1. Introduction

Turmeric (

Curcuma longa L.) is a widely recognized and culturally significant spice and medicinal crop cultivated in Vietnam. It plays an integral role in the traditional rituals, ceremonies, and spiritual practices of various ethnic groups in the Northern Mountains, including the Hmong, Dao, Thai, and Muong communities [

1]. Turmeric is commonly used to dye fabrics, clothing, and handicrafts produced by these ethnic minority groups, further enhancing the cultural significance of their traditional textiles and crafts. In traditional medicine, turmeric is widely used to treat various ailments due to its perceived therapeutic properties [

2].

The accumulation of secondary metabolites in herbal rhizomes is a crucial process that contributes to their medicinal and aromatic properties. As the rhizome develops, enzymatic pathways synthesize various secondary metabolites, such as alkaloids, saponins, and phenolics, which can accumulate to high concentrations and protect the plant from self-toxicity. The levels of these compounds, including curcuminoids in turmeric, generally increase as the rhizome matures toward harvest. This dynamic and regulated process enables plants to adapt to their environment while producing compounds valuable for both the plant's survival and human use [

3].

An especially interesting feature of the turmeric plant is its natural immunity to pests, which often eliminates the need for pesticides during the growing process. In the Northern Mountains of Vietnam, ethnic minority farmers use traditional cultivation methods that differ from commercial turmeric production and influence the accumulation of secondary metabolites in turmeric. Additionally, the mountain's climate and soil contribute to distinct phytochemical profiles compared to turmeric grown in other regions. The Northern Mountains have a cooler, more temperate climate compared to other parts of Vietnam. Variations in temperature, precipitation, and sunlight exposure influence the biosynthesis and accumulation of bioactive compounds in the turmeric plant. The mountainous terrain and geology of the Northern regions likely result in distinct soil mineral profiles and nutrient availability. Factors such as the availability of specific nutrients, organic matter, and soil pH levels can significantly affect the plant's ability to produce and store different bioactive compounds.

Ethnic minority communities in the Northern Mountains may cultivate unique turmeric cultivars or landraces that have adapted to the local environment. The distinct geographic, climatic, and cultural factors of the Northern Mountain region likely contribute to the development of a unique curcuminoid composition in turmeric grown there, compared to turmeric from other parts of Vietnam or the world. This could have significant implications for the medicinal and culinary properties of this regionally specific turmeric. Nguyen Thi Kieu Oanh et al. (2021) collected turmeric samples from three main regions: the northern region (Lang Son), the central region (Nghe An), and the southern highlands (Lam Dong). The results showed that turmeric from Lang Son contained the highest concentration of curcumin (110.3 ± 50.0 µg/mg), demethoxycurcumin (46.7 ± 22.1 µg/mg) and bisdemethoxycurcumin (29.1 ± 10.4 µg/mg) [

4]. Similarly, in the case of turmeric from Nepal, the curcumin content was found to be higher in the samples cultivated in the southern region compared to those from the opposite geographical area. A sample from Chitwan, which is located in the Himalaya Mountain, was found to have about 165 mg/g of curcumin while the sample from Kalikot was found to have about 79 mg/g of curcumin in the turmeric extract [

5].

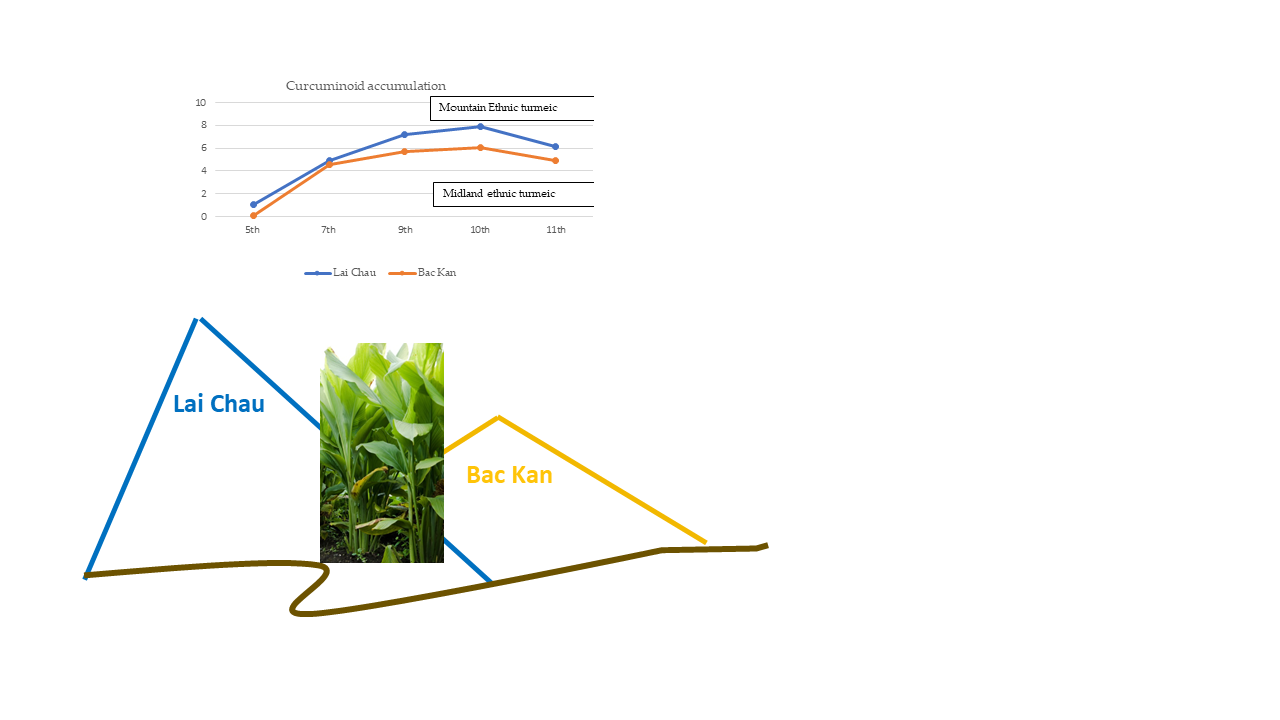

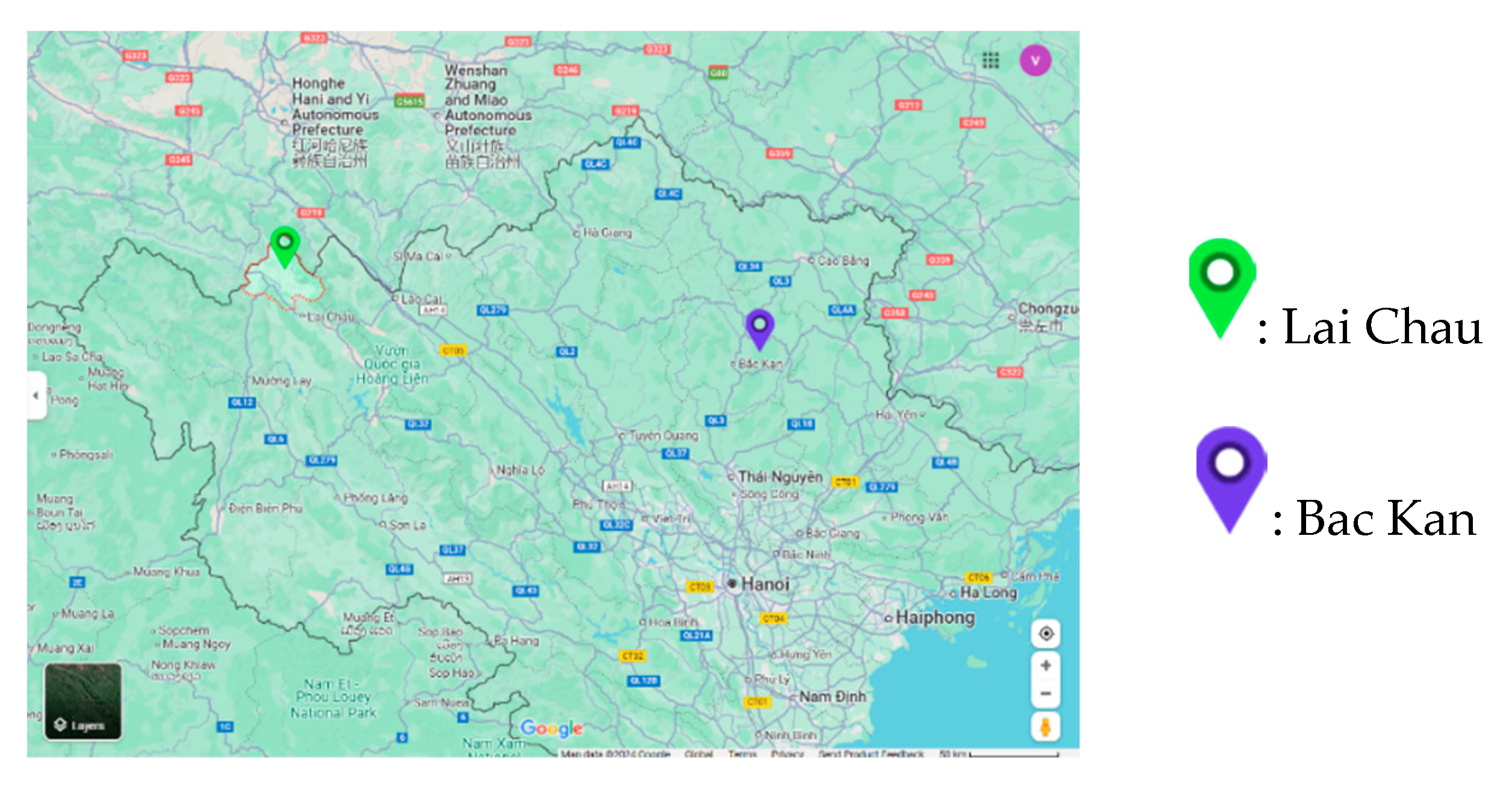

This study investigated the accumulation of metabolites, particularly the superior content of curcuminoids, in turmeric rhizomes grown by ethnic communities in the northern region of Vietnam. Samples were collected from traditional turmeric cultivation sites across Lai Chau and Bac Kan provinces. Cultivation practices, environmental factors, and genetic diversity are likely contributors to the observed differences in curcuminoid profiles. The findings suggest that traditional turmeric landraces from the Northern Mountains of Vietnam could serve as a valuable source of natural curcuminoid compounds, with potential applications in medicine, functional foods, and cosmetics. Further research is needed to optimize cultivation and post-harvest handling to maximize the curcuminoid yield from these ethnic turmeric varieties.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Turmeric Sampling

Ethnic turmeric rhizomes were collected from ethnic families in Lai Chau (Mountain) and Bac Kan (Midland) provinces in 2022 and 2023. Sampling took place in July, September, November, and December 2022, as well as in January 2023, corresponding to the 5th month, 7th month, 9th month, 10th month and 11th month of growing stage respectively.

Figure 1.

Turmeric sampling in Lai Chau and Bac Kan province.

Figure 1.

Turmeric sampling in Lai Chau and Bac Kan province.

2.2. Rhizome Extract

Methanolic extraction with the assistance of ultrasonic power followed the description of Aboshora W. et al. with a slight modification [

6]. 50g of sample was extracted by 200 mL methanol. The extraction was conducted at 50 °C in 1 hour in an ultrasonic processor having a frequency of 40 kHz (Qsonica, model C75E, USA). The extracts were then filtered and evaporated to dryness under reduced pressure at 50

oC in a rotary evaporator (Buchi Rotavapor, model R-114, Switzerland). At the end of the extraction, the extracts were re-dissolved in methanol to obtain stock solutions.

2.3. Qualitative Evaluation

Test for Tannins: Few drops of Ferric chloride (FeCl3) solution 10 % was added in the test tube containing the extract. The greenish-black color indicated a positive result (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia 5th edition, 2017).

Test for Flavonoids: The extract was taken in a test tube and mixed with a few drops of NaOH solution 10 %, making the solution has an intense yellow color. The addition of a few drops of hydrochloric acid HCl 10 % changed the solution to colorless, which indicated the presence of flavonoids (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia 5th edition, 2017).

Test for Saponin (Frothing Test): 1 mL of the extract was shaken with 5 mL of distilled water. Formation of froth lasting in 5 minutes showed the presence of saponin (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia 5th edition, 2017).

Test for Alkaloids: 1 mL of the extract was mixed with 1mL of HCl 2 % and steamed in the water bath for 2 minutes. Wagner’s reagent was added in. The appearance of a reddish-brown precipitate is indicative of alkaloids (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia 5th edition, 2017).

2.4. Quantitative Analysis

Volatile oils Distillation: The volatile oils were collected by the steam distillation apparatus in 3 hours and collected in dark containers, preserved at cool temperatures (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia 5th edition, 2017).

Total Polyphenol Content (TPC) Assay: 0.2 mL of the extract was mixed with 1 mL of distilled water. 1 mL of Folin Ciocalteu 10 % and 1.5 mL of Na2CO3 7.5 % (w/v) were then added in the test tube. The mixture was kept in the dark for 1 hour. The absorbance was measured by a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Apel PD-303S, Japan) at 760 nm against the blank. Gallic acid solution (20 ÷ 100 µg/mL) was used to make the calibration curve. Results were expressed as milligram gallic acid equivalent per 100g dry mass (mg GAE/100g DM)

Extraction of total curcuminoid: Turmeric rhizomes were sliced, dried at 50 °C for 3 days, and then powdered using a sieve with mesh size no. 60. A 50 mg sample of the dried, powdered rhizomes was combined with 1.5 mL of 80% ethanol solution. This mixture was refluxed for 5 hours at room temperature in the dark. Afterward, the mixture was centrifuged at 5000× g for 15 minutes and filtered through a 0.25 µm membrane (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia, 5th edition, 2017).

2.4.1. Determination of Total Curcuminoid

Standard curve: A stock solution of curcuminoid standard was prepared by dissolving 10mg of curcuminoid in 96% ethanol, then making up the volume to 25 m. The stock curcumin solution was then diluted 100 times, and the absorbance was scanned at different wavelengths from 400 nm to 500 nm to determine the maximum absorption wave-length. From the stock standard solution, a series of standard curcuminoid solutions in methanol were prepared, and a standard curve was created to show the relationship between curcuminoid concentrations and absorbance (Vietnam Pharmacopoeia, 5th edition, 2017).

Approximately 2–3 g of the test sample was accurately weighed and diluted with 96% ethanol. Sample measurements were performed using UV-VIS spectroscopy at the maximum absorption wavelength of 420 nm. The curcuminoid content in the test sample was then calculated using the following formula:

where C

t was curcuminoid concentration in the sample (μg/g); C

dc: curcuminoid concentration from the standard curve (μg/mL); K

t: dilution factor, V: diluted solvent (mL); m

t: weight of the sample (g)

2.4.2. Determination of Curcuminoid Composition

Curcuminoid composition (curcumin, DMC, and BMC) was measured by HPLC–PDA (Shimadzu, FIRI.F.004) with PDA detection at 424 nm. The mobile phases consisted of Acetonitrile: H₂O (95:5) and 0.1% H₃PO₄, with a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The column temperature was maintained at 35°C, and the total injection volume was set to 10 µL [

7]

Soil’s analysis: Soil samples were collected according to the standard method of TCVN 7538-6:2010. Parameters such as pH (KCl), organic carbon (OC), total nitrogen (N), total phosphorus (P), and total potassium (K) were analyzed according to TCVN 5979:2007, TCVN 8941:2011, TCVN 6498:1999, TCVN 4052:1985, and TCVN 8660:2011, respectively.

Irrigation water analysis: The pH of the irrigation water was measured in accordance with the national technical regulation on water quality for irrigated agriculture (QCVN 39:2011/BTNMT).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The experiments were conducted with three replicates, and the data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, followed by the Tukey test. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). All statistical analyses were performed using XLSTAT 2024.4.0.1424.

3. Results

3.1. Qualitative Test

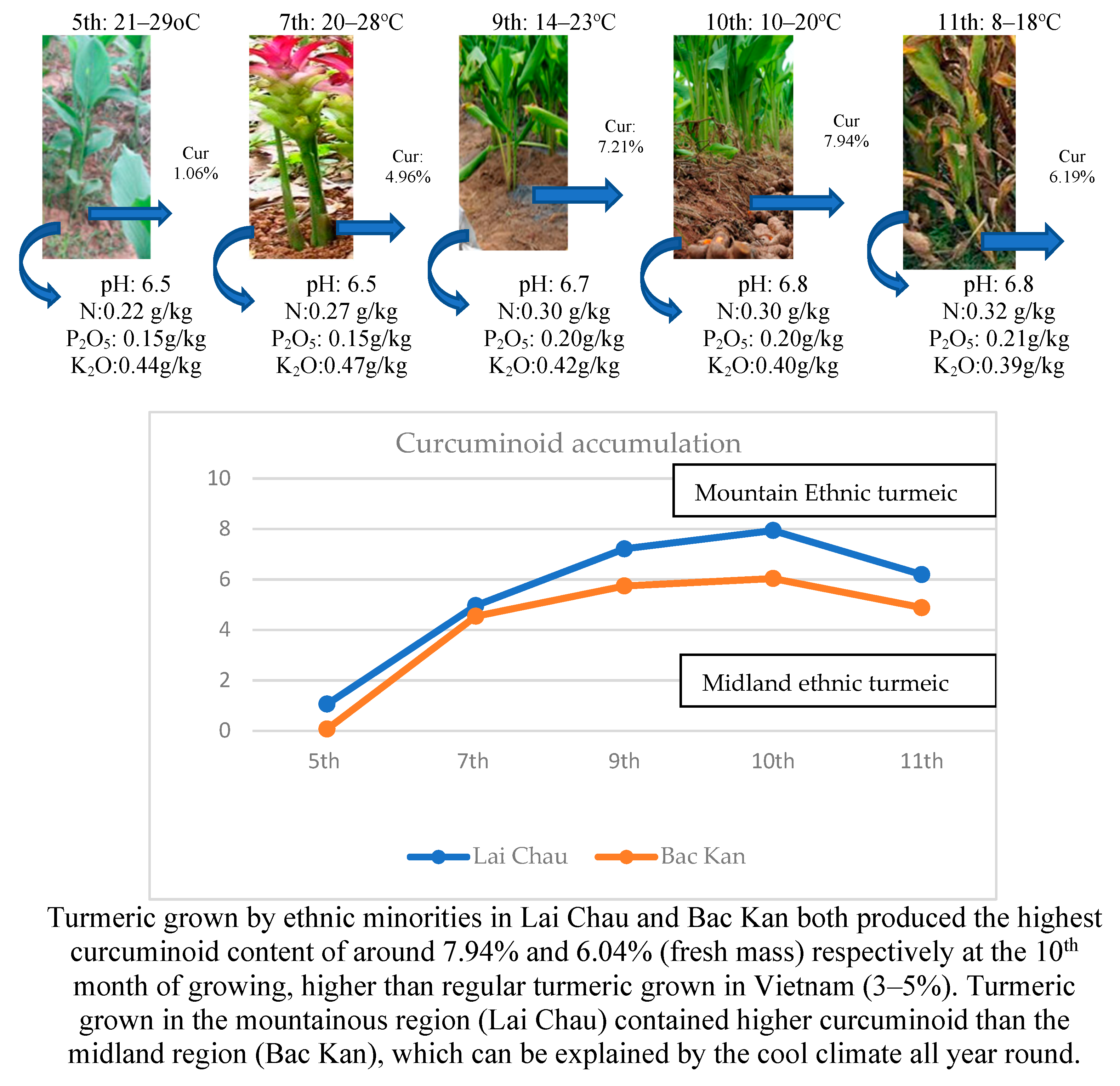

Turmeric is planted in February and is usually harvested 9 months later. Ethnic minorities harvest it sporadically in November, December, and the first month of the new year for various traditional rituals and folk medicines, where it symbolizes health, prosperity, and protection against evil spirits.

The secondary metabolic content in turmeric includes various bioactive compounds such as alkaloids, saponins, flavonoids, tannins, sterols, phytic acid, and phenols. A previous report indicated that turmeric contains 0.76% alkaloids, 0.45% saponins, 1.08% tannins, 0.03% sterols, 0.82% phytic acid, 0.40% flavonoids, and 0.08% phenols, all of which contribute to turmeric's therapeutic properties, including its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial effects [

8]. A qualitative assessment of secondary metabolites in turmeric rhizomes is presented in

Table 1.

The results showed that Tanin, Flavonoid, Saponin and Alkaloid increased over time, from the 5th month to the 9th month, in both Lai Chau and Bac Kan provinces. When harvested after 9 months, some secondary active ingredients in traditional turmeric increased such as tannins and polyphenols in the 10th month, and decreased by the 11th month. However, by this time, there was a slight decline in two of the compounds (Flavonoid and Alkaloid) in Bac Kan, while Lai Chau maintained the levels across all parameters. This could indicate that the optimal growth period for maximizing these phytochemical compounds in the ethnic turmeric is between the 10th and 11th months, instead of the 9th month for the turmeric grown of the delta area.

3.2. Quantitative Test

3.2.1. Volatile oil and Rhizome Extract Quantitatively Determination

The amount of volatile oil and extract collected is present in

Table 2.

Volatile oil and the total extract increased over time, reaching the highest concentration in the 9th month and 10th month, respectively in both Lai Chau and Bac Kan provinces. The higher volatile oil and total extract percentages in Lai Chau compared to Bac Kan suggested that the growing conditions or cultivation practices or turmeric species in Lai Chau could be more favorable for the secondary metabolites’ formation in turmeric. The slight decline in both parameters in the 11th month (January, 2023) could indicate that the plants have reached their optimal growth and that the quality or yield may start to decrease after this point. Further investigation would be needed to determine the specific factors that contribute to the differences observed between the two provinces, such as environmental conditions, soil characteristics, agricultural inputs, and harvesting methods. Understanding these factors could help optimize the cultivation and harvesting of the plants to maximize the production of volatile oils and total extracts.

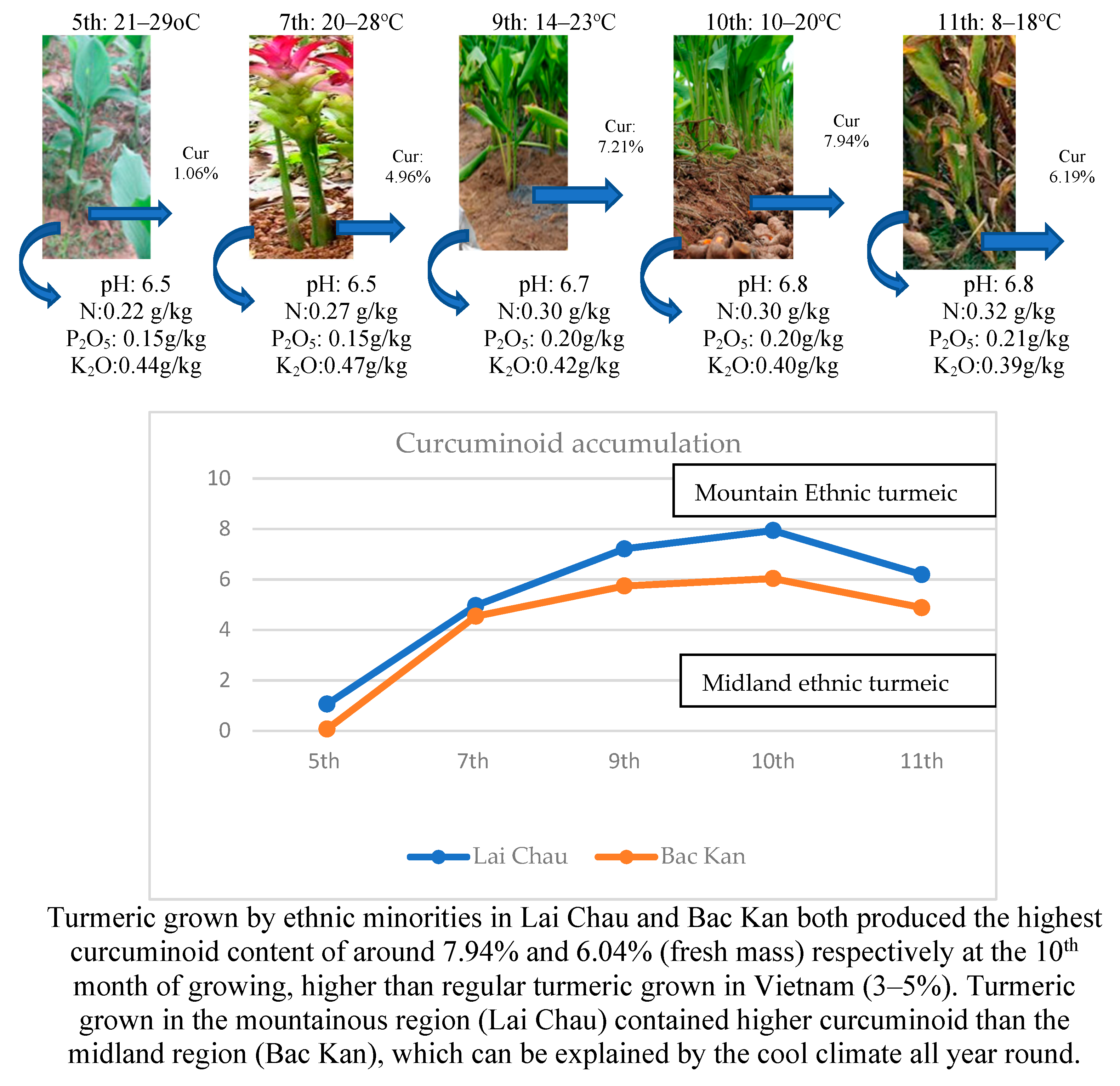

3.2.2. Curcuminoid Quantitatively Determination

Curcuminoids, the most important secondary metabolite of turmeric which is known for their potent anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, making them valuable in the prevention and treatment of various diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. In general, fresh turmeric rhizomes typically contain about 2–5% curcuminoids by weight, but this can vary based on factors such as the variety of turmeric and growing conditions. Specifically, during heat treatment, the curcuminoid concentration in oven-dried turmeric was 0.76 ± 0.06%

w/

w, while in freeze-dried turmeric, it was 0.76 ± 0.04%

w/

w [

9]. In this study, the maximum content of curcuminoid in fresh ethnic turmeric could reach up to 7–8% (

Table 3). Understanding how these compounds accumulate in ethnic turmeric (can preserving traditional agricultural practices and knowledge that these communities possess, helps enhance the value of agricultural products of ethnic minorities as well as regional.

The total curcuminoid content (Cur + DMC + BMC) increased over time, with the highest levels observed in the 10th month (December 2022) for both Lai Chau (7.94%) and Bac Kan (6.04%), then slightly decreased slightly in the 1th month (January 2023), but remained high compared to the earlier growth months. The Cur:DMC:BMC ratio indicated higher DMC and BMC content in the Lai Chau samples compared to the Bac Kan samples.

In general comparison, turmeric from Lai Chau consistently had higher curcuminoid levels compared to Bac Kan throughout the growing season. Then the climate of Lai Chau and Bac Kan was investigated and the results is presented in

Table 4.

Both Lai Chau (Phong Tho) and Bac Kan (Na Ri) have a subtropical climate with warm temperatures, acidic soils with low nutrient levels, and slightly acidic irrigation water. These environmental factors should be taken into account when developing agricultural practices and selecting suitable crops for these regions. Among the varieties of agricultural products and spices in mountainous areas, turmeric is suitable for eroded and barren soils because it has a dense, fibrous root system that helps stabilize the soil and prevent erosion, especially on sloping or degraded lands; it can adapt to a wide range of soil types, including acidic, sandy, or clay-based soils.

3.2.3. Curcuminoid Accumulation in Lai Chau’s Turmeric Rhizome

4. Discussion

This finding suggests that the optimal time for harvesting turmeric in mountain by ethnic people to maximize the bioactive compounds may not be confined to the traditional of 6.5 to 9-month mark [

10], as commonly practiced in delta areas and in the region. This study indicates that the window after 9

th and 10

th months of growth might be the ideal window for the highest concentrations of tannins and polyphenols, which could be indicative of a peak in therapeutic potential. This is an important consideration for both local agricultural practices and for the traditional medicinal use of turmeric, as ethnic minorities harvest turmeric in accordance with rituals and beliefs rather than strictly agricultural criteria. Interestingly, the study also highlights regional differences in the accumulation of these secondary metabolites. While both Lai Chau and Bac Kan exhibit increases in bioactive compounds over time, Lai Chau (mountain area) appears to maintain relatively stable levels of flavonoids, alkaloids, and other metabolites through the 9

th and 10

th months, while Bac Kan (midland) shows a slight decline in flavonoids and alkaloids by the 11

th month.

The quantitative analysis of volatile oil and rhizome extract in turmeric provides valuable insights into the dynamic changes in the chemical composition of this plant over the course of its growth cycle. The results summarized in

Table 2 demonstrate clear patterns in the accumulation of both volatile oil and total extract, with noticeable peaks in concentration observed in the 9

th to 10

th months of growth. In Indian samples, harvested in the 10

th month, essential oils were found at the range from 3.05 to 4.45%, which was much lower than that in Vietnamese ethnic turmeric (6.20%) [

11]

As shown in

Table 3, the concentration of curcuminoids increased steadily over the growing period, reaching its peak in the 10

th month (December 2022) for both Lai Chau (7.94%) and Bac Kan (6.04%). This indicates that curcuminoid accumulation in turmeric rhizomes is influenced by the plant's maturation, with the highest concentrations observed just before or at the end of the typical growing season. These findings align with other studies that report similar trends in curcuminoid levels, with peak levels observed towards the end of the growing season [

12]. In this study, from the 9

th to 10

th month was the optimal window for harvesting turmeric to obtain the highest curcuminoid content.

Interestingly, after the 10th month, there is a slight decline in curcuminoid levels in both regions, with a decrease to 6.19% in Lai Chau and 4.88% in Bac Kan by the 11

th month. This decline may indicate that turmeric has reached the peak of its metabolic processes for curcuminoid production, and after this point, the plant begins to allocate its energy toward other physiological functions, such as reproduction or dormancy. Despite the slight decrease in the 11

th month, the curcuminoid levels remained relatively high compared to earlier growth stages, highlighting the persistence of these compounds even as the plant nears the end of its growing cycle. To study more closely on metabolomics and biological activities of curcuminoid the ratio Cur:DMC:BMC usually is determined. With 12 Indian turmeric samples, the curcumin, DMC, and BMC contents were 52–63%, 19–27%, 18–28%, respectively, and the ratio Cur:DMC:BMC was 6:2:1 [

13,

14].This ratio of ethnic turmeric’s curcuminoid was further elucidated, which confirmed that turmeric in Lai Chau consistently possessed higher levels of DMC and BMC compared to Bac Kan throughout the growing season. And this ratio in curcuminoids obtained from Lai Chau turmeric is quite close to the ratio of some good quality Indian turmeric varieties, which was 7:2:1 for the samples of the 10

th of harvest. One possible explanation for the higher DMC and BMC content in Lai Chau could be the region's unique environmental conditions, such as temperature, soil composition, and irrigation practices. These factors are discussed further below and could offer insights into why turmeric from Lai Chau has a superior curcuminoid profile compared to Bac Kan. In the Indian samples.

To support the observation in high secondary metabolites, some main key attributes of weather, soil and water have been investigated as well. Lai Chau, which is located in a mountainous area, may benefit from a cooler (21–27°C), in contrast, Bac Kan (21–29°C), being situated in a more temperate region, might have different soil types or climatic conditions that affect the synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in some plants. Soil characteristics also appear to contribute to the observed differences in curcuminoid content. Both Lai Chau and Bac Kan have soils mixed with clay and exhibit slightly acidic pH values (4.6 and 4.5 for Lai Chau and Bac Kan, respectively). While both regions have low nutrient levels (as indicated by the low levels of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium), the specific nutrient availability and soil composition in Lai Chau may be more conducive to the production of curcuminoids. The irrigation water in both regions has a pH of around 6.8 (Lai Chau) and 6.3 (Bac Kan), which is slightly acidic but within the optimal range for turmeric cultivation [

10].

5. Conclusions

The exploration of turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) cultivation among ethnic minority communities in the Northern Mountains of Vietnam reveals a multifaceted relationship between traditional agricultural practices, environmental factors, and the unique phytochemical properties of this vital crop. As highlighted, turmeric serves not only as a spice but also as a cultural emblem deeply embedded in the rituals and daily lives of various ethnic groups such as the Hmong, Dao, Thai, and Muong people. This underscores the significance of preserving traditional knowledge and practices that contribute to both cultural identity and sustainable agriculture.

In considering future implications, there is substantial potential for these unique landraces of turmeric to contribute significantly to various sectors including medicine, functional foods, and cosmetics. The high curcuminoids; content identified (6–8%) could pave the way for further research into their therapeutic benefits and commercial applications. However, it is crucial to approach this exploration with sensitivity towards indigenous practices and ensure that any commercialization efforts benefit local communities without undermining their cultural heritage.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. N.T.M.T.: Conceptualization; sampling; methodology; formal analysis; writing—original draft. N.T.P.: Conceptualization, supervision; writing—review and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by The Ministry Of Science and Technology of Vietnam, NĐT/BY/22/03 .

Data Availability Statement

Data will be provided upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Nguyen Chi Long, Son La province, for contacting ethnic people in this research work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Huu Tien, N.; Quang Phap, T.; Thi Duyen, N.; Wim, B. First report of Rotylenchulus reniformis infecting turmeric in Vietnam and consequent damage. J. Nematol 2020, 52, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Surjit, R.; Anusri Mahalakshmi, B.; Shalini, E.; Shubha Shree, M. Natural Dyes in Traditional Textiles: A Gateway to Sustainability. In Natural Dyes and Sustainability; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023.

- Charles C. D. and Patric Choisy. Review: Medicinal plants meet modern biodiversity science. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 158–173. [CrossRef]

- Kieu-Oanh, N.T.; Hoang-Giang, D.; Ngoc-Tu, D.; Tien-Dat, N.; Quang-Trung, N. Geographical Discrimination of Curcuma longa L. in Vietnam Based on LC-HRMS Metabolomics. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2021, 16, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Poudel, A.; Pandey, J.; Lee, H.K. Geographical Discrimination in Curcuminoids Content of Turmeric Assessed by Rapid UPLC-DAD Validated Analytical Method. Molecules 2019, 24, 1805. [CrossRef]

- Aboshora, W.; Zhang, L.; Mohammed, D.; Meng, Q.; Sun, Q.; Li, J.; Nabil, Q. M Al-Haj and Al-Farga A. Effect of extraction method and solvent power on polyphenol and flavonoid levels in Hyphaene thebaica L. Mart (Arecaceae) (Doum) fruit, and its antioxidant and antibacterial activities. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 2014, 13, 2057–2063. [CrossRef]

- Jangle, R.D.; Thorat, B.N. Reversed-phase High-performance Liquid Chromatography Method for Analysis of Curcuminoids and Curcuminoid-loaded Liposome Formulation. Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 75, 60–66. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, H.M. Turmeric polyphenols: A comprehensive review. Integr Food Nutr. Metab. 2019, 6, 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Hadi, S.; AN Artanti, A.N.; Rinanto, Y.; Wahyuni DS, C. Curcuminoid content of Curcuma longa L. and Curcuma xanthorrhiza rhizome based on drying method with NMR and HPLC-UVD. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng 2018, 349 012058.

- Srinivasan, V.; Praveena, R.; Dinesh, R.; Senthilkumar, C.M.; Aarthi, R.; Usha Malini, C.; Nirmal Babu, K. Turmeric—Good Agricultural Practice; Indian Institute of Spices Research, Kerala, India, 2019; pp. 2–16.

- Dhanalakshmi, K.G.; Jaganmohanrao, L. Comparison of chemical composition and antioxidant potential of volatile oil from fresh, dried and cured turmeric (Curcuma longa) rhizomes. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 38, 124–131.

- Kobayashi, T.; Miyazaki, A.; Matsuzawa, A.; Kuroki, Y.; Shimamura, T.; Yoshida, T.; Yamamoto, Y. Change in Curcumin Content of Rhizome in Turmeric and Yellow Zedoary. Jpn. J. Crop Sci. 2010, 79, 10–15. [CrossRef]

- Singh, J.; Shahidullah, T.F.; Devanand, L.L. Comparative Investigation of Untargeted and Targeted Metabolomics in Turmeric Dietary Supplements and Rhizomes. Food 2025, 14, 7. [CrossRef]

- Amalraj, A.; Pius, A.; Sreerag Gopi, S.; Gopi, S. Biological activities of curcuminoids, other biomolecules from turmeric and their derivatives: A review. J. Tradit. Complement. Med. 2017, 7, 205–233. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).