Submitted:

27 January 2025

Posted:

28 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1. Initiation

2. Propagation

3. Termination

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Results from Literature

3.2. Computational Results from Literature

3.3. Molecular Modeling and Chemical Engineering Modeling Results for Air Oxidation Of Toluene

4. Computational Results

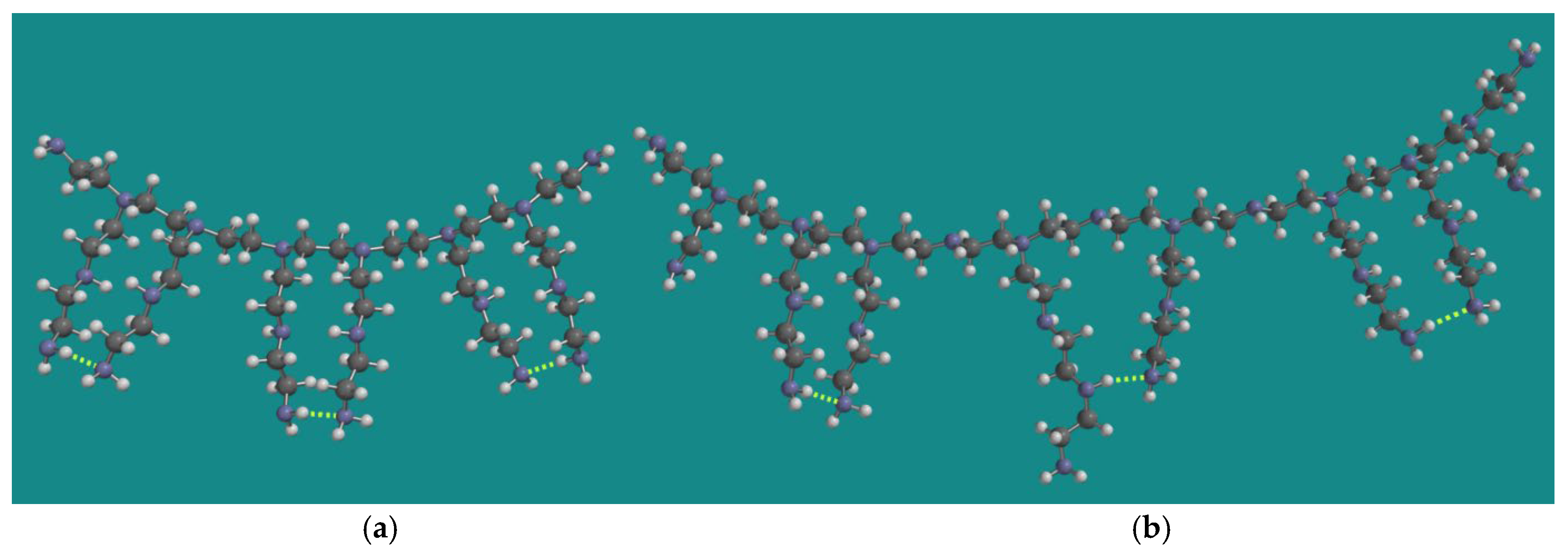

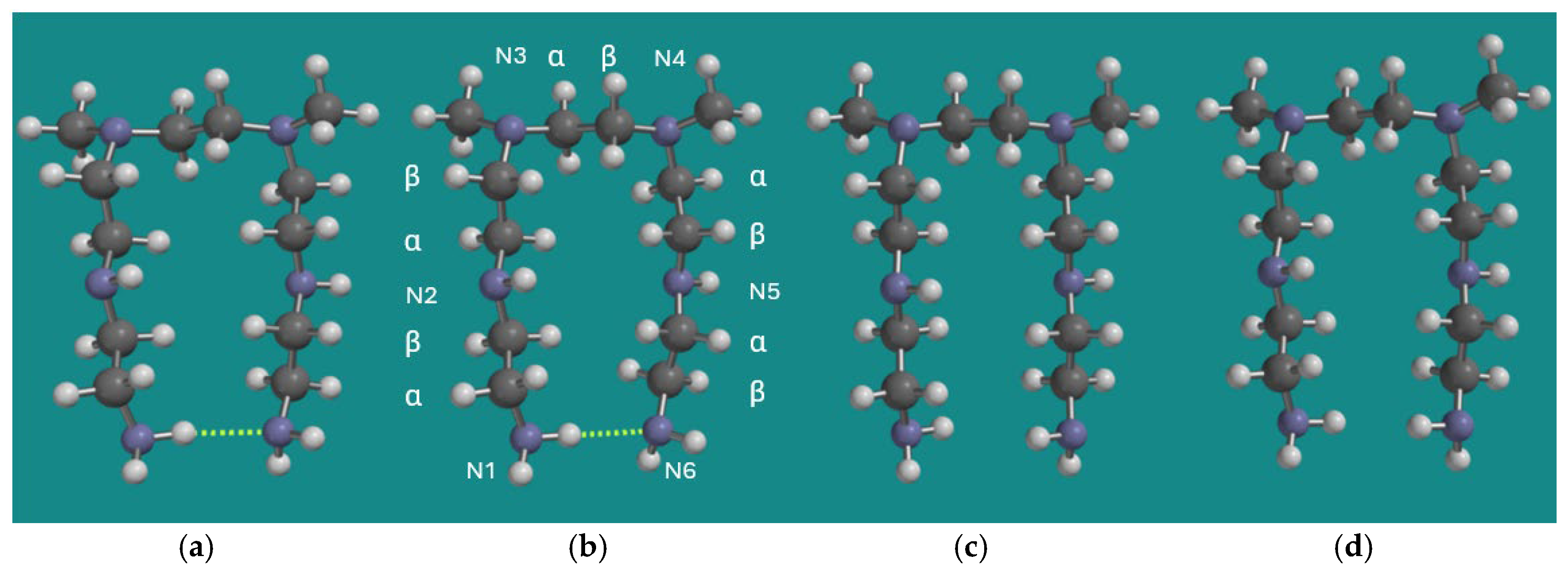

4.1. Model Systems

4.2. Loss of Amine Efficiency

4.3. FRCA of PEI: Propagation

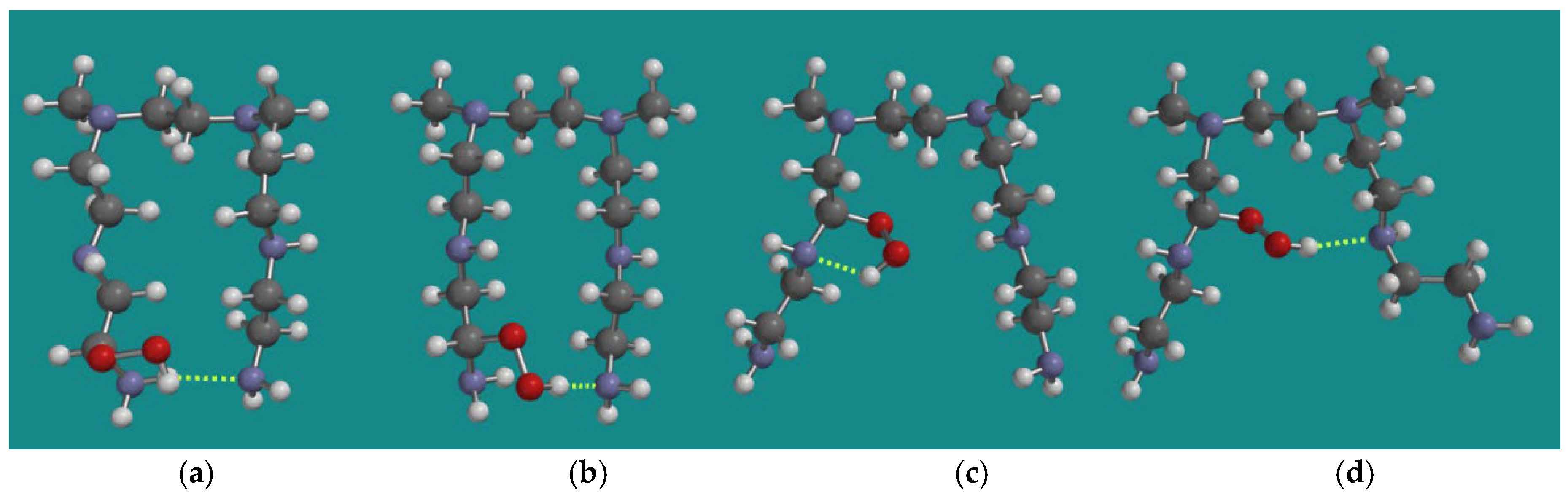

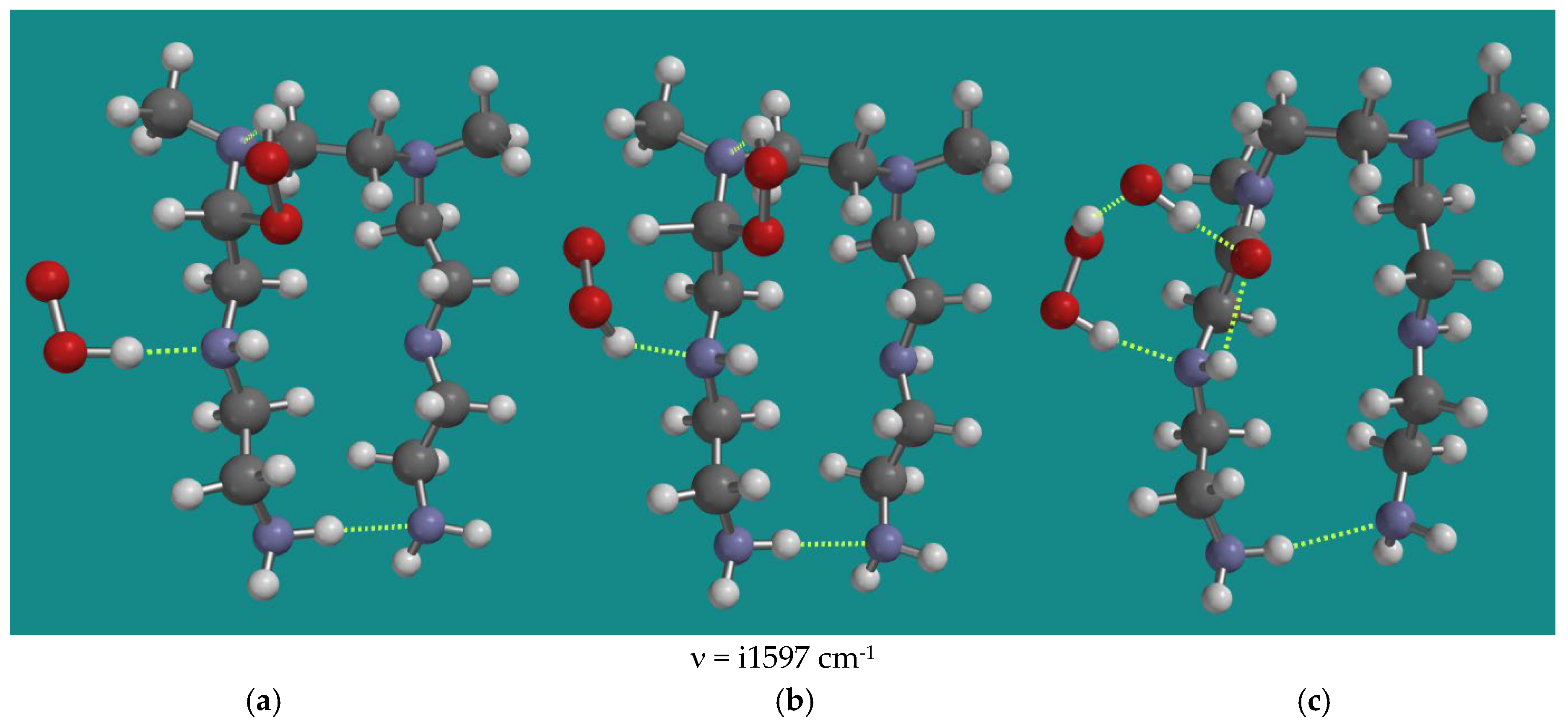

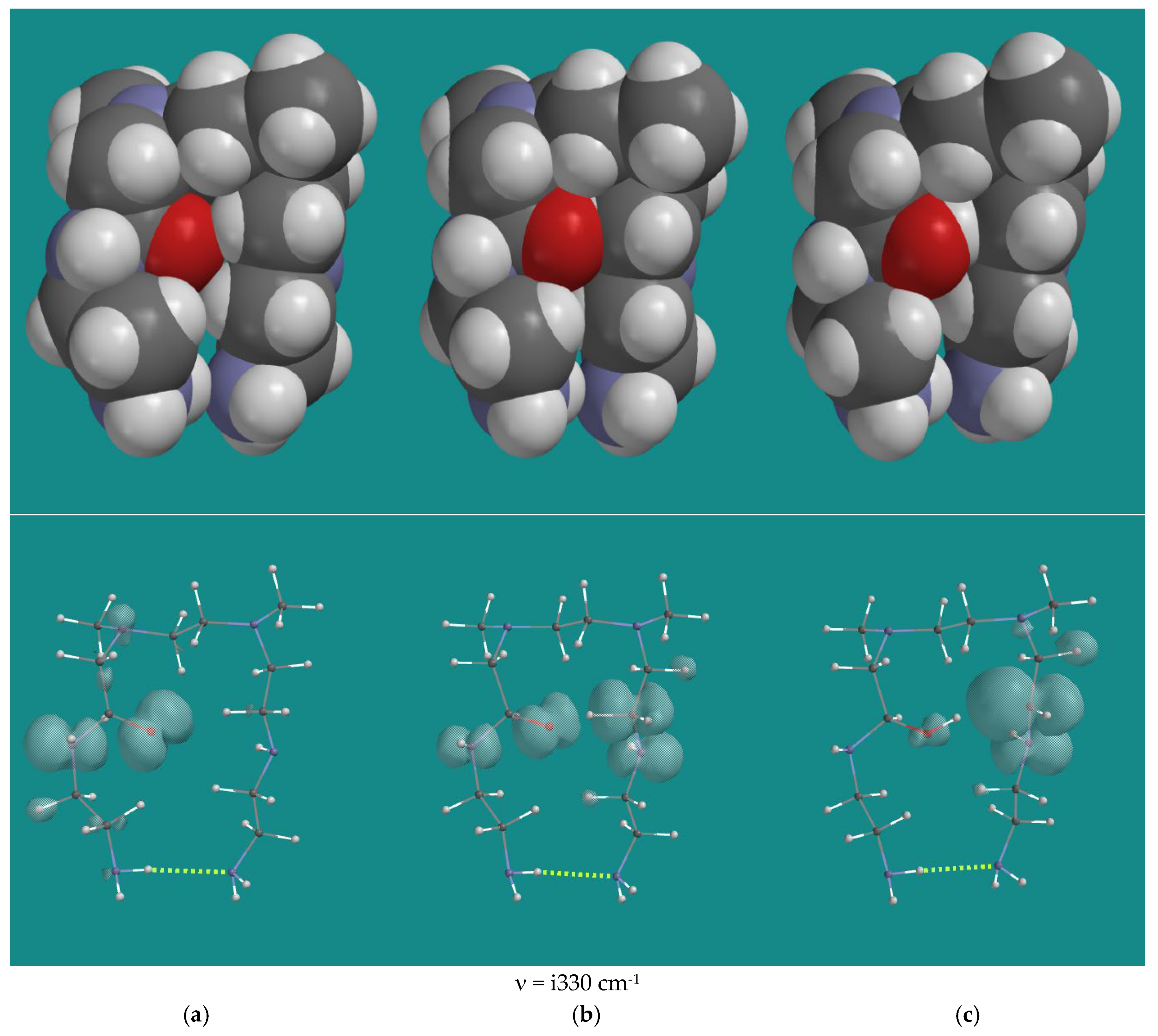

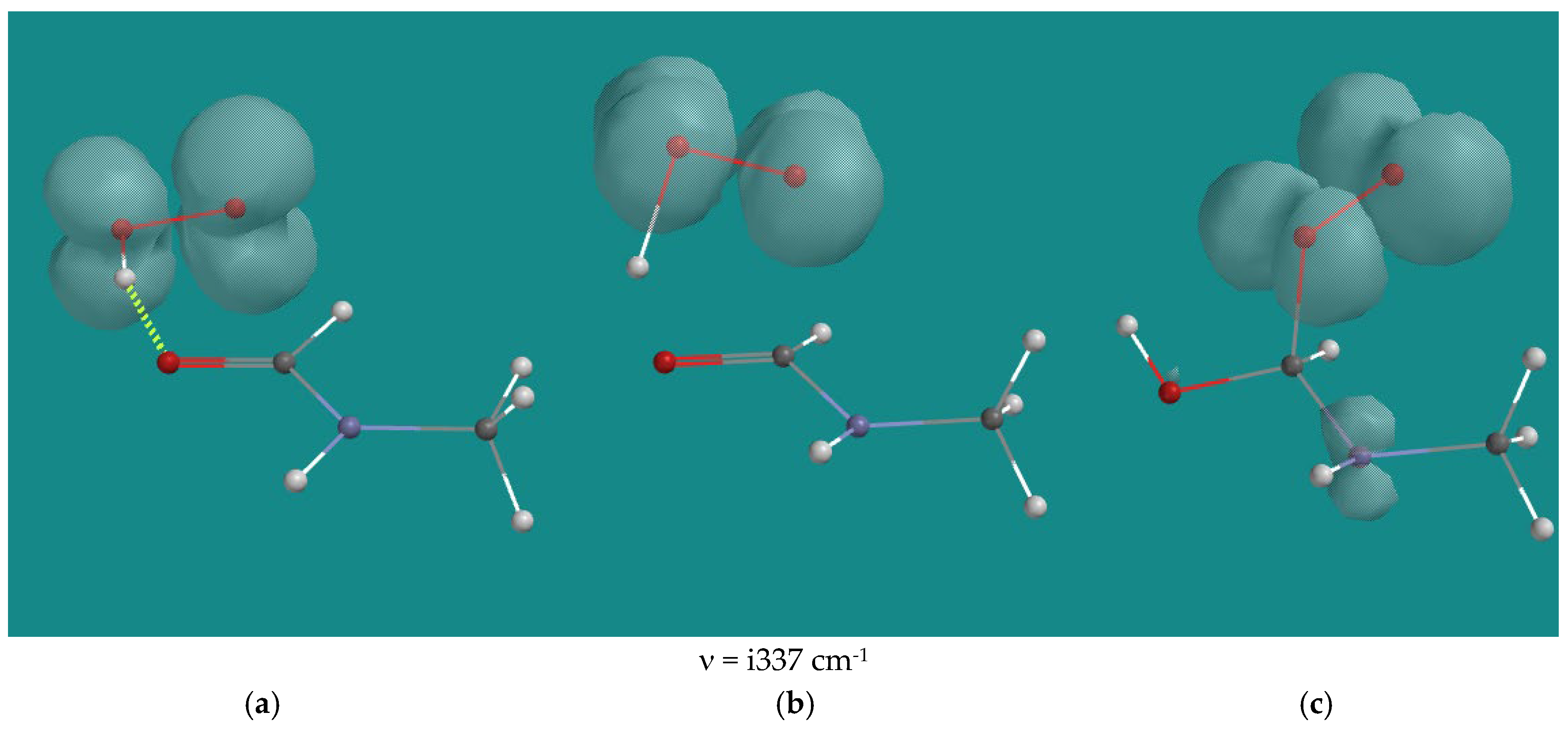

4.3.1. Decomposition of α-Amino Hydroperoxides by HO2•(d) and HO•(d)

4.3.2. Propagation with α- and β-Amino Peroxy Radicals

4.3.3. Propagation with HO2•(d) radical

4.4. Side Reactions

4.4.1. Propagation with Various α-Amino CH•(d) Radicals and H2O2

4.4.2. β-Elimination of N-β-CH•NHR(d) Radicals

4.4.3. Formation of NH3.

4.4.4. Formation of CO2.

5. Discussion

5.1. Set of Propagation Reactions

5.2. Final Products of FRCA of PEI

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- D’Alessandro, D. M.; Smit, B.; Long, J. R. Carbon dioxide capture: prospects for new materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6058–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haszeldine, R. S. Carbon capture and storage: how green can black be? Science 2009, 325, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency. U.S. Carbon Dioxide Emissions, 2020. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/ghgemissions/overview-greenhouse-gases (accessed on day month year).

- Choi, S.; Drese, J. H.; Jones, C. W. Adsorbent Materials for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Large Anthropogenic Point Sources. ChemSusChem 2009, 2, 796–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goeppert, A.; Zhang, H.; Czaun, M.; May, R. B.; Prakash, G. K. S.; Olah, G. A.; Narayanan, R. R. Easily Regenerable Solid Adsorbents Based on Polyamines for Carbon Dioxide Capture from the Air. ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 1386–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Pérez, E. S.; Murdock, C. R.; Didas, S. A.; Jones, C. W. Direct Capture of CO2 from Ambient Air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Du, H.; Mullins, R. H.; Kommalapati, R. R. Polyethylenimine Applications in Carbon Dioxide Capture and Separation: From Theoretical Study to Experimental Work. Energy Technol 2017, 5, 822–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veneman, R.; Zhao, W.; Li, Z.; Cai, N.; Brilman, D. W. F. Adsorption of CO2 and H2O on supported amine sorbents. Energy Procedia 2014, 63, 2336–2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesi, W. R., Jr; Kitchin, J. R. Evaluation of a primary amine functionalized ion-exchange resin for CO2 capture. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 6907–6915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nezam, I.; Xie, J.; Golub, K. W.; Carneiro, J.; Olsen, K.; Ping, E. W.; Jones, C. W.; Sakwa-Novak, M. A. Chemical Kinetics of the Autoxidation of Poly(ethylenimine) in CO2 Sorbents. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 8477–8486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racicot, J.; Li, S.; Clabaugh, A.; Hertz, C.; Akhade, S. A.; Ping, E. W.; Pang, S. H.; Sakwa-Novak, M. A. Volatile Products of the Autoxidation of Poly(ethylenimine) in CO2 Sorbents. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 8807–8816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosu, C.; Pang, S. H.; Sujan, A. R.; Sakwa-Novak, M. A.; Ping, E. W.; Jones, C. W. Effect of Extended Aging and Oxidation on Linear Poly(propylenimine)-Mesoporous Silica Composites for CO2 Capture from Simulated Air and Flue Gas Streams. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 38085–38097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadalinezhad, A.; Sayari, A. Oxidative degradation of silica supported polyethylenimine for CO2 adsorption: insights into the nature of deactivated species. Phys.Chem.Chem.Phys. 2014, 16, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.; Choi, W.; Kim, C.; Choi, M. Oxidation-stable amine containing adsorbents for carbon dioxide capture. NATURE COMMUNICATIONS 2018, 9, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buijs, W. CO2 Capture with PEI: A Molecular Modeling Study of the Ultimate Oxidation Stability of LPEI and BPEI ACS Engineering Au 2023, 3, 28–36. [CrossRef]

- Buijs, W. M: of Fe Complexes as Initiators in the Oxidative Degradation of Amine Resins for CO2 Capture, 2024; 4, 112–124. [CrossRef]

- Chatani, Y.; Tadokoro, H.; Saegusa, T.; Ikeda, H. Structural Studies of Poly(ethylenimine). 1. Structures of Two Hydrates of Poly(ethylenimine): Sesquihydrate and Dihydrate. Macromolecules 1981, 14, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatani, Y.; Kobatake, T.; Tadokoro, H.; Tanaka, R. Structural Studies of Poly(ethylenimine). 2. Double-Stranded Helical Chains in the Anhydrate. Macromolecules 1982, 15, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatani, Y.; Kobatake, T.; Tadokoro, H. Structural Studies of Poly(ethylenimine). 3. Structural Characterization of Anhydrous and Hydrous States and Crystal Structure of the Hemihydrate. Macromolecules 1983, 16, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashida, T.; Tashiro, K.; Aoshima, S.; Inaki, Y. Structural Investigation on Water-Induced Phase Transitions of Poly(ethyleneimine). 1. Time-Resolved Infrared Spectral Measurements in the Hydration Process. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 4330–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashida, T.; Tashiro, K.; Inaki, Y. Structural Investigation of Water-Induced Phase Transitions of Poly(ethylene imine). III. The Thermal Behavior of Hydrates and the Construction of a Phase Diagram. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2003, 41, 2937–2948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashida, T.; Tashiro, K. Structural Study on Water-induced Phase Transitions of Poly(ethylene imine) as Viewed from the Simultaneous Measurements of Wide-Angle X-ray Diffractions and DSC Thermograms. Macromol. Symp. 2006, 242, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyethylenimine, branched; product number 408719. Available online: https://www.sigmaaldrich.com/AT/de/substance/polyethyleniminebranched1234525987068?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=9419398930&utm_content=98056962600&gclid=CjwKCAjwjsi4BhB5EiwAFAL0YG6XEh8JeeAkfqel2YUFCyT_DJbGMS7B9r_6vT4lgpPy-rYSyQBIDRoCM4wQAvD_BwE.

- Epomin-SP-012. Available online: https://www.shokubai.co.jp/en/products/detail/epomin1/.

- Sheldon, R. A. , Kochi, J. Metal-Catalyzed Oxidation of Organic Compounds. Academic Press, Inc.: New York, 1981, 18-24. [CrossRef]

- Smith, L. M.; Aitken, H. M.; Coote, M. L. The Fate of the Peroxyl Radical in Autoxidation: How Does Polymer Degradation Really Occur? Acc. Chem. Res. 2018, 51, 2006–2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, I. , Nguyen, T.L., Jacobs, P.A., Peeters, J. Autoxidation of Cyclohexane: Conventional Views Challenged by Theory and Experiment. ChemPhysChem 2005, 6, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hermans, I. , Pierre A. Jacobs, P.A., Peeters, J. To the Core of Autocatalysis in Cyclohexane Autoxidation. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 4229–4240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, G. , Valiev, R., Salo, V-T., Kurtén, T. Accretion Products in the OH- and NO3-Initiated Oxidation of α-Pinene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 10632–10639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salo, V-T. , Rashid Valiev, R., Lehtola, S., Theo Kurtén, T. Gas-Phase Peroxyl Radical Recombination Reactions: A Computational Study of Formation and Decomposition of Tetroxides. J. Phys. Chem. A 2022, 126, 4046–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, G. , Sheldon, R. A. Oxidation. Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2012, 25, 543. [Google Scholar]

- Hermans, I. , Peeters, J., Vereecken, L., Jacobs, P. A. Mechanism of Thermal Toluene Autoxidation. ChemPhysChem 2007, 8, 2678–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoorn, J. A. A. , van Soolingen, J., Versteeg, G.F. Modelling Toluene Oxidation: Incorporation of Mass Transfer Phenomena. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2005, 83, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spartan ’20 and ’24 are products of Wavefunction Inc: Irvine, CA, 2021. Available online: www.wavefun.com (accessed on 22 October 2024).

- Halgren, T.A. MMFF VII. Characterization of MMFF94, MMFF94s, and other widely available force fields for conformational energies and for intermolecular-interaction energies and geometries. J Comput Chem. 1999, 20, 730–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme,S. , Ehrlich, S., Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 2011, 32, 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimme, S. , Hansen, A., Brandenburg J.G., Bannwarth, C. Dispersion-corrected mean-field electronic structure methods. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 5105–5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goerigk, L. How Do DFT-DCP, DFT-NL, and DFT-D3 Compare for the Description of London-Dispersion Effects in Conformers and General Thermochemistry? Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation, January 27, 2014 Vol 10/Issue 3.

- Hehre, W. J.; Ditchfield, R.; Radom, L.; Pople, J. A. Molecular Orbital Theory of the Electronic Structure of Organic Compounds. V. Molecular Theory of Bond Separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukui, K. A. Formulation of the Reaction Coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 4161–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franck–Rabinowitch solvent cage effect: IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 3rd ed. International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry; 2006. Online version 3.0.1, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Keading, W.W. , Lindblom, R.O., Temple, R.G., Mahon, H.I., Oxidation of toluene and other alkylated aromatic hydrocarbons to benzoic acids and phenols. Ind Eng Chem Process Des Dev, 1965, 4, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Introduction for Noveon Kalama Inc. Available online: https://www.chemnet.com/United-StatesSuppliers/7652/Noveon-Kalama-Inc-.html (accessed on day month year).

- Buijs, W. Molecular Modeling Study to the Relation between Structure of LPEI, Including Water-Induced Phase Transitions and CO2 Capturing Reactions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 11309–11316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, R. B.; Kolle, J. M.; Essalah, K.; Tangour, B.; Sayari, A. A Unified Approach to CO2-Amine Reaction Mechanisms. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 26125–26133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvyagin, A. V., Manson, N. B Chapter 10 - Optical and Spin Properties of Nitrogen-Vacancy Color Centers in Diamond Crystals, Nanodiamonds, and Proximity to Surfaces. Ultananocrystalline Diamond (Second Edition) 2012. [CrossRef]

- Wilke, C.R. , Chang, P. Correlation of diffusion coefficients in dilute solutions. Aiche Journal 1955, 1, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy-Alcantar, C. , Yatsimirsky, A. K., Lehn, J.-M. Structure stability correlations for imine formation in aqueous solution. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunkan, A.J.C. , Hetzler, J., Mikoviny, T., Wisthaler, A., Nielsen, C.J., Olzmann, M. The reactions of N-methylformamide and N,N-dimethylformamide with OH and their photo-oxidation under atmospheric conditions: experimental and theoretical studies. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 7046–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buijs, W. Direct Air Capture of CO2 with an Amine Resin: A Molecular Modeling Study of the Deactivation Mechanism by CO2. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2019, 58, 14705–14708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G. , Bozzelli, J. W. Role of the α-hydroxyethylperoxy radical in the reactions of acetaldehyde and vinyl alcohol with HO2. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2009, 483, 25–29. [Google Scholar]

| Entry | N,N-3,4-dimethyl N6 pentamer and R•(d) | Ea (kJ/mol) | n (cm-1) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N1-a-amino hydroperoxide | HO2•(d) | 115.7 | i1790 |

| 2 | N2-a-amino hydroperoxide | HO2•(d) | 93.9 | i1486 |

| 3 | N2-b-amino hydroperoxide | HO2•(d) | 112.3 | i1597 |

| 4 | N5-a-amino hydroperoxide | HO2•(d) | 85.5 | i1265 |

| 5 | N1-amide-b-hydroperoxide | HO2•(d) | 90.3 | i1401 |

| 6 | N1,2-diamide-N1-b-hydroperoxide | HO2•(d) | 103.9 | i1639 |

| 7 | N1-a-amino hydroperoxide | HO•(d) | 21.2 | i794 |

| 8 | N2-b-amino hydroperoxide | HO•(d) | 9.3 | i989 |

| 9 | N4-b-amino hydroperoxide | HO•(d) | 9.9 | i131 |

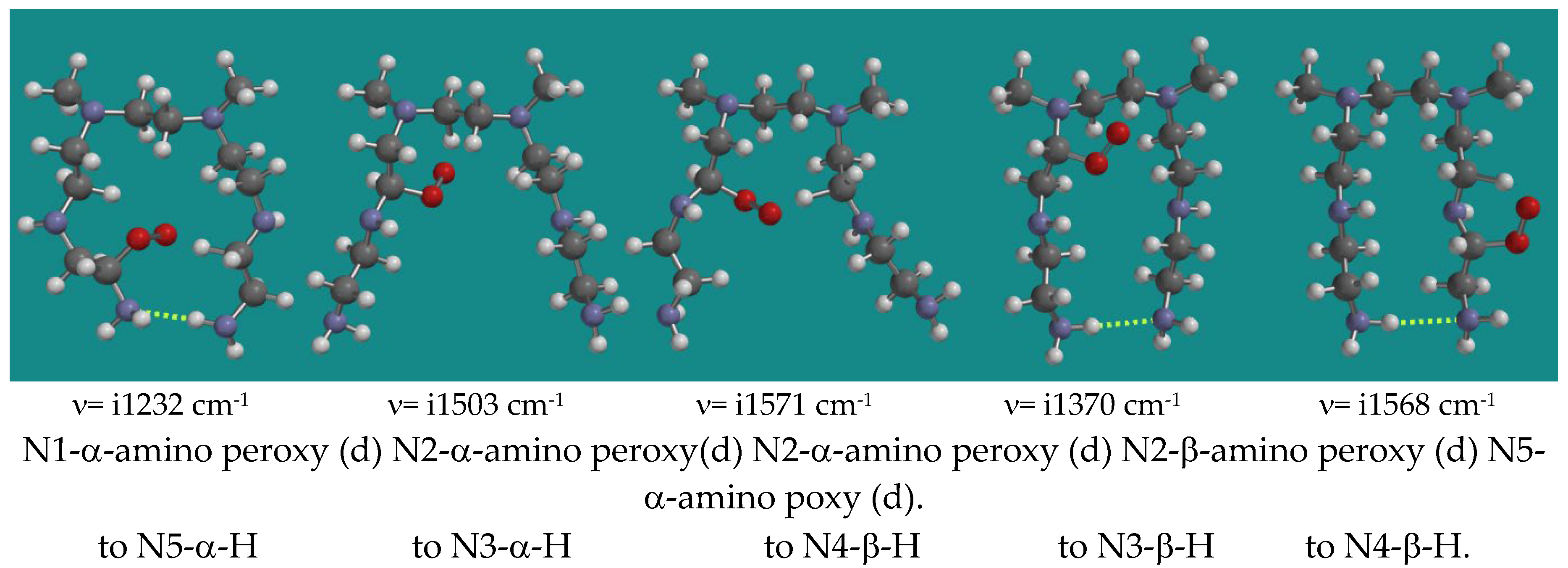

| 10 | N5-a-H | N1-a-amino peroxy radical (d) | 71.3 | i1232 |

| 11 | N3-a-H | N2-a-amino peroxy radical (d) | 32.4 | i1503 |

| 12 | N4-b-H | N2-a-amino peroxy radical (d) | 36.2 | i1571 |

| 13 | N3-b-H | N2-b-amino peroxy radical (d) | 71.2 | i1370 |

| 14 | N4-b-H | N5-a-amino peroxy radical (d) | 80.2 | i1568 |

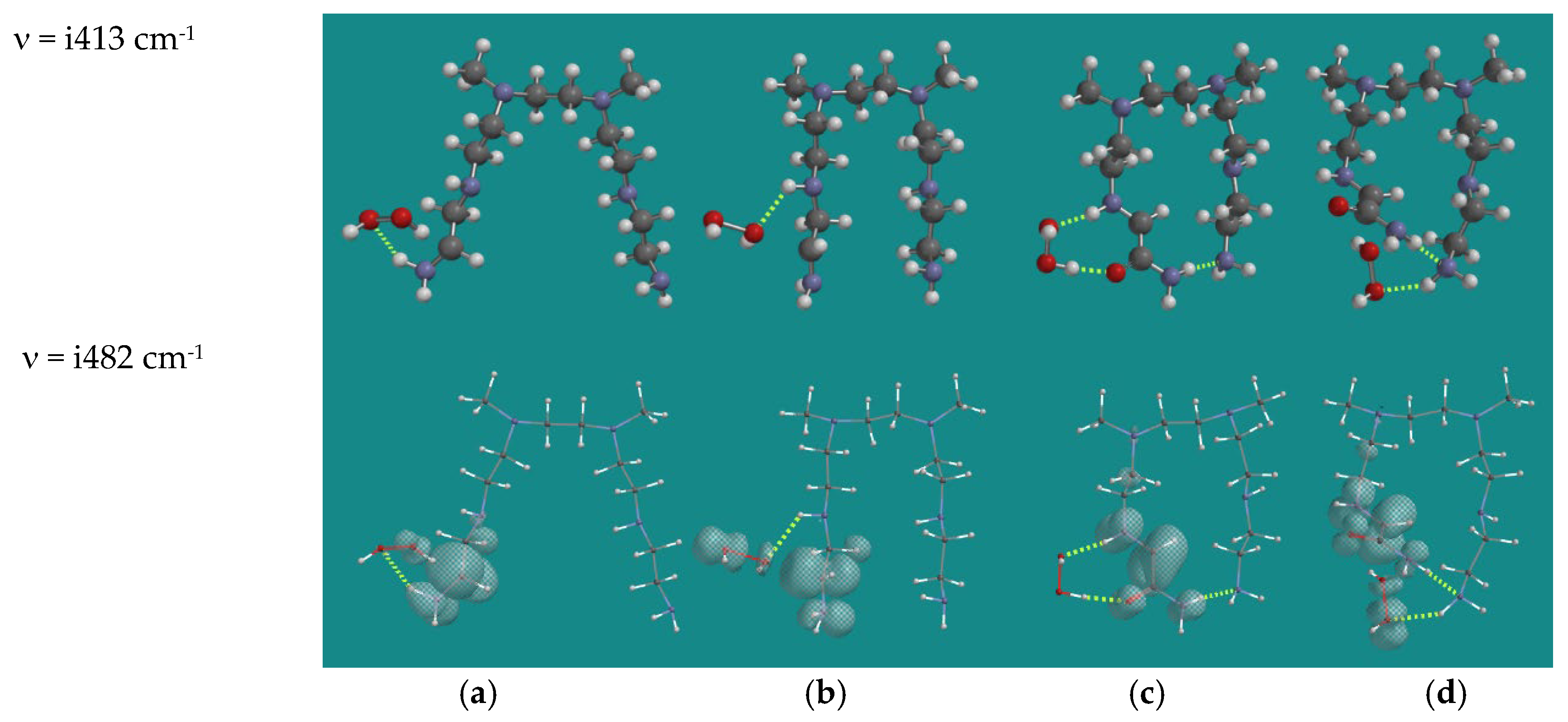

| 15 | N1-a-H | HO2•(d) | 92.9 | i1507 |

| 16 | N1-b-H | HO2•(d) | 84.3 | i1375 |

| 17 | N2-b-H | HO2•(d) | 107.0 | i1510 |

| 18 | N3-b-H | HO2•(d) | 85.1 | i1524 |

| 19 | N1-amide | HO2•(d) | 70.6 | i1223 |

| 20 | N2-amide | HO2•(d) | 100.0 | i1668 |

| 21 | N3-amide | HO2•(d) | 83.1 | i1643 |

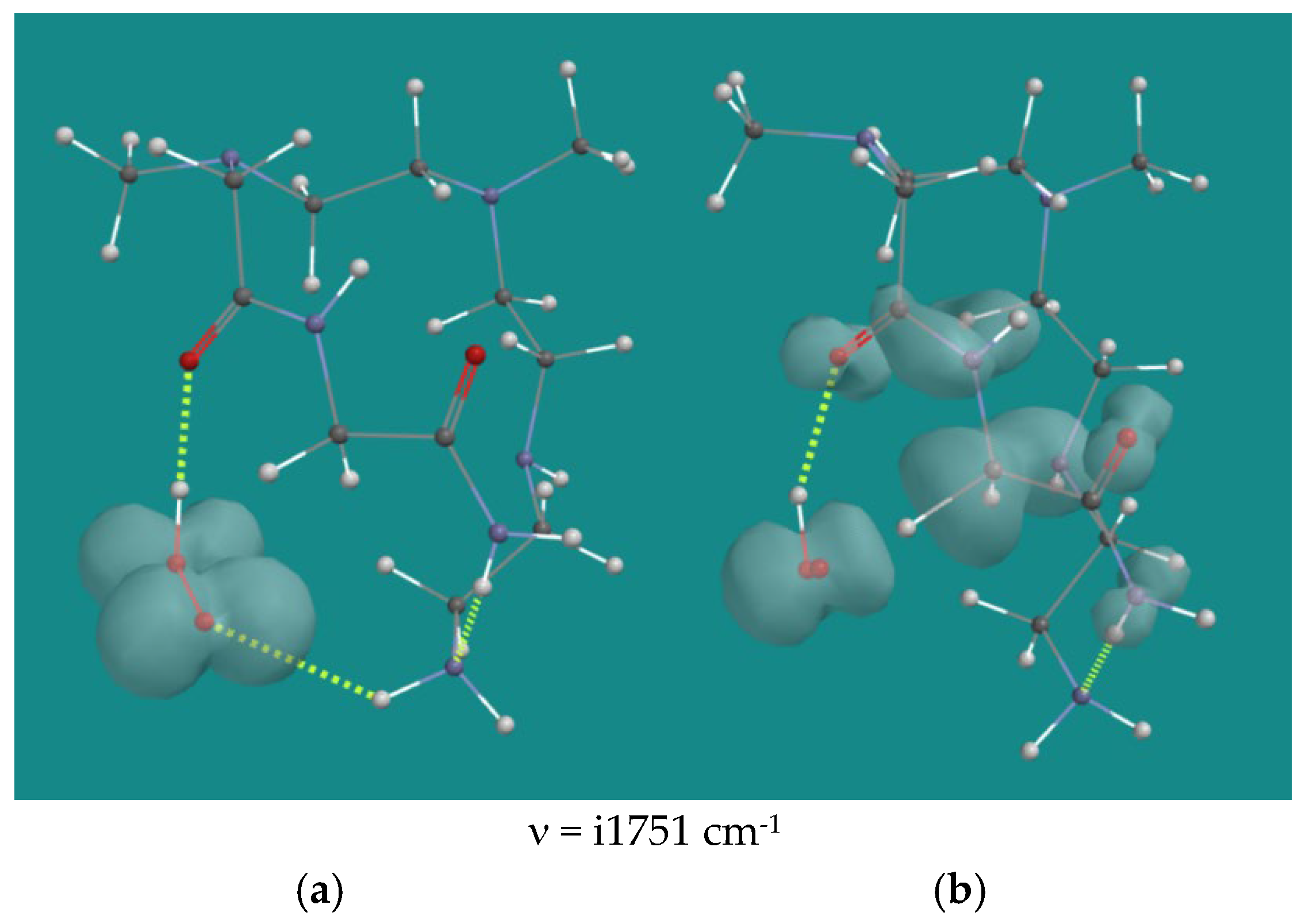

| 22 | N1,N2-diamide | HO2•(d) | 85.8 | i1751 |

| N,N-3,4-dimethyl N6 pentamer radical | DH H2O2 (kJ/mol) | Ea H2O2 (kJ/mol) | [H2O2]/[O2] | k-H2O2/k-O2 | r -H2O2/r-O2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1-a-amino radical | -35.4 | 37.1 | 9.37*103 | 1.90*10-5 | 1.78*10-1 |

| N1-amide-b-radical | -59.3 | 60.8 | 1.04*107 | 1.83*10-8 | 1.89*10-1 |

| N1,N2-diamide N1-b-radical | -58.2 | 90.9 | 7.40*106 | 2.70*10-12 | 2.00*10-5 |

| N,N-3,4-dimethyl N6 pentamer | n TS | Ea H-abstraction | DH H-abstraction | DH C-C cleavage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| cm-1 | kJ/mol | |||

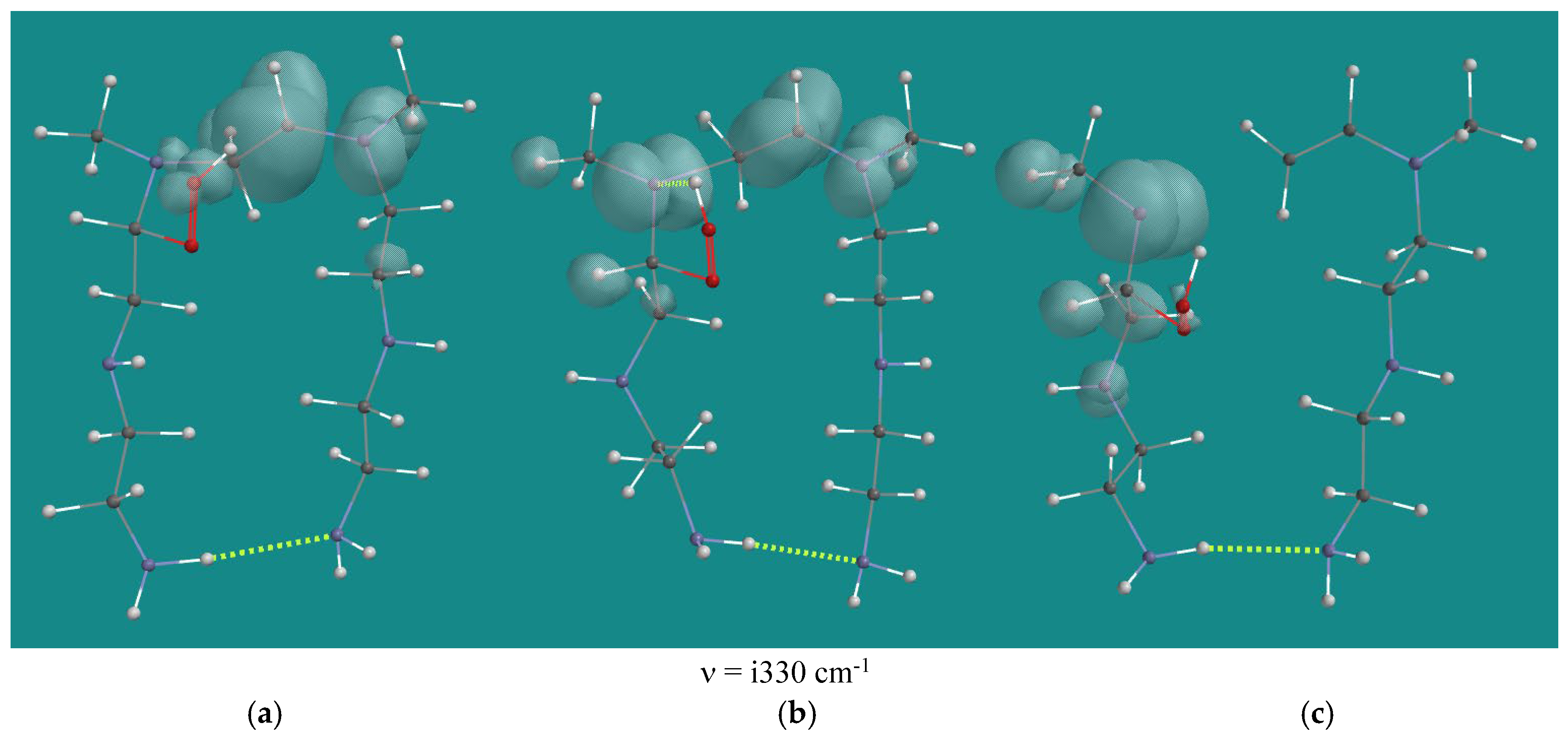

| N1-a-amino oxy radical | i615 | -1.9 | -39.2 | -92.0 |

| N2-a-amino oxy radical | i1310 | 25.3 | -22.4 | -116.2 |

| N2-b-amino oxy radical | i325 | 0.9 | -36.6 | -113.1 |

| Name | PEI unit | Mw | H/(C+N) | N/C | n | c-H/(C+N) | c-N/C | c-Mw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| g/mol | g/mol | |||||||

| pristine | CH2CH2NH | 43 | 1.67 | 0.50 | 1.5 | 2.50 | 0.75 | 64.5 |

| amide | C=O-CH2NH | 57 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 6.0 | 6.00 | 3.00 | 342.0 |

| half aminal | CH(OH)-CH2NH | 59 | 1.67 | 0.50 | 2.0 | 3.33 | 1.00 | 118.0 |

| imine | CH2CH=N | 41 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.5 | 1.50 | 0.75 | 61.5 |

| imine-NH3 | CH2CH | 27 | 1.50 | 0.00 | 3.0 | 4.50 | 0.00 | 81.0 |

| imine-amide | C=O-CH=N | 55 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 1.0 | 0.33 | 0.50 | 55.0 |

| Sum | 15.0 | 1.21 | 0.40 | 722.0 | ||||

| Exp. values | 15.0 | 1.25-1.50 | 0.42-0.43 | 725.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).