Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Senescence. History and Mechanisms

1.1. SASP: Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype

1.2. Senescence Signaling Networks

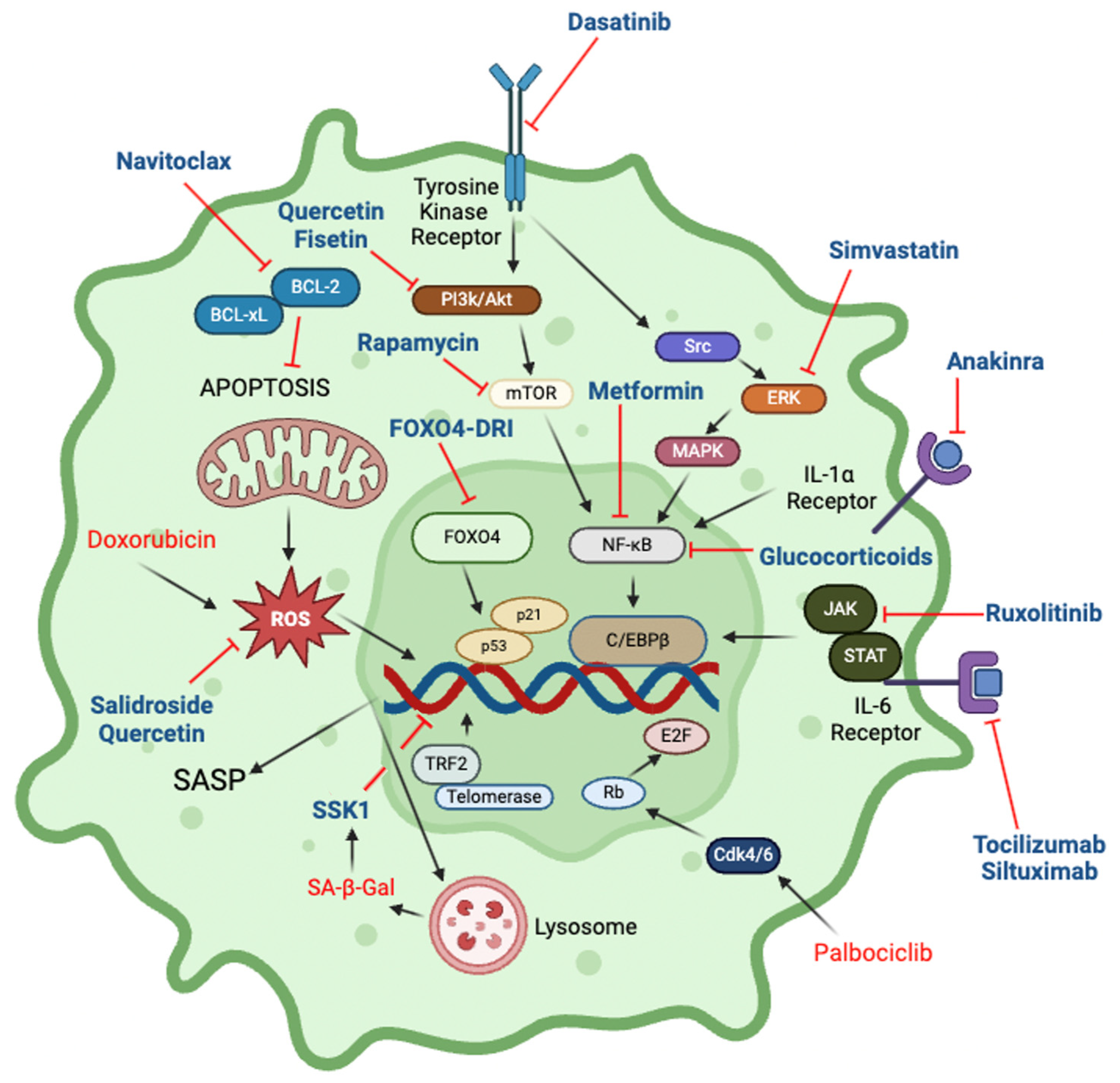

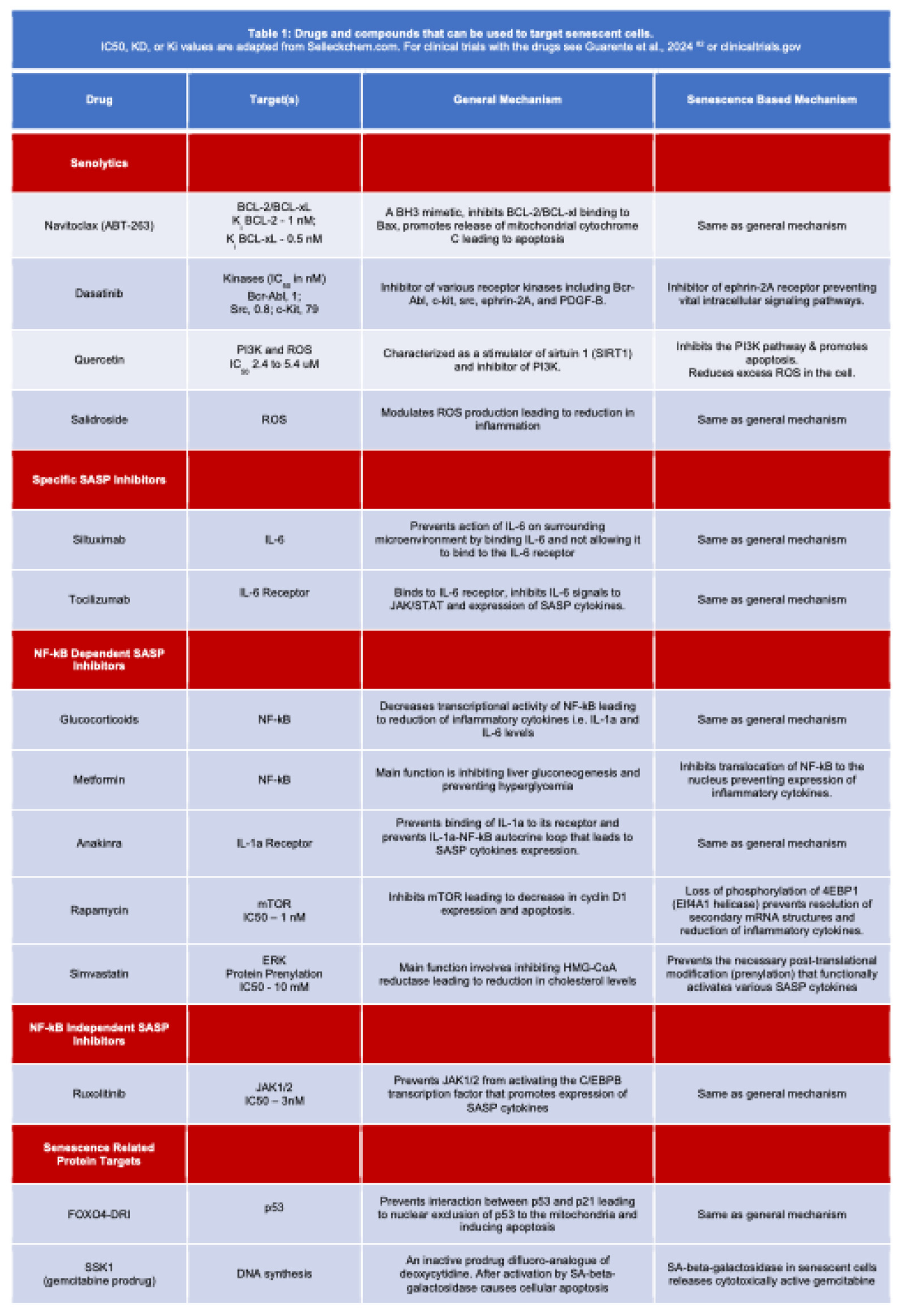

1.3. Therapeutic Targeting of Senescence

1.4. Impact of Senescence on Drug Action

1.5. Therapy Induced Senescence

2. Senotherapy

2.1. Senolytics

2.1.1. Navitoclax

2.1.2. Fisetin & Quercetin

2.1.3. Quercetin

2.1.4. Salidroside

2.1.5. SSK1

2.1.6. Conclusions and Outlook.

2.2. Reducing SASP effects

2.3. Targeting Senescence-related Proteins

3. Concluding Remarks—Promises and Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, W.; Hickson, L.J.; Eirin, A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lerman, L.O. Cellular Senescence: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2022, 18, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campisi, J.; Fagagna, F. d’Adda di Cellular Senescence: When Bad Things Happen to Good Cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkwood, T.B.L.; Cremer, T. Cytogerontology since 1881: A Reappraisal of August Weismann and a Review of Modern Progress. Hum. Genet. 1982, 60, 101–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado, M.; Blasco, M.A.; Serrano, M. Cellular Senescence in Cancer and Aging. Cell 2007, 130, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayflick, L.; Moorhead, P.S. The Serial Cultivation of Human Diploid Cell Strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961, 25, 585–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shay, J.W.; Wright, W.E. Hayflick, His Limit, and Cellular Ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2000, 1, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Childs, B.G.; Gluscevic, M.; Baker, D.J.; Laberge, R.-M.; Marquess, D.; Dananberg, J.; Deursen, J.M. van Senescent Cells: An Emerging Target for Diseases of Ageing. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2017, 16, 718–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J.-P.; Rodier, F.; Patil, C.K.; Freund, A.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Tumor Suppressor and Aging Biomarker P16INK4a Induces Cellular Senescence without the Associated Inflammatory Secretory Phenotype*. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 36396–36403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, M.; Lin, A.W.; McCurrach, M.E.; Beach, D.; Lowe, S.W. Oncogenic Ras Provokes Premature Cell Senescence Associated with Accumulation of P53 and P16INK4a. Cell 1997, 88, 593–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herranz, N.; Gil, J. Mechanisms and Functions of Cellular Senescence. J. Clin. Investig. 2018, 128, 1238–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Schmidt, M.O.; Kallakury, B.; Jain, S.; Mehdikhani, S.; Levi, M.; Mendonca, M.; Welch, W.; Riegel, A.T.; Wilcox, C.S.; et al. Low Dose Chronic Angiotensin II Induces Selective Senescence of Kidney Endothelial Cells. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 782841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wharton, W.; Donovan, M.; Coppola, D.; Croxton, R.; Cress, W.D.; Pledger, W.J. Density-Dependent Growth Inhibition of Fibroblasts Ectopically Expressing P27kip1. Mol. Biol. Cell 2000, 11, 2117–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Müller, G.A. Cell Cycle Transcription Control: DREAM/MuvB and RB-E2F Complexes. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 52, 638–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimri, G.P.; Lee, X.; Basile, G.; Acosta, M.; Scott, G.; Roskelley, C.; Medrano, E.E.; Linskens, M.; Rubelj, I.; Pereira-Smith, O.; et al. A Biomarker That Identifies Senescent Human Cells in Culture and in Aging Skin in Vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1995, 92, 9363–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.Y.; Han, J.A.; Im, J.S.; Morrone, A.; Johung, K.; Goodwin, E.C.; Kleijer, W.J.; DiMaio, D.; Hwang, E.S. Senescence-associated Β-galactosidase Is Lysosomal Β-galactosidase. Aging Cell 2006, 5, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, J.; Damaschke, N.; Yang, B.; Truong, M.; Guenther, C.; McCormick, J.; Huang, W.; Jarrard, D. Overexpression of the Novel Senescence Marker β-Galactosidase (GLB1) in Prostate Cancer Predicts Reduced PSA Recurrence. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieben, C.J.; Sturmlechner, I.; Sluis, B. van de; Deursen, J.M. van Two-Step Senescence-Focused Cancer Therapies. Trends Cell Biol. 2018, 28, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.-W.; Yevsa, T.; Woller, N.; Hoenicke, L.; Wuestefeld, T.; Dauch, D.; Hohmeyer, A.; Gereke, M.; Rudalska, R.; Potapova, A.; et al. Senescence Surveillance of Pre-Malignant Hepatocytes Limits Liver Cancer Development. Nature 2011, 479, 547–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.H.; Choi, Y.W.; Lee, J.; Soh, E.Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, T.J. Senescent Tumor Cells Lead the Collective Invasion in Thyroid Cancer. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuilman, T.; Michaloglou, C.; Vredeveld, L.C.W.; Douma, S.; Doorn, R. van; Desmet, C.J.; Aarden, L.A.; Mooi, W.J.; Peeper, D.S. Oncogene-Induced Senescence Relayed by an Interleukin-Dependent Inflammatory Network. Cell 2008, 133, 1019–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhland, M.K.; Loza, A.J.; Capietto, A.-H.; Luo, X.; Knolhoff, B.L.; Flanagan, K.C.; Belt, B.A.; Alspach, E.; Leahy, K.; Luo, J.; et al. Stromal Senescence Establishes an Immunosuppressive Microenvironment That Drives Tumorigenesis. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J.-P.; Patil, C.K.; Rodier, F.; Sun, Y.; Muñoz, D.P.; Goldstein, J.; Nelson, P.S.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J. Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotypes Reveal Cell-Nonautonomous Functions of Oncogenic RAS and the P53 Tumor Suppressor. PLoS Biol. 2008, 6, e301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppé, J.-P.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Krtolica, A.; Campisi, J. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype: The Dark Side of Tumor Suppression. Pathol.: Mech. Dis. 2010, 5, 99–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, S.S.; Sojo, G.B.; Sun, H.; Friedland, B.N.; McNamara, M.E.; Schmidt, M.O.; Wellstein, A. The Role of Aging and Senescence in Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Response and Toxicity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orjalo, A.V.; Bhaumik, D.; Gengler, B.K.; Scott, G.K.; Campisi, J. Cell Surface-Bound IL-1α Is an Upstream Regulator of the Senescence-Associated IL-6/IL-8 Cytokine Network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2009, 106, 17031–17036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Tchkonia, T.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Kirkland, J.L.; Lee, S. COVID-19 and Cellular Senescence. Nat Rev Immunol 2023, 23, 251–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Rosen, D.G.; Zhang, Z.; Bast, R.C.; Mills, G.B.; Colacino, J.A.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Liu, J. The Chemokine Growth-Regulated Oncogene 1 (Gro-1) Links RAS Signaling to the Senescence of Stromal Fibroblasts and Ovarian Tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2006, 103, 16472–16477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Hornsby, P.J. Senescent Human Fibroblasts Increase the Early Growth of Xenograft Tumors via Matrix Metalloproteinase Secretion. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 3117–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritschka, B.; Storer, M.; Mas, A.; Heinzmann, F.; Ortells, M.C.; Morton, J.P.; Sansom, O.J.; Zender, L.; Keyes, W.M. The Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype Induces Cellular Plasticity and Tissue Regeneration. Genes Dev. 2017, 31, 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodier, F.; Coppé, J.-P.; Patil, C.K.; Hoeijmakers, W.A.M.; Muñoz, D.P.; Raza, S.R.; Freund, A.; Campeau, E.; Davalos, A.R.; Campisi, J. Persistent DNA Damage Signalling Triggers Senescence-Associated Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 973–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freund, A.; Patil, C.K.; Campisi, J. P38MAPK Is a Novel DNA Damage Response-independent Regulator of the Senescence-associated Secretory Phenotype. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 1536–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoare, M.; Ito, Y.; Kang, T.-W.; Weekes, M.P.; Matheson, N.J.; Patten, D.A.; Shetty, S.; Parry, A.J.; Menon, S.; Salama, R.; et al. NOTCH1 Mediates a Switch between Two Distinct Secretomes during Senescence. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016, 18, 979–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, Y.V.; Rattanavirotkul, N.; Olova, N.; Salzano, A.; Quintanilla, A.; Tarrats, N.; Kiourtis, C.; Müller, M.; Green, A.R.; Adams, P.D.; et al. Notch Signaling Mediates Secondary Senescence. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 997–1007.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laberge, R.-M.; Sun, Y.; Orjalo, A.V.; Patil, C.K.; Freund, A.; Zhou, L.; Curran, S.C.; Davalos, A.R.; Wilson-Edell, K.A.; Liu, S.; et al. MTOR Regulates the Pro-Tumorigenic Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype by Promoting IL1A Translation. Nat. Cell Biol. 2015, 17, 1049–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodier, F.; Muñoz, D.P.; Teachenor, R.; Chu, V.; Le, O.; Bhaumik, D.; Coppé, J.-P.; Campeau, E.; Beauséjour, C.M.; Kim, S.-H.; et al. DNA-SCARS: Distinct Nuclear Structures That Sustain Damage-Induced Senescence Growth Arrest and Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 124, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toso, A.; Mitri, D.D.; Alimonti, A. Enhancing Chemotherapy Efficacy by Reprogramming the Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype of Prostate Tumors. OncoImmunology 2015, 4, e994380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, H.; Pardoll, D.; Jove, R. STATs in Cancer Inflammation and Immunity: A Leading Role for STAT3. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarze, S.R.; Fu, V.X.; Desotelle, J.A.; Kenowski, M.L.; Jarrard, D.F. The Identification of Senescence-Specific Genes during the Induction of Senescence in Prostate Cancer Cells. Neoplasia 2005, 7, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toso, A.; Revandkar, A.; Di Mitri, D.; Guccini, I.; Proietti, M.; Sarti, M.; Pinton, S.; Zhang, J.; Kalathur, M.; Civenni, G.; et al. Enhancing Chemotherapy Efficacy in Pten-Deficient Prostate Tumors by Activating the Senescence-Associated Antitumor Immunity. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Bar-Sagi, D. Oncogenic KRas Suppresses Inflammation-Associated Senescence of Pancreatic Ductal Cells. Cancer Cell 2010, 18, 448–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, X.; LaPak, K.M.; Hennessey, R.C.; Yu, C.Y.; Shakya, R.; Zhang, J.; Burd, C.E. Stromal Senescence By Prolonged CDK4/6 Inhibition Potentiates Tumor Growth. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017, 15, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Capparelli, C.; Chiavarina, B.; Whitaker-Menezes, D.; Pestell, T.G.; Pestell, R.G.; Hulit, J.; Andò, S.; Howell, A.; Martinez-Outschoorn, U.E.; Sotgia, F.; et al. CDK Inhibitors (P16/P19/P21) Induce Senescence and Autophagy in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts, “Fueling” Tumor Growth via Paracrine Interactions, without an Increase in Neo-Angiogenesis. Cell Cycle 2012, 11, 3599–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallanis, G.T.; Sharif, G.M.; Schmidt, M.O.; Friedland, B.N.; Battina, R.; Rahhal, R.; Davis, J.E.; Khan, I.S.; Wellstein, A.; Riegel, A.T. Stromal Senescence Following Treatment with the CDK4/6 Inhibitor Palbociclib Alters the Lung Metastatic Niche and Increases Metastasis of Drug-Resistant Mammary Cancer Cells. Cancers 2023, 15, 1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommier, Y. Drugging Topoisomerases: Lessons and Challenges. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 82–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wellstein, A.; Sausville, E.A. Cytotoxics and Antimetabolites. In Goodman and Gilman’s The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics.; Brunton, L., Knollmann, B., Eds.; 2023; pp. 1340–1380.

- Pommier, Y.; Leo, E.; Zhang, H.; Marchand, C. DNA Topoisomerases and Their Poisoning by Anticancer and Antibacterial Drugs. Chem. Biol. 2010, 17, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demaria, M.; O’Leary, M.N.; Chang, J.; Shao, L.; Liu, S.; Alimirah, F.; Koenig, K.; Le, C.; Mitin, N.; Deal, A.M.; et al. Cellular Senescence Promotes Adverse Effects of Chemotherapy and Cancer Relapse. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaib, S.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. Cellular Senescence and Senolytics: The Path to the Clinic. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1556–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkland, J.L.; Tchkonia, T.; Zhu, Y.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D. The Clinical Potential of Senolytic Drugs. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2017, 65, 2297–2301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.; Tchkonia, T.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Gower, A.C.; Ding, H.; Giorgadze, N.; Palmer, A.K.; Ikeno, Y.; Hubbard, G.B.; Lenburg, M.; et al. The Achilles’ Heel of Senescent Cells: From Transcriptome to Senolytic Drugs. Aging Cell 2015, 14, 644–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.; Wang, Y.; Shao, L.; Laberge, R.-M.; Demaria, M.; Campisi, J.; Janakiraman, K.; Sharpless, N.E.; Ding, S.; Feng, W.; et al. Clearance of Senescent Cells by ABT263 Rejuvenates Aged Hematopoietic Stem Cells in Mice. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudin, C.M.; Hann, C.L.; Garon, E.B.; Oliveira, M.R. de; Bonomi, P.D.; Camidge, D.R.; Chu, Q.; Giaccone, G.; Khaira, D.; Ramalingam, S.S.; et al. Phase II Study of Single-Agent Navitoclax (ABT-263) and Biomarker Correlates in Patients with Relapsed Small Cell Lung Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012, 18, 3163–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, J.E.; Jimenez, C.A.; Mauro, M.J.; Geyer, A.; Pinilla-Ibarz, J.; Smith, B.D. Pleural Effusion in Dasatinib-Treated Patients With Chronic Myeloid Leukemia in Chronic Phase: Identification and Management. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2017, 17, 78–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, D.; Garg, V.K.; Tuli, H.S.; Yerer, M.B.; Sak, K.; Sharma, A.K.; Kumar, M.; Aggarwal, V.; Sandhu, S.S. Fisetin and Quercetin: Promising Flavonoids with Chemopreventive Potential. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Doornebal, E.J.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Giorgadze, N.; Wentworth, M.; Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg, H.; Niedernhofer, L.J.; Robbins, P.D.; Tchkonia, T.; Kirkland, J.L. New Agents That Target Senescent Cells: The Flavone, Fisetin, and the BCL-XL Inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging (Albany NY) 2017, 9, 955–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Pirtskhalava, T.; Farr, J.N.; Weigand, B.M.; Palmer, A.K.; Weivoda, M.M.; Inman, C.L.; Ogrodnik, M.B.; Hachfeld, C.M.; Fraser, D.G.; et al. Senolytics Improve Physical Function and Increase Lifespan in Old Age. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 1246–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meharena, H.S.; Marco, A.; Dileep, V.; Lockshin, E.R.; Akatsu, G.Y.; Mullahoo, J.; Watson, L.A.; Ko, T.; Guerin, L.N.; Abdurrob, F.; et al. Down-Syndrome-Induced Senescence Disrupts the Nuclear Architecture of Neural Progenitors. Cell Stem Cell 2022, 29, 116–130.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.-S.; Li, J.; Chen, L.; Yang, Y.-F.; He, P.-L.; Li, J.; Yang, J. Salidroside Attenuates Endothelial Cellular Senescence via Decreasing the Expression of Inflammatory Cytokines and Increasing the Expression of SIRT3. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2018, 175, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donato, A.J.; Morgan, R.G.; Walker, A.E.; Lesniewski, L.A. Cellular and Molecular Biology of Aging Endothelial Cells. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2015, 89, 122–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Björkegren, J.L.M.; Lusis, A.J. Atherosclerosis: Recent Developments. Cell 2022, 185, 1630–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Ji, Y.; Xue, A.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Elimination of Senescent Cells by β-Galactosidase-Targeted Prodrug Attenuates Inflammation and Restores Physical Function in Aged Mice. Cell Res. 2020, 30, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasek, N.S.; Kuchel, G.A.; Kirkland, J.L.; Xu, M. Strategies for Targeting Senescent Cells in Human Disease. Nat. Aging 2021, 1, 870–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.J.; Childs, B.G.; Durik, M.; Wijers, M.E.; Sieben, C.J.; Zhong, J.; Saltness, R.A.; Jeganathan, K.B.; Verzosa, G.C.; Pezeshki, A.; et al. Naturally Occurring P16Ink4a-Positive Cells Shorten Healthy Lifespan. Nature 2016, 530, 184–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Zhou, H.; Zhu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Ji, Y.; Xue, A.; Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Yu, X.; Wang, L.; et al. Elimination of Senescent Cells by β-Galactosidase-Targeted Prodrug Attenuates Inflammation and Restores Physical Function in Aged Mice. Cell Res 2020, 30, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rovillain, E.; Mansfield, L.; Caetano, C.; Alvarez-Fernandez, M.; Caballero, O.L.; Medema, R.H.; Hummerich, H.; Jat, P.S. Activation of Nuclear Factor-Kappa B Signalling Promotes Cellular Senescence. Oncogene 2011, 30, 2356–2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emery, P.; Keystone, E.; Tony, H.P.; Cantagrel, A.; Vollenhoven, R. van; Sanchez, A.; Alecock, E.; Lee, J.; Kremer, J. IL-6 Receptor Inhibition with Tocilizumab Improves Treatment Outcomes in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis Refractory to Anti-Tumour Necrosis Factor Biologicals: Results from a 24-Week Multicentre Randomised Placebo-Controlled Trial. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 2008, 67, 1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, F. van; Wong, R.S.; Munshi, N.; Rossi, J.-F.; Ke, X.-Y.; Fosså, A.; Simpson, D.; Capra, M.; Liu, T.; Hsieh, R.K.; et al. Siltuximab for Multicentric Castleman’s Disease: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014, 15, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soto-Gamez, A.; Demaria, M. Therapeutic Interventions for Aging: The Case of Cellular Senescence. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22, 786–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrousos, G.P.; Kino, T. Glucocorticoid Signaling in the Cell. Ann. N. York Acad. Sci. 2009, 1179, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavri, S.; Trusca, V.G.; Simionescu, M.; Gafencu, A.V. Metformin Reduces the Endotoxin-Induced down-Regulation of Apolipoprotein E Gene Expression in Macrophages. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015, 461, 435–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moiseeva, O.; Deschênes-Simard, X.; St-Germain, E.; Igelmann, S.; Huot, G.; Cadar, A.E.; Bourdeau, V.; Pollak, M.N.; Ferbeyre, G. Metformin Inhibits the Senescence-associated Secretory Phenotype by Interfering with IKK/NF-κB Activation. Aging Cell 2013, 12, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niehof, M.; Streetz, K.; Rakemann, T.; Bischoff, S.C.; Manns, M.P.; Horn, F.; Trautwein, C. Interleukin-6-Induced Tethering of STAT3 to the LAP/C/EBPβ Promoter Suggests a New Mechanism of Transcriptional Regulation by STAT3*. J. Biol. Chem. 2001, 276, 9016–9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palsuledesai, C.C.; Distefano, M.D. Protein Prenylation: Enzymes, Therapeutics, and Biotechnology Applications. ACS Chem. Biol. 2015, 10, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Uppal, H.; Demaria, M.; Desprez, P.-Y.; Campisi, J.; Kapahi, P. Simvastatin Suppresses Breast Cancer Cell Proliferation Induced by Senescent Cells. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 17895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaie-Majd, A.; Maca, T.; Bucek, R.A.; Valent, P.; Müller, M.R.; Husslein, P.; Kashanipour, A.; Minar, E.; Baghestanian, M. Simvastatin Reduces Expression of Cytokines Interleukin-6, Interleukin-8, and Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein-1 in Circulating Monocytes From Hypercholesterolemic Patients. Arter., Thromb., Vasc. Biol. 2002, 22, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoda, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Negishi, Y.; Liao, J.K.; Node, K.; Izumi, Y. Simvastatin Decreases IL-6 and IL-8 Production in Epithelial Cells. J. Dent. Res. 2006, 85, 520–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baar, M.P.; Brandt, R.M.C.; Putavet, D.A.; Klein, J.D.D.; Derks, K.W.J.; Bourgeois, B.R.M.; Stryeck, S.; Rijksen, Y.; Willigenburg, H. van; Feijtel, D.A.; et al. Targeted Apoptosis of Senescent Cells Restores Tissue Homeostasis in Response to Chemotoxicity and Aging. Cell 2017, 169, 132–147.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keizer, P.L.J. de; Packer, L.M.; Szypowska, A.A.; Riedl-Polderman, P.E.; Broek, N.J.F. van den; Bruin, A. de; Dansen, T.B.; Marais, R.; Brenkman, A.B.; Burgering, B.M.T. Activation of Forkhead Box O Transcription Factors by Oncogenic BRAF Promotes P21cip1-Dependent Senescence. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 8526–8536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boer, J. de; Donker, I.; Wit, J. de; Hoeijmakers, J.H.; Weeda, G. Disruption of the Mouse Xeroderma Pigmentosum Group D DNA Repair/Basal Transcription Gene Results in Preimplantation Lethality. Cancer Res. 1998, 58, 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Guarente, L.; Sinclair, D.A.; Kroemer, G. Human Trials Exploring Anti-Aging Medicines. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, T.; Hussain, A.I.; Casilli, T.P.; Frayser, L.; Cho, M.; Williams, G.; McFall, D.; Forcelli, P.A. Prophylactic Senolytic Treatment in Aged Mice Reduces Seizure Severity and Improves Survival from Status Epilepticus. Aging Cell 2024, 23, e14239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarente, L.; Sinclair, D.A.; Kroemer, G. Human Trials Exploring Anti-Aging Medicines. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 354–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).