mentioned in

Table 1 . The bit rate is

B and

is the waveguide bandwidth. The value of

is deployed in InGaAs/ InP APD.

The expression for the normalized noise equivalent power (NEP) is written as , where and . All these mathematical expressions are used in the up-conversion process. The term Hz is calculated based on the detector’s operating point. In the same context, for an up-converter detector, and for the value of bandwidth GHz, the optimum value of is . All these are the important exercises prior to performing any implementation of QKD in a real field scenario.

The current research work deals with the effects of the waveguide bandwidth on the produced dark counts in Si-APD and also pump power which affects its characteristics in frequency up converted quantum communication systems at telecommunication wavelength and decides the detection performance.

3. BB84 Quantum Key Distribution Protocol

The randomly modulated single photons in two non orthogonal bases are transmitted from Alice to Bob in a BB84 (Bennett-Brassard 1984) protocol. The received photon polarization states, at Bob’s end, are measured in a random polarization basis. Further, it is required to analyze the effects of the hybrid attacks such as intercept-resend, individual attack and photon-number splitting (PNS) attacks [

6]. Under these attacks the expression for the secure communication rate is written as

here, the sifting parameter is

and the term

is defined as the repetition rate of the transmission

Now, for the analysis of security of BB84 protocol, we consider hybrid attacks e.g., Intercept-resend attack and Beam-splitter attack

To calculate the key generation rate, we need to compute the privacy amplification shrinking factor ( ), with respect to average collision probability ().

The transmitted photons after reaching at Bob’s side are detected with detection probability expressed as

where,

where the mean photon number per pulse is denoted by

, optical fiber loss coefficient is written as

with unit dB/km, detector quantum efficiency is written by

, losses in the receiver unit is

, communication link by

L with unit in km, and dark counts per measurement time window by

d. Here four detectors are deployed in the detection unit of Bob. The mean photon number,

, is the most contributing parameter which has to optimize and therefore for an ideal case

, but in case of Poisson photon source this parameter has to be tuned to obtain the optimum results [

44].

where, baseline system error rates and error rate are represented by

b and

e, respectively.

Table 2 [

45] mentions values of

which are based on an error-correction algorithm.

The main shrinking factor

in privacy amplification is written as

where the average collision probability is represented by

and is used to count for the amount of Eve’s mutual information shared between Bob and Alice.

Further,

is expressed as

The fraction of single-photon states emitted from the source can be written as

where the probability of the multi-photon quantum states are denoted by the term

. The values of

or

= 0 are written for an ideal single photon source. In addition, photon emission probability in a Poisson source,

is written as

Here the photon number splitting (PNS) attack is performed by Eve to extract the information and computed by the term . To hide her presence, Eve performs quantum nondemolition measurements of the photon number in each pulse without any errors. As the source emits more than one photon, due to these multi photons, Eve copies one photon in a quantum memory and after Bob performs a basis announcement, Eve performs a delayed quantum measurement on the photon. Here in BB84 protocol, PNS attack limits the performance of the laser source. The expression is used to denote the loss in the secure communication rate with the distance, for low error rate and . In a different scenario, under the similar constraints, when the used source is an ideal single-photon source, it is analyzed that , i.e., the secure key rate starts decreasing only linearly with the increasing fiber distance.

Assuming that Eve has a quantum memory with infinitely long coherence time which is used for storing the intermediate information (basis measurements) transferred between Alice and Bob. In the case when Eve does not possess a quantum memory she has to apply polarization measurement with arbitrary random basis selection. Under such situation, Equation (

9) can be written as

There are other alternatives to make BB84 more robust against PNS attack such as deploying sifting procedure [

59] or introducing decoy states [

50,

54,

61]. Poisson source is deployed in BB84 protocol to compute the secure communication distance achieved. In addition to this, vacuum plus weak decoy state protocol [

54] will be used in the current research work.

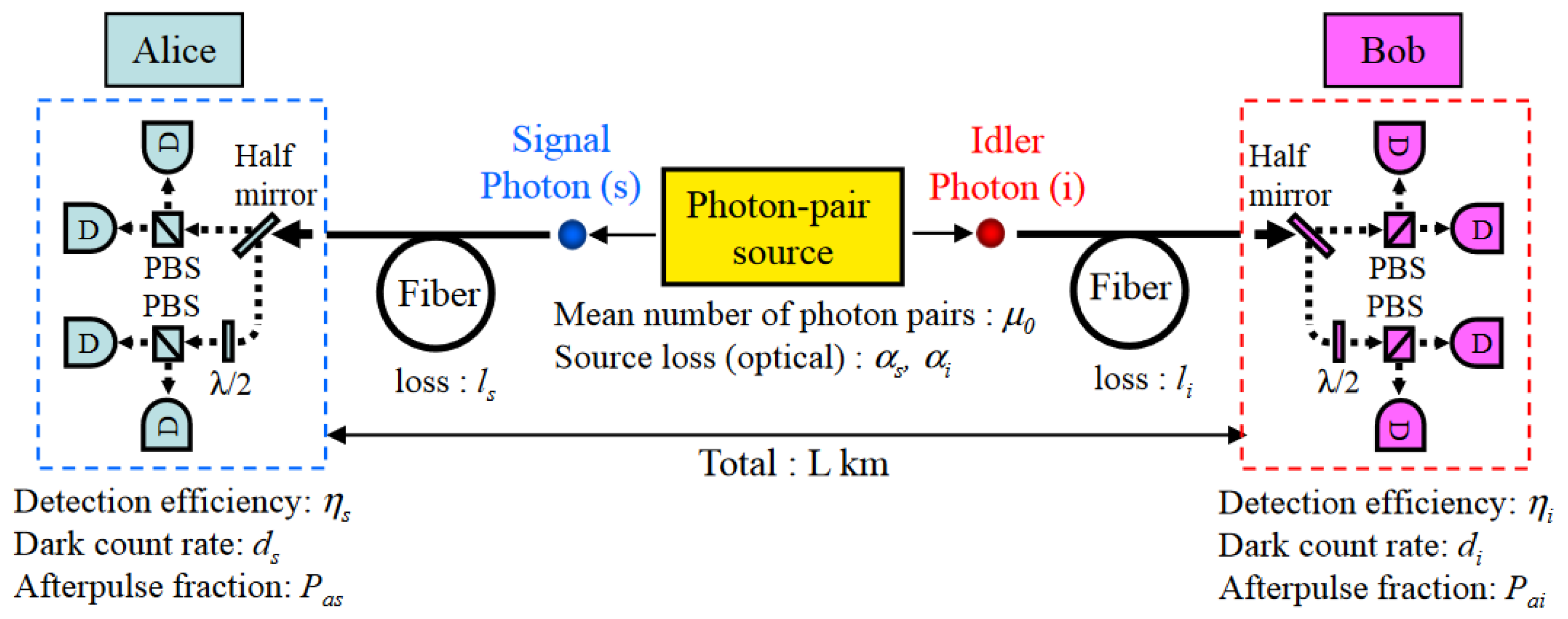

4. BBM92 Quantum Key Distribution Protocol

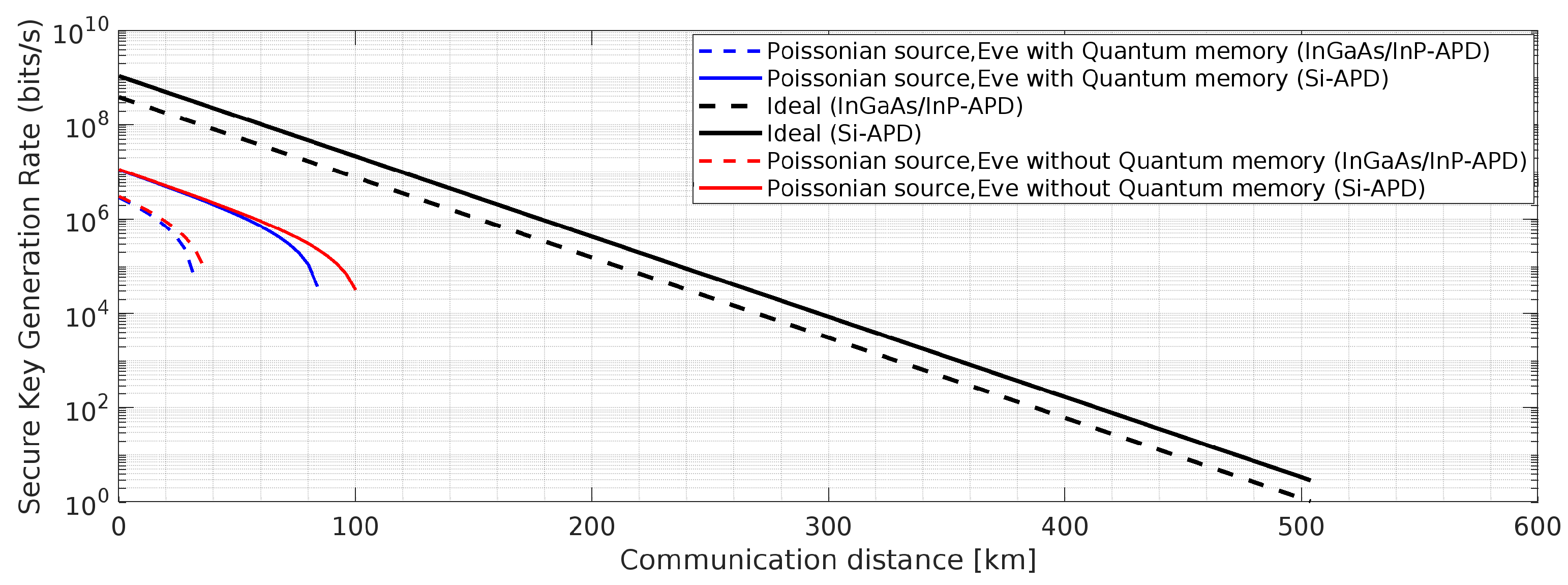

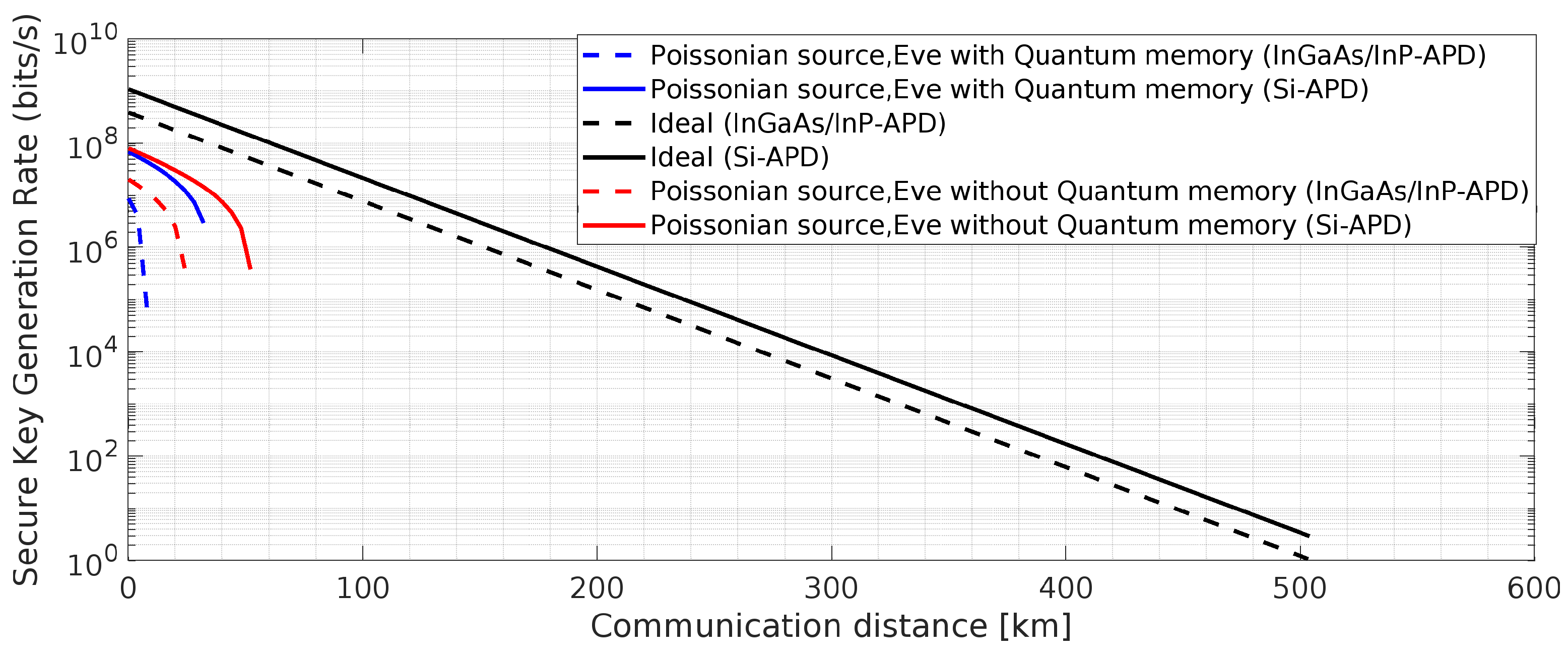

The two-photon variant of BB84 is the Bennett-Brassard-Mermin 1992 (BBM92) protocol. Alice and Bob each of them provide a photon of an entangled photon pair, as shown in

Figure 2, for which they perform the polarization state measurement in a randomly selected basis out of the two considered non-orthogonal bases. In [

12], it was mentioned that the BB84 with a single-photon source, i.e., with

and BBM92 protocol they both have the same average collision probability

. Now,

, the shrinking factor is written as

The above relation highlights about no analogy to a photon-number splitting attack in BBM92. As compared to BB84, BBM92 protocol is more robust against the attacks, less prone to errors generated by the dark counts, as highlighted by the simulated results in the

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20,

Figure 21,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23. One dark count cannot contribute to the errors in BBM92 protocol. Further, secure communication rate equation under the effect of individual attack is expressed as [

12]:

Now the expression for the probability of a coincidence between Bob and Alice is written as

Assuming that the photon source is located in between the two authentic communicating parties [

12]. Further the expressions,

, and

represent for false coincidence probability, and true coincidence probability, respectively and these are different expressions for a Poissonian entangled-photon source and a deterministic entangled-photon source.

(1) Expression for

for a deterministic entangled-photon source,

(2) Expression for

for a Poissonian entangled-photon source,

and

The description about the said parameters have been mentioned in the previous section. The term,

, depends on average photon-pair number per pulse, i.e., the nonlinear coefficient, the interaction time of the down-conversion process and the pump energy. In a Poissonian entangled-photon source, the said term is a free variable which needs to be optimized. Further, the error rate expression can be written as follows

In a single photon source based BB84 and BBM92 protocols with the conditions, and small error rates, the secure key generation rate decreases linearly with the optical fiber transmission used as a quantum channel. For a BBM92 QKD protocol, no quantum memory is required to attack and hence Equation [14] is alone computed by IR (intercept and resend) attack.

Probability to receive

n photon pairs in a particular pump pulse is expressed as

where

belongs to pump power of the laser used.

is the mean number of pairs per pump pulse

,

.

The parameter

depends on the average photon-pair number per pulse, i.e., the nonlinear coefficient, the pump energy, and the interaction time of the down-conversion process. There are some important considerations which affect the performance parameters. The measurement time window is affected by the timing jitter of the detectors. The dark counts are generated from either the thermal generation of a carrier in the sensitive part or the release of a carrier trapped by defects in the junction in the course of a previous avalanche. The latter type of dark count is known as an after pulse. In addition to this, to reduce the effects of after pulse probability, self differencing circuits are used which are made of coaxial cables of precise length, so that they match with the laser clock frequency. After pulse probability is an important factor to consider while improving the performance of any quantum communication system. After pulse probability is defined as the ratio of total after pulse counts to the photon counts. To overcome the effects of after pulse in gated mode operation by setting the interval of the time windows longer than the lifetime of the trapped carrier. To reduce the dark counts in the gated mode operation, which was generated due to after pulse effects, to eliminate those dark counts, we need to set the gate-off time longer than the lifetime of trapped carriers. The said lifetime is related to the gate-off time beyond which the dark count probability does not vary. It is also essential to set the gate repetition frequency below 1 MHz, so that the after pulse effects can be eliminated. Here we observe from the simulation results shown in the plots that the entanglement-based BBM92 protocol performs better than the single photon-based BB84 protocol, as highlighted by the simulated results in the

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20,

Figure 21,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23. The reason being is that the BBM92 is less vulnerable to the errors generated from dark counts, because only one dark count can’t contribute to errors in the said BBM92 protocol. To overcome the effects of after pulse, we can employ long dead time. Also, the effect of saturation present in Si-APD, is related to its dead time. This effect is apparent even for small losses in the fiber and also a concern for high bit rates.

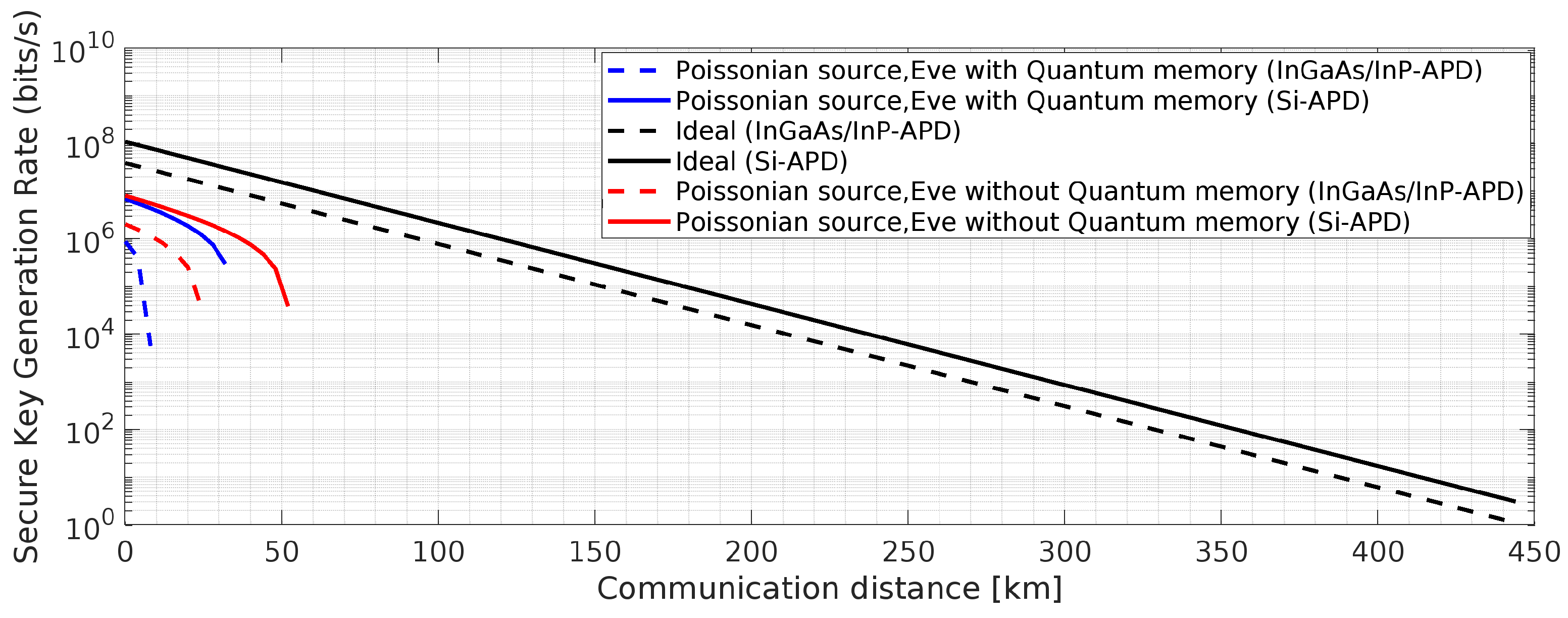

Figure 5.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 5.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

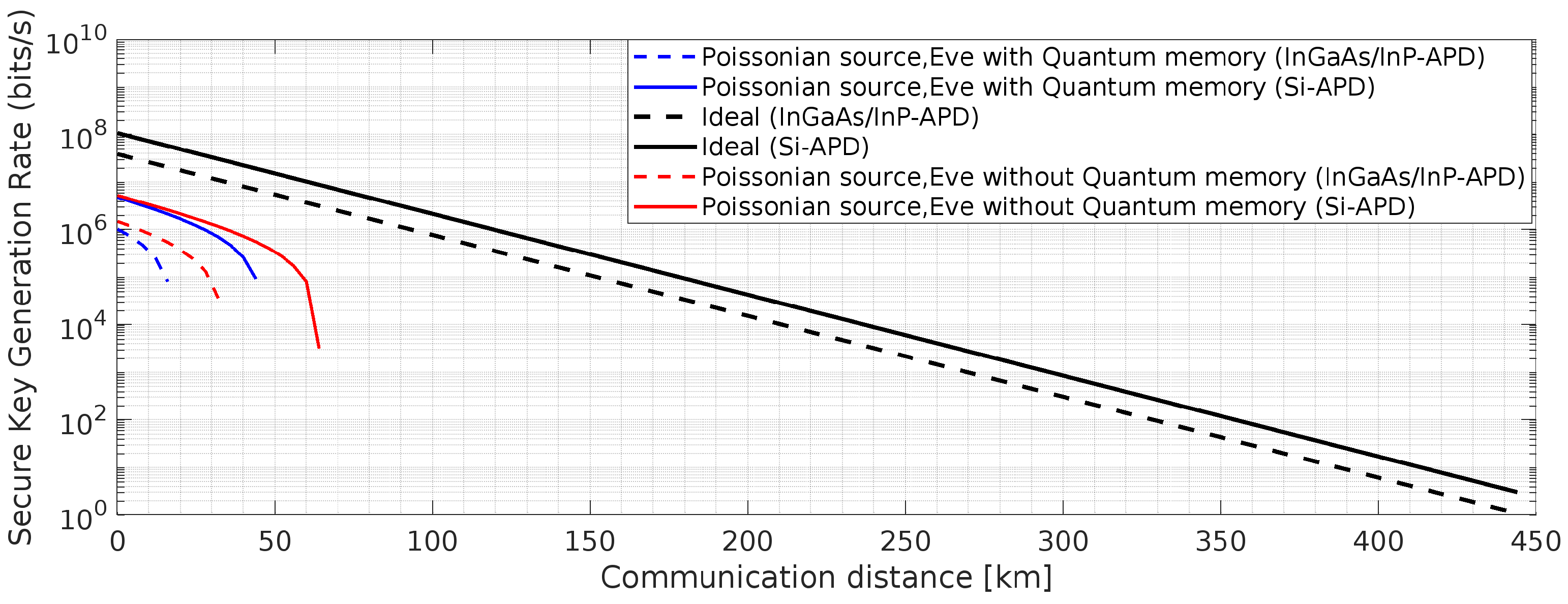

Figure 6.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 6.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

4.1. Beam-Splitter Attack

In the multi photon transmission process from Alice to Bob, Eve takes advantage of these multi-photons by intercepting and further making a copy of these coherent quantum states. In this process, a beam splitter with transmission

is used by Eavesdropper. In addition to this, in place of lossy fiber, Eve deploys a lossless fiber. To hide her Eavesdropping attempts, at Bob’s end, she also replaces inefficient detectors by the ideal detectors. Bob’s signal photon detection probability is represented by

which is the same as written in Eq. (5). At this stage, Eve makes efforts just to hide her presence by altering the beam-splitter transmission

to

Figure 7.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 7.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

To extract the meaningful information shared by Bob, Eve can use an interferometer of delay time .To compute the amount of measured information, we have to find out some important parameters. The detection probabilities in a given time frame are and , which are the values at Eve’s and Bob’s end , respectively. At the same time, the expression for the detection probability can be written as . As per the conditional probability, at a particular time, the probability value of the obtained information bits by an Eavesdropper when Bob has already detected that photon during that time frame can be expressed as . Here the probability value achieved by Eve is . This is the received probability by Eve in case she is not having a quantum memory with infinitely long coherence time. On the other side, The two authentic communicating parties, Alice and Bob, can disclose their outcomes with random delay, hence with a quantum memory with a long coherence time, Eve can steal the information. At this stage, instead of a beam splitter, an optical switch with an interferometer is deployed by Eve to extract the pulses for which differential phase information was already received by Bob. By introducing this strategy, Eve achieves enough information which is equal to . Following this strategy Eve gets an amount of information which is equal to , further, which is equal to or . No errors are introduced in the Beam-Splitter attack and remaining bit fractions can be expressed as follows

(i) When there is no quantum memory

(ii) When there is a quantum memory

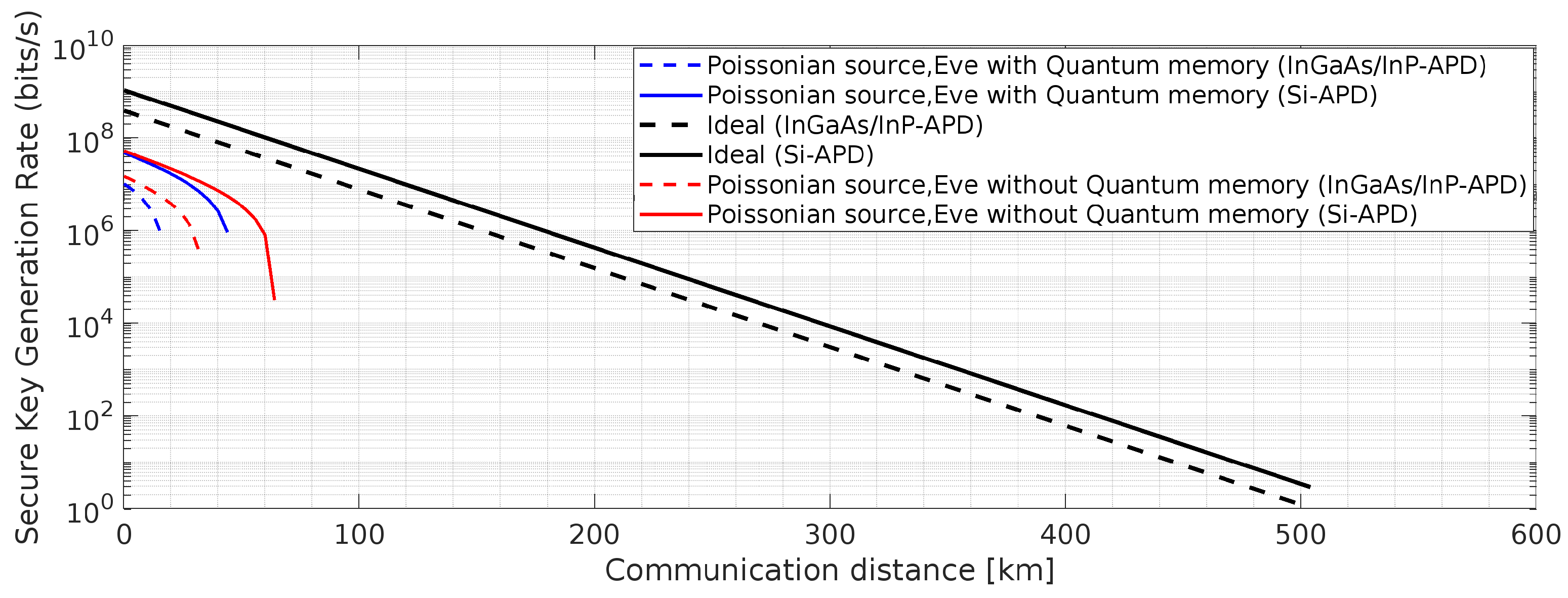

Figure 8.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 8.

BB84 QKD Protocol with one weak decoy state [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of one weak decoy state and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

4.2. Intercept-Resend Attack

In an another Eavesdropping strategy, the information carrying photons from Alice to Bob is attacked by the Eavesdropper known as Intercept-resend attack

Figure 9.

BB84 QKD Protocol: Effect of the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 9.

BB84 QKD Protocol: Effect of the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

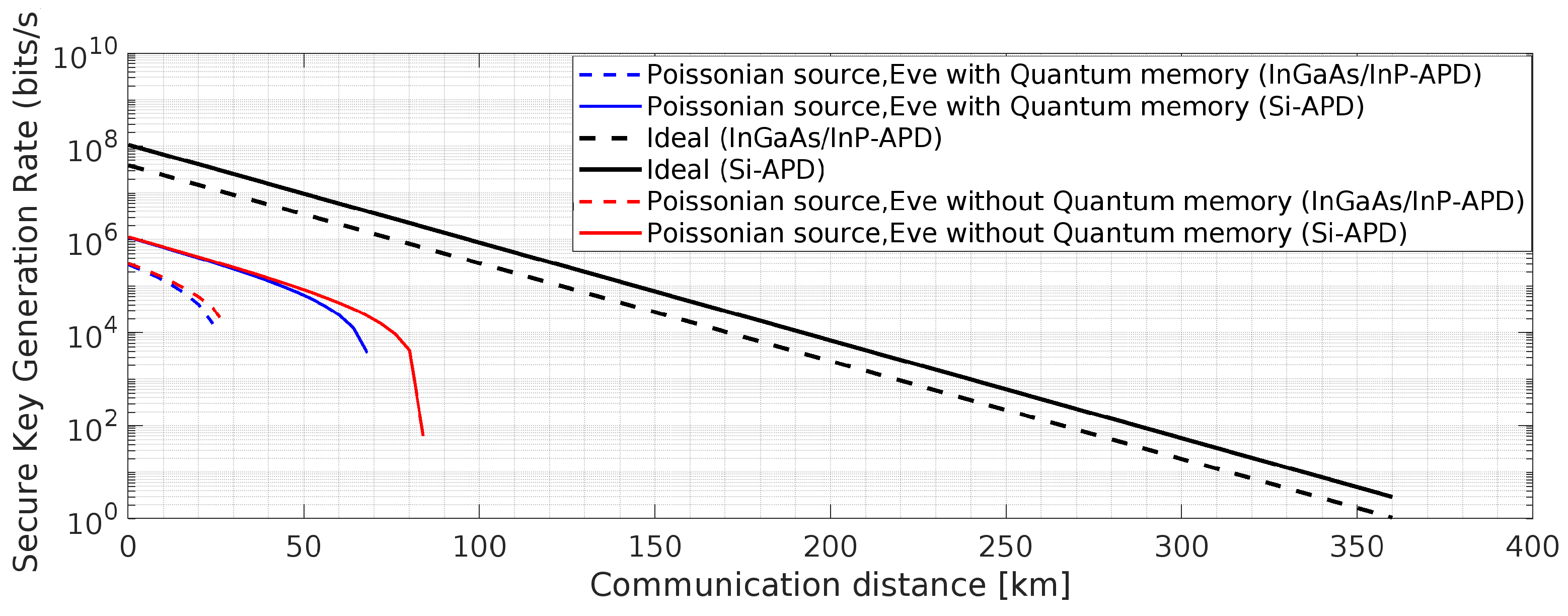

Figure 10.

BB84 QKD Protocol with PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) bound (

) [

24]: Effect of the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 10.

BB84 QKD Protocol with PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) bound (

) [

24]: Effect of the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Under intercept-resend and beam-splitter attacks, Eavesdropper is not familiar to

number of bits, further it is equal to

. Here, the expression for the privacy amplification shrinking factor is written as

Figure 11.

BB84 QKD Protocol: Effect of the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 11.

BB84 QKD Protocol: Effect of the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

The expression for the BB84-QKD secure key generation rate under intercept-resend and beam-splitter attacks is written as

The term

is referred to as transmission repetition rate. The expression for dark count probability,

is written as

Figure 12.

BB84 QKD Protocol with two weak decoy states [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of two weak decoy states and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 12.

BB84 QKD Protocol with two weak decoy states [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of two weak decoy states and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 13.

BB84 QKD Protocol with two weak decoy states [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of two weak decoy states and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 13.

BB84 QKD Protocol with two weak decoy states [

50,

54,

61]: Effects of two weak decoy states and the said attacks on Secure key rate,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

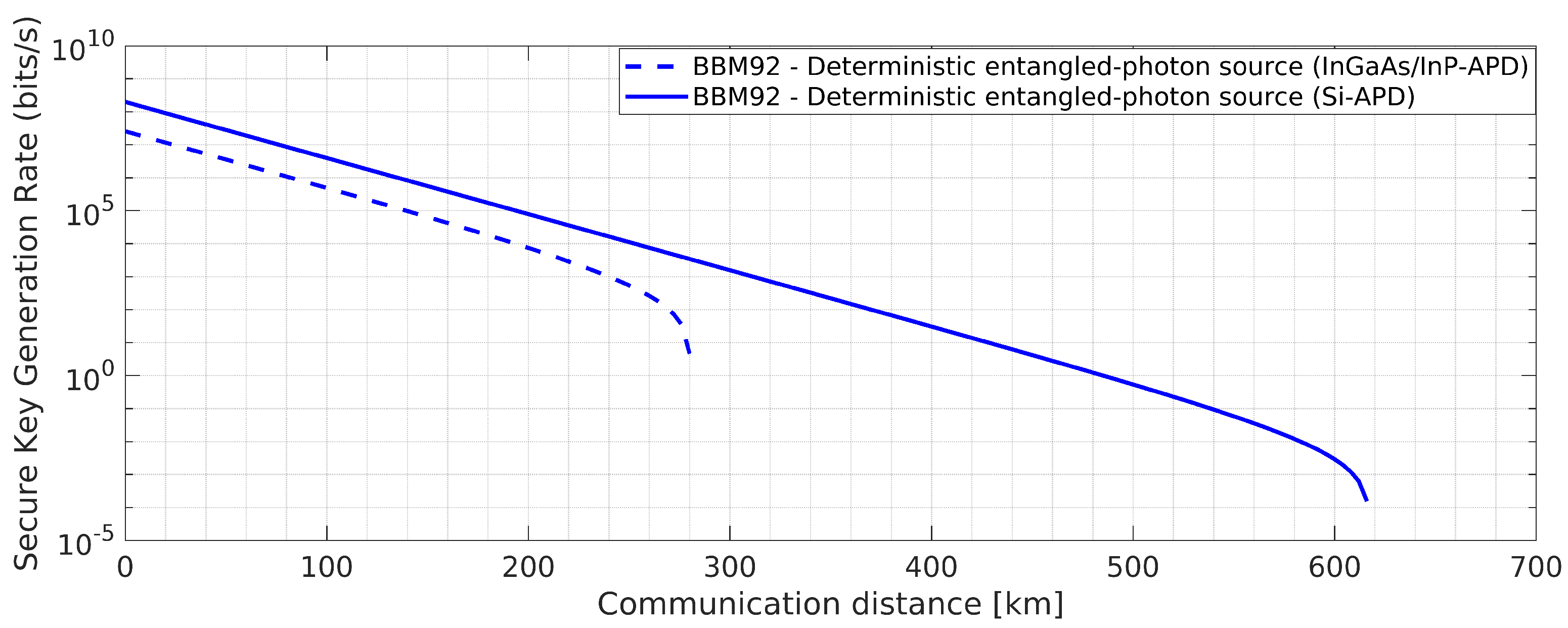

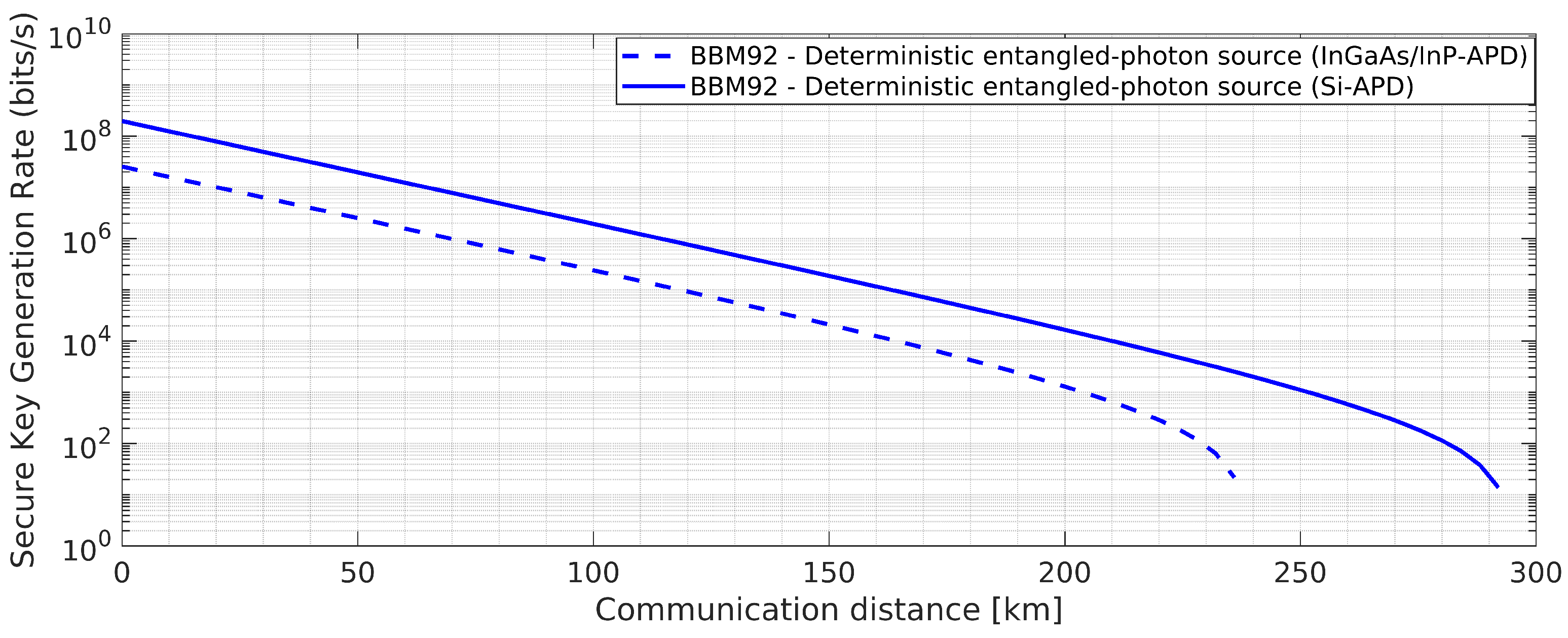

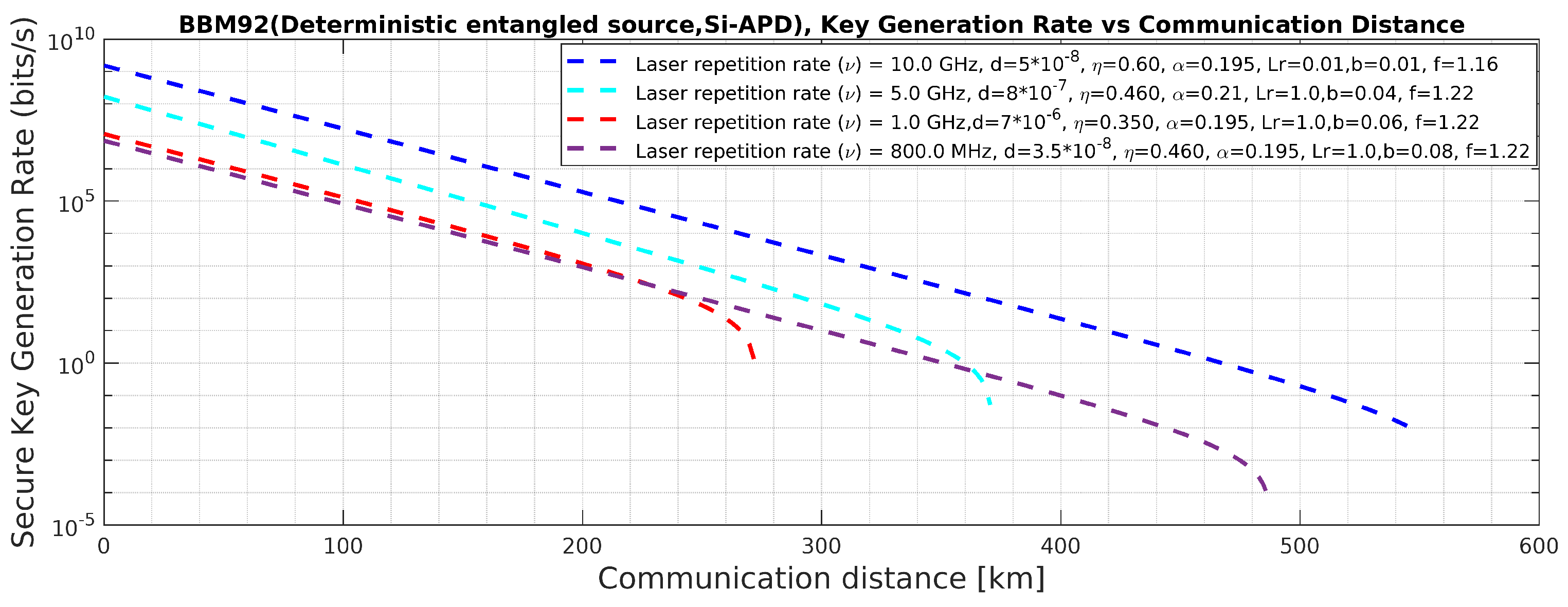

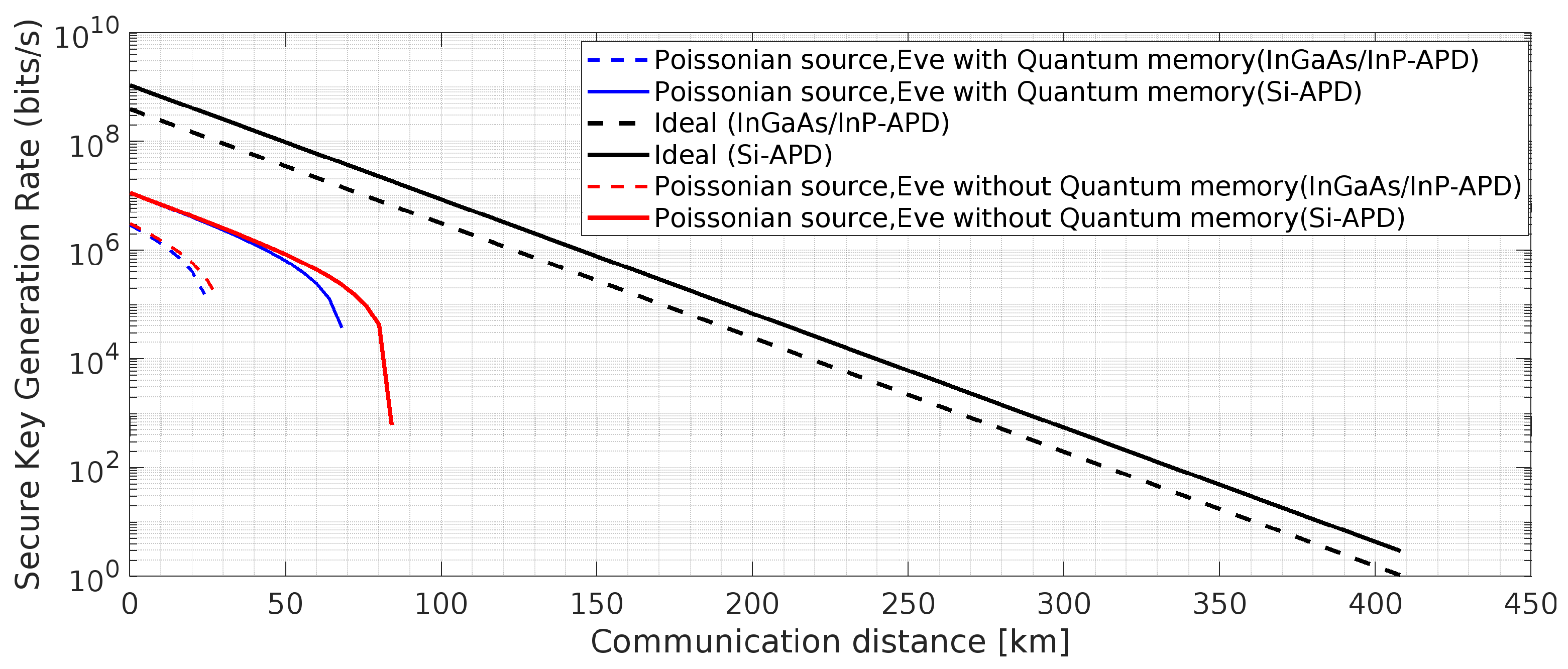

Figure 14.

BBM92 QKD Protocol: Effects of the said attacks on Secure key generation,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 14.

BBM92 QKD Protocol: Effects of the said attacks on Secure key generation,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 15.

BBM92 QKD Protocol: Effects of the said attacks on Secure key generation,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

Figure 15.

BBM92 QKD Protocol: Effects of the said attacks on Secure key generation,

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

;

. InGaAs-APD and Si-APD are represented by the subscripts 1 and 2, respectively [

23].

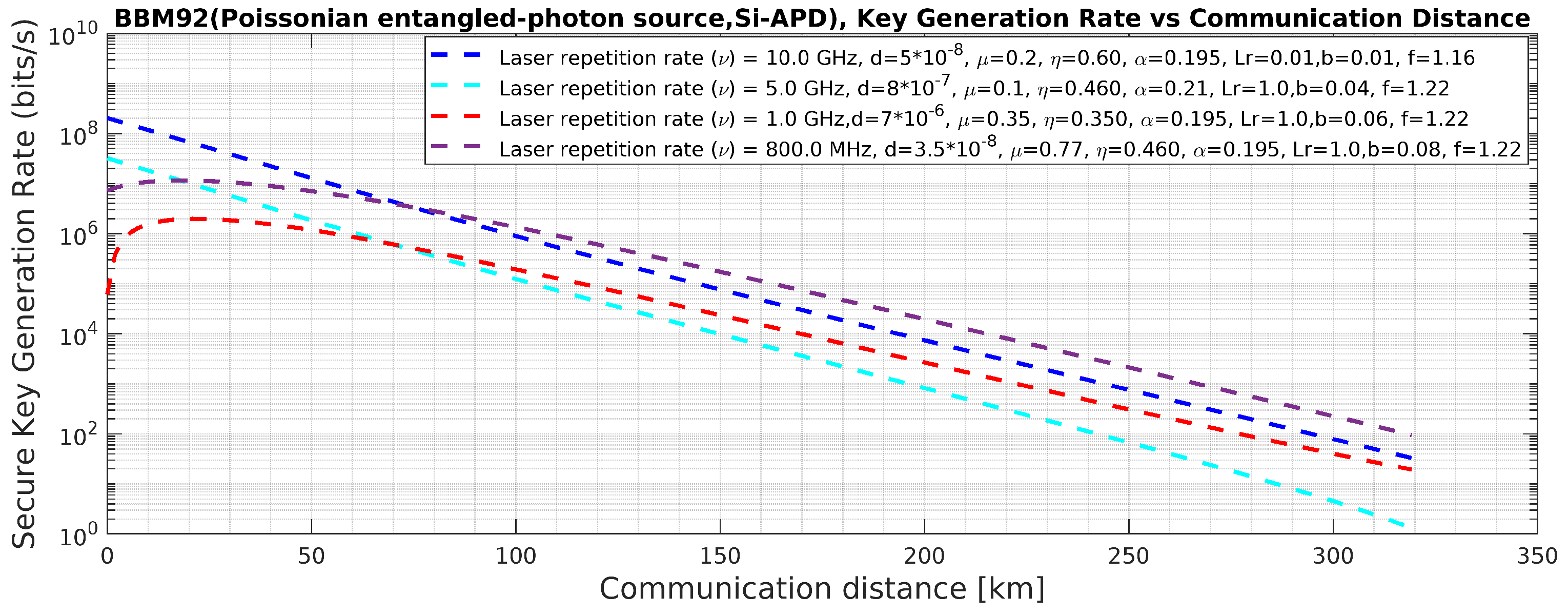

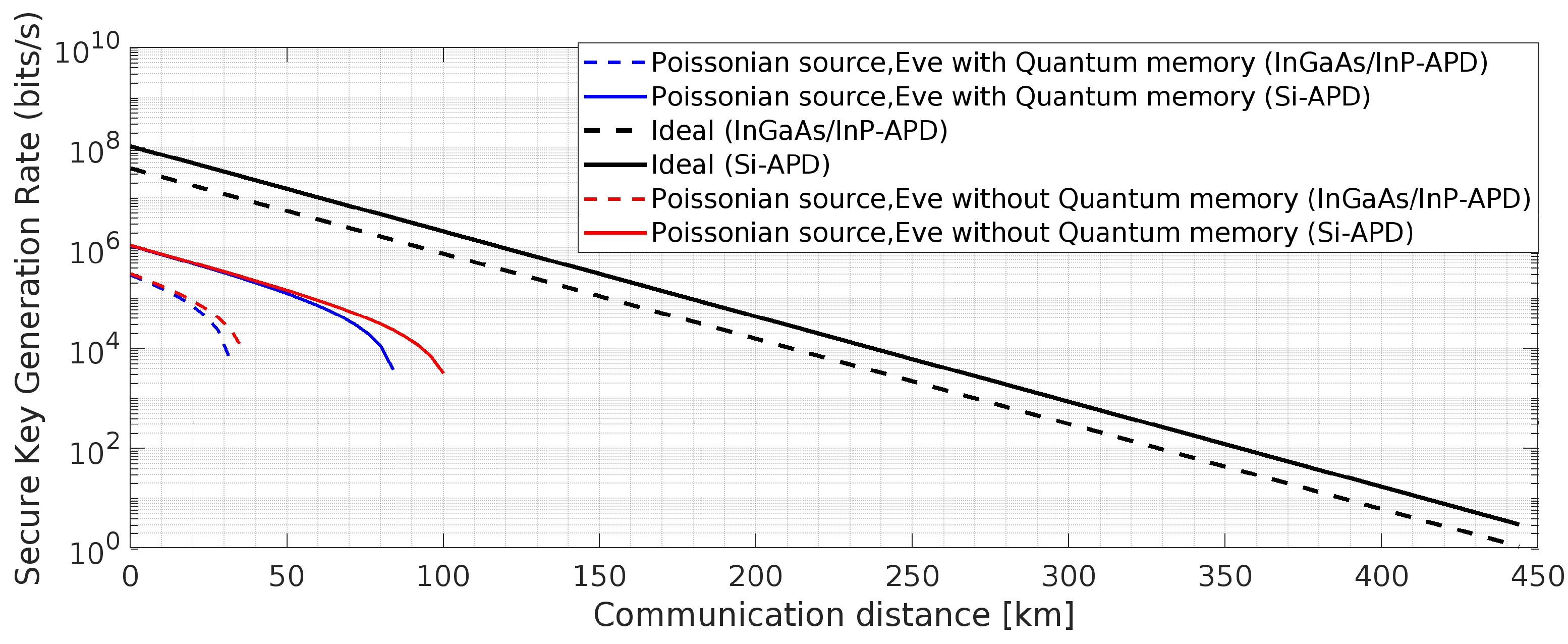

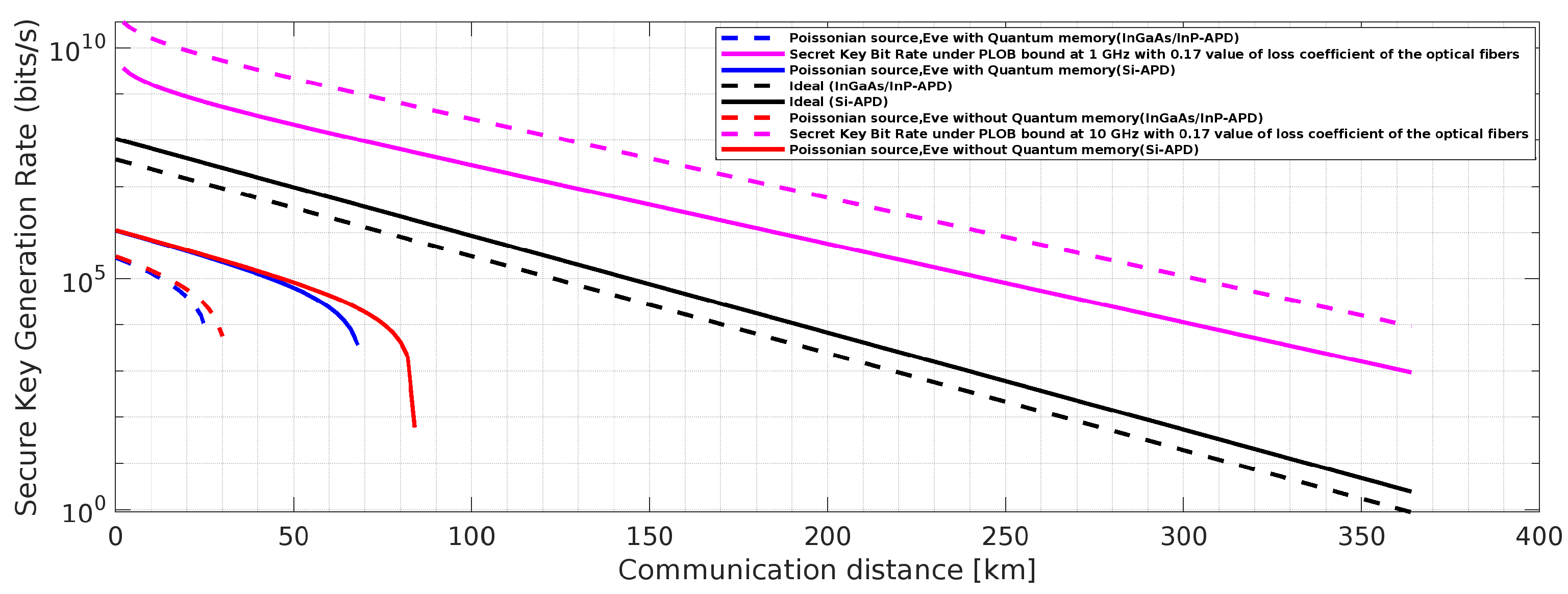

Figure 16.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 16.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

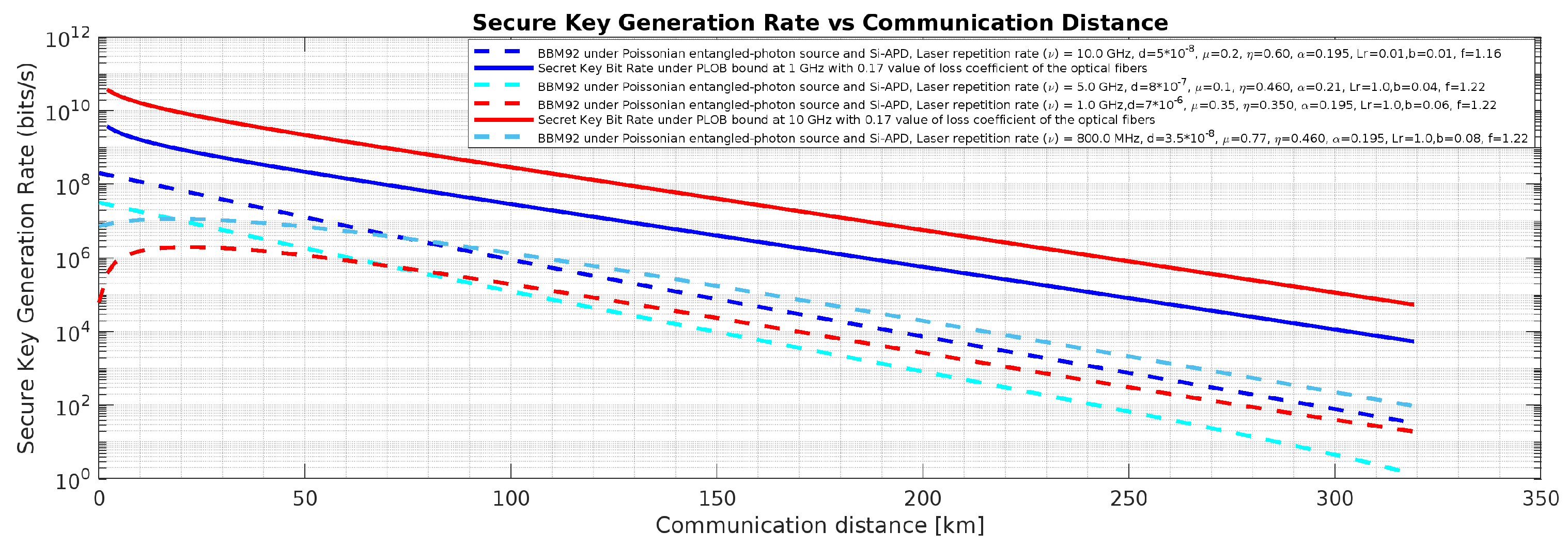

Figure 17.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) bound ((

)) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 17.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) bound ((

)) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

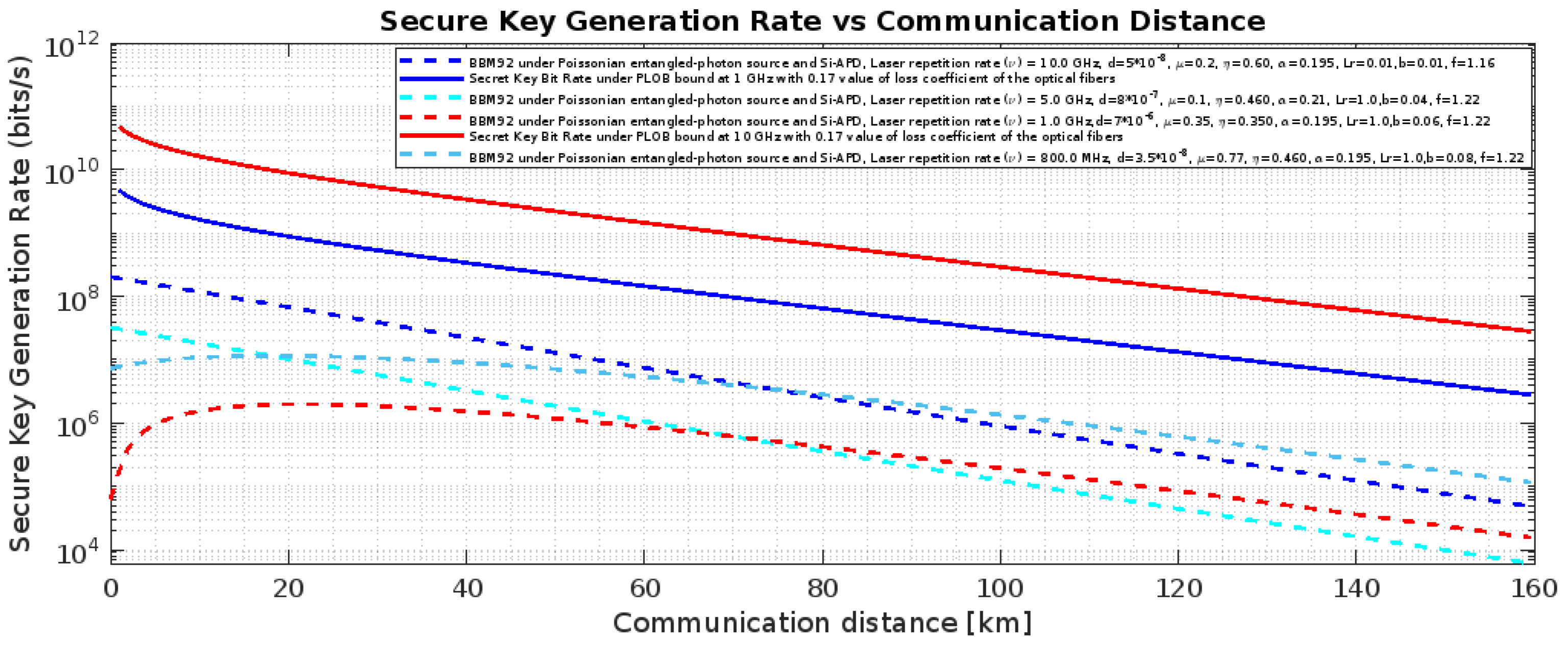

Figure 18.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source placed in the middle and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) bound ((

)) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 18.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source placed in the middle and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) bound ((

)) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 19.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 19.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

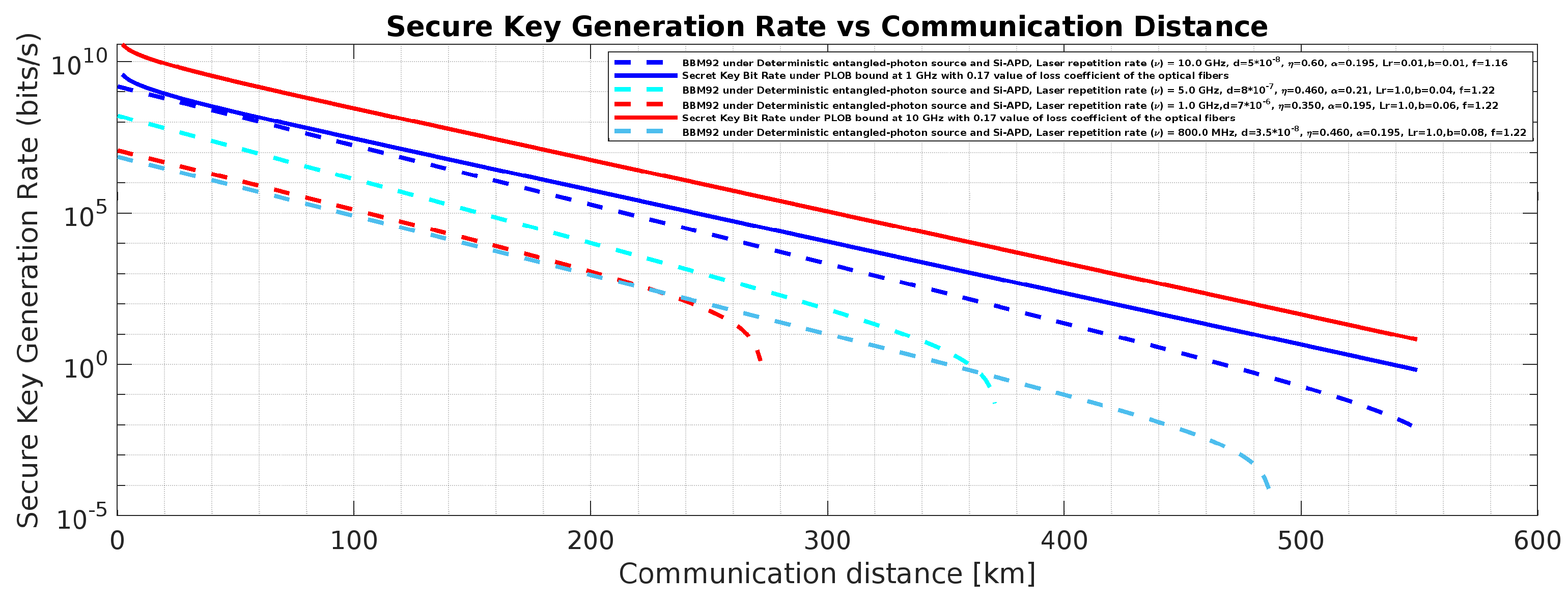

Figure 20.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) Bound (

) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 20.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) Bound (

) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

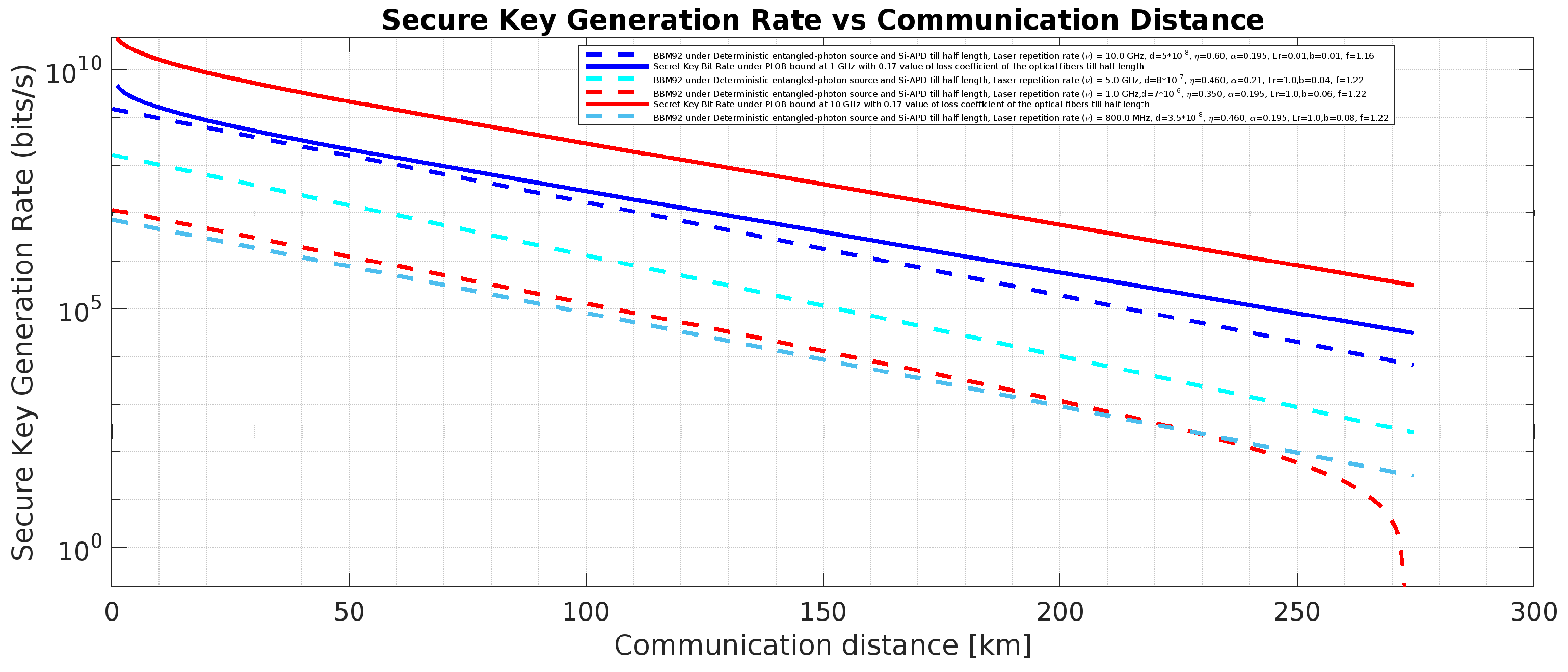

Figure 21.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source placed in the middle and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) Bound (

) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

Figure 21.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source placed in the middle and PLOB (Pirandola-Laurenza-Ottaviani-Banchi) Bound (

) [

24] using Si-APD: Effects of the said attacks on secure key rate.

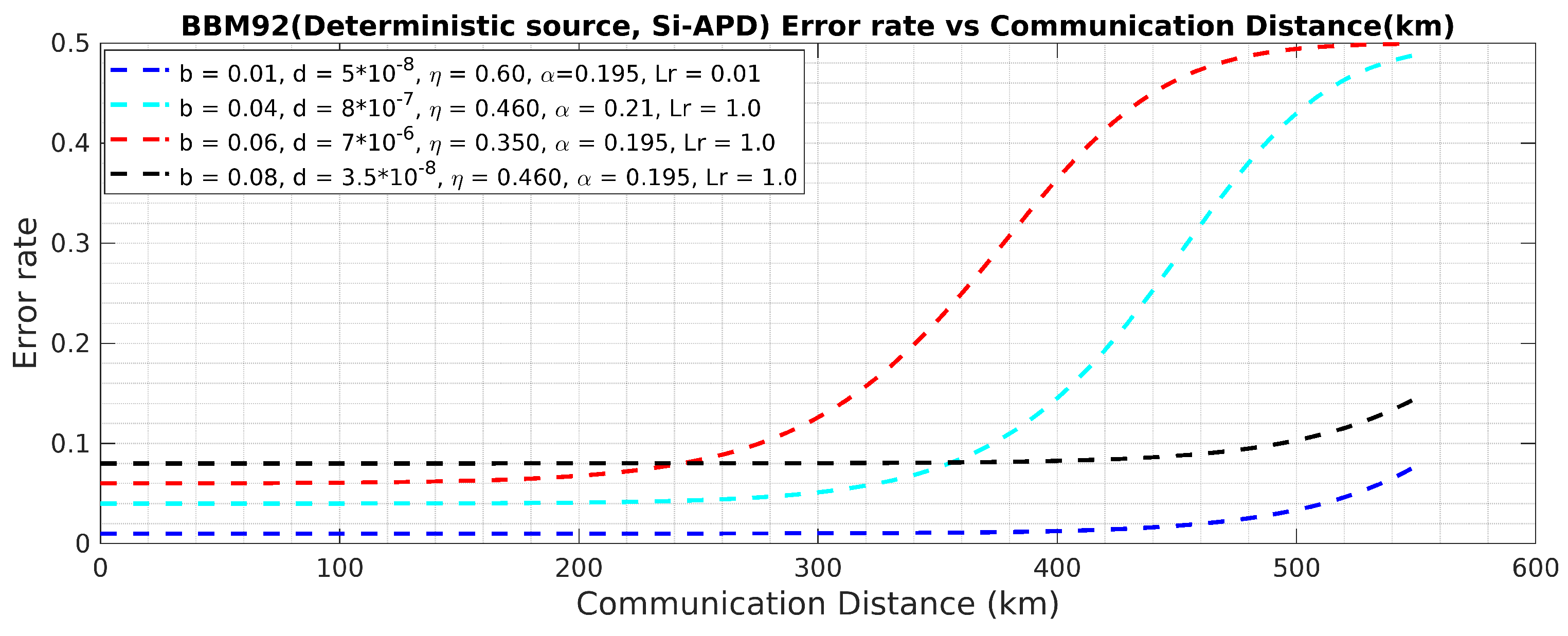

Figure 22.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source using Si-APD: Error Rate Vs Communication Distance (km).

Figure 22.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with deterministic entangled photon source using Si-APD: Error Rate Vs Communication Distance (km).

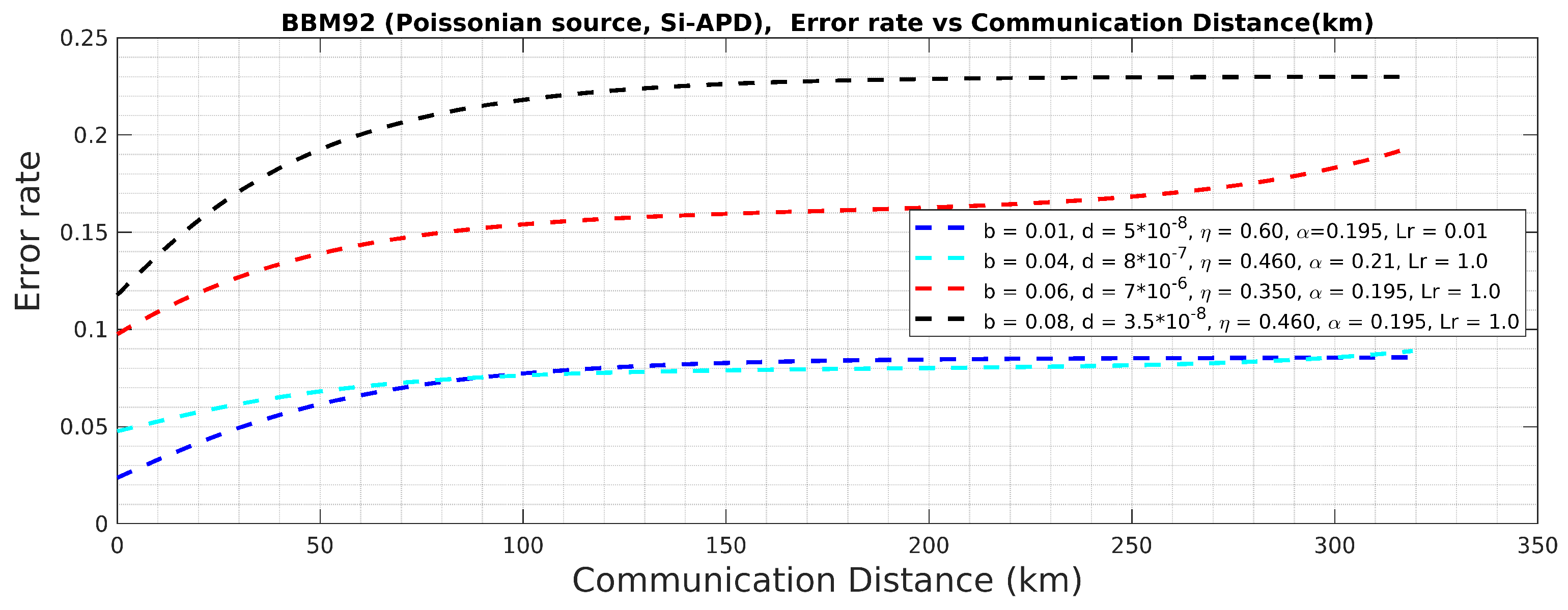

Figure 23.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source using Si-APD: Error Rate Vs Communication Distance (km).

Figure 23.

BBM92 QKD Protocol with Poissonian entangled photon source using Si-APD: Error Rate Vs Communication Distance (km).

5. Results and Discussion

In the current research, we introduced frequency up-conversion process and analyzed two QKD protocols, namely, BBM92 and BB84. The description about the two single photon detectors with the detailed simulation parameters is already mentioned in the previous section. In the current simulation at 1550 nm, we have used 0.17dB/km ((ultra low loss fibers [

47]) and 0.2 dB/ km) as an attenuation coefficient. The other values deployed in the simulation are baseline system error rate,

, extra loss at receiver end is

= 1 dB. The remaining values used in the simulations have been written in the Figure caption. In weak-laser-pulse of BB84 QKD, the mean photon number,

affects the secure key generation rate and is one of the important parameter to be optimized, too low value of

leads to dark counts and higher value of it gives birth to PNS attack. The parameter,

is another important term to be tuned to achieve improved secure key rate in the BBM92 protocol with a Poissonian entangled-photon source.

Figure 1 and

Figure 3 represent the related experiment setup for the current research work, and the detailed description is mentioned in [

19,

62]. The simulation results are highlighted by the Figures (

Figure 2 and from

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21) and produced from the Equations (1) to (31). Inspecting all these, it is observed that the shown results for the considered QKD protocols under the two types of detectors described earlier, depend on various parameters such as dark counts,

d, detector quantum efficiency,

, after pulse probability, and transmission repetition rate,

. Here, out of the two considered detectors, Si-APD with non-gated mode operation and improved timing jitter values provides better results at 1 GHz and 10 GHz, as shown in the simulated results. The considered parameter, dead time,

, is one of the major obstacles in achieving desired optimum results. In the considered Poisson photon source, the term

, represents the two events occurring probability value in increased timing,

, where the deployed number of detectors decide the value of

. The dead time,

, for the used Si-APD detector is 45 ns. The variations in achieved secure communication distance is properly simulated with the variations in pump power,

p. This is achieved by the proper curve fitting method and the used parameter values are shown in the Figure captions. From

Figure 2, and

Figure 4,

Figure 5,

Figure 6,

Figure 7,

Figure 8,

Figure 9,

Figure 10,

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13,

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20 and

Figure 21, it is observed that the improved results of secure key generation rates ranging from

bits/sec to

bits/sec, in the range of 100 km to 600 km communication distance is achieved. All these improved results satisfy the acceptable practical quantum bit error rates as shown in

Figure 20 and

Figure 21. The upper bound of the error rate for secure key generation is computed to be

if the ideal value of the efficiency of the error correction algorithm,

. In addition to these, from

Figure 22 and 23, it is observed that using Si-APD, BBM92 QKD protocol with deterministic entangled photon source (

Figure 22) attains more than 500 Km communication distance as compared to Poissonian entangled photon source (

Figure 23), within the acceptable quantum bit error rate (QBER).Hence, under the considered scenario, we achieve improved results for BBM92 QKD protocol, as highlighted by the simulated results in the

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20,

Figure 21,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23.

Analyzing all the results, we claim that BBM92 QKD protocol under PNS attack outperforms BB84 protocol even if Eve has a quantum memory, the reason being that it is independent of the value of

N, which is nothing but a delay term. In addition to this, from simulation results, in the absence of the quantum memory with an infinitely long coherence time, the communication distance achieved and the secure key generation rate is much affected. Finally, we can claim that the two QKD protocols under investigation with Si-APD under frequency up-conversion shows their practical feasibility under the mentioned realistic conditions, where Si-APD provides improved results as compared to the InGaAs/ InP APD. Also under all such practical and realistic scenarios the entangled-based BBM92 QKD protocol outperforms the BB84 QKD protocol, as highlighted by the simulated results in the

Figure 14,

Figure 15,

Figure 16,

Figure 17,

Figure 18,

Figure 19,

Figure 20,

Figure 21,

Figure 22 and

Figure 23.

6. Conclusion

The two QKD protocols with the considered two APDs perform much better while deploying PPLN waveguide with frequency conversion method which reflects from the simulated results. The improved results obtained provide enhanced secure communication distance and secure key generation rates with Si-APD, as highlighted in various plots which proves its practical feasibility under the considered scenario. Superconducting single photon detectors have low dark count value but require a cryogenic environment to perform as well as being costly to set up under realistic conditions which make them overall complex.

Here, we have simulated the two QKD protocols using the two single photon detectors at telecommunication wavelength. In addition to this, individual and hybrid attacks have been taken into account. The generated simulated results show that under the said attacks and considered simulation parameters with frequency up conversion method the entanglement based BBM92 QKD protocol outperforms BB84 QKD protocol with the deploy Si-APD as a single photon detector. In addition to this, to evaluate the performance of the quantum communication system, we tested the effects of quantum memory which Eve uses to extract the information. Under all these scenarios and at high frequencies i.e., at 1GHz and 10 GHz, it attains a longer secure communication distance in the range of 150 Km to 610 Km with an improved higher secure key rate in the range of

to

bits/sec. To compensate for other fiber losses such as chromatic dispersion and birefringence in optical fibers, it is highly required to use dispersion compensation techniques [

55] and phase-encoding protocols [

3].

Author Contributions

V.S. has directly participated in the planning, execution, and analysis of this study. V.S. drafted the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

V.S. is grateful to Peter van Loock for useful discussions. V. S. acknowledges the financial support obtained from Institute of Physics, Johannes-Gutenberg University of Mainz, Staudingerweg 7, 55128 Mainz, Germany.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this manuscript.

Consent for Publication

Authors are accepting to submit and publish the submitted work.

Ethical Approval

Not Applicable - The manuscript does not contain any human or animal studies.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- Bennett, Charles H and Bessette, François and Brassard, Gilles and Salvail, Louis and Smolin, John, Experimental quantum cryptography J. Cryptology, 5, pages 3–28, (1992). [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Charles H and Brassard, Gilles, Proceedings of the ieee international conference on computers, systems and signal processing, IEEE New York, 5, pages 3–28, (1984).

- Honjo, T and Inoue, K and Takahashi, H, Differential-phase-shift quanum key distribution experiment with a planar light-wave circuit Mach-Zehnder interferometer, Opt. Lett., 29, pages 2797–2799, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Arahira, Shin and Murai, Hitoshi, Effects of afterpulse events on performance of entanglement-based quantum key distribution system, Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, 55(3), pages 032801, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Bennett, Charles H and Brassard, Gilles and Mermin, N David, Quantum cryptography without Bell’s theorem, Physical review letters, APS, 68 (5), pages 557, (1992). [CrossRef]

- Lütkenhaus, Norbert, Security against individual attacks for realistic quantum key distribution, Physical Review A, APS, 61 (5), pages 052304, (2000). [CrossRef]

- Yin, Hua-Lei and Chen, Teng-Yun and Yu, Zong-Wen and Liu, Hui and You, Li-Xing and Zhou, Yi-Heng and Chen, Si-Jing and Mao, Yingqiu and Huang, Ming-Qi and Zhang, Wei-Jun and others, Measurement-device-independent quantum key distribution over a 404 km optical fiber, Physical review letters, APS, 117(19), pages 190501, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Boaron, Alberto and Boso, Gianluca and Rusca, Davide and Vulliez, Cédric and Autebert, Claire and Caloz, Misael and Perrenoud, Matthieu and Gras, Gaëtan and Bussières, Félix and Li, Ming-Jun and others, Secure quantum key distribution over 421 km of optical fiber, Physical review letters, APS, 121(19), pages 190502, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Geng, Jia-Qi and Fan-Yuan, Guan-Jie and Wang, Shuang and Zhang, Qi-Fa and Chen, Wei and Yin, Zhen-Qiang and He, De-Yong and Guo, Guang-Can and Han, Zheng-Fu, Quantum key distribution integrating with ultra-high-power classical optical communications based on ultra-low-loss fiber, Optics letters, Optica Publishing Group, 46(24), pages 6099–6102, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kong, Weiwen and Sun, Yongmei and Gao, Yaoxian and Ji, Yuefeng, Coexistence of quantum key distribution and optical communication with amplifiers over multicore fiber, Nanophotonics, De Gruyter, 12(11), pages 1979–1994, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Bi-Xiao and Mao, Yingqiu and Shen, Lei and Zhang, Lei and Lan, Xiao-Bo and Ge, Dawei and Gao, Yuyang and Li, Juhao and Tang, Yan-Lin and Tang, Shi-Biao and others, Long-distance transmission of quantum key distribution coexisting with classical optical communication over a weakly-coupled few-mode fiber, Optics express, Optica Publishing Group, 28(9), pages 12558–12565, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Waks, Edo and Zeevi, Assaf and Yamamoto, Yoshihisa, Security of quantum key distribution with entangled photons against individual attacks, Physical Review A, APS, 65 (5), pages 052310, (2002). [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Kyo and Waks, Edo and Yamamoto, Yoshihisa, Differential phase shift quantum key distribution, Physical review letters, APS, 89 (3), pages 037902, (2002). [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K and Waks, E and Yamamoto, Y, Differential-phase-shift quantum key distribution using coherent light, Physical Review A, APS, 68 (2), pages 022317, (2003). [CrossRef]

- Yoshizawa, Akio and Kaji, Ryosaku and Tsuchida, Hidemi, 10.5 km fiber-optic quantum key distribution at 1550 nm with a key rate of 45 kHz, Japanese journal of applied physics, IOP Publishing, 43 (6A), pages L735, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Bethune, Donald S and Risk, William P and Pabst, Gary W, A high-performance integrated single-photon detector for telecom wavelengths, Journal of modern optics, Taylor & Francis, 51 (9-10), pages 1359–1368, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Ribordy, Gregoire and Gautier, Jean-Daniel and Zbinden, Hugo and Gisin, Nicolas, Performance of InGaAs/InP avalanche photodiodes as gated-mode photon counters, Applied optics, Optica Publishing Group, , 37(12), pages 2272–2277, (1998). [CrossRef]

- Stucki, Damien and Ribordy, Grégoire and Stefanov, André and Zbinden, Hugo and Rarity, John G and Wall, Tom, Photon counting for quantum key distribution with Peltier cooled InGaAs/InP APDs, Journal of modern optics, Taylor & Francis, 48 (13), pages 1967–1981, (2001). [CrossRef]

- Langrock, Carsten and Diamanti, Eleni and Roussev, Rostislav V and Yamamoto, Yoshihisa and Fejer, Martin M and Takesue, Hiroki, Highly efficient single-photon detection at communication wavelengths by use of upconversion in reverse-proton-exchanged periodically poled LiNbO3 waveguides, Optics letters, Optica Publishing Group, 30 (13), pages 1725–1727, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Bourennane, Mohamed and Karlsson, Anders and Ciscar, Juan Pena and Mathés, Markus, Single-photon counters in the telecom wavelength region of 1550 nm for quantum information processing, Journal of modern optics, Taylor & Francis, 48 (13), pages 1983–1995, (2001). [CrossRef]

- Gobby, C and Yuan, ZL and Shields, AJ, Unconditionally secure quantum key distribution over 50km of standard telecom fibre, arXiv preprint quant-ph/0412173, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Roussev, Rostislav V and Langrock, Carsten and Kurz, Jonathan R and Fejer, Martin M, Periodically poled lithium niobate waveguide sum-frequency generator for efficient single-photon detection at communication wavelengths, Optics letters, Optica Publishing Group, 29 (13), pages 1518–1520, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal, Analysis of Single Photon Detectors in Differential Phase Shift Quantum Key Distribution, Optical and Quantum Electronics, Springer, 55(888), (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pirandola, Stefano and Laurenza, Riccardo and Ottaviani, Carlo and Banchi, Leonardo, Fundamental limits of repeaterless quantum communications, Nature communications, Nature Publishing Group UK London, , 8(1), pages=15043, (2017). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Banerjee, Subhashish, Quantum communication using code division multiple access network, Optical and Quantum Electronics, 52(8), pages 1–22, (2020). [CrossRef]

- Gobby, C and Yuan, aZL and Shields, AJ, Quantum key distribution over 122 km of standard telecom fiber Appl. Phys. Lett., 84, pages 3762–3764, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Raj, Arockia Bazil and Sharma, Vishal and Banerjee, Subhashish, Quantum-based satellite free space optical communication and microwave photonics, Principles and applications of free space optical communications, IET Telecommunications Series, 78, (2019). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Shukla, Chitra and Banerjee, Subhashish and Pathak, Anirban, Controlled bidirectional remote state preparation in noisy environment: A generalized view, Quantum Information Processing, Springer, 14, pages 3441–3464, (2015). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Thapliyal, Kishore and Pathak, Anirban and Banerjee, Subhashish, A comparative study of protocols for secure quantum communication under noisy environment: Single-qubit-based protocols versus entangled-state-based protocols, Quantum Information Processing, Springer, 15, pages 4681–4710, (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Shrikant, U and Srikanth, R and Banerjee, Subhashish, Decoherence can help quantum cryptographic security, Quantum Information Processing, Springer, 17, pages 1–16, (2018). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal, Quantum Communication Under Noisy Environment: From Theory to Applications, Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, (2018).

- Sharma, Vishal and Banerjee, Subhashish, Analysis of quantum key distribution based satellite communication In 2018 9th International Conference on Computing, Communication and Networking Technologies (ICCCNT), pp. 1-5. IEEE, 2018.

- Inoue, K and Waks, E and Yamamoto, Y, Differential-phase-shift quantum key distribution using coherent light Physical Review A, 68(2), pages 022317, (2003). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Banerjee, Subhashish, Analysis of atmospheric effects on satellite-based quantum communication: A comparative study Quantum Information Processing, 18(3), pp. 1–24, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pelc, JS and Zhang, Q and Phillips, CR and Yu, L and Yamamoto, Y and Fejer, MM Cascaded frequency upconversion for high-speed single-photon detection at 1550 nm Optics letters, 37(4), pages 476–478, (2012). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Sharma, Richa, Analysis of spread spectrum in MATLAB International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, 5(1), pp. 1899-1902, 2014. [CrossRef]

- https://www.idquantique.com/quantum-sensing/products/id100/.

- Sharma, Vishal, Effect of Noise on Practical Quantum Communication Systems Defence Science Journal, 66(2), (2016). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Gupta, Shantanu and Mehta, Gaurav and Lad, Bhupesh K A quantum-based diagnostics approach for additive manufacturing machine IET Collaborative Intelligent Manufacturing, 3(2), pages 184–192, (2021). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal, Feasibility of temperature sensors in railway coaches, Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res, 5(2), pages 881–884, (2014). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Panchariya, PC, Experimental use of electronic nose for odour detection, International Journal of Engineering Systems Modelling and Simulation, Inderscience Publishers (IEL), 7(4), pages 238–243, (2015). [CrossRef]

- Inoue, Kyo and Honjo, Toshimori Robustness of differential-phase-shift quantum key distribution against photon-number-splitting attack Physical Review A, 71(4), pages 042305, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Honjo, T and Takesue, H and Kamada, H and Nishida, Y and Tadanaga, O and Asobe, M and Inoue, K Long-distance distribution of time-bin entangled photon pairs over 100 km using frequency up-conversion detectors Optics express, 15(21), pages 13957–13964, (2007). [CrossRef]

- Gisin, Nicolas and Ribordy, Grégoire and Tittel, Wolfgang and Zbinden, Hugo, Quantum cryptography Reviews of modern physics, 74(1), pages 145–195, (2002). [CrossRef]

- Brassard, Gilles and Salvail, L, Advances in cryptology eurocrypt’93, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 765, pages 410–423, (1994).

- https://www.aureatechnology.com/images/produits.

- https://www.corning.com/optical communications/worldwide/en/home/products/fiber/optical-fiber-products/smf-28-ull.html.

- Tamura, Yoshiaki and Sakuma, Hirotaka and Morita, Keisei and Suzuki, Masato and Yamamoto, Yoshinori and Shimada, Kensaku and Honma, Yuya and Sohma, Kazuyuki and Fujii, Takashi and Hasegawa, Takemi, Lowest-ever 0.1419-dB/km loss optical fiber, Optical fiber communication Conference, Optica Publishing Group, 765, pages Th5D–1, (2017).

- Sharma, Vishal, Quantum Communication Under Noisy Environment: From Theory to Applications, Indian Institute of Technology Jodhpur, 2018.

- Gisin, Nicolas and Ribordy, Grégoire and Zbinden, Hugo and Stucki, Damien and Brunner, Nicolas and Scarani, Valerio, Towards practical and fast quantum cryptography, arXiv preprint quant-ph/0411022, 2004. [CrossRef]

- Lo, Hoi-Kwong and Ma, Xiongfeng and Chen, Kai, Decoy state quantum key distribution, Physical review letters, 94(23), pages 230504, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Fasel, Sylvain and Alibart, Olivier and Tanzilli, Sebastien and Baldi, Pascal and Beveratos, Alexios and Gisin, Nicolas and Zbinden, Hugo, High-quality asynchronous heralded single-photon source at telecom wavelength, New Journal of Physics, IOP Publishing, 6(1), pages 163, (2004).

- Yoshizawa, Akio and Kaji, Ryosaku and Tsuchida, Hidemi, 10.5 km fiber-optic quantum key distribution at 1550 nm with a key rate of 45 kHz, Japanese journal of applied physics, IOP Publishing, 43(6A), pages L735, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Ma, Xiongfeng and Qi, Bing and Zhao, Yi and Lo, Hoi-Kwong, Practical decoy state for quantum key distribution, Physical Review A, APS, 72(1), pages 012326, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Fasel, Sylvain and Gisin, Nicolas and Ribordy, Grégoire and Zbinden, Hugo, Quantum key distribution over 30 km of standard fiber using energy-time entangled photon pairs: A comparison of two chromatic dispersion reduction methods, The European Physical Journal D-Atomic, Molecular, Optical and Plasma Physics, Springer, 30(1), pages 143–148, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Honjo, T and Inoue, K and Takahashi, H, Differential-phase-shift quantum key distribution experiment with a planar light-wave circuit Mach–Zehnder interferometer, Optics letters, Optica Publishing Group, 29(23), pages 2797–2799, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Albota, Marius A and Wong, Franco NC, Efficient single-photon counting at 1.55 μm by means of frequency upconversion. [CrossRef]

- Vandevender, Aaron P and Kwiat, Paul G, High efficiency single photon detection via frequency up-conversion, Journal of Modern Optics, Taylor & Francis, 51(9-10), pages 1433–1445, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Vishal and Bhardwaj, Asha, Analysis of Differential Phase Shift Quantum Key Distribution using single-photon detectors, 2022 International Conference on Numerical Simulation of Optoelectronic Devices (NUSOD), IEEE, pages 17–18, (2022).

- Scarani, Valerio and Acin, Antonio and Ribordy, Grégoire and Gisin, Nicolas, Quantum cryptography protocols robust against photon number splitting attacks for weak laser pulse implementations, Physical review letters, APS, 92(5), pages 057901, (2004). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Xiang-Bin, Beating the photon-number-splitting attack in practical quantum cryptography, Physical review letters, APS, 94(23), pages 230503, (2005). [CrossRef]

- Thew, Robert T and Tanzilli, Sébastien and Krainer, Lukas and Zeller, Simon C and Rochas, Alexis and Rech, Ivan and Cova, Sergio and Zbinden, Hugo and Gisin, Nicolas, Low jitter up-conversion detectors for telecom wavelength GHz QKD, New Journal of Physics, IOP Publishing, 8(3), pages 32, (2006). [CrossRef]

- Langrock, Carsten and Diamanti, Eleni and Roussev, Rostislav V and Yamamoto, Yoshihisa and Fejer, Martin M and Takesue, Hiroki, Highly efficient single-photon detection at communication wavelengths by use of upconversion in reverse-proton-exchanged periodically poled LiNbO3 waveguides, Optics letters, Optica Publishing Group, 30 (13), pages 1725–1727, (2005). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).