3. Research Location

Figure 1.

Location of the La Maddusila Tomb Complex.

Figure 1.

Location of the La Maddusila Tomb Complex.

The La Maddusila Tomb Complex is located in Pancana Village, Tanete Rilau District, Barru Regency, South Sulawesi. Astronomically, it is located at 04o 32’ 1.33’‘ south latitude and 1190 35’ 26.69” east longitude, with an elevation of 13 meters above sea level (masl). The La Maddusila Tomb Complex faces north with the entrance on the south side. The boundaries of the site are as follows: to the north, it is bordered by coconut trees, palm trees, and banana trees; to the east, it is bordered by palm trees, teak trees, and banana trees; to the south, it is bordered by coconut trees; and to the west, it is bordered by coconut trees and palm trees.

Access to the La Maddusila Tomb Complex can be reached by two-wheeled vehicles via paved and concrete roads. The site is surrounded by iron fences and walls. The types of plants found in this complex include coconut trees, palm trees, banana trees, teak trees, and wild plants. There are 11 graves in the La Maddusila Tomb Complex, 5 of which are located inside the fence and 6 outside the fence. Inside the fence, there is a brick fort structure.

Figure 2.

Site Plan of La Maddusila Tomb Complex.

Figure 2.

Site Plan of La Maddusila Tomb Complex.

We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex

Figure 3.

Location of the We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex.

Figure 3.

Location of the We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex.

The We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex is located in Pancana Village, Tanete Rilau District, Barru Regency, South Sulawesi. Astronomically, it is located at 04o 31’ 35.88” south latitude and 119o 34’ 57.77” east longitude, with an elevation of 12 meters above sea level (masl). The We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex faces west. The boundaries of the site are as follows: to the north it borders a village, to the east it borders a mosque and a village, to the south it borders a plantation, and to the west it borders the sea.

Access to the We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex can be reached by two-wheeled or four-wheeled vehicles. The site is surrounded by a concrete fence combined with iron bars. The types of vegetation found in this complex include mango trees, jasmine flowers, asoka flowers, frangipani flowers, and banana trees. There are 44 graves in the We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex. There are two buildings in this complex. Building I contains five graves, one of which is the grave of Datu We Tenri Olle. The floor plan of Building I is rectangular with a domed roof. Building I has one double door and two windows made of iron trellis. The entire building is painted white but is now covered in moss. At the top of Building I, there is an inscription written in Lontara script and Dutch Latin script. Meanwhile, Building II has two tombs, one of which is the tomb of Pancaitana. Building II has a rectangular floor plan made of bricks and a tiled roof. Building II has one damaged double door and four windows.

Figure 4.

Site Plan of We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex.

Figure 4.

Site Plan of We Tenri Olle Tomb Complex.

4. Results and Discussion

Based on the results of the transliteration and transcription of the inscriptions in the calligraphy, the type, content, and meaning of the writings found in the La Maddusila and We Tenri Olle Tomb Complexes can be identified. The inscriptions in both complexes employ Arabic script and the Lontara script.

1. La Maddusila Tomb Complex

Tomb 1

On the northern and southern sides of the tombstone, Arabic calligraphy is inscribed. The inscription on the northern side reads:

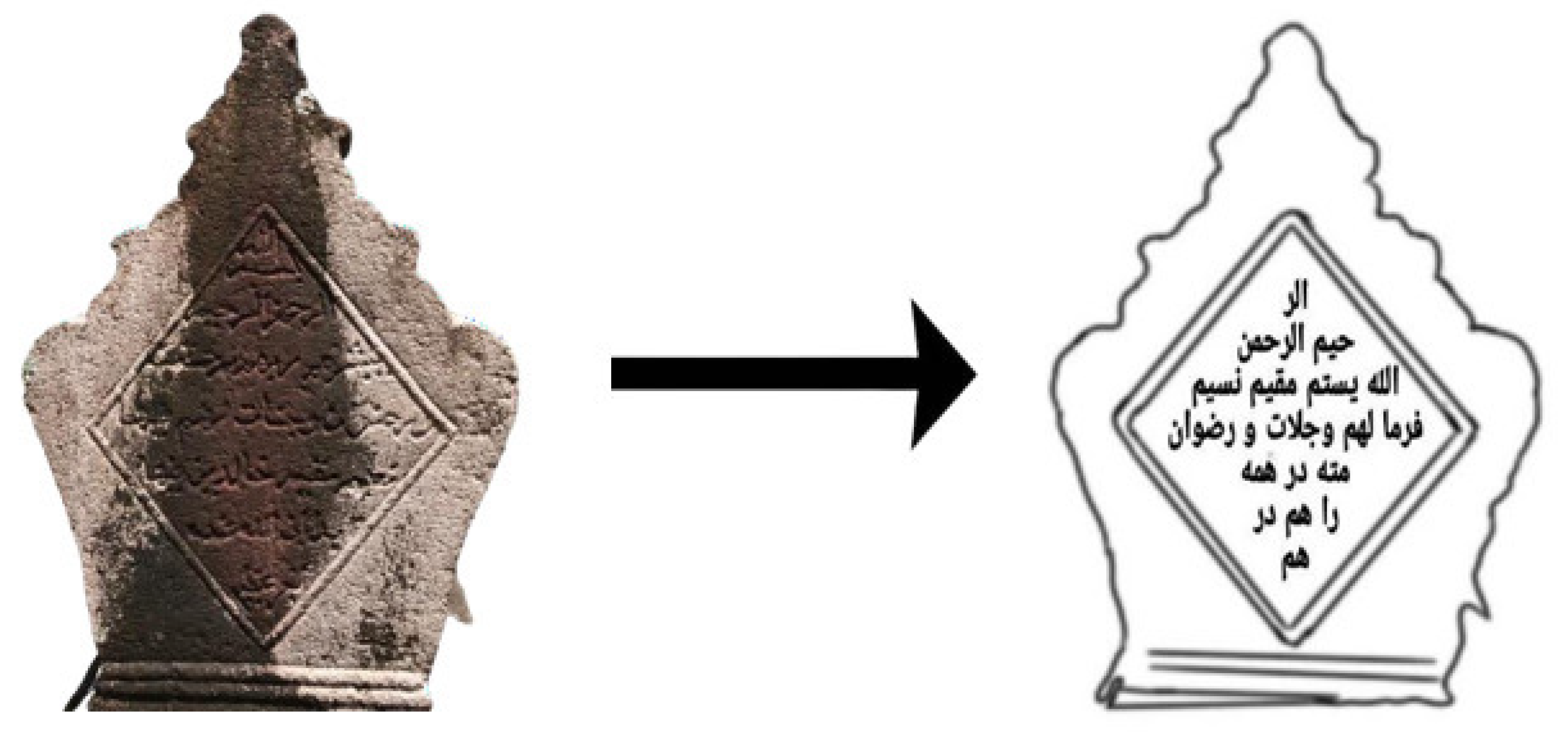

Figure 5.

Sketch of the North side headstone of tomb 1.

Figure 5.

Sketch of the North side headstone of tomb 1.

فَاطِمَةُ بِنْتُ……. رَجِعَتْ إِلَى رَحْمَةِ ٱللّٰهِ ٱلسَّبْتُ……. سَنَةَ

“Fatimah binti…..roje’ah ila rahmatillahi assabtu….sana…”

Translation: Fatimah binti... was buried on Saturday... in the year...

This inscription is only partially legible due to the weathered surface of the tombstone, making it difficult to determine the full identity of the individual buried there. On the southern side of the tombstone, the following inscription is found:

Figure 6.

Sketch of South side gravestone of grave 1.

Figure 6.

Sketch of South side gravestone of grave 1.

South side gravestone reads:

خَيْرَ سِتِي فَاطِمَةُ،….. الْمَوْتُ ... يَا رَبَّنَا ارْحَمْنَا ... جَعَلْنَا هَذَا فَضْلٌ مِنْ ...

“khaira siti….fatimah almautu….ya robbana arhimna….jaalama hadza fadzunmin….”

Translation:

“It reads: ‘The honorable... the death of Fatimah... O our Lord, have mercy on us... and make this a blessing.”

This calligraphy represents a prayer for the deceased, pleading for God’s mercy and honor to be bestowed upon her. The script used is in Khat Naskhi (Naskh style).

Grave 2

The northern headstone of this grave features a passage from Surah Al-Anbiya, verses 101–103:

Figure 7.

Sketch of the North side headstone of grave 2.

Figure 7.

Sketch of the North side headstone of grave 2.

The inscription of the North side headstone is found in Surah Al-Anbiya verses 101-103 which reads as follows

“Innal-lażīna sabaqat lahum minnal-ḥusnā, ulā’ika ‘anhā mub‘adūn(a). Lā yasma‘ūnaḥasīsahā, wa hum fīmasytahat anfusuhum khālidūn(a). Lā yaḥzunuhumul-faza‘ul-akbaru wa tatalaqqāhumul-malā’ikah(tu), hāżā yaumukumul-lażī kuntum tū‘adūn(a).”

Translation:

“It means: Indeed, those for whom the best [reward] has preceded from Us—they will be kept far away from [Hell]. They will not hear its slightest sound, and they will abide in what their souls desire. The greatest terror will not grieve them, and the angels will receive them, [saying], ‘This is your Day which you have been promised.’“

This calligraphy reflects the promise of paradise for the faithful. It serves as a reminder of God’s greatness and as a symbol of hope for eternal life in the Hereafter.

The southern side of the gravestone contains an inscription from Surah At-Tawbah, verse 21:

Figure 8.

Sketch of the South side headstone of grave 2.

Figure 8.

Sketch of the South side headstone of grave 2.

بِسْمِ اللّهِ الرَّحْمَنِ الرَّحِيْمِ

يُبَشِّرُهُمْ رَبُّهُمْ بِرَحْمَةٍ مِنْهُ وَرِضْوَانٍ وَجَنَّاتٍ لَهُمْ فِيهَا نَعِيمٌ مُقِيمٌ

“Bismillahirrahmanirrahim, yubasysyiruhum rabbuhum birahmatim minhu wa ridwaniw wajannatil lahum fiha na’imum muqim (un).”

Translation:

“In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious, the Most Merciful.”

Their Lord gives them glad tidings of mercy from Him, His pleasure, and gardens [of Paradise], wherein they will have lasting joy.

This inscription conveys a message of glad tidings for the believers who have struggled in the path of Allah. It reflects divine promises of eternal reward for their devotion and sacrifice. The types of script used are Naskhi and Thuluth.

Grave 3

The northern and southern gravestones contain dhikr (remembrance phrases of God):

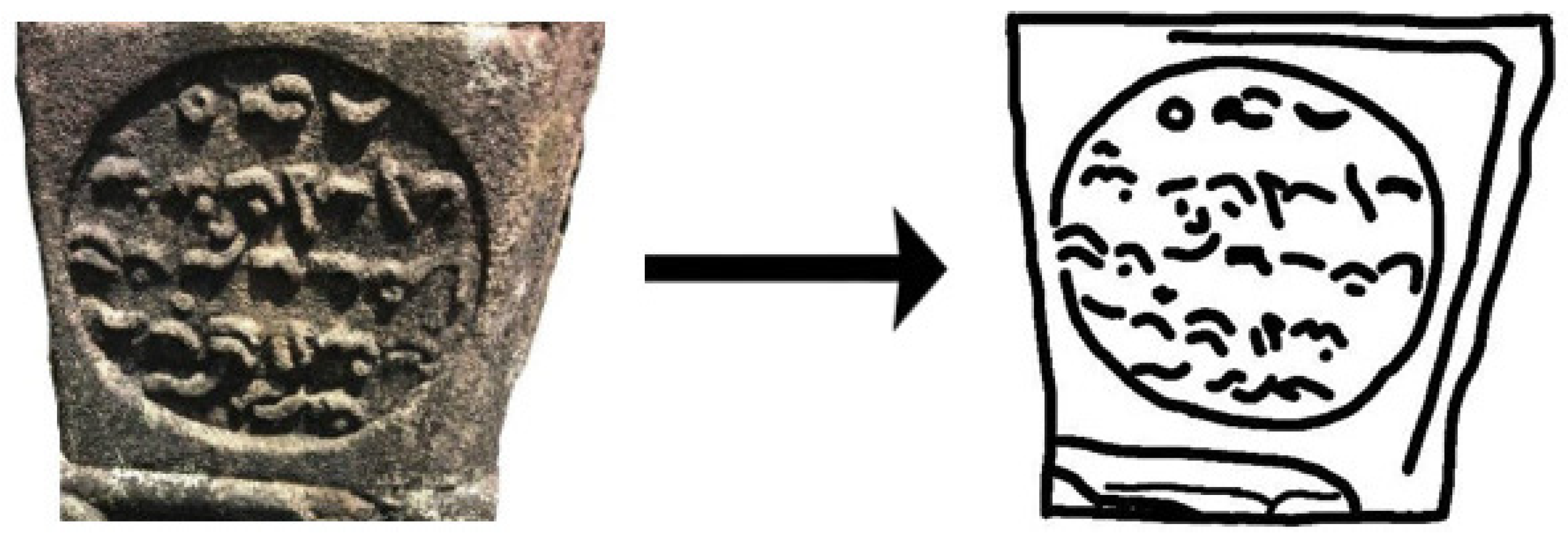

Figure 9.

Sketches of the headstones on the North and South sides of grave 3.

Figure 9.

Sketches of the headstones on the North and South sides of grave 3.

“Ya Hayyu Ya Qayyum, Ya Hayyu Ya Qayyum” “laa ilaha illallah wahdahu laa syarika lah lahul mulku wa lahul hamdu wa huwa‘ala kulli syai’in qodir”

Translation:

“O Ever-Living, O Self-Subsisting... There is no deity but Allah, He has no partner. To Him belongs the dominion and all praise. He is capable of all things.”

This dhikr (remembrance of God) is commonly recited after prayer as a form of glorification and a plea for forgiveness from Allah. The script used is Naskhi calligraphy.

Grave 4

The northern gravestone (

Figure 8) contains a supplication written in Arabic:

Figure 10.

Sketch of the North side headstone of grave 4.

Figure 10.

Sketch of the North side headstone of grave 4.

للّٰهُمَّ اجْمَعَنَا هَذَا الكَبِيرِ خَيْرٌ مِنْ أُمْرِي وَ خَيْرٌ مِنَ السَكَانَتِي فَعَلَهُ لَهُرَوْضَةً مِنَ الرَيَاضِ الجَنَّةِ يَا رَبَّ العالَمِين

“Allahummaje’ maana hadzal kaberi khoirun min umri wa khaoirun minas ssakanati fa’lahu lahu roudatan minrayatil jannati ya rabbal alamin”

Translation:

“O Allah, make this grave a good and peaceful place, and a garden among the gardens of Paradise.”

This inscription serves as a prayer for safety and a plea that the grave becomes a blessed resting place. On the same side, there is also an inscription in Lontara script:

“Iyanae jerana Petta Janggo matinroe ri Pancana.”

Translation:

“This is the tomb of Petta Janggo, who passed away in Pancana.”

The southern side of the tomb bears an inscription:

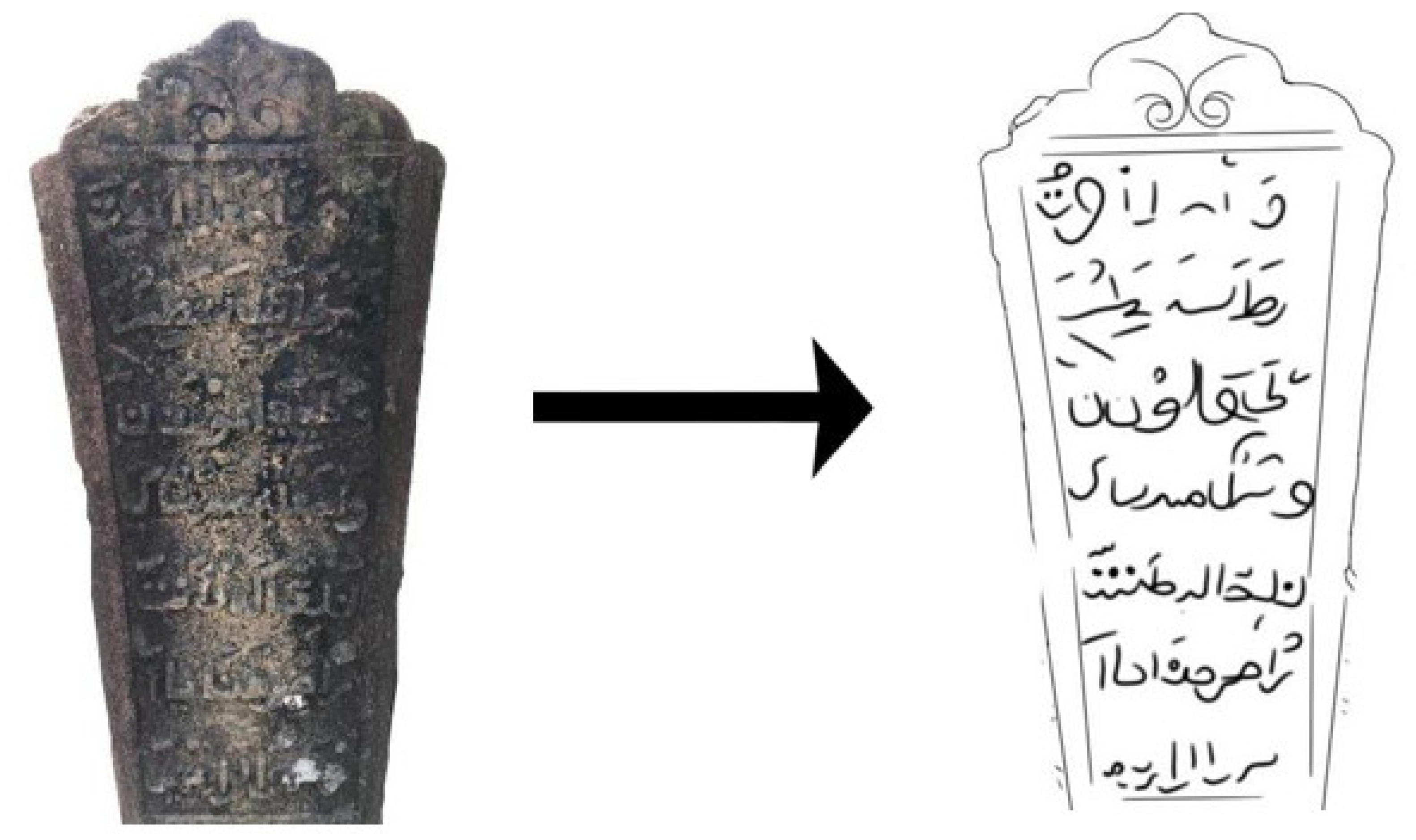

Figure 11.

Sketch of the headstone on the north side of grave 4.

Figure 11.

Sketch of the headstone on the north side of grave 4.

Figure 12.

Sketch of the South side headstone of grave 4.

Figure 12.

Sketch of the South side headstone of grave 4.

دُفِنَ وَٱجَ المَوْتَ بُرهَان بِنْ النَّصِرُ تَلِحِل مَوْتَنِي وٱج المَوتَ كَمَا مِنَ الخَوفَ فِي أنْتَ رَوْضٍ هُنا يَاأَرْحَمَ الرَّاحِمِينْ

“Dufina waj’al mauta Burhan bin an-nashiru talihil mautatani waj’al mauta kama minal khoqa fi anta raudin huna yaarhammarrohimin”

Translation:

“Burhan bin An-Nasir was buried and passed away. May this death mark the beginning of God’s pleasure and mercy.”

The type of script used on the northern side is Naskhi script combined with Lontara characters, while the southern side employs Naskhi script.

2. We Tenri Olle Cemetery Complex

Grave 1

The left side of the northern headstone contains Arabic calligraphy:

Figure 13.

Sketch of the North side headstone of tomb 1.

Figure 13.

Sketch of the North side headstone of tomb 1.

اَللهم صَلِّ عَلَى سَيِّدِنَا مُحَمَّدٍ وَعَلَى آلِ سَيِّدِنَا مُحَمَّدٍ

“Allahumma Sholli Ala Sayyidina Muhammad”

Translation:

“O Allah, bestow Your blessings upon the Prophet Muhammad.”

The right side contains the Islamic declaration of faith (shahada):

ا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ مُحَمَّدٌ رَسُولُ ٱللَّٰهِ

“Lailahaillallah Muhammadarrasulullah”

Translation:

“I bear witness that there is no God but Allah, and I bear witness that Prophet Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah.”

Meanwhile, on the main body of the tombstone, there is Arabic calligraphy in the form of a dhikr (remembrance) which reads:

إِلهِي لَسْتُ لِلْفِرْدَوْسِ أَهْلاً وَلاَ أَقْوَى عَلىَ النَّارِ الجَحِيْمِ فَهَبْ ليِ تَوْبَةً وَاغْفِرْ ذُنُوْبيِ فَإِنَّكَ غَافِرُ الذَّنْبِ العَظِيْمِ

“Ilahi lasta lilfirdauz ahlang wala aqwa ala naril jahiem. Fahabli taubatan waghfirdzunubi, Fainnaka ghafirudz dzmbil ‘adziim”

Translation:

“O Allah, I am not worthy of the Paradise of Firdaus, nor can I endure the torment of Hell. So accept my repentance and forgive my sins, for indeed You are the Most Forgiving.”

The southern side of the tombstone contains an inscription written in Lontara script:

“Ri eppa’ Syawal sanatan albaa’i 1328 ri aksera oktabire, ri taung 1910 nallinrung iyawaee datueE ri Tanete matinroe ri akuasana ri bola sadana ri Pancana”

Figure 14.

Sketch of gravestone on the south side of tomb 1.

Figure 14.

Sketch of gravestone on the south side of tomb 1.

Translation:

“On the 4th of Shawwal in the year Al-Ba’i 1328 H / 9 October 1910 CE, the King of Tanete passed away in his palace in Pancana.”

The types of scripts used are Thuluth script (outer edges), Naskh script (main body of the tombstone), and Lontara script (southern side).

Tomb 2

The northern side of the tombstone contains the following calligraphy:

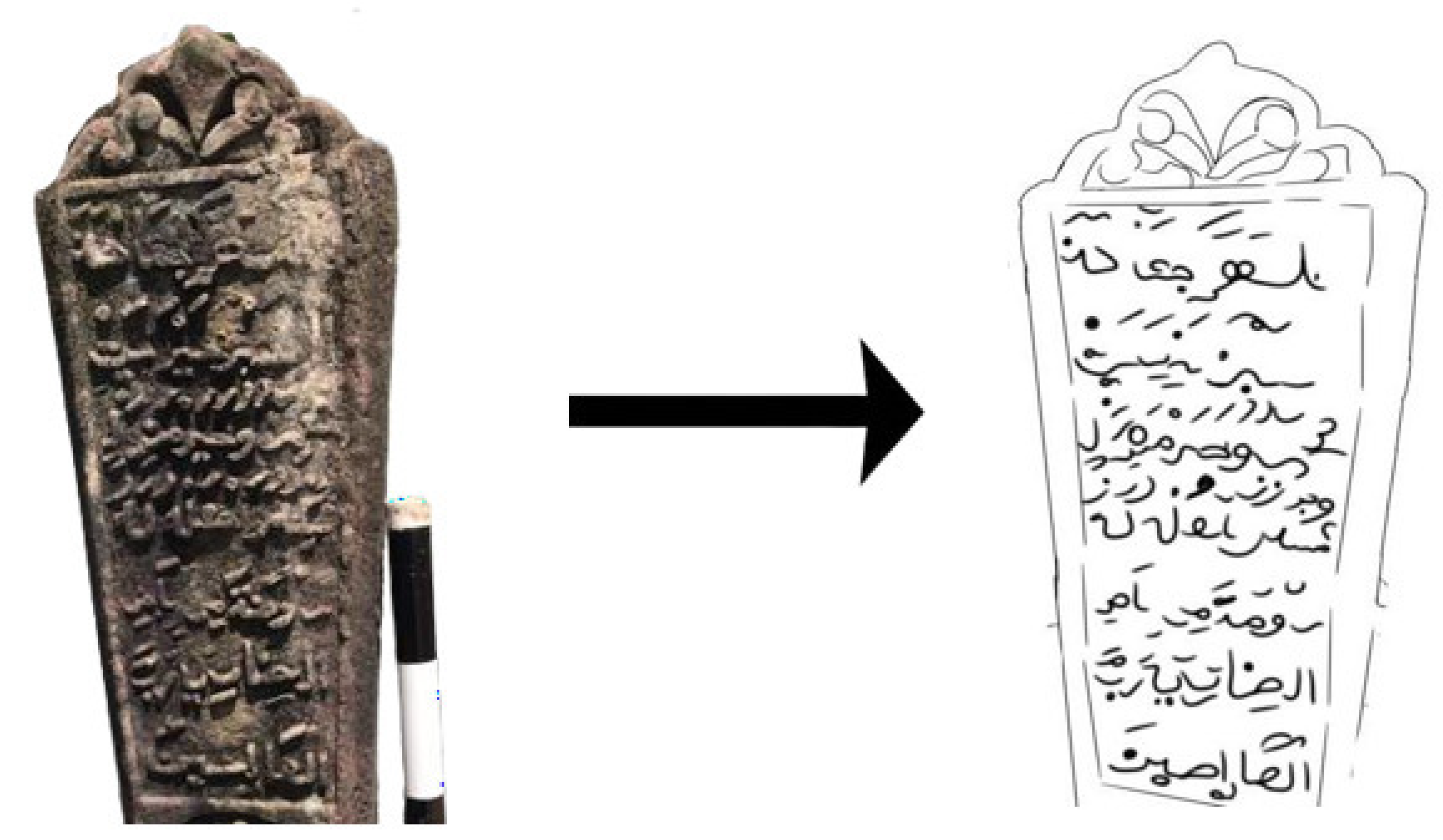

Figure 15.

Sketch of the North side headstone of tomb 2.

Figure 15.

Sketch of the North side headstone of tomb 2.

“Ya hannan ya mannan ma rallahu rahallahu muhammad”

Translation:

“O Most Compassionate, Most Benevolent... Lord of the Prophet Muhammad.”

This dhikr (remembrance) is commonly recited as a form of supplication for divine mercy and intercession. The type of script used is Kufi script.

Thus, the content and form of the inscriptions found in both cemetery complexes reflect a diversity of functions serving not only as markers of identity but also as tools for religious propagation and expressions of the spiritual values of the local Muslim community. These inscriptions demonstrate a harmonious integration between the art of Islamic calligraphy and local traditions, particularly through the use of Arabic calligraphic styles and the Lontara script.

The Meaning of Inscriptions

Based on the results of transliteration and transcription of the inscriptions found at the La Maddusila and We Tenri Olle burial complexes, the content and underlying meanings can be discerned. These inscriptions, written in Arabic and Lontara scripts, serve as evidence of the development of Islam in the region. The use of Arabic inscriptions on tombs as a form of Islamic artistic expression has been known since the 11th century CE, even before Islam became widespread in the Indonesian archipelago. One example is the tomb of Fatimah binti Maimun, who passed away in 495 H/1082 CE in Gresik, which is recognized as the oldest Islamic tomb in Indonesia [

14]. The practice of inscribing tombstones continued in line with the expansion of Islam. In addition to functioning as identifiers of the deceased’s name and date of death, these inscriptions also served as a medium for Islamic proselytization [

15].

Through archaeological studies of ancient graves, various crucial pieces of information can be obtained, such as the identity of the individual buried, decorative elements, architectural forms, burial placement patterns, chronology (date inscriptions), and the content of the inscriptions. The information about the deceased often includes more than just their name, such as their lineage, position held during life, year of birth, and time of death. These details are typically inscribed on the headstone or footstone [

16].

An Overview of Cultural Development in Tanete Region during the 19th Century

The distribution of ancient settlements and burial sites serves as the focus of study in settlement archaeology, burial archaeology, spatial archaeology, and political archaeology. From the typological aspect of the tombs, a shift in the understanding of death can be observed, which evolved from the 16th to the 20th century. The four burial sites examined represent four distinct phases of development.

The tombs of Petta Pallase-lase’e and Datu Gollae reflect the initial stage, characterized by monumental dome-shaped tombs. This style resembles ancient tombs such as those of Sultan Hasanuddin in Gowa and the Kings of Tallo, which also feature domed structures. The second phase is represented by the tomb of We Tenri Leleang, marked by ornamental enclosures (jirat) dominated by tendril motifs as decorative elements. The third phase is seen at the Maddusila site, which emphasizes Arabic calligraphy carved in detail and precision, displaying Islamic expressions through art. The fourth phase is the We Tenri Olle tomb complex, which features a dome architecture influenced by European (Dutch) style. This type of dome became a trend in the 19th century, as also seen at the Lajangiru Tomb in Bontoala (Makassar) and the Katangka Tomb site (Gowa).

Archaeologically, the four tombs of the Tanete royalty reflect the sociopolitical dynamics of their respective periods [

1]. The burial traditions were deeply rooted in Islamic values. The transformation in the understanding of Islamic teachings, especially regarding death, is evident in the variation of tomb forms across each phase. The forms of the tombs of Petta Pallase-lase’e and Datu Gollae mark the early stage, with monumental characteristics and strong prehistoric influences. The second stage is represented by We Tenri Leleang’s tomb, which features ornamental enclosures with tendril motifs. The third stage, at Maddusila, showcases a pronounced use of Arabic calligraphy meticulously carved. The final stage, We Tenri Olle’s tomb, is distinguished by its domed form with European (Dutch) architectural influence.

This transformation in tomb forms illustrates the evolving mindset of Tanete’s society and rulers, influenced by Islamic, pre-Islamic, and external values. The religious transformation of Tanete’s people and elites from the 16th to the 20th century is reflected through architectural expressions and the diversity of tomb inscriptions. In other royal burial sites in South Sulawesi, such traces of transformation are now difficult to identify, as many ancient tombs have been damaged or lost [

1].