Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

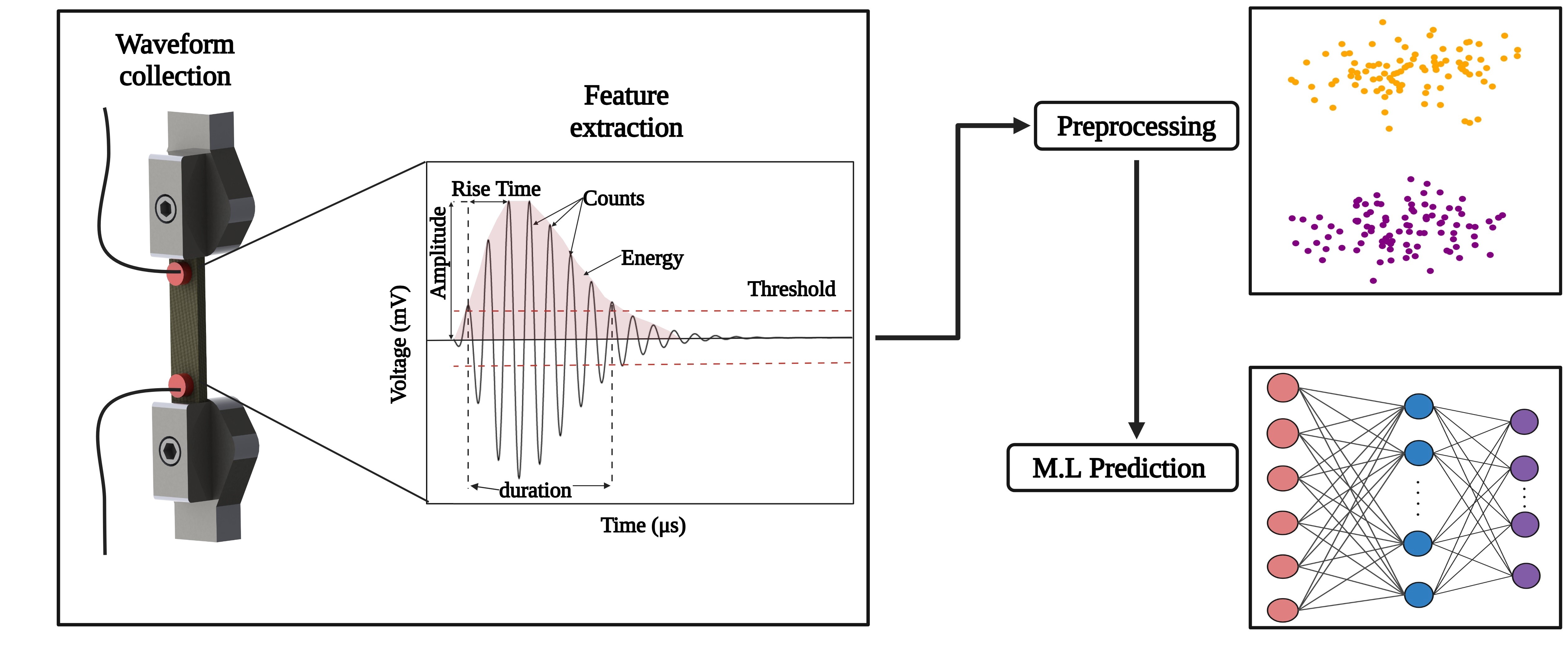

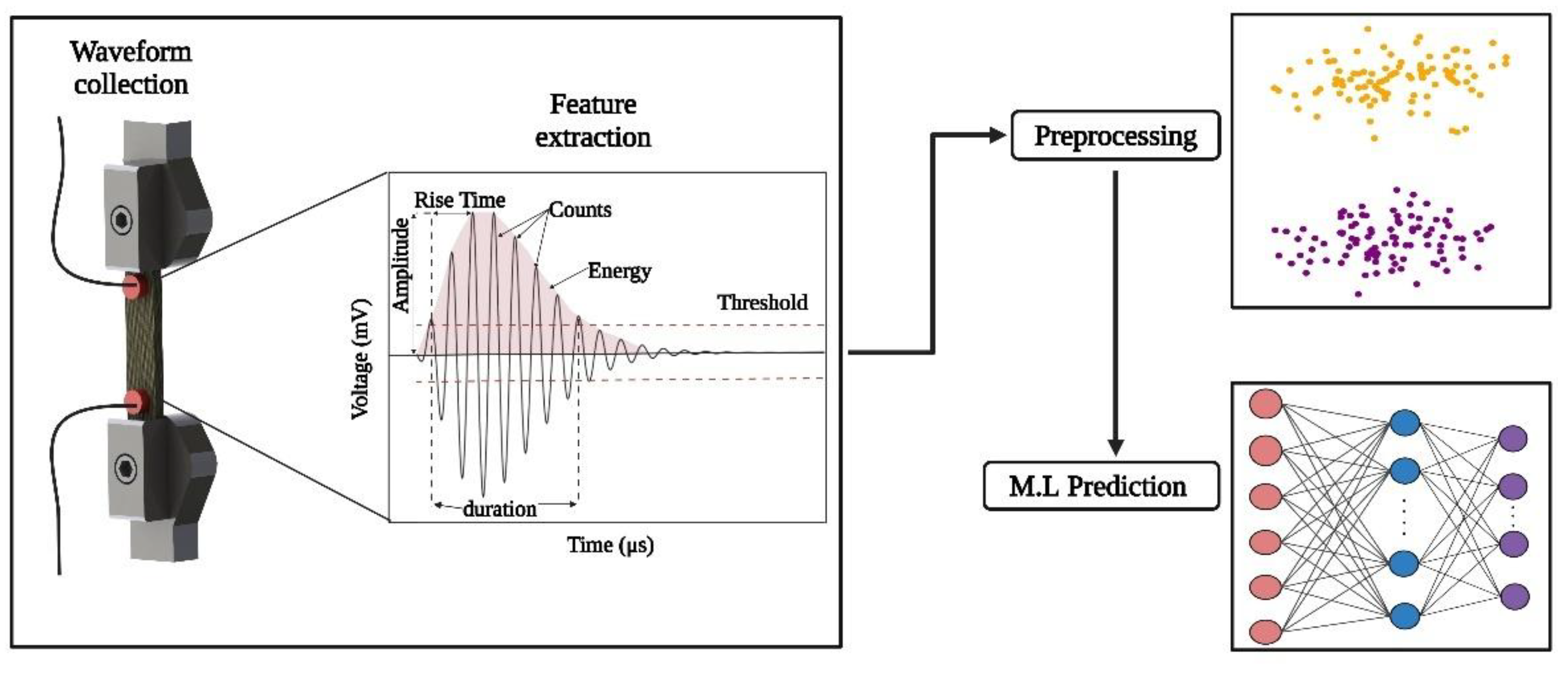

This paper offers an experimental approach to use machine learning (ML) models and Acoustic Emission (AE) data for the identification of damage mechanisms and predict the mechanical properties of 3D printed bio-composite. The specimens were produced using a bio-filament made of a PLA matrix reinforced with 10% wt. of Lygeum spartum fibers. AE signals were gathered during tensile and flexural tests in order to monitor the progression of damage under mechanical loading. subsequently, using Random Forest Regression (RFR), Support Vector Regression (SVR), Artificial Neural Network (ANN), and Decision Tree (DT) models, the stress levels of the specimens under both test conditions were predicted. These algorithms were trained with 80% of the data, in a Python environment. 20% remained, to be used for testing. The models' accuracy was assessed using R-squared (R²) and Mean Squared Error (MSE) metrics. While the other models also demonstrated outstanding prediction capabilities for both tensile and flexural stresses, the RFR model outperformed the others. In addition, 5-fold cross-validation yielded results consistent with the hold-out test, further validating the models' accuracy. This research demonstrates how well these machine learning algorithms analyze AE data for material property evaluation, paving the way for data-driven approaches in material testing and health monitoring.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Feed Filament Production

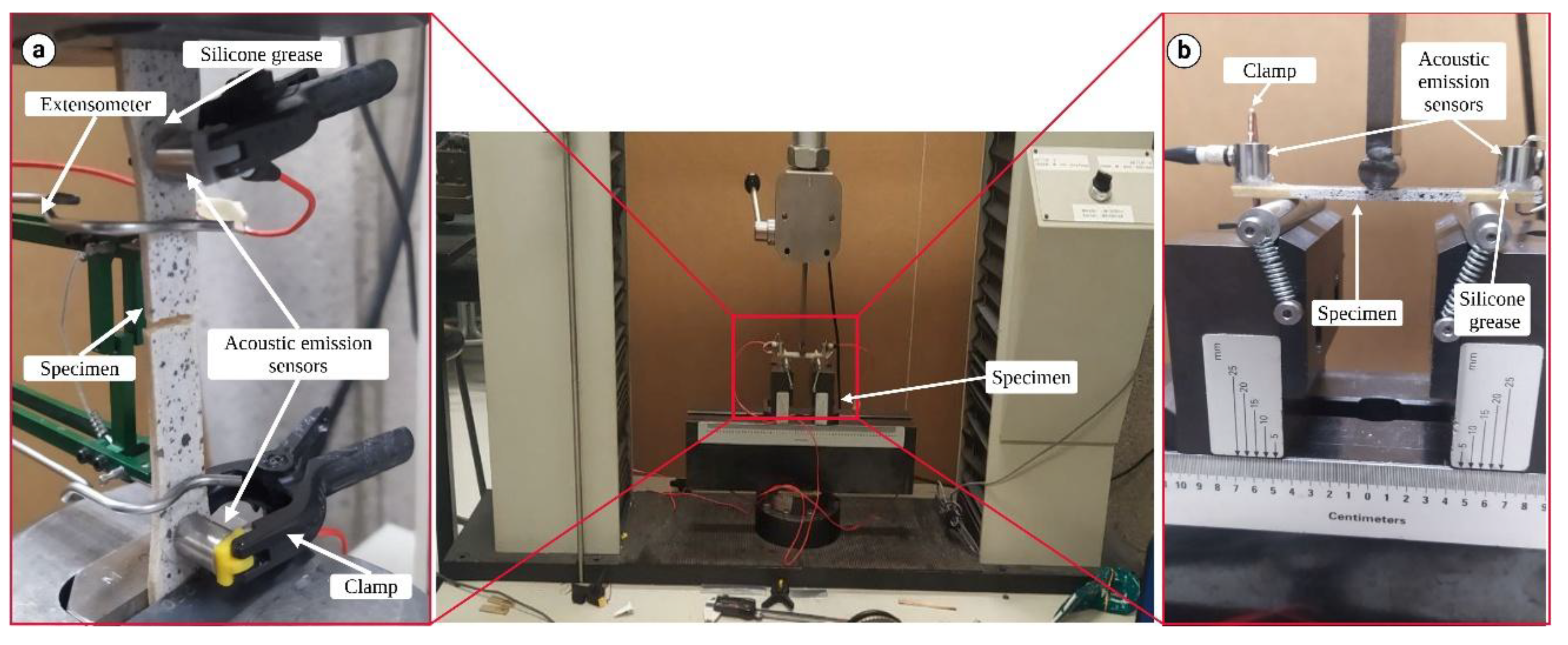

2.2. Mechanical Testing and Acoustic Emission Signal Recording

2.3. Machine Learning Models

2.4. Preparation of Acoustic Emission Data

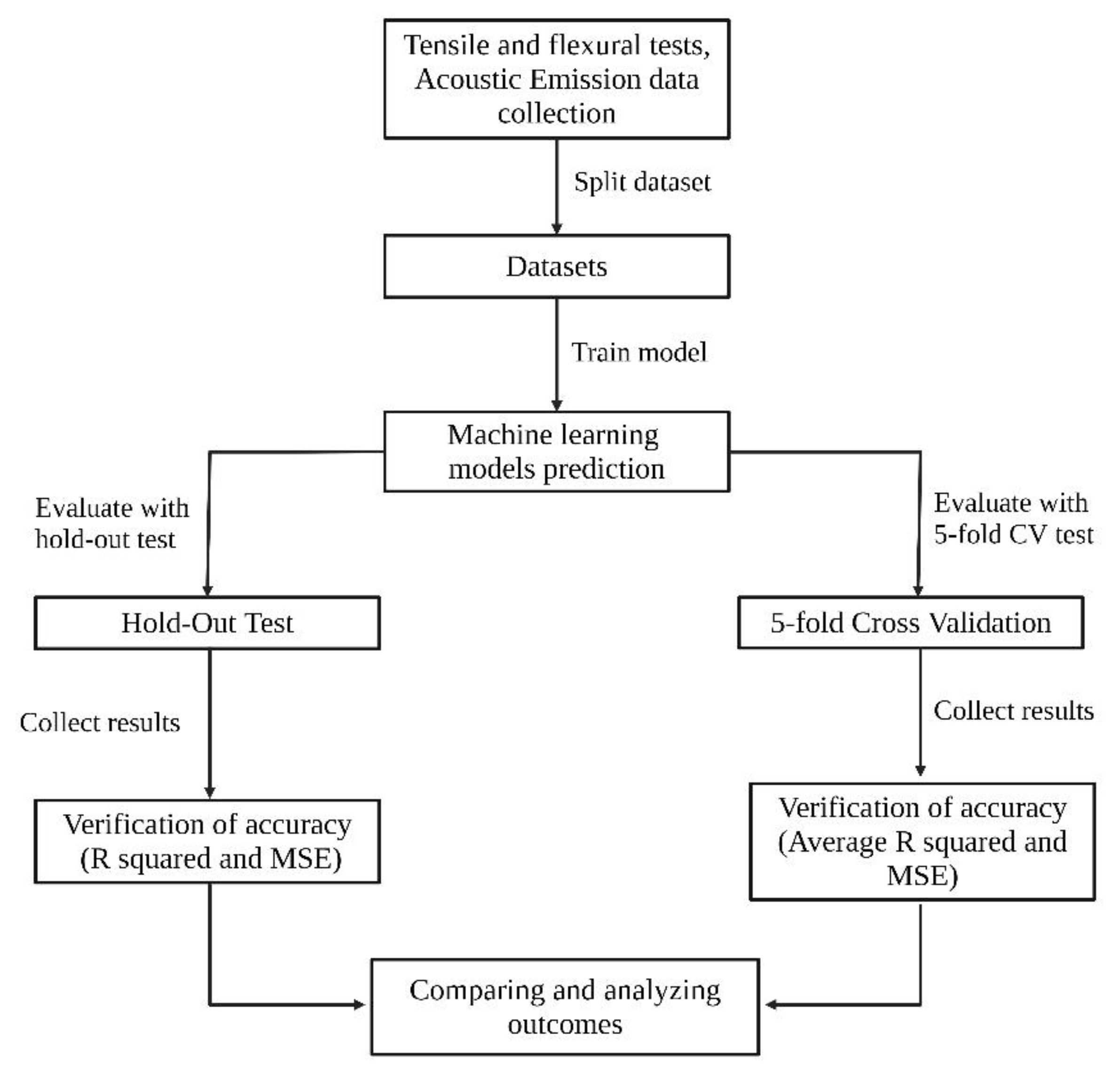

2.5. Cross-Validation and Hold-Out Evaluation

2.6. Verification of Accuracy

2.7. Damage Mode Identification Using K-Means Clustering Algorithm

3. Results and Discussion

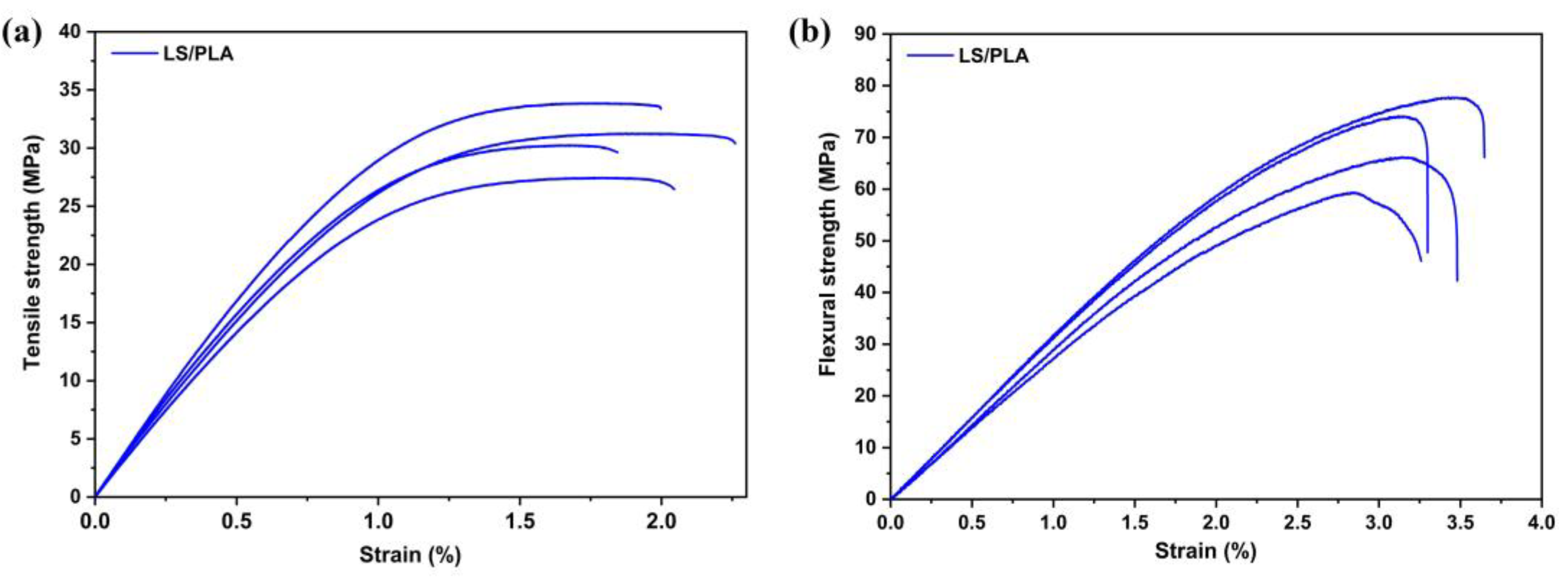

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.2. Analysis of Damage Using Acoustic Emission

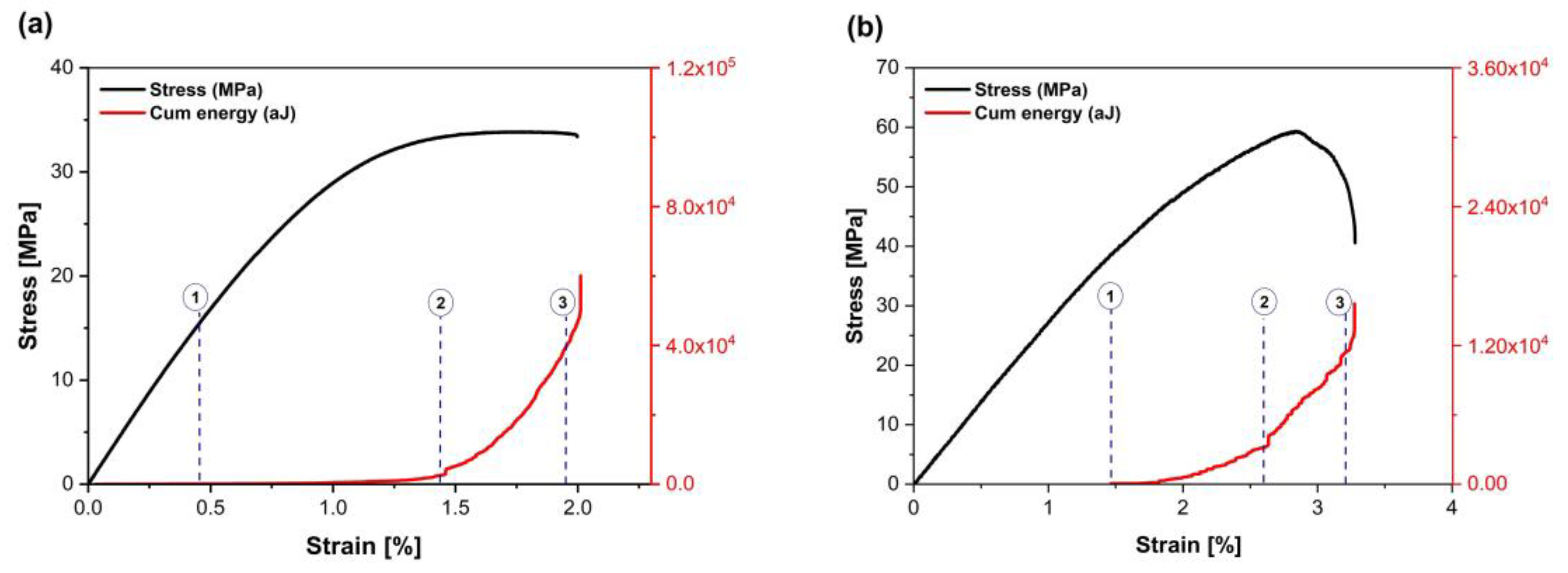

3.2.1. Damage Evolution

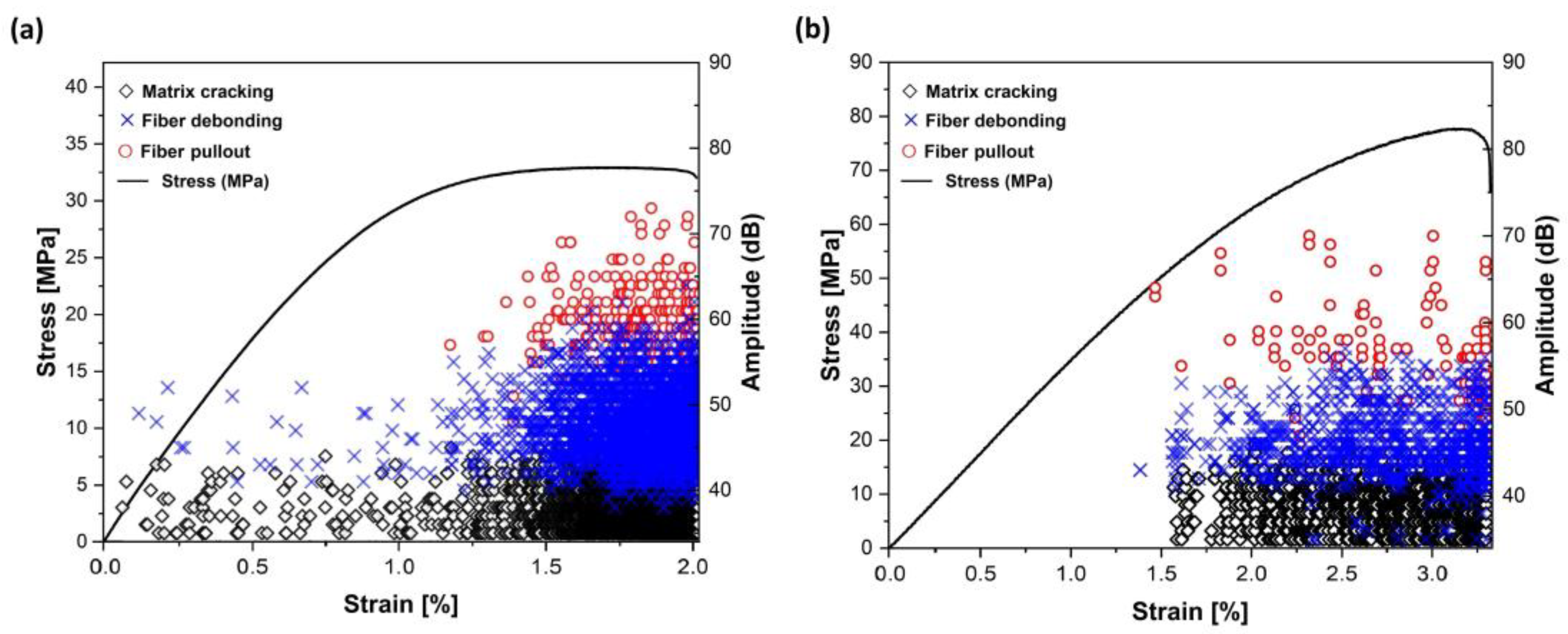

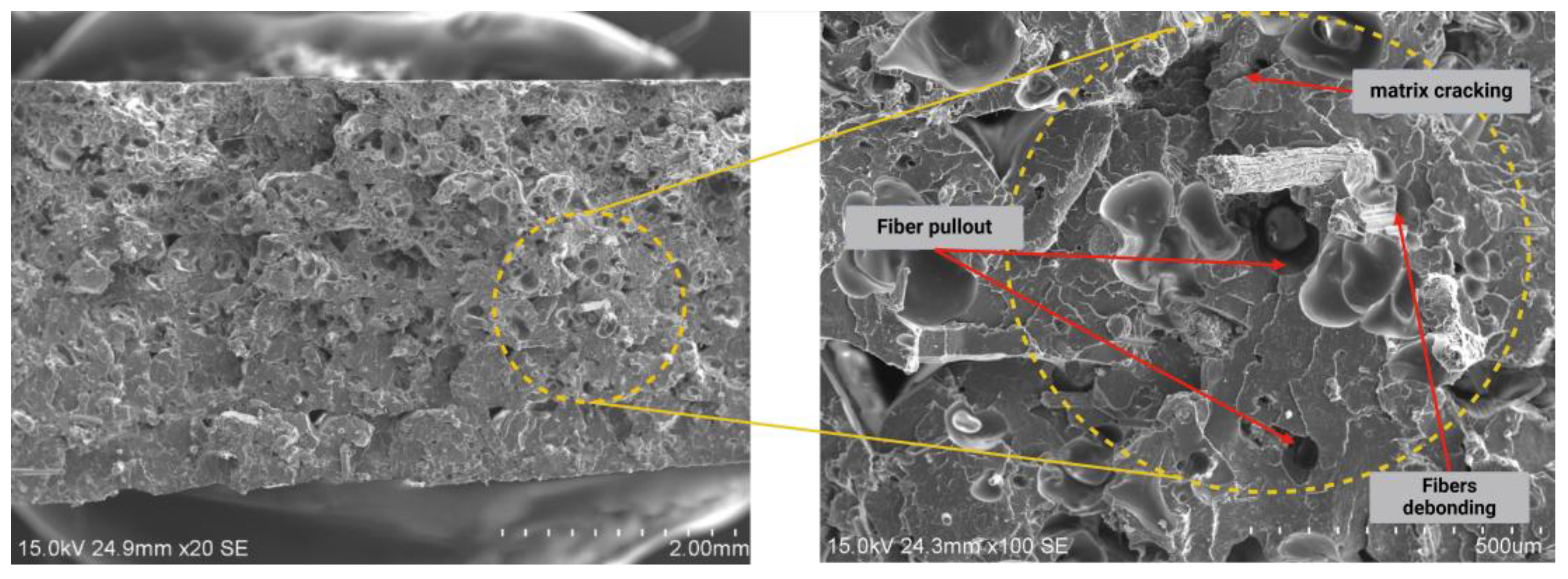

3.2.2. Classification of the Damage Modes Using K-Means Clustering

3.3. Prediction of Stress Levels in Tensile and Flexural Tests Using Machine Learning Models

3.3.1. Artificial Neural Network ANN

3.3.2. Random Forest Regression RFR

3.3.2.1. Feature Importance Analysis

3.3.2.2. Stress Level Prediction Using RFR

3.3.3. Decision Tree Regression DTR

3.3.3.1. Feature Importance

3.3.4. Support Vector Regression SVR

3.4. Comparative Performance Analysis of the Employed ML Models

4. Conclusions

- Cumulative Acoustic Emission Data: The cumulative acoustic emission energy provides critical insights into the damage evolution within the material during mechanical testing, serving as valuable indicators of structural integrity.

- The K-means model is used to classify damage modes, resulting in the identification of three main modes: matrix cracking, fiber debonding and pull-out.

- Machine Learning Model Performance: Four machine learning models with tuned hyperparameters were employed to estimate stress levels during tensile and flexural testing, using cumulative acoustic emission parameters. Among these, the RFR model delivered the most accurate predictions, outperforming the other models, followed by ANN, DTR, and SVR.

- Data Richness and Prediction Accuracy: The richness of the acoustic emission data contributed to superior predictive capabilities, particularly in the tensile test, as compared to the flexural test.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ayrilmis, N., et al., Effect of printing layer thickness on water absorption and mechanical properties of 3D-printed wood/PLA composite materials. The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, 2019. 102: p. 2195-2200. [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, M. Abenojar, and M.Á. Martínez, Recent progress in hybrid biocomposites: Mechanical properties, water absorption, and flame retardancy. Materials, 2020. 13(22): p. 5145. [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, A.K. Gupta, and H. Singh, PLA based biocomposites for sustainable products: A review. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research, 2023. 6(4): p. 382-395. [CrossRef]

- Le Duigou, A., et al., 3D printing of wood fibre biocomposites: From mechanical to actuation functionality. Materials & Design, 2016. 96: p. 106-114. [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, I., et al., Comparison between the mechanical properties and environmental impacts of 3D printed synthetic and bio-based composites. Procedia CIRP, 2022. 105: p. 380-385. [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., et al., Development and application of wood flour-filled polylactic acid composite filament for 3D printing. Materials, 2017. 10(4): p. 339. 339, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Guo, R., et al., Effect of toughening agents on the properties of poplar wood flour/poly (lactic acid) composites fabricated with Fused Deposition Modeling. European Polymer Journal, 2018. 107: p. 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Panasiuk, K. and K. Dudzik, Determining the stages of deformation and destruction of composite materials in a static tensile test by acoustic emission. Materials, 2022. 15(1): p. 313. [CrossRef]

- Barile, C., et al., Damage monitoring of carbon fibre reinforced polymer composites using acoustic emission technique and deep learning. Composite Structures, 2022. 292: p. 115629. [CrossRef]

- Huijer, A. Kassapoglou, and L. Pahlavan, Acoustic emission monitoring of carbon fibre reinforced composites with embedded sensors for in-situ damage identification. Sensors, 2021. 21(20): p. 6926. [CrossRef]

- Karami, S., et al., Investigation of the effect of nanoparticles on wood-bioplastic composite behavior using the acoustic emission method. Journal of Composite Materials, 2023. 57(1): p. 23-34. [CrossRef]

- Salje, E.K., et al., Acoustic emission spectroscopy: Applications in geomaterials and related materials. Applied Sciences, 2021. 11(19): p. 8801. [CrossRef]

- Hao, W., et al., Acoustic emission characterization of tensile damage in 3D braiding composite shafts. Polymer Testing, 2020. 81: p. 106176. [CrossRef]

- Ciaburro, G. and G. Iannace, Machine-learning-based methods for acoustic emission testing: A review. Applied Sciences, 2022. 12(20): p. 10476. [CrossRef]

- Habibi, M., et al., Combining short flax fiber mats and unidirectional flax yarns for composite applications: Effect of short flax fibers on biaxial mechanical properties and damage behaviour. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2017. 123: p. 165-178. [CrossRef]

- Saidane, E.H., et al., Damage mechanisms assessment of hybrid flax-glass fibre composites using acoustic emission. Composite Structures, 2017. 174: p. 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Sobhani, A., et al., The study of buckling and post-buckling behavior of laminated composites consisting multiple delaminations using acoustic emission. Thin-Walled Structures, 2018. 127: p. 145-156. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Malpot, A. Touchard, and S. Bergamo, An investigation of the influence of moisture on fatigue damage mechanisms in a woven glass-fibre-reinforced PA66 composite using acoustic emission and infrared thermography. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2017. 130: p. 11-20. [CrossRef]

- Roundi, W., et al., Acoustic emission monitoring of damage progression in glass/epoxy composites during static and fatigue tensile tests. Applied Acoustics, 2018. 132: p. 124-134. [CrossRef]

- Saeedifar, M. and D. Zarouchas, Damage characterization of laminated composites using acoustic emission: A review. Composites Part B: Engineering, 2020. 195: p. 108039. [CrossRef]

- Xu, D. Liu, and Z. Chen, A deep learning method for damage prognostics of fiber-reinforced composite laminates using acoustic emission. Engineering Fracture Mechanics, 2022. 259: p. 108139. [CrossRef]

- König, F., et al., Machine learning based anomaly detection and classification of acoustic emission events for wear monitoring in sliding bearing systems. Tribology International, 2021. 155: p. 106811. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W., Y. Zhang, and W. Zhao. Tensile Deformation Damage and Clustering Analysis of Acoustic Emission Signals in Three-Dimensional Woven Composites. in Advances in Acoustic Emission Technology: Proceedings of the World Conference on Acoustic Emission-2017. 2019. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Lu, D. and W. Yu, Predicting the tensile strength of single wool fibers using artificial neural network and multiple linear regression models based on acoustic emission. Textile Research Journal, 2021. 91(5-6): p. 533-542. [CrossRef]

- Sause, M.G. Schmitt, and S. Kalafat, Failure load prediction for fiber-reinforced composites based on acoustic emission. Composites Science and Technology, 2018. 164: p. 24-33. [CrossRef]

- SHIMAMOTO, Y., et al., Estimation of Concrete Mechanical Properties by Acoustic Emission with Random Forest Algorithm. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., et al., Acoustic emission characterization of natural fiber reinforced plastic composite machining using a random forest machine learning model. Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering, 2020. 142(3): p. 031003. [CrossRef]

- Ai, L., et al., Acoustic Emission-Based Detection of Impacts on Thermoplastic Aircraft Control Surfaces: A Preliminary Study. Applied Sciences, 2023. 13(11): p. 6573. [CrossRef]

- Properties, A.S.D.o.M. Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Plastics. 1998. American Society for Testing and Materials.

- Standard, A., Standard test methods for flexural properties of unreinforced and reinforced plastics and electrical insulating materials. ASTM D790. Annual book of ASTM standards, 1997.

- Ying, X. An overview of overfitting and its solutions. in Journal of physics: Conference series. 2019. IOP Publishing. 022022. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, D., et al. An information-theoretic perspective on overfitting and underfitting. in AI 2020: Advances in Artificial Intelligence: 33rd Australasian Joint Conference, AI 2020, Canberra, ACT, Australia, November 29–30, 2020, Proceedings 33. 2020. Springer. [CrossRef]

- Pothuganti, S., Review on over-fitting and under-fitting problems in Machine Learning and solutions. Int. J. Adv. Res. Electr. Electron. Instrum. Eng, 2018. 7: p. 3692-3695. [CrossRef]

- Barsoum, F.F., et al., ACOUSTIC EMISSION MONITORING AND FATIGUE LIFE PREDICTION IN AXIALLY LOADED NOTCHED STEEL SPECIMENS. 2009. 27.

- Benabderazag, K., et al., Characterization of thermomechanical properties and damage mechanisms using acoustic emission of Lygeum spartum PLA 3D-printed biocomposite with fused deposition modelling. 2024. 186: p. 108426. [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Z., et al., Evaluating explorative prediction power of machine learning algorithms for materials discovery using k-fold forward cross-validation. Computational Materials Science, 2020. 171: p. 109203. [CrossRef]

- Beyeler, M., Machine Learning for OpenCV. 2017: Packt Publishing Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Müller, A.C. and S. Guido, Introduction to machine learning with Python: a guide for data scientists. 2016: “ O’Reilly Media, Inc.”.

- Kaufman, L. and P.J. Rousseeuw, Finding groups in data: an introduction to cluster analysis. 2009: John Wiley & Sons.

- Djabali, A., et al., Fatigue damage evolution in thick composite laminates: Combination of X-ray tomography, acoustic emission and digital image correlation. Composites Science and Technology, 2019. 183: p. 107815. [CrossRef]

- Karsoliya, S., Approximating number of hidden layer neurons in multiple hidden layer BPNN architecture. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology, 2012. 3(6): p. 714-717.

- Li, P., et al., Analysis of acoustic emission energy from reinforced concrete sewage pipeline under full-scale loading test. Applied Sciences, 2022. 12(17): p. 8624. [CrossRef]

- Karthik, M. and C.S. Kumar, A comprehensive review on damage characterization in polymer composite laminates using acoustic emission monitoring. Russian Journal of Nondestructive Testing, 2022. 58(8): p. 705-721. [CrossRef]

- Han, S.N.M.F., et al., Investigation of tensile and flexural properties of kenaf fiber-reinforced acrylonitrile butadiene styrene composites fabricated by fused deposition modeling. Journal of Engineering and Applied Science, 2022. 69(1): p. 52. [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-L., et al., Ensemble learning approach for the prediction of quantitative rock damage using various acoustic emission parameters. Applied Sciences, 2021. 11(9): p. 4008. [CrossRef]

- Koya, B.P., et al., Comparative analysis of different machine learning algorithms to predict mechanical properties of concrete. Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, 2022. 29(25): p. 4032-4043. [CrossRef]

| Model | Hyperparameter | Optimized Value | Tuning range values |

|---|---|---|---|

| ANN | Model activation | tanh | [Relu, tanh] |

| Model optimizer | 0.01 | Adam, learning rate [0.001, 0.01] | |

| Batch_size | 32 | [16, 32] | |

| Epochs | 100 | [50, 100] | |

| RFR | Max depth | 7 | [5, 20] |

| Min samples leaf | 4 | [1, 10] | |

| Min samples split | 4 | [2, 10] | |

| n_estimators | 139 | [50, 200] | |

| Max features | auto | [auto, sqrt, log2] | |

| DTR | Max depth | 7 | [1, 20] |

| Min samples leaf | 5 | [1, 20] | |

| Min samples split | 4 | [2, 20] | |

| Max features | auto | [auto, sqrt, log2] | |

| SVR | kernel | rbf | [linear, rbf] |

| C | 10 | [1, 1000] | |

| gamma | 1 | [0.1, 1, scale] | |

| epsilon | 0.2 | [0.01, 0.1, 0.2] |

| Tensile test | flexural test | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | MSE | RMSE | R2 | Average 5 CV R2 |

MSE | RMSE | R2 | Average 5 CV R2 |

|

| ANN | 0.0189 | 0.1375 | 0.9757 | 0.9727 | 0.6490 | 0.8056 | 0.9681 | 0.9575 | |

| RFR | 0.0139 | 0.1179 | 0.9822 | 0.9801 | 0.3792 | 0.6158 | 0.9813 | 0.9806 | |

| DT | 0.0271 | 0.1648 | 0.9652 | 0.9617 | 0.6480 | 0.8050 | 0.9681 | 0.9659 | |

| SVR | 0.0435 | 0.2087 | 0.9442 | 0.9526 | 0.4411 | 0.6641 | 0.9683 | 0.9671 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).