Submitted:

15 July 2024

Posted:

16 July 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.1. Sample Analysis

2.2. Comparison Areas

2.3. Analysis of the Incidence of the Population in the Kola North

2.4. Statistical Data Processing

3. Results of the Study

3.1. REE Content in the Children Hair Samples

3.2. Comparing

3.3. Nervous System Diseases

4. Discussion

4.1. Accumulation REE in the Brain

4.2. Nervous System Diseases and RREs

4.2.1. Episodic Paroxysmal Disorders (G40-G47)

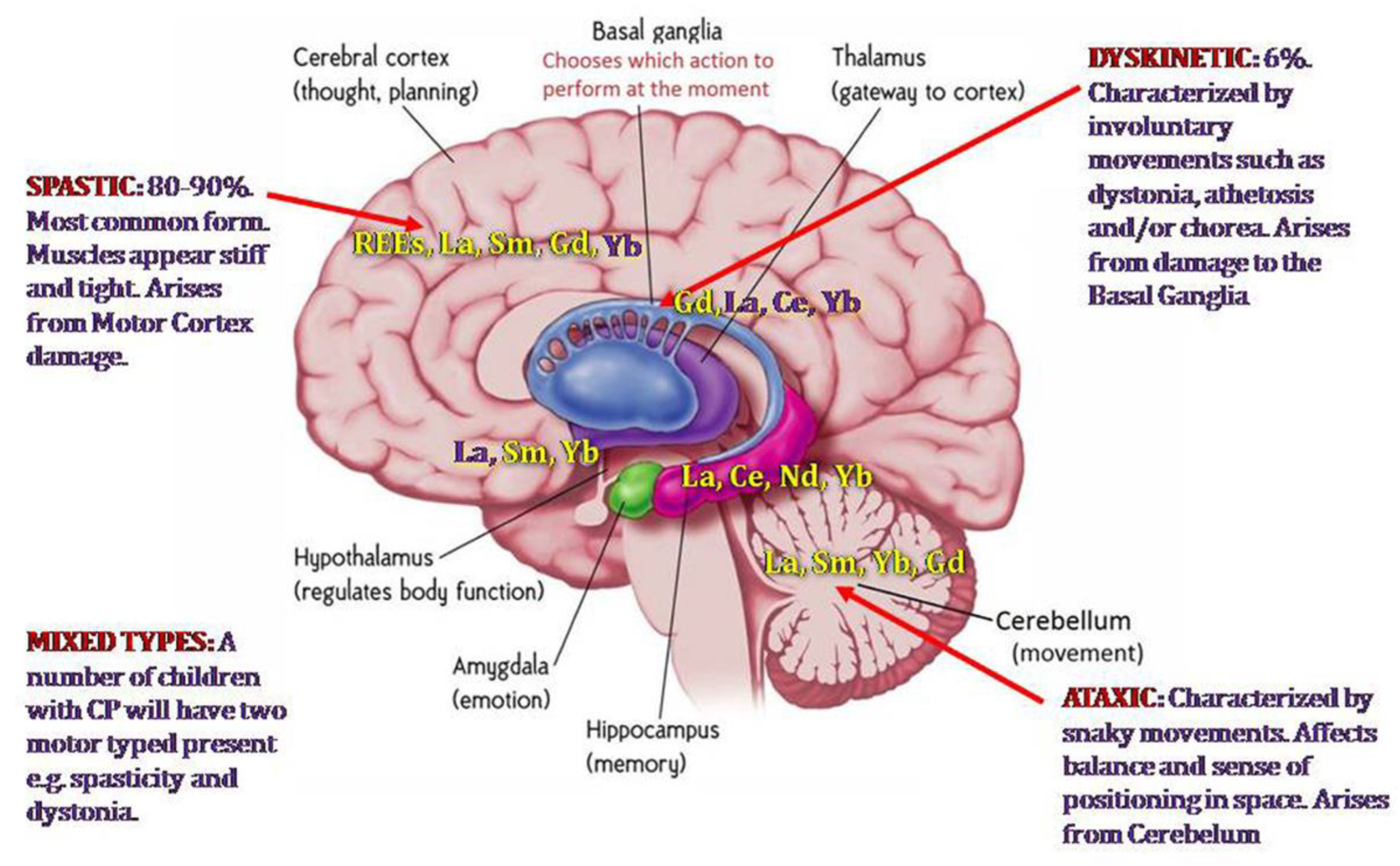

4.2.2. Cerebral Palsy and Other Paralytic Syndromes (G80-G83)

4.2.3. Epilepsy and Status Epilepticus (G40-G41)

5. Conclusion

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.; Yang Y.; Wang D.; Huang L. Toxic Effects of Rare Earth Elements on Human Health: A Review. Toxics. 2024, 12, 5, p.317. PMID: 38787096. [CrossRef]

- Brouziotis, A.A.; Giarra, A.; Libralato, G.; Pagano, G.; Guida, M.; Trifuoggi, M. Toxicity of rare earth elements: An overview on human health impact. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022. 10, p.948041. [CrossRef]

- Balaram V. Rare earth elements: A review of applications, occurrence, exploration, analysis, recycling, and environmental impact. Geoscience Frontiers. 2019, 101285e1303. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liang T, Li K, Wang P. Exposure of children to light rare earth elements through ingestion of various size fractions of road dust in REEs mining areas. Sci Total Environ. 2020, 15, pp.743:140432. Epub 2020 Jun 23. PMID: 32659548. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z. Neurotoxicological evaluation of long-term lanthanum chloride exposure in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2008, 103, 2, pp.354-61. Epub 2008 Mar 3. PMID: 18319242. [CrossRef]

- Rim, K.T.; Koo, K.H.; Park, J.S. Toxicological evaluations of rare earths and their health impacts to workers: A literature review. Saf Health Work. 2013, 4, 1, pp.12-26. Epub 2013 Mar 11. PMID: 23516020; PMCID: PMC3601293. [CrossRef]

- Rim, K.T. Effects of rare earth elements on the environment and human health: A literature review. Toxicol. Environ. Health Sci. 2016, 8, pp. 189–200. [CrossRef]

- Gwenzi, W.; Mangori, L.; Danha, C.; Chaukura, N.; Dunjana, N.; Sanganyado, E. Sources, behaviour, and environmental and human health risks of high-technology rare earth elements as emerging contaminants. Sci Total Environ. 2018, 15, 636, pp. 299-313. Epub 2018 Apr 27. PMID: 29709849. [CrossRef]

- Abdelnour, S.A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Noreldin, A.E.; Arif, M.; Chaudhry M.T., Losacco, C.; Abdeen, A.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Impacts of rare earth elements on animal health and production: Highlights of cerium and lanthanum. Sci Total Environ. 2019, 1, 672, pp.1021-1032. PMID: 30999219. [CrossRef]

- Chung C, Deák F, Kavalali ET. Molecular substrates mediating lanthanide-evoked neurotransmitter release in central synapses. J Neurophysiol. 2008,100, 4, pp. 2089-2100. Epub 2008 Aug 20. PMID: 18715899; PMCID: PMC2576212. [CrossRef]

- Gaman, L.; Radoi, M.P.; Delia, C.E.; Luzardo, O.P.; Zumbado, M.; Rodríguez-Hernández, Á.; Stoian, I.; Gilca, M.; Boada, L.D.; Henríquez-Hernández, L.A. Concentration of heavy metals and rare earth elements in patients with brain tumours: Analysis in tumour tissue, non-tumour tissue, and blood. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2021, 31, pp.741–754. [CrossRef]

- Zheng L, Zhang J, Yu S, Ding Z, Song H, Wang Y, Li Y. Lanthanum Chloride Causes Neurotoxicity in Rats by Upregulating miR-124 Expression and Targeting PIK3CA to Regulate the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2020, 5, p.5205142. PMID: 32461997; PMCID: PMC7222569. [CrossRef]

- Wei J., Wang C., Yin S., Pi X., Jin L., Li Z. et al.) Concentrations of rare earth elements in maternal serum during pregnancy and risk for fetal neural tube defects. Environ Int. 2020, 137, p.105542. [CrossRef]

- Li Z, Liang T, Li K, Wang P. Exposure of children to light rare earth elements through ingestion of various size fractions of road dust in REEs mining areas. Sci Total Environ. 2020, 15, 743, p.140432. PMID: 32659548. [CrossRef]

- Peng R.L., Pan X.C., Xie Q. Relationship of the hair content of rare earth elements in young children aged 0 to 3 years to that in their mothers living in a rare earth mining area of Jiangxi. Chin J PrevMed. 2003, 37, pp.20–22 (in Chinese).

- Zhu, W.F.; Xu, S. Q.; Zhang, H., Shao, P.P., Wu, D.S., Yang, W.J., Feng J. Investigation of children intelligence quotient in REE mining area: Bio-effect study of REE mining area in South Jiangxi province. Chin. Sci. Bull. 1996, 41, pp.914–916 (in Chinese).

- Yongwei, W.; Dan, W.; Na, H.Y.; Peijia, S.; Bing, Y. Relationship between Rare Earth Elements, Lead and Intelligence of Children Aged 6 to 16 years: A Bayesian Structural Equation Modelling Method. Int. Arch. Nurs. Health. Care. 2019, 5, p. 123. [CrossRef]

- Fan, G.Q.; Yuan, Z.K.; Zheng, HL.; Liu, Z.J. Study on the effects of exposure to rare earth elements and health-responses in children aged 7–10 years. J Hyg Res. 2004, 33, pp. 23–28 (in Chinese).

- Zhu, W.; Xu, S.; Shao, P.; Zhang, H.; Wu, D.; Yang, W.; Feng, J. Bioelectrical activity of the central nervous system among populations in a rare earth element area. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 1997, 57, 1, pp.71-7. PMID: 9258470. [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Yang, M.; Gong, H.; Feng, X.; Hu, L., Li; R., Xu, S.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, H.; Zhou, A. Association between prenatal exposure to rare earth elements and the neurodevelopment of children at 24-months of age: A prospective cohort study. Environ Pollut. 2024, 15, 343, p.123201. PMID: 38135135. [CrossRef]

- Belisheva, N.K. Comparative Analysis of Morbidity and Elemental Composition of Hair Among Children Living on Different Territories of the Kola North. In Processes and Phenomena on the Boundary Between Biogenic and Abiogenic Nature, O.V. Frank-Kamenetskaya et al. (eds.), Lecture Notes in Earth System Sciences, Springer Nature, Switzerland AG. 2020, pp. 803-827. [CrossRef]

- Belisheva, N.; Martynova, A.; Mikhaylov, N. An Interdisciplinary Approach to Predicting the Effects of Trans-boundary Atmospheric Transport to Northwest European Neighboring States In Book Integration processes in the Russian and international research domain: Experience and prospects, KnE Social Sciences, 2022. pp. 158–171. [CrossRef]

- Mazukhina, S.; Krasavtseva, E.; Makarov, D.; Maksimova, V. Thermodynamic Modeling of Hypergene Processes in Loparite Ore Concentration Tailings. Minerals. 2021, 11, 996. [CrossRef]

- Stovern, M.; Guzmán, H.; Rine, K.; Felix, O.; King, M.; Ela, W.; Betterton, E.; Sáez, A. Windblown Dust Deposition Forecasting and Spread of Contamination around Mine Tailings. Atmosphere. 2016, 7, 16.

- Wang, L.; and Liang, T. Accumulation and fractionation of rare Earth elements in atmospheric particulates around a mine tailing in Baotou, China. Atmos. Environ. 2014. 88, pp. 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Krasavtseva, E.; Maksimova, V.; Makarov, D.; Potorochin, E. Modelling of the Chemical Halo of Dust Pollution Migration in Loparite Ore Tailings Storage Facilities. Minerals 2021, 11, 1077. [CrossRef]

- Krasavtseva, E.A.; Maksimova, V.V.; Gorbacheva, T.T.; Makarov, D.V.; Alfertyev, N.L. Evaluation of soils and plants chemical pollution within the area affected by storages of loparite ore processing waste. Mine Surv. Subsurf. Use 2021, 112, 52–58. (In Russian).

- Krasavtseva, E.; Sandimirov, S.; Elizarova, I.; Makarov, D. Assessment of Trace and Rare Earth Elements Pollution in Water Bodies in the Area of Rare Metal Enterprise Influence: A Case Study-Kola Subarctic. Water 2022, 14, p.3406. [CrossRef]

- Shin, S.H.; Kim, H-O.; Rim, K.T. Worker Safety in the Rare Earth Elements Recycling Process From the Review of Toxicity and Issues. Safety and Health at Work. 2019, 10, 4, pp. 409-419. [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Wei, B.; Liao, X.; Liang, T.; et al. Levels of rare Earth elements, heavy metals and uranium in a population living in Baiyun Obo, inner Mongolia, China: A pilot study. Chemosphere. 2015. 128, pp. 161–170. [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Yin, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.; Hou, R.; Wang, S. Investigation of rare Earth elements in urine and drinking water of children in mining area. Medicine 2018. 97, e12717. [CrossRef]

- Wei, B.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; Yu, J.; Ye, B.; and Liang, T. Rare Earth elements in human hair from a mining area of China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2013. 96, pp. 118–123. [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.L., Zhu, W.Z., Gao, Z.H., Meng, Y.X., Peng, R.L.., Lu, G.C. Distribution characteristics of rare earth elements in children’s scalp hair from a rare earths mining area in southern China. J. Environ. Sci. Health. A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2004, 39, 9, p.2517-32. PMID: 15478941. [CrossRef]

- Li, Xf.; Chen, Zb.; Chen, Zq. Distribution and fractionation of rare earth elements in soil–water system and human blood and hair from a mining area in southwest Fujian Province, China. Environ Earth Sci. 2014, 72, pp. 3599–3608. [CrossRef]

- Meryem, B.; Hongbing, J. I.; Yang, G.; Huajian, D.; Cai, L. (). Distribution of rare Earth elements in agricultural soil and human body (scalp hair and urine) near smelting and mining areas of Hezhang, China. J. Rare Earths. 2016, 34, pp. 1156–1167. [CrossRef]

- Edahbi, M.; Plante, B.; Benzaazoua, M. Environmental challenges and identification of the knowledge gaps associated with REE mine wastes management. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, pp. 1232–1241. [CrossRef]

- Billionnet, C. et al. Estimating the health effects of exposure to multi-pollutant mixture. Ann. Epidemiol. 2012. 22, pp. 126–141. [CrossRef]

- Dominici, F. et al. Protecting human health from air pollution: Shifting from a single-pollutant to a multipollutant approach. Epidemiology 2010, 21, pp. 187–194. [CrossRef]

- Report of IAEA, Coordinated Research Programme NAH: The Significance of Hair Mineral Analysis as a Means for Assessing Internal Body Badens of Environmental Pollutants; Vienna, 1993; Res-18.

- Method for determining trace elements in diagnosed biosubstrates by inductively coupled argon plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Guidelines, Moscow, Russian, 2003, p. 34 (in Russian).

- Seregina, I.F.; Osipov, K.; Bolshov, M.A.; Filatova, D.G.; Lanskaya, S.Yu. Matrix Interference in the Determination of Elements in Biological Samples by Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry and Methods for Its Elimination. J. Analyt. Chem. 2019, 74, pp. 182–191. [CrossRef]

- Pashkevich, M.A..; Stryzhenok, A.V. Analysis of the landscape-geochemical situation in the area of the tailings management of ANOF-2 of JSC Apatit. Notes of the Mining Institute. 2013, 206, pp. 155-159 (in Russian).

- Mikhailova, L.A.; Baranovskaya, N.V.; Bondarevich, E.A.; Vitkovsky, Y.A.; Zhornyak, L.V.; Epova, E.S.; Eryomin, O.V.; Nimaeva, B.V.; Ageeva, E.V. Determination of elemental homeostasis of the child population of Zabaikalsky Krai by the method of multi-element instrumental neutron activation analysis. Gigiena i Sanitariya. 2023, 102, 2, pp. 123-131 (in Russian).

- Baranovskaya, N.V.; Rikhvanov, L.P.; Ignatova, T.N., Narkovich, D.V.; Denisova O.A. The human geochemistry essays: Monograph. Tomsk Polytechnic University Publishing House, Tomsk, 2015; p. 378, ISBN 978-5-4387-0581-9.

- Rodushkin, I.; Axelsson, M.D. Application of double focusing sector field ICP-MS for multielemental characterization of human hair and nails. Part II. A study of the inhabitants of northern Sweden. Sci Total Environ. 2000, 262,1-2, pp. 21-36. PMID: 11059839. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Xiao, H.; He, X.; Li, Z.; Li, F.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Chai, Z. Neurotoxicological consequence of long-term exposure to lanthanum. Toxicol Lett. 2006, 165, 2, pp. 112-20. PMID: 16542800. [CrossRef]

- Tong, S.L.; Zhu, W.Z.; Gao, Z.H.; Meng, Y.X.; Peng, R.L.; Lu G.C. Distribution characteristics of rare earth elements in children’s scalp hair from a rare earths mining area in southern China. J. Environ. Sci. Health. A Tox. Hazard. Subst. Environ. Eng. 2004, 39, 9, pp. 2517-32. PMID: 15478941. [CrossRef]

- Yongwei, W.; Dan, W.; Na, H.Y.; Peijia, S.; Bing, Y. Relationship between Rare Earth Elements, Lead and Intelligence of Children Aged 6 to 16 years: A Bayesian Structural Equation Modelling Method. Int. Arch. Nurs. Health. Care 2019, 5, p. 123. [CrossRef]

- Heuser, J.; Miledi, R. Effects of lanthanum ions on function and structure of frog neuromuscular junctions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol Sci. 1971, 179, 1056, pp. 247-60. PMID: 4400214. [CrossRef]

- Kajimoto, N.; Kirpekar, S.M. Effect of manganese and lanthanum on spontaneous release of acetylcholine at frog motor nerve terminals. Nat. New. Biol. 1972, 235, 53, pp. 29-30. PMID: 4502408. [CrossRef]

- Alnaes, E.; Rahamimoff, R. Dual Action of Praseodymium (Pr3+) on Transmitter Release at the Frog Neuromuscular Synapse. Nature, 1974, 247, pp. 478-479.

- Haley, T.J.; Komesu, N.; Efros, M.; Koste, L.; Upham H.C. Pharmacology and toxicology of praseodymium and neodymium chlorides. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1964, 6, pp. 614-20. PMID: 14217003. [CrossRef]

- Haley, T.J.; Koste, L.; Komesu, N.; Efros, M.; Upham H.C. Pharmacology and toxicology of dysprosium, holmium, and erbium chlorides. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1966, 8, 1, pp. 37-43. PMID: 5921895. [CrossRef]

- Haley, T.J.; Komesu, N.; Fleswer, A.M.M.; Mavis, L.; Cawthorne, J.; Upham, H.C. Pharmacology and toxicology of terbium, thulium, and ytterbium chlorides. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1963, 5, pp. 427-436. [CrossRef]

- Haley, T.J., Raymond, K., Komesu, N.., Upham, H.C. Toxicological and pharmacological effects of gadolinium and samarium chlorides. Br. J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1961, 17, 3, pp. 526-32. PMID: 13903826; PMCID: PMC1482085. [CrossRef]

- Haley, T.J.; Komesu, N.; Mavis, L.; Cawthorne, J.; Upham, H.C. Pharmacology and toxicology of scandium chloride. J. Pharm. Sci. 1962, 51, p. 1043-5. PMID: 13952089. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, L.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Chai, Z. Distribution of ytterbium-169 in rat brain after intravenous injection. Toxicol Lett. 2005 a. 155, 2, pp. 247-52. PMID: 15603919. [CrossRef]

- Baranovskaya N.V., Mazukhina S.I., Panichev A.M., VakhЕ.А., Tarasenko I.A., Seryodkin I.V., Ilenok S.S., Ivanov V.V., Ageeva E.V., Makarevich R.A., Strepetov D.A., Vetoshkina A.V. Features of chemical elements migration in natural waters and their deposition in the form of neocrystallisations in living organisms (physico-chemical modeling with animal testing). Bulletin of the Tomsk Polytechnic University. Geo Assets Engineering, 2024, vol. 335, no. 2, pp. 187–201. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Xiao, H.; He, X.; Li, Z.; Li, F.; Liu, N.; Zhao, Y.; Huang Y.; Zhang Z.; Chai, Z. Neurotoxicological consequence of long-term exposure to lanthanum. Toxicol. Lett. 2006, 165, 2, pp.112-20. PMID: 16542800. [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; He, X.; Xiao, H.; Li, Z.; Li, F.; Liu, N.; Chai, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z. Ytterbium and trace element distribution in brain and organic tissues of offspring rats after prenatal and postnatal exposure to ytterbium. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2007, 117, 1-3, pp. 89-104. PMID: 17873395. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z. Neurotoxicological evaluation of long-term lanthanum chloride exposure in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2008, 103, 2, pp. 354-61. Epub 2008 Mar 3. PMID: 18319242. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Yu, F.; Wu, S.; Jin, C.; Lu, X.; Zhang L.; Du, Y.; Xi Q.; Cai Y. Lanthanum chloride impairs spatial learning and memory and down regulates NF-κB signalling pathway in rats. Arch Toxicol. 2013, 87, 12, pp. 2105-17. PMID: 23670203. [CrossRef]

- Iliff, J.J.; Lee, H.; Yu, M.; Feng, T.; Logan, J.; Nedergaard, M. et al. Brain-wide pathway for waste clearance captured by contrast enhanced MRI. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, pp. 1299–309. [CrossRef]

- Evans, C.H. Biochemistry of the Lanthanides. Plenum Press, New York, USA, 1990; pp. 25–31.

- Przywara, D.A.; Bhave, S.V.; Bhave, A.; Chowdhury P.S.; Wakade, T.D.; Wakade, A.R. Activation of K+ channels by lanthanum contributes to the block of transmitter release in chick and rat sympathetic neurons. J. Membr. Biol. 1992, 125, 2, pp. 155-62. PMID: 1552563. [CrossRef]

- Blaustein, M.P.; Goldman, D.E. The action of certain polyvalent cations on the voltage-clamped lobster axon. J. Gen. Physiol. 1968, 51, 3, pp. 279-91. PMID: 5648828; PMCID: PMC2201132. [CrossRef]

- Van Breemen, C.; De Weer, P. Lanthanum inhibition of 45Ca efflux from the squid giant axon. Nature 1970, 226, 5247, pp. 760-1. PMID: 5443255. [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Chakrabarty, K.; Chatterjee, G.C. Neurotoxicity of lanthanum chloride in newborn chicks. Toxicol Lett. 1982, 14, 1-2, pp. 21-5. PMID: 6130644. [CrossRef]

- Basu, A.; Chakrabarty, K.; Haldar, S.; Addya, S.; Chatterjee, G.C. The effects of lanthanum chloride administration in newborn chicks on glutamate uptake and release by brain synaptosomes. Toxicol. Lett. 1984, 20, 3, pp. 303-8. PMID: 6701916. [CrossRef]

- Miledi, R. Lanthanum ions abolish the “calcium response” of nerve terminals. Nature. 1971, 229, 5284, pp. 410-411. PMID: 4323456. [CrossRef]

- Osborne, R.H.; Bradford, H.F. The influence of sodium, potassium and lanthanum on amino acid release from spinal-medullary synaptosomes. J Neurochem. 1975, 25, 1, pp. 35-41. PMID: 166144. [CrossRef]

- Metral, S.; Bonneton, C.; Hort-Legrand, C.; Reynes, J. Dual action of erbium on transmitter release at the frog neuromuscular synapse. Nature. 1978, 271, 5647, pp. 773-5. PMID: 24184. [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Chai, Z. Neurotoxicological evaluation of long-term lanthanum chloride exposure in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2008, 103, 2, pp. 354-61. Epub 2008 Mar 3. PMID: 18319242. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wu, S.; Qi, M.; Lu, S.; Xi, Q.; Cai, Y. Lanthanum chloride impairs memory, decreases pCaMK IV, pMAPK and pCREB expression of hippocampus in rats. Toxicol. Lett. 2009, 190, 2, pp. 208-14. PMID: 19643171. [CrossRef]

- Heuser, J.E. The Structural Basis of Long-Term Potentiation in Hippocampal Synapses, Revealed by Electron Microscopy Imaging of Lanthanum-Induced Synaptic Vesicle Recycling. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, pp. 920360. PMID: 35978856; PMCID: PMC9376242. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Cheng, Z., Hu, R., Chen, J., Hong, M., Zhou, M., Gong, X., Wang, L., Hong, F. Oxidative injury in the brain of mice caused by lanthanid. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2011, 142, 2, pp. 174-89. PMID: 20614199. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z., Li, N., Cheng, J., Hu, R., Gao, G., Cui, Y., Gong, X., Wang, L., Hong, F. Signal pathway of hippocampal apoptosis and cognitive impairment of mice caused by cerium chloride. Environ. Toxicol. 2012, 27, 12, pp. 707-18. PMID: 21384496. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F. et al. Accumulation and distribution of samarium-153 in rat brain after intraperitoneal injection. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2005. 104, pp. 33–40. [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T., Ishii, K., Kawaguchi, H., Kitajima, K., Takenaka D. High signal intensity in the dentate nucleus and globus pallidus on unenhanced T1-weighted MR images: Relationship with increasing cumulative dose of a gadolinium-based contrast material. Radiology 2014, 270, pp. 834–41. [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T., Nakai, Y., Aoki, S., Oba, H., Toyoda, K., Kitajima, K., Furui, S. Contribution of metals to brain MR signal intensity: Review articles. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2016, 34, 4, pp. 258-66. PMID: 26932404. [CrossRef]

- Kanda, T.; Nakai, Y.; Hagiwara, A.; Oba, H.; Toyoda, K.; Furui, S. Distribution and chemical forms of gadolinium in the brain: A review. Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 1079, pp. 20170115. PMID: 28749164; PMCID: PMC5963376. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, R.J., McDonald, J.S., Kallmes, D.F., Jentoft, M.E., Paolini, M.A., Murray, D.L., Williamson, E.E., Eckel, L.J. Gadolinium Deposition in Human Brain Tissues after Contrast-enhanced MR Imaging in Adult Patients without Intracranial Abnormalities. Radiology. 2017, 285, 2, p. 546-554. PMID: 28653860. [CrossRef]

- Nnomo, A., Dieme, D., Jomaa, M. et al. Toxicokinetic study of scandium oxide in rats. Toxicology Letters. 2024. 392. pp. 56-63. [CrossRef]

- Yokel RA, Au TC, MacPhail R; et al. Distribution, elimination, and biopersistence to 90 days of a systemically introduced 30 nm ceria-engineered nanomaterial in rats. Toxicol Sci. 2012, 27, 1, pp. 256–268. [CrossRef]

- Jin, C., Gao, L., Li, Y., Wu, S., Lu, X., Yang, J., Cai, Y. Lanthanum damages learning and memory and suppresses astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle in rat hippocampus. Exp. Brain. Res. 2017, 235, 12, pp. 3817-3832. PMID: 28993860. [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Mao, H.; Liu, J.; Sun, W.; Wu, S.; Lu, X.; Jin, C.; Yang, J. Lanthanum Chloride Induces Axon Abnormality Through LKB1-MARK2 and LKB1-STK25-GM130 Signaling Pathways. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2023, 43, 3, pp. 1181-1196. [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Zhang, P.; Liu, J.; Xue, Y. Effect of long-term intake of Y3+ in drinking water on gene expression in brains of rats. Journal of Rare Earths, 2006, 24, 3, pp. 369-373.

- Chen J, Xiao HJ, Qi T, Chen DL, Long HM, Liu SH. Rare earths exposure and male infertility: The injury mechanism study of rare earths on male mice and human sperm. Environ SciPollut Res Int. 2015, 22, 3, pp. 2076-2086. Epub 2014 Aug 30. PMID: 25167826. [CrossRef]

- Fahn, S.; Jankovic, J.; Hallett, M. Principles and Practice of Movement Disorders. 2nd ed. Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, 2011.

- Delorme, C.; Giron, C.; Bendetowicz, D.; Méneret, A.; Mariani, L.L.; Roze, E. Current challenges in the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of paroxysmal movement disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2021, 21, 1, pp. 81-97. PMID: 33089715. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.; Xu, Z.Y.; Wu, Y.C.; Tan, E.K. Paroxysmal movement disorders: Recent advances and proposal of a classification system. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2019, 59, pp. 131-139. PMID: 30902529. [CrossRef]

- Garone, G.; Capuano, A.; Travaglini, L.; Graziola, F.; Stregapede, F.; Zanni, G.; Vigevano, F.; Bertini, E.; Nicita, F. Clinical and Genetic Overview of Paroxysmal Movement Disorders and Episodic Ataxias. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 10, pp. 3603. PMID: 32443735; PMCID: PMC7279391. [CrossRef]

- Mark, M.D.; Maejima, T.; Kuckelsberg, D.; Yoo, J.W.; Hyde, R.A.; Shah, V.; Gutierrez, D.; Moreno, R.L.; Kruse, W.; Noebels, J.L.; Herlitze, S. Delayed postnatal loss of P/Q-type calcium channels recapitulates the absence epilepsy, dyskinesia, and ataxia phenotypes of genomic Cacna1a mutations. J Neurosci. 2011, 31, 11, pp. 4311-26. PMID: 21411672; PMCID: PMC3065835. [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.H.; Liu, Y.Y.; Wang, L.; Li, K.; Zhang, Z.Q.; Li, H.F.; Yang, Z.F.; Li, Y.; Li, D.; Wu, M.Y.; Yu, C.L.; Long, J.J.; Chen, R.C.; Li, L.X.; Yin, L.P.; Liu, J.W.; Cheng, X.W.; Shen Q.; Shu, Y.S.; Sakimura, K.; Liao, L.J.; Wu, Z.Y.; Xiong, Z.Q. PRRT2 deficiency induces paroxysmal kinesigenic dyskinesia by regulating synaptic transmission in cerebellum. Cell Res. 2018, 28, 1, pp. 90-110. PMID: 29056747; PMCID: PMC5752836. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, F.; Hamodeh, S.; Baizer, J.S. The human dentate nucleus: A complex shape untangled. Neuroscience. 2010, 167, 4, pp. 965-8. PMID: 20223281. [CrossRef]

- Saab, C.Y.; Willis, W.D. The cerebellum: Organization, functions and its role in nociception. Brain. Res. Brain. Res. Rev. 2003, 42, 1, pp. 85-95. PMID: 12668291. [CrossRef]

- Dum, R.P.; Strick, P.L. An unfolded map of the cerebellar dentate nucleus and its projections to the cerebral cortex. J. Neurophysiol. 2003, 89, 1, pp. 634-9. PMID: 12522208. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth N.; Leviton, A.; Goldstein, M.; Bax M.; Damiano, D.; Dan, B.; Jacobsson, B. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. Suppl. 2007, 109, pp. 8-14. Erratum in: Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2007, 49, 6, pp. 480. PMID: 17370477.

- Graham, H.K.; Rosenbaum, P.; Paneth, N.; Dan, B.; Lin J.P.; Damiano, D.L.; Becher, J.G.; Gaebler-Spira, D.; Colver, A.; Reddihough, D.S.; Crompton, K.E.; Lieber, R.L. Cerebral palsy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016, 2, pp.15082. PMID: 27188686; PMCID: PMC9619297. [CrossRef]

- Colver, A.; Fairhurst, C.; Pharoah, P.O. Cerebral palsy. Lancet. 2014, 383, 9924, pp. 1240-9. PMID: 24268104. [CrossRef]

- Pharoah, P.O. Prevalence and pathogenesis of congenital anomalies in cerebral palsy. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal. Neonatal. Ed. 2007, 92, 6, pp. F489-93. PMID: 17428819; PMCID: PMC2675398. [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.R.; Neelakantan, M.; Pandher, K.; Merrick, J. Cerebral palsy in children: A clinical overview. Transl. Pediatr. 2020, 9, (Suppl 1), pp. S125-S135. PMID: 32206590; PMCID: PMC7082248. [CrossRef]

- Copp, A.J.; Stanier, P.; Greene, N.D. Neural tube defects: Recent advances, unsolved questions, and controversies. Lancet Neurol. 2013, 12, 8, pp. 799-810. PMID: 23790957; PMCID: PMC4023229. [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Spencer, K.A.; Borodinsky, L.N. From Neural Tube Formation Through the Differentiation of Spinal Cord Neurons: Ion Channels in Action During Neural Development. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2020, 13, p. 62. PMID: 32390800; PMCID: PMC7193536. [CrossRef]

- McCobb, D.P.; Best, P.M.; Beam, K.G. The differentiation of excitability in embryonic chick limb motoneurons. J. Neurosci. 1990, 10, pp. 2974–2984. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ladas, T.P.; Qiu, C.; Shivacharan, R.S.; Gonzalez-Reyes, L.E.; Durand, D.M. Propagation of Epileptiform Activity Can Be Independent of Synaptic Transmission, Gap Junctions, or Diffusion and Is Consistent with Electrical Field Transmission. Journal of Neuroscience 2014, 34, 4, pp. 1409-1419. [CrossRef]

- Greene, N.D.; Copp, A.J. Neural tube defects. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2014, 37, pp. 221-42. PMID: 25032496; PMCID: PMC4486472. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Ren, A.; Yang, Z.; Pei, L.; Hao, L.; Xie, Q.; Jiang, Y. Correlation studies of trace elements in mother’s hair, venous blood and cord blood. Chinese J. Reprod. Health, 2005.

- Das, T.; Sharma, A.; Talukder, G. Effects of lanthanum in cellular systems. A review. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 1988, 18, pp. 201-28. PMID: 2484565. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; He, J.; Xia, A.; Cheng, M.; Yang, Q.; Du, C.; Wei, H.; Huang, X.; Zhou, Q. Toxic effects of environmental rare earth elements on delayed outward potassium channels and their mechanisms from a microscopic perspective. Chemosphere. 2017, 181, pp. 690-698. PMID: 28476009. [CrossRef]

- Pharoah, P.O. Causal hypothesis for some congenital anomalies. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2005, 8, 6, pp. 543-50. PMID: 16354495. [CrossRef]

- Pharoah, P.O., Dundar, Y. Monozygotic twinning, cerebral palsy and congenital anomalies. Hum Reprod Update. 2009, 15, 6, pp. 639-48. PMID: 19454557. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, J.; Cans, C.; Garne, E.; Colver, A.; Dolk, H.; Uldall, P.; Amar E.; Krageloh-Mann I. Congenital anomalies in children with cerebral palsy: A population-based record linkage study. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010, 52, 4, pp. 345-51. PMID: 19737295. [CrossRef]

- Bahtiyar MO, Dulay AT, Weeks BP, Friedman AH, Copel JA. Prevalence of congenital heart defects in monochorionic/diamniotic twin gestations: A systematic literature review. J. Ultrasound Med. 2007, 26, 11, pp. 1491-8. PMID: 17957043. [CrossRef]

- Croen, L.A.; Grether, J.K.; Curry, C.J.; Nelson, K.B. Congenital abnormalities among children with cerebral palsy: More evidence for prenatal antecedents. J Pediatr. 2001, 138, 6, pp. 804-10. PMID: 11391320. [CrossRef]

- Garne, E.; Dolk, H.; Krägeloh-Mann, I.; Holst Ravn, S.; Cans, C. SCPE Collaborative Group. Cerebral palsy and congenital malformations. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2008, 12, 2, pp. 82-8. PMID: 17881257. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y. Study on distributions and accumulations of rare earth element cerium (141Ce) in mice. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. 2000, [accessed Jun 14 2012]. Available online: http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTALNJNY200003025.htm. Chinese.

- Liu, Y.; Wu, M.; Zhang, L.; Bi, J.; Song, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, B.; Zhou, A.; Cao, Z.; Xiong, C.; Yang, S.; Xu, S.; Xia, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y. Prenatal exposure of rare earth elements cerium and ytterbium and neonatal thyroid stimulating hormone levels: Findings from a birth cohort study. Environ. Int. 2019, 133 (Pt B), pp. 105222. PMID: 31655275. [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Ni, W.; Pan Y.; Chen, Y.; Xie, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ren, A. Rare earth elements in umbilical cord and risk for orofacial clefts. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021, 207, pp. 111284. PMID: 32942100. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, T.; Ma, L. et al. Action of Akt Pathway on La-Induced Hippocampal Neuron Apoptosis of Rats in the Growth Stage. Neurotox. Res. 2020, 38, pp. 434-446. [CrossRef]

- Sun, W., Yang, J., Hong, Y. et al. Lanthanum Chloride Impairs Learning and Memory and Induces Dendritic Spine Abnormality by Down-Regulating Rac1/PAK Signaling Pathway in Hippocampus of Offspring Rats. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2020, 40, pp. 459–475. [CrossRef]

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C. Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J. Pain. 2009, 10, 9, pp. 895–926. [CrossRef]

- Malenka R. The long-term potential of LTP. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2003, 4, 11, pp. 923-926. [CrossRef]

- Yuste, R.; Bonhoeffer, T. Genesis of dendritic spines: Insights from ultrastructural and imaging studies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004, 5, 1, pp. 24–34. [CrossRef]

- Tada, T.; Sheng, M. Molecular mechanisms of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2006, 16, 1, pp. 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Allers, K.; Essue, B.M.; Hackett, M.L.; Muhunthan, J.; Anderson, C.S.; Pickles, K.; Scheibe, F.; Jan, S. The economic impact of epilepsy: A systematic review. BMC Neurol. 2015, 15, pp. 245. PMID: 26607561; PMCID: PMC4660784. [CrossRef]

- Pitkanen, A.; Engel, J.Jr. (2014). Past and present definitions of epileptogenesis and its biomarkers. Neurotherapeutics, 2014, 11, pp. 231–241. [CrossRef]

- Engel, T.; Brennan, G.P.; Soreq, H. Editorial: The molecular mechanisms of epilepsy and potential therapeutics. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2022, 15, pp. 1064121. [CrossRef]

- Jefferys, J.G. Advances in understanding basic mechanisms of epilepsy and seizures. Seizure. 2010, 19, 10, pp.638-46. PMID: 21095139. [CrossRef]

- Fellin, T.; Pascual, O.; Gobbo, S.; Pozzan, T.; Haydon, P.G.; Carmignoto, G. Neuronal synchrony mediated by astrocytic glutamate through activation of extrasynaptic NMDA receptors. Neuron. 2004, 43, 5, pp. 729-43. Erratum in: Neuron. 2005, 45, 1, pp. 177. PMID: 15339653. [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, P.B.; Knappenberger, J.; Segal, M.; Bennett, M.V.; Charles, A.C.; Kater, S.B. ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves. J Neurosci. 1999, 19, 2, pp. 520-8. PMID: 9880572; PMCID: PMC6782195. [CrossRef]

- Angulo, M.C.; Kozlov, A.S.; Charpak, S.; Audinat, E. Glutamate released from glial cells synchronizes neuronal activity in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2004, 24, 31, pp. 6920-7. Erratum in: J Neurosci. 2004, 24, 34, pp. 2p following 7575. PMID: 15295027; PMCID: PMC6729611. [CrossRef]

- Halassa, M.M.; Fellin, T., Haydon, P.G. The tripartite synapse: Roles for gliotransmission in health and disease. Trends Mol Med. 2007, 13, 2, pp. 54-63. PMID: 17207662. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Liu, Q.; Qi, M.; Lu, S.; Wu, S.; Xi, Q.; Cai, Y. Lanthanum chloride promotes mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in primary cultured rat astrocytes. Environ. Toxicol. 2013, 28, 9, pp. 489-97. PMID: 21793157. [CrossRef]

- Verkhratsky, A.; Parpura, V. Astrogliopathology in neurological, neurodevelopmental and psychiatric disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2016, 85, pp. 254-261. PMID: 25843667; PMCID: PMC4592688. [CrossRef]

| n=53 | Mean | SD | Min | Max. | Median | P25 | P75 | C. V. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sc | 0,0536 | 0,1238 | 0,0010 | 0,5544 | 0,0010 | 0,0010 | 0,0010 | 230,9 |

| Y | 0,0204 | 0,0152 | 0,0090 | 0,0782 | 0,0157 | 0,0130 | 0,0193 | 74,6 |

| La | 0,0336 | 0,0222 | 0,0124 | 0,1288 | 0,0269 | 0,0198 | 0,0362 | 66,2 |

| Ce | 0,0351 | 0,0219 | 0,0053 | 0,1073 | 0,0297 | 0,0200 | 0,0412 | 62,3 |

| Pr | 0,0047 | 0,0019 | 0,0020 | 0,0131 | 0,0044 | 0,0038 | 0,0051 | 39,3 |

| Nd | 0,0161 | 0,0048 | 0,0089 | 0,0383 | 0,0154 | 0,0132 | 0,0174 | 29,7 |

| Sm | 0,0124 | 0,0069 | 0,0031 | 0,0548 | 0,0116 | 0,0092 | 0,0141 | 55,7 |

| Eu | 0,0049 | 0,0030 | 0,0017 | 0,0233 | 0,0045 | 0,0036 | 0,0054 | 61,9 |

| Gd | 0,0214 | 0,0024 | 0,0013 | 0,0630 | 0,0163 | 0,0101 | 0,0277 | 76,7 |

| Tb | 0,0032 | 0,0009 | 0,0015 | 0,0046 | 0,0032 | 0,0025 | 0,0040 | 27,3 |

| Dy | 0,0129 | 0,0199 | 0,0055 | 0,1531 | 0,0095 | 0,0080 | 0,0118 | 154,2 |

| Ho | 0,0031 | 0,0010 | 0,0015 | 0,0058 | 0,0033 | 0,0023 | 0,0038 | 30,3 |

| Er | 0,0077 | 0,0017 | 0,0032 | 0,0118 | 0,0076 | 0,0067 | 0,0091 | 22,4 |

| Tm | 0,0029 | 0,0009 | 0,0012 | 0,0050 | 0,0027 | 0,0023 | 0,0035 | 31,3 |

| Yb | 0,0121 | 0,0223 | 0,0037 | 0,1697 | 0,0091 | 0,0072 | 0,0103 | 184,0 |

| Lu | 0,0028 | 0,0012 | 0,0015 | 0,0089 | 0,0027 | 0,0022 | 0,0033 | 43,5 |

| Elements | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| M ± S.D. | Ме (Q25-Q75) | M ± S.D. | Ме (Q25-Q75) | M ± SE | M (S.D.) ME | Range | |

| Na | 642 ± 599 | 431 (275-783) | 728 ± 1198 | 389(143-940) | 223±17 | 147 (149) 94 | 17-670 |

| Ca | 287 ± 175 | 220 (186-349) | 960 ± 2844 | 228(100-673) | 1403±90 | 750 (660) 590 | 113-2890 |

| Sc | 0.054 ±0.124 | 0.001 (0.001-0.001) | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 0.02(0.01-0.02) | 0.007±0.0004 | 0.0014 (0.001) 0.0011 | 0.0004-0.0045 |

| Cr | 4.21 ±13.64 | 4.43 (1.32-6.5) | 5.23 ± 5.69 | 4.68(0.46-6.11) | 0.5±0.07 | 0.167 (0.118) 0.131 | 0.046-0.527 |

| Fe | 24.5 ±18.6 | 23.0 (13.6-29.8) | 853 ± 872 | 793(300-1018) | 45±3.7 | 9.6( 4.4) 8.4 | 4.9-23 |

| Co | 0.030 ±0.043 | 0.008 (0.002-0.047) | 1.05 ± 1.42 | 0.66(0.53-0.9) | 0.07±0.01 | 0.013 ( 0.011) 0.01 | 0.002-0.063 |

| Zn | 120 ±89 | 106 (77-130) | 210 ± 348 | 152(117-194) | 207±8 | 142 (29) 144 | 68-198 |

| As | 0.61 ±0.70 | 0.45 (0.001-0.96) | 0.42 ± 1.02 | 0.24(0.16-0.5) | < 0.8 | 0.085 (0.054) 0.067 | 0.034-0.319 |

| Se | 0.71±0.28 | 0.68 (0.50-0.87) | - | - | 0.8±0.03 | 0.83 (0.28) 0.79 | 0.48-1.84 |

| Br | - | - | 8.82 ± 17.23 | 3.96(2.07-7.91) | 6.5±0.6 | 37 (33) 26 | 5.6-221 |

| Rb | 0.72 ± 0.79 | 0.48 (0.27-1.05) | 0.79 ± 1.24 | 0.3(0.2-0.81) | < 3 | 0.093 (0.085) 0.06 | 0.012-0.482 |

| Sr | 1.38 ±1.65 | 0.59 (0.32-2.06) | 4.53 ± 1.23 | 5(2.5-5) | < 15 | 1.2 (1) 0.97 | 0.14-5.54 |

| Ag | 0.28 ±0.16 | 0.23 (0.19-0.35) | 2.34 ± 17.67 | 0.11(0.05-0.26) | 0.3±0.03 | 0.231 (0.298) 0.132 | 0.025-1.96 |

| Sb | 0.06 ±0.06 | 0.044 (0.028-0.07) | 0.11 ± 0.15 | 0.06(0.03-0.12) | 0.07±0.01 | 0.022 (0.017) 0.017 | 0.007-0.122 |

| Cs | 0.014 ±0.022 | 0.01 (0.005-0.014) | 0.03 ± 0.14 | 0.005(0.001-0.02) | < 0.05 | 0.00067 (0.00046) 0.00051 | 0.00017-0.0019 |

| Ba | 0.58 ±0.88 | 0.41 (0.21-0.60) | 4.07 ± 12.24 | 2(1.97-2.43) | < 10 | 0.64 (0.49) 0.46 | 0.16-1.92 |

| Y | 0.020 ±0.015 | 0.016 (0.013-0.019) | - | - | - | - | - |

| La | 0.034 ±0.022 | 0.027(0.02-0.036) | 0.04 ± 0.09 | 0.02(0.01-0.02) | 0.05±0.006 | 0.035 (0.046) 0.018 | 0.0046-0.106 |

| Ce | 0.035 ±0.022 | 0.03 (0.02-0.041) | 0.39 ± 1.79 | 0.1(0.05-0.1) | < 0.08 | 0.039 (0.05) 0.019 | 0.007-0.164 |

| Pr | 0.005 ±0.002 | 0.004 (0.004-0.005) | - | - | - | ||

| Nd | 0.016 ±0.005 | 0.015 (0.013-0.017) | 0.25 ± 0.46 | 0.09(0.09-0.22) | - | ||

| Sm | 0.0124 ±0.007 | 0.012 (0.009-0.014) | 0.006 ± 0.02 | 0.003(0-0.003) | 0.02±0.003 | ||

| Eu | 0.005 ±0.003 | 0.004 (0.004-0.005) | 0.02 ± 0.07 | 0.004(0.001-0.01) | < 0.03 | ||

| Gd | 0.0214 ±0.016 | 0.016 (0.010-0.028) | - | - | - | ||

| Tb | 0.003 ±0.001 | 0.003 (0.002-0.004) | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.005(0.005-0.02) | 0.01±0.0003 | ||

| Dy | 0.013 ±0.02 | 0.01 (0.008-0.012) | - | - | - | ||

| Ho | 0.003 ±0.001 | 0.003 (0.002-0.004) | - | - | - | ||

| Er | 0.008 ±0.002 | 0.008 (0.007-0.009) | - | - | - | ||

| Tm | 0.003±0.001 | 0.003 (0.002-0.004) | - | - | - | ||

| Yb | 0.012 ±0.022 | 0.009 (0.007-0.010) | 0.007 ± 0.009 | 0.005(0-0.009) | 0.03±0.0005 | ||

| Lu | 0.003 ±0.001 | 0.003 (0.002-0.003) | 0.003 ± 0.01 | 0.001(0-0.003) | 0.002±0.0001 | ||

| Hf | 0.004 ±0.005 | 0.004 (0.001-0.007) | 0.05 ± 0.12 | 0.037(0.001-0.05) | 0.02±0.002 | 0.005 (0.008) 0.0017 | 0.0004-0.037 |

| Ta | 0.006 ±0.015 | 0.006 (0.001-0.001) | 0.02 ± 0.04 | 0.008(0-0.008 | < 0.03 | 0.004 (0.003) 0.0031 | <0.002-0.020 |

| Au | 0.012 ±0.021 | 0.012 (0.001-0.017) | 0.03 ± 0.14 | 0.001(0-0.01) | 0.11±0.03 | 0.03 (0.028) 0.017 | 0.003-0.200 |

| Hg | 0.42±0.197 | 0.42 (0.31-0.5) | - | - | 0.4±0.04 | 0.261 (0.145) 0.249 | 0.053-0.927 |

| Th | <0.001 <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.23 ± 0.29 | 0.14(0.05-0.27) | 0.02±0.001 | 0.0013 (0.001) 0.001 | 0.0003-0.0044 |

| U | 0.005 ±0.003 | 0.005 (0.003-0.006) | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01(0.01-0.016) | 0.33±0.07 | 0.057 (0.065) 0.036 | 0.006-0.436 |

| L-G.M.(R) | L-M±SE | M1-G.M.(R) | M2-G.M.(R) | C1-G.M.(R) | C2-G.M.(R) | |

| La* | 0.03(0.01-0.13) | 0.033±0.003 | 0.89(0.17-6.93) | 0.45(0.14-0.37) | 0.12(0.05-0.30) | 0.11(0.04-0.40) |

| Ce* | 0.03(0.01-0.11) | 0.035±0.003 | 0.53(0.20-1.37) | 0.34(0.16-0.82) | 0.22(0.09-0.57) | 0.16(0.07-0.44) |

| Pr* | 0.004(0.00-0.01) | 0.005±0.000 | 0.19(0.04-1.55) | 0.08(0.03-0.26) | 0.03(0.01-0.09) | 0.02(0.01-0.09) |

| Nd* | 0.016(0.01-0.04) | 0.016±0.001 | 0.67(0.13-5.27) | 0.28(0.09-0.95) | 0.12(0.04-0.32) | 0.09(0.04-0.32) |

| Sm* | 0.01(0.00-0.05) | 0.012±0.001 | 0.11(0.02-0.91) | 0.04(0.03-0.12) | 0.03(0.01-0.06) | 0.02(0.01-0.07) |

| Eu | 4.4(1.70-23.33) | 4.9±0.04 | 12.1(2.9-95.0) | 6.0(2.6-21.2) | 3.7(1.8-8.7) | 2.4(1.9-6.6) |

| Gd | 15.1(1.29-63.22) | 21.4±0.2 | 90.5(19.4-645.6) | 30.6(12.2-119.0) | 23.7(8.3-59.3) | 29.5(9.8-64.6) |

| Tb | 3.0(1.51-4.65) | 3.17±0.012 | 11.1(2.6-73.8) | 3.3(1.4-13.2) | 3.4(1.3-8.3) | 3.1(1.6-9.7) |

| Dy | 10.3(5.51-153.10) | 12.9±0.27 | 53.5(13.6-338.6) | 15.1(6.4-63.0) | 18.2(7.5-44.1) | 17.8(9.8-54.5) |

| Ho | 3.0(1.53-5.83) | 3.14±0.013 | 8.5(2.2-55.63) | 2.3(1.0-10.7) | 3.1(1.2-7.3) | 3.2(1.7-10.4) |

| Er | 7.5(3.23-11.79) | 7.74±0.024 | 20.7(5.7-134.3) | 15.9(2.7-27.3) | 8.5(3.8-20.1) | 8.8(5.2-28.9) |

| Tm | 2.8(1.24-4.96) | 2.9±0.012 | 2.3(0.6-16.2) | 0.6(0.3-3.1) | 1.1(0.4-2.5) | 1.2(0.6-4.1) |

| Yb | 9.1(3.68-169.73) | 12.1±0.307 | 13.5(4.4-90.5) | 3.6(1.6-18.3) | 6.6(3..6-15.0) | 7.1(3.9-22.3) |

| Lu | 2.7(1.47-8.93) | 2.8±0.017 | 1.7(0.4-13.3) | 0.5(0.2-2.6) | 0.8(0.4-2.0) | 1.0(0.4-3.3) |

| Y | 17.5(0.009-0.0078)* | 20.0±2.0 | 203.5(0.06-1.27)* | 71.2(0.03-0.30)* | 82.3(0.03-0.19)* | 76.5(0.04-0.29)* |

| Sc | 3.4(1.0-554.0) | 53.6±17.0 | 154 | 195.5 | 194.7 | 243.1 |

| *Unit µg/g; other - ng/g; G.M.: geometric mean; R: minimum and maximum values | ||||||

| Lovozero village, Russia | 4 village, China | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | P25 | P75 | M | P25 | P75 | ||

| La | 0,0269 | 0,0198 | 0,0362 | 0.3907 | 0.2399 | 1.1505 | |

| Ce | 0,0297 | 0,0200 | 0,0412 | 0.5958 | 0.3811 | 1.6591 | |

| Pr | 0,0044 | 0,0038 | 0,0051 | 0.0489 | 0.0337 | 0.1271 | |

| Nd | 0,0154 | 0,0132 | 0,0174 | 0.1646 | 0.1098 | 0.3574 | |

| Sm | 0,0116 | 0,0092 | 0,0141 | 0.0226 | 0.0150 | 0.0364 | |

| Eu | 0,0045 | 0,0036 | 0,0054 | 0.0060 | 0.0042 | 0.0097 | |

| Gd | 0,0163 | 0,0101 | 0,0277 | 0.0184 | 0.0118 | 0.0296 | |

| Tb | 0,0032 | 0,0025 | 0,0040 | 0.0020 | 0.0009 | 0.0030 | |

| Dy | 0,0095 | 0,0080 | 0,0118 | 0.0112 | 0.0066 | 0.0151 | |

| Ho | 0,0033 | 0,0023 | 0,0038 | 0.0020 | 0.0012 | 0.0027 | |

| Er | 0,0076 | 0,0067 | 0,0091 | 0.0051 | 0.0028 | 0.0071 | |

| Tm | 0,0027 | 0,0023 | 0,0035 | 0.0009 | 0.0005 | 0.0015 | |

| Yb | 0,0091 | 0,0072 | 0,0103 | 0.0049 | 0.0030 | 0.0064 | |

| Lu | 0,0027 | 0,0022 | 0,0033 | 0.0006 | 0.0003 | 0.0010 | |

| Y | 0,0157 | 0,0130 | 0,0193 | 0.0497 | 0.0312 | 0.0672 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).