1. Introduction

Carrot (

Daucus carota L.) is one of the most widely consumed root vegetables worldwide and is well recognized for its rich composition of carotenoids, phenolic compounds, and dietary fiber, which contribute to its antioxidant and health-promoting effects [

1,

2]. Although the edible roots and their processing residues are widely utilized as food and industrial materials [

3,

4], the leafy and stem portions are generally discarded after harvest, and a large amount still remains underutilized [

5]. This underuse not only generates agricultural waste but also represents a loss of potentially valuable bioresources.

Many by-products of root vegetables that are often discarded after harvest have been reported to contain abundant nutrients and bioactive compounds [

5]. Among them, carrot leaves are rich in phenolic acids and flavonoids, which exhibit notable antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties [

6]. However, previous studies have mainly focused on the characteristics of individual parts, such as root or leaf analyses and cultivar comparisons [

6,

7], and comparative evaluations of biological activities between underground and aerial parts remain very limited. This highlights the need for a systematic comparison of the physiological activities among different parts of carrots.

The immune system plays a crucial role in maintaining homeostasis and defending the host against pathogens [

8]. In particular, macrophages play a pivotal role in immune signaling and contribute significantly to innate immunity [

9]. Macrophages regulate immune responses by producing various mediators such as nitric oxide (NO) and cytokines, which play essential roles in host defense and immune regulation [

10]. The immunoregulatory functions of macrophages are known to be influenced by various bioactive compounds [

11]. Natural products, in particular, have attracted increasing attention because of their broad immunomodulatory potential, and numerous studies have explored their roles in enhancing immune regulation and suppressing inflammation [

12]. Consequently, plant extracts and their derived bioactive compounds have been widely employed to evaluate their immune-related activities, demonstrating that various bioactive constituents can modulate immune responses through macrophage-mediated mechanisms [

13,

14].

Therefore, this study aimed to comparatively evaluate the antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities of carrot extracts obtained from underground (roots) and aerial (leaves and stems) parts to elucidate their biological differences. Furthermore, this work seeks to enhance the functional value and utilization of underutilized parts, thereby promoting their potential application as natural functional food materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Potassium persulfate, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) (ABTS), 2,2′-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), ascorbic acid, sodium carbonate, 2 N Folin–Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent, gallic acid, and aluminum nitrate nonahydrate were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), fetal bovine serum (FBS), and an antibiotic–antimycotic mixture were purchased from GenDEPOT (Katy, TX, USA). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), soluble 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT), and the Griess reagent were also obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits for cytokine determination were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

2.2. Preparation of Extracts

Dried powders of carrot aerial and underground parts were each extracted with hot water for 1 h and with 50% ethanol. The extracts were filtered through filter paper, concentrated under reduced pressure, and freeze-dried to obtain powder forms, which were stored for further experiments. The resulting extracts were designated as AS-W (aerial part, hot-water extract), AS-E (aerial part, 50% ethanol extract), UG-W (underground part, hot-water extract), and UG-E (underground part, 50% ethanol extract).

2.3. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

Total phenolic content was measured using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent. Each extract was mixed with 2 N Folin–Ciocalteu’s phenol reagent and 2% Na2CO3 solution, incubated in the dark for 30 min, and the absorbance was recorded at 750 nm using a microplate reader (FilterMax F5; Molecular Devices, San Francisco, CA, USA). Gallic acid was used as the standard, and results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE).

2.4. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

Total flavonoid content was determined by the aluminum nitrate colorimetric method. The extract was sequentially mixed with 80% ethanol, 10% aluminum nitrate, and 1 M potassium acetate, incubated for 30 min in the dark, and the absorbance was measured at 415 nm. Quercetin served as the standard, and results were expressed as quercetin equivalents (QE).

2.5. Radical Scavenging Activity (ABTS and DPPH Assays)

For the ABTS assay, a solution of 7.4 mM ABTS and 2.6 mM potassium persulfate was prepared and kept at 4 °C for 24 h in the dark to generate ABTS+ radicals. The resulting solution was diluted with distilled water to obtain the working ABTS solution. The extract was serially diluted to final concentrations of 1, 2, 4, and 8 mg/mL, mixed with the working solution, and incubated for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. The absorbance was then measured at 734 nm using a microplate reader.

For the DPPH assay, a 2 mM DPPH solution was prepared in 80% methanol and diluted to a suitable working concentration. The extract was adjusted to the same concentration range as used for the ABTS assay and reacted with the DPPH working solution for 30 min in the dark at room temperature. Absorbance was recorded at 514 nm using the same instrument.

The radical-scavenging capacity was expressed as the IC50 value, representing the concentration of extract required to reduce radical activity by 50%. The IC50 values were calculated from the linear regression equation, IC50=(50-b)/a.

2.6. Cell Culture and Cytotoxicity

RAW 264.7 cells obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea) were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotic–antimycotic solution at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2. When cell confluence reached approximately 90%, the cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well. For the immunostimulatory experiment, the cells were treated with four carrot extracts (AS-W, AS-E, UG-W, and UG-E) at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL for 24 h. For the anti-inflammatory experiment, inflammation was induced by co-treatment with LPS (1 μg/mL) and each extract at the same concentrations for 24 h; an LPS-treated group served as the positive control. After treatment, the culture medium was replaced with MTT solution (0.5 mg/mL) and incubated for 3 h. The resulting formazan crystals were dissolved in DMSO, and absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

2.7. Nitric Oxide (NO) Assay

RAW 264.7 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 2 × 104 cells/well and treated with carrot extracts (AS-W, AS-E, UG-W, and UG-E) at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL for 24 h. For the immunostimulatory experiment, cells were treated with the extracts alone, whereas for the anti-inflammatory experiment, inflammation was induced by co-treatment with LPS (1 μg/mL) and each extract. An LPS-treated group served as the positive control. After incubation, the culture supernatants were collected and mixed with an equal volume of Griess reagent. The absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a microplate reader.

2.8. Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

RAW 264.7 cells were cultured and treated with carrot extracts (AS-W, AS-E, UG-W, and UG-E) at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL, with or without LPS (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. The culture supernatants were collected to assess the effects of the extracts on cytokine production in macrophages. The levels of interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor- α (TNF-α) were quantified using ELISA kits (R&D Systems, according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 29 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Differences among multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, and comparisons between two groups were evaluated using an independent samples t-test. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05.

3. Results

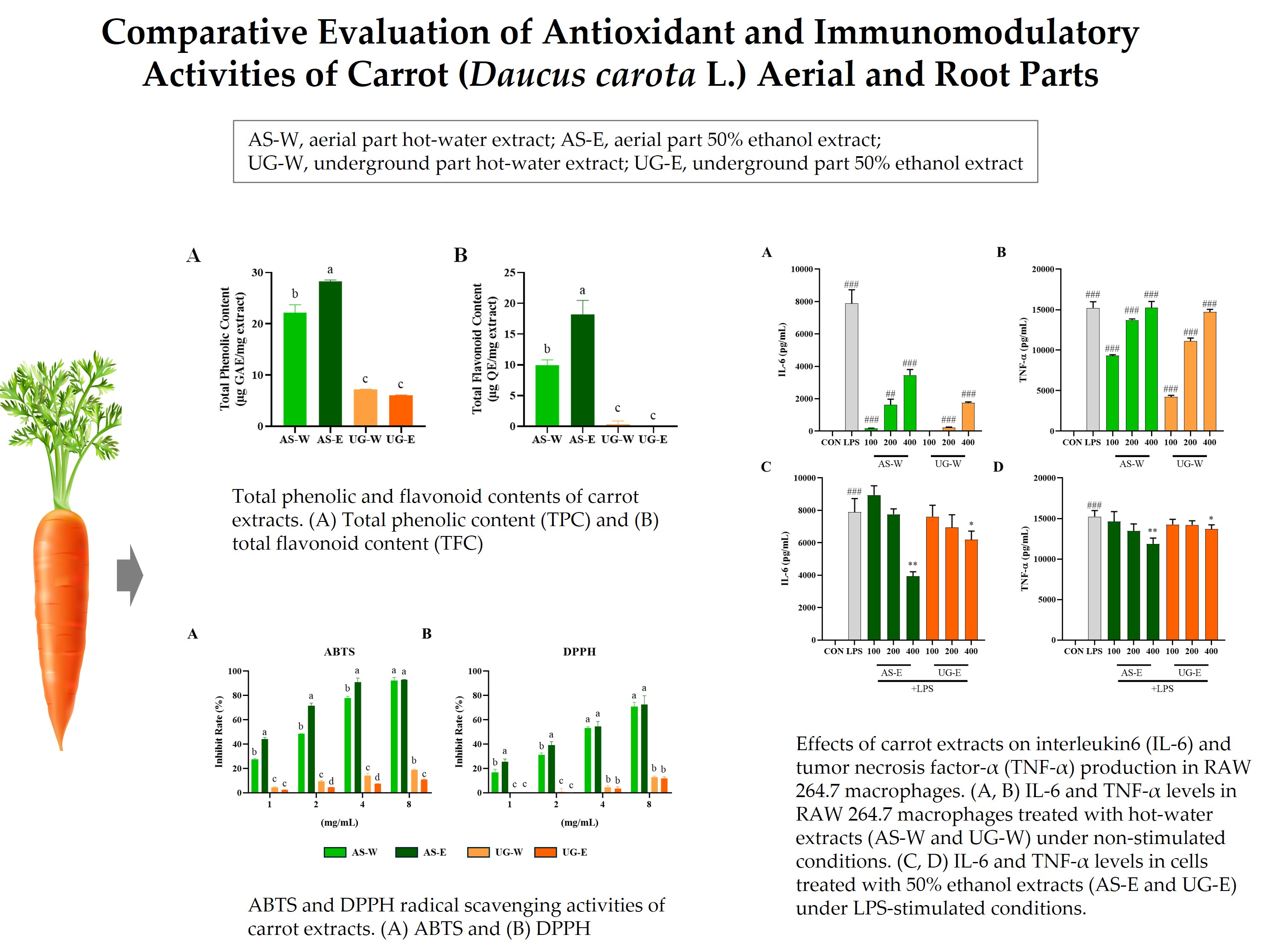

3.1. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents of Carrot Extracts

The total phenolic and flavonoid contents are key indicators of antioxidant capacity, as these compounds contribute to radical scavenging [

15]. The total phenolic and flavonoid contents of carrot extracts were evaluated to compare the distribution of bioactive compounds between the aerial and underground parts (

Figure 1). Both TPC and TFC were markedly higher in the aerial part extracts than in the underground ones. Among the four extracts, AS-E exhibited the highest TPC and TFC values, followed by AS-W, while both underground extracts (UG-W and UG-E) showed comparatively lower levels. These findings indicate that the aerial parts of carrots, particularly those extracted with ethanol, are richer in polyphenolic and flavonoid compounds, which may contribute to their stronger antioxidant potential observed in subsequent analyses.

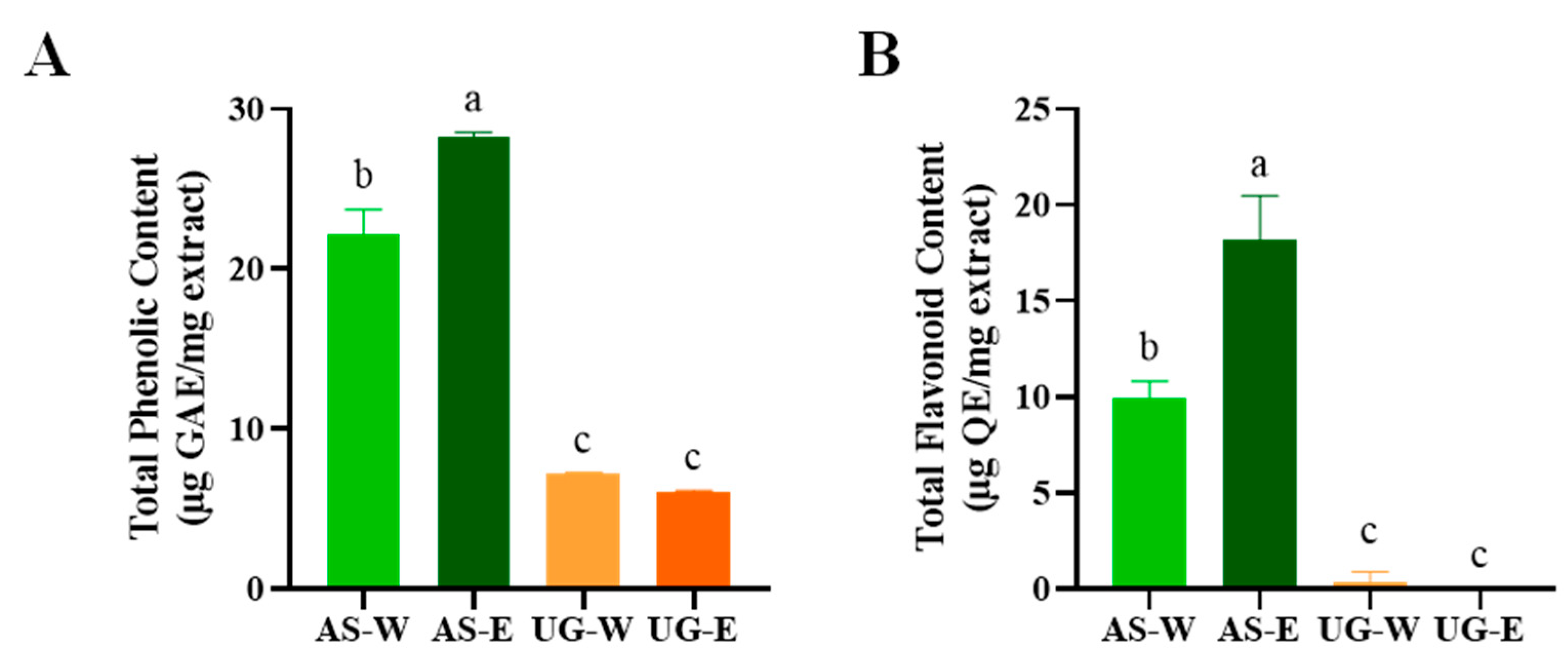

3.2. Antioxidant Effect of Carrot Extracts

Both ABTS and DPPH assays are widely used to evaluate the free radical scavenging activity of plant extracts, reflecting their overall antioxidant potential [

16]. The antioxidant capacities of carrot aerial and underground part extracts were evaluated using ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging assays (

Figure 2). Both assays showed that the aerial part extracts possessed significantly stronger radical scavenging activity than the underground part extracts. In particular, AS-E exhibited the highest scavenging capacity, followed by AS-W. In contrast, both underground extracts (UG-W and UG-E) displayed relatively low activities. These findings suggest that the enhanced antioxidant properties of the aerial extracts may be attributed to their higher polyphenol and flavonoid levels, consistent with the TPC and TFC results.

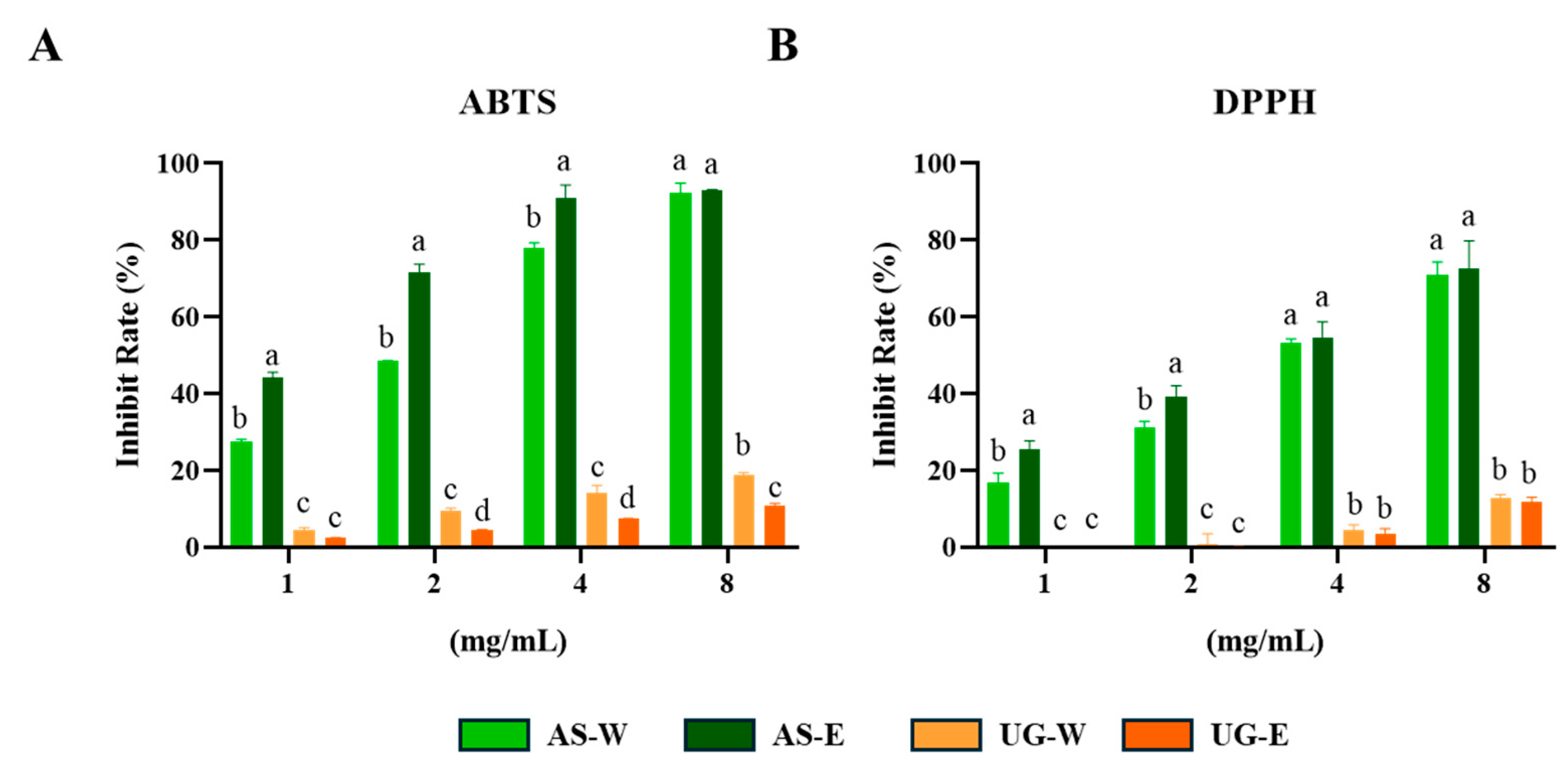

3.3. Cytotoxicity of Carrot Extracts in RAW 264.7 Cells

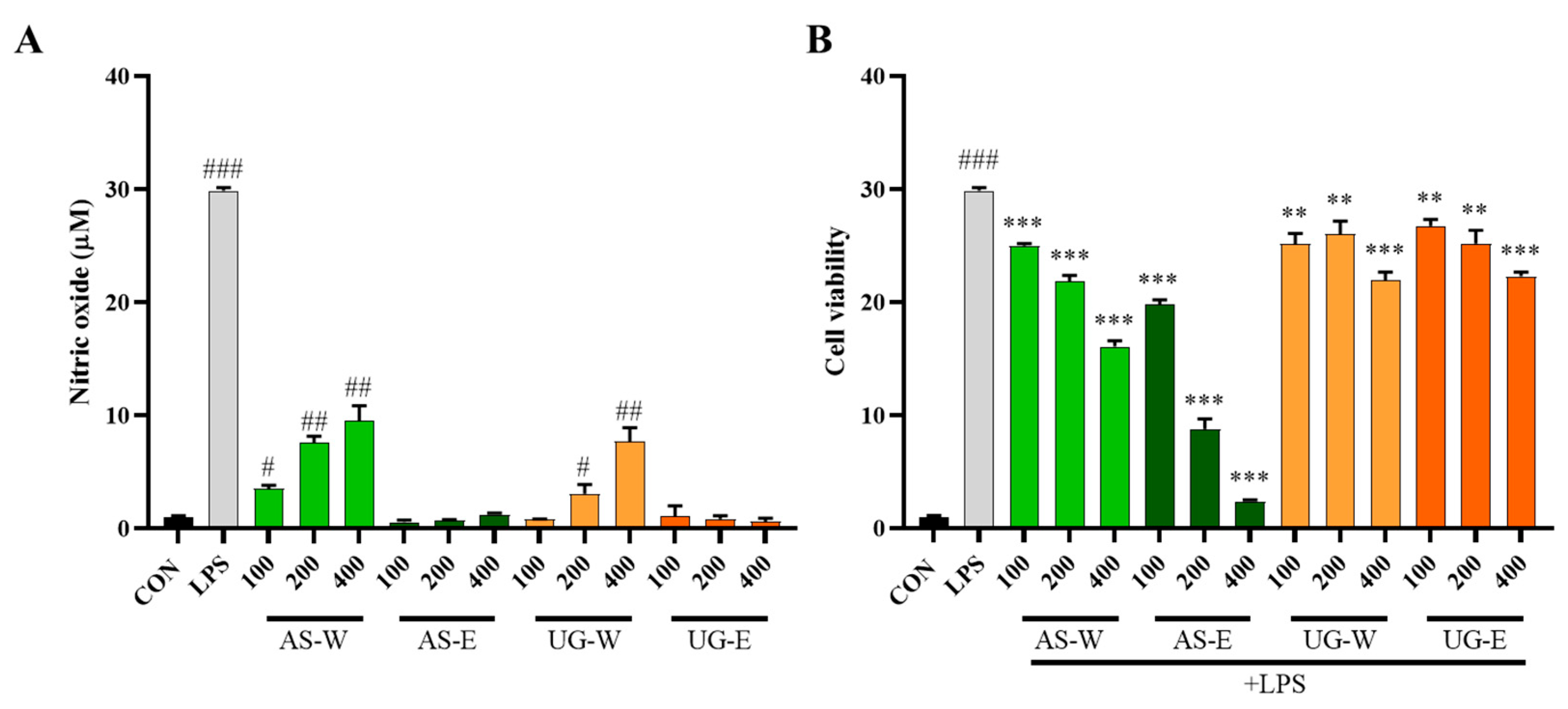

The cytotoxicity of carrot extracts was assessed in RAW 264.7 macrophages using the MTT assay (

Figure 3). All extracts (AS-W, AS-E, UG-W, and UG-E) showed no cytotoxicity at concentrations up to 400 μg/mL, and cell viability remained above 90%. Moreover, co-treatment with LPS (1 μg/mL) did not affect cell viability, indicating that neither the extracts nor their combination with LPS-exerted any cytotoxic effects on macrophages.

3.4. Effects of Carrot Extracts on NO Production in RAW 264.7 Cells

Nitric oxide is a major signaling molecule produced by macrophages during immune activation [

17]. Nitric oxide production was measured to evaluate the immunostimulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of carrot extracts (

Figure 4). Under non-stimulated conditions (without LPS), the hot-water extracts (AS-W and UG-W) markedly enhanced NO production compared with the control group, indicating immune-stimulatory activity. In contrast, the ethanol extracts (AS-E and UG-E) showed minimal effects, suggesting that water-soluble components such as polysaccharides may be responsible for macrophage activation. Under LPS-stimulated conditions, NO production was substantially increased by LPS treatment; however, co-treatment with the aerial part extracts significantly reduced NO levels in a dose-dependent manner. In particular, AS-E exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect, followed by AS-W, whereas both underground part extracts (UG-W and UG-E) showed weak suppression. These results indicate that the aerial part, especially the ethanol extract rich in phenolic compounds, possesses potent anti-inflammatory activity through inhibition of NO production.

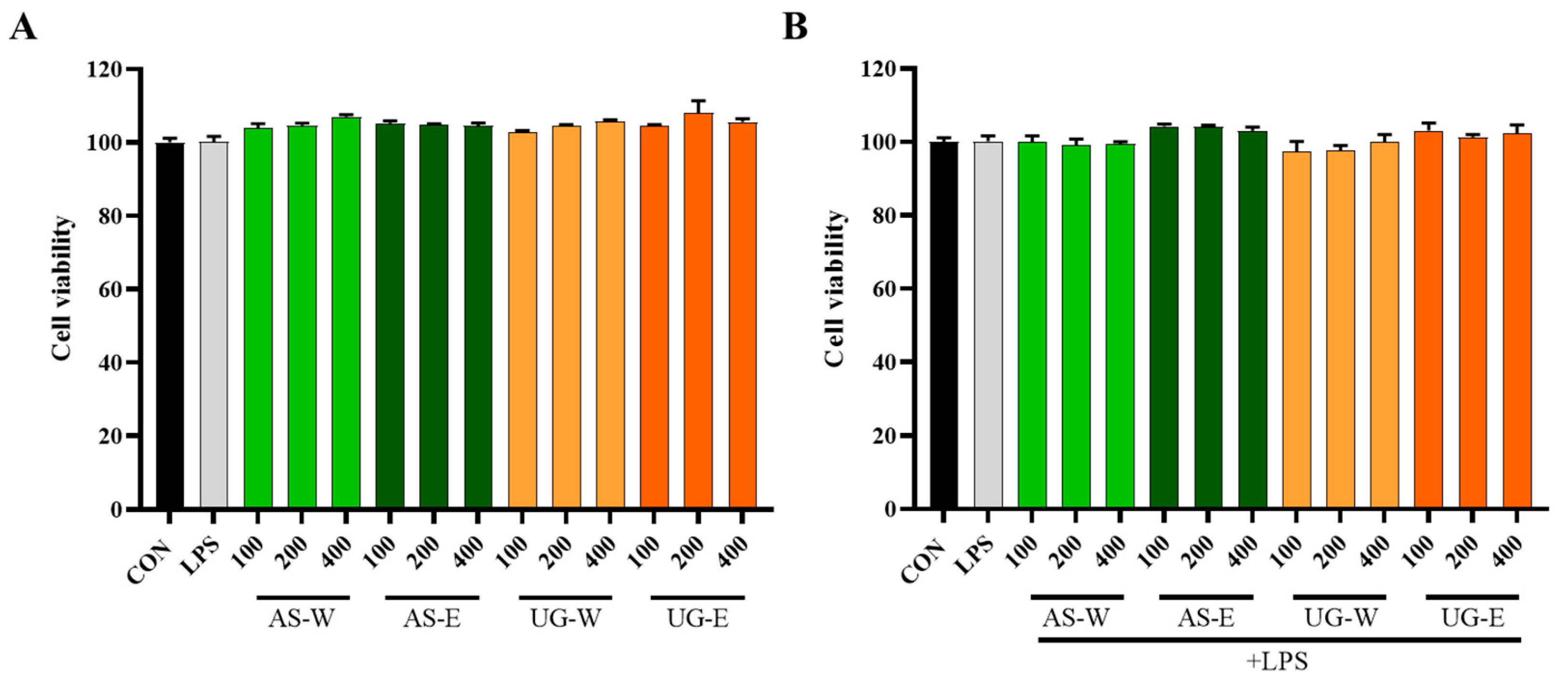

3.5. Effects of Carrot Extracts on Cytokine (IL-6 and TNF-α) Production in RAW 264.7 Cells

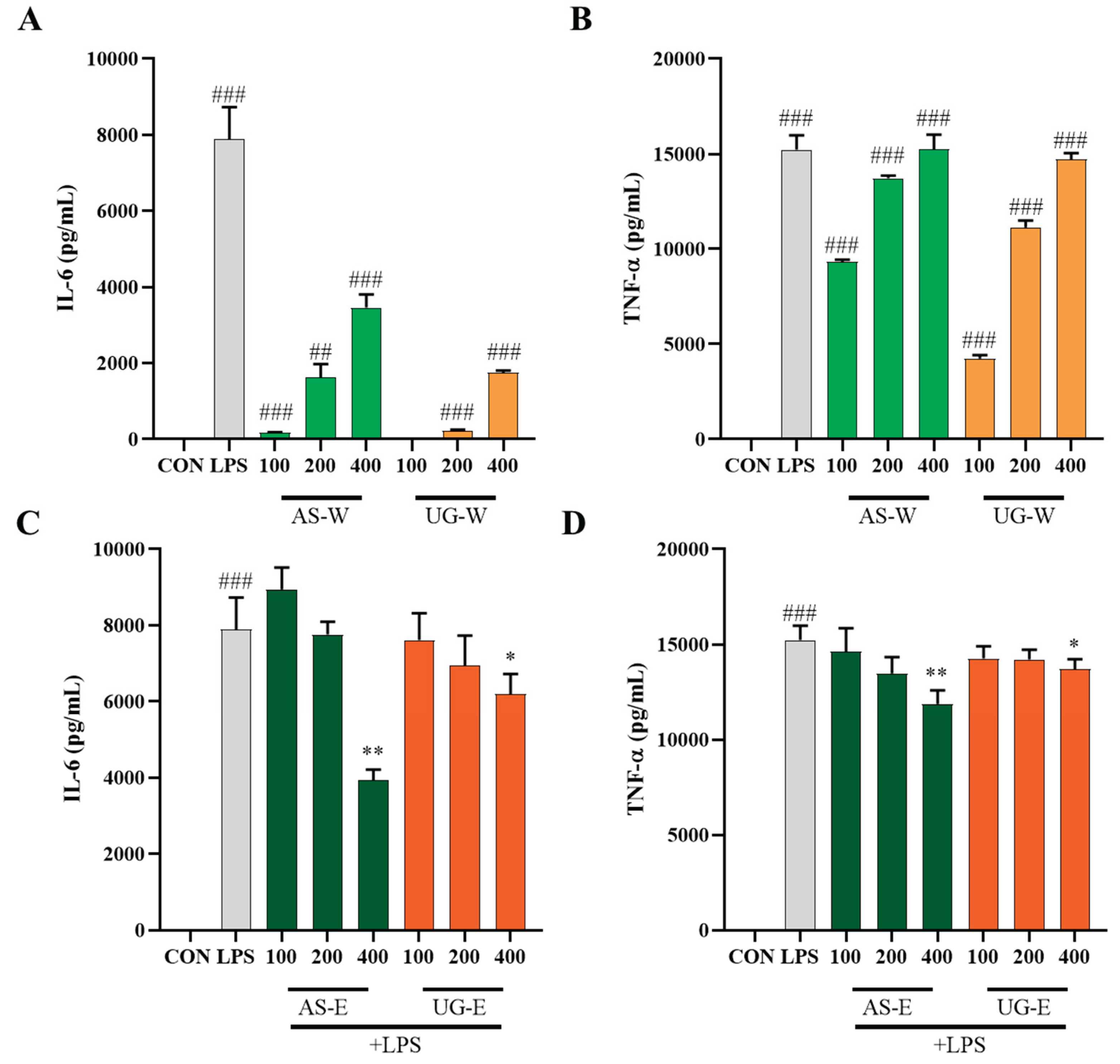

IL-6 and TNF-α are representative pro-inflammatory cytokines released by activated macrophages, serving as biomarkers for immune and inflammatory modulation [

18]. To further investigate the immunomodulatory effects of carrot extracts, the levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were measured in RAW 264.7 macrophages under non-stimulated and LPS-stimulated conditions (

Figure 5). Under non-stimulated conditions (without LPS), treatment with the hot-water extracts (AS-W and UG-W) significantly increased the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α compared with the control, indicating macrophage activation and immune-enhancing effects. Among them, AS-W showed the strongest stimulatory activity, consistent with the results of NO production. Under LPS-stimulated conditions, cytokine levels were markedly elevated by LPS treatment, whereas co-treatment with the ethanol extracts (AS-E and UG-E) notably suppressed IL-6 and TNF-α production in a concentration-dependent manner. In particular, AS-E exhibited the most pronounced inhibition, suggesting that phenolic-rich compounds from the aerial part contribute to anti-inflammatory effects by downregulating pro-inflammatory cytokine expression.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrated that the aerial parts of carrots possess higher levels of bioactive compounds and stronger antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities than the underground parts. In particular, the 50% ethanol extract of the aerial part (AS-E) showed the highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents, along with the strongest ABTS and DPPH radical scavenging activities. Although previous studies have identified and quantified phenolic compounds from either carrot roots or leaves [

19,

20,

21], direct comparisons between aerial and underground parts under the same analytical conditions have been very limited. Therefore, this study provides novel evidence that compositional differences between plant parts are closely associated with variations in antioxidant activity. However, since this study focused on the total phenolic and flavonoid contents rather than individual compounds, further phytochemical analyses are required to characterize and compare the specific phenolic and flavonoid constituents present in each extract. Such analyses would provide a more detailed understanding of the molecular basis underlying the observed functional differences.

In macrophages, the carrot extracts exhibited distinct biological effects depending on the extraction solvent and plant part. The hot-water extracts (AS-W and UG-W) significantly enhanced nitric oxide production and the secretion of IL-6 and TNF-α under non-stimulated conditions, indicating immune-stimulatory activity. These results are consistent with the general activation patterns observed in previous immunostimulatory studies [

22,

23], suggesting that carrot extracts possess potential as immunomodulatory materials. These effects may be associated with the presence of water-soluble polysaccharides in the extracts. Numerous studies have reported that polysaccharides isolated from plant-derived hot-water extracts exhibit immune-enhancing properties in macrophages and immunosuppressed mouse models [

24,

25]. Such polysaccharides are known to promote nitric oxide production and cytokine secretion, thereby activating innate immune responses, which is in agreement with the present findings. Therefore, the immunostimulatory activity of carrot hot-water extracts is likely, at least in part, mediated by polysaccharide-rich fractions that enhance macrophage function. Further studies are required to isolate and structurally characterize these polysaccharides and to confirm their immunomodulatory effects through in vivo experiments.

Under LPS-stimulated conditions, the carrot extracts exhibited anti-inflammatory activity, with clear differences depending on the extraction solvent and plant part. Based on nitric oxide levels, AS-E showed the strongest inhibitory effect among all samples, consistent with previous findings on carrot leaves reporting that ethanol extracts have greater anti-inflammatory activity than hot-water extracts [

26]. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects on IL-6 and TNF-α production were confirmed by comparing the ethanol extracts of the aerial and underground parts, with AS-E showing stronger suppression than UG-E. Taken together, these findings indicate that the ethanol extract of carrot aerial parts possesses significant potential as a natural anti-inflammatory material.

Overall, this study highlights the functional potential of carrot aerial parts as valuable bioresources that are often discarded after harvest. The aerial extracts, particularly the 50% ethanol extract (AS-E), exhibited superior antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, while the hot-water extracts (AS-W and UG-W) showed clear immunostimulatory effects. These results collectively suggest that differences in the chemical composition between the aerial and underground parts of carrots contribute to distinct biological activities. The strong bioactivity of the aerial ethanol extract indicates that the underutilized aerial portions of carrots can serve as promising sources of natural functional ingredients with both antioxidant and immune-regulating capacities. Further comprehensive studies involving in vivo models and the isolation of specific bioactive compounds are warranted to confirm these effects and to elucidate their underlying molecular mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This study comparatively evaluated the antioxidant and immunomodulatory activities of carrot aerial and underground parts extracted with hot water and 50% ethanol. The results revealed that the aerial parts, particularly the 50% ethanol extract (AS-E), contained higher levels of total phenolic and flavonoid compounds and exhibited the strongest radical-scavenging capacity. Moreover, the hot-water extracts (AS-W and UG-W) enhanced nitric oxide and cytokine (IL-6 and TNF-α) production in macrophages under non-stimulated conditions, indicating immune-stimulatory effects. In contrast, under LPS-stimulated conditions, AS-E effectively suppressed NO and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, demonstrating potent anti-inflammatory activity. Collectively, these findings suggest that carrot aerial parts, which are typically discarded as agricultural by-products, represent a valuable source of natural bioactive materials with antioxidant, immune-enhancing, and anti-inflammatory potential. Further in vivo studies and detailed structural characterization of the active compounds, including polysaccharides and phenolic constituents, are warranted to validate their physiological effects and practical applications as functional food ingredients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.C., H.J.L. and K.A.L.; methodology, S.S.C. and H.J.L.; software, J.E.L. and H.J.L.; validation, H.J.L. and K.A.L.; formal analysis, J.E.L.; investigation, S.S.C. and H.J.L.; resources, S.S.C. and K.A.L.; data curation, J.E.L. and H.J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, J.E.L. and H.J.L.; writing—review and editing, S.S.C. and K.A.L.; visualization, J.E.L. and H.J.L.; supervision, S.S.C. and K.A.L.; project administration, H.J.L. and K.-A.L.; funding acquisition, S.S.C. and K.A.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ABTS |

2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) |

| AS-E |

Aerial part 50% ethanol extract |

| AS-W |

Aerial part hot-water extract |

| DPPH |

2,2′-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl |

| IL-6 |

Interleukin-6 |

| LPS |

Lipopolysaccharide |

| NO |

Nitric oxide |

| TPC |

Total phenolic content |

| TFC |

Total flavonoid content |

| TNF-α |

Tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| UG-E |

Underground part 50% ethanol extract |

| UG-W |

Underground part hot-water extract |

References

- Mizgier, P.; Kucharska, A.Z.; Sokół-Łętowska, A.; Kolniak-Ostek, J.; Kidoń, M.; Fecka, I. Characterization of phenolic compounds and antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of red cabbage and purple carrot extracts. J. Funct. Foods 2016, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, E.; Shams, R.; Dash, K.K.; Bhasin, J.K.; Pandey, V.K.; Tripathi, A. Extraction and food enrichment applications of black carrot phytocompounds: A review. Appl. Food Res. 2024, 4, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, A.; Rasheed, A.; Ahmad Khan, A.; Khan, R.; Ahmad, M.; Bashir, R.; Hassan Mohamed, M. Exploring the health benefits and utility of carrots and carrot pomace: A systematic review. Int. J. Food Prop. 2024, 27, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boadi, N.O.; Badu, M.; Kortei, N.K.; Saah, S.A.; Annor, B.; Mensah, M.B.; Okyere, H.; Fiebor, A. Nutritional composition and antioxidant properties of three varieties of carrot (Daucus carota). Sci. Afr. 2021, 12, e00801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, B. Root vegetable side streams as sources of functional ingredients for food, nutraceutical and pharmaceutical applications: The current status and future prospects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 137, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lim, J.H.; Cho, S.K. Effect of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory on bioactive components of carrot (Daucus carota L.) leaves from Jeju Island. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2023, 66, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purewal, S.S.; Verma, P.; Kaur, P.; Sandhu, K.S.; Singh, R.S.; Kaur, A.; Salar, R.K. A comparative study on proximate composition, mineral profile, bioactive compounds and antioxidant properties in diverse carrot (Daucus carota L.) flour. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2023, 48, 102640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paludan, S.R.; Pradeu, T.; Masters, S.L.; Mogensen, T.H. Constitutive immune mechanisms: Mediators of host defence and immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2021, 21, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirayama, D.; Iida, T.; Nakase, H. The phagocytic function of macrophage—Enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in immunoregulation and therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, S.F.; Reis, R.L.; Ferreira, H.; Neves, N.M. Plant-derived bioactive compounds as key players in the modulation of immune-related conditions. Phytochem. Rev. 2025, 24, 343–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigoli, S.; Boskabady, M.H. The molecular basis of the immunomodulatory effects of natural products: A comprehensive review. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooda, P.; Malik, R.; Bhatia, S.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Najmi, A.; Zoghebi, K.; Halawi, M.A.; Makeen, H.A.; Mohan, S. Phytoimmunomodulators: A review of natural modulators for complex immune system. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, C.R.; Barreto Arantes, M.; de Faria Pereira, S.; da Cruz, L.; de Souza Passos, M.; de Moraes, L.; Vieira, I.J.C.; de Oliveira, D. Plants as sources of anti-inflammatory agents. Molecules 2020, 25, 3726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, R.A.; Hamid, A.A.; Mohamed, S.; Bakar, F.A. Total phenolic compounds, flavonoids, and radical scavenging activity of 21 selected tropical plants. J. Food Sci. 2010, 75, C28–C35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Floegel, A.; Kim, D.-O.; Chung, S.-J.; Koo, S.I.; Chun, O.K. Comparison of ABTS/DPPH assays to measure antioxidant capacity in popular antioxidant-rich US foods. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2011, 24, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, C. Nitric oxide and the immune response. Nat. Immunol. 2001, 2, 907–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arango Duque, G.; Descoteaux, A. Macrophage cytokines: Involvement in immunity and infectious diseases. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leja, M.; Kamińska, I.; Kramer, M.; Maksylewicz-Kaul, A.; Kammerer, D.; Carle, R.; Baranski, R. The content of phenolic compounds and radical scavenging activity varies with carrot origin and root color. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2013, 68, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, R.; Ismail, M.; Baroutian, S.; Farid, M. Effect of subcritical water on the extraction of bioactive compounds from carrot leaves. Food Bioproc. Technol. 2018, 11, 1895–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenio, M.H.A.; Pereira, R.G.F.A.; Abreu, W.C.; Pereira, M.C.A. Phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of tuberous root leaves. Int. J. Food Prop. 2017, 20, 2966–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Son, J.-S.; Le, M.H.; Justine, E.E.; Kim, Y.-J. Effect of Protaetia brevitarsis seulensis larvae fermented by Bacillus subtilis PB2110 on nutritional composition and immunomodulatory activity. J. Insects Food Feed 2025, 11, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.-J.; Tran, M.T.H.; Le, M.H.; Justine, E.E.; Kim, Y.-J. Paraprobiotic derived from Bacillus velezensis GV1 improves immune response and gut microbiota composition in cyclophosphamide-treated immunosuppressed mice. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1285063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zong, R.; Wu, D.; Jin, C. A water-soluble polysaccharide from the fibrous root of Anemarrhena asphodeloides Bge. and its immune enhancement effect in vivo and in vitro. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022, 2022, 8723119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.-G.; Chen, J.-J.; Xu, J.-M.; Chen, W.; Chen, X.-B.; Yang, D.-S. The chemical profiling and immunological activity of polysaccharides from the rhizome of Imperata cylindrica using hot water extraction. Molecules 2025, 30, 12635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.S.; Lim, J.H.; Cho, S.K. Effect of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory on bioactive components of carrot (Daucus carota L.) leaves from Jeju Island. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2023, 66, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).