Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

29 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

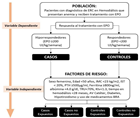

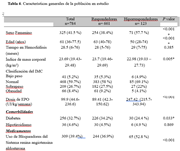

Anemia in advanced chronic kidney disease on hemodialysis patients is a very prevalent problem , and it is well known that the treatment of this type of anemia is through the use of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (erythropoietin). However, there are factors that determine a low response to erythropoietin (hyporesponse), which is defined as the need for doses greater than 200 IU/KG/week of erythropoietin to maintain objective hemoglobin levels in patients on hemodialysis, which are between 10 g/ dl to 12 g/dl.(22) In this observational study, analytical, multicenter case-control study, which included 784 patients, the prevalence of hyporesponse was 15.69%. It was found that female sex, age less than 50 years, a BMI less than 23 kg/m² and the use of Renin Angiotensin system blockers presented a higher prevalence of hyporesponse to treatment with EPO. Regarding laboratory parameters, it was found that low albumin levels, high ferritin levels, transferrin saturation less than 20% and high parathormone levels are risk factors associated with hyporesponsiveness to EPO.

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Inclusion Criteria

Data Collection

Statistical Analysis

Results

Discussion

LIMITATIONS

Conclusions

References

- Lv JC, Zhang LX. Prevalence and Disease Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease. Adv Exp.

- Med Biol. 2019;1165:3-15.

- Huertas J, Osorio W, Loachamin F. Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Kidney Disease. 2018. ed. National Directorate of Standardization; 111 p.

- Nafar M, Samavat S, Khoshdel A, Alipour-Abedi B. Anemia Evaluation and Erythropoietin Dose Requirement Among Hemodialysis Patients: a Multicenter Study. Iran J Kidney Dis. 2017 Jan;11(1):56-65.

- Gonzalez-Ortiz A, Correa-Rotter R, Vazquez-Rangel A, Vega-Vega O, Espinosa-Cuevas A.

- Relationship between protein-energy wasting in adults with chronic hemodialysis and the response to treatment with erythropoietin. BMC Nephrol. 2019 Aug 14;20(1):316.

- Feehally J, Floege J, Tonelli M, Johnson R. Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology. Sixth edition. Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2019. 958-965 p.

- Suttorp MM, Hoekstra T, Mittelman M, Ott I, Krediet RT, Dekker FW, et al. Treatment with high dose of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and mortality: analysis with a sequential Cox approach and a marginal structural model. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015 Oct;24(10):1068-75.

- Kato H, Nangaku M, Hirakata H, Wada T, Hayashi T, Sato H, et al. Rationale and design of observational clinical Research In chronic kidney disease patients with renal anemia: renal proGnosis in patients with Hyporesponsive anemia To Erythropoiesis-stimulating agents, darbepoetiN alfa (BRIGHTEN Trial). Clin Exp Nephrol. 2018 Feb;22(1):78-84.

- de Oliveira Júnior WV, Sabino A de P, Figueiredo RC, Rios DRA. Inflammation and poor response to treatment with erythropoietin in chronic kidney disease. J Bras Nefrol Orgao Of Soc Bras E Lat-Am Nefrol. Jun 2015;37(2):255-63.

- Pillajo Sanchez BL, Guacho Guacho JS, Moya Guerrero IR, Pillajo Sanchez BL, Guacho Guacho JS, Moya Guerrero IR. Chronic kidney disease. Literature review and local experience in a city in Ecuador. Rev Colomb Nefrol [Internet] . December.

- 2021 http://www.scielo.org.co/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S2500 50062021000300301&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=es.

- S. García de Vinuesa. FACTORS OF PROGRESSION OF CHRONIC RENAL DISEASE. SECONDARY PREVENTION. Nephrology. June 1, 2008;28:17-21.

- 11. Gorostidi M, Santamaría R, Alcázar R, Fernández-Fresnedo G, Galcerán JM, Goicoechea M, et al. Document of the Spanish Society of Nephrology on the KDIGO guidelines for the evaluation and treatment of chronic kidney disease. Nephrology. May 1, 2011.2014;34(3):302-16.

- Chen TK, Knicely DH, Grams ME. Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis and Management: A Review. JAMA. October 1, 2019;322(13):1294-313. Evans M, Lewis RD, Morgan AR, Whyte MB, Hanif W, Bain SC, et al. A Narrative Review of Chronic Kidney Disease in Clinical Practice: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Adv Ther. January 2022;39(1):33-43.

- Romagnani P, Remuzzi G, Glassock R, Levin A, Jager KJ, Tonelli M, et al. Chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2017 Nov 23;3:17088.

- Cases A, Egocheaga MI, Tranche S, Pallarés V, Ojeda R, Górriz JL, et al. Anemia of chronic kidney disease: Protocol of study, management and referral to Nephrology. Nefrol Engl Ed.January 1, 2018;38(1):8-12.

- Pagani A, Nai A, Silvestri L, Camaschella C. Hepcidin and Anemia: A Tight Relationship.Front Physiol. 2019;10:1294.

- Amnuay K, Srisawat N, Wudhikarn K, Assanasen T, Polprasert C. Factors associated with erythropoiesis-stimulating agent hyporesponsiveness anemia in chronic kidney disease patients. Hematol Rep. 2019 Sep 18;11(3):8183.

- Santos EJF, Dias RSC, Lima JF de B, Salgado Filho N, Miranda Dos Santos A.Erythropoietin Resistance in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: Current Perspectives. Int J Nephrol Renov Dis. 2020;13:231-7.

- Rodriguez y Rodriguez MB, Castro D'Franchis LJ, Reyes Jiménez AE, López Urtiz CA.

- Anemia and inflammation with the administration of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and their resistance in hemodialysis. Med Interna Mexico. 2015;31(2):156-63.

- Rosati A, Ravaglia F, Panichi V. Improving Erythropoiesis Stimulating Agent Hyporesponsiveness in Hemodialysis Patients: The Role of Hepcidin and Hemodiafiltration Online. Blood Purif. 2018;45(1-3):139-46.

- Cizman B, Smith HT, Camejo RR, Casillas L, Dhillon H, Mu F, et al. Clinical and Economic Outcomes of Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Hyporesponsiveness in the Post-Bundling Era. Kidney Med. Oct 2020;2(5):589-599.e1.

- Nair S, Trivedi M. Anemia management in dialysis patients: a PIVOT and a new path? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. May 2020;29(3):351-5.

- Skorecki K, Chertow G, Marsden P, Taal M, Yu A. Brenner and Rector's The Kidney. Tenth edition. Boston: Elsevier; 2016.

- Pertuz A, Garcia CI, Munoz Gomez C, Rico Fontalvo JE, Daza Arnedo R, Pájaro N, et al. Anemia in chronic kidney disease. Arch Med. 2021;17(2):1.

- Hazin MAA. Anemia in chronic kidney disease. Rev Assoc Medica Bras 1992. January 13, 2020;66Suppl 1(Suppl 1):s55-8.

- S. Anemia in kidney patients | Nephrology Today [Internet]. [cited May 8, 2023]. Available at: http://www.nefrologiaaldia.org/es-articulo-anemia -the-kidney-patient-178.

- Amato L, Addis A, Saulle R, Trotta F, Mitrova Z, Davoli M. Comparative efficacy and safety in ESA biosimilars vs. originators in adults with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Nephrol. Jun 2018;31(3):321-32.

- Badve SV, Beller EM, Cass A, Francis DP, Hawley C, Macdougall IC, et al. Interventions for erythropoietin-resistant anemia in dialysis patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. August 26, 2013;(8):CD006861.

- Sakaguchi Y, Hamano T, Wada A, Masakane I. Types of Erythropoietin-Stimulating Agents and Mortality among Patients Undergoing Hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol JASN. Jun 2019;30(6):1037-48.

- Minutolo R, Garofalo C, Chiodini P, Aucella F, Del Vecchio L, Locatelli F, et al. Types of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents and risk of end-stage kidney disease and death in patients with non-dialysis chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2021 Jan 25;36(2):267-74.

- Gafter-Gvili A, Schechter A, Rozen-Zvi B. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Chronic Kidney. Disease. Acta Haematol. 2019;142(1):44-50.

- Gupta N, Wish JB. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor Prolyl Hydroxylase Inhibitors: A Potential New Treatment for Anemia in Patients With CKD. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. Jun 2017;69(6):815-26.

- Weir MR. Managing Anemia across the Stages of Kidney Disease in Those Hyporesponsive to Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents. Am J Nephrol. 2021;52(6):450-66.

- Kanbay M, Perazella MA, Kasapoglu B, Koroglu M, Covic A. Erythropoiesis stimulatory agent-resistant anemia in dialysis patients: review of causes and management. Blood Purif. 2010;29(1):1-14.

- Santos EJF, Hortegal EV, Serra HO, Lages JS, Salgado-Filho N, Dos Santos AM. Epoetin alfa resistance in hemodialysis patients with chronic kidney disease: a longitudinal study. Braz J Med Biol Res Rev Bras Pesqui Medicas E Biol. 2018;51(7):e7288.

- Yu L, Song J, Lu X, Zu Y, Li H, Wang S. Association between Serum Magnesium and Erythropoietin Responsiveness in Hemodialysis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2019;44(3):354-61.

- Bamgbola OF, Kaskel FJ, Coco M. Analyzes of age, gender and other risk factors of erythropoietin resistance in pediatric and adult dialysis cohorts. Pediatr Nephrol Berl Ger. 2009 Mar;24(3):571-9.

- Bae MN, Kim SH, Kim YO, Jin DC, Song HC, Choi EJ, et al. Association of Erythropoietin-Stimulating Agent Responsiveness with Mortality in Hemodialysis and Peritoneal Dialysis Patients. PLOS ONE. Nov 20, 2015;10(11):e0143348.

- Lu Mediators Inflamm. Nov 26, 2020;2020:e1027230.

- Yajima T, Yajima K, Takahashi H. Association of the erythropoiesis-stimulating agent resistance index and the geriatric nutritional risk index with cardiovascular mortality in maintenance hemodialysis patients. PloS One. 2021;16(1):e0245625.

- Panichi V, Rosati A, Bigazzi R, Paoletti S, Mantuano E, Beati S, et al. Anaemia and resistance to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents as prognostic factors in haemodialysis patients: results from the RISCAVID study. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2011 Aug;26(8):2641-8.

- Okazaki M, Komatsu M, Kawaguchi H, Tsuchiya K, Nitta K. Erythropoietin resistance index and the all-cause mortality of chronic hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif.2014;37(2):106-12.

- López-Gómez JM, Portolés JM, Aljama P. Factors that condition the response to erythropoietin in patients on hemodialysis and their relationship to mortality. Kidney Int Suppl. December 2008;(111):S75-81.

- Guerrero Riscos MÁ, Guerrero-Riscos MÁ, Montes Delgado R, Montes-Delgado R, Seda Guzmán M, Seda-Guzmán M, et al. Erythropoietin resistance and survival in non-dialysis patients with stage 4-5 chronic kidney disease and heart disease. Nefrol Engl Ed. May 1, 2012;32(3):343-52.

- Chait Y, Kalim S, Horowitz J, Hollot C, Ankers E, Germain M, et al. The Greatly Misunderstood Erythropoietin Resistance Index and the Case for a New Responsiveness Measure. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2016 Jul;20(3):392-8.

- Mafla M. Resistance to erythropoietin in patients with anemia on hemodialysis, therapeutic algorithm. [Internet] [Thesis]. [Guayaquil]: University of Guayaquil; 2016. Available at : http://repositorio.ug.edu. ec/handle/redug/38246.

- Gunnell J, Yeun JY, Depner TA, Kaysen GA. Acute-phase response predicts erythropoietin resistance in hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. January 1999;33(1):63-72.

- Sibbel SP, Koro CE, Brunelli SM, Cobitz AR. Characterization of chronic and acute ESA hyporesponse: a retrospective cohort study of hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrol. August 18, 2015;16:144.

- Ingrasciotta Y, Lacava V, Marcianò I, Giorgianni F, Tripepi G, Arrigo GD, et al. Correction to: In search of potential predictors of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents (ESAs) hyporesponsiveness: a population-based study. BMC Nephrol. 2020 Jul 9;21(1):262.

- Coad J, Pedley K. Iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia in women. Scand J Clin Lab Research Suppl. 2014;244:82-9; discussion 89.

- Kassebaum NJ, Jasrasaria R, Naghavi M, Wulf SK, Johns N, Lozano R, et al. A systematic analysis of global anemia burden from 1990 to 2010. Blood. 2014 Jan 30;123(5):615-24.

- Lehtihet M, Bonde Y, Beckman L, Berinder K, Hoybye C, Rudling M, et al. Circulating Hepcidin-25 Is Reduced by Endogenous Estrogen in Humans. PloS One.2016;11(2):e0148802.

- XL, Dk R, RM, CM, La H, EA, et al. Progesterone receptor membrane component-1 regulates hepcidin biosynthesis. J Clin Invest [Internet]. January 2016 [cited 12 June 2023];126( 1). Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26657863/.

- Babitt JL, Lin HY. Molecular mechanisms of hepcidin regulation: implications for the anemia of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. Apr 2010;55(4):726-41.

- Babitt JL, Eisenga MF, Haase VH, Kshirsagar AV, Levin A, Locatelli F, et al. Controversies in optimal anemia management: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Conference. Kidney Int. Jun 2021;99(6):1280-95.

- Karaboyas A, Morgenstern H, Fleischer NL, Vanholder RC, Dhalwani NN, Schaeffner E, et al. Inflammation and Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agent Response in Hemodialysis Patients: A Self-matched Longitudinal Study of Anemia Management in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Kidney Med. Jun 2020;2(3):286-96.

- Won HS, Kim HG, Yun YS, Jeon EK, Ko YH, Kim YS, et al. IL-6 is an independent risk factor for resistance to erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in hemodialysis patients without iron deficiency. Hemodial Int Int Symp Home Hemodial. 2012 Jan;16(1):31-7.

- Ueda N, Takasawa K. Impact of Inflammation on Ferritin, Hepcidin and the Management of Iron Deficiency Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients. 2018 Aug 27;10(9):1173.

- Gillespie IA, Macdougall IC, Richards S, Jones V, Marcelli D, Froissart M, et al. Factors precipitating erythropoiesis-stimulating agent responsiveness in a European haemodialysis cohort: case-crossover study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015 Apr;24(4):414-26.

- Carrillo Esper R, Peña Pérez C, Zepeda Mendoza AD, Meza Márquez JM, Neri Maldonado R, Meza Ayala CM, et al. Ferritin and hyperferritinemic syndrome: Its impact on the critically ill; current concepts. Rev Asoc Mex Med Critica Ter. Intensive. September 2015;29(3):157-66.

- Khan A, Khan WM, Ayub M, Humayun M, Haroon M. Ferritin Is a Marker of Inflammation rather than Iron Deficiency in Overweight and Obese People. J Obes. 2016;2016:1937320.

- Fraile E, Gottschalk M, Zelechower H, Linari MA. Nutritional assessment in patients with.

- Chronic Kidney Disease, stage 5D, who undergo Hemodiafiltration and Hemodialysis. 26 November 2022. 2023;(11):7-15.

- Marcelli D, Bayh I, Merello JI, Ponce P, Heaton A, Kircelli F, et al. Dynamics of the erythropoiesis stimulating agent resistance index in incident hemodiafiltration and high-flux hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. Jul 2016;90(1):192-202.

- Ryta A, Chmielewski M, Debska-Slizien A, Jagodzinski P, Sikorska-Wisniewska M, Lichodziejewska-Niemierko M. Impact of gender and dialysis adequacy on anemia in peritoneal dialysis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(5):903-8.

- Hemodialysis dose | Nephrology Today [Internet]. [cited May 6, 2023]. Available at : http://www.nefrologiaaldia.org/es-articulo-dosis-hemodialisis-270.

- Daugirdas, JT. Hemodialysis Treatment Time: As Important as it Seems? Semin Dial. 2017 Mar;30(2):93-8.

- Varlotto J, Stevenson MA. Anemia, tumor hypoxemia, and the cancer patient. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005 Sep 1;63(1):25-36.

- Bohlius J, Bohlke K, Castelli R, Djulbegovic B, Lustberg MB, Martino M, et al.Management of Cancer-Associated Anemia With Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents ASCO/ASH Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37(15):1336-51.

- Pappa M, Dounousi E, Duni A, Katopodis K. Less known pathophysiological mechanisms of anemia in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015 Aug;47(8):1365-72.

- Gilbertson DT, Peng Y, Arneson TJ, Dunning S, Collins AJ. Comparison of methodologies to define hemodialysis patients hyporesponsive to epoetin and impact on counts and characteristics. BMC Nephrol. February 20, 2013;2:44 p.m.

- Drüeke TB, Eckardt KU. Role of secondary hyperparathyroidism in erythropoietin resistance of chronic renal failure patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant Off Publ Eur Dial Transpl Assoc - Eur Ren Assoc. 2002;17 Suppl 5:28-31.

- Chen L, Ling YS, Lin CH, He JX, Guan TJ. High Dose ESAs Are Associated with High iPTH Levels in Hemodialysis Patients with End-Stage Kidney Disease: A Retrospective Analysis. Front Public Health. 2015;3:258.

- Warady BA, Ng E, Bloss L, Mo M, Schaefer F, Bacchetta J. Cinacalcet studies in pediatric subjects with secondary hyperparathyroidism receiving dialysis. Pediatr Nephrol Berl Ger. 2020 Sep;35(9):1679-97.

- Tanaka M, Komaba H, Fukagawa M. Emerging Association Between Parathyroid Hormone and Anemia in Hemodialysis Patients. Ther Apher Dial Off Peer-Rev J Int Soc Apher Jpn Soc Apher Jpn Soc Dial Ther. June 2018;22(3):242-5.

- Meytes D, Bogin E, Ma A, Dukes PP, Massry SG. Effect of parathyroid hormone on erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest. 1981 May;67(5):1263-9.

- Bogin E, Massry SG, Levi J, Djaldeti M, Bristol G, Smith J. Effect of parathyroid hormone on osmotic fragility of human erythrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1982 Apr;69(4):1017-25.

- Coe LM, Madathil SV, Casu C, Lanske B, Rivella S, Sitara D. FGF-23 is a negative regulation of prenatal and postnatal erythropoiesis. J Biol Chem. 2014 Apr 4;289(14):9795-810.

- Singh S, Grabner A, Yanucil C, Schramm K, Czaya B, Krick S, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 23 directly targets hepatocytes to promote inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. Nov 2016;90(5):985-96.

- Montero D, Haider T, Flammer AJ. Erythropoietin response to anemia in heart failure. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2019 Jan;26(1):7-17.

- Samavat S, Nafar M, Khoshdel A, Abedi BA. Factors Contributing to Erythropoietin Hyporesponsiveness Among Hemodialysis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Multicenter Study. Nephro-Urol Mon [Internet]. 2017 [cited May 6, 2023];9(3). Available at: https://brieflands.com/articles/num-55534.html#abstract.

- Luo J, Jensen DE, Maroni BJ, Brunelli SM. Spectrum and Burden of Erythropoiesis- Stimulating Agent Hyporesponsiveness Among Contemporary Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis Off J Natl Kidney Found. Nov 2016;68(5):763-71.

- Luxardo R, Ceretta L, González-Bedat M, Ferreiro A, Rosa-Diez G. The Latin American Dialysis and Renal Transplantation Registry: report 2019. Clin Kidney J. Mar 2022;15(3):425-31.

- Charles C, Ferris AH. Chronic Kidney Disease. Prim Care. December 2020;47(4):585-95.

- Gluba-Brzózka A, Franczyk B, Olszewski R, Rysz J. The Influence of Inflammation on Anemia in CKD Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Jan 22;21(3):725.

- P MC, M PR, S FC. Treatment of anemia with erythropoietin and iron in Crohn's disease. Chronic Kidney Disease. Rev Chil Pediatrics. July 20, 2008;79(2):131-45.

- Del Vecchio L, Minutolo R. ESA, Iron Therapy and New Drugs: Are There New Perspectives in the Treatment of Anaemia? J Clin Med. 2021 Feb 18;10(4):839.

- Weiss, G.; Ganz, T.; Goodnough, L.T. Anemia of inflammation. Blood. 2019 Jan 3;133(1):40-50.

- Robinson, B.M.; Akizawa, T.; Jager, K.J.; Kerr, P.G.; Saran, R.; Pisoni, R.L. Factors affecting outcomes in patients reaching end-stage kidney disease worldwide: differences in access to renal replacement therapy, modality use, and haemodialysis practices. Lancet London Engl. July 16, 2016;388(10041):294-306.

- Locatelli, F.; Hannedouche, T.; Fishbane, S.; Morgan, Z.; Oguey, D.; White, W.B. Cardiovascular Safety and All-Cause Mortality of Methoxy Polyethylene Glycol-Epoetin Beta and Other Erythropoiesis-Stimulating Agents in Anemia of CKD: A Randomized Noninferiority Trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol CJASN. 2019 Dec 6;14(12):1701-10.

- van Haalen, H.; Jackson, J.; Spinowitz, B.; Milligan, G.; Moon, R. Impact of chronic kidney disease and anemia on health-related quality of life and work productivity: analysis of multinational real-world data. BMC Nephrol. 2020 Mar 7;21(1):88.

- Hoshino, J.; Muenz, D.; Zee, J.; Sukul, N.; Speyer, E.; Guedes, M.; et al. Associations of Hemoglobin Levels With Health-Related Quality of Life, Physical Activity, and Clinical Outcomes in Persons With Stage 3-5 Nondialysis CKD. J Ren Nutr Off J Counc Ren Nutr Natl Kidney Found. 2020 Sep;30(5):404-14.

- Spinowitz, B.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Winkelmayer, W.C.; Pergola, P.E.; Rochette, S.; Thompson-Leduc, P.; et al. Economic and quality of life burden of anemia on patients with CKD on dialysis: a systematic review. J Med Econ. Jun 2019;22(6):593-604.

- Obesity and Kidney Disease Progression | Nephrology Today [Internet]. [cited May 25, 2023]. Available at : http://www.nefrologiaaldia.org/es-articulo-obesidad-progresion-enfermedad- renal-210.

- Ogawa, T.; Shimizu, H.; Kyono, A.; Sato, M.; Yamashita, T.; Otsuka, K.; et al. Relationship between responsiveness to erythropoiesis-stimulating agent and long-term outcomes in chronic hemodialysis patients: a single-center cohort study. Int Urol Nephrol. January 2014;46(1):151-1.

- Bures, C.; Skachko, T.; Dobrindt, E.M.; Pratschke, J.; Uluk, D.; Mogl, M.T. Is There a Gender Difference in Clinical Presentation of Renal Hyperparathyroidism and Outcome after Parathyroidectomy? Visc Med. February 2020;36(1):34-40.

- Bajaj, S.; Makkar, B.M.; Abichandani, V.K.; Talwalkar, P.G.; Saboo, B.; Srikanta, S.S.; et al. Management of anemia in patients with diabetic kidney disease: A consensus statement. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2016;20(2):268-81.

- Alalawi, F.; Bashier, A. Management of diabetes mellitus in dialysis patients: Obstacles and challenges. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(3):1025-36.

- Eldehni, M.T.; Crowley, L.E.; Selby, N.M. Challenges in Management of Diabetic Patients on Dialysis. Kidney Dial. December 2022;2(4):553-64.

- Zeng, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xu, C.; Cao, J.; Deng, Q.; et al. Clinical prognostic role of bioimpedance phase angle in diabetic and non-diabetic hemodialysis patients. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2022;31(4):619-25.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).