1. Introduction

According to Dai Jianbing, "money bills refer to the value symbols similar to paper money that can only circulate in a fixed area without the permission of governmental laws and issued by various local authorities, or by some financial, commercial and business institutions or even individuals [0]." In its view, the money ticket is a kind of civil spontaneous organization and design, a kind of "currency" with circulation function, such as directly to the money ticket as the object of study, there will be a transformer field is too large, the research goal is not enough to focus on the problem, there are four reasons: First, the name of the money ticket is not as the same, such as "hanging ticket, ticket stickers, vouchers, private tickets". First, the name of the money ticket is not the same, such as "hanging ticket, ticket stickers, vouchers, private tickets" and so on for the money ticket alias; Second, the circulation range of the money ticket is a "fixed area", as large as the province, as small as the village, and even a few households have their own money ticket, the size of these money tickets, forms, styles, distributors, and the service object are very different, it is extremely difficult to study as a whole [

2]; Thirdly, the time is too long, the earliest money stamps produced in the Northern Song Dynasty, the world's earliest paper money and money stamps "Jiaozi (currency)" produced with the Northern Song Dynasty, assuming that from the beginning of the Northern Song Dynasty to explore, it has to be analyzed from the history of the dynasties, politics, economic policy and other aspects, such as this will create a long and not detailed article [

3]; Fourthly, it is the focus of the study, the money stamps As a historical object, it has more than one kind of research value. If we regard coins as a kind of "currency", we should focus on its economic value, and if we regard it as a "work of art", we should focus on its artistic and cultural value.

Synthesize the four reasons, this paper, in contrast, chose the "late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China" as the time limit, "Jishang (China Hebei Businessman)" as the geographical limit, "artistry" as the focus of the study, aimed at the pursuit of money stamps of the Essence. In terms of research method, the author will first prove its value from comparative analysis, and then, starting from the form, gradually explore the questions of "what are the patterns of Jishang money stamps", "the reasons for using these patterns", and "the sources of Jishang patterns". The origin of the Jishang motifs is then explored step by step.

2. Exploring the Artistic Value of Patterns

2.1. Reasons for Choosing “folk”

Wuhong wrote in his book Ten Discussions on Art History that from the second half of the 19th century, the research and teaching of art history have been increasingly based on the comparison of images, of which the more typical representatives are Wolfring, Nelson, etc. Among them, the method of art research advocated by Wolfring, "art style", is based on the formal comparison between images. Among them, Wolfring advocated the art research method "Artistic Stylistics", which is based on the formal comparison between images and images [

4]. In the stage of analyzing the artistic value, the author will mainly use the method of image comparison to prove the artistic value of Jishang money stamps.

First of all, during the late Qing and early Republican periods, banknotes issued by government-run banks were undoubtedly an important competitor of money stamps, for which, according to Li Gongming, "it is different from the general case study of the artist, as a national design task with the national will, collective discussion and validation by the political hierarchy as the basic features and with the nature of confidentiality, the performance and the role of the artist individually are difficult to be clearly defined. As a national design task characterized by state will, collective discussion and political approval, and of a confidential nature, the performance and role of the individual artist in it is difficult to clearly define [

5]." As explained, official issues were more restrictive than private ones, and designers had to consider both aesthetics and the needs of the government. As a result, the role of designers in official banknotes is difficult to define, and in addition to aesthetics, the study of official banknotes should focus on the political, as well as the historical, aspects of official banknotes.

Secondly, in terms of the object of service, the official banknotes issued by the government serve a wide range of objects, and the content of the pattern is more general and not detailed enough, such as the China Peasant Bank, which was one of the four major banks in the Republic of China, served the four provinces of "Yu, E, Wan and Gan" before its official establishment [

6]. On the other hand, money stamps usually serve a certain fixed area, so the content of the pattern is more focused, which is more valuable for the study of local culture and history.

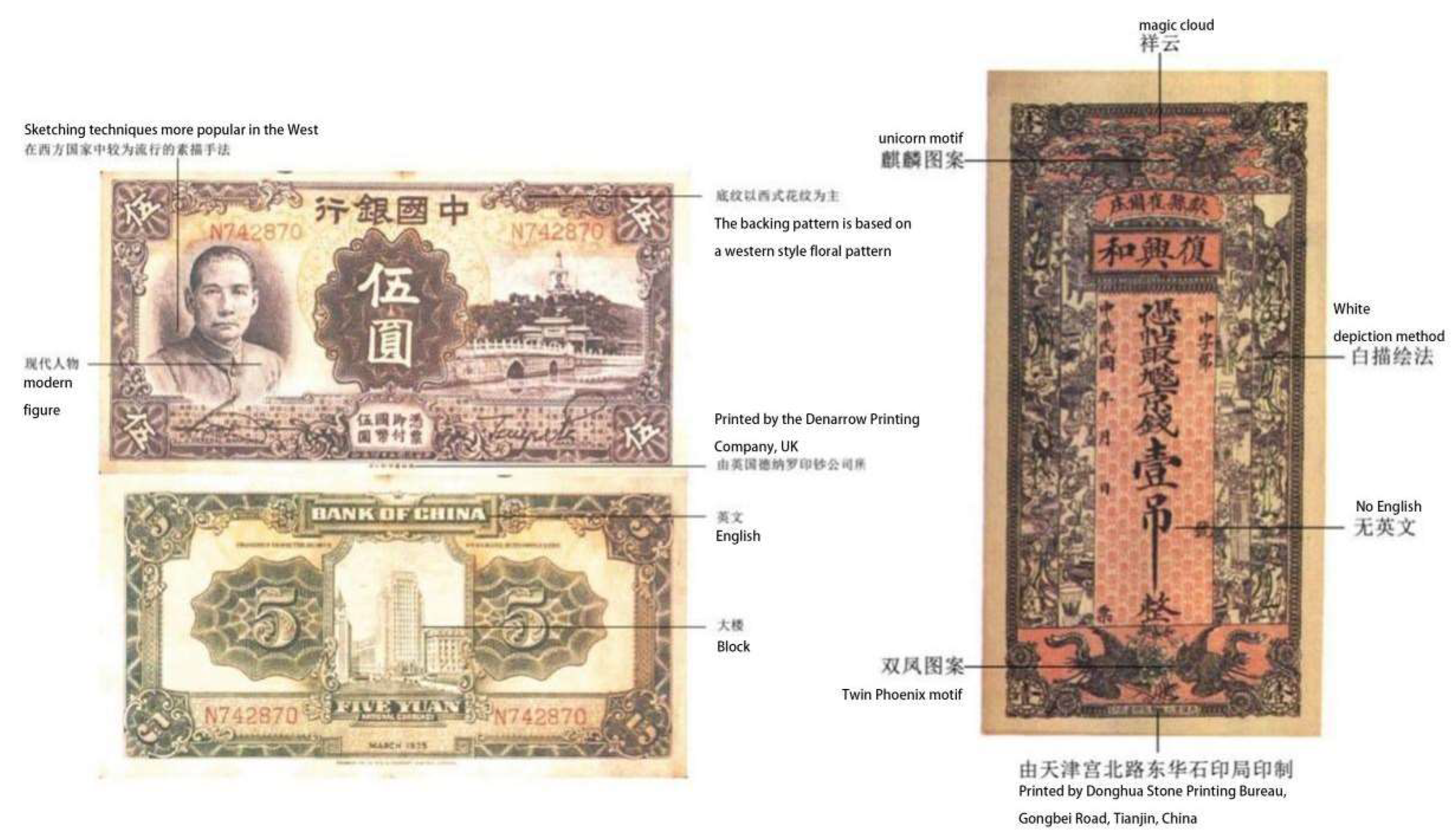

Finally, as far as the issuing organization is concerned, the money stamps are mostly printed by the Stone Printing Bureau of China, while the banknotes issued by the government-run banks are more often printed by foreign companies, for example, the printing company of the banknotes issued by the old Bank of China in the 23rd year of the Republic of China (1934) was the printing company of the British Denarau Printing Company. Comparison of the two forms of banknotes, you can clearly see the differences between Chinese and foreign printing companies, both in style, subject matter and drawing style have a big difference, such as the choice of content and style of drawing, the mother of the money stamps and the method of more from traditional Chinese culture, the use of traditional Chinese painting in the method of the traditional white drawing, the importance of the line of the fluency of the mother of the choice to use the phoenix, The traditional mythological animals such as the phoenix and the unicorn are used as the objects of expression [

7]. The government-run banknotes printed by foreign companies, on the other hand, mostly use the western popular sketching technique, emphasizing the relationship between light and dark, and the subject matter mostly uses high-rise buildings and modern Figures[

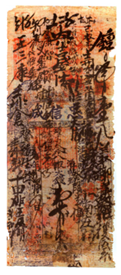

8]. By comparing with the form of banknotes issued by government-run banks, in addition to identifying the difference between the two in terms of form, it can also prove that the pattern of money stamps is more in line with the positioning of China's excellent traditional culture compared to the pattern of government-run banks' banknotes, and it is undoubtedly important to promote excellent traditional culture for the purpose of improving the soft power of culture. (As shown in

Figure 1)

2.2. The Innovative Nature of Jishang Money Stamps

The term Jishang Chanko encompasses three objectives, namely Chanko, Jishang, and Jishang Chanko, the definition of which has been explained in the previous section and will not be repeated here.

Mentioned Jishang, familiar with not many people, on the popularity, less than Hui Shang, Jin Shang, Min Shang, etc., the reason, Bi Zhifu believes that: "There are many reasons, but the most important point is that, in today's administrative units, referred to as Hebei Province, Hebei Province, is active in the Chinese stage time is less than 90 years." As far as he is concerned, the main reason why Jishang is not as well known as other chambers of commerce is that the history is too short. But he also talked about the most brilliant period of Jishang, from the end of the Qing Dynasty to the 20s and 30s of the 20th century, which was the heyday of Jishang's development, and therefore people call this period of Jishang's history "a hundred years of splendor" [

9].

The splendor of the history of Jishang is self-evident, but for its money stamps, the focus is on the artistry, in this regard, relative to other areas of money stamps, the author believes that the special point lies in the innovativeness of the Jishang money stamps, which is the main reason why this paper chooses the Jishang money stamps as the research object.

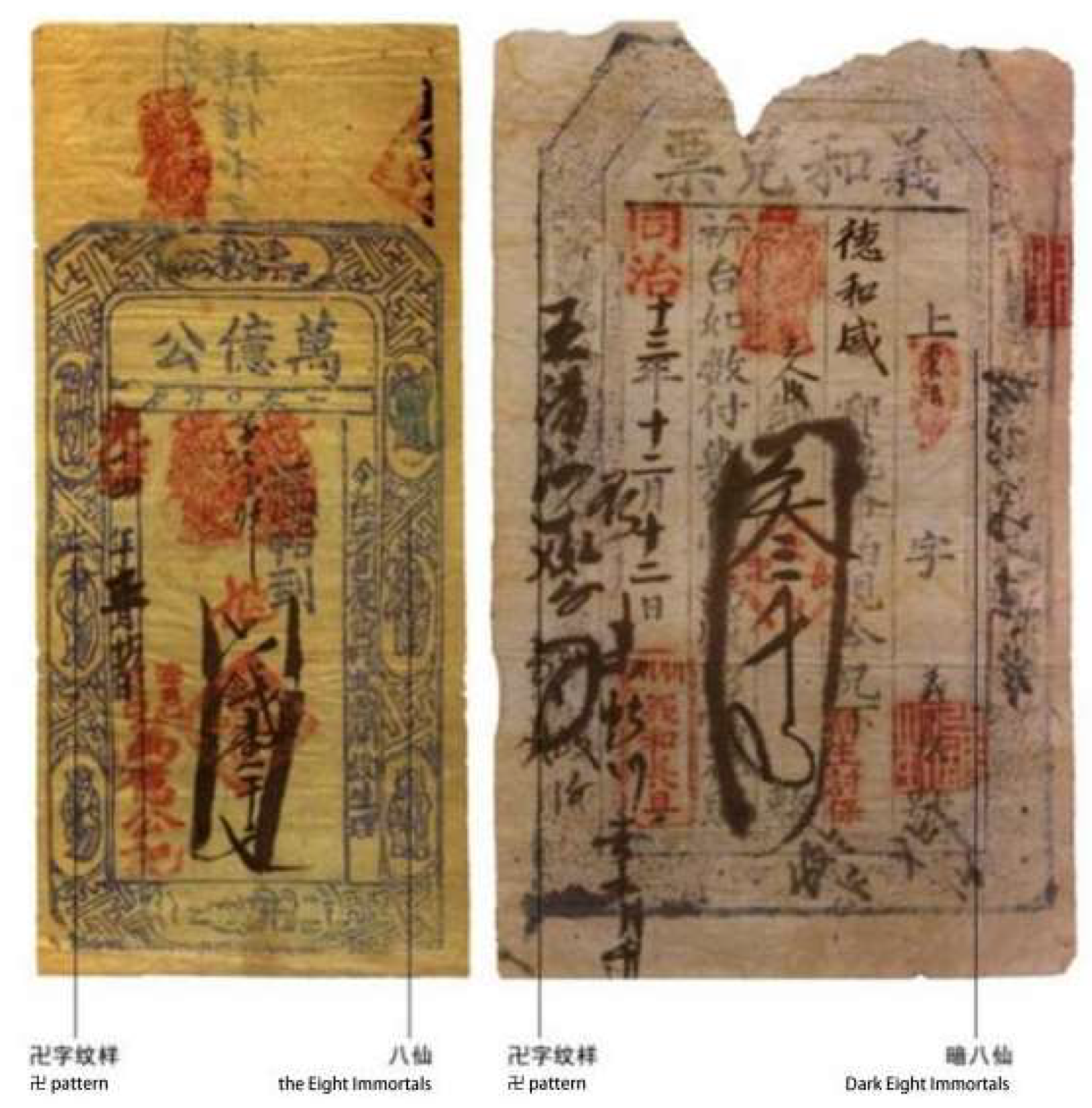

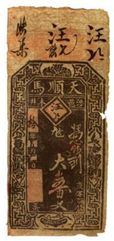

The "Eight Immortals", a popular subject in the late Qing dynasty, is a typical example, and it is not uncommon for Jishang money stamps to use different techniques to express this subject: for example, the money stamps issued by the Tianshunma money bank in Shibuyi, Hebei, in the tenth year of the Guangxu period (1884), used the technique of "base conversion" to express the subject of the "Eight Immortals", i.e., by enhancing the contrast between the design and the base to emphasize the main subject. For example, in 1884, the Tianshunma money bank in Shueyi, Hebei province, used the technique of "base conversion" to express the theme of the "Eight Immortals", i.e., to emphasize the main subject by strengthening the contrast between the design and the base of the picture [

10]; and in the same Shueyi region, the Wanyigong money bank used the "triple-stacking method" to express the theme of the "Eight Immortals", i.e., to enhance the contrast between the design and the base. The "Eight Immortals" is a combination of the "Eight Immortals" and the 卍, with the "Eight Immortals" as the main motif and the "Eight Immortals" as the main motif, and the "Eight Immortals" as the main motif and the "卍" as the main motif. The "Eight Immortals" and the 卍 are combined, with the "Eight Immortals" as the main pattern and the 卍 as the accompaniment, highlighting the "Eight Immortals" at the same time, thus enhancing the level of the picture [

11] (e.g.

Table 1).

Briefly speaking, there are three reasons why this paper chooses the motifs of Jishang money stamps as the main research subject: firstly, it is in line with the needs of the national cultural policy, and in the field of banknotes, Jishang money stamps are more in line with the positioning of traditional Chinese culture; secondly, the artistic value and humanistic connotation of Jishang money stamps are extremely rich, which can be proved by both the variety of subjects, the way of drawing, and the way of combining motifs and motifs with each other; thirdly, it is that, compared to the money stamps of other regions, Jishang money stamps have their unique innovativeness. Thirdly, compared with other regions, Jishang money stamps have their unique innovativeness, even if it is the same subject matter, it can be expressed using different techniques.

As for the research method, as a kind of privately-run currency, Jishang money stamps are not as restricted as the government-run currency, but they are also affected by certain conditions. If this is taken into consideration, the Jishang money stamps cannot be regarded as a simple graphic design work, therefore, this paper will use the comprehensive analysis method of iconography to study them as a whole [

12].

3. Characteristics of Patterns and Their Causes

According to Haskell in his book History and Its Images: images were first pulled to the forefront by historians also because of the study of coins, and it was because Petrarch used the portraits on coins as a basis for his evaluation of the small Gordianus engraver in the Roman Imperial Chronicle that people began to pay attention to the role of coins, and thus analyzing coins from the perspective of motifs has been in use since the Middle Ages The classic method of analyzing coins from the point of view of patterns has been used since the Middle Ages. As a kind of coins, money stamps are determined by the aesthetics of the designers, the economic base and the social background, etc., and it is reasonable to analyze them by using iconography, which is a comprehensive analysis method centering on patterns.[

13]

3.1. Pattern Form Characteristics and Content Analysis

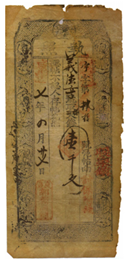

From the point of view of form, money stamp pattern belongs to a kind of graphic design, such as cleverly combining the main picture, decorative patterns and fonts, i.e. layout design; emphasizing the key words through the conversion of fonts, i.e. typography; colorful colors, i.e. color design; and using symmetry, repetition and other techniques to deal with simple geometrical shapes is a kind of graphic composition.

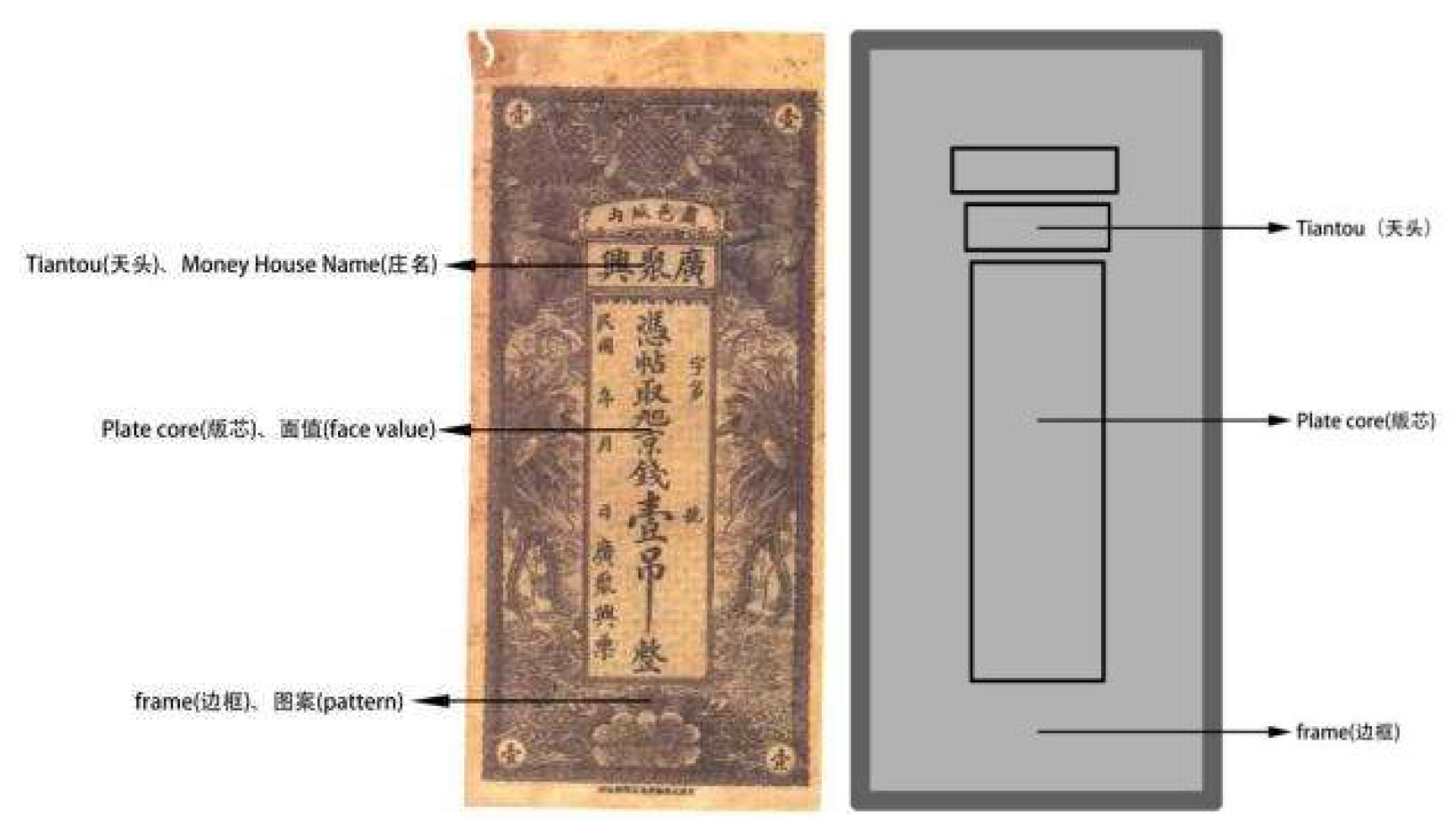

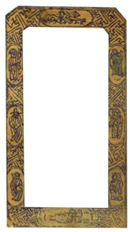

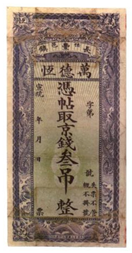

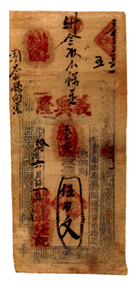

In the plate design, most of the Jishang money stamps in the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China chose vertical composition, the format of the face is relatively uniform, and the whole is roughly composed of three parts, from top to bottom is "the head of the sky", "plate core" and "frame "The overall format is relatively uniform and consists of three parts. The head usually indicates the provenance, such as the name of the merchant or the name of the money changer; the core indicates the amount of the ticket, which is expressed in cents, such as one cent, three cents, etc.; and the borders are mostly decorative or used to add details, and are therefore also known as "picture frames" (shown in

Figure 2).

Color design, Jishang money stamps choose to use a richer color, common gray-green, blue-brown, pink-brown, yellow-red, green-red, black-brown, gray-yellow, etc., of which blue, gray and black are used the most. These colors are lower in purity and brightness and are suitable to exist as accompaniments.

In terms of text design, it is more unified in its choice of language, mostly Chinese, and often uses traditional Chinese fonts such as regular script, seal script, and clerical script. When emphasizing keywords, they are often complemented by complementary or contrasting colors around the characters to set them off, such as white characters complemented by a black background, black characters complemented by a white background, or dark characters complemented by a light background, light characters complemented by a dark background, and so on, and most of this type of keywords are tickets (as shown in

Table 2).

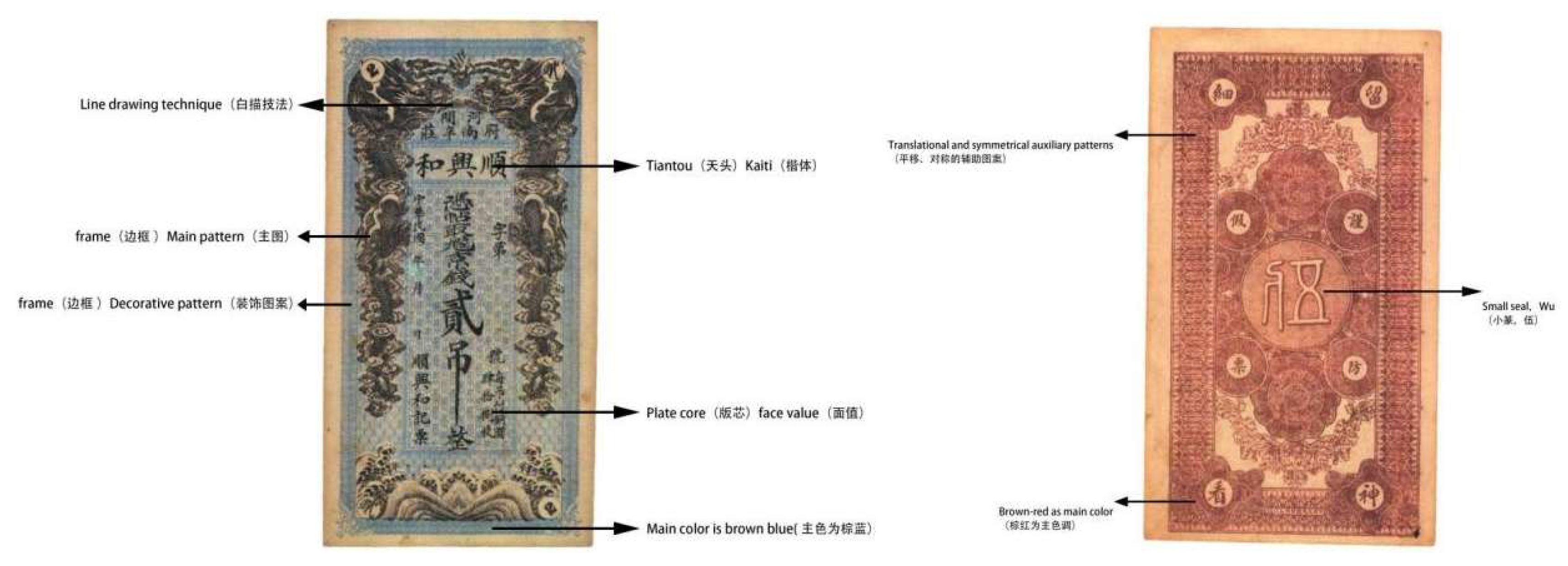

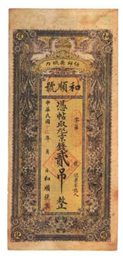

The pattern is mainly divided into two parts, the first part is the main pattern, this kind of pattern usually has the content and expresses the theme, is an important part of the composition of the picture, exists in the format of the "border" area. The second part is the auxiliary background pattern, which serves as a decoration and is arranged in a way of repetition, gradation, bipartite continuity, etc. The number of these patterns is variable, and most of them are located in places other than the main picture. The combination of the two uses a lightening technique, which is intended to give variety to the pattern while emphasizing the "core" part [

14] (as shown in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3).

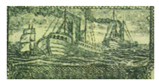

The content, as a whole, can be divided into four parts, the first part is the characters, in the choice of characters are mostly used in traditional stories or Taoist "immortals". The second part is to choose traditional culture or mythological animals as the main object of expression, usually using white drawing techniques to express this theme, the picture has a variety of levels, smooth lines and rich details. The third part is modern tools, of which "train", "ship" and other means of transportation account for the largest proportion. In the fourth section, plants are chosen as the subject matter, with "lotus", "peony" and other flowers as the main ones, and this section adopts the techniques used in Chinese paintings, which are usually used in combination with ancient poems and texts (as shown in

Table 3).

3.2. Pattern Connotation Determines Choice

As mentioned above, the pattern consists of the main picture and decorative motifs, while the connotations of the two are similar, but there are still some differences. In terms of the main picture, the author roughly categorizes the Jishang money stamps into three periods through the differences in subject matter. In the early period, the subject matter of the excellent traditional Chinese culture, folk myths or folk tales, such as myths with the Eight Immortals, folklore with the Dream of the Red Chamber, etc.; the middle period is in the retention of most of the early subject matter on the basis of the addition of a number of new subjects, such as the double-dragon play beads, the unicorn, and so on, this period of time, both in terms of production technology and the fine degree of the pattern have made significant progress; Republic of China period is what the author believes that, the money stamps in the late period, the money stamps. During this period, the subject matter is richer than in the early and middle periods, such as the addition of modern tools not previously available, trains, ships, factories, etc. (as shown in

Table 4).

Although the three periods in the subject matter is very different, but in a careful taste as well as comparison found that they are trying to express a certain auspicious symbolism, the reason why the same purpose creates a different form, there are two reasons: First, as mentioned above, Jishang money stamps innovation, Jishang money stamps in the same subject matter but has a different expression technique, this innovation increases the form of Jishang money stamps between the differences; the second is that due to the Secondly, because there are many motifs containing auspicious symbols, different motifs express different symbols, and the money changers chose the motifs that suited them through their business philosophy.

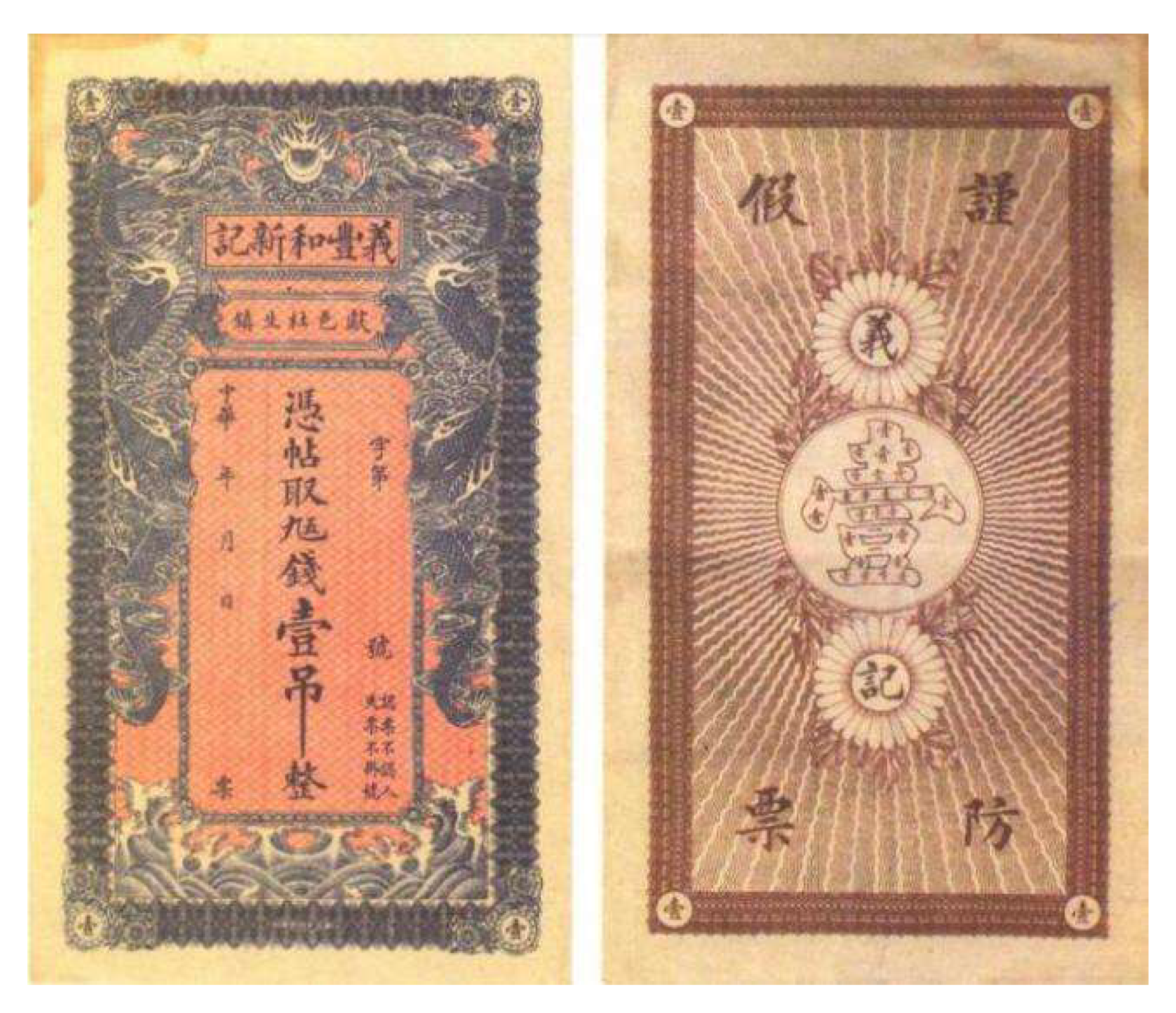

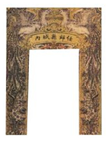

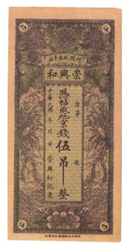

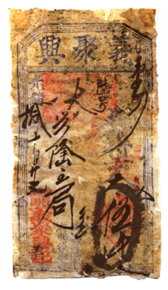

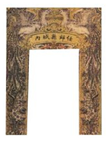

The Yifeng and Xinji money changers in Xian County, Cangzhou, Hebei Province, published a money ticket in the Republic of China period, and chose "Two Dragons Playing with Pearls" as the main theme of expression, supplemented by the water pattern and auspicious clouds, which together constitute the main picture of the ticket surface (shown in

Figure 4).

The reason why merchants choose this content: the dragon in the traditional Chinese pattern, is a long history, the perfect shape of the art image, but also a symbol of good luck, is often considered to be “the crown of the traditional Chinese pattern”. This image first arose in the primitive clan society, in this period, due to the productivity and technology is not developed enough, people for the harsh environment at a loss, so, can only put their hope in the faith, which is the so-called totem of the source, the source of belief in a wide range of things can be anything in nature, such as animals, the sun and so on can be used as this object. Li Zehou explained the reason for the creation of this image in his book “Analysis of Beauty”, and he believed that the ultimate formation of the image of the dragon may have originated from the tribe that used the “snake” or an animal similar to the “dragon” as a totem, and that this tribe eventually overcame the other tribes in their region and took these animals as their totems. After this tribe eventually overcame the other tribes in its region, it fused the essence of the totem images of these tribes into its own totem, which eventually formed the “dragon”, and thus this totem has the symbol of blessing victory and peace[

15]. Extended to modern times, the dragon not only symbolizes power and dignity, but also reflects people's faith and reverence for the natural gods. And the water pattern because often with dragons, fish and other auspicious objects appear in the same picture, so there will be the meaning of auspicious; as for the auspicious cloud pattern, the earliest people will be dark clouds as evil clouds, colorful clouds as auspicious clouds, such as auspicious cloud pattern in the more famous green clouds, this cloud often appear in the clear skies of the weather, so there will be a “flat step” the meaning of rising step by step[

16].

In addition to the main picture, the border decorative pattern is also one of the components of the ticket, if the main picture is to set off the core text of the “background”, the decorative pattern is more like the whole ticket “frame”, not only can make the ticket surface neat, but also the main picture, text and other content Intermingled together. Simply put, the function of the border decorative pattern is to give the picture and text a certain degree of regularity.

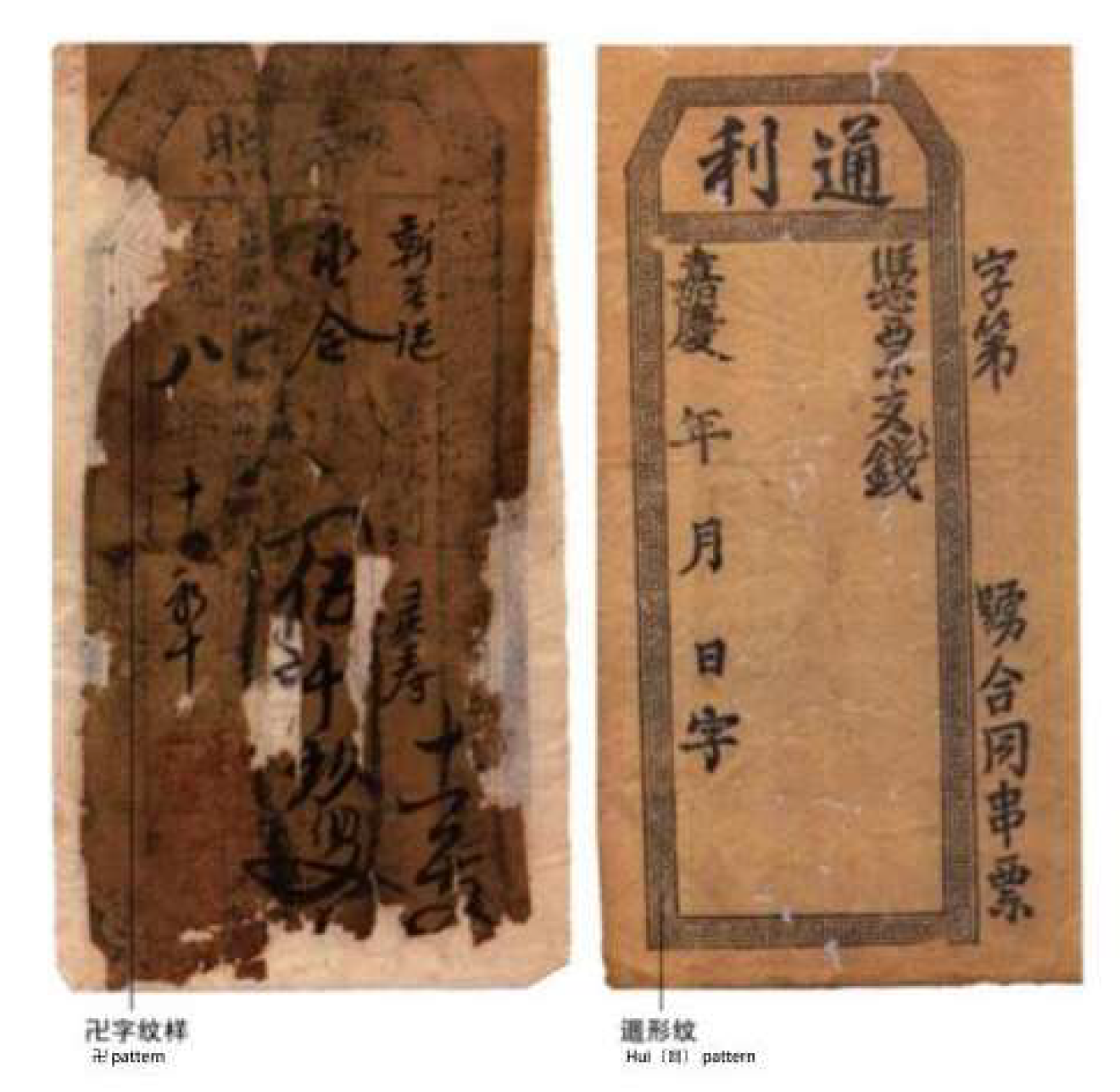

Decorative motifs have existed for a very long time in Jishang money stamps, even before the main picture. As early as the Daoguang period, the Tian Shenghe money bank in Xingtang, Shijiazhuang, Hebei Province, began to use the swastika for decoration (as shown in

Figure 5).

The intention of such decorative motifs is more subtle than the main image. In the case of the 卍, for example, Chen Zhifo has published an explanation of the 卍 in his book Table Number Motifs, in which he argues that: "In China, the use of the 卍 signifies infinity. "In China, the use of the 卍 signifies the meaning of infinity" [

17]. According to his interpretation, the merchants who use the 卍 are hoping for endless business. In addition, Ban Kun in his book "Chinese Traditional Patterns" has said: "The 卍 is Sanskrit, in ancient India, Persia, Greece and other countries is considered to be a symbol of the sun and fire, with a religious nature, Brahminism, Buddhism and other sects are used, "卍" translated that is, the sun and fire. The word "卍" is translated as "the collection of good fortune", and legend has it that this word appeared on Sakyamuni's chest, so it is also known as the symbol of "all virtues and good fortune" [

18]. Although their interpretations are different, their cores are similar, with meanings such as development, happiness and good fortune.

"The 卍 is more popular in the early stage of the development of Jishang money stamps, the arrangement is also a variety of different ways, each different arrangement has its own unique meaning, the more common two-square continuous or four-square continuous arrangement, the meaning is that the character of ten thousand running water; there are some with the "Eight Immortals" and other motifs alternating (shown in

Figure 6). "and other motifs appear alternately, the meaning of ten thousand lives and ten thousand blessings (as shown in

Figure 6). "In the early days, the 卍 occupied a place in the field of decorative motifs by virtue of its simplicity and aesthetics, but with the advancement of technology, merchants began to pursue more complex motifs, and the use of the 卍 in the design of money stamps has been decreasing year by year.

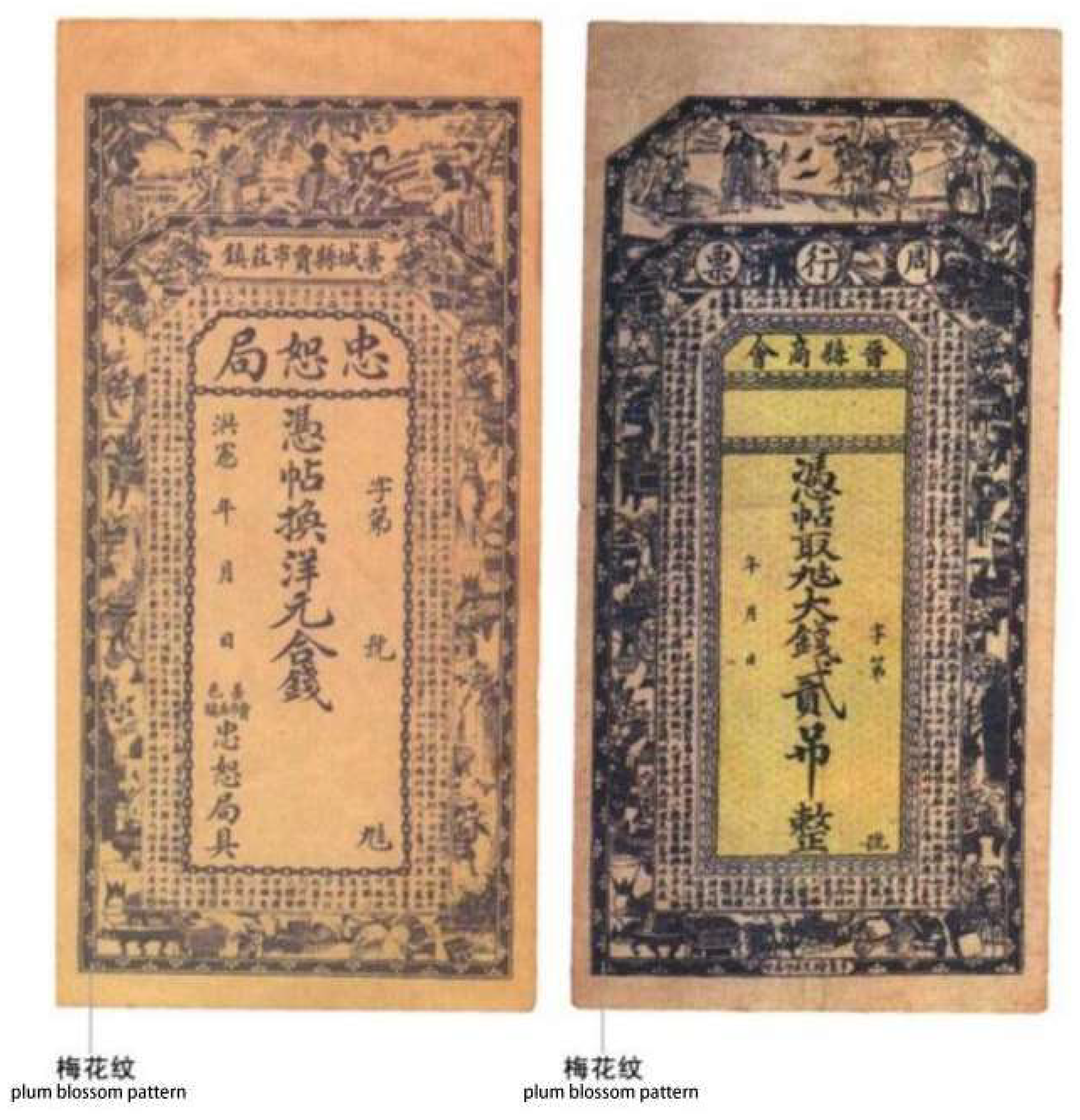

In the late period of money stamps, that is, the Republic of China period, some money changers focused their vision on the botanical pattern represented by the plum blossom pattern, which has been given many symbols, such as the five petals symbolizing happiness, joy, smoothness, longevity, and peace; denoting the five blessings: good fortune, fortune, longevity, joy, and wealth; and a bunch of stamens meaning integrity, unselfishness, perseverance, and heroism, etc. These botanical motifs not only add artistic beauty to the face of the ticket, but also contain strong religious and cultural symbolism.[

19] (as shown in

Figure 7).

Through the analysis of “two dragons playing with pearls”, “swastika” and plant motifs, it can be found that the design of Jishang money stamps is not purely decorative, but is a reflection of the influence of traditional culture and religious beliefs. Whether it is the image of the dragon, the religious symbol of the swastika, or the auspicious symbols in the plant motifs, these motifs together constitute the unique artistic and cultural value of the Jishang money stamps, which show the profound influence of traditional beliefs on commercial practices. At the same time, the deeper connotations of these faith motifs are also, in the author's opinion, the determining factors for the selection of the money stamp motifs.

3.3. Differences in the Form of Impacts of Technological Advances

Why are the forms so different, even though the intent, ideas, etc. are more similar? According to Mike Luhan, "Paper money is based on printing technology". Lu Han that: "paper money is built on the basis of printing technology", printing technology is one of the factors that can not be ignored, money as a kind of paper money, naturally, also has the characteristics of the influence of printing technology, and for money, stone printing is undoubtedly one of the more important technology.

According to Su Jing, the first person to engage in Chinese lithography was Morrison, a missionary from England, who returned to England in 1823 and came into contact with lithography and published the earliest Chinese lithography book in England, Miscellany of China. He then returned to China in September 1826 and brought back the lithographic press he had purchased, and two months later in Macao, he tried lithography for the first time in China, printing the first landscape painting. In Mr. So's opinion, November 1826 is the date of the first stone printing in China [

20]. Subsequently, in 1876, the Englishman E. Meicha, who founded the Declaration Hall, opened the Point Stone Zhai Stone Printing Bureau in Shanghai, and began to print books and periodicals in stone, publishing the Kaocheng Zihui, the Kangxi Dictionary, the Peiwen Rhymefu, the Point Stone Zhai Picture Newspaper, and the Flying Shadow Pavilion Picture Newspaper, etc. Since then, the major lithography centers have appeared one after the other [

21].

Based on the evidence of the scholars mentioned in the previous article and the information that the author has, it can be roughly inferred that the stone printing technology is popular in the printing of money stamps in the middle and late Guangxu period (around 1890), this period is a more chaotic period in modern China, the demand for money stamps is increasing day by day, and then it will be used for the production of money stamps by the stone printing technology, which is a relatively inexpensive and simple printing method [

22]. At the same time, in this period, the quality of money stamps pattern compared to the previous has been extremely obvious improvement, such as the Xianfeng years by the Hebei Guangchang Guo Ao wine store issued money stamps compared to the Guangxu years by the Hebei Qizhou Yuchang Haoji issued money stamps, there is a pattern of fine degree of insufficient, color contrast comparison of the weaker and so on the defects, which can not only illustrate that this period of the progress of the printing technology, but also can be confirmed that technology is an important factor affecting the form of the pattern of money stamps (as shown in

Table 5). Important factors (as shown in

Table 5).

Simply put, this section aims to solve the problem of "why", that is, why Jishang chose these patterns as the main picture of the face of the money stamps, through the analysis of the connotation of the patterns to determine that the money changers are in their respective pursuit of "auspicious symbolism" and the choice of patterns, which also determines the basic content of the patterns, but if this is the explanation for the change in form is still in doubt. This also determines the basic content of the pattern, but if this is the explanation, the form of change is still doubtful. Therefore, in further analysis, this paper compares the patterns of early and late stamps, supplemented by knowledge of the history of printing as a reference, and finally analyzes that the changes in the patterns of stamps were influenced by technological progress.

4. Methodologies

This paper mainly adopts iconographic analysis, historical literature research, comparative analysis of artistic styles and historiographic research methods to conduct a multi-dimensional study of Jishang money stamp patterns. Through iconographic analysis, it explores the formal characteristics and compositional aesthetics of the money stamp motifs, and reveals the uniqueness and artistic expression of their visual design. Combining historical documents and historiographical research methods, we sort out the historical background and evolution of the Jishang money stamp design, and deeply analyze its function and cultural significance in the economy and society at that time. In addition, the comparative analysis of art styles is applied to explore the similarities and differences and stylistic integration of money stamp designs with other visual designs of the same period.

At the same time, this paper focuses on the exchange and integration of Ji merchants' money stamps with other designs, showing how they were influenced by the design elements of different regions and industries in cross-regional cultural interactions. This cross-regional design borrowing not only enriches the aesthetic expression of money stamps, but also promotes cultural exchanges and intercommunication in the commercial and trade activities at that time, which highlights the dual identity and historical value of money stamps as an economic tool and a cultural carrier.

5. Communication and Integration of Design

5.1. Books Influence the Content of Money Stamps

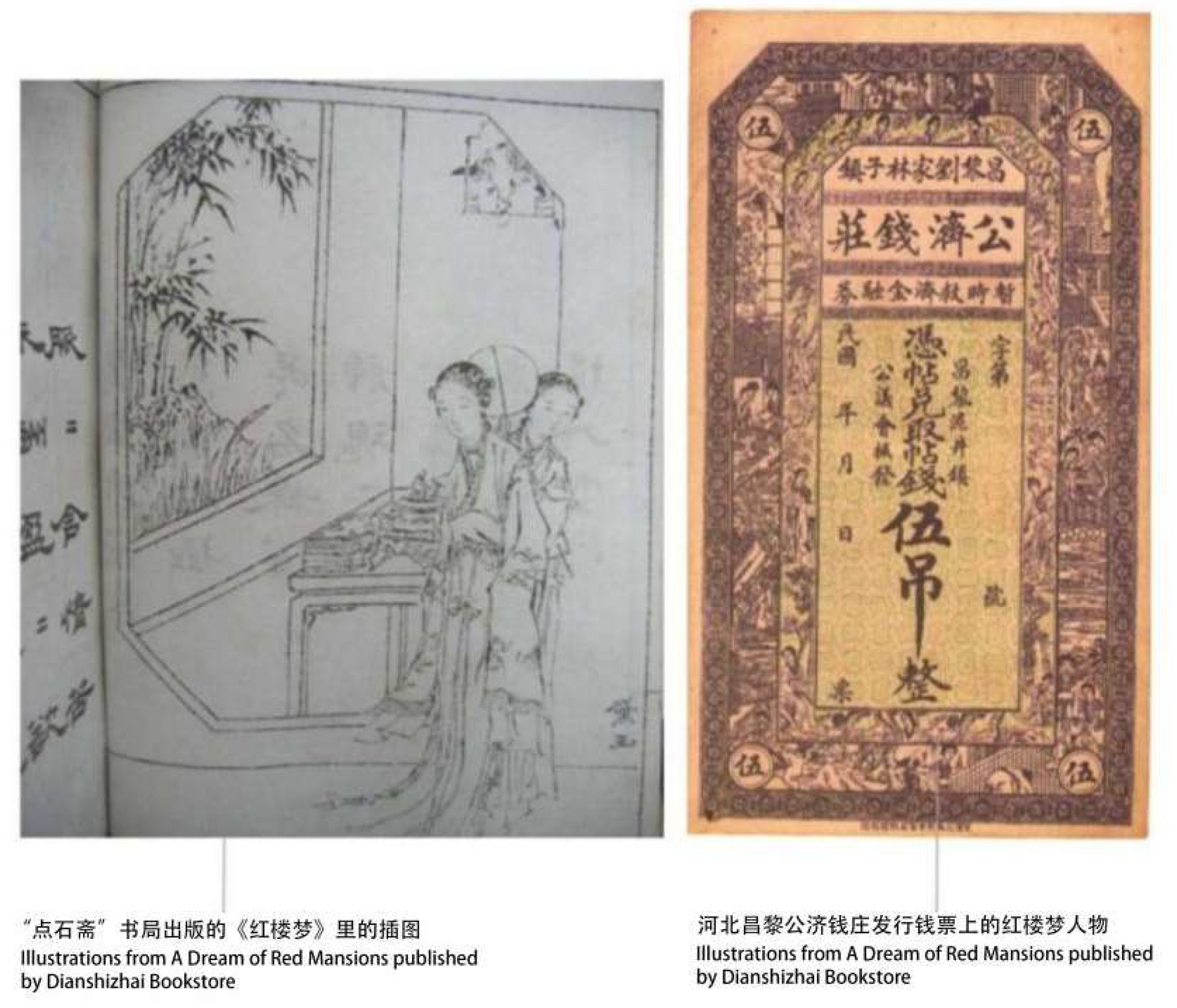

In the early 1980s, the British Museum acquired a group of about 60 Republican-era money stamps, only a few of which are listed in books on Qing dynasty banknotes, and even then, most of the descriptions are rather sketchy. Eight of the stamps can be regarded as part of the same group, as they all bear the watermark of an artist named Wu Songqing. Three of these eight are from the "Dishizhai" bookstore, and one was printed by the "Shenchang Bookstore", which was closely associated with "Dishizhai" [

23]. With Shanghai "point stone Zhai" bureau closely related to the designer of money stamps in addition to Wu Songqing, according to Mr. Fu for the Qun test, there is a name "talk Meiqing" of the painter and calligrapher, although it can not be determined that the "talk Meiqing" Mr. Wu Songqing for who he is. Although it is not possible to determine the "talk about Mr. Meiqing", but can show that the late Qing and early Republic of China, part of the money stamp printing, design, and book printing design is from the same institution [

24].

Zhang or Ding has also conducted a series of examinations on the designers and institutions of the stamps, among which he is most certain that the design of the Liaoning "Donghetai" stamps was taken charge of by a calligrapher and painter named Tan Meiqing in the fall of 1899, for the reason that at the end of the obverse of the stamp is printed "Autumn of jihei, Tan Meijing Aeroshu, Shanghai Hanmo Lin stone seal", which visually indicates the time of printing, the designer and the production unit of this stamp. Shanghai Hanmo Lin Stone Seal", this line visually explains the printing time, designer and production unit of this coin [

25].

Through the above scholars' testimonies, it can be inferred that the design of the money stamps and books may be the same group of people, and the printing may be the same group of organizations. In addition, the contents of books and money stamps are also more consistent, such as the theme of "Romance of the Three Kingdoms", "Dream of the Red Chamber", etc. are often found in money stamps and books [

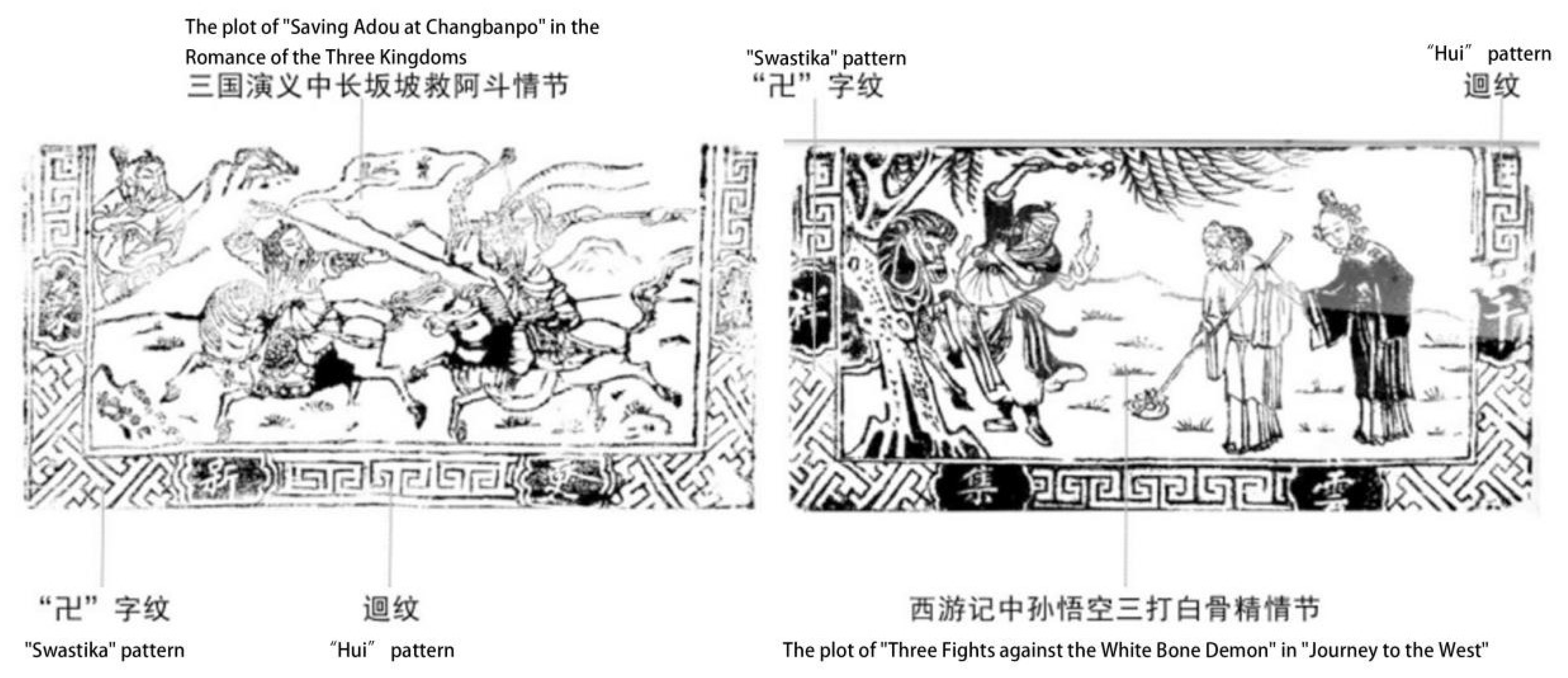

26] (as shown in

Figure 8).

Assuming that the two are really related, but why is the theme used repeatedly? In the author's view, although the money stamp is a special "currency", usually to perform its role as a measure of value, but it still belongs to a kind of graphic design, similar to posters, with the dissemination of money stamps printed on the books related to the pattern of the books, books, is not bad for a means of publicity.

5.2. Influence of New Year's Paintings on Money Stamps

In addition to books, money stamps and New Year's paintings are also related to each other in terms of form, with some commonality in the choice of decorative motifs, the arrangement of techniques, the background of the stories, and the painting techniques. In the use of decorative patterns, both New Year's paintings and money stamps love to use the 卍 and back pattern and use the two-square continuous arrangement method; in the selection of story subjects also love to use the Eight Immortals, the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Journey to the West and other subjects; drawing techniques are good at using the ink line outlining and the technique of white drawing, the characters are clear, the lines are clear, the level is rich and the picture is clean, neat and tidy. The drawing techniques are good at outlining characters with clear lines, rich layers, and clean images [0] (as shown in

Figure 9 and

Table 6).

5.3. The Connection Between Money Stamps and European Decorative Styles

Winnie. Hyde argues that after the 19th century, the term Baroque was used to summarize 17th century European art [

28]. Therefore, it makes sense chronologically that the Baroque style predates the popularity of money stamps.

Historically, modern China has witnessed a wave of learning from the West, a cultural exchange that not only reflected the introduction of technology, but also the fusion of religious beliefs and artistic styles. At that time, many Western missionaries regarded China as the “pure land” of religion, and through missionary activities, they not only spread Christianity, but also introduced Western technology and art styles. For example, the missionary Morrison introduced lithography to China, which not only revolutionized the production of books, but also had a profound impact on the production of money stamps. In this process, the integration of religious beliefs as a medium of cultural dissemination and artistic styles further promoted the diversification of money stamp designs.

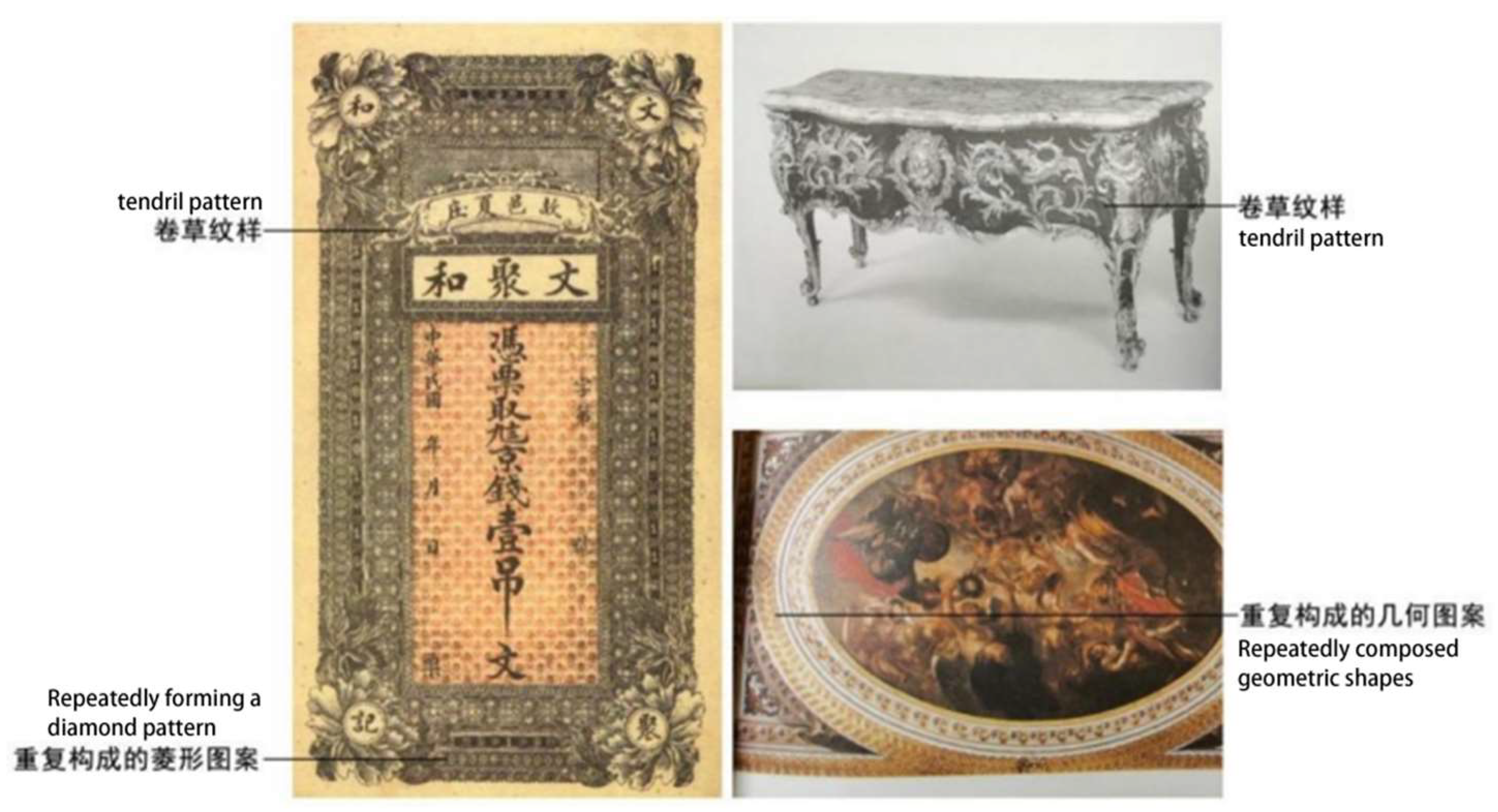

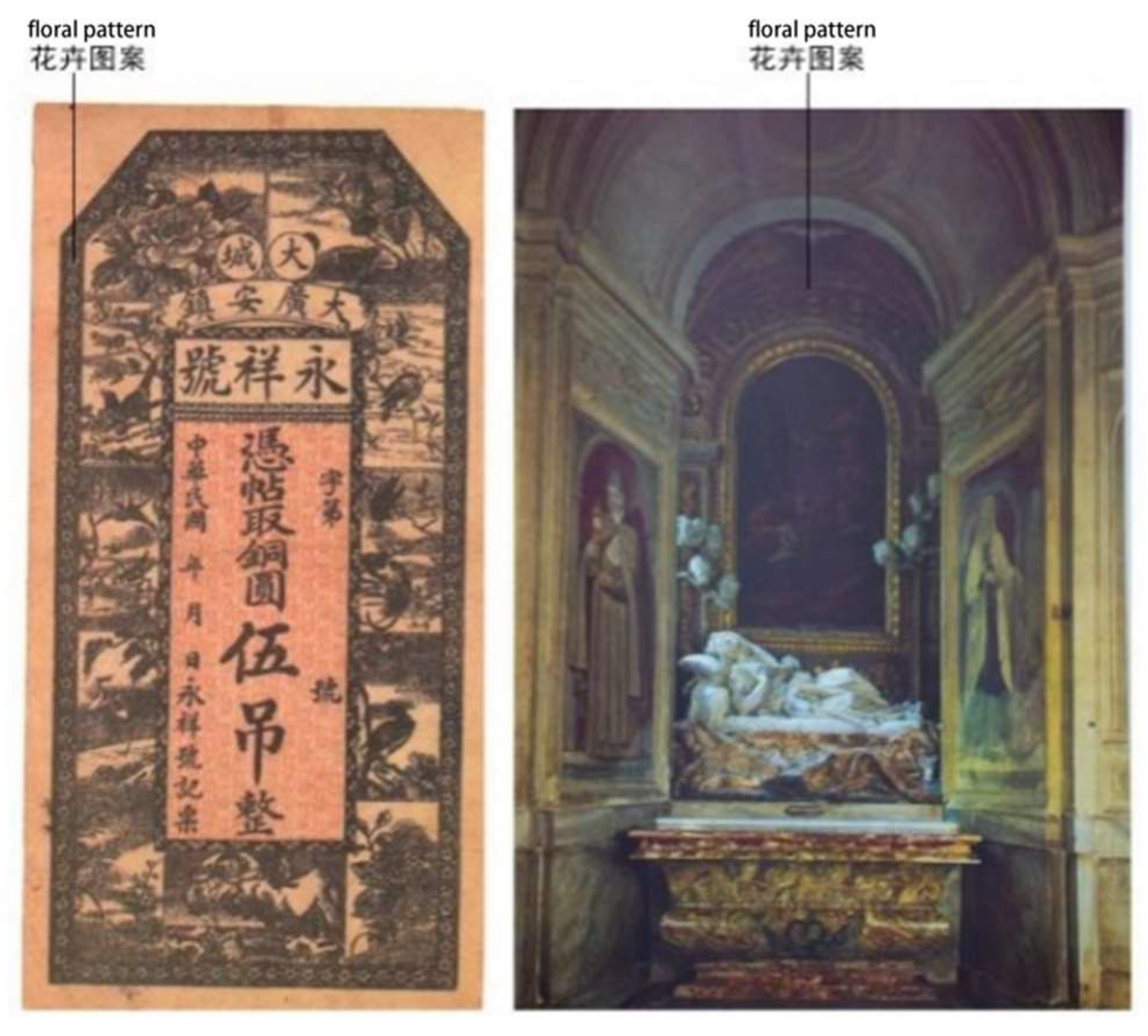

From a formal point of view, some of the decorative patterns in the Jishang money stamps bear some similarity to the Baroque art style. For example, the money stamps issued by Hebei Changli Gongji Qianzhuang during the Republic of China period show some similarities in the presentation techniques and decorative styles between the composition of the patterns and the “Five-double-drawer Cabinet” designed by Nicolas Pinault in 1730. The common baroque style of scrolling, complex symmetrical compositions, and dynamic decorative details are all reflected in some of the designs of the money stamps. This formal similarity may be a direct reflection of the absorption of Western decorative styles into Chinese coin designs, but it also indirectly demonstrates the subtle influence of missionary cultural dissemination on artistic design. (as shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11)

In short, the popularity of decorative styles represented by Baroque and Rococo in Europe preceded the popularity of Chinese money stamp design, which is logically reasonable from the point of view of time; secondly, China began to learn from the West after 1840, coupled with the large influx of missionaries, which not only brought advanced technology, but also religious beliefs and artistic concepts, which created the conditions for the assimilation of Western artistic styles into the design of money stamps. Through the comparative study of the decorative patterns of money stamps and Western art forms, we can further see how Chinese art has realized the fusion of traditional culture and foreign styles under the specific historical background.

6. Results

This paper centers on the causes of the Jishang money stamps' patterns and reveals the multiple factors of their design through comparison, analysis and theoretical explanation. First of all, through comparative analysis with other currencies of the same period, this paper finds the uniqueness of Jishang money stamps in terms of technique, content and function. The study shows that Jishang money stamps are far superior to other currency types in terms of aesthetic value, especially in terms of the composition of the pattern, the treatment of the lines, and the use of colors, which show a more complex and delicate design. These unique design features make Jishang money stamps have unique artistic value among currencies.

Secondly, this paper further interprets the design logic of Jishang money stamp patterns through the use of graphic design theory. The study shows that the composition, proportion and color design of the money stamps not only follow the laws of aesthetics, but are also closely integrated with the market demand and trade culture at that time. These design factors not only enhance the aesthetic appeal of the money stamps, but also help merchants convey commercial credibility and cultural value through visual elements, illustrating the important role of money stamp patterns in attracting the public and shaping the commercial image.

In addition, this paper reveals the cultural roots of Ji merchants' money stamp patterns by comparing them with decorative motifs in traditional Chinese art. It is found that the cultural elements drawn from the money stamp motifs not only stem from traditional aesthetic considerations, but also reflect the merchants' pursuit of symbolism such as auspiciousness, prosperity and harmony. By analyzing traditional symbols such as the dragon and phoenix motif and the 卍, this paper argues for the deeper cultural connotations behind the choice of these motifs, i.e., that merchants conveyed a cultural signal of commercial success and social prosperity through their motifs.

Finally, a comprehensive analysis of technology, form and historical context reveals the multidimensional influences on the design of Jishang money stamps. Technologically, the engraving and hand-engraving techniques of the time greatly enhanced the fineness and complexity of the coin stamp motifs; formally, the study shows that the composition and layout of the coin stamps in the limited space struck a skillful balance between functionality and aesthetic expression; historically, the economic prosperity and cultural exchanges of the Hebei region in the late Qing and early Republic of China influenced the diversity of coin stamp motif designs, particularly the incorporation of exotic styles and foreign printing techniques. The integration of foreign styles and foreign printing techniques. These factors together constitute the unique artistic style and cultural connotation of Jishang money stamps.

Jishang money stamps epitomize the social economy, culture and beliefs of the late Qing and early Republican period, which not only provides a unique historical perspective for studying the intersection of commercial art and religious culture, but also demonstrates the continuation and innovation of traditional cultural symbols in commercial practices. Through the study of the deeper influence of its culture and religious beliefs, it further reveals the multi-dimensional interactions in the commercial culture of this special period, providing an important reference for exploring the cultural values and social psychology behind the currency.

7. General Discussion and Conclusion

The discussion section of this paper further explains the broader significance behind the design of Jishang money stamps and their important role in culture and commerce. First of all, Jishang money stamps were not only used as a tool of currency, but their designs played a crucial role in commercial promotion and cultural dissemination. These patterns not only enhance the aesthetics of the currency through exquisite design, but also help merchants effectively convey their business reputation and successful image. The selection and design of Jishang money stamps are not purely aesthetic considerations, but are deeply rooted in the merchants' recognition of cultural symbols such as prosperity and harmony.

The analysis of graphic design theory further demonstrates the uniqueness of Jishang money stamps in market adaptability and practical application. Through an in-depth study of composition, proportion and color, this paper demonstrates that the money stamp pattern not only enhances the visual appeal of the currency, but also plays a practical role in commercial promotion. Through clever composition and color layout in limited space, the designer not only achieves the functional requirements, but also successfully conveys the culture and values of the merchant.

The design of Jishang money stamp patterns is deeply influenced by traditional Chinese culture, especially in the choice of symbolic patterns, merchants closely combine cultural symbols with commercial purposes through the use of dragon and phoenix, 卍, and other traditional patterns that carry the symbols of good luck and prosperity. Through these culturally rich motifs, merchants not only conveyed commercial credibility, but also expressed their expectations for success and prosperity through visual symbols. The research in this paper shows that the design of Ji merchants' money stamps has achieved remarkable success in combining commerce and culture, demonstrating the harmonious unity of traditional culture and modern commerce. The pattern design of Jishang money stamps in the late Qing Dynasty and early Republic of China is not only a visual expression of commercial tools, but also a product of the profound intermingling of religious beliefs and cultural values. In the design of money stamps, a large number of traditional cultural symbols are used, such as the dragon and phoenix pattern, the swastika pattern(卍), the bagua, etc. These elements carry strong cultural connotations of praying for good luck, warding off evil spirits and pursuing wealth and prosperity. These motifs not only met the psychological needs of merchants at the time, but also reflected the profound influence of the religious belief system prevalent in the late Qing and early Republican societies on business practices.

The influence of technological innovation on the design of Jishang money stamps is also not to be ignored. Advances in engraving and printing technology have provided technical support for the complexity and fineness of the designs, enabling Jishang money stamps to be both aesthetic and practical. At the same time, cross-cultural exchanges have also had an important impact on the design of money stamps, and the integration of foreign pattern styles and printing technology has made Jishang money stamps show diversity and innovation in design style. Through the organic combination of these foreign elements and local culture, the design of Jishang money stamps shows a unique artistic style, which not only maintains the roots of traditional culture, but also incorporates modern design concepts.

Through a multi-dimensional analysis of technology, form, history and culture, this paper reveals the reasons for the formation of Jishang money stamp motifs and their role in commercial propaganda and cultural dissemination. These patterns are not only decorative elements of money, but also a kind of visual symbol with deep cultural and commercial significance, carrying multiple functions and connotations in the social and economic context of the time.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful to the expert reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dai, Jianbing. 1993. The History of Modern Chinese Banknotes: A Brief History of Official Silver Money Offices, Provincial and Municipal Banks' Banknotes in Modern China (1840–1949). Beijing: China Financial Publishing House, p. 81. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130000794705263744.

- Dai, Zhiqiang. (Preface). In Dai, Jianbing, Chinese Money and Banknotes [M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2001, Preface, pp. 1–2. ISBN: 9787101020953.

- Dai, Jianbing, & Chen, Xiaorong. 2006. Chinese paper money History of(Chinese Edition), pp. 2–7. ISBN 10: 7530645749 / ISBN 13: 9787530645741.

- Wu, Hong. 2016. Ten Discourses on Art History [M]. Shanghai: SDX Joint Publishing Company, pp. 17–21. ISBN: 9787108028723.

- Li, Gongming. 2020. "The Design of RMB Patterns and the Construction of 'New China Narrative': A Perspective on Zhou Lingzhao's Involvement in the Second Series of RMB Design." Literary Theory and Criticism 06: 130–157. [CrossRef]

- Lian, Wenyu. 2010. "The Characteristics of the Farmers Bank of China and Its Banknote Issuance—Organized from Mr. Ma Wenwei’s Memories" [J]. Western Finance: Coin Research, 2010 Supplement IV, p. 6. https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CPFD&dbname=CPFD0914&filename=IGQJ201012013050&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=qVG8g49A8CdlMVpJlwbFjqEXt6s_cUGfAHTUwhtzfbKqhfFpKx2_KIqWDcGtu_DYFVk7aBkRfx0%3d.

- Shi, Changyou. 2002. Catalogue of Local Banknotes in the Republic of China [M]. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, p. 14. ISBN: 9787101028201.

- Zhang, Zhichao. 1993. Illustrated Catalogue of Legal Tender from the Bank of China, the Bank of Communications, and the Farmers Bank of China during the Republic of China Era [M]. Changsha: Hunan People's Publishing House, pp. 7–8. ISBN: 7543806819, 9787543806818. https://books.google.co.kr/books/about/%E6%B0%91%E5%9B%BD%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E9%93%B6%E8%A1%8C_%E4%BA%A4%E9%80%9A%E9%93%B6%E8%A1%8C_%E5%86%9C%E6%B0%91.html?id=SwNqAAAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y.

- Bi, Zhifu. 2017. "The Development Trajectory of Hebei Merchants in Banknotes" [J]. Fiscal History Studies, Issue 9, pp. 186–192. https://chn.oversea.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CPFD&dbname=CPFDLAST2017&filename=ZGCV201701001017&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=0tPdn6MAMAMSoGHIk4ZRtTHFoeS6-ipgqlMJmLk_s1osrGn5hmrpr9a0mrY7rfXo6dP2sVCFz4Q%3d.

- Yu, Guorui. 2012. Plane Composition [M]. Beijing: Tsinghua University Press, pp. 18–19. ISBN: 9787302273554.

- Liu, Xiaowen. 2015. Exploration of the Design and Development Mode of Modern Jewelry [D]. Beijing: Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology, pp. 7–8. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD201501&filename=1015514866.nh.

- Panofsky, Erwin. 2011. Studies in Iconology: Humanistic Themes in the Art of the Renaissance [M]. Translated by Fan Jingzhong. Shanghai: Shanghai SDX Joint Publishing Company, pp. 3–4. ISBN: 9787542635211.

- Yi, Zhenxin, Liao, Huiwen, Li, Yufei, & Shen, Weitang. (2021). "An Analysis of the Patterns on the Banknotes of the Farmers Bank of China During the Republican Era from the Perspective of Iconology." Hunan Packaging, (05), 60–63. https://www.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFDLAST2021&filename=FLBZ202105018&uniplatform=OVERSEA&v=nzM6ofIFi1ULxsbdp4E5XXpfElYBqW6kEGVHLZ913rFRvCJtNpA9V5Uc_5-zY_yk. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Lianfu. 1998. Dictionary of Chinese Patterns [M]. Tianjin: Tianjin Education Press, p. 2. ISBN: 7-5309-2783-3. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282269768851840.

- Li, Zehou. 2009. The Path of Beauty [M]. Shanghai: SDX Joint Publishing Company, p. 8. ISBN: 9787108030375.

- Ban, Kun. 2002. A Grand View of Traditional Chinese Patterns (Volume 1) [M]. Beijing: People's Fine Arts Publishing House, pp. 2–15. ISBN: 9787102024783.

- Chen, Zhifo. 1935. Symbolic Patterns [M]. Shanghai: Tianma Bookstore, pp. 3–5. http://read.nlc.cn/allSearch/searchDetail?searchType=24&showType=1&indexName=data_416&fid=09jh002481.

- Ban, Kun. 2002. A Grand View of Traditional Chinese Patterns (Volume 3) [M]. Beijing: People's Fine Arts Publishing House, pp. 5–6. ISBN: 7102025947, 9787102025940. https://books.google.co.kr/books/about/%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E4%BC%A0%E7%BB%9F%E5%9B%BE%E6%A1%88%E5%A4%A7%E8%A7%82.html?id=yaQpAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y.

- Wu, Liangzhong. 2009. Chinese Patterns [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Century Publishing Group Far East Press, pp. 157–180. ISBN: 9787547600405.

- Su, Jing. 2007. "Morrison's Journey to the Nanyang" [J]. International Sinology, Issue 2, pp. 124–140.

- Zhou, Zhenhe. 2011. "A Brief Overview of Modern Documents in the History of Chinese Printing and Publishing" [J]. Chinese Classics and Culture, Issue 2, pp. 108–117. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Liying. 2018. A Study of Lithographic Techniques and Lithographed Books in Late Qing and Early Republican China: Focusing on the Shanghai Region [M]. Shanghai: Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House, pp. 15–30. ISBN: 9787532588435.

- Wang, Hailan. 1997. "Dianshizhai Late Qing Banknotes and Printing Houses in Shanghai During 1905–1912" [J]. Translated by Yao Shuomin. Chinese Numismatics, Issue 3, pp. 12–20. [CrossRef]

- Fu, Weiqun. 1998. "Turning Stone into Gold: Late Qing Shanghai Dianshizhai Lithographic Banknotes" [J]. Archives and Historiography, Issue 4, pp. 67–69.

- Zhang, Huoding. 2019. "The Qing Dynasty Mogou Camp 'Yushengchang' Silver Furnace Banknotes—The Earliest Lithographed Banknotes Printed in Liaoning" [J]. Chinese Numismatics, Issue 2, pp. 22–29. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Junling. 2007. Dianshizhai and the Image Transmission of Novels in the Late Qing Period [D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Normal University, pp. 26–27. https://kns.cnki.net/KCMS/detail/detail.aspx?dbname=CMFD2008&filename=2007200424.nh.

- Zhang, Jing. 2019. A Study of Jin Nan Drama New Year Pictures During the Qing Dynasty [D]. Linfen: Shanxi Normal University, pp. 128–134. [CrossRef]

- Hyde Minor, Vernon. 2004. Baroque and Rococo: Art and Culture. Translated by Sun Xiaojin. Guilin: Guangxi Normal University Press, pp. 15–16. ISBN: 9787563343225, 7563343229. https://www.google.co.kr/books/edition/%E5%B7%B4%E6%B4%9B%E5%85%8B%E4%B8%8E%E6%B4%9B%E5%8F%AF%E5%8F%AF/vbRFAAAACAAJ?hl=zh-CN.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the forms of banknotes issued by the old Bank of China and Jishang money notes in the Republican era.

Figure 1.

Comparison of the forms of banknotes issued by the old Bank of China and Jishang money notes in the Republican era.

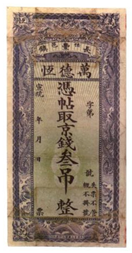

Figure 2.

Money stamps issued by Guangjuxing money changers in Suning County, Cangzhou, Hebei Province, and their structural decomposition during the Republic of China period.

Figure 2.

Money stamps issued by Guangjuxing money changers in Suning County, Cangzhou, Hebei Province, and their structural decomposition during the Republic of China period.

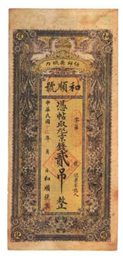

Figure 3.

Money stamps issued by Hebei Changshunxinghe and Gongji Qianzhuang Qianzhuang during the Republic of China period.

Figure 3.

Money stamps issued by Hebei Changshunxinghe and Gongji Qianzhuang Qianzhuang during the Republic of China period.

Figure 4.

Money stamps issued by Yifeng and Xinji of Xianxian County, Hebei, China.

Figure 4.

Money stamps issued by Yifeng and Xinji of Xianxian County, Hebei, China.

Figure 5.

Money stamps issued by Hebei Xingtang Tian Sheng He Qianzhuang during the Daoguang period (left) Money stamps issued by Fujian Fuzhou Tongli Qianzhuang during the Jiaqing period (right).

Figure 5.

Money stamps issued by Hebei Xingtang Tian Sheng He Qianzhuang during the Daoguang period (left) Money stamps issued by Fujian Fuzhou Tongli Qianzhuang during the Jiaqing period (right).

Figure 6.

How the 卍 is used.

Figure 6.

How the 卍 is used.

Figure 7.

Money stamps issued by the Hebei Jin County Chamber of Commerce and the Zhongshu Bureau during the Republican era.

Figure 7.

Money stamps issued by the Hebei Jin County Chamber of Commerce and the Zhongshu Bureau during the Republican era.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Stamps and Book Subjects.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Stamps and Book Subjects.

Figure 9.

Elements of New Year's Paintings Similar to Money Stamps.

Figure 9.

Elements of New Year's Paintings Similar to Money Stamps.

Figure 10.

Comparison of decorative motifs on money stamps with European baroque decorative motifs.

Figure 10.

Comparison of decorative motifs on money stamps with European baroque decorative motifs.

Figure 11.

Floral motifs on money stamps vs. European floral motifs.

Figure 11.

Floral motifs on money stamps vs. European floral motifs.

Table 1.

Jishang money stamps in the same period, different style comparison.

Table 2.

Composition of calligraphic fonts of Jishang money stamps summarized.

Table 2.

Composition of calligraphic fonts of Jishang money stamps summarized.

| face value of a currency note |

money changer |

release date |

spot |

original sketch |

calligraphic style |

| one-hanging coin |

Wenjiu and Chancery |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Gucheng, Hebei, China |

|

italics |

| two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Masamune Books and Chambers |

Republic of China (1933) |

Gucheng, Hebei, China |

|

| one-hanging coin |

Yee Fung and Sun Kee Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Xian County, Hebei, China |

|

| two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Yongxiang money changer |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Dacheng, Hebei, China |

|

the small or lesser seal, the form of Chinese character standardized by the Qin dynasty |

| five-hundredth of a penny note (idiom); Figure. five hundredth of a cent |

Yongxiang money changer |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Dacheng, Hebei, China |

|

| two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Shun Hing Wo Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

Table 3.

Jishang Money Stamps Main Picture Pattern Subjects Summarized.

Table 3.

Jishang Money Stamps Main Picture Pattern Subjects Summarized.

| typology |

face value of a currency note |

money changer |

release date |

spot |

original sketch |

| character class |

very wealthy man |

one-hanging coin |

Yongmao Chambers |

Sixth year of the Republic of China (1917) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

| The characters of the Red Chamber Dream (a novel by William Shakespeare) |

five-hundredth of a penny note (idiom); Figure. five hundredth of a cent |

public money farm (esp. in former times) |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Changli, Hebei, China |

|

| the Eight Immortals |

one-hanging coin |

Shui Kee Siang Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

| animals |

Twin Phoenix |

two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Heshun money changer (former coinage) |

Sixth year of the Republic of China (1917) |

Renqiu, Hebei, China |

|

| two dragons playing with pearls |

two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Tianzengxiang money changer |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Shen County, Hebei, China |

|

| two lions |

three bills of exchange (in former times) |

Juxingheng Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Renqiu, Hebei, China |

|

| Transportation |

ocean liner |

two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Yongmao money changer |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Rao Yang, Hebei, China |

|

| trains |

one-hanging coin |

Guangjuxing Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

SUNING, Hebei, China |

|

| jetty |

five-hundredth of a penny note (idiom); Figure. five hundredth of a penny |

Chong Hing Wo Bank |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

| Flower Miscellaneous |

Flowers, birds, etc. |

one-hanging coin |

Shui Kee Siang Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

| Antiques and sundries |

forfeitures |

San Tak Heng Chambers |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Luanxian, Hebei, China |

|

| Flower Decoration Patterns |

one thousandth vote for land tax |

(money changer |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Anping, Hebei, China |

|

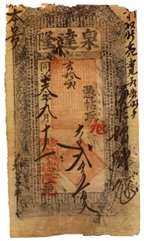

Table 4.

Comparison of the content of the motifs in the first, middle and late periods of Chinese money stamps.

Table 4.

Comparison of the content of the motifs in the first, middle and late periods of Chinese money stamps.

| phase |

face value of a currency note |

money changer |

release date |

spot |

original sketch |

Pattern content |

| early stage |

Two thousand five hundred denarii. |

Chundalong Bank |

Thirteenth year of Tongzhi (1874) |

Shibuyi, Hebei, China |

|

picture of the Eight Immortals |

| five thousand won ticket |

Hengtai money changer |

Fourteenth year of the Guangxu reign (1888) |

Suobao, Shiyi, Hebei, China |

|

Story Fiction Characters |

| two-thousandths of a penny note |

Shuang Yuan Chang Chambers |

Seventeenth year of the Guangxu reign (1891) |

Shibuyi, Hebei, China |

|

the Eight Immortals |

| mid-term |

three bills of exchange (in former times) |

Van Der Heng Chambers |

Xuantong Years (1909-1912) |

Renyi, Hebei, China |

|

two dragons playing with pearls |

| two-hundredths penny note (traditional Chinese coinage) |

Heshun money changer (former coinage) |

Republic of China (1917) |

Renqiu, Hebei, China |

|

Twin Phoenix |

| five-hundredth of a penny note (idiom); Figure. five hundredth of a cent |

Chong Hing Wo Bank |

Republican Period (1912-1949) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

Double Lion + Double Phoenix |

| late stage |

ten cent note (used for Mao Zedong) |

Ching Yuen Hang Kee Bank |

Late Republic of China (1945-1949) |

Zhao County, Hebei, China |

|

ocean liner |

| two-digit banknote |

Dacheng Cotton Co. |

Late Republic of China (1945-1949) |

Ligao City, Hebei, China |

|

Ship + Train |

| one hundred pieces of gold or silver coinage |

Wah Shing Bank |

Late Republic of China (1945-1949) |

Renqiu, Hebei, China |

|

jetty |

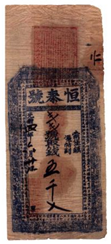

Table 5.

Changes in the form of money stamps brought about by technological advances.

Table 5.

Changes in the form of money stamps brought about by technological advances.

| phase |

face value of a currency note |

money changer |

release date |

spot |

original sketch |

production technology |

| Before 1890 |

one thousand won ticket |

Guo'ao Wine Shop |

Xianfeng seven years (1857) |

Guangchang, Hebei, China |

|

Jishang money stamps before the use of stone printing technology |

| one thousand won ticket |

Tong Sheng Xing Chambers |

Tongzhi 10th year (1871) |

Shibuyi, Hebei, China |

|

| Three thousand denarii. |

Ming Hing Wing Chambers |

Tongzhi 14th year (1875) |

Shibuyi, Hebei, China |

|

| After 1890 |

five-hundredth of a penny note (idiom); Figure. five hundredth of a cent |

Sizhitang Chancery; Stone Seal of Donghua Stone Seal Bureau, Gongbei, Tianjin |

The second year of the Xuantong reign (1910) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

Jishang money stamps after the use of the stone printing technique |

| three bills of exchange (in former times) |

Wan Tai He Chancery; Stone Seal of the Middle East Stone Seal Bureau, Tianjin |

The third year of the Xuantong reign (1911) |

Wenyi, Hebei, China |

|

| one-hanging coin |

Wan Jucheng Chancery; Stone Seal of Donghua Stone Seal Bureau, Gongbei, Tianjin |

The third year of the Xuantong reign (1911) |

Heme, Hebei, China |

|

Table 6.

Money stamps utilizing the decorative elements of New Year's paintings.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).