1. Introduction

With SSI, a hacker creates a chain of compromised hosts (stepping-stone hosts), employs the tool ssh to login to each of the stepping-stone hosts in the chain, and then sends the attacking commands to the victim host [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

Figure 1 shows a sample of a connection chain with 5 connections. In this figure, host A is the attack host, whereas the host V serves as the victim host. In turn, the attacker remotely logins to the stepping-stone hosts S1, S2, S3, S4, and eventually to the victim. To perform SSID, any stepping-stone host between the attacker A and the victim host V can be used as the sensor host to capture network packets using certain tools such as tcpdump or Wireshark. Assume that host S2 is selected as the sensor host. The connections from the intruder A to host S1, and then to the sensor S2 form the upstream sub-chain, whereas the connections from S2 to host S3, to host S4, and finally to the victim V form the downstream sub-chain.

The goal to detect SSI is to decide whether a stepping-stone host is used by an attacker for a network intrusion [1[

2,

3]. The session is a network intrusion detected at the sensor host if an ingress connection to the sensor matches one of its outbound connections from the sensor. With stepping-stone intrusion, it is extremely tough to detect the intruder as it is hidden behind a long communication session [

9]. The hardness for the final victim host V to obtain information about the origin of the attack has been well-documented in the literature of this area.

Nowadays, attackers often send hacking commands using some techniques such as chaff-perturbation to manipulate the communication session. That is, injecting some meaningless packets into a TCP data stream. The purpose to do so is to decrease the probability of being caught. SSI with chaff-perturbation is also referred to as a chaff-attack. Through a chaff attack, intruders cannot only revise the packets round-trip times (RTTs), but also change the packet count for sent from the attacker host to the victim. With chaff attacks, most of the existing detection approaches for SSI may be defeated by hackers. Today, chaff attacking techniques have been widely used in various cyberattacks.

A widely used type of detection methods for SSI is to find if an outbound connection departing from the sensor matches with an ingress connection into the sensor [

1,

2]. If yes, it is highly suspicious that the sensor host is used as a stepping-stone host. With this type of SSID approach, all the network packets are captured and analyzed only at the selected sensor host, thus is called the host-based SSID [

9].

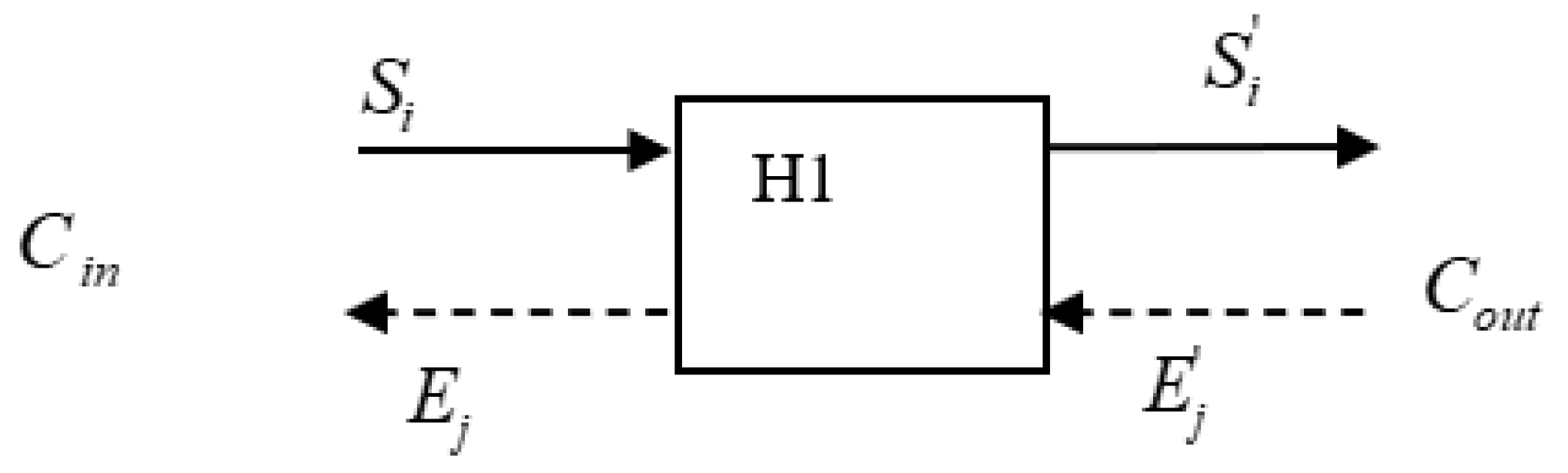

Figure 2 below shows a scenario to decide if the host H1 is used as a stepping-stone one. The basic idea here is that if host H1 is used as a stepping-stone host, some other host must be under attack presumably via host H1, although this detection method may bring false positive errors.

In

Figure 2, H1 is the sensor host. This figure shows a scenario that

Cin is an incoming connection from its upstream hosts (up to the attacker machine), and

Cout is an outgoing connection which goes to its downstream hosts until to the victim machine. If

Cin and

Cout are proved to be a relayed pair of connections, then host H1 is used as a stepping-stone. In the incoming connection

Cin, there are two streams:

Si and

Ej, where

Si represents the request packets stream which is also called Send packets from the attacker to the victim, whereas

Ej represents the response packets stream which is also called Echo packets from the victim back to the attacker host. Similarly, the two streams

and

are obtained from the outgoing connection

Cout.

Many such methods for SSI have been proposed in the literature. If the network traffic is not encrypted, we can simply compare the packet contents from incoming and outgoing connections of a host. If the network traffic is encrypted, comparing packet timestamp gap is another approach to detect stepping-stone hosts. If both the number of the ingress packets into the sensor, and that of the outbound packets from a host can be counted, it is straightforward to make a conclusion that if a machine is used as a stepping-stone by simply comparing the two numbers of ingress and outbound packet counts. More details of these host-based detection methods will be reviewed and discussed in the next section. Most of these known host-based detection algorithms for SSI only worked effectively for the network traffic without intruders’ session manipulation. When session manipulation such as chaff perturbation or time jittering by intruders is present, these known hosted-based SSID algorithms are either weak to resist intruders’ manipulation or having very limited capability in resisting attacker’s manipulation.

This paper develops an innovative host-based algorithm for SSID that is effective to detect SSI and resistant to intruders’ chaff-perturbation through matching TCP packets by using packet crossover. Our proposed detection algorithm can be simply implemented as the ratios of packet crossover used in this paper could be quickly computed. Well-designed network experiments are conducted to verify the correctness of the proposed method for SSI. The experimental results we obtained exhibit that the proposed approach for SSI in this paper works in resisting intruders’ chaff-attacks effectively.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows: Related work of the paper is presented in

Section 2. Preliminary knowledge of basic concepts is given in

Section 3. In

Section 4, we give an effective SSID algorithm to determine whether a host is used as a step-ping-stone for network traffic with chaffed meaningless packets via using the occurrences of packet crossover. In

Section 5, we design and conduct network experiments to verify the correctness of Proposition 1 which is a theoretical basis of the proposed SSID algorithm.

Section 6 concludes the paper as well as give some discussion of future research directions in the SSID area.

2. Related Work

This section discusses the related work of SSID approaches. The review focuses on the known host-based SSID approaches that determine whether the sensor host is used as a stepping-stone one for malicious intrusion. The easiest way to verify whether the two connections

Cin and

Cout of host H1 shown in

Figure 1 are relayed is to compare the actual content of the network packets from the two connections. The idea of examining packet contents in a connection to determine whether a host is used as a stepping-stone was proposed by S. Staniford-Chen, and L. T. Heberlein [

1] in 1995. The work [

1] is the first paper in this area for unencrypted network traffic. The conclusion of [

1] stated that if there is such a relayed pair of connections, the sensor host is used as a stepping-stone. The detection algorithm proposed in [

1] is easy to implement, and also quite efficient. The primary issue for content thumbprint is that it is hard to get packets’ contents if the connection is established using encrypted tools, such as SSH or OpenSSH. Thus, this method to detect SSI based on packet contents can be easily defeated by establishing an encrypted session.

Time thumbprint is an approach proposed by Y. Zhang, and V. Paxson [

2] in 2000 to detect SSI when the network traffic is encrypted. Time thumbprint approach can overcome the difficulty existing in content thumbprint. The main reason is that, instead of using packet content, this approach uses timestamp of each captured packet to define time thumbprint. Since timestamp of each packet is not encrypted, and also only relies on the local host system time clock, so this approach is not only stable and reliable, but also cannot be affected by clock skew issue. Thus, the thumbprint SSID approach developed in [

2] works for network traffic that is encrypted.

K. Yoda et al proposed another in [

8] another detection method for SSI using the idea of investigating the deviation for two consecutive connections of the same connection chain. The content of network packets were not used for the design and analysis of this approach, and thus the approach proposed in [

8] is working for encrypted network traffic.

The use of encrypted sessions by intruders make SSID much more complicated, and the intruder’s active timing perturbation and injection of chaff packets by attackers make the SSI detection process even more difficult. The use of packet count was proposed in [

4] and [

5] by T. He et al to handle such SSID challenges. The paper [

5] is the extended version of the paper [

4]. These two papers proposed strategies to identify stepping-stone connections when the network traffic is encrypted, and the timestamps of packets are perturbed, or chaff packets are injected into an attacking stream. Two activity-based algorithms are proposed to detect stepping-stone connections respectively with either bounded memory or bounded delay perturbation. A. Blum et al. proposed another detection method for network intrusion via using the idea to count respectively the number of network packets in the ingress connection as well as the outbound connection. [

6] made a conclusion that the difference between these two numbers is less than a constant number if such a pair of connections are relayed ones.

Research findings [

3] obtained by D. L. Donoho et al. show that intruders’ capabilities of manipulating communication sessions are limited, and they won’t be able to evade detection by camouflaging the communication sessions.

In one of our recent research publications [

10], we developed an effective host-based detection method for SSI by using packet crossover for network traffic without chaffed meaningless packets. By determining how many connections are contained in a connection chain, in [

11] we used packet crossover for network traffic with chaffed meaningless packets to develop a method for detecting network intrusion. This SSID method works effectively in resisting chaff attack manipulated by attackers.

3. Preliminaries

This section discusses some basic concepts that will be used in the design of our proposed SSID algorithm in this paper.

3.1. A Matched Pair of a Send Packet and its Corresponding Echo

Send packets and their corresponding echoes are clearly descripted in [

9,

10]. Let us use an example to review these basic concepts. Assume that the Linux command “ps” is typed on a terminal in the attacker machine (refers to

Figure 1). The command “ps” could be sent to the victim host in one or two packets. For simplicity, it is assumed that the command with two separate TCP packets are sent to the victim host: one packet with the letter “p” and the other with the letter “s”. Both are Send packets because they are sent from the attacker host to the victim. After “p” is typed on the attacker host, the packet with “p” is sent to the remote victim machine. Once it arrives at the victim host, a corresponding Echo packet is then delivered back to the attacker host. As a result, its screen displays the letter “p”. In this example, the Send packet with “p” and the corresponding Echo one are a matched pair of packets. Similarly, a Send packet with “s” and its corresponding Echo one holding “s” are also a matched pair.

3.2. Crossover of Packets

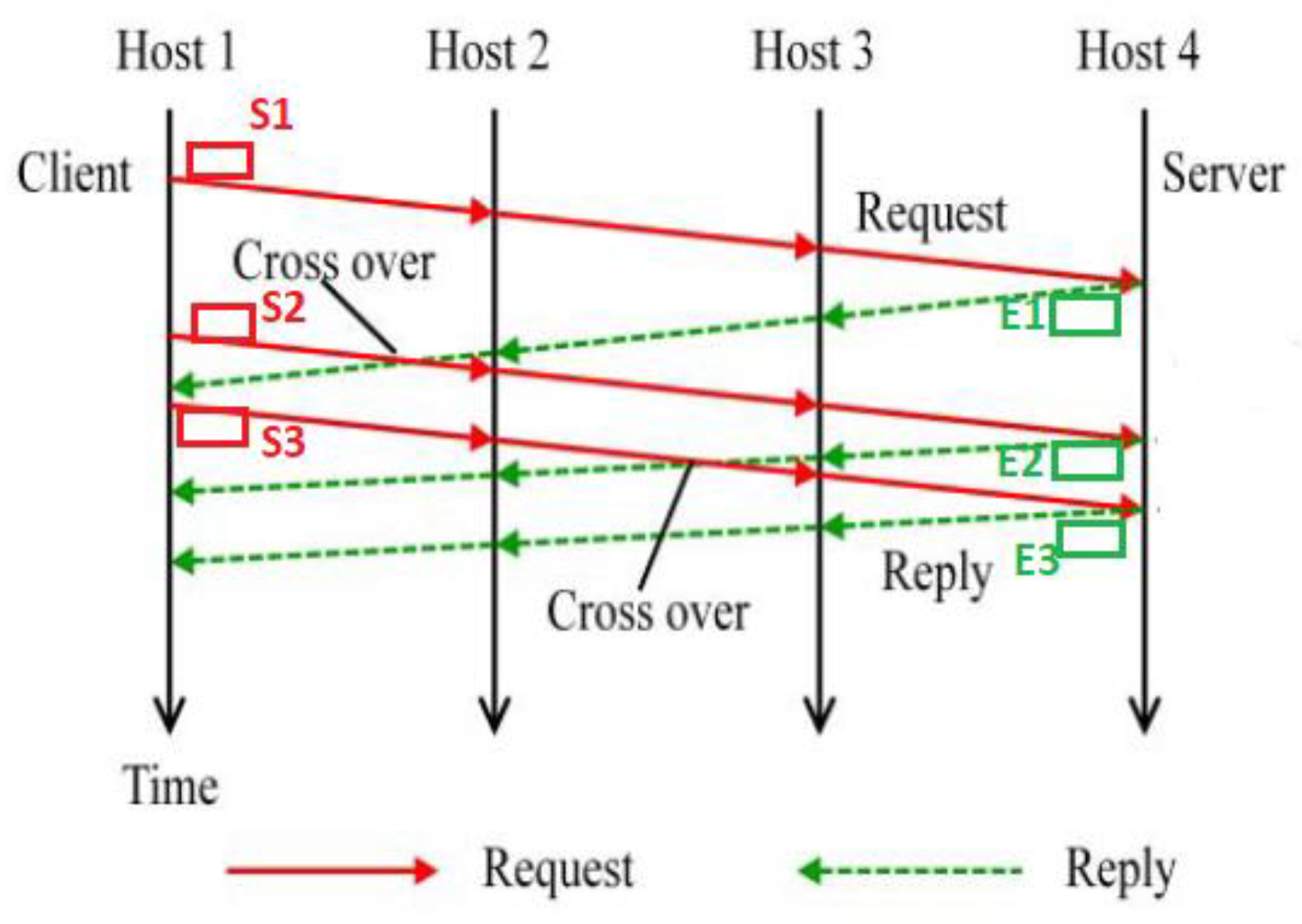

TCP allows a client host to send pipelined request (Send) packets to a remote server. Packet crossover occurs when a newly Send packet meets the corresponding Echo packet of a previous Send one before the Echo arrives at the Host 1 (see

Figure 3) [

7]. In

Figure 3, four hosts, the client (Host 1), Host 2, Host 3, and the server (Host 4) are involved in a connection chain, where both hosts 2 and 3 are stepping-stone hosts in this chain. The packets S1, S2 and S3 (marked red) and are the Send packets, and the packets E1, E2, and E3 (marked green) are their corresponding Echo packets. Assume that Host 2 serves as the sensor host to capture all the packets, then the Send and their corresponding Echo packets from the connection between Host 2 and Host 3 are captured and analyzed. The sequence of these six packets monitored at the sensor is respectively S1, E1, S2, S3, E2, and E3. Thus, one occurrence of packet crossover is observed in this case, which is the one occurred between Host 2 and Host 3, caused by the two packet S3 and E2.

4. Matching Packets Using Packet Crossover for Network Traffic with Chaff

In this section, we give a proposition which is a theoretical basis for our detection algorithm design. Then we present an effective SSID algorithm to determine whether a host is used as a stepping-stone for network traffic with chaffed meaningless packets using the ratios of packet crossover.

Proposition 1: Assume that both an incoming connection and an outgoing connection of the sensor host contain chaffed meaningless packets. We claim that these two connections of the sensor are a relayed pair if the ratio of packet crossover for the incoming connection is almost equal to that of the outgoing connection. In such a case, it is highly suspicious that the sensor host is used as a stepping-stone one.

This proposition will be verified through several well-designed network experiments conducted in the environment of the Internet in

Section 6.

Next, we adopt the host-based SSID algorithm using packet crossover proposed in [

10]:

1). Pick a host of a network as the sensor host.

2). Adopt Algorithm 1 (Compute Packet Crossover Ratio) in [

9] to calculate the packet crossover ratio for every incoming connection to the above sensor host.

3). Adopt Algorithm 1 (Compute Packet Crossover Ratio) in [

9] to calculate the packet crossover ratio for every outgoing connection from the above sensor host.

4). If any of the packet crossover ratios calculated for an incoming connection at Step 2) is almost the same as one of the packet crossover ratios calculated for an outgoing connection at Step 3), then it is highly suspicious that these two connections are a relayed pair, and thus the sensor host is used as a stepping-stone one.

5). If none of the packet crossover ratios calculated at Step 2) for incoming connections is close to any of the packet crossover ratios calculated for outgoing connections at Step 3), then it is almost sure that the sensor is not used as a stepping-stone host.

Theoretically, the correctness of our detection algorithm for SSI listed above is clearly asserted based on Proposition 1. Our experimental results presented in

Section 6 exhibit that the proposed detection approach against SSI in this paper works effectively in resisting chaff attacks manipulated by hackers.

5. Network Experimental Results and Analysis

In this section, we design and implement network experiments to verify the correctness of Proposition 1 described in

Section 4 by comparing the packet crossover ratios of incoming and outgoing connections. Relayed pairs typically results in almost equal packet crossover ratios. On the other hand, non-relayed pairs of connections typically results in dissimilar packet crossover ratios.

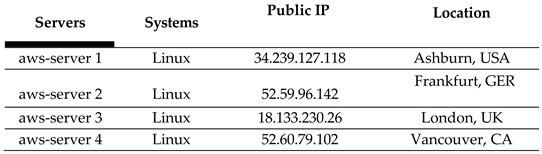

To set up our experimental environment, we create a connection from a local computer (localhost-1) in our computer lab at Columbus State University (GA, USA) to four remote Amazon AWS servers, aws-servers 1 through 4, and then connected back to another local host (localhost-2) in the same computer lab in our university. A chain of five connection was created from the attacker host localhost-1 to the victim host localhost-2 through the four stepping-stones: aws-servers 1 through 4. Linux was running in each of these 6 hosts having both SSH client and server installed in each host. We used the tool tcpdump to capture all the network packets at the sensor host.

The corresponding actual geographic locations and their corresponding public IP addresses of the four AWS servers (aws-servers 1 through 4) are listed in

Table 1. AWS2 will serve as the sensor host, and both the incoming packets to AWS2 and the outgoing packets from AWS2 will be monitored and captured at the sensor host.

After the connection chain was established, both the incoming and outgoing connections of the sensor host AWS2 will be monitored, and the packets will be captured using the tcpdump tool running at the sensor host AWS2.

In the 1st experiment we conducted, network traffic without meaningless packets chaffed was captured and analyzed. With this experiment, we first entered the following Attacker 1 script of standard Linux commands for about 3 minutes into a terminal on the attacker localhost-1 and captured all packets from the indicated connections at the sensor AWS2:

// Attacker 1 script

pwd

whoami

sudo su

ls

cd /etc

ls −a

scp −p shadow attacker username@attacker IP:/home/seed/Documents

exit

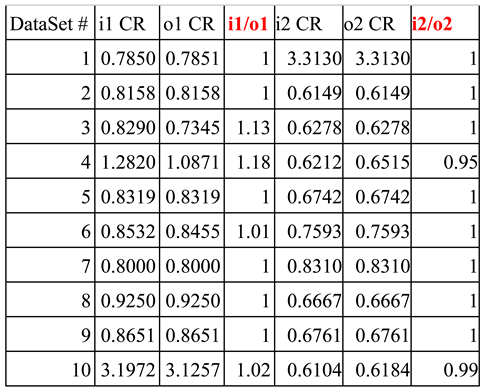

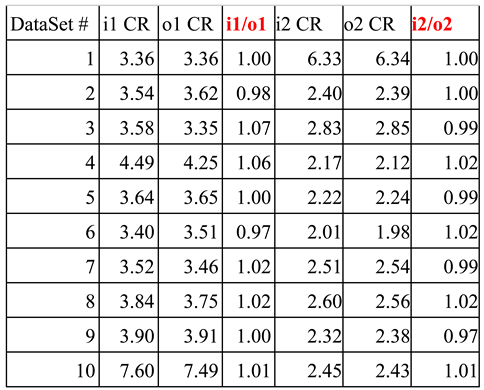

We captured 10 datasets in total, with each data set comprising two files (one for the incoming connection and the other one for the outgoing connection) at the sensor host AWS2. After capturing all the data, we ran our Packet Crossover Ratio algorithm to calculate the packet crossover ratio observed at the sensor AWS2 from the incoming connection represented by

i1 for the above script. In

Table 2, CR stands for Crossover Ratio. Column 1 of

Table 2 lists the numbers of dataset. Column 2 of

Table 2 lists the Crossover Ratio (CR) of the incoming connection

i1 for each dataset. Then we ran the Packet Crossover Ratio algorithm to calculate the packet crossover ratio observed at the sensor AWS2 from the corresponding outgoing connection represented by

o1. Column 3 of

Table 2 lists the Crossover Ratio (CR) of the outgoing connection

o1 for each dataset.

Next, we entered the following Attacker 2 script of standard Linux commands different from Attacker 1 for about 3 minutes into a terminal at the attacker localhost-1 and captured all packets from the indicated connections at the sensor host AWS2:

// Attacker 2 script

whoami

pwd

cd /home/seed/Documents

ls

nano text_file.txt

//paste a large text and save it

ls

cat hello.txt

exit

We also captured 10 datasets in total for Attacker 2 script, with each data set comprising two files (one for incoming connection and the other one for outgoing connection) at the sensor host AWS2. After capturing all the data, we ran our Packet Crossover Ratio algorithm to calculate the packet crossover ratio observed at the sensor AWS2 from the incoming connection represented by

i2 for the above script. Column 5 of

Table 2 lists the Crossover Ratio (CR) of the incoming connection

i2 for each dataset. Then we ran the Packet Crossover Ratio algorithm to calculate the packet crossover ratio observed at the sensor AWS2 from the corresponding outgoing connection represented by

o2. Column 6 of

Table 2 lists the Crossover Ratio (CR) of the outgoing connection

o2 for each dataset.

We then use the packet crossover ratios we obtained to match the incoming and outgoing connections. Based on Proposition 1 above, the packet crossover ratios captured at a given sensor for the incoming and outgoing connections of a relayed pair should be close to 1. Therefore, we expected to see a matching of close to 1 for ratio i1/o1 in Column 4 of

Table 2, as well as the ratio i2/o2 close to 1 in Column 7 of

Table 2. Moreover, we expected to see from this table a matching not close to 1 for non-relayed connection pairs such as i1 and o2 (or i2 and o1). This table compares the CR of i1 to its respective outgoing connection o1. CR’s of relayed pairs should be very similar. Therefore, the incoming connection’s CR divided by the outgoing connection’s CR should and does equal approx. 1 in Columns 4 and 7 of

Table 2.

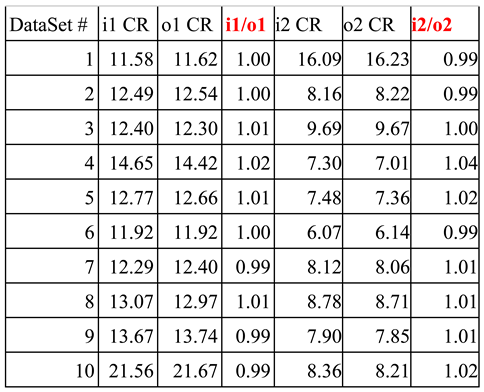

In the 2

nd experiment we conducted, network traffic with meaningless packets chaffed at a rate of

10% was captured and analyzed. We performed all the same steps as we did for the 1

st experiment above for network traffic without chaffed packets. Respectively, we entered the scripts of Attacker 1 and Attacker 2 for about 3 minutes for each script into a terminal on the attacker localhost-1 and captured all packets from the indicated connections at the sensor AWS2. Similarly, the same Packet Crossover Ratio algorithm was employed to compute the packet crossover ratio using the captured packets with

10% chaff rate at the sensor host. The results we obtained for the 2

nd experiment are listed in

Table 3 below, which is very similar to the results we obtained for the 1

st experiment without meaningless packets chaffed (refers to

Table 2).

In the 3

rd experiment we conducted, network traffic with meaningless packets chaffed at a rate of

50% was captured and analyzed. We performed all the same steps as we did for the 1

st experiment above for network traffic without chaffed packets. Respectively, we entered the scripts of Attacker 1 and Attacker 2 for about 3 minutes for each script into a terminal on the attacker localhost-1 and captured all packets from the indicated connections at the sensor AWS2. Similarly, the same Packet Crossover Ratio algorithm was employed to compute the packet crossover ratio using the captured packets with

50% chaff rate at the sensor host. The results we obtained for this experiment are listed in

Table 4 below, which is also very similar to the results we obtained for the 1

st experiment without meaningless packets chaffed (refers to

Table 2).

6. Conclusion and Future Work

In this paper, we developed a host-based approach to detect SSI using packet crossover. Our proposed method for detecting SSI resists to chaff attackers manipulated by hackers as well as works effectively to detect network intrusion. Most existing algorithms to detect SSI are either weak to resist chaff attacks manipulated by hackers or having very limited capability in resisting attacker’s session manipulation. The detection approach for SSI proposed in this paper can be simply and quickly implemented as computing the ratios of the packet crossovers is straightforward. The results we obtained from the well-designed network experiments exhibit that our proposed algorithm for detecting SSI performs perfectly in resisting chaff attacks manipulated by hackers up to 50% chaff rate.

By far, in all the known works that address intruders’ chaff manipulation, it is assumed that the incoming and outgoing connections of only one host (the sensor) can be chaffed with meaningless packets. For future research direction related to SSID, detection algorithms for SSI that are resistant to chaff attacks if meaningless packets are chaffed by intruders into the egress and ingress connections of two or more machines in a connection chain.

Author Contributions

Dr. L. Wang: SSID design, paper writing, data analysis, supervision of students, and project administration; Dr. J. Yang: validation of results, data analysis, investigation, and supervision of students; Mr. K. Mphande: set up the environment for network experiments, collect and analyze network packets; Dr. Y. Zhou: help analyze the data and the algorithm validation. All authors have read and agreed to the current version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work of Drs. Lixin Wang and Jianhua Yang is supported by the National Security Agency NCAE-C Research Grant (H98230-20-1-0293) with Columbus State University, Georgia, USA.

Data Availability Statement

N/A.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- S. Staniford-Chen, and L. T. Heberlein, “Holding Intruders Accountable on the Internet,” Proc. IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, Oakland, CA, 39-49, 1995. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhang, and V. Paxson, “Detecting Stepping-Stones,” Proc. of the 9th USENIX Security Symposium, Denver, CO, 67-81, August 2000.

- D. Donoho, A. Flesia, U. Shankar, V. Paxson, J. Coit, and S. Staniford, “Multiscale stepping-stone detection: Detecting pairs of jittered interactive streams by exploiting maximum tolerable delay,” in 5th International Symposium on Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2516, 2002. [CrossRef]

- T. He and L. Tong, “Detecting Stepping-stone Traffic in Chaff: Fundamental Limits and Robust Algorithms,” the 9th International Symposium on Recent Advances in Intrusion Detection (RAID 2006), April 2006.

- T. He, L. Tong, “Detecting encrypted stepping-stone connections,” In: Proceedings of IEEE Transaction on signal processing, 55(5), 1612-1623, 2007. [CrossRef]

- A. Blum, D. Song, And S. Venkataraman, “Detection of Interactive Stepping-Stones: Algorithms and Confidence Bounds”, Proceedings of International Symposium on Recent Advance in Intrusion Detection (RAID), Sophia Antipolis, France, 20-35, September 2004. [CrossRef]

- S. S.-H Huang, H. Zhang, and M. Phay, “Detecting Stepping-stone intruders by identifying crossover packets in SSH connections”, the Proceedings of 30th IEEE International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications, Fukuoka, Japan, 1043-1050, March 2016. [CrossRef]

- Yoda, K.; Etoh, H. Finding Connection Chain for Tracing Intruders. In Proceedings of the 6th European Symposium on Research in Computer Security, Toulouse, France, 4–6 October 2000; Volume 1985, pp. 31–42.

- L. Wang, J. Yang, and A. Lee, “An Effective Approach for Stepping-Stone Intrusion Detection Using Packet Crossover,” the 377 23rd World Conference on Information Security Applications (WISA), August 24-26, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Wang, J. Yang, A. Lee, and P.-J. Wan: Matching TCP Packets to Detect Stepping-Stone Intrusion using Packet Crossover, Advances in Science, Technology and Engineering Systems Journal, Vol. 7, No. 6 (Nov. 2022).

- L. Wang, J. Yang, J. Kim, and P.-J. Wan: An Effective Approach for Stepping-stone Intrusion Detection Resistant to Intruders’ Chaff-Perturbation via Packet Crossover, MDPI Electronics, Vol. 12, No. 3855 (Sept. 2023).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).