Submitted:

28 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

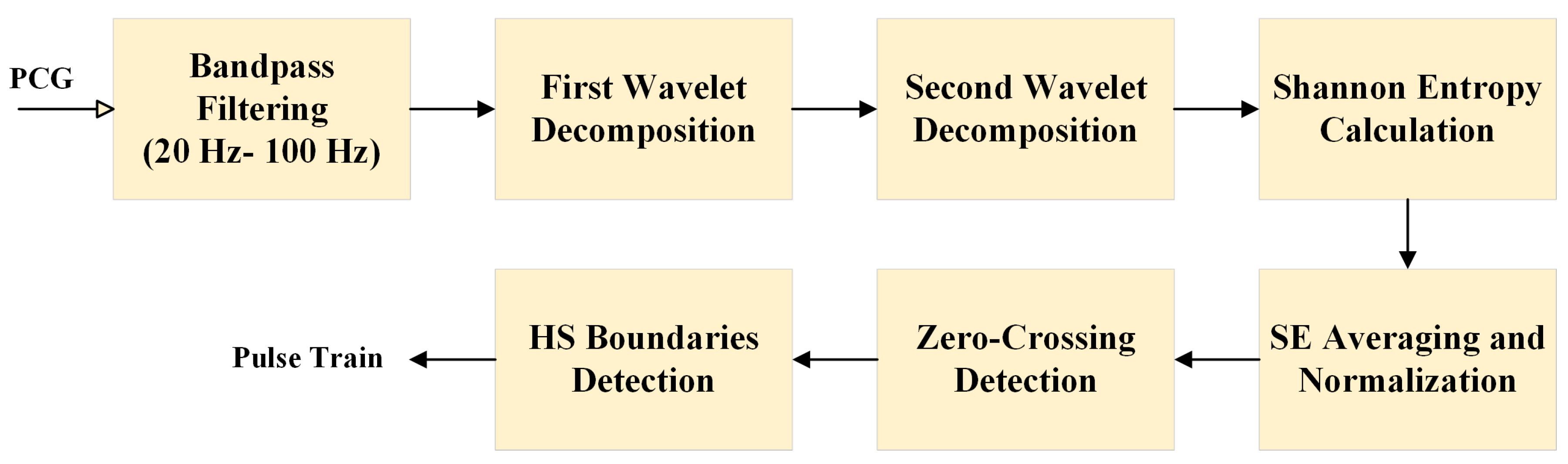

2.1. Feature Extraction

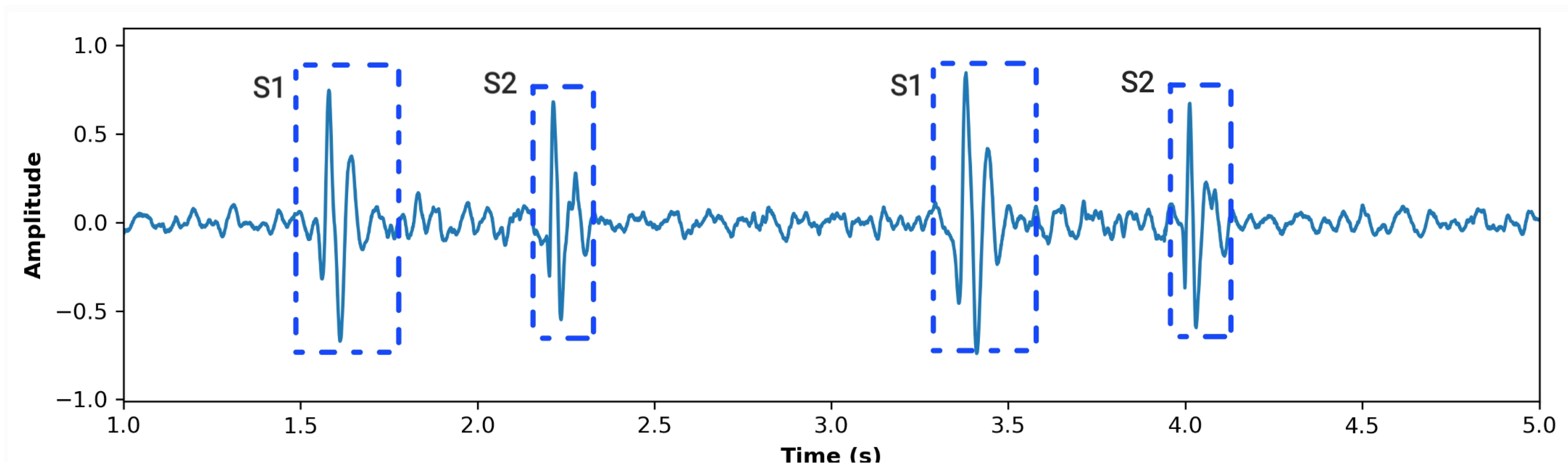

2.1.1. Signal Preprocessing

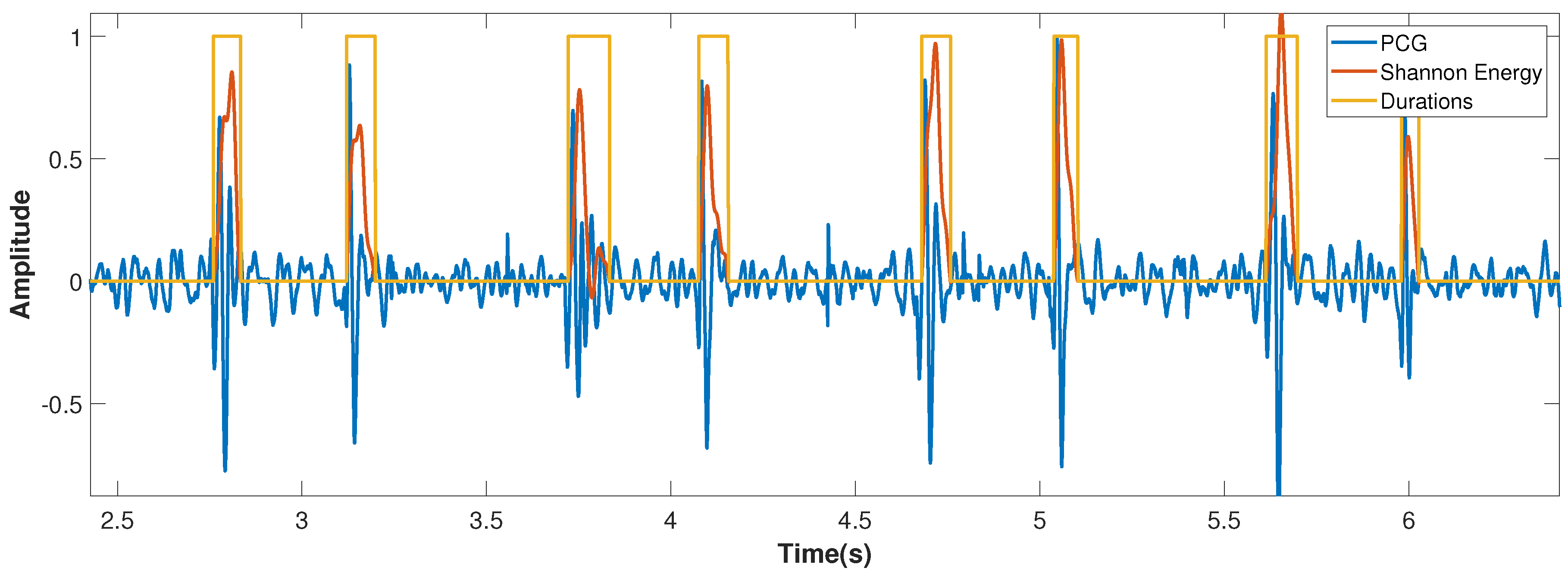

2.1.2. Shannon Energy Calculation

2.1.3. Segmentation Using Zero-Crossing Detection

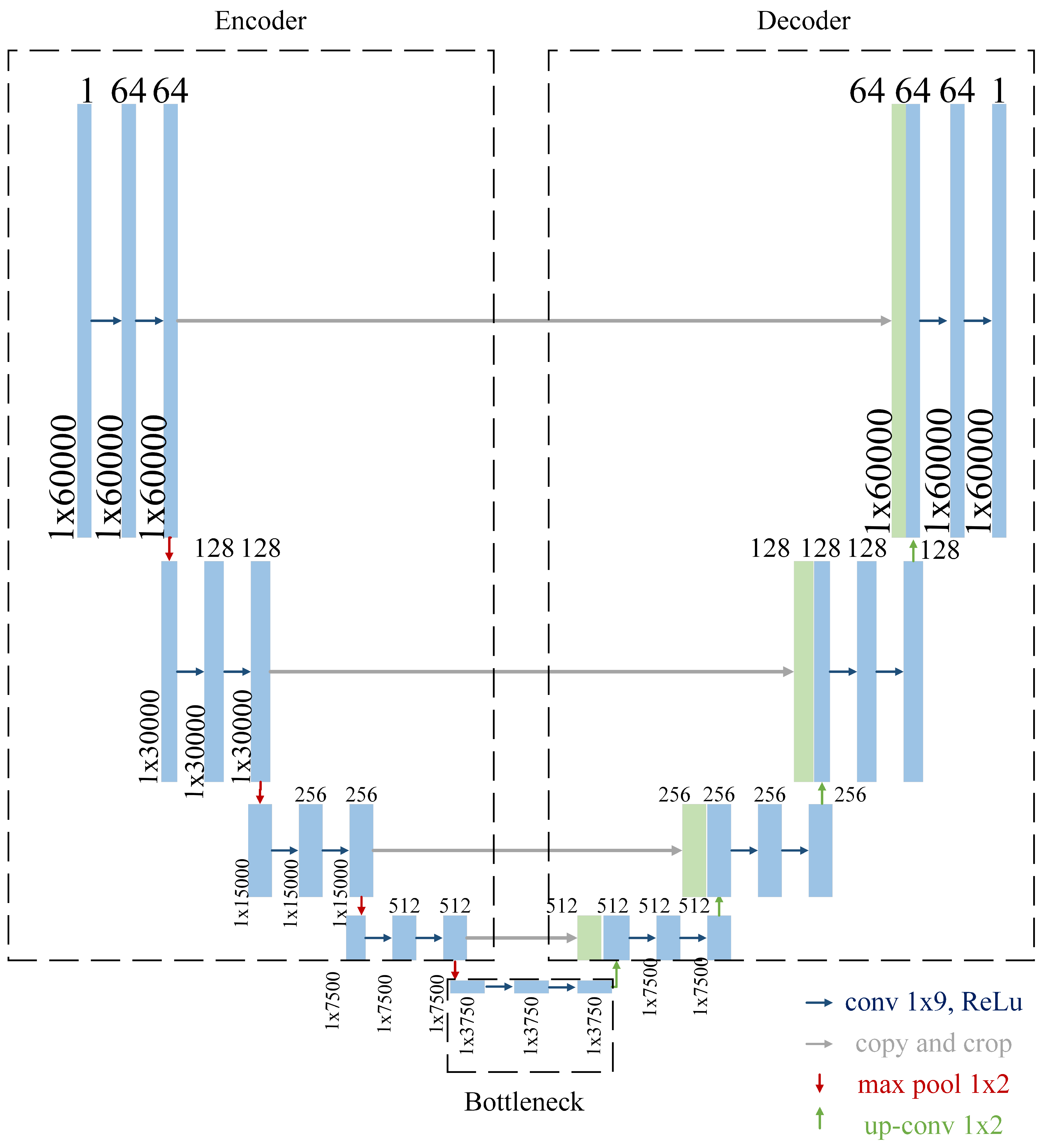

2.2. Convolutional Neural Network

2.2.1. Encoder

- Convolutional Layers: The convolutional layers are configured with a kernel size of 9 and a padding value of 4 to ensure that the temporal resolution of the input signal is preserved throughout the encoding process. This configuration helps capture local patterns within the signal, such as rapid transitions or subtle variations in heart sounds.

- Number of Filters: The number of filters begins at 64 in the first block and doubles with each subsequent block, reaching a maximum of 1024 filters at the bottleneck. This progressive increase allows the network to capture features at multiple levels of abstraction, from basic waveforms to more complex signal characteristics.

- Max-Pooling: Max-pooling operations are used to downsample the signal, reducing its resolution and allowing the network to focus on the most salient features. This operation also reduces computational complexity, making the model more efficient.

2.2.2. Bottleneck

2.2.3. Decoder

- Transposed Convolutions: Upsampling is performed using transposed convolutions, which increase the resolution of the feature maps while learning how to optimally reconstruct the signal.

- Skip Connections: At each stage, the decoder concatenates the upsampled features with the features from the corresponding encoder block. This mechanism allows the network to leverage both high-level and low-level information, improving the accuracy of the segmentation.

- Decreasing Filters: The number of filters decreases progressively, starting from 1024 in the bottleneck and halving with each subsequent block until it reaches 64 in the final decoder layer. This ensures that the reconstructed signal matches the original input dimensions.

- Final Layer: The final layer consists of a single convolutional layer that reduces the output to a single channel, followed by a sigmoid activation function. This produces a binary segmentation map, where each point represents the likelihood of a heart sound event.

2.2.4. Forward Propagation

- Encoder Phase: The input PCG signal is processed through the encoder, where features at various levels of abstraction are extracted. The use of downsampling ensures that the network captures both the local and global context of the signal.

- Bottleneck Phase: The processed signal is passed through the bottleneck, where the most salient features are learned. This phase acts as the "compression" stage, reducing noise and focusing on the core information necessary for segmentation.

- Decoder Phase: The signal is then reconstructed in the decoder, where skip connections ensure that fine-grained details are incorporated. At this point, a sigmoid activation signal is used to finally generate a binary PCG segmentation map that highlights the locations of heart sounds within the PCG signal.

2.2.5. Advantages of the U-Net Architecture for Heart Sound Segmentation

2.3. CNN Training Parameters

- Loss Function: The binary cross-entropy loss function was employed, as it is well-suited for binary classification tasks such as this, where the goal is to segment heart sound events from the PCG signal.

- Learning Rate: A learning rate of 0.0001 was chosen to ensure stable convergence during training. This small learning rate helps avoid large updates to the model weights, reducing the risk of overshooting the optimal solution and ensuring smooth optimization.

- Optimizer: The Adam optimizer was used for training. Adam combines the benefits of adaptive learning rates and momentum, making it effective for handling noisy gradients and sparse updates, both of which are common in segmentation tasks involving physiological signals.

- Epochs and Batch Size: The model was trained for 100 epochs with a batch size of 4. The small batch size was chosen to accommodate the high dimensionality of the PCG signals and the computational constraints, while the 100 epochs allowed the model to learn and generalize effectively without overfitting.

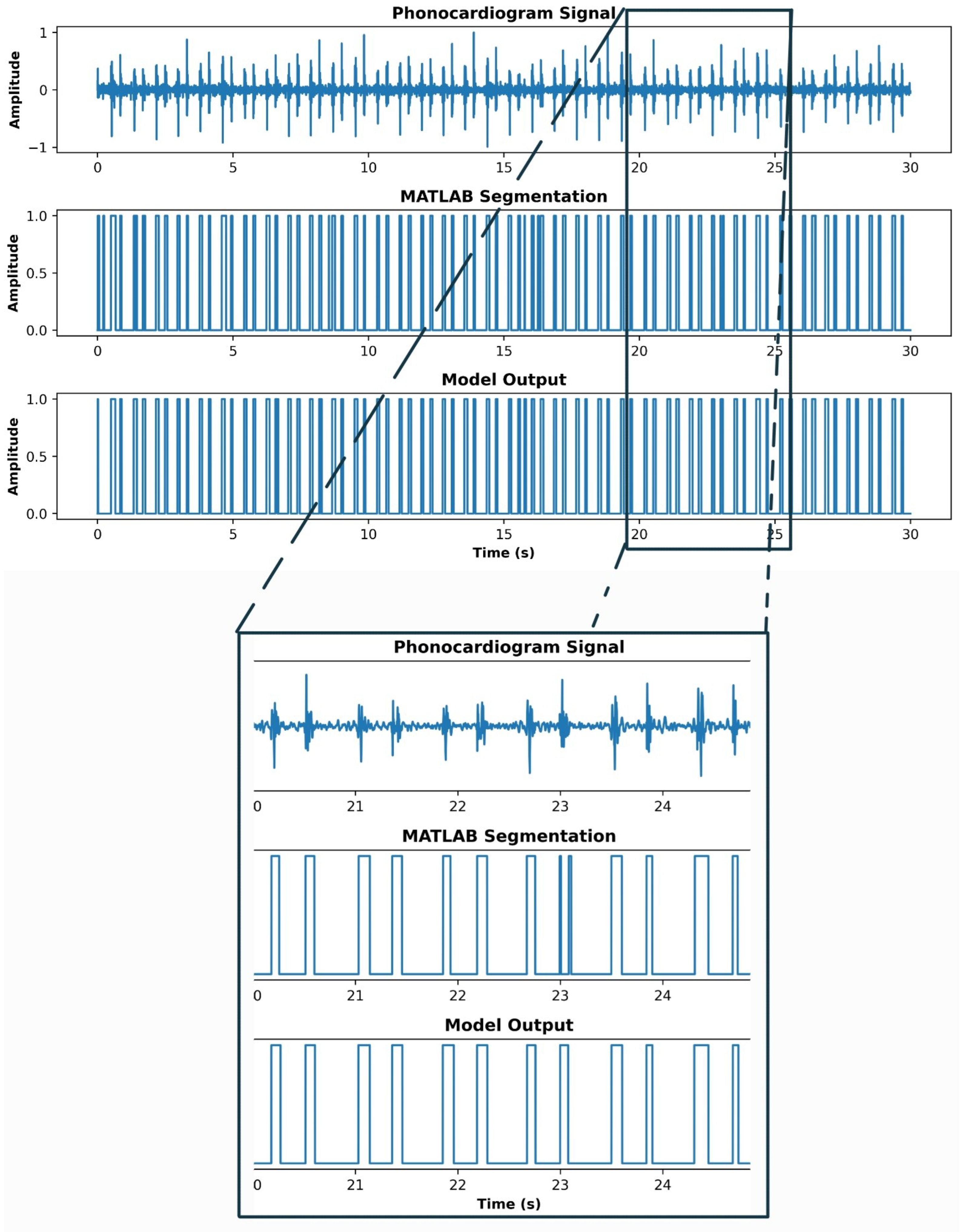

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Abbreviations

| PCG | Phonocardiogram |

| HS | Heart Sounds |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

References

- British Heart Foundation. Global Heart & Circulatory Diseases Factsheet. British Heart Foundation, London, UK, 2024. Published September 2024. Accessed January 3, 2025.

- World Heart Federation. World Heart Report 2023: Driving change for cardiovascular health. World Heart Federation, Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. Accessed 21/11/24.

- Chakrabarti, T.; Saha, S.; Roy, S.; Chel, I. Phonocardiogram Signal Analysis – Practices, Trends and Challenges: A Critical Review. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the International Conference on Signal Processing, Informatics, Communication and Energy Systems (SPICES), Kolkata, India, 2015; pp. 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Phua, K.; Chen, J.; Dat, T.H.; Shue, L. Heart Sound as a Biometric. Pattern Recognition 2008, 41, 906–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folland, E.D.; Kriegel, B.J.; Henderson, W.G.; Hammermeister, K.E.; Sethi, G.K.; null null. Implications of Third Heart Sounds in Patients with Valvular Heart Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 1992, 327, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.L.; Ko, P.Y.; Jaw, F.S. Detection of the Third and Fourth Heart Sounds Using Hilbert-Huang Transform. BioMed Engineering OnLine 2012, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuenyong, S.; Nishihara, A.; Kongprawechnon, W.; Tungpimolrut, K. A framework for automatic heart sound analysis without segmentation. Biomedical Engineering Online 2011, 10, 13, Published February 9, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkomar, A.; Dean, J.; Kohane, I. Machine Learning in Medicine. New England Journal of Medicine 2019, 380, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.A.; Singh, S.A.; Devi, N.D.; Majumder, S. Heart Abnormality Classification Using PCG and ECG Recordings. Computación y Sistemas 2021, 25, 381–391, Epub 11-Oct-2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepehri, A.A.; Gharehbaghi, A.; Dutoit, T.; Kocharian, A.; Kiani, A. A novel method for pediatric heart sound segmentation without using the ECG. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2010, 99, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, A.; Teixeira, R.; Fontes-Carvalho, R.; Coimbra, M.; Renna, F. On the Impact of Synchronous Electrocardiogram Signals for Heart Sounds Segmentation. Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC) 2023, 2023, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglogiannis, I.; Loukis, E.; Zafiropoulos, E.; Stasis, A. Support vectors machine-based identification of heart valve diseases using heart sounds. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2009, 95, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, J.; Nogueira, D.; Ferreira, C.; Jorge, A.M.; Coimbra, M. The robustness of random forest and support vector machine algorithms to a faulty heart sound segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 44th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1989–1992.

- Li, J.; Ke, L.; Du, Q. Classification of Heart Sounds Based on the Wavelet Fractal and Twin Support Vector Machine. Entropy 2019, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.L.; Coimbra, M.T.; Renna, F. Markov-Based Neural Networks for Heart Sound Segmentation: Using Domain Knowledge in a Principled Way. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023, 27, 5357–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, Y.; Ma, K.; Liu, M. Temporal convolutional network connected with an anti-arrhythmia hidden semi-Markov model for heart sound segmentation. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 7049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.L.; Coimbra, M.T.; Renna, F. Markov-based Neural Networks for Heart Sound Segmentation: Using domain knowledge in a principled way. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, L. Multiscale analysis of heart sound for segmentation using multiscale Hilbert envelope. In Proceedings of the 2015 13th International Conference on ICT and Knowledge Engineering (ICT & Knowledge Engineering 2015). IEEE, 2015, pp. 33–37.

- Moukadem, A.; Dieterlen, A.; Hueber, N.; Brandt, C. A robust heart sounds segmentation module based on S-transform. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2013, 8, 273–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, X.; Ma, X. An automatic segmentation method for heart sounds. Biomedical engineering online 2018, 17, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kui, H.; Pan, J.; Zong, R.; Yang, H.; Wang, W. Heart sound classification based on log Mel-frequency spectral coefficients features and convolutional neural networks. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 69, 102893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Qian, K.; Dong, F.; Dai, Z.; Nejdl, W.; Yamamoto, Y.; Schuller, B.W. Deep attention-based neural networks for explainable heart sound classification. Machine Learning with Applications 2022, 9, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W.; Yuan, J.; Yuan, C.; Wang, Q.; Liu, F.; Wang, Y. A new approach for the detection of abnormal heart sound signals using TQWT, VMD and neural networks. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 54, 1613–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.K.; Ponnalagu, R.; Tripathy, R.K.; Panda, G.; Pachori, R.B. Automated heart sound activity detection from PCG signal using time–frequency-domain deep neural network. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, S.; Pi, X.; Liu, H. Research on Segmentation and Classification of Heart Sound Signals Based on Deep Learning. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Herrera, P.; Abonza, V.; Sánchez-Contreras, J.; Darszon, A.; Guerrero, A. Deep Learning-Based Classification and Segmentation of Sperm Head and Flagellum for Image-Based Flow Cytometry. Computación y Sistemas 2023, 27, 1133–1145, Epub 17 de mayo de 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Herrera, P.; Montoya, F.; Rendón-Mancha, J.M.; Darszon, A.; Corkidi, G. 3-D +{t} Human Sperm Flagellum Tracing in Low SNR Fluorescence Images. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2018, 37, 2236–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, B.; Shen, C.; Tan, M.; Liu, L.; Reid, I. Structured binary neural networks for accurate image classification and semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition, 2019, pp. 413–422.

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention 2015, pp. 234–241.

- Liu, C.; Springer, D.; Li, Q.; Moody, B.; Juan, R.A.; Chorro, F.J.; Castells, F.; Roig, J.M.; Silva, I.; Johnson, A.E.W.; et al. An open access database for the evaluation of heart sound algorithms. Physiological Measurement 2016, 37, 2181–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoushan, M.M.; Reyes, B.A.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Chong, J.W. Non-contact HR monitoring via smartphone and webcam during different respiratory maneuvers and body movements. IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics 2020, 25, 602–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoushan, M.M.; Reyes, B.A.; Rodriguez, A.M.; Chong, J.W. Contactless heart rate variability (HRV) estimation using a smartphone during respiratory maneuvers and body movement. In Proceedings of the 2021 43rd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 84–87.

- Camacho-Juárez, J.S.; Alexander-Reyes, B.; Morante-Lezama, A.; Méndez-García, M.; González-Aguilar, H.; Rodríguez-Leyva, I.; Nuñez-Olvera, O.F.; Polanco-González, C.; Gorordo-Delsol, L.A.; Castañón-González, J.A. A novel disposable sensor for measure intra-abdominal pressure. Cirugía y cirujanos 2020, 88, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olvera-Montes, N.; Reyes, B.; Charleston-Villalobos, S.; González-Camarena, R.; MejíaÁvila, M.; Dorantes-Méndez, G.; Reulecke, S.; Aljama-Corrales, T.A. Detection of Respiratory Crackle Sounds via an Android Smartphone-based System. In Proceedings of the 2018 40th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); 2018; pp. 1620–1623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XU, W.; DU, F. A ROBUST QRS COMPLEX DETECTION METHOD BASED ON SHANNON ENERGY ENVELOPE AND HILBERT TRANSFORM. Journal of Mechanics in Medicine and Biology 2022, 22, 2240013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafando, A.; Fournier, E.; Serhir, B.; Martineau, C.; Doualla-Bell, F.; Sangaré, M.N.; Sylla, M.; Chamberland, A.; El-Far, M.; Charest, H.; et al. HIV-1 envelope sequence-based diversity measures for identifying recent infections. PLOS ONE 2017, 12, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, T.H.; Poudel, K.N.; Hu, Y. Time-Frequency Analysis, Denoising, Compression, Segmentation, and Classification of PCG Signals. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 160882–160890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).