Submitted:

01 February 2025

Posted:

04 February 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Groups

2.3. Ethics Statement

2.4. Blood Collection and Storage:

2.5. Sample Preparation

2.6. Drinking / Dialysis Water Sample Collection

2.7. Uremic Pruritus

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Limitation

7. Recommendation

References

- Vaidya SR, Aeddula NR. Chronic Kidney Disease. [Updated 2022 Oct 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535404/.

- Hashmi MF, Benjamin O, Lappin SL. End-Stage Renal Disease. [Updated 2023 Aug 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499861/.

- Landrigan, P.J.; Sly, J.L.; Ruchirawat, M.; Silva, E.R.; Huo, X.; Diaz-Barriga, F.; Zar, H.J.; King, M.; Ha, E.H.; Asante, K.A.; et al. Health Consequences of Environmental Exposures: Changing Global Patterns of Exposure and Disease. Ann. Glob. Health 2016, 82, 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balali-Mood M, Naseri K, Tahergorabi Z, Khazdair MR, Sadeghi M. Toxic Mechanisms of Five Heavy Metals: Mercury, Lead, Chromium, Cadmium, and Arsenic. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Apr 13; 12:643972. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsai, M., Fang, Y., Liou, H., Leu, J., & Lin, B. (2018). Association of Serum Aluminum Levels with Mortality in Patients on Chronic Hemodialysis. Scientific Reports, 8(1). [CrossRef]

- Rahimzadeh MR, Rahimzadeh MR, Kazemi S, Amiri RJ, Pirzadeh M, Moghadamnia AA. Aluminum Poisoning with Emphasis on Its Mechanism and Treatment of Intoxication. Emerg Med Int. 2022 Jan 11;2022:1480553. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mehrdad Rafati Rahimzadeh, Mehravar Rafati Rahimzadeh, Sohrab Kazemi, Roghayeh Jafarian Amiri, Marzieh Pirzadeh, Ali Akbar Moghadamnia, “Aluminum Poisoning with Emphasis on Its Mechanism and Treatment of Intoxication”, Emergency Medicine International, vol. 2022, Article ID 1480553, 13 pages, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Rana MN, Tangpong J, Rahman MM. Toxicodynamics of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury and Arsenic- induced kidney toxicity and treatment strategy: A mini review. Toxicol Rep. 2018 May 26;5:704-713. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tsai KF, Hsu PC, Kung CT, Lee CT, You HL, Huang WT, Li SH, Cheng FJ, Wang CC, Lee WC. The Risk Factors of Blood Cadmium Elevation in Chronic Kidney Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Nov 24;18(23):12337. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sun H, Brocato J, Costa M. Oral Chromium Exposure and Toxicity. Curr Environ Health Rep. 2015 Sep;2(3):295-303.

- Wise JP, Young JL, Cai J, Cai L. Current understanding of hexavalent chromium [Cr(VI)] neurotoxicity and new perspectives. Environ Int. 2022 Jan;158:106877. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Reference list].

- Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, Sutton DJ. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Exp Suppl. 2012;101:133-64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Reference list].

- Kuivenhoven M, Mason K. Arsenic Toxicity. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541125/.

- Klotz, K.; Weistenhofer, W.; Neff, F.; Hartwig, A.; van Thriel, C.; Drexler, H. The health effects of aluminum exposure. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2017, 114, 653–659. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29034866 (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afridi, H.I.; Talpur, F.N.; Kazi, T.G.; Brabazon, D. Effect of trace and toxic elements of different brands of cigarettes on the essential elemental status of irish referent and diabetic mellitus consumers. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2015, 167, 209–224. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25805269 (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krewski D, Yokel RA, Nieboer E, Borchelt D, Cohen J, Harry J, Kacew S, Lindsay J, Mahfouz AM, Rondeau V. Human health risk assessment for aluminium, aluminium oxide, and aluminium hydroxide. J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2007;10 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):1-269. doi: 10.1080/10937400701597766. Erratum in: J Toxicol Environ Health B Crit Rev. 2008 Feb;11(2):147. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rogers, J. (n.d.). LibreTexts Blog – The future is open. CLINICAL CHEMISTRY - THEORY, ANALYSIS, CORRELATION. Available online: http://blog.libretexts.org/.

- Yahaya, M., Shehu, A., & Dabai, F. (2013). Efficiency of Extraction of Trace metals from Blood samples using Wet Digestion and Microwave Digestion Techniques. Journal of Applied Sciences and Environmental Management, 17(3). [CrossRef]

- Yue, C.S.; Christie, M.; Lavergne, V.; Sikaneta, T.; Taskapan, H.; Mardini, K.; Tam, P.; Ting, R.; Ghannoum, M. Aluminum toxicokinetics in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 659–663. [Google Scholar]

- Schober, P., Boer C. and Schwarte L.A. (2018): Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth Analg.; 126(5):1763-1768.

- Anees M, Mumtaz A, Frooqi S, Ibrahim M, Hameed F. Serum trace elements (aluminum, copper, zinc) in hemodialysis patients. Biomedica. 2011;27:106-110.

- Siha, M. (2014). Effect of Occupational Exposure to Aluminum on Parathyroid Hormone and Calcium Metabolism. British Journal of Medicine and Medical Research, 4(11), 2265–2276. [CrossRef]

- Li, J., Molnar, M. Z., Zaritsky, J. J., Sim, J. J., Streja, E., Kovesdy, C. P., Salusky, I., & Kalantar-Zadeh, K. (2013). Correlates of parathyroid hormone concentration in hemodialysis patients. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 28(6), 1516–1525. [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Aluminium toxicity in Adult haemodialysis patients clinical guideline, V1. Principal author: Sioned Lloyd Approved by Wirral Drugs & Therapeutic Committee; 2011.

- Hegazy, A., El-Salam, M., & Ibrahim, G. (2015b). Serum Aluminum Level and Its Relation with Parathyroid Hormone and Anemia in Children on Maintenance Hemodialysis. British Journal of Medicine and Medical Research 7(6), 494–502. [CrossRef]

- Anees M, Mumtaz A, Frooqi S, Ibrahim M, Hameed F. Serum trace elements (aluminum, copper, zinc) in hemodialysis patients. Biomedica. 2011;27:106-110.

- Yue, C.S.; Christie, M.; Lavergne, V.; Sikaneta, T.; Taskapan, H.; Mardini, K.; Tam, P.; Ting, R.; Ghannoum, M. Aluminum toxicokinetics in peritoneal dialysis patients. Clin. Toxicol. 2011, 49, 659–663. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pubmed/21819285 (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Neiva, T.J.; Benedetti, A.L.; Tanaka, S.M.; Santos, J.I.; DAmico, E.A. Determination of serum aluminum, platelet aggregation and lipid peroxidation in hemodialyzed patients. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2002, 35, 345–350. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11887212 (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, C.W.; Weng, C.H.; Chan, M.J.; Lin-Tan, D.T.; Yen, T.H.; Huang, W.H. Association between serum aluminum level and uremic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17251. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30467375 (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gault, P.M.; Allen, K.R.; Newton, K.E. Plasma aluminium: A redundant test for patients on dialysis? Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2005, 42, 51–54. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15802033 (accessed on 9 February 2022). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Covic, A., & Gusbeth-Tatomir, P. (2009). Trace elements in end-stage renal disease – unfamiliar territory to be revealed. BMC Nephrology, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Shanmugam, L., Green, S. R., Radhakrishnan, H., Kadavanu, T. M., Ramachandrappa, A., Tiwari, S. R., Rajkumar, A. L., & Govindasamy, E. (2016). Trace Elements in Chronic Haemodialysis Patients and Healthy Individuals-A Comparative Study. JOURNAL OF CLINICAL AND DIAGNOSTIC RESEARCH. [CrossRef]

- Zima T, Mestek O, Tesar V, Tesarova P, Nemecek K, Zak A, et al. Chromium levels in patients with internal disease. Biochem Mol Biol Int.1998;46(2):365–74.

- Sang, Z., Zhang, H., Ma, W., Dong, Y., & Shi, B. (2022). Parathyroid hormones in relation to serum cadmium and lead: the NHANES 2003–2006. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(7), 18491–18498. [CrossRef]

- Sang, Z., Zhang, H., Ma, W., Dong, Y., & Shi, B. (2022b). Parathyroid hormones in relation to serum cadmium and lead: the NHANES 2003–2006. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(7), 18491–18498. [CrossRef]

- Mahieu S, Del Carmen Contini M, Gonzalez M, Millen N and Elias MM. Aluminum toxicity. Hematological effects. Toxicol Lett. 2000;111:235-42.

- Bandeira, C. M., De Almeida, A. Á., Carta, C. F. L., Almeida, A. A., De Figueiredo, F. a. T., Sandrim, V. C., Gonçalves, A. J., & Almeida, J. D. (2018). Tobacco influence in heavy metals levels in head and neck cancer cases. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 25(27), 27650–27656. [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, B., Azadi, N. A., Sharafi, K., & Nakhaee, S. (2023). The effects of active and passive smoking on selected trace element levels in human milk. Scientific Reports, 13(1). [CrossRef]

- Viana GF, Garcia KS, Menezes-Filho JA (2011) Assessment of carcino genic heavy metal levels in Brazilian cigarettes. Environ Monit Assess 181:255–265. [CrossRef]

- Wang H, Huang P, Zhang R, Feng X, Tang Q, Liu S, et al. Effect of lead exposure from electronic waste on haemoglobin synthesis in children. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. (2021) 94:911–8. doi: 10.1007/s00420-020-01619-1 (APRT and HPRT) by Pb2+: a potential mechanism of lead toxicity. Toxicology. (2009) 259:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2009.02.005.

- Friga, V., Linos, A. & Linos, D. A. Is aluminum toxicity responsible for uremic pruritus in chronic hemodialysis patients? Nephron 75, 48–53 (1997).

- Carmichael, A. J., McHugh, M. M., Martin, A. M. & Farrow, M. Serological markers of renal itch in patients receiving long term haemodialysis. British medical journal 296, 1575 (1988).

- (2019a, December 25). Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia. Ministry of Health Saudi Arabia. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/Publications/Pages/Publications-2019-12-25-001.aspx.

- Naderi, B., Attar, H. M., & Mohammadi, F. (2022). Evaluation of Some Chemical Parameters of Hemodialysis Water: A Case Study in Iran. Environmental Health Insights, 16. [CrossRef]

- Asadi M, Safdari M, Paydari Shayesteh N. The study of anion density in influent water to dialysis machines and its comparison with Association for the advance ment of medical instrumentation and European Pharmacopeia Standards in Qom Hospitals. J Sabzevar Univ Med Sci. 1970;20:117-121. Available online: http://jsums.sinaweb.net/article_321.html (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Taleshi MSA, Azimzadeh HR, Ghaneian MT, Namayandeh SM. Performance evaluation of reverse osmosis systems for water treatment required of hemodialy sis in Yazd educational hospitals, 2013. J Res Environ Heal. 2015;1:95-103.

- Totaro M, Casini B, Valentini P, et al. Evaluation and control of microbial and chemical contamination in dialysis water plants of Italian nephrology wards. J Hosp Infect. 2017;97:169-174.

- Shahryari A, Nikaeen M, Hatamzadeh M, Vahid Dastjerdi M, Hassanzadeh A. Evaluation of Bacteriological and chemical quality of dialysis water and fluid in Isfahan, central Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2016;45:650-656. Accessed September 18, 2022. Available online: https://ijph.tums.ac.ir/index.php/ijph/article/view/6801 (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Pirsaheb M, Naderi S, Lorestani B, Khosrawi T, Sharafi K. Efficiency of reverse osmosis system in the removal of lead, cadmium, chromium and zinc in feed water of dialysis instruments in Kermanshah Hospitals. J Maz Univ Med Sci. 2014;24:151-157. Available online: http://jmums.mazums.ac.ir/article-1-4516-en.html (accessed on 18 September 2022).

- Midrar-Ul-Haq, Khattak RA, Puno HK, Saif MS, Memon KS.2005. Surface and ground water contamination in NWFP and Sindh provinces with respect to trace elements. International Journal of Agriculture and Biology 7(2), 214–217.

- Ashraf M, Tariq J, Jaffar M.1991. Contents of trace metals in fish, sediment and water from three freshwater reservoirs on the Indus River, Pakistan. Fisheries Research 12(4), 355–64. [CrossRef]

| ICP-MS Condition | Value |

|---|---|

| Model Name | G8421A |

| Serial Number | JP15380160 |

| Nebulizer Type | MicroMist |

| Sample Introduction | PeriPump |

| Autosampler Type | Agilent I-AS |

| Autosampler Rack | 53 Samples |

| I-AS Escape Mode | Off |

| Plasma Ignition Mode | Aqueous Solution |

| Ion Lenses Model | x-Lens |

| Groups Variables |

Hemodialysis cases (N=60) |

Control (N=60) |

Total (N=120) |

P-value ^ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Years) (mean±SD) | 57.4 ± 17.4 | 56.3 ± 18.7 | 56.8 ±18 | 0.725 |

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Male | 29(48.4%) | 28(46.7%) | 57(47.5%) | 0.855 |

| Female | 31(51.7%) | 32(53.3%) | 63(52.5%) | |

| Residency (%) | ||||

| South Buraydah | 29(48.3%) | 27(45.0%) | 56(46.7%) | 0.578 |

| North Buraydah | 9(15.0%) | 15(12.5%) | 24(20.0%) | |

| West Buraydah | 10(16.7%) | 8(13.3%) | 18(15.0%) | |

| East Buraydah | 12(20.0%) | 10(16.7%) | 22(18.3%) | |

| Marital Status (%) | ||||

| Single | 11(18.3%) | 8(13.3%) | 19(18.8%) | 0.040* |

| Married | 37(61.7%) | 44(73.3%) | 81(67.5%) | |

| Widow | 11(18.3%) | 3(5.0%) | 14(11.7%) | |

| Divorced | 1(1.7%) | 5(8.3%) | 6(5.0%) | |

| Educational level (%) | ||||

| Illiterate | 32(53.3%) | 26(43.3%) | 58(48.3%) | 0.285 |

| Primary | 7(11.7%) | 6(10.0%) | 13(10.8%) | |

| Secondary | 6(10.0%) | 4(6.7%) | 10(8.3%) | |

| Tertiary | 5(8.3%) | 11(18.3%) | 16(13.3%) | |

| Diploma | 3(5.0%) | 1(1.7%) | 4(3.3%) | |

| Bachelor | 6(10.0%) | 12(20.0%) | 18(15.0%) | |

| Postgraduate | 1(1.7%) | 0(0.0%) | 1(0.8%) | |

| Occupation (%) | ||||

| Not working | 35(58.3%) | 28(46.7%) | 63(52.5%) | 0.410 |

| Employee | 13(21.7%) | 15(25.0%) | 28(23.3%) | |

| Retired | 12(20.0%) | 17(28.3%) | 29(24.2%) | |

| Numerical Score Rate | N. | % |

|---|---|---|

|

35 | 58.3% |

|

13 | 21.7% |

|

4 | 6.7% |

|

3 | 5.0% |

|

5 | 8.3% |

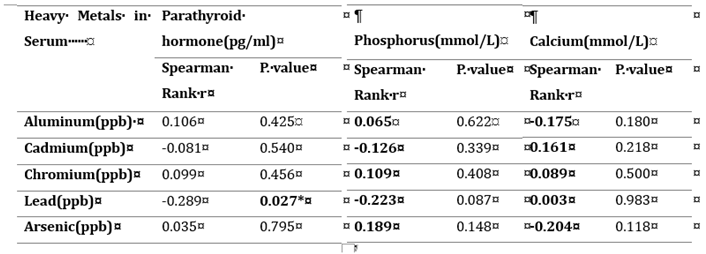

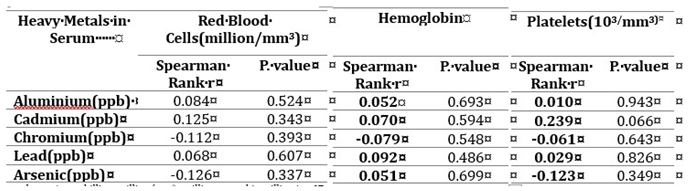

| Heavy Metals in Serum | Uremic Pruritus | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman Rank r | P. value | |

| Aluminum(ppb) | 0.027 | 0.838 |

| Cadmium(ppb) | -0.107 | 0.416 |

| Chromium(ppb) | 0.214 | 0.100 |

| Lead(ppb) | -0.152 | 0.245 |

| Arsenic(ppb) | -0.028 | 0.833 |

| Groups Variables |

Hemodialysis cases (N=60) |

Control (N=60) |

P-value ^ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aluminum (ppb) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 187.45 ±144.82 | 64.24 ± 35.86 | <0.001* |

| Range (Min-Max) | 865.9(44.09- 909.99) | 264(4.83-268.85) | |

| Cadmium (ppb) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.21 ±1.21 | 0.07 ± 0.12 | <0.001* |

| Range (Min-Max) | 8.47 (0.00-8.47) | 0.54 (0.00-0.54) | |

| Chromium (ppb) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.06 ±2.24 | 1.32 ±1.44 | <0.001* |

| Range (Min-Max) | 14.16(0.00-14.16) | 8.65(0.14-8.79) | |

| Lead (ppb) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 4.32 ±2.65 | 0.002 ±0.021 | <0.001* |

| Range (Min-Max) | 17.74(0.39-18.13) | 0.17(0.00-0.17) | |

| Arsenic(ppb) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1 ± 0.44 | 0.66 ± 0.37 | <0.001* |

| Range (Min-Max) | 1.97(0.48-2.46) | 1.72(0.21-1.92) | |

|

|

| Heavy Metals in Serum | Ferritin(ng/ml) | |

|---|---|---|

| Spearman Rank r | P. value | |

| Aluminum(ppb) | -0.178 | 0.182 |

| Cadmium(ppb) | -0.029 | 0.827 |

| Chromium(ppb) | -0.355 | 0.006* |

| Lead(ppb) | 0.029 | 0.831 |

| Arsenic(ppb) | 0.211 | 0.112 |

| Heavy metals | Normal range according to AAMI/ANSI | Concentration (ppb) |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | 10 Ppb | 1.82 |

| Chromium | 14 Ppb | 0.15 |

| Cadmium | 1 Ppb | 0.03 |

| Lead | 5 Ppb | 0.42 |

| Arsenic | 5 Ppb | 0.46 |

| Groups | Aluminum (ppb) | Cadmium (ppb) | Chromium (ppb) | Lead (ppb) | Arsenic (ppb) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |

|

South Buraydah group (N=36) |

29.6±42.7 | -0.04±0.54 | 0.35±0.30 | 0.93±1.22 | 0.70±0.23 |

|

North Buraydah group (N=12) |

33.9±43.9 | -0.23±0.94 | 0.39±0.80 | 0.49±0.25 | 0.67±0.27 |

|

West Buraydah group (N=7) |

20.9±25.7 | -0.41±1.24 | 0.29±0.46 | 1.23±2.09 | 0.65±0.17 |

|

East Buraydah group (N=8) |

17.2±14.7 | 0.03±0.28 | 0.53±0.96 | 2.69±6.38 | 0.63±0.30 |

| Kruskal-Wallis test | 0.90 | 1.02 | 5.9 | 0.93 | 1.07 |

| P-value | 0.825 | 0.796 | 0.116 | 0.818 | 0.784 |

| Name | Mass | Tune Mode | ISTD | R2 | Precision RSD% | Units | DL | BEC | LOD | LOQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 27 | He | 45Sc [He] | 0.9996 | 7.280432497 | ppb | 0.5005 | 0.8166 | 0.03107 | 0.09415 |

| Cr | 52 | He | 45Sc [He] | 0.9994 | 8.49323584 | ppb | 0.1048 | 0.0868 | 0.011061 | 0.011061 |

| As | 75 | He | 72Ge [He] | 0.9881 | 6.510971624 | ppb | 0.0929 | 0.1543 | 0.004088 | 0.012387 |

| Cd | 111 | He | 89Y [He] | 0.9998 | 14.52082453 | ppb | 0.0365 | 0.1656 | 0.001466 | 0.004443 |

| Pb | 208 | He | 209Bi [He] | 0.9996 | 0.489287076 | ppb | 0.3461 | 0.5521 | 0.018608 | 0.056389 |

| Name | Mass | Tune Mode | ISTD | R2 | Precision RSD% | Units | DL | BEC | LOD | LOQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al | 27 | He | 45Sc [He] | 0.9919 | 7.2432 | ppb | 0.2319 | 0.2295 | 0.0232 | 0.0289 |

| Cr | 52 | He | 45Sc [He] | 0.9966 | 4.4851 | ppb | 0.0783 | 0.1318 | 0.0041 | 0.0094 |

| As | 75 | He | 72Ge [He] | 0.9996 | 6.1927 | ppb | 0.0661 | 0.1107 | 0.0114 | 0.0345 |

| Cd | 111 | He | 89Y [He] | 0.9941 | 5.0982 | ppb | 4.6392 | 3.3649 | 0.0093 | 0.0282 |

| Pb | 208 | He | 209Bi [He] | 0.999 | 0.5427 | ppb | 0.0506 | 0.21 | 0.0070 | 0.0211 |

| Elements | Spik 5 ppb | Spik 10 ppb | Spik 15 ppb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery % | ±RSD% | Recovery % | ±RSD% | Recovery % | ±RSD% | |

| Al | 117.3067 | 3.5519 | 112.4384 | 10.6245 | 92.2339 | 14.6239 |

| Cr | 114.3375 | 3.201 | 113.1093 | 16.4002 | 92.4376 | 7.968 |

| As | 89.5835 | 11.7724 | 109.0297 | 3.4458 | 97.0331 | 14.7269 |

| Cd | 95.3322 | 0.9896 | 100.5768 | 0.4886 | 100.1193 | 0.2477 |

| Pb | 117.1043 | 2.2061 | 106.1278 | 5.2681 | 85.8772 | 1.0119 |

| Elements | Spik 5 ppb | Spik 10 ppb | Spik 15 ppb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery % | ±RSD% | Recovery % | ±RSD% | Recovery % | ±RSD% | |

| Al | 113.5116 | 1.2109 | 108.0549 | 0.8855 | 97.4791 | 1.3088 |

| Cr | 83.8930 | 2.7060 | 99.0152 | 2.1850 | 100.7660 | 4.0182 |

| As | 86.1409 | 5.2010 | 103.3337 | 5.4865 | 98.2201 | 8.9477 |

| Cd | 86.0087 | 6.8916 | 98.0248 | 0.7820 | 103.4809 | 5.9730 |

| Pb | 87.6788 | 0.4699 | 101.5059 | 0.4692 | 100.7964 | 0.3631 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).