1. Introduction

Chewing is a complex process, in which many elements of the stomatognathic system intervene. Unilateral mastication (UM) refers to the habitual use of one side of the mouth during chewing, a pattern observed in a significant portion of the population. This behavior has garnered attention due to its potential to induce various asymmetries in craniofacial structures, leading to health concerns such as temporomandibular disorders (TMD), occlusal imbalances, and even systemic effects like hearing loss [

1,

2,

3]. UM has been extensively associated with altered functional and postural dynamics of the masticatory system, which may further impact structures related to the airway and facial symmetry[

4,

5,

6].

Research on the impact of unilateral mastication has predominantly focused on the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) and occlusal forces, demonstrating that these repetitive habits can lead to an overload on one side of the dental arches. This imbalance not only affects dental and joint health but can also contribute to significant skeletal changes, including deviations in the nasal septum and asymmetrical development of the maxilla[

4,

7]. However, less is known about how this habitual asymmetry in chewing might affect the anatomy of the nasal airways, specifically regarding the potential narrowing of the nasal passage on the preferred chewing side.

In addition to the previously described associations between unilateral mastication (UM) and craniofacial structures, recent research suggests that masticatory patterns may also influence postural balance and spinal alignment. A study highlights a potential relationship between altered mastication and the development of scoliosis, emphasizing the interconnectedness between the stomatognathic system and the musculoskeletal system[

8,

9,

10].

These findings strengthen the hypothesis that mastication not only affects localized structures but may also have systemic impacts on anatomically and functionally related areas. Similarly, the interaction between masticatory patterns and upper airway structures, such as the nasal windows, might be mediated by muscular mechanisms or adaptive anatomical changes. This perspective underscores the clinical relevance of this study and suggests future research avenues into the systemic implications of masticatory habits.

The nasal airway plays a crucial role in respiration, and its structure can be sensitive to external forces and functional patterns, including those originating from the masticatory system[

11]. Studies on craniofacial growth in both human and animal models suggest that altered masticatory function can influence the development of nasal and sinus structures. In particular, unilateral masticatory function has been linked to changes in the maxillary sinuses, the glenoid fossa, and potentially the nasal airway, which may contribute to breathing difficulties and other respiratory issues[

11,

12].

Despite these observations, there is scant research regarding the direct relationship between unilateral mastication and nasal airway narrowing. This represents an important lacuna in literature since any conceivable change in nasal anatomy might spill over to relevance in airway management and craniofacial treatment planning as well. Nasal airway narrowing impairs breathing patterns, which in turn exacerbates other conditions such as sleep-disordered breathing and increased oral respiration[

1,

2]. Furthermore, asymmetry in the nasal windows may also result in aesthetic issues, affecting the appearance of the nose and the overall harmony of the face[

13].

Since it is a pilot study, it is planned to find out whether unilateral mastication is associated with the preferred chewing side by narrowing the nasal airway. For this reason, this study investigates 24 patients and describes preliminary data about the influence of habitual chewing practices on nasal anatomy by providing a basis for further studies in the effects of masticatory habits on craniofacial development and respiratory health in general.

2. Materials and Methods

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia, with approval No. M10/2024/097.

The inclusion criteria were as follows, ensuring homogeneity of the study sample:

Adults aged 18 years or older.

Subjects that have never received any orthodontic treatment of any kind and are not edentulous.

participants gave informed consent before being included in this study.

The habitual chewing side was determined by two major methods:

1. Preferential Chewing Side: This was self-reported by the subjects in the first visit and one week later to check for reliability in the response.

2.Observational Method: Patients are given a piece of chewing gum and are asked to chew for a minute. The predominant chewing side is observed by a trained clinician.

Following are the details of everything done to collect comprehensive data.

Intraoral Photography: Photographs were taken in maximal intercuspation to document the dental arches in order to visualize and determines the chewing side.

Orthopantomography: For panoramic radiographs, the mandibular and dental structures were checked.

Nasal Windows Photography: Photography at the shooting details of the nasal windows was carried out for the analysis of general features and dimensions of the nose.

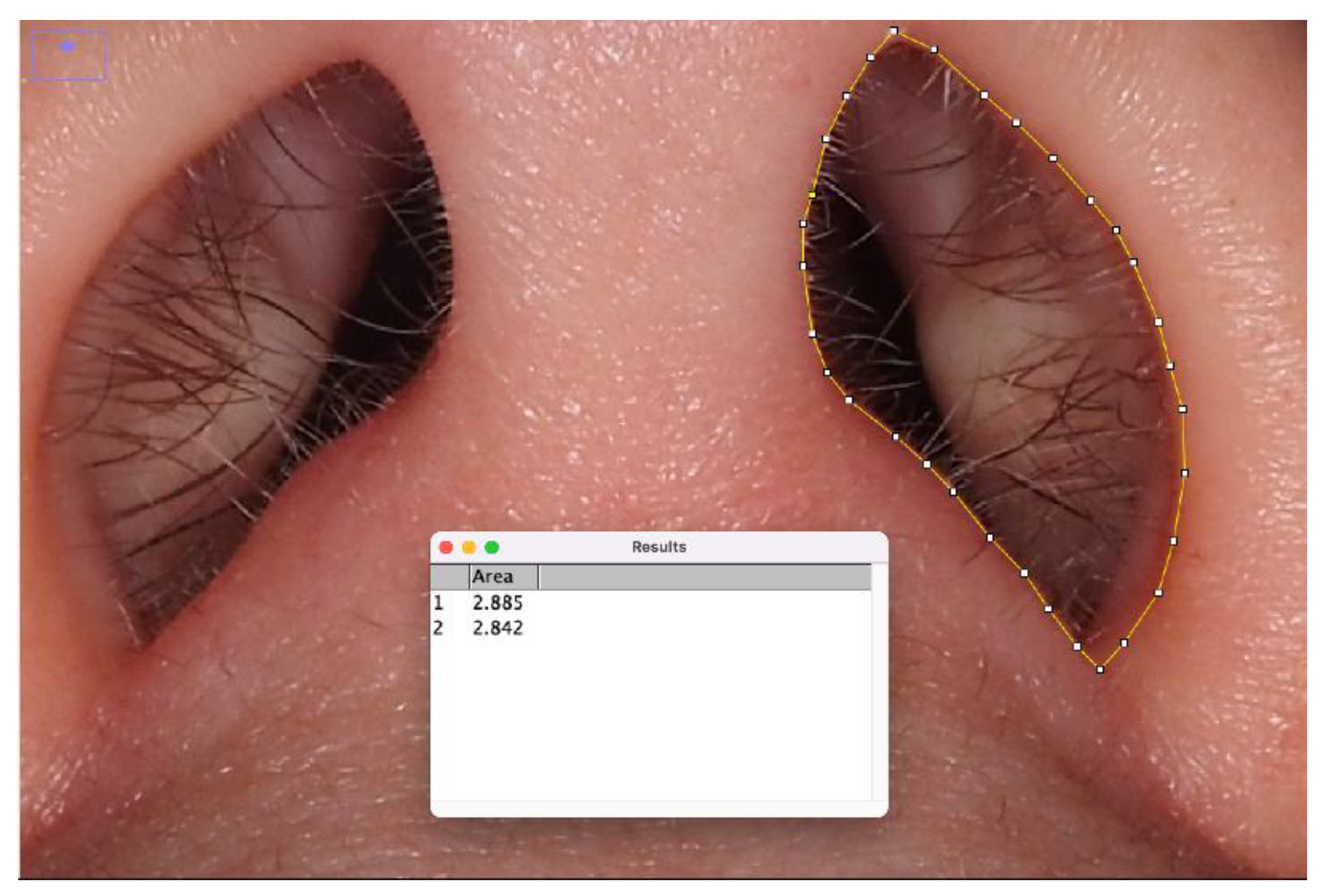

Two blinded observers, other than the original examiner, analyzed the obtained images without prior information regarding the patient's reported chewing side. The two observers, using ImageJ® software, measured the openings of both the right and left nasal windows and noted which was smaller (Fig1)

Figure 1.

Example of how the nasal windows were measured by the observers. The right and left nasal apertures were outlined using ImageJ® software, and the areas of each nasal window were calculated in square units. Observers were blinded to the patients' reported chewing side during this measurement process to ensure unbiased analysis.

Figure 1.

Example of how the nasal windows were measured by the observers. The right and left nasal apertures were outlined using ImageJ® software, and the areas of each nasal window were calculated in square units. Observers were blinded to the patients' reported chewing side during this measurement process to ensure unbiased analysis.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 4.4.1[

14].

The following tests were performed:

Descriptive Analysis: Median, mean, and standard deviation were calculated for numerical variables, and frequencies for categorical variables.

Normality Tests: Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to determine the normality of numerical variables.

-

Association Analysis:

- ∘

Fisher's exact test was used to analyze the relationship between the chewing side and the smaller nasal window.

- ∘

Kruskal-Wallis test was applied for non-parametric comparisons of age across groups.

Significance Level: Results were considered significant if p < 0.05.

3. Results

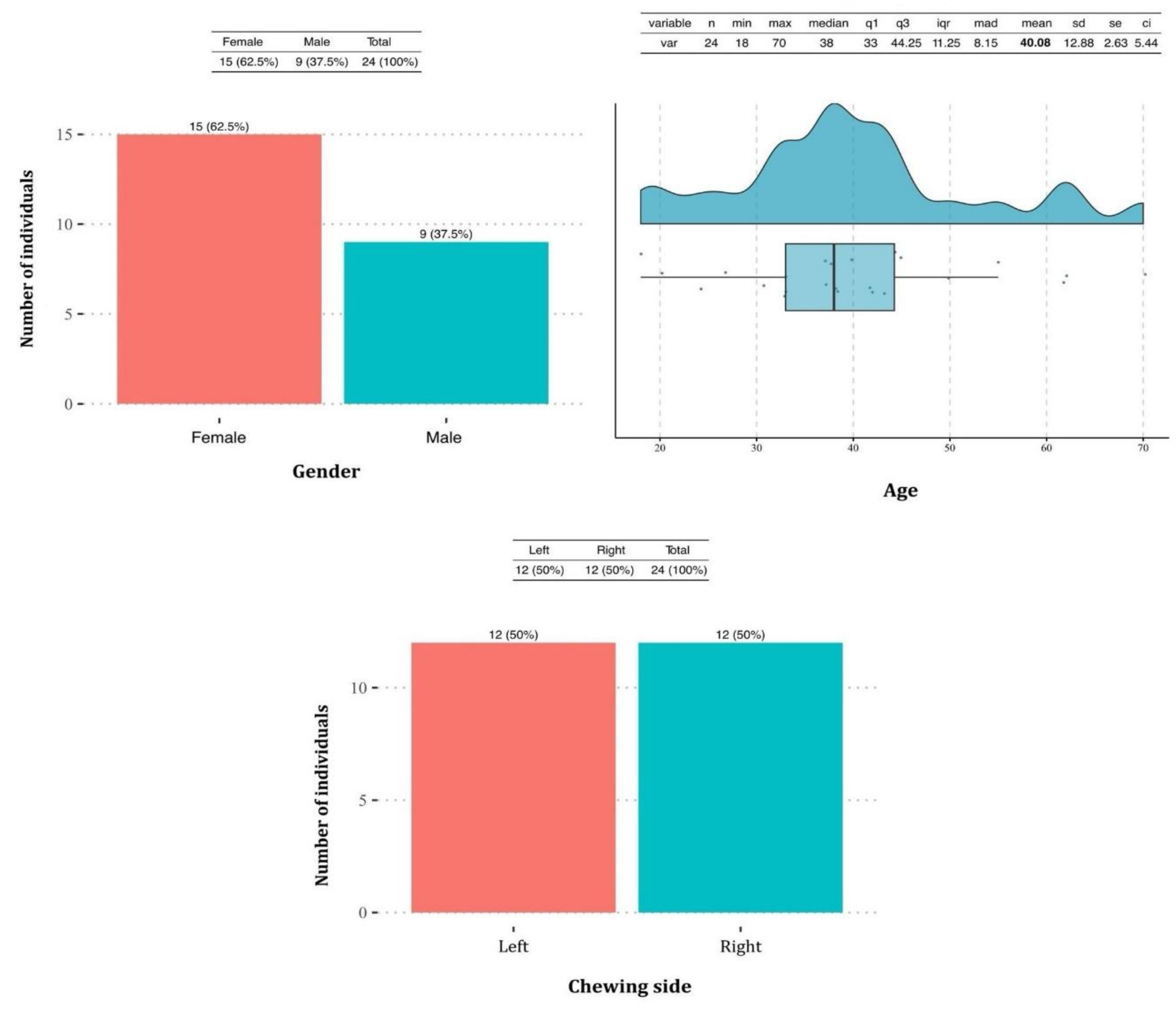

The study included 24 participants, of whom 62.5% (n=15) were female and 37.5% (n=9) were male. The median age of the participants was 38 years, ranging from 18 to 70 years. Regarding chewing side preferences, the distribution was perfectly balanced, with 50% (n=12) of the participants favoring the right side and the other 50% (n=12) favoring the left side.(

Figure 2)

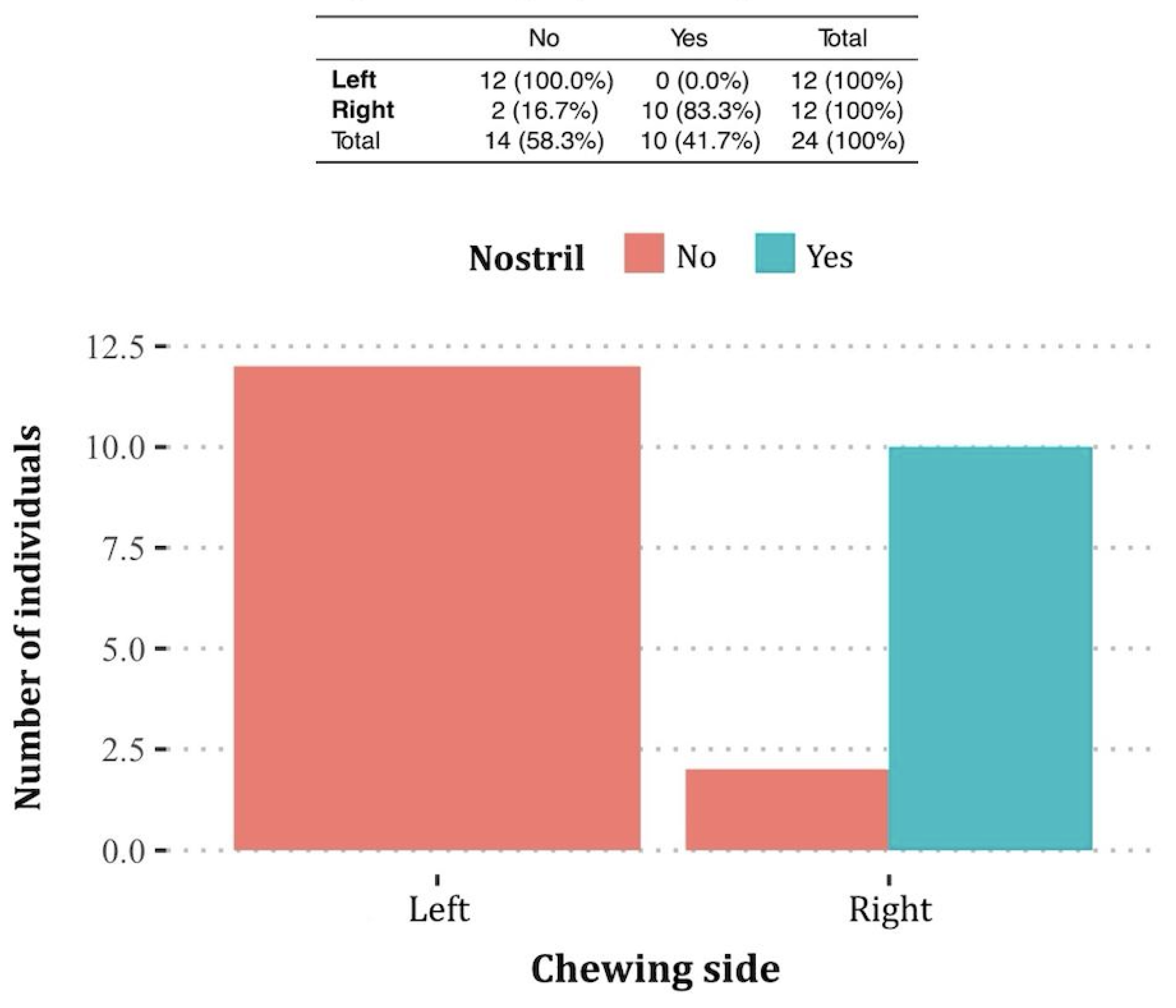

An analysis of nasal window asymmetry revealed that 41.7% (n=10) of participants exhibited a smaller right nasal window, while 58.3% (n=14) had a smaller left nasal window. A significant association was observed between the preferred chewing side and the smaller nasal window (p < 0.001)(

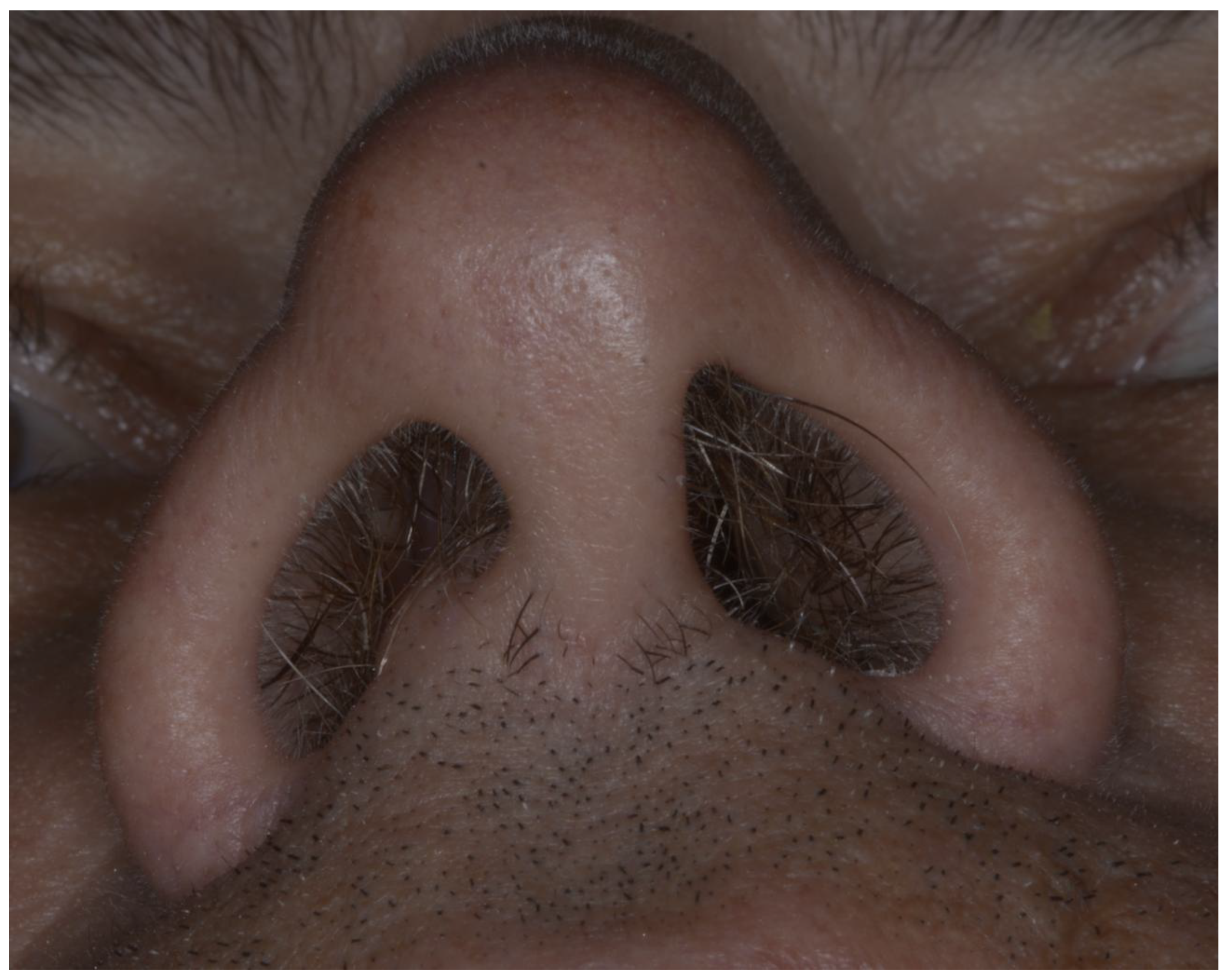

Figure 3). Specifically, participants who chewed predominantly on the right side were more likely to have a smaller right nasal window. This relationship is illustrated in

Figure 4, which provides an example of a right-side chewer with a visibly narrower right nasal window, reinforcing the observed link between chewing side and nasal asymmetry.

These findings suggest a strong association between unilateral chewing habits and nasal airway asymmetry, providing novel insights into the potential anatomical and functional implications of habitual masticatory patterns.

The phi coefficient for the relationship between chewing side and nasal window was ϕ = 0.845, indicating a large effect size. This suggests a strong association between these variables.

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between unilateral habitual chewing and asymmetry of nasal apertures in patients in an adult population. Our findings showed a significant statistical relationship existed regarding the selected side of chewing and the smaller nasal window. Notably, subjects with a smaller right nasal window showed preference for chewing on the right side, which was reflected in the strong effect size: ϕ = 0.845. These findings suggest that a functional and, possibly, anatomic relation exists between the asymmetry of the nasal airway and habitual chewing.

Previous studies demonstrated that unilateral mastication alters the development of craniofacial structures such as the TMJ, maxillary sinuses, and mandibular development[

1,

6]. However, the clear explanation of the analysis concerning asymmetry in the nasal window and its relationship with chewing pattern was not fully explained. Our results agree with those investigations that stated, because of habitual continuous function like unilateral mastication, asymmetry in supra-adjacent structures might be caused or enhanced, It also happens in other disciplines such as sports[

15,

16].

Furthermore, recent studies have highlighted a potential link between unilateral mastication and postural imbalances, including scoliosis[

8,

17]. This suggests that masticatory function may influence musculoskeletal systems beyond the craniofacial region. These observations align with our hypothesis that chewing patterns may impact the nasal airway and related anatomical features, emphasizing the interconnected nature of craniofacial and postural systems.

This might be explained by the fact that structures in the craniofacial complex are developmentally and functionally interrelated, and unilateral masticatory forces can result in either a mechanical influence on the pattern of tissue remodeling of the nasal and maxillary tissues or a change in airflow dynamics[

18]. The hypertrophy of the masticatory muscles acting on the side of preferred chewing also may be another reason for the asymmetry of the anatomical spare side features [

12,

19].

Furthermore, the link between mastication and nasal airway asymmetry may also involve neuromuscular adaptations. Research suggests that prolonged unilateral activity can alter the coordination of muscles involved in mastication and adjacent structures, potentially leading to compensatory changes in other areas, such as the nasal and pharyngeal regions[

20]. These findings highlight the complexity of interactions between functional habits and anatomical structures, providing new insights into the broader implications of habitual behaviors.

Understanding how mastication and nasal asymmetry are related will have overwhelming relevance to both dentistry and otolaryngology. Identifying habitual chewing patterns as one of the possible causes of nasal airway asymmetry may probably allow for an improved diagnosis and management of the related pathologies such as nasal obstruction or temporomandibular disorders. In addition, such findings emphasize the importance of encouraging balanced mastication as a mode of prevention or reduction in asymmetric craniofacial development.

In addition to its functional impact, nasal airway asymmetry can also have aesthetic consequences, affecting facial harmony and patient self-esteem. Studies have shown that individuals with nasal deformities, such as a crooked nose, often experience reduced self-esteem and quality of life. Surgical correction of these deformities can lead to significant improvements in both appearance and psychological well-being[

21].

While the findings are intriguing, there are a few limitations surrounding this study:First, the relatively small sample size, comprising 24 participants, limits generalizability of the findings, as any observed associations would need to be confirmed in a much larger cohort representative of a more diverse population.The cross-sectional design of the research does not allow determining the cause-effect relationship between habitual chewing patterns and nasal asymmetry. It is unknown whether the asymmetry results from the chewing habits or if it predisposes the individuals to the use of one side of the mouth.

Third, though ImageJ software permits the accurate measurement of nasal dimensions, manual input of data ensures observer bias during this process is inevitable, despite the fact that the evaluators were blinded to the patients' reported chewing sides. Some limitations are mentioned herein; thus, further studies need to build up from these findings with better methodologies and increased sample sizes.

Further research should focus on:

Longitudinal studies: By following the patients in time, it would detect if unilateral chewing habits produce progressive nasal asymmetry.

Larger Sample Sizes: To ensure increased statistical power and thus confirm these results in heterogeneous populations.

Intervention Studies: These will determine if interventions aimed at symmetric mastication reduce or reverse nasal asymmetry. Conclusion This study accordingly uncovers a strong relationship between the habitual pattern of chewing and the symmetries of the nasal window, offering new insights into the complex interactions between masticatory function and craniofacial anatomy. Such findings will set a framework for further investigation of the clinical implications of mastication within a context of nasal and respiratory health.

5. Conclusions

This study highlights a significant association between habitual chewing patterns and nasal window asymmetry, providing novel insights into the interplay between masticatory function and craniofacial anatomy. These findings lay the groundwork for further exploration into the clinical relevance of mastication in the context of nasal and respiratory health, further research with larger sample sizes is necessary to confirm and expand upon these results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, X.X. and Y.Y.; methodology, X.X.; software, X.X.; validation, X.X., Y.Y. and Z.Z.; formal analysis, X.X.; investigation, X.X.; resources, X.X.; data curation, X.X.; writing—original draft preparation, X.X.; writing—review and editing, X.X.; visualization, X.X.; supervision, X.X.; project administration, X.X.; funding acquisition, Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.” Please turn to the CRediT taxonomy for the term explanation. Authorship must be limited to those who have contributed substantially to the work reported.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Murcia, with approval No. M10/2024/097.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Lee YR, Choi JS, Kim HE. Unilateral Chewing as a Risk Factor for Hearing Loss: Association between Chewing Habits and Hearing Acuity. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2018;246(1):45-50. [CrossRef]

- Lee JY, Lee ES, Kim GM, Jung HI, Lee JW, Kwon HK, et al. Unilateral Mastication Evaluated Using Asymmetric Functional Tooth Units as a Risk Indicator for Hearing Loss. J Epidemiol. 2019;29(8):302-7. [CrossRef]

- Fujita Y, Motegi E, Nomura M, Kawamura S, Yamaguchi D, Yamaguchi H. Oral habits of temporomandibular disorder patients with malocclusion. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2003;44(4):201-7. [CrossRef]

- Rovira-Lastra B, Flores-Orozco EI, Ayuso-Montero R, Peraire M, Martinez-Gomis J. Peripheral, functional and postural asymmetries related to the preferred chewing side in adults with natural dentition. J Oral Rehabil. 2016;43(4):279-85. [CrossRef]

- Yalcin Yeler D, Yilmaz N, Koraltan M, Aydin E. A survey on the potential relationships between TMD, possible sleep bruxism, unilateral chewing, and occlusal factors in Turkish university students. Cranio. 2017;35(5):308-14. [CrossRef]

- Santana-Mora U, Lopez-Cedrun J, Mora MJ, Otero XL, Santana-Penin U. Temporomandibular disorders: the habitual chewing side syndrome. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e59980. [CrossRef]

- Yu Q, Liu Y, Chen X, Chen D, Xie L, Hong X, et al. Prevalence and associated factors for temporomandibular disorders in Chinese civilian pilots. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(7):905-11. [CrossRef]

- Ucar I, Batin S, Arik M, Payas A, Kurtoglu E, Kararti C, et al. Is scoliosis related to mastication muscle asymmetry and temporomandibular disorders? A cross-sectional study. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2022;58:102533. [CrossRef]

- Saccomanno S, Saran S, Paskay LC, Giannotta N, Mastrapasqua RF, Pirino A, et al. Malocclusion and Scoliosis: Is There a Correlation? J Pers Med. 2023;13(8). [CrossRef]

- Saccucci M, Tettamanti L, Mummolo S, Polimeni A, Festa F, Tecco S. Scoliosis and dental occlusion: a review of the literature. Scoliosis. 2011;6:15. [CrossRef]

- Mizumachi-Kubono M, Watari I, Ishida Y, Ono T. Unilateral maxillary molar extraction influences AQP5 expression and distribution in the rat submandibular salivary gland. Arch Oral Biol. 2012;57(7):877-83. [CrossRef]

- Poikela A, Kantomaa T, Tuominen M, Pirttiniemi P. Effect of unilateral masticatory function on craniofacial growth in the rabbit. Eur J Oral Sci. 1995;103(2 ( Pt 1)):106-11. [CrossRef]

- Ozkan MC, Bayramicli M. Perception of Nasal Aesthetics: Nose or Face? Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022;46(6):2931-7. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team (2024). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical.

- Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/.

- Maly T, Hank M, Verbruggen FF, Clarup C, Phillips K, Zahalka F, et al. Relationships of lower extremity and trunk asymmetries in elite soccer players. Front Physiol. 2024;15:1343090. [CrossRef]

- Markovic G, Sarabon N, Pausic J, Hadzic V. Adductor Muscles Strength and Strength Asymmetry as Risk Factors for Groin Injuries among Professional Soccer Players: A Prospective Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14). [CrossRef]

- Piancino MG, Tortarolo A, Macdonald F, Garagiola U, Nucci L, Brayda-Bruno M. Spinal disorders and mastication: The potential relationship between adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and alterations of the chewing patterns. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2023;26(2):178-84. [CrossRef]

- Liu Z, Zhang N, Chen S, Lei L. Effect of Maxillary Skeletal Expansion on Airflow Dynamics of the Upper Airway. J Craniofac Surg. 2022;33(6):1684-9. [CrossRef]

- Santana-Mora U, Lopez-Cedrun J, Suarez-Quintanilla J, Varela-Centelles P, Mora MJ, Da Silva JL, et al. Asymmetry of dental or joint anatomy or impaired chewing function contribute to chronic temporomandibular joint disorders. Ann Anat. 2021;238:151793. [CrossRef]

- Schubert D, Proschel P, Schwarz C, Wichmann M, Morneburg T. Neuromuscular control of balancing side contacts in unilateral biting and chewing. Clin Oral Investig. 2012;16(2):421-8. [CrossRef]

- Jadczak M, Krzywdzinska S, Rozbicki P, Jurkiewicz D. The Crooked Nose-Surgical Algorithm in Post-Traumatic Patient-Evaluation of Surgical Sequence. J Clin Med. 2024;14(1). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).