1. Introduction

Due to the approximately 30% global industrial CO

2 emissions contribution from steel manufacturing industries [

1], the replacement of conventional production routes and the application of less consumption steel production process improvements have become unstoppable and sustainable for decarbonization and sustainability targets. The compact strip production (CSP) technology is a thin slab near-net shape-forming technology that involves continuous casting of thin slabs and direct strip shot rolling [

2]. Since the compact procedures with continuous casting and the absence of a reheating process prior to hot rolling, energy consumption, and CO

2 emissions are systematically reduced in the CSP process [

3]. Steels such as hot-rolled low-carbon steels and high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steels have already occupied CSP market supplication for decades [

4], and in recent years more steel grades containing higher alloy compositions and complex phases have been attracted by the CSP process since the considerable chemical and microstructural homogeneity of the CSP slab [

5].

Advanced High-Strength Steels (AHSS) such as complex phase (CP) steels are the mainstream applications in the automotive industries [

6] where hot-rolled products have a good appetite for the CSP application. Based on the CSP process features, many researchers are engaged in studying the metallurgical design, microstructure dynamic revolution, and properties consistency optimization mechanism on AHSS steels [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, there is a common argument in inhomogeneous grain refinements during the CSP process. Zhu et. al [

13] considered the lack of homogenizing in the reheating procedure in the CSP process would result in mixed grain size. Dong et. al [

14] also believe that the mixed grain structures would occur in Nb micro alloyed CSP strip if consideration of the setting of temperatures and allocation deformation were made improperly. The investigation from DeArdo et. al [

15] and Romano-Acosta et. al [

16] agree with the same arguments, and they improve the mixed grain structures by upwards the deformation temperatures to T95 (recrystallization-limit temperature) to complete recrystallization. These studies found the problem and improvements through semi-practical and experimental methods but didn’t give a precise solution in a universal way that could put forward guidance on the processing.

The establishment of the recrystallization kinetic equation is a widely accepted mathematical method to simulate the austenite evolution during hot deformation which could help address the advancement. Compared to the conventional rolling process, the CSP process has higher reductions per pass with generally lower strain rates since CSP has fewer passes and endless production [

17]. This feature suggests that metadynamic recrystallization would be more likely to take place in the subsequent interpass time after dynamic recrystallization during deformation rather than static recrystallization [

18]. Therefore, metadynamic recrystallization is the main softening mechanism that changes grain characteristics and relevant mechanical properties in the CSP process. However, little information is available regarding metadynamic recrystallization, either in behavior or recommended applications. Some works were only focused on the effect of hot deformation parameters on dynamic recrystallization and didn’t catch the tint of the importance meaning of metadynamic softening between passes [

19,

20]. Liu et. al [

21] have proposed a well-fitting kinetics equation to characterize the metadynamic recrystallization behavior of 300M steel, but a detailed discussion wasn’t given for further optimization for processing. Tang et. al [

22] did a complete discussion on the recrystallization behavior during the CSP process on 510L steel, while the deformation temperatures are relatively lower than the AHSS steel production. Some works were based on the combination of lab experiments and trial production such as high-carbon bainitic steel [

23] and Fe-Mn-Al-C steels [

24] which showed an insight into the practical of semi-industrial mathematical predicted models. Hence, it is necessary to establish a foundation of metadynamic recrystallization behavior based on CSP process features to fill the blank and promote the CSP applications in AHSS steels.

In this study, the metadynamic softening behavior of a CP800 steel which is prepared for the application CSP process was investigated through the isothermal double compression. The softening behavior was discussed through the flow stress-strain curves under the different deformation conditions. The kinetic simulation of metadynamic recrystallization is proposed with the experimental results. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis of two different sizes of initial austenite grains helped demonstrate the grain size refinement effect. These analyses could deepen the recognition of the metadynamic softening behavior of CP800 steel and put forward efficient recommendations on the procedures during the manufacturing process.

2. Materials and Methods

The experimental material CP800 steel manufactured by continuous casting with the composition (wt.%) of 0.05C-0.25Si-1.5Mn-0.12Ti-0.4Cr-Fe was used in this study. The Ac1 and Ac3 temperatures of CP800 steel are 943 K and 1183 K, respectively, according to the rate of 0.05 K/s heating condition dilatometric measurements with a diameter of 4 mm × 10 mm length cylinder.

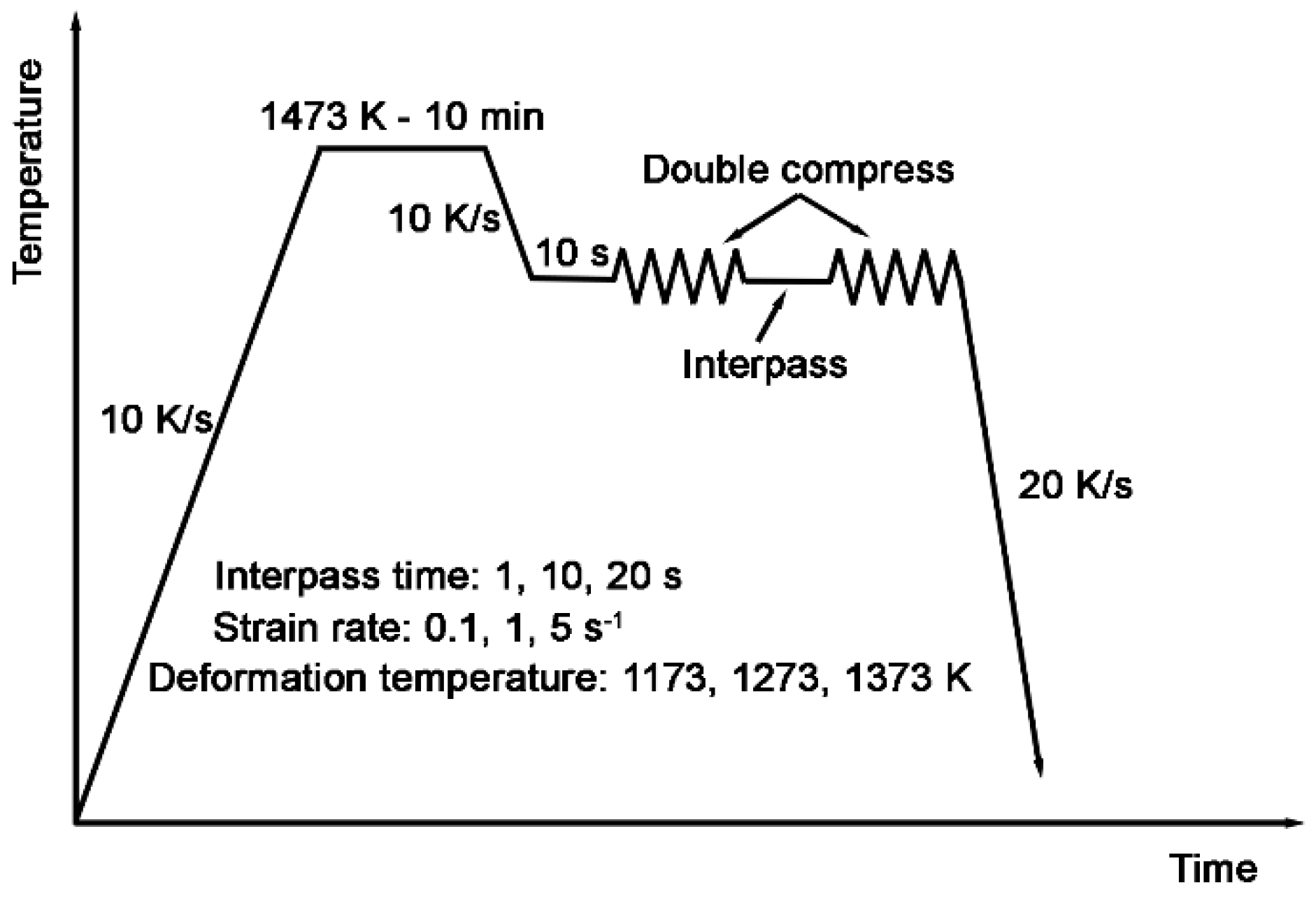

Compression experiments were tested on the Gleeble 3500 thermal simulation system using the cylindrical sample size of φ10 mm × 15 mm, and the lubricant was used at both ends of the cylinder to reduce the effect of friction during compression. Samples were heated at 10 K/s from room temperature to 1473 K and held for 10 min to homogenize the chemical composition and the austenite grains. Then cooled at 10 K/s to the compress deformation temperatures and isothermal held for 10s for the stabilization of the deformation condition. Next, the compression was conducted at the deformation temperatures of 1173 K, 1273 K, and 1373 K, with strain rates of 0.1 s

−1, 1 s

−1, and 5 s

−1, and a strain of 0.5, which is commonly over the value of critical strain of dynamic recrystallization and make sure the metadynamic recrystallization occurs between passes. The specimens were held for interpass time of 1 s, 10 s, and 20 s before the isothermal second compression. After double compression, the specimens were rapidly cooled through blow air in the chamber and the cooling rate was around 20 K/s to preserve the austenite grain size. The process is detailed shown in

Figure 1.

Metallographic samples for grain size statistically were cut from the middle of deformed specimens. The final microstructures are captured by a laser confocal microscope (OLS4100), and average grain size is measured by Image J software according to the line intercept methods [

25].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Flow stress-strain behavior in CP800 steel

3.1.1. Subsubsection

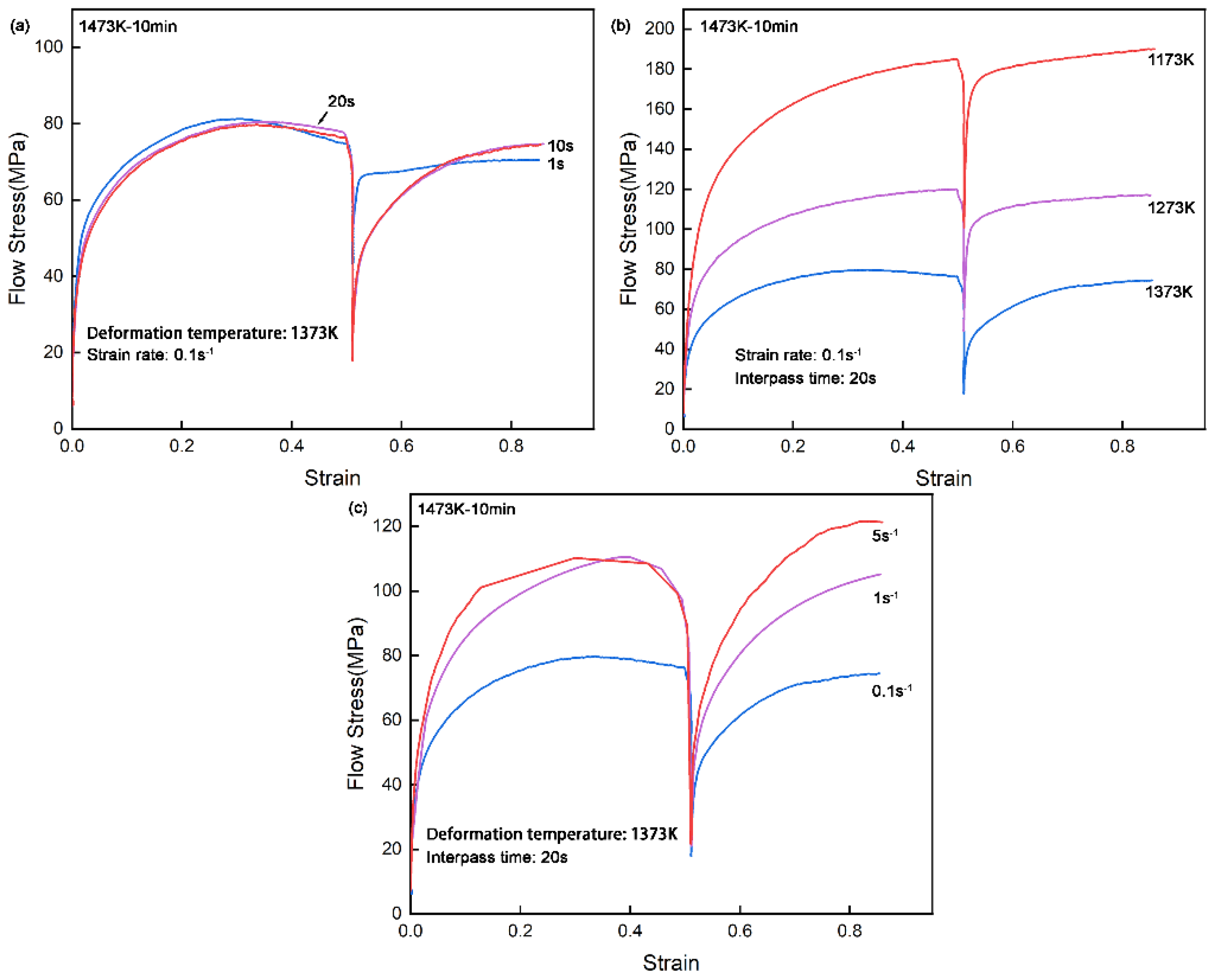

Figure 2 presents the flow stress-strain curves under double isothermal compression of CP800 steel at different interpass times, deformation temperatures, and strain rates. The yield flow stress in the first compression of each curve is lower than that in the second compression. It is suggested that a higher density of dislocations is introduced during the first compression which requires a higher stress in order to overcome the resistance of movable dislocations when applying the second compression [

26,

27].

It can be clearly seen that in

Figure 2a, the softening effect is more obvious with the prolongation of interpass time since the second yield stress decreases. Besides, the second compression curves overlap each other and are both the same as the first compression curves when 10 s and 20 s interpass time, which means a consistent and fully metadynamic softening happens between the interpass. In other words, the metadynamic recrystallization should finished within 10 s under compress conditions of 1373 K and 0.1 s

-1 strain rate. This also indicates that the increment that may have occurred in the recrystallization grains size during this additional 10 s gap time did not have an impact on the compressive deformation behavior of the second pass, or the increment was tiny with negligible effect. It is also known from

Figure 2a that the peak stress of the second compress is slightly lower than that of the first pass, which is due to the dynamic recrystallization that occurs in the first pass judging from the profile of the curve. The nucleation of dynamic recrystallization in the first compression reduces the dislocation density of the material contributing to the reduced peak stress of the second pass [

21,

28].

Figure 2b shows the second flow stress is slightly lower compared with the first pass in each curve, and that the decrease trend is gradually significant when the deformation temperature increases from 1173 K to 1373 K. The progressively softening effect of metadynamic recrystallization and the increased softening rate of the material should take responsibility for this phenomenon [

29,

30].

Figure 2c indicates CP800 is more prone to go through a highly metadynamic recrystallization under a 5 s

-1 strain rate than under 0.1 s

-1, according to the second peak stress. It is reasonable to say that the softening driving force is positively influenced by the high deformation strain rates, and these could all be decisively instructed by the dislocation behavior. Moreover, the flow stress decreases with the increase of the deformation temperatures shown in

Figure 2b and the decreasing strain rate in

Figure 2c, which is related to the material's intrinsic properties such as work hardening behavior in different temperatures or strain rates, and the influence of dislocations is also indispensable.

3.2. Process effect on the metadynamic softening of CP800 steel

The quantification of the metadynamic softening behavior between passes supports the understanding of the high-temperature compression character of CP800 steel. The experimental-based calculation can be adopted by the 0.2% offset-stress method [

31,

32]. The metadynamic softening fraction (F

s) is defined as follows:

where σ

m is the flow stress at the end of the first deformation, and σ

1 and σ

2 are the yield stresses determined at an offset strain of 0.2% for the first and second compression respectively.

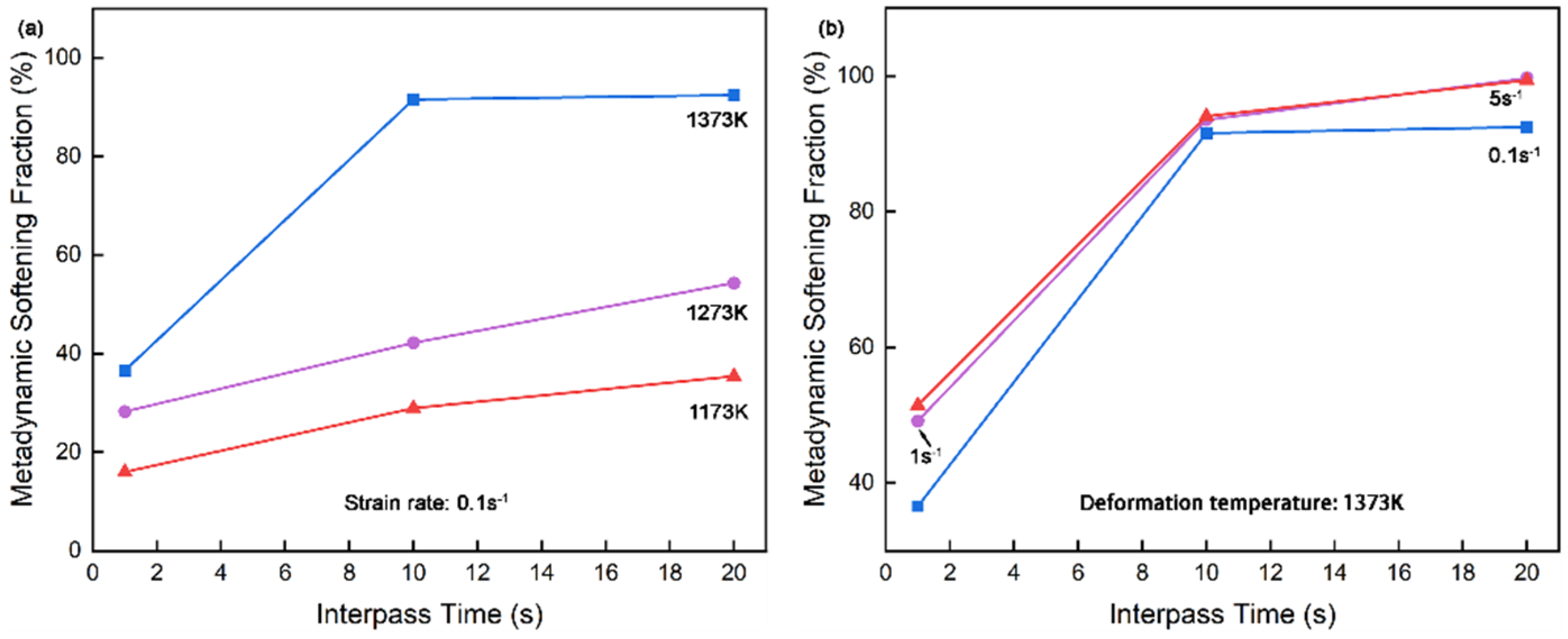

Figure 3a shows the metadynamic softening fraction of CP800 steel at the strain rate of 0.1 s

-1 varied with the deformation temperatures and interpass time. The fraction of metadynamic softening increased from 16%, 29%, and 35% followed by the increasing interpass time on 1173 K. The same trending is observed in 1273 K (28%, 42%, and 54%) and 1373 K (37%, 91%, and 92%) curves, while 1373 K achieves almost fully metadynamic softening at 10 s and 20 s interpass time, which is consistence with the analysis on

Figure 2a. It seems the fraction of metadynamic softening instinct by interpass time, but the softening fraction is only around 35% at a deformation temperature of 1173 K and an inter-pass time of 20 s. The climbing trend is going gentle along with the interpass time lasting in 1173 K and 1273 K curves, which is reasonable considering that the full metadynamic softening cannot occur at these deformation conditions. This could be strong evidence to say that metadynamic recrystallization is a thermally activated process [

33] in that higher temperatures enable support activating more atoms likely to jump out of the stubborn position and the migration of the boundary. Additionally, the metadynamic softening fraction increases with the increasing deformation temperature at the same interpass time which implies the deformation temperatures also influence the rate of metadynamic softening behavior.

The relationship between strain rate and metadynamic softening fraction at 1373 K is displayed in

Figure 3b fluctuating with different interpass times. More grains are going through the metadynamic softening at higher strain rates of 1 s

-1 and 5 s

-1 rather than 0.1 s

-1. Although the soften fraction at a strain rate of 1 s

-1 are average of about 2% less than 5 s

-1 at interpass time 1 s, they are finally identical at the interpass time of 10 s of 94% and 20 s of 99%. CP800 could fully recrystallize during passes under this deformation condition. However, in the strain rate of 0.1s

-1, the metadynamic softening fraction could only reach about 92% which means the difficulty of the metadynamic recrystallization in a lower strain rate such as 0.1 s

-1 even given a longer interpass time, not to mention under lower deformation temperatures. Higher strain rates always introduce more dislocations in steels [

34,

35] which could prove the high stress in the first compression of the 5 s

-1 stress-strain curve shown in

Figure 2c. The high density of dislocations provides sufficient energy to dominate the competition between dynamic softening and work hardening which increases the driving force for metadynamic recrystallization.

3.3. Kinetic study of the metadynamic recrystallization of CP800 steel

The recrystallization is usually assumed to start when the softening fraction F

s = 0.2 [

36], and the fraction of metadynamic recrystallization (X

m) is determined as follows:

The classic Avrami equation [

37,

38,

39] is used to analyze the kinetic behavior of metadynamic recrystallization in this study. The equation is defined as:

Where t is the interpass time (s), t

0.5 is the time (s) for 50% metadynamic recrystallization, n is the constant parameter dependent on the material. The above formula describes the metadynamic recrystallization kinetics mainly influenced by t

0.5 and n, which can be seen clearly after taking the natural logarithm in Eq. (3):

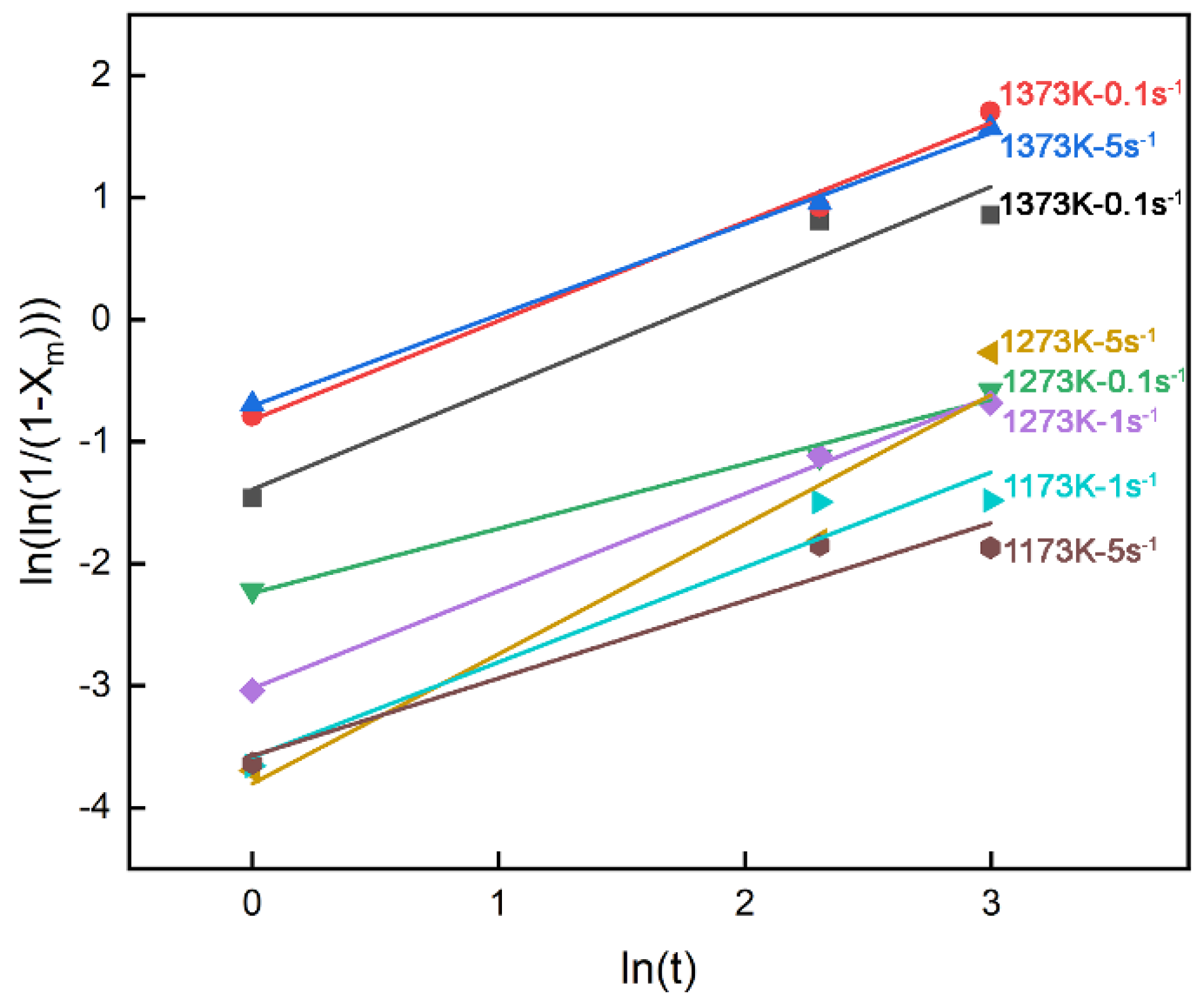

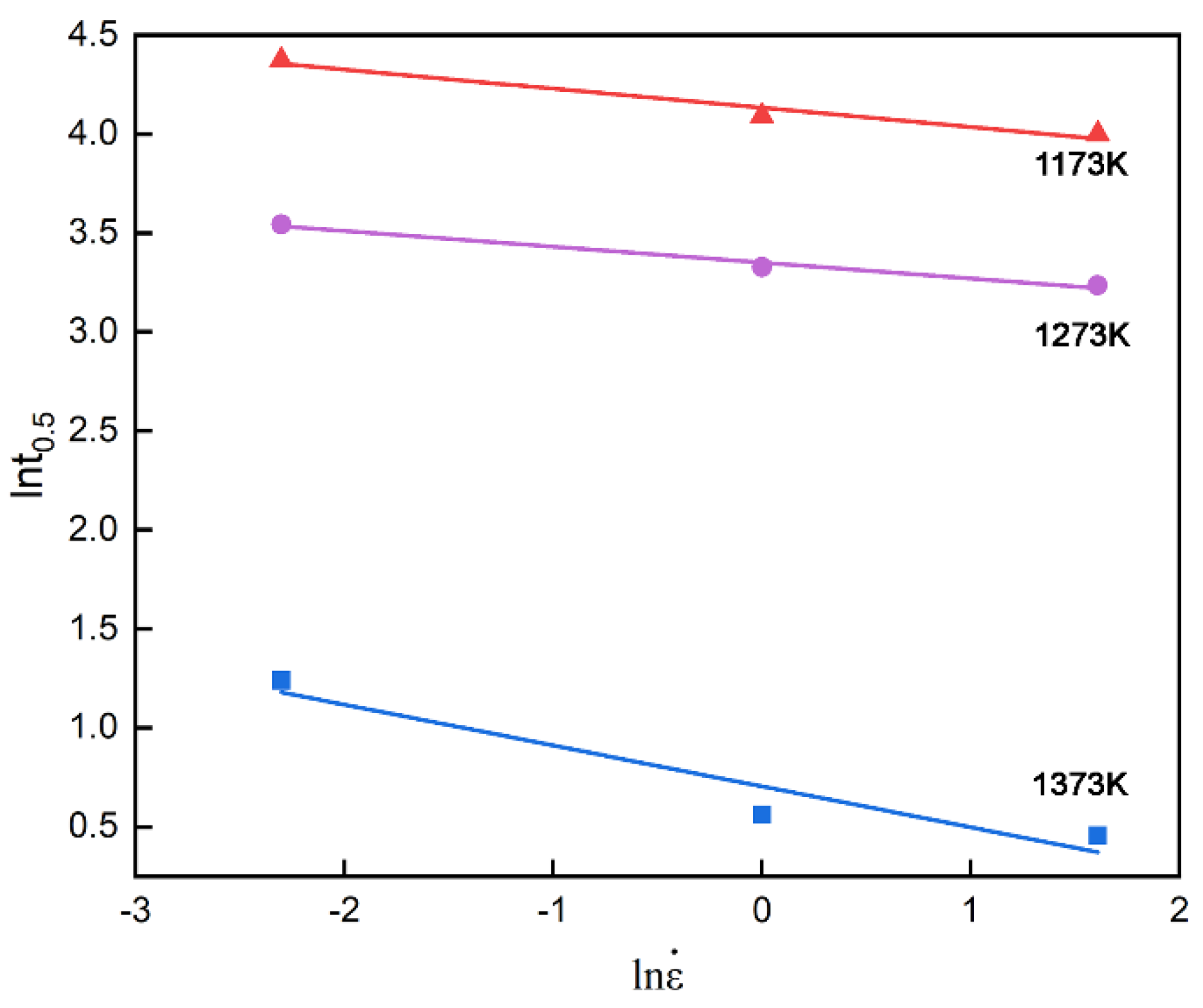

The value of n could be leaner fitted by plotting ln[ln(1/(1-X

m))] versus lnt which descripts in

Figure 4, and n is calculated as an averaged value of 0.77. The value of t

0.5 could be calculated by the leaner fitting from the value of intercept from the experimental aspect according to

Figure 4 at the same time.

Another decisive parameter

could be expressed as:

Where

is the strain rate, Q is the activation energy (J/mol) for metadynamic recrystallization, R is the mole gas constant which is equal to 8.314 J/K·mol, T is the deformation temperatures (K) when recrystallization occurs between passes, A and r are the material dependent constants. The value of A and r could also be obtained by fitting followed by Eq. (5) under natural logarithm:

Figure 5 displays the results and fitting between ln

and lnt

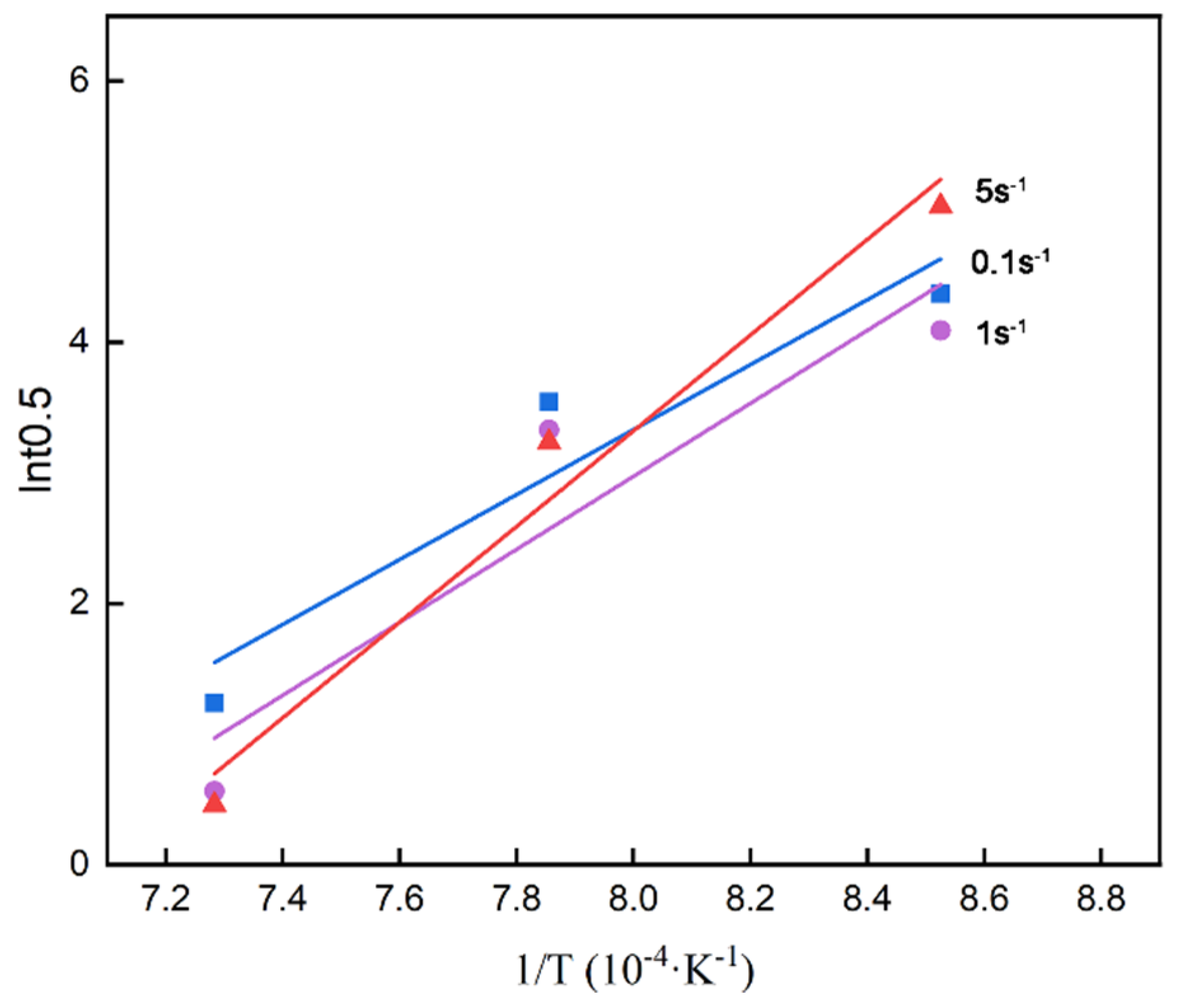

0.5 which is able to identify the value of r equal to the slope as -0.13 on average.

The value of Q can be addressed as 247930 J/mol through the fitting curves of 1/T and lnt

0.5 shown in

Figure 6. Finally, A can be achieved as 1.08 × 10

-9 based on the above calculation.

The kinetic behavior of the metadynamic recrystallization of CP800 steel described by Eq. (3) and Eq. (5) is presented as follows:

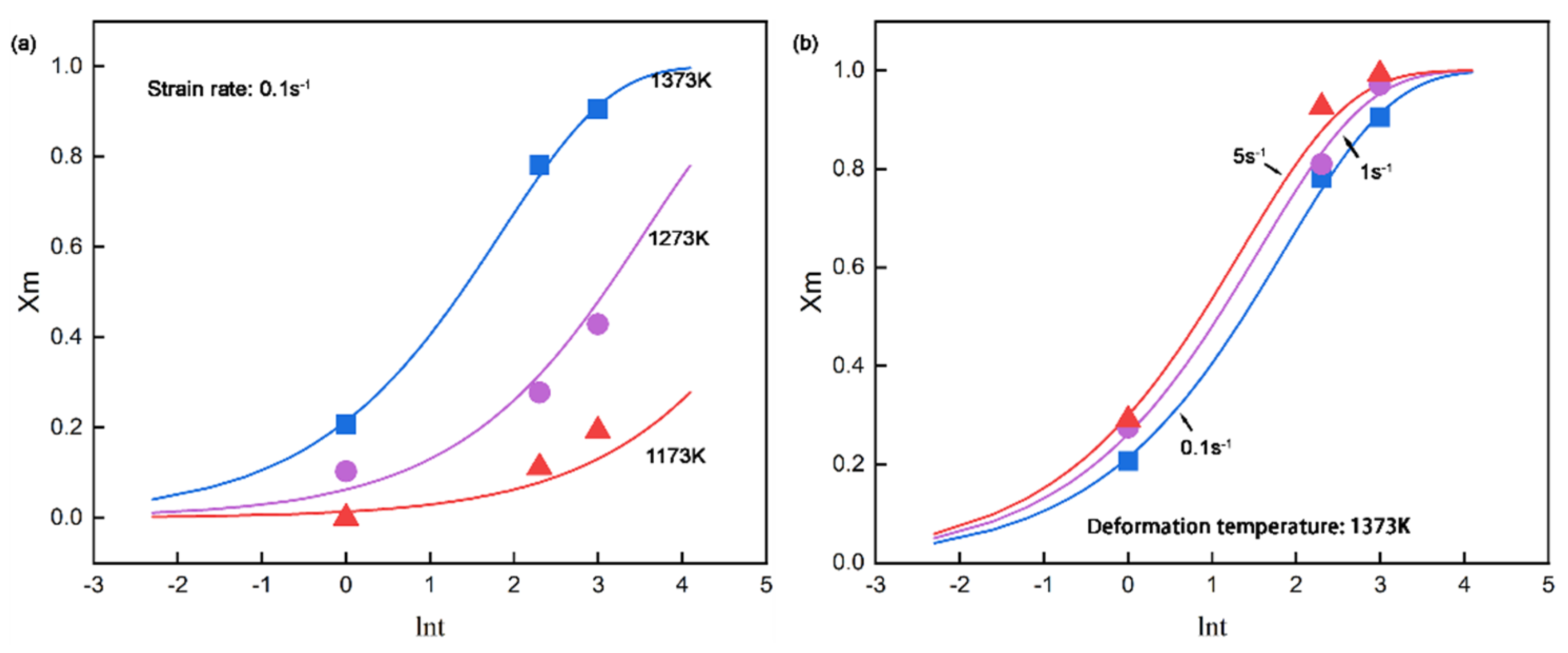

The comparison of experimental results and calculation fitting according to Eq. (7) and Eq. (8) is shown in

Figure 7. It seems that the results match well where the maximum and average biases are 6.2% and 2.3% of the fraction of metadynamic recrystallization. These kinetic equations of CP800 steel are potentially useful for qualitative semi-empirical analysis and for setting a fundamental frame of the rolling process. From the fitting profiles of X

m draw in

Figure 7a, it can be read that the metadynamic softening occurs sufficiently at any strain rates at more than 10 s interpass time at 1373 K deformation. However, it seems the metadynamic softening was hardly carried out at 1173 K under most conditions even given a longer interpass time. It suggests that it would be beneficial to finish the rolling deform at least higher than 1173 K if a mixed grain size is not welcome in the steel design. Hence, the number of rolling passes, roll spacing, rolling speed, etc. need to be carefully considered to meet the suggestions.

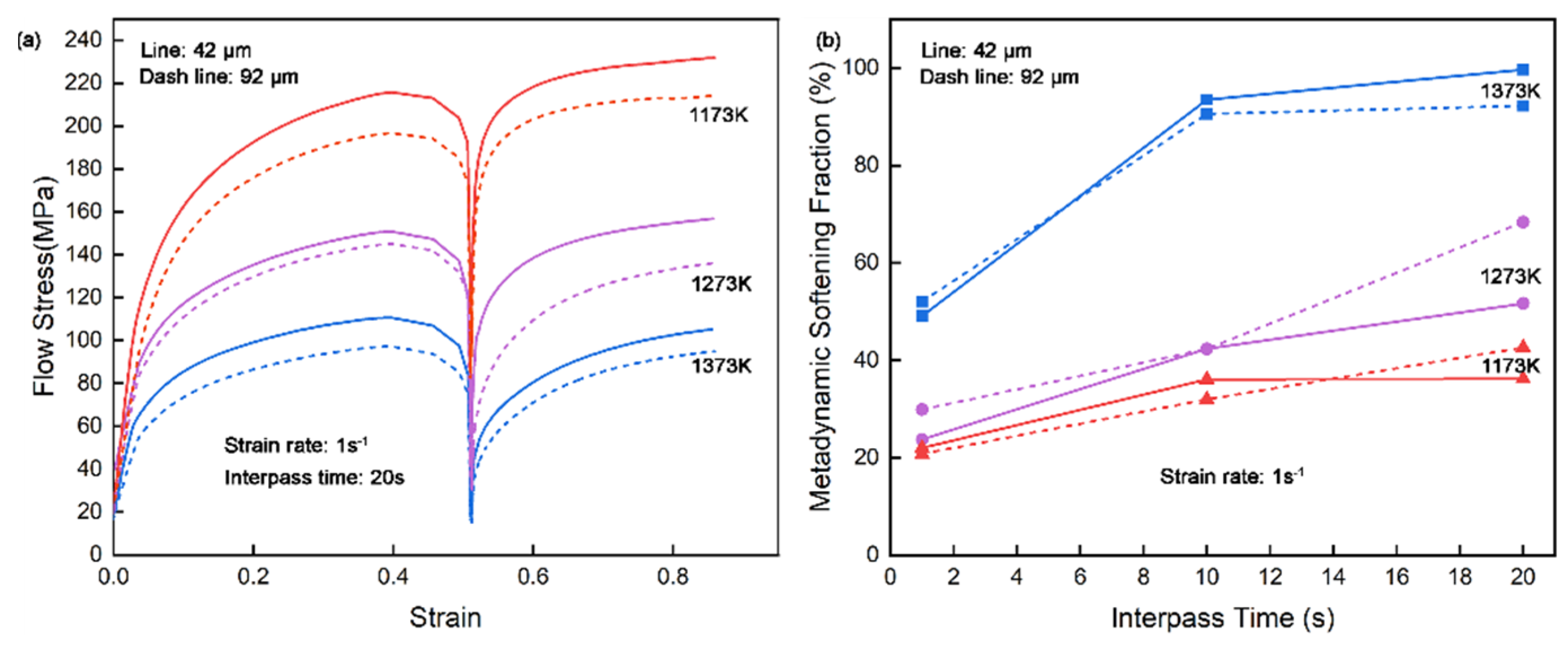

3.4. Initial grain size effect on the metadynamic softening of CP800 steel

In the compact steel production process, the temperature would be different between the head and tail of continuous casting billet before rolling since this compact process generally saves or is insufficient in the holding procedure before rolling, which leads to the differential of the initial austenite grain size before rolling deformation. Hence, two different sizes of initial austenite grains were constructed in this study to identify how initial grain size influences metadynamic recrystallization. 42 μm and 92 μm initial austenite grains were produced by 10 min and 30 min holding at 1200 ℃ before isothermal double compression. The flow stress-strain curves and metadynamic softening fraction at 1 s

-1 strain rate of different initial grain sizes are presented in

Figure 8. From

Figure 8a, the flow stress of 92 μm initial austenite grains samples is lower than the 42 μm samples which is influenced by the fine grain strengthening. The basic behavior such as the effect of deformation temperatures on flow stress, or the relationship between interpass time and metadynamic softening fraction are reasonably consistent with each other no matter which condition.

Figure 8b also draws the picture that there is no worthy change and an interesting pattern, indicating that the metadynamic recrystallization behavior of CP800 steel is independent of the initial grain size. Sun et. al [

36] explained that the nucleation of metadynamic recrystallization that occurred in the first compression didn’t change along with the grain size, which makes the similar softening behavior during interpass.

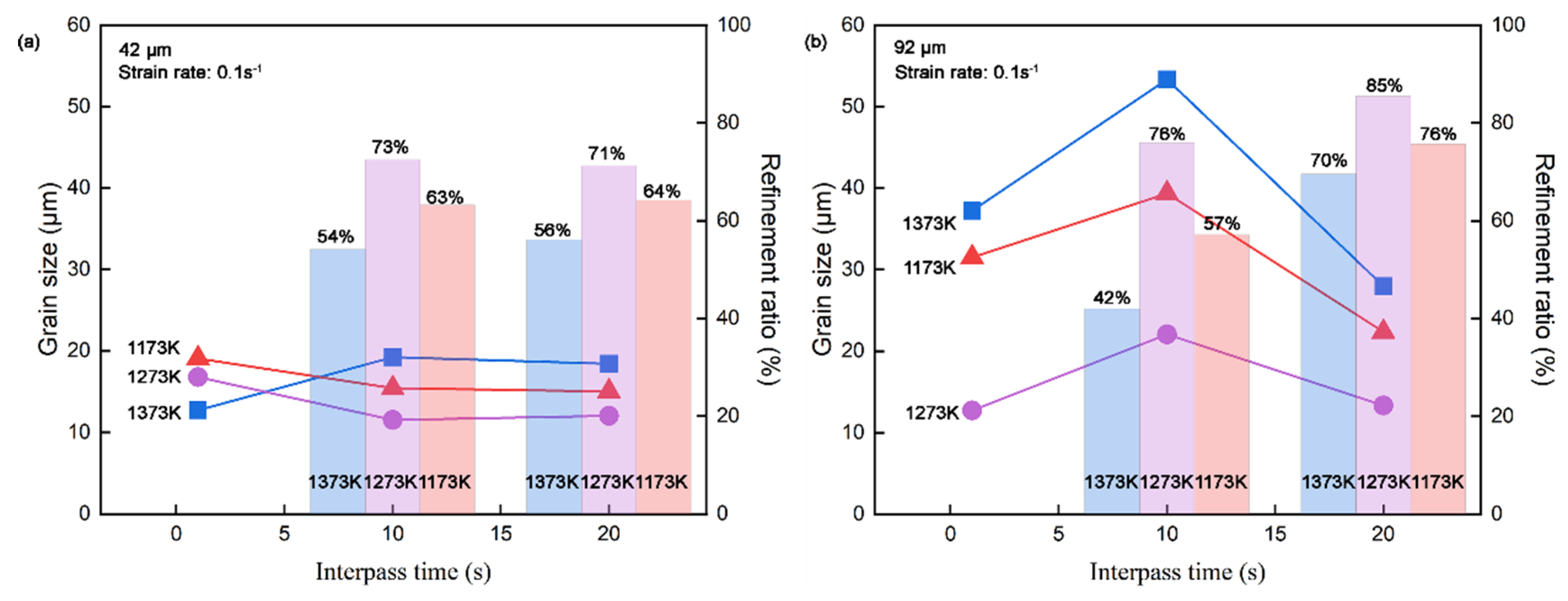

3.5. Grain size after metadynamic softening of CP800 steel

Grain size after 0.1 s

-1 strain rate deformation of 42 μm and 92 μm initial austenite grains steels are performed in

Figure 9. As we can see from

Figure 9a, the 1173 K line shows a typical change of metadynamic recrystallization refining grain size following the different interpass times which indicates the fraction of recrystallization increase by the interpass time, which is consistent with

Figure 3a and

Figure 7a. The trend of the 1273 K line is the same as the 1173 K line in the first part of

Figure 9a while slightly going up after 20 s softening, which means there could be a growth procedure after a recrystallized grain since the longer isothermal time. The trend of the 1373 K line is the same as the 1173 K line in the last part of

Figure 9a while lower after 1 s softening, where many small recrystallized grains formed at the boundaries dedicate the reduction of average grain size value. This phenomenon was also found in 92 μm initial austenite grains samples shown in

Figure 9b, and it is reasonable to regard that it could hardly go through full recrystallization within 1 s interpass time in 92 μm initial austenite grains samples in the condition as we studied, but there are highly portion of grains nucleate in such short time pause which implies 92 μm initial austenite grains steels have a higher recrystallization driven energy compared to the 42 μm samples. The refinement ratio (%) is calculated as

, where D is the average diameter grain size after compression, and D

0 is the initial austenite grain size. Since the average grain size of 1 s interpass is meaningless due to the mixed size of grains, only the refinement ratio bars of 10 s and 20 s are shown in

Figure 9. The samples with 42 μm initial austenite grains are almost refined to a stable size during 10 s interpass time compared to 20 s. For the 92 μm initial austenite grains samples, it seems that the refinement still works until 20 s, and the refinement ratios are higher than 42 μm initial austenite grains samples in all conditions. The most efficient deformation temperature is 1273 K at the strain rate of 0.1 s

-1 (since 1 s

-1 and 5 s

-1 also show the same trend with 0.1 s

-1 which are not shown here) in both initial austenite grain samples which guide the optimization of rolling temperatures during production. If we focus on the final recrystallization grain size in every deformation condition, the 42 μm initial austenite grains samples present a smaller size, which might imply that it is not necessary to hold in the furnace under higher temperatures or longer time for a bigger size before rolling to satisfy the energy-saving and timeless consuming strategy at the same time under the premise of ensuring chemical composition homogeneity. Although the manufacturing production is more complicated than the experimental condition, this study draws an optimization script and is highly trustworthy for the procedure recommendation.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the metadynamic recrystallization behavior of CP800 steel was investigated through the isothermal double compression at deformation temperatures of 1173, 1273, and 1373 K, and at strain rates 0.1, 1, and 5 s−1, under different interpass time of 1, 10, and 20 s. The effect of initial grain size in 42 μm and 92 μm on metadynamic recrystallization was also discussed. The conclusions are in the following:

The metadynamic recrystallization fraction grows higher with the increasing deformation temperature, strain rate, and interpass time. At 1373 K deformation, the metadynamic softening occurs sufficiently at any strain rates at 10 s interpass time. It seems the metadynamic softening was hardly carried out at 1173 K under the studied conditions.

The fraction of the metadynamic recrystallization of CP800 steel is fitted as: , and the time (s) for 50% metadynamic recrystallization predicted as: . The fitting is in good agreement with the experimental results.

The metadynamic recrystallization behavior of CP800 steel is independent of the initial grain size in this study condition. Although the 92 μm initial austenite grains samples have higher efficiency (refinement ratios), the 42 μm initial austenite grains samples present a smaller size on the final recrystallization grain size. The most efficient deformation temperature is 1273 K.

Based on the above discussion, it is suggested that the final pass of rolling should deform at least higher than 1173 K to avoid mixed grains. A lower holding temperature and a shorter holding time before rolling are recommended for compact process and energy saving under the premise of ensuring chemical composition homogeneity and final deformation temperature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.M. and W.M.; methodology, X.Y.; software, X.Y.; validation, X.Y. and W.M.; formal analysis, X.Y.; investigation, X.Y.; resources, Z.M. and W.M.; data curation, X.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, X.Y.; writing—review and editing, W.M.; visualization, X.Y.; supervision, W.M. and Z.M.; project administration, W.M. and Z.M.; funding acquisition, Z.M. and W.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

X.Y. and Z.M. would like to acknowledge the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52274372) for supporting their research. W.M. would like to acknowledge ÅForsk Foundation (23-540), SSF Strategic Mobility Grant (SM22-0039), STINT (IB2022-9228), and the Swedish Steel Producers’ Association (Jernkontoret) for supporting the research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Due to privacy restrictions, we are currently unable to make the data publicly accessible. However, we would like to emphasize that these data can be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author, provided that such requests comply with privacy-related guidelines.

Acknowledgments

X.Y. would like to acknowledge the support from China Scholarship Council for funding the research stay at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Raabe, D.; Jovičević-Klug, M.; Ponge, D.; Gramlich, A.; Kwiatkowski da Silva, A.; Grundy, A. N.; Springer, H.; Souza Filho, I.; Ma, Y. , Circular Steel for Fast Decarbonization: Thermodynamics, Kinetics, and Microstructure Behind Upcycling Scrap into High-Performance Sheet Steel. Annual Review of Materials Research 2024, 54, 247–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S. N. , Processing of Microalloyed Steels by CSP Process. Materials and Manufacturing Processes 2010, 25, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Chen, G.; Chen, D.; Yu, W. An energy intensity optimization model for production system in iron and steel industry. Applied Thermal Engineering 2016, 100, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoen, K. K. Christoph; Krämer, Stephan; Caballero, Luis Acainas;, CSP® – THE FLEXIBLE AND PROFITABLE TECHNOLOGY TO PRODUCE A WIDE RANGE OF STEEL PRODUCTS. 11th International Rolling Conference (IRC 2019), 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reip, C. P.; Hennig, W.; Kempken, J.; Hagmann, R. Development of CSP® Processed High Strength Pipe Steels. Materials Science Forum 2005, 500-501, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilditch, T. B.; de Souza, T.; Hodgson, P. D. 2 - Properties and automotive applications of advanced high-strength steels (AHSS). In Welding and Joining of Advanced High Strength Steels (AHSS), Shome, M.; Tumuluru, M., Eds. Woodhead Publishing: 2015; pp 9-28.

- Ma, G.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Gao, J.; Wu, G.; Mao, X. Study on Corrosion Behavior and Mechanism of Ultrahigh-Strength Hot-Stamping Steel Based on Traditional and Compact Strip-Production Processes. In Materials, 2023; Vol. 16. [CrossRef]

- Reip, C. P.; Shanmugam, S.; Misra, R. D. K. , High strength microalloyed CMn(V–Nb–Ti) and CMn(V–Nb) pipeline steels processed through CSP thin-slab technology: Microstructure, precipitation and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2006, 424, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkenberg, C.; Kintscher, B.; Hoen, K.; Reifferscheid, M. More than 25 Years of Experience in Thin Slab Casting and Rolling Current State of the Art and Future Developments. Steel Res. Int. 2017, 88, 1700272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. P. Microstructure and Property Characteristics of CSP®-Produced Advanced High Strength Steels. Materials Science Forum 2012, 706-709, 2830–2835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venturini, R.; Bianchi, A.; Andraghetti, M.; Guarnaschelli, C.; Cesile, M.; Di Nunzio, P. E. Industry news -Automotive Metallurgical design and production of AHSS grades DP800 and CP800 ISP and ESP thin slab technology at Acciaieria Arvedi in Cremona, Italy. La Metallurgia Italiana 2020, March2020, 43. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; He, G.; Peng, H.; Jiang, B.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Y. Microstructures and Mechanical Properties of Low Carbon Steel Hot Rolled in Ferrite Region Based on CSP Line. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.-s.; Zhu, G.-h.; Mao, W.-m. Comparison of Grain Size in Plain Carbon Hot-Rolled Sheets Manufactured by CSP and Conventional Rolling Processing. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2012, 19, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R. f.; Sun, L. g.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X. l.; Liu, Q. y. Microstructures and Properties of X60 Grade Pipeline Strip Steel in CSP Plant. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2008, 15, 71–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardo, A.; Marraccini, R.; Hua, M.; Garcia, C. Producing High Quality Niobium-Bearing Steels Using the CSP Process at Nucor Steel Berkeley. 2006.

- Romano-Acosta, L. F.; García-Rincon, O.; Pedraza, J. P.; Palmiere, E. J. Influence of thermomechanical processing parameters on critical temperatures to develop an Advanced High-Strength Steel microstructure. JMTSAS 2021, 56, 18710–18721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stumpf, W. Grain size modelling of a low carbon strip steel during hot rolling in a Compact Strip Production (CSP) plant using the Hot Charge Route. Journal of the Southern African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy 2003, 103, 617–631. [Google Scholar]

- Roucoules, C.; Yue, S.; Jonas, J. J. Effect of alloying elements on metadynamic recrystallization in HSLA steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1995, 26, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. W.; De Cooman, B. C. In Studying the Hot Working Characteristics and Dynamic Recrystallization Behavior of Conventional Low Carbon Steel during In-Line Strip Production Process, Proceedings of the 8th Pacific Rim International Congress on Advanced Materials and Processing, Cham, 2016//, 2016; Marquis, F., Ed. Springer International Publishing: Cham, pp 695-702.

- Zhao, Z. Z.; Kang, Y. L.; Mao, X. P.; Chen, Y. L.; Chen, G. J.; Chen, X. W. Study on Recrystallization Behavior of High Strength Automobile Steel Sheets Produced by CSP. Materials Science Forum 2005, 475-479, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, Y. G.; Lin, H.; Li, M. Q. , The metadynamic recrystallization in the two-stage isothermal compression of 300M steel. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2013, 565, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.-b.; Liu, Z.-d.; Dong, H.; Gan, Y.; Kang, Y.-l.; Li, L.-j.; Mao, X.-p. Numerical Simulation of Austenite Recrystallization in CSP Hot Rolled C-Mn Steel Strip. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2007, 14, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembiczak, T.; Knapiński, M. Shaping Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of High-Carbon Bainitic Steel in Hot-Rolling and Long-Term Low-Temperature Annealing. Materials 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozańska-Jędrasik, L.; Mazurkiewicz, J.; Matus, K.; Borek, W. Structure of Fe-Mn-Al-C Steels after Gleeble Simulations and Hot-Rolling. In Materials, 2020; Vol. Materials 2020, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorvaldsen, A. The intercept method—2. Determination of spatial grain size. Acta Mater. 1997, 45, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, F. J.; Hatherly, M., Chapter 6 - Recovery After Deformation. In Recrystallization and Related Annealing Phenomena (Second Edition), Humphreys, F. J.; Hatherly, M., Eds. Elsevier: Oxford, 2004; pp 169-213.

- Lee, S. W.; Park, S. H. Static recrystallization mechanism in cold-rolled magnesium alloy with off-basal texture based on quasi in situ EBSD observations. Journal of Alloys and Compounds 2020, 844, 156185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Zeng, J.; Yao, G.; Feng, F. Flow-Stress Model of 300M Steel for Multi-Pass Compression. Metals 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Khan, S. A.; Yanagimoto, J. , Metadynamic recrystallization behavior of 5083 aluminum alloy under double-pass compression and stress relaxation tests. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2021, 822, 141673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, A. S.; Hodgson, P. D. The post-deformation recrystallization behaviour of 304 stainless steel following high strain rate deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng., A 2011, 529, 164–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, H. L.; Akben, M. G.; Jonas, J. J. , Effect of molybdenum, niobium, and vanadium on static recovery and recrystallization and on solute strengthening in microalloyed steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 1983, 14, 1967–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djaic, R. A. P.; Jonas, J. J. Recrystallization of high carbon steel between intervals of high temperature deformation. Metall. Trans. 1973, 4, 621–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.-f.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, L.-w.; Xia, Y.-n.; Xu, Y.-f.; Shi, X.-h. Metadynamic recrystallization of Nb–V microalloyed steel during hot deformation. Journal of Materials Research 2017, 32, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R. W.; Walley, S. M. High strain rate properties of metals and alloys. International Materials Reviews 2008, 53, 105–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Wang, Q.; El-Awady, J. A.; Raabe, D.; Zaiser, M. Strain rate dependency of dislocation plasticity. Nature Communications 2021, 12, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W. P.; Hawbolt, E. B. , Comparison between Static and Metadynamic Recrystallization-An Application to the Hot Rolling of Steels. ISIJ Int. 1997, 37, 1000–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellars, C.; Davies, G. J.; Metallurgical, S. In Hot working and forming processes : proceedings of an International Conference on Hot Working and Forming Processes, 1980.

- Hodgson, P. D.; Gibbs, R. K. A Mathematical Model to Predict the Mechanical Properties of Hot Rolled C-Mn and Microalloyed Steels. ISIJ Int. 1992, 32, 1329–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutumarao, V. V.; Rajagopalachary, T. Recent developments in modeling the hot working behavior of metallic materials. Bulletin of Materials Science 1996, 19, 677–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).