1. Introduction

The glypican (GPC) family is a member of glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored heparan sulfate proteoglycans, consisting of six molecules, GPC1 to GPC6 [

1,

2]. GPCs comprise a core protein of approximately 60 to 70 kDa with a three-dimensional structure formed by multiple disulfide bonds to which heparan sulfate chains are attached. The core of GPCs is bound to the plasma membrane by GPI [

3]. The amino acid sequences of the six vertebrate GPCs are 17% to 63% identical [

2,

4]. GPCs have been thought to act as co-receptors and mediate several signaling pathways, including Wnt, hedgehog, and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) [

5,

6,

7,

8]. GPCs play pivotal roles in cell growth, development, and some disorders such as cancer and multiple sclerosis [

1,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

GPC5 was characterized in 1997 as the gene located in chromosome 13q32 and expressed in the human adult brain [

14]. In embryonic development, GPC5 expression is observed in central nervous system, kidney, and limb [

9]. GPC5 is functional in normal tissues from an early stage. GPC5 gene amplification and protein overexpression are observed in malignant lymphoma, non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), breast cancer, and rhabdomyosarcoma [

15,

16,

17,

18]. High GPC5 expression contributes to poor prognosis of NSCLC [

16]. GPC5-mediated activation of several pathways, such as Wnt, hedgehog, and fibroblast growth factor (FGF), might be involved in tumor development and progression [

2,

6,

19,

20].

In contrast, GPC5 has also been considered as a tumor suppressor. The lower expression of GPC5 is observed in various tumor types, including hepatocellular carcinoma, NSCLC, prostate cancer, and glioma [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Upregulation of GPC5 contrastively suppresses tumor migration, invasion, and proliferation in NSCLC [

26,

27]. Interestingly, a genetic variant of a high-risk allele linked to lower expression of GPC5 was defined as a risk of lung cancer who have never smoked [

28]. Simultaneously, GPC5 expression was 50% lower in adenocarcinoma than in matched healthy lung tissue [

28]. Furthermore, loss of GPC5 induces tumor growth through Wnt/β-catenin signaling and correlates with poor outcomes in NSCLC [

29]. These impaired expressions of GPC5 might be mediated by microRNAs (miRNAs), negative regulators of protein-coding genes. Some miRNAs, such as miR-297, miR-301b, miR-620, and miR-709, promote tumor malignancy by negative regulation of the GPC5-coding gene in cancer [

23,

24,

30,

31]. Thus, further investigations are essential to clarify the role of GPC5 as a tumor promoter or suppressor. Highly sensitive and specific antibodies are desired in multimodal experiments to analyze GPC5.

Previously, we have established numerous monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) against membrane proteins, including PD-L1 (clone L

1Mab-13) [

32], mouse CD39 (clone C

39Mab-2) [

33], EpCAM (clone EpMab-37) [

34], and TROP2 (clone TrMab-6) [

35] by using the Cell-Based Immunization and Screening (CBIS) method. This method can efficiently obtain a wide variety of antibodies that recognize linear or structural epitopes and modifications of extracellular domains of membrane protein in a short period. In this study, we have successfully established a novel anti-human GPC5 mAb (clone G

5Mab-1) that can be used for multiple applications using the CBIS method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Lines and Stable Transfectants

Cell lines, including LN229, Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-K1, and P3X63Ag8U.1 (P3U1) cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). The genes encoding human GPC5 (Catalog No.: IRAK082J20, Accession No.: NM_004466) were obtained from RIKEN BRC (Ibaraki, Japan). We thank Dr. Yoshihide Hayashizaki of RIKEN and Dr. Sumio Sugano of the University of Tokyo for providing the IRAK082J20 (cat. HGX033036) through the National BioResource Project of the MEXT, Japan. The expression plasmid of human GPC5 was subcloned into a pCAG-ble vector (FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan). pCAG-hGPC5 vector was transfected into cell lines using the Neon transfection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, LN229 and CHO-K1, which stably overexpressed GPC5 (hereafter described as LN229/GPC5 and CHO/GPC5, respectively), were stained with an anti-GPC5 mAb (clone 297716; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) and sorted using the SH800 cell sorter (Sony corp., Tokyo, Japan), followed by cultivation in a medium containing 0.5 mg/mL of Zeocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA).

The expression plasmid of GPC1 (pCMV6_GPC1, Catalog No.: SC321494, Accession No.: NM_002081) was purchased from OriGene Technologies, Inc. (Rockville, MD, USA). The complementary DNAs (cDNAs) of other Glypican members, including GPC2 (Catalog No.: IRAK049P06, Accession No.: NM_152742) and GPC4 (Catalog No.: IRAK015P17, Accession No.: NM_001448) were obtained from RIKEN RBC. GPC3v2 (Accession No.: NM_001164618) and GPC6 (Accession No.: NM_005708) cDNAs were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics KK (Tokyo, Japan). The cDNAs of GPC2, GPC3v2, and GPC4 were cloned into a pCAG-ble vector. A GPC6 cDNA was cloned into a pCAGzeo-ssnPA16 vector [

36]. The plasmids were also transfected into CHO-K1 cells and stable transfectants were established by staining with an anti-GPC1 mAb (clone 1019718; R&D systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA), an anti-GPC2 (CT3) mAb (#90488; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA), an anti-GPC3 mAb (clone ab95363; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), an anti-GPC4 mAb (clone A21050B; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), and an anti-PA tag mAb (clone NZ-1 for GPC6) [

36], and sorted using SH800, respectively. After sorting, cultivation in a medium containing 0.5 mg/mL of Zeocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) or 0.5 mg/mL of G418 (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.) was progressed. These GPCs-overexpressed CHO-K1 (e.g., CHO/GPC1) clones were finally established.

2.2. Antibodies

An anti-Human/Mouse Glypican 5 Antibody (clone 297716, mouse IgG

2a) was purchased from R&D Systems, Inc. (Minneapolis, MN, USA). An anti-isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 (IDH1) mAb (clone RcMab-1) was developed previously in our lab [

37]. A secondary Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse, rat, and rabbit IgG was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Secondary horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and anti-rat IgG were obtained from Agilent Technologies Inc. (Santa Clara, CA, USA) and Merck KGaA (Darmstadt, Germany), respectively. The sources of commercially available anti-GPC antibodies are listed above.

2.3. Development of Hybridomas

For developing anti-GPC5 mAbs, two 6-week-old female BALB/cAJcl mice, purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan), were immunized intraperitoneally with 1 × 108 cells/mouse of LN229/GPC5. The LN229/GPC5 cells as immunogen were harvested after brief exposure to 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA; Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). Alhydrogel adjuvant 2% (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) was added as an adjuvant in the first immunization. Three additional injections of 1 × 108 cells/mouse of LN229/GPC5 were administered intraperitoneally without an adjuvant addition every week. A final booster injection was performed with 1 × 108 cells/mouse of LN229/GPC5 intraperitoneally two days before harvesting splenocytes from mice. We conducted cell-fusion of the harvested splenocytes from LN229/GPC5-immunized mice with P3U1 cells using polyethylene glycol 1500 (PEG1500; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) under heated conditions.

Hybridomas were cultured in the RPMI-1640 medium supplemented as shown above, with additional supplements including hypoxanthine, aminopterin, and thymidine (HAT; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 5% BriClone (NICB, Dublin, Ireland), and 5 μg/mL of Plasmocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA, USA) into the medium. The supernatants of hybridomas were screened by flow cytometric analysis using CHO/GPC5 and parental CHO-K1 cells. The hybridoma supernatant, containing G5Mab-1 in serum free-medium, was filtrated and purified using Ab-Capcher Extra (ProteNova, Kagawa, Japan).

2.4. Flow Cytometric Analysis

Cells were harvested using 1 mM EDTA. Subsequently, cells were washed with 0.1% bovine serum albumin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and treated with primary mAbs for 30 min at 4°C. Afterward, cells were treated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:1000) following the collection of fluorescence data using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer (Sony Corp.). Expression of GPCs in GPCs-overexpressed CHO-K1 cells in

Figure 3B was confirmed with specific antibodies, 0.5 µg/mL of an anti-GPC1 mAb (1019718) for CHO/GPC1, 0.5 µg/mL of an anti-GPC2 mAb (#90488) for CHO/GPC2, 0.466 µg/mL of an anti-GPC3 mAb (ab95363) for CHO/GPC3, 1.2 µg/mL of an anti-GPC4 mAb (A21050B) for CHO/GPC4, 0.5 µg/mL of an anti-GPC5 mAb (297716) for CHO/GPC5, 1 µg/mL of an anti-PA tag mAb (NZ-1) for CHO/GPC6, respectively.

2.5. Determination of Dissociation Constant (KD) by Flow Cytometry

CHO/GPC5 cells were suspended in 100 μL serially diluted G5Mab-1 (30 µg/mL to 0.002 µg/mL) and 297716 (an anti-human/mouse GPC5 mAb, 30 µg/mL to 0.002 µg/mL) after which Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:200) was treated. Fluorescence data were subsequently collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer, following the calculation of the dissociation constant (KD) by fitting the binding isotherms into the built-in one-site binding model in GraphPad PRISM 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

2.6. Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were boiled in sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.). Proteins (10 µg/lane) were electrophoresed on 5%–20% polyacrylamide gels (Wako) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Merck KGaA). After blocking with 4% non-fat milk (Nacalai Tesque, Inc.), PVDF membranes were incubated with 5 μg/mL of G5Mab-1, 5 μg/mL of 297716, 1 μg/mL of an anti-IDH1 mAb (RcMab-1), followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:2000; Agilent Technologies Inc.) or anti-rat IgG (1:10000; Merck KGaA). Chemiluminescence signals were developed using Pierce™ ECL Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and ImmunoStar LD (Wako). The signals were imaged with a Sayaca-Imager (DRC Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

2.7. Immunohistochemical Analysis

The CHO/GPC5 and CHO-K1 cell blocks were prepared using iPGell (Genostaff Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The paraffin-embedded cell sections were autoclaved in a citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Nichirei Biosciences, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). After blocking using the SuperBlock T20 Blocking Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), the sections were incubated with 1 μg/mL of G5Mab-1 and 1 μg/mL of 297716 and then treated with the Envision+ Kit (Agilent Technologies Inc.). Color was developed using 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Agilent Technologies Inc.), and counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany).

3. Results

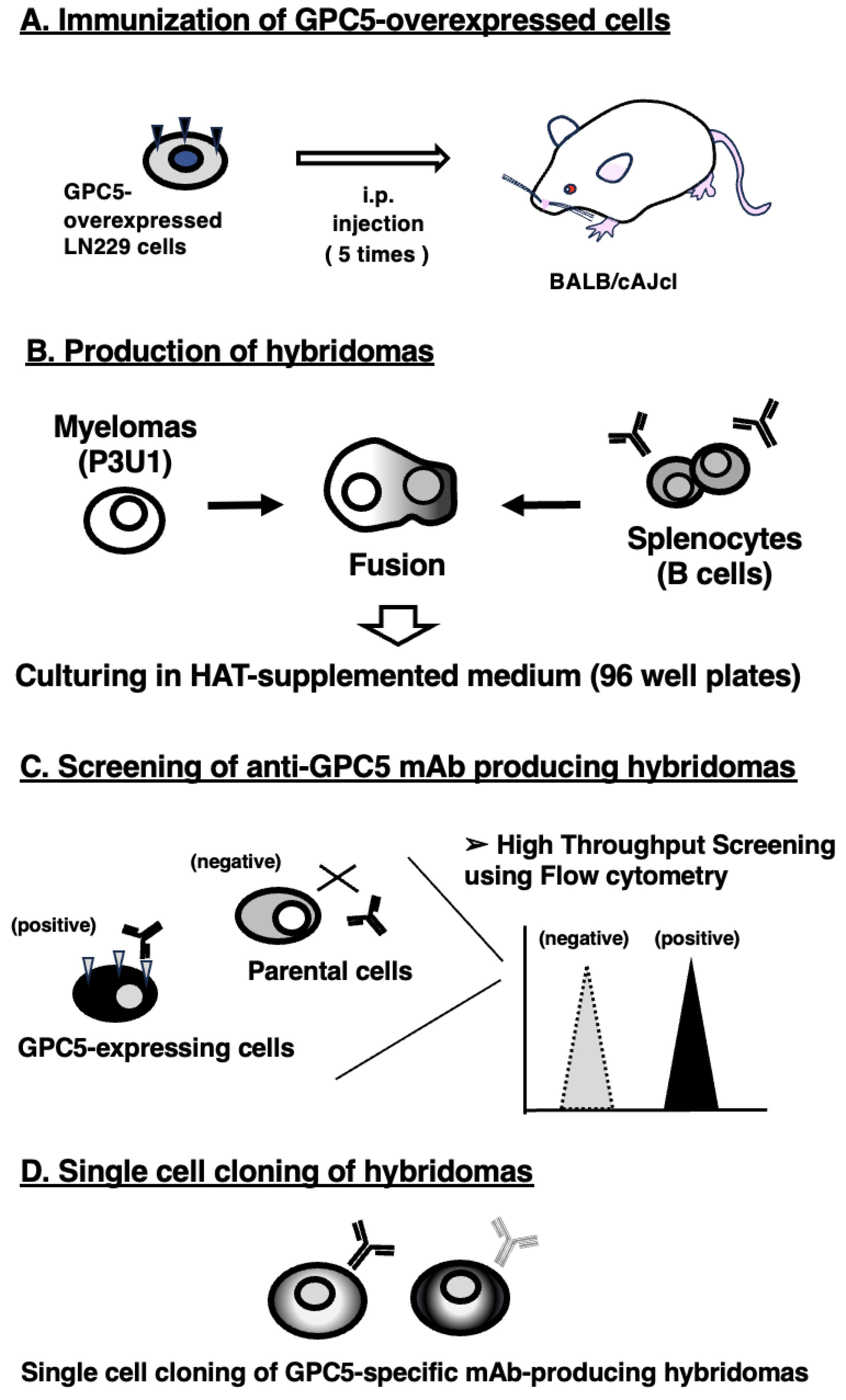

3.1. Development of Anti-GPC5 mAbs Using the CBIS Method

To establish anti-GPC5 mAbs, we employed the CBIS method using GPC5-overexpressed cells. Anti-GPC5 mAbs-producing hybridomas were screened by using flow cytometry (

Figure 1). Two female BALB/cAJcl mice were intraperitoneally immunized with LN229/GPC5 (1 × 10

8 cells/time/mouse) every week, 5 times. Subsequently, mouse splenocytes and P3U1 cells were fused by PEG1500. Hybridomas were seeded into 96-well plates, after which the flow cytometric screening was conducted to select CHO/GPC5-reactive and parental CHO-K1-nonreactive supernatants of hybridomas. We obtained some highly CHO/GPC5-reactive supernatants of hybridomas. We finally established the highly sensitive clone G

5Mab-1 (mouse IgG

1, kappa) by limiting dilution and additional analysis.

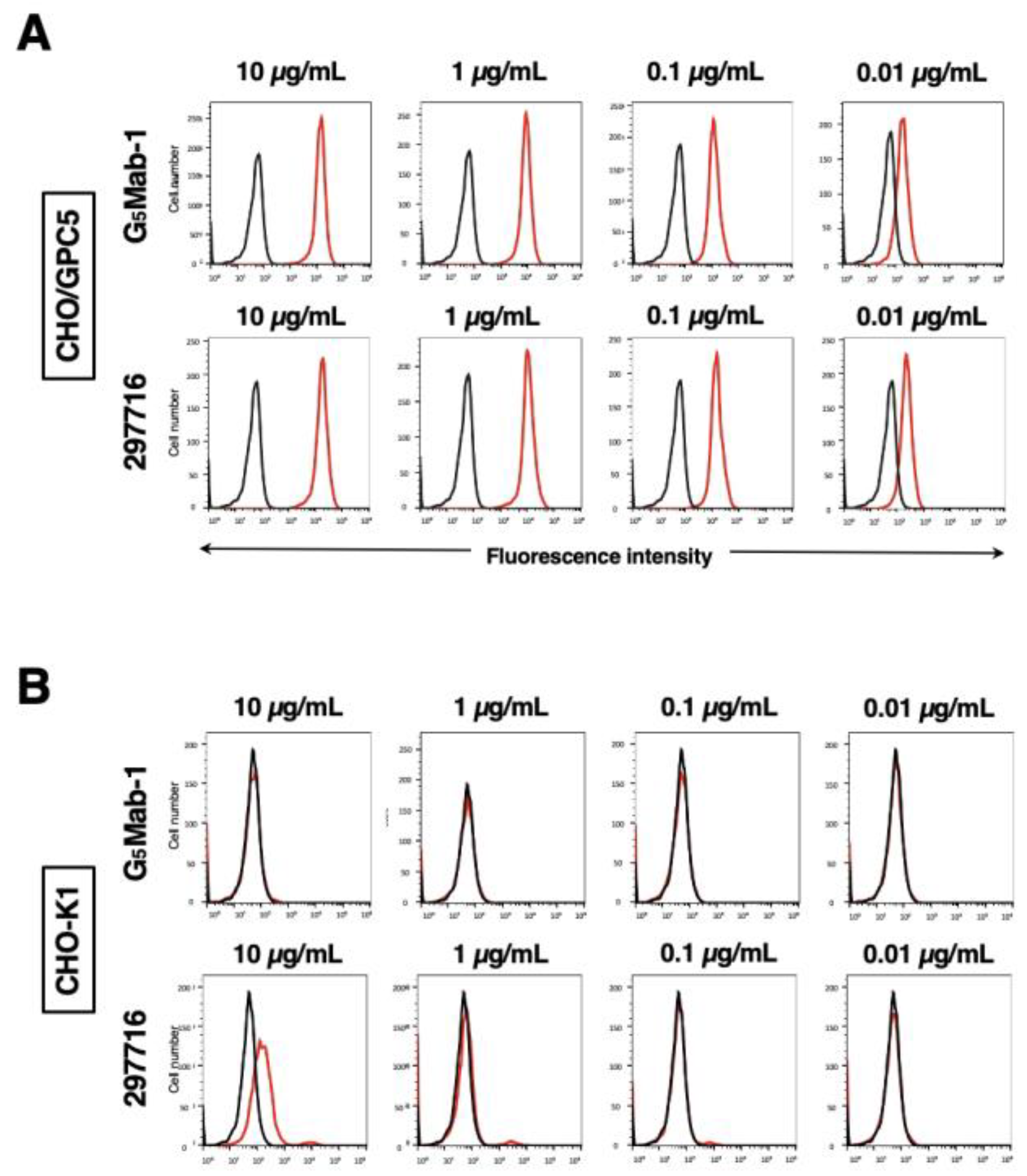

3.2. Evaluation of Antibody Reactivity and Specificity Using Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis was conducted using G

5Mab-1 and a commercially available anti-human/mouse GPC5 mAb (clone 297716) against CHO-K1 and CHO/GPC5 cells. Results indicated that G

5Mab-1 and 297716 recognized CHO/GPC5 dose-dependently (

Figure 2A). Reactivity is almost identical between G

5Mab-1 and 297716 to CHO/GPC5 (

Figure 2A). G

5Mab-1 did not react with parental CHO-K1 cells even at a concentration of 10 µg/mL (

Figure 2B). However, 297716 showed the reaction with CHO-K1 cells at a concentration of 10 µg/mL (

Figure 2B). Thus, G

5Mab-1 can detect GPC5, more specifically in flow cytometry.

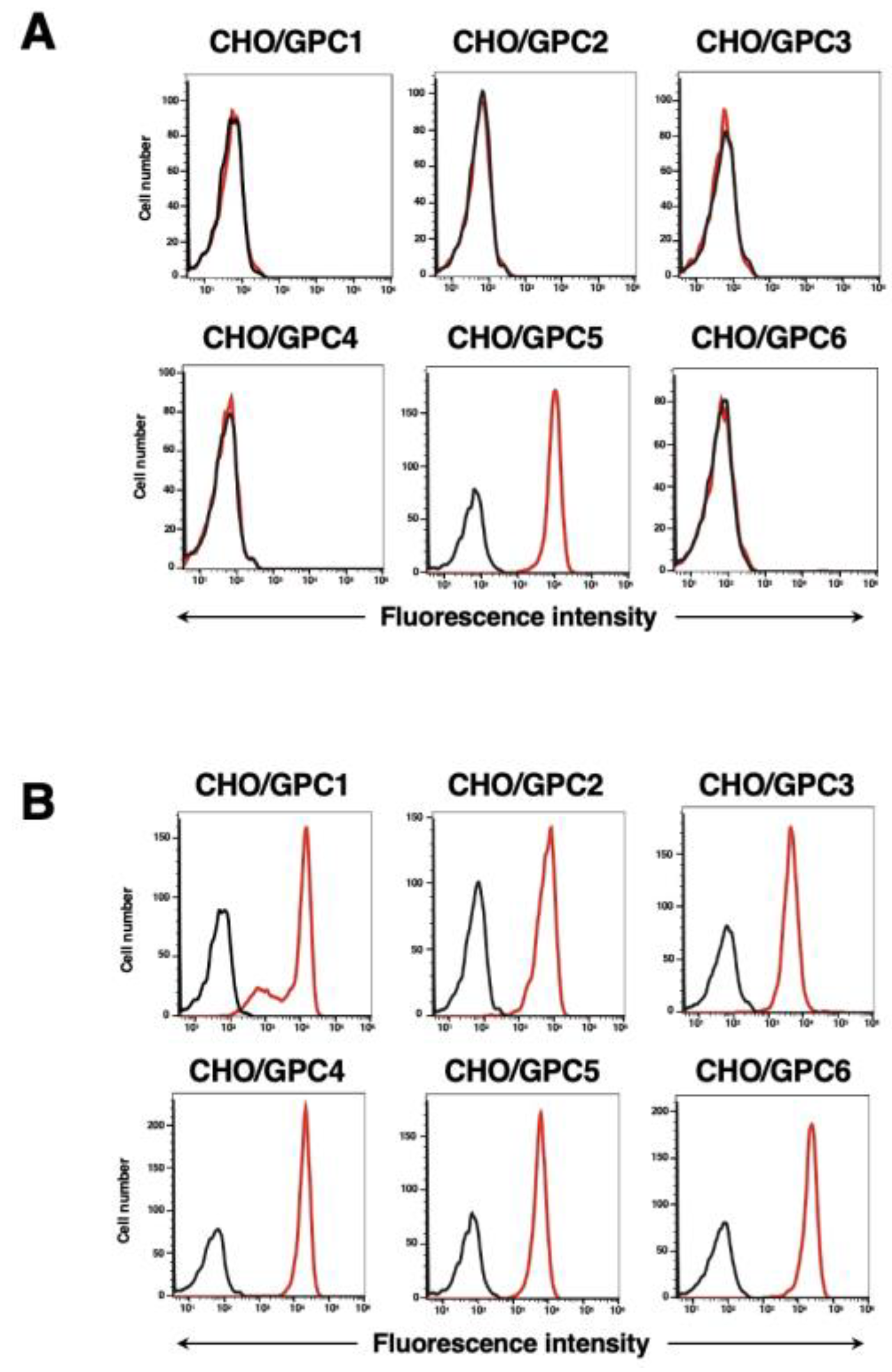

3.3. Specificity of G5Mab-1 to Glypican-Overexpressed CHO-K1 Cells

We have also established five other cell lines of GPCs-overexpressed CHO-K1 cells, such as CHO/GPC1, CHO/GPC2, CHO/GPC3, CHO/GPC4, and CHO/GPC6. Using the six cell lines, the specificity of G

5Mab-1 was analyzed. As shown in

Figure 3A, 10 µg/mL of G

5Mab-1 potently recognized CHO/GPC5, but not others. The expression of GPCs in all cell lines was confirmed by specific antibodies (

Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry of G5Mab-1 in GPCs-expressed CHO-K1 cells. CHO-K1 cells, which overexpressed each of the six GPCs, were treated with G5Mab-1 (10 µg/mL) (A) and specific antibodies for each GPCs (B) (red line). The black line shows the cells with control-blocking buffer treatment instead of primary antibody. After incubation with primary antibody or control blocking buffer, anti-mouse, rat, or rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 was treated. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

Figure 3.

Flow cytometry of G5Mab-1 in GPCs-expressed CHO-K1 cells. CHO-K1 cells, which overexpressed each of the six GPCs, were treated with G5Mab-1 (10 µg/mL) (A) and specific antibodies for each GPCs (B) (red line). The black line shows the cells with control-blocking buffer treatment instead of primary antibody. After incubation with primary antibody or control blocking buffer, anti-mouse, rat, or rabbit IgG conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 was treated. Fluorescence data were collected using the SA3800 Cell Analyzer.

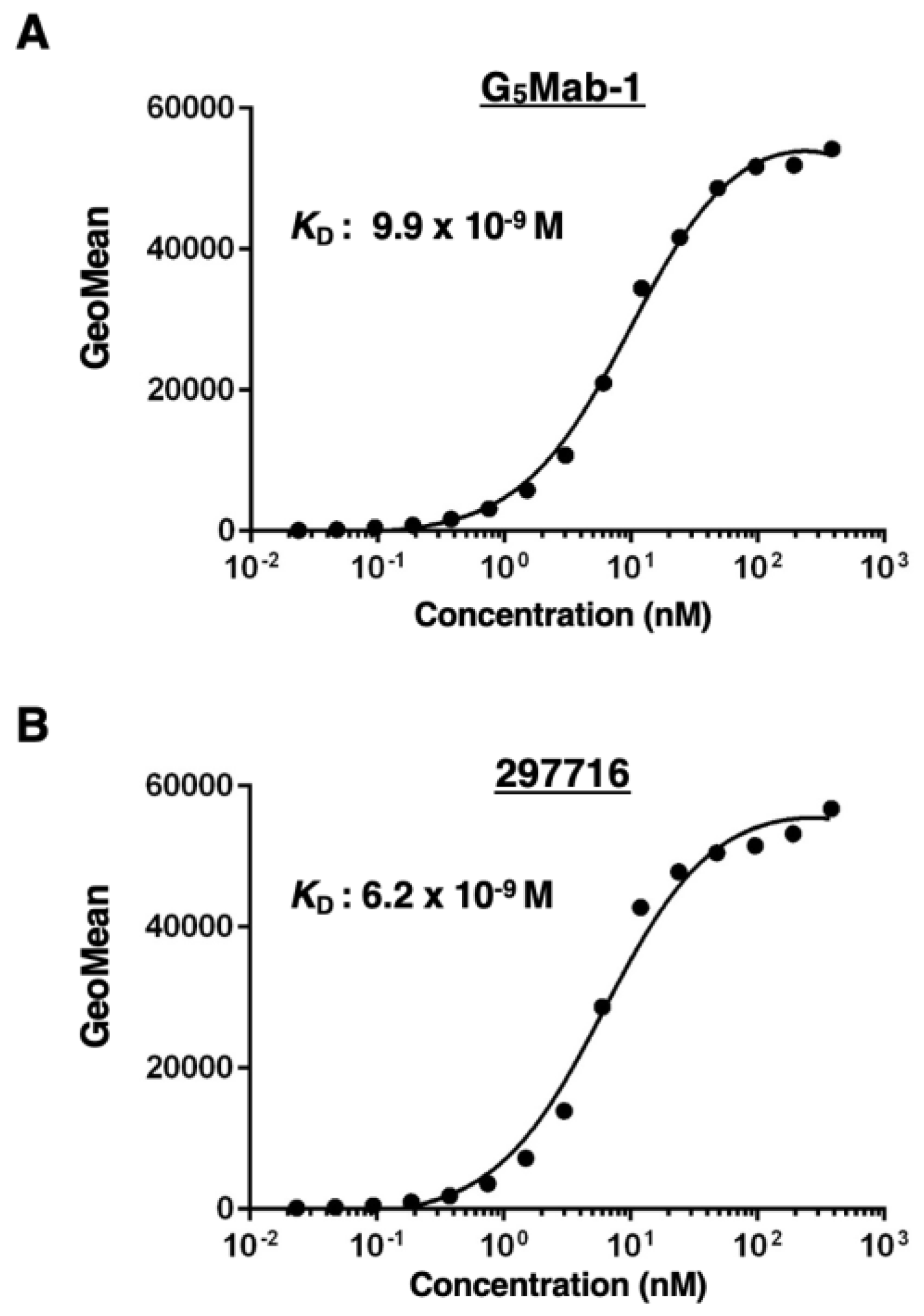

3.4. Calculation of the Apparent Binding Affinity of Anti-GPC5 mAbs Using Flow Cytometry

The binding affinity of G

5Mab-1 and 297716 was assessed with CHO/GPC5 using flow cytometry. The results indicated that the

KD value of G

5Mab-1 was 9.9×10

-9 M (

Figure 4A). The

KD value of 297716 was 6.2×10

-9 M (

Figure 4B). There was no noticeable difference in binding affinity for CHO/GPC5 between G

5Mab-1 and 297716. These results demonstrate that G

5Mab-1 can recognize GPC5 with moderate affinity to cell surface GPC5.

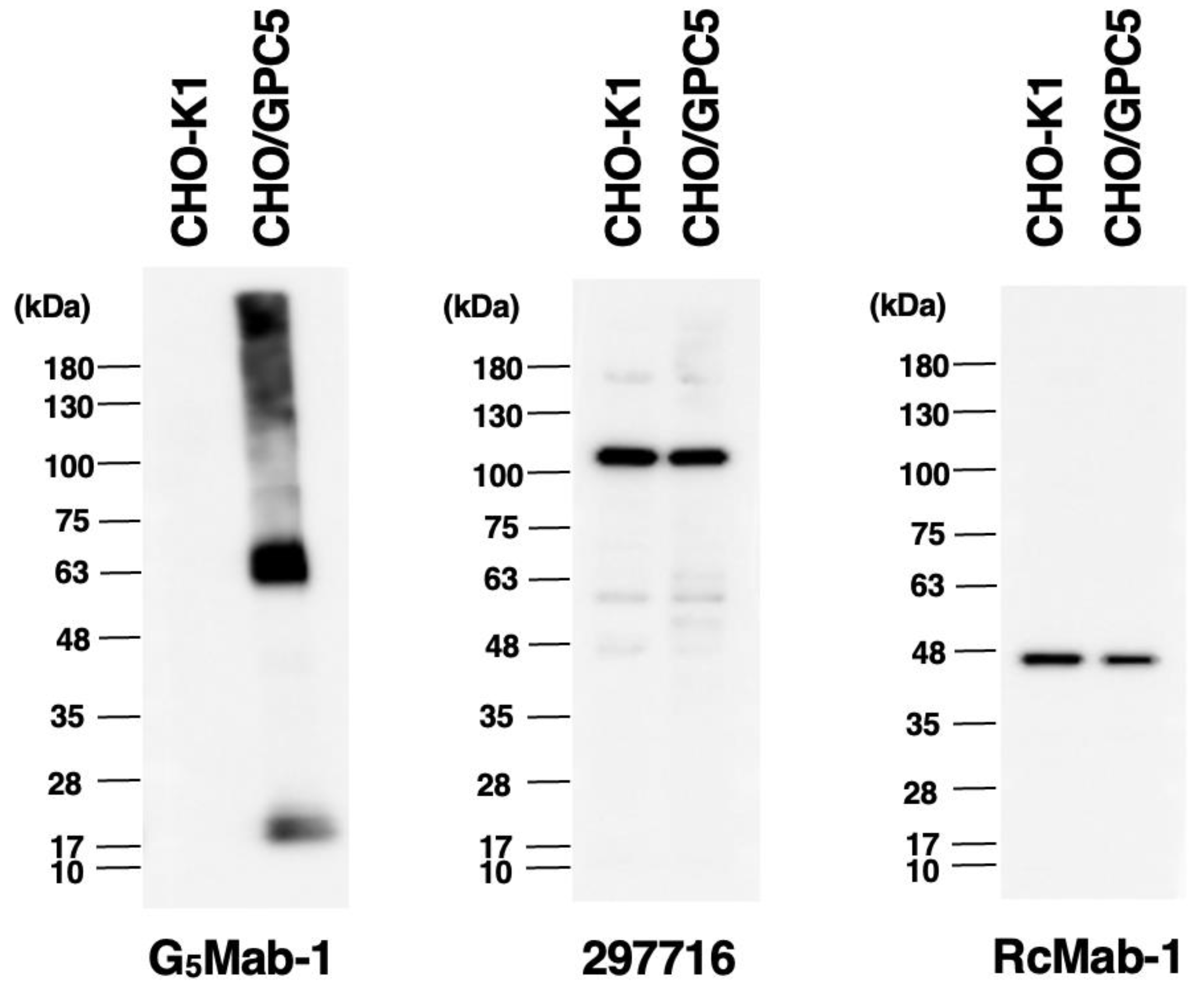

3.5. Western Blot Analyses Using Anti-GPC5 mAbs

We investigated whether G

5Mab-1 can be used for western blot analysis by analyzing CHO-K1 and CHO/GPC5 cell lysates. The estimated molecular weight of the GPC5 protein is approximately 60 kDa. As shown in

Figure 5, G

5Mab-1 could detect GPC5 as the major band around 63-kDa in CHO/GPC5 cell lysates, while no band was detected in parental CHO-K1 cells. Another anti-GPC5 mAb (clone 297716) could not detect GPC5 as the band around 63 kDa in CHO/GPC5 cell lysates. An anti-IDH1 mAb (clone RcMab-1) was used for internal control. These results indicate that G

5Mab-1 can detect GPC5 in GPC5-overexpressing cells in western blot analyses.

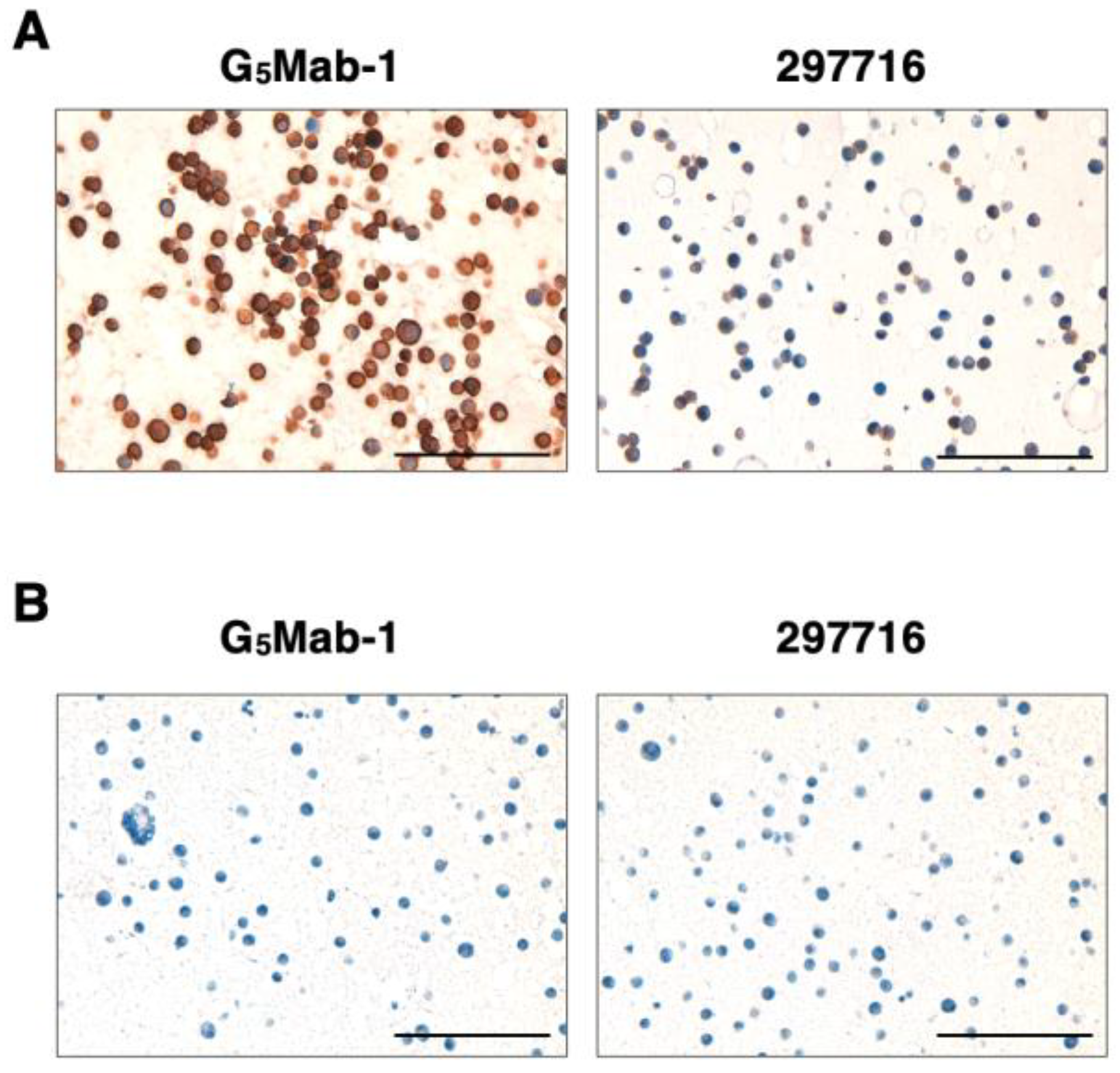

3.6. Immunohistochemistry Using Anti-GPC5 mAbs

To investigate whether G

5Mab-1 can be used for immunohistochemistry (IHC), paraffin-embedded CHO-K1 and CHO/GPC5 sections were stained with G

5Mab-1. Apparent membranous staining by G

5Mab-1 was observed in CHO/GPC5 (

Figure 6A). The 297716, another anti-GPC5 mAb, partially and weakly stained CHO/GPC5 sections (

Figure 6A). Both G

5Mab-1 and 297716 did not react with the CHO-K1 section. (

Figure 6B). These results indicate that G

5Mab-1 applies to IHC for detecting GPC5-positive cells in paraffin-embedded cell samples.

4. Discussion

We successfully developed a novel anti-human GPC5 mAb clone G5Mab-1 by the CBIS method. G5Mab-1 showed almost the same reactivity in flow cytometric analysis as 297716, a commercially available anti-GPC5 mAb (

Figure 2 and

Figure 4). G

5Mab-1 specifically recognized GPC5 but not other members of the GPC family (

Figure 3). Furthermore, in western blot and immunohistochemistry, G5Mab-1 clearly detected GPC5 under denaturing conditions (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). Contrary to the supplier data of 297716, we could not detect GPC5 in the western blot (

Figure 5). In immunohistochemical analyses, the sensitivity of the 297716 was much lower than that of the G

5Mab-1 (

Figure 6). Therefore, G

5Mab-1 is a versatile mAb and will contribute to the biological analysis of GPC5 and its diagnosis. Some reports have described that GPC5 overexpression promotes tumor malignancy [

6,

16,

38]. GPC5 may be a therapeutic target for cancer. In our previous reports, we will convert G

5Mab-1 (mouse IgG

1) to IgG

2a version to confer antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity activity for evaluating antitumor effects in future study [

39,

40,

41].

GPC3 is currently considered the most promising cancer antigen in the GPC family. Codrituzumab (GC33), an anti-GPC3 mAb, has been treated in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients in a phase I clinical study. Codrituzumab treatment was effective in some patients with high GPC3 expression, but no benefit was obtained in the subsequent phase II trials [

42,

43,

44]. A chimeric antigen receptor-T (CAR-T) targeting GPC3 has also been developed for cancer treatment [

45]. No treatments targeting GPC5 have been reported yet. Within the GPC family, the amino acid sequence homology between GPC3 and GPC5 is 43%, and the N-terminus shows a relatively high homology of 54% [

46]. The C-terminal Ser-Gly repeating glycosylation sites between GPC3 and GPC5 are also similarly positioned [

14]. Like GPC5, GPC3 regulates many cancer-progressive cascades, including Wnt, hedgehog, and FGF [

47,

48,

49,

50]. Although further verification is required, these findings suggest that GPC5 may become one of the critical regulators of cancer. G

5Mab-1 can be a valuable tool for versatile analysis of GPC5 in cancer research.

In addition to heparan sulfate attachment, GPC1 and GPC3 have sites for

N-glycosylation in the extracellular domain [

51,

52]. Glycosylation of proteins often regulates cell functions through protein folding, stability, and signaling. Aberrant glycosylation is involved in the progression of diseases [

53]. Considering the amino acid homology among the GPC family, glycosylation might also affect the function of GPC5. Previously, we have developed a cancer-specific mAb targeting podoplanin (PDPN) clone LpMab-2 by immunizing LN229 glioblastoma cells-derived PDPN [

54]. The epitope of LpMab-2 includes

O-glycosylation of PDPN expressed in cancer cells. Using a similar method to produce mAb against GPC5 may clarify the relationship between GPC5 and glycosylation in cancers. Furthermore, we have successfully established a cancer-specific anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) mAb, clone H

2Mab-214, by immunizing LN229-producing HER2 ectodomain [

55]. The H

2Mab-214 recognizes disrupted structure in HER2 domain IV, a cancer-specific epitope, rather than glycosylation. In future studies, we intend to identify whether cancer-specific GPC5 structures and modifications exist by further developing anti-GPC5 mAbs using the same strategy.

Author Contributions

Yu Kaneko: Investigation. Tomohiro Tanaka: Investigation, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft. Shiori Fujisawa: Investigation. Guanjie Li: Investigation. Hiroyuki Satofuka: Investigation, Funding acquisition. Mika K. Kaneko: Conceptualization. Hiroyuki Suzuki: Funding acquisition, Writing – review and editing. Yukinari Kato: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing – review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) under Grant Numbers: JP24am0521010 (to Y.Kato), JP24ama121008 (to Y.Kato), JP24ama221339 (to Y.Kato), JP24bm1123027 (to Y.Kato), and JP24ck0106730 (to Y.Kato), and by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) grant nos. 22K06995 (to H.Suzuki), 21K20789 (to T.T.), 24K11652 (to H.Satofuka), and 22K07224 (to Y.Kato).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Tohoku University (Permit number: 2022MdA-001) for studies involving animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All related data and methods are presented in this paper. Additional inquiries should be addressed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest involving this article.

References

- Song, H.H.; Filmus, J. The role of glypicans in mammalian development. Biochim Biophys Acta 2002, 1573, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cat, B.; David, G. Developmental roles of the glypicans. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2001, 12, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernfield, M.; Götte, M.; Park, P.W.; et al. Functions of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Annu Rev Biochem 1999, 68, 729–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paine-Saunders, S.; Viviano, B.L.; Saunders, S. GPC6, a novel member of the glypican gene family, encodes a product structurally related to GPC4 and is colocalized with GPC5 on human chromosome 13. Genomics 1999, 57, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarrazin, S.; Lamanna, W.C.; Esko, J.D. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2011, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Shi, W.; Capurro, M.; Filmus, J. Glypican-5 stimulates rhabdomyosarcoma cell proliferation by activating Hedgehog signaling. J Cell Biol 2011, 192, 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmus, J.; Capurro, M. The role of glypicans in Hedgehog signaling. Matrix Biol 2014, 35, 248–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Moraes, G.F.A.; Listik, E.; Justo, G.Z.; Vicente, C.M.; Toma, L. The Glypican proteoglycans show intrinsic interactions with Wnt-3a in human prostate cancer cells that are not always associated with cascade activation. BMC Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saunders, S.; Paine-Saunders, S.; Lander, A.D. Expression of the cell surface proteoglycan glypican-5 is developmentally regulated in kidney, limb, and brain. Dev Biol 1997, 190, 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luxardi, G.; Galli, A.; Forlani, S.; et al. Glypicans are differentially expressed during patterning and neurogenesis of early mouse brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007, 352, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handel, A.E.; Ramagopalan, S.V. GPC5 and lung cancer in multiple sclerosis. Lancet Oncol 2010, 11, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mowry, E.M.; Carey, R.F.; Blasco, M.R.; et al. Multiple sclerosis susceptibility genes: associations with relapse severity and recovery. PLoS One 2013, 8, e75416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Spetz, M.R.; Ho, M. The Role of Glypicans in Cancer Progression and Therapy. J Histochem Cytochem 2020, 68, 841–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, M.; Vermeesch, J.; Reekmans, G.; et al. Characterization of glypican-5 and chromosomal localization of human GPC5, a new member of the glypican gene family. Genomics 1997, 40, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ota, A.; Tagawa, H.; Karnan, S.; et al. Identification and characterization of a novel gene, C13orf25, as a target for 13q31-q32 amplification in malignant lymphoma. Cancer Res 2004, 64, 3087–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Miao, L.; Cai, H.; et al. The overexpression of glypican-5 promotes cancer cell migration and is associated with shorter overall survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Lett 2013, 6, 1565–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojopi, E.P.; Rogatto, S.R.; Caldeira, J.R.; Barbiéri-Neto, J.; Squire, J.A. Comparative genomic hybridization detects novel amplifications in fibroadenomas of the breast. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 2001, 30, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.; Selfe, J.; Gordon, T.; et al. Role for amplification and expression of glypican-5 in rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res 2007, 67, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, P. GPC5 gene and its related pathways in lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol 2011, 6, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, M.; Takeuchi, K.; Takai, T.; et al. Subcellular localization of glypican-5 is associated with dynamic motility of the human mesenchymal stem cell line U3DT. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0226538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, D.; et al. A lung cancer gene GPC5 could also be crucial in breast cancer. Mol Genet Metab 2011, 103, 104–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; et al. Prognostic significance of GPC5 expression in patients with prostate cancer. Tumour Biol 2016, 37, 6413–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Zhang, Z.; Pan, L.; et al. MicroRNA-301b promotes the proliferation and invasion of glioma cells through enhancing activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling via targeting Glypican-5. Eur J Pharmacol 2019, 854, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yin, X.; et al. miR-297 acts as an oncogene by targeting GPC5 in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Prolif 2016, 49, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Xu, K.; He, M.; Fan, G.; Lu, H. Overexpression of Glypican 5 (GPC5) Inhibits Prostate Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion via Suppressing Sp1-Mediated EMT and Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Oncol Res 2018, 26, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; et al. GPC5 suppresses lung cancer progression and metastasis via intracellular CTDSP1/AhR/ARNT signaling axis and extracellular exosome secretion. Oncogene 2021, 40, 4307–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Qiu, M.; et al. Glypican-5 is a novel metastasis suppressor gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Lett 2013, 341, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Sheu, C.C.; Ye, Y.; et al. Genetic variants and risk of lung cancer in never smokers: a genome-wide association study. Lancet Oncol 2010, 11, 321–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Q.; et al. GPC5, a novel epigenetically silenced tumor suppressor, inhibits tumor growth by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin signaling in lung adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 2016, 35, 6120–6131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Z.; Han, C.; Liu, J.; et al. GPC5, a tumor suppressor, is regulated by miR-620 in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Med Rep 2014, 9, 2540–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zhang, X.; Sha, K.; et al. miR-709 up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma, promotes proliferation and invasion by targeting GPC5. Cell Prolif 2015, 48, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamada, S.; Itai, S.; Nakamura, T.; et al. Monoclonal Antibody L(1)Mab-13 Detected Human PD-L1 in Lung Cancers. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2018, 37, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, H.; Tanaka, T.; Kudo, Y.; et al. A Rat Anti-Mouse CD39 Monoclonal Antibody for Flow Cytometry. Monoclon Antib Immunodiagn Immunother 2023, 42, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Suzuki, H.; Asano, T.; et al. Development of a Novel Anti-EpCAM Monoclonal Antibody for Various Applications. Antibodies (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Ohishi, T.; Asano, T.; et al. An anti-TROP2 monoclonal antibody TrMab-6 exerts antitumor activity in breast cancer mouse xenograft models. Oncol Rep 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, Y.; Kaneko, M.; Neyazaki, M.; et al. PA tag: a versatile protein tagging system using a super high affinity antibody against a dodecapeptide derived from human podoplanin. Protein Expr Purif 2014, 95, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikota, H.; Nobusawa, S.; Arai, H.; et al. Evaluation of IDH1 status in diffusely infiltrating gliomas by immunohistochemistry using anti-mutant and wild type IDH1 antibodies. Brain Tumor Pathol 2015, 32, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, M.H.; Have, C.; Hoang, L.N.; et al. Genomic profiling identifies GPC5 amplification in association with sarcomatous transformation in a subset of uterine carcinosarcomas. J Pathol Clin Res 2018, 4, 69–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. Antitumor activities of a defucosylated anti-EpCAM monoclonal antibody in colorectal carcinoma xenograft models. Int J Mol Med 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; Kaneko, M.K.; Kato, Y. Antitumor activities against breast cancers by an afucosylated anti-HER2 monoclonal antibody H(2) Mab-77-mG(2a) -f. Cancer Sci 2024, 115, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaneko, M.K.; Suzuki, H.; Ohishi, T.; et al. A Cancer-Specific Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 Exerts Antitumor Activities in Human Breast Cancer Xenograft Models. Int J Mol Sci, 2024; 25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, A.X.; Gold, P.J.; El-Khoueiry, A.B.; et al. First-in-man phase I study of GC33, a novel recombinant humanized antibody against glypican-3, in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19, 920–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, M.; Ohkawa, S.; Okusaka, T.; et al. Japanese phase I study of GC33, a humanized antibody against glypican-3 for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci 2014, 105, 455–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou-Alfa, G.K.; Puig, O.; Daniele, B.; et al. Randomized phase II placebo controlled study of codrituzumab in previously treated patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2016, 65, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, D.; Shi, Y.; Kaseb, A.O.; et al. Chimeric Antigen Receptor-Glypican-3 T-Cell Therapy for Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Results of Phase I Trials. Clin Cancer Res 2020, 26, 3979–3989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veugelers, M.; De Cat, B.; Ceulemans, H.; et al. Glypican-6, a new member of the glypican family of cell surface heparan sulfate proteoglycans. J Biol Chem 1999, 274, 26968–26977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, M.I.; Xiang, Y.Y.; Lobe, C.; Filmus, J. Glypican-3 promotes the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma by stimulating canonical Wnt signaling. Cancer Res 2005, 65, 6245–6254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.; Tang, Z.; Zhang, Y.F.; et al. Immunotoxin targeting glypican-3 regresses liver cancer via dual inhibition of Wnt signalling and protein synthesis. Nat Commun 2015, 6, 6536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurro, M.I.; Xu, P.; Shi, W.; et al. Glypican-3 inhibits Hedgehog signaling during development by competing with patched for Hedgehog binding. Dev Cell 2008, 14, 700–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grisaru, S.; Cano-Gauci, D.; Tee, J.; Filmus, J.; Rosenblum, N.D. Glypican-3 modulates BMP- and FGF-mediated effects during renal branching morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2001, 231, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Awad, W.; Adamczyk, B.; Örnros, J.; et al. Structural Aspects of N-Glycosylations and the C-terminal Region in Human Glypican-1. J Biol Chem 2015, 290, 22991–23008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cat, B.; Muyldermans, S.Y.; Coomans, C.; et al. Processing by proprotein convertases is required for glypican-3 modulation of cell survival, Wnt signaling, and gastrulation movements. J Cell Biol 2003, 163, 625–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steigmeyer, A.D.; Lowery, S.C.; Rangel-Angarita, V.; Malaker, S.A. Decoding Extracellular Protein Glycosylation in Human Health and Disease. Annu Rev Anal Chem (Palo Alto Calif) 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Kaneko, M.K. A Cancer-specific Monoclonal Antibody Recognizes the Aberrantly Glycosylated Podoplanin. Scientific Reports 2014, 4, 5924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arimori, T.; Mihara, E.; Suzuki, H.; et al. Locally misfolded HER2 expressed on cancer cells is a promising target for development of cancer-specific antibodies. Structure 2024, 32, 536–549.e535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).