Submitted:

25 January 2025

Posted:

27 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Analysis of Game Parameters

1.2. Psychological Analysis

1.3. Physiological and Physical Profiles

1.4. Teaching Methodologies

2. Materials and Methods

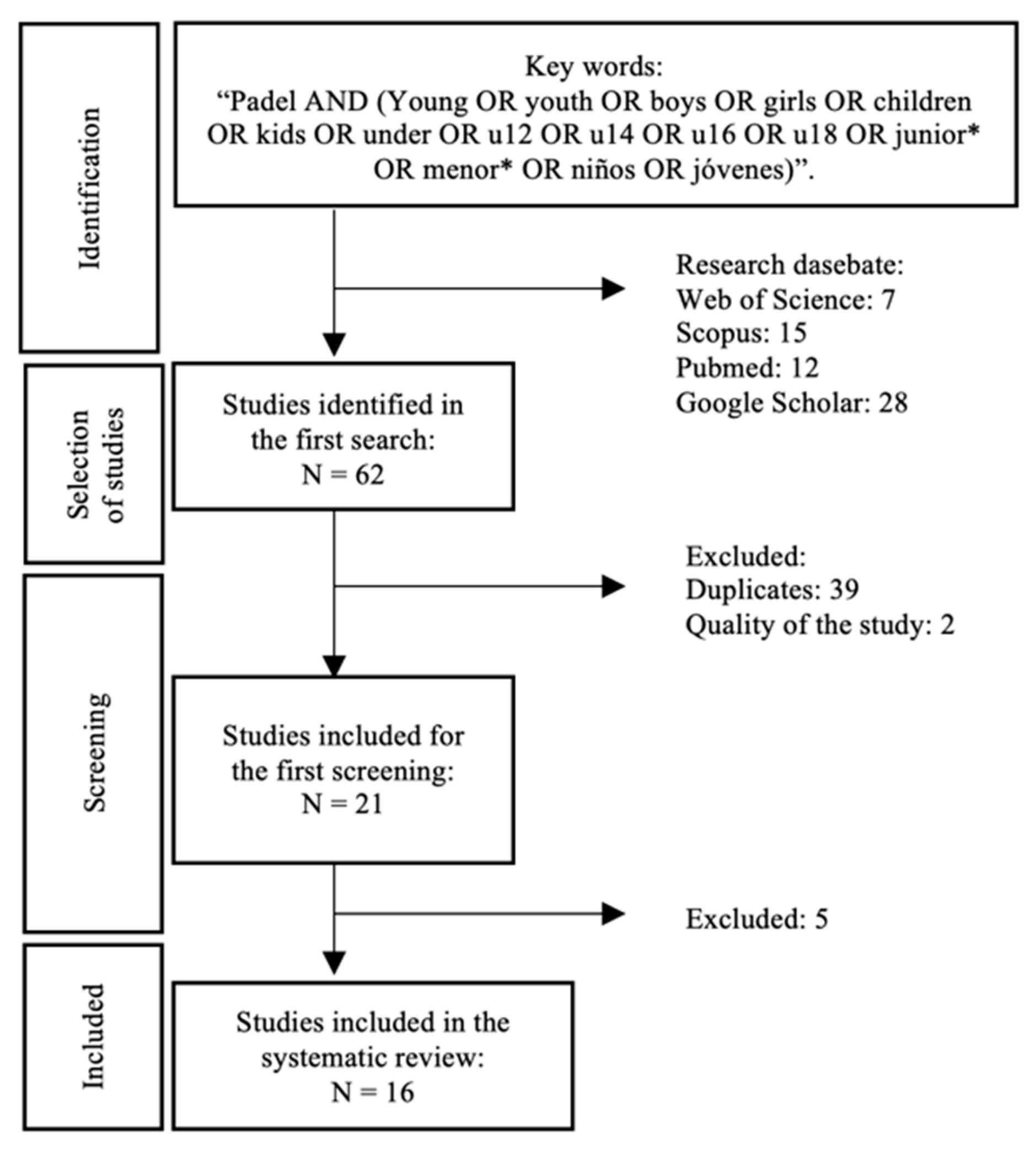

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Identification and Selection of Studies

2.4. Literature Search and Selection

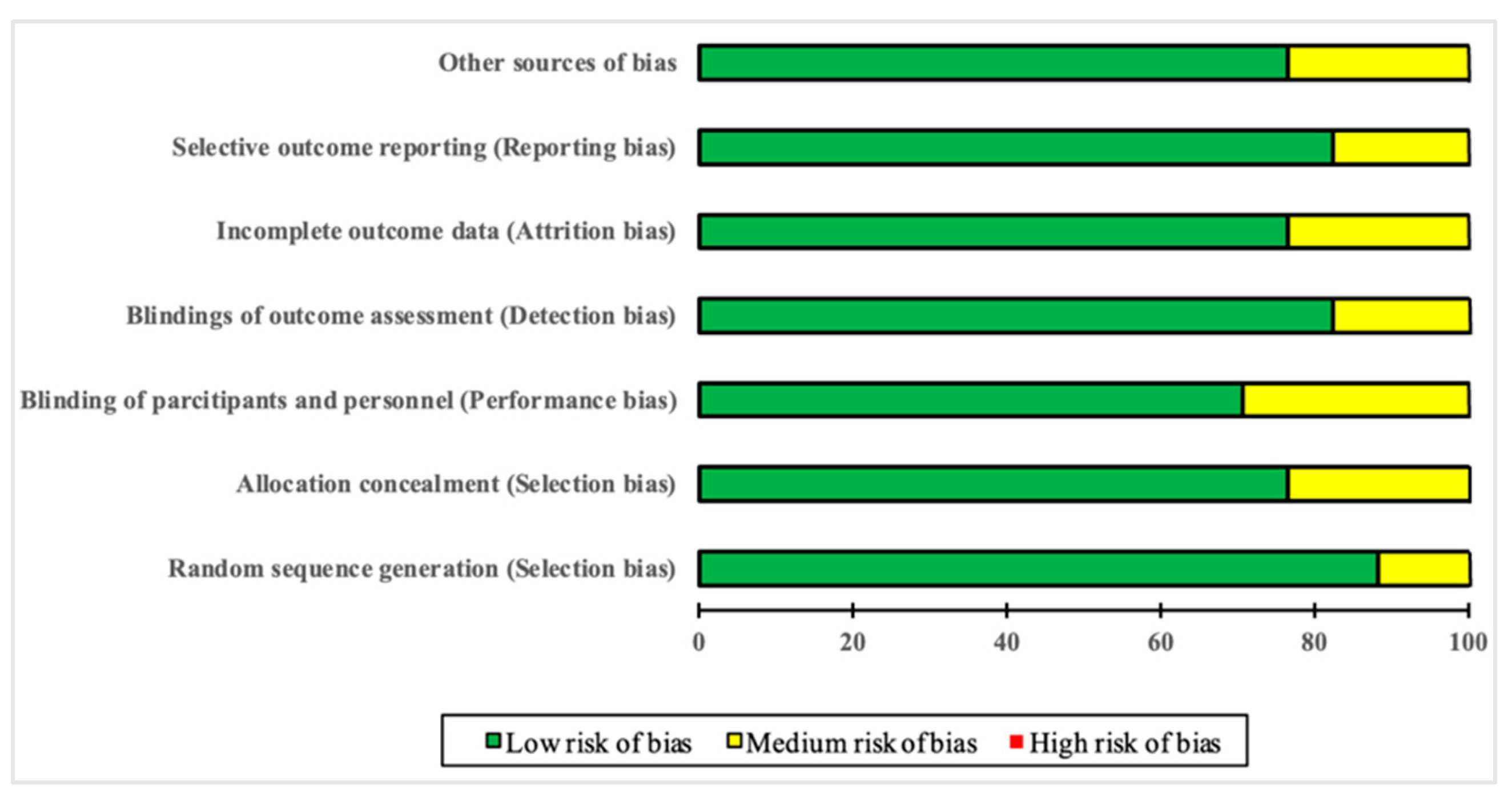

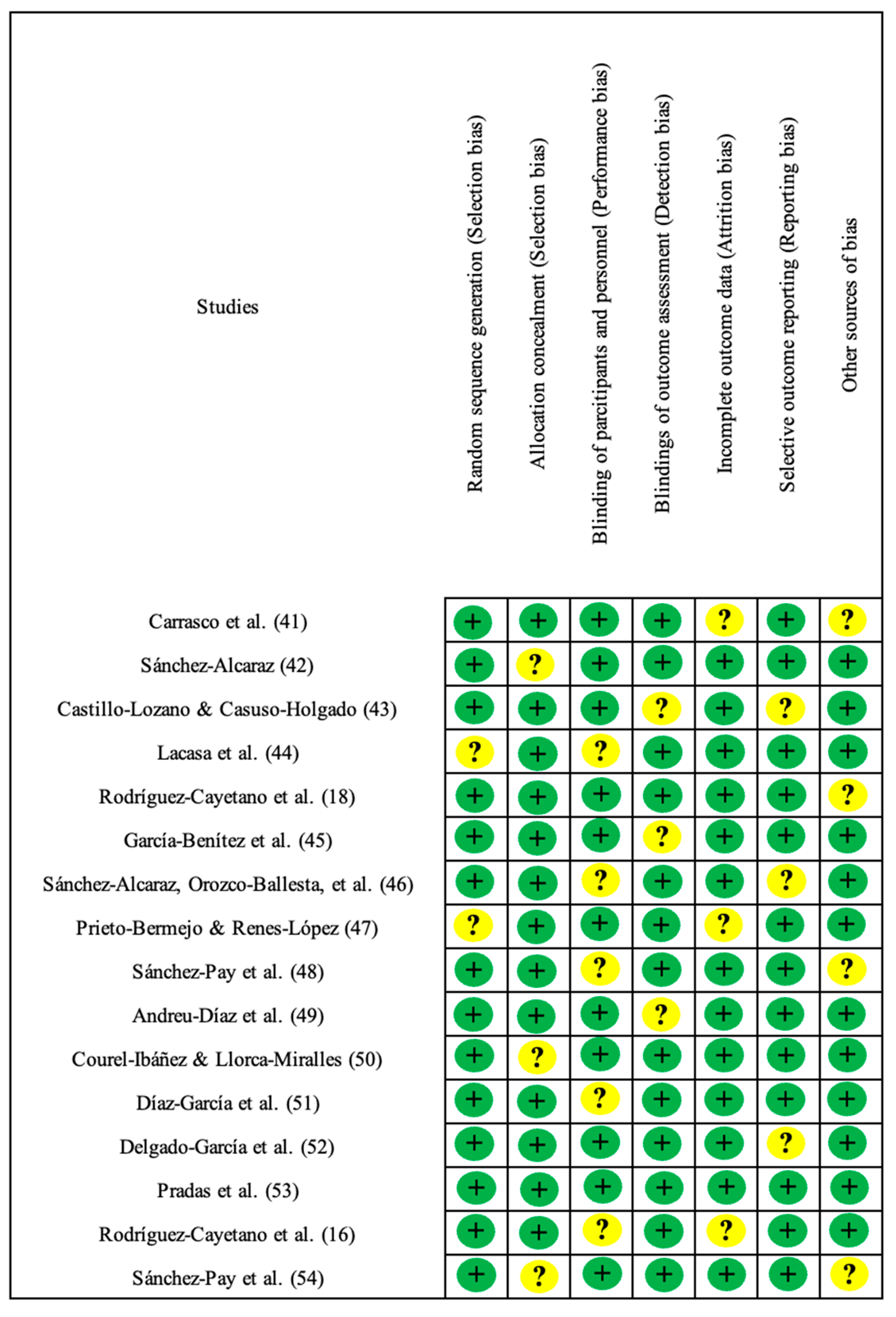

2.5. Risk of Bias in Included Studies

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Teaching Methodologies

4.2. Psychological Characteristics

4.3. Physiological Parameters

4.4. Physical Characteristics

4.5. Health-Related Physical Parameters

4.6. Game Indicators

4.7. Game Parameters

4.8. Study Limitations and Future Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodríguez-Cayetano Pérez-Muñoz, S.; de Mena-Ramos, J.M.; Codón-Beneitez, N.; Sánchez-Muñoz, A. Motivos de participación deportiva y satisfacción intrínseca en jugadores de pádel. Retos 2020, 242–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federación Española de Pádel. Licencias federativas en España. 2024. Available online: https://www.padelfederacion.es/Federaciones (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Cánovas, J.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Muñoz, D. Research in padel. Systematic review. Padel Sci J 2022, 1, 71–105. [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Escudero-Tena, A. Analysis and prediction of unforced errors in men’s and women’s professional padel. Biol Sport. 2024, 41, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Galatti, L.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D.; Ibáñez, S.J. Effect of the golden points and non-golden points on performance parameters in professional padel. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 19, 1314–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Miguel, I.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Performance Analysis in Padel: A Systematic Review. J. Hum. Kinet. 2023, 89, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villena-Serrano, M.; Castro-López, R.; Lara-Sánchez, A.; Cachón-Zagalaz, J. Revisión sistemática de las características e incidencia del pádel en España. Apunts 2016, 1, 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeco, A.; de Sire, A.; Marotta, N.; Spanò, R.; Lippi, L.; Palumbo, A.; Iona, T.; Gramigna, V.; Palermi, S.; Leigheb, M.; et al. Match Analysis, Physical Training, Risk of Injury and Rehabilitation in Padel: Overview of the Literature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, B.J.S.-A.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Cañas, J. Temporal structure, court movements and game actions in padel: A systematic review. Retos 2018, 33, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez-Montoya, D.M.; Pradas, F.; Falcón-Miguel, D.; Ortega-Zayas, M.A. Revisión sistemática de la respuesta fisiológica y metabólica en los deportes de raqueta. Revista internacional de deportes colectivos 2020, 44, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Villena Serrano, M.; Zagalaz Sánchez, M.L.; Castro López, R.; Cachón Zagalaz, J. El pádel. Revisión sistemática de la base de datos TESEO. Sportis Sci J 2017, 30, 375–87. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Jiménez, V.; Muñoz, D. Ramón-Llin. External training load differences between male and female professional padel. J. Sport Health Res 2021, 3, 445–54. [Google Scholar]

- Almonacid, B.; Martínez, J.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Muñoz, D. Volumen e intensidad en pádel profesional masculino y femenino. Rev. Iberoam. De Cienc. De La Act. Fis. Y El Deport. 2023, 12, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escudero-Tena, A.; Almonacid, B.; Martínez, J.; Martínez-Gallego, R.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D. Analysis of finishing actions in men’s and women’s professional padel. Int J Sports Sci Coach 2024, 19, 1384–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, R.; Mellado-Arbelo, O.; Fuentes-García, J.P.; Baiget, E. Game sides technical-tactical differences between professional male padel players. Int. J. Sports Sci. Coach. 2023, 19, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Cayetano, A.; Hernández-Merchán, F.; De Mena-Ramos, J.M.; Sánchez-Muñoz, A.; Pérez-Muñoz, S. Tennis vs padel: Precompetitive anxiety as a function of gender and competitive level. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1018139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, R.H. Sports Psychology: Concepts and Applications, 7th ed.; The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Cayetano Sánchez-Muñoz, A.; De Mena-Ramos, J.M.; Fuentes-Blanco, J.M.; Castaño-Calle, R.; Pérez-Muñoz, S. Pre-competitive anxiety in U12, U14 and U16 paddle tennis players. J Sport Psychol 2017, 26, 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á. Pre and post-competitive anxiety and self-confidence and their relationship with technical-tactical performance in high-level men’s padel players. Front Sports Act Living 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Ripoll, R.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Bustamante-Sánchez, Á. Position and ranking influence in padel: somatic anxiety and self-confidence increase in competition for left-side and higher-ranked players when compared to pressure training. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1393963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robazza, C.; Bortoli, L. Perceived impact of anger and anxiety on sporting performance in rugby players. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2007, 8, 875–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ramiro, E.M.; Rubio-Valdehita, S.; Martín-García, J.; Luceño-Moreno, L. Rendimiento deportivo en jugadoras de élite de hockey hierba: diferencias en ansiedad y estrategias cognitivas. Rev. psicol 2007, 7, 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Baiget, E.; Fernandez-Fernandez, J.; Iglesias, X.; Rodríguez, F.A. Tennis Play Intensity Distribution and Relation with Aerobic Fitness in Competitive Players. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, e0131304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manrique, D.C.; González-Badillo, J.J. Analysis of the characteristics of competitive badminton. Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 62–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramón-Llín, J.; Guzmán, J.F.; Martínez-Gallego, R. Comparison of heartrate between elite and national paddle players during competition. Retos 2018, 33, 91–5. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Otero, T.; Iglesias-Soler, E.; Boullosa, D.A.; Tuimil, J.L. Verification criteria for the determination of VO2max in the field. J Strength Cond Res 2014, 28, 3544–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García, J.D.; Pérez, F.J.G.; Gil, M.C.R.; Mariño, M.M.; Marín, D.M. Estudio de la carga interna en pádel amateur mediante la frecuencia cardíaca. Apunt. Educ. Fis. Y Deport. 2017, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Fuente, F.P.; Zagalaz, J.C.; Benedí, D.O.; Hijós, A.Q.; Castellar, S.I.A.; Otín, C.C. Análisis antropométrico, fisiológico y temporal en jugadoras de pádel de elite (Anthropometric, physiological and temporal analysis in elite female paddle players). Retos Nuevas Tend. Educ. Fís. Deport. Recreación 2015, 1, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Muñoz, D.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Gender Differences in Physical Fitness Characteristics in Professional Padel Players. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Rodríguez, A.; Alvero-Cruz, J.R.; Hernández-Mendo, A.; Fernández-García, J.C. Physical and physiological responses in Paddle Tennis competition. Int J Perform Anal Sport 2014, 14, 524–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, D.; Toro-Román, V.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. La altura como factor de rendimiento en pádel profesional: diferencias entre géneros. Acción motriz 2022, 29, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ibáñez, S.J.; Feu, S.; Cañadas, M.; González-Espinosa, S.; García-Rubio, J. Estudio de los indicadores de rendimiento de aprendizaje tras la implementación de un programa de intervención tradicional y alternativo para la enseñanza del baloncesto. Kronos 2016, 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Viciana, J.; Mayorga-Vega, D. Differences between tactical/technical models of coaching and experience on the instructions given by youth soccer coaches during competition. J Phys Educ Sport 2014, 14, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. La utilización de vídeos didácticos en la enseñanza- aprendizaje de los golpes de pádel en estudiantes. DIM, 2014, 29, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Granados, S.; Latorre-Romero, A.; Lasaga-Rodríguez, M.J. Metodología de enseñanza en pádel en niveles de iniciación. Habilidad Motriz 2010, 34, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lacasa, E. ¿Cuáles son los “principios ignorados” cuando diseño mis entrenamientos de pádel? Padel Sci J 2022, 1, 107–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartwright-Hatton, S.; Roberts, C.; Chitsabesan, P.; Fothergill, C.; Harrington, R. Systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies for childhood and adolescent anxiety disorders. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2004, 43, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.; Watson, R.T. Analyzing the Past to Prepare for the Future: Writing a Literature Review. MIS Quarterly. 2002, 26, xiii–xxiii. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, R.W.; Brand, R.A.; Dunn, W.; Spindler, K.P. How to write a systematic review. In: Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2007. p. 23–9.

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Jüni, P.; Moher, D.; Oxman, A.D.; Savović, J.; Schulz, K.F.; Weeks, L.; Sterne, J.A.C.; et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011, 343, d5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrasco, L.; Romero, S.; Sañudo, B.; de Hoyo, M. Game analysis and energy requirements of paddle tennis competition. Sci. Sports 2011, 26, 338–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Análisis de la exigencia competitiva del pádel en jóvenes jugadores. Kronos 2014, 13, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Lozano, R.; Casuso-Holgado, M. A comparison musculoskeletal injuries among junior and senior paddle-tennis players. Sci. Sports 2015, 30, 268–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacasa, E.; Torrents, C.; Orteu, E.; Gabriel, E.; Hileno, R.; Salas, C. !Profe! ¿Montamos el campo de Mini-Pádel? Los small sided games como medio de iniciación al pádel para niños de 6 a 10 años. Courel J, Cañas J, Sánchéz-Alcaraz B, Alarcón R, editors. Vol. III. Madrid: ESM Librería Deportiva; 2016.

- García-Benítez, S.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Pérez-Bilbao, T.; Felipe, J.L. Game Responses During Young Padel Match Play: Age and Sex Comparisons. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2018, 32, 1144–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Orozco-Ballesta, V.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Sánchez-Pay, A. Evaluación de la velocidad, agilidad y fuerza en jóvenes jugadores de pádel. Retos 2018, 34, 263–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto-Bermejo, J.; Renes-López, V.M. Diseño exploratorio y valoración de una metodología de enseñanza mediante la búsqueda frente a una metodología tradicional en jugadores de pádel en formación. Kronos 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Pay, A.; García-Castejón, A.; Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B. INFLUENCE OF LOW-COMPRESSION BALLS IN PADEL INITATION STAGE. Rev. Int. De Med. Y Cienc. De La Act. Fis. Y Del Deport. 2020, 20, 419–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreu-Díaz, M.; Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Estructura temporal y factores técnico-tácticos en el pádel de iniciación. Sportis Sci J 2021, 7, 111–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Courel-Ibáñez, J.; Llorca-Miralles, J. Physical Fitness in Young Padel Players: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díaz-García, J.; López-Gajardo, M.Á.; Ponce-Bordón, J.C.; Pulido, J.J. Is Motivation Associated with Mental Fatigue during Padel Trainings? A Pilot Study. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado-García, G.; Vanrenterghem, J.; Molina-García, P.; Gómez-López, P.; Ocaña-Wilhelmi, F.; Soto-Hermoso, V. Upper Limb Asymmetries In Young Competitive Paddle-Tennis Players. Rev. Int. De Med. Y Cienc. De La Act. Fis. Y Del Deport. 2022, 22, 827–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradas, F.; Toro-Román, V.; Ortega-Zayas, M.Á.; Montoya-Suárez, D.M.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J.; Muñoz, D. Physical Fitness and Upper Limb Asymmetry in Young Padel Players: Differences between Genders and Categories. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 6461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Pay, A.; Sánchez-Jiménez, J.; Escudero-Tena, A.; Muñoz, D.; Martín-Miguel, I.; Sánchez-Alcaraz, B.J. Analysis of the smash in men’s and women’s junior padel. Cult Cienc Depote 2023, 18, 37–45. [Google Scholar]

|

| Nº | Study | Teaching | Psychology | Physiology | Physical characteristics | Gameplay parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carrasco et al. [41] | |||||

| 2 | Sánchez-Alcaraz [42] | |||||

| 3 | Castillo-Lozano & Casuso-Holgado [43] | |||||

| 4 | Lacasa et al. [44] | |||||

| 5 | Rodríguez-Cayetano et al. [18] | |||||

| 6 | García-Benítez et al. [45] | |||||

| 7 | Sánchez-Alcaraz, Orozco-Ballesta, et al. [46] | |||||

| 8 | Prieto-Bermejo & Renes-López [47] | |||||

| 9 | Sánchez-Pay et al. [48] | |||||

| 10 | Andreu-Díaz et al. [49] | |||||

| 11 | Courel-Ibáñez & Llorca-Miralles [50] | |||||

| 12 | Díaz-García et al. [51] | |||||

| 13 | Delgado-García et al. [52] | |||||

| 14 | Pradas et al. [53] | |||||

| 15 | Rodríguez-Cayetano et al. [16] | |||||

| 16 | Sánchez-Pay et al. [54] |

| Nº | Authors | Sample | Variables | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carrasco et al. [41] | 12 advanced-level right-handed boys (16.57±1.51 years; 1.72±0.08 m; 66±11.37 kg; BMI 22.24±2.73 kg/m2). | -Physiological variables: VO2, %VO2max, Max HR, Mean HR, VT2. Measured in laboratory and competition. -Temporal variables: Real game time. Point duration. Pause between points. Game-rest time ratio. -Stroke frequency variables. |

VO2 in competition 24.06±6.95 ml/kg/min. %VO2max 43.73±11.04% in laboratory test. Max HR in laboratory 200.43±15.76 bpm. Max HR in match 169.72±18.41 bpm, 18% lower. Mean HR is 73.99±4.65% of Max HR obtained in the laboratory. VT2 of 52.52±15.50%, indicating moderate intensity in competition. Game time 163.06 s. Real game time 71.43 s. Point duration 7.24 s. Pause between points 9.11 s. Game-rest time ratio 0.97. Volley (25.57%) and smash (12.45%), most used strokes without bounce. Forehand (20.16%), smash (12.45%), and backhand (8.36%), most used strokes with bounce. Lob least used (2.95% without bounce and 1.80% with bounce). |

| 2 | Sánchez-Alcaraz [42] | 16 boys (14.24±1.86 years, 165.46±7.45 cm, and 58.67±8.93 kg). Minimum of 2 years of practice and participation in 10 tournaments per year. First set of 8 matches from the regional junior padel championship. | - Game actions. Total strokes per point, from the left side and from the right side. - Temporal variables. Total game time. Actual playing time. Rest time. Mean duration of each point. Mean duration of pauses between points. - HR. HRavg, HRmin and HRmax. |

Average total game time 1745.21 s (between 17 and 39 minutes). Average rest time 1212.98 s (20.2 minutes). Mean duration of each point 9.23 s. Mean pause time between points 14.12 s. Number of strokes on the right side 3.28. Number of strokes on the left side 3.45. Average total strokes per point 7-9. HRmin 95.45 bpm. HRavg 141.23 bpm. HRmax 175.24 bpm. |

| 3 | Castillo-Lozano & Casuso-Holgado [43] | 30 players, 24 boys and 6 girls (17.5±2.1 years, 1.75±0.89 cm, 70.13±11.1 kg, 22.65±2.63 body mass index). | Percentage of injuries: Head/neck, upper limbs, trunk, and lower limbs. | The most common injuries are low back pain (23.30%). Knee sprain, plantar fascitis, and elbow injuries (10%). Wrist, ankle sprain, shoulder (6.70%). BMI, handedness, and age variables can explain 7.5-18.5% of the injuries. |

| 4 | Lacasa et al. [44] | 8 players (5 boys and 3 girls, aged 7.6±0.7 years). | - Hitting: baseline, wall, net. - Situation A: nine-game match, court size 20x10m. - Situation B: adapted match, court 10x6m, padel length 33cm, soft1 ball. |

Significantly more hits against the wall (8.57±2.22 vs 3±0.82) and at the net (21.25±5.25 vs 5.25±1.26) in the adapted match. More defining shots in the adapted match (3.75±2.06 vs 0.50±1.00) and similar baseline hits in both matches (63.25±9.91 vs 64.75±15.09) were not significant. The adapted match promotes a greater use of wall shots, as well as volleys and lobs. |

| 5 | Rodríguez-Cayetano et al. [18] | 221 players (100 girls, 121 boys). Age categories: U12=93; U14=73; U16=55. | Revised Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2R), Spanish version. 16 items across three subscales: cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence. Measurement on Likert scale. | No differences found in cognitive anxiety (1.97±0.758 vs 1.95±0.681), somatic anxiety (1.44±0.608 vs 1.56±0.631), and self-confidence (3.18±0.642 vs 3.30±0.641) between girls and boys. Differences observed between U12 (1.74±0.736) and U16 (2.20±0.704) in cognitive anxiety. Differences noted between U12 (3.44±0.616) and U14 (3.07±0.608) and U16 (3.15±0.650) in self-confidence. Differences observed between U16 (1.62±0.623) compared to U14 (1.49±0.580) and U12 (1.45±0.651) in somatic anxiety. Self-confidence values (3.24±0.642) were higher than cognitive anxiety (1.96±0.716) and somatic anxiety (1.51±0.622). |

| 6 | García-Benítez et al. [45] | 1670 points from 32 matches in the national youth category. 16 boys and 16 girls U18 (15±1.08 years). | - Sex. - Point duration. - Rest between points. - Strokes per point. - Lobs per point. - Effective playing time. - Work-rest ratio. |

Boys have less total playtime in U16 (29%, 3454.86 s) compared to U18 (34.7%, 3404.742 s). Average of 995 and 1185 strokes per point and 169 and 259 lobs per match in U16, U18 respectively. Point duration between 8.9 and 12.0 s. Rest time of 14.3 and 15.5 s. There are between 6.1 and 8.0 strokes per point. Girls have a total playtime of 32.4% in U16 and 34.8% in U18. There are 986 points per game. Point duration is 11.3 and 11.7 s, rest time of 15.6 and 14.1 s, and between 6.9 and 7.2 strokes per point between U16 and U18 respectively. |

| 7 | Sánchez-Alcaraz, Orozco-Ballesta, et al. [46] | 17 players, 8 boys (14.12±1.24 years) and 9 girls (14.33±1.24 years). Minimum practice of 2 days per week. Minimum participation in 10 tournaments per season. | - Speed of movement. 10 and 20m sprint. - Change of direction speed. Hexagon test. Upper body strength. Medicine ball throw. |

Boys show better 20m sprint times (3.87±0.30 vs 4.29±0.37 s) and medicine ball throw distances (625±9.70 vs 423±6.70 cm) compared to girls. Girls demonstrate better 10m sprint times (2.84±0.17 vs 2.56±0.26 s) and agility (15.39±3.06 vs 14.39±2.32 s). Linear speed and change of direction variables positively correlate with each other. Strength variables correlate negatively with linear speed and change of direction. |

| 8 | Prieto-Bermejo & Renes-López [47] | 45 participants in beginner level (8.62±2.06 years; 21 boys and 24 girls). Experimental group (n=22) and control group (n=23). | -Experimental group (1): Methodology based on exploration, focused on acquiring skills in variable game situations. -Control group (2): Traditional methodology emphasizing repetition of exercises and automation of actions. |

Tests for baseline (pre) and post-training for baseline-to-baseline (group 1 - 5.05 vs 9.73; group 2 - 4.52 vs 5.17) and baseline-to-net (group 1 - 2.86 vs 4.73; group 2 - 3.26 vs 3.96) demonstrate improvements in both groups, with more pronounced improvements in the group using the exploration-based teaching approach. |

| 9 | Sánchez-Pay et al. [48] | 16 players (10 boys and 6 girls) at beginner level (10±0.8 years; 146.0±4.9 cm; 37.4 ± 7.3 kg). They train 2 hours per week with one year of competitive experience. Four matches were played. | -Physiological variables: HRavg, %HRmax. -Psychological variables: Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), Satisfaction questionnaire. -Game variables: Set and point duration. Points per set. Strokes per set and per point. Strokes with bounce and without bounce. -Ball type: Official ball vs low-pressure ball. |

Set duration (24.03±8.38 vs 23.38±5.06 min). Number of points per set (51.75±20.21 vs 48.25±12.55). Number of strokes per set (223.25±91.03 vs 209±51.19). Number of strokes per point (4.31±2.76 vs 4.33±2.61). Strokes with bounce (3.81±2.13 vs 3.86±2.18). Strokes without bounce (1.64±1.20 vs 1.49±0.83). Point duration (8.07±4.79 vs 7.99±4.63). Official ball vs low-pressure ball showed no significant differences. 70% of points were concluded with between 2 and 5 strokes. 30% of points had more than 5 strokes. HRavg and %HRmax were higher in matches with the official ball (145 bpm, 72.5% HRmax) compared to low-pressure balls (140 bpm, 69.9% HRmax). There were no differences in subjective perception of effort. 30% of game time with low-pressure balls and 20% with official balls were in low to very low intensity zones. 12.82 min with normal balls and 10.94 min with low-pressure balls were spent in moderate-intensity zones (65-76% HRmax). Greater enjoyment, comfort, and ease of play were reported with low-pressure balls. |

| 10 | Andreu-Díaz et al. [49] | Eight male beginner players (13.5±1.4 years; 1.51±0.21 m; 46.25±4.51 kg) participated in two matches, totaling 723 strokes (176 points). They have a minimum of one year of training experience, with two hours of training per week. | -Temporal variables: Average point duration. Average rest duration between points. -Game action variables: Number of strokes. Number of points. Type of stroke. Stroke direction. Stroke effectiveness. Court side. |

Strokes per point 4.08±2.73. Strokes per game 25.07±10.69. Strokes per set 242.33±76.14. Strokes per match 363.5±13.5. Points per game 6.07±2.36. Points per set 58.66±10.53. Points per match 88±15. Average duration 7.66 s, constituting 33% of total game time. Rest duration 15.47 s, comprising 67% of total game time. Primary strokes include first serve (18.4%), forehand return (18.2%), forehand (17.8%), and forehand wall (8.9%). The winning pair utilized more backhand volleys (2.3 vs 0.8%) and forehand wall (10.1 vs 7.7%), and less forehand volleys (5.1 vs 6.6%) and forehand (15.8 vs 19.5%) compared to the losing pair. The side of play and stroke direction did not determine the outcome. The winning and losing pairs executed 30.4% and 22.6% more cross-court strokes. The left-side player executed 11% more down the line strokes than the right-side player. The right-side player had 10-16.4% more involvement in both pairs. Errors accounted for 15-19%, and winners for 6.5-7.3%. The side of play did not determine stroke effectiveness. |

| 11 | Courel-Ibáñez & Llorca-Miralles [50] | 34 players (19 boys and 15 girls): 14.6±1.5 years old; 63.4±14.5 kg; height 166.6±9.8 cm; 6.2±2.5 years of experience. Regional category of the Andalusian Padel Federation. | -Sex -Anthropometry -Body composition -Change of direction and agility -Jump and strength test |

Boys have an average height of 172.8 cm, weight of 70.2 kg, 16.1% body fat, and BMI of 23.3. Girls have an average height of 158 cm, weight of 54.7 kg, 24.1% body fat, and BMI of 21.7. Boys’ jump height (CMJ=23.2 cm; Abalakov=27 cm) is higher than girls’ (CMJ=9.9 cm; Abalakov=11.7 cm). Strength values (medicine ball throw dominant hand=4.7-5 m; non-dominant hand=4.8 m; overhead throw=5.2-6 m) and change of direction (padel agility test=18.2-19.4 s; 3x10 m sprint=8.3-8.8 s) show no differences between sexes. |

| 12 | Díaz-García et al. [51] | 36 elite players (22 boys, 17.40±2.16 years old; 14 girls, 17.90±3.21 years old) participated in four matches, two of which had rewards. | -Situational Motivation Scale -Heart Rate Variability -Quantification of Mental Load -Visual Analog Scale -Psychomotor Vigilance Task |

Intrinsic motivation (6.31±1.98 vs 5.17±1.47), external motivation (4.45±1.29 vs 3.86±1.17), mental fatigue (7.08±2.29 vs 5.67±1.28), and mental load (8.67±2.27 vs 6.45±1.49) were higher in matches with rewards compared to matches without rewards. Reaction time (0.49±0.02 vs 0.43±0.02), HRavg (146.19±16.43 vs 137.67±14.89), SDNN (31.21±6.91 vs 38.76±8.82), NN50 (6.52±1.23 vs 10.22±1.78), and %rMSSD (19.48±5.91 vs 22.65±6.98) were higher in matches with rewards compared to matches without rewards. Amotivation (2.21±0.94 vs 2.67±0.98) was lower in matches with rewards compared to matches without rewards. |

| 13 | Delgado-García et al. [52] | 96 players (53 boys and 43 girls) and a control group of 76 alpine skiers (43 boys and 33 girls). | -Lower limb asymmetry variable. -State of maturity. |

There are no lower limb asymmetries observed in padel players, with a measurement of 1.1±0.8%. However, there are upper limb asymmetries observed at 7.2±5%, which are higher compared to the control group, who had values of 1.4±3.2%. There are also no significant differences observed in terms of maturity status between children with negative or positive maturity status. |

| 14 | Pradas et al. [53] | 60 young padel players divided into: U14 (15 boys and 15 girls); U16 (15 boys and 15 girls). | -Physiological variables. VO2max. -Physical variables. SJ. CMJ. Flexibility. Distance covered. Average speed. Asymmetries. |

VO2max in U14 (47.21±4.49 vs 41.29±4.35 mL/kg/min) and U16 (45.70±2.34 vs 39.85±2.73 mL/kg/min) is higher in boys compared to girls. VO2max in absolute terms (U14: 2.57±0.41 vs U16: 2.92±0.34 l/min) also shows higher values in boys compared to girls. Boys demonstrate higher values in jump tests for power in SJ (U14: 1765±414 vs U16: 2388±397 W) and CMJ (U14: 2002±398 vs U16: 2555±382 W), than girls for SJ (U14: 1565±277 vs U16: 1724±246 W) and CMJ (U14: 1741±289 vs U16: 1894±263 W), and for jump height in SJ (U14: 22.9±5.12 vs U16: 25.53±3.85 cm) and CMJ (U14: 25.68±4.75 vs U16: 27,72±3,67 cm), than girls for SJ (U14: 21.22±2.44 vs U16: 21.16±2.41 cm) and CMJ (U14: 23.70±2.52 vs U16: 23.27±2.85 cm). Distance covered in shuttle run tests (U14: 1129±322 vs U16: 1203±160 m) and average speed (U14: 11.37±0.8 vs U16: 11.55±0.40 km/h) are slightly higher in U16 compared to U14 for both sexes. Flexibility measurements indicate higher values in U16 compared to U14 for both boys (U14: 18.91±6.38 vs U16: 25.46±8.94 cm) and girls (U14: 29.31±6.24 vs U16: 32.42±7.85 cm). Upper limb asymmetries are observed but are not significant between U14 (boys: 11.31±5.09% vs girls: 5.82±1.65%) and U16 (boys: 10.86±2.85% vs girls: 6.75±1.42%). There are no asymmetries observed in the lower limb during lateral movement, accelerations, and reaction time tests. Strength values in the dominant and non-dominant hand show similarities across ages but differ between sexes, with higher values observed in boys. |

| 15 | Rodríguez-Cayetano et al. [16] | 423 players (15.40±3.43 years old), including 291 padel (191 boys; 100 girls; 93 U14; 93 U16; 105 senior category) and 132 tennis players (85 boys and 47 girls; 31 U14; 34 U16; 67 senior category). | Revised Competitive State Anxiety Inventory-2 (CSAI-2R), Spanish version. Three subscales: cognitive anxiety, somatic anxiety, and self-confidence. | Higher values of self-confidence (3.25±0.548) compared to cognitive anxiety (2.01±0.679) and somatic anxiety (1.60±0.557) are observed. Boys exhibit self-confidence (3.27±0.54), somatic anxiety (1.69±0.56), and cognitive anxiety (2.04±0.68). Girls demonstrate self-confidence (3.22±0.56), somatic anxiety (1.44±0.52), and cognitive anxiety (1.96±0.67). Somatic anxiety values are significantly higher in boys compared to girls. Boys show higher values in all three variables compared to tennis players. Girls exhibit lower levels of cognitive anxiety and higher levels of self-confidence than in tennis. Self-confidence is higher in U14 (3.44±0.54) compared to U16 (3.27±0.49) and seniors (3.07±0.55). Somatic anxiety is higher in seniors (1.82±0.54) than in U14 (1.44±0.55) and U16 (1.52±0.51). Cognitive anxiety is higher in seniors (2.26±0.69) compared to U14 (1.79±0.70) and U16 (1.96±0.55). There is a positive correlation between cognitive anxiety and somatic anxiety (0.487) and a negative correlation between both (-0.312; -0.254) and self-confidence. |

| 16 | Sánchez-Pay et al. [54] | 175 smashes from six junior national category finals (three male and three female). 12 boys and 12 girls (aged 16-18 years). Top 10 national junior category. | -Sex. -Type of smash. Flat smash. Topspin smash. Bandeja. Off the wall smash. -Direction of shot. -Effectiveness of the smash. |

Bandeja (RTC=13) and topspin smashes (RTC=5.7) are predominantly cross-court. Flat smashes (RTC=19.1) are mainly down the line. Off the wall smash are similar in both directions, but girls tend to execute them more down the line (52.5%), while boys tend to do so more cross-court (65.4%). Flat smashes (RTC = 9.4) and topspin smashes (RTC = 7.1) mainly result in winners. Off the wall smash primarily lead to errors (RTC = 3.1), while bandejas lead to more continuity (RTC = 11.6). Regarding sexes, bandejas (boys (88.5%) and girls (79.3%)) and off the wall smash (boys (80.8%) and girls (61.3%)) promote continuity in the game, as does flat smashes in boys (62.8%) and topspin smashes in girls (54.5%). Flat smashes are often winners for girls (53.3%), while topspin smashes are winners for boys (50.7%) and less often result in continuity (46.3%). Bandejas are the most used shot among girls (44.1%) and boys (43.8%). Girls execute more off the wall smashes (13.8%) and flat smashes (36.5%) compared to boys. Boys perform more topspin smashes (22.6%) than girls. |

| M: Meters; Cm: Centimeter; Kg: Kilograms; Kg/m2: Kilogram per square meter; BMI: Body Mass Index; s: Seconds; Min: Minutes; VO2: Oxygen uptake; %VO2max: Percentage of maximal oxygen consumption; HR: Hear rate; HRmax: Maximum heart rate; %HRmax: Percentage of maximum heart rate; HRavg: Average heart rate; HRmin: Minimum heart rate; bpm: Beats per minute; VT2: Anaerobic ventilatory threshold; %: Percentage; Ml/kg/min: Milliliters per kilogram per minute; P/min: Beats per minute; l*min: Liters per minute; W: Watts; Km/h: Kilometers per hour; SDNN: Standard deviation of normal-to-normal RR intervals; NN50: Number of pairs of successive RR intervals differing by more than 50 ms, divided by the total number of RR intervals; %rMSSD: Square root of the mean of the sum of the squares of differences between adjacent RR intervals; U12: Under 12 years; U14: Under 14 years; U16: Under 16 years; U18: Under 18 years; RPE: Rating of Perceived Exertion; CMJ: Countermovement Jump; SJ: Squat Jump; COD: Change of Direction; RTC: Residual Tipified Corrected. | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).