Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- We introduce CVaR into risk assessment in railway transportation scenarios for risk aversion routes and dispatch decisions.

- Taking into account the risk unfairness of the external public, we have added risk eq-uity goal to the CVaR-based assessment, and proposed a new model named condi-tional value-at-risk with equity (CVaRE).

- We introduce a practical example, and use the k-shortest CVaRE algorithm to solve the problem model, generating the optimal solution. This can serve as a guide and reference for railway hazardous materials transportation dispatch decision-makers.

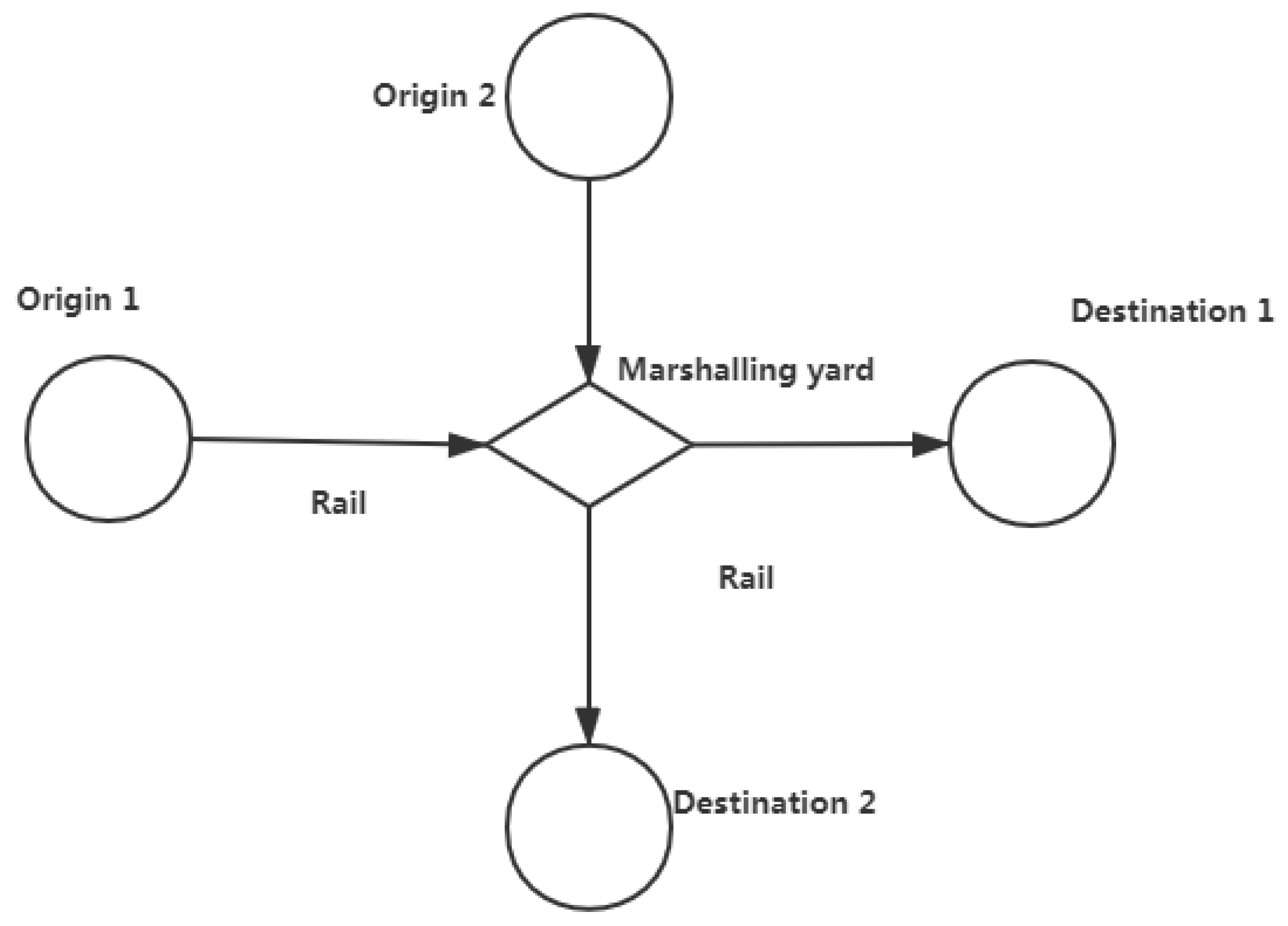

2. Problem Description

2.1. Assumptions and Notations

2.1.1. Assumptions of Railway Transportation System

2.1.2. Notations

| Set of yards, indexed by i, j, k | |

| Set of marshalling yards, indexed by k, | |

| Set of arcs in the network, indexed by (i, j), (k, j) | |

| Set of railway shipments between railway yards(or yard and marshalling yards), indexed by v | |

| Set of yards in service of shipment v | |

| Set of arcs in service of shipment v |

| Cost of moving a Hazmat container on arc (i, j) in shipment v | |

| Exposure risk of moving a Hazmat container on arc (i, j) in shipment v | |

| Exposure risk of using yard k for a Hazmat container in shipment v | |

| Origin of shipment v | |

| Destination of shipment v | |

| Non-negative integer, number of Hazmat containers in shipment v | |

| Confidence level, but also represents the level of risk aversion of suppliers | |

| Risk consequences in shipment v on arc (i, j) in shipment v | |

| Accident probability on arc (i, j) in shipment v | |

| Risk consequences of using yard k for Hazmat shipment v | |

| Probability of accident in using yard k | |

| Select Route VaR Threshold Under CVaR* | |

| 0-1 variable, whether to select arc (i, j) in shipment v as transportation section | |

| 0-1 variable, whether to select yard k as railway yard in shipment v | |

| Number of containers in shipment v unload at Marshalling yard k | |

| Delivery time associated with shipment v | |

| Time for handling containers at marshalling yard k | |

| Time for running on the railway route | |

| Impact radius of Hazmat accident | |

| Maximum population density of the area passed through by arc (i, j) | |

| Population density of the area where yard k is located |

2.2. Hazmat Risk Measurement Formulation Based on VaR and CVaR

3. Model Establishment

3.1. Mathematical Model

3.1.1. Model Based on CVaR of Direct Transportation Case (Base Case)

3.1.2. Model Based on CVaRE of Transfer Transportation Case Considering Risk Equity

3.2. Solution Methodology

4. Computational Analysis

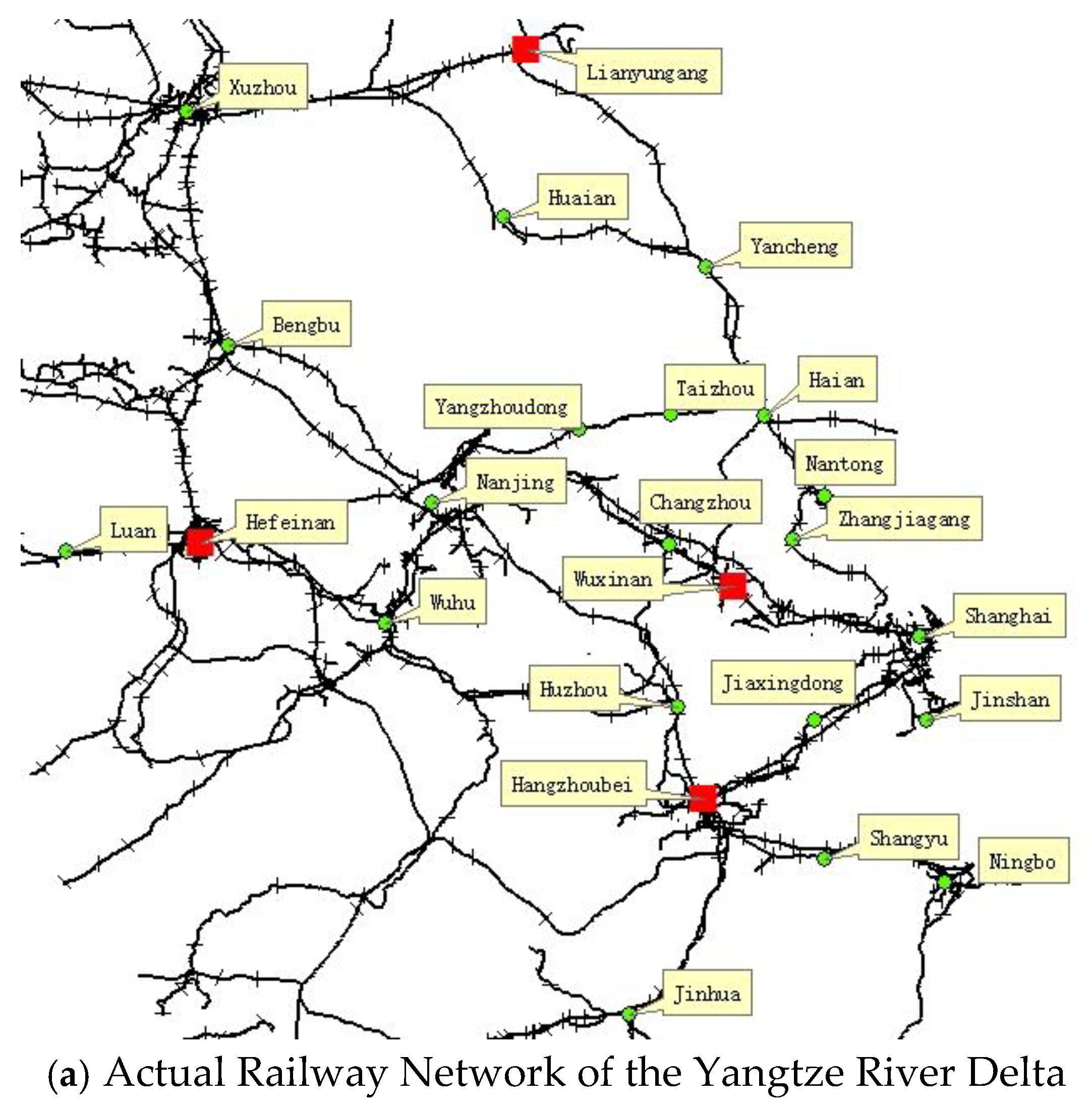

4.1. Problem Setting

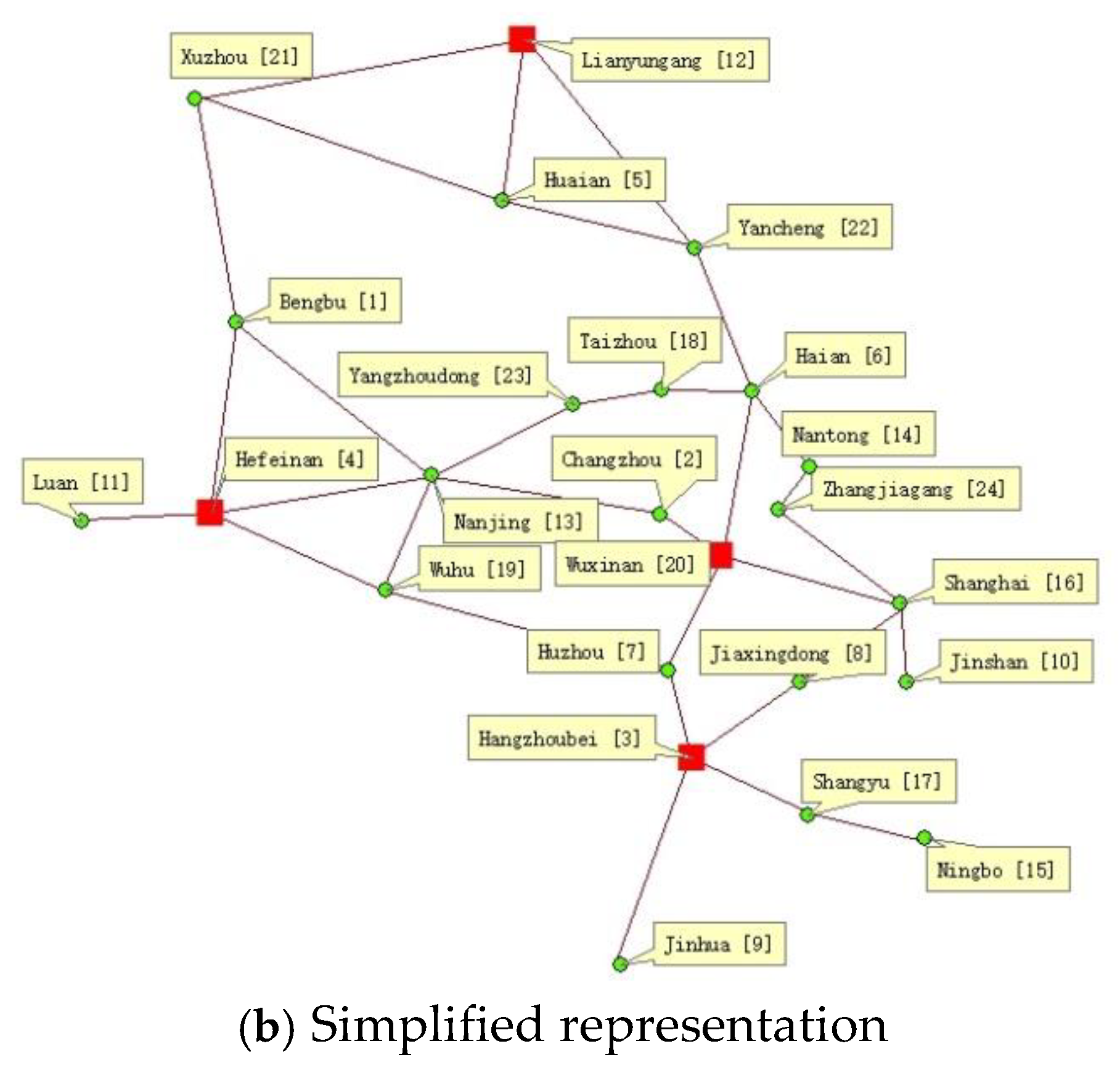

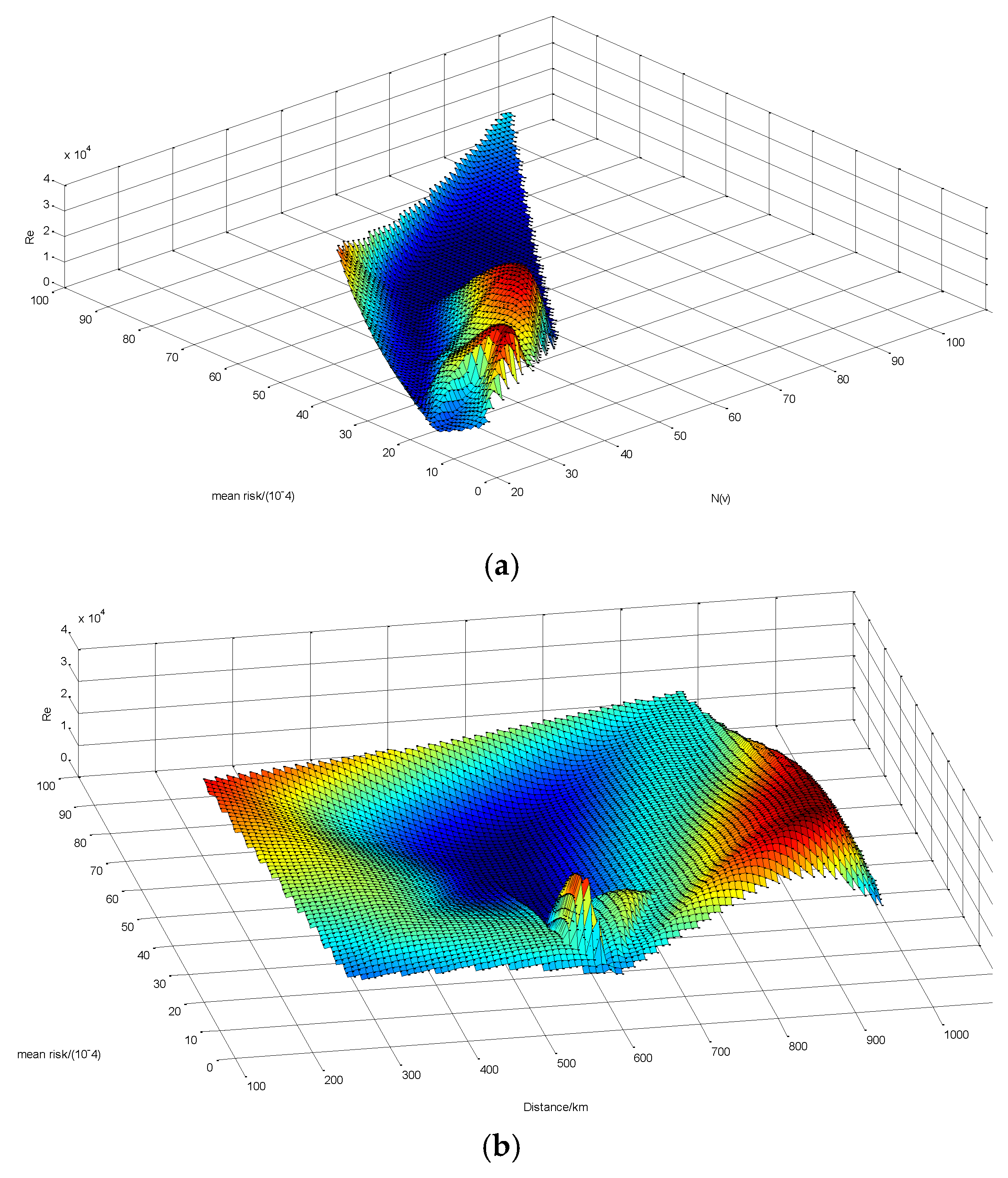

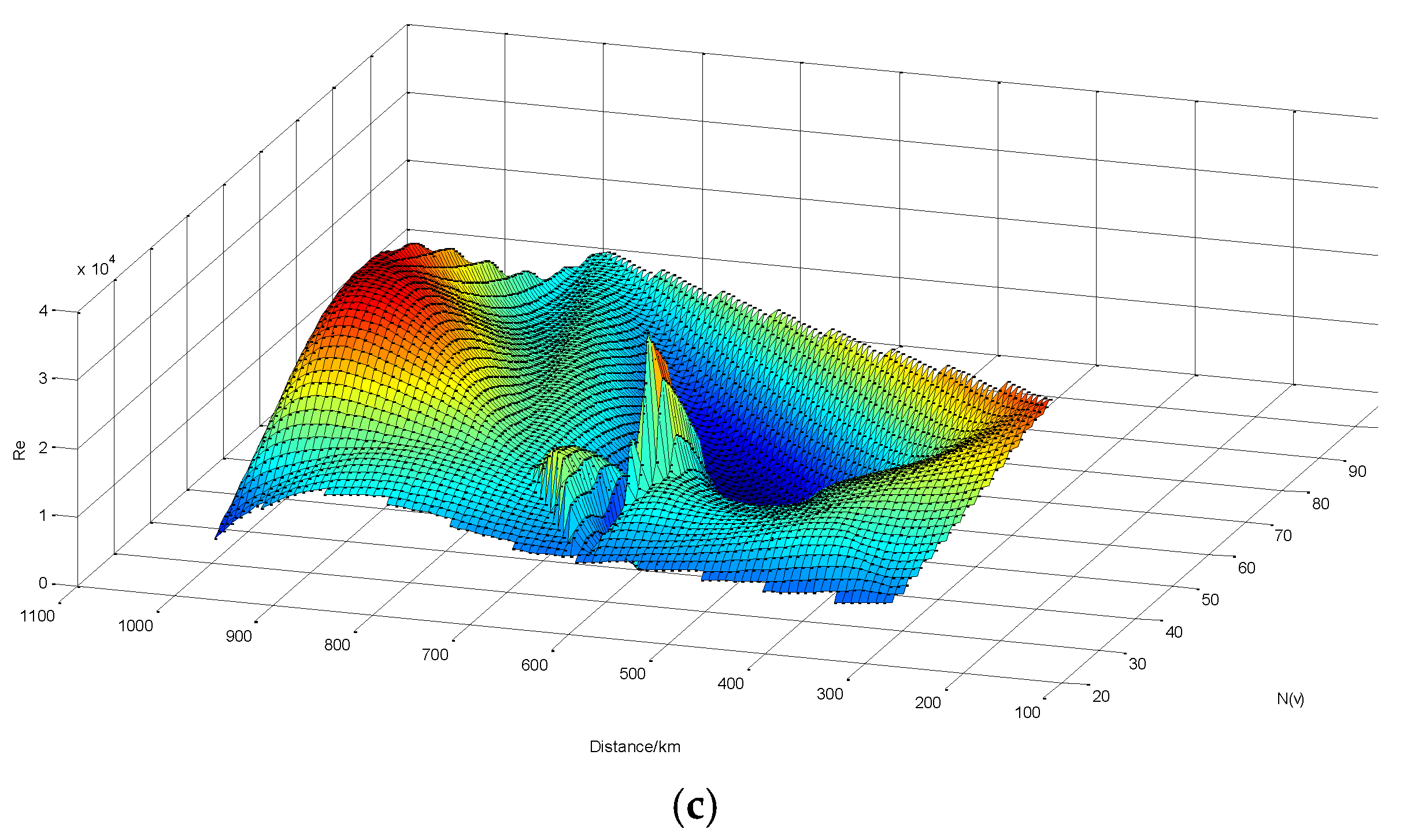

4.2. Data Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Federal Railroad Administration Office of Safety Analysis. Available online: https://safetydata.fra.dot.gov/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- China Federation of Logistics and Purchasing. In China Logistics Yearbook, He, L.M., Ed.; China Fortune Publishing Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2023; pp. 282-283.

- The "May 23 Zhangshi Expressway Tunnel Explosion Accident". Available online: https://baike.baidu.com/item/5%C2%B723%E5%BC%A0%E7%9F%B3%E9%AB%98%E9%80%9F%E9%9A%A7%E9%81%93%E7%88%86%E7%82%B8%E4%BA%8B%E6%95%85/20815591 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- The "February 3 Ohio Train Derailment Accident" in the United States. Available online: ://baike.baidu.com/item/2%C2%B73%E7%BE%8E%E5%9B%BD%E4%BF%84%E4%BA%A5%E4%BF%84%E5%B7%9E%E7%81%AB%E8%BD%A6%E8%84%B1%E8%BD%A8%E4%BA%8B%E6%95%85/62636919 (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Bubbico, R.; Maschio, G.; Mazzarotta, B.; Milazzo, M.F.; Parisi, E. Risk management of road and rail transport of hazardous materials in Sicily. Journal of Loss Prevention in the Process Industries 2006, 19, 32-38. [CrossRef]

- Abkowitz, M.; Lepofsky, M.; Cheng, P. Selecting criteria for designating hazardous materials highway routes. Transportation Research Record 1992, 1333.

- Erkut, E.; Ingolfsson, A. Catastrophe avoidance models for hazardous materials route planning. Transportation Science 2000, 34, 165-179. [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Verter, V. A lead-time based approach for planning rail–truck intermodal transportation of dangerous goods. European Journal of Operational Research 2010, 202, 696-706. [CrossRef]

- Verma, M. Railroad transportation of dangerous goods: A conditional exposure approach to minimize transport risk. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2011, 19, 790-802. [CrossRef]

- Assadipour, G.; Ke, G.Y.; Verma, M. Planning and managing intermodal transportation of hazardous materials with capacity selection and congestion. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2015, 76, 45-57. [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.Y. Managing rail-truck intermodal transportation for hazardous materials with random yard disruptions. Annals of Operations Research 2020, 309, 457-483. [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y. A Fuzzy Multi-Objective Routing Model for Managing Hazardous Materials Door-to-Door Transportation in the Road-Rail Multimodal Network With Uncertain Demand and Improved Service Level. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 172808-172828. [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Wang, S. LNG Bunkering Station Deployment Problem—A Case Study of a Chinese Container Shipping Network. Mathematics 2023, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.; Batta, R.; Kwon, C. Value-at-risk model for hazardous material transportation. Annals of operations research 2014, 222, 361-387. [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Fu, E.; Huang, D.; Ke, G.Y.; Verma, M. A value-at-risk based approach to the routing problem of multi-hazmat railcars. European Journal of Operational Research 2025, 320, 132-145. [CrossRef]

- Toumazis, I.; Kwon, C. Routing hazardous materials on time-dependent networks using conditional value-at-risk. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies 2013, 37, 73-92. [CrossRef]

- Faghih-Roohi, S.; Ong, Y.-S.; Asian, S.; Zhang, A.N. Dynamic conditional value-at-risk model for routing and scheduling of hazardous material transportation networks. Annals of Operations Research 2015, 247, 715-734. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, F.; Mausser, H.; Rosen, D.; Uryasev, S. Credit risk optimization with conditional value-at-risk criterion. Mathematical programming 2001, 89, 273-291. [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Pang, J.; Liu, L.; Wu, S.; Huang, T. An Emergency Quantity Discount Contract with Supplier Risk Aversion under the Asymmetric Information of Sales Costs. Mathematics 2022, 10. [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Cai, J.; Wang, G.; Ge, X.; Teng, Y.; Jiang, H. Research on Decision Analysis with CVaR for Supply Chain Finance Based on Blockchain Technology. Mathematics 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.D.; Verma, M. Conditional value-at-risk (CVaR) methodology to optimal train configuration and routing of rail hazmat shipments. Transportation Research Part B: Methodological 2018, 110, 79-103. [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Cheng, R.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Larsen, A.; Nielsen, O.A. Risk-averse optimization of disaster relief facility location and vehicle routing under stochastic demand. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 2020, 141. [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Kwon, C. Risk-averse network design with behavioral conditional value-at-risk for hazardous materials transportation. Transportation Science 2020, 54, 184-203. [CrossRef]

- Carotenuto, P.; Giordani, S.; Ricciardelli, S.; Rismondo, S. A tabu search approach for scheduling hazmat shipments. Computers & Operations Research 2007, 34, 1328-1350. [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Ke, G.Y.; Verma, M. A routing and scheduling approach to rail transportation of hazardous materials with demand due dates. European journal of operational research 2017, 261, 154-168. [CrossRef]

- Bianco, L.; Caramia, M.; Giordani, S.; Piccialli, V. A game-theoretic approach for regulating hazmat transportation. Transportation Science 2016, 50, 424-438. [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, P.; Crainic, T.G.; Gendreau, M.; Minner, S. Population-based risk equilibration for the multimode hazmat transport network design problem. European Journal of Operational Research 2020, 284, 188-200. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, S.D.; Verma, M. Equitable routing of rail hazardous materials shipments using CVaR methodology. Computers & Operations Research 2021, 129, 105222. [CrossRef]

- Rockafellar, R.T.; Uryasev, S. Conditional value-at-risk for general loss distributions. Journal of banking & finance 2002, 26, 1443-1471. [CrossRef]

- Sarykalin, S.; Serraino, G.; Uryasev, S. Value-at-Risk vs. Conditional Value-at-Risk in Risk Management and Optimization. In State-of-the-Art Decision-Making Tools in the Information-Intensive Age; 2008; pp. 270-294.

- Hong, F. National Bureau of Statistics. National Bureau of Statistics 2019, 35.

| Origin | Destination | N(v) | CVaR* | Route | |

| 1 | 12 | 30 | 20256.98 | [1,21,12] | 17 |

| 1 | 3 | 59 | 45842.12 | [1,4,19,7,3] | 23 |

| 4 | 14 | 39 | 49434.77 | [4,13,23,18,6,14] | 9 |

| 4 | 3 | 74 | 34381.59 | [4,19,7,3] | 23 |

| 4 | 12 | 54 | 30385.47 | [4,1,21,12] | |

| 5 | 14 | 23 | 27984.10 | [5,22,6,14] | 10 |

| 5 | 13 | 35 | 30385.47 | [5,21,1,13] | 17 |

| 7 | 1 | 25 | 31266.28 | [7,19,4,1] | 8 |

| 7 | 15 | 37 | 30606.14 | [7,3,17,15] | 11 |

| 9 | 13 | 31 | 44517.62 | [9,3,7,19,13] | 6 |

| 10 | 7 | 20 | 69064.39 | [10,16,8,3,7] | 1 |

| 11 | 14 | 24 | 46753.52 | [11,4,13,23,18,6,14] | 1 |

| 13 | 10 | 38 | 129906.74 | [13,19,7,3,8,16,10] | 23 |

| 15 | 3 | 54 | 18733.65 | [15,17,3] | 11 |

| 15 | 9 | 27 | 26859.05 | [15,17,3,9] | 6 |

| 15 | 19 | 40 | 45842.12 | [15,17,3,7,19] | 23 |

| 16 | 21 | 102 | 186583.81 | [16,8,3,7,19,4,1,21] | 25 |

| 16 | 13 | 54 | 115262.50 | [16,8,3,7,19,13] | 23 |

| 16 | 23 | 30 | 100118.54 | [16,8,3,7,19,13,23] | 9 |

| 16 | 9 | 31 | 64910.37 | [16,8,3,9] | 6 |

| 17 | 16 | 36 | 72276.81 | [17,3,8,16] | 11 |

| 18 | 20 | 48 | 43250.94 | [18,6,20] | 28 |

| 18 | 16 | 37 | 112363.00 | [18,6,14,24,16] | 21 |

| 20 | 11 | 30 | 38540.30 | [20,2,13,4,11] | 1 |

| 20 | 5 | 18 | 36919.47 | [20,6,22,5] | 3 |

| 22 | 24 | 12 | 25710.35 | [22,6,14,24] | 1 |

| 22 | 16 | 29 | 96069.21 | [22,6,14,24,16] | 10 |

| 24 | 10 | 39 | 78724.22 | [24,16,10] | 32 |

| 3 | 12 | 52 | 117998.97 | [3,7,19,4,1,21,12] | 23 |

| O-D pair | N(v) | Distance(P) | ||

| (1,12) | 30 | 374 | 16906.03 | 25.36 |

| (1,3) | 59 | 553 | 0 | 34.35 |

| (4,14) | 39 | 550 | 15532.25 | 15.20 |

| (5,13) | 35 | 581 | 36197.46 | 15.85 |

| (9,13) | 31 | 587 | 14621.13 | 18.92 |

| (10,7) | 20 | 274 | 7886.06 | 15.21 |

| (11,14) | 24 | 606 | 8364.41 | 8.39 |

| (13,10) | 38 | 586 | 1880.56 | 40.45 |

| (16,13) | 54 | 544 | 0 | 63.04 |

| (16,21) | 102 | 878 | 14254.90 | 99.60 |

| (16,23) | 30 | 645 | 20646.36 | 22.06 |

| (18,16) | 37 | 709 | 15214.80 | 31.11 |

| (22,16) | 29 | 1002 | 2822.4 | 29.48 |

| (24,10) | 39 | 176 | 32237.57 | 61.71 |

| (3,12) | 52 | 927 | 34307.54 | 34.83 |

| Risk-measure value | Route properties | |||||

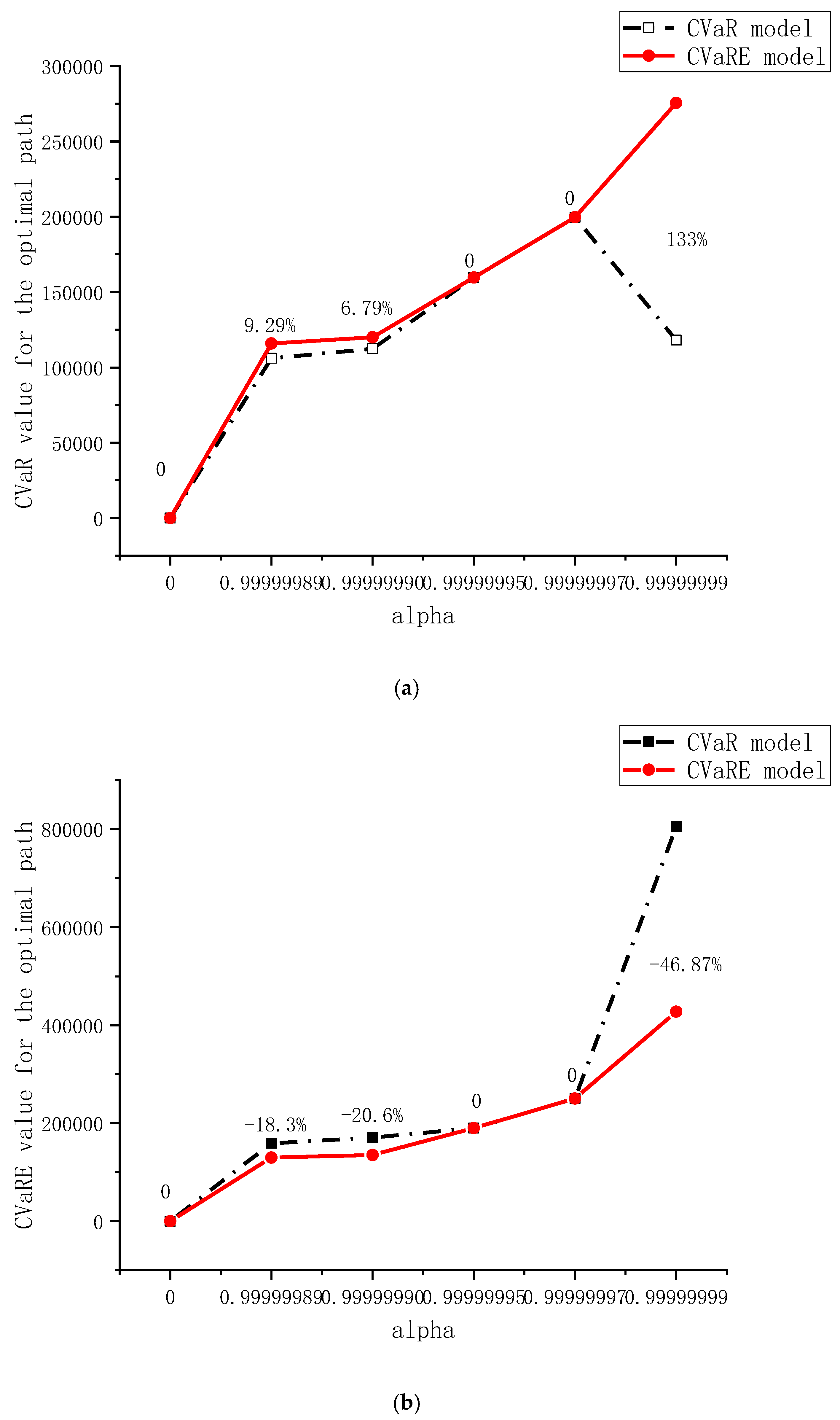

| Model | Confidence level |

CVaRE* | CVaR* | VaR* | Number of arcs | Distance(km) |

| CVaR | 0 | 0.0189 | 0.0124 | 0 | 4 | 303 |

| 0.99999989 | 158818.48 | 106068.99 | 10755.56 | 4 | 303 | |

| 0.99999990 | 170387.44 | 112363.00 | 10807.08 | 4 | 303 | |

| 0.99999995 | 190079.78 | 159650.17 | 11460.53 | 7 | 709 | |

| 0.99999997 | 250355.35 | 199639.35 | 17737.43 | 7 | 709 | |

| 0.99999999 | 804905.68 | 118086.33 | 39362.11 | 3 | 297 | |

| CVaRE | 0 | 0.0189 | 0.0124 | 0 | 4 | 303 |

| 0.99999989 | 129759.72 | 115928.08 | 10755.56 | 7 | 709 | |

| 0.99999990 | 135202.78 | 119987.98 | 10807.08 | 7 | 709 | |

| 0.99999995 | 190079.78 | 159650.17 | 11460.53 | 7 | 709 | |

| 0.99999997 | 250355.35 | 199639.35 | 17737.43 | 7 | 709 | |

| 0.99999999 | 427682.78 | 275534.77 | 39362.11 | 7 | 709 | |

| Cost (CNY) | |||

| Direct transportation(base case) | 1721712.71 | 2234020.54 | 2349421.56 |

| Transfer transportation | 1848079.10 | 2777571.41 | 2361436.20 |

| Min cost(P) | 1906528.87 | 3014526.37 | 2169930.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).