1. Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a highly lethal form of human cancer. The incidence and mortality rates for PDAC are remarkably similar, which underscores its severely malignant nature. Projections for 2024 indicated that there would be approximately 66,440 new diagnoses and 51,750 deaths in the United States directly attributable to PDAC [

1]. Although a variety of therapeutic regimens have been implemented in the adjuvant or neo-adjuvant setting of PDAC, including single-agent therapies and the combination of cytotoxic compounds such as FOLFIRINOX or nab-paclitaxel, surgical resection remains the only effective therapeutic approach for this disease [

2,

3,

4]. PDAC is the 3rd leading cause of cancer-related death and its dismal prognosis is closely associated with late diagnosis, commonly done in the advanced stages of the disease, when patients are no longer eligible for surgical resection [

5,

6,

7].

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs with a length of 19-24 nucleotides that act as negative regulators of gene expression. They exert a pivotal role in a wide range of biological processes and their aberrant expression has been detected in a great number of malignancies, including PDAC [

8,

9,

10,

11]. In cancer, the effect of miRNAs depends on their specific targets, and they can therefore have tumor-promoting (oncomiRs) or tumor-suppressing functions. In the context of PDAC, early diagnosis is crucial to improving therapeutic outcomes and patient survival. In this regard, miRNAs could serve as excellent diagnostic candidates due to their remarkable stability in body fluids and their significant biological roles [

9,

10,

11]. Their presence in circulation, shielded from endogenous RNase activity, makes them particularly suitable for use as biomarkers in non-invasive diagnostic applications [

8].

Cancer Stem Cells (CSCs) share self-renewal and differentiation to different cellular lineages with normal stem cells and reside in a small niche within the tumor. According to the hierarchical model of carcinogenesis, CSCs play a crucial role in the initiation of tumors. Moreover, growing evidence has demonstrated that CSCs are key mediators of tumor progression, metastatic dispersion, tumoral recurrence, and therapy resistance [

3,

12,

13,

14]. Pancreatic cancer stem cells (PaCSCs), which constitute less than 1% of all pancreatic cancerous cells, are distinguished by their high expression levels of CD44, EpCAM, CD133, CxCR4, CD24, ALDH1, c-MET, DclK1, and Lgr5. Furthermore, the expression of PaCSC markers varies between high-grade PanIN and advanced PDAC [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

Numerous studies have investigated the role of miRNAs in PaCSCs, revealing their ability to regulate various pathways that affect the CSC phenotype by targeting specific molecules [

17,

20,

21]. We previously enlightened the dramatical dysregulation of miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p in CSC-like models [

22]. In our former research on ex-vivo and in vitro models of PDAC, we found that miR-216a-5p was overexpressed during the early PDAC stages while its expression decreased in advanced PDAC, and this behaviour suggested a potential dual role of the miRNA. In our study, miR-125a-5p performed as an oncomiR, a finding that aligns with previous literature search results. Interestingly, in CSC-like models the behaviour of the two miRNAs varied considerably from what we observed in adherent cell lines.

The intricate network of miRNA-mediated regulation in CSC pathways remains poorly understood and continued investigation is essential to advance the field of translational medicine for both diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Our work aimed to investigate the influence of miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p on the CSC phenotype by evaluating whether these molecules trigger the acquisition or regression of CSC traits. To this end, we evaluated the effect of miRNA mimic and inhibition on pluripotency and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) gene expression, the levels of PaCSC markers and anchorage-independent growth of CSC-like models. The experimental design has been carried out on adherent cell lines representatives of PDAC, and their CSC-enriched cultures.

2. Results

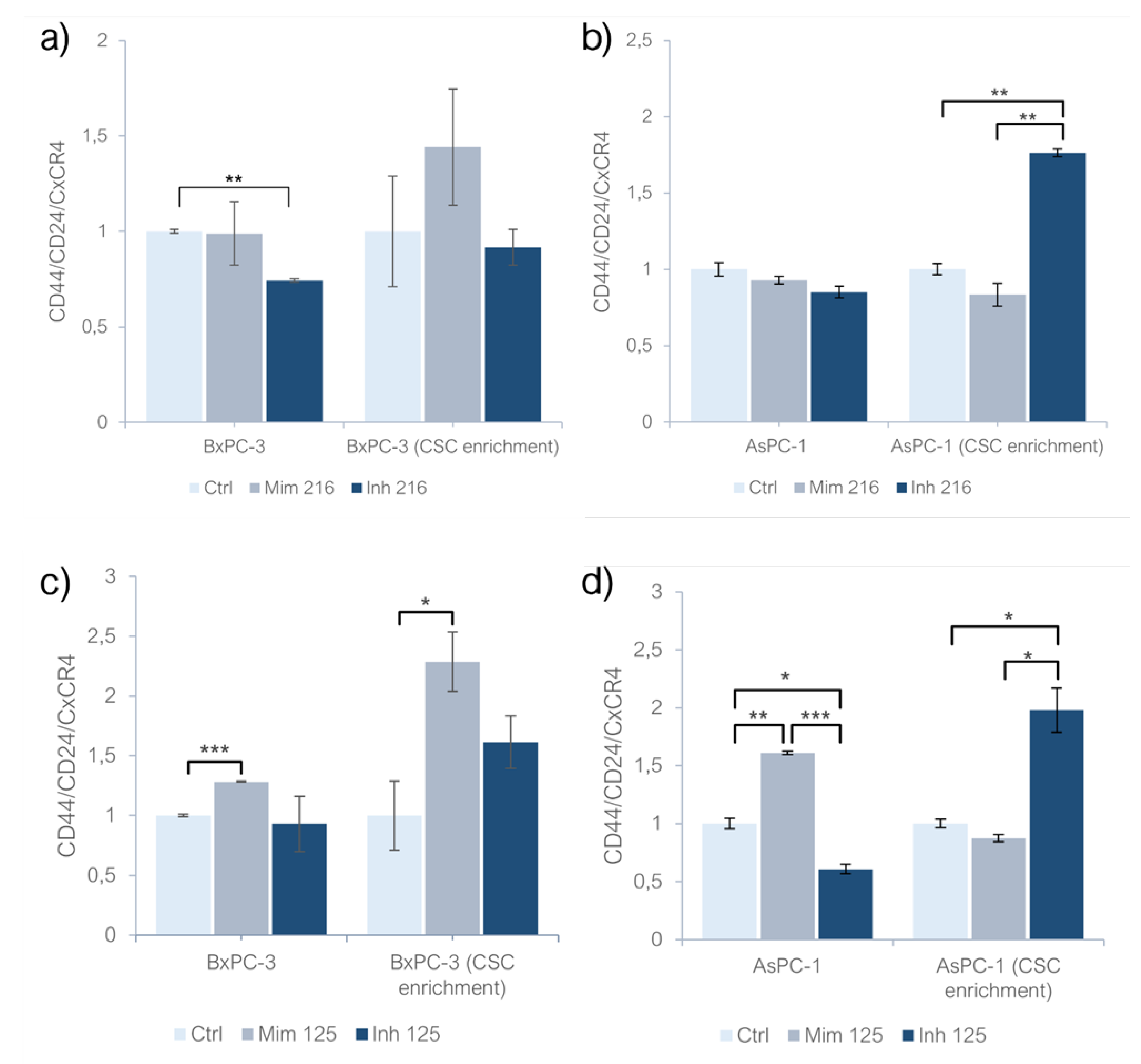

2.1.miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p Effect on CD44/CD24/CxCR4 Expression

Mimicking the miR-216a-5p effect, both adherent BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 showed no significant changes in CD44/CD24/CxCR4 expression while inhibiting it, the expression of CSC markers in both models was reduced in comparison with controls and with cells treated with mimic, with a significant difference in BxPC-3 (p<0.01). Investigating the role of this molecule on CSC-like models of BxPC-3, it was observed that the treatment with miR-216a-5p mimic induced an increased expression of PaCSC markers while the inhibition determined a decreased expression of CD44/CD24/CxCR4. On AsPC-1 CSC-like models treated with miR-216a-5p mimic, the expression decreased (n.s) while inhibiting miR-216a-5p, the expression of PaCSC markers increased in AsPC-1 CSC-like models (p<0.01) (Fig. 1a, 1b). When treating monolayer-grown cell lines with miR-125a-5p mimic, CD44/CD24/CxCR4 expression increased in both BxPC-3 (p<0.001) and AsPC-1 (p<0.01). Inhibiting miR-125a-5p, the expression of CD44/CD24/CxCR4 decreased in BxPC-3 (n.s.) and in AsPC-1 (p<0.05). On BxPC-3 CSC-like models, the effect of miR-125a-5p resulted in an increased expression of PaCSC markers (p<0.05). The same trend was observed when treating the same models with the inhibitor of miR-125a-5p but it was not statistically significant and the expression was still reduced compared to that observed in the mimic condition (n.s). In AsPC-1 CSC-like models, mimicking miR-125a-5p effect it was observed a decreased expression of PaCSC markers while the inhibition of the molecule produced an increased expression of CD44/CD24/CxCR4 (p<0.05) (

Figure 1c,d)

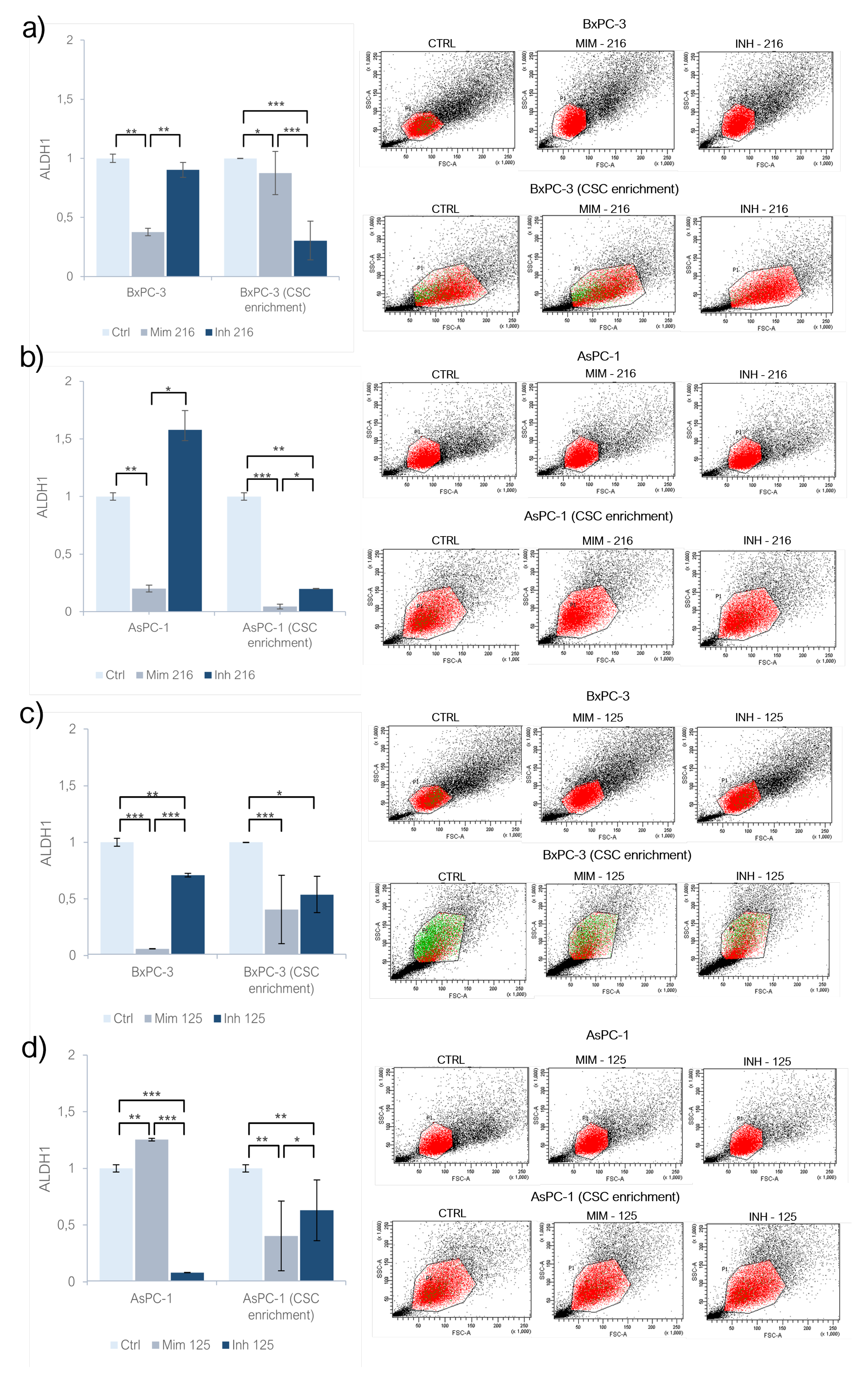

2.2.miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p effect on ALDH1 Activity

The treatment of BxPC-3 with miR-216a-5p mimic induced a decrease in ALDH1 activity (p<0.01); the same behaviour was also observed following the inhibition of miR-216a-5p but without any statistical significance and the activity of ALDH1 was still higher than the one in mimic condition (p<0.01). In AsPC-1 treated with miR-216a-5p mimic, ALDH1 activity significantly decreased (p<0.01) while following its inhibition, ALDH1 activity increased (n.s). On CSC-like models built on BxPC-3 cell lines, the treatment with miR-216a-5p mimic resulted in a decreased activity of ALDH1 (p<0.05) but this behaviour was detected also following the inhibition of the molecule: inhibiting miR-216a-5p ALDH1 activity was lower than following the treatment with mimic (p<0.001). On AsPC-1 CSC-like models, ALDH1 activity decreased after the treatment with miR-216a-5p mimic (p<0.001) and inhibitor (p<0.01) but in the last the activity was higher when compared with ALDH1 activity on models treated with mimic (p<0.05) (Fig. 2a, 2b). Following the treatment with miR-125a-5p mimic, the activity of ALDH1 was decreased in adherent BxPC-3 (p<0.001) and increased in monolayer-grown AsPC-1 (p<0.01), as compared to controls (Fig. 2c, 2d). In both inhibitor-treated cell lines, ALDH1 activity was lower than in untreated cells, with statistical significance. As compared to the mimic condition, the activity of ALDH1 following the inhibition of miR-125a-5p was higher in BxPC-3 (p<0.001) and lower in AsPC-1 (p<0.001). On CSC-like models derived from BxPC-3 (p<0.001) and AsPC-1 (p<0.01), a decrease in ALDH1 activity was observed as a result of both mimic and inhibitor treatments. In inhibitor-treated CSC-like models the ALDH1 activity was higher than the one in mimic-treated models (p<0.05) (

Figure 2c,d).

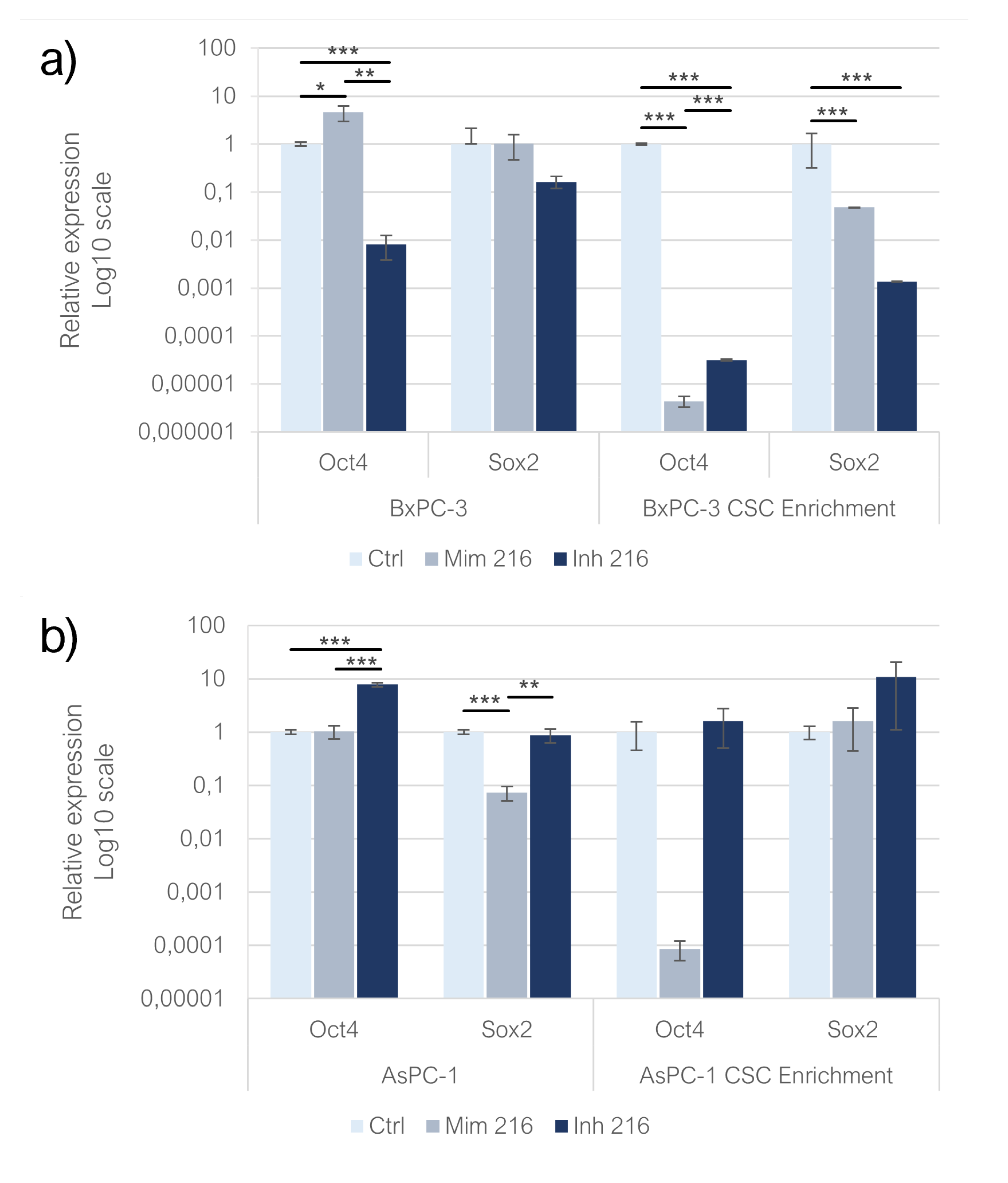

2.3.miR-216a-5p Influence on Pluripotency-Related Genes

Enhancing miR-216a-5p in adherent BxPC-3, resulted in an increased expression of Oct-4 compared to controls (p<0.05). After the inhibition of miR-216a-5p, the expression of Oct-4 strongly decreased (p<0.01). The same model treated with miR-216a-5p mimic, exhibited a mild overexpression of Sox-2 (n.s) whereas the inhibition of the miRNA induced a downexpression of the gene as compared to the control group (n.s.). In adherent AsPC-1, the expression of Oct-4 increased following the enhancement of miR-216a-5p (n.s). Following the inhibition of miR-216a-5p Oct-4 expression significantly decreased (p<0.001). In adherent AsPC-1, Sox-2 expression was decreased compared to controls following both treatments with mimic (p<0.001) and inhibitor (n.s). When comparing the expression levels between the two conditions, it was found to be overexpressed in the inhibitor condition as compared to the mimic (p<0.01). The expression of Oct-4 in CSCs derived from BxPC-3 cell line exhibited a strong reduction in both mimic and inhibitor conditions, compared to the control group (p<0.001): in the inhibitor condition, Oct-4 was overexpressed compared to cells transfected with mimic (p<0.001). Regarding the expression of Sox-2 in the same model both the treatments induced a downregulation of Sox-2 compared to controls (p<0.001): when comparing mimic and inhibitor conditions, Sox-2 expression was higher in mimic compared to inhibitor condition (p<0.001). In AsPC-1 CSC-like models, the treatment with miR-216a-5p mimic strongly affected the expression of Oct-4 which resulted downexpressed in comparison to controls (n.s). Conversely, following the inhibition of miR-216a-5p, Oct-4 resulted overexpressed compared to controls (n.s). On CSC-like models derived from AsPC-1, the treatment with mimic and inhibitor resulted in the overexpression of Sox-2 (n.s): comparing the mimic and inhibitor conditions, Sox-2 expression was higher in the latter (n.s) (

Figure 3a,b).

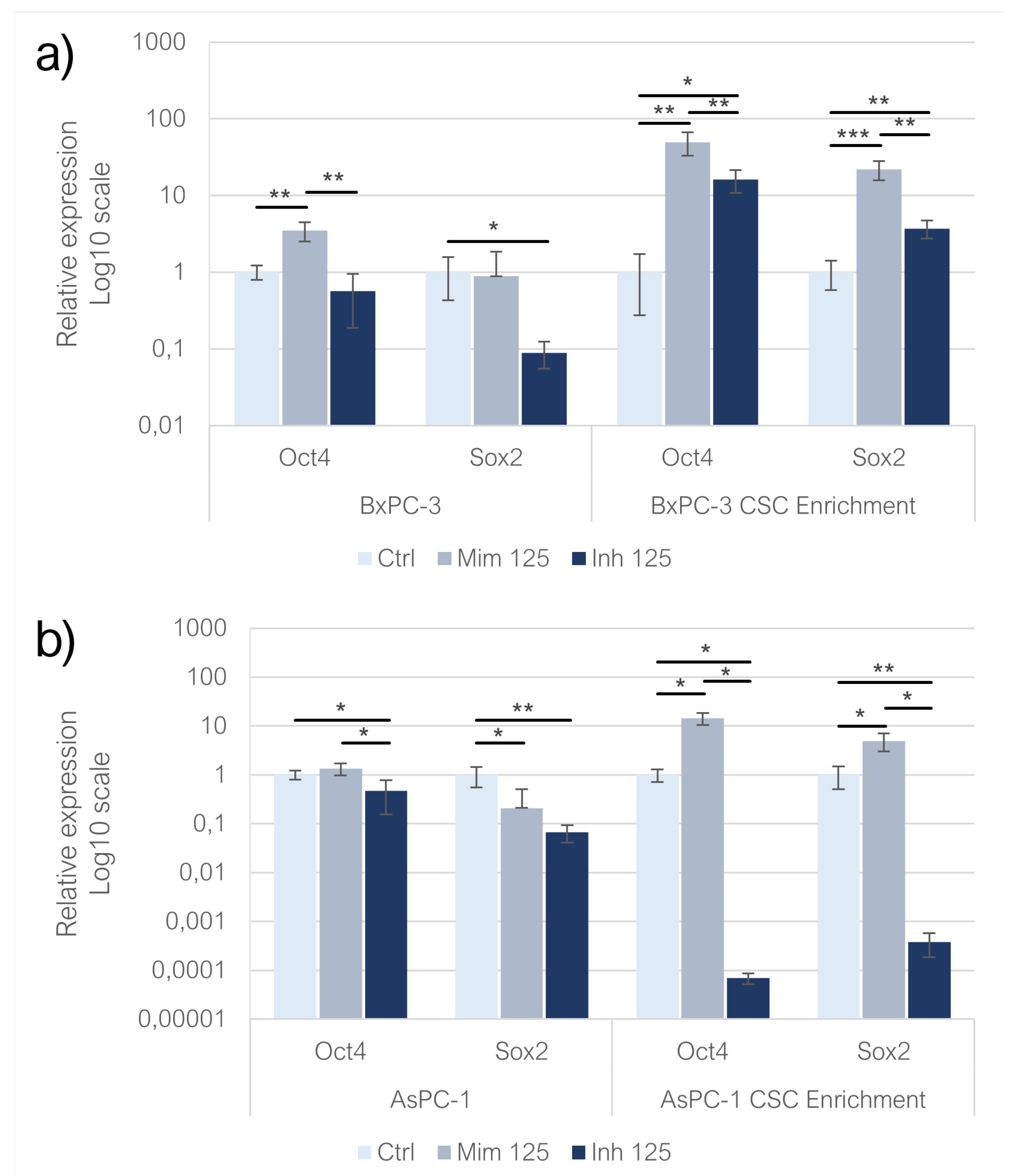

2.4.miR-125a-5p Influence on Pluripotency-Related Genes

In adherent BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 transfected with miR-125a-5p mimic, the expression of Oct-4 increased compared with the control group (p<0.01) while, in the treatment with inhibitor, Oct-4 resulted downregulated (Fig. 7a, 7b). Sox-2 was adversely affected by both mimic (n.s) and inhibitor (p<0.05) treatments in monolayer-grown BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cell lines, with a more pronounced trend following miRNA inhibition (n.s). In CSC-like models built on BxPC-3, both treatments resulted in overexpression of Oct-4 (p<0.01): the overexpression was higher following the mimic of miR-125a-5p (p<0.05). Enhancing the miR-12 5a-5p effect, CSC-derived from AsPC-1 exhibited an increase in Oct-4 expression (p<0.05) while the inhibition of the miRNA, induced a decrease in Oct4 levels (p<0.05). In both BxPC-3 (p<0.001) and AsPC-1 (p<0.05) derived CSC-like models, Sox-2 was overexpressed in mimic condition. MiR-125a-5p inhibition resulted in the overexpression of Sox-2 in BxPC-3 CSC-like models (p<0.01) and in the downregulation of the gene in CSC-enriched AsPC-1 (p<0.05) (

Figure 4a,b).

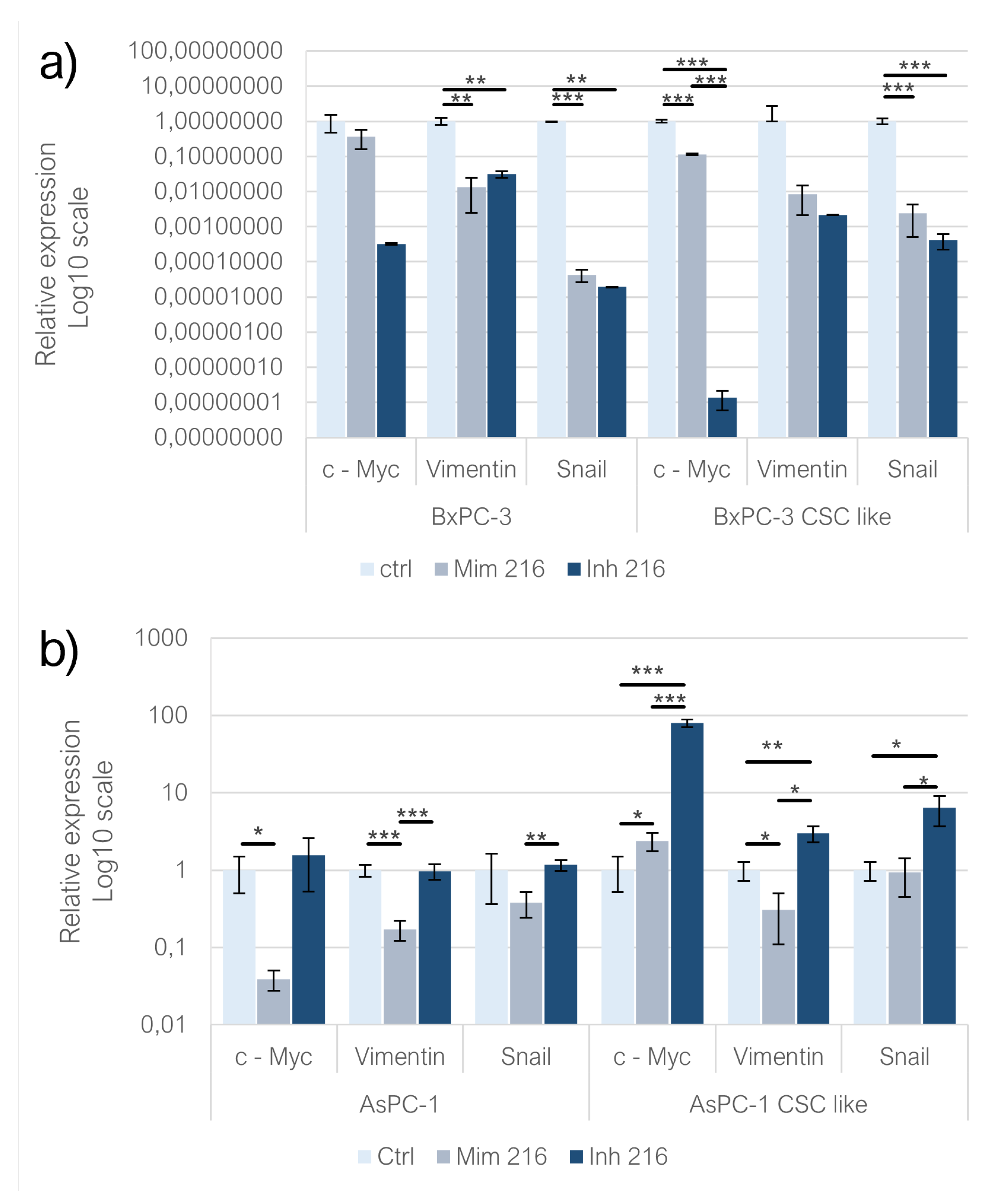

2.5. Effect of miR-216a-5p on EMT-Related Genes

C-Myc expression was decreased following the administration of both miR-216a-5p mimic and inhibitor in adherent BxPC-3 (n.s). Upon comparing the expression levels of c-Myc in both conditions, it was observed that its expression increased with the mimic of miR-216a-5p in comparison to the inhibition of the miRNA (n.s). In the BxPC-3 derived CSC-like model, the behavior of c-Myc was consistent with observations made in monolayers-grown BxPC-3, with both mimic and inhibitor treatments resulting in a decreased c-Myc expression (p<0.001) compared to controls; miR-216a-5p mimic treatment led to higher levels of the gene compared to the inhibitor condition (p<0.001). In adherent AsPC-1 treated with mimic, the expression of c-Myc decreased significantly (p<0.05) while it was overexpressed following miR-216a-5p inhibition (n.s). On CSC-like models built on AsPC-1, both mimic (p<0.05) and inhibitor (p<0.001) treatments induced an overexpression of c-Myc, with a more pronounced trend following miRNA inhibition (p<0.001). The expression of Vimentin was affected by the treatment with miR-216a-5p mimic and inhibitor in adherent BxPC-3 (p<0.01) and AsPC-1 (n.s) and in BxPC-3 derived CSC-like model (p<0.001). In adherent BxPC-3, when comparing the mimic and inhibitor conditions, Vimentin levels were higher following the inhibition of miR-216a-5p (n.s). The same behavior was reflected in inhibitor-treated adherent AsPC-1(p<0.001). In AsPC-1 CSC-like models, the mimic of miR-216a-5p resulted in a decrease of Vimentin expression (p<0.05) whereas the inhibition of the miRNA induced the overexpression of the EMT gene (p<0.05). Both miR-216a-5p mimic (p<0.001) and inhibitor (p<0.01) resulted in Snail downregulation on adherent BxPC-3 cells and their CSC-like model (p<0.001). In both cell models, the condition treated with miRNA inhibitor schowed decreased Snail expression compared to the mimic one. In adherent AsPC-1, miR-216a-5p mimic treatment resulted in a downregulation of Snail (n.s) while the administration of the inhibitor induced the overexpression of the EMT gene (n.s). On CSC-like models derived from AsPC-1, the trend observed was the same as for monolayer-grown AsPC-1 (

Figure 5).

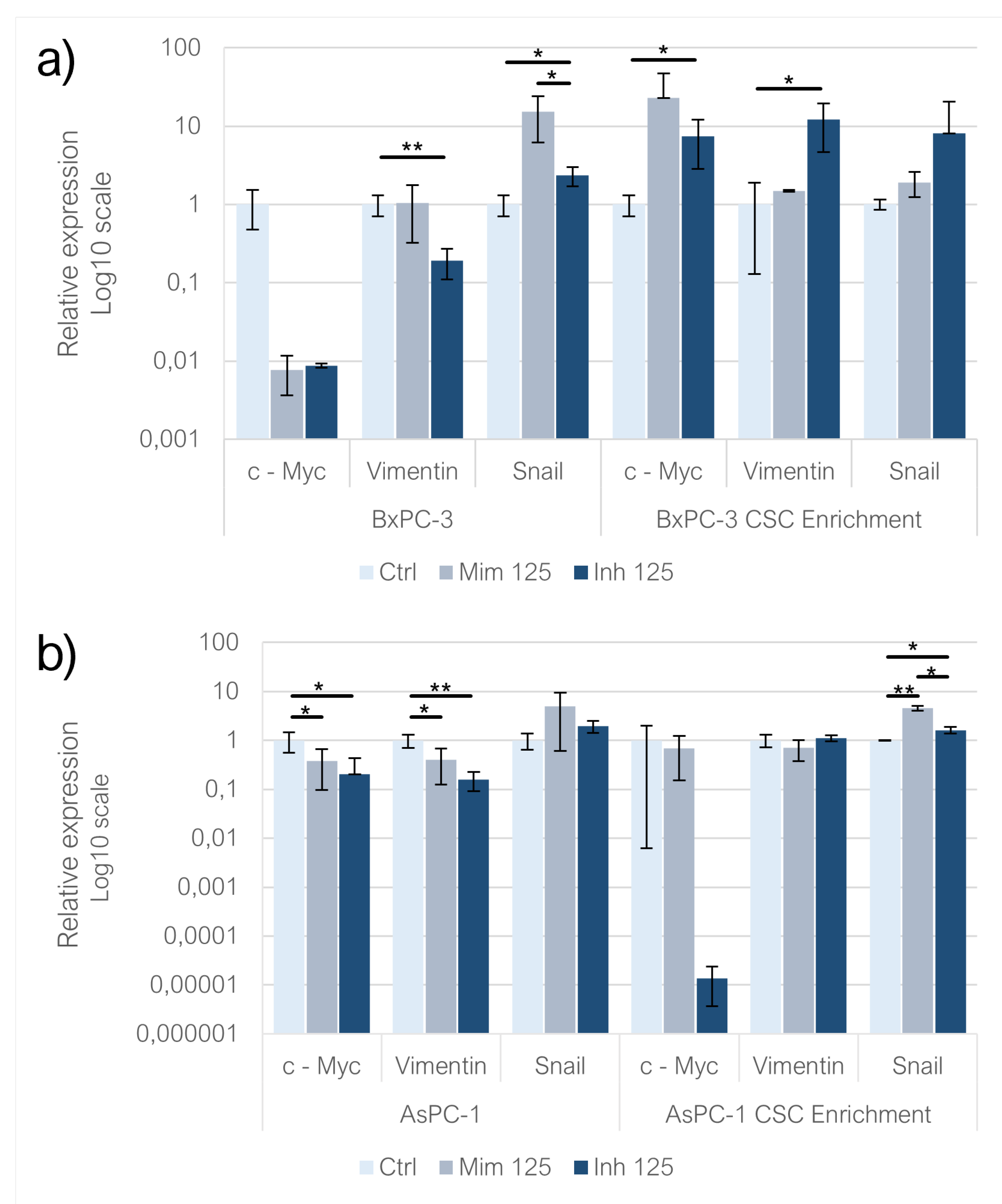

2.6. Effect of miR-125a-5p on EMT-Related Genes

In BxPC-3 cultured in monolayer, both the two treatments negatively affected the expression of c-Myc (n.s) and in the inhibitor condition, its levels were higher than in the mimic one (n.s). In CSC-like models, the behaviour observed was exactly the opposite: the two treatments induced the overexpression of c-Myc and it was statistically significant in the inhibitor condition (p<0.05). When comparing the mimic and inhibitor, c-Myc levels were higher in the mimic condition than in the inhibitor one (n.s). In AsPC-1 cell models, such as in BxPC-3, the two treatments induced the downregulation of c-Myc (p<0.05) but following the mimic treatment, c-Myc levels were higher than in cells transfected with inhibitor (n.s). The same trend was noticed in CSC-like AsPC-1 models (n.s). In the BxPC-3 cell line, Vimentin levels increased compared to controls after the miR-125a-5p mimic transfection (n.s) and they were significantly decreased following the miRNA inhibition (p<0.01). In CSC-like models, in both mimic and inhibitor conditions, Vimentin expression increased compared to controls (n.s) and this trend was more pronounced in inhibitor compared to mimic (n.s). In AsPC-1 cell line, mimic (p<0.05) and inhibitor (p<0.01) treatments resulted in a decreased Vimentin expression compared to controls. When comparing Vimentin levels between mimic and inhibitor conditions, they were higher in the first (n.s). On CSC-like models, Vimentin levels decreased following miR-125a-5p mimic transfection while they increased following the inhibition of the microRNA (n.s). Regarding Snail expression in BxPC-3 treated with both mimic (n.s) and inhibitor (p<0.05) its expression increased compared to controls and was more pronounced following the enhancement of miR-125a-5p effect compared to controls (p<0.05). In CSC-like models, the same behaviour was noticed (n.s) but considering the comparison between mimic and inhibitor condition, Snail expression was higher in the last (n.s). In AsPC-1 Snail levels were higher compared to controls in both mimic and inhibitor conditions (n.s) and comparing the two treatments, Snail levels were higher following the mimic treatment (n.s). In CSC-like models built on this cell line, the behaviour was the same: following the treatment with both mimic (p<0.01) and inhibitor (p<0.05) Snail levels increased compared to controls and, comparing the two conditions, it was higher in mimic (p<0.05) (

Figure 6).

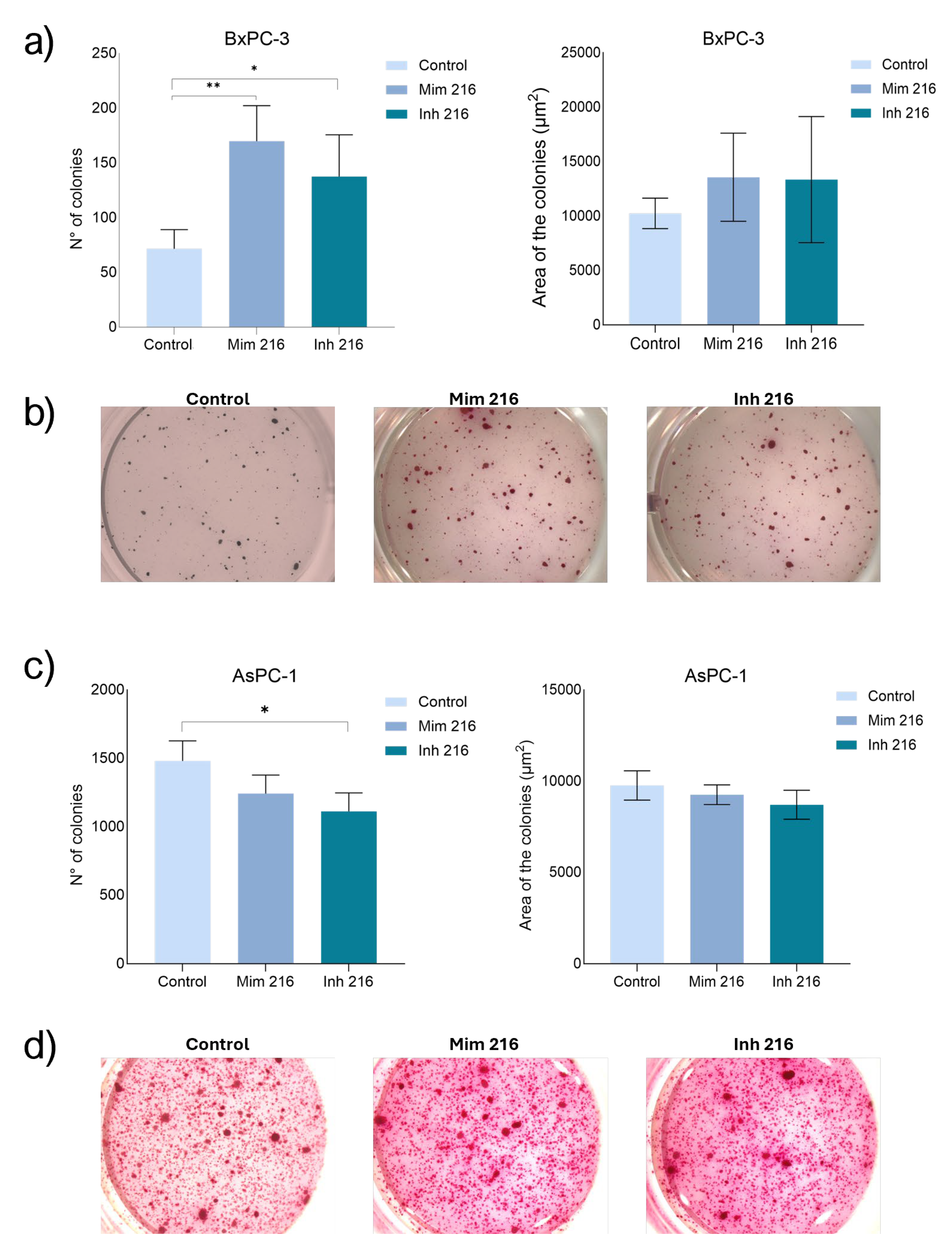

2.7. The role of miR-216a-5p on Clonogenic Activity

The treatment of BxPC-3 CSC-like cells with miR-216a-5p mimic induced an increased number of colonies if compared with the control (p<0.01) and with the cells treated with inhibitor (n.s.). The cells treated with the inhibitor of miR-216a-5p, showed a number of colonies higher than the one in controls (p<0.05). A similar behaviour was also observed regarding the area of the colonies: higher values were reported following mimic treatment compared to controls (n.s). Treatment with the inhibitor is however associated with larger colonies compared to controls, but in any case, smaller than the ones in mimic condition (n.s.). AsPC-1 CSC-like models showed fewer colonies in both mimic (n.s) and inhibitor (p<0.05) conditions: the number of colonies detected following the treatment with mimic was higher than the number in the inhibitor condition, but this difference wasn’t statistically significant. When considering the area of the colonies, following the treatments with mimic they were smaller than in controls. When inhibiting miR-216a-5p the area was smaller than in mimic condition (

Figure 7).

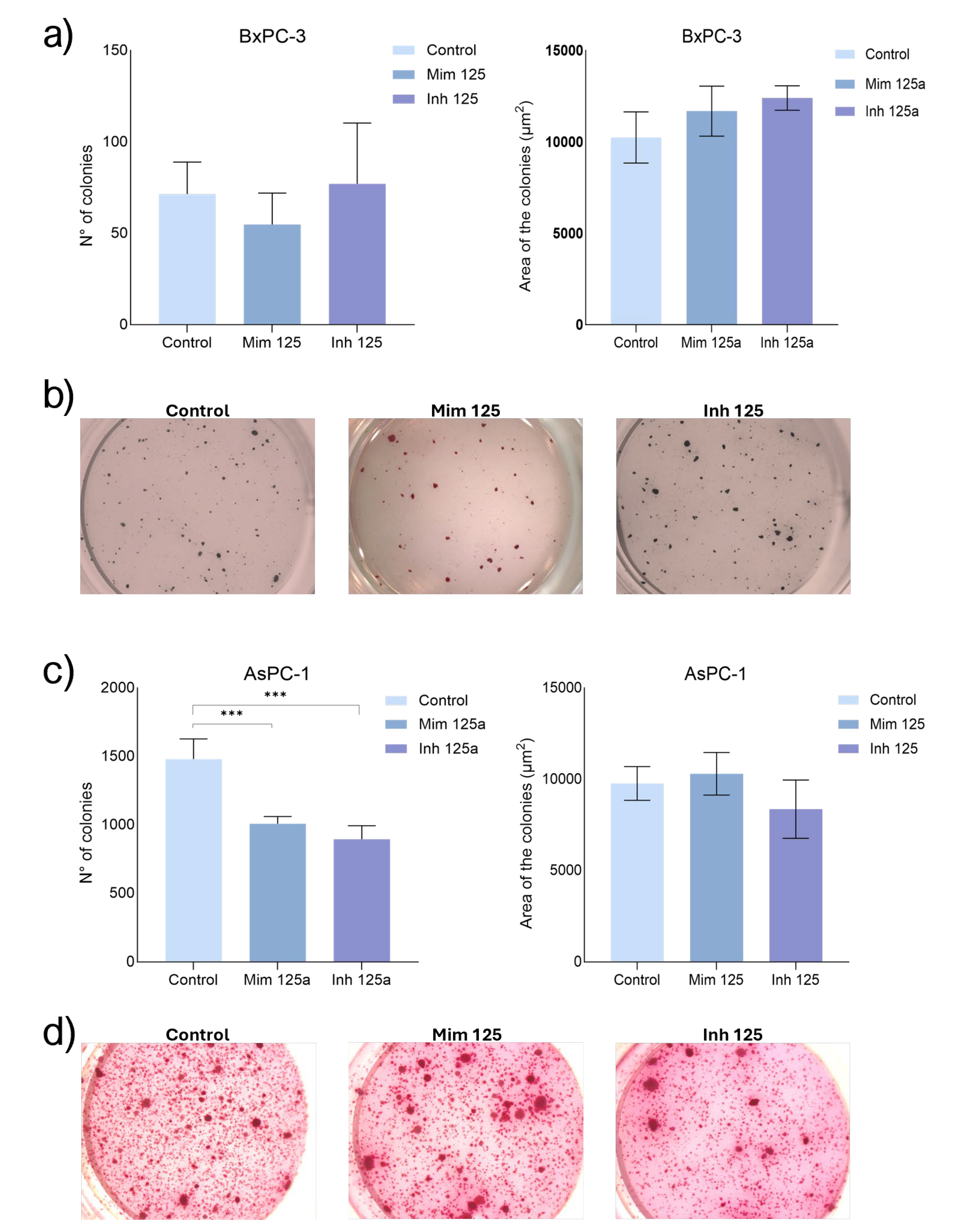

2.8. The Role of miR-125a-5p on Clonogenic Activity

Enhancing miR-125a-5p effect on BxPC-3 CSC-like models, the number of colonies decreased compared to controls and those treated with miR-125a-5p inhibitor (n.s.) while the last showed an increased number of colonies with respect to the controls (n.s.). The area of the colonies increased in both conditions compared with control (n.s.), with no difference between them. On AsPC-1 CSC-like models, the treatment with miR-125a-5p mimic resulted in fewer colonies comparing with controls (p<0.001). The same behaviour was observed following the treatment with the inhibitor of miR-125a-5p (p<0.001) and in this condition, the colonies were lower than in mimic (n.s). Regarding the size of the colonies, the enhancement of miR-125a-5p resulted in a higher area of the colonies while following the inhibition of miR-125a-5p they were smaller than in controls and in mimic (n.s) (

Figure 8).

3. Discussion

The current study builds upon our previous research regarding the involvement of miRNAs in PDAC [

22]. Our prior findings enabled us to focus on miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p for functional investigation. Multiple research efforts have documented the downregulation of miR-216a-5p in PDAC cases, and various intricate regulatory mechanisms have been proposed to elucidate its potential oncosuppressive role [

27,

28,

29,

30]. The involvement of miR-125a-5p in cancer has been extensively investigated, with often contradictory findings. Despite this, its role in PDAC remains poorly explored [

31]. Given our previous results reporting a significant deregulation of these miRNAs in PaCSC models and considering the critical role of CSCs in tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis, we deemed it necessary to evaluate miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p effects on the acquisition or regression of CSC traits [

22]. To this end, we focused on the influence of the miRNAs on the expression of stemness markers, pluripotency, and EMT genes on adherent BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 and their CSC-enriched spheres, as well as on anchorage-independent growth of PaCSC models.

It has been reported that, in physiological conditions, miR-216a-5p is abundant in pancreatic acinar cells and that its levels could vary following cellular degeneration and necrosis [

32,

33]. In PDAC, miR-216a-5p levels have been frequently found to be downregulated and it has been described as an oncosuppressive miRNA. Furthermore, Felix et al. reported that the molecule targets IL-6, a cytokine whose levels are frequently increased in PDAC and associated with poor prognosis. Despite extensive research on the role of miR-216a-5p in PDAC and other types of cancer, its potential connection with PaCSCs and their associated markers CD24/CD44/CxCR4 and ALDH1 remains unexplored. In breast cancer, miR-216a-5p has been reported as a negative regulator of EMT, ALDH expression, and stemness genes and has been demonstrated that it exerts its role by educating the tumoral microenvironment through cytokine production [

27,

28,

34,

35]. In our study, miR-216a-5p promoted the expression of CD24/CD44/CxCR4 on both adherent BxPC-3 and their CSC-enriched spheres, and a trend of positive influence was also identified in AsPC-1 CSC-like models. Nevertheless, ALDH1 expression was affected by miR-216a-5p. Concerning EMT, our results on the AsPC-1 cell line showed that miR-216a-5p inhibited c-Myc, Snail, and Vimentin expression. In BxPC-3, this behaviour was mirrored for Vimentin. The negative influence of miR-216a-5p on EMT has already been described in prostate cancer, where the overexpression of the miRNA reduced N-cadherin, Vimentin, and Snail levels [

36]. Furthermore, we observed that the effect of miR-216a-5p on pluripotency genes changed depending on the cell lines and the phenotypes considered: only on adherent BxPC-3 miR-216a-5p seemed to exert a promotive influence, while on BxPC-3 enriched in CSCs and on adherent and CSC-like AsPC-1, the miRNA had an inhibitory effect. The differences in the role of miRNA between the two cell lines and their phenotypes may also originate in their different ability to metastasise [

37]. Indeed, whereas the BxPC-3 cell line is representative of the primary tumor and has low metastatic activity, the AsPC-1 cell line is representative of metastatic PDAC and is characterised by high metastatic activity. Although further studies are needed, these findings lead us to think that miR-216a-5p may exert an inhibitory role on cells with greater malignancy. Concerning the anchorage-independent growth, miR-216a-5p exhibited a promoting influence on the number and size of the colonies of both cell lines. Our previous findings showed that the expression of miR-216a-5p in PDAC may change as the disease evolves, probably suggesting a shift from a promoting function in the early stages to a suppressive role during advanced disease [

22]. Our observation is coherent with Petrovic et al, who in their study showed how the expression levels of a miRNA can vary during tumor progression, following a time profile [

38]. Even if not with miR-216a-5p, the same phenomenon has also been described by Xiang et al, and Ota et al who enlightened how members of the miRcluster miR-17/92 can simultaneously act as oncogenes and oncosuppressors: it has been proposed that these molecules try to maintain equilibrium by inhibiting translation of pro-proliferative and anti-proliferative genes; consequently, an imbalance in their expression levels, in both directions, may induce tumorigenesis [

38,

39,

40]. The results of this functional study agree with our previous hypothesis concerning a potential dual behaviour of miR-216a-5p in PDAC. Indeed, we have observed that its effect may vary depending on the models and phenotypes considered. In our opinion, this may suggest how the role of miR-216a-5p may vary according to the grade of malignancy of the model considered and thus the progression of the disease. However, further studies are needed to better clarify it.

In the case of mir-125a-5p, previous studies demonstrated that its levels were upregulated in CD133

+ cells from patients with hepatocellular carcinoma compared to the control group. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that this molecule exhibits an antiapoptotic effect on hematopoietic stem cells [

41,

42]. Our findings suggest that miR-125a-5p may stimulate the expression of CD44/CD24/CxCR4, it happened in all the cellular models analysed with the sole exception of AsPC-1-derived CSC-enriched spheres. The miRNA exerted an inhibitory trend on ALDH1 expression. The existing literature concerning the potential impact of miR-125a-5p on EMT is rather heterogeneous [

43,

44]. In their research, Chen et al demonstrated that miR-125a-5p promotes PDAC progression by activating the ERK/EMT signalling pathway [

45]. In colorectal cancer (CRC), Zhu et al. demonstrated that miR-125a-5p enhances the EMT process through the targeting of DDB2, an EMT suppressor [

46]. Nevertheless, it has been reported that in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma, miR-125a-5p inhibits the EMT by targeting Stat3 and it resulted in enhanced cytotoxicity of cisplatin [

47]. Our results showed that miR-125a-5p exhibits an inhibitory trend on Vimentin expression in both adherent and CSC-like models while enhancing Snail expression in the same conditions. In agreement with our observation on EMT genes, it has been demonstrated that in liver cancer miR-125a-5p overexpression negatively affects N-cadherin, p53, Vimentin, and VEGF expression [

48]. The differences in the effect that miR-125a-5p exhibits on Snail and Vimentin may be related to the interaction between the miRNA and different EMT-related pathways. In this regard, the complex regulatory network underlying the EMT involves various elements including transcription factors, co-transcription factors, microRNAs and epigenetic modifying enzymes. The regulation that these molecules exert on the EMT depends on and varies according to the interaction between the molecules themselves and the context in which they act [

49]. From our results, miR-125a-5p enhanced the expression of Oct-4 and Sox-2 on both cell lines and models considered. Our investigation of the impact of miR-125a-5p on clonogenic potential demonstrated that, on BxPC-3 CSC-like models the miRNA affected the number of the colonies while it exerted a positive influence on their size. The same tendence was detected also on AsPC-1 CSC-like models and it suggests that miR-125a-5p could have a potential suppressive influence on the clonogenic property, but not on the size of the colonies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Experimental Design

The in vitro models of PDAC selected for the study comprised the cell lines BxPC-3, which is representative of the primary tumor, and AsPC-1, which serves as a model for metastatic PDAC. Additionally, the BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cell lines were cultured in a sphere-forming medium to generate the respective CSC-enriched model. To assess the impact of miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p on the CSC-phenotype, the adherent cell lines and CSC-like models were transfected with either miRNA mimic or inhibitor, focusing on a single miRNA at a time. Following the transfection, the expression of PaCSC markers was assessed in all experimental conditions, along with the expression of pluripotency genes and EMT. In addition, the anchorage-independent growth of CSC-enriched models was evaluated.

4.2. Cell Lines

The cell lines BxPC-3 (ATCC CRL-1687), and AsPC-1 (ATCC CRL-1682) were purchased from ATCC and cultured following the manufacturer’s instructions. These in vitro models of PDAC were used to represent primary tumor (BxPC-3) and metastatic PDAC (AsPC-1). Both cell lines were grown in RPMI 1640 Medium with ATCC modification (Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) supplemented with 10% of FBS. The cells were maintained in the incubator under standard conditions at 37°C with 5% CO2.

4.3. CSC Enrichment

To acquire a subpopulation of pancreatospheres enriched in CSC, the BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cell lines were cultured following the patented protocol WO2016020572A1 [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]. To obtain the spheres, the protocol was carried out using Ultra-Low Attachment Six-Well Plates (Corning® Costar®, USA) with DMEM F/12 without FBS and supplemented with the following components: 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Pen-Str P-0781; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), 4 ng/mL heparin (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany), 1 µg/mL hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 µg/mL insulin (Insulin–Transferrin–Selenium, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA ), 1 X B27 (B-27™ Supplement [50×], Vitamin A; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Before cell seeding, the CSCs medium was supplemented with 10 ng/mL of Epidermal Growth Factor (Sigma-Aldrich), 10 ng/mL of Interleukin-6 (Miltenyi, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), 10 ng/ml Hepatocellular Growth Factor (Miltenyi) and 10 ng/mL of Fibroblast Growth Factor (Sigma-Aldrich). After 72h, primary spheres were separated using trypsin or a syringe. Following disaggregation, the cells were re-seeded in low attachment multi-well plates in spheres conditioned medium for an additional 72 hours, before further use.

4.4. Transient Transfection with miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p

The transfection of adherent BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 cell lines and their respective CSC-like models was carried out using the transfection reagent TransIT-X2 Dynamic Delivery System (Mirus Bio - Madison, WI 53719 USA) in Opti-MEM I Reduced-Serum Medium (Gibco™, New York, USA). To mimic and inhibit the two molecules, miR-216a-5p miRCURY LNA miRNA Mimic, miR-125a-5p miRCURY LNA miRNA Mimic, miR-216a-5p miRCURY LNA miRNA Inhibitor and miR-125a-5p miRCURY LNA miRNA Inhibitor were purchased from Qiagen (Hilden, Germany) and used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Adherent BxPC-3 and AsPC-1 were seeded 18-24 hours before transfection while for CSC-like models, cell seeding was carried out on secondary spheres. MiRNA mimic and inhibitor complexes were added with Opti-MEM at final concentrations of 5nM and 50nM per well, respectively, along with 1.5µL and 1µL of TransIT-X2. After an incubation period of 15-30 minutes, TransIT-X2:miRNA complexes were distributed to the plated cells. After 72h cells were harvested and used for the analysis. Transfection efficiency was evaluated using Negative Control miRCURY LNA miRNA Mimic – 5’ FAM (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for the mimic treatment and Negative control A – 5’ FAM for the inhibitor one. For the transfections on CSC-like models, the same procedure was followed, but the number of cells seeded was 2.5–5.0 × 105 cells on each well and the volume of transfection reagent used was 2µL for both treatments.

4.5. Cytofluorimetric Assays for PaCSCs Markers

The ALDEFLUOR™ kit assay (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada) was used following manufacturer’s instructions to identify cells that, as CSCs, express high levels of ALDH1 enzyme. The cell-surface levels of CD24, CD44 and CxCR4 were detected using anti-human CD24 antibody conjugated with phycoerythrin (PE), anti-human CD44 antibody conjugated with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and anti-human CxCR4 (CD184) conjugated with allophycocyanine (APC). Antibodies were purchased from (Miltenyi Biotec) and used following manufacturers’ instructions. Briefly, cells were washed, and the pellet was resuspended in 98 µL of PBS/BSA/EDTA buffer with the addition of 2µL of antibody. The PBS/BSA/EDTA buffer was obtained by diluting the MACS BSA Stock Solution (Miltenyi Biotec) 1:20 with autoMACS® Rinsing Solution (Miltenyi Biotec). The recommended antibody dilution is 1:50 for up to 106 cells in a final volume of 100 µL. Then, the suspension was incubated for 10 minutes at 2 – 8°C in the dark. Following the incubation period, cells were washed and resuspended in the analysis buffer.

4.6. RNA Extraction and Retrotranscription

Cells were homogenized through 1000 µL of TRIZOL (Sigma-Aldrich) reagent. Following an incubation period of 15 minutes and the addition of 200 µL of chloroform, the tube was shaken vigorously and placed at room temperature for 10 minutes. At the end of this period, the suspension was centrifuged at 4°C for 15 minutes and then the upper phase was transferred into a new tube. Following the addition of 500 µL of isopropanol, the tube was vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 10 minutes. It was centrifuged at 12000 x G for 10 minutes, at 4°C. Then, the supernatant was eliminated and 1000 µL of ethanol 75% were added. The tube was shaken vigorously with vortex and centrifuged at 4°C, 17000 x G for 5 minutes. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was dried. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 20 µL of nuclease-free water. The quantity of RNA extracted was evaluated at the Nanodrop (NanoDrop™ 2000/2000c Spectrophotometers, Thermo Scientific ™). To proceed with reverse transcription the kit GoScript™ Reverse Transcriptase (Promega) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. First, the RNA extracted was diluted and submitted to a first reverse transcription cycle, at 70°C for 10 minutes. Then, add to the RNA 10 µL of the RT mix, composed as follows: MgCl2, Reaction buffer, dNTPs, Primers, Enzyme (AMV), and Ribonuclease inhibitors. Then, the second reverse transcription cycle was carried out for 30 minutes.

4.7. Real – Time PCR

The cDNA was diluted to a final concentration of 5ng/µL. The influence of miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p on stemness gene expression was evaluated with commercial primers for Nanog, Sox2, OCT-4 while the effect of the molecules on the EMT process was investigated by means c-Myc, Vimentin and Snail expression. The reactions were prepared using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Promega) and human GADPH was used as a reference gene. Each reaction was performed in triplicate. The Real-Time PCR was run with StepOne Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher, Waltham) with the following cycling conditions: 95°C for 2 minutes (PCR initial heat activation), 95°C for 10 seconds (denaturation), 56°C for 60 seconds (Combined annealing/extension) for 40 cycles. Data were analyzed using the 2-∆∆Ct method and statistically evaluated with a two-sided non-paired T Student’s test considering significant results with a p-value<0.05.

4.8. Soft-Agar Colony Formation Assay

To study colony formation capacity, we disaggregated and seeded 20000 secondary CSCs in 0.4% cell agar base layer with DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in a 24-well culture plate, which was on top 0.8% base agar layer. We refreshed every 5 days with DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Cells were then incubated for a further 21 days at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Cell colony formation was then counted under a light microscope after staining with 1 mg/mL iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) overnight at 37 °C. Then, wells were washed with PBS 1X. The count and the analysis of the colonies were carried out using a dissecting microscope and the ImageJ software (version number 1.54d).

4.9. Statistical Analysis

The reported results are all inferred from at least three replications and are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical significance was obtained by applying a two-sided non-paired Student’s. Results with p<0.05 were deemed significant.

5. Conclusions

Our results highlighted the impact of miR-216a-5p and miR-125a-5p on the adherent pancreatic tumoral cell lines, as well as their CSCs-enriched models. Compared to the starting hypothesis, the observed results indicate that miR-216a-5p may have a dual behaviour during PDAC progression, but further studies are needed to characterize it. Furthermore, our evidence suggests that miR-125a-5p encourages disease progression, through the promotion of the CSC phenotype. A noteworthy limitation is that the results obtained for each molecule do not respond exclusively to miRNA mimic and miRNA inhibitor treatment but are also affected by the distinct mutational profiles of the two cell lines. The evidence reported contributed to clarifying the regulatory influence of miRNAs in the complex PDAC scenario, particularly on pancreatic CSC-enriched models, closely related to progression and metastasis. We strongly believe that investigating the involvement of miRNAs in the CSC phenotype may pose the basis for the development of targeted therapies against this subset of cancerous cells and their related pathways.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Grazia Fenu, Carmen Griñán-Lisón, Federica Etzi, Aitor González-Titos, Andrea Pisano, Belén Toledo, Cristiano Farace, Angela Sabalic, Esmeralda Carrillo, Juan Antonio Marchal and Roberto Madeddu; Data curation, Grazia Fenu, Carmen Griñán-Lisón and Federica Etzi; Funding acquisition, Juan Antonio Marchal and Roberto Madeddu; Investigation, Grazia Fenu, Andrea Pisano and Angela Sabalic; Methodology, Grazia Fenu, Carmen Griñán-Lisón, Federica Etzi, Aitor González-Titos, Andrea Pisano, Belén Toledo, Cristiano Farace, Esmeralda Carrillo and Juan Antonio Marchal; Supervision, Juan Antonio Marchal and Roberto Madeddu; Writing – original draft, Grazia Fenu; Writing – review & editing, Carmen Griñán-Lisón, Andrea Pisano, Juan Antonio Marchal and Roberto Madeddu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| miRNA |

microRNA |

| CSC |

Cancer Stem Cell |

| PDAC |

Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma |

| PaCSCs |

Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells |

| EMT |

Epithelial-Mesenchimal Transition |

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Giaquinto, A.N.; et al. Cancer Statistics. 2024. CA Cancer J Clin 2024, 74, 12–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, L.D.; Canto, M.I.; Jaffee, E.M.; Simeone, D.M. Pancreatic Cancer: Pathogenesis, Screening, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Gastroenterology 2022, 163, 386–402.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishiwata, T.; Matsuda, Y.; Yoshimura, H.; Sasaki, N.; Ishiwata, S.; Ishikawa, N.; Takubo, K.; Arai, T.; Aida, J. Pancreatic cancer stem cells: features and detection methods. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2018, 24, 797–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, D.; Gustafsson, A.; Andersson, R. Update on the management of pancreatic cancer: Surgery is not enough. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 3157–3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lok, V.; Ngai, C.H.; Zhang, L.; Yuan, J.; Lao, X.Q.; Ng, K.; Chong, C.; Zheng, Z.-J.; Wong, M.C. Worldwide Burden of, Risk Factors for, and Trends in Pancreatic Cancer. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 744–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, A.P. Pancreatic cancer epidemiology: understanding the role of lifestyle and inherited risk factors. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 493–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, M.; Abnet, C.C.; Neale, R.E.; Vignat, J.; Giovannucci, E.L.; McGlynn, K.A.; Bray, F. Global Burden of 5 Major Types of Gastrointestinal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 335–349.e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, P.T.B.; Clark, I.M.; et al. MicroRNA-Based Diagnosis and Therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, M.; Kadian, K.; et al. MicroRNA in Pancreatic Cancer: From Biology to Therapeutic Potential. Genes (Basel) 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D.P. Review MicroRNAs: Genomics, Biogenesis, Mechanism, and Function. Cell 2004, 116, 281–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daoud, A.Z.; Mulholland, E.J.; Cole, G.; McCarthy, H.O. MicroRNAs in Pancreatic Cancer: biomarkers, prognostic, and therapeutic modulators. BMC Cancer 2019, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ercan, G.; Karlitepe, A.; Ozpolat, B. Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells and Therapeutic Approaches. Anticancer. Res. 2017, 37, 2761–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodward, W.A.; Hill, R.P. Cancer Stem Cells. Recent Results in Cancer Research 2016, 198, 25–44. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraju, G.P.; Farran, B.; Luong, T.; El-Rayes, B.F. Understanding the molecular mechanisms that regulate pancreatic cancer stem cell formation, stemness and chemoresistance: A brief overview. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 88, 67–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortoglou, M.; Miralles, F.; Arisan, E.D.; Dart, A.; Jurcevic, S.; Lange, S.; Uysal-Onganer, P. microRNA-21 Regulates Stemness in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, C.V.; Mohammed, A. New insights into pancreatic cancer stem cells. World J. Stem Cells 2015, 7, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubin, R.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I. Cancer Stem Cells in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gzil, A.; Zarębska, I.; Bursiewicz, W.; Antosik, P.; Grzanka, D.; Szylberg, Ł. Markers of pancreatic cancer stem cells and their clinical and therapeutic implications. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2019, 46, 6629–6645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, K.; Khan, F.B.; Akhtar, S.; Ahmad, A.; Uddin, S. The plasticity of pancreatic cancer stem cells: implications in therapeutic resistance. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 691–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Fatima, I.; Singh, A.B.; Dhawan, P. Pancreatic Cancer and Therapy: Role and Regulation of Cancer Stem Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan H., Xu, J.; et al. Pancreatic Cancer Stem Cells: New Insight into a Stubborn Disease. Cancer Lett 2015, 357, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fenu, G.; Griñán-Lisón, C.; Pisano, A.; González-Titos, A.; Farace, C.; Fiorito, G.; Etzi, F.; Perra, T.; Sabalic, A.; Toledo, B.; et al. Unveiling the microRNA landscape in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients and cancer cell models. BMC Cancer 2024, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etzi, F.; Griñán-Lisón, C.; Fenu, G.; González-Titos, A.; Pisano, A.; Farace, C.; Sabalic, A.; Picon-Ruiz, M.; Marchal, J.A.; Madeddu, R. The Role of miR-486-5p on CSCs Phenotypes in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2024, 16, 4237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pisano, A.; Griñan-Lison, C.; Farace, C.; Fiorito, G.; Fenu, G.; Jiménez, G.; Scognamillo, F.; Peña-Martin, J.; Naccarati, A.; Pröll, J.; et al. The Inhibitory Role of miR-486-5p on CSC Phenotype Has Diagnostic and Prognostic Potential in Colorectal Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez, G.; Hackenberg, M.; Catalina, P.; Boulaiz, H.; Griñán-Lisón, C.; García, M.Á.; Perán, M.; López-Ruiz, E.; Ramírez, A.; Morata-Tarifa, C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell’s secretome promotes selective enrichment of cancer stem-like cells with specific cytogenetic profile. Cancer Lett. 2018, 429, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farace, C.; Pisano, A.; Griñan-Lison, C.; Solinas, G.; Jiménez, G.; Serra, M.; Carrillo, E.; Scognamillo, F.; Attene, F.; Montella, A.; et al. Deregulation of cancer-stem-cell-associated miRNAs in tissues and sera of colorectal cancer patients. Oncotarget 2020, 11, 116–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yonemori, K.; Seki, N.; Idichi, T.; Kurahara, H.; Osako, Y.; Koshizuka, K.; Arai, T.; Okato, A.; Kita, Y.; Arigami, T.; et al. The microRNA expression signature of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by RNA sequencing: anti-tumour functions of the microRNA-216 cluster. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 70097–70115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix, T.F.; Lapa, R.M.L.; de Carvalho, M.; Bertoni, N.; Tokar, T.; Oliveira, R.A.; Rodrigues, M.A.M.; Hasimoto, C.N.; Oliveira, W.K.; Pelafsky, L.; et al. MicroRNA modulated networks of adaptive and innate immune response in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0217421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guz, M.; Jeleniewicz, W.; Cybulski, M.; Kozicka, J.; Kurzepa, J.; Mądro, A. Serum miR-210-3p can be used to differentiate between patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and chronic pancreatitis. Biomed. Rep. 2020, 14, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gao, S.; et al. Mir-216a-5p Inhibits Tumorigenesis in Pancreatic Cancer by Targeting Tpt1/Mtorc1 and Is Mediated by Linc01133. Int J Biol Sci 2020, 16, 2612–2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, E.; Rezaie, E.; Heiat, M.; Sefidi-Heris, Y. An Integrated Data Analysis of mRNA, miRNA and Signaling Pathways in Pancreatic Cancer. Biochem. Genet. 2021, 59, 1326–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erdos, Z.; E Barnum, J.; Wang, E.; DeMaula, C.; Dey, P.M.; Forest, T.; Bailey, W.J.; E Glaab, W. Evaluation of the Relative Performance of Pancreas-Specific MicroRNAs in Rat Plasma as Biomarkers of Pancreas Injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2020, 173, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurashige, S.; Matsutani, N.; Aoki, T.; Kodama, T.; Otagiri, Y.; Togashi, Y. Evaluation of circulating miR-216a and miR-217 as biomarkers of pancreatic damage in the L-arginine-induced acute pancreatitis mouse model. J. Toxicol. Sci. 2023, 48, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, G.; Smirne, C.; Mauri, F.A.; Tonel, E.; Carbone, A.; Buffolino, A.; Dughera, L.; Robecchi, A.; Pirisi, M.; Emanuelli, G. Cytokine expression profile in human pancreatic carcinoma cells and in surgical specimens: implications for survival. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2005, 55, 684–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitsunaga, S.; Ikeda, M.; Shimizu, S.; Ohno, I.; Furuse, J.; Inagaki, M.; Higashi, S.; Kato, H.; Terao, K.; Ochiai, A. Serum levels of IL-6 and IL-1β can predict the efficacy of gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2013, 108, 2063–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Chen, D.; Hu, W. Downregulation of miR-216a-5p by long noncoding RNA PVT1 suppresses colorectal cancer progression via modulation of YBX1 expression. Cancer Manag. Res. 2019, ume 11, 6981–6993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Tashiro, K.; Dixit, A.; Soni, A.; Vogel, K.; Hall, B.; Shafqat, I.; Slaughter, J.; Param, N.; Le, A.; et al. Loss of HIF1A From Pancreatic Cancer Cells Increases Expression of PPP1R1B and Degradation of p53 to Promote Invasion and Metastasis. Gastroenterology 2020, 159, 1882–1897.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, N.; Ergün, S.; Isenovic, E.R. Levels of MicroRNA Heterogeneity in Cancer Biology. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 2017, 21, 511–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Wu, J. Feud or Friend? The Role of the MiR-17-92 Cluster in Tumorigenesis; Curr Genomics 2010, 11, 129–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Vecchiarelli-Federico, L.M.; et al. The MiR-17-92 Cluster Expands Multipotent Hematopoietic Progenitors Whereas Imbalanced Expression of Its Individual Oncogenic MiRNAs Promotes Leukemia in Mice. Blood 2012, 119, 4486–4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zekri, A.-R.N.; El-Sisi, E.R.; Youssef, A.S.E.-D.; Kamel, M.M.; Nassar, A.; Ahmed, O.S.; El Kassas, M.; Barakat, A.B.; El-Motaleb, A.I.A.; Bahnassy, A.A. MicroRNA Signatures for circulating CD133-positive cells in hepatocellular carcinoma with HCV infection. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0193709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, S.; Lu, J.; Schlanger, R.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.Y.; Fox, M.C.; Purton, L.E.; Fleming, H.H.; Cobb, B.; Merkenschlager, M.; et al. MicroRNA miR-125a controls hematopoietic stem cell number. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2010, 107, 14229–14234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, H.I. MicroRNA Control of TGF-β Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, K.; Cao, Z.; et al. The Dual Functional Role of MicroRNA-18a (MiR-18a) in Cancer Development. Clin Transl Med 2019, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.M.; Zheng, X.M.; Liang, W.M.; Jiang, C.M.; Su, D.M.; Fu, B. Long Noncoding RNA MIR600HG Binds to MicroRNA-125a-5p to Prevent Pancreatic Cancer Progression Via Mitochondrial Tumor Suppressor 1–Dependent Suppression of Extracellular Regulated Protein Kinases Signaling Pathway. Pancreas 2022, 51, 1434–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Wei, J.; et al. The MiRNA125a-5p and MiRNA125b-1-5p Cluster Induces Cell Invasion by down-Regulating DDB2-Reduced Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in Colorectal Cancer. J Gastrointest Oncol 2022, 13, 3112–3122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G.; Liu, Y.; Shang, L.; Zhou, F.; Yang, S. EMT-associated microRNAs and their roles in cancer stemness and drug resistance. Cancer Commun. 2021, 41, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, Z.; Li, J. MicroRNA-125a-5p Regulates Liver Cancer Cell Growth, Migration and Invasion and EMT by Targeting HAX1. Int J Mol Med 2020, 46, 1849–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debnath, P.; Huirem, R.S.; Dutta, P.; Palchaudhuri, S. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition and its transcription factors. Biosci. Rep. 2021, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).