Submitted:

01 October 2024

Posted:

02 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Patients and Methods

2.1. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Population

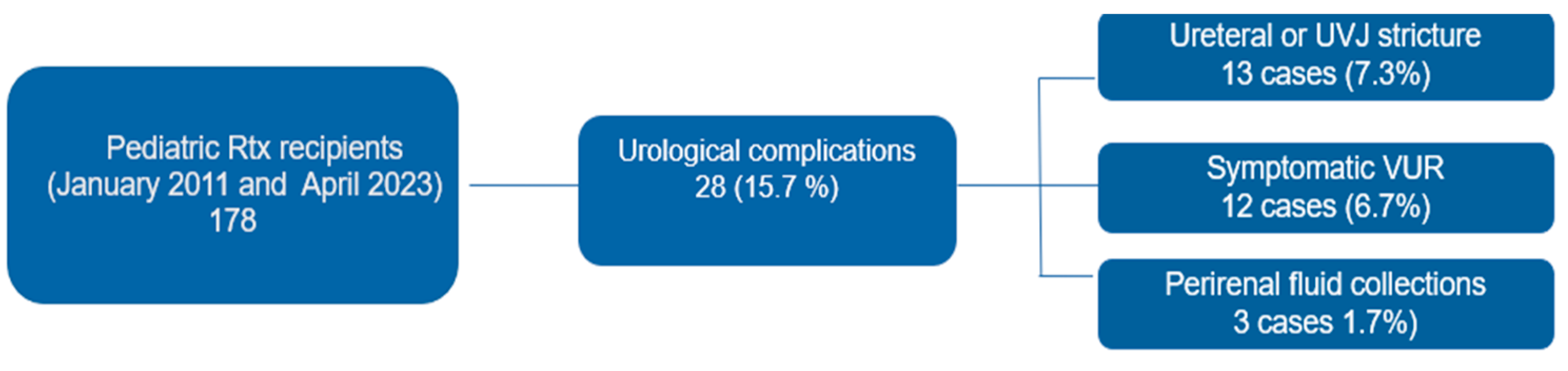

3.2. Classification and management of urological complications

3.3. Costs of Urological Complications

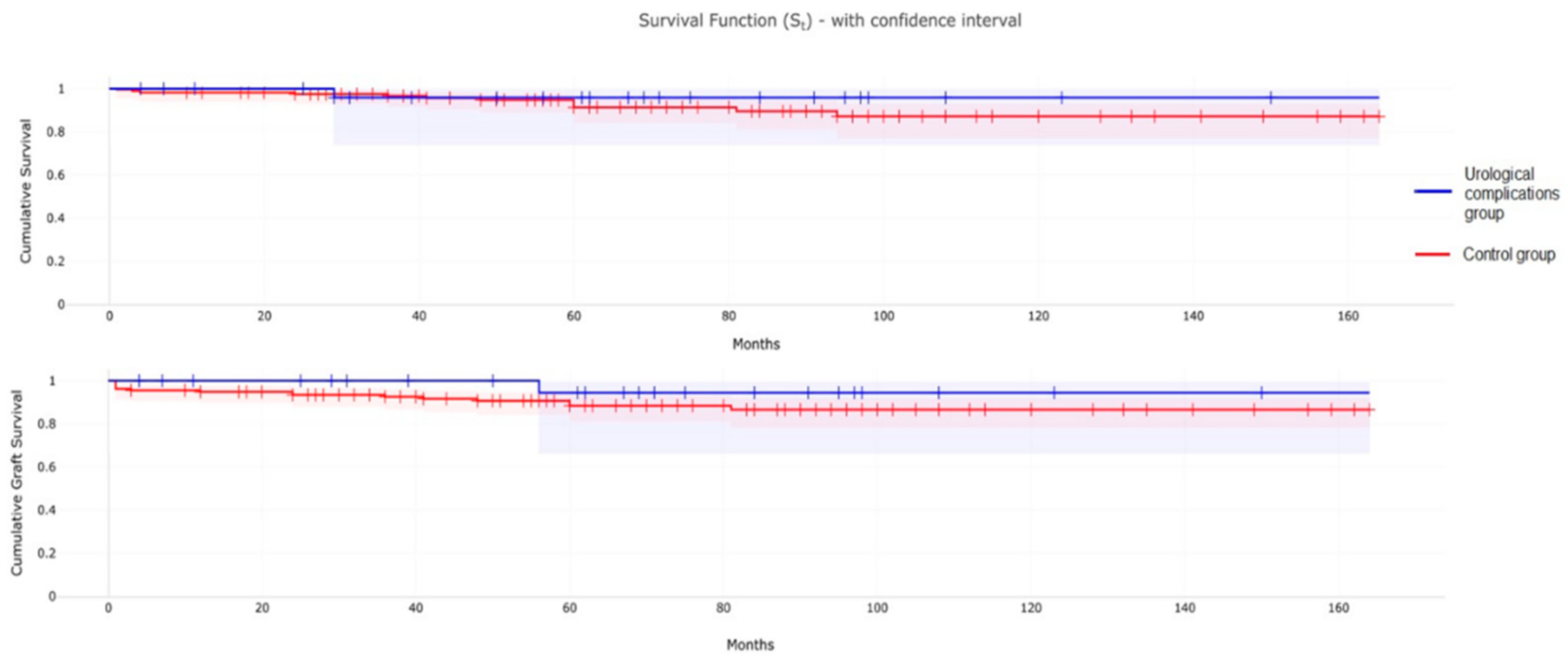

3.4. Patient and Graft Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saran, R.; Robinson, B.; Abbott, K.C.; Agodoa, L.Y.C.; Bragg-Gresham, J.; Balkrishnan, R.; et al. US Renal Data System 2018 Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 2019, 73 (Suppl 1), A7–A8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonthuis, M.; Vidal, E.; Bjerre, A.; Aydoğ, Ö.; Baiko, S.; Garneata, L.; et al. Ten-Year Trends in Epidemiology and Outcomes of Pediatric Kidney Replacement Therapy in Europe: Data from the ESPN/ERA-EDTA Registry. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2021, 36, 2337–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choate, H.R.; Mihalko, L.A.; Choate, B.T. Urologic Complications in Renal Transplants. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2019, 8, 14147–14147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.S.; Kim, K.S.; Choi, S.W.; Bae, W.J.; Hong, S.H.; Lee, J.Y.; et al. Ureteral Complications in Kidney Transplantation: Analysis and Management of 853 Consecutive Laparoscopic Living-Donor Nephrectomies in a Single Center. Transplant Proc. 2016, 48, 2684–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranchin, B.; Chapuis, F.; Dawhara, M.; Canterino, I.; Hadj-Aïssa, A.; Saïd, M.H.; et al. Vesicoureteral Reflux after Kidney Transplantation in Children. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2000, 15, 1852–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.A.; Giel, D.W.; Hastings, M.C. Endoscopic Deflux Injection for Pediatric Transplant Reflux: A Feasible Alternative to Open Ureteral Reimplant. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2008, 4, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taher, A.; Zhu, B.; Ma, S.; Shun, A.; Durkan, A.M. Intra-Abdominal Complications after Pediatric Kidney Transplantation: Incidence and Risk Factors. Transplantation 2019, 103, 1234–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamarelis, G.; Vernadakis, S.; Moris, D.; Altanis, N.; Perdikouli, M.; Stravodimos, K.; et al. Lithiasis of the Renal Allograft, a Rare Urological Complication Following Renal Transplantation: A Single-Center Experience of 2,045 Renal Transplantations. Transplant Proc. 2014, 46, 3203–3205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapenhorst, L.; Sassen, R.; Beck, B.; Laube, N.; Hesse, A.; Hoppe, B. Hypocitraturia as a Risk Factor for Nephrocalcinosis after Kidney Transplantation. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2005, 20, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caamiña, L.; Pietropaolo, A.; Prudhomme, T.; et al. Endourological Management of Ureteral Stricture in Patients with Renal Transplant: A Systematic Review of Literature. J. Endourol. 2024, 38, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomen, L.; De Wall, L.L.; Krupka, K.; Tönshoff, B.; Wlodkowski, T.; Van Der Zanden, L.F.; et al. The Strengths and Complexities of European Registries Concerning Paediatric Kidney Transplantation Health Care. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1121282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bessede, T.; Hammoudi, Y.; Bedretdinova, D.; Parier, B.; Francois, H.; Durrbach, A.; et al. Preoperative Risk Factors Associated with Urinary Complications after Kidney Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2017, 49, 2018–2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hotta, K.; Miura, M.; Wada, Y.; Fukuzawa, N.; Iwami, D.; Sasaki, H.; et al. Atrophic Bladder in Long-Term Dialysis Patients Increases the Risk for Urological Complications after Kidney Transplantation. Int. J. Urol. 2017, 24, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, K.M.; Windsperger, A.; Alanee, S.; Humar, A.; Kashtan, C.; Shukla, A.R. Risk Factors and Treatment Success for Ureteral Obstruction after Pediatric Renal Transplantation. J. Urol. 2010, 183, 317–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irtan, S.; Maisin, A.; Baudouin, V.; Nivoche, Y.; Azoulay, R.; Jacqz-Aigrain, E.; et al. Renal Transplantation in Children: Critical Analysis of Age-Related Surgical Complications. Pediatr. Transplant. 2010, 14, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torricelli, F.C.M.; Watanabe, A.; Piovesan, A.C.; Antonopoulos, I.M.; David-Neto, E.; Nahas, W.C. Urological Complications, Vesicoureteral Reflux, and Long-Term Graft Survival Rate after Pediatric Kidney Transplantation. Pediatr. Transplant. 2015, 19, 844–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castagnetti, M.; Angelini, L.; Ghirardo, G.; Zucchetta, P.; Gamba, P.; Zanon, G.; et al. Ureteral Complications after Renal Transplant in Children: Timing of Presentation, and Their Open and Endoscopic Management. Pediatr. Transplant. 2014, 18, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, V.; Torino, G.; Gerocarni Nappo, S.; Mele, E.; Innocenzi, M.; Mattioli, G.; et al. Urological Complications Following Kidney Transplantation in Pediatric Age: A Single-Center Experience. Pediatr. Transplant. 2016, 20, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routh, J.C.; Yu, R.N.; Kozinn, S.I.; Nguyen, H.T.; Borer, J.G. Urological Complications and Vesicoureteral Reflux Following Pediatric Kidney Transplantation. J. Urol. 2013, 189, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, C.D.; Shannon, R.; Rosoklija, I.; Nettey, O.S.; Superina, R.; Cheng, E.Y.; et al. Ureteral Complications of Pediatric Renal Transplantation. J. Urol. 2019, 201, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englesbe, M.J.; Lynch, R.J.; Heidt, D.G.; Thomas, S.E.; Brooks, M.; Dubay, D.A.; et al. Early Urologic Complications after Pediatric Renal Transplant: A Single-Center Experience. Transplantation 2008, 86, 1560–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shokeir, A.A.; Ali-El-Dein, B.; Osman, Y.; Zahran, M.; Eldiasty, I. Surgical Complications in Live-Donor Paediatric and Adolescent Renal Transplantation: Study of Risk Factors – Mansoura Experience 1976–2017. Arab J. Urol. 2018, 16, S23–S24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrell, E.C.; Su, R.; O’Kelly, F.; Semanik, M.; Farhat, W.A. The Utility of Native Ureter in the Management of Ureteral Complications in Children after Renal Transplantation. Pediatr. Transplant. 2021, 25, e14051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Territo, A.; Bravo-Balado, A.; Andras, I.; et al. Effectiveness of Endourological Management of Ureteral Stenosis in Kidney Transplant Patients: EAU-YAU Kidney Transplantation Working Group Collaboration. World J. Urol. 2023, 41, 1951–1957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahnemai-Azar, A.A.; Gilchrist, B.F.; Kayler, L.K. Independent Risk Factors for Early Urologic Complications after Kidney Transplantation. Clin. Transplant. 2015, 29, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paltiel, H.J.; Barnewolt, C.E.; Chow, J.S.; Bauer, S.B.; Diamond, D.A.; Stamoulis, C. Accuracy of Contrast-Enhanced Voiding Urosonography Using Optison™ for Diagnosis of Vesicoureteral Reflux in Children. J. Pediatr. Urol. 2023, 19, 135.e1–135.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasiske, B.L.; Vazquez, M.A.; Harmon, W.E.; Brown, R.S.; Danovitch, G.M.; Gaston, R.S.; et al. Recommendations for the Outpatient Surveillance of Renal Transplant Recipients. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2000, 11 Suppl 15, S1–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Ramanathan; Posner, M. ; Fisher. Pediatric Kidney Transplantation: A Review. Transpl. Res. Risk Manag. 2013, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, P.; Marks, S.D.; Desai, D.Y.; Mushtaq, I.; Koffman, G.; Mamode, N. Challenges Facing Renal Transplantation in Pediatric Patients with Lower Urinary Tract Dysfunction. Transplantation 2010, 89, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husmann, D.A. Lessons Learned from the Management of Adults Who Have Undergone Augmentation for Spina Bifida and Bladder Exstrophy: Incidence and Management of the Non-Lethal Complications of Bladder Augmentation. Int. J. Urol. 2018, 25, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajpoot, D.K.; Gomez, A.; Tsang, W.; Shanberg, A. Ureteric and Urethral Stenosis: A Complication of BK Virus Infection in a Pediatric Renal Transplant Patient. Pediatr. Transplant. 2007, 11, 433–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, A.; Smith, J.M.; Skeans, M.A.; Gustafson, S.K.; Wilk, A.R.; Castro, S.; et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 Annual Data Report: Kidney. Am. J. Transplant. 2020, 20 (Suppl. S1), 20–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roijen, J.H.; Kirkels, W.J.; Zietse, R.; Roodnat, J.I.; Weimar, W.; Ijzermans, J.N. Long-Term Graft Survival after Urological Complications of 695 Kidney Transplantations. J. Urol. 2001, 165 Pt 1, 1884–1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Carlo, H.N.; Darras, F.S. Urologic Considerations and Complications in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Adv. Chronic Kidney Dis. 2015, 22, 306–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Study group | Control group | P value |

| Number of patients | 28 | 150 | |

| Gender | 0.589951 | ||

| Male | 17 (60%) | 99 (66%) | |

| Female | 11 (40%) | 51 (34%) | |

| Source | 0.164926 | ||

| Living donor | 8 (29%) | 26 (17.3%) | |

| Deceased donor | 20 (71%) | 124 (82.7%) | |

| Mean age at RTx, y (SD) | 11 (5) | 9.61 (5.57) | 0.4456 |

| Cause of ESRD | |||

| CAKUT | 17 (61%) | 73 (48.6%) | 0.24 |

| Other causes* | 11 (39%) | 77 (51.4%) | |

| Renal replacement therapy | 0.240508 | ||

| Previous RTx and dialysis | 6 (21%) | 17 (11.3%) | |

| Dialysis pre RTx | 13 (46%) | 106 (70.7%) | |

| Pre-emptive RTx | 9 (32%) | 27 (18%) |

| Variable | Study patients | Ureteral obstruction subgroup * | VUR subgroup |

| Number of patients | 28 | 16 (57%) | 12 (43%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 17 (60%) | 9 (56%) | 8 (67%) |

| Female | 11 (40%) | 7 (44%) | 4 (33%) |

| Cause of ESRD | |||

| CAKUT | 17 (61%) | 11 (69%) | 6 (50%) |

| Renal hypoplasia/dysplasia/ agenesis +/- VUR | 15 |

10 |

5 |

| PUV | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Urogenital sinus malformation | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other causes | 11 (39%) | 5 (31%) | 6 (50%) |

| Congenital nephrotic syndrome | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| SRNS | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Cystic disease | 4 | 1 | 3 |

| Renal impairment after neonatal asphyxia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Age at RTx, mean years (SD) | 11 (5) | 12 (5) | 8 (5) |

| Source | |||

| Living donor | 8 (29%) | 4 (25%) | 4 (33%) |

| Deceased donor | 20 (71%) | 12 (75%) | 8 (67%) |

| Renal replacement therapy | |||

| Previous RTx and dialysis | 6 (21%) | 6 (37,5%) | 0 (%) |

| Dialysis pre RTx [mean months, SD] | 13 (46%) [38.6, 27] | 6 (37,5%) [37.7, 25.7] | 7 (58%) [43.6, 30.6] |

| Pre-emptive RTx | 9 (32%) | 4 (25%) | 5 (42%) |

| Pre-existing bladder dysfunction | 8 (28%) | 5 (31%) | 3 (25%) |

| Abdominal surgery pre-RTx | 15 (53%) | 8 (50%) | 7 (58%) |

| Follow-up, mean months (SD) | 65 (36) | 60 (32) | 73 (41) |

| Graft failure | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Complications | N | Post-RTx onset day | Diagnostic studies | First Treatment | Subsequent treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

UVJ obstruction (AKI) + Urinary leakage |

3 | 8th (2), 11th, | Ultrasound (3), Anterograde pyelography (2); Cystoscopy + retrograde pyelography (1), | Emergency nephrostomy and DJ stent placement (2); MJ ureteral stent placement (1) | DJ replacement (1), Ureteroneocystostomy (3) |

| Obstructive lymphocele | 1 | 21st | Ultrasound, Drained fluid analysis | Surgical drainage into peritoneal cavity | |

| UVJ obstruction (AKI) + Urinary leakage | 2 | 21st, 26th |

Ultrasound (2), MAG3 scintigraphy (2), Anterograde pyelography (1) | Ureteroneocystostomy and DJ stent placement (1), Emergency nephrostomy (1), | DJ stent placement (1) |

| Obstructive perirenal hematoma | 1 | 27Th | Ultrasound | DJ stent placement | |

| Total | 7 |

| Complications | N | Post-RTx day of onset | Diagnostic studies | First treatment | Subsequent treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VUR complicated by UTI (3) | 3 | 35th, 59th and 63rd | VCUG(3), DMSA scintigraphy (3) | Endoscopic injection of a bulking agent (Deflux) (2) + Circumcision (1), Conservative (antibiotic prophylaxis) (1) | 2nd Endoscopic injection of a bulking agent (Deflux) (2) |

| Obstructive lymphocele | 1 | 42nd | Ultrasound, Drained fluid analysis | Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage | |

| Middle 1/3 ureteral stricture (AKI) | 1 | 48th | Ultrasound, MAG3 Scintigraphy. | DJ ureteral stent placement | End-to-side anastomosis of the transplant to the native ureter |

| Ureteral (1) and UVJ (AKI) (1) stricture in suspected BK virus infection/ reactivation | 2 | 65th and 79th | Ultrasound (2), MAG3 Scintigraphy (2), Magnetic Resonance Urography + Cystoscopy and retrograde pyelography (1) | DJ ureteral stent placement (2) + Balloon dilatation (1); | Nephrostomy and subsequent End-to-side anastomosis of the transplant to the native ureter (1); |

| Urolithiasis and pyeloureteral junction stricture (AKI) | 1 | 58th | Ultrasound; Anterograde pyelography; MAG3 Scintigraphy; Abdominal CT + Transnephrostomic contrastographic study under CT guidance; | Emergency nephrostomy | DJ ureteral stent placement |

| Bladder outlet obstruction and UVJ stricture | 1 | 69th | Ultrasound, MAG3 Scintrigraphy | Vesicostomy | DJ stent placement and subsequent continent enterocystoplasty and catheterizable stoma (Monti Procedure). |

| Total | 9 |

| Complications | N | Post-RTx day of onset | Diagnostic studies | First Treatment | Subsequent treatments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder dysfunction and VUR complicated by UTI | 1 | 110th | Ultrasound, MAG3 scintigraphy, Video urodynamic tests | Suprapubic percutaneous cystostomy | Stimulation of the posterior tibial-pudendal nerve |

| VUR complicated by UTI in pre-existing poor bladder capacity | 1 | 117th | Ultrasound (1), ceVUS (1), | Bladder augmentation | |

|

UVJ obstruction with ureteral rupture and abscessed urinoma. Recurrent UVJ obstruction after ureteral stent removal |

1 | 157th | Abdominal CT, Drained fluid analysis, Retrograde endoscopic urethrography. Anterograde pyelography and retrograde endoscopic urethrography. |

Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage, MJ ureteral stent placement. Emergency nephrostomy |

Replacement of ureteral MJ stent with DJ stent. Subsequent replacement of a transplanted ureter with a native ureter and ureteral stent placement. |

| Exophytic amorphous vesical lesion and UVJ stricture | 1 | 199th | Ultrasound, MAG3 scintigraphy, cystoscopy. | Endoscopic removal of bladder exophytic lesion and placement of a DJ ureteral stent | 2° Endoscopic removal of bladder exophytic lesion and placement of a DJ ureteral stent |

| Ureteral stricture | 1 | 219th | Sonography, MAG3 scintigraphy | DJ ureteral stent placement | Uretero-neocystostomy, DJ stent placement and circumcision |

|

VUR complicated by UTI (6), Urethral stricture (1) |

7 | 270th, 545th, 567th, 771st, 1168th, 1764th, 3121st |

DMSA scintigraphy (5), VCUG (5), Video urodynamic tests (1) | Endoscopic injection of a bulking agent (Deflux) (5), Conservative (antibiotic prophylaxis) (1), Endoscopic urethral dilatation (1) | Circumcision (1) |

| Total | 12 |

| Patient number | 1st UTI | 2nd UTI | 3rd UTI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient n.1 | Klebsiella Pneumoniae | Escherichia coli | Escherichia coli |

| Patient n.2 | K. Ornithinolytica | K. Ornithinolytica | Escherichia coli |

| Patient n.3 | Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Escherichia coli | Klebsiella Oxytoca | |

| Patient n.4 | Enterococcus faecium | P. Aeruginosa | P. Aeruginosa |

| Patient n.5 | Escherichia coli | ||

| Patient n.6 | Enterococcus faecalis | ||

| Patient n.7 | Escherichia coli | ||

| Patient n.8 | Klebsiella Pneumoniae | Escherichia coli | |

| Patient n.9 | Escherichia coli |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).