1. Introduction

The future of the Internet appears to be intrinsically linked to the future of society, each new Internet-based technology building on previous ones to support social and economic activities. Artificial intelligence (AI) is an ever more part of daily human undertakings, a development that offers both opportunities, as well as numerous risks. Recent statistics show that adults are concerned about AI misuse in ethically risky ways in domains such as data-privacy violations and digital abuse that show the need for ethical governance [

1,

2]. As the sophistication and influence of large language models (LLM) increase, adopting such AI in socio-technical systems is perceived as a matter of concern due to the potential of exploitation, particularly in domains with critical trust and transparency demands [

3]. Taking into account ethical and trust issues ensures that AI innovations are adjusted to societal values without reinforcing exploitation and harm.

In a society in which individuals share a large part of their day online through various activities, the growing digital threats to the individual are exacerbated at a societal level. Add to this volatile environment the potential of ethical challenges brought on by the increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI) in socio-technical systems, and we are today in a position in which the individual is in a highly vulnerable position. This assertion is ever more true for young people, who are often more active online than other generations, more in search of human connections, and who often disregard the risks. In such an environment, the phenomenon of sextortion, both a coercion and a threat, is identified as a particularly damaging risk to young persons of any gender and mainly minors. Briefly, sextortion [

4] is defined as the act of threatening to disseminate explicit, intimate, or embarrassing images of a sexual nature without the consent of the victim, usually with the goal of obtaining more images, sexual favors, money, or other forms of compliance. This crime often involves the use of online platforms to coerce individuals by threatening the public release of private images unless demands are met.

The US Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) [

5] indicates "more than 13,000 reports of online financial sextortion of minors [with] at least 12,600 victims and led to at least 20 suicides" between October 2021 and March 2023. The victims are minors, typically "men between the ages of 14 to 17"; however, the issue is affecting all genders. In a study in 2024 [

6], the authors highlight that of close to 17,000 respondents, “14.5% reported victimization and 4.8% reported perpetration”, with men, LGBTQ+, and young victims more likely to report victimization than other categories. The same study affirms that “experiencing threats to distribute intimate content is a relatively common event, affecting 1 in 7 adults".

The present paper is situated at the intersection of ethical AI and blockchain as two fundamental technologies for Future Internet. In the online of tomorrow, which in an ideal case is characterized by decentralization, transparency, and societal trust, technological innovation must mitigate such pressing issues as sextortion [

7], in which perpetrators take advantage of sensitive private digital content to blackmail victims. Such misuse of data without consent is typical for a wider spectrum of ethical challenges connected to AI systems. Various types of exploitation are possible when there are occurrences of data privacy violations, bias, and lack. Thus, sophisticated technical solutions ensuring trust and security are required to tackle the increase in sextortion cases to prevent the severe consequences on the mental health and safety of victims.

In this context, current approaches lack a comprehensive set of guidelines for leveraging technology to make society safer, specifically using blockchain technology’s potential to enhance the trustworthiness, transparency, and ethical governance of AI systems in such sensitive contexts. This intersection of ethical AI development, social resilience, and digital ethics is at a critical point. The rapid emergence of new technologies, used indiscriminately by individuals and companies due to their obvious advantages to the point in which they become ubiquitous in everyday life, opens the door to a set of risks that we cannot fully comprehend, assess, or mitigate. However, this is also the stage in which, as Collingridge [

8] mentions in his famous dilemma, society must intervene to ensure that a specific technology is safely deployed and is a solution, not a threat. Sextortion serves as a relevant example of this intersection.

The integration of blockchain with AI is a novel opportunity for ethical AI development that emphasizes trust, transparency, and fairness. Consequently, our position paper stresses important societal challenges, especially the increasing phenomenon of digital threats such as sextortion. For improving societal resilience, we pursue in this paper the leveraging of blockchain decentralized architectures that pay attention to ethical frameworks for AI systems. With such an approach we aim to enable the mitigation of issues such as bias, privacy violations, and digital exploitation. Thus, the position paper proposes a structured set of guidelines for Digital Ethics that integrate AI and blockchain technologies to improve sextortion mitigation with the positive consequence of enhanced societal outcomes. As there exists an ever increasing need for the use of responsible technological solutions, the position paper shows that blockchain technologies offers a robust method for ensuring transparency and trust in AI-driven systems.

As a consequence, in this paper, we seek to utilize the combination of blockchain integrated with AI to explore a preventive and responsive set of guidelines to counter sextortion. To protect the victim from digital abuse with comprehensive support, such a set of guidelines must promote ethical AI systems that take into account privacy, security, and transparency concerns. To ensure the alignment of AI systems with the values of society are given, and to minimize the exploitation risk, systematic changes are required.

In this paper, we assume the position of advocating for the development of a comprehensive set of guidelines to take advantage of blockchain integration with AI systems, which has a significant transformative potential by enhancing trust, transparency, and ethical governance. The specific integration of blockchain (which brings decentralization, immutability, and auditability) into AI may be better managed via the implementation of a privacy-first framework. This set of guidelines must establish ethical standards to positively reinforce trust in AI systems and urgently address the unfortunate challenges of sextortion and similar digital threats. In ensuring that sensitive data are protected and not exploited for victimization, this article advocates an approach that is structured and decentralized to achieve a high degree of transparency, security, and accountability. Based on practical guidelines and preventive measures, the objective of the set of guidelines is for related stakeholders to develop AI systems of technical robustness with ethical alignment. Consequently, the risks of data misuse and AI-caused biases are mitigated, while privacy and trust must be prioritized. The ultimate objective of this position paper is to form a resilient digital environment for AI systems that contribute positively to society while paying attention to individual rights and safety.

The position paper tackles the ethical challenges of AI, specifically with an intersection of human cognition and behavior. The provision of actionable guidelines aims to foster the application and development of ethical AI systems. It contributes to strengthening societal resilience against digital threats such as sextortion by integrating decentralized blockchain-based concepts. The specific AI use cases are described first to show the potential of blockchain-integrated AI technologies to address pressing societal problems such as sextortion. Next, we identify a set of ethical and trust concerns that may occur during AI deployment to mitigate such problems. Hence, the challenges caused by privacy breaches, bias, and manipulation are highlighted.

As a consequence, this position paper provides a blockchain-decentralized set of guidelines, building on concepts such as decentralized internet infrastructure and user-controlled data ecosystems and using instruments such as decentralized machine learning and data wallets to address the issues mentioned above. Next, the set of guidelines explains practical consequences by providing the details for the technical steps and guidelines to adhere to in response to ethical challenges during the use of AI in socio-technical application contexts. Thus, the position paper guides the development of a structured blockchain-integrated set of guidelines that advances responsible AI use. Societal resilience is strengthened by this operationalized AI ethics consideration.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides the background by describing various technical concepts of blockchain and AI and also provides frameworks for the research conducted in this position paper.

Section 3 outlines potential ethical concerns for social AI applications by reviewing related literature and a case of an AI application to prevent cases of sextortion.

Section 4 proposes potential blockchain operations that can be used to address the ethical issues inherent in AI applications for social good.

Section 5 discusses the technical, economic, social, and legal implications of blockchain-integrated AI applications and proposes some set of implementation recommendations. Lastly,

Section 6 presents the conclusion and future work of this research.

2. Preliminaries

In this section, we provide the preliminaries for understanding the key essential technical concepts and frameworks that are foundational to this position paper. We first delve into the specific applications of blockchain and AI technologies that serve to address the ethical and societal challenges of our sextortion running case. Thus, it is important to introduce this way the core principles that drive the mentioned technological combination of blockchain technologies and AI. By understanding these foundational elements, the reader is in a position to better follow the argument of this position paper that investigates the interplay between blockchain, AI, and their ethical applications in building resilient digital infrastructures. Consequently,

Section 2.1 introduces the relevant concepts of AI and blockchain technologies, followed by

Section 2.2 that contrasts the domains of AI versus blockchain. Finally,

Section 2.3 introducing related research frameworks of importance for this position paper.

2.1. Related Technical Concepts

In this part of the position paper, we present some important concepts in AI and blockchain to improve the readability and understanding of the ideas expressed. Note that a full list of abbreviations is in the Appendix.

2.1.1. AI Concepts

Both machine learning (ML) and LLM models are necessary to realize the AI application that addresses the use case of sextortion, which is the focus of this paper. Hence, we first introduce certain algorithm types for realizing the ML and LLM relevant to this work. Then, we show that the performance of these algorithms is evaluated.

ML and LLM Algorithms: ML algorithms are models trained to identify patterns in a dataset and provide prediction by classifying categories of values, predicting continuous values, or organizing data in entirely new clusters [

9]. Hence, ML algorithms can be categorized into classification, regression and clustering algorithms. Yet, LLMs are algorithms that provide prediction by understanding patterns and relationships in an existing dataset to generate a completely new set of data in the form of natural language coherent for human understanding [

10,

11]. LLMs are a special type of natural language processor (NLP) realized from various deep learning algorithms focusing on generating human-readable content [

12].

Model performance metrics: Evaluation of AI models facilitates an understanding of their accuracy, hence providing a layer of transparency to these algorithms that are often considered a black box. Similar metrics used in evaluating classification ML algorithms, such as accuracy score and F1 score, are also used in assessing the correctness of predictions produced by LLMs. Generally, the accuracy score checks the quantity of correct predictions, while the F1 score checks the quality of the model using properties such as model precision and recall. Additional metrics are incorporated specifically for LLMs to check the fluency, coherency, and relevance of predictions generated [

13].

Algorithm execution steps: Both ML and LLM models follow similar execution processes involving data preparation, model training, and model execution. Data preparation involves all the steps of data pre-processing, such as data - acquisition, aggregation, transformation cleaning, normalization, etc., before they are fed into a model for training [

14]. The models are then trained to identify patterns and relationships in a dataset to predict a result for a given set of data questions or to generate an entirely new set of data. The models are optimized to achieve a particular level of performance criteria and then deployed for execution in a real live environment. One of the ways to optimize a model is by ensemble modeling such that several (similar) models are separately trained and their results combined using a consensus algorithm to generate a final result [

15,

16].

2.1.2. Blockchain Concepts

For the blockchain-related concepts, first, we describe a typical blockchain network and the consensus algorithm that supports it. Then, we describe smart contracts that run on decentralized networks and token-based systems to exchange assets and values within a blockchain network.

Blockchain network and consensus mechanisms: The blockchain network comprises peers and nodes, that represent entities that execute transactions within the network. Transactions are organized in blocks, cryptographically linked with previous transactions, and are redundantly recorded across peers, ensuring consistency of the blockchain’s state among all peers. Generally, blockchain networks fall into two categories: private and public. In private blockchains, permission is required to join the network while in public blockchains, anyone can join and execute transactions on the network [

17]. Before any transaction is accepted into the network, it undergoes validation using a specified consensus method. Public blockchains commonly employ proof-based consensus methods, such as proof of work and proof of stake, along with their variations. In contrast, private blockchains typically use voting-based consensus methods, often based on adaptations of Byzantine fault-tolerant systems [

18].

Smart contracts and tokenization: The computer programs running on the blockchains are commonly known as smart contracts. Consequently, different rules and conditions can be encoded within a smart contract, and are executed without the need to rely on a central entity for coordination [

19]. A blockchain application, also referred to as a decentralized application (DApp), can consist of several smart contracts. Smart contracts are also used to realize information assets and value exchange among the network participants. These values and digital assets can be represented in various types of tokens that exist in blockchain networks. Some common examples of tokens are utility and non-fungible tokens (NFTs). Utility tokens are fungible and are used to implement the ownership and transfer of values in blockchain networks. NFTs are commonly used to provide a unique representation of digital assets in a blockchain network [

20].

2.2. Contrasting the Core Domains: Blockchain versus AI

Blockchain technologies and AI are considered to be complementary and converging technologies. On the other hand, both technologies operate within their own fundamentally distinct domains, i.e., both blockchain technologies and AI serve their respective unique purposes and are based on very diverging operational principles. Blockchain is inherently designed with a focus on establishing trust, verification, and transparency in decentralized systems that require secure and immutable record-keeping. As such, blockchain technologies achieve this by employing decentralized consensus mechanisms, e.g., Proof of Work (PoW), Proof of Stake (PoS), and Byzantine Fault Tolerance (BFT), and so on [

21,

22]. The goal is to ensure data integrity without any reliance on a central authority as a trusted third party [

23]. Thus, this way, blockchain yields the ability to provide auditability, traceability, and tamper-proof transaction histories [

24]. Consequently, blockchain technologies have become indispensable in applications such as digital identity management, secure data sharing, and transparent financial transactions [

24].

AI, on the other hand, has its roots in data-driven intelligence with the foci on predictive analysis, pattern recognition, and automated decision-making [

25]. Thus, AI employs machine-learning algorithms and additionally large-scale datasets as well to discover insights, predict outcomes, and adapt to complex scenarios in real-time [

26,

27]. Differently to blockchain technologies, AI systems typically operate without transparency in their decision-making processes and instead excel in domains such as computational adaptability and dynamic responsiveness [

28]. AI is currently very widely applied in domains that require rapid and context-sensitive analysis, e.g., in fraud detection, personalized recommendations, and autonomous systems [

29,

30].

Despite these differences between blockchain technologies and AI, the integration exploration pursued in this position paper does not aim to merge these two distinct domains into a single framework. Instead, the aim of this position paper is to discover their complementary strengths. Blockchain’s trust mechanisms ensure that data integrity, secure provenance, and decentralized governance are critical aspects in applications that handle sensitive information [

31,

32]. On the other hand, the adaptive intelligence of AI for pattern identification and the generation of actionable insights addresses dynamic and evolving challenges, e.g., digital threats [

33,

34].

Without compromising these technologies, the combination of blockchains and AI yields the possibility of addressing complex social issues, e.g., sextortion, privacy violations, and digital exploitation [

35,

36]. Another example is that blockchain can secure the provenance of the data used in AI models to prevent a garbage in and garbage out scenario [

37]. Thereby, blockchain technology also ensures that sensitive data is not tampered with and remains private [

38]. Simultaneously, AI enhances the utility of blockchain by processing large data sets in a privacy-preserving manner [

39]. The goal for such an integrated approach is to ensure that the inherent strengths of blockchain and AI reinforce one another [

40]. While such blockchain and AI combining systems are more robust and trustworthy, they are also better positioned to tackle the complex ethical and societal challenges that are inherent for emerging digital ecosystems [

41].

2.2.1. Leveraging the Complementary Strengths of Blockchain and AI

While blockchain establishes trust, transparency, and tamper-proof data through decentralized records, AI focuses on dynamic data analysis and adaptive decision-making. These specific strengths complement each other to yield robust frameworks for tackling digital challenges [

38].

For example:

Blockchain ensures data integrity by providing immutable and auditable records, which is ideal for sensitive information management [

42].

AI enhances utility with privacy-preserving techniques by leveraging secure, verified data to detect patterns and threats, such as in the case of sextortion [

43].

The described integration allows blockchain to verify data inputs that are AI-generated. On the other hand, AI leverages blockchain to ensure accountability and traceability, thereby creating a system of synergies that is capable of addressing ethical and societal challenges [

44,

45].

2.3. Research Framework

We next introduce the relevant research frameworks that are foundational for analyzing and addressing complex ethical challenges in blockchain-based AI-driven systems, particularly in contexts such as the mitigation of problems related to the sextortion running case of this position paper.

2.3.1. Inter-Connected framework for AI, Blockchain and Ethics

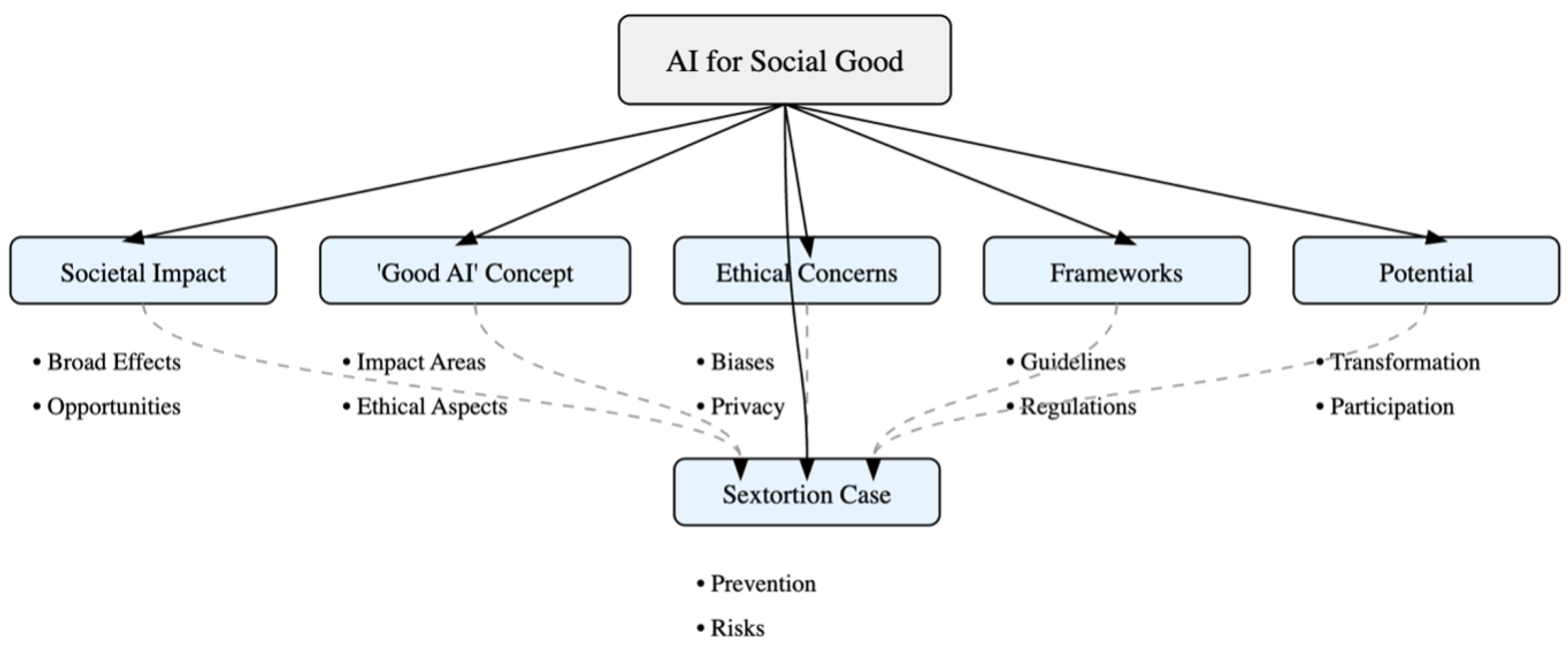

This part of the paper describes a framework that provides guidelines for the research conducted in this work. As shown in

Figure 1, the framework contains four layers. The first layer shows a high-level overview of blockchain integrated into AI applications for social good, such as sextortion mitigation. The second layer shows five ethical pillars relevant to AI applications for social media. Hence, the introduction of blockchain operations into AI applications will result in the

decentralization of control,

enhanced security,

transparency,

reduced bias and

regulatory compliance. Nevertheless, the integration of blockchain operations into AI applications will also raise several challenges. Hence, the first part of the third layer of the framework shows the

technical,

ethical,

economic and

legal implications of blockchain-integrated AI. The second part of the third layer shows the implementation considerations and recommendations for implementing blockchain-integrated AI for social good. The fourth layer shows the evaluation criteria and the resulting impacts when assessing blockchain-integrated ethical AI applications.

2.3.2. Framework Instantiation on the Paper

The adoption of the research framework layers in the various parts of this paper is shown below. Layer one is the high-level refinement of our position: the integration of specific blockchain operations into AI applications that address social issues mitigates important ethical concerns that affect this type of application. These are captured in the motivation of this work as shown in

Section 1. For the second layer of the framework, we conduct a literature review and case analyses of ethical issues in AI applications for the social good in

Section 3. The purpose of these analyses is to justify the five pillars of ethics and their impacts. Furthermore, in

Section 4, we describe in detail blockchain operations to mitigate the ethical issues identified initially. For the third layer, in

Section 5, we discuss the research implications of blockchain-integrated AI applications and propose a set of recommendations for the development of such applications. The fourth layer comprises future work in

Section 6 that will provide important criteria for evaluating blockchain-integrated AI applications for social good.

3. AI for Social Good and Ethical Concerns

3.1. Related Literature on AI for Social Good and Societal Resilience

The literature on AI for social good and societal resilience is vast, and the intersections between the concepts are numerous and highly complex. In the following section, we capture a snapshot of these interconnections by laying the basics of the concepts for a clearer understanding of the problem at hand. This snapshot is schematized in the following

Figure 2.

3.1.1. AI for Social Good

With its ability to both help and harm, AI has immense promise of producing multidimensional impacts. We should properly harness its abilities, especially regarding social issues. This potential to address societal challenges is proven by solutions such as conversational AI tools being deployed for issues such as mental health awareness. For example, Citation [

46] shows how an AI-based emotional chatbot can be used to detect mental issues such as depression by analyzing facial expressions and textual content produced by users, while studies by [

47] and [

48] describe AI language models to identify depression and suicide prevention. However, there is a gap in understanding how AI may support the mitigation of long-term psychological effects and how it may be integrated into mental health frameworks. Often proposed individually, solutions discussed fail to consider how each component might work synergistically as part of a holistic support system maximizing AI’s ability to meaningfully impact individuals and society. A balanced and holistic approach to embedding AI within existing complex support networks can maximize its capacity to benefit individuals and society at large.

3.1.2. Broad Societal Impact of AI

The societal impact of AI goes beyond the microlevel of individuals interacting with technology, and the literature is booming with analyses of various aspects of its potential uses for social good. Before 2021, there were less than 450,000 results in Google Scholar on AI and social good; as of April 2024, there were more than 5 million, with the potential for an increase in this number (see also the analysis by[

49]). For example, [

50] explores the “potential economic, political, and social costs”, while [

51] investigates the ethical applications of AI in social systems, paving the way for a nuanced discussion on the topic of AI use in addressing social challenges. Similar issues are addressed in [

52], following an assertion that the wide implementation of AI systems goes beyond engineering to an intersection of technology and society, and proposes an illustration of the concept of ”ethically designed social computing”. From the positive aspects of ”accuracy, efficiency and cost savings” [

53], issues such as privacy, trust, accountability, and bias must be considered [

54]. Diverse aspects related to education and critical thinking can lead to unequal deployment of such technology and ultimately to greater societal polarization [

55], an exacerbation of social inequality [

56], and dissolution of societal resilience. Similarly to the previous assertion, the critical analysis of this wide range of insights lacks clarity on the way biases and inequities resulting from AI may be mitigated to enhance societal resilience. The literature so far remains at the status quo level and assessment without dwelling on the next steps of a risk management process: risk interconnection and mitigation or reduction.

3.1.3. Conceptualizing a ”Good AI” Society

The idea of a ’good’ AI society is not new. The work of [

57] starts a conversation on ten potential areas of social impact: "crisis response, economic empowerment, educational challenges, environmental challenges, equality and inclusion, health and hunger, information verification and validation, infrastructure management, public and social sector management, security, and justice”. In the same line, the work of [

58] maps 14 ethical implications for AI in digital technologies: “dignity and well-being, safety, sustainability, intelligibility, accountability, fairness, promotion of prosperity, solidarity, autonomy, privacy, security, regulatory impact, financial and economic impact and individual and societal impact.” All these implications and potential impacts are weaved into a very complex ontological system of a society existing dually (in real and in digital) in which AI represents a new layer. This society must become resilient, and any type of behavior leveraged by technology that undermines this resilience must be tackled properly. Expanded from engineering and ecology to social contexts, resilience is an essential topic, relying on holistic approaches, inter- and multi-disciplinary frameworks, and normative epistemological questions [

59,

60].

An interplay of individual, institutional, and community capacities, societal resilience is based on coping, adaptation, and transformation [

61]. Although AI is a potential tool to improve individual resilience (particularly given the theory of resource conservation, as discussed by [

62]), its role in community resilience is only beginning to be acknowledged. Firstly, societal resilience is promoted by creating common spaces of innovation and transformability [

63], adaptable and flexible systems and structures, with AI potentially supporting the operational resilience of cyber systems as the backbone of a global digital society [

64]. Secondly, modeling social systems for improved resilience leads to the implementation of agent-based approaches, with AI systems scrutinized for their own resilience [

65]. In this growing corpus of literature, the need for more empirical research on how AI can be integrated to validly enhance social resilience without introducing new risks and vulnerabilities is demonstrated.

3.1.4. Sextortion and AI

Sextortion, defined as a form of sexual exploitation in which victims are, e.g., extorted with their sexual images [

66], is a form of dissolution of societal resilience. It exploits vulnerabilities in social and economic structures and corrodes the integrity of society by breaking down structures meant to protect privacy and security. In this context, a case study on sextortion as a form of cyber abuse and growing societal concern, particularly in the case of young people and / or minors, can be a niche illustration of the ethical challenges of AI. The harms of sextortion involve dignity, well-being, safety, and individual impact, touching on privacy, security, and societal consequences.

Although in most countries sextortion is often not legally defined as a crime, authorities prosecute related crimes in varying ways between jurisdictions, categorizing it as child pornography, harassment, extortion, stalking, hacking, and violations of personal privacy [

67]. For instance, in the USA, sextortion is defined in two primary ways: as a threat to share a victim’s private sexual images to extort something from them or as coercion to make the victim send sexual material under threats. Federal law typically prosecutes sextortion as extortion or child pornography, depending on the victim’s age [

68]. The member states of the European Union also prosecute sextortion in a variety of ways according to domestic legislation, often through extortion, privacy violation, and sexual harassment charges that account for individual and broad social impacts - from defamation and integrity infringements to media manipulation and gender inequalities [

69]. For example, in France, illicit coercing sexual favours faces civil and criminal charges such as sexual assault, extortion, blackmail, or corruption [

69]. In addition to this, the Digital Republic Law covers issues related to the unauthorized use of personal data, including non-consensual sexual imagery and deepfakes [

67]. Similarly, data protection laws are used to protect against sextortion in Germany, Spain, and Hungary, with legislation in the latter specifically including provisions for sexual exploitation, defined as coercing someone into sexual activities through threats, and, since 2013, sexual blackmail and extortion [

69].

Efforts to combat this cybercrime may benefit from the use of AI [

70,

71], while some countries (Indonesia, for example) are setting regulatory frameworks in place to deal with sexual violence crimes, including sextortion (the TPKS law of 2022 [

72]). On the opposite side of the spectrum, AI can be shown to leverage the sextortion efforts of perpetrators through dating apps [

73] or deepfakes [

74]. Despite timid advances in the topic, both in the literature and in regulatory and legal frameworks, the significant gap in empirical studies demonstrating the effectiveness of technological solutions (AI or other) in preventing and mitigating sextortion has yet to be addressed.

3.1.5. Ethical Risks of AI

In contrast, artificial intelligence (AI) is considered to pose significant risks to humans and societies if it is not ethically developed and used. Researchers, corporations and NGOs, along with policymakers, explore maximizing AI’s benefits and capabilities. Yet fast progress and implementation of AI solutions may outpace understanding of unintended effects. The challenges posed by AI are diverse, ranging from algorithmic biases to the potential for humans to inherit AI errors. Fundamentally, AI must be fair, transparent, explainable, responsible, trustworthy, and reliable. Without these attributes, it remains a ’black box’ where developers may themselves struggle to comprehend how the system generates its responses, particularly in the case of generative AI tools such as LLMs. It is of utmost importance that society (including all stakeholders) takes immediate steps to prevent AI tools from engaging in unpredictable behaviors and establish the credibility and trustworthiness essential to society.

3.1.6. Frameworks for Ethical AI: Guidelines and Ethical Principles, Regulatory and Legal Frameworks

In [

75], it is emphasized that evaluating technologies in isolation is futile due to their social implications. In this view, a series of multi-layered frameworks have been developed to assess AI’s impact potential for societal good. In [

76], an analysis of AI solutions was performed using four criteria: breadth and depth of impact, potential implementation of the solution, risks of the solutions, and synergies in the area of opportunity. The risks section deals with ‘Bias / Fairness / Transparency Concerns’ and ’Need for Human Involvement’, highlighting the evident need for an ethical assessment of the solutions.

Although [

77] claims that even before the widespread use of LLM, there was a need for a unified vision of the future of AI, the proposed guidelines fail to find a common thread. In their investigation of 84 guidelines, [

78] highlight the consensus on fundamental AI ethics while noticing the high variation in how the principles are implemented. In the same line, [

79] underline the lack of detailed guidance on the same implementation. Based on [

80], on the ethics of algorithms, [

81] propose 7 essential factors for AI for Good: “(1) falsifiability and incremental deployment; (2) safeguards against the manipulation of predictors; (3) receiver-contextualized intervention; (4) receiver-contextualized explanation and transparent purposes; (5) privacy protection and data subject consent; (6) situational fairness; and (7) human-friendly semanticisation”, with the latter works on the same topic by [

82] and [

83]. Similarly, [

84] refer to the need for a value-sensitive design, defined as a method to integrate values into technological solutions, while [

85] advocate for a socially responsible algorithm and [

86] propose an ethics penetration testing for AI solutions.

Various countries are implementing AI regulations in a struggle against the black-box complexities of AI, particularly in balancing its benefits and potential harm. In the United States, the Biden administration has introduced an executive order advocating for ’Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy AI’; Canada proposed an Algorithmic Impact Assessment; the World Economic Forum an AI Procurement in a Box, and the OECD a Framework on AI Strategies [

87].

The European Union is also in the process of enacting its first AI regulations, although it requires a more integrated approach from the member states and governments [

88]. Still, existing frameworks, such as the Assessment List for Trustworthy AI (ALTAI), play a key role in guiding the development of fair and ethical AI [

89]. ALTAI, in particular, protects people’s fundamental rights [

90]. Moreover, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) protects user privacy [

91]. The efficacy of these frameworks has yet to be completely determined. For example, [

90] argue that we must interpret AI frameworks like ALTAI from a systems theory standpoint to be applied in various disciplines, allowing "the integration of a rich set of tools, legislation, and approaches". The scalability of ethical AI frameworks, in the context of their proper practical application in highly sensitive areas, such as sextortion, is also an area of potential improvement for current research. With solutions at the incipient level, the way in which they will build upon existing frameworks and further develop appears to be a problem of the future.

Regulating AI through data privacy laws presents several challenges. These challenges include controlling personal data, ensuring the right to access personal data, adhering to the purpose limitation principle, and addressing the lack of transparency in AI decision-making processes. Furthermore, AI systems often introduce privacy risks by obscuring algorithmic biases, complicating the enforcement of the right to be forgotten, and affecting the right to object to automated decision-making (ADM) [

92].

Regardless of the scope, relevance, or enforcement of these regulations, AI applications pose significant risks beyond the range of data privacy laws. For example, there are other concerns that AI regulation should address: issues related to self-management of personal data, the guarantee of access to personal data, the lack of transparency of the AI decision process, hidden algorithmic biases, the right to be forgotten and the right to object ADM [

92].

3.1.7. Transformative Potential of Ethical AI for a Resilient Society

The social good of AI goes beyond technology fixes; it calls for societal transformation. The ethical practices of AI require the participation of the communities that it seeks to enhance so that the development of AI solutions is informed by those they intend to help [

93].

Although significant progress has been made in investigating the potential of AI for societal resilience, there are two noticeable gaps: (a) a critical gap in understanding the perpetuation of biases, especially in the context of sextortion, linking social, anthropological, and technological concerns, and (b) a lack of critical analysis on the potential risks and consequences, with most of the literature corpus being polarized or presenting pinpointed solutions. Moreover, in the current literature, there is a significant lack of insight into the scalability and practical implementation of ethical AI frameworks, particularly in combating sextortion. This status quo underscores the need for both an ethical framework as the one proposed in this position document and for comprehensive studies that critically assess limitations.

Considering the concepts presented in this section, based on the reviewed literature, we identify a series of roles and impacts linked to the aspects highlighted in the problem statement from the Introduction. These aspects are presented in the following

Table 1.

3.2. A Case of AI Application for Social Good

3.2.1. AI Applications That Raise Ethical Concerns

The opportunity to harness AI technologies such as LLM and ML algorithms to address the widespread challenge of sextortion underlines the need for ethical AI frameworks. A practical and clear use that concerns human behavior and cognition, with a considerable risk of affecting individuals emotionally, underscores the necessity of transforming broad ethical principles into actionable guidelines and, lastly, allowing for responsible technological applications.

An approach designed to assist individuals affected by sextortion that combines machine learning with LLM may have the following features, each contributing to support throughout every stage of the process [

119]:

The "Prevention” stage— Before an actual sextortion event, potential victims may use highly personalized, gamified, and engaging educational resources to increase their awareness of related risks. Furthermore, AI, through personalized gamified interactive learning experiences, can support people at risk to cultivate self-confidence, the lack of which represents a risk factor for sextortion.

The "Provision of Instant Aid” stage - AI can automatically identify coercive behaviour through customized gamification and tracking unusual behavior patterns to accurately red flag possible victims. Through LLM-based chatbots, AI may provide live support for sextortion victims to reduce the probability of them spiralling into self-destructive behaviors - another characteristic of the subjects of such a social-stigma-carrying occurrence. For example, the chatbot can recommend social services resources that address problems such as suicide and self-injury, which can stem from sextortion incidents.

The “Continuous Support” stage: The traumatic nature of a victim’s sextortion case leads to it not being resolved once the event is considered closed. Individuals affected by such a case go through a recovery period that can also be supported by AI through tools that allow self-assessment and / or direct emergency contact with social services or law enforcement.

3.2.2. Ethical Issues from the Case of Sextortion AI Application

Although posing a higher risk to society in large and vulnerable groups in particular, the phenomenon of sextortion may be both mitigated, for example, by providing behavioural red flags for vulnerability and enhanced by AI, for example, by using deep fakes to convince victims, while more research should address this polarized context. As previously stated, there is a significant literature gap in empirical studies, with the goal of using AI to support societal resilience thus hindered by a series of challenges researchers encounter when addressing this topic (sextortion), such as:

Limited Empirical Research at risk of obsolence: As both the AI-sextortion and blockchain-sextortion areas are in their infancy, empirical research remains very limited. Only a few studies deal with the use of AI (or blockchain) to detect, prevent, or mitigate the phenomenon, and even fewer focus on the nexus of the three concepts. This lack of transdisciplinary research holds back technology from having direct applicability in solving social problems, and may have major implications in the long run. Studies might become obsolete or irrelevant as the time needed for academic research can be excessively long compared to the speedy pace of technological changes.

Interdisciplinary Complexity: Apart from the two technologies considered, aspects related to psychology, sociology, anthropology, ethics, law, and economy must be integrated to gain a clear perspective and propose potential solutions.

Ethical Considerations: By involving aspects related to sensitive data, privacy, and consent, as well as automated human profiling, ethical issues are a major concern in both research about sextortion and research into the use of AI. Another ethical issue is related to bias and generalization of assumptions and results. The data utilized to train artificial intelligence significantly impacts its effectiveness. If not enough data is available (see also the next limitation), or if the data is biased and not representative (the ethical concern), then the solution is irrelevant and may do more harm than intended, by generating inequitable outcomes.

Data Use and Sensitivity: Extensive exploitation of data for educating AI or carrying out research is hindered by its sensitive nature—posing potential harm to victims, its distribution across multiple jurisdictions and platforms, in addition to the numerous ethical clearances needed from different local and global organizations. This international perspective is also affected by distinct legal and regulatory frameworks, leading to the inability to propose shared policies or resolutions.

4. Blockchain Operations that Address Ethical and Trust Issues in AI Systems

In tackling the significant ethical and trust challenges present in AI systems, blockchain technology is proven to be complementary. Using the inherent characteristics of transparency, decentralization, and immutability, a blockchain can provide novel solutions that reinforce trust in AI applications, a much needed characteristic in the context of the sextortion case under discussion. This section explores how integrating blockchain into AI systems can establish robust frameworks to mitigate risks such as data tampering, bias, and lack of transparency. We delve into the practical mechanisms and strategies where blockchain can enhance data security, provide immutable audit trails, and ensure compliance with ethical guidelines. Consequently,

Section 4.1 presents the federated machine learning that blockchains enable. Next,

Section 4.2 shows that the so-called blockchain data wallets protect sensitive data from misuse.

Section 4.3 briefly discusses blockchain-based privacy-conscious data processing, and

Section 4.4 suggests that blockchain token economy models produce positive contributions to AI systems. Together, these approaches outline a structured approach to increase public trust in AI applications while protecting individual rights. Finally,

Section 4.5 discusses the practical applications of blockchain-based AI systems.

4.1. Blockchain-Enabled Federated Machine Learning

Distributed processing of patient/victim data, where ML algorithms are run locally on the organization and institution where the data is generated, aims to improve the trustability of AI systems that address social issues. This prevents a single entity from aggregating and controlling sensitive user data.

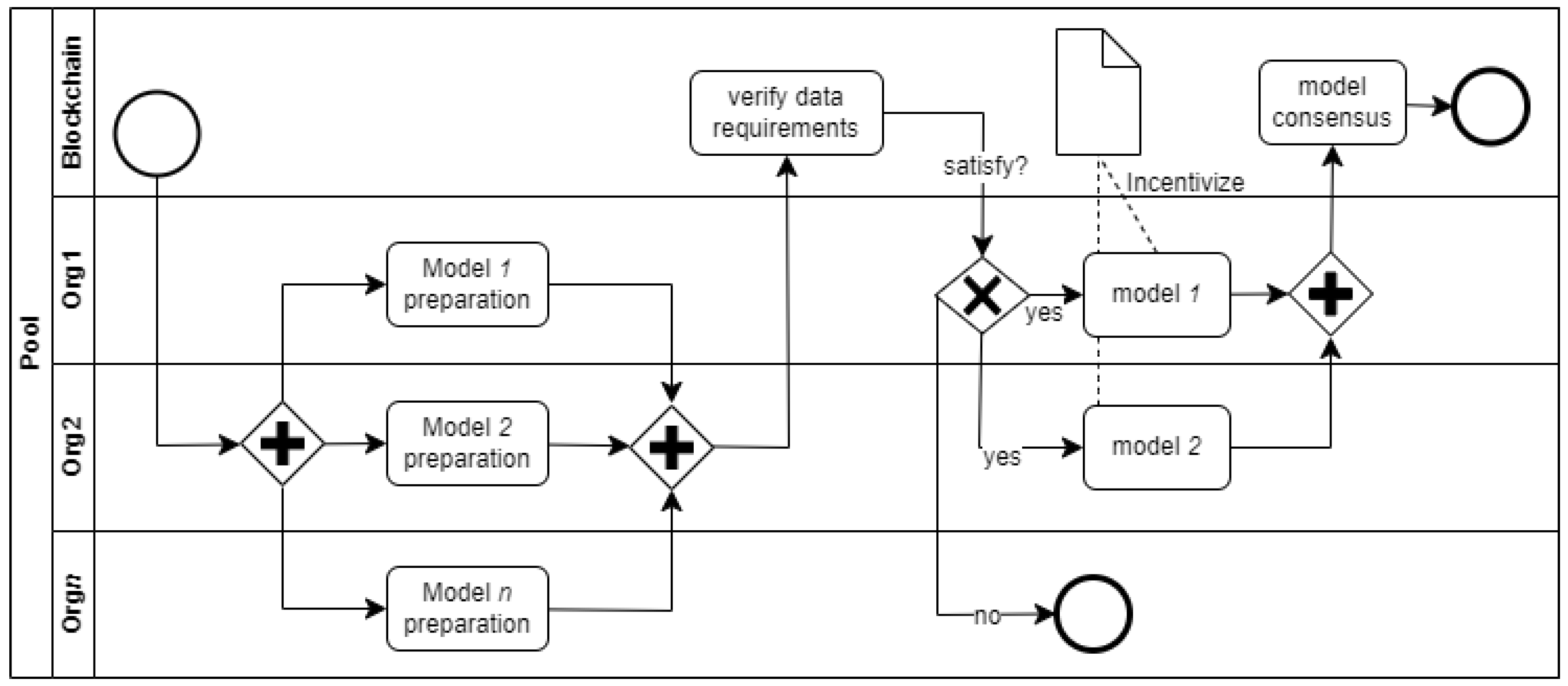

Figure 3 adapted from [

120,

121] shows a simplified process representation of federated AI systems (a form of ensemble modeling) integrated with blockchain technologies. The process consists of several organizations

org1...n where each organization controls the data and ML models used in the system. To ensure that all models maintain consistent and acceptable performance, a smart contract performs a requirement verification. Hence, only models (within specific organizations) that meet the data and model performance requirements are selected for use. A consensus smart contract combines the results of individual models to produce the final result of the system.

4.2. Blockchain-Enabled Data Wallet

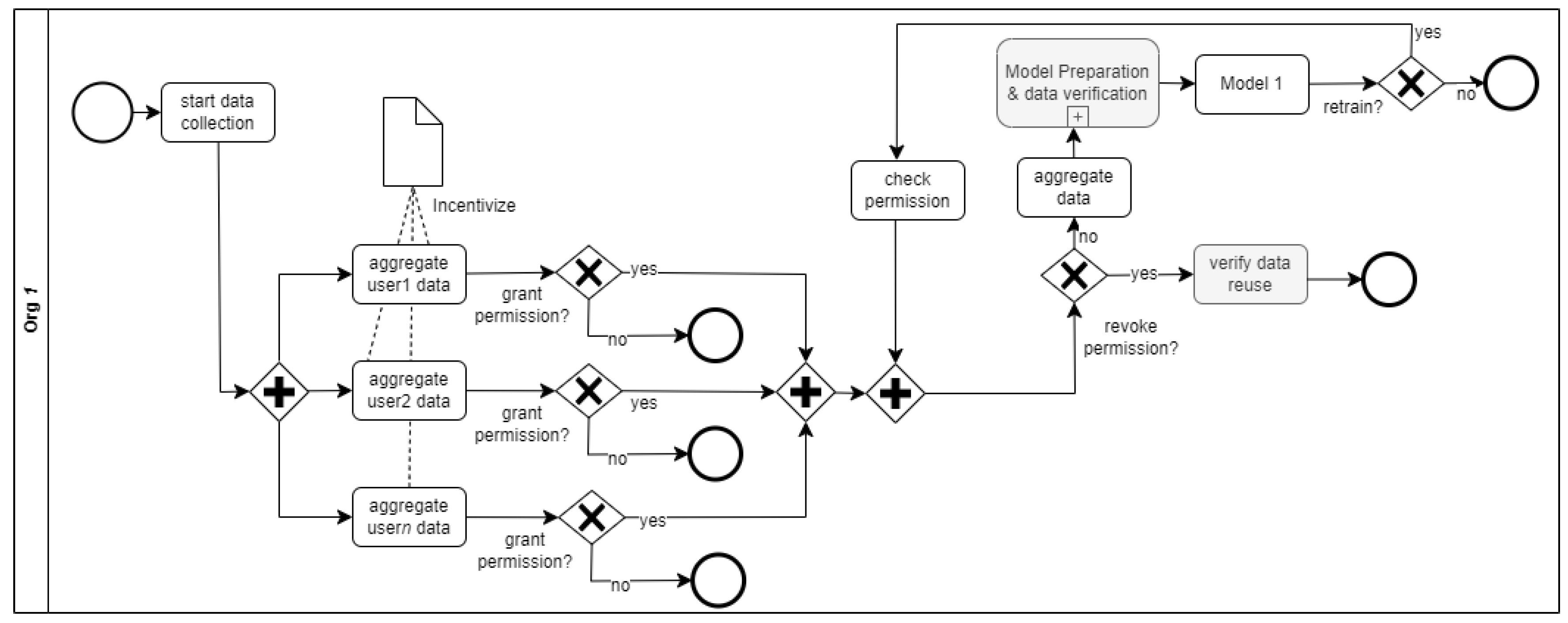

A mechanism in which patients and victims of sextortion have control over their data shared in the AI system to train and improve the performance of algorithms protects data owners from abuse and exploitation.

Figure 4, adapted from [

122], shows a process representation of an organization (

ogr1) that processes user data for an AI system that addresses social problems. Users (data owners) can grant or deny permission for the use of their data in the system. Furthermore, data owners can revoke permission for the continued use of their data in retraining or improving the AI system. The users also can verify that their data have not been used or re-used by the AI system.

4.3. Privacy Aware Data Processing

Integration of the zero-knowledge proof (ZKP) system can address additional privacy concerns related to information verification within the proposed AI system, decentralized machine learning, and data wallet. The ZKP provides a privacy-aware system for processing and verifying information without revealing sensitive information. The following data verification is potentially possible in the AI system represented in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 - data requirement, model performance, and data reuse verification. Although these verification possibilities generally improve the transparency and trustability of the AI system, such verification procedures must be carried out without leaking user confidential information. Although verifications are performed on the blockchain using smart contracts, the data must remain in the owners’ data wallets within the organizations they are generated. Hence, a cryptographic ZKP of information used in training the AI model can be stored on the blockchain, and users can, therefore, verify that their information has not been used without revealing their data. Following the same manner, ZKP can be used to confidentially verify the data requirements and performance of the constituent models without revealing information about the data used in training the models.

4.4. Token Economics Model

A well-designed token economic model can address the funding challenges of AI systems that deliver social good by incentivizing users (data owners) and organizations (which host ML models) to positively contribute to the system. Users, who in this case potentially represent victims of sextortion, can be rewarded with tokens for contributing their data for the training of the LLM and ML models. The main idea is to encourage victims of sextortion to share their data in a secure and privacy-preserving way to train AI models that can support future victims. The same token distribution model can be adapted to reward organizations that host the various ML and LLM algorithms to ensure the availability and continuous contribution of their hosted models to the system. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, the organizations that host the various models that are part of the federated learning are incentivized to produce models that meet the minimum performance requirements of the system, and users (such as data owners) are incentivized to grant permission for their data use in the system.

4.5. Practical Applications of Blockchain and AI

Combining blockchain technologies and AI yields advantages in addressing real-world challenges in which privacy, transparency, and accountability are essential. Thus, we discuss the practical applications of these combined technologies. Their complementary roles in tackling societal issues are explored, e.g., sextortion and AI accountability while ensuring regulatory compliance.

4.5.1. Sextortion Mitigation with Federated Learning

The running case of sextortion is a digital threat that exploits sensitive personal data, which the combination of blockchain technologies and AI can address. The traditional method of sensitive data centralization for data analysis is problematic, as this potentially compromises data privacy. With the application of federated learning techniques, AI solutions are trained across distributed datasets without transferring sensitive data of individuals. Consequently, the latter are ensured to remain localized and secure in this way [

123].

With blockchain technology being a transparent and tamper-proof ledger that tracks consent and data usage, a combination with AI strengthens the framework [

124]. In the running case of sextortion, blockchain documents when and how data is used during AI training processes. Furthermore, such an approach ensures compliance with privacy regulations such as GDPR [

125]. By securely verifying that training adheres to ethical and regulatory standards, blockchain and federated learning together create a robust system for sextortion mitigation that prioritizes both security and privacy.

4.5.2. Blockchain-Audited AI Accountability

AI systems that operate in sensitive domains, such as flagging potential sextortion cases, face increasing scrutiny over the fairness and reliability of their decision-making processes. Blockchain introduces an immutable auditing mechanism for these AI-driven decisions, thereby enabling transparency and accountability. For example, while an AI model is used for detecting sextortion patterns in large context-based data sets, the related AI decision-making rationale is logged securely on a blockchain [

126]. The process integrity and fairness is verified by auditors without compromising the data privacy of the individuals involved.

Law enforcement systems are a domain where the practical implementation of blockchain-based AI would be sensible. In such a scenario, the large datasets related to sextortion threats are analyzed by an AI system and subsequently, the AI’s decision-making pathways are recorded on a blockchain. These records can be accessed by the auditors and other relevant authorities to validate the conclusions of the AI. Thereby, a compliance with the ethical and legal standards is ensured while simultaneously safeguarding the sensitive information of individuals [

127].

4.5.3. Comparison of Blockchain and AI Roles

In

Table 2, we illustrate the unique contributions of blockchain technology and AI, respectively, while highlighting how their integration addresses specific challenges.

The roles of blockchain and AI are summarized in the table, which lists for challenges such as the running case of sextortion the ways to enhance both privacy and accountability. On the one hand, blockchain ensures the immutability and traceability of data and decisions and AI, on the other hand, provides dynamic capabilities for threat detection and mitigation. This combination yields a robust regulatory framework [

128].

5. Discussions: Research Implications

With respect to the position put forward in this paper, the integration of blockchain technologies and AI has real-world implications and poses also challenges, which we discuss in this section. The ethical implications of such an integration require a critical analysis of the effects on societal structures that are decentralized and disintermediated, challenge policy formation, and also transform existing governance models. The ethical implications in light of the technological implications also require a discussion of the possible benefits and threats that emerge. Thus, our goal is to generate insight into the compliance with ethical standards of blockchain-enhanced AI systems so that societal silence and justice are strengthened.

In the remainder,

Section 5.1 discusses the complexity of the integration of blockchain and AI together with the innovation potential.

Section 5.2 discusses the ethics issues for the integration of the AI blockchain from a technology neutrality perspective.

Section 5.3 discusses the important issue of bias counteracting and discrimination.

Section 5.4 addresses the economic and social equity that is affected by blockchain-integrated AI. Next,

Section 5.5 explores the management of diverse legal and regulatory challenges in the integration of blockchain and AI. Finally,

Section 5.6 addresses the implementation considerations for blockchain integrated ethical AI.

5.1. Integration Complexity and Innovation

There are considerable challenges and opportunities related to the integration of blockchain technologies with AI frameworks. This holds specifically for cases from the domains such as healthcare or finance. As blockchain technologies are instrumental in ensuring integrity and immutable traceability, the authors in [

104] discuss the beneficial effects on managing and securing e-healthcare data records. In this way, blockchains manage the immutability and accessibility of such data records while simultaneously also adhering to the corresponding regulations, e.g., the GDPR and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) [

129].

In reference to

Section 4, we stress that blockchain technology is instrumental to protect transactions that are part of AI-supported decision making processes. In [

108], the authors support this statement by analyzing the means to increase blockchain technologies to ensure that sensitive data in sectors such as healthcare are managed transparently and with a high degree of security. In this way, blockchains support the notion of trust in system stability.

In [

130], the authors stress the need for an interdisciplinary research approach that involves technologists, ethicists, policymakers, etc. Such collaborative research aims to ensure that the integration of AI and blockchain technologies meets not only technical standards. In addition, strict ethical norms must also be adhered to in order to improve the societal trust that leads to broad adoption.

The increased trust and transparency that blockchain technologies deliver affect not only the e-healthcare sector positively with improved efficiency. Thus, as the authors in [

131,

132] discuss, the specific attributes of the blockchain of decentralization, immutability, and transparency strengthen the trust of users. Furthermore, as discussed in [

108], the disintermediation of centralized system structures achieves increased process efficiencies.

In relation to the sextortion case, unauthorized changes in sensitive e-health data become impossible with the use of blockchain technologies, in that the data in transactions of the user are recorded securely and permanently. Thereby, blockchain technologies secure the privacy-assured access to sensitive data of victims to the point that trust is fostered in the management of sextortion cases. In addition, in [

106,

109,

110], the authors investigate the secure management of e-health data across various systems and the positive role of blockchain technologies in this context. Briefly, the latter proposes a way to reduce data breach risks while ensuring fast patient-data access.

In taking advantage of their complementary strengths, integrating blockchain technology and AI into one system can be used to address complex societal challenges. Risks such as adversarial attacks, are significantly reduced by ensuring robust data integrity via blockchain’s immutable and tamper-proof nature [

133]. If data integrity directly impacts decision-making outcomes, then these AI application strengths are particularly critical [

134].

Adaptive capabilities by AI tackle evolving threats like sextortion. For example, sensitive distributed data can be analyzed with AI enabled by federated learning without compromising privacy [

125]: Thus, federated learning enables AI ensuring compliance with ethical and legal standards [

135]. A robust system for mitigating threats is created while safeguarding privacy with blockchains that provide a transparent ledger to record consent and data usage securely [

136]. Thus, ethical and secure frameworks are created for data processing by the exemplified synergy that blockchain and AI together create [

137].

5.2. Technological Neutrality and Ethics

Specifically, to address sextortion as a sensitive issue, the integration of AI and blockchain technologies is guided by policy development. As shown in

Section 4, technological development (blockchain-integrated AI) evolves at a rapid pace, which poses a challenge to policy frameworks. In addition, future developments must be monitored since they affect the significance of ethical standards. In [

138], the integration of blockchain and AI significantly improves security and privacy, which is important for the protection of victims of sextortion. Furthermore, in [

139], the authors stress the immediate need for adaptive policy measures to address digital threats such as sextortion in combination with the use of digital currencies.

In reference to the position statement of this paper, we stress the need for a comprehensive framework to leverage the interaction of blockchain technologies and AI to improve the transparency, security, and accountability of digital environments. Managing robust reporting mechanisms addresses sextortion cases effectively flanked by enacting safeguarding policies to protect the data and privacy of individuals. The enforcement of policies becomes significantly effective due to the immutable traceability of events in a decentralized context that blockchain technologies infer. As shown in federated decentralized learning (in

Section 4.1), data policies can be managed and enforced locally within the organizations where the data are produced. In [

140], the authors discuss the improvement of corporate governance transparency and accountability by integrating blockchain technologies and AI. Thus, we infer that this technology integration is also beneficial for privacy and security management in sextortion contexts. In addition, the authors in [

141] stress the establishment of trust in very secure infrastructures, which is achieved by the integration of blockchain technologies and AI.

Based on the descriptions of the blockchain-based operations shown in

Section 4, we infer regulatory requirements can be enforced dynamically without the involvement of intermediaries. We ensure thereby automatically the adherence to privacy laws and standards for data protection. This is very important for sextortion cases that involve sensitive data that must be protected with a high degree of confidentiality. In [

117], the authors show that blockchain technologies are instrumental in defining and implementing access policies for the protection of personal data, which improves overall privacy and security.

In legal scenarios, the capabilities of the mentioned blockchain operations are essential in establishing a transparent and tamper-proof foundation for all interactions and transactions. Consequently, the authors in [

142] discuss the access and sharing policies for data access enforcement that make recorded actions easily auditable. Mapped into a sextortion context, such a blockchain system delivers undeniable evidence of misconduct to consequently involve the appropriate civil services as per the definitions in smart contracts. Also in [

143], the authors explore the changes in judicial systems to ensure that legal procedures are transparent to effectively combat crimes such as sextortion.

Policies themselves must be flexible and adaptable to enable dynamic policy enforcement by blockchain systems. In [

144], the authors point out that the enforcement of existing policies and their adaptation to novel technological innovations can be facilitated by blockchain technologies. In addition, the authors in [

145] propose the notion that blockchain technologies coupled with AI analysis yield insight that allows the evolution of policy structures that are more fluid and less rigid as policy frameworks.

Significant technological and regulatory advantages are provided by the intersection of blockchain and AI. To reduce the risks associated with data poisoning and bias, the immutability of blockchain ensures that AI models train on verified and tamper-proof data [

125]. Enabling decentralized AI training with federated learning further strengthens privacy protection, which aligns with GDPR principles of data localization and minimization [

146].

Additionally, it is possible to enhance a system’s transparency and accountability with blockchain-audited AI operations. For example, one can enable an external verification of model outputs with the audit trails that are generated and maintained by a blockchain to document AI decision-making processes [

124]. In sensitive applications such as identifying sextortion threats, this is particularly valuable since fairness and reliability are paramount [

147].

From a regulatory perspective, the integration supports compliance with GDPR and the AI Act. Blockchain ensures traceability and adherence to data localization laws, while adaptive AI systems enable dynamic risk assessment and policy compliance [

148]. The use of smart contracts further automates regulatory enforcement, ensuring real-time adherence to evolving legal standards [

149].

5.3. Counteracting Bias and Discrimination

For sensitive domains, such as in sextortion cases, securing distributed data collection is a very essential capability of blockchain integrated into AI. The danger is the potential bias based on a limited representative dataset, which is an undesirable situation. The combination with blockchain-enabled federated machine learning ensures that data are aggregated across various organizations, demographics, and locations where sextortion occurs to curb AI biases. The position statement of this paper stresses that ethical AI operations are necessary to strengthen societal resilience, thus, according to [

150], blockchain technologies are instrumental in addressing algorithmic fairness to achieve ethical AI.

Expanding on blockchain operations in

Section 4, we explore the ways blockchain technology mitigates AI biases by ensuring transparent data management and verifications. Measures to mitigate against AI biases that lead to unfair outcomes are a detailed review of data sources, training methodologies, and decision-making policies. For an application context such as sextortion, AI must be free of bias to ensure fairness and justice when AI aims to detect and analyze abuse occurrences. In [

100], the authors stress the importance of audit trails on blockchains for data to consequently be immutably traceable. In this way, the integrity of the system is enhanced. Also in [

98], the authors investigate identification methods to mitigate biases in AI where blockchain technologies support AI transparency and fairness.

The effectiveness of blockchain is most exploited when all AI operations are recorded on the chain to document all data access instances, record model training, and decision making. Such immutably logged data on blockchains constitute a permanent record of all AI activities to allow auditors to check the adherence to ethical standards. In [

103], the authors show that blockchains improve transparency in sensitive data environments due to established immutability and auditability. The discussion in [

96] also reveals that blockchains in AI applications ensure that operations and decision-making are valid.

Systems that comprise blockchain operations integrated into AI applications can be designed to be flexible and upgradeable to adapt to changes when biases are detected in AI algorithms. Such changes may include retraining of AI models with improved representative datasets. Consequently, a traceable history of change events is recorded to enhance transparency and accountability. The authors in [

97] point out that AI operations can be reliably scrutinized when all modifications are mutably logged on a blockchain. Also in [

94], blockchain use enables auditing of AI events stored to ensure that adjustments do not violate ethical guidelines.

With blockchain integration into AI, the participation of stakeholders in defining and changing rules is allowed for AI operations. For the sextortion running case, the implications are that community stakeholders such as victim advocacy groups are included, alongside legal experts, ethicists, etc., to decide on the training and application of AI models. In order to democratize the AI decision-making process, decentralized control enhances transparency and equity. In [

99], the authors explain that blockchains have the potential to improve stakeholder participation in AI governance and positively affect fairness and transparency. In [

102], a discussion about the regulatory aspects of blockchain stresses the capacity of AI governance integration to involve various stakeholders with their input. Hence, ethical guidelines are always followed.

Blockchain-based AI systems create frameworks that align with societal and ethical demands with addressing the integration complexity and enhancing technological neutrality. This integrated approach establishes a foundation for addressing future challenges and mitigates current digital threats[

151]. The synergy between blockchain’s data integrity and AI’s dynamic adaptability represents a transformative step toward ethical, regulatory-compliant, and socially equitable technological solutions [

152,

153].

5.4. Economic and Social Equity

The link of sextortion with economic and social equity is three-pronged: from causes to consequences and specific implications for policies and practices. Thus, sextortion may be driven by socioeconomic factors (such as economic uncertainty, gender issues, and patriarchal societies), as specified in [

154,

155]. However, it may also lead to micro and macroeconomic effects. For example, it can cause economic vulnerability and instability in victims [

154], increase social inequality, and perpetuate stigma and ostracizing of already marginalized individuals [

111].

We posit that blockchain-integrated AI (BIAI) and other technologies that improve transparency, security, efficiency, and accountability may address these issues. Decentralization (as an intrinsic part of BIAI) plays a crucial role in empowering victims of sextortion by giving them more control over their data and incentivizing them when they share such data for training and retraining of AI systems. Instead of centralized storage, the distribution of data over a blockchain network enhances individual autonomy and mitigates data breach risks [

105], while addressing data ownership and privacy concerns [

156]. This distributed model also ensures that data are less susceptible to misuse, another essential element for victims of sextortion [

157]. This is because data are processed in the locations (and organizations) where the data is generated. Decentralization affects more than just control of individual information - it alters the very structure of power in data ownership. Historically, data were at risk of misuse, as access to them was gate-kept by a small number of large corporations and government agencies, as described in [

158]. This status quo is rebalanced through blockchain technology, which allows individuals to own and control their digital assets, leading to consumer empowerment and fairness in making algorithmic decisions. For the use of legal and social services, this build-up on a more inclusive data set provides a scenario in which algorithmic decision making can be less biased than currently [

159,

160,

161].

Using the concept of decentralization, as delivered by BIAI, alongside transparency and enhanced security, we can identify several directions in which economic and social equity in the context of mitigating sextortion may be discussed. The structure of the discussion moves from micro to macro and from victim to perpetrator, highlighting how BIAI can positively affect this chain. First, BIAI ensures democratized access to financial resources and digital services [

162], promoting economic equity according to the token economic model shown in

Section 4. This feature may lead to providing a secure platform for sextortion victims to seek help without the danger of additional exploitation.

Second, BIAI supports social equity by increasing security through privacy-aware data processing enabled by ZKP systems. For victims of sextortion or potential victims, this level of security and accountability is essential because it gives them confidence that their data are being stored and handled properly and that there is accountability in such instances when a data breach occurs [

163]. This empowers victims, encouraging them to seek help and resources for protection; in addition, the blockchain side of BIAI facilitates decentralized reporting systems which in turn permit sextortion victims to report incidents securely and anonymously. As a consequence, the risk of social ostracizing is mitigated and social equity is advanced by safeguarding the well-being of victims.

Third, when the victim does not come forward, BIAI can support identifying red flags of such an event occurring, empowering law enforcement with analytics to improve understanding of related crime patterns. For example, the findings of [

164] show that blockchain and AI in combination improve surveillance and tracking capabilities by ensuring detailed, secure, and immutable records of all transactions. Applying these results of the finance industry to sextortion, as well as other similar exploitative issues, we posit that by using BIAI, abuse patterns in transactions can be highlighted, allowing for the prevention of injustice[

164].

Fourth, in addition to this BIAI-supported recognition of victims, AI-supported educational and awareness programs, with or without blockchain-enhanced digital micro-credentials [

165], may prove beneficial in supporting and empowering vulnerable individuals. These types of programs equip victims with the knowledge to recognize and respond to threats.

Fifth, on the law enforcement side, after the victim has been identified and the sextortion crime has been committed, BIAI can support the justice system in several ways, ethically, by following a supranational ethical framework [

113]:

Transparent legal processes - BIAI may guarantee that legal decisions are transparent and auditable, which will help combat corruption [

166]. In turn, corruption, through bribery and the influence of perpetrators, has been proven to affect effective prosecution of sextortion cases, for example, in South Africa with migrants [

111,

167].

Tamper-proof evidence - Blockchain can ensure the integrity of the chain of custody [

168,

169], while AI can be employed in the analysis and management of evidence and digital forensics [

159,

170,

171,

172].

Support for marginalized groups - One of the groups most affected by sextortion is represented by migrants and refugees [

111], who are also affected by a lack of easily verifiable identification and may have access to legal aid and support through blockchain-based identity verification [

173].

Sixth, while the crime has been proven and aid is directed towards the victim, BIAI may also bring efficiency and security. Blockchain-enabled anonymous payment mechanisms, further down the mitigation process, ensure that the aid aimed at victims reaches recipients securely and anonymously without the risk of misappropriation [

174]. Blockchain has been proven to improve social welfare programs and promote equitable resource distributionby ensuring that funds are not smuggled into intermediaries [

175].

Last, at a more macro level, we must consider a two-pronged perspective: on the one hand, the role of AI in the use of decentralized data to improve decision-making [

176],and, on the other hand, the transformative role of AI and blockchain for significant parts of society [

107]. This dual perspective leads us to reassert the need for an integrated approach to ensure the proper and ethical use of BIAI.

5.5. Managing Diverse Legal and Regulatory Challenges in the Integration of Blockchain and AI

With the integration of blockchain and AI, two transformative technologies are merged into system applications that are governed by distinct regulatory frameworks [

40]. On the one hand, blockchain technologies operate within a legal landscape that focuses on concerns for decentralization, data immutability, and financial regulation [

177]. On the other hand, the regulatory framework of AI stresses different aspects versus the one for blockchains, e.g., privacy, transparency, and ethical considerations [

178]. Given this divergence, specific challenges must be taken into account for an effective deployment of blockchain-integrated AI systems [

179,

180].

In

Table 3, we provide an overview of the key regulatory aspects associated with blockchain and AI integration. The leftmost column lists the primary regulatory challenges, followed by two columns detailing the respective focuses of blockchain and AI in addressing these challenges. The rightmost column outlines proposed mitigation strategies, which are expanded upon in the following subsections. This table serves as a roadmap for understanding the detailed discussion of regulatory issues and solutions presented below.

The regulatory challenges summarized in

Table 3 highlight the fundamental tensions between blockchain and AI systems, as well as practical strategies to bridge these gaps. Each of the proposed mitigations is further elaborated in the subsections below, demonstrating their applicability to real-world blockchain-AI integrations.

5.5.1. Blockchain Regulations

The unique challenges that blockchain technologies face with respect to regulatory hurdles are primarily related to the immutability feature [

181]. The latter is not in line with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) that introduces the "right to erasure" [

182]. An additional source of conflicts with regulations results from decentralized blockchain applications often involving cross-border operations, which poses a challenge to achieving legal compliance with the EU’s Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA) [

183]. Consequently, it is important for blockchain technologies to achieve an alignment with international legal standards to ensure the lawful sharing and processing of data, specifically when such systems handle sensitive data [

38,

184].

5.5.2. AI Regulations

Regulation for the AI domain prioritizes the safeguarding of user privacy, ensuring the transparency of algorithms, and the mitigation of risks related to bias and discrimination [

185,

186]. Thus, the European AI Act focuses on this domain by establishing clear guidelines for the assessment of risk and by achieving an explainability in AI systems [

187,

188]. However, the reliance of AI on very large and extensive datasets poses many novel challenges that conflict with important blockchain principles that require the minimization of data and the decentralization of control [

189]. Consequently, the resulting discrepancies between these two important domains create regulatory tensions [

190,

191].

5.5.3. Legal Conflicts in Integration

Integrating these two technologies accentuates several regulatory conflicts [