1. Introduction

With the continuous advancement in surgical techniques over the past decades, renal transplantation has become the foremost treatment in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). By doing so, patients are able to reduce the number of frequent hospital visits for dialysis sessions and experience a drastic improvement in the quality of life. However, the rise in prevalence leads to a growing number of patients on the transplant waiting list, an increase in waiting time, and thus, a shortage in the number of renal transplantations that can be performed. To address the increase in demand for organ donations, more options have been explored within the medical community, one of which includes utilization of pediatric en bloc kidneys for a single recipient. Given that specific criteria are met for each individual patient, this approach may effectively increase the number of donor kidneys available for transplantation without compromising the post-operative outcomes.

In addition to the conventional criteria necessary to be cleared for transplantation, providers may need to consider additional factors to determine whether one would be a good match for the pediatric donors to compensate for the size and body habitus. As such, depending on the renal mass and weight of the recipient and pediatric donor, the kidneys may be transplanted as two, which we call en bloc kidney, or traditionally as single kidneys to two separate recipients. En bloc kidney transplantation to a single recipient would indicate the anastomosis of the donor’s aorta, IVC, and ureter to the recipient’s iliac artery, external iliac vein, and bladder, respectively

[1]. Though receiving transplants from pediatric donors has been previously neglected due to technical complexities and ethical implications, multiple studies have shown that en bloc renal transplants produce comparable or even superior outcomes when compared to single renal transplants from living donors

[1,2,3].

Though there are numerous literatures published with reassuring data on single kidney transplantations from adult donors to adult recipients, that may not be the case for the topic of pediatric en bloc transplantations. Yet, we are still able to draw a conclusion from the available research data and post-operative outcomes from multiple medical centers that pediatric en bloc transplantations produces superior outcomes in contrast to single kidney transplantations from living or deceased donors. For instance, the serum creatinine levels in single kidney transplant (SKT) recipients from living donors were higher than those of en bloc kidney transplant (EBKT) at discharge, 1-year, and 5-year post-op for the majority of the patients in one of the studies done

[4]. In addition to these lab values, the average graft survival was also longer than that of single renal transplants, further highlighting the efficacy of pediatric en bloc transplantation. Thus, the following study will further explore and analyze whether the outcomes from this university medical center support the notion as presented by other institutions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a retrospective study that was done by obtaining data from the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). Clinical data consisting of donor and recipient demographics, post-operative outcomes, and complications were collected via random selection from the years 2007 to 2023 among the pediatric en bloc, adult en bloc, and single kidney transplantations from living and deceased donors.

2.2. Data Collection and Variables

First and foremost, the list of individuals who underwent en bloc transplantations was identified. The list was then divided into pediatric en bloc recipients and adult en bloc recipients, which are horseshoe kidneys from adult donors for this study. During the years 2007 to 2023, a total of 21 en bloc transplantations were performed at this university medical center – of the 21 individuals, data from a total of 17 patients were obtained and analyzed due to challenges faced with accessing data among different modalities. Of the 17 individuals studied, 12 patients were pediatric en bloc kidney recipients and 5 patients were adult en bloc (horseshoe kidney) kidney recipients. To compare this set of data to single kidney recipients, 22 additional patients who were recipients of single kidneys from living or deceased donors were chosen and divided via random selection during the same time frame from 2007 to 2023. The patients were randomly selected within the criteria reported from the en bloc recipients, which required that the EPTS range from 67-83 and KDPI to be less than 50 to appropriately and statistically compare the single kidney recipients to en bloc kidney recipients.

In addition to the types of transplantations, demographics and characteristics of the donors (

Table 1) and recipients (

Table 2) were obtained. The following variables were identified: age, gender, weight, height, BMI, and type of dialysis received prior to transplantation, all of which were represented as mean values with the corresponding units. Upon reviewing the clinical records of the chosen recipients, the following data were additionally identified: primary renal diseases for transplantation (

Figure 1), HLA-match, post-operative graft status, and laboratory values including serum creatinine and eGFR values at post-transplantation, 1-week, 1-month, 3-months, and 1-year post-transplant (

Table 3). Numbers for laboratory values were represented as median values, along with the first and third interquartile ranges. Any values above 60 for eGFR values were calculated as 60 per the university medical center calculations.

3. Results

3.1. Donor Demographics and Characteristics

The donor demographics and characteristics among all four groups are shown in

Table 1. The mean age of pediatric en bloc donors was 2.06 years old, with the age ranging from 0 (months-old unspecified) to 10 years old. The mean weight of the pediatric en bloc donors was 14.16 kg, with the weight ranging from 7 kg to 43.4 kg. Taking an in-depth and extensive look into the breakdown of the weights, the weight range between the ages 0 and 1 years old was 7 kg to 14.4 kg, between the ages 1 and 2 was 9.3 kg to 14.5 kg, and between the ages 2 and 4 was 14.5 kg to 17 kg.

The mean age of the adult en bloc kidney donors was 51 years old, along with the mean age of the single kidney living donor and single kidney deceased donor noted to be at 48.73 years old and 33.73 years old, respectively. The mean weight of the adult en bloc kidney donors was 79.82 kg, whereas the mean weight of the single kidney living donor and single kidney deceased donor was 69.07 kg and 87.62 kg, respectively, which correlates with the mean height of the donors. Further information about the donors including race and cause of death were unable to be accessed.

3.2. Recipient Demographics and Characteristics

The recipient demographics and characteristics among all four groups are shown in

Table 2. The mean age of the pediatric en bloc kidney recipients was 48.43 years old, which was lower compared to the mean age of all other groups: 61.40 years old for the adult en bloc kidney recipients, 61.72 years old for the single kidney living donor recipients, and 65.27 years old for the single kidney deceased donor recipients. Furthermore, the percentage of female patients was also the highest within the pediatric en bloc kidney recipients, noted to be at 58.33%, likely due to the relatively smaller body mass and habitus as indicated by the lower mean weight of 75.40 kg compared to the other two single kidney recipient groups. It may be possible to hypothesize that the mean weight was the lowest in the adult en bloc kidney recipients, taking into consideration that the adult en bloc kidney (horseshoe kidney) may have the greatest renal mass and length.

Looking at the race of the recipients, the pediatric en bloc kidney recipients were likely to be white (58.83%), as well as for the single kidney recipients from living donors. However, the single kidney recipients from deceased donors were likely to be African-American (54.55%). Patients predominantly received hemodialysis over continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis among all groups, with the exception of the adult en bloc kidney recipients.

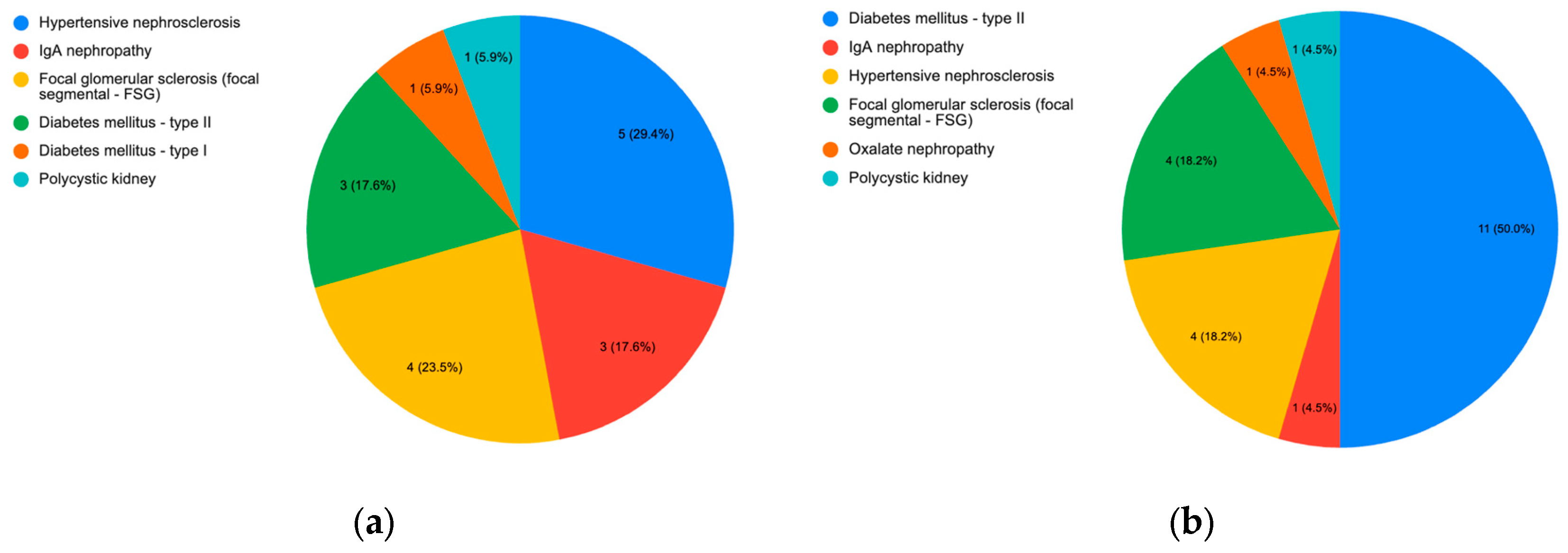

3.2.1. Primary Disease

The most prevalent primary renal disease of pediatric en bloc kidney recipients resulted to be hypertensive nephrosclerosis, while the most common primary renal disease for single kidney recipients resulted to be diabetic nephropathy from type 2 diabetes mellitus (

Figure 1).

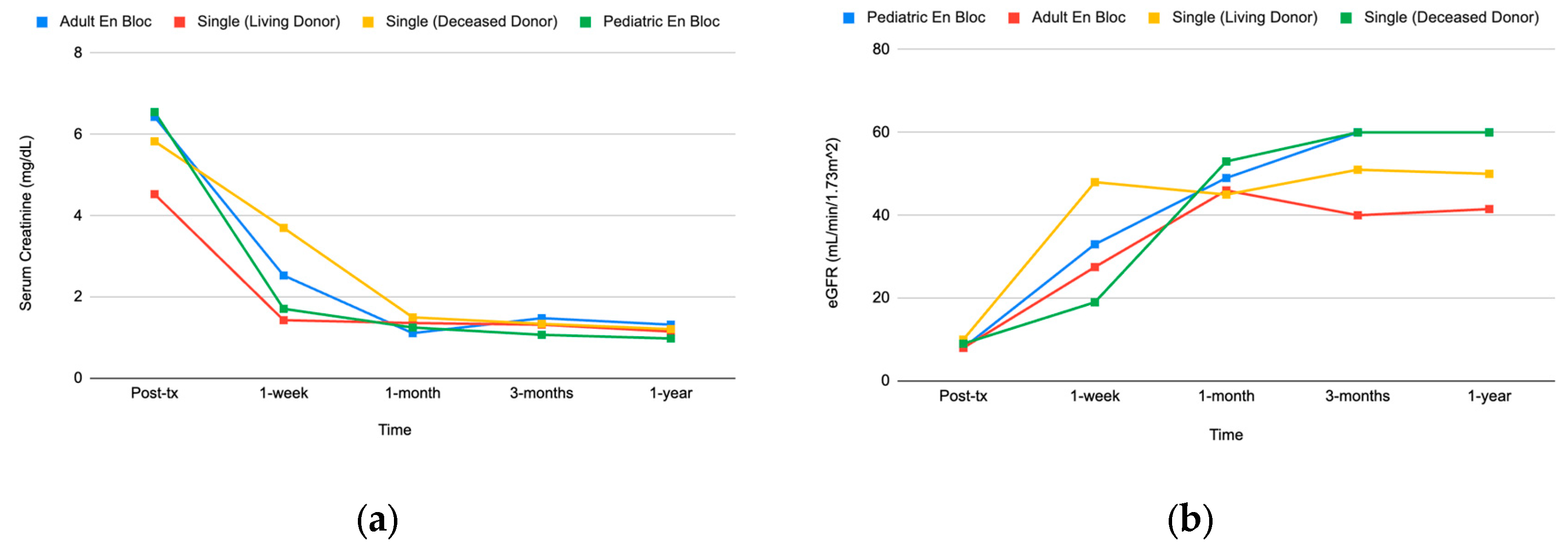

3.3. Post-Operative Outcomes

Serum creatinine and eGFR values were analyzed for this study to objectively represent the overall kidney function of the individuals. Given the two values, we were able to conclude that the post-operative outcomes among en bloc kidney recipients, specifically pediatric en bloc kidneys, were comparable to that of single kidney recipients as shown in

Table 3 and

Figure 2. The median serum creatinine value of the pediatric en bloc kidney recipients was 0.98 mg/dL at the 1-year mark, compared to 1.15 mg/dL and 1.21 mg/dL for the single kidney recipients from living or deceased donors, respectively. Additionally, the serum creatinine values of the pediatric en bloc recipients were lower at all other post-operative visits. As the patients were followed and monitored through the post-operative period to the 1-year mark, the serum creatinine values of the pediatric en bloc recipients were trending down at a more significant rate and was lower than that of any other groups (

Figure 2).

3.4. Post-Operative Complications and Graft Loss

Among the en bloc kidney recipients studied, there has been a total of 4 graft failures: one patient presented with acute rejection 3 years after transplantation, leading to re-transplantation. A total of two patients have passed away since due to intracranial hemorrhage 4 years later and pulmonary malignancy 2 years later. The remaining patient passed away 6 years later from an unknown cause, unspecified whether there were any issues pertaining to the graft function.

Among the single kidney recipients, there has been a total of 3 graft failures: one patient presented with recurrence of the primary renal disease (IgA nephropathy) 7 years later, one patient presented with recurrent infection, and the remaining patient presented with surgical complications 7 days after the procedure. Patients of all other groups are living and have functioning kidneys that are being followed up by the university medical center.

4. Discussion

This single-center experience from the university medical center provided satisfactory post-operative outcomes as well and supported the conclusion of multiple published literature that pediatric en bloc kidney transplantation results in superior graft function in contrast to single kidney recipients. Likewise, the pediatric en bloc kidney recipients presented with relatively immediate post-operative complications compared to recipients of single kidneys (recurrence of primary renal disease) [

5].

The concern remains, however, regarding ureteral complications including stenosis and leakage, thrombosis, and hyperfiltration injury, as these pediatric en bloc kidneys are still growing anatomically to reach its full and appropriate size [

2]. To address the ongoing concern, we may be able to further explore what is implemented in current practice, which includes the addition of induction therapy, use of advanced antiplatelet and anticoagulation medication post-operatively, prevalence of increasingly adept surgical skills, and sophisticated imaging modalities such as interventional radiology to track the progress of each patient. With these protocols in place, some of the initial concerns regarding renal mass, surgical skills, and thrombosis may be alleviated, as with this single-center study as well, there was adequate growth of the kidneys and significant improvement and return of filtration with the pediatric en bloc kidneys. This growth was not only seen here, but also seen in one of the studies done at a different institution, as they were able to track growth of the pediatric en bloc kidneys until 6-months post-transplant [

1]. The question still exists, however, whether this growth was a result of pure compensatory physiological growth, or a growth driven by hyperfiltration [

6].

A limitation to this study consisted of a small sample size and the high-risk end stage renal disease patient population that the university medical center operates on, which may in turn affect the outcomes of the surgical procedures. Given that hypertensive nephrosclerosis and diabetic nephropathy were the two most prevalent primary renal diseases among the four groups, it is likely that the patients had additional comorbidities that indirectly shaped the direction in which the graft function progressed. It is of great importance to also consider the socioeconomic status of the patient population of the city at which this university medical center is located in, for a high percentage of patients do not have the most optimal access to healthcare, yet alone access to transportation. Thus, some patients may not have been able to afford and access the proper post-operative care necessary to produce the most favorable outcomes.

A few possible topics for future research may include the correlation between the age of the pediatric donor and its effect on graft survival in adult recipients if any exist, and whether the stage of anatomic growth of the pediatric donors has any cause in reducing the risk of thrombosis and prolonging graft survival. Furthermore, as we enter an era of a rise in telehealth, it may be worthwhile to study whether in the field of transplantation as a whole, the increase in frequency of telehealth will reduce the mortality rate and waiting time on the transplant list, as more patients may have access to faster test results and care.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, analysis, writing – original draft preparation, Chang, Y.; writing – review and editing, supervision, project administration, Ekwenna, O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Published Materials

This article is a revised and expanded version of a poster entitled “A Single-Center Experience of En Bloc vs. Single Renal Transplantation on Adult Recipients”, which was presented at the American Society of Transplant Surgeons Winter Symposium on January 11, 2024 in Miami, Florida.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Dr. Obi Ekwenna. We would like to acknowledge the Department of Urology and Renal Transplantation as well as Dr. Obi Ekwenna, Mary Brown, and Jennifer Mikulak for the direction, guidance, and mentorship on the project.

References

- Wang H., Li J., Liu L., et al. En Block Kidney Transplantation From Infant Donors Younger Than 10 Months Into Pediatric Recipients. Pediatric Transplantation 2017, 21(2).

- Kizilbash S., Evans M., Chinnakotla S., Chavers B. Survival Benefit of En Bloc Transplantation of Small Pediatric Kidneys in Children. Transplanation 2020, 104(11), 2435-2443. [CrossRef]

- Sharma A., Fisher R., Cotterell A., King A., Maluf, A. Posner, M. En Block Kidney Transplantation From Pediatric Donors: Comparable Outcomes With Living Donor Kidney Transplantation. Transplantation 2011, 92 (5), 564-569.

- Mohanka R., Basu A., Shapiro R., Kayler L. Single Versus En Block Kidney Transplantation From Pediatric Donors Less Than or Equal to 15 kg. Transplantation 2008, 86(2), 264-268.

- López-González JA., Beamud-Cortés M., Bermell-Marco L., et al. A 20-year experience in cadaveric pediatric en bloc kidney transplantation in adult recipients. Actas Urol Esp (Engl Ed) 2022, 46(2), 85-91.

- Silber S, Malvin RL. Compensatory and obligatory renal growth in rats. Am J Physiol 1974, 226, 114–117. [CrossRef]

- C.Y.; S.S.; E.O. A Single-Center Experience of En Bloc vs. Single Renal Transplantation on Adult Recipients. American Society of Transplant Surgeons Winter Symposium, Miami, Florida, USA, January 11, 2024.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).