Submitted:

20 March 2025

Posted:

21 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Engraving Origin of the Yuan Pilu Canon

3. The Publishing and Engraving of the Yuan Pilu Canon

3.1. Engraving Timeline and Geographic Scope

3.2. Typefaces and Characters Used in Engraving

3.3. Founding of the Work

4. The Socio-Religious Context of the Yuan Pilu Canon

4.1. Religious Names of the White Lotus Society Followers

4.2. Relationships of Solicitors

4.3. The Grassroots and Sectarian Nature of the Yuan Pilu Canon

5. Dissemination of the Yuan Pilu Canon

5.1. The Scriptures Bestowed to One Hundred Monasteries: The Edition from the Song Dynasty

5.2. The Four Major Buddhist Canons as the Core

5.3. The Yanyou Canon as a Separate Text

5.4. Dissemination and Fragmentation of the Yuan Pilu Canon: Impact of Historical Turmoil

6. Conclusions

Note

-

iThe Yuan Pilu Canon元毗卢藏 is referred to as the re-engraved Pilu Canon. For detailed discussion, see He Mei's 何梅Research on Several Issues Concerning the Pilu Canon 《毗卢大藏经》若干问题考(Studies in World Religions世界宗教研究, Issue 3, 1999) and Research on Chinese Tripitaka汉文佛教大藏经研究 (China Religious Culture Publisher, 2003).

-

iiBarend ter Haar 田海argued that the Pilu Canon published in the Yuan Dynasty was a re-engraved edition覆刻本 of the Qisha Canon碛砂藏. However, Barend ter Haar cited the Taiwan version台湾版 of the Zhonghua Buddhist Canon 中华大藏经 (first series), which included a photocopy of the Song Dynasty Qisha Canon published in Shanghai between 1931 and 1936. During the compilation of this photocopy, it was discovered that parts of the Qisha Canon were missing. Due to limited resources at the time, various versions of the Qisha Canon from the Song宋, Yuan元, and Ming明 Dynasties were used to supplement the missing sections, resulting in a version resembling a patchwork edition. Since Barend ter Haar did not have access to the original Qisha Canon or its photocopied version影印本, he referenced the re-photocopied edition, which no longer preserved the original appearance of the Song Dynasty Qisha Canon.Barend ter Haar 田海Zhong guo li shi shang de bai lian jiao中国历史上的白莲教 (The White Lotus Society in Chinese History), translated by Wang Rui and Liu Ping. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2017.

-

iiiXiaochuanguanyi 小川贯弌was the first to propose identifying the fundraising groups behind the Pilu Canon published in the Yuan Dynasty. He argued that the White Lotus Sect白莲宗 referred only to certain White Lotus societies 白莲教led by well-known monks无名僧 and adhering to strict religious doctrines, such as those at Donglin Temple东林寺 on Mount Lushan庐山. In contrast, White Lotus societies widespread among the common people with less rigorous religious doctrines and lacking the guidance of prominent monks could be classified as the White Lotus Society, but not the White Lotus Sect. Xiaochuan believed that the hall associated with the Pilu Canon belonged to a mass religious group with shallow doctrines and no guidance from prominent monks, thus falling under the White Lotus Society.Please refer to Xiaochuan’s Carved Stories of Bai Lianjiao in the Yuan Dynasty (Chinese Buddhist History), 1943, Vol. 7, Issue 1, pp. 4-14)

-

ivIn 2008, two volumes of scattered copies of the Da Baoji Jing from the Pilu Canon published in the Yuan Dynasty, housed in the National Library of China, along with one volume of the Da Fang guang fo hua yan Jing大方广佛华严经 from the same canon, held in the Shanxi Library山西省图书馆, were included in the first National Rare Ancient Book Directory第一批国家珍贵古籍名录. In 2009, one volume each of the Da Baoji Jing, Da Boniepan Jing, and 27 volumes of the Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing from the Pilu Canon, collected in the Nanjing Library, as well as one volume of the Da Bore Boluomiduo Jing from the Pilu Canon, held in the Hubei Provincial Library, were added to the second list第二批国家珍贵古籍名录. Currently, the Nanjing Library holds the largest collection.

-

vLi, Fuhua 李富华He Mei 何梅 Hanwen fojiao dazangjing yanjiu汉文佛教大藏经硏究(Research on Chinese Tripitaka) ,Beijing: China Religions Culture Publisher, 2003. P. 354.

-

vi Dai, Fanyu 戴蕃豫Zhong guo fo dian kan ke yuan liu yan jiu中國佛典刊刻源流研究(Spreading of Chinese Buddhist Canon Carving Origin) ,Beijing: Bibliography and Document Publishing House, 1995.P. 101.

-

viiThe Buddhist Canon at Puning Temple大普宁寺 refers to the Puning Canon,普宁藏 engraved by Bai Yunzong白云宗. No complete sets of this canon exist in China, and it is currently primarily housed at Zojo-ji Temple增上寺 in Japan.

-

viiiDai, 1995, p.51

-

ixIn Zen Buddhism, the Huayan Jing华严经, Niepan Jing涅槃经, Baoji Jing宝积经, and Bore Jing 般若经are referred to as the four major Buddhist canons. The "Fangshan department part"房山部 in New Visits to Monuments in the Capital includes 新日下访碑录records of the continued engraving of these four major canons on the East Peak of Yunju Temple on Baidai Mountain in Zhuozhou. 涿州白带山云居寺东峰续镌成四大部经记The four canons mentioned in this context are the same as those referred to above. This shows that the term "four major Buddhist canons" 四大部经was consistently applied.

-

xLi and He. 2003.P. 354.

-

xiJianchang Prefecture 建昌州was originally part of Haihun County 海昏县during the Han Dynasty汉代. In the Liu-Song Dynasty刘宋, Haihun was divided and incorporated into Jianchang. During the Yuan Dynasty, it was renamed Jianchang Prefecture and came under the jurisdiction of Jiangxi Province江西省. Luan Prefecture陆安州, which was part of Luzhou Road 庐州路in Henan Province河南省 during the Yuan Dynasty, had its administrative offices in Hefei合肥.

-

xiiHuang, Zhongzhao, 黄仲昭Ba min tong zhi八闽通志(Bamin Annals, in Fujian Local Chronicles Collection) , vol. 76 .Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House, 1991.P. 813.

-

xiiiSong Lian et al,宋濂Yuan shi元史(The Yuan History).Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2013.pp 3198-3200.

-

xivIbid, pp. 3198-3200.

-

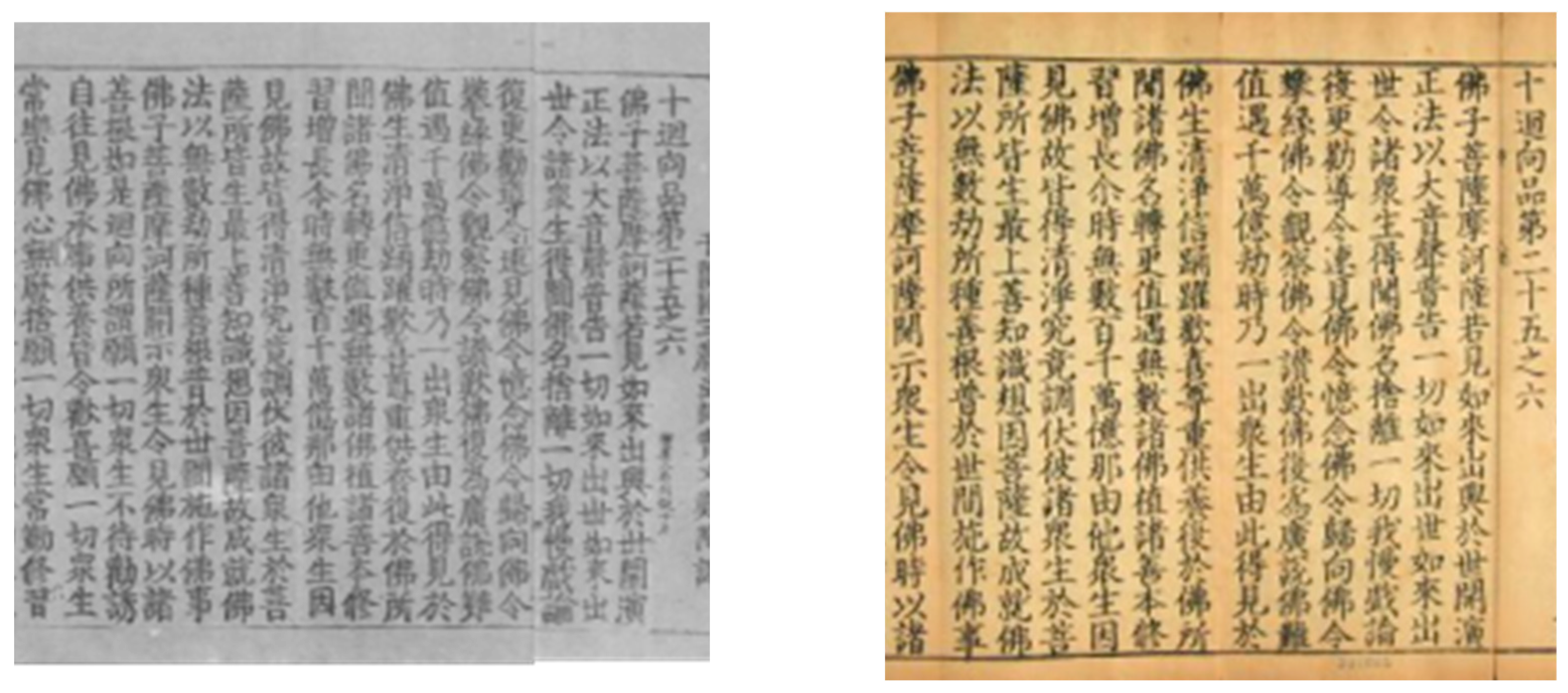

xvThis image is quoted from the website of the Imperial Household Agency's Shuling Department in Japan日本宫内厅书陵部Website:https://db2.sido.keio.ac.jp/kanseki/bib_frame?id=007075_0082.

-

xviThis zero species has been selected for the "First Batch of National Precious Ancient Books List" and is currently stored in the Shanxi Provincial Library.This image is quoted from the National Rare Ancient Books List database国家珍贵古籍名录数据库Website:http://gjml.nlc.cn/#/exploration.

-

xviiZhen, Dacheng 真大成Jia qiang han wen fo jing yi ti zi quan mian yan jiu加强汉文佛经异体字全面研究(Strengthen the comprehensive research on variant characters in Chinese Buddhist scriptures), Chinese Social Science Today, April 8th, 2022.

-

xviiiLi and He, 2003, pp. 43-51.

-

xixYang Ne 杨讷Yuandai bailianjiao yanjiu元代白莲教研究(Research on the White Lotus Society in the Yuan Dynasty), Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House, 2017. pp.72-73.

-

xxYang Ne 杨讷Yuandai bailianjiao yanjiu ziliao hui bian元代白莲教研究资料汇编(Compilation of Research Materials on the White Lotus Society in the Yuan Dynasty), Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1989. pp.3.

-

xxiIbid, p. 66.

-

xxiiLi and He, 2003, pp. 355-356.

-

xxiiiYou Biao 游彪 foxing yu renxing:songdai minjian fojiao xinyang de zhenshi zhuangtai佛性与人性:宋代民间佛教信仰的真实状态(Buddhist Nature and Human Nature: The True Status Quo of Buddhist Belief among the People in the Song Dynasty),Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science), no. 5 (2011): 93-100.

-

xxivBarend ter Haar 田海Zhong guo li shi shang de bai lian jiao中国历史上的白莲教 (The White Lotus Society in Chinese History), translated by Wang Rui and Liu Ping. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2017. p40.

-

xxvThe engraving records are cited from volume 3 the of The Interpretation of Dafoding Shoulengyan Jing 大顶首楞严经stored in the Taiwan National Central Library台湾“国家图书馆”. Website:https://rbook.ncl.edu.tw/NCLSearch/Search/SearchDetail?item=87b031c02ef3444faa3f786e8bc0c33afDc0OTA00.rH0eIummlsBsfF_rfGyzVCqzp91Amg5PIply32ZhzmQ_&image=1&page=&whereString=&sourceWhereString=&SourceID=

-

xxviEdited by Chen, Binqiang, Chen, Donglong, Wang, Wanying. Quan zhou hai shang si chou zhi lu li shi wen xian hui bian chu bian泉州海上丝绸之路历史文献汇编初编(The First Compilation of Historical Documents on the Quanzhou Maritime Silk Road), Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 2020.P. 595-596.

-

xxviiFan Hui 梵辉Fu jian ming shan da si cong tan福建名山大寺丛谈(Conversations on Famous Mountains and Grand Temples in Fujian, Fuzhou: Fujian Yixian Art Academy), 1985, P. 14.

-

xxviiiXu, Xiaowang 徐晓望.Yuan dai Fu jian shi元代福建史(History of Fujian in the Yuan Dynasty), Beijing: Jiuzhou Press, 2023,P.242.

-

xxixWang, Tiefan 王铁藩.Min du cong hua闽都丛话(Conversations on Mindu, Fuzhou: Haichao Photography Art publishing House), 1995, P. 432.

-

xxxChen, Zhiping 陈支平, Zhan, Shichuang詹石窗. Tou shi zhong guo dong nan透视中国东南(Insight into Southeast China), Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 2003,P. 717.

-

xxxiWang Tiefan王铁藩. 2023, P. 431

-

xxxiiZhu Xi. 祝熹Xi chu que li,yun shui tao yuan西出阙里,云水桃源(Leaving Queli in the west, going into a haven of clouds and waters), Nanping: Research Office of Party History and Local Chronicles of Jianyang District Committee, Nanping City, CPC, 2019. P. 246.

-

xxxiiiFan Hui.1985, P. 15.

-

xxxivEdited by Jing Hui. Xuyunheshangquanji虚云和尚全集A Collection of Master Hsu-Yun’s Works, volume 2, Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House, P. 135.

-

xxxvWang Tiefan. 2023. P. 432

-

xxxviXiaochuanguanyi 小川贯弌Lin,Ziqing 林子青.Wuxing miao yan si ban zang jing za ji吴兴妙严寺版藏经杂记(Miscellaneous Records of the Tripitaka Printed at Miaoyan Temple in Wuxing), The Voice of Dharma, Issue 10, 1988.P. 28-30.

-

xxxviiHe Mei 何梅Beijing zhihuasi yanyouzang ben kao北京智化寺元《延祐藏》本考(An Examination of the Yanyou Canon of Yuan Dynasty in Beijing Zhihua Temple), Studies in World Religions. Issue 4, 2005. P. 26-32.

-

xxxviiiThis figure was cited from National Library of China 中国国家图书馆Website: http://read.nlc.cn/OutOpenBook/OpenObjectBook?aid=892&bid=199344.0. This figure is cited from He Mei 何梅

-

xxxixBeijing zhihuasi yanyouzang ben kao北京智化寺元《延祐藏》本考(An Examination of the Yanyou Canon of Yuan Dynasty in Beijing Zhihua Temple), Studies in World Religions. Issue 4, 2005.p27.

-

xlZhang, Xiumin 张秀民Zhongguo yinshuashi中国印刷史(Zhang Xiumin history of Chinese Printing), Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House, 2006. pp. 223-224.

-

xliYu, Dafu 郁达夫mentioned in the Min you di li闽游滴沥(Travel Sketches of Fujian): “Regarding this scripture, two years ago, a Japanese scholar specializing in Buddhist scriptures came to stay at our temple to make photocopies... And now he is sorting them out in Tokyo. If this photocopied version is sorted out and published, it will cause an earth-shattering stir in the history of Buddhist studies.” It can be inferred that, the Yanyou Canon was in the Yongquan Temple涌泉寺 on Gu Mount鼓山 in 1936, and Yu Dafu had seen this canon. However, judging by the engraving era and scale, the Yanyou Canon is the Pilu Canon engraved by the Bao’en wan shou Hall in Houshan Village后山报恩万寿堂, as detailed in the Fuzhou shi hua cong shu feng ming san shan福州史话丛书·凤鸣三山(Fuzhou History Series: The Singing of the Phoenix to Fuzhou) ,Fuzhou: Fuzhou Evening News, 1995. p219.

-

xliiFuzhou shihuacongshu feng ming sanshan福州史话丛书·凤鸣三山(Fuzhou History Series: The Singing of the Phoenix to Fuzhou) ,Fuzhou: Fuzhou Evening News, 1995. pp. 220-221.

-

xliiiDeng, Meiling 邓美玲Zhongguo chanzongyou chanzong suyuan zhilv中国禅宗游·禅宗溯源之旅(Travels of Chinese Zen Buddhism: Journey to Trace the Origin of Zen), Beijing: Jiuzhou Press, 2005. P. 255.

-

xlivCheng, Zhangcan 程章灿Shi kewenxian zhi “sibenlun”石刻文献之“四本论”(The Four Versions of Stone Inscription as Literature) ,in Journal of Sichuan University Philosophy and Social Science Edition, Issue 5, 2022. P. 48.

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, Zhongzhao, 黄仲昭Ba min tong zhi八闽通志(Bamin Annals, in Fujian Local Chronicles Collection), vol. 76.Fuzhou: Fujian People's Publishing House, 1991.

- Song Lian et al,宋濂Yuan shi元史(The Yuan History).Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 2013.

- Edited by Jing Hui.净慧Xu yun he shang quan ji虚云和尚全集(A Collection of Master Hsu-Yun’s Works), volume 2.

- Zhengzhou: Zhongzhou Ancient Books Publishing House.

- National Library of China 中国国家图书馆, and China National Center for the Protection of Ancient Books 中国国家古籍保护中心,eds. 2010. Diyipi Guojia Zhengui Guji Minglu Tulu 第一批国家珍贵古籍名录图录(the antique catalog of first National Rare Ancient Book Directory). Beijing: Guojia Tshuguan Chubanshe, vol. 3.

- National Library of China 中国国家图书馆, and China National Center for the Protection of Ancient Books 中国国家古籍保护中心,eds. 2012. Dierpi Guojia Zhengui Guji Minglu Tulu 第二批国家珍贵古籍名录图录(the antique catalog of second National Rare Ancient Book Directory). Beijing: Guojia Tshuguan Chubanshe, vol. 2.

- Li, Fuhua 李富华He Mei 何梅 Hanwen fojiao dazangjing yanjiu汉文佛教大藏经硏究(Research on Chinese Tripitaka),Beijing: China Religions Culture Publisher, 2003.

- Dai, Fanyu 戴蕃豫Zhong guo fo dian kan ke yuan liu yan jiu中國佛典刊刻源流研究(Spreading of Chinese Buddhist Canon Carving Origin),Beijing: Bibliography and Document Publishing House, 1995.

- Zhen, Dacheng 真大成Jia qiang han wen fo jing yi ti zi quan mian yan jiu加强汉文佛经异体字全面研究(Strengthen the comprehensive research on variant characters in Chinese Buddhist scriptures), Chinese Social Science Today, April 8th, 2022.

- Yang Ne 杨讷Yuandai bailianjiao yanjiu元代白莲教研究(Research on the White Lotus Society in the Yuan Dynasty), Shanghai: Shanghai Chinese Classics Publishing House, 2017.

- Yang Ne 杨讷Yuandai bailianjiao yanjiu ziliao hui bian元代白莲教研究资料汇编(Compilation of Research Materials on the White Lotus Society in the Yuan Dynasty), Beijing: Zhonghua Book Company, 1989.

- You Biao 游彪 foxing yu renxing:songdai minjian fojiao xinyang de zhenshi zhuangtai佛性与人性:宋代民间佛教信仰的真实状态(Buddhist Nature and Human Nature: The True Status Quo of Buddhist Belief among the People in the Song Dynasty),Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science), no. 5 (2011): 93-100.

- Barend ter Haar 田海Zhong guo li shi shang de bai lian jiao中国历史上的白莲教 (The White Lotus Society in Chinese History), translated by Wang Rui and Liu Ping. Beijing: The Commercial Press, 2017.

- Edited by Chen, Binqiang, Chen, Donglong, Wang, Wanying. Quan zhou hai shang si chou zhi lu li shi wen xian hui bian chu bian泉州海上丝绸之路历史文献汇编初编(The First Compilation of Historical Documents on the Quanzhou Maritime Silk Road), Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 2020.

- Fan Hui 梵辉Fu jian ming shan da si cong tan福建名山大寺丛谈(Conversations on Famous Mountains and Grand Temples in Fujian, Fuzhou: Fujian Yixian Art Academy), 1985.

- Xu, Xiaowang 徐晓望.Yuan dai Fu jian shi元代福建史(History of Fujian in the Yuan Dynasty), Beijing: Jiuzhou Press, 2023.

- Wang, Tiefan 王铁藩.Min du cong hua闽都丛话(Conversations on Mindu, Fuzhou: Haichao Photography Art publishing House), 1995.

- Chen, Zhiping 陈支平, Zhan, Shichuang詹石窗. Tou shi zhong guo dong nan透视中国东南(Insight into Southeast China), Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 2003.

- Zhu Xi 祝熹Xi chu que li,yun shui tao yuan西出阙里,云水桃源(Leaving Queli in the west, going into a haven of clouds and waters), Nanping: Research Office of Party History and Local Chronicles of Jianyang District Committee, Nanping City, CPC, 2019.

- Xiaochuanguanyi 小川贯弌Lin,Ziqing 林子青.Wuxing miao yan si ban zang jing za ji吴兴妙严寺版藏经杂记(Miscellaneous Records of the Tripitaka Printed at Miaoyan Temple in Wuxing), The Voice of Dharma, Issue 10, 1988.

- He Mei 何梅Beijing zhihuasi yanyouzang ben kao北京智化寺元《延祐藏》本考(An Examination of the Yanyou Canon of Yuan Dynasty in Beijing Zhihua Temple), Studies in World Religions. Issue 4, 2005.

- Zhang, Xiumin 张秀民Zhongguo yinshuashi中国印刷史(Zhang Xiumin history of Chinese Printing), Hangzhou: Zhejiang Ancient Books Publishing House, 2006.

- Fuzhou shihuacongshu feng ming sanshan福州史话丛书·凤鸣三山(Fuzhou History Series: The Singing of the Phoenix to Fuzhou),Fuzhou: Fuzhou Evening News, 1995.

- Deng, Meiling 邓美玲Zhongguo chanzongyou chanzong suyuan zhilv中国禅宗游·禅宗溯源之旅(Travels of Chinese Zen Buddhism: Journey to Trace the Origin of Zen), Beijing: Jiuzhou Press, 2005.

- Cheng, Zhangcan 程章灿Shi kewenxian zhi “sibenlun”石刻文献之“四本论”(The Four Versions of Stone Inscription as Literature),in Journal of Sichuan University Philosophy and Social Science Edition, Issue 5, 2022.

| Volume | Serial Numbers Based on the Thousand Characters Engraving Records | Colophon |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | Long 龍 | 黄州路麻城县龚氏妙真、刘显祥、陈氏妙清、林德广、胡仲胜、程普寿、水氏一娘、朱大哥、熊觉明、李觉福、那氏五娘、邹氏一娘、宫文仲、王氏妙法、杨氏妙义,已上各刊一纸,共成一卷,报资恩有者。 |

| Gong Mizhen, Liu Xianxiang, Chen Miaoqing, Lin Deguang, Hu Zhongsheng, Cheng Pushou, Shui Yiniang, Brother Zhu, Xiong Jueming, Li Jiaofu, Na Wu Niang, Zou Yiniang, Gong Wenzhong, Wang Miaofa, Yang Miaoyi from Macheng County, Huangzhou Road. Each engraved one sheet, collectively completing one volume to repay kindness and blessings. | ||

| 18 | Shi 師 | 陆安州陆安县晏觉灯同妻子丁氏妙明共刊五纸,周觉力刊五纸,刘氏妙持同夫邹觉悔共刊二纸,高觉海刊一纸,共成一卷,报资恩有者。 |

| Yan Juedeng from Lu'an County, Lu'an Prefecture, with his wife Ding Miaoming, engraved five sheets. Zhou Jueli engraved five sheets. Liu Miaochi, with her husband Zou Juehui, engraved two sheets. Gao Juehai engraved one sheet. Altogether, they completed one volume to repay kindness and blessings. | ||

| 20 | Shi 師 | 光州固始县李觉性、胡氏三娘各刊二纸,祝有才、李诚、张汉用各刊一纸,帅氏妙清刊半纸;陆安州陆安县吴明祖同妻吴氏五娘、周氏妙新、周觉愿、胡氏四娘、尤德明、李觉广、朱氏七娘,已上各刊一纸,共成一卷,上报四恩,下资三有。 |

| Li Juexing and Hu Sanniang from Gushi County, Guangzhou, each engraved two sheets. Zhu Youcai, Li Cheng, and Zhang Hanyong each engraved one sheet. Shuai Miaoxing engraved half a sheet. Wu Mingzu from Lu'an County, Lu'an Prefecture, with his wife Wu Wu Niang, Zhou Miaoxin, Zhou Jueyuan, Hu Siniang, You Deming, Li Jueguang, and Zhu Qiniang, each engraved one sheet. Altogether, they completed one volume to repay the Four Great Kindnesses above and benefit the Three Realms below. | ||

| 29 | Huo 火 | 建昌州控鹤乡津济堂周觉布、男周觉德舍刊一函报资恩有者。 |

| Zhou Juebu and his son Zhou Juede from Jinji Hall in Konghe Country, Jianchang Prefecture, donated the engraving of one set of scriptures to repay kindness and blessings. | ||

| 50 | Wu (烏) | 江西道赣州人谢觉戒施三十两,僧久珩、谢妙心、宋觉会、四会乡大安里居何逢元、刘觉直、李八都居住温才英、李氏三各施十两,共中统三定,刊经一卷。上报四恩,下资三有,惟愿世世生生同生净土者。 |

| Xie Juejie from Ganzhou in Jiangxi Circuit donated thirty taels of silver. Monks Jiuheng, Xie Miaoxin, Song Juehui, He Fengyuan from Da'anli, Sihui Country, Liu Juezhi, Wen Caiying from Li Badu, and Li Shisan each donated ten taels of silver. Together, they donated three ding of Zhongtong banknotes and engraved one volume of scriptures, hoping to repay the Four Great Kindnesses above, benefit the Three Realms below, and be reborn in the Pure Land. | ||

| 59 | Guan 官 | 河南江北道汴梁省汝宁府光州固始县 龙山古心堂陈觉圆募众喜舍四十五定,谨刊斯经一十五卷,上报四恩,下资三有者。 |

| Chen Jueyuan from Guxin Hall on Huilong Mountain in Gushi County, Guangzhou, solicited donations from the public and received forty-five ding in contributions. He carefully engraved fifteen volumes of these scriptures to repay the Four Great Kindnesses above and benefit the Three Realms below. | ||

| 83 | Shi 始 | 江西抚州崇仁宁克伸舍刊一卷,祈荐父母宗亲,超生净界者。 |

| Ning Keshen from Chongren, Fuzhou, Jiangxi, donated the engraving of one volume of scriptures, praying for his parents and relatives to be reborn in the Pure Land. | ||

| 84 | Shi 始 | 福建道建宁路建阳县后山报恩万寿堂嗣教陈觉琳,恭为今上皇帝,祝延圣寿万安,文武官僚同资禄位,募众雕刊《毗卢大藏经》板,流通读诵者,延祐二年 月 日谨题。 |

| Chen Juelin of Bao'en Wanshou Hall in Houshan Village, Jianyang County, Jianning Road, Fujian Circuit, solicited public donations to carve the printing blocks of the Buddhist Canon, praying for the eternal longevity of the emperor and prosperity for civil and military officials. Respectfully inscribed in the second year of Yanyou reign. |

|

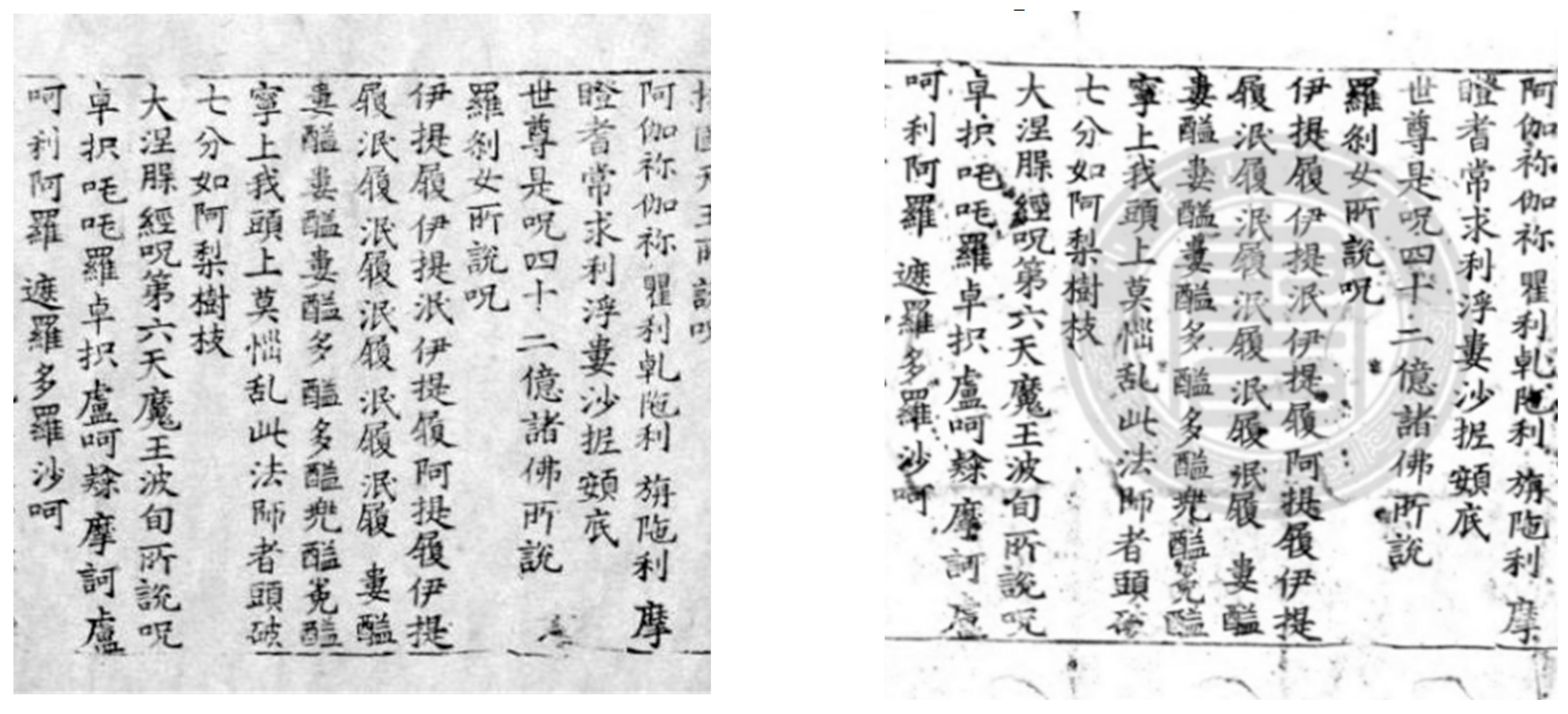

The Standard Form |

The Vulgar Forms of the Song Pilu Canon |

The Vulgar Forms of the Yuan Pilu Canon |

| 藏 软 多 差 复 教 切 往 厌 此 比 |

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).