1. Introduction

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a heterogeneous, preventable condition marked by persistent respiratory symptoms and systemic effects [

1]. Primary symptoms include breathlessness, coughing, and sputum production [

2]. Individuals with COPD frequently experience comorbid sonditions with cognitive impairment being a common but under-researched issue [

3]. Studies show that cognitive impairment prevalence in individuals with COPD ranges from 10% to 77% [

4,

5]. Increasing physical activity may positively impact cognitive functions in these individuals [

6].

According to the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society, comprehensive rehabilitation programs including aerobic and muscle strengthening exercises (SE), along with patient education, are recommended for COPD management [

7]. However, alternative approaches such as Square-Stepping Exercise (SSE) are gaining interest due to their systematic and cost-effective nature. SSE, though rarely used in respiratory diseases, has shown promise in addressing balance, muscle weakness, and cognitive impairments, particularrly in older adults [

8].

Studies suggest that SSE improves dynamic balance while engaging cognitive functions. Its low technological requirements make it suitable for rehabilitation, offering benefits for individuals with COPD by addressing balance and cognition together [

9,

10]. SSE is a multitasking program combining cognitive functions such as concentration, memory, and motor skills with physical effort. Regular practice has been shown to improve both balance and cognitive functions [

11].

SE are well-known for enhancing muscle strength and postural stability, though their impact on cognitive functions in individuals with COPD remains underexplored. Vilaró et al. highlighted that muscle dysfunction, particularly peripheral muscle weakness, is a key risk factor for hospital readmission in COPD, underscoring the importance of SE to improve muscle function and stability [

12]. SE that focus on peripheral muscles have been shown to improve not only muscle strength but also postural stability. For instance, scapulothoracic exercises have shown benefits on chest mobility and respiratory muscle strength in COPD, indicaitng potential impacts on functional capacity [

13]. Interest in the impact of peripheral muscle SE on cognitive functions in COPD is growing but remains under-researched. This relationship is crucial, as cognitive impairment in COPD can reduce physical activity levels, leading to a detrimental cycle [

14]. Gore et al. identified a link between cognitive function, balance, and gait speed in older adults with COPD, suggesting that enhancing physical strength and stability could improve cognitive outcomes [

15]. This highlights the potential of SE as a dual-purpose intervention for physical and cognitive health in this population.

This study uniquely explores the effects of SSE, a less commonly used method in respiratory rehabilitation, on cognitive function and balance in individuals with COPD, compared to strengthening exercises. While strengthening and aerobic exercises are widely utilized in managing chronic respiratory diseases like COPD, research on the impact of SSE in this population remains limited.

This study aims to examine the comparative effects of SSE and SE on improving cognitive functions and balance in individuals with COPD. There is a notable gap in research on multitasking exercise programs addressing balance loss and cognitive impairment in individuals with respiratory diseases. This study examines whether an alternative exercise method targeting both physical and cognitive functions in individuals with COPD offers greater benefits than traditional SE when delivered via telerehabilitation.

2. Materials and Methods

The Study Design

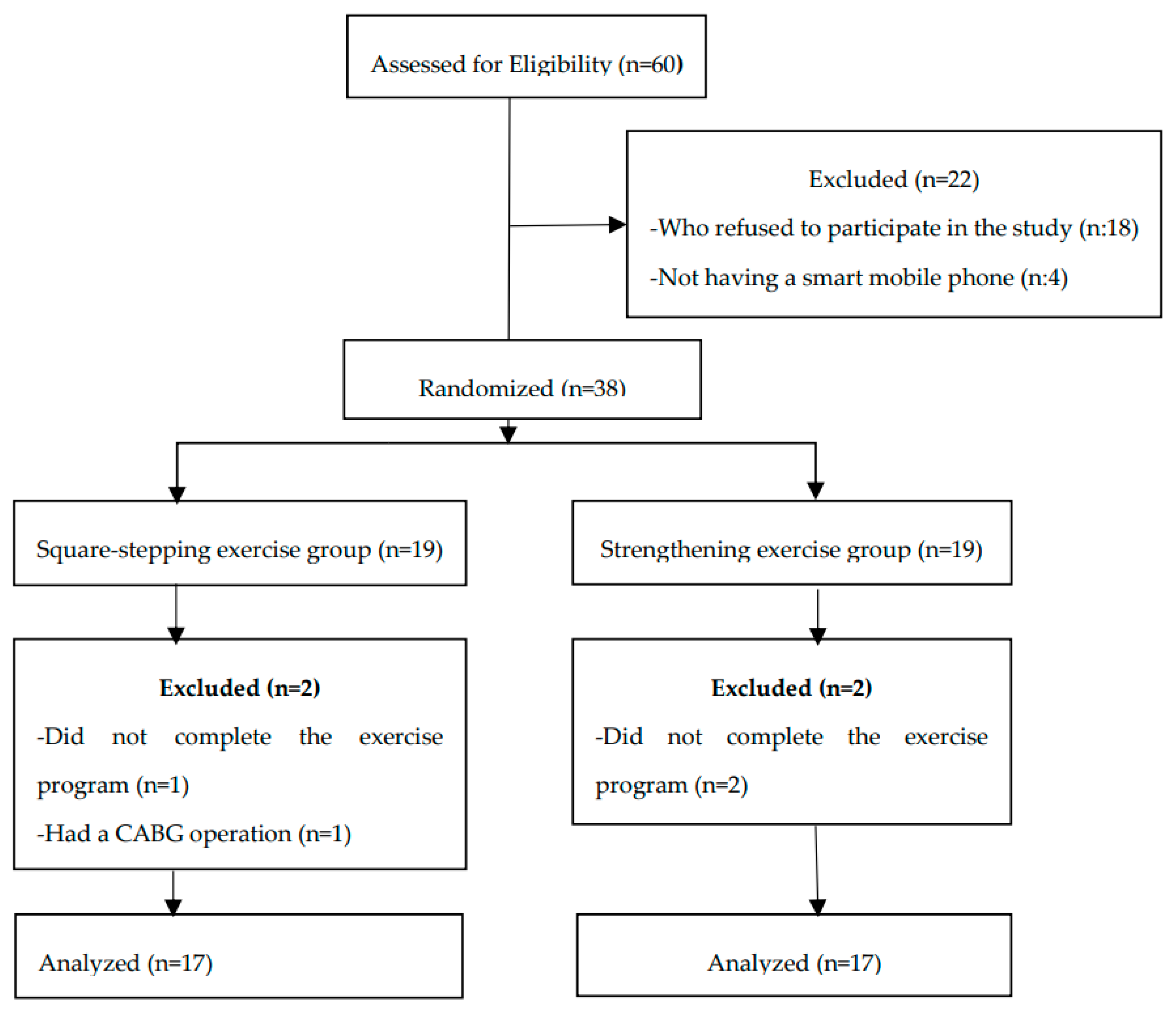

This study was designed as a prospective, randomized, comparative clinical trial. A total of 38 individuals were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio into two groups using simple randomization via MedCalc 11.5.1 software: the SSE group (n=19) and the SE group (n=19) [

10]. The study was conducted using a single-blind method, where the participants were unaware of which group they were assigned to.

Participants

Male participants diagnosed with mild to moderate COPD at Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal University Training and Research Hospital were enrolled in the study, which was conducted between April 6, 2021, and February 15, 2022. The inclusion criteria included: a confirmed COPD diagnosis, a Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination (SMMSE) score of 23 or higher, age 50-80, access to a smartphone and the internet, and willingness to adhere to the rehabilitation program. Exclusion criteria included: continuous oxygen support, COPD exacerbation phase, PaCO

2≥70 mmHg, conditions affecting cognitive function, sensory impairments, severe chronic diseases, inability to walk, failure to follow the exercise program, and illiteracy. Written and informed consent was obtained for all participants. None of the participants were involved in other experimental trials during the entire duration of the present study. The inclusion process of participants is illustrated in the flowchart shown in

Figure 1.

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal University Clinical Researches Ethics Committee (Decision No:2020/14; Date: 04.02.2020) in line with the Declaration of Helsinki and registered with Clinical Trials (NCT04841005). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to their involvement in the study, and the CONSORT guidelines were adhered to [

16,

17].

Exercise Protocols

Both groups received face-to-face training before proceeding with telerehabilitation through WhatsApp®. Equipment such as a tripod, pulse oximeter, Borg scale for fatigue, a SSE mat, and elastic bands were provided. Exercises included breathing exercises, warm-ups, and cool-downs.

Square-Stepping Exercise Protocol

SSE was performed on a mat measuring 100x250 cm, divided into 40 squares, each measuring 25 cm on each side [

11]. The exercise involved forward, backward, sideways, and diagonal steps, with step patterns becoming progressively more complex. There are 196 step patterns, divided into 8 categories (Easy 1-2; Intermediate 3-5; Advanced 6-8). Each pattern consists of 2 to 16 steps depending on its difficulty level [

11]. Participants were asked to step into the squares, repeating the step pattern from one end of the mat to the other. Upon reaching the end, they were instructed to return to the starting position at a normal walking pace and begin the next set. Each pattern was repeated 4 to 10 times. Although a specific stepping cadence was not set, participants were expected to complete each step pattern within 15-20 seconds. If participants could complete the pattern within the specified time, the difficulty level increased progressively: easy patterns during the first two weeks, intermediate patterns in the 3rd and 4th weeks, intermediate to advanced patterns in the 5th and 6th weeks, and advanced patterns in the final two weeks. If participants failed to complete a pattern in the allotted time, the difficulty level was not increased. The SSE group performed 10 minutes of warm-up exercises, 30 minutes of SSE, and 10 minutes of cool-down exercises, 3 days per week for 8 weeks.

Strengthening Exercise Protocol

Exercise intensity was determined according to the recommendations of the American College of Sports Medicine [

24]. Using an elastic band, participants’ perceived exertion during 15 repetitions was evaluated using the Borg scale to determine the appropriate exercise intensity. A perceived exertion score of 12-14 (“somewhat hard”) was considered the starting intensity [

24].

The SE group performed various exercises to improve muscle strength. These included shoulder abduction, elbow flexion, and shoulder press movements. Participants also performed horizontal abduction and punching exercises using an elastic band, as well as triceps strengthening. Additional exercises included shoulder external rotation, hip abduction with external rotation, and a standing exercise from a seated position. Strength training was performed for 8-12 repetitions, 3 sets per session, 3 days per week for 8 weeks. A 2-3 minute rest period was given between sets. Strength training began with 8 repetitions at the starting intensity. As participants were able to perform 12 repetitions easily, the number of repetitions was gradually increased. When participants could perform more than 15 repetitions easily for two consecutive sessions without severe muscle or joint pain, the elastic band color was changed to increase resistance. Participants then performed 8 repetitions with the new resistance level.

Sample Size

The primary outcome measure to was cognitive function, assessed using the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Power analysis was conducted using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7) to determine the required sample size for the study. Sander et al. reported an effect size of

d=1.02 for older adults engaging in multi-component exercises, supporting the feasibility of this sample size [

25]. Based on a significance level (α=0.05) and a power of 80% (1−β=0.80), the power analysis determined that a minimum of 13 participants per group was required. To account for potential dropouts, 19 participants were initially recruited for each group, and the study was successfully completed with 17 participants in each group.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York). The Shapiro-Wilk test assessed data normality. Descriptive statistics, including median values, interquartile ranges, numbers, and percentages, were calculated based on variable types. Parametric tests were used for normally distributed data, while non-parametric tests were applied for non-normally distributed data. For group comparisons, the independent sample t-test was used for parametric data, and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-parametric data. Differences between measurements were analyzed using a paired sample t-test for parametric data and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test for non-parametric data. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Data Availability

The data associated with this study are not publicly available but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

3. Results

A total of 60 candidates were evaluated, with 38 meeting the inclusion criteria and completing the study. The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age (p=0.324), body mass index (BMI) (p=0.717), mMRC (p=0.078), CAT (p=0.375), SMMSE (p=0.274), modified CCI (p=0.182), FEV

1 (p=0.485), and FEV

1/FVC (p=0.274).

Table 2 presents the comparison of MoCA scores between the SSE and SE groups at baseline, post-intervention, and between groups. While no significant difference was found between the groups after the intervention (p=0.927), both the SSE (p=0.001) and SE (p=0.001) groups demonstrated significant improvements in MoCA scores after 8 weeks.

Table 3 compares balance variables, assessed with the Biodex Balance System, between the SSE and SE groups at baseline, post-intervention, and between groups. Post-intervention, no significant differences were observed between the groups for the medial/lateral stability index (p=0.085), eyes open on a firm surface (p=0.192), eyes closed on a firm surface (p=0.732), eyes open on a foam surface (p=0.193), or eyes closed on a foam surface (p=0.058).

However, significant differences were observed in the overall stability index (p=0.014) and anterior/posterior stability index (p=0.05) between the SSE and SE groups after the intervention. The SSE group showed significant improvements in the overall stability index (p=0.001), anterior/posterior stability index (p=0.001), medial/lateral stability index (p=0.001), eyes closed on a firm surface (p=0.001), eyes open on a foam surface (p=0.001), and eyes closed on a foam surface (p=0.004). In contrast, the SE group showed significant improvement only in the eyes open on a firm surface condition (p=0.029) after the intervention

4. Discussion

This randomized study examined the effects of SSE and SE on cognitive functions and balance in individuals with COPD over 8 weeks. While no significant differences were found between the groups regarding cognitive function improvements, both groups showed significant progress post-intervention. These results align with existing literature highlighting the positive effects of physical activity on cognitive functions in individuals with COPD [

25]. Cognitive impairment is common in individuals with COPD, yet studies on its management and improvement are limited. While the positive effects of physical exercise on cognitive functions have been well-documented in older adults, our study shows that similar improvements can also be achieved in individuals with chronic conditions like COPD [

26].

Exercises combining physical and cognitive tasks have been shown to be more effective for enhancing cognitive skills in older adults compared to single-task exercises [

27]. The cognitive improvements observed in the SSE group suggest that multitasking exercises may offer greater benefits in this area. As SSE integrates both physical effort and cognitive challenges, it likely creates a synergistic effect, enhancing both mental and physical functions simultaneously.

Studies have highlighted the positive effects of multitasking exercises on cognitive functions [

28,

29]. Teixeira et al. reported significant cognitive improvements in older adults following SSE [

29]. Another study during the COVID-19 pandemic examined the short-term effects of home-based online SSE on cognitive and social functions in inactive older adults [

30]. This study found that online SSE enhanced executive control functions and group cohesion. Unlike in-person group exercises, the online SSE program also fostered improved social and task-oriented interactions among participants. In comparison to the previous study, our study observed cognitive function improvements in both groups of individuals with COPD, with significant balance improvements noted particularly in the SSE group. Both studies highlight the potential of multitasking exercises to enhance cognitive abilities, such as executive functions. Additionally, these exercises, which can be effectively implemented online, are crucial for maintaining physical activity, especially during periods of social isolation, such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

31]. These results parallel the findings of our study and suggest that multitasking exercises can be especially beneficial for older adults and individuals with chronic diseases.

The SSE group demonstrated significant improvements in the overall stability index and anterior/posterior stability index compared to the SE group. Balance is a critical determinant of fall risk, especially in individuals with COPD [

31]. Research shows that balance impairments are prevalent in this population, with significant deficits in balance control compared to healthy individuals. A systematic review reported that individuals with COPD are four times more likely to experience falls than their healthy peers, emphasizing the need for thorough balance assessment and targeted interventions in this group [

32]. The Berg Balance Scale and Timed Up and Go tests are commonly utilized to evaluate balance in individuals with COPD, although they may have limitations in fully capturing the extent of balance deficits [

33].

Muscle weakness is a well-established risk factor for falls and balance impairments in individuals with COPD. Beauchamp et al. highlighted the essential role of muscle strength in balance control, noting that deficits in peripheral muscle function are common in this population [

34,

35]. Additionally, a sedentary lifestyle exacerbates these issues by impairing sensory integration and balance control [

34]. Incorporating balance training into pulmonary rehabilitation programs has been proven to enhance balance performance and reduce fall risk, underscoring the need for targeted interventions in this population [

36]. Balance-focused programs like SSE not only target balance but also cognitive skills, offering the potential to reduce the risk of falls in individuals with COPD [

37]. The significant effect of SSE on balance may be due to the need for both physical and mental focus during the exercise.

Participants had to focus on the squares and step sequences on the mat with each step, creating an exercise experience that actively engaged both balance and cognitive functions. This finding aligns with other multitasking exercises in the literature that specifically target balance [

26]. Studies reporting the effectiveness of multitasking exercises in improving balance and postural control support our findings [

37]. Additionally, it has been shown that such exercises can be a feasible and effective option when implemented via telerehabilitation [

27].

The strengthening exercise (SE) group also demonstrated improvements in some balance parameters post-intervention, though these were more limited compared to the SSE group. While SE may not directly target balance, increased muscle strength is known to enhance postural control and stability [

19]. The SE group primarily performed exercises focused on building muscle strength, which led to indirect benefits for balance. However, as their program did not specifically target balance, their stability outcomes were understandably less pronounced than those of the SSE group.

Paneroni et al. highlighted telerehabilitation as a safe and feasible option for COPD patients and emphasized the need for further research in this area [

38]. Participants continued their exercises at home via telerehabilitation after receiving face-to-face training, underscoring the value of home-based exercise programs. Our study shows that telerehabilitation can also be successfully applied to multitasking and strengthening exercises.

However, this study has some limitations. Firstly, since the sample size was relatively small, the generalizability of the findings may be limited. Conducting studies with larger participant groups could further enrich the literature. Additionally, only male participants were included in our study, so it is unknown whether the same results would be observed in female individuals. Some findings in the literature suggest that women may respond differently to physical and cognitive exercises [

39]. Therefore, future research should be designed with gender differences in mind.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that SSE and SE have the potential to improve cognitive functions and balance in individuals with COPD, and these exercises can be safely and effectively implemented via telerehabilitation. The inclusion of multitasking exercises in the rehabilitation processes of individuals with COPD could help improve their cognitive and physical functions and reduce the risk of falls. These findings could increase interest in using alternative rehabilitation methods in COPD management and pave the way for further research in this area.

5. Conclusions

This This randomized study investigated the effects of SSE and SE on cognitive functions and balance in individuals with COPD over an 8-week period. The results showed that there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of cognitive function improvement, but improvements were observed in both groups after the intervention. This finding supports the literature suggesting that physical activity positively impacts cognitive functions in individuals with COPD. While cognitive impairment is common in individuals with COPD, studies on managing and improving this condition remain limited. Physical exercises have been widely studied for their effects on cognitive functions in older adults, with generally positive outcomes. Our study demonstrates that similar improvements can be achieved in individuals with chronic conditions such as COPD.

Multitasking exercises, such as SSE, may be more effective at enhancing different aspects of cognitive abilities in older adults than single-task exercises.21 In particular, the cognitive improvement observed in the SSE group suggests that multitasking exercises may be more beneficial in this regard. SSE, as a program that combines both physical and cognitive challenges, is thought to have a synergistic effect on both mental and physical functions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Ö., E.T.Y. and S.K.; methodology, A.Ö. and E.T.Y.; investigation, A.Ö.; resources, A.Ö. and S.K.; data curation, A.Ö. and E.T.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Ö.; writing—review and editing, A.Ö., and E.T.Y.; supervision, E.T.Y. and S.K..; funding acquisition, A.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Bolu Abant Izzet Baysal University Clinical Researches Ethics Committee (protocol code 2020/14 and 04.02.2020).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data associated with this study are not publicly available but can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

In this section, you can acknowledge any support given which is not covered by the author contribution or funding sections. This may include administrative and technical support, or donations in kind (e.g., materials used for experiments).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| SSE |

Square-Stepping Exercise |

| SE |

Strengthening exercises |

| COPD |

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| SMMSE |

Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination |

| mMRC |

Modified Medical Research Council |

| CAT |

The COPD Assessment Test |

| CCI |

Charlson Comorbidity Index |

References

- Agusti, A.; Ambrosino, N.; Blackstock, F.; Bourbeau, J.; Casaburi, R.; Celli, B.; Criner, G.J.; Crouch, R.; Negro, R.W.D.; Dreher, M.; et al. COPD: Providing the right treatment for the right patient at the right time. Respir. Med. 2022, 207, 107041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, P.K.; Lind, L.; Persson, H.L. The Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Which Symptom is Most Important to Monitor? Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, ume 18, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siraj, R.A. Comorbid Cognitive Impairment in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD): Current Understanding, Risk Factors, Implications for Clinical Practice, and Suggested Interventions. Medicina 2023, 59, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stellefson, M.; Wang, M.Q.; Campbell, O. Factors influencing patient-provider communication about subjective cognitive decline in people with COPD: Insights from a national survey. Chronic Respir. Dis. 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campman, C.A.; Sitskoorn, M.M. Better care for patients with COPD and cognitive impairment. Lancet Respir. Med. 2013, 1, 504–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higbee, D.H.; Dodd, J.W. Cognitive impairment in COPD: an often overlooked co-morbidity. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2020, 15, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, A.E.; Cox, N.S.; Houchen-Wolloff, L.; Rochester, C.L.; Garvey, C.; ZuWallack, R.; Nici, L.; Limberg, T.; Lareau, S.C.; Yawn, B.P.; et al. Defining Modern Pulmonary Rehabilitation. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2021, 18, e12–e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuliadarwati, N.M.; Setiawan, A.; P, R.M. The Combination of Tera Gymnastics and Square Stepping Exercises on the Dynamic Balance of the Elderly. KnE Med. 85. [CrossRef]

- Muslimaini, M.; Mirawati, D.; Mutnawasitoh, A.R. Differences In The Effect Of The Combination Of Square Stepping And Gaze Stabilization With Square Stepping And Core Stability On Dynamic Balance In The Elderly. J. Ris. Kesehat. 2023, 12, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhanusali, H.; Vardhan, V.; Palekar, T.; Khandare, S. Comparative study on the effect of square stepping exercises versus balance training exercises on fear of fall and balance in elderly population. Int. J. Physiother. Res. 2016, 4, 1352–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, V.A.A.A.; Shigematsu, R.; Sebastião, E. Stepping towards health: a scoping review of square-stepping exercise protocols and outcomes in older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilaró, J.; Ramirez-Sarmiento, A.; Martínez-Llorens, J.M.; Mendoza, T.; Alvarez, M.; Sánchez-Cayado, N.; Vega, Á.; Gimeno, E.; Coronell, C.; Gea, J.; et al. Global muscle dysfunction as a risk factor of readmission to hospital due to COPD exacerbations. Respir. Med. 2010, 104, 1896–1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thongchote, K.; Chinwaro, U.; Lapmanee, S. Effects of scapulothoracic exercises on chest mobility, respiratory muscle strength, and pulmonary function in male COPD patients with forward shoulder posture: A randomized controlled trial. F1000Research 2024, 11, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beers, M.; Janssen, D.J.A.; Gosker, H.R.; Schols, A.M.W.J. Cognitive impairment in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: disease burden, determinants and possible future interventions. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2018, 12, 1061–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gore, S.; Blackwood, J.; Ziccardi, T. Associations Between Cognitive Function, Balance, and Gait Speed in Community-Dwelling Older Adults with COPD. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2021, 46, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butcher, N.J.; Monsour, A.; Mew, E.J.; Chan, A.-W.; Moher, D.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; Terwee, C.B.; Chee-A-Tow, A.; Baba, A.; Gavin, F.; et al. Guidelines for Reporting Outcomes in Trial Reports. JAMA 2022, 328, 2252–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2010, 1, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iamthanaporn, C.; Wisitsartkul, A.; Chuaychoo, B. Cognitive impairment according to Montreal Cognitive Assessment independently predicts the ability of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients to maintain proper inhaler technique. BMC Pulm. Med. 2023, 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaya, M.; Gurses, H.N.; Ucgun, H.; Okyaltirik, F. Effects of creative dance on functional capacity, pulmonary function, balance, and cognition in COPD patients: A randomized controlled trial. Hear. Lung 2022, 58, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesan, P. GOLD COPD report: 2024 update. Lancet Respir. Med. 2023, 12, 15–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molloy, D.W.; Standish, T.I.M. A Guide to the Standardized Mini-Mental State Examination. Int. Psychogeriat. 1997, 9 (Suppl. 1), 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charlson, M.E.; Carrozzino, D.; Guidi, J.; Patierno, C. Charlson Comorbidity Index: A Critical Review of Clinimetric Properties. Psychother. Psychosom. 2022, 91, 8–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanojevic, S.; Kaminsky, D.A.; Miller, M.R.; Thompson, B.; Aliverti, A.; Barjaktarevic, I.; Cooper, B.G.; Culver, B.; Derom, E.; Hall, G.L.; et al. ERS/ATS technical standard on interpretive strategies for routine lung function tests. Eur. Respir. J. 2021, 60, 2101499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garvey, C.; Bayles, M.P.; Hamm, L.F.; Hill, K.; Holland, A.; Limberg, T.M.; Spruit, M.A. Pulmonary Rehabilitation Exercise Prescription in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Review of Selected Guidelines: An Official Statement from the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabilitation Prev. 2016, 36, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanders, L.M.J.; Hortobágyi, T.; la Bastide-van Gemert, S.; Van Der Zee, E.A.; Van Heuvelen, M.J.G. Dose-response relationship between exercise and cognitive function in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, e0210036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, N.C.B.S.; Gill, D.P.; Owen, A.M.; Liu-Ambrose, T.; Hachinski, V.; Shigematsu, R.; Petrella, R.J. Cognitive changes following multiple-modality exercise and mind-motor training in older adults with subjective cognitive complaints: The M4 study. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0196356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, L.L.; Barnett, F.; Yau, M.K.; Gray, M.A. Effects of combined cognitive and exercise interventions on cognition in older adults with and without cognitive impairment: A systematic review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2014, 15, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sok, S.; Shin, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, M. Effects of Cognitive/Exercise Dual-Task Program on the Cognitive Function, Health Status, Depression, and Life Satisfaction of the Elderly Living in the Community. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 7848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, C.V.L.; Gobbi, S.; Pereira, J.R.; Vital, T.M.; Hernandéz, S.S.S.; Shigematsu, R.; Gobbi, L.T.B. Effects of square-stepping exercise on cognitive functions of older people. Psychogeriatrics 2013, 13, 148–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, S.R.; Low, K.; Okura, T.; Kawabata, M. Short-Term Effects of Square Stepping Exercise on Cognitive and Social Functions in Sedentary Older Adults: A Home-Based Online Trial. ACPES J. Phys. Educ. Sport, Heal. (AJPESH) 2022, 2, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturnieks, D.L.; George, R.S.; Lord, S.R. Balance disorders in the elderly. Neurophysiol. Clin. 2008, 38, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, K.J.; Atkinson, G.; Beauchamp, M.K.; Dixon, J.; Martin, D.; Rahim, S.; Harrison, S.L. Balance impairment in individuals with COPD: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Thorax 2020, 75, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liwsrisakun, C.; Pothirat, C.; Chaiwong, W.; Bumroongkit, C.; Deesomchok, A.; Theerakittikul, T.; Limsukon, A.; Tajarernmuang, P.; Phetsuk, N. Exercise Performance as a Predictor for Balance Impairment in COPD Patients. Medicina 2019, 55, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beauchamp, M.K.; Sibley, K.M.; Lakhani, B.; Romano, J.; Mathur, S.; Goldstein, R.S.; Brooks, D. Impairments in Systems Underlying Control of Balance in COPD. Chest 2012, 141, 1496–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLay, R.H.; O'Hoski, S.M.; Beauchamp, M.K. Role of Muscle Strength in Balance Assessment and Treatment in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Cardiopulm. Phys. Ther. J. 2019, 30, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkacher, W.; Mekki, M.; Tabka, Z.; Trabelsi, Y. Effect of 6 Months of Balance Training During Pulmonary Rehabilitation in Patients With COPD. J. Cardiopulm. Rehabilitation Prev. 2015, 35, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigematsu, R.; Okura, T. A novel exercise for improving lower-extremity functional fitness in the elderly. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2006, 18, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paneroni, M.; Colombo, F.; Papalia, A.; Colitta, A.; Borghi, G.; Saleri, M.; Cabiaglia, A.; Azzalini, E.; Vitacca, M. Is Telerehabilitation a Safe and Viable Option for Patients with COPD? A Feasibility Study. COPD: J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2014, 12, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villeneuve, S.; Pepin, V.; Rahayel, S.; Bertrand, J.-A.; de Lorimier, M.; Rizk, A.; Desjardins, C.; Parenteau, S.; Beaucage, F.; Joncas, S.; et al. Mild Cognitive Impairment in Moderate to Severe COPD. Chest 2012, 142, 1516–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).