Submitted:

17 May 2024

Posted:

21 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Improved Accuracy: Achieve high Dice similarity coefficient (DSC) and intersection over union (IoU) metrics, indicating accurate LV delineation.

- Enhanced Generalizability: Demonstrate robust performance across diverse echocardiographic images with varying acquisition views and patient characteristics.

- Computational Efficiency: Maintain faster inference times compared to traditional CNN-based segmentation models.

2. Related Work

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset

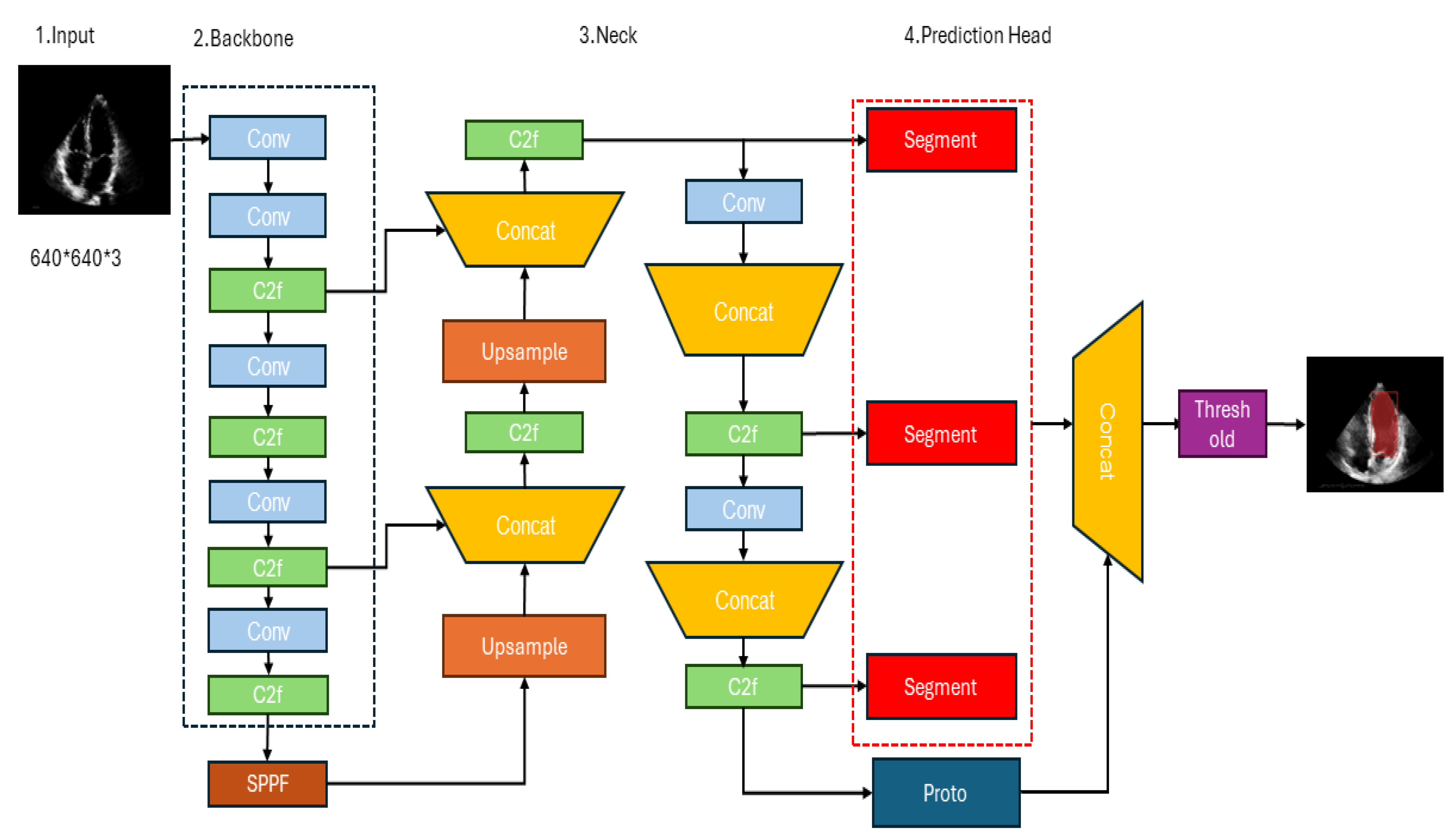

3.2. YOLOv8’s architecture

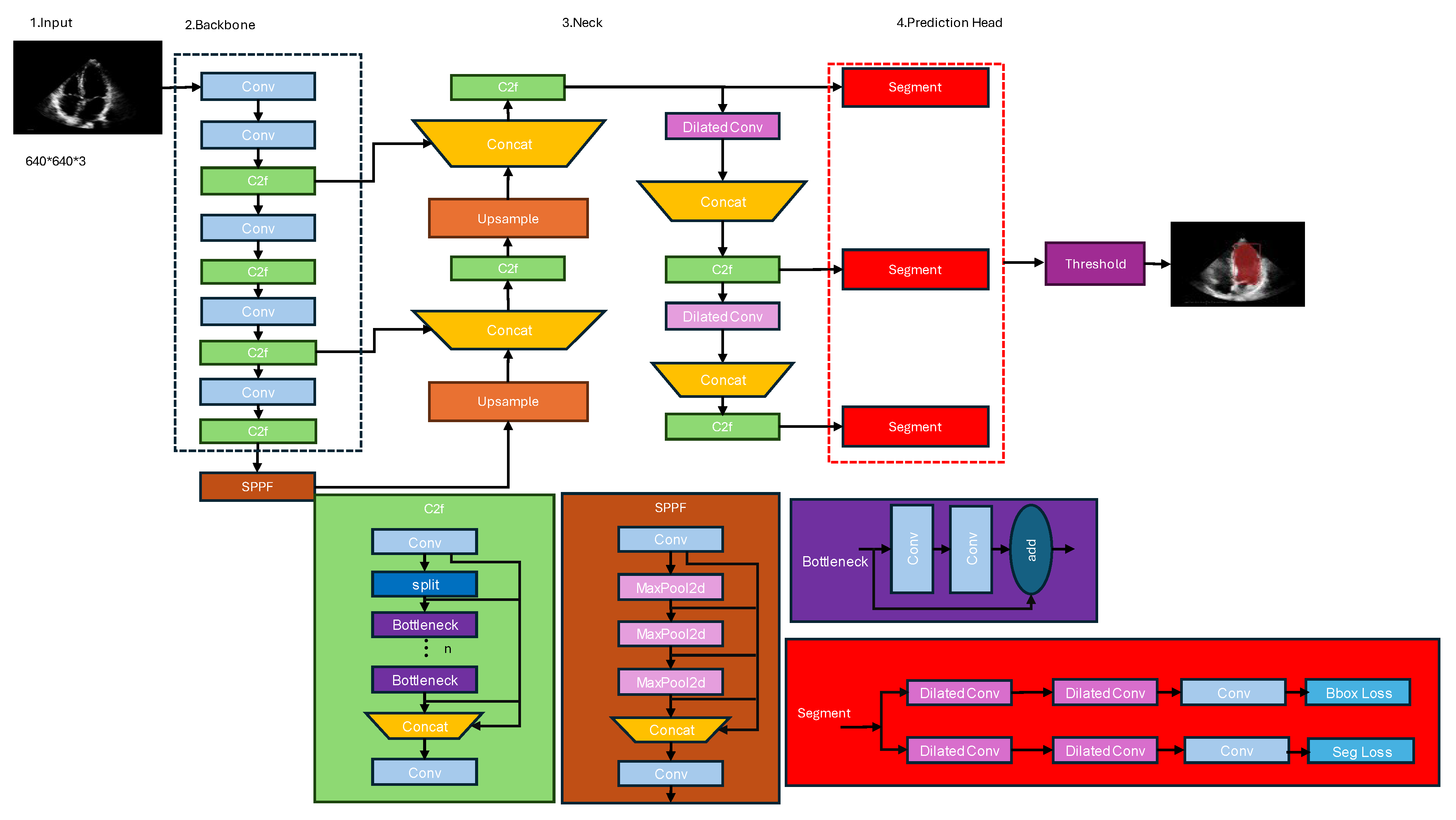

3.3. Proposed Architecture

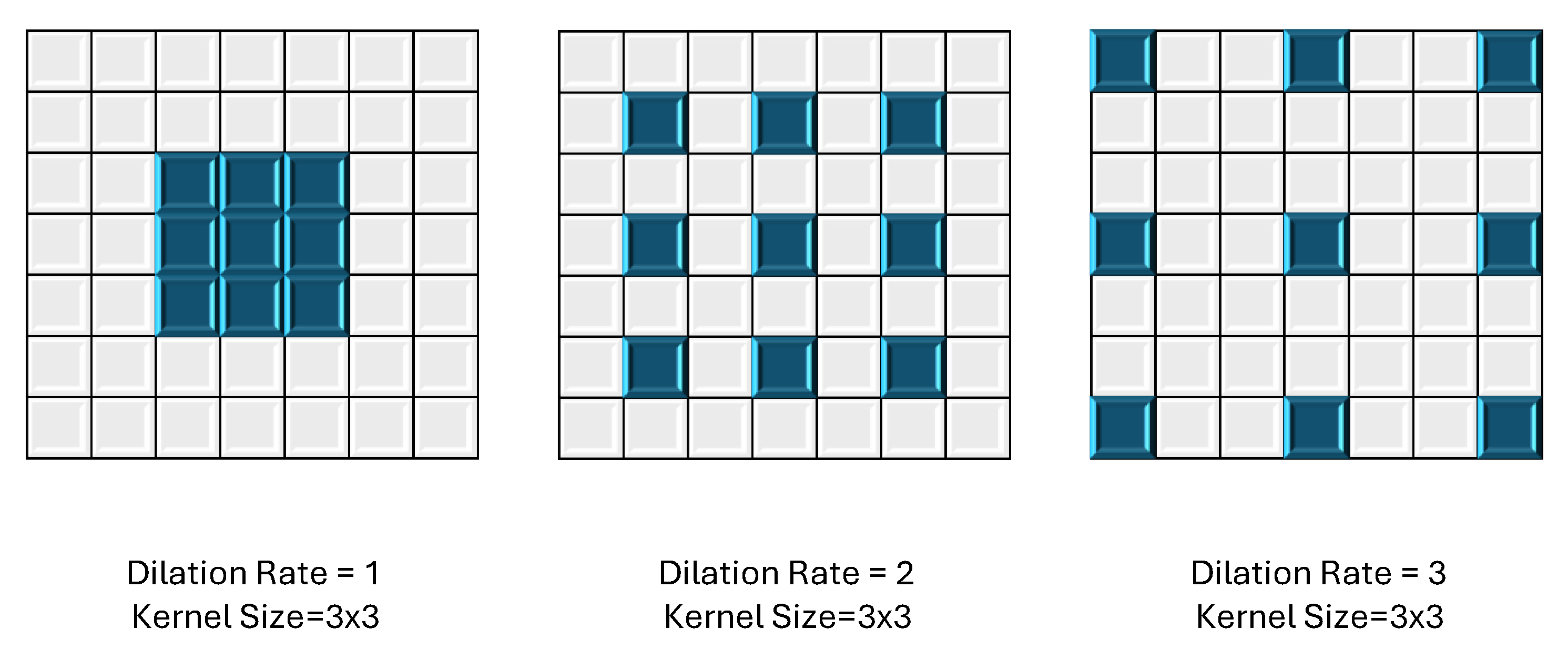

3.3.1. Dilated Convolution:

3.3.2. C2F (Class-to-Fortitude) Module:

3.3.3. Spatial Pyramid Pooling Fortitude Module:

3.3.4. Segmentation Module

- Convolutional Layer: The input feature maps are first processed by a convolutional layer with a 1x1 kernel size. This layer serves as a dimensionality reduction step, reducing the number of channels in the feature maps. This operation is computationally efficient and helps reduce the overall computational complexity of the network.

- Batch Normalization and Activation: After the convolutional layer, batch normalization is applied to stabilize the training process and improve convergence. This is followed by an activation function, typically the leaky Rectified Linear Unit ReLU), which introduces non-linearity into the feature representations.

- Convolutional Layer with Bottleneck: The next step involves a convolutional layer with a 3×3 kernel size, which is the main feature extraction component of the module. However, instead of using the full number of channels, a bottleneck approach is employed. The number of channels in this layer is typically set to a lower value (e.g., one-quarter or one-half of the input channels) to reduce computational complexity while still capturing important spatial and semantic information.

3.4. Evaluation Metric

3.4.1. Intersection over Union (IoU)

3.4.2. Mean Average Precision (mAP)

3.4.3. Precision-recall Curve

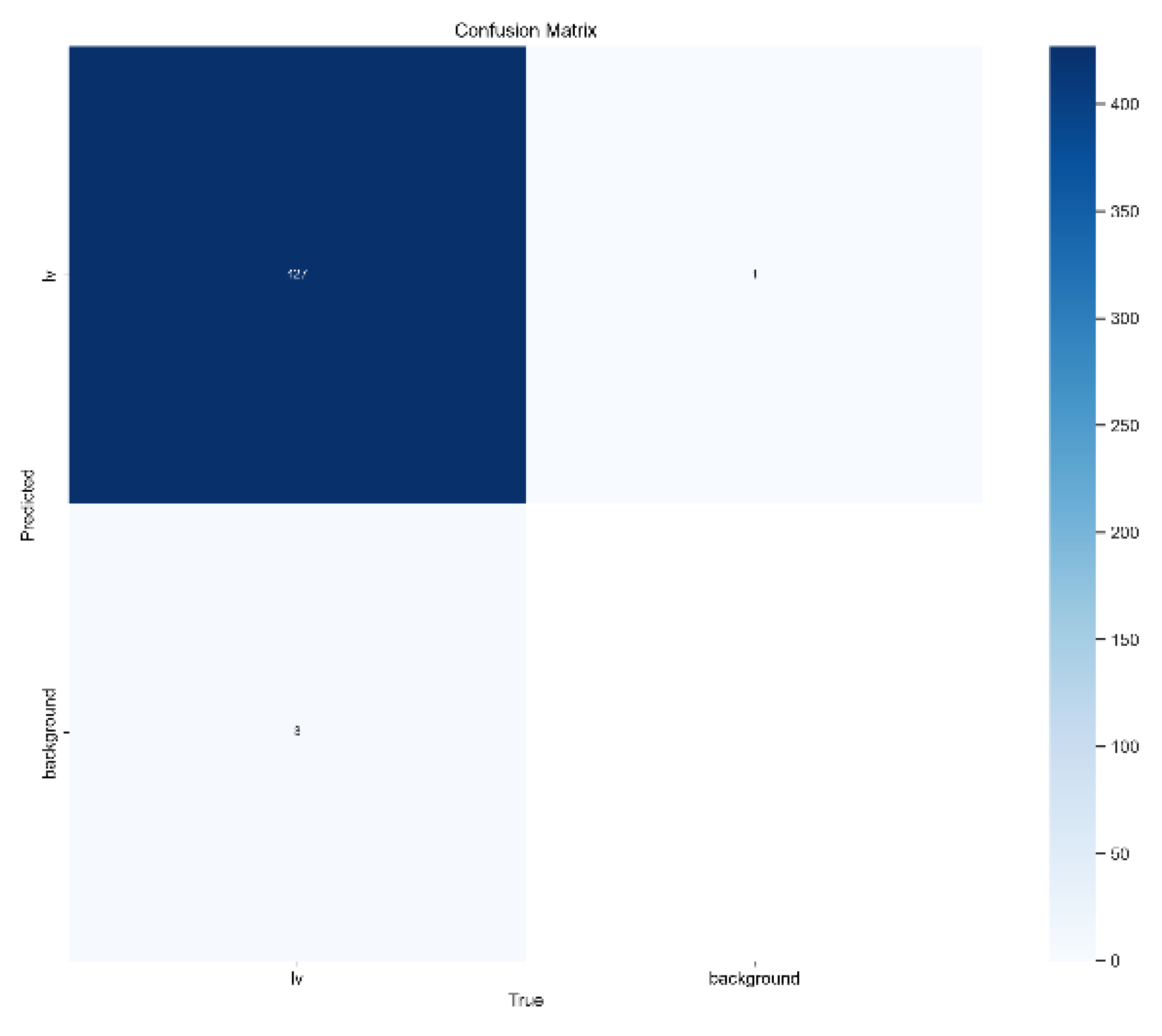

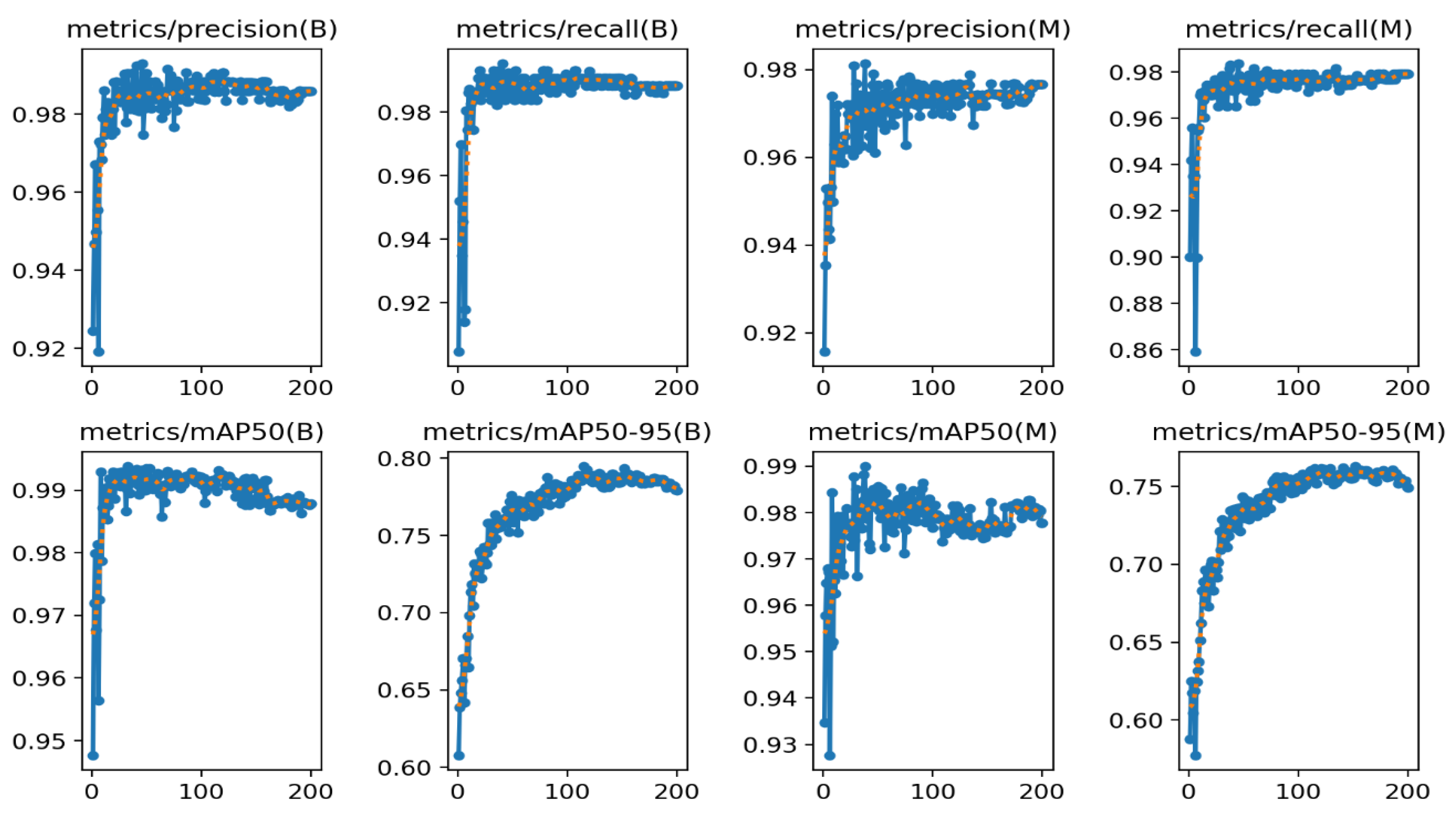

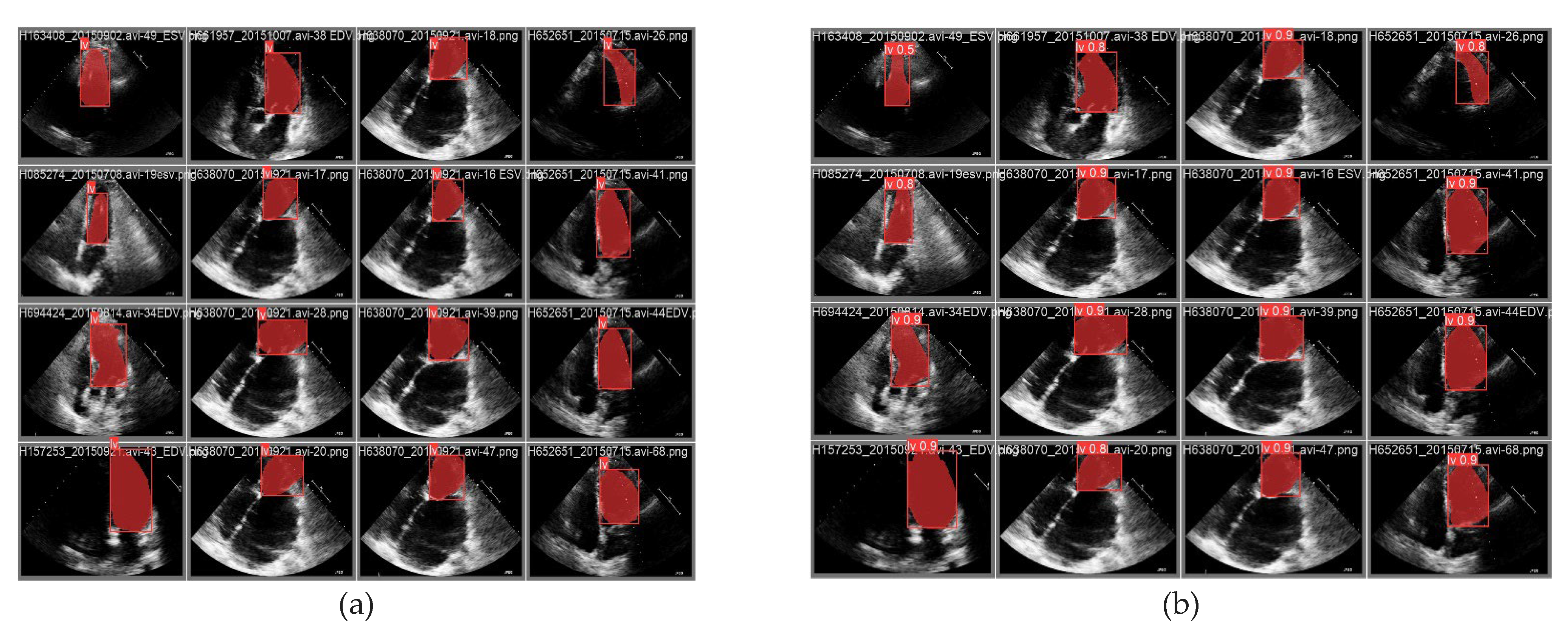

4. Results and Discussions

5. Conclusion

- Larger and more diverse datasets: Training segmentation models on larger and more diverse datasets, encompassing various pathologies, imaging modalities, and acquisition protocols, can enhance their generalization capabilities and robustness.

- Incorporation of temporal information: Echocardiograms capture dynamic cardiac cycles. Leveraging temporal information by integrating recurrent neural networks or temporal modeling techniques could improve segmentation accuracy and consistency across frames.

- Uncertainty quantification: Developing methods to quantify the uncertainty or confidence of segmentation predictions can provide valuable insights for clinicians and aid in decision-making processes.

Contribution:

Institutional Review Board:

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gaziano, T.A. , Cardiovascular diseases worldwide. Public Health Approach Cardiovasc. Dis. Prev. Manag, 2022. 1: p. 8-18.

- Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Braun, L.T.; Ndumele, C.E.; Smith, S.C.; Sperling, L.S.; Virani, S.S.; Blumenthal, R.S. Use of Risk Assessment Tools to Guide Decision-Making in the Primary Prevention of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Special Report From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation 2019, 139, E1162–E1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Zhu, M.; Sahn, D.J.; Ashraf, M. Non-Invasive Evaluation of Heart Function with Four-Dimensional Echocardiography. PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0154996–e0154996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cacciapuoti, F. The role of echocardiography in the non-invasive diagnosis of cardiac amyloidosis. J. Echocardiogr. 2015, 13, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, R.; Bhagirath, P.; Claus, P.; Housden, R.J.; Chen, Z.; Karimaghaloo, Z.; Sohn, H.-M.; Rodríguez, L.L.; Vera, S.; Albà, X.; et al. Evaluation of state-of-the-art segmentation algorithms for left ventricle infarct from late Gadolinium enhancement MR images. Med Image Anal. 2016, 30, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slomka, P.J.; Dey, D.; Sitek, A.; Motwani, M.; Berman, D.S.; Germano, G. Cardiac imaging: working towards fully-automated machine analysis & interpretation. Expert Rev. Med Devices 2017, 14, 197–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.; Hedayat, M.; Vaitkus, V.V.; Belohlavek, M.; Krishnamurthy, V.; Borazjani, I. Automatic segmentation of the left ventricle in echocardiographic images using convolutional neural networks. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2021, 11, 1763–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, K.K.L.; Fortino, G.; Abbott, D. Deep learning-based cardiovascular image diagnosis: A promising challenge. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2020, 110, 802–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolgharni, M. , Automated assessment of echocardiographic image quality using deep convolutional neural networks. 2022, The University of West London.

- Luo, X.; Zhang, H.; Huang, X.; Gong, H.; Zhang, J. DBNet-SI: Dual branch network of shift window attention and inception structure for skin lesion segmentation. Comput. Biol. Med. 2024, 170, 108090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmieri, V.; Dahlöf, B.; DeQuattro, V.; Sharpe, N.; Bella, J.N.; de Simone, G.; Paranicas, M.; Fishman, D.; Devereux, R.B. Reliability of echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular structure and function: The PRESERVE study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1999, 34, 1625–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, X.; Thomas, M.A.; Dise, J.; Kavanaugh, J.; Hilliard, J.; Zoberi, I.; Robinson, C.G.; Hugo, G.D. Robustness of deep learning segmentation of cardiac substructures in noncontrast computed tomography for breast cancer radiotherapy. Med Phys. 2021, 48, 7172–7188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, A.S.; Sandino, C.M.; Cole, E.K.; Larson, D.B.; Gold, G.E.; Vasanawala, S.S.; Lungren, M.P.; Hargreaves, B.A.; Langlotz, C.P. Prospective Deployment of Deep Learning in MRI: A Framework for Important Considerations, Challenges, and Recommendations for Best Practices. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2021, 54, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Yang, L.; Liang, B.; Li, S.; Xu, C. Fetal cardiac ultrasound standard section detection model based on multitask learning and mixed attention mechanism. Neurocomputing 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, M.G.; Abdulkadir, S.J.; Muneer, A.; Alqushaibi, A.; Sumiea, E.H.; Qureshi, R.; Al-Selwi, S.M.; Alhussian, H. A Comprehensive Systematic Review of YOLO for Medical Object Detection (2018 to 2023). IEEE Access 2024, 12, 57815–57836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, B.J. Point-of-care cardiac ultrasound techniques in the physical examination: better at the bedside. Heart 2017, 103, 987–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Villà, S.; Oliver, A.; Valverde, S.; Wang, L.; Zwiggelaar, R.; Lladó, X. A review on brain structures segmentation in magnetic resonance imaging. Artif. Intell. Med. 2016, 73, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, D. and J.S.R. Gibbs, From Early Morphometrics to Machine Learning—What Future for Cardiovascular Imaging of the Pulmonary Circulation? Diagnostics, 2020. 10(12): p. 1004.

- Lang, R.M.; Addetia, K.; Narang, A.; Mor-Avi, V. 3-Dimensional Echocardiography Latest Developments and Future Directions. JACC: Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, 1854–1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaffré, C.M.E. , Deep learning-based segmentation of the aorta from dynamic 2D magnetic resonance images. 2022.

- Roelandt, N.C. Nanda, L. Sugeng, Q.L. CAO, J. Azevedo, S.L. Schwartz, M.A. Vannan, A. Ludomirski, and G. Marx, Dynamic three-dimensional echocardiography: Methods and clinical potential. Echocardiography, 1994. 11(3): p. 237-259.

- Minaee, S., Y. Boykov, F. Porikli, A. Plaza, N. Kehtarnavaz, and D. Terzopoulos, Image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 2021. 44(7): p. 3523-3542.

- Li, X.; Li, M.; Yan, P.; Li, G.; Jiang, Y.; Luo, H.; Yin, S. Deep Learning Attention Mechanism in Medical Image Analysis: Basics and Beyonds. Int. J. Netw. Dyn. Intell. 2023, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oza, P.; Sharma, P.; Patel, S.; Adedoyin, F.; Bruno, A. Image Augmentation Techniques for Mammogram Analysis. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Shi, J.; Gu, L. A review of deep learning methods for semantic segmentation of remote sensing imagery. Expert Syst. Appl. 2021, 169, 114417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandhi, S.; Mosleh, W.; Shen, J.; Chow, C.-M. Automation, machine learning, and artificial intelligence in echocardiography: A brave new world. Echocardiography 2018, 35, 1402–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Qin, C.; Qiu, H.; Tarroni, G.; Duan, J.; Bai, W.; Rueckert, D. Deep Learning for Cardiac Image Segmentation: A Review. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2020, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suri, J.; Liu, K.; Singh, S.; Laxminarayan, S.; Zeng, X.; Reden, L. Shape recovery algorithms using level sets in 2-D/3-D medical imagery: a state-of-the-art review. IEEE Trans. Inf. Technol. Biomed. 2002, 6, 8–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tajbakhsh, N.; Jeyaseelan, L.; Li, Q.; Chiang, J.N.; Wu, Z.; Ding, X. Embracing imperfect datasets: A review of deep learning solutions for medical image segmentation. Med Image Anal. 2020, 63, 101693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L., Y. Zhang, J. Chen, S. Zhang, and D.Z. Chen. Suggestive annotation: A deep active learning framework for biomedical image segmentation. in Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention− MICCAI 2017: 20th International Conference, Quebec City, QC, Canada, -13, 2017, Proceedings, Part III 20. 2017. Springer. 11 September.

- Greenwald, N.F.; Miller, G.; Moen, E.; Kong, A.; Kagel, A.; Dougherty, T.; Fullaway, C.C.; McIntosh, B.J.; Leow, K.X.; Schwartz, M.S.; et al. Whole-cell segmentation of tissue images with human-level performance using large-scale data annotation and deep learning. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 555–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, D. , Synthetic Ultrasound Video Generation with Generative Adversarial Networks. 2023, Carleton University.

- Xiong, Z.; Xia, Q.; Hu, Z.; Huang, N.; Bian, C.; Zheng, Y.; Vesal, S.; Ravikumar, N.; Maier, A.; Yang, X.; et al. A global benchmark of algorithms for segmenting the left atrium from late gadolinium-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Med Image Anal. 2020, 67, 101832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Z.; Usman, M.; Jeon, M.; Gwak, J. Cascade multiscale residual attention CNNs with adaptive ROI for automatic brain tumor segmentation. Inf. Sci. 2022, 608, 1541–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valindria, V.V.; Lavdas, I.; Bai, W.; Kamnitsas, K.; Aboagye, E.O.; Rockall, A.G.; Rueckert, D.; Glocker, B. Reverse Classification Accuracy: Predicting Segmentation Performance in the Absence of Ground Truth. IEEE Trans. Med Imaging 2017, 36, 1597–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Ren, S.; Lu, Y.; Fu, X.; Wong, K.K.L. Deep learning-based automatic segmentation of images in cardiac radiography: A promising challenge. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 220, 106821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E., A. Feragen, M.L. da Costa Zemsch, A. Henriksen, O.E. Wiese Christensen, M. Ganz, and A.s.D.N. Initiative. Feature robustness and sex differences in medical imaging: a case study in MRI-based Alzheimer’s disease detection. in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2022. Springer.

- Niu, S.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, H. A Decade Survey of Transfer Learning (2010–2020). IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2020, 1, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z., K. Lin, A.K. Jain, and J. Zhou, Transfer learning in deep reinforcement learning: A survey. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2023.

- Zhang, Y.; Liao, Q.V.; Bellamy, R.K.E. Effect of confidence and explanation on accuracy and trust calibration in AI-assisted decision making. FAT* '20: Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, SpainDATE OF CONFERENCE;

- Dergachyova, O.; Bouget, D.; Huaulmé, A.; Morandi, X.; Jannin, P. Automatic data-driven real-time segmentation and recognition of surgical workflow. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2016, 11, 1081–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacob, C.; Sanchez-Vazquez, A.; Ivory, C. Factors Impacting Clinicians’ Adoption of a Clinical Photo Documentation App and its Implications for Clinical Workflows and Quality of Care: Qualitative Case Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e20203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, P. and H. Liu. Simultaneous reconstruction and segmentation of MRI image by manifold learning. in 2019 IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium and Medical Imaging Conference (NSS/MIC). 2019. IEEE.

- Peng, P.; Lekadir, K.; Gooya, A.; Shao, L.; Petersen, S.E.; Frangi, A.F. A review of heart chamber segmentation for structural and functional analysis using cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Magn. Reson. Mater. Physics, Biol. Med. 2016, 29, 155–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, A.; Kolossváry, M.; Išgum, I.; Maurovich-Horvat, P.; Slomka, P.J.; Dey, D. Artificial intelligence: improving the efficiency of cardiovascular imaging. Expert Rev. Med Devices 2020, 17, 565–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peirlinck, M., F. S. Costabal, J. Yao, J. Guccione, S. Tripathy, Y. Wang, D. Ozturk, P. Segars, T. Morrison, and S. Levine, Precision medicine in human heart modeling: Perspectives, challenges, and opportunities. Biomechanics and modeling in mechanobiology, 2021. 20: p. 803-831.

- Madani, A.; Ong, J.R.; Tibrewal, A.; Mofrad, M.R.K. Deep echocardiography: data-efficient supervised and semi-supervised deep learning towards automated diagnosis of cardiac disease. npj Digit. Med. 2018, 1, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, M.E.; Mitchell, M.S. Ethical and Unethical Leadership: Exploring New Avenues for Future Research. Bus. Ethic- Q. 2010, 20, 583–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Siqueira, V.S.; Borges, M.M.; Furtado, R.G.; Dourado, C.N.; da Costa, R.M. Artificial intelligence applied to support medical decisions for the automatic analysis of echocardiogram images: A systematic review. Artif. Intell. Med. 2021, 120, 102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ultralytics. YOLOv8 – Ultralytics—Revolutionizing the World of Vision AI (n.d.). 22 Apr 2024]; Available from: https://www.ultralytics.com/yolo.

- Wang, C.-Y., H.-Y.M. Liao, Y.-H. Wu, P.-Y. Chen, J.-W. Hsieh, and I.-H. Yeh. CSPNet: A new backbone that can enhance learning capability of CNN. in Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops. 2020.

- Girshick, R. Fast r-cnn. in Proceedings of the IEEE international conference on computer vision. 2015.

- Gonzalez-Jimenez, A., S. Lionetti, P. Gottfrois, F. Gröger, M. Pouly, and A.A. Navarini. Robust t-loss for medical image segmentation. in International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention. 2023. Springer.

- Milletari, F.; Navab, N.; Ahmadi, S.-A. V-net: Fully convolutional neural networks for volumetric medical image segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2016 Fourth International Conference on 3D Vision (3DV), Stanford, CA, USA, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 565–571. [Google Scholar]

| Model | size (pixels) | Precision | Recall | mAP50 | mAP50-95 | params (M) | FLOPs (B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| YOLOv8n-seg | 416 | 0.97247 | 0.95840 | 0.96064 | 0.75742 | 3.4 | 12.6 |

| YOLOv8s-seg | 416 | 0.97306 | 0.96771 | 0.97887 | 0.75604 | 11.8 | 42.6 |

| YOLOv8m-seg | 416 | 0.97363 | 0.97692 | 0.97957 | 0.75818 | 27.3 | 110.2 |

| YOLOv8l-seg | 416 | 0.97338 | 0.97899 | 0.97964 | 0.75626 | 46 | 220.5 |

| YOLOv8x-seg | 416 | 0.97572 | 0.97907 | 0.98005 | 0.75784 | 71.8 | 344.1 |

| YOLOv8n-seg | 640 | 0.97448 | 0.97456 | 0.97973 | 0.75875 | 3.4 | 12.6 |

| YOLOv8s-seg | 640 | 0.97651 | 0.97571 | 0.98164 | 0.76066 | 11.8 | 42.6 |

| YOLOv8m-seg | 640 | 0.9768 | 0.97894 | 0.98271 | 0.75816 | 27.3 | 110.2 |

| YOLOv8l-seg | 640 | 0.97583 | 0.97770 | 0.98263 | 0.75821 | 46 | 220.5 |

| YOLOv8x-seg | 640 | 0.97654 | 0.97921 | 0.98269 | 0.75852 | 71.8 | 344.1 |

| YOLOv8n-seg | 1280 | 0.97651 | 0.97907 | 0.98154 | 0.75671 | 3.4 | 12.6 |

| YOLOv8s-seg | 1280 | 0.97654 | 0.97907 | 0.97932 | 0.75164 | 11.8 | 42.6 |

| YOLOv8m-seg | 1280 | 0.97657 | 0.97907 | 0.98108 | 0.75491 | 27.3 | 110.2 |

| YOLOv8l-seg | 1280 | 0.9766 | 0.97907 | 0.98126 | 0.75542 | 46 | 220.5 |

| YOLOv8x-seg | 1280 | 0.97661 | 0.97907 | 0.98071 | 0.75409 | 71.8 | 344.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).