Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussions

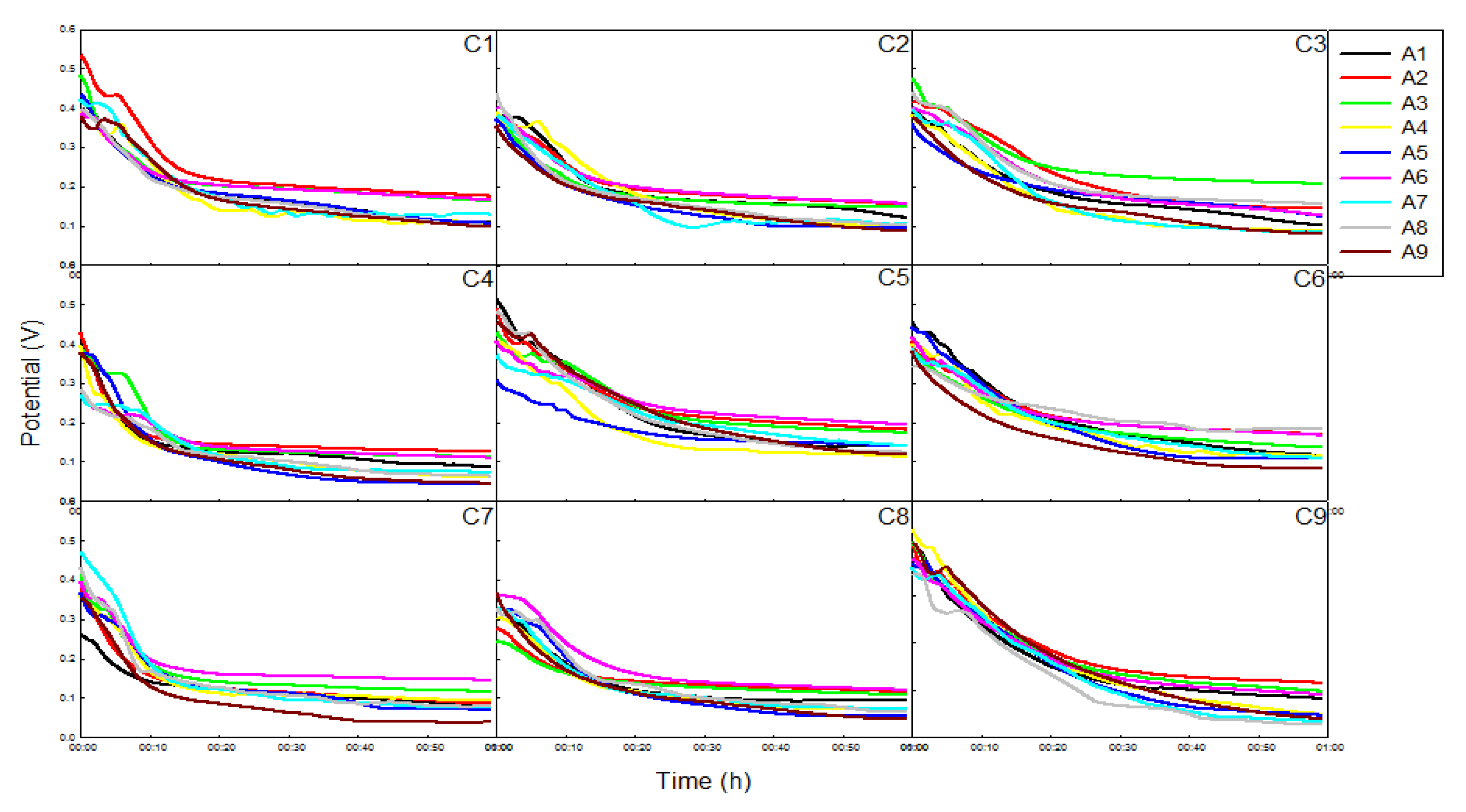

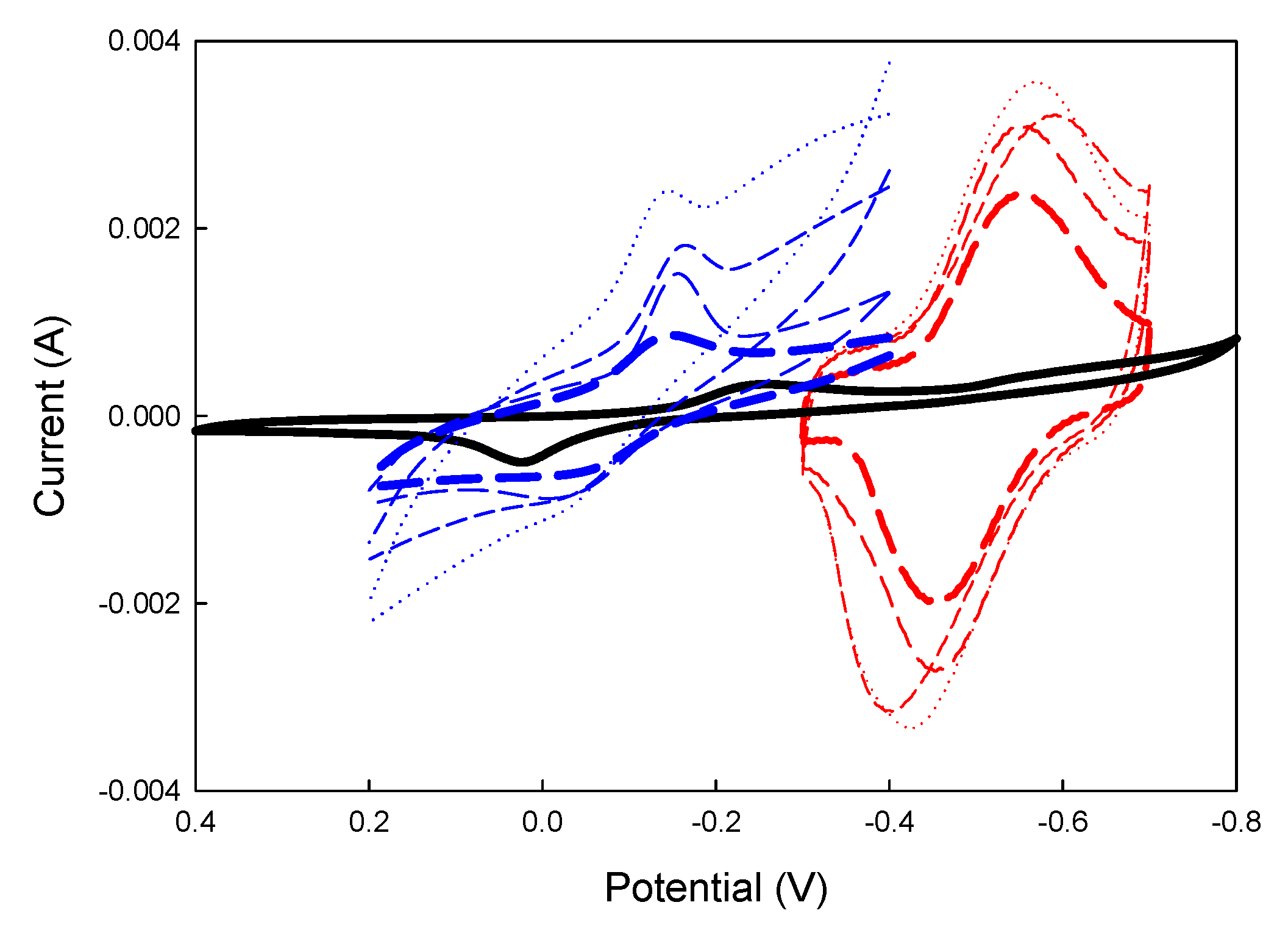

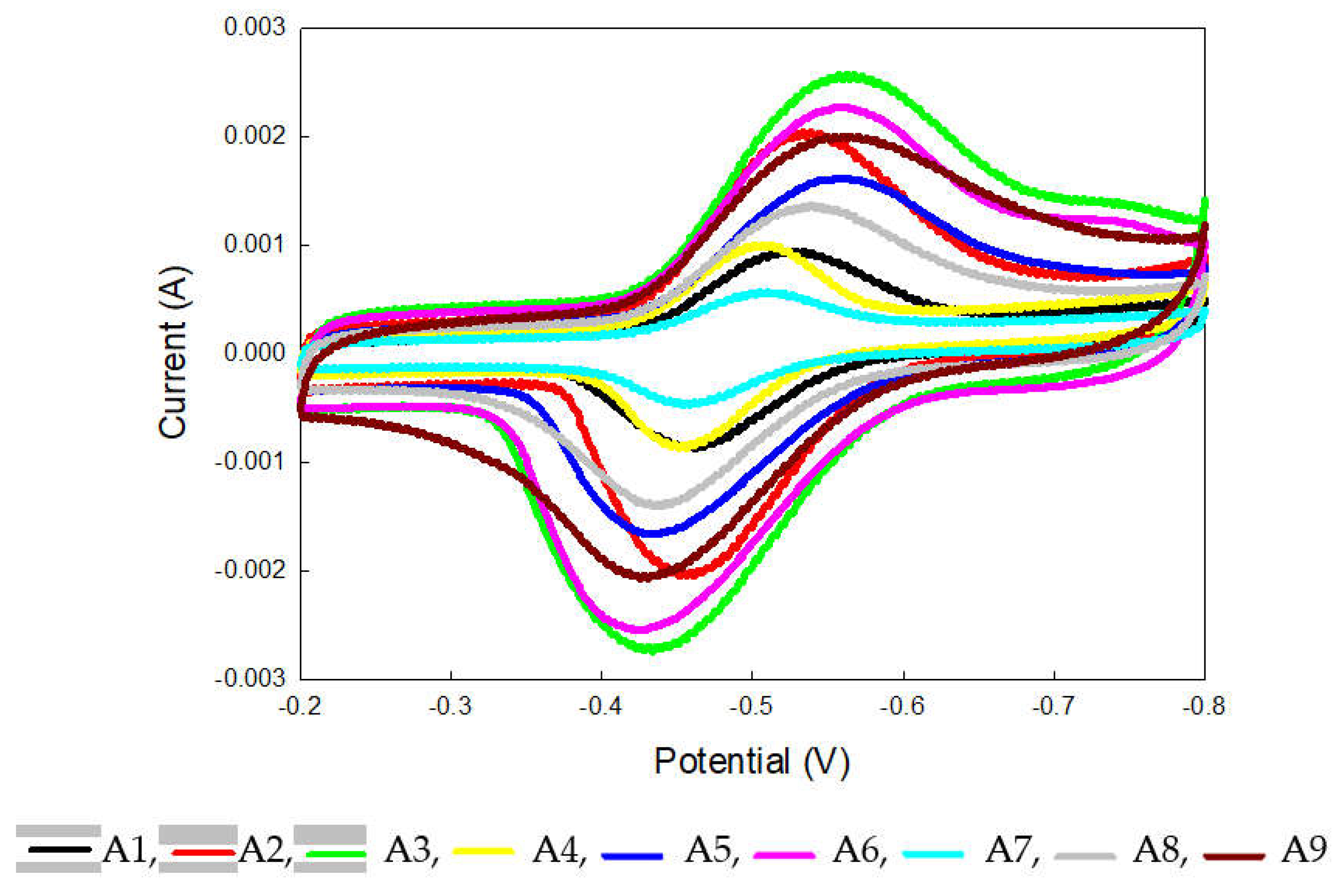

2.1. Cyclic Voltammetry Analysis of Electrode

| anode | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D0x1014 (cm²/s) | 7.48 | 36.9 | 56.1 | 7.96 | 20.9 | 42.8 | 2.01 | 14.5 | 29.7 |

| E0 | -0.491 | -0.498 | -0.498 | -0.479 | -0.499 | -0.492 | -0.485 | -0.487 | -0.498 |

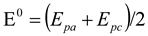

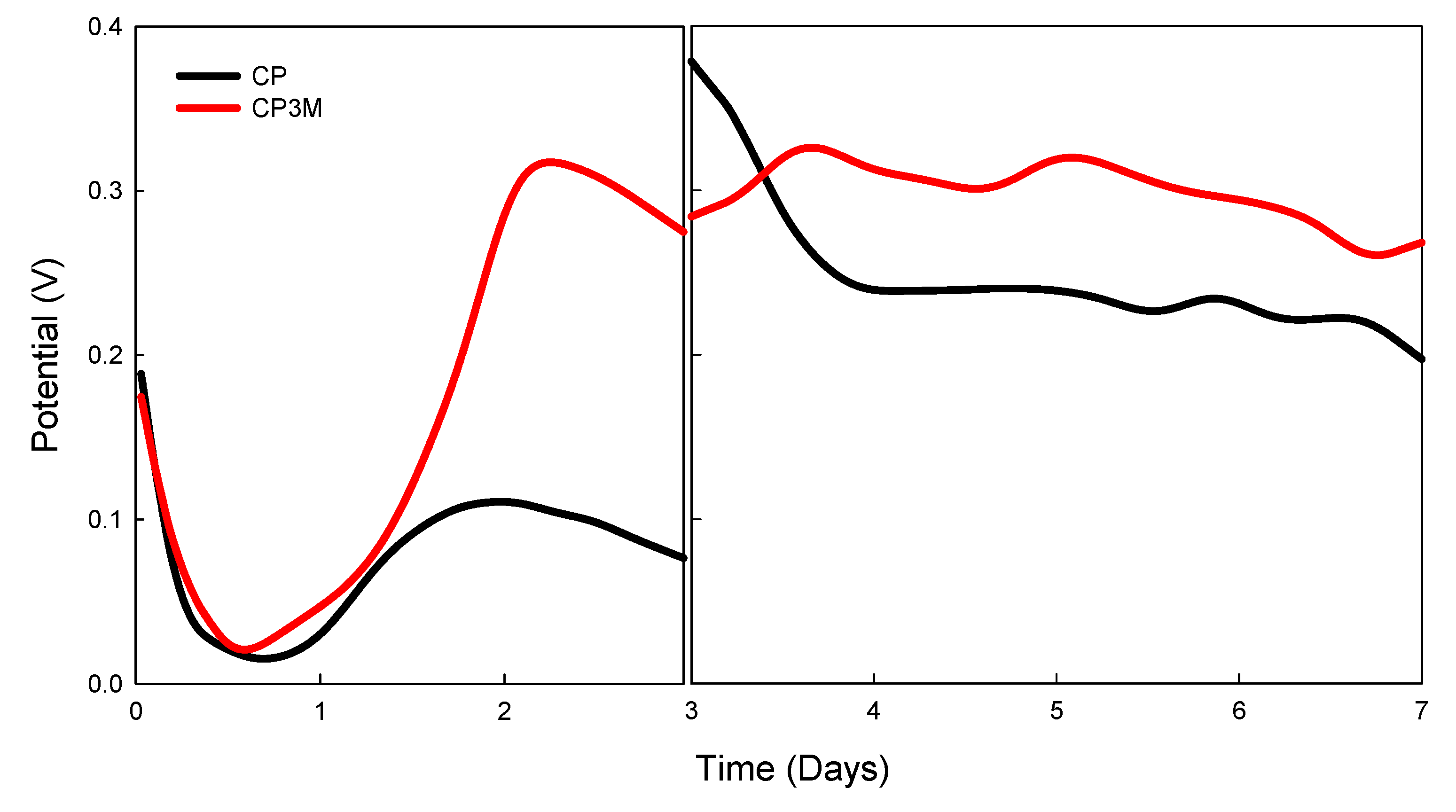

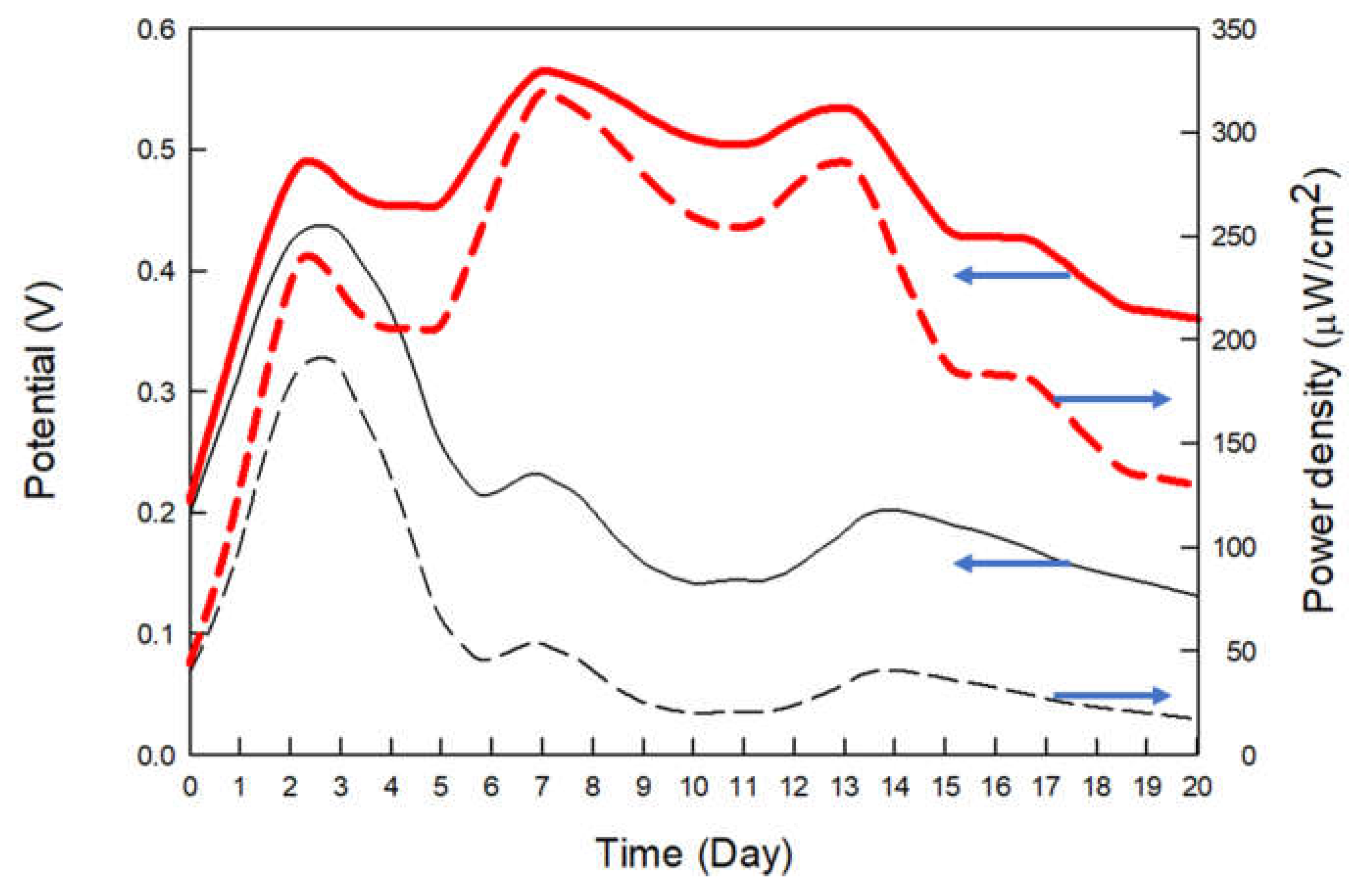

2.2. Enzyme Fuel Cell Performance Test Analysis

| cell | A1C1 | A1C2 | A1C3 | A1C4 | A1C5 | A1C6 | A1C7 | A1C8 | A1C9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.422 | 0.377 | 0.390 | 0.409 | 0.513 | 0.458 | 0.262 | 0.329 | 0.500 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 178.1 | 141.8 | 152.3 | 167.3 | 263.3 | 209.4 | 68.7 | 107.9 | 249.7 |

| cell | A2C1 | A2C2 | A2C3 | A2C4 | A2C5 | A2C6 | A2C7 | A2C8 | A2C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.534 | 0.355 | 0.414 | 0.428 | 0.491 | 0.406 | 0.380 | 0.277 | 0.515 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 285.5 | 125.9 | 171.3 | 183.3 | 241.5 | 164.8 | 144.1 | 76.6 | 264.8 |

| cell | A3C1 | A3C2 | A3C3 | A3C4 | A3C5 | A3C6 | A3C7 | A3C8 | A3C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.482 | 0.374 | 0.476 | 0.387 | 0.429 | 0.377 | 0.415 | 0.244 | 0.513 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 232.4 | 139.6 | 226.3 | 149.7 | 184.4 | 142.3 | 172.5 | 59.6 | 263.2 |

| cell | A4C1 | A4C2 | A4C3 | A4C4 | A4C5 | A4C6 | A4C7 | A4C8 | A4C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.394 | 0.390 | 0.381 | 0.397 | 0.407 | 0.399 | 0.359 | 0.303 | 0.542 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 155.2 | 151.9 | 145.2 | 157.4 | 166.0 | 159.1 | 129.0 | 91.8 | 293.5 |

| cell | A5C1 | A5C2 | A5C3 | A5C4 | A5C5 | A5C6 | A5C7 | A5C8 | A5C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.433 | 0.370 | 0.361 | 0.376 | 0.308 | 0.442 | 0.366 | 0.324 | 0.469 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 187.1 | 137.1 | 130.3 | 141.6 | 94.7 | 195.3 | 133.7 | 105.2 | 220.2 |

| cell | A6C1 | A6C2 | A6C3 | A6C4 | A6C5 | A6C6 | A6C7 | A6C8 | A6C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.388 | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.270 | 0.406 | 0.417 | 0.396 | 0.362 | 0.479 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 150.3 | 160.3 | 159.6 | 73.1 | 165.0 | 173.7 | 156.7 | 131.2 | 229.2 |

| cell | A7C1 | A7C2 | A7C3 | A7C4 | A7C5 | A7C6 | A7C7 | A7C8 | A7C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.421 | 0.379 | 0.398 | 0.271 | 0.373 | 0.391 | 0.472 | 0.329 | 0.459 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 177.5 | 144.0 | 158.4 | 73.7 | 139.4 | 153.1 | 222.4 | 108.5 | 211.0 |

| cell | A8C1 | A8C2 | A8C3 | A8C4 | A8C5 | A8C6 | A8C7 | A8C8 | A8C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.397 | 0.437 | 0.441 | 0.287 | 0.482 | 0.344 | 0.432 | 0.328 | 0.446 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 157.9 | 191.3 | 194.5 | 82.4 | 232.8 | 118.4 | 186.8 | 107.6 | 199.3 |

| cell | A9C1 | A9C2 | A9C3 | A9C4 | A9C5 | A9C6 | A9C7 | A9C8 | A9C9 |

| Initial voltage(V) | 0.380 | 0.353 | 0.377 | 0.378 | 0.455 | 0.382 | 0.354 | 0.369 | 0.512 |

| Power density(μW/cm2) | 144.2 | 124.3 | 142.3 | 142.6 | 206.6 | 145.6 | 125.2 | 136.0 | 261.7 |

| cell | A1C1 | A1C2 | A1C3 | A1C4 | A1C5 | A1C6 | A1C7 | A1C8 | A1C9 |

| power (J) | 655 | 700 | 672 | 498 | 801 | 756 | 438 | 486 | 919 |

| cell | A2C1 | A2C2 | A2C3 | A2C4 | A2C5 | A2C6 | A2C7 | A2C8 | A2C9 |

| power(J) | 877 | 738 | 819 | 574 | 902 | 808 | 484 | 529 | 1020 |

| cell | A3C1 | A3C2 | A3C3 | A3C4 | A3C5 | A3C6 | A3C7 | A3C8 | A3C9 |

| power(J) | 774 | 673 | 941 | 577 | 876 | 719 | 576 | 501 | 981 |

| cell | A4C1 | A4C2 | A4C3 | A4C4 | A4C5 | A4C6 | A4C7 | A4C8 | A4C9 |

| power(J) | 611 | 647 | 574 | 423 | 650 | 673 | 496 | 432 | 922 |

| cell | A5C1 | A5C2 | A5C3 | A5C4 | A5C5 | A5C6 | A5C7 | A5C8 | A5C9 |

| power(J) | 655 | 546 | 684 | 388 | 646 | 684 | 480 | 430 | 868 |

| cell | A6C1 | A6C2 | A6C3 | A6C4 | A6C5 | A6C6 | A6C7 | A6C8 | A6C9 |

| power(J) | 764 | 748 | 754 | 530 | 907 | 800 | 654 | 635 | 948 |

| cell | A7C1 | A7C2 | A7C3 | A7C4 | A7C5 | A7C6 | A7C7 | A7C8 | A7C9 |

| power(J) | 671 | 582 | 602 | 442 | 782 | 697 | 515 | 456 | 844 |

| cell | A8C1 | A8C2 | A8C3 | A8C4 | A8C5 | A8C6 | A8C7 | A8C8 | A8C9 |

| power(J) | 631 | 611 | 803 | 424 | 784 | 809 | 493 | 490 | 777 |

| cell | A9C1 | A9C2 | A9C3 | A9C4 | A9C5 | A9C6 | A9C7 | A9C8 | A9C9 |

| power(J) | 640 | 561 | 568 | 391 | 813 | 548 | 336 | 415 | 920 |

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Chemicals

3.2. Electrolyte Solution

3.3. Preparation of Enzyme Solution and Immobilization Technique

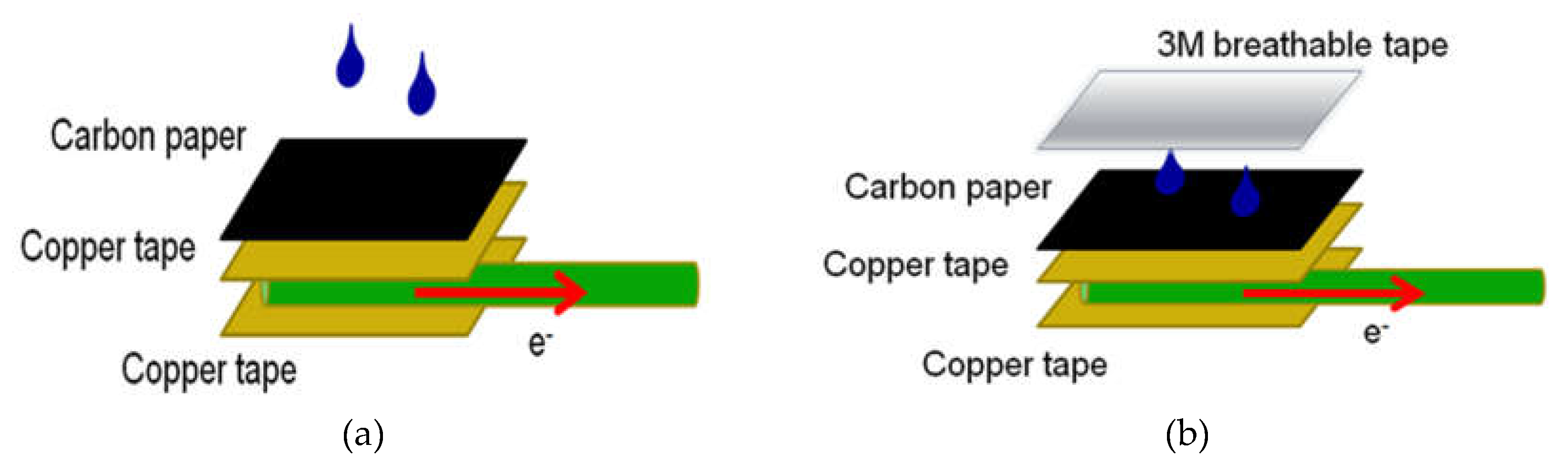

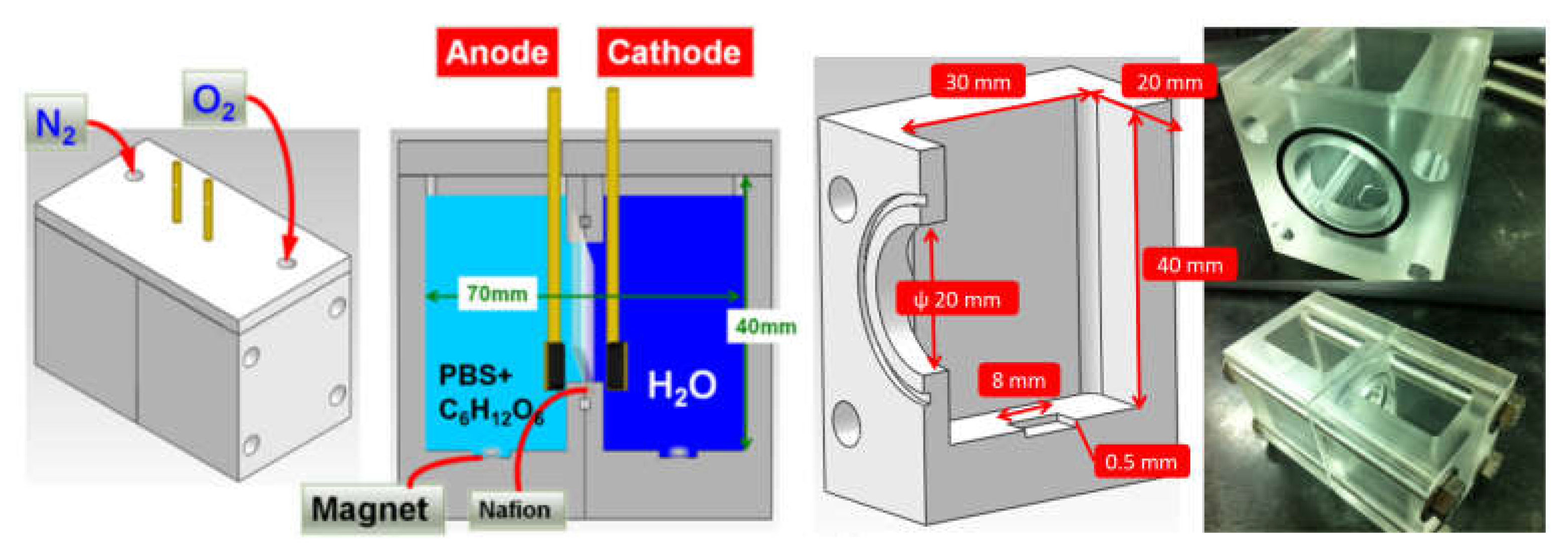

3.4. Performance Test of the Enzyme-Based Biofuel Cell

3.5. Cyclic Voltammetry

4. Conclusions

Notations

| ABTS | |

| CP | copper-type |

| CP3M | copper-type with 3M micropore type |

| CV | cyclic voltammetry |

| EIS | electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| Gox | glucosidase |

| Lac | laccase |

| PANI | polyaniline |

| PBS | phosphate buffer solution |

| PPy | polypyrrole |

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zebda, A.; Innocent, C.; Renaud, L.; Certin, M.; Pichot, F.; Ferrigno, R.; Tingry, S. Enzyme-Based Microfluidic Biofuel Cell to Generate Micropower in Biofuel's Engineering Process Technology; 2011; p. 564.

- Kim, J.; Jia, H.; Wang, P. Challenges in biocatalysis for enzyme-based biofuel cells. Biotechnology Advances 2006, 24, 296–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Żygowska, M. Design, fabrication and characterisation of components for microfluidic enzymatic biofuel cells, Thesis, National University of Ireland, Cork. National University of Ireland, Cork 2014.

- Wong, Y.; Yu, J. Laccase-catalyzed Decolorization of Synthetic Dye. Water research 1999, 33, 3512–3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- XU, Q.y.; LIU, C.b.; Wu, H.s. Low-cost Immobilized Enzyme Glucose Sensor based on Laminar Flow. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, The 6th International Conference on Chemical Materials and Process 2020, 1681, 012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C.M.; Wong, K.H.; Chen, X.D. Glucose oxidase: natural occurrence, function, properties and industrial applications. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2008, 78, 927–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, K.E.; Eggert, T. Enantioselective biocatalysis optimized by directed evolution. Current opinion in biotechnology 2004, 15, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ummalyma, S.B.; Bhaskar, T. Recent advances in the role of biocatalyst in biofuel cells and its application: An overview. Biotechnology and Genetic Engineering Reviews 2024, 40, 2051–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, L.; Chen, J.; Pang, J.; Qu, H.; Liu, J.; Gao, J. Research Progress in Enzyme Biofuel Cells Modified Using Nanomaterials and Their Implementation as Self-Powered Sensors. Molecules 2024, 29, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanford, C.F.; Heath, R.S.; Armstrong, F.A. A stable electrode for high-potential, electrocatalytic O(2) reduction based on rational attachment of a blue copper oxidase to a graphite surface. Chem Commun (Camb) 2007, 1710–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, C.M.; Akers, N.L.; Hill, A.D.; Johnson, Z.C.; Minteer, S.D. Improving the Environment for Immobilized Dehydrogenase Enzymes by Modifying Nafion with Tetraalkylammonium Bromides. Biomacromolecules 2004, 5, 1241–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heineman, W.R.; Kissinge, P.T. Analytical Electrochemistry: Methodology and Applications of Dynamic Techniques. Anal. Chem. 1980, 52, 138R–151R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismagilov, R.F.; Stroock, A.D.; Kenis, P.J.A.; Whitesides, G.; Stone, H.A. Experimental and theoretical scaling laws for transverse diffusive broadening in two-phase laminar flows in microchannels. Applied Physics Letters 2000, 76, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.J.; Chan, D.S.; Wu, H.S. Modified Carbon Nanoball on Electrode Surface Using Plasma in Enzyme-Based Biofuel Cells. Energy Procedia 2012, 14, 1804–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, G.J.; Calverley, D.C. Aspirin, Platelets, and Thrombosis: Theory and Practice. Blood 1994, 83, 885–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munauwarah, R.; Bojang, A.A.; Wu, H.S. Characterization of enzyme immobilized carbon electrode using covalent-entrapment with polypyrrole. Journal of the Chinese Institute of Engineers 2018, 41, 710–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bojang, A.A.; Wu, H.S. Characterization of electrode performance in enzymatic biofuel cells using cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance Spectroscopy. Catalysts 2020, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J.R.; Engstrom, A.M.; Friesen, C. Orthogonal flow membraneless fuel cell. Journal of Power Sources 2008, 183, 257–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, D.; Venkateswaran, P.S.; Dwivedi, P.K.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, G.M.; Sharma, A.; Goel, S. Recent developments in enzymatic biofuel cell: towards implantable integrated micro-devices. Int. J. Nanoparticles 2015, 8, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.N.; Holzinger, M.; Mousty, C.; Cosnier, S. Laccase electrodes based on the combination of single-walled carbon nanotubes and redox layered double hydroxides: Towards the development of biocathode for biofuel cells. Journal of Power Sources 2010, 195, 4714–4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klis, M.; Maicka, E.; Michota, A.; Bukowska, J.; Sek, S.; Rogalski, J.; Bilewicz, R. Electroreduction of laccase covalently bound to organothiol monolayers on gold electrodes. Electrochimica Acta 2007, 52, 5591–5598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Kim, G.-Y.; Moon, S.-H. Covalent co-immobilization of glucose oxidase and ferrocenedicarboxylic acid for an enzymatic biofuel cell. Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry 2011, 653, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese Barton, S.; Gallaway, J.; Atanassov, P. Enzymatic Biofuel Cells for Implantable and Microscale Devices. Chemical Reviews 2004, 104, 4867–4886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebda, A.; Renaud, L.; Cretin, M.; Pichot, F.; Innocent, C.; Ferrigno, R.; Tingry, S. A microfluidic glucose biofuel cell to generate micropower from enzymes at ambient temperature. Electrochemistry Communications 2009, 11, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willner, I.; Yan, Y.M.; Willner, B.; Tel-Vered, R. Integrated Enzyme-Based Biofuel Cells-A Review. Fuel Cells 2009, 9, 7–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

: pH5

: pH5 : pH 6

: pH 6 : pH 7), immersed at 0 h in a glucose buffer solution; (

: pH 7), immersed at 0 h in a glucose buffer solution; ( : pH 5

: pH 5 : pH 6

: pH 6 : pH 7), immersed at 1 h in a glucose buffer solution.

: pH 7), immersed at 1 h in a glucose buffer solution.

: pH5

: pH5 : pH 6

: pH 6 : pH 7), immersed at 0 h in a glucose buffer solution; (

: pH 7), immersed at 0 h in a glucose buffer solution; ( : pH 5

: pH 5 : pH 6

: pH 6 : pH 7), immersed at 1 h in a glucose buffer solution.

: pH 7), immersed at 1 h in a glucose buffer solution.

:10,

:10, :20,

:20,  : 30,

: 30,  :40), PANI (mM)= (

:40), PANI (mM)= ( :10,

:10, ,20,

,20,  : 30

: 30 :40), blank (mM)=: 0, GOx (5U/10μL), Fe(CN)63-(10mM), pH=7.

:40), blank (mM)=: 0, GOx (5U/10μL), Fe(CN)63-(10mM), pH=7.

:10,

:10, :20,

:20,  : 30,

: 30,  :40), PANI (mM)= (

:40), PANI (mM)= ( :10,

:10, ,20,

,20,  : 30

: 30 :40), blank (mM)=: 0, GOx (5U/10μL), Fe(CN)63-(10mM), pH=7.

:40), blank (mM)=: 0, GOx (5U/10μL), Fe(CN)63-(10mM), pH=7.

| Current | PPy5b | PPy6 | PPy7 | PANI5 | PANI6 | PANI7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ipa(A) | 2.42×10-3 | 2.49×10-3 | 2.36×10-3 | 2.34×10-3 | 2.51×10-3 | 1.94×10-3 |

| ipc(A) | -2.23×10-3 | -2.34×10-3 | -2×10-3 | -1.45×10-3 | -1.72×10-3 | -1.01×10-3 |

| △ia | 7.8% | 6% | 15.2% | 38% | 31.4% | 47.9% |

| electrode | Response time | Voltage (V) | Power density (μW/cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP | excellent | 0.24 | 57.6 |

| CP3M | good | 0.57 | 324.9 |

| System (oxidation/ reduction) |

Enzyme (anode/ cathode) |

Concentration (mM) (anode/ cathode) |

Electrode | Electrolyte | Potential (V) |

Power (W/cm2) |

Time(hr) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 10/10 | Graphite disc electrodes with Os-complex | PBS, pH 4.4~7.4 |

0.3 pH4.4 0.4pH5.5 0.25pH7.4 |

10,40 and 16 (37℃) |

- - - | [19] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 5/1 | Graphite electrode modified with CNT | PBS, pH 5.86 |

0.2 | 4.1 (20℃) |

- - - | [2] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 10/10 | Carbon electrode modified with polypyrrole | PBS, pH 7.4 |

0.41 | 27 (37℃) |

144 | [20] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 10/10 | Carbon fiber Electrodes with SWNT | PBS, pH 7.4 |

0.4 | 58 (25℃) |

50 | [21] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 60/3 | Carbon fiber electrodes with CNT | PBS, pH 7.0 CBS,pH 5.0 |

0.65 | 45 (37℃) |

1 | [22] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 3/3 | Au electrode 0.0314 cm2 | PBS, pH 7.0 Membrane -less | 0.46 | 0.442 (25℃) |

100 | [23] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 10/5 | Gold electrode (10 mm length and 2 mm wide) | PBS, pH 7.0 CBS,pH 3.0 |

0.3 | 110 (23℃) |

- - - | [24] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 5/5 | Au electrode | PBS, pH 6.0 | 0.226 | 178 (25℃) |

- - - | [25] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 40/40 | Carbon paper | PBS, pH 7.0 CBS,pH 5.0 |

0.35 | 122.6 (37℃) |

100 | [6] |

| Glucose/O2 | GOx/LAc | 40/40 | Carbon paper covered with tape | PBS,pH 5.0 CBS,pH 5.0 |

0.57 | 324.9 (37℃) |

480 | This study |

| No | GOx (U/10μL) | PPy (mM) | Fe(CN)63-(mM) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| A2 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 6 |

| A3 | 5 | 15 | 30 | 7 |

| A4 | 10 | 5 | 20 | 7 |

| A5 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 5 |

| A6 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 6 |

| A7 | 15 | 5 | 30 | 6 |

| A8 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 7 |

| A9 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 5 |

| No | Laccase (U/10μL) | PPy (mM) | ABTS(mM) | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 5 | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| C2 | 5 | 10 | 20 | 6 |

| C3 | 5 | 15 | 30 | 7 |

| C4 | 10 | 5 | 20 | 7 |

| C5 | 10 | 10 | 30 | 5 |

| C6 | 10 | 15 | 10 | 6 |

| C7 | 15 | 5 | 30 | 6 |

| C8 | 15 | 10 | 10 | 7 |

| C9 | 15 | 15 | 20 | 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).