Highlights

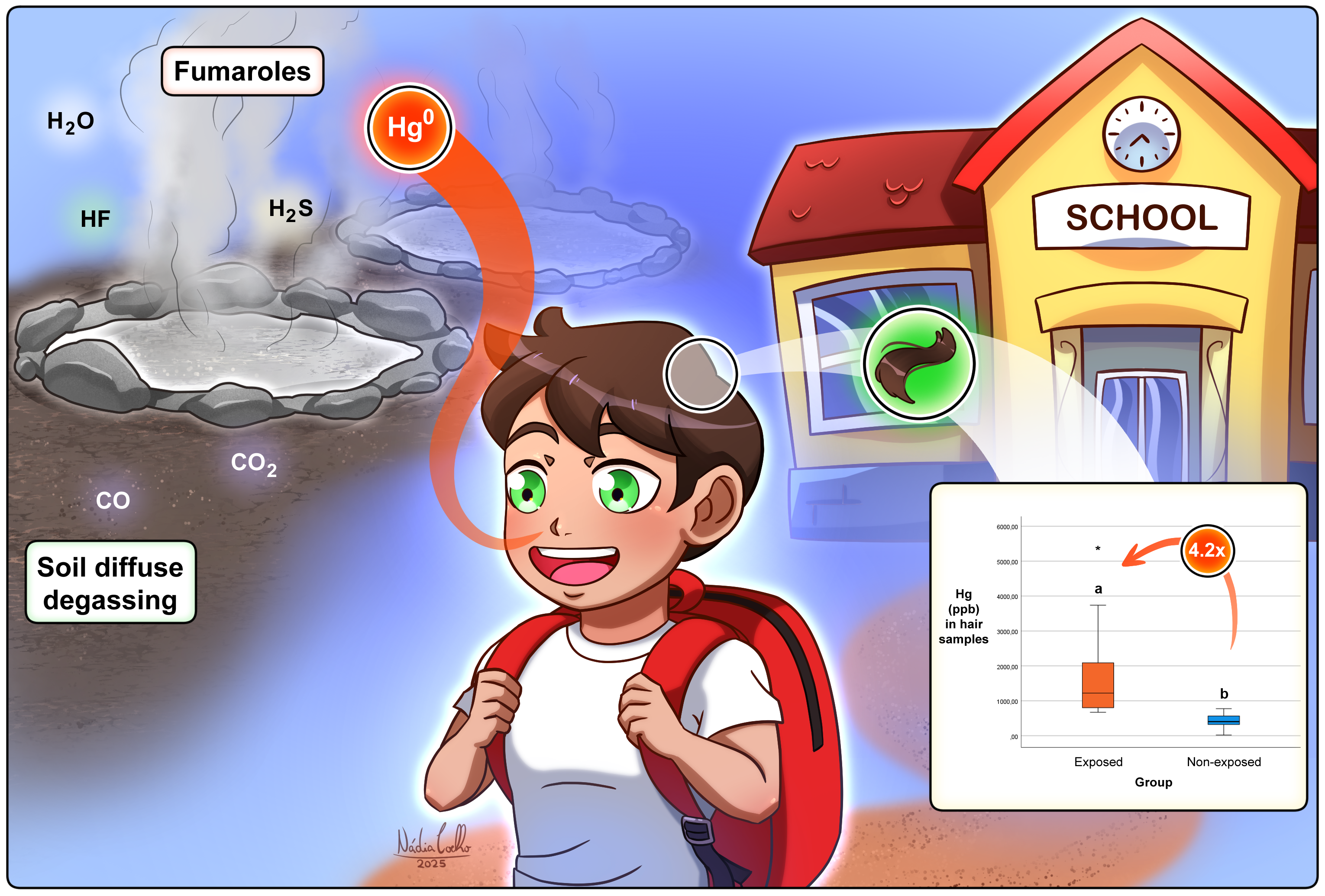

Gaseous elemental mercury (Hg0/GEM) is naturally released in volcanic environments.

People living in volcanically active areas are exposed to low-level doses of Hg0.

Hg0 exposure leads to the bioaccumulation of Hg – which is toxic – in body tissues.

We measured the Hg levels in the hair of children exposed and non-exposed to Hg0.

Exposed children had 4.2 times higher hair Hg levels than non-exposed children.

1. Introduction

Volcanoes are the most prominent sources of natural pollution, being responsible for enriching the environment in hazardous elements. Estimates suggest that more than 14% of world population lives near active volcanoes, unaware of the silent dangers associated with them (Freire et al., 2019; Navarro-Sempere et al., 2023). Volcanogenic events like ash and gas emissions, soil diffuse degassing, pyroclastic and mud flows, including other phenomena, all contribute to the contamination of soils, water, and atmosphere (Zuskin et al., 2007; Calabrese et al., 2015; Torres et al., 2023). Although living in volcanic areas comes with its benefits – like the fertility of soils and geothermal resources –, several of the elements commonly associated with these areas are toxic to living organisms, such as arsenic (As), beryllium (Be), cadmium (Cd), mercury (Hg), lead (Pb), and chromium (Cr) (Tchounwou et al., 2012; Calabrese et al., 2015; Ma et al., 2019; de Carvalho Machado and Dinis-Oliveira, 2023). Gaseous elemental mercury (Hg0 or GEM), which is an atmospheric form of Hg – a heavy metal that is infamous for its neurotoxicity (Branco et al., 2021; Ortega et al., 2023) –, is one of the many gases released in volcanic environments, particularly those of hydrothermal origin (Bagnato et al., 2009; Gagliano et al., 2016; Tassi et al., 2016; Bagnato et al., 2018).

Due to its volatility and chemical inertia, as well as being the dominant form of both natural and anthropogenic Hg emissions (accounting for > 95% of all Hg in the atmosphere), Hg0 is a cause for global concern (Higueras et al., 2014; Cesário et al., 2021; Cabassi et al., 2022). In hydrothermal environments, Hg0 is mostly released into the atmosphere via soil diffuse degassing (Tassi et al., 2016; Bagnato et al., 2018). The volcanic system of Furnas, located in São Miguel Island, Azores Archipelago, Portugal, comprises an area of hydrothermal volcanism in which Hg0 concentrations are below the safety thresholds recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) (WHO, 2000). Because of this, Bagnato et al. (2018) proposed that the levels of Hg0 released from the Furnas Volcano would not pose a hazard towards the populations living in its proximity. However, research with wild mice Mus musculus chronically exposed to the hydrothermal volcanic environment of Furnas showed that inhalation is the primary route of exposure and uptake of Hg0, leading to the formation of Hg deposits in the lungs (Camarinho et al., 2021). Surprisingly, in other studies with M. musculus from Furnas, Hg deposits were also found in blood vessels and the brain, indicating that Hg0 can bypass the blood-brain barrier (Navarro-Sempere et al., 2021b). Further research within the scope demonstrated other alterations regarding M. musculus’ central nervous system (CNS), namely through reactive astrogliosis, astrocyte dysfunction, and neuroinflammation (Navarro et al., 2021; Navarro-Sempere et al., 2021a), but also in their peripheral nervous system (PNS), as seen with a decrease in axon caliber and axonal atrophy along the spinal cord (Navarro-Sempere et al., 2022). Taken together, these studies show that, even at environmental doses considered “safe”, a chronic exposure to Hg0 results in its bioaccumulation in living tissue, paired with a number of adverse effects. Even so, studies addressing human exposure to volcanogenic Hg0 are scarce, hence its risks towards populations living in the proximity of volcanoes are still unknown.

While exposure to neurotoxic substances can prove harmful at any age, children are notably more vulnerable to them. This is because their nervous system is at a sensitive stage of development, which renders them at greater risk of developing structural and functional deficits, including when exposures happen at doses much lower than those known to harm adults (Weiss, 2000; Miodovnik, 2011; Fowler et al., 2023). In children, neurological disorders arising from exposure to neurotoxicants can range from cognitive development delay, to attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism, neurodegenerative disorders, among others (Bose-O’Reilly et al., 2010; Grandjean and Landrigan, 2014; Dórea, 2021; Shabani, 2021).

Several body matrixes, such as blood, saliva, urine, hair, and nails, are often used for human biomonitoring purposes, giving indications about the nutritional status of individuals and exposure to contaminants (Zhou et al., 2016). Hair is a protein component with very low metabolic activity that can indicate the overall load of metals in the body. The elemental profile of this matrix is capable of reflecting long-term exposures, as opposed to urine and blood, which are more appropriate for the assessment of short-term exposures (Solgi and Mahmoudi, 2022). In this sense, hair samples reveal a balance in the body’s mineral content over time, which can only be significantly altered via exposure to or intake of high amounts of trace metals (Amaral et al., 2008).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the level of exposure to Hg0 in children living in a volcanically active environment, using Hg levels in hair samples as exposure biomarkers.

2. Methodology

2.1. Study Sites

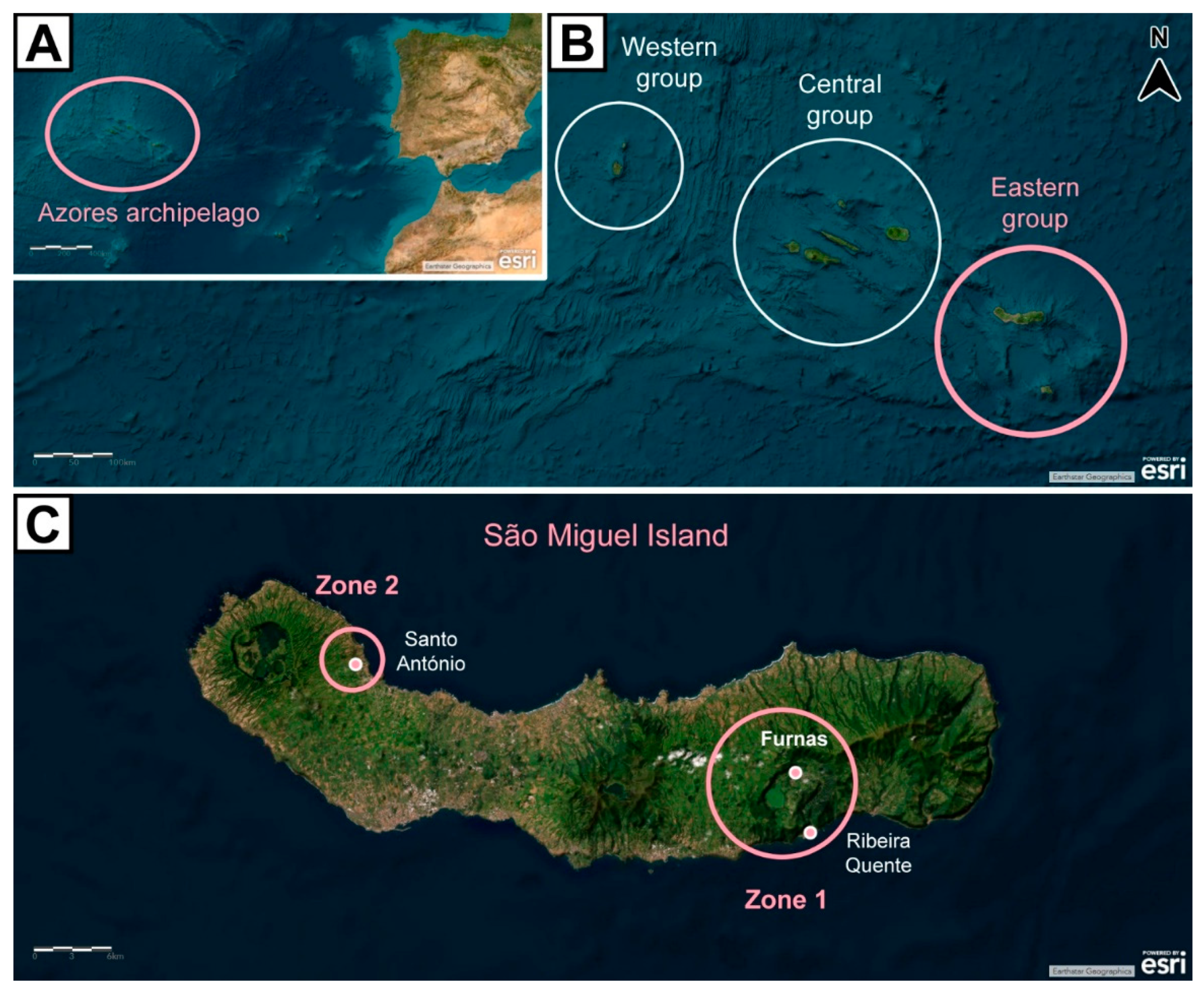

The Azores Archipelago, which comprises 9 islands belonging to Portugal, is an area with active volcanism located in the Atlantic Ocean, somewhere between 36°45’–39°45′N and 24°45’–31°17’W. Its complex tectonic setting – where the Eurasian, African, and American lithospheric plates meet – explains the frequent seismic and volcanic activities recorded (Pacheco et al., 2013) [Figure 1(A and B)]. Volcanogenic events in the area are predominantly hydrothermal, with active fumarolic fields, thermal and cold springs rich in carbon dioxide (CO2), and zones where soil diffuse degassing occurs (Needham and Francheteau, 1974; Viveiros et al., 2010). São Miguel Island, the largest of the Azores Archipelago, is formed by 5 volcanic systems, consisting of 3 active volcanoes (from west to east: Sete Cidades, Fogo, and Furnas), which are linked by 2 rift zones (Picos and Congro) (Guest et al., 1999; Pacheco et al., 2013; Melián et al., 2016).

Figure 1.

Map of the Azores Archipelago showcasing:

(A) its location in the Atlantic Ocean;

(B) its geographical groups;

(C) São Miguel Island and study sites (zone 1 = hydrothermal area, comprising the study group; zone 2 = area without volcanic activity, corresponding to the reference group). Basemap aerial view backgrounds obtained from ESRI ArcGIS online: “World Imagery” [basemap], “World Imagery Map”. Last updated on November, 2024.

https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9. Attribution to ESRI and other data providers is present in the figure.

Figure 1.

Map of the Azores Archipelago showcasing:

(A) its location in the Atlantic Ocean;

(B) its geographical groups;

(C) São Miguel Island and study sites (zone 1 = hydrothermal area, comprising the study group; zone 2 = area without volcanic activity, corresponding to the reference group). Basemap aerial view backgrounds obtained from ESRI ArcGIS online: “World Imagery” [basemap], “World Imagery Map”. Last updated on November, 2024.

https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id=10df2279f9684e4a9f6a7f08febac2a9. Attribution to ESRI and other data providers is present in the figure.

This study was conducted in São Miguel Island, namely in the Furnas and Ribeira Quente Villages – hydrothermal areas, comprising the study group (zone 1) –, and the Santo António Village – an area without records of volcanic activity, corresponding to the reference group (zone 2) [Figure 1 (C)].

The volcanic activity in the Furnas Village is characterized by secondary volcanism manifestations such as fumaroles, thermal and cold CO2-rich springs, and structures of CO2 diffuse degassing. In terms of gases, high amounts of water vapor (H2O), CO2 (≈ 1000 t d−1), and radioactive radon (Rn222) (> 10 Bq m−3) are released, with traces of hydrogen sulfide (H2S), hydrogen (H2), nitrogen (N2), methane (CH4), argon (Ar), helium (He), and carbon monoxide (CO) (Viveiros et al., 2010; Girault et al., 2022). Aside those, Hg0 is essentially released via fumaroles and soil diffuse degassing, with an output of 9.6 × 10−5 t d−1 measured in a study area of 0.04 km2 inside the Furnas Volcano crater. (Bagnato et al., 2018).

Along with the Furnas Village, the Ribeira Quente Village was included as integrating “zone 1” (study group) for this study. This is because, as it is located by the southern flank of the Furnas Volcano, there are several areas in this Village with active volcanism manifestations, namely soil diffuse degassing (Ferreira et al., 2005). In addition, 98% of the houses in this Village were built over the soil diffuse degassing areas (Viveiros et al., 2009; Viveiros et al., 2012).

In contrast with both Furnas and Ribeira Quente, the Santo António Village does not have volcanic activity, marking “zone 2” (reference group) for this study. Although it is geologically represented as the extension of the Sete Cidades volcanic complex, with an area of around 100 km2, it does not contain fumarolic nor diffuse degassing sites, with the exception of the Ponta da Ferraria municipality and the beach of Mosteiros – however, the participants from this Village lived about 40 km away from both of these places, far away from such manifestations (Queiroz, 1997).

2.2. Study Groups

Children from the Furnas, Ribeira Quente, and Santo António Villages, with ages between 6 to 9 years old, were included in this study. An informed consent form was signed by each legal representative of the children involved, authorizing their participation in it. The form contained a description of the procedures regarding hair sample collection and other information gathered. Before work began, clarification sessions were held with the children, along with their legal representatives and teachers, about the objectives of the study.

In total, 21 participants were included in this study, which, based on the zone they lived in, were divided into two groups: one with children inhabiting zone 1 (exposed group, n = 11), and another with children inhabiting zone 2 (non-exposed group, n = 10).

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of the Azores (REF: 7/2023), verifying that the followed procedures safeguard the ethical aspects involved in research.

2.3. Hair Sampling and Hg Level Analysis

Hair samples were collected from each individual for the determination of Hg levels as biomarkers of exposure to Hg0. To eliminate external contamination, each of the hair samples was washed in a sequence of acetone, bi-distilled water, and acetone (Ryabukhin, 1978). After washing, the samples were air-dried at room temperature in a dust-free area. Before analysis, the samples were always kept away from metallic materials and dust to avoid contamination. Next, the samples were cut, homogenized and weighed into microwave digestion vessels 500 mg ± 10 mg. A combination of nitric acid, hydrogen peroxide and hydrochloric acid were added, pretreatment overnight in closed vessels for each batch. The samples were digested and the quantification of Hg (ppb) was achieved via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) following QOP Hydrogeo Rev. 6.6, carried out in a certified and accredited laboratory (ActLabs, Activation Laboratories Ltd., Canada; ISO 9001:2008 and ISO 17025). Triplicate sample digestions and spiked sample were added to each digestion batch. Internal standards and reference materials were run together with the samples for quality control. A minimum of 3 standards were used to cover the analytical working range of the instrument. Ultrapure water was used to prepare calibration standards and blanks.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out in the IBM SPSS Statistics® v. 28.0.1 (142) software. The normality of data regarding the levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples was assessed through Q-Q plots. As data showed a normal distribution, an independent samples t-test was applied to compare the means between groups (preceded by a Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances). Box plots to showcase the differences between groups were made. Differences were considered significant when P < 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

Table 1 shows the results obtained regarding possible differences between the mean levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples per group.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples per group. *t-test, a P value marked in bold indicates significant differences (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of the levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples per group. *t-test, a P value marked in bold indicates significant differences (P < 0.05).

| Variable |

Group |

Minimum |

Maximum |

Mean ± standard error |

P |

| Hg (ppb) in hair samples |

Exposed |

672.65 |

5352.30 |

1797.84 ± 454.92 |

0.005* |

| |

Non-exposed |

19.05 |

775.89 |

430.69 ± 66.43 |

|

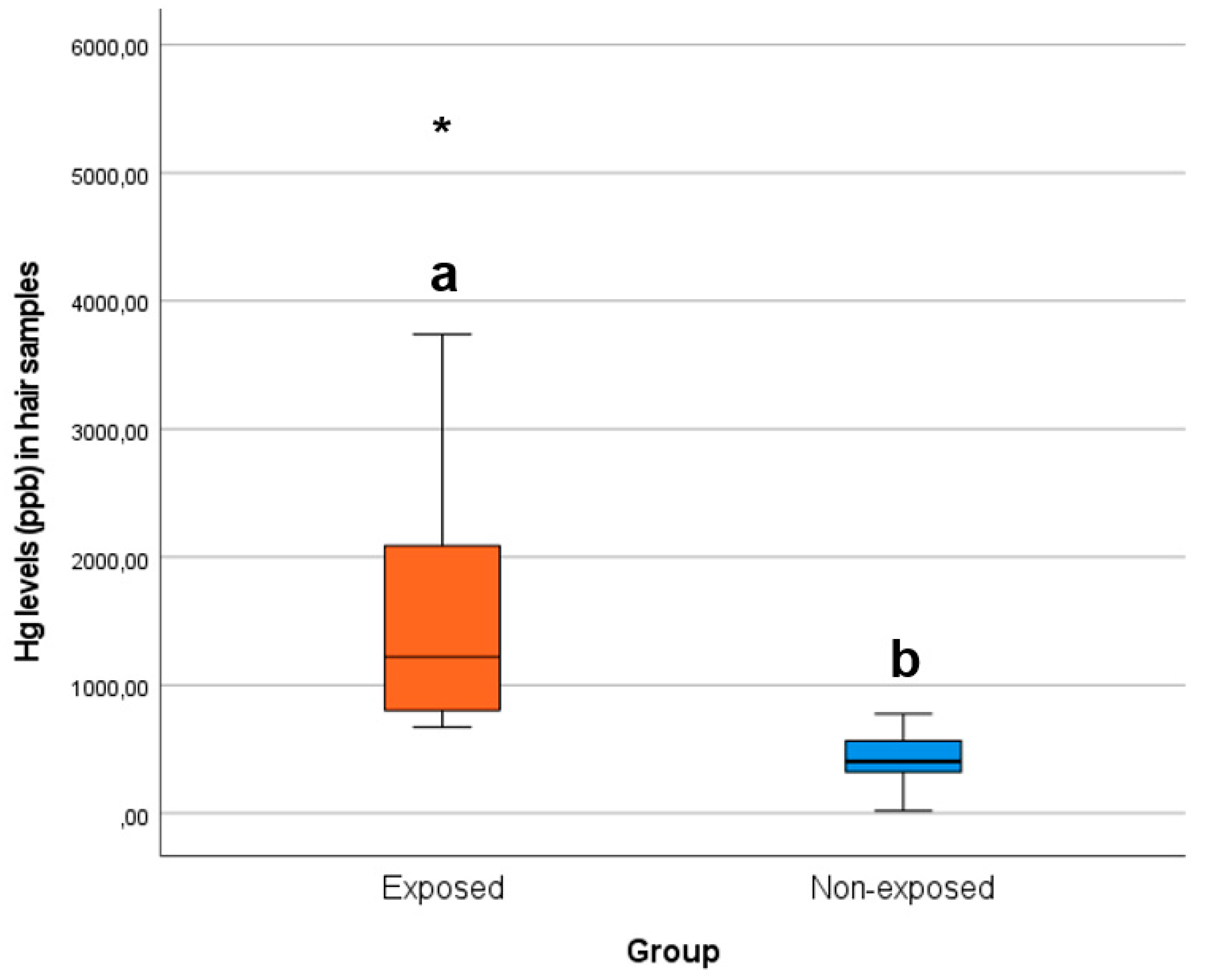

The results displayed in Table 1 allow the perception of how much the mean levels of Hg in children’s hair samples significantly differed between groups: they were 4.2 times higher in the hair of exposed children than that of non-exposed children (≈ 1797.84 ± 454.92 ppb vs. 430.69 ± 66.43 ppb, respectively) (t-test, P < 0.05).

Figure 2 portrays how the data concerning the levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples per group was distributed.

Figure 2.

Box plots of the levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples per group. Different letters (a and b) indicate significant differences (t-test, P < 0.05), an asterisk indicates a group outlier, and the line in the middle of each column represents the median of the respective group.

Figure 2.

Box plots of the levels of Hg (ppb) in children’s hair samples per group. Different letters (a and b) indicate significant differences (t-test, P < 0.05), an asterisk indicates a group outlier, and the line in the middle of each column represents the median of the respective group.

Based on Figure 2, practically all children in the exposed group presented hair Hg levels above the maximum registered in the non-exposed group (775.89 ppb), which were all significantly (t-test, P < 0.05) much higher than in the latter.

The toxicity of Hg is well-documented at high level doses, rendering it infamous for incidents like that of Minamata, Japan, and in Iraq (Takeuchi et al., 2022). It has been associated with neurological disorders primarily affecting the CNS, such as Alzheimer’s disease and multiple sclerosis, but also the PNS, like Parkinson’s disease (Jackson, 2018; Cariccio et al., 2019; Rahman et al., 2020). However, studies addressing low-level exposures to Hg, particularly Hg0, along with its fate and effects, are much fewer. Our results clearly show that although the level exposure to Hg0 in the hydrothermal volcanic environment of Furnas is low, the chronic exposure leads to the bioaccumulation of Hg in the hair of children, so that its concentration in the hair of exposed individuals was 4.2 times higher than in the hair of non-exposed individuals. Although Hg was indeed present in much higher amounts in the hair of exposed children in comparison to non-exposed, little can be told about the consequences of such exposure because not much is known about the effects of volcanogenic Hg0 over the human body. Moreover, when inside the organism, Hg0 suffers modifications – a process called chemical speciation, such as the addition of a methyl (CH3) group –, all with a varying degree of toxicity [for example, methylmercury (MeHg) is considered the deadliest form], hence the true extent of the hazard it poses towards human populations remains unknown (Björkman et al., 2007; Clarkson et al., 2007; Chang and Tjalkens, 2010; Fernandes Azevedo et al., 2012; Gaffney and Marley, 2014). In this sense, and knowing, especially, how vulnerable children are to neurotoxicants, the development of further research within the scope is critical.

In a similar study also developed in Furnas, carried out by Amaral et al. (2008), heavy metals like cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), rubidium (Rb), and zinc (Zn) were found to be present at higher levels in the hair of men living in the Furnas Village, in comparison to men living in an area without active volcanism. Even though the authors did not evaluate Hg levels in the collected hair samples, it’s quite likely that, much like our results showed for children, Hg can equally be found at higher levels in the hair of adults. Later studies in this field of context could include Hg in analyses, as it is a significant toxicant for all age groups.

Some of the available research exploring human low-level Hg exposures highlighting the relationship between hair Hg levels and health outcomes include the works by Yokoo et al. (2003), in Brazil, and Takeuchi et al. (2022), in Japan. Yokoo et al. (2003) conducted the first cross-sectional study addressing human adult exposure to low levels of MeHg, using neuropsychological tests comparable in sensitivity to the methods used in the Faeroes and Seychelles studies. Exposures to Hg in a study population of 129 individuals aged older than 17 were associated with fish consumption, having their hair Hg concentration ranged from 0.56 to 13.6 μg/g, with a mean of 4.2 ± 2.4 μg/g (which is around 4000 ppb) and median of 3.7 μg/g. Hair Hg levels were found to be associated with detectable alterations in performance on tests of fine motor speed and dexterity, and concentration, along with the disruption of some aspects of verbal learning and memory – the magnitude of these alterations increased with hair Hg concentration, which was consistent with a dose-dependent effect. Under a different perspective, the study of Takeuchi et al. (2022) with young adults assessed the effects of Hg levels on brain morphometry using advanced imaging techniques. In a study population of 920 healthy individuals with ages between 18 to 27 years old, exposure to Hg occurred mainly via fish consumption, representing a mean of 2.01 ± 1.15 μg/g in the hair of males and 1.85 ± 1.19 μg/g in the hair of females (around 2000 ppb for both males and females). Such exposure was weakly associated with “(a) lower regional gray matter volume (rGMV) in the left thalamus and left hippocampus, (b) lower regional white matter volume (rWMV) in widespread areas, (c) greater fractional anisotropy (FA) of bilateral white matter tracts, (d) lower mean diffusivity (MD) in widespread areas, particularly bilateral frontal lobe areas and the right basal ganglia, (e) poorer cognitive performance, particularly on tasks requiring cognitive speed, and (f) better mood state (less susceptibility to depressive states)”. Taking in account that exposures to volcanogenic Hg0 also tend to happen at low-level doses, in order to shed light on what happens upon exposures to volcanogenic Hg0, perhaps a similar methodology to that followed by these authors to reach such conclusions could be applied in future human biomonitoring studies. Furthermore, considering that the concentrations of Hg in the hair of individuals from the study developed by Takeuchi et al. (2022) were similar to those observed in our study (a mean of ≈ 2000 ppb vs. 1800 ppb, respectively), and bearing in mind that our study involved children – which, as mentioned, are at greater risk due to being in sensitive neurodevelopmental stages –, these effects may be even more relevant.

Ultimately, the results from this study and discussed former studies support the bioavailability of Hg0 in the environment and how it bioaccumulates in living tissue, even at doses considered within a safe range. Still, given our study was performed with island populations, involved very small localities, and depended on voluntary participation, larger and more representative samples of the general population were difficult to obtain. This made it so that our conclusions might not be as robust as they could have been if a larger number of hair samples were included in this study; nonetheless, our conclusions raise very important concerns. With this in mind, and for future studies, it would be indispensable to look for other volcanically active areas to further biomonitor the levels of Hg in children living in these environments.

Another important remark is that inhaled Hg has a half-life of around 30 to 60 days inside the body, and it is thought to remain in the brain for up to 20 years or more (Park and Zheng, 2012; Rooney, 2014). This means that this gas could not only represent a pressing issue towards the people living in Furnas, but also to populations living in other areas of the world where Hg0 concentrations are deemed below the currently established safety thresholds. On a positive note, studies regarding environmental exposure in the recent years show a trend towards a decrease in the acceptable limits for Hg0 exposure, reflecting an effort in better safeguarding public health within the subject (Ciani et al., 2024).

In essence, given that over 14% of world population lives near active volcanoes, a great amount of people could unknowingly be subjected to the risks of Hg0 exposure and other volcanogenic hazards. After all, more and more evidence suggests that living chronically exposed to volcanic emissions could be as harmful as living in the proximity of industrial facilities (Amaral et al., 2008).

4. Conclusion

Our results showed that the levels of Hg in the hair of children exposed to the hydrothermal volcanic environment of the Furnas Village (São Miguel Island, Azores Archipelago, Portugal) were 4.2 times higher than that of non-exposed children.

In account of both the amount of people living in the proximity of active volcanoes (≈ 14% of world population) and the known risks that Hg poses, emphasis is put on the need of monitoring the health of populations inhabiting volcanically active areas. Moreover, little is still known about the fate, modifications, and effects of Hg0 specifically in the human body, hence the development of further research within the scope is strongly encouraged.

CRediT author statement

Rute Fontes: original research, manuscript revising; Nádia M P Coelho: corresponding author, statistical analysis, writing original manuscript draft, figure editing, illustrating graphical abstract; Patrícia Garcia: experimental design, data processing, manuscript editing and revising; Armindo Rodrigues: experimental design, participation in the sample collection campaign and in the processing of data and writing of the manuscript.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-associated technologies in the writing process

The authors declare that there were no generative AI and AI-associated technologies in the writing process.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Acknowledgments

Teachers and directors of school groups in the Santo António and Furnas Villages.

References

- Amaral, A. F., Arruda, M., Cabral, S., & Rodrigues, A. S. (2008). Essential and non-essential trace metals in scalp hair of men chronically exposed to volcanogenic metals in the Azores, Portugal. Environment International, 34(8), 1104-1108. [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, E., Parello, F., Valenza, M., & Caliro, S. (2009). Mercury content and speciation in the Phlegrean Fields volcanic complex: Evidence from hydrothermal system and fumaroles. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 187(3-4), 250-260. [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, E., Viveiros, F., Pacheco, J. E., D’Agostino, F., Silva, C., & Zanon, V. (2018). Hg and CO2 emissions from soil diffuse degassing and fumaroles at Furnas Volcano (São Miguel Island, Azores): Gas flux and thermal energy output. Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 190, 39-57. [CrossRef]

- Björkman, L., Lundekvam, B. F., Laegreid, T., Bertelsen, B. I., Morild, I., Lilleng, P., Lind, B., Palm, B., & Vahter, M. (2007). Mercury in human brain, blood, muscle and toenails in relation to exposure: An autopsy study. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 6, 30. [CrossRef]

- Bose-O’Reilly, S., McCarty, K. M., Steckling, N., & Lettmeier, B. (2010). Mercury exposure and children’s health. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 40(8), 186-215. [CrossRef]

- Branco, V., Aschner, M., & Carvalho, C. (2021). Neurotoxicity of mercury: An old issue with contemporary significance. Advances in Neurotoxicology, 5, 239-262. [CrossRef]

- Cabassi, J., Lazzaroni, M., Giannini, L., Mariottini, D., Nisi, B., Rappuoli, D., & Vaselli, O. (2022). Continuous and near real-time measurements of gaseous elemental mercury (GEM) from an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: A new approach to investigate the 3D distribution of GEM in the lower atmosphere. Chemosphere, 288(Part 2), 132547. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, S., D’Alessandro, W., Bellomo, S., Brusca, L., Martin, R. S., Saiano, F., & Parello, F. (2015). Characterization of the Etna volcanic emissions through an active biomonitoring technique (moss-bags): Part 1--Major and trace element composition. Chemosphere, 119, 1447-1455. [CrossRef]

- Camarinho, R., Pardo, A. M., Garcia, P. V., & Rodrigues, A. S. (2022). Epithelial morphometric alterations and mucosecretory responses in the nasal cavity of mice chronically exposed to hydrothermal emissions. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 44(8), 2783-2797. [CrossRef]

- Cariccio, V. L., Samà, A., Bramanti, P., & Mazzon, E. (2019). Mercury involvement in neuronal damage and in neurodegenerative diseases. Biological Trace Element Research, 187(2), 341-356. [CrossRef]

- Cesário, R., O’Driscoll, N. J., Justino, S., Wilson, C. E., Monteiro, C. E., Zilhão, H., & Canário, J. (2021). Air concentrations of gaseous elemental mercury and vegetation–air fluxes within saltmarshes of the Tagus estuary, Portugal. Atmosphere, 12(2), 228. [CrossRef]

- Chang, L. W., & Tjalkens, R. B. (2010). 13.28 - Neurotoxicology of metals, in: McQueen, C. A. (Ed.) Comprehensive toxicology (2nd ed.), Elsevier, pp. 483-497. [CrossRef]

- Ciani, F., Costagliola, P., Lattanzi, P., & Rimondi, V. (2024). Gaseous mercury limit values: Definitions, derivation, and the issues related to their application. Sustainability, 16(8), 3142. [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, T. W., Vyas, J. B., & Ballatori, N. (2007). Mechanisms of mercury disposition in the body. American Journal of Industrial Medicine, 50(10), 757-764. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Machado, C., & Dinis-Oliveira, R. J. (2023). Clinical and forensic signs resulting from exposure to heavy metals and other chemical elements of the periodic table. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 12(7), 2591. [CrossRef]

- Dórea, J. G. (2021). Exposure to environmental neurotoxic substances and neurodevelopment in children from Latin America and the Caribbean. Environmental Research, 192, 110199. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes Azevedo, B., Barros Furieri, L., Peçanha, F. M., Wiggers, G. A., Frizera Vassallo, P., Ronacher Simões, M., Fiorim, J., Rossi de Batista, P., Fioresi, M., Rossoni, L., Stefanon, I., Alonso, M. J., Salaices, M., & Valentim Vassallo, D. (2012). Toxic effects of mercury on the cardiovascular and central nervous systems. Journal of Biomedicine & Biotechnology, 2012, 949048. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T., Gaspar, J. L., Viveiros, F., Marcos, M., Faria, C., & Sousa, F. (2005). Monitoring of fumarole discharge and CO2 soil degassing in the Azores: Contribution to volcano surveillance and public health risk assessment. Annals of Geophysics, 48(4-5). [CrossRef]

- Fowler, C. H., Bagdasarov, A., Camacho, N. L., Reuben, A., & Gaffrey, M. S. (2023). Toxicant exposure and the developing brain: A systematic review of the structural and functional MRI literature. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 144, 105006. [CrossRef]

- Freire, S., Florczyk, A., Pesaresi, M., & Sliuzas, R. (2019). An improved global analysis of population distribution in proximity to active volcanoes, 1975-2015. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 8, 341. [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, J. S., & Marley, N. A. (2014). In-depth review of atmospheric mercury: Sources, transformations, and potential sinks. Energy and Emission Control Technologies, 2, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Gagliano, A., Calabrese, S., Daskalopoulou, K., Cabassi, J., Capecchiacci, F., Tassi, F., Bonsignore, M., Sprovieri, M., Kyriakopoulos, K., Bellomo, S., Brusca, L., & D’Alessandro, W. (2016). Mobility of mercury in the volcanic/geothermal area of Nisyros (Greece). Bulletin of the Geological Society of Greece, L, 2118-2126.

- Girault, F., Viveiros, F., Silva, C., Thapa, S., Pacheco, J. E., Adhikari, L. B., Bhattarai, M., Koirala, B. P., Agrinier, P., France-Lanord, C., Zanon, V., Vandemeulebrouck, J., Byrdina, S., & Perrier, F. (2022). Radon signature of CO2 flux constrains the depth of degassing: Furnas Volcano (Azores, Portugal) versus Syabru-Bensi (Nepal Himalayas). Scientific Reports, 12(1), 10837. [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P., & Landrigan, P. J. (2014). Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. The Lancet. Neurology, 13(3), 330-338. [CrossRef]

- Guest, J. E., Gaspar, J. L., Cole, P. D., Queiroz, G., Duncan, A. M., Wallenstein, N., Ferreira, T., Pacheco, J.-M. (1999). Volcanic geology of Furnas Volcano, São Miguel, Azores. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 92(1-2), 1-29. [CrossRef]

- Higueras, P., Oyarzun, R., Kotnik, J. et al. (2014). A compilation of field surveys on gaseous elemental mercury (GEM) from contrasting environmental settings in Europe, South America, South Africa and China: Separating fads from facts. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 36, 713-734. [CrossRef]

- Jackson, A. C. (2018). Chronic neurological disease due to methylmercury poisoning. The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. Le Journal Canadien des Sciences Neurologiques, 45(6), 620-623. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q., Han, L., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Lang, Q., Li, F., Han, A., Bao, Y., Li, K., & Alu, S. (2019). Environmental risk assessment of metals in the volcanic soil of Changbai Mountain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(11), 2047. [CrossRef]

- Melián, G., Somoza, L., Padrón, E., Pérez, N., Hernandez, P., Sumino, H., Forjaz, V-H., França, Z. (2016). Surface CO2 emission and rising bubble plumes from degassing of crater lakes in São Miguel Island, Azores. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 437(1), SP437.14. [CrossRef]

- Miodovnik, A. (2011). Environmental neurotoxicants and developing brain. The Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine, New York, 78(1), 58-77. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, A., García, M., Rodrigues, A. S., Garcia, P. V., Camarinho, R., & Segovia, Y. (2021). Reactive astrogliosis in the dentate gyrus of mice exposed to active volcanic environments. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A, 84(5), 213-226. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sempere, A., García, M., Rodrigues, A. S., Garcia, P. V., Camarinho, R., & Segovia, Y. (2022). Occurrence of volcanogenic inorganic mercury in wild mice spinal cord: Potential health implications. Biological Trace Element Research, 200, 2838-2847 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sempere, A., Martínez-Peinado, P., Rodrigues, A. S., Garcia, P. V., Camarinho, R., Grindlay, G., Gras, L., García, M., & Segovia, Y. (2023). Metallothionein expression in the central nervous system in response to chronic heavy metal exposure: Possible neuroprotective mechanism. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 45(11), 8257-8269. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sempere, A., Martínez-Peinado, P., Rodrigues, A. S., Garcia, P. V., Camarinho, R., García, M., & Segovia, Y. (2021a). The health hazards of volcanoes: First evidence of neuroinflammation in the hippocampus of mice exposed to active volcanic surroundings. Mediators of Inflammation, 2021(1), 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Navarro-Sempere, A., Segovia, Y., Rodrigues, A. S., Garcia, P. V., Camarinho, R., & García, M. (2021b). First record on mercury accumulation in mice brain living in active volcanic environments: A cytochemical approach. Environmental Geochemistry and Health, 43(1), 171-183. [CrossRef]

- Needham, H., & Francheteau, J. (1974). Some characteristics of the rift valley in the Atlantic Ocean near 36º48’ north. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 22(1), 29-43. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, J. M., Ferreira, T., Queiroz, G., Wallenstein, N., Coutinho, R., Cruz, J. V., Pimentel, A., Silva, R., Gaspar, J. L., & Goulart, C. (2013). Notas sobre a geologia do arquipélago dos Açores, in: Dias, R., Araújo, A., Terrinha, P., Kullberg, J. C. (Eds.) Geologia de Portugal, vol. 2, pp. 595-690. Escolar Editora (Lisbon).

- Park, J. D., & Zheng, W. (2012). Human exposure and health effects of inorganic and elemental mercury. Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi, 45(6), 344-352. [CrossRef]

- Queiroz, G. (1997). Vulcão das Sete Cidades (S. Miguel, Açores): História eruptiva e avaliação do hazard. Doctoral dissertation in Geology, specialty in Volcanology, University of the Azores, Department of Geosciences.

- Rahman, M. A., Rahman, M. S., Uddin, M. J., Mamum-Or-Rashid, A. N. M., Pang, M. G., & Rhim, H. (2020). Emerging risk of environmental factors: Insight mechanisms of Alzheimer’s diseases. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 27(36), 44659-44672. [CrossRef]

- Rooney, J. P. (2014). The retention time of inorganic mercury in the brain--A systematic review of the evidence. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 274(3), 425-435. [CrossRef]

- Ryabukhin, Y. S. (1976). Activation analysis of hair as an indicator of contamination of man by environmental trace element pollutants. Vienna: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

- Shabani, S. (2021). A mechanistic view on the neurotoxic effects of air pollution on central nervous system: Risk for autism and neurodegenerative diseases. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 28(6), 6349-6373. [CrossRef]

- Solgi, E., Mahmoudi, S. (2022). Arsenic and heavy metal concentrations in human hair from urban areas. Environmental Health Engineering and Management Journal, 9(3),247-253.

- Takeuchi, H., Shiota, Y., Yaoi, K., Taki, Y., Nouchi, R., Yokoyama, R., Kotozaki, Y., Nakagawa, S., Sekiguchi, A., Iizuka, K., Hanawa, S., Araki, T., Miyauchi, C. M., Sakaki, K., Nozawa, T., Ikeda, S., Yokota, S., Magistro, D., Sassa, Y., & Kawashima, R. (2022). Mercury levels in hair are associated with reduced neurobehavioral performance and altered brain structures in young adults. Communications Biology, 5(1), 529. [CrossRef]

- Tassi, F., Cabassi, J., Calabrese, S., Nisi, B., Venturi, S., Capecchiacci, F., Giannini, L., & Vaselli, O. (2016). Diffuse soil gas emissions of gaseous elemental mercury (GEM) from hydrothermal-volcanic systems: An innovative approach by using the static closed-chamber method. Applied Geochemistry, 66, 234-241. [CrossRef]

- Tchounwou, P. B., Yedjou, C. G., Patlolla, A. K., & Sutton, D. J. (2012). Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Experientia Supplementum (2012), 101, 133-164. [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, F., Cardellini, C., Ferreira, T., & Silva, C. (2012). Contribution of CO2 emitted to the atmosphere by diffuse degassing from volcanoes: The Furnas Volcano case study. International Journal of Global Warming, 4(3-4), 287-304. [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, F., Cardellini, C., Ferreira, T., Caliro, S., Chiodini, G., & Silva, C. (2010). Soil CO2 emissions at Furnas Volcano. São Miguel Island, Azores Archipelago: Volcano monitoring perspectives, geomorphologic studies and land use planning application. Journal of Geophysical Research, 115(B12208), 1-17. [CrossRef]

- Viveiros, F., Ferreira, T., Silva, C., & Gaspar, J. L. (2009). Meteorological factors controlling soil gases and indoor CO2 concentration: A permanent risk in degassing areas. The Science of the Total Environment, 407(4), 1362-72. [CrossRef]

- Weiss, B. (2000). Vulnerability of children and the developing brain to neurotoxic hazards. Environmental Health Perspectives, 108 Suppl 3(Suppl 3), 375-381. [CrossRef]

- WHO (World Health Organization) (2000). Air quality guidelines for Europe (2nd ed.), vol. 91, pp. 157-162. European Series Geneva: WHO Regional Publications.

- Yokoo, E. M., Valente, J. G., Grattan, L., Schmidt, S. L., Platt, I., & Silbergeld, E. K. (2003). Low level methylmercury exposure affects neuropsychological function in adults. Environmental Health: A Global Access Science Source, 2(1), 8. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T., Li, Z., Zhang, F., Jiang, X., Shi, W., Wu, L., & Christie, P. (2016). Concentrations of arsenic, cadmium and lead in human hair and typical foods in eleven Chinese cities. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology, 48, 150-156. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).