2.1. Control System Architecture

The AO wavefront control objective in DE-LBP application is the achievement and maintenance the highest possible laser power density within the vicinity of a pre-selected point (aimpoint) at a remotely located target via adaptive shaping (control) of the transmitted laser beam wavefront phase

[

2,

9]. Here

and

t are, correspondingly, the coordinate vector at the DE-LBP system transceiver telescope (beam director, BD) pupil plane and time.

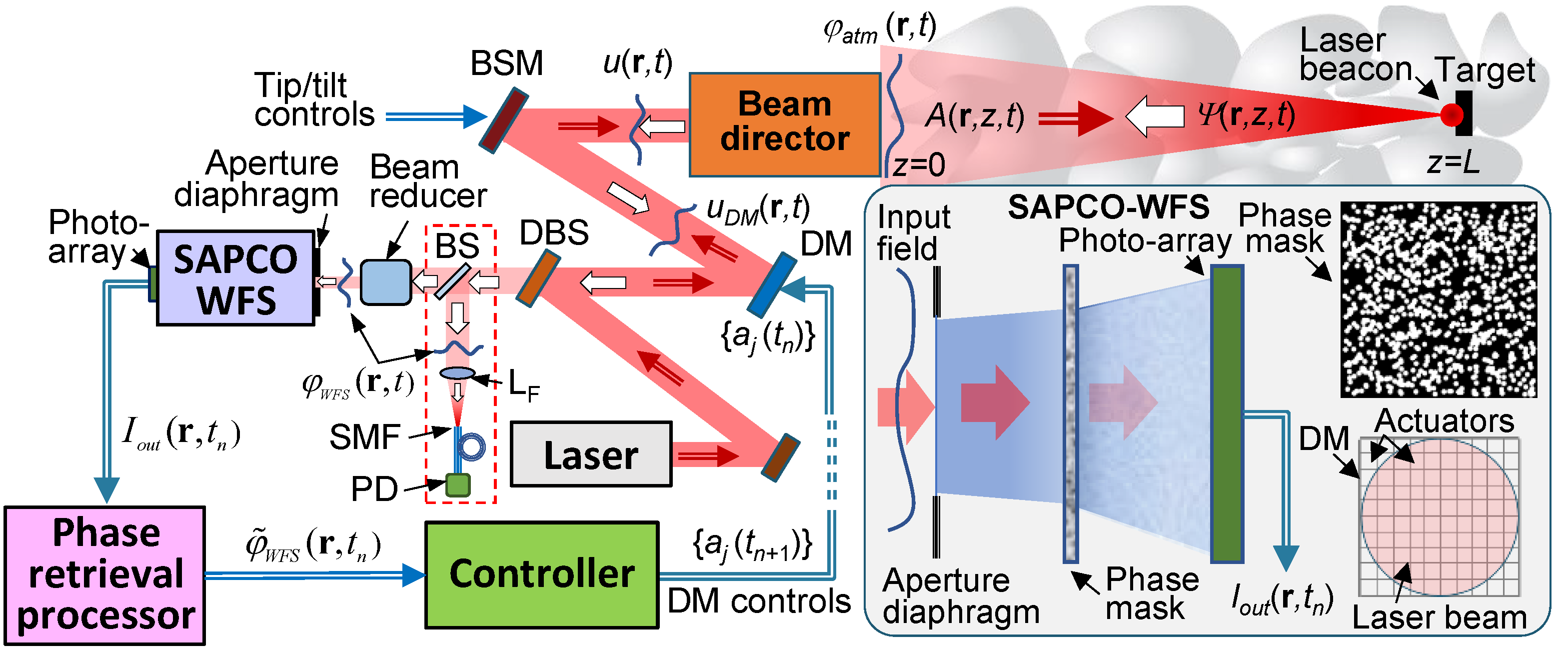

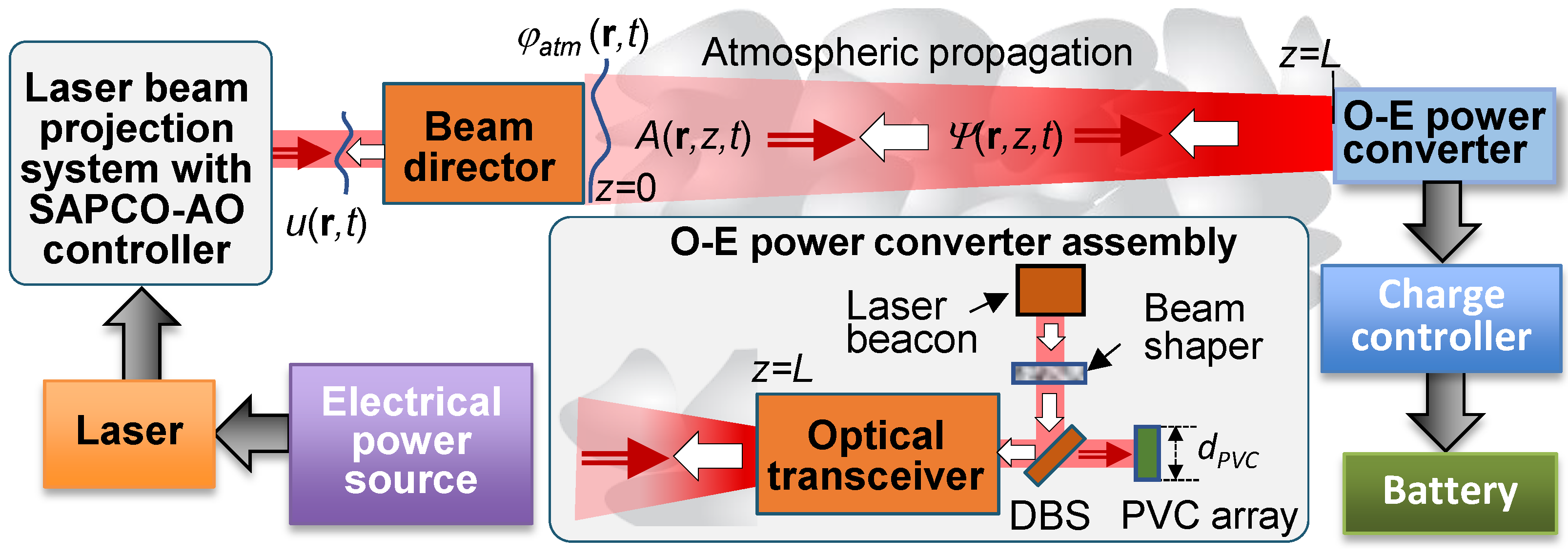

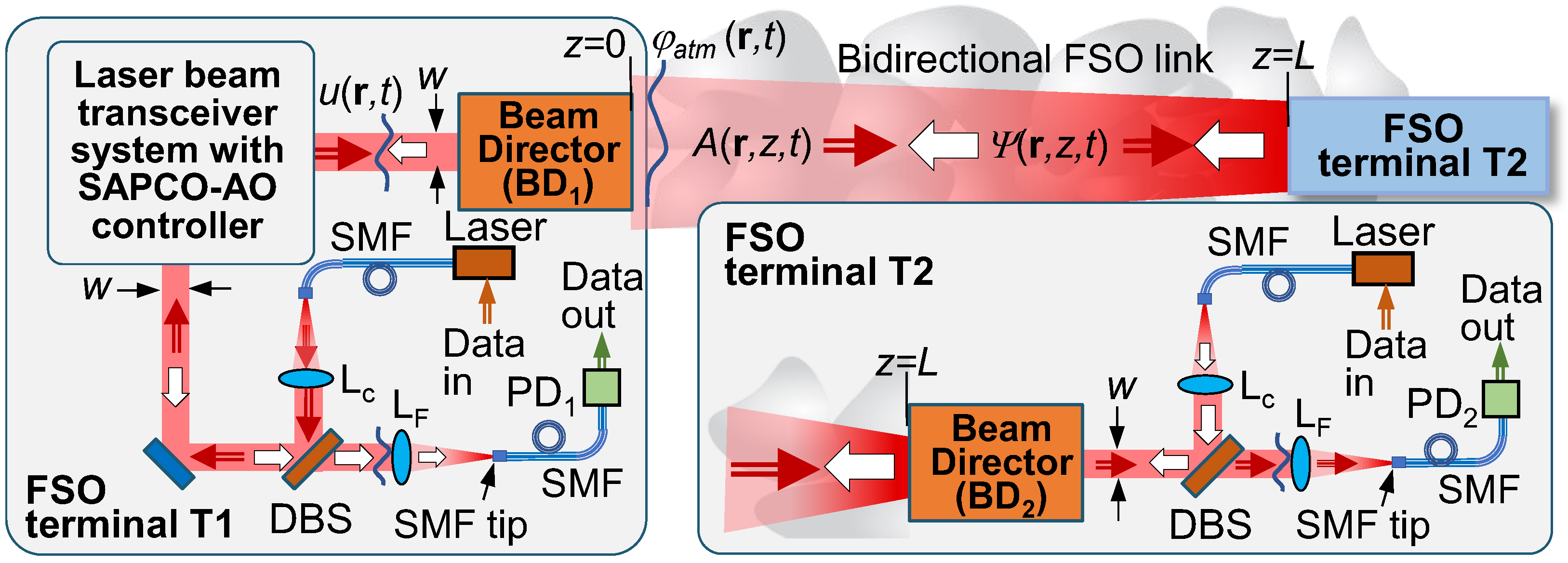

Figure 1 provides a notional schematic for a generic DE-LBP system architecture considered here. Wavefront control in this system is based on closed-loop instantaneous sensing and mitigation (pre-compensation) of atmospheric turbulence-induced phase aberrations by utilizing a single wavefront corrector – deformable mirror (DM). Note that the acronym DM is commonly applied independent of wavefront corrector type e.g., continuous surface or segmented type mirrors [

10,

11], or liquid crystal (LC)-based phase spatial light modulators (SLM) [

12,

13]. To simplify analysis and primarily focus on issues essential for IPR-based wavefront sensing and control we intentionally consider here only an idealized model for a segmented-type wavefront corrector that is comprised of a densely packed array of

NDM =

nDM x

nDM square mirrors (subapertures) providing independent control of subaperture-averaged (piston) phases. This wavefront corrector is referred to here as piston DM. The insert in

Figure 1 illustrates a piston DM of with

NDM = 100 (

nDM=10) subapertures.

In practical A-AO systems the turbulence-induced tip and tilt (tip/tilt) phase aberration components are commonly pre-compensated using a special wavefront corrector, commonly referred to as beam steering mirror (BSM), and the corresponding feedback control system (not shown in

Figure 1). For simplicity, here we assume that the BSM-based control enables complete removal of tip/tilt aberrations from the entering WFS optical field as discussed in Part I (

Section 4.3). In the efficiency analysis of the SAPCO-AO control we consider operational regimes with and without preliminary removal of tip/tilt aberrations.

In the A-AO system in

Figure 1, the BSM and DM are located inside the optical train shared by both the transmitted (outgoing) laser beam and received laser beacon (reference) wave – a typical arrangement for A-AO systems based on monostatic beam directors with phase conjugation (PC) – type control [

9,

14]. In these AO system types the pupil plane of the BD transceiver telescope is reimaged (with corresponding demagnification) to the BSM, DM, and WFS input plane (WFS aperture diaphragm). The reimaging optics (not shown in

Figure 1) provides matching of the corresponding aperture sizes. Note that prior to entering the WFS the received reference (beacon) wave is reflected from the BSM and DM in the order illustrated in

Figure 1.

The wavefront phase

of the received optical field at the SAPCO WFS input plane can be represented in the form

, where

is the turbulence-induced phase aberration at the BD pupil plane, and

and

are controllable wavefront phase distributions introduced by the DM and BSM respectively. The demagnification factors

MDM,

MBSM and

MWFS in this expression describe rescaling of the BD aperture of size

D to, correspondingly, the DM, BSM and WFS aperture sizes. In the M&S optical field demagnification can be accounted for by simple reassignment of the corresponding numerical grid pixel size. To simplify notation, we assume

MBSM =

MDM =

MWFS =1. In this case the received optical wave phase at the WFS input plane can be represented in the following simple form:

where

is the controllable phase introduced into the transmitted beam and received (beacon) wave by the DM and BMS.

Similar as in Part I (Ref. [

1]), in the M&S we consider a SAPCO WFS with square aperture of size

DWFS =

D/MD =3.55 mm, where

MD = 84.4 is the overall demagnification factor corresponding to reimaging of the BD aperture of size

D =30 cm into the WFS aperture diaphragm. The parameters specified in M&S for

DWFS and

D were chosen to correspondingly match the dimension of a commercially available CCD camera and a BD transceiver telescope aperture size typical for DE-LBP and remote laser power beaming applications. In analysis of the SAPCO-AO based FSO communication link in

Section 4, we also considered laser transceivers with a BD aperture of size

D =15 cm. In order to keep the parameter

DWFS unchanged, the demagnification factor

MD was reduced by two fold. The SAPCO WFS parameters used in numerical simulations, including phase mask characteristics, distances between WFS optical elements and the phase retrieval computational grid resolution (grid size

NPR), are identical as in Part I (see

Section 3 and

Section 4 in Ref. [

1]).

In analysis of DE-LBP systems with SAPCO-AO control it is assumed that the reference optical wave is originated from a coherent monochromatic light source (laser beacon) located at the target aimpoint and that the beacon beam size

db does not exceed the diffraction-limited size

(unresolved beacon) for the transmitter aperture of diameter

D:

. Here

is the Airy disk diameter,

λ is laser beacon wavelength, and

L is distance from the BD transceiver telescope pupil plane to the target. The beacon beam is commonly generated in the DE-LBP systems using a supplementary illuminator laser system (not shown in

Figure 1) that operates at a wavelength slightly different from the projected laser beam wavelength, thus enabling separation of the transmitted (outgoing) and received laser beacon optical waves inside the DE-LBP system optical train with a dichroic beam splitter (DBS), as illustrated in

Figure 1. In M&S this difference in wavelengths was considered small and was neglected.

2.2. SAPCO-AO Feedback Control System

In the DE-LBP system schematic in

Figure 1, the control voltages (controls) {

aj (

tn)} (

j=1, …,

NDM) applied to DM actuators are sequentially updated at timesteps {

tn}, where

tn =

nτAO and

n=0,1, …, is number of sequential updates of the controls. It is expected that the duration

τAO between control updates at each AO control cycle is considerably shorter than the characteristic correlation time

τatm of atmospheric turbulence-induced phase aberrations (

τAO <<

τatm). The correlation time

τatm, also referred to as the atmospheric turbulence “frozen” time, depends on such factors as atmospheric turbulence strength, laser beam propagation geometry, cross-wing speed, and target velocity. For laser beam projection onto a stationary target

τatm typically ranges from one to approximately one to ten milliseconds [

15,

16].

In the simplified piston DM model used in the numerical simulations, the phase modulation

was considered as a static (time independent) function during each

n-th AO control cycle (between the

n-th and

n+1-st updates of DM controls):

Here

are phase modulation amplitudes resulting from the applied controls

,

are DM actuator sensitivity coefficients, and

are the DM response functions. For simplicity we further assume the piston DM model with identical actuator sensitivity coefficients

and stepwise response functions

equal to one inside and zero otherwise of the corresponding DM subapertures of area

ssub. It was also assumed that the actuator response time

τDM is distinctly smaller than

τAO and, for this reason, was not accounted for in Eq. (2). However, in practical AO systems the response time

τDM could be an important factor defining and/or limiting the AO control cycle duration

τAO and, hence, the frequency bandwidth

fAO of the closed-loop control system. As a point of reference for piston-type (e.g., push-pool piezo, or dual-frequency LC cell-based) actuator response time estimation we consider

=50 μs, which corresponds to the open-loop frequency bandwidth

fDM =20 kHz [

10]. Note that piston phase control in coherent (phased) fiber array type BD systems can be performed with up to and above GHz-rate [

17].

In the numerical simulations, performance of the DE-LBP system with a SAPCO-AO controller utilizing the piston DM was compared with the corresponding performance of a hypothetical (ideal) phase-conjugate (PC) AO system having infinitely high resolution in wavefront sensing and control, referred to here as the “ideal” phase-conjugate (IPC) AO system. The IPC phase pre-compensation can be represented in the form [

9,

14]:

where both the outgoing beam phase

and turbulence-induced aberration of the beacon beam

are defined inside the BD transceiver aperture.

In the case of the SAPCO-AO control system considered here, the PC-type wavefront phase aberration pre-compensation algorithm can be described by the following iterative procedure for the control signal update:

where {

} are estimations of piston phases of the optical field entering the WFS computed during the n-th control cycle. Note that diacritic tilde symbol is used here and underneath to distinguish optical field characteristics obtained based on phase retrieval computations.

The piston phase estimations in Eq. (4) can be defined by the following expressions:

where the function

represents estimation of the “true” residual (uncompensated) phase

[Eq. (1)] at the SAPCO sensor input plane during the

n-th control cycle. The function

in Eq (5) is obtained in course of phase retrieval computations completed at time

prior to the next update of controls. The time

accounts for computation of the controls

and their transfer to the DM actuators. Per benchmarking results conducted for

nDM =32 this time (on the order of

5 μs) represents a small fraction of the AO cycle duration

τAO and for this reason was neglected in numerical simulations presented here. Note that since

τAO <<

τatm, the “true” phase aberration

does not noticeably change between sequential update of controls and, hence, can be considered as static (“frozen”):

.

Definition of piston phase estimations {

} in Eq. (4) through the retrieved phase

averaging over DM subaperture areas, as described by Eq. (5), may not be the best possible option. Under strong intensity scintillation conditions, the turbulence-induced phase aberration and, hence, the retrieved phase

may contain a considerable number of topological singularities (branch points and 2π phase cuts). Some of these phase singularities can be collocated with the DM subapertures resulting in ambiguity piston phase estimation based on Eq (5), unless the function

is preliminarily unwrapped [

18]. However, phase unwrapping may be a challenging computational task especially with presence of noise resulting from phase retrieval calculations and rapid growth in the number of phase singularities with turbulence strength increasing [

19]. In addition, phase unwrapping requires additional computational time leading to the need for additional

τAO increase and corresponding decline in the AO control operational frequency bandwidth.

The ambiguity issue in piston phase estimations can be addressed by utilizing the following expression for computation of piston phases in the control algorithm (4) which is insensitive to the presence of phase singularities:

where

and

correspondingly are the estimations of the received optical field complex amplitude and intensity at the SAPCO sensor input plane. These estimations can be obtained using the Fienup hybrid-input-output (HIO) complex field retrieval algorithm described in Part I (Ref [

1]). A similar approach for computation of piston phases was proposed in Ref [

20].

As numerical simulations show (see

Section 2.5) utilization of PC-type control algorithm (4) with computation of the piston phase estimations based on Eq. (6) results in faster AO control process convergence, which is especially noticeable under strong scintillation conditions. For simplicity we further refer to the control algorithm Eq. (4) without specifying the exact formula [either Eq. (5), or Eq. (6)] used for piston phase computation, unless this difference is an important issue to be addressed. We also solely use the term “phase retrieval” even in conjunction with the computation of piston phase estimations [Eq. (5) or Eq. (6)] based on the HIO complex field retrieval algorithm.

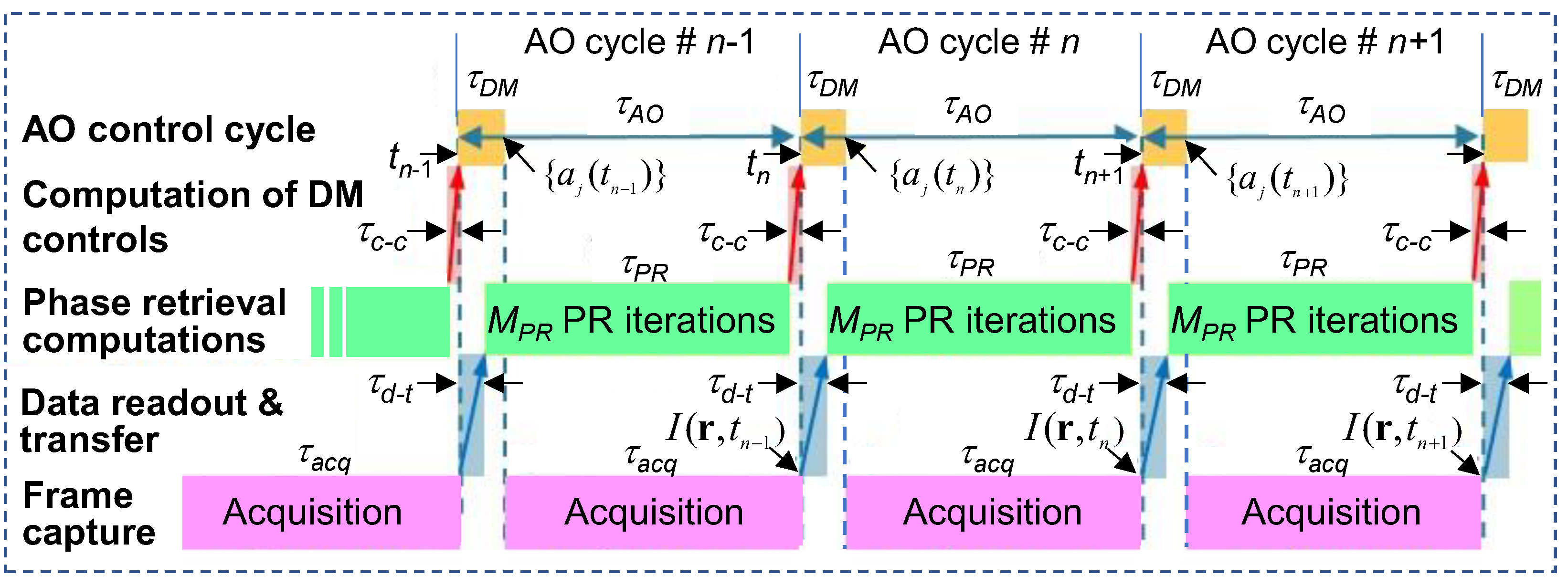

To conclude analysis of the SAPCO-AO control system model, consider the time diagram shown in

Figure 2, that illustrates three sequential AO (DM controls update) cycles. Here the controls

applied to the DM actuators at timestep

tn+1 are computed using Eq. (4). These controls depend on the estimation of residual phase

[or complex amplitude

] obtained during the preceding (

n-th) control cycle. In its turn the function

[or

] is computed during

MPR iterations of the HIO phase retrieval algorithm (HIO iterations). These HIO iterations are based on processing of the output intensity distribution

of the SAPCO WFS which is acquired by the photo-array during the preceding (

n-1)-st AO control cycle.

As the time diagram in

Figure 2 shows, the intensity acquisition process starts at the timestep

tn-1 delayed by the DM actuator response time

, and continues until the next (

n-th) DM control update. This enables maximization of photo-array integration time

during the AO control cycle and, therefore, the SNR improvement.

Intensity data readout and transfer to the phase retrieval processor are synchronized with control signal update at the

n-th AO control cycle and occur during the time interval

, as shown in

Figure 2. To increase the time

available for phase retrieval computation, the HIO iterations start after the completion of data readout and transfer, that is with the delay by

. For

estimation assume that the intensity

is acquired by a photo-array having 256 x256 pixels with 12-bit data resolution. With a commercial area-scan photo-array (e.g., from 1st Vision) and fast interface [e.g., CoaXPress, (Ref [

21]), or Camera Link (Ref [

22])] providing up to a 50Gbit/s data transmission rate, data readout and transfer would take approximately

30 μsec, or even less.

The major parameter defining the SAPCO-AO control cycle duration τAO is the time required for phase retrieval (PR) computations. This time depends on the pre-selected number of PR iterations MPR conducted between subsequent DM control updates and the computational time τit needed to perform a single PR iteration. Parameter MPR increase leads to a more accurate estimation of the residual phase aberration at the WFS input plane and is therefore desired, but on the other hand this also results in an undesirable increase in control cycle duration τAO.

For a reasonably realistic estimation of the time scales

and

τAO , consider results of PR iteration time

benchmarking conducted for the SAPCO WFS configuration using a commercial gaming computer with a single GPU (see

Section 3.2 in Part I, Ref. [

1]). Phase retrieval computations performed using a numerical grid with resolution

NPR =256 (256x256 pixels) resulted in

τit =133 μs. By accounting for the additional time required for data readout and transfer (

30 μs) and controls computation (

5 μs), for the shortest AO cycle with

MPR=1 we obtain

170 μs. This suggests that the expected AO cycle duration

considerably exceeds the characteristic times

,

and

, which for this reason were not accounted for in the described SAPCO-AO numerical model and M&S discussed below.

In principle, the phase retrieval iteration time τit and, hence τPR can be significantly (up to several fold) decreased with transitioning to specialized (e.g. FPGA-based) signal processing hardware. Nevertheless, this may not result in the intended increase in the closed-loop AO control system bandwidth frequency fAO without corresponding decreases in the DM actuator response () and data readout / transfer () times. Additionally, for a low power beacon the major limiting factor in τAO decrease could be insufficiently long (for achieving acceptable SNR) acquisition time τacq of the WFS output intensity . The issues mentioned above are common for all A-AO system types utilizing WFSs and DMs, not just for the SAPCO-AO architecture considered here.

2.3. Mathematical and Numerical Models: Modeling and Simulation Setting

In this section we continue analysis of the mathematical and numerical models for the generic DE-LBP system based on SAPCO-AO control shown in

Figure 1. Atmospheric propagation of the monochromatic transmitted and received (beacon) optical waves can be described by the following system of parabolic equations for the complex amplitudes of the outgoing (projected)

and backpropagating (beacon)

optical waves [

14,

23,

24,

25]:

where

is the Laplacian operator,

is a random field realization describing the atmospheric turbulence-induced refractive index perturbations from the undisturbed value

n0, and

. The refractive index perturbations are assumed as statistically homogeneous, isotropic, and obey the Kolmogorov power spectrum law [

23,

25]. An identical wavelength (λ=1064 nm) is considered for both the outgoing and beacon waves in Eq. (7) and Eq. (8). This wavelength (λ=1064 nm), most common for DE-LBP applications, was also considered in analysis and M&S of remote laser power beaming (

Section 3) and FSO laser communications (

Section 4) even though latter systems are typically based on laser sources having other wavelengths (e.g., λ=1550 nm is more common for FSO communication links [

6]). The use of an identical wavelength throughout this paper was selected for easier and more consistent comparison of SAPCO-AO control performance across the applications considered. The presented results can easily be adapted for each specific application wavelength.

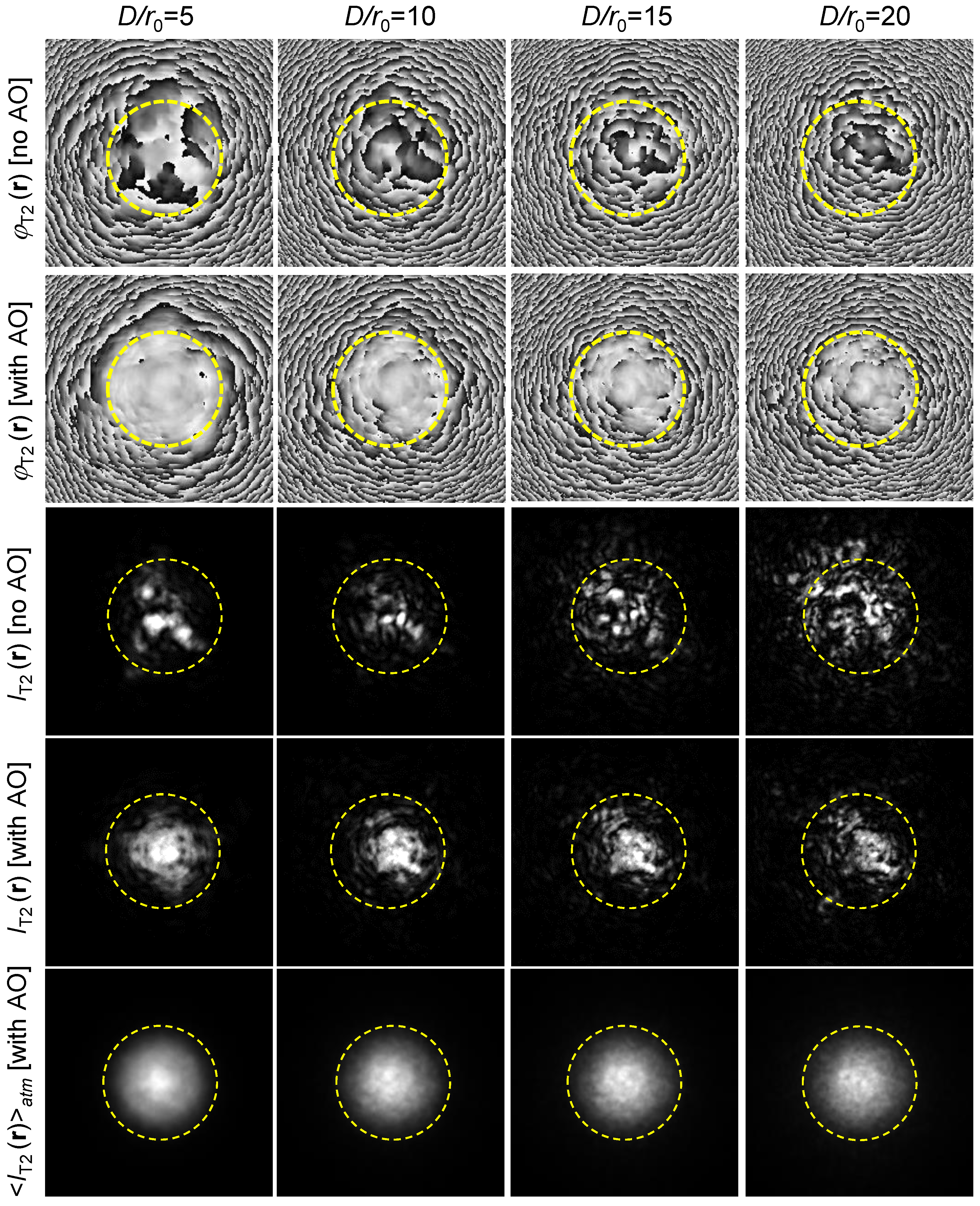

Similar as in Part I (

Section 2.2), the atmospheric turbulence impact on AO system performance is characterized here by the ratio

D/

r0 of the BD aperture of size

D to the Fried parameter

r0 (the measure of the phase aberration correlation length at the propagation path end), and the Rytov variance

describing the strength of intensity scintillations at the BD pupil plane. Both the

D/

r0 and

depend on the refractive index structure parameter

, propagation distance

L, and wavelength

λ (see

Section 2.2, Part I) [

1,

23,

24].

The complex amplitude

of the projected laser beam at the BD pupil plane (

z =0) defines the boundary condition for Eq. (7):

where

and

correspondingly are the transmitted beam magnitude and intensity distributions. For the flat-top transmitted beam considered here and in

Section 3 inside the BD aperture and zero otherwise. In the M&S the flat-top beam was approximated by a super-gaussian function of power 8 and width

D.

The controllable phase

in Eq. (9) is described by the following expression:

where the controls

are computed using the PC-type algorithm defined by Eq. (4). In the M&S the phase modulation component

in Eq. (10) was set either to zero for the operational regime without a BSM-based tip/tilt control, or

when the tip/tilt phase aberration component

of the input field wavefront phase

was completely removed prior to control update at each AO control cycle using a hypothetical (ideal) tip/tilt control system.

In numerical simulations the tip/tilt aberration component

was defined through the wavefront slope vector

corresponding to the input field complex amplitude

:

. In its turn the slope vector was represented in the form

, where

is the vector describing centroid displacement of the intensity distribution in the focal plane of a virtual ideal (infinite size, thin, parabolic) lens with a focal distance

F that can be arbitrary selected in simulations (”virtual” lens technique for wavefront slope computation [

26]). A similar approach is utilized for computation of wavefront tip/tilts within the lenslet subapertures of a Shack-Hartmann WFS [

27].

Consider now Eq. (8) describing laser beacon beam propagation from the target (

z=

L) to the BD transceiver telescope plane (

z=0). The boundary condition for this equation is defined by the complex amplitude

Where and are the beacon beam intensity and phase distributions.

In M&S of the DE-LBP AO system we considered a collimated [=const] super-gaussian beacon beam of width db = 0.25dAiry located a distance L= 5 km from the BD transceiver telescope. In the absence of turbulence, the beacon beam footprint size at the transceiver plane (z=0) was approximately two-fold larger than the BD aperture size (D = 30 cm) and two-fold smaller than the physical size of the simulation area corresponding to a 120-cm square with approximately =2.34 mm pixel size.

The propagation Eq. (8) with the boundary condition (11) defines the complex amplitude

of the entering BD received wave, which can be represented in the following form:

where

and

are the input wave intensity and phase distributions. In its turn the input field phase

includes an independent on turbulence (static) phase component

that is defined by beacon beam propagation geometry and the turbulence-induced phase aberration component

, that is

. In the DE-LBP model considered here the static phase represents a parabolic phase corresponding a spherical wave originated at the laser beacon location. It is assumed that this phase component is compensated within the transceiver telescope optical assembly, so the complex amplitude of the optical field entering WFS can be represented in the form:

where

is intensity distribution inside the WFS aperture diaphragm described by the window function

(step-wise function within a square of size

DWFS), and

. Here we accounted for the controllable phase modulation [Eq (10)] introduced by the DM and BSM inside the BD optical train.

Mathematical model describing transformation of the complex amplitude

[Eq. (12)] inside the SAPCO WFS resulting in the output intensity distribution

captured by the sensor photo-array during

n-th AO control cycle is presented in Part I (see

Section 2.3 in Ref. [

1]) and for this reason is omitted here. In summary, the mathematical model of the DE-LBP system with SAPCO-AO control used in numerical simulations includes:

- (a)

the beacon beam propagation equation [Eq. (8)] with the boundary condition [Eq. (11)];

- (b)

expressions defining the controllable phase [Eq. (9)] and the complex amplitude of the entering WFS field with complex amplitude [Eq. (12)];

- (c)

wavefront phase aberration pre-compensation algorithm describing sequential updates of controls [Eq. (4)] with options [Eq. (5) or Eq. (6)] for computation of piston phase estimation ,

- (d)

the HIO phase retrieval (PR) algorithm applied for the SAPCO WFS optical configuration model described in Part I (see sections 2.3-2.6 in Ref. [

1]) providing the estimation

of the entering WFS complex amplitude in a set of

MPR phase retrieval (PR) iterations conducted for each

n-th AO control cycle, which is needed for computation of piston phase estimations in the control algorithm, and

- (e)

propagation equation [Eq. (7)] for the projected laser beam with the boundary conditions [Eq. (9)] enabling computation of the target-plane intensity distribution and efficiency assessment of the SAPCO-AO control via computation of laser beam projection performance metrics.

In M&S the numerical integration of Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) with boundary conditions defined by Eq. (9) and Eq. (11) was performed on a computational grid with resolution

Natm =512 (512x512 pixels) using the wave-optics (split-step operator-based) technique (Ref [

24,

28]). The central part of this grid with resolution

NPR =

Natm /2 and scaled by factor

MD = 84.4 pixel size, was used for HIO phase retrieval computations. The area of the SAPCO WFS square aperture diaphragm of size

DWFS was represented on the grid with resolution

NWFS =128.

As in Part I (Ref. [

1]) turbulence-induced refractive index inhomogeneities along the propagation path for both the beacon and transmitted laser beams were represented by a set of

Nφ =20 equally spaced 2D random thin phase screens corresponding to the Kolmogorov turbulence power spectrum. The combinations of

Nφ mutually uncorrelated phase screens are referred to here as turbulence realizations.

To simulate cross-wind impact on SAPCO-AO control system performance, numerical integration of Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) was conducted in a sequence of timesteps. For convenience, the time interval Δt between sequential timesteps was set equal to the shortest AO cycle duration τAO corresponding to single PR iteration (MPR= 1): Δt = τit =133 μs. The overall number of time steps was set to be sufficiently large to ensure SAPCO-AO control process convergence, or (in the absence of convergence) to reveal general trends in the cross-wind impact on DE-LBP system performance.

For M&S of cross-wind-induced effects we assumed validity of Taylor’s “frozen” turbulence hypothesis [

15,

29]. Correspondingly, phase screens were shifted along the

ox axis (wind speed direction) at each timestep by the number of grid pixels dependent on the cross-wind velocity

v0. Note that numerical analysis of DE-LBP system performance in the presence of strong cross-wind (and/or in operation with a fast-moving target) may require phase screen shifts over number of pixels exceeding the computational grid size. To preserve continuity in phase aberrations for these operational scenarios, turbulence phase screens were generated inside a 4x-elongated (along the

ox-axis) computational area. These elongated phase screens, also referred to as “infinitely-long” turbulent phase screens (Ref. [

30]), were continuously regenerated with sequential phase screen shifts. The mathematical and numerical models presented in this section describing the DE-LBP system with SAPCO-AO controller are equally applicable (and were further used) for analysis of AO control in remote power beaming and FSO communication systems (with a few minor adjustments described in corresponding sections of this paper).

2.4. Performance Metrics

Performance of the SAPCO-AO based DE-LBS system was evaluated using the following measures (metrics):

- (a)

Phase error metric

characterizing residual (uncompensated) phase aberration

within the WFS aperture diaphragm as described by the window function

. The phase error metric computed during sequential updates of the DM controls was defined as:

Similar to performance measures used for analysis of PR algorithms in Part I (see Section 2.7), the metric (13) is insensitive to modulo 2π phase jumps in the residual phase. The phase error metric values depend on the pre-selected set of SAPCO-AO control system parameters including resolution of the piston DM (nDM), geometry and parameters of the SAPCO WFS, chosen number of HIO iterations MPR, etc. It is also convenient to represent in Eq. (13) as function of either the number of sequential control signal updates [], or as a function of the normalized time or .

The metric (13) solely characterizes AO control system performance in mitigation of phase aberrations within the WFS aperture diaphragm, and only indirectly the overall DE-LBP system effectiveness in maximization of projected laser power density at the target plane. The latter characteristic is influenced by several additional factors, including the BD transceiver telescope and projected laser beam parameters (e.g., BD type, aperture size, beam intensity and phase distributions), propagation geometry (e.g., distance and elevation of the BD transceiver and target), and turbulence strength and distribution along the propagation path (turbulence profile). For this reason, the overall laser beam projection efficiency with SAPCO-AO control was evaluated in the M&S using the target-plane power-in-the-bucket (PIB) metric, that combines the impact of all the factors mentioned above.

- (b)

-

The PIB metric

[or equivalently

, or

, or

] was defined in M&S as the projected laser beam power (normalized by the overall transmitted beam power

P0) inside the target-plane on-axis circle [bucket

] of diameter

:

For comparison, we also computed the PIB metric values and corresponding to the IPC control algorithm [Eq. (3)] utilizing either a hypothetical DM having “infinitely” high resolution (numerical grid resolution nWFS=128 in the M&S setting used), or the PC-type control algorithm [similarly to Eq. (4)] for a system with a piston DM composed of NDM =nDM x nDM actuators . In the latter case the controls were defined as , where the piston phases were computed using the following expression [analogous to Eq. (6)]: (j=1,…,NDM). Metric characterizes the performance that can be theoretically achieved with an ideal PC-type control system under specified turbulence conditions. On the other hand, represents a maximum PIB metric value achievable with a selected piston DM comprised of nDM x nDM actuators.

Both metrics and depend on the specific turbulence realizations along the propagation path used in the M&S. For performance assessment in statistical terms the metrics and were computed in a set of Ntrial =100 adaptation (AO) trials. Each trial was composed of Nupdate sequential DM control updates, began with zero controls and conducted using statistically independent atmospheric turbulence realization for each trial. The AO trials resulted in computation of Ntrial dependences and characterizing AO process time evolution for selected turbulence conditions, which were averaged over adaptation trial numbers. The obtained dependences and referred to as atmospheric-averaged performance metric adaptation curves, were further used for both SAPCO-AO control efficiency assessment under specified turbulence conditions and for optimization of the control system parameters.

2.5. SAPCO-AO Control System Parameter Optimization

Performance analysis of the DE-LBP system in

Figure 1 (as well as the remote power beaming and FSO communications systems in

Section 3 and

Section 4) requires initial setting of SAPCO-AO control system characteristics including:

-

Selection of an initial estimation (defined by the superscript m=0) for the complex amplitude of the field entering the WFS to be used as an initial condition for MPR HIO phase retrieval (PR) iterations conducted at each AO control update timestep {tn} (n=0,1,…). The following two options, referred to here as “Reset” and “Preceding AO cycle,” were examined through M&S. In the first “Reset” case initial estimations for the magnitude were always (for all timesteps) set to a constant, while for the initial phase estimations we used statistically independent (for each n) random 2D realizations of a delta-correlated field with zero mean and uniform probability distribution inside the interval [-π, π].

In the “Preceding AO cycle” case, the complex amplitude

computed at the end of the preceding (

n-1)-st AO control cycle (after completion of

MPR PR iterations) was used:

. Both PR initial condition options are described in more detail in Part I (

Section 2.6), Ref [

1].

Selection of either Eq. (7) or Eq. (8) for computation of piston phase estimation in the control algorithm (6).

Selection of how many PR iterations MPR per AO control cycle should be performed to minimize the overall adaptation process convergence time τconv and hence increase the AO control system closed-loop frequency bandwidth fAO =1/ τconv. The AO process convergence time τconv = Mconv τit is defined here through the overall number of PR iterations Mconv or the corresponding number Nconv = Mconv / MPR of sequential control updates, which are required to achieve a pre-selected threshold value of the atmospheric-averaged PIB metric: . In the M&S the threshold was set to 90% of the maximum atmospheric-averaged PIB metric value achieved during AO control trials composed of Nupdate =20 control updates: , where and Ttrial = Nupdate τAO = Nupdate MPR τit.

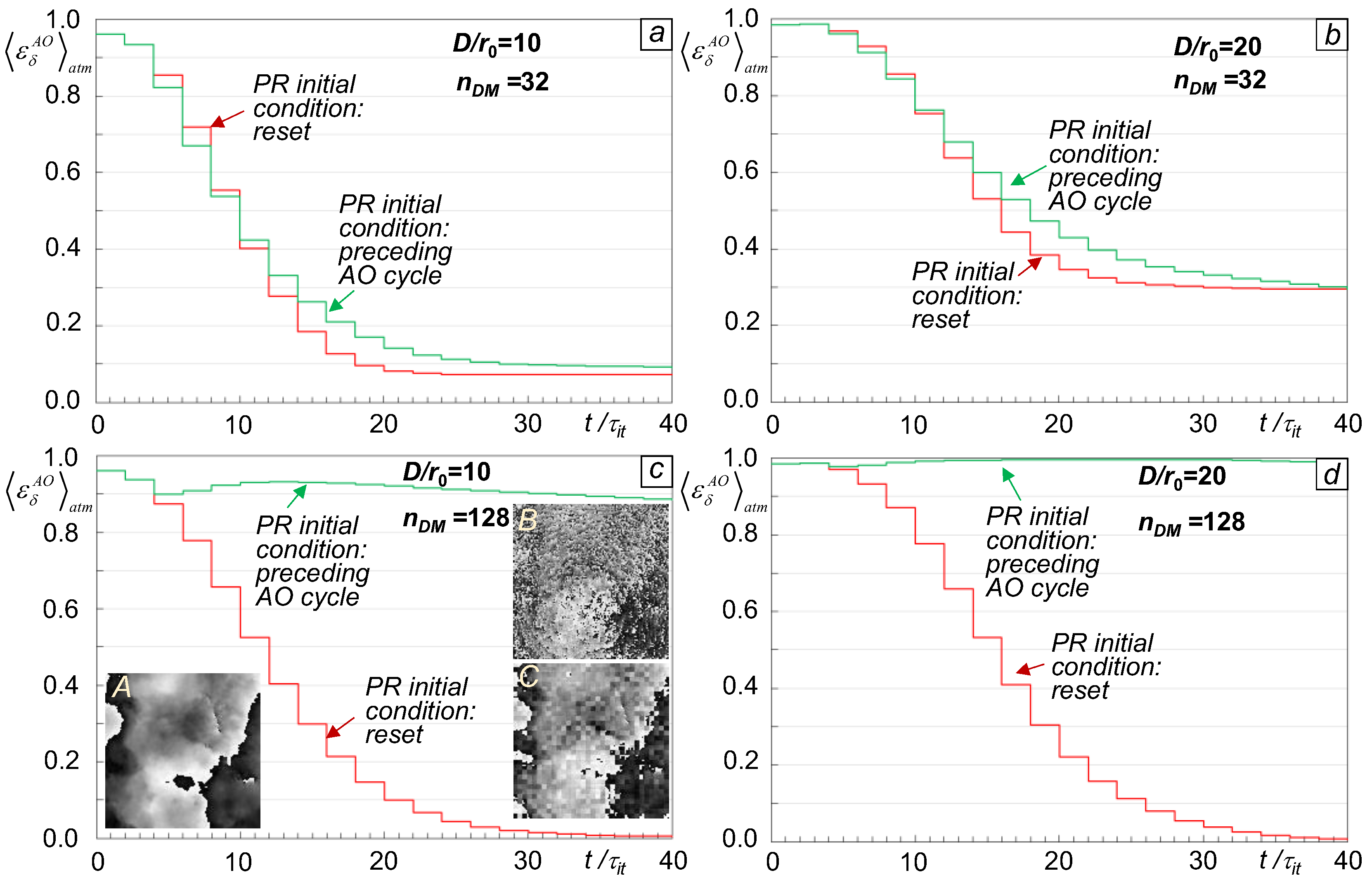

To choose between the “Reset” and “Preceding AO cycle” options consider the time-evolution dependencies

shown in

Figure 3 illustrating the dynamics of atmospheric-averaged phase error metric evolution during sequential control updates for both PR initial conditions. Notice the monotonic decrease (convergence) of the phase error metric

independent of the pre-selected PR initial condition for the piston DM with

nDM =32. On the contrary, in the case of a higher resolution DM (

nDM =128), AO process convergence occurred only for the “Reset” PR initial condition as shown in

Figure 3 (c, d). The “Reset” option also provides faster convergence and smaller residual phase error for all cases considered in

Figure 3. For this reason, the “Reset” PR initial condition was used in all numerical simulations described below.

The reason why an intuitively preferable “Preceding AO cycle” PR initial condition option, which should take advantage of PR computations conducted at the preceding control cycle, resulted in less stable and slower AO process convergence can be explained by considering the characteristic spatial structure of the phase estimations

obtained after the few first PR iterations at each

n-th control update cycle. These phase estimations are commonly characterized by the presence of strong digital noise that gradually decreases with increasing

m (

m=1,…,

MPR). With selection of the “Preceding AO cycle” option with a small PR parameter

MPR (e.g.,

MPR =1 or

MPR =2 as in

Figure 3) the digital noise in the phase estimations

obtained at the end of the PR iterations remains strong and, hence, negatively affects the controllable phase

for the following control cycle. This results in digital noise “propagation” through sequential AO control cycles potentially leading to slowing of the AO process convergence or even instability.

To illustrate, consider the grey-scale insert images in

Figure 3 (c). The image “A” presents a characteristic example of initial phase aberration

at the WFS aperture diaphragm for

D/

r0 =10 and

. The corresponding phase estimation

obtained after two sequential PR iterations and shown in image “B” exhibits a clearly visible presence of digital noise. The impact of this noise is less obvious in the controllable phase

(image “C”) for DM with

nDM =32. The noise decrease in image “C” occurs due to averaging of the noisy phase estimation pattern

(image “B”) over the DM subaperture areas. This averaging takes place in computation of the piston phases [Eq. (5)] and the corresponding controllable phase

[Eq. (4)].

The higher the DM resolution, the less efficient is the subaperture averaging-based digital noise suppression. With selection of the “Preceding AO cycle” option, small

MPR, and a high-resolution DM, the digital noise increases through consecutive AO cycles leading to possible AO control instability, as in the case shown in

Figure 3 (c, d) for

nDM =128. On the other hand, the “Reset” option prevents such digital noise amplification through DM control updates and for this reason is preferable. As already mentioned, the digital noise component gradually decreases with

MPR increase and for this reason is desired. At the same time parameter

MPR increase for better digital noise suppression leads to an unwanted increase of the AO control cycle duration

τAO.

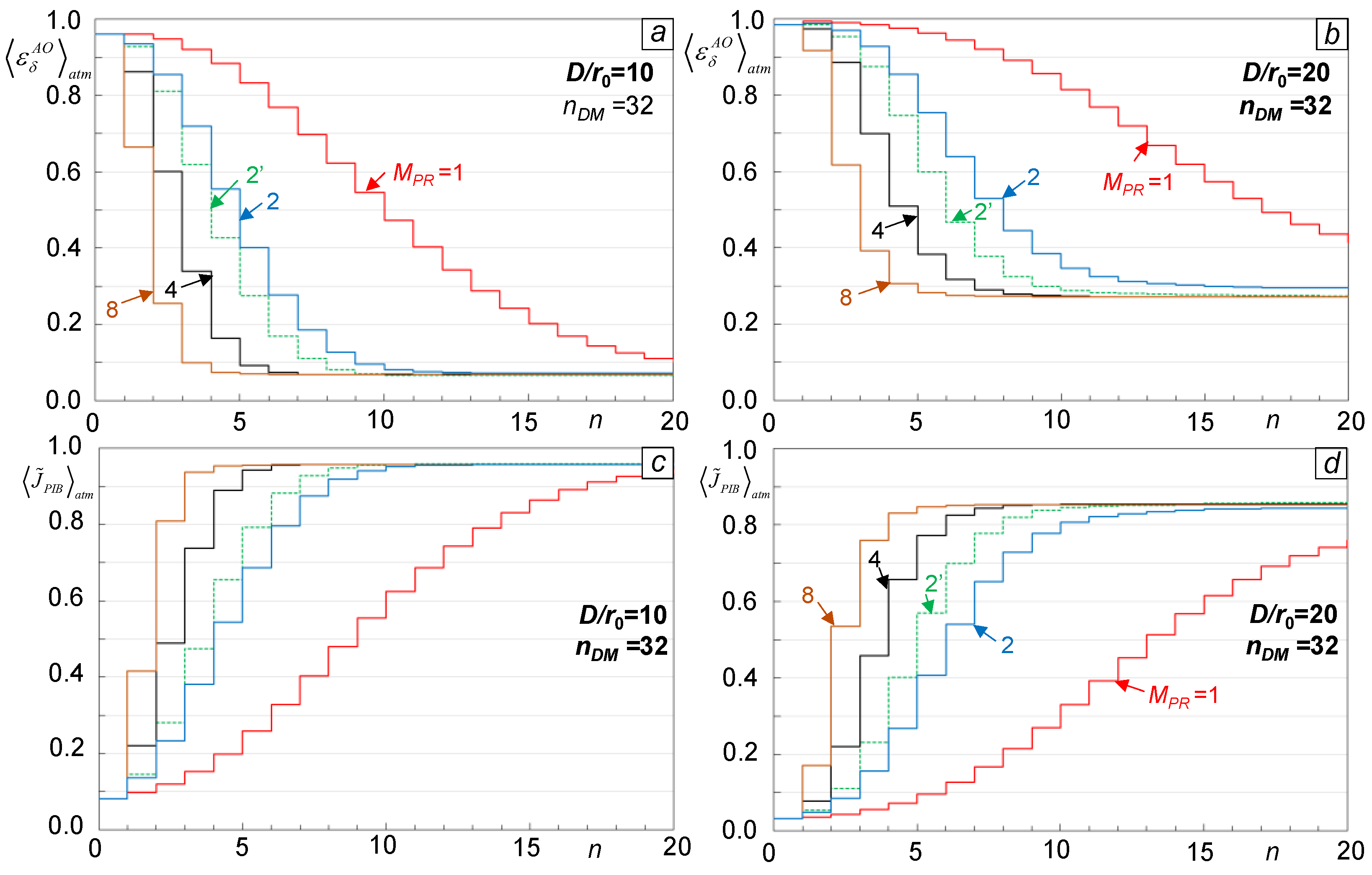

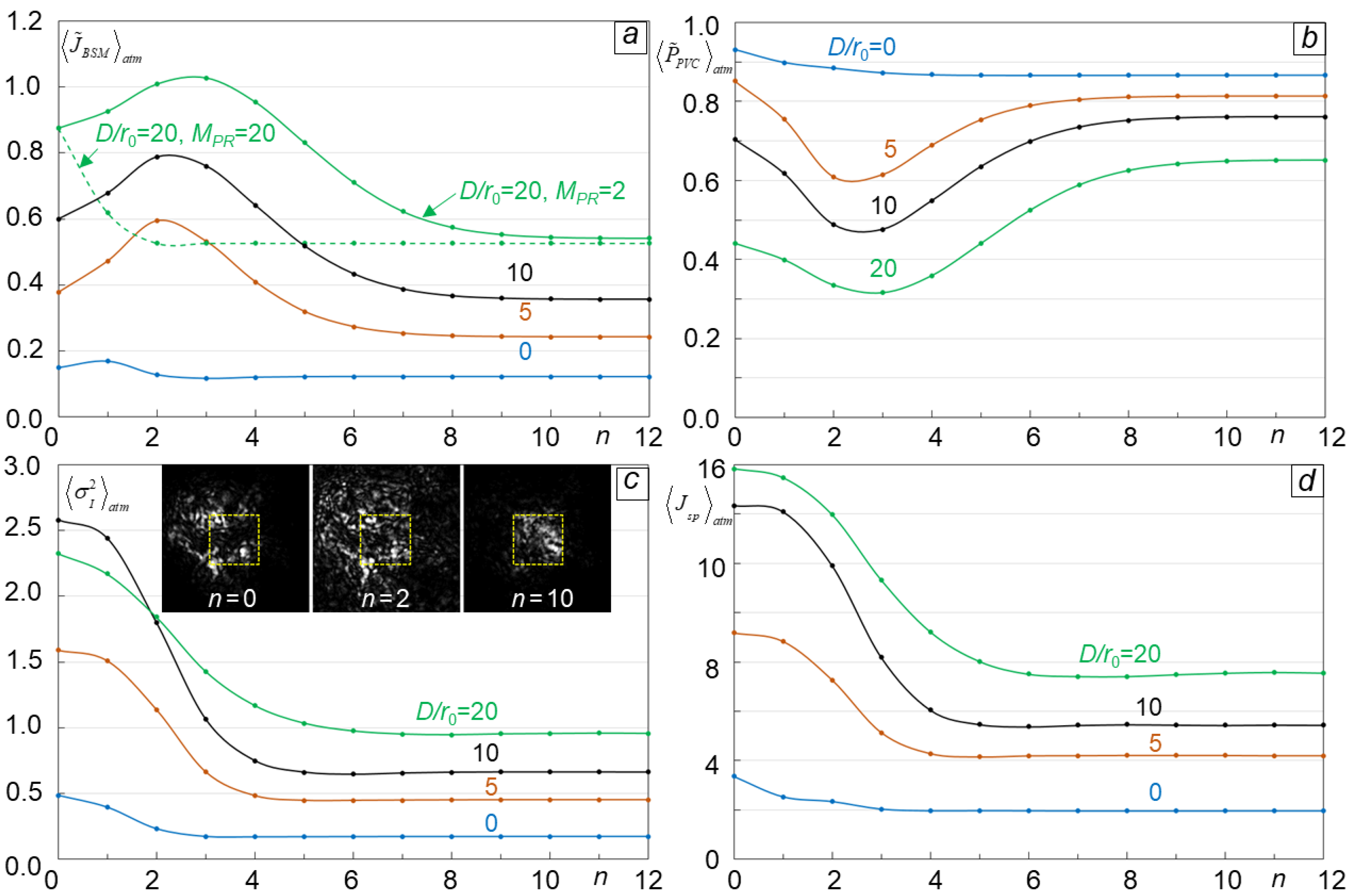

To investigate tradeoffs in parameter

MPR selection for the SAPCO-AO control system, consider dependencies of the atmospheric-averaged residual phase error

shown in

Figure 4 (a),(b) and the corresponding normalized PIB metric

computed for

in

Figure 4 (c), (d) on the consecutive control update number

n, computed for different parameter

MPR values. As expected, the increase in the number of PR iterations per AO cycle (parameter

MPR increase), aiming to achieve better phase retrieval accuracy during each DM control cycle, resulted in a lesser number of control updates required for reaching stationary performance metric values (faster convergence in terms of the overall number of DM control updates).

As can be seen from the AO process convergence curves in

Figure 4, utilization of a single PR iteration per control update (

MPR =1) leads to noticeably slower (compared with

MPR >1) convergence for all considered M&S cases, which can be explained by the negative impact of digital noise described above. Note that for

MPR > 1 and

nDM =32 the PIB metric values

achieved at the adaptation trial end (after

Nupdate =20 control updates) are comparable with the corresponding values

for an “ideal” phase-conjugate (IPC) AO control system operating under identical turbulence conditions. The difference does not exceed 5% for

D/

r0 = 10 and 15% for

D/

r0 = 20.

The AO process convergence curves (solid lines in

Figure 4) were computed using control algorithm (4) with piston phases defined by Eq. (5), that is through the retrieved phase estimation

averaging over the DM subaperture areas. For comparison, corresponding AO process convergence curves were also computed using Eq. (6) that defines piston phases via subaperture-averaging of the complex amplitude estimation

These AO convergence curves are shown in

Figure 4 (for only

MPR =2) by dashed lines. In all cases considered, piston phase computations based on Eq. (6) resulted in faster AO process convergence, which is more evident under stronger turbulence conditions. Based on these results and, since retrieval of the phase

and complex amplitude

requires identical computational times, in all numerical simulations presented below we exclusively used Eq. (6) for piston phase computation.

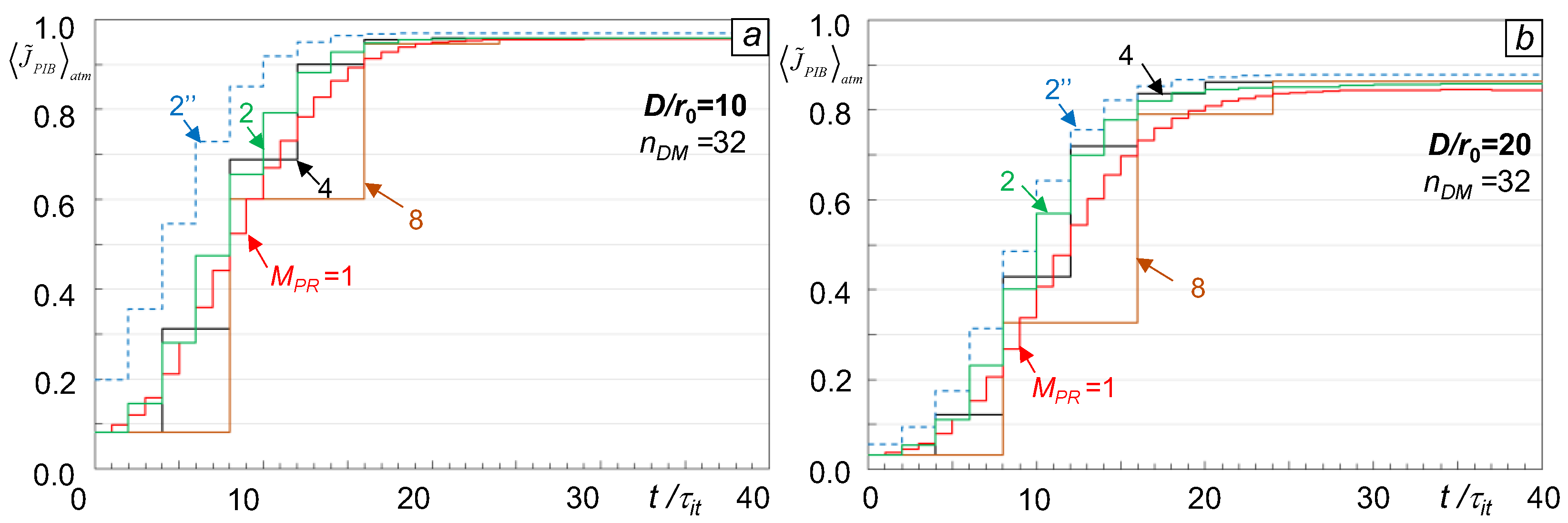

To estimate the SAPCO-AO control process convergence time

τconv and select the optimal number of PR iterations per control cycle (parameter

MPR), consider time dependencies (adaptation process convergence curves) of the normalized atmospheric-averaged PIB metric

presented in

Figure 5. The simulations were performed for M&S parameters identical to those in

Figure 4 (c, d) and with use of Eq. (6) for piston phase computation. For comparison, the dashed line in

Figure 5 (marked as 2’’) illustrates AO process convergence for the case of tip/tilt aberration removal with

MPR =2.

The results presented in

Figure 5 were utilized to estimate the adaptation process convergence time

τconv and closed-loop frequency bandwidth

fAO =1/

τconv. The threshold value

used for

τconv and

fAO estimations was set to 90% of the maximum (with respect to all examined

MPR values) atmospheric-averaged PIB metric value achieved at the end of the adaptation trials (at

).

Convergence time estimation results for several parameter

MPR values and turbulence strengths (for

D/

r0 =10 and

D/

r0 =20) are presented in

Table 1. The tip/tilt removal operational regime with

MPR =2 is indicated by

MPR =2’’. As seen from

Table 1, the fastest AO process convergence occurs with selection of two phase retrieval iterations (

MPR =2) between sequential control updates for both turbulence conditions examined. Tip/tilt aberration removal results in approximately a 1.2-fold faster convergence for

D/

r0 =10 but does not make any difference under strong turbulence.

Using

τit =133 μs as a point of reference (benchmarked value obtained using a commercial gaming PC in Ref. [

1]) for the SAPCO-AO controller with selection of an optimal number of PR iterations per AO control cycle

MPR =2 we derive to the following estimtions:

τconv ~ 1.6 ms for

D/

r0 =10 and

τconv ~ 1.8 ms for

D/

r0 = 20. This corresponds to

fAO ~ 0.6 kHz for

D/

r0 =10 and

fAO ~ 0.5 kHz for

D/

r0 = 20. As already mentioned, the phase retrieval iteration time

τit and, hence

τAO and

τconv can be significantly decreased by utilizing specialized (e.g., FPGA-based) signal processing hardware, which makes technically feasible (unless limited by the DM actuator response time) the development of A-AO systems capable of operation in strong scintillation conditions exceeding a 1.0 kHz closed-loop frequency bandwidth.

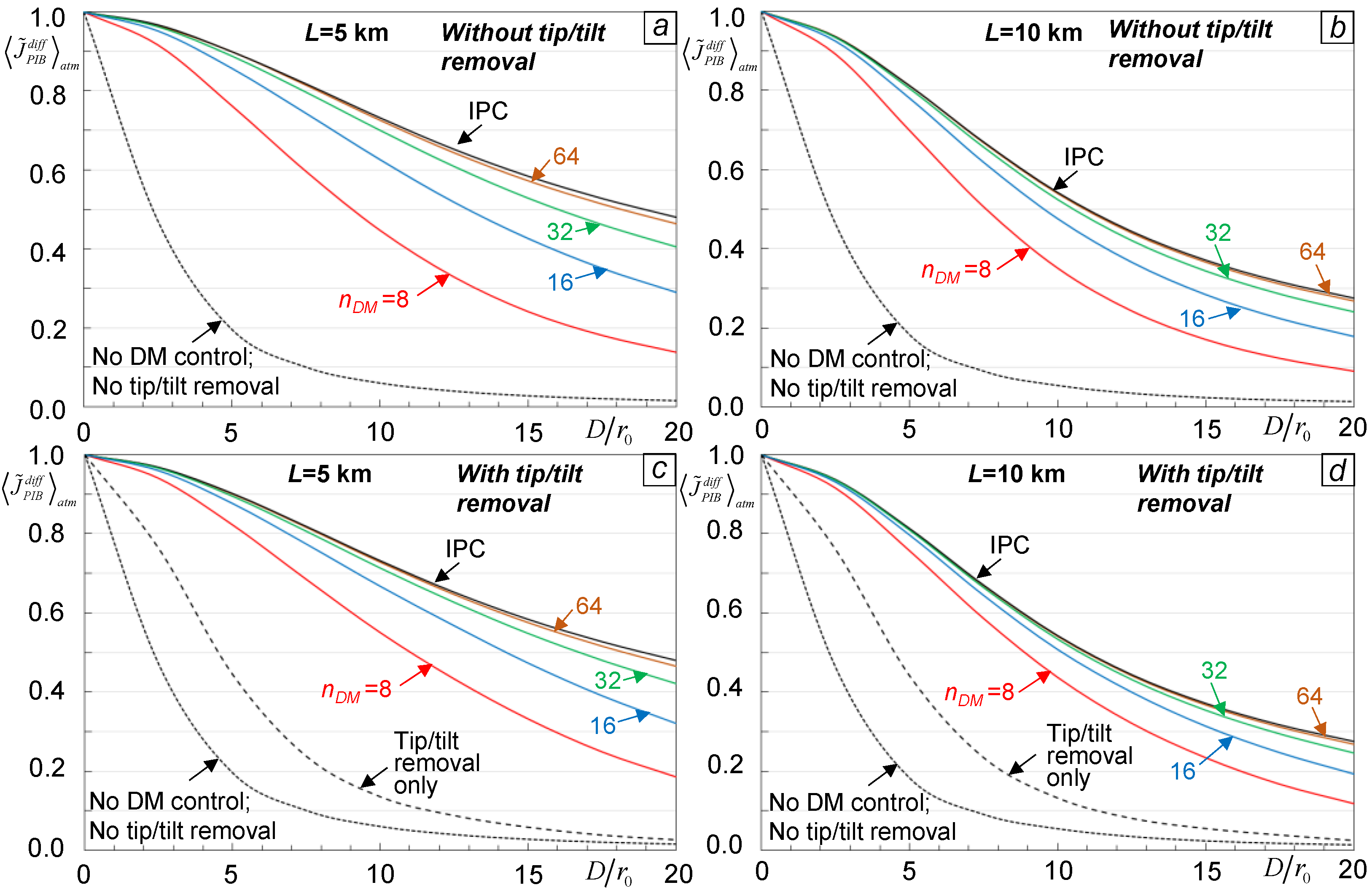

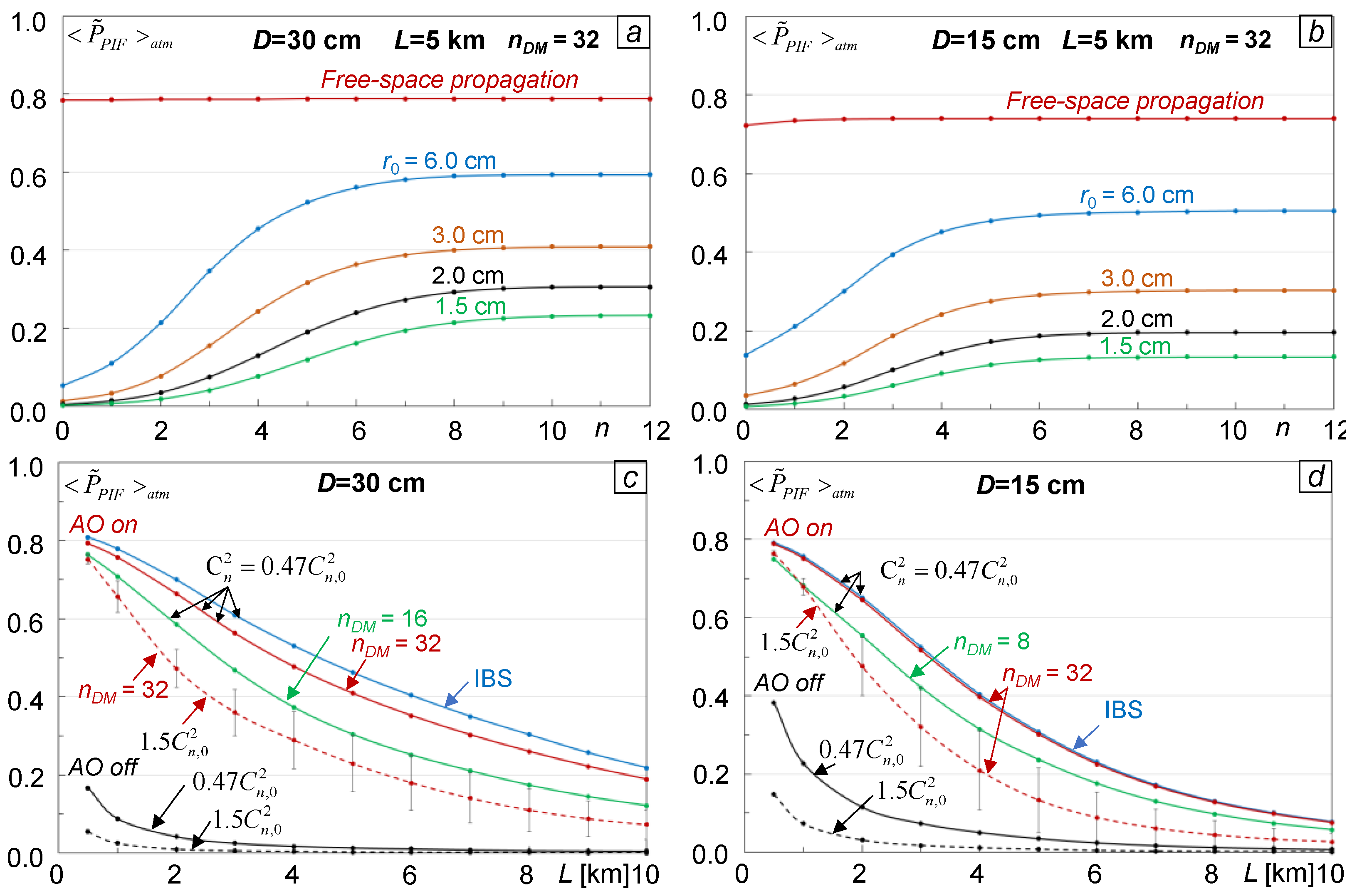

2.6. Laser Beam Projection with SAPCO-AO Control: Performance Assessment

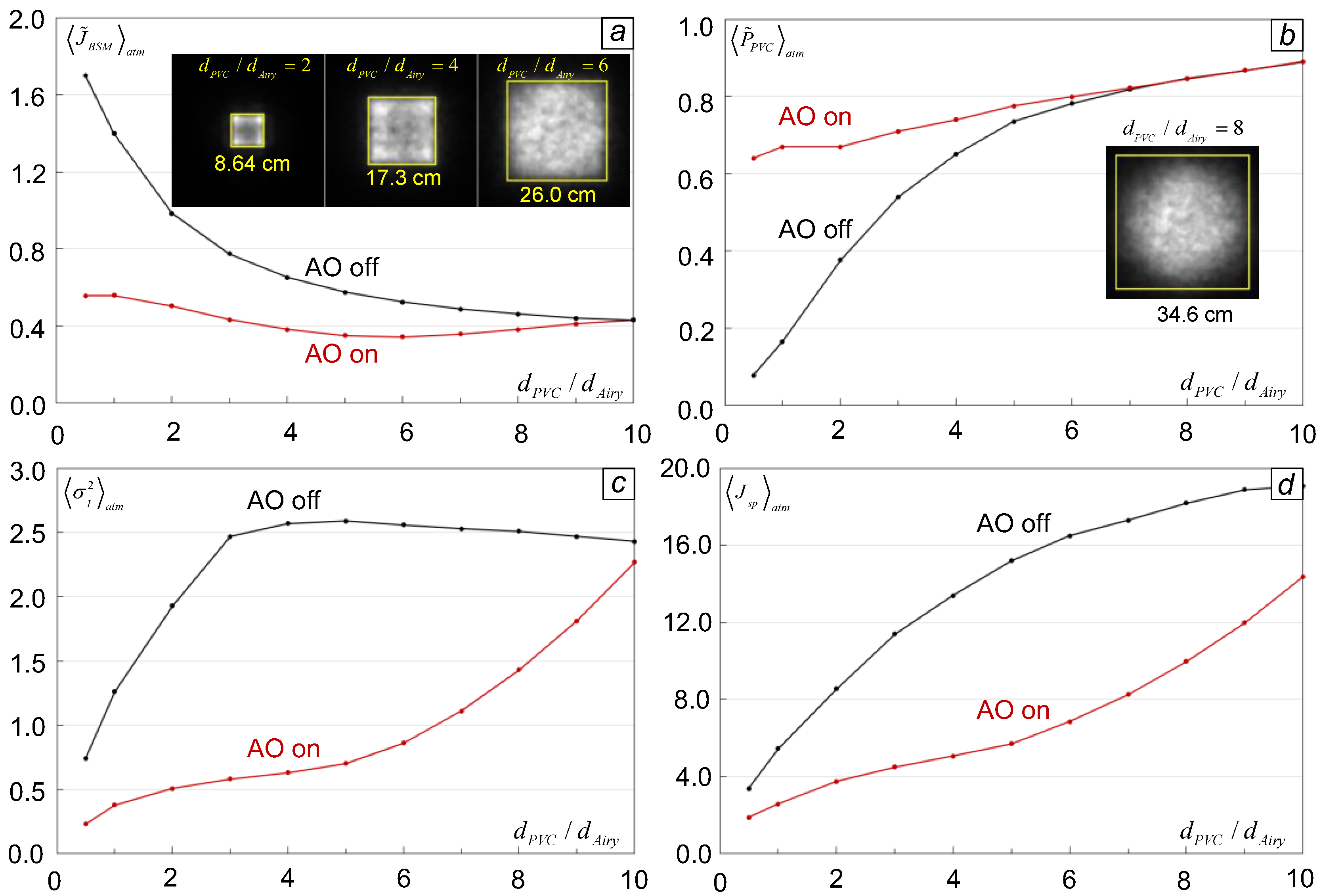

Consider how DM resolution and turbulence strength (parameters nDM and D/r0) impact efficiency of a laser beam projection system with SAPCO-AO based control. To address this question, we computed normalized atmospheric-averaged PIB metric values corresponding to the adaptation trial end (at ) for D/r0 ranging from zero (propagation in vacuum) to D/r0 =20 (strong turbulence conditions) for different parameters nDM. The normalization factor describes here the diffraction-limited PIB metric value for the transmitted beam optimally focused a distance L in vacuum. The simulations were performed for the SAPCO-AO controller conducting two PR iterations per control cycle (MPR =2). Atmospheric averaging was based on Ntrial =100 computer simulated AO control trials consisting of Nupdate =20 control updates with an overall AO trial duration of .

The M&S results are presented in

Figure 6 by the dependencies

computed for laser beam projection over distances

L=5 km (a,c) and

L=10 km (b,d) without (a,b) and with (c,d) tip/tilt aberration component removal prior to the adaptation trial start. Solid lines characterize performance of the SAPCO-AO control system utilizing piston DMs with different resolutions (parameter

nDM). The dashed and dotted curves in

Figure 6 respectively marked as “Tip/tilt removal only” and “No DM control; No tip/tilt removal” correspond to M&S trials performed without update of DM controls:

aj(

tn)}=0, (

n=0,…,

Nupdate). In the latter case (dotted curves) tip/tilt aberration components were not removed.

Compare atmospheric-averaged PIB metric values computed for the beginning (

t=0) and end (

t =

Ttrial) of the adaptation trials (dotted and solid lines in

Figure 6) with the corresponding dependencies (marked as IPC curve) obtained using the ideal phase-conjugate (IPC) control algorithm (3). The IPC curves in

Figure 6 characterize the maximally achievable atmospheric-averaged PIB metric values for a specific turbulence condition (

D/

r0 ratio), BD geometry, and beam projection engagement scenario. The relatively sharp decline of PIB metric values corresponding to the IPC control algorithm with

D/

r0 increase, which is more noticeable at a longer (

L=10 km) propagation distance, underlines the physics-based limitations of PC-based control in the mitigation of turbulence-induced phase aberrations distributed along the propagation path (volume) with a single DM.

The results presented in

Figure 6 demonstrate that with utilization of a sufficiently high resolution DM, the SAPCO-AO control approach can potentially provide a laser beam projection efficiency approaching the physics-based limitation even under strong scintillation conditions (Rytov number up to

for

L= 5 km and

for

L= 10 km). Note that even SAPCO-AO control with relatively low resolution DMs (e.g.,

nDM = 8 in

Figure 6) exhibits the potential for substantial PIB metric increase when compared with the absence of AO wavefront phase aberration pre-compensation (dotted curves). Specifically, for

nDM = 8 and under turbulence strengths ranging from moderate (

D/

r0 = 5) to strong (

D/

r0 = 20), SAPCO-AO control can lead to atmospheric-averaged PIB metric value increases by factors ranging from approximately 3.9 to 9.2 for

L = 5 km, and from 3.8 to 6.5 for

L = 10 km.

The M&S results in

Figure 6 (solid curves) also indicate that an increase in DM resolution beyond

nDM =32 has a relatively minor impact on the AO system performance while leading to a potentially significant increase in system complexity and cost. Similarly, the removal of tip/tilt aberration components with a BSM-based feedback control system results in only a relatively minor PIB metric increase, especially in strong turbulence and scintillation conditions. This conclusion can be derived from comparison of the corresponding dependencies

in

Figure 6 obtained for a SAPCO-AO system without (a, b) and with (c, d) tip/tilt aberration component removal. These results suggest that with utilization of a piston DM with sufficiently high resolution (e.g., with

nDM =8 or higher) a supplementary BSM-based tip/tilt control subsystem may not be required.

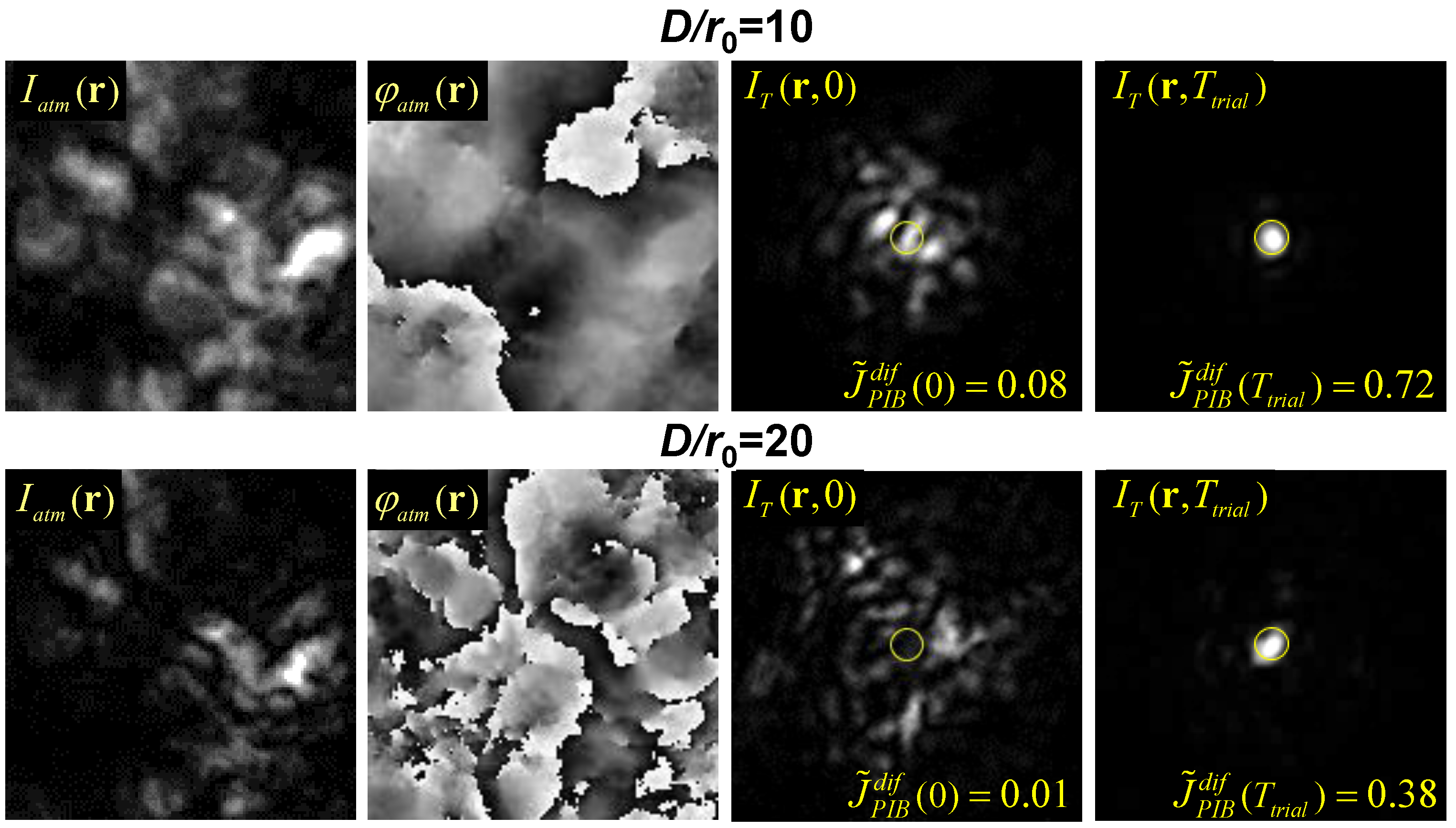

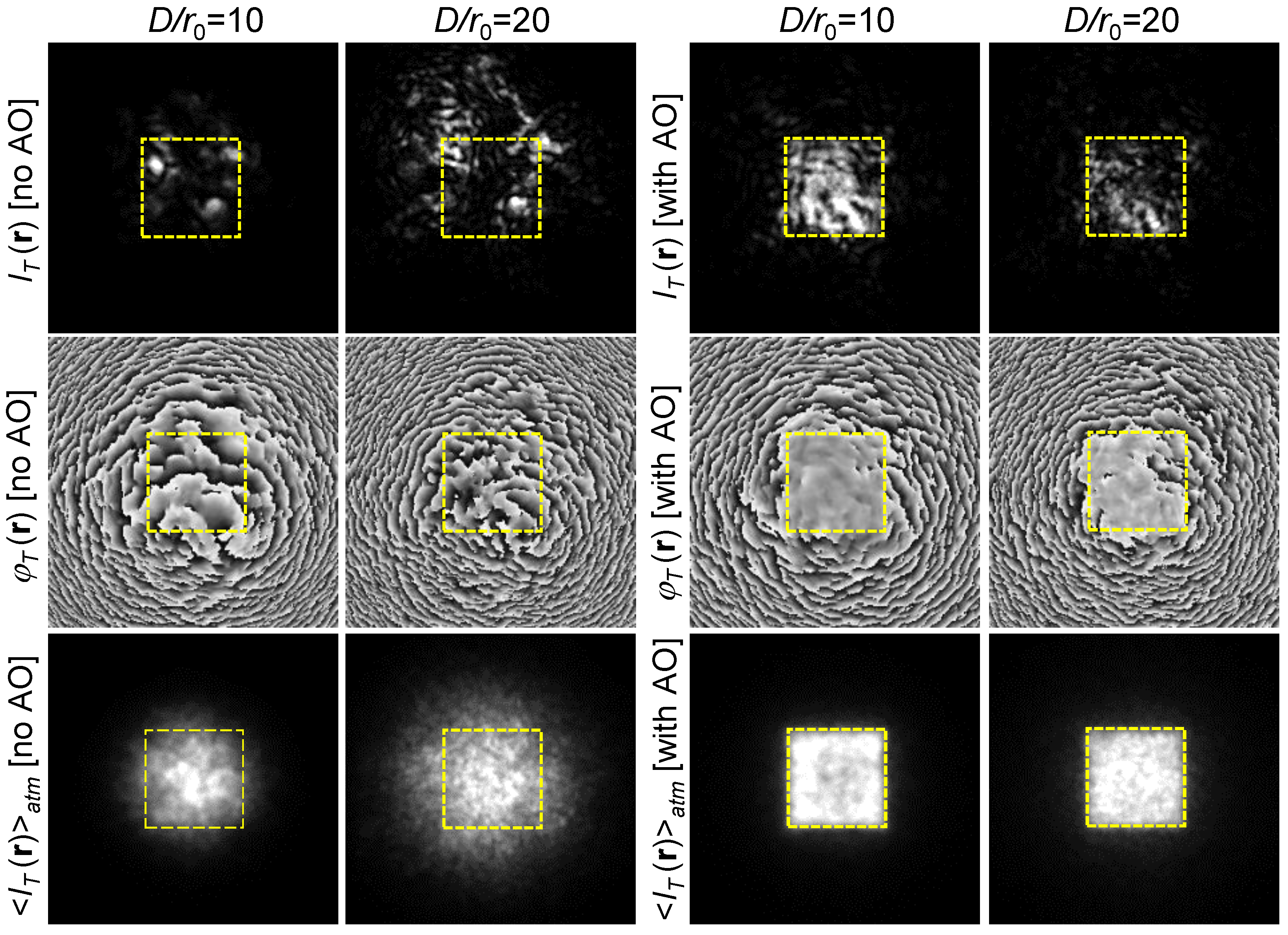

SAPCO-AO control efficiency can also be assessed by considering the grey scale images in

Figure 7 computed for a characteristic (arbitrarily selected) adaptation trial and two

D/

r0 ratio values. The initial (prior to first control update) intensity

and phase

distributions shown in the first two columns indicate the presence of strong intensity scintillations and turbulence-induced phase aberrations resulting in a broad spreading of the projected laser beam at the target plane. The corresponding target plane intensity distributions

computed for the optimally focused (propagation in vacuum) outgoing beam and identical turbulence realizations are shown in the third column.

The target-plane intensity distributions

obtained at the end of the adaptation trials (at

t=

Ttrial) for the SAPCO-AO control system with

nDM =32 are presented by images shown in the right column. As can be seen from the target plane intensity distributions and corresponding PIB metric values

and

(shown in

Figure 7 by inserts in the right two columns), AO control resulted in significant localization of the projected laser beam intensity distribution and corresponding PIB metric value increase (9-fold for

D/

r0 =10 and by a factor of 38 for

D/

r0 =20).

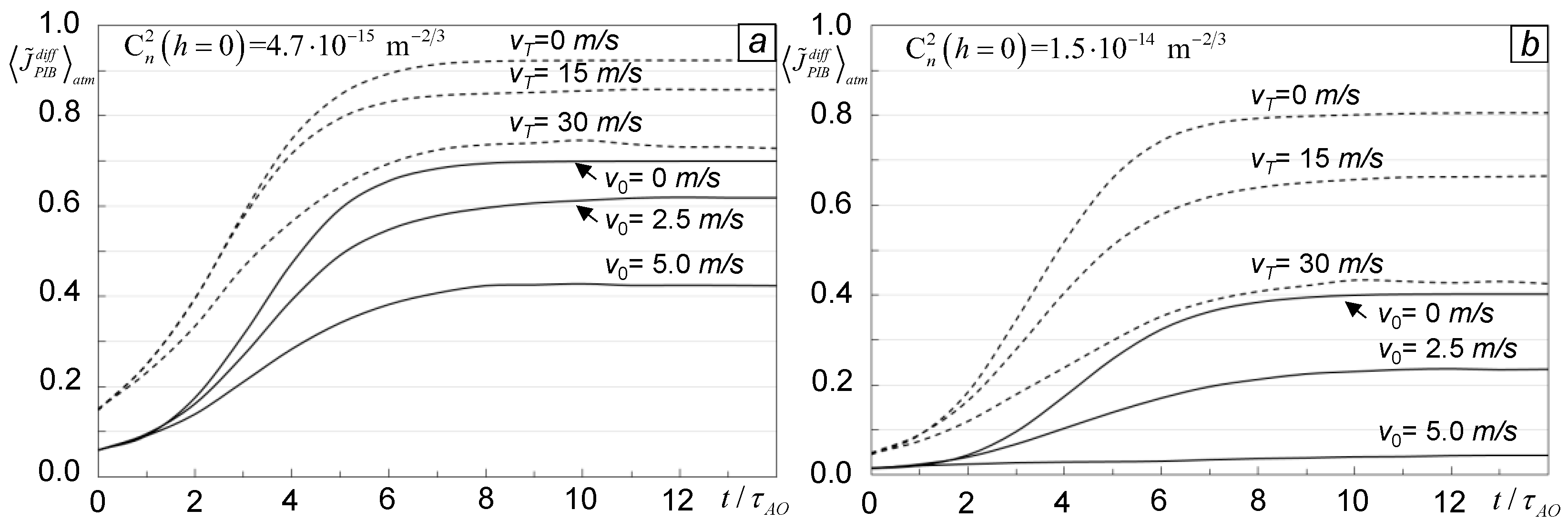

To conclude this efficiency analysis of the SAPCO-AO-based DE-LBP system, consider the impact of cross-wind induced effects. In the M&S we assumed an AO controller operating with a piston DM composed of NDM =32x32 (nDM =32) actuators. The duration of each AO control cycle was set to τAO = 300 μsec and included two PR iterations (MPR=2). Each AO control trial consisted of Nupdate =14 control updates and atmospheric-averaging was performed over Ntrial =100 adaptation trials.

Cross-wind was simulated via displacement of turbulence realizations comprised of Nφ =50 phase screens along the ox direction after each timestep. The time interval Δt between sequential timesteps was set to Δt = τit =133 μs. The displacement distance of each turbulence realization (measured in grid pixels) was dependent on the preset cross-wind velocity v0.

M&S results are presented in

Figure 8 by time dependencies of the normalized atmospheric-averaged PIB metric

computed for horizontal (solid lines) and slant (dashed lines) propagation scenarios. Simulations were performed for laser beam projection over

L= 5 km under moderate-to-strong and strong turbulence conditions corresponding to a horizontal propagation path near the ground (elevation

h=0) with corresponding ground-level refractive index structure parameter values

for

D/r0=10 in

Figure 8 (a) and

for

D/r0=20 in

Figure 8 (b).

As expected, increases in the cross-wind velocity

v0 and/or turbulence strength resulted in an overall decline in efficiency of turbulence effects mitigation and a noticeable (especially for

D/

r0 =20) increase in the AO process convergence time, as indicated by the solid lines in

Figure 8. Note that laser beam projection over the horizontal path near the ground with homogeneously distributed turbulence represents perhaps the “harshest” scenario for adaptive optics.

For practical DE-LBP applications, it is more common that the laser beam is projected onto a target moving (flying) with a velocity

vT at an elevation

H above the ground. Such laser beam projection engagement scenarios can be represented in numerical simulations by a model of cross-wind with a velocity linearly increasing along the propagation path (along the

oz-axis)

v0(

z), e.g., from

v0(

z=0)=0 at the BD pupil plane to

v0(

z=

L)=

vT at the target plane, as in the case considered in

Figure 8. For a slant propagation path, the elevation

h(

z) is linearly increased along the propagation path leading to a corresponding decrease in turbulence strength from the ground value

to

, as characterized by the refractive index parameter elevation profile

. In the M&S we used an atmospheric turbulence structure parameter elevation profile corresponded to the Hufnagel-Valley model [

31]. This turbulence strength decrease with elevation is preferred for achieving more efficient phase aberration pre-compensation with the AO-based wavefront control.

To illustrate, consider the PIB metric time-evolution curves (dashed lines in

Figure 8) computed for the target at an elevation

h = 500 m and distance

L= 5 km moving along a trajectory orthogonal to the projected laser beam propagation path (cross-target) with velocity

vT. As can be seen from the results presented in

Figure 8, with identical ground level turbulence strength [parameter

] efficiency of AO control in mitigation of turbulence effects is significantly better for slant vs horizontal propagation (compare the solid and dashed curves in

Figure 8).

As the M&S shows for the case considered in

Figure 8, removal of tip/tilt aberrations did not noticeably change AO control performance but rather resulted in an approximately 15% decrease in the adaptation process convergence time

τconv.