Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

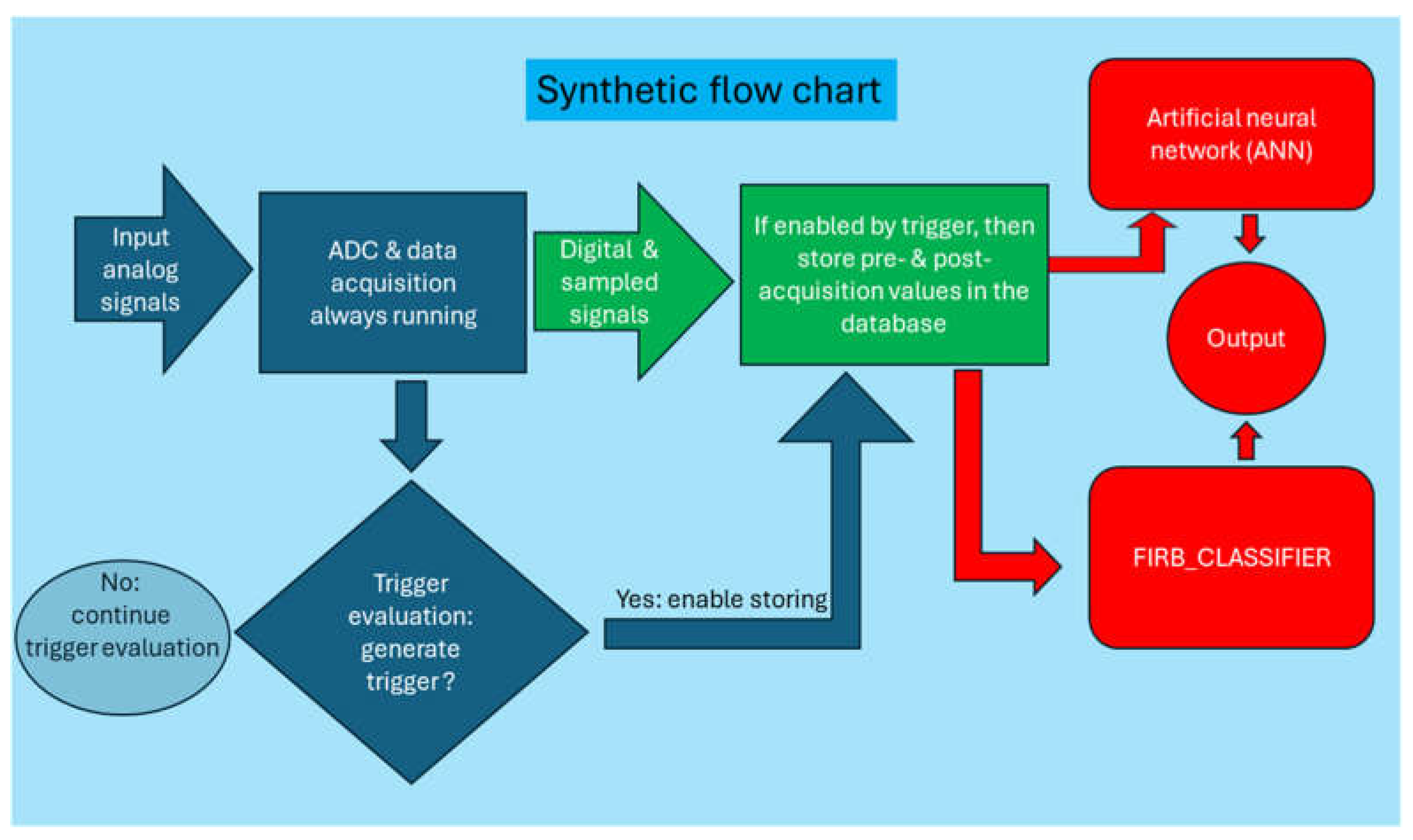

- an analysis of different algorithms proposed to generate automatically triggers to enable the data acquisition, with software simulations;

- the programs developed for the burst emulation with the goal to create a preliminary data base of possible transients;

- the software developed for the burst classification by using pattern recognition (PR) techniques developed in artificial intelligence (AI);

- considerations about noise cancelling possible strategy;

- considerations about the future use of artificial neural networks for pattern recognition.

1.1. A New Astronomy

1.1.1. Multi-Messenger Astronomy

1.1.2. Gamma-Ray Bursts

1.1.3. Fast Radio Bursts

- Black hole (BH) to white hole (WH) quantum transition [39].

- Asteroid/planet/white dwarf (WD) magnetosphere interaction with the wind from a orbited pulsar/Neutron Star (NS) [31].

- Core Collapse Supernovae [40].

- Binary WD merger to highly magnetic spinning WD [41].

- Evaporating primordial BH [42].

- Collision between axion stars and neutron stars [44].

- Explosive decay of axion mini-clusters [45].

- Blitzar collapse to BH of a supermassive NS [48].

- Hyper pulses from extra-galactic NSs [51].

- Pulsar magnetosphere “combed” by plasma stream (AGN, SN, GRB,…) [52].

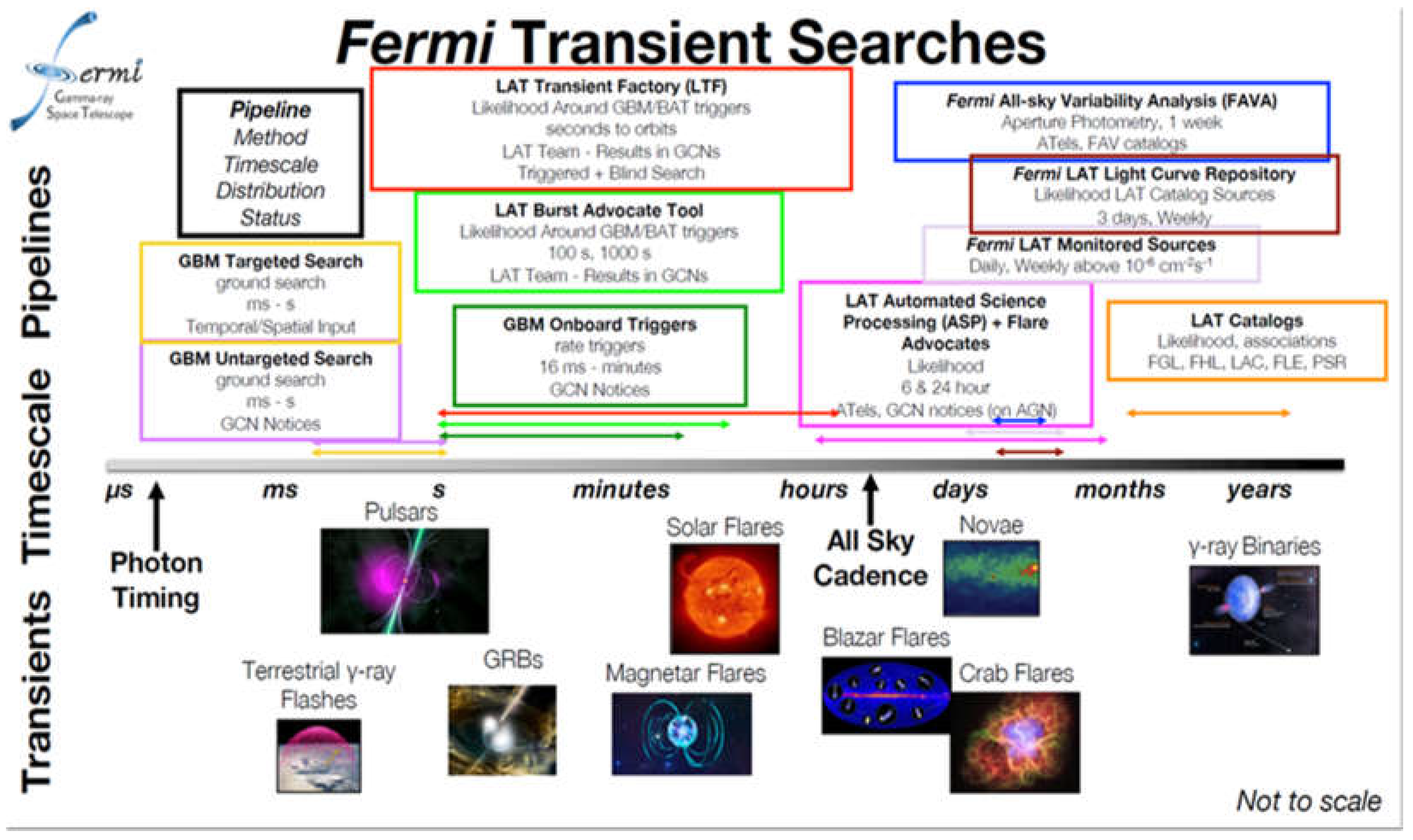

1.1.4. Time-Domain Astronomy

1.1.5. Directionality of the Detection

- Why look for fast IR bursts or transients? Answer: after gamma and radio, it is interesting to observe fast short signals in other parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

- Could fast IR bursts exist? Answer: specialized telescopes are necessary to answer the question even if the multiple theories about the fast radio burst genesis make intriguing to explore also the infrared range by dedicated strategies and instruments for ultrafast detection.

- Are there theories that predict them? The many theories proposed to explain the sources of Fast Radio Bursts can also be broadly adapted to justify the search for Fast IR Bursts.

- How to detect them? The aim of this paper is to propose an instrument to search for fast astronomical bursts, transients or flares in the mid-infrared range.

- The proposed instrument should be also inherently directional, which is important for identifying the direction of the sources.

- How? … Starting from Enrico Fermi!

2. Instrument Design Basic Concepts

2.1. Enrico Fermi’s Accelerator Laws

2.2. DAFNE and SINBAD

- DAFNE must be running (operative), with electron beam current stored.

- The two beams should be preferably colliding to have stable optics in both rings. Indeed, the collision kicks between the two beams change slightly the orbits of the beams and, as consequence, the alignment of the beamline.

- The infrared beamline alignment is possible only after the preliminary phase in which the operators adjust the orbits of the two particle beams. Each new collider run usually requires an orbit adjustment.

- No other experiment is using the IR beamline. Indeed there can be calls to use SINBAD by teams coming from outside LNF.

2.3. Diagnostics for Circular Accelerators

2.4. Particle Beam Fast Instabilities

2.5. Trigger to Record the Instabilities

- simply manual, by the operator;

- generated by the machine master clock;

- generated by bunch injection in the ring;

- correlated to the instability arising.

2.6. How to Identify the Instability Source

3. Time-Resolved Infrared Detection

3.1. Basics of the Project

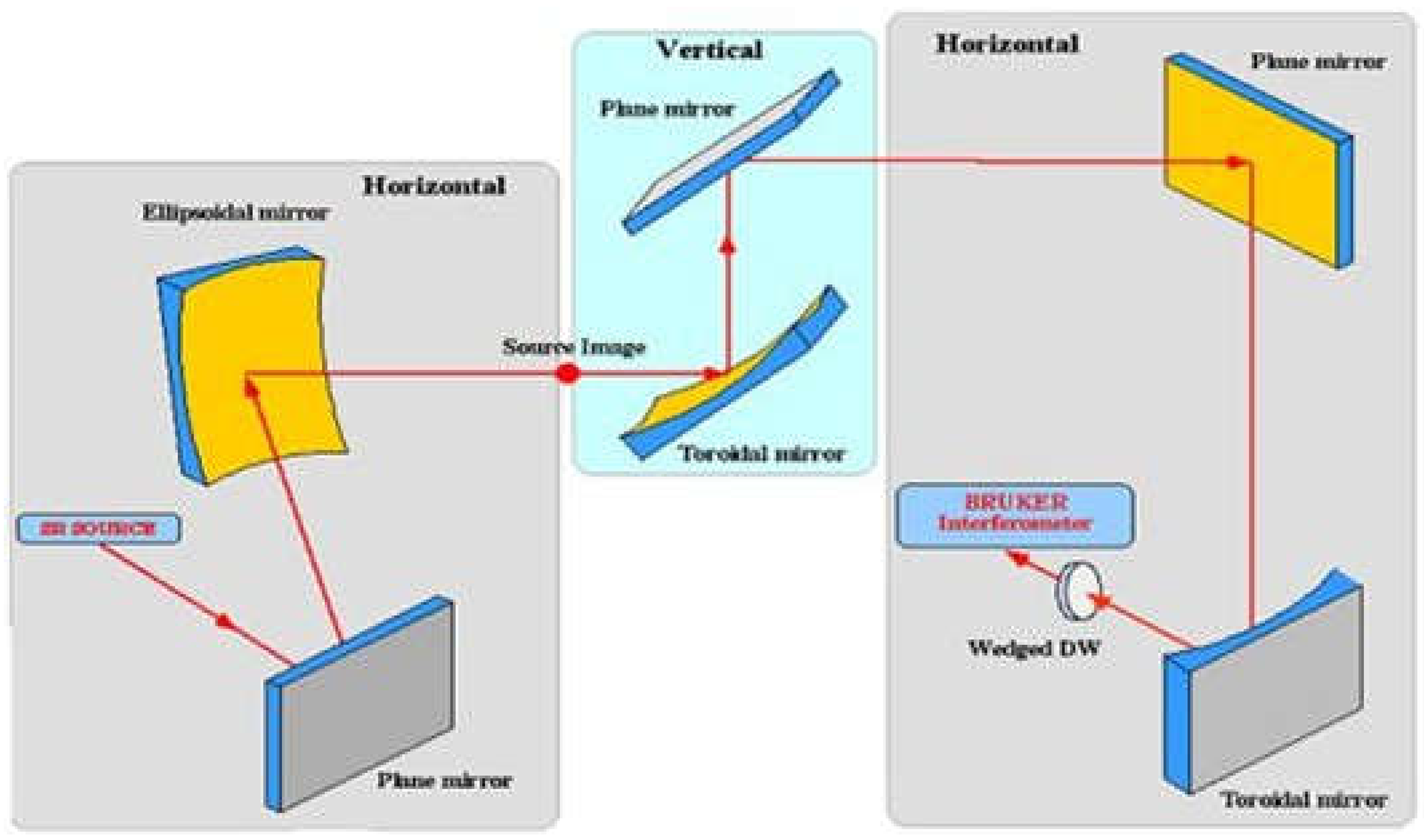

3.2. Synchrotron Radiation Infrared Beamline

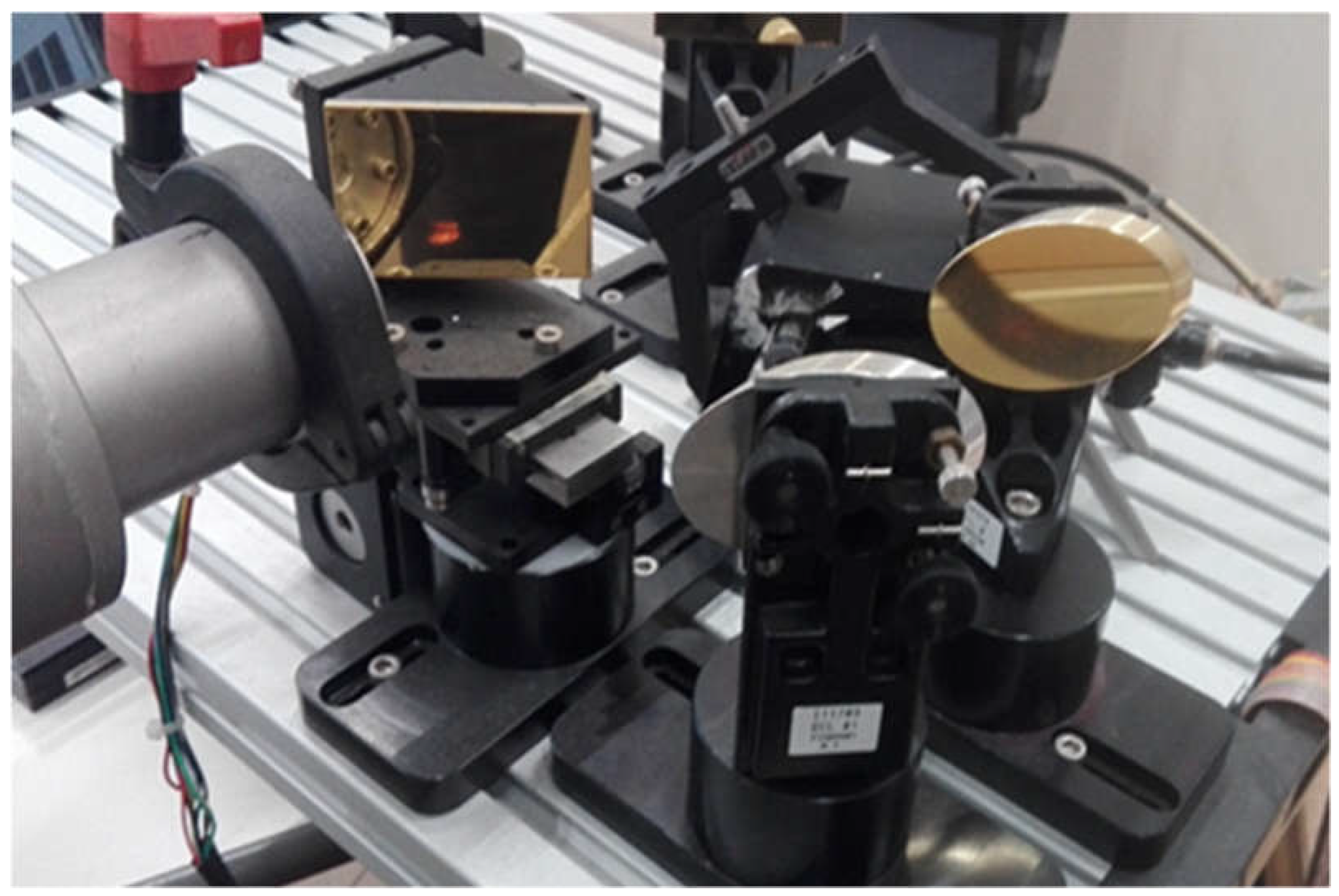

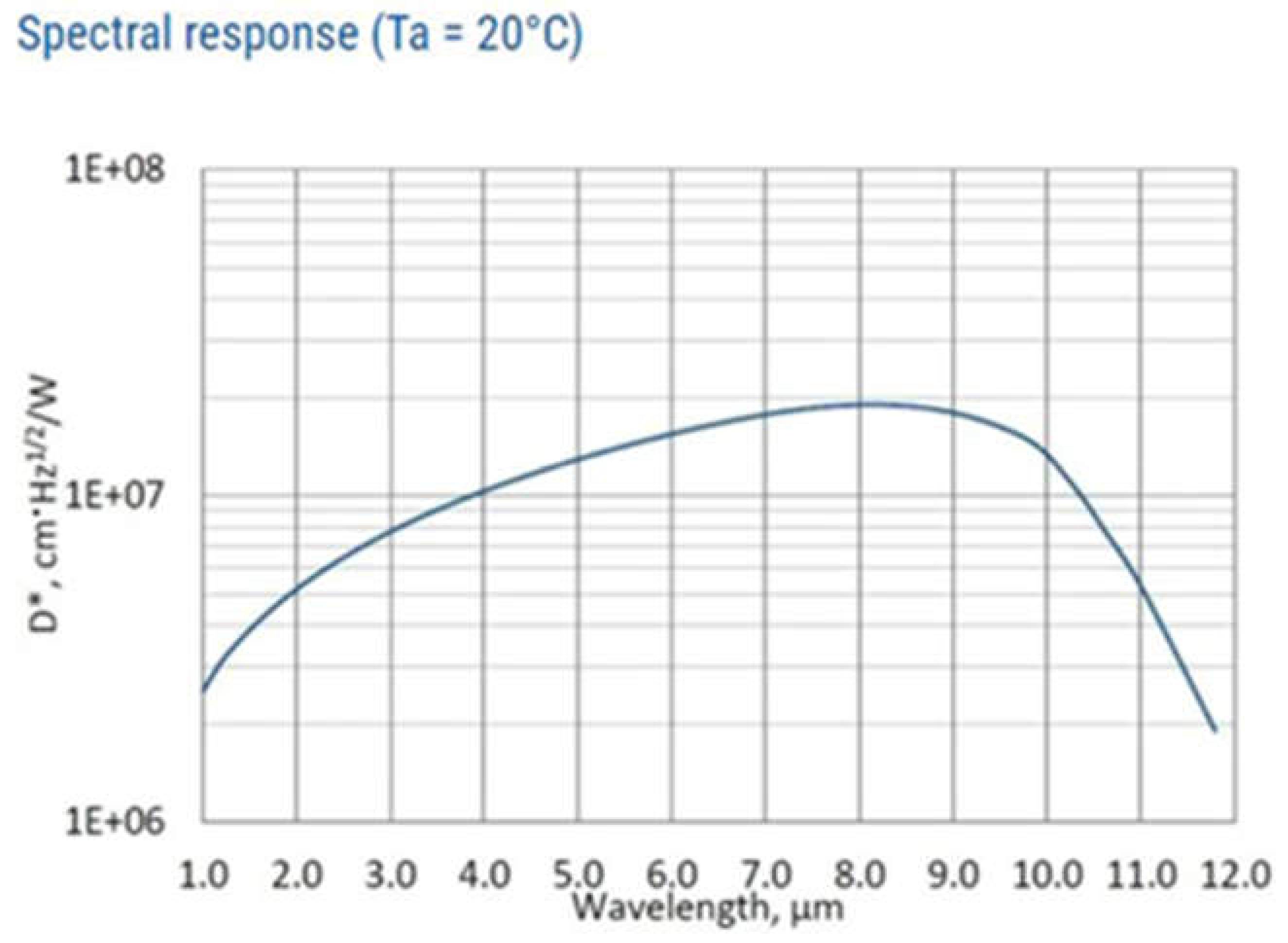

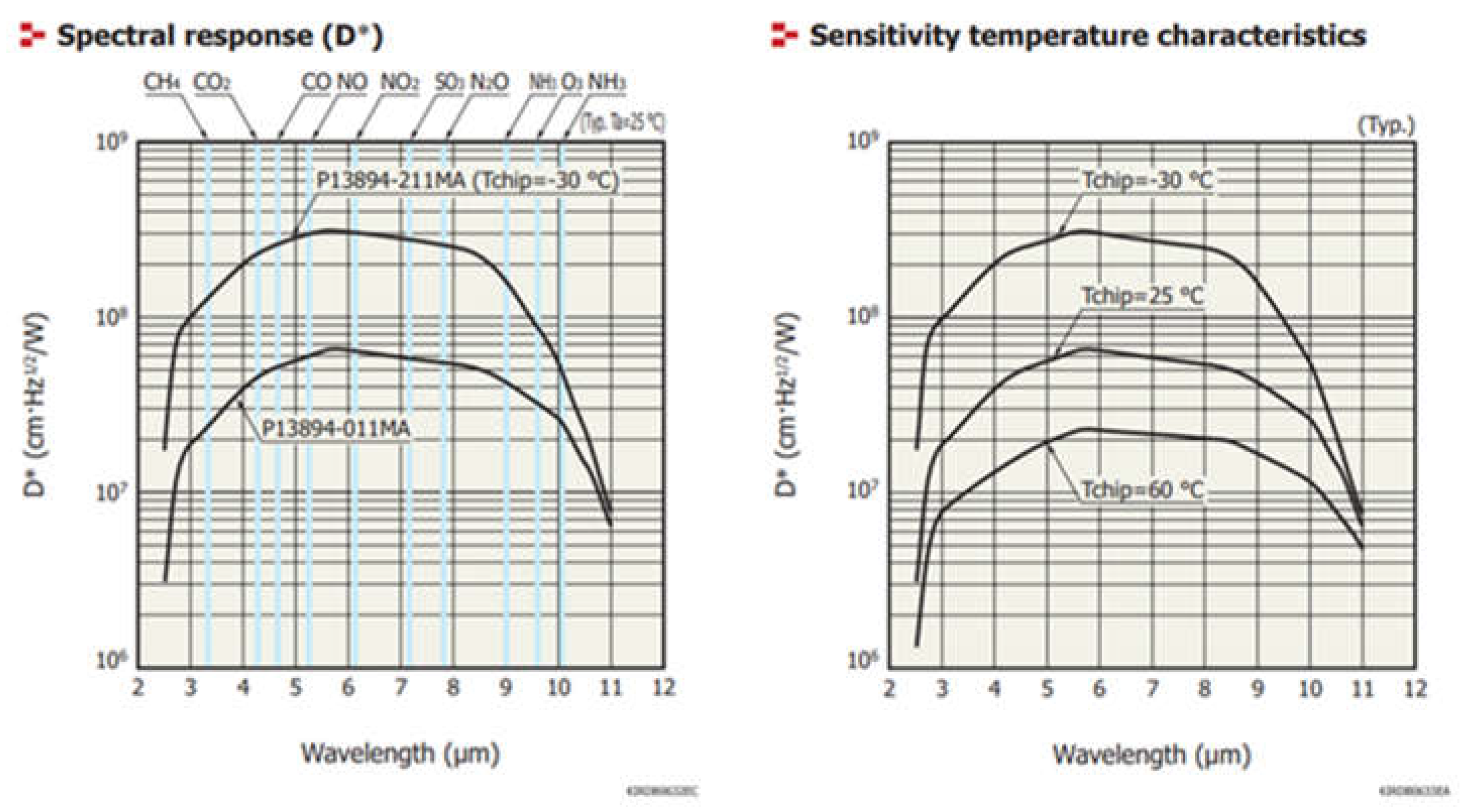

3.3. HgCdTe Detectors

3.4. InAsSb Detectors

4. Tests and Results

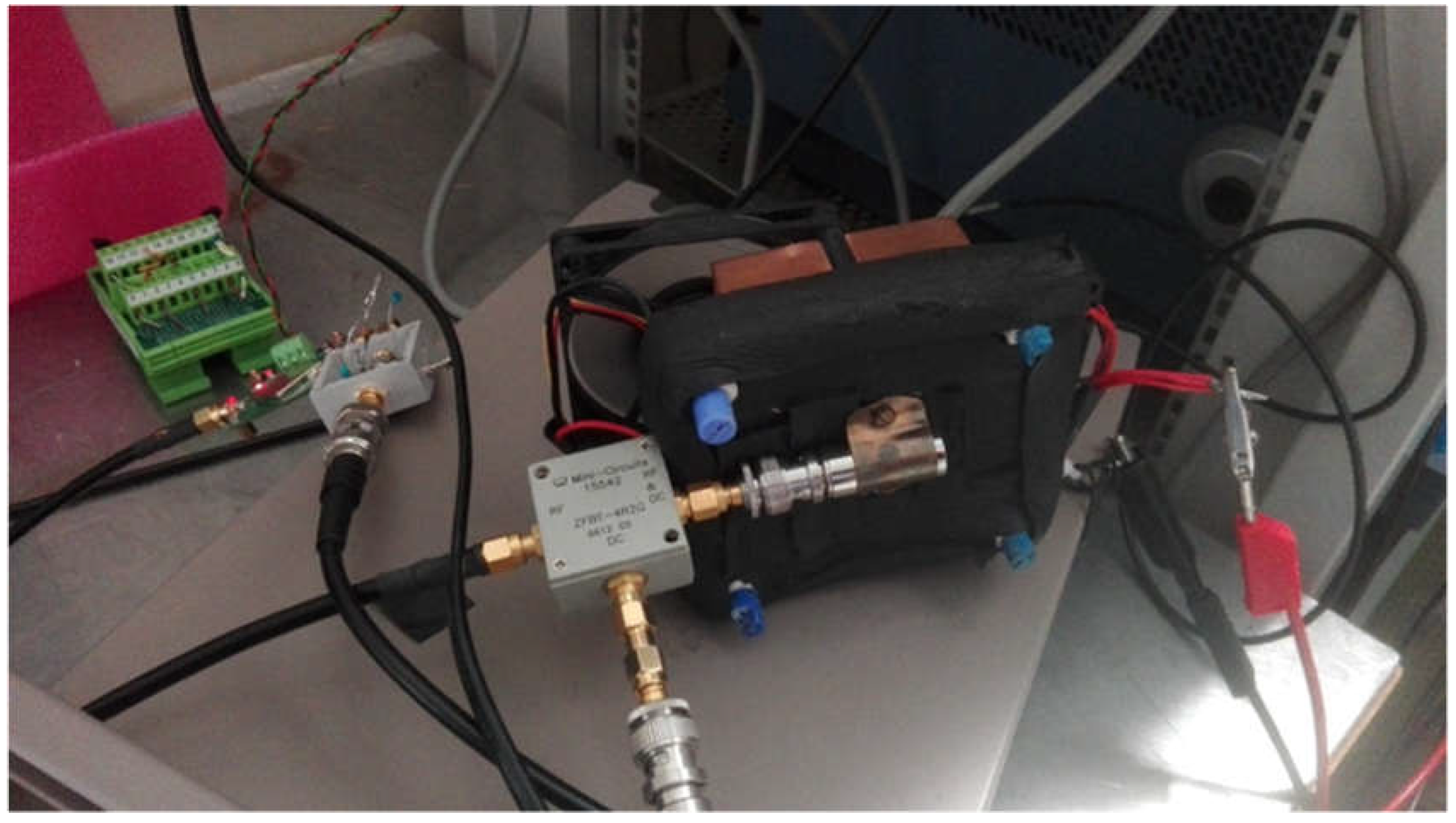

4.1. Front End Analog Module

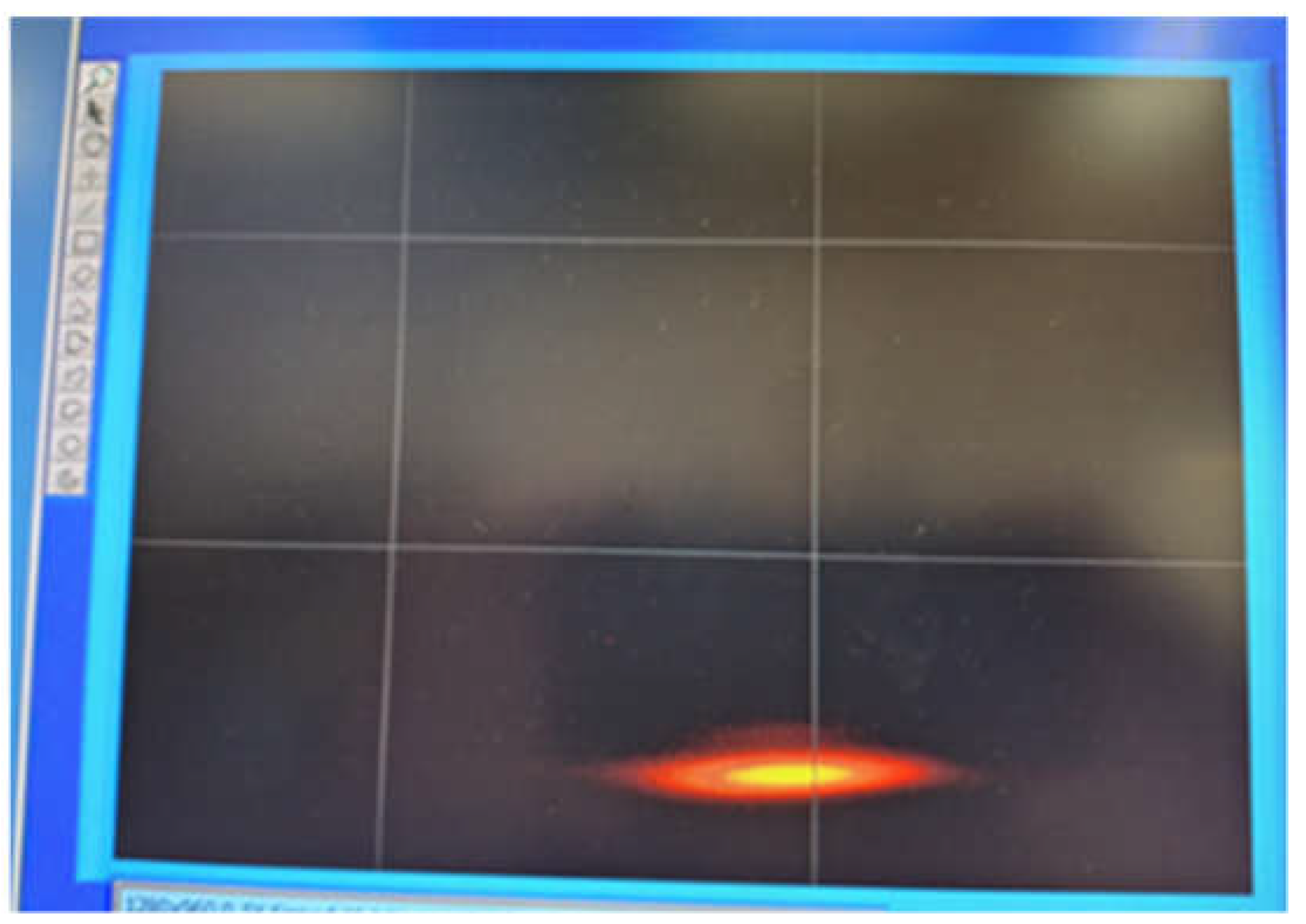

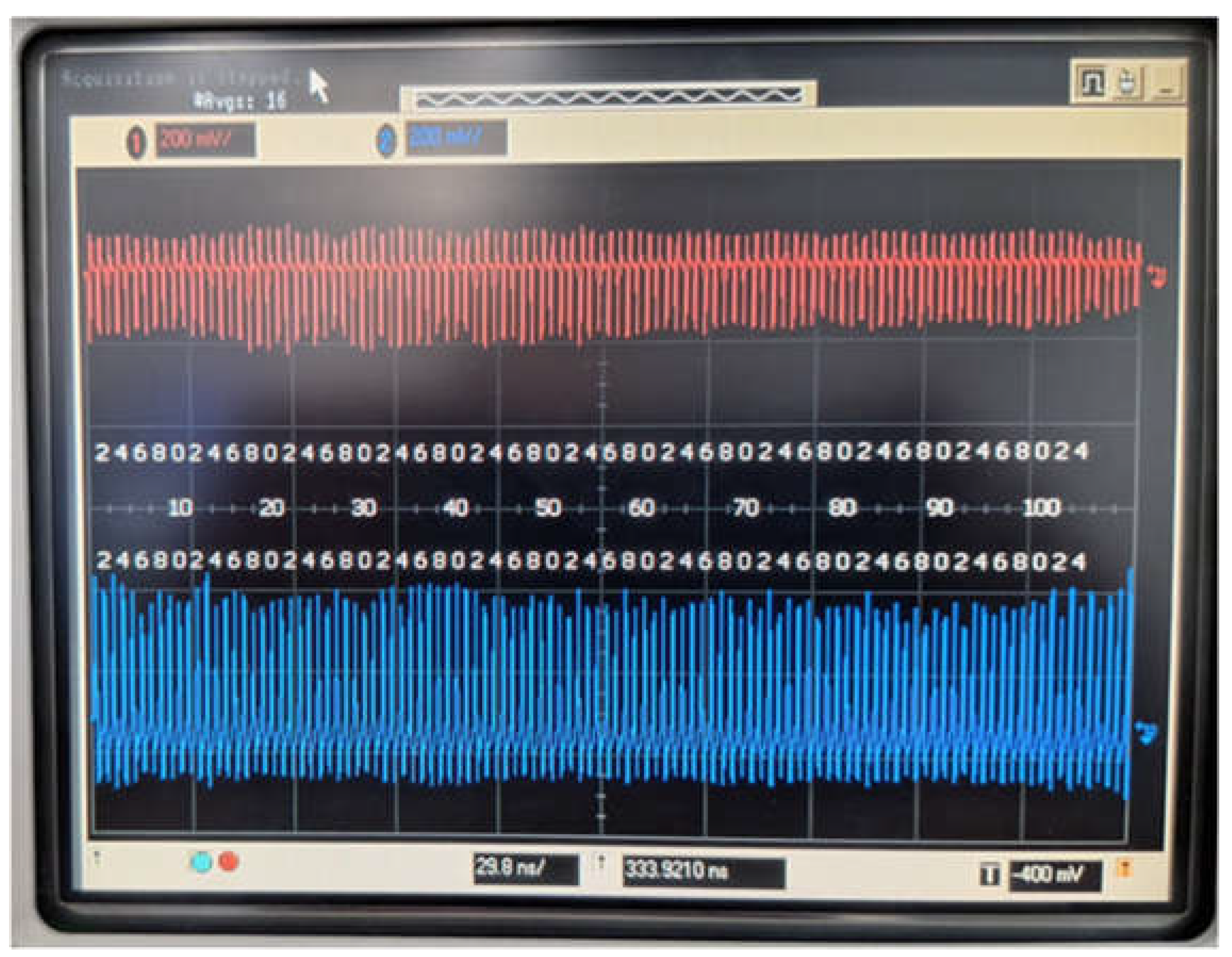

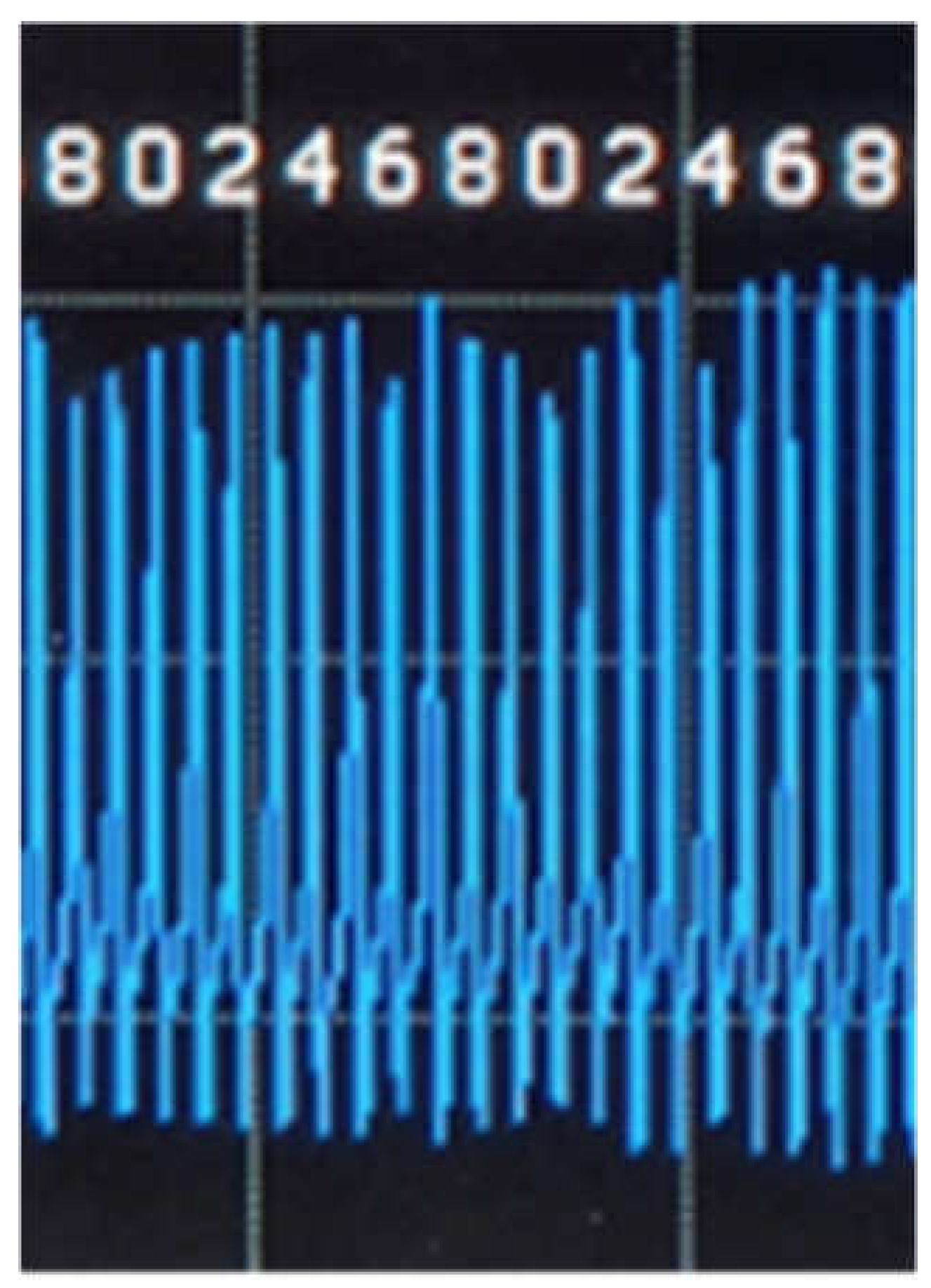

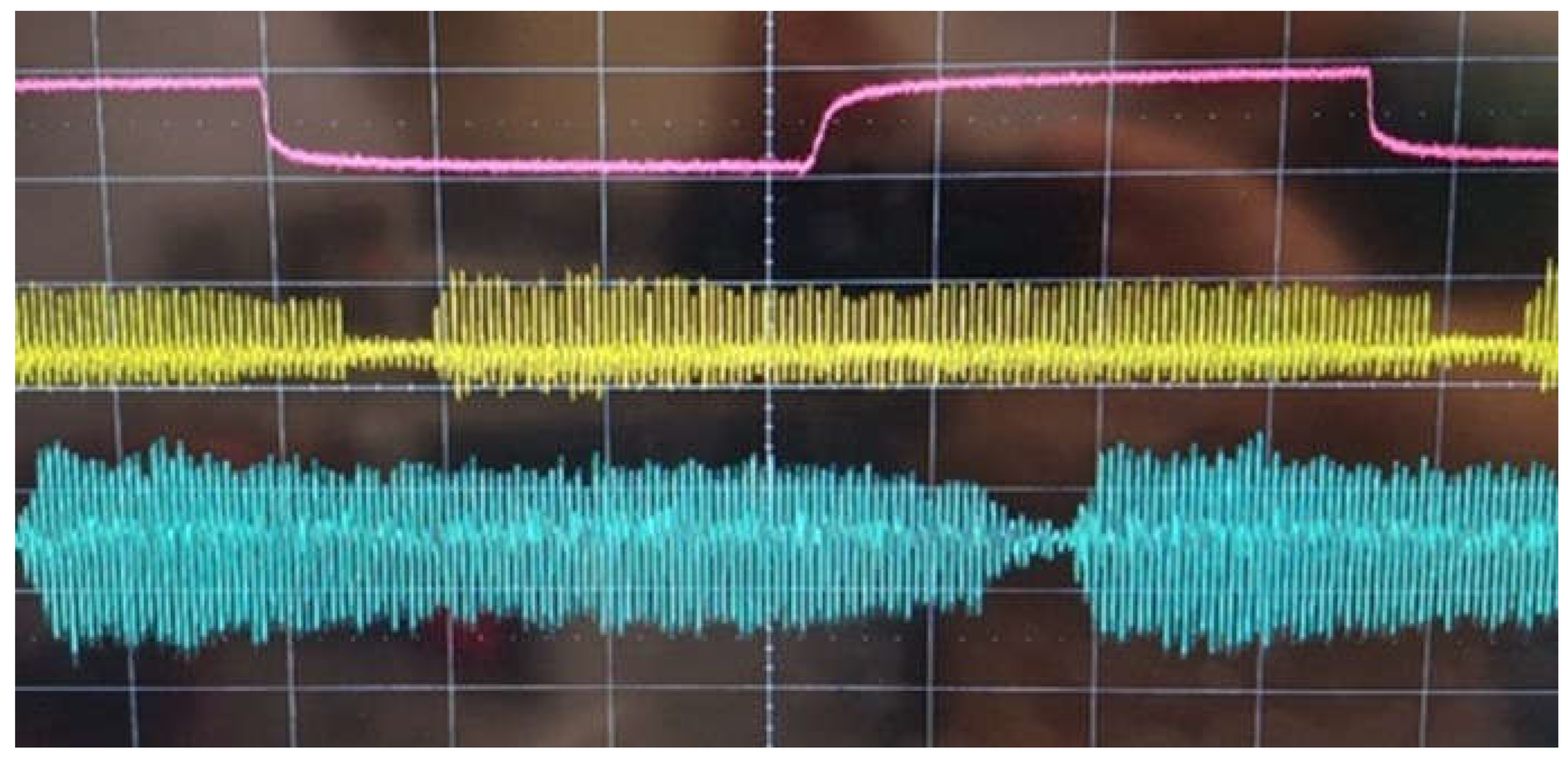

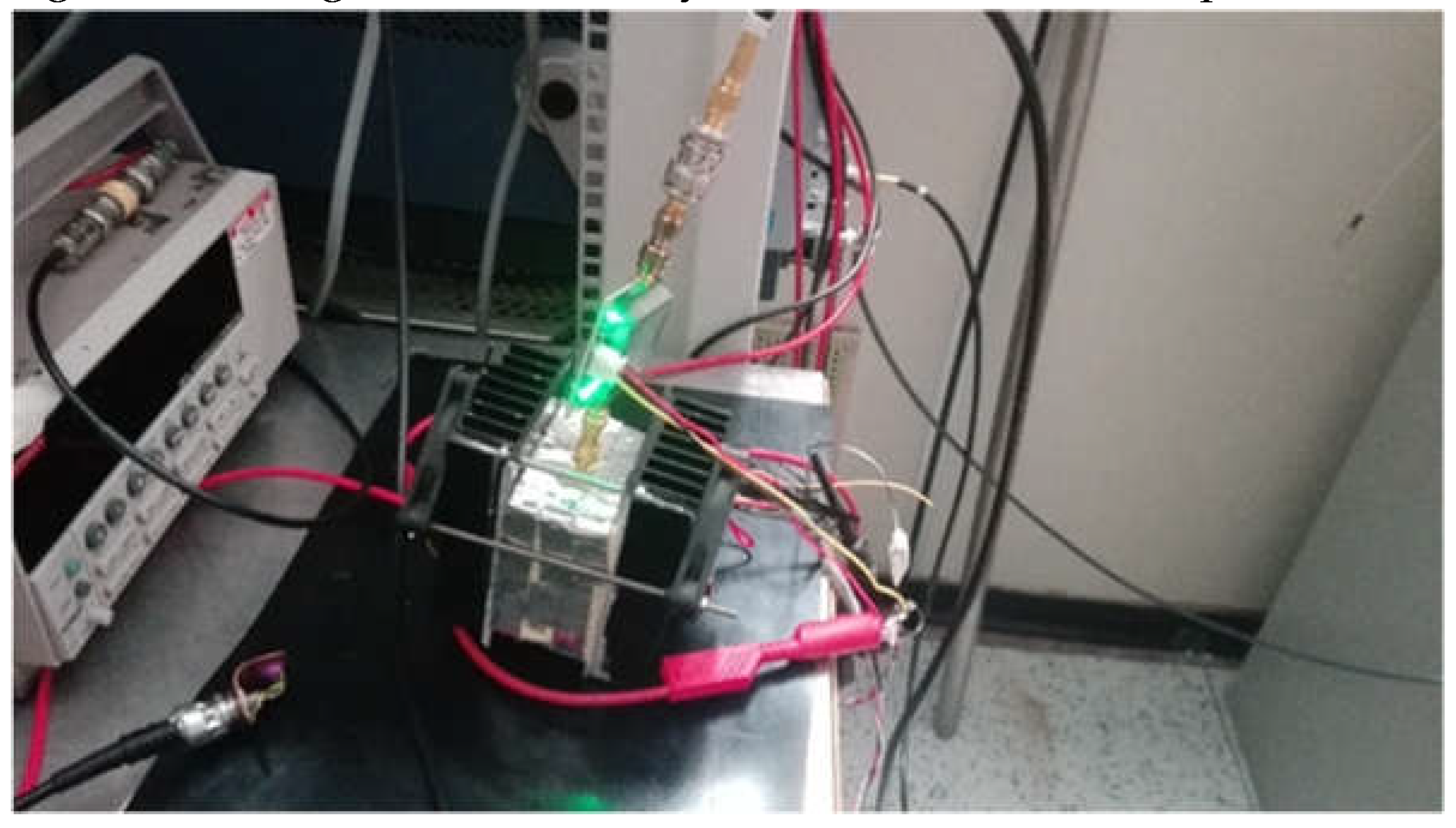

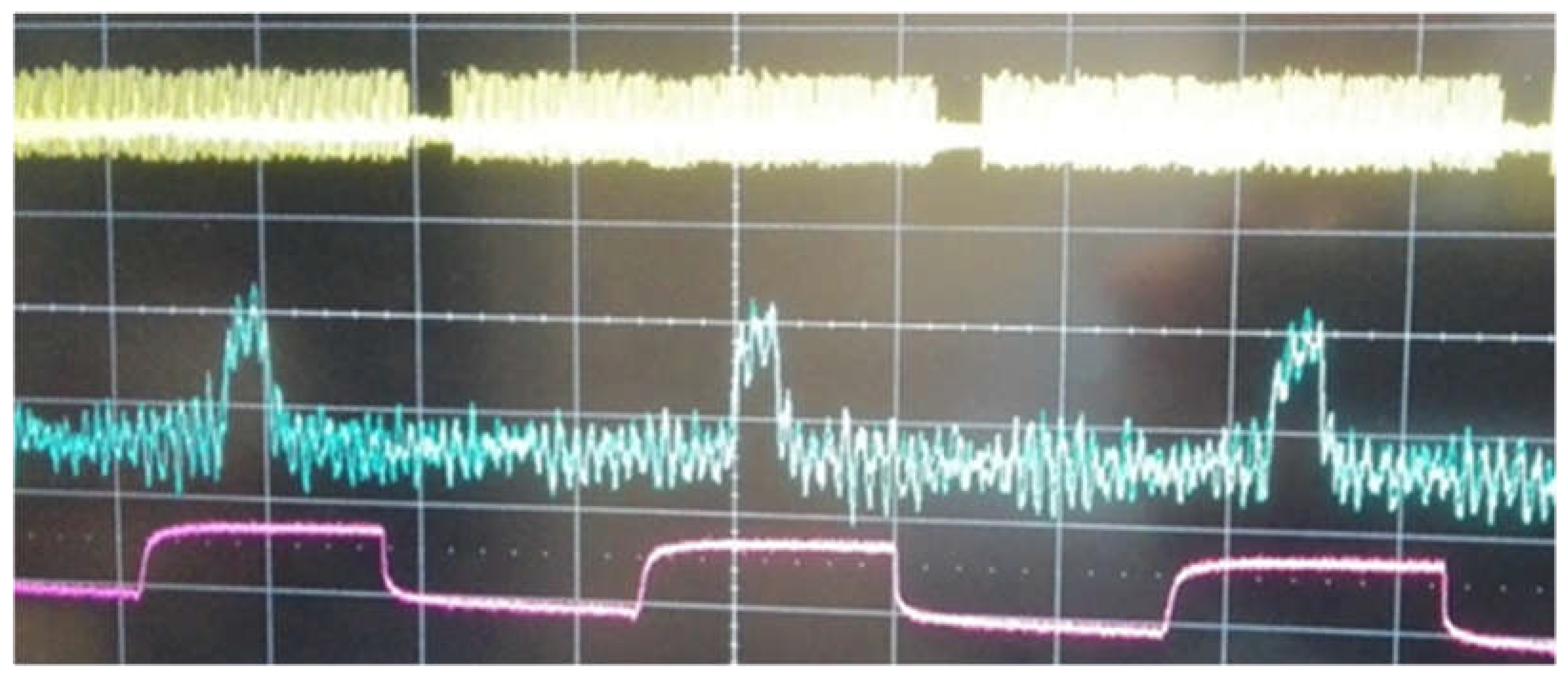

4.1.1. Test Done at SINBAD

4.1.2. Performance of HgCdTe Detectors

4.1.3. Performance of InAsSb Detector

4.2. Data Acquisition System

4.3. Trigger Module

4.3.1. Trigger Module Design

- The machine master clock from the accelerator timing system during the data taking at the infrared beamline.

- The sync output from a pulse generator in case of signal simulation.

- Forced manually by the operator command.

- A trigger threshold level selected by the operator.

- A smart automatic trigger generated by the astronomical signal or by a comparison between the astronomical signal and the dark signal. It can be implemented in different ways that are discussed below. Basically the software module must be designed to calculate a movable threshold level that, when exceeded, enables the trigger for data acquisition.

- A manual trigger forced by a command of the operator.

- An external trigger coming from other astronomical systems operating for multi-messenger astronomy.

- A self-diagnostics trigger via a pulse generator for testing purposes.

- fixed data length based on the operator choice;

- data record length limit based on technological considerations about the available data memory;

- threshold comparison of the input value based on a percentage of threshold trigger.

4.3.2. Trigger Simulator

- Select the trigger threshold value manually by operator.

- If the A signal is > threshold start the recording of the acquisition.

- Every time slot, compute the D signal background average.

- Applying a gain factor to the D signal average obtaining the trigger threshold. The gain should be evaluated by the operator, by default is 1. The gain factor shall take care of the possible hardware discrepancy of the semiconductors.

- If the A signal is > threshold start the recording of the acquisition.

|

>> trigger **** Trigger simulator program **** Trigger type [1 2 3 4] ? 2 trigger_type = 2 How many loops for simulation ? 10 n_loop = 10 **** Trigger type 2 **** Gain factor [0:10] ? 3 gain_factor = 3 Astronomical_value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 10 Dark_signal__value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 50 Astronomical_value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 150 Dark_signal__value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 40 *********************************************************** *************** Trigger program result ******************** acquisition_time = 2024-10-18-19-2-57 trigger_type = 2 threshold = 32.100 Trigger on >>> Start acquisition ***************** end trigger program ******************** *********************************************************** >> |

- very second, compute the A and D background average or fit in the last second.

- Make the average of the last 5 fits for both A and D inputs.

- Evaluate the difference between A and D averaged background.

- Applying a gain factor [0:2] to the difference result obtaining the trigger threshold. The gain should be evaluated by the operator, by default is 1. The gain factor has to take care of the possible hardware discrepancy of the semiconductor.

- If the A signal is > threshold start the recording of the acquisition.

|

>> trigger **** Trigger simulator program **** Trigger type [1 2 3 4] ? 3 trigger_type = 3 How many loops for simulation ? 5 n_loop = 5 **** Trigger type 3 **** Gain factor [1:100] ? 10 gain_factor = 10 Astronomical_value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 33 Dark_signal__value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 22 *********************************************************** *************** Trigger program result ******************** acquisition_time = 2024-8-6-16-40-33 trigger_type = 3 threshold = 12.100 Trigger on >>> Start acquisition ***************** end trigger program ********************* *********************************************************** >> |

- Every time slot, compute the D background average.

- Add a delta value [0:2] to the D average obtaining the trigger threshold.

- If the A signal is > threshold start the recording of the acquisition.

|

>> trigger **** Trigger simulator program **** Trigger type [1 2 3 4] ? 4 trigger_type = 4 How many loops for simulation ? 5 n_loop = 5 **** Trigger type 4 **** Difference DELTA [0:10] ? 0 delta_factor = 0 Astronomical_value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 44 Dark_signal__value [range 0:(adc_range-1) ]? 55 *********************************************************** *************** Trigger program result ******************** acquisition_time = 2024-8-6-16-43-60 trigger_type = 4 threshold = 10.450 Trigger on >>> Start acquisition ***************** end trigger program ********************* *********************************************************** >> |

4.4. Pattern Recognition Software for Transient Classification

4.4.1. Fast IR Burst Emulation

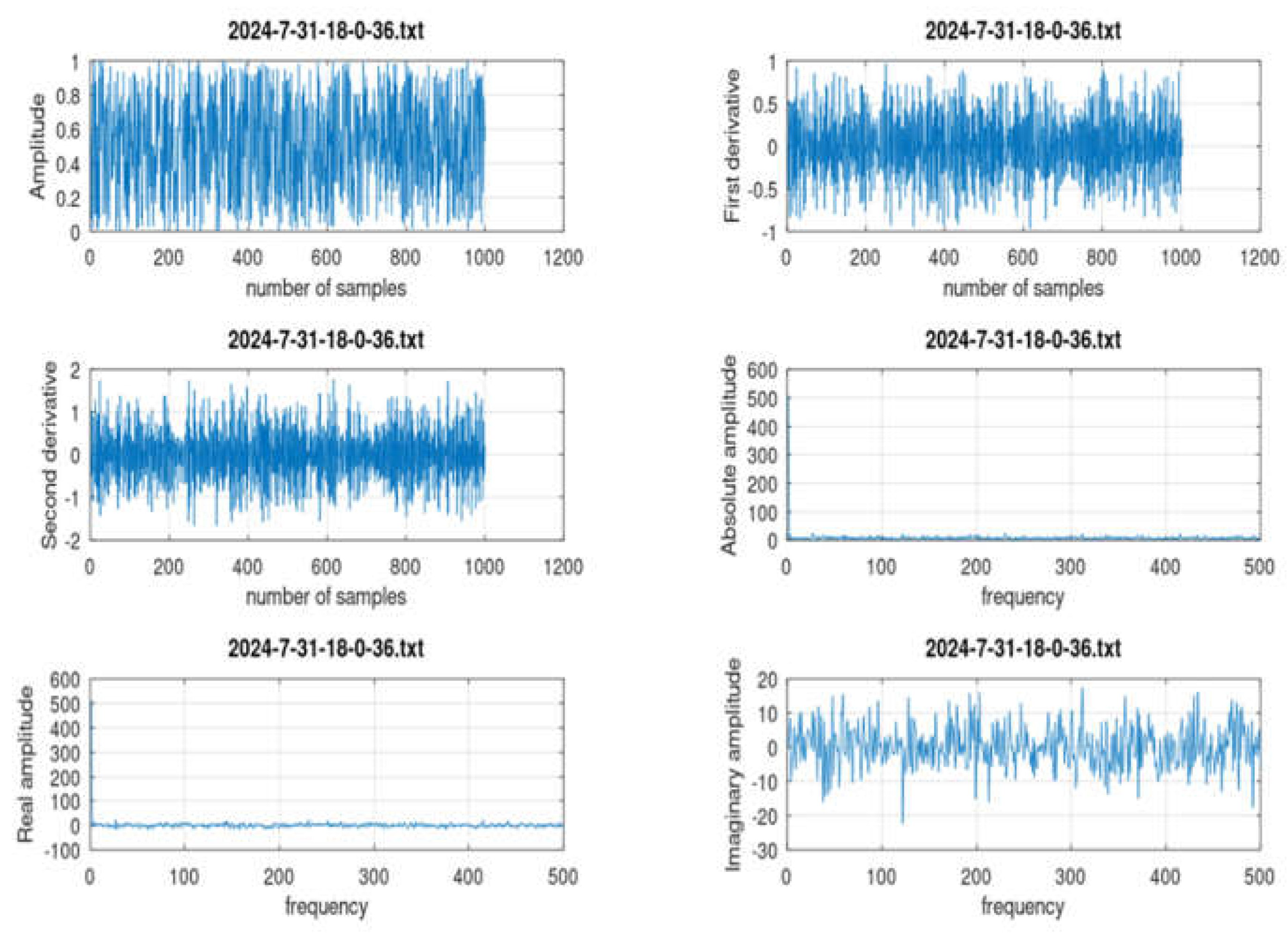

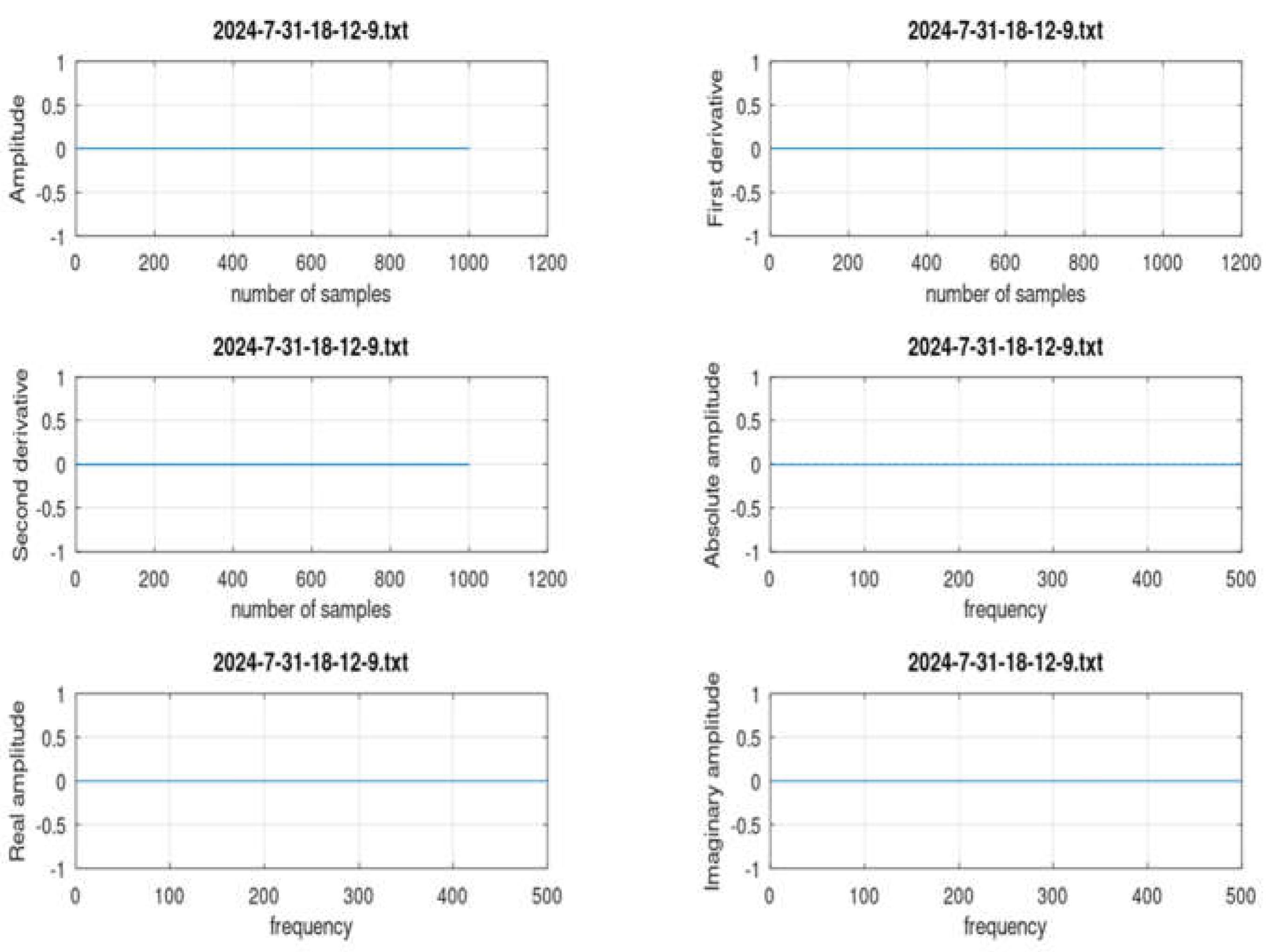

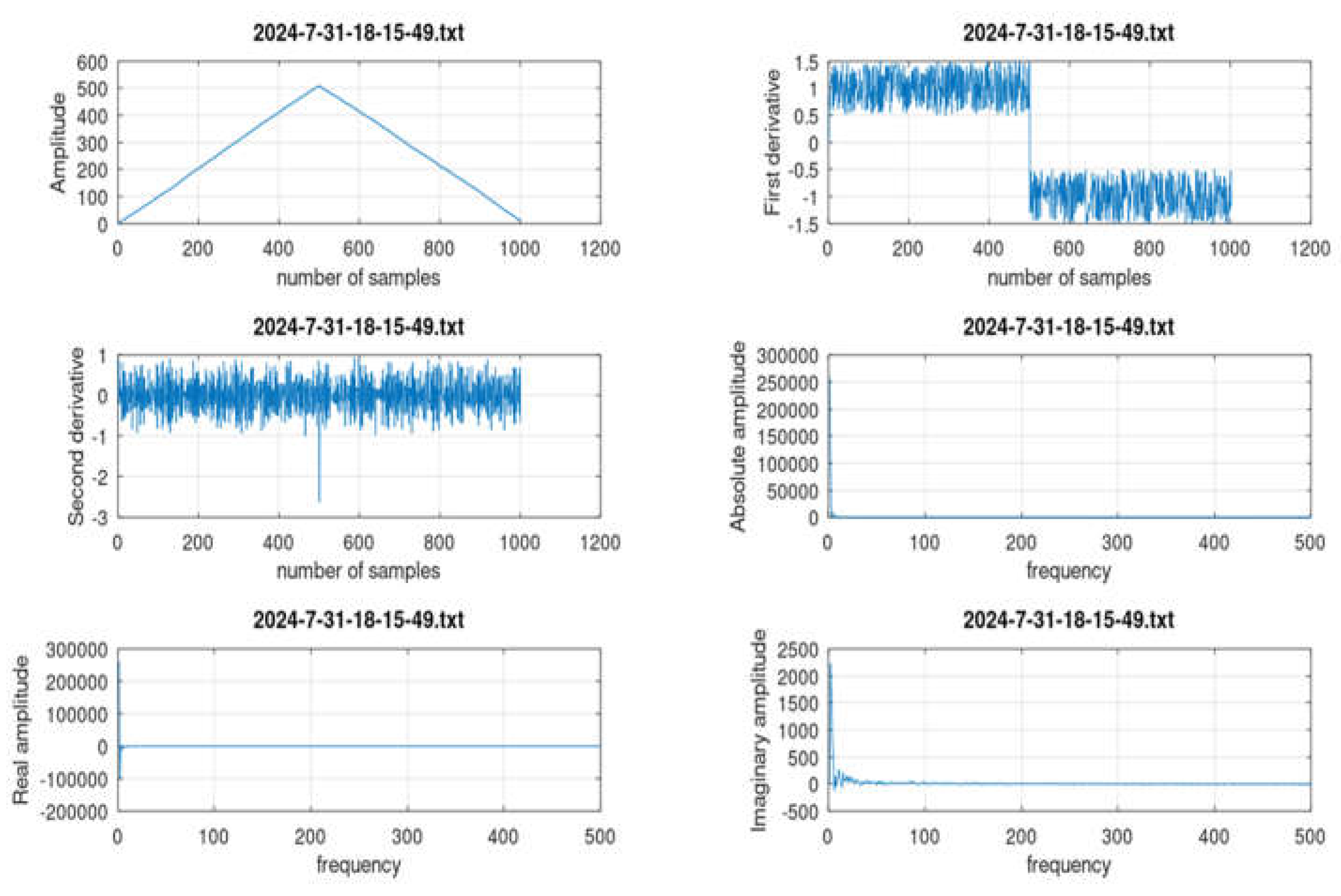

4.4.2. Fast IR Burst Classification

- Ask the operator for the file name and read the selected record from the data base evaluating any possible format error. If the data format is correct, go to the next point.

- Make a general analysis of the data of each transient presenting a visual inspection in time domain and in frequency domain.

- Classify the transient in base at the amplitude and the growth rate.

|

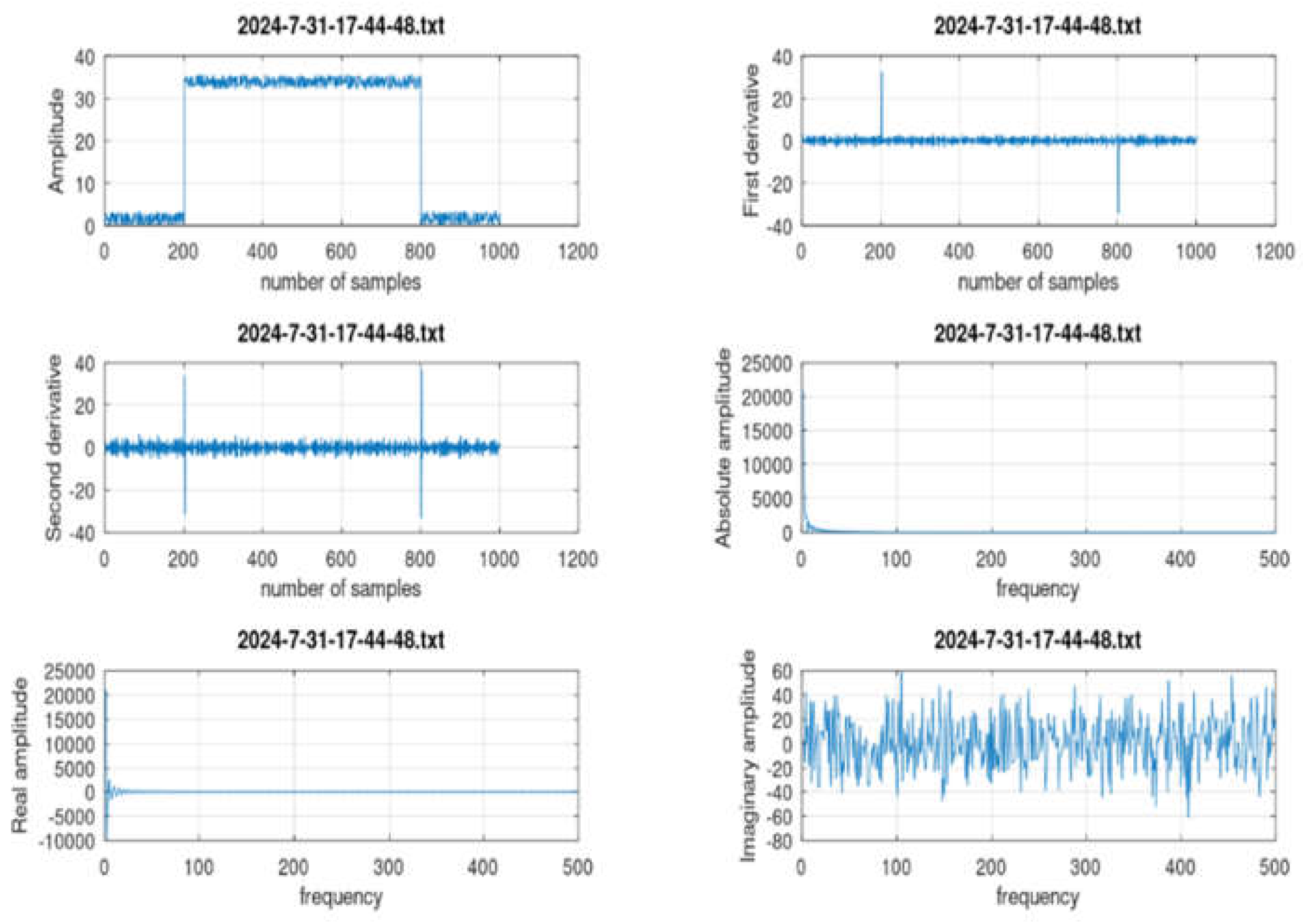

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** Single transient found! Compute growth rate (%) growth_rate = 91.035 Class: Very fast transient or exponential growth Transient_amplitude_mV = 30.325 >> |

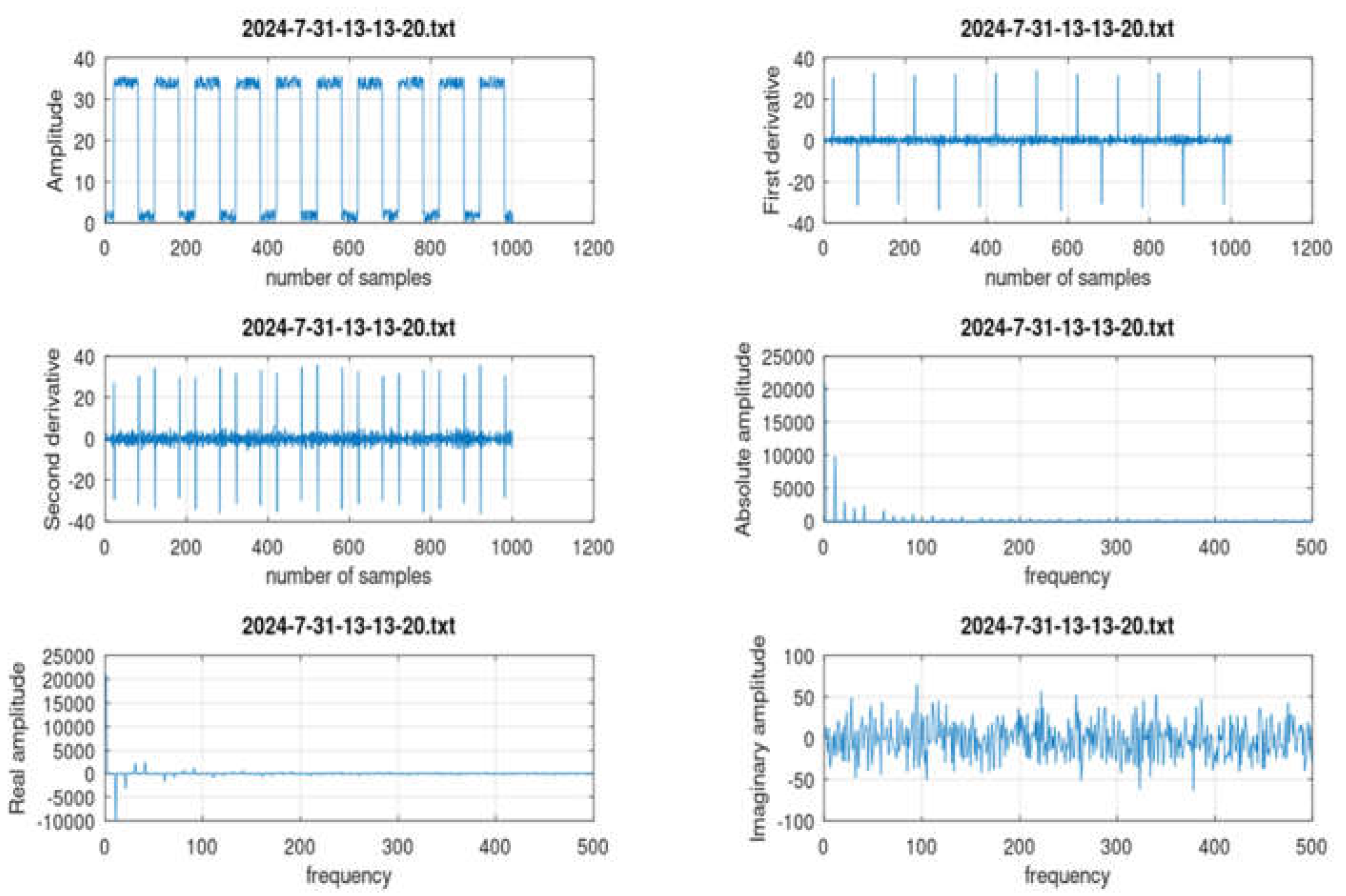

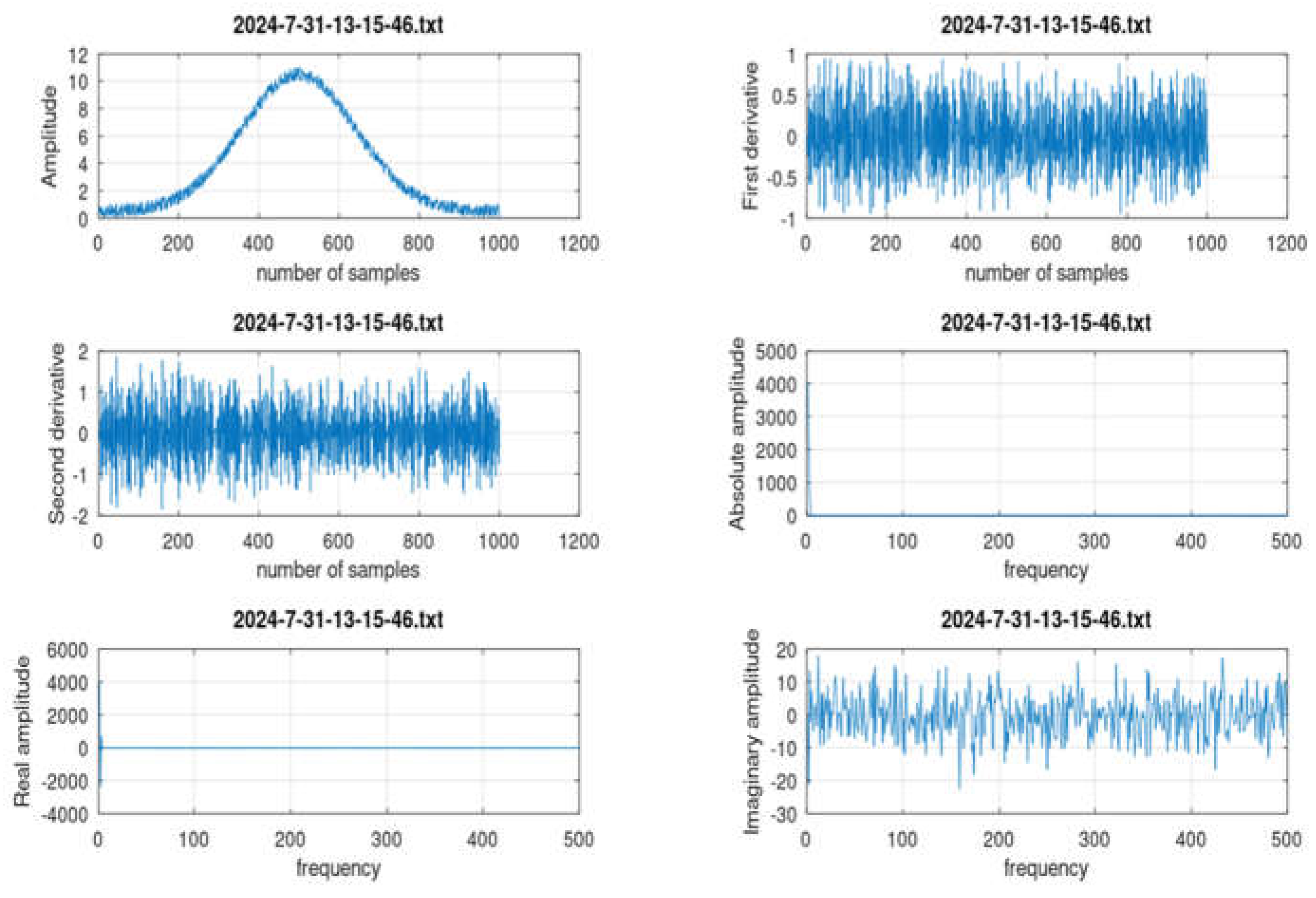

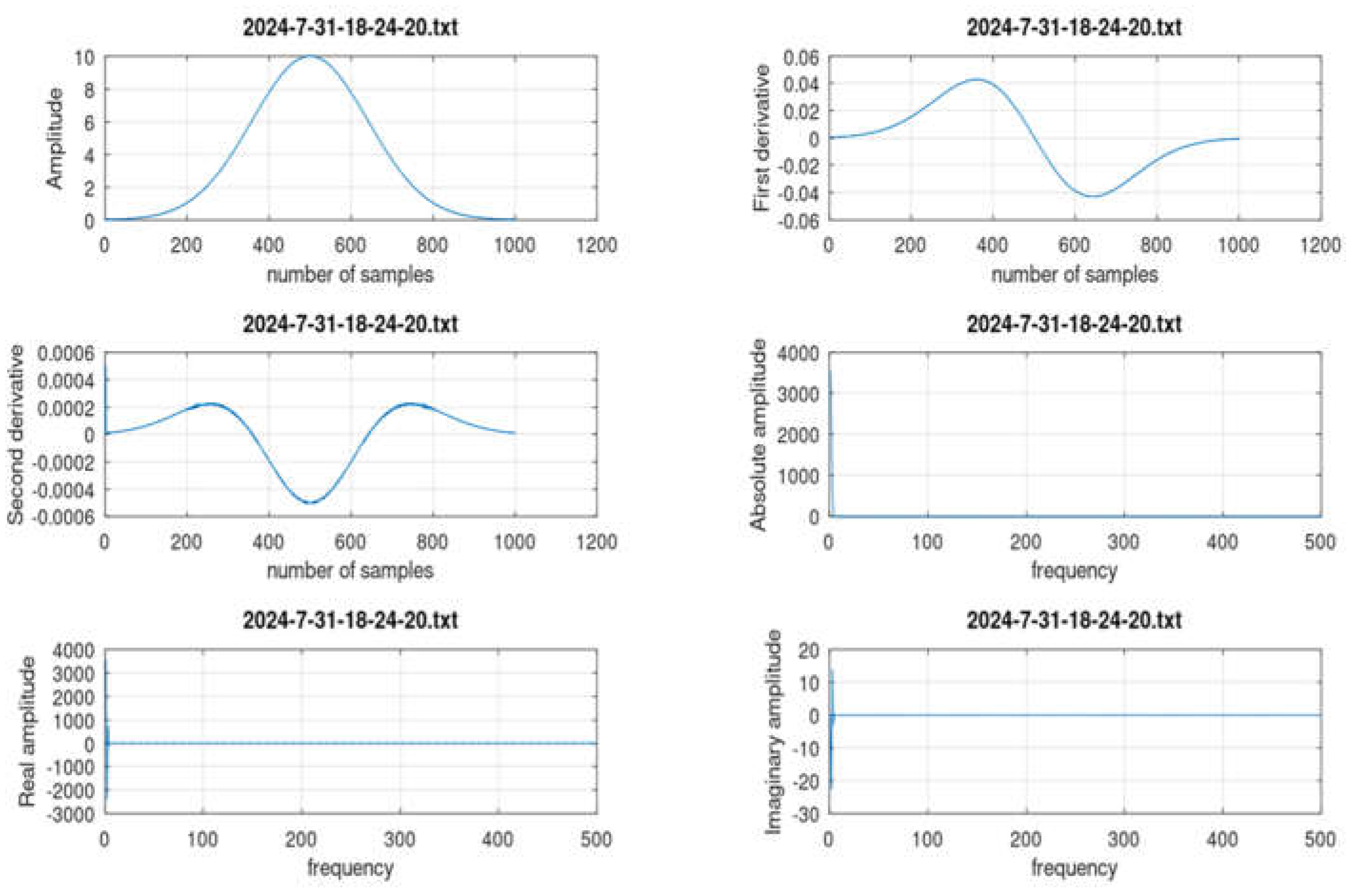

- subtract the value x from the value x+1 (that corresponds to xprime), this corresponds to the derivative of x because Δt=1, then take the maximum value;

- divide the results by the maximum value of x;

- to turn that into a percent increase, multiply the results by 100.

- See the formula (3):

|

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** Pulse train found! num_of_pulses = 10 Compute growth rate (%) growth_rate = 95.842 Class: Very fast transient or exponential growth Transient_amplitude_mV = 30.329 >> |

|

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** Single transient found! Compute growth rate (%) growth_rate = 8.5435 Class: Fast transient Transient_amplitude_mV = 5.8689 >> |

|

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** Single transient found! Compute growth rate (%) growth_rate = 0.4289 Class: Slow growth rate or gaussian shape Transient_amplitude_mV = 4.8800 >> |

|

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** No signal >> |

|

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** No signal >> |

|

>> firb_classifier **** Astrophysical Fast IR Transient Classifier **** 2024-7-31-13-13-20.txt 2024-7-31-17-44-48.txt 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt 2024-7-31-13-15-46.txt 2024-7-31-18-0-36.txt 2024-7-31-18-22-27.txt 2024-7-31-13-44-56.txt 2024-7-31-18-12-9.txt 2024-7-31-18-24-20.txt Pick a file: 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt filename_in = 2024-7-31-18-15-49.txt ******** CLASSIFICATION *********************** Single transient found! Compute growth rate (%) growth_rate = 0.2940 Class: Very Slow growth rate or triangular shape Transient_amplitude_mV = 504.75 >> |

4.5. Noise Cancelling Approach

4.6. Artificial Neural Network

4.7. Flow Chart of the Software Modules

5. Discussion

5.1. The Project FAIRTEL

- a reflecting ground-based telescope (Cassegrain or Ritchey-Chrétien) having a main mirror with a minimum diameter of 400 mm, and dedicated to the experiment for enough long period of time;

- an infrared time resolved detector given by just one “A” astronomical pixel (or, in alternative, seven “A” pixels in parallel), able to acquire fast signals with rise time of the order of 1 ns and based on diagnostics developed for lepton storage rings; the detector will be put in the focal plane of the telescope to convert mid-IR light to electric analog signals; one “D” pixel (or, in alternative, up to 12 pixels in parallel) are also foreseen for detecting the background;

- analog circuits (bias-tee, printed circuit board to put in parallel 7 A + 12 D detectors, and amplifiers to have a gain of 80dB) to adapt the analog signal to the digital acquisition system;

- a digital acquisition system sampling at 4 GSamples/s and storing data when enabled by the trigger module; to have a good dynamic range, conversion from analog to digital by using 12/14/16 bits is required;

- a module with different types of triggers generated automatically by a dedicated real-time module to record only interesting events without the need of operator intervention and to avoid overloading the data base memory;

- off-line programs for data evaluation and classification by implementing pattern recognition (PR) capability from artificial intelligence (AI) techniques. This is to analyze and classify the records in the data base, helping the human operators. A program emulating the possible transients to test the classifier performance, has been developed and used to generate a data base of possible shapes of the Fast InfraRed Bursts (firb_classifier.m, in Appendix C). The FIRB classifier has been developed by using an approach derived from the beam diagnostics for fast instabilities in lepton storage rings. The transient classification is done by displaying the signal shape in time domain with first and second derivatives, as well as in frequency domain, and measuring growth rate and amplitude of transients.

- NASA Infrared Telescope Facility (NASA IRTF), located at Mauna Kea, Hawaii;

- TNG (Telescopio Nazionale Galileo), Italian facility located at the top of the Roque de Los Muchachos Observatory in the Canarian island of La Palma;

- Gornergrat Infrared Telescope (TIRGO), near Zermatt, in Switzerland, that is dismissed but that it could be perhaps reactivated.

5.2. Which Astronomical Objects of Interest

5.2.1. Solar System

5.2.2. Milky Way

- Galactic center and Sgr A* black hole: infrared observations were proposed by Moroz [183], see also in [184]. Constellation: Sagittarius. Epoch J2000.0 Position determined by the Hipparcos satellite in Equatorial Coordinates: Right Ascension (RA) 17h 45m 40.0409s Declination (DEC) −29° 0′ 28.118″. Distance 25,900 ± 1,400 ly. The galactic coordinates of Sgr A* are latitude b=+0° 07′ 12″ south, longitude l=0° 04′ 06″.

- Magnetar PSR J1745−2900 (Galactic center) presents an interesting frequency structure [185,186]. There is 0.1 pc separation between PSR J1745−2900 and Sgr A* (identifying Sgr A* with the center of the dark matter distribution). Constellation: Sagittarius. Epoch J2000.0 RA 17h 45m 40.16s. DEC −29° 00' 29.8"

- FRB 200428, the first ever detected FRB inside the Milky Way, in the Vulpecula constellation. RA 19h 35m DEC: +21° 54′ Dispersion Measure 332.8 pc cm-3. The distance from Sun is about 30k ly. It is the first ever linked to a known source: the magnetar SGR 1935+2154. The link strongly supports the hypothesis that fast radio bursts emanate from magnetars.

- Cygnus-X is a massive star formation region located in the constellation of Cygnus at a distance from the Sun of 1.4 kiloparsecs (4,600 light years). It is located behind the Cygnus Rift. Epoch J2000.0 RA 20h 20m 4.8s DEC +40° 51’36” Galactic coordinates l=79° 30' 15.8”; b=+1° 00' 2.1”

- The Crab Pulsar (PSR B0531+21 or Baade's Star) is a relatively young neutron star. The star is the central star in the Crab Nebula (IR observations by Moroz [187,188]). Discovered in 1968, the pulsar was the first to be connected with a supernova remnant. The Crab pulsar is a singular source in our Galaxy. The Crab HFIPs (high-frequency inter-pulse) are microseconds in duration. Furthermore, the Crab Pulsar is one of few pulsars to be identified optically. Constellation: Taurus. Epoch J2000.0. RA 05h 34m 31.95s. DEC +22° 00′ 52.2″

- Orion nebula (M42): this stellar nursery is less than 1400 light-years away, making it the closest large star-forming region to Earth and giving it a relatively bright apparent magnitude of 4 (infrared observations by Moroz [189]). Eq. Coordinates [J2000.0] RA 5h 35m 15,99s DEC -5º 23’31.0” Galactic coordinates: l=+209º 0’ 42.9” b=-19º23’12.6”

- Cassiopeia A (or SN 1671) is a supernova remnant in Cassiopeia constellation and the brightest extrasolar radio source in the sky at frequencies above 1 GHz. Epoch J2000.0 RA 23h 23m 24s DEC +58° 48.9′ Galactic coordinates l=111.734745°, b=−02.129570°. Distance 11,000 ly. Last news (2024/7/15) from JWST confirm the interest of CAS A, in fact JWST unveils stunning ejecta and CO structures in Cassiopeia A’s Young Supernova that provide insights into the conditions that lead to the formation and destruction of molecules and dust within supernova ejecta.

- Pulsar PSR B1257+12. Constellation: Virgo. Coordinates [J2000.0]: RA: 13h 00m 01s. DEC +12° 40′ 57″. The pulsar has a planetary system with three known pulsar planets, named "Draugr" (PSR B1257+12 b or PSR B1257+12 A), "Poltergeist" (PSR B1257+12 c, or PSR B1257+12 B), and "Phobetor" (PSR B1257+12 d, or PSR B1257+12 C), respectively. They were both the first extrasolar planets and the first pulsar planets to be discovered; B and C in 1992 and A in 1994.

- ASKAP J1935+2148, a neutron star or magnetar having a rotation period of 53.8 minutes, approximately 15,800 light-years away. Constellation Vulpecula. Epoch J2000.0 RA 19h 35m 5.126s DEC 21° 48′ 41.047″

- WASP-107 b’s giant radius, extended atmosphere, and edge-on orbit make it ideal for transmission spectroscopy, a method used to identify the various gases in an exoplanet atmosphere based on how they affect starlight. Combining observations from Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) [190], and Hubble’s WFC3 (Wide Field Camera 3), Welbanks’s team was able to build a broad spectrum of 0.8- to 12.2-micron light absorbed by WASP-107 b’s atmosphere, from ESA, weic2414 Science Release [191]. Using Webb’s NIRSpec (Near-Infrared Spectrograph), Sing’s team built an independent spectrum covering 2.7 to 5.2 micron. Distance from Sun: 200 ly. Constellation: Virgo. Coordinates [J2000.0]. RA 12h 33m 32.848s DEC -10° 08′ 46.14″

- Magnetar 1E 1547.0-5408 (PSR J1550-5418): X-ray, infrared and radio observations of the field centered on X-ray source located in the Galactic Plane [192]. Distance of 9 kpc [65]. A near-infrared observation of this field shows a source with magnitude Ks = 15.9±0.2 near the position of 1E 1547.0–5408, but the implied X-ray to infrared flux ratio indicates the infrared emission is most likely from an unrelated field source, allowing us to limit the IR magnitude of any counterpart to 1E 1547.0–5408 to >17.5. Constellation: Norma. RA 15h 47m DEC -54º 08” (Southern hemisphere).

- The Vela Pulsar (PSR J0835-4510 or PSR B0833-45) is a radio, optical, X-ray- and gamma-emitting pulsar associated with the Vela Supernova Remnant in the constellation of Vela. Its parent Type II supernova exploded approximately 11,000–12,300 years ago (and it was about 800 light-years away). Observation data: Epoch J2000.0, Constellation Vela, RA 08h 35m 20.65525s, DEC −45° 10′ 35.1545″ (southern hemisphere).

- Puppis A (Pup A) is a supernova remnant about 100 light-years in diameter and roughly 6500–7000 light-years distant. The supernova explosion reached Earth approximately 3700 years ago. Although it overlaps the Vela Supernova Remnant, it is four times more distant. A hypervelocity neutron star known as the Cosmic Cannonball has been found in this SNR. Constellation Puppis. RA 08h 24m 07s DEC -42° 59' 48 (Epoch J2000.0). Galactic coordinates l = 260.2°, b = -3.7°. It is in the southern hemisphere.

- Geminga: TeV haloes were serendipitously discovered in 2017 by the High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory (HAWC). The HAWC collaboration reported the detection of Very High Energy (VHE, > 0.1 TeV) gamma-ray emission, at photon energy in the range 8–40 TeV, in coincidence with the nearby middle-aged pulsars Geminga and PSR B0656+14. Around each of the two pulsars, both located at a distance of ∼ 300 pc, the emission was reported to extend for 20–30 pc [193]. Geminga is a gamma ray and x-ray pulsar source thought to be a neutron star approximately 250 parsecs (815 ly) from the Sun in the constellation Gemini. Observation data: Epoch J2000.0. Constellation: Gemini. RA 06h 33m 54.15s DEC +17° 46′ 12.9″ Apparent magnitude (V) 25.5. PSR J0659+1414 is a neutron star located at 288 pc from the Sun. [194].

5.2.3. Extragalactic Objects

- FRB 121102’s host galaxy [197] turned out to be a low-metallicity, low-mass dwarf [27]. It produces repetitive signals [198,199]. Given that such galaxies are also known to be the common hosts of super luminous supernovae (SLSNe) and long gamma-ray bursts (LGRBs), this presented a tantalizing possible link between FRBs and these other types of extreme astrophysical transients [200,201]. Deeper observations of the host using the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) revealed that FRB121102 is coincident with an intense star-forming region [202]. A precise sub-arcsecond localization (∼100 mas precision) of FRB 121102 using the Very Large Array has been achieved, too [203]. Constellation: Auriga. Epoch J2000.0. Equatorial coordinates RA 05h 32m 09.44697s DEC +33° 05’ 17.9356”. Galactic coordinates: longitude and latitude: l=174,95°, b = -0,223°

- FRB 110214 has one of the lowest DMs (168.8 pc cm-3) of the entire FRB sample to-date. There was a bright galaxy in the innermost localization region of FRB 110214, the elliptical galaxy FRL 692 at z ~ 0.025 [204]. The burst was centered at RA 01h 21m 17s, DEC = -49° 47’ 11”, in the southern hemisphere, corresponding to a Galactic longitude and latitude l=290.7º, b=-66.6º . Constellation: Phoenix.

- A survey on other known extragalactic sources of FRB will be of interest.

- M87* black hole: Constellation: Virgo. RA 12h 30m 49.42338s. DEC +12° 23′ 28.0439″. The discovery of FRBs as an observational class has also prompted re-examination of previously published transient surveys such as the reported discovery of highly dispersed radio pulses from M87 in the Virgo cluster in 1980 [205] and the 1989 sky survey with the Molonglo Observatory Synthesis Telescope by Amy et al. [206], which discovered an excess of non-terrestrial short-duration bursts (1 µs to 1 ms) in 4000 h of observations [27].

- Cygnus A (3C 405) is a radio galaxy, one of the strongest radio sources in the sky. Like all radio galaxies, it contains an active galactic nucleus. Constellation: Cygnus. RA 19h 59m 28.3566s DEC +40° 44′ 02.096″ Redshift 0.056075 ± 0.000067. Distance 232 Mpc (760 million ly). Apparent magnitude (V) 16.22.

6. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

References

- 1.Abbott, Benjamin P. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration). Observing gravitational-wave transient GW150914 with minimal assumptions. Phys. Rev. 2016, 93, 122004; Erratum Phys. Rev. 2016 D 94, 069903. [CrossRef]

- 2.Abbott, Benjamin P. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration). Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger. Phys.Rev.Lett. 2016, 116, 061102. [CrossRef]

- 3.Abbott, Benjamin P. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration). Properties of the Binary Black Hole Merger GW150914. Phys.Rev.Lett. 2016, 116, 241102. [CrossRef]

- 4.Hirata, K. S. et al. Observation in the Kamiokande-II detector of the neutrino burst from supernova SN1987A. Phys. Rev. 1988, 38, 448. https://journals.aps.org/prd/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevD.38.448.

- 5.Abbott, Benjamin P. et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration). GW170817: Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Neutron Star Inspiral. Phys.Rev.Letters. 2017, 119, 161101.95. [CrossRef]

- 6.6. Omodei, N., Vianello, G., Kocevski, D., Buson, S., Di Lalla, N. Follow-up of Gravitational Wave Events with the Fermi-LAT. In Proc. of Science (IFS2017) 059. Status and Prospects for the Future. 7th Fermi Symposium 2017. Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. 15-20 October 2017.

- 7.Abbott, Benjamin P. et al. (LIGO, Virgo and other collaborations). “Multi-messenger Observations of a Binary Neutron Star Merger”. Astroph. Journ. 2017 848 (2): L12. arXiv:1710.05833. [CrossRef]

- 8.Lorimer, Duncan (West Virginia University, USA), Bailes, Matthew (Swinburne University), McLaughlin, Maura (West Virginia University, USA), Narkevic, David (West Virginia University, US); et al. A bright millisecond radio burst of extragalactic origin. Australia Telescope National Facility. Science 2007, 318, 777-780. [CrossRef]

- 9.Popov, S. B.; Postnov, K. A.; Pshirkov, M. S. Fast radio bursts. Phys.-Usp. 2018, 61, 965. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3367/UFNe.2018.03.038313/pdf.

- 10.Hauser, Michael G.; Dwek, Eli. The Cosmic Infrared Background: Measurements and Implications. Ann. Rev. of Astronomy and Astrophysics, 2001, 39, 249-307 . [CrossRef]

- 11.Helou G. In The Interpretation of Modern Synthesis Observations of Spiral Galaxies, ed. N Duric, PC Crane, San Francisco, USA. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2001, 275, 125–33.

- 12.Coppin, Paul; de Vries, Krijn D.; van Eijndhoven, Nick. Gamma-ray burst precursors as observed by Fermi-GBM. Proc. of 37th International Cosmic Ray Conference (ICRC21), Berlin, Germany, 12–23 July 2021. https://inspirehep.net/files/3386ba3451f103806b9e213e7a52fb9b.

- 13.Carson, Jennifer. GLAST: physics goals and instrument status. J.Phys.Conf.Ser. 2007, 60, 115-118. [CrossRef]

- 14.Atwood W. B. et al. The Large Area Telescope on the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope Mission. Astrophys. J. 2009, 697, 1071-1102. [CrossRef]

- 15.Caputo, R. UCSC (on behalf of the Fermi-LAT Collaboration). Latest Results with the Fermi-LAT. In Proc. of the CosPA 2016, Sydney, Australia.

- 16.Chiaro G., Meyer, M., Alvarez Crespo, N., Britto, R.J., Marais, J.P., van Soelen, B., Salvetti, D., La Mura, D., Thompson, D.J.. Hunting misaligned radio-loud AGN (MAGN) candidates among the uncertain γ-ray sources of the third Fermi-LAT Catalogue. astro-ph arXiv, 2018, 1808.05881. https://arxiv.org/abs/1808.05881.

- 17.Ajello, M. et al.. FERMI-LAT Observations of High-Energy γ-Ray Emission toward the Galactic Center. Astrophys. J. 2016, 819, 44. [CrossRef]

- 18.Bissaldi, Elisabetta et al.. High-redshift Gamma-Ray Burst Studies with GLAST. In Gamma-Ray Bursts: Prospects for GLAST (M. Axelsson and F. Ryde, eds.), American Institute of Physics Conf. Proc. 2007, 906, 79–88. [CrossRef]

- 19.FERMIGBRST - Fermi GBM Burst Catalog. Available online : http://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/W3Browse/fermi/fermigbrst.html.

- 20.Abbott, Benjamin et al.. Implications for the Origin of GRB 070201 from LIGO Observations. Astrophys. J. 2008, 681, 1419. [CrossRef]

- 21.Rovelli, Carlo; Vidotto, Francesca. Planck Stars. arXiv 2014 1401.6562. https://arxiv.org/abs/1401.6562.

- 22.Barrau, Aurelian; Rovelli, Carlo. “Planck star phenomenology”. arXiv 2014 1404.5821 pp. 5. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1404.5821.pdf.

- 23.Bissaldi, Elisabetta. Multi-messenger studies with the Fermi Satellite. In Proc. of Neutrino Oscillation Workshop 2018, NOW2018, Rosa Marina (Ostuni, Italy), September 9-16, 2018. https://home.ba.infn.it/~now/now2018/ https://home.ba.infn.it/~now/now2018/assets/bissaldi_now2018.pdf.

- 24.Bissaldi, Elisabetta. Probing Gamma-Ray Burst physics through high-energy observations: Current results and future perspectives. L'Aquila Joint Astroparticle Colloquium, GSSI, February 1st, 2023.

- 25.Mohon, Lee. GRB 150101B: A Distant Cousin to GW170817. NASA. Retrieved 17 October 2018. https://www.nasa.gov/image-article/grb-150101b-distant-cousin-gw170817/.

- 26.Platts, Emma. Computational analysis techniques using fast radio bursts to probe astrophysics. Doctoral Thesis. University of Cape Town, Faculty of Science, Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics. Cape Town, South-Africa. 2012. http://hdl.handle.net/11427/33921.

- 27.Petroff, E., Hessels, J. W. T., Lorimer, D. R.. Fast radio bursts. Astron. and Astrophys. Rev. 2019 27:4. [CrossRef]

- 28.Michilli D., et al. An extreme magneto-ionic environment associated with the fast radio burst source FRB 121102. Nature 2018, 553, 182–185.

- 29.Tendulkar S.P., et al. The host galaxy and redshift of the repeating fast radio burst FRB 121102. Astrophys. J. 2017, 834, L7. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/834/2/L7.

- 30.Rane, A.; Lorimer, D. Fast Radio Bursts. J Astrophys Astron 2017, 38, 55. [CrossRef]

- 31.Mottez, F.; Zarka, P. Radio emissions from pulsar companions: a refutable explanation for galactic transients and fast radio bursts. A&A 2014, 569, 11. [CrossRef]

- 32.Scholz, P. et al. Simultaneous X-ray, gamma-ray, and radio observations of the repeating fast radio burst FRB 121102. Astrophys. J. 2017, 846, 80.

- 33.Hardy L.K.; Dhillon V.S.; Spitler L.G.; Littlefair S.P.; Ashley R.P.; De Cia A.; Green M.J.; Jaroenjittichai P.; Keane E.F.; Kerry P.; Kramer M.; Malesani D.; Marsh T.R.; Parsons S.G.; Possenti A.; Rattanasoon S.; Sahman D.I. A search for optical bursts from the repeating fast radio burst FRB 121102. MNRAS 2017, 472, 2800–2807.

- 34.CHIME/FRB Collaboration. A second source of repeating fast radio bursts. Nature 2019 566 (7743): 235–238. arXiv:1901.04525. [CrossRef]

- 35.Zhang, Bin-Bin; Zhang, Bing. Repeating FRB 121102: Eight-year Fermi-LAT Upper Limits and Implications. Astrophys. J. Letters, 2017, 843, L13. DOI : https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/aa7633/meta.

- 36.Caleb, M., Lenc, E., Kaplan, D.L. et al. An emission-state-switching radio transient with a 54-minute period. Nat. Astron. 8 2024 1159–1168 (2024). [CrossRef]

- 37.Farah, W. et al. FRB microstructure revealed by the real-time detection of FRB170827. MNRAS 2018, 478, 1209–1217. [CrossRef]

- 38.Burgay, Marta. Fast Radio Bursts - Mysterious Probes of the Universe. Talk for the GSSI Astroparticle Colloquia, L'Aquila, 2020/11/18.

- 39.Haggard, Hal; Rovelli. Black Hole Fireworks: Quantum-gravity Effects Outside the Horizon Spark Black to White Tunnelling. Physical Review D, 2015, 92, 104020. https://arXiv.org/abs/1407.0989.

- 40.Thornton, D.; Burgay, M. et al. A Population of Fast Radio Bursts at Cosmological Distances. Science, 5 Jul 2013, 341, 53-56. [CrossRef]

- 41.Kashiyama, K.; Ioka, K.; Mészáros, P. Cosmological Fast Radio Bursts from Binary White Dwarf Mergers. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2013, 776, L39. [CrossRef]

- 42.Keane, E.F.; Stappers, B. W.; Kramer, M.; Lyne, A.G. On the origin of a highly dispersed coherent radio burst. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012 425, L71–L75. [CrossRef]

- 43.Totani, Tomonori. Cosmological Fast Radio Bursts from Binary Neutron Star Mergers. Astronom. Soc. of Japan, 2013, 65, 5, L12. [CrossRef]

- 44.Iwazaki, Aiichi. Fast Radio Bursts from Axion Stars. High Energy Physics – Phenomenology hep-ph https://arxiv.org/abs/1412.7825 [last rev. 17 Nov 2015 (v5)].

- 45.Tkachev, I.I. Fast radio bursts and axion miniclusters. Jetp Lett., 2015, 101, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- 46.Cao, Xiao-Feng; Yu, Yun-Wei. Superconducting cosmic string loops as sources for fast radio bursts. Phys. Rev. D, 2018, 97, 023022 . [CrossRef]

- 47.Yu, Yun-Wei; Cheng, Kwong-Sang; Shiu, Gary; Tye, Henry. Implications of fast radio bursts for superconducting cosmic strings. Journal of Cosmology and Astroparticle Physics, 2014, November 2014. JCAP11(2014)040 https://10.1088/1475-7516/2014/11/040.

- 48.Falcke, H.; Rezzolla, L. A&A 2014, 562, AA137.

- 49.Popov, S. B.; Postnov, K. A.; Pshirkov, M. S. Fast radio bursts. Phys.-Usp, 2018, 61, 965. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3367/UFNe.2018.03.038313/pdf.

- 50.Israel, G.L.; Burgay, M. et al. X-Ray and Radio Bursts from the Magnetar 1E 1547.0–5408. Astrophys. J., 2021, 907, 7. [CrossRef]

- 51.Cordes, J.M.; Wasserman, Ira. Supergiant pulses from extragalactic neutron stars”. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronom. Soc., 2016, 457, 1. Pages 232–257. [CrossRef]

- 52.Zhang, Bin-Bin; Zhang, Bing. Repeating FRB 121102: Eight-year Fermi-LAT Upper Limits and Implications. Astrophys. J. Lett., 2017, 843, 1, L13. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/aa7633/meta.

- 53.Elitzur, Moshe. Astronomical Masers. Springer-Science+Business Media, Dordrecht, Netherlands, 1992, pp. XIV-351. ISBN 978-0-7923-1217-8. [CrossRef]

- 54.Lyubarsky, Yuri. A model for fast extragalactic radio bursts. MNRAS, 2014, 442:L9–L13 . [CrossRef]

- 55.Beloborodov, A.M. A flaring magnetar in FRB 121102? Astrophys. J., 2017, 843:L26. [CrossRef]

- 56.Waxman E. On the origin of fast radio bursts (FRBs). Astrophys J 2017, 842:34 https://arxiv.org/abs/1703.06723.

- 57.Lingam, Manasvi; Loeb, Abraham. Fast Radio Bursts from Extragalactic Light Sails. Astrophys. J. 2017, 837, 2. [CrossRef]

- 58.Petty, Harry. SETI Institute Researchers Engage in World’s First Real-Time AI Search for Fast Radio Bursts. https://blogs.nvidia.com/blog/seti-institute-ai-fast-radio-bursts/ and https://www.seti.org/ October 8, 2024.

- 59.Rovelli, Carlo, ed. General Relativity: The most beautiful of theories (de Gruyter Studies in Mathematical Physics). Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Boston, USA. 2015. ISBN 978-3-11-034042-6.

- 60.Rovelli, Carlo. Relatività Generale. (It. tr. Pietropaolo Frisoni from General Relativity). Adelphi Edizioni, Milano, Italy. 2021. pp. 163. ISBN 978-88-459-3608-1.

- 61.Rovelli, Carlo. Buchi Bianchi. Adelphi Edizioni, Milano, Italy. 2023. pp. 144. ISBN 978-88-459-3753-8.

- 62.Barrau, Aurelian; Rovelli, Carlo; Vidotto, Francesca. Fast radio bursts and white hole signals. Physical Review D, 2014, 90, 12, id.127503. 5pp. [CrossRef]

- 63.Rovelli Carlo (Aix Marseille Universite, CNRS, Marseille, France. Personal communication, 2024.

- 64.Gelfand, Joseph D.; Gaensler, B. M. “The Compact X-ray Source 1E 1547.0-5408 and the Radio Shell G327.24-0.13: A New Proposed Association between a Candidate Magnetar and a Candidate Supernova Remnant”. arXiv:0706.1054v1 [astro-ph]. 2007 rev. 2018. [CrossRef]

- 65.Camilo F.; Ransom S. M.; Halpern J. P.; Reynolds J. The Magnetar 1E 1547.0–5408: Radio Spectrum, Polarimetry, and Timing. ApJ 2007 666 L93.

- 66.Zhang, Jun et al. 2023. "Sky-brightness measurements in J, H, and Ks bands at DOME A with NISBM and early results". MNRAS, 2023. 521 (4): 5624–5635. http://doi.org/10.1093/mnras/stad775.

- 67.Get Started With NVIDIA Holoscan. Available online. https://www.nvidia.com/en-us/clara/holoscan/ Accessed 2024.

- 68.Breakthrough Initiatives. https://breakthroughinitiatives.org/initiative/1 https://breakthroughinitiatives.org/manifesto Accessed 2024. Available online.

- 69.Maire, Jérôme, Drake, Frank et al. Search for Nanosecond Near-infrared Transients around 1280 Celestial Objects. Astronom. J. 2019, 158, 5, 203. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/1538-3881/ab44d3.

- 70.Maire, Jérôme, et al. A near-infrared SETI experiment: probability distribution of false coincidences. Proc. SPIE, 2014, 9147, 91474K. [CrossRef]

- 71.Maire, Jérôme, et al. A near-infrared SETI experiment: commissioning, data analysis, and performance results. Proc. SPIE, 2016, 9908, 990810. [CrossRef]

- 72.Maire, Jérôme, et al. Panoramic optical and near-infrared SETI instrument: optical and structural design concepts. Proc. SPIE, 2018, 10702. In Ground-based and Airborne Instrumentation for Astronomy VII; 107025L. [CrossRef]

- 73.Maire, Jérôme, et al. Panoramic SETI: on-sky results from prototype telescopes and instrumental design. arXiv:2111.11080v1 [astro-ph.IM]. SPIE Proceedings, 2021, 11454, X-Ray, Optical, and Infrared Detectors for Astronomy IX; 114543C (2020) . In SPIE Astronomical Telescopes + Instrumentation, 2020. arXiv:2111.11080v1 [astro-ph.IM] 22 Nov 2021. [CrossRef]

- 74.Townes, C. H. At what wavelengths should we search for signals from extraterrestrial intelligence? PNAS, 1983, 80 (4) 1147-1151 . [CrossRef]

- 75.Hippke, M. Interstellar communication: The colors of optical SETI. J. Astrophys. Astron. 2018, 39, 73. [CrossRef]

- 76.Drake, Frank D. Project Ozma. Physics Today 1961, 14 (4), 40–46 . [CrossRef]

- 77.Enriquez J. Emilio et al. The Breakthrough Listen Search for Intelligent Life: 1.1–1.9 GHz Observations of 692 Nearby Stars. ApJ 2017 849 104. [CrossRef]

- 78.MacMahon, David H. E. et al. The Breakthrough Listen Search for Intelligent Life: A Wideband Data Recorder System for the Robert C. Byrd Green Bank Telescope. PASP 2018 130 044502 https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1538-3873/aa80d2/meta.

- 79.Drago, Alessandro; Bini, Simone; Cestelli Guidi, Mariangela; Marcelli, Augusto; Bocci, Valerio; Pace, Emanuele. A Proposal for a Fast Infrared Bursts Detector. JINST, 2024, 19 P05027. [CrossRef]

- 80.Racusin, Judith (NASA) 2022. "Surveying the Dynamic Universe with the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope", L’Aquila Joint Astroparticle Colloquium, 4/27/22.

- 81.Riess, Adam G. et al. A Redetermination of the Hubble Constant with the Hubble Space Telescope from a Differential Distance Ladder. Astrophys. J. 2009, 699, 1, 539. [CrossRef]

- 82.Riess, Adam G., et al. A 3% Solution: Determination of the Hubble Constant with the Hubble Space Telescope and Wide Field Camera 3. Astrophys.J. 2011 730 119. [arXiv:1103.2976].

- 83.Riess, A. G., et al. Large Magellanic Cloud Cepheid Standards Provide a 1% Foundation for the Determination of the Hubble Constant and Stronger Evidence for Physics beyond ΛCDM”. Astrophys. J. 2019 876 1 85. [arXiv:1903.07603].

- 84.Schoedel R. et al. The JWST Galactic Center Survey. A White Paper. 2 Nov 2023. https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.11912 [astro-ph.GA].

- 85.STScI (Space Telescope Science Institute). JWST Pocket Guide. January 2024. https://www.stsci.edu/files/live/sites/www/files/home/jwst/instrumentation/_documents/jwst-pocket-guide.pdf.

- 86.Riess, Adam G. New Determination of the Hubble Constant with Gaia EDR3 Further Evidence of Excess Expansion. Rome Joint Astrophysics Colloquia, Tor Vergata Rome University, Italy. 20 October 2021.

- 87.Banks K. et al. James Webb Space Telescope Mid-Infrared Instrument cooler systems engineering. Proc. SPIE 7017, in: Modeling, Systems Engineering, and Project Management for Astronomy III, 70170A, 16 July 2008. [CrossRef]

- 88.Zhang, Zhi-Song et al. First SETI Observations with China's Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope (FAST). Astrophys. J. 2020 891 2 174. [CrossRef]

- 89.Ling, Zhixing et al. The Lobster Eye Imager for Astronomy Onboard the SATech-01 Satellite. RAA 2023.

- 90.Chen, Yifan et al. Detection system of the lobster eye telescope with large field of view. Applied Optics, 2022, 61, 29, pp. 8813-8818. [CrossRef]

- 91.Zhang, Chen et al. First wide field-of-view X-ray observations by a lobster eye focusing telescope in orbit. ApJL, 2022, 914, 2.

- 92.Ferroni, Fernando (former INFN President). Einstein Telescope: uno sguardo sull'alba dell'Universo. «CONFERENZE LINCEE», Accademia dei Lincei, Roma, Italy, 14 december 2023.

- 93.Branchesi, Marica et al. Science with the Einstein Telescope: a comparison of different designs. JCAP 07, 2023, 068. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1475-7516/2023/07/068 https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.15923.

- 94.Hanaoka, Y., Katsukawa, Y., Morita, S. et al. A HAWAII-2RG infrared camera operated under fast readout mode for solar polarimetry. Earth Planets Space, 2020, 72, 181. [CrossRef]

- 95.https://www.teledyneimaging.com/en/aerospace-and-defense/products/sensors-overview/infrared-hgcdte-mct/hawaii-2rg/.

- 96.Bell, A. R. The acceleration of cosmic rays in shock fronts – I. MNRAS, 1978, 182, 147–156".

- 97.Bell, A. R. The acceleration of cosmic rays in shock fronts – II. MNRAS, 1978, 182, 443–455".

- 98.Fermi, Enrico 1949. "On the Origin of the Cosmic Radiation”. Physical Review 75, pp. 1169-1174.

- 99.Sands, Matthew. The physics of electron storage rings: An introduction. Tech.Rep. SLAC-R-121, 1970, SLAC, Stanford, CA, USA.

- 100.Chao, Alexander Wu; Tigner, Maury. Handbook of Accelerator Physics and Engineering. World Scientific Publishing Co. Singapore. 1999. ISBN9810235003.

- 101.Conte, Mario; MacKay, William W. An Introduction to the Physics of Particle Accelerator. World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., Singapore. 1991. ISBN:981-02-0812-X, 981-02-0813-8.

- 102.Milardi C. et al. DaΦne Run for the Siddharta-2 Experiment. Presented at the IPAC’23, 14th International Particle Accelerator Conference, 7-12 May 2023, Venice, Italy. https://www.ipac23.org/ https://accelconf.web.cern.ch/ipac2023/pdf/MOPL085.pdf.

- 103.INFN, Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati, “DAΦNE-LIGHT Synchrotron Radiation Facility”. Available online. Accessed 2024. http://dafne-light.lnf.infn.it/.

- 104.Marcelli, Augusto et al. Infrared beamline SINBAD at DAFNE: expected performance at the sample site. Proc. of SPIE, 1999, 3775, 7. Accelerator-based Sources of Infrared and Spectroscopic Applications. Event: SPIE's International Symposium on Optical Science, Engineering, and Instrumentation, 1999, Denver, CO, United States. [CrossRef]

- 105.Cestelli Guidi, Mariangela et al. Optical performances of SINBAD, the Synchrotron Infrared Beamline At DAΦNE. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A/ 2005, 22, 12.

- 106.Prabhakar, Shyam. New Diagnostics and Cures for Coupled-Bunch Instabilities. PhD dissertation, Stanford University. SLAC-Report-554, Feb. 2000.

- 107.Laclare, J. L. Bunched beam instabilities. In Proceedings of High Energy Accelerators, (Geneva), 1980, pp. 526–539, Birkhauser, Basel, Switzerland.

- 108.Drago, A. et al.. Synchrotron oscillation damping due to beam-beam collisions. THOBRA01. Proc. of IPAC’10, Kyoto, Japan. May 23-28, 2010. In Conf. Proceedings C100523 (2010) THOBRA01. IPAC-2010-THOBRA0. ISBN 97892-9083-352-9.

- 109.Drago, A. et al. Synchrotron oscillation damping by beam-beam collisions in DAΦNE. PRSTAB, 2011, 14, 092803 (7 pages). [CrossRef]

- 110.Migliorati, Mauro et al. Beam-wall interaction in the CERN Proton Synchrotron for the LHC upgrade. Phys. Rev. ST Accel. Beams, 2013, 16, 031001. https://journals.aps.org/prab/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.16.031001.

- 111.Migliorati, Mauro; Palumbo, Luigi. Multibunch and multiparticle simulation code with an alternative approach to wakefield effects. PRSTAB, 2015, 18, 031001. https://journals.aps.org/prab/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevSTAB.18.031001.

- 112.Migliorati, M., Belli, E., Zobov, M. Impact of the resistive wall impedance on beam dynamics in the Future Circular e+ e− Collider. PRAB, 2018, 21, 041001. [CrossRef]

- 113.Migliorati, M.; Palumbo, L.; Zannini, C.; Biancacci, N.; Vaccaro, V. G. Resistive wall impedance in elliptical multilayer vacuum chambers. PRAB, 2019, 22, 121001. [CrossRef]

- 114.Migliorati, M.; Antuono, C.; Carideo, E.; Zhang, Y.; Zobov, M. Impedance modelling and collective effects in the Future Circular e+e- Collider with 4 IPs. The European Physical Journal Techniques and Instrumentation, 2022, 9:10. [CrossRef]

- 115.Behtouei, M.; Carideo, E.; Zobov, M.; Migliorati, M. Wakefields excited in the FCC-ee collimation system. JINST, 2024, 19, P02014. [CrossRef]

- 116.Biancacci et al. Transverse beam coupling impedance of the CERN Proton Synchrotron. PRAB, 2016, 19, 041001. [CrossRef]

- 117.Biancacci, N., et al. Transverse impedance studies of 2D azimuthally symmetric devices of finite length. PRSTAB, 2023, 26, 042001. [CrossRef]

- 118.Ishibashi, T.; Migliorati, M.; Zhou, D.; Shibata, K.; Abe, T.; Tobiyama, M.; Suetsugu, Y.; Terui, S. Impedance modelling and single-bunch collective instability simulations for the SuperKEKB main rings. JINST, 2024, 19 P02013. [CrossRef]

- 119.Joly, S.; Oeftiger, A.; Iadarola, G.; Zannini, C.; Migliorati, M.; Mounet, N.; Salvan, B. Recent advances in the CERN PS impedance model and instability simulations following the LHC Injectors Upgrade project. JINST, 2024, 19 P04018. [CrossRef]

- 120.Quartullo, Danilo et al Electromagnetic characterization of the crystal primary collimators for the HL-LHC. NIM-PRA, 2021, 1010, 165465. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.nima.2021.165465.

- 121.Teofili et al. Wake-function, impedance, and energy loss determination for two countermoving particle beams. PRAB, 2021, 24, 041001. [CrossRef]

- 122.Ashok K. Sood, et al. Recent Advances in EO/IR Imaging Detector and Sensor Applications. Chap.18 from: Handbook of Sensor Networking, Advanced Technologies and Applications. CRC Press. 2015. https://www.routledgehandbooks.com/doi/10.1201/b18001-25.

- 123.Bhat, Ishwara. Multicolor focal plane array detector technology: a review. Proc. of SPIE Vol. 5152 Infrared Spaceborne Remote Sensing XI, edited by Marija Strojnik. SPIE, Bellingham, WA, 2003. 0277-786X/03. pp. 279-288.

- 124.Chang, Yong. Far-infrared detector based on HgTe/HgCdTe superlattices. J. of Electronic Materials, 2003, 32, 7, pp.7.

- 125.Downs, Chandler and Vandervelde, Thomas E. Progress in Infrared Photodetectors Since 2000. Sensors 2013, 13(4), 5054-5098; [CrossRef]

- 126.Karim, Amir. Infrared detectors: Advances, challenges and new technologies. IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 2013. 51, 012001.

- 127.Rogalski, Antoni. Infrared detectors: an overview. Infrared Physics & Technology, 2002, 43. 187–210.

- 128.Sivananthan, S. HgCdTe/CdTe/Si infrared photodetectors grown by MBE for near-room temperature operation. Journal of Electronic Materials. 2001.

- 129.Tan, Chee Leong and Mohseni, Hooman. Emerging technologies for high performance infrared detectors. Nanophotonics 2018, 7(1): 169–197. pp. 29. [CrossRef]

- 130.Tran, Chieu D. Infrared Multispectral Imaging: Principles and Instrumentation. Applied Spectroscopy Reviews, 2003, 38, 2, pp. 133–153.

- 131.Rieke, M.J., Rieke, G.H., Montgomery, E.F. 1987. Rockwell HgCdTe arrays as imagers. In: Wynn-Williams, C.G., Becklin, E.E. (eds.) Infrared Astronomy with Arrays, 1987, p. 213. University of Hawaii Institute for Astronomy.

- 132.Rieke, G.H. Detection of light: from the ultraviolet to the submillimeter. Cambridge University Press. 2003.

- 133.Rieke, G.H. Infrared detector arrays for astronomy. ARAA, 2007, 45, 77. Exp Astron, 2009, 25, 125–141 . [CrossRef]

- 134.Piotrowski, J., Galus, M., Grudzien, M. Near room-temperature IR photo-detectors. Infrared Phys., 1991, 31(1), 1−48.

- 135.Piotrowski, Jozef. Recent advances in IR detector technology. Microelectronics Journal, 1992, 23, 305-313.

- 136.Piotrowski, Jozef et al. Uncooled long wavelength infrared photon detectors. Infrared Physics & Technology, 2004, pp. 13.

- 137.Ashokan, R.; Sivanathan, S. and Velicu, S. Mercury cadmium telluride : A superior choice for near room temperature infrared detectors (Review Paper). Defence Science Journal. 2001. 7 Pages.

- 138.Piotrowski, Jozef. Progress in MOCVD growth of HgCdTe heterostructures for uncooled infrared photodetectors. Infrared Physics & Technology, BULLETIN OF THE POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, TECHNICAL SCIENCES, 2007, 53, 2.

- 139.Piotrowski, Jozef et al. Uncooled MWIR and LWIR photodetectors in Poland. Opto-Electronics Review, 2010, 18(3), 318–327. [CrossRef]

- 140.Bocci, Alessio et al. Detection of the SR Infrared Emission of the Electron bunches at DAΦNE. LNF-05-12 (NT), 2005.

- 141.Bocci, A.; Piccinni, M.; Drago, A.; Cestelli Guidi, M; Sali, D.; Morini, P.; Pace, E.; Piotrowski, J.; Marcelli, A. Detection of pulsed synchrotron radiation emission with uncooled infrared detectors. LNF - 06 / 7 (P), 2006.

- 142.Bocci, A.; Marcelli, A.; Pace, E.; Drago, A.; Piccinni, M.; Cestelli Guidi, M.; Sali, D.; Morini, P.; Piotrowski, J. Time resolved detection of infrared synchrotron radiation at DAFNE. 9th Int. Conf. on Synchrotron Radiation Instrumentation (SRI2006), Daegu, Korea, 28 May-2 June 2006. Pub. in AIP CONF. PROC. 879:1246-1249, 2007. Also in *DAEGU 2006, Synchrotron Radiation Instrumentation * 1246-1249. [CrossRef]

- 143.Bocci, Alessio et al. Bunch-by-bunch longitudinal diagnostics at DAFNE by IR light. 8th European Workshop on Beam Diagnostics and Instrumentation for particle accelerators (DIPAC 2007), Venezia, Italia. 2007. Conf. Proceedings.

- 144.Bocci, Alessio et al. Fast Infrared Detectors for Beam Diagnostics with Synchrotron Radiation. Nucl.Instrum.Meth.A 2007, 580:190-193. [CrossRef]

- 145.Bocci, Alessio et al. Beam diagnostics at DAFNE with fast uncooled IR detectors. Proc. of 13th Beam Instrumentation Workshop (BIW08), Lake Tahoe, California, 4-8 May 2008. 4pp. Pub. in *Tahoe City 2008, Beam Instrumentation Workshop 2008* 145-148. E-print: arXiv:0806.1958 [PHYSICS.ACC-PH].

- 146.Drago, A., Cestelli Guidi, M., De Sio, A., Marcelli, A., Pace, E. Beam Diagnostics by infrared time resolved detectors. 20th IMEKO TC4 International Symposium, Benevento, Italy, September 15th -17th , 2014. Conf. Proc. 6 pp.

- 147.Drago, A.; Bocci, A.; Cestelli Guidi, M.; De Sio, A.; Pace, E.; Marcelli, A. Bunch-by-bunch profile diagnostics in storage rings by infrared array detection. Meas. Science and Technology 2015, 26 094003 (10pp). [CrossRef]

- 148.Drago, Alessandro et al. Fast Rise Time IR Detectors for Lepton Colliders. 4th ICFDT. 2016. Conference proceedings in JINST 2016. 11, 07, C07004. [CrossRef]

- 149.VIGO Photonics. https://vigophotonics.com/, <https://vigophotonics.com/app/uploads/2022/06/VIGO_katalog_2020-2021-LQ-1.pdf>. Accessed 2024. Available online.

- 150.Hamamatsu Photonics. https://www.hamamatsu.com/eu/en.html Accessed 2024. Available online.

- 151.Drago, Alessandro, et al. Ultra-Fast Infrared Detector for Astronomy. Nucl.Instrum.Meth.A. 2023. 1048, 167936. [CrossRef]

- 152.Drago, Alessandro, et al. Fast Transient Infrared Detection for Time-domain Astronomy. JINST 2023. 18 C02012 . JINST Part of ISSN: 1748-0221. [CrossRef]

- 153.Drago, Alessandro, et al. Performance evaluation of an Ultra-Fast IR Detector for Astronomy Transients. NANOINNOVATION-2022 Proc. of J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 2023. 2579 012013. [CrossRef]

- 154.INFN, Laboratori Nazionali di Frascati. DAΦNE-LIGHT Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Available online. Accessed 2024. http://dafne-light.lnf.infn.it/.

- 155.Teledyne ADQ7DC-10 GSPS, 14-bit digitizer: https://www.spdevices.com/what-we-do/products/hardware/14-bit-digitizers/adq7dc Available online.

- 156.https://octave.org/ Available online.

- 157.https://mathworks.com/ Available online.

- 158.Fukunaga, K. Introduction to Statistical Pattern Recognition. Academic Press, New York and London, USA and UK, 1972.

- 159.Patrick, E. A. Fundamental of Pattern Recognition. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA, 1972.

- 160.Watanabe, S. Frontiers of Pattern Recognition. Academic Press, New York and London. USA and UK, 1972.

- 161.Tou, J.T. and Gonzales, R. C. Pattern Recognition Principles. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, Massachusetts, USA. 1974.

- 162.Fu, K. S. et al. Digital Pattern Recognition. Springer-Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg New York. West Germany and USA. 1976.

- 163.Rosenfeld, A. Picture Processing by Computer. Academic Press, New York London. USA and UK. 1969.

- 164.Duda, R. O. and Hart, P. E. Pattern Classification and Scene Analysis. Wiley, New York. USA. 1973.

- 165.Chen, C. H. Statistical Pattern Recognition. Hayden Book Company, Washington, D. C., USA. 1973.

- 166.Andrews, H. C. Introduction to Mathematical Techniques in Pattern Recognition. Wiley, New York, USA. 1972.

- 167.Fu, K. S. Sequential Methods in Pattern Recognition. Academic Press, New York., USA. 1968.

- 168.Rosenfeld, A.; Kak, A. C. Digital Picture Processing. Academic Press, New York, USA. 1976.

- 169.Hohne, H. D. Second International Joint Conference on Pattern Recognition, page 307, IEEE, Copenhagen, Denmark. 1974.

- 170.Kowalik, J. and Osborne, M. R. Methods for Unconstrained Optimization Problems. American Elsevier Publishing Co. Inc., New York, USA. 1968.

- 171.Drago, Alessandro. Elaborazione e messa a punto di un procedimento per l’analisi automatica di strisce elettroforetiche di lipoproteine. Tesi di laurea in fisica. Università di Roma (La Sapienza), Italia, 1978. pp. 174-IV.

- 172.Minsky, Marvin L. and Papert, Seymour A. Perceptrons: expanded edition. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, United States. ISBN: 0262631113. 1988. Pages: 292.

- 173.Rosenblatt, F. Principles of Perceptrons. Spartan, Washington, DC, USA. 1962.

- 174.Hopfield, John J. Neural networks and physical systems with emergent collective computational abilities. PNAS, 1982, 79 (8) 2554-2558. [CrossRef]

- 175.Hinton, Geoffrey E. 6: How Neural Networks Learn from Experience. Book Chapter. [CrossRef]

- 176.LeCun, Yann; Bengio, Yoshua and Hinton, Geoffrey. Deep learning. Nature, 2015, 521.7553: 436-444. https://www.nature.com/articles/nature14539.

- 177.Goodfellow I., Bengio Y., Courville A. Deep Learning. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, USA. 2016. pp. 800. ISBN: 978-0262035613.

- 178.Casas González, J. M. Machine Learning in Astrophysics and Cosmology. Doctoral dissertation. 2023. Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad de Oviedo. https://hdl.handle.net/10651/72156.

- 179.Trevisan, Piero. Case studies of interpretable machine learning in astrophysics. Doctoral thesis. University of Roma1. 2023. https://iris.uniroma1.it/handle/11573/1700595.

- 180.Soo, J. Y. H., Shuaili, I.Y.K., Pathi, I.M. 2023. Machine learning applications in astrophysics: Photometric redshift estimation. In AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2756, 040001. [CrossRef]

- 181.Ciacci, Giulia, Barucci, Andrea, Di Ruzza, Sara and Alessi, Elisa Maria 2024. “Asteroids co-orbital motion classification based on Machine Learning”. MNRAS, 2024, 527, 3, January. Pages 6439–6454. [CrossRef]

- 182.Petroff E., Keane E. F., Barr E. D., Reynolds J. E., Sarkissian J., Edwards P. G. , Stevens J., Brem C., Jameson A., Burke-Spolaor S. et al. Identifying the source of perytons at the Parkes radio telescope. MNRAS 2015, 451, 4, Pages 3933–3940. [CrossRef]

- 183.Moroz, V.I. An attempt to observe the infrared radiation of the galactic nucleus. Astron. Z., 1961, 38, 487.

- 184.Ajello, M. et al FERMI-LAT Observations of High-Energy γ-Ray Emission toward the Galactic Center. ApJ, 2016, 819 44. [CrossRef]

- 185.Pearlman AB, Majid WA, Prince TA, Kocz J, Horiuchi S. Pulse Morphology of the Galactic Center Magnetar PSR J1745–2900. Astrophys J, 2018, 866(2):160.

- 186.Yan, W. M., Wang, N., Manchester R. N. ,Wen Z. G., and J. P. Yuan, J. P. Single-pulse observations of the Galactic centre magnetar PSR J1745−2900 at 3.1 GHz. MNRAS, 2018, 476, 3677–3687. [CrossRef]

- 187.Moroz, V.I. The radiation flux from the Crab Nebula at 2 microns and some conclusions on the spectrum and magnetic field. Astron. Z., 1960, 37, 265.

- 188.Moroz, V.I. Infrared observations of the Crab Nebula. Astron. Ah., 1963, 40, 982.

- 189.Moroz, V.I. Radiation emission from the Orion Nebula in the 0.85–1.7 micron wavelength region. Astron. Z., 1963, 40, 788.

- 190.ESA, MIRI — the Mid-InfraRed Instrument. Accessed 2024. https://esawebb.org/about/instruments/miri/.

- 191.ESA, weic2414 (exoplanet WASP-107b) Science Release. Webb cracks case of inflated exoplanet. 20 May 2024. https://esawebb.org/news/weic2414/.

- 192.Gelfand, Joseph D. & Gaensler, B. M. The Compact X-ray Source 1E 1547.0-5408 and the Radio Shell G327.24-0.13: A New Proposed Association between a Candidate Magnetar and a Candidate Supernova Remnant. arXiv:0706.1054v1 [astro-ph]. 2007 rev. 2018. [CrossRef]

- 193.Amato, E., Recchia, S. Gamma-ray halos around pulsars: impact on pulsar wind physics and galactic cosmic ray transport. Riv. Nuovo Cim., 2024, 47, 399–452. [CrossRef]

- 194.Brisken, Walter F.; Thorsett, S. E.; Golden, A.; Goss, W. M. The Distance and Radius of the Neutron Star PSR B0656+14. Astrophysical Journal, 2003,. 593 (2): L89–L92. arXiv:astro-ph/0306232 . [CrossRef]

- 195.SETI Institute.Scientists Use Allen Telescope Array to Search for Radio Signals in the TRAPPIST-1 Star System. SETI Press release October, 16th 2024.

- 196.Tusay, Nick et al. A Radio Technosignature Search of TRAPPIST-1 with the Allen Telescope Array. arXiv: [Subm. on 12 Sep 2024] . [CrossRef]

- 197.Caleb, M., Burgay, M. et al. Simultaneous multi-telescope observations of FRB 121102. MNRAS, 2020, 496, 4, Pages 4565–4573. [CrossRef]

- 198.Tendulkar et al. The host galaxy and redshift of the repeating fast radio burst FRB 121102. Astrophys J, 2017, 834:L7. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/834/2/L7.

- 199.Chatterjee, S. et al. A direct localization of a fast radio burst and its host. Nature, 2017, 541, 7635, pp. 58–61. [CrossRef]

- 200.Metzger et al. Millisecond Magnetar Birth Connects FRB 121102 to Superluminous Supernovae and Long-duration Gamma-Ray Bursts. ApJ, 2017, 841 14. [CrossRef]

- 201.Murase, Kohta et al. A burst in a wind bubble and the impact on baryonic ejecta: high-energy gamma-ray flashes and afterglows from fast radio bursts and pulsar-driven supernova remnants. MNRAS,2016, 461, 2, 11. Pages 1498–1511. [CrossRef]

- 202.Bassa, C. G. et al. FRB 121102 Is Coincident with a Star-forming Region in Its Host Galaxy. ApJL, 2017, 843, 1, L8. [CrossRef]

- 203.Marcote, B. et al. The Repeating Fast Radio Burst FRB 121102 as Seen on Milliarcsecond Angular Scales. ApJL, 2017, 834 L8. https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/834/2/L8. [CrossRef]

- 204.Petroff E, et al. A fast radio burst with a low dispersion measure. MNRAS, 2018, 482:3109–3115.

- 205.cLinscott I. R.; Erkes J. W. Discovery of millisecond radio bursts from M87. Astrophys, 1980, J236:L109–L113.

- 206.Amy S. W., Large M. I., Vaughan A. E. Miscellaneous radio astronomy. Proc Astron Soc Aust, 1989, 8:172–175.

- 207.Schneemann, T.; Schmieden, K.; Schott, Matthias S. Search for gravitational waves using a network of RF cavities. NIMA, 2024, 1068, 169721 . [CrossRef]

- 208.INFN NEWSLETTER 124. GravNet: Taking the Search for Gravitational waves to a New Frequency. Interview to Claudio Gatti. December, 30th 2024.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).