Submitted:

26 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Data Extraction and Analysis

Methodological Quality Appraisal

3. Results

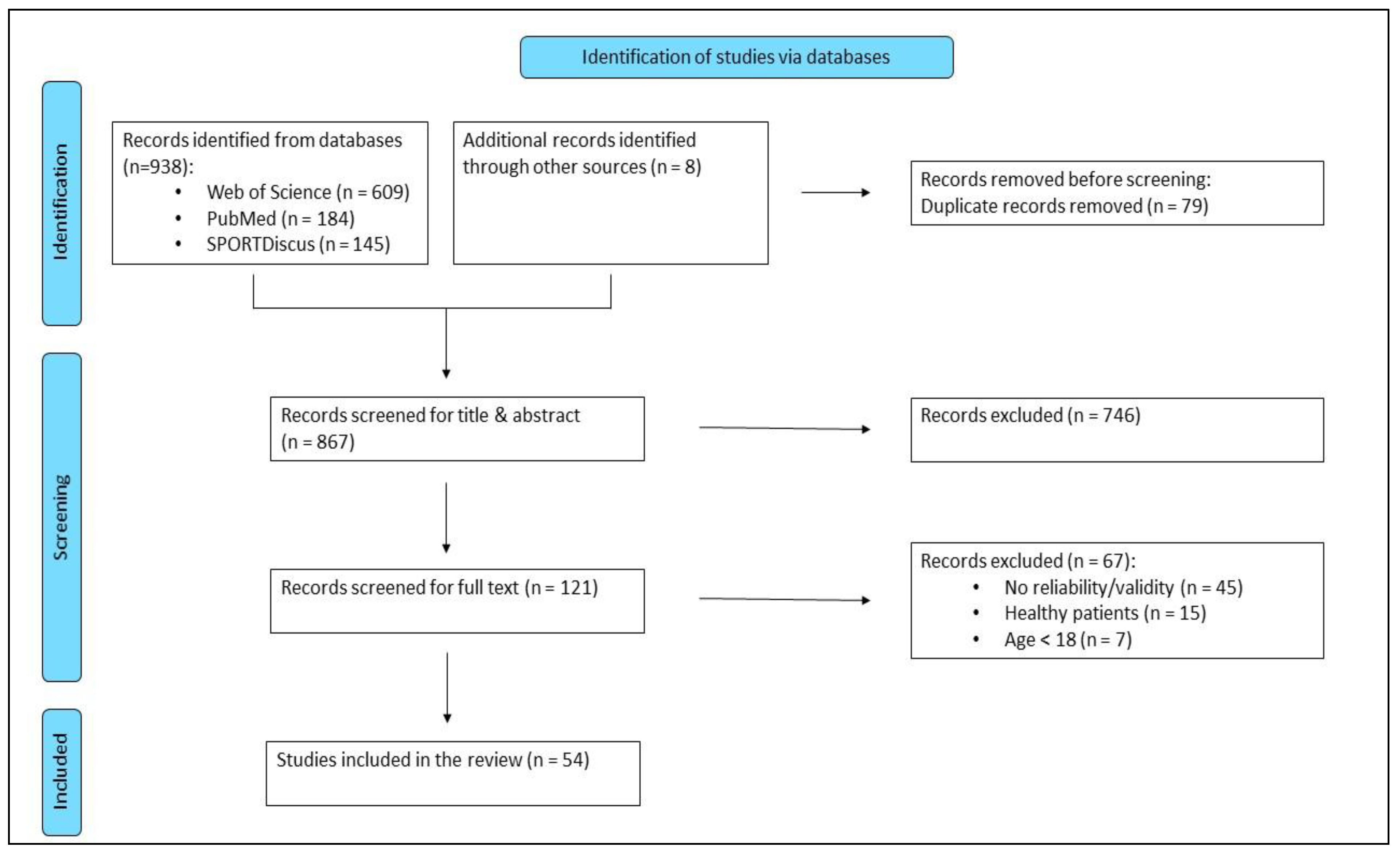

Study Selection

Study Analysis

Validation, Reliability and Feasibility Outcomes

Methodological Quality of the Included Studies

4. Discussion

5. Limitations and Future Research Perspectives

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dionne, C. E.; Dunn, K. M.; Croft, P. R. Does back pain prevalence really decrease with increasing age? A systematic review. Age Ageing 2006, 35(3), 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rapoport, J.; Jacobs, P.; Bell, N. R.; Klarenbach, S. Refining the measurement of the economic burden of chronic diseases in Canada, 2004.

- Duncan, R. P.; van Dillen, L. R.; Garbutt, J. M.; Earhart, G. M.; Perlmutter, J. S. Low Back Pain--Related Disability in Parkinson Disease: Impact on Functional Mobility, Physical Activity, and Quality of Life. Phys Ther 2019, 99(10), 1346–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, B. J.; Potter, J. F. Cardiovascular causes of falls. Age Ageing 2001, 30 Suppl 4, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntosh, S. J.; Lawson, J.; Kenny, R. A. Clinical characteristics of vasodepressor, cardioinhibitory, and mixed carotid sinus syndrome in the elderly. The American journal of medicine 1993, 95(2), 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montero-Odasso, M.; Schapira, M.; Duque, G.; Soriano, E. R.; Kaplan, R.; Camera, L. A. Gait disorders are associated with non-cardiovascular falls in elderly people: a preliminary study. BMC Geriatr 2005, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verghese, J.; Holtzer, R.; Lipton, R. B.; Wang, C. Quantitative gait markers and incident fall risk in older adults. The journals of gerontology. Series A, Biological sciences and medical sciences 2009, 64 (8), 896–901. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J. A.; Stabbert, H.; Bagwell, J. J.; Teng, H.-L.; Wade, V.; Lee, S.-P. Do people with low back pain walk differently? A systematic review and meta-analysis; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Salchow-Hömmen, C.; Skrobot, M.; Jochner, M. C. E.; Schauer, T.; Kühn, A. A.; Wenger, N. Review-Emerging Portable Technologies for Gait Analysis in Neurological Disorders. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2022, 16, 768575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, S. R. Quantification of human motion: gait analysis-benefits and limitations to its application to clinical problems. Journal of biomechanics 2004, 37(12), 1869–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, T. B.; Salgado, D. P.; Catháin, C. Ó.; O’Connor, N.; Murray, N. Human gait assessment using a 3D marker-less multimodal motion capture system. Multimed Tools Appl 2020, 79 (3-4), 2629–2651. [CrossRef]

- Abou, L.; Wong, E.; Peters, J.; Dossou, M. S.; Sosnoff, J. J.; Rice, L. A. Smartphone applications to assess gait and postural control in people with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders 2021, 51, 102943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, U.; Barbado, D.; Olsen, S.; Alder, G.; Elvira, J. L. L.; Lord, S.; Niazi, I. K.; Taylor, D. Validity and Reliability of a Smartphone App for Gait and Balance Assessment. Sensors 2021, 22(1), 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parmenter, B.; Burley, C.; Stewart, C.; Whife, J.; Champion, K.; Osman, B.; Newton, N.; Green, O.; Wescott, A. B.; Gardner, L. A.; Visontay, R.; Birrell, L.; Bryant, Z.; Chapman, C.; Lubans, D. R.; Sunderland, M.; Slade, T.; Thornton, L. Measurement Properties of Smartphone Approaches to Assess Physical Activity in Healthy Young People: Systematic Review. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2022, 10(10), e39085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, H.; Zheng, H.; Wang, H.; Gawley, R.; Yang, M.; Sterritt, R. Feasibility Study on iPhone Accelerometer for Gait Detection. In Proceedings of the 5th International ICST Conference on Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare; IEEE, 2011. [CrossRef]

- McGuire, M. L. An Overview of Gait Analysis and Step Detection in Mobile Computing Devices. In 2012 Fourth International Conference on Intelligent Networking and Collaborative Systems; IEEE, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Del Din, S.; Godfrey, A.; Mazzà, C.; Lord, S.; Rochester, L. Free-living monitoring of Parkinson's disease: Lessons from the field. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2016, 31 (9), 1293–1313. [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, A.; Ginis, P.; Hardegger, M.; Casamassima, F.; Rocchi, L.; Chiari, L. A Mobile Kalman-Filter Based Solution for the Real-Time Estimation of Spatio-Temporal Gait Parameters. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2016, 24 (7), 764–773. [CrossRef]

- Ginis, P.; Nieuwboer, A.; Dorfman, M.; Ferrari, A.; Gazit, E.; Canning, C. G.; Rocchi, L.; Chiari, L.; Hausdorff, J. M.; Mirelman, A. Feasibility and effects of home-based smartphone-delivered automated feedback training for gait in people with Parkinson's disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2016, 22, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- Hanbyul Kim; Hong Ji Lee; Woongwoo Lee; Sungjun Kwon; Sang Kyong Kim; Hyo Seon Jeon; Hyeyoung Park; Chae Won Shin; Won Jin Yi; Jeon, B. S.; Park, K. S. Unconstrained detection of freezing of Gait in Parkinson's disease patients using smartphone. In 2015 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC); IEEE, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ivkovic, V.; Fisher, S.; Paloski, W. H. Smartphone-based tactile cueing improves motor performance in Parkinson's disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2016, 22, 42–47. [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier, F.; Taylor, K. I.; Kilchenmann, T.; Wolf, D.; Scotland, A.; Schjodt-Eriksen, J.; Cheng, W.-Y.; Fernandez-Garcia, I.; Siebourg-Polster, J.; Jin, L.; Soto, J.; Verselis, L.; Boess, F.; Koller, M.; Grundman, M.; Monsch, A. U.; Postuma, R. B.; Ghosh, A.; Kremer, T.; Czech, C.; Gossens, C.; Lindemann, M. [Duplikat] Evaluation of smartphone-based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson's disease clinical trial. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2018, 33 (8), 1287–1297. [CrossRef]

- Jesus, M. O. de; Ostolin, Thatiane Lopes Valentim Di Paschoale; Proença, N. L.; Da Silva, R. P.; Dourado, V. Z. Self-Administered Six-Minute Walk Test Using a Free Smartphone App in Asymptomatic Adults: Reliability and Reproducibility. International journal of environmental research and public health 2022, 19 (3). [CrossRef]

- Pepa, L.; Verdini, F.; Spalazzi, L. Gait parameter and event estimation using smartphones. Gait & posture 2017, 57, 217–223. [CrossRef]

- Abou, L.; Peters, J.; Wong, E.; Akers, R.; Dossou, M. S.; Sosnoff, J. J.; Rice, L. A. Gait and Balance Assessments using Smartphone Applications in Parkinson's Disease: A Systematic Review. J Med Syst 2021, 45(9), 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Annals of Internal Medicine 2009 (151), 264–269. [CrossRef]

- NHLBI, N. I. Study Quality Assessment Tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed 2024-12-27).

- Abou, L.; Alluri, A.; Fliflet, A.; Du, Y.; Rice, L. A. Effectiveness of Physical Therapy Interventions in Reducing Fear of Falling Among Individuals With Neurologic Diseases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2021, 102(1), 132–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Venkataraman, V.; Zhan, A.; Donohue, S.; Biglan, K. M.; Dorsey, E. R.; Little, M. A. Detecting and monitoring the symptoms of Parkinson's disease using smartphones: A pilot study. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2015, 21 (6), 650–653. [CrossRef]

- Omberg, L.; Chaibub Neto, E.; Perumal, T. M.; Pratap, A.; Tediarjo, A.; Adams, J.; Bloem, B. R.; Bot, B. M.; Elson, M.; Goldman, S. M.; Kellen, M. R.; Kieburtz, K.; Klein, A.; Little, M. A.; Schneider, R.; Suver, C.; Tarolli, C.; Tanner, C. M.; Trister, A. D.; Wilbanks, J.; Dorsey, E. R.; Mangravite, L. M. Remote smartphone monitoring of Parkinson's disease and individual response to therapy. NATURE BIOTECHNOLOGY 2022, 40 (4), 480–487. [CrossRef]

- Clavijo-Buendía, S.; Molina-Rueda, F.; Martín-Casas, P.; Ortega-Bastidas, P.; Monge-Pereira, E.; Laguarta-Val, S.; Morales-Cabezas, M.; Cano-de-la-Cuerda, R. Construct validity and test -retest reliability of a free mobile application for spatio-temporal gait analysis in Parkinson's disease patients. Gait & posture 2020, 79, 86–91. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.-Y.; Bourke, A. K.; Lipsmeier, F.; Bernasconi, C.; Belachew, S.; Gossens, C.; Graves, J. S.; Montalban, X.; Lindemann, M. U-turn speed is a valid and reliable smartphone-based measure of multiple sclerosis-related gait and balance impairment. Gait & posture 2021, 84, 120–126. [CrossRef]

- Banky, M.; Clark, R. A.; Mentiplay, B. F.; Olver, J. H.; Kahn, M. B.; Williams, G. Toward Accurate Clinical Spasticity Assessment: Validation of Movement Speed and Joint Angle Assessments Using Smartphones and Camera Tracking. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 2019, 100(8), 1482–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamy, V.; Garcia-Gancedo, L.; Pollard, A.; Myatt, A.; Liu, J.; Howland, A.; Beineke, P.; Quattrocchi, E.; Williams, R.; Crouthamel, M. Developing Smartphone-Based Objective Assessments of Physical Function in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: The PARADE Study. Digital biomarkers 2020, 4(1), 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, Y. A.; Rhea, C. K.; Ross, S. E. Modified proximal thigh kinematics captured with a novel smartphone app in individuals with a history of recurrent ankle sprains and altered dorsiflexion with walking. CLINICAL BIOMECHANICS 2023, 105, N.PAG-N.PAG. [CrossRef]

- Tang, S. T.; Tai, C. H.; Yang, C. Y.; Lin, J. H. Feasibility of Smartphone-Based Gait Assessment for Parkinson's Disease. JOURNAL OF MEDICAL AND BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERING 2020, 40(4), 582–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, J. L.; Kangarloo, T.; Gong, Y. S.; Khachadourian, V.; Tracey, B.; Volfson, D.; Latzman, R. D.; Cosman, J.; Edgerton, J.; Anderson, D.; Best, A.; Kostrzebski, M. A.; Auinger, P.; Wilmot, P.; Pohlson, Y.; Jensen-Roberts, S.; Müller, M.; Stephenson, D.; Dorsey, E. R.; Tarolli, C.; Waddell, E.; Soto, J.; Hogarth, P.; Wahedi, M.; Wakeman, K.; Espay, A. J.; Gunzler, S. A.; Kilbane, C.; Spindler, M.; Barrett, M. J.; Mari, Z.; Dumitrescu, L.; Wyant, K. J.; Chou, K. L.; Poon, C.; Simuni, T.; Williams, K.; Tanner, N. L.; Yilmaz, E.; Feuerstein, J.; Shprecher, D.; Feigin, A.; Botting, E.; Parkinson Study Grp Watch Pd. Using a smartwatch and smartphone to assess early Parkinson's disease in the WATCH-PD study over 12 months. NPJ PARKINSONS DISEASE 2024, 10 (1). [CrossRef]

- Alexander, S.; Braisher, M.; Tur, C.; Chataway, J. The mSteps pilot study: Analysis of the distance walked using a novel smartphone application in multiple sclerosis. MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS JOURNAL 2022, 28(14), 2285–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balto, J. M.; Kinnett-Hopkins, D. L.; Motl, R. W. Accuracy and precision of smartphone applications and commercially available motion sensors in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin 2016, 2, 2055217316634754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, G. C.; Vittinghoff, E.; Iyer, S.; Tandon, D.; Kuhar, P.; Madsen, K. A.; Marcus, G. M.; Pletcher, M. J.; Olgin, J. E. Accuracy and Usability of a Self-Administered 6-Minute Walk Test Smartphone Application. CIRCULATION-HEART FAILURE 2015, 8 (5), 905–913. [CrossRef]

- Capecci, M.; Pepa, L.; Verdini, F.; Ceravolo, M. G. A smartphone-based architecture to detect and quantify freezing of gait in Parkinson's disease. Gait & posture 2016, 50, 28–33. [CrossRef]

- Herman Chan; Zheng, H.; Wang, H.; Newell, D. Assessment of gait patterns of chronic low back pain patients: A smart mobile phone based approach. In 2015 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM); IEEE, 2015, pp 1016–1023. [CrossRef]

- Chien, J. H.; Torres-Russotto, D.; Wang, Z.; Gui, C. F.; Whitney, D.; Siu, K. C. The use of smartphone in measuring stance and gait patterns in patients with orthostatic tremor. PloS one 2019, 14 (7). [CrossRef]

- Costa, P. H. V.; Jesus, T. P. D. de; Winstein, C.; Torriani-Pasin, C.; Polese, J. C. An investigation into the validity and reliability of mHealth devices for counting steps in chronic stroke survivors. Clin Rehabil 2020, 34(3), 394–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, R. J.; Ng, Y. S.; Zhu, S.; Tan, D. M.; Anderson, B.; Schlaug, G.; Wang, Y. A Validated Smartphone-Based Assessment of Gait and Gait Variability in Parkinson's Disease. PloS one 2015, 10(10), e0141694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isho, T.; Tashiro, H.; Usuda, S. Accelerometry-Based Gait Characteristics Evaluated Using a Smartphone and Their Association with Fall Risk in People with Chronic Stroke. JOURNAL OF STROKE & CEREBROVASCULAR DISEASES 2015, 24 (6), 1305–1311. [CrossRef]

- Juen, J.; Cheng, Q.; Schatz, B. [Duplikat] A Natural Walking Monitor for Pulmonary Patients Using Mobile Phones. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2015, 19(4), 1399–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez, W. O. C.; Higuera, C. A. E.; Fonoff, E. T.; Oliveira Souza, C. de; Albicker, U.; Martinez, J. A. E. Listenmee® and Listenmee® smartphone application: Synchronizing walking to rhythmic auditory cues to improve gait in Parkinson’s disease. Human Movement Science 2014, 37, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, J.; Rens, N.; Savage, D.; Nielsen-Bowles, H.; Triggs, D.; Talgo, J.; Gandhi, N.; Gutierrez, S.; Aalami, O. Reliability and repeatability of a smartphone-based 6-min walk test as a patient-centred outcome measure. EUROPEAN HEART JOURNAL - DIGITAL HEALTH 2021, 2 (1), 77–87. [CrossRef]

- Maldaner, N.; Sosnova, M.; am Zeitlberger; Ziga, M.; Gautschi, O. P.; Regli, L.; Weyerbrock, A.; Stienen, M. N.; Int 6WT Study Grp. Evaluation of the 6-minute walking test as a smartphone app-based self-measurement of objective functional impairment in patients with lumbar degenerative disc disease. JOURNAL OF NEUROSURGERY-SPINE 2020, 33 (6), 779–788. [CrossRef]

- Marom, P.; Brik, M.; Agay, N.; Dankner, R.; Katzir, Z.; Keshet, N.; Doron, D. The Reliability and Validity of the OneStep Smartphone Application for Gait Analysis among Patients Undergoing Rehabilitation for Unilateral Lower Limb Disability. Sensors 2024, 24 (11). [CrossRef]

- Pepa, L.; Verdini, F.; Capecci, M.; Maracci, F.; Ceravolo, M. G.; Leo, T. Predicting Freezing of Gait in Parkinson’s Disease with a Smartphone: Comparison Between Two Algorithms. Ambient Assisted Living 2015, 11, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepa, L.; Capecci, M.; Andrenelli, E.; Ciabattoni, L.; Spalazzi, L.; Ceravolo, M. G. A fuzzy logic system for the home assessment of freezing of gait in subjects with Parkinsons disease. EXPERT SYSTEMS WITH APPLICATIONS 2020, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polese, J. C.; E Faria, G. S.; Ribeiro-Samora, G. A.; Lima, L. P.; Coelho de Morais Faria, Christina Danielli; Scianni, A. A.; Teixeira-Salmela, L. F. Google fit smartphone application or Gt3X Actigraph: Which is better for detecting the stepping activity of individuals with stroke? A validity study. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2019, 23 (3), 461–465. [CrossRef]

- Regev, K.; Eren, N.; Yekutieli, Z.; Karlinski, K.; Massri, A.; Vigiser, I.; Kolb, H.; Piura, Y.; Karni, A. Smartphone-based gait assessment for multiple sclerosis. Multiple sclerosis and related disorders 2024, 82, 105394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra-Añó, P.; Pedrero-Sánchez, J. F.; Inglés, M.; Aguilar-Rodríguez, M.; Vargas-Villanueva, I.; López-Pascual, J. Assessment of Functional Activities in Individuals with Parkinson's Disease Using a Simple and Reliable Smartphone-Based Procedure. International journal of environmental research and public health 2020, 17(11), 4123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shema-Shiratzky, S.; Beer, Y.; Mor, A.; Elbaz, A. Smartphone-based inertial sensors technology - Validation of a new application to measure spatiotemporal gait metrics. Gait & posture 2022, 93, 102–106. [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Zhang, H.; Kong, L. W.; Sun, Y.; Zhao, J. Validation of gait analysis using smartphones: Reliability and validity. DIGITAL HEALTH 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, S. R.; Gregersen, R. R.; Henriksen, L.; Hauge, E.-M.; Keller, K. K. Wag. Sensors 2022, 22(23), 9396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahalom, H.; Israeli-Korn, S.; Linder, M.; Yekutieli, Z.; Karlinsky, K. T.; Rubel, Y.; Livneh, V.; Fay-Karmon, T.; Hassin-Baer, S.; Yahalom, G. Psychiatric Patients on Neuroleptics: Evaluation of Parkinsonism and Quantified Assessment of Gait. CLINICAL NEUROPHARMACOLOGY 2020, 43(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahalom, G.; Yekutieli, Z.; Israeli-Korn, S.; Elincx-Benizri, S.; Livneh, V.; Fay-Karmon, T.; Tchelet, K.; Rubel, Y.; Hassin-Baer, S. Smartphone-Based Timed Up and Go Test Can Identify Postural Instability in Parkinson's Disease. ISRAEL MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL 2020, 22(1), 37–42. [Google Scholar]

- Abujrida, H.; Agu, E.; Pahlavan, K. Machine learning-based motor assessment of Parkinson's disease using postural sway, gait and lifestyle features on crowdsourced smartphone data. BIOMEDICAL PHYSICS & ENGINEERING EXPRESS 2020, 6 (3). [CrossRef]

- Arora, S.; Baig, F.; Lo, C.; Barber, T. R.; Lawton, M. A.; Zhan, A. D.; Rolinski, M.; Ruffmann, C.; Klein, J. C.; Rumbold, J.; Louvel, A.; Zaiwalla, Z.; Lennox, G.; Quinnell, T.; Dennis, G.; Wade-Martins, R.; Ben-Shlomo, Y.; Little, M. A.; Hu, M. T. Smartphone motor testing to distinguish idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder, controls, and PD. NEUROLOGY 2018, 91(16), 1528–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourke, A. K.; Scotland, A.; Lipsmeier, F.; Gossens, C.; Lindemann, M. Gait Characteristics Harvested during a Smartphone-Based Self-Administered 2-Minute Walk Test in People with Multiple Sclerosis: Test-Retest Reliability and Minimum Detectable Change. Sensors 2020, 20 (20). [CrossRef]

- Chen, O. Y.; Lipsmeier, F.; Phan, H.; Prince, J.; Taylor, K. I.; Gossens, C.; Lindemann, M.; Vos, M. de. Building a Machine-Learning Framework to Remotely Assess Parkinson's Disease Using Smartphones. IEEE TRANSACTIONS ON BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING 2020, 67(12), 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creagh, A. P.; Dondelinger, F.; Lipsmeier, F.; Lindemann, M.; Vos, M. de. Longitudinal Trend Monitoring of Multiple Sclerosis Ambulation Using Smartphones. IEEE OPEN JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING IN MEDICINE AND BIOLOGY 2022, 3, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creagh, A. P.; Simillion, C.; Bourke, A. K.; Scotland, A.; Lipsmeier, F.; Bernasconi, C.; van Beek, J.; Baker, M.; Gossens, C.; Lindemann, M.; Vos, M. de. Smartphone- and Smartwatch-Based Remote Characterisation of Ambulation in Multiple Sclerosis During the Two-Minute Walk Test. IEEE journal of biomedical and health informatics 2021, 25 (3), 838–849. [CrossRef]

- Ginis, P.; Nieuwboer, A.; Dorfman, M.; Ferrari, A.; Gazit, E.; Canning, C. G.; Rocchi, L.; Chiari, L.; Hausdorff, J. M.; Mirelman, A. Feasibility and effects of home-based smartphone-delivered automated feedback training for gait in people with Parkinson's disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2016, 22, 28–34. [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Fortino, G.; Wang, W. Early Detection of Parkinson's Disease Using Deep NeuroEnhanceNet With Smartphone Walking Recordings. IEEE transactions on neural systems and rehabilitation engineering : a publication of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2024, 32, 3603–3614. [CrossRef]

- Lipsmeier, F.; Taylor, K. I.; Kilchenmann, T.; Wolf, D.; Scotland, A.; Schjodt-Eriksen, J.; Cheng, W.-Y.; Fernandez-Garcia, I.; Siebourg-Polster, J.; Jin, L.; Soto, J.; Verselis, L.; Boess, F.; Koller, M.; Grundman, M.; Monsch, A. U.; Postuma, R. B.; Ghosh, A.; Kremer, T.; Czech, C.; Gossens, C.; Lindemann, M. Evaluation of smartphone-based testing to generate exploratory outcome measures in a phase 1 Parkinson's disease clinical trial. Movement disorders : official journal of the Movement Disorder Society 2018, 33 (8), 1287–1297. [CrossRef]

- Mehrang, S.; Jauhiainen, M.; Pietil, J.; Puustinen, J.; Ruokolainen, J.; Nieminen, H. Identification of Parkinson's Disease Utilizing a Single Self-recorded 20-step Walking Test Acquired by Smartphone's Inertial Measurement Unit. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc 2018, 2018, 2913–2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, P.; Karlen, W. PhoneMD: Learning to Diagnose Parkinson’s Disease from Smartphone Data. AAAI 2019, 33(01), 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pim van Oirschot; Marco Heerings; Karine Wendrich; Bram den Teuling; Frank Dorssers; René van Ee; Marijn Bart Martens; Peter Joseph Jongen. A two-minute walking test with a smartphone app for persons with multiple sclerosis: Validation study, 2021.

- Zhai, Y. Y.; Nasseri, N.; Pöttgen, J.; Gezhelbash, E.; Heesen, C.; Stellmann, J. P. Smartphone Accelerometry: A Smart and Reliable Measurement of Real-Life Physical Activity in Multiple Sclerosis and Healthy Individuals. FRONTIERS IN NEUROLOGY 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goñi, M.; Eickhoff, S. B.; Far, M. S.; Patil, K. R.; Dukart, J. Smartphone-Based Digital Biomarkers for Parkinson's Disease in a Remotely-Administered Setting. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 28361–28384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raknim, P.; Lan, K. C. Gait Monitoring for Early Neurological Disorder Detection Using Sensors in a Smartphone: Validation and a Case Study of Parkinsonism. Telemedicine journal and e-health : the official journal of the American Telemedicine Association 2016, 22 (1), 75–81. [CrossRef]

- Su, D. N.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, F. Z.; Yu, W. T.; Ma, H. Z.; Wang, C. X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, X. M.; Hu, W. L.; Manor, B.; Feng, T.; Zhou, J. H. Simple Smartphone-Based Assessment of Gait Characteristics in Parkinson Disease: Validation Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2021, 9 (2). [CrossRef]

- Lam, K.-H.; Bucur, I. G.; van Oirschot, P.; Graaf, F. de; Strijbis, E.; Uitdehaag, B.; Heskes, T.; Killestein, J.; Groot, V. de. Personalized monitoring of ambulatory function with a smartphone 2-minute walk test in multiple sclerosis. MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS JOURNAL 2023, 29 (4-5), 606–614. [CrossRef]

- Salvi, D.; Poffley, E.; Tarassenko, L.; Orchard, E. App-Based Versus Standard Six-Minute Walk Test in Pulmonary Hypertension: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2021, 9 (6). [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.; Zheng, H.; Wang, H.; Sterritt, R.; Newell, D. Smart mobile phone based gait assessment of patients with low back pain. In 2013 Ninth International Conference on Natural Computation (ICNC); IEEE, 2013, pp 1062–1066. [CrossRef]

- Brinkløv, C. F.; Thorsen, I. K.; Karstoft, K.; Brøns, C.; Valentiner, L.; Langberg, H.; Vaag, A. A.; Nielsen, J. S.; Pedersen, B. K.; Ried-Larsen, M. Criterion validity and reliability of a smartphone delivered sub-maximal fitness test for people with type 2 diabetes. BMC sports science, medicine & rehabilitation 2016, 8, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Rozanski, G.; Putrino, D. Recording context matters: Differences in gait parameters collected by the OneStep smartphone application. CLINICAL BIOMECHANICS 2022, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Participants | Study design | Intended users / Test location | Disease | Mobilephone (App) | Placement | Gait parameters | Reference (system) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Sex | Age | ||||||||

| Abujrida et al., (62) | 152 | m(-)/f(-) | - | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / at home | Parkinson | IPhone (mPower) | Sway area, gait velocity, cadence, step time, step length, step count | - | |

| Adams et al., (37) | 82 | m(46)/f(36) | 63.3 ± 9.4 | Observational study | Parkinson and HC / in clinic & at home | Parkinson | Iphone 10 and Iphone 11 (BrainBaseline™ App) | Hip | Gait speed, step length, stride length | |

| Alexander et al., (38) | 100 | m(30)/f(70) | Median: 53.5 (IQR: 47.8 - 58.0) | Pilot-/Validationstudy | MS-patients / Clinical (Indoor) & Home (Outdoor) | Multiple Sclerosis | Iphone 6s (mSteps App) | Arm | Distance walked | Trundle wheel |

| Arora et al., (29) | 10 | m(7)/f(3) | 65.1 ± 9.80 | Prospektive cohort study | PD-patients / at home | Parkinson | LG Optimus S (Specialized Software) | Hip | - | Modified UPDRS |

| Arora et al., (63) | 334 | m(210)/f(124) | 66.1 ± 9.0 | Prospektive cohort study | PD-patients / at home | Parkinson | LG Optimus S (-) | - | - | Modified UPDRS |

| Balto et al., (39) | 45 | m(-)/f(-) | 46.7 ± 10.0 | Cross-sectional study | MS-patients / laboratory | Multiple Sclerosis | Iphone 5 / Health (Apple), Health Mate (Withings), and Moves (ProtoGeo Oy) | Acceleration, velocity | Digi-Walker SW-200 pedometer (Yamax), UP2 and UP Move (Jawbone), Flex and One (Fitbit) |

|

| Banky et al., (33) | 35 | m(22)/f(13) | 51.2 (19-85) | Observational, criterion-standard comparison study | Neurological patients / rehabilitation center | Neurological conditions | Samsung Galaxy S5 (-) | - | Joint angular velocity | Optitrack 3-D motion analysis |

| Bourke et al., (64) | 51 | m(24)/f(27) | 39.5 ± 7.9 | Cross-sectional study | MS-patients / at home | Multiple Sclerosis | Samsung Galaxy S7 (FLOODLIGHT) | Waist in belt bag or pocket | Spatiotemporal parameters | - |

| Brinkløv et al., (81) | 27 | m(9)/f(18) | 64.2 ± 5.9 | Validation Study | Type 2 diabetes patients / field | Type 2 diabetes | Iphone 5c (InterWalk) | VO2peak estimation, acceleration vector magnitude | Cosmed K4b2 | |

| Brooks et al., (40) | 38 | m(11)/f(27) | 25 - 76 | Validation study | CHF- and pHTN-patients / clinic and home | CHF and pHTN | Iphone 4s (SA-6MWT App) | Pocket or Hip holster | Walking distance, step count | ActiGraph accelerometer |

| Capecci et al., (41) | 20 | m(15)/f(5) | 67.6 ± 9.1 | Controlled Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Iphone 5 (Specialized Software) | Hip joint | Cadence, freezing index, energy index | Videoanalyse |

| Chan et al., (80) | 20 | m(11)/f(9) | 20 - 65 | Observational study | Chronic Low back Pain patients / in clinic | LBP | Iphone 4 (-) | Lower back | Cadence, step length, velocity, stride time | Minimod |

| Chen et al., (65) | 37 | m(-)/f(-) | - | Prospektive cohort study | PD-patients / at home | Parkinson | LG Optimus S (-) | Gait variability | MDS-UPDRS | |

| Cheng et al., (32) | 76 | m(36)/f(40) | 39.5 ± 7.9 | Cross-sectional study | Clinicans and MS-patients | Multiple Sclerosis | Samsung Galaxy S7 | Waist or pocket | Timed 25 Foot Walk | Stopwatch in clinical setting |

| Chien et al., (43) | 20 | m(2)/f(19) | 67.95 ± 7.30 | Observational study | Patients with orthostatic tremor / in clinic | Orthostatic tremor | iPhone 6s (custom app) | Sacrum | Mean frequency of acceleration, walking speed | - |

| Clavijo-Buendía et al., (31) | 30 | m(15)/f(15) | 71.7 ± 5.1 | Observational study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Samsung Galaxy S8 (RUNZI ®App) | Front Thigh | Cadence, step length, step count, gait velocity | - |

| Costa et al., (44) | 55 | m(30)/f(25) | 62.5 ± 14.9 | Observational study | Stroke survivors / laboratory | Stroke | Iphone 6s and S480 Positivo (Google Fit, STEPZ, Pacer) | Paretic/non-paretic hip pocket | Step count | Actual steps (live and video analysis) |

| Creagh et al., (67) | 73 | m(23)/f(50) | Mild 39.3 ± 8.3 / moderate 40.5 ± 6.9 | Observational study | MS-patients / at home | Multiple Sclerosis | Samsung Galaxy S7 (-) | Anterior waist | Step count | - |

| Creagh et al., (66) | 52 mild MS; 21 moderate MS | m(16)/f(36); m(7)/f(14) | 39.3 ± 8.3; 40.4 ± 6.9 | Longitudinal study | MS-patients / at home | Multiple Sclerosis | Samsung Galaxy S7 (Floodlight PoC App) | Pocket or Belt Bag | Only adherence of 2MWT over study duration | Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) |

| Ellis et al., (45) | 12 | m(7)/f(5) | 65.0 ± 8.4 | Validity study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Apple iPod Touch (SmartMOVE) | Torso (Navel) | Step time, step length | Pressure sensor mat (Steplength) Footswitch (Steptime) |

| Ginis et al., (68) | 40 | m(23)/f(17) | 68.6 ± 6.8 | Pilot RCT | PD-patientes / at home | Parkinson | Samsung Galaxy S3 Mini (ABF-gait app and CuPiD) | Pocket (training) and handheld (FOG training) |

Gait speed, stride length, double support time (single and dual task) | PKMAS instrumented walkway |

| Goñi et al., (75) | 610 | m(399)/f(211) | 60.3 ± 8.94 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients and HC / remote, self-administered | Parkinson | x/(mPower app) | - | Average acceleration, number of steps, stride intervall, stride variability |

- |

| Hamy et al., (34) | 399 | m(-)/f(-) | - | Observational study | RA-patients / remote | Rheumatoid arthritis | Iphone (PARADE App) | Step length, step time | GAITRite mat | |

| He et al., (69) | 119 | m(72)/f(47) | 64.1 ± 7.9 | Observational study | Parkinsonpatients / at home | Parkinson | Iphone 4s and newer (NeuroEnhanceNet) | - | - | |

| Isho et al., (46) | 24 | m(12)/f(12) | 71.6 ± 9.7 | Cross-sectional study | Older adults / in clinic | Chronic Stroke | Sony Xperia Ray SO-03C (-) | L3 | Trunk acceleration while gait (anteropsoterior, mediolateral) interstride variability |

- |

| Juen et al., (47) | 28 | m(12)/f(16) | 50 - 89 | Cross-sectional study | Stroke survivors / laboratory | Pulmonary diseases | Samsung Galaxy S5, Ace (MoveSense) | L3 | Walking distance, walking speed (6MWT), step count | Actigraph GT3X |

| Kim et al., (20) | 15 | m(7)/f(8) | - | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / at home | Parkinson | Google Nexus 5 (-) | Waist, pocket, ankle, chest | Freezing index, acceleration signals | Videoanalyse |

| Lam et al., (78) | 94 | m(26)/f(68) | 46.5 ± 10.6 | Longitudinal study | MS-patients and Healthy / remote | Multiple Sclerosis | x/(MS Sherpa App) | - | Walking distance | EDSS, T25FW |

| Lipsmeier et al., (70) | 43 | m(35)/f(8) | 57.5 ± 8.45 | Prospektive cohort study | PD-patients / at home | Parkinson | Samsung Galaxy S3 Mini (Roche PD Mobile App v1) | Pocket or belt pouch | Turn speed, activity ratio, sit-to-stand transitions | MDS-UPDRS |

| Lopez et al., (48) | 10 | m(7)/f(3) | 45 - 65 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patientes / gait lab (MOVISYS) | Parkinson | x/(Listenmee app) | - | Walking speed, stride length, cadence, freezing of gait |

Vicon Motion System |

| Mak et al., (49) | 110 | m(109)/f(1) | 68.9 ± 5.9 | Observational study | Cardiovascular patients, remote and clinical | Cardiovascular disease | Iphone 7 (VascTrac App) | Step count | Clinical Measure "Ground Truth" | |

| Maldaner et al., (50) | 70 | m(43)/f(27) | 55.9 ± 15.4 | Observational study | Lumbar degenerative disc patients / in clinic | Lumbar degenerative disc disease | (6WT App) | - | Walking distance | 6 min walk normdata and Distance Wheel |

| Marom et al., (51) | 28 | m(17)/f(11) | 42.5 ± 15.0 | Cross-sectional study | Rehabilitation patients / in clinic | Unilateral lower limb disability | Xiaomi Redmi Note 8 (OneStep App) | Pockets (front) | Cadence, gait speed, stride length, double support, step length, swing/stance phase |

C-Mill VR+ treadmill (Motek) |

| Mehrang et al., (71) | 616 | m(413)/f(203) | 60.6 ± 10.1 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients and HC / at home | Parkinson | Iphone 4s or newer (mPower App) | Pocket or bag | Cadence, step length | - |

| Omberg et al., (30) | 1414 | m(481)/f(933) | 60 | Observational study - remote cohort study | PD-patients/ at home | Parkinson | x/(mPower) | Average acceleration, jerk | Clinical measures (ObjectivePD substudy) | |

| Pepa et al., (52) | 18 | m(13)/f(5) | 69.0 ± 9.7 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Samsung Galaxy (-) | Step length, step cadence | Videoanalyse | |

| Pepa et al., (53) | 44 | m(-)/f(-) | 68.02 ± 8.3 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic and a home | Parkinson | Iphone 5, Iphone 6s (-) | Hip | Step length, step cadence, freezing index, power index, energy derivative ratio |

Videoanalyse |

| Polese et al., (54) | 37 | m(28)/f(9) | 62 ± 11 | Observational study | Strokepatients / in clinic | Stroke | LG Nexus 5 (Google Fit App) | Paretic lower limb pocket | Step count, walked distance | Actual step count by examiner in videotape |

| Raknim et al., (76) | 17 | m(7)/f(10) | 72.0 ± 6.8 | Longitudinal study | Older adults without neurological diseases | Parkinson | Android Smartphones Google, HTC, Samsung (-) | Cadence, step length | - | |

| Regev et al., (55) | 100 | m(33)/f(67) | 40.8 ± 12.4 | Cross-sectional study | MSpatients / in clinic | Multiple Sclerosis | x/(Mon4t Clinic™ app) | Sternum | 3m/10m TUG time, tandem walk metrics | EDSS, clinical rater |

| Rozanski et al., (82) | 25 | m(12)/f(13) | 63.9 ± 8.4 | Retrospective repeated measures | Patients in rehabilitation program / - | Neurological or musculoskeletal conditions | x/(OneStep) | Left/right front or back pocket | Cadence, velocity, hip range, base width, step and stride lengths, stance and double support times, asymmetries of stance, step length and double support |

- |

| Salvi et al., (79) | 30 | m(11)/f(19) | 50 ± 16.6 | Longitudinal study | PAH-patients / indoor and outdoor | PAH | Android or iPhone (SMWTApp) | - | Walking distance (6MWT) | Observational by physiologists |

| Schwab et al., (72) | 14 | m(-)/f(-) | - | Observational study - remote cohort study | PD-patients / remote at home | Parkinson | x/(mPowerApp) | Tremor, rigidity, freezing of gait, linear and angular acceleration |

- | |

| Serra-Ano et al., (56) | 29 | m(-)/f(-) | 68.9 ± 8.98 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Xiaomi Redmi 4x (FallSkip®) | Waist | - | Videoanalyse |

| Shema-Shiratzky et al., (57) | 72 | m(35)/f(37) | 57.2 ± 1.9 | Cross-sectional study | Patients with muscosceletal pathology / in clinic | Muscosceletal pathology (Knee, Back, Hip, Ankle) | Samsung Galaxy A51 (OneStep App) | Thigh | Gait speed, cadence, steplength, cycle time, single- und double-limb support, stancephase |

The ProtoKinetics Zeno™ Walkway |

| Su et al., (77) | 52 | m(33)/f(19) | 63 ± 10 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | iPhone (-) | Front pocket | Stride time, stride time variability | Mobility lab system |

| Sugimoto et al., (35) | 22 | m(8)/f(14) | 21.5 ± 2.56 | Cross-sectional study | Recurrent Ankle Sprains patients / biomechanics lab | Recurrent Ankle Sprains | Samsung Galaxy Xcover 2 Model GTS7710L (AccWalker) | Thigh | Sagittal-plane thigh angular RoM | 3D motion capture (Qualisys) |

| Tang et al., (36) | 20 | m(11)/f(9) | 73.6 ± 9.1 | Observational study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Sony Xperia XZ F8331 (-) | L2 | Stride time, step time, stance time, swing time, step length, step velocity, freezing of gait |

Xsens MTw Awinda |

| Tao et al., (58) | 35 | m(23)/f(12) | 71.133 ± 8.585 | Cross-sectional study | HC and CSVD patients / laboratory | Cerebral small vessel disease | Iphone 13 (MobileGait app) | Shank, waist | Cadence, stride time, stance phase, swing phase, stance time, stride length, walking speed |

Inertial Measurement Unit (N200, Wheeltec, China) |

| Van Oirschot et al., (73) | 25 | m(15)/f(10) | 40.0 ± 8.0 | Cross-sectional study | MS-patients / at home (outdoor) | Multiple Sclerosis | Android/iOS (MS Sherpa App) | 2 MW distance, walking speed | Distance markers | |

| Wagner et al., (59) | 30 | m(8)/f(22) | 61 (50 - 74) | Validation Study | RA-patients / laboratory | Rheumatoid arthritis | Google Pixel 4, Samsung Galaxy A02 (BeSafe-App) | Waist pouch at right front hip | Step count, walking speed, cadence | Manual step count (100 Steps) |

| Yahalom et al., (60) | 18 | m(10)/f(8) | 50.7 ± 8.8 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | Iphone 6 (EncephaLog) | Sternum | Step length, cadence, mediolateral sway | Videoanalyse |

| Yahalom et al., (61) | 21 with normal pull test, 23 with unnormal pull test |

m(11)/f(10); m(13)/f(10) | 67.3 ± 6.8 / 67.8 ± 6.9 | Cross-sectional study | PD-patients / in clinic | Parkinson | IPhone (-) | Waist | Stride length, cadence, variability | - |

| Zhai et al., (74) | 67 | m(25)/f(42) | 42.9 ± 10.9 | Cross-sectional study | MS-patients / at home | Multiple Sclerosis | Samsung Galaxy S4 mini (-) | - | Mean vector magnitude, variance of vector magnitude steps/min | ActiGraph |

| Reference | Reliability | Validity | Sensitivity | Specificity | Feasibility and Limitations | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abujrida et al., (62) | NP | NP | 96.0% for FoG detection |

98.0% for FoG detection | Yes, but noise in home environment affects data | Machine learning accurately classified PD gait impairments, achieving high accuracy (up to 98%) and AUC values (up to 0.99) |

| Adams et al., (37) | Test –retest (ICC > 0.7) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | NP | NP | Yes | Significant decrease in gait parameters over 12 months |

| Alexander et al., (38) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (95% LOA with-in ± 5 m) |

NP | NP | Yes, but GPS accuracy and signal only outdoor | Outdoor GPS from mSteps showed acceptable agreement with the trundle wheel for the MS cohort. Indoor measurements showed high variability. |

| Arora et al., (29) | NP | NP | 96.2% for PD discrimination | 96.9% for PD discrimination | Yes | Demonstrated excellent discrimination between PD and HC using gait metrics. |

| Arora et al., (63) | NP | NP | 91.9% for PD vs control | 90.1% for PD vs control | Yes | Smartphones distinguished PD and controls with high accuracy; gait and balance were effective markers. |

| Balto et al., (39) | NP | No significant correlation was found between smartphone applications (Health, Health Mate, Moves) and walking speed (p > 0.05) (12) |

NP | NP | Yes | Smartphone applications lacked the required accuracy and precision for step measurement, making them unsuitable for use in clinical research settings. (12) |

| Banky et al., (33) | Test-retest (ICC Absolute = 0.21 - 0.93; ICC Relative: 0.40 - 0.99) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Spearman r ≥ 0.80 for 74.8% of parameters) |

NP | NP | Yes, but limited with knee data | Smartphone application showed excellent validity (ICC > 0.8) for velocity, but poor accuracy for the knee. |

| Bourke et al., (64) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.68 - 0.95 for temporal gait parameters; ICC = 0.53 - 0.96 for spatiotemporal, spatial gait parameters) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | NP | NP | Yes | A single smartphone offers precise and reliable measurements of specific spatial, temporal, and spatiotemporal parameters during a self-administered 2-Minute Walk Test (2MWT). (12) |

| Brinkløv et al., (81) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.85 - 0.86) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r2 = 0.45 - 0.60) |

98% | 77% | Yes, but smartphone placement affects validity; jackets induce higher measurement error |

High reliability and validity for VO2-peak prediction with placement in pants. Sensitivity higher than specificity for risk stratification. |

| Brooks et al., (40) | Test-retest (r = 0.94) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.89; CI = 0.78–0.99) |

94% | NP | Yes, but limited to iOS devices | High correlation between app-estimated and in-clinic measured distances (ICC = 0.85 – 0.89). Repeatable at-home results (CoV = 4.6%). |

| Capecci et al., (41) | Test-retest NP Inter/intra-rater reliability (ICC > 0.80) |

NP | 70.1% (Algorithmus 1) 87.57% (Algorithmus 2) |

84.1% (Algorithm 1) 94.97% (Algorithm 2) |

Yes, but only in a clinical setting | Algorithm 2 showed significantly higher sensitivity and specificity than Algorithm 1 |

| Chan et al., (80) | Test-retest (ICC > 0.4) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | NP | NP | Yes | The results showed smart phones are feasible for gait tele-monitoring, with potential as prognostic and treatment outcome tools. |

| Chen et al., (65) | Test-retest NP Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.54. p < 0.001 for PD severity assessment vs MDS-UPDRS) |

97.3% for PD severity discrimination | 97.1% for PD severity discrimination | Yes, but requires consistent training and device management | The framework achieved high accuracy and robustness in PD/HC classification and severity estimation |

| Cheng et al., (32) | Test-retest ICC = 0.87 (0.8 - 0.92) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Correlation between turn speed at 5UTT and T25FW (r=0.5, p < 0.001) |

NP | NP | Yes | A smartphone-based sensor measure for turn speed shows consistent reliability and concurrent validity in evaluating gait and balance impairments in people with Multiple Sclerosis |

| Chien et al., (43) | Test-retest NP Inter/intra-rater reliability (ICC = 0.84–0.92 for mean frequency of acceleration measures (intra-group)) |

NP | NP | NP | Yes, but limited sample size | Significant mean frequency of acceleration differences between OT patients and controls indicate balance and gait instability in OT. |

| Clavijo-Buendía et al., (31) | Test –retest (ICC = good - excellent) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Construct (convergent) (r = 0.424 - 0.957) |

NP | NP | Yes | Moderate to excellent correlation with 10-MWT, good to excellent test-retest reliability for RUNZI® parameters |

| Costa et al., (44) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.99 for actual steps; ICC = 0.80 for Pacer iPhone; ICC = 0.68 for Pacer Android; ICC = 0.28 for STEPZ iPhone; ICC = 0.20 for STEPZ Android; ICC = -0.70 for Health iPhone; ICC = 0.10 for Health Android) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.18 for Health Iphone, p = 0.21) (r = 0.80 for Pacer Iphone, p < 0.01) (r = 0.65 for STEPZ Iphone, p < 0.01) (r = 0.19 for Health Android, p = 0.19) (r = 0.30 for STEPZ Android, p < 0.05) (r = 0.68 for Pacer Android, p < 0.01) |

NP | NP | Yes | Pacer (iPhone) showed the highest validity (r = 0.80, p < 0.01) and reliability (ICC = 0.80). |

| Creagh et al., (67) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.91 for Step number; r = 0.47 - 0.52 for T25FW p < 0.01) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | 67.5 % for mild MS 80.1 % for moderat MS 75.7 for mild vs moderat MS |

60.3 % for mild MS 87.2 % for moderat MS 87.8 for mild vs moderat MS |

Yes, but inconsistent device placement significantly impacts measurement accuracy |

Models utilizing smartphone features demonstrated superior classification performance, enabling accurate and remote measurements with a single device. These models effectively distinguish gait-related dysfunction in individuals with moderate Multiple Sclerosis from healthy controls and those with mild MS. (12) |

| Creagh et al., (66) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (95% LOA with-in ± 5 m) |

NP | NP | Yes, but e.g., hall length influenced performance | Smartphone-based assessment via DCNN accurately estimated MS-related disability. Severity scores strongly correlated with EDSS, but variability noted due to testing conditions. |

| Ellis et al., (45) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (ANOVA: increased gait variability in PD-patients with medium to large effect sizes) |

NP | NP | Yes, but only in clinical setting | Highlight specific opportunities for smartphone-based gait analysis to serve as an alternative to conventional gait analysis methods (e.g., footswitch systems or sensorembedded walkways) |

| Ginis et al., (68) | Test-retest (ɳ² = 0.29. p < 0.001) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | NP | NP | Yes,but device placement unspecified | CuPiD showed greater improvements in gait speed (9%) and dual-task speed (13.5%) compared to controls (5.2%, 5.8%). |

| Goñi et al., (75) | NP | NP | 3.69% | 99.42% | Yes | Gait metrics provided moderate classification performance between PD and HC. |

| Hamy et al., (34) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.86 - 0.91) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r2 = 0.88, p < 0.001) |

NP | NP | Yes | Smartphone app demonstrated significant alignment with GAITRite measures (step length, step time). |

| He et al., (69) | NP | Yes Content Construct (discrimnativ) (AUC = 0.883) |

FNR = 0.053 | NP | Yes | NeuroEnhanceNet achieved the highest AUC (0.883) and lowest FNR (0.053) for early PD detection. |

| Isho et al., (46) | Test –retest (ICC > 0.531 - 0.900) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | 72.7% | 84.6% | Yes | Interstride variability of mediolateral acceleration is significantly associated with fall history; AUC = 0.745 |

| Juen et al., (47) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (ANOVA: F = 1.114e-4 (S5) and 9.36e-5 (Ace). p < 0.001; no significant differences between MoveSense-App, Actigraph GT3X and „Ground Truth“) |

NP | NP | Yes | Strong alignment with Actigraph GT3X validated by ANOVA. |

| Kim et al., (20) | NP | NP | Waist: 86%. Pocket: 84%. Ankle: 81% | Waist: 91.7%. Pocket: 92.5%. Ankle: 91.5% | Partial, placement consistency critical, noise from loose attachments | Smartphone-based system detected FOG with high accuracy using acceleration and gyroscope data. |

| Lam et al., (78) | Test –retest (ICC = 0.764; 95% CI (0.651 - 0.845)) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Spearmans rank correlation coefficiant: p = -0.43 to -0.64) Construct (convergent) (Mann–Whitney U. p < 0.05 for EDSS groups) |

Moderate to strong correlation with EDSS and T25FW (ρ = -0.43 to -0.64) |

AUC = 0.482 (95% CI [0.333. 0.632]); insufficient for group-level distinction |

Yes, but feasible for self-assessment but dependent on GPS signal quality; adherence decreased over time | Group-level analyses lacked sensitivity to detect clinical changes due to variability, but individual-level curve fitting improved s2MWT reliability, identifying significant changes in walking function. |

| Lipsmeier et al., (70) | Test –retest (ICC = 0.80 for Gait) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | Greater sensitivity than UPDRS | NP | Yes, feasible for home use; adherence of 61% in PD participants; requires patient training |

Smartphone-based assessments demonstrated excellent reliability and validity, detecting subtle PD motor impairments and correlating well with MDS-UPDRS ratings. Gait-related impairments were detected using passive monitoring. |

| Lopez et al., (48) | Test –retest (Wilcoxon, p = 0.0117) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | NP | NP | Yes, but device placement unspecified; limited generalizability due to small sample size |

Gait metrics improved significantly with auditory cues: walking speed (+40.6%), cadence (+30.2%), and stride length (+50.3%) compared to baseline. |

| Mak et al., (49) | Test –retest (Cronbach´s Alpha = 0.74) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Cronbach´s Alpha = 0.99) |

69% | 95% | Yes | High correlation between clinical and remote measurement; reliable for detecting frailty |

| Maldaner et al., (50) | Test –retest (ICC = 0.82; SEM = 58.3 m) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Construct (convergent) (Pearson correlation coefficients: moderate r = -0.31 - -0.42) |

NP | NP | Yes, but only outside for GPS | The smartphone app-based measurement of the 6WT is a convenient, reliable, and valid way to determine objective functional impairment in patients with lumbar degenerative disc disease |

| Marom et al., (51) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.77 - 1) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.65 - 1) |

NP | NP | Yes | The app showed good-to-excellent reliability and moderate-to-excellent validity for all parameters, except step length of impaired leg (poor-to-good). |

| Mehrang et al., (71) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Random forest classifier, accuracy = 70%) |

70% | 70% | Yes | Identification of PD via step parameters with 70% accuracy (random forest classifier) |

| Omberg et al., (30) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.71, p < 1.8×10⁻⁶ with UPDRS) |

NP | NP | Yes | Strong correlation between gait metrics collected remotely and UPDRS; While remote assessment demands careful interpretation of RWD, our findings support smartphones and wearables for objective, personalized disease evaluation |

| Pepa et al., (52) | NP | NP | 85.6% for Algorithm 1 and 2 | 93.4% for Algorithm 1 and 2 | Yes, but requires calibration | Demonstrated high reliability and validity in measuring step length and cadence. |

| Pepa et al., (53) | NP | NP | 84.9% for FoG detection | 95.2% for FoG detection | Yes, but requires calibration | Demonstrated high validity and sensitivity in freezing of gait detection using fuzzy logic algorithms. |

| Polese et al., (54) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (ICC = 0.93; CI: 0.86 - 0.96) (r = 0.89, p < 0.001) |

NP | NP | Yes | Google Fit® application showed excellent agreement (ICC = 0.93) and high correlation with actual step counts. |

| Raknim et al., (76) | NP | NP | 94% | NP | Yes, but only on Android | Applying smartphone sensor data to provide early warnings to potential PD patients Classification of changes in gait pattern with 94% accuracy for PD diagnoses |

| Regev et al., (55) | NP | Yes Content Construct (discriminative) (χ² test, p < 0.05; AUC = 85.65%) |

Sensitivity 75.86% (MS vs. HC. AUC = 85.65%) |

Specificity 76.74% (MS vs. HC. AUC = 85.65%) |

Yes, but feasible in clinical settings; requires standardized tasks; lacks real-world data |

Digital markers differentiated MS patients from HC with AUC = 85.65%; correlations with EDSS (ρ = 0.55–0.65) |

| Rozanski et al., (82) | NP | Yes Construct (discrimnativ) (g = 0.32 - 0.48) |

NP | NP | Yes | Active recordings showed higher stride length, velocity, and lower double support compared to passive recordings. |

| Salvi et al., (79) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.91; SEM = 36.97 m; CoV: 12.45%) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.89, p < 0.001) |

NP | NP | Yes | App measurements strongly correlated with physiologist-observed 6MWD (r = 0.89). ICC for repeatability was 0.91. |

| Schwab et al., (72) | Test –retest NP Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (AUC = 0.85; CI: 0.81 - 0.89) |

43% | 95% | Yes | Smartphone diagnostics achieved AUC of 0.85 with strong predictive performance for gait-based PD diagnosis. |

| Serra-Ano et al., (56) | Test –retest (ICC = 0.89 - 0.92 for gait) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

NP | NP | NP | Yes | Reliable differentiation of postural and gait parameters between PD and HC groups. |

| Shema-Shiratzky et al., (57) | Test –retest (ICC = 0.460 - 0.997) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (95% LOA) |

NP | NP | Partial | High correlation for cadence and gait cycle time (r = 0.996-0.997), moderate correlation for stride length and bipedal support |

| Su et al., (77) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.99, p < 0.001 for stride time. r = 0.98 - 0.99, p < 0.001 for stride time variability) |

NP | NP | Yes | Demonstrated excellent reliability and validity for stride time and stride time variability in PD patients. |

| Sugimoto et al., (35) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Group-by-limb interactions for sagittal-plane ankle kinematics F(1,42) = 63,786 p < 0.01; Group-by-limb interactions for sagittal-plane average thigh angular range-of-motion F(1,42) = 6,166 p < 0.017) |

NP | NP | Yes, but requires specific positioning of the device on the thigh |

AccWalker effectively detected differences in thigh RoM between RAS and healthy controls. |

| Tang et al., (36) | Test-Retest-Reliability (ICC 0.768 - 0.896) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.858) |

90.6% | 94.3% | Yes | High consistency between smartphone and XSens; sensitivity and specificity good for FoG detection |

| Tao et al., (58) | Test-retest: (ICC: Thigh = 0.877–0.999; Waist = 0.784–0.996) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Regression analysis: p > 0.05 for most parameters (low/normal speed); no significant differences between the gait parameters of different gait velocitys) |

NP | NP | Yes | Reliable for healthy individuals and CSVD patients; higher reliability for thigh placement than waist. |

| Van Oirschot et al., (73) | Test-retest (ICC = 0.649) Inter/intra-rater reliability NP |

Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (ICC = 0.82) |

NP | NP | Yes, but GPS accuracy and signal only outdoor | The smartphone-based assessment provided a reliable and valid method for assessing gait speed and distance in persons with MS It enabled remote monitoring and offered a user-friendly solution for capturing real-world functional mobility data |

| Wagner et al., (59) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (Spearman’s rho for Pixel vs. observed steps = 0.141. p = 0.075); (Spearman’s rho for Samsung vs. observed steps = 0.033, p = 0.680) |

NP | NP | Yes, but bad results with low walking speed | Spearman correlations between Pixel and observed steps were weak (rho = 0.141), while Samsung showed minimal correlation (rho = 0.033). Accurate at moderate speeds; challenges at low walking speeds |

| Yahalom et al., (60) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (F = 4.4 - 25.4. p < 0.05 for difference between PD and HC |

NP | NP | Partial, requires controlled clinical setup, potential impact of psychiatric conditions |

Quantitative gait analysis was more sensitive than UPDRS for detecting NIP-related gait impairments. |

| Yahalom et al., (61) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (r = 0.14 - 0.46, p < 0.05 for gait |

NP | NP | Yes, but requires smartphone placement training; accuracy depends on environmental factors |

Reliable and valid for measuring stride length and cadence in PD patients under real-world and clinical conditions. |

| Zhai et al., (74) | NP | Yes Content Criterion (concurrent) (ρ = 0.29, p = 0.022 for step/min) |

57 % for varVM 75 % for steps/min |

84 % for varVM 59 % for steps/min |

Yes | Smartphone-based accelerometry offers a more accurate assessment of mobility and disability in individuals with MS compared to wrist-worn accelerometers. Additionally, smartphones effectively differentiate between individuals with MS, healthy controls, and various stages or conditions of MS. |

| Author | Question/ Objective |

Population | Participation Rate |

Selection/ recruitment |

Exposure and outcome | Timeframe between exposure and outcome |

Sample size |

Levels of exposure |

Exposure measure |

Repeated exposure measurement |

Outcome measure |

Blinding of outcome assessors |

Follow-up rate |

Statistical analyses |

Overall quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abujrida et al., (62) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Adams et al., (37) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Alexander et al., (38) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Fair |

| Arora et al., (29) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Fair |

| Arora et al., (63) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Fair |

| Balto et al., (39) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Banky et al., (33) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Bourke et al., (64) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Brinkløv et al., (81) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Brooks et al., (40) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Capecci et al., (41) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Chan et al., (80) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Chen et al., (65) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Cheng et al., (32) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Chien et al., (43) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Clavijo-Buendía et al., (31) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Costa et al., (44) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Good |

| Creagh et al., (67) | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Creagh et al., (66) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Ellis et al., (45) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Ginis et al., (68) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Goñi et al., (75) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Hamy et al., (34) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| He et al., (69) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Isho et al., (46) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Fair |

| Juen et al., (47) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Kim et al., (20) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Lam et al., (78) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Lipsmeier et al., (70) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Lopez et al., (48) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Good |

| Mak et al., (49) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Maldaner et al., (50) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Marom et al., (51) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Mehrang et al., (71) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Good |

| Omberg et al., (30) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Pepa et al., (52) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Pepa et al., (53) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Polese et al., (54) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Good |

| Raknim et al., (76) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Good |

| Regev et al., (55) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Rozanski et al., (82) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Salvi et al., (79) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Schwab et al., (72) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Serra-Ano et al., (56) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Shema-Shiratzky et al., (57) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Su et al., (77) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Sugimoto et al., (35) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Tang et al., (36) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Tao et al., (58) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Van Oirschot et al., (73) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Wagner et al., (59) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Yahalom et al., (60) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Yahalom et al., (61) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

| Zhai et al., (74) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Good |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).