1. Introduction

Medical education presents students with complex and abstract topics, requiring them to understand, retain, and apply vast amounts of information in real-time [

1,

2]. As students progress, their knowledge base expands, which can lead to challenges such as reduced retention, limited peer engagement, and increased burnout [

3].

To manage this growing body of knowledge, students often use mnemonics [

4]—memory aids that simplify information [

5]. For instance, the acronym "GFR" helps students recall the adrenal cortex layers: zona

glomerulosa, zona

fasciculata, and zona

reticularis, aligning with the term glomerular filtration rate. However, while mnemonics can simplify complex information, they may not fully capture a topic's intricacies [

6]. Additionally, students might struggle to remember numerous mnemonics over time, especially if they lack engaging or enjoyable elements. This could potentially be overcome by combining mnemonics with other learning strategies such as edutainment for easier memory consolidation and recall.

Edutainment, which combines education and entertainment, aims to make learning more enjoyable by incorporating storytelling, humor, and visual aids [

7]. This approach has been shown to enhance student engagement and retention [

8]. These strategies can often be time consuming and cost restrictive, especially for high production value materials. The advent of generative artificial intelligence (genAI) offers a potential solution to this due to its speed, low cost, and ease of use. One of our group’s previous examples of genAI’s utility in edutainment is Cinematic Clinical Narratives, which are interactive multimedia learning experiences designed to enhance student engagement by integrating cinematic storytelling and narrative-based learning techniques [

9].

The use of genAI has recently emerged as a valuable tool in medical education, assisting in creating personalized learning materials [

10]. GenAI-driven simulations, such as synthetic patient interactions, have been developed to help students practice difficult conversations, enhancing their communication skills [

11]. Others have also shown the potential of AI-generated content to improve educational outcomes by providing interactive and visually appealing resources [

12,

13]. Moreover, AI applications have been explored to improve medical students' competencies, providing frameworks and tools that integrate AI into medical curricula [

14].

To address the challenges faced by medical students, we utilized genAI to combine mnemonics and edutainment to create a double feature CCN short film. Our goal was to make antiparasitic pharmacology topics more engaging and easier to retain long-term.

Recognizing the cognitive burden in medical training, particularly in pharmacology, we developed two CCNs—Alien: Parasites Within and Wormquest—and presented them to first-year medical students during their antiparasitics pharmacology lessons. This study aims to evaluate the impact of this CCN short film approach on learning outcomes and student engagement. We hypothesize that the integrated CCN approach will enhance exam scores and increase student engagement compared to traditional text-based cases.

2. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at the University of Idaho WWAMI Medical Education Program, part of the six-campus/site collaborative University of Washington School of Medicine program serving Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho. The WWAMI program enables students to complete their first two preclinical years of medical education in their home states before transitioning to clinical training, ensuring accessibility to medical education across these regions. This study involved first-year medical students from all six WWAMI sites (n=275), who received uniform instructional material and exam questions. The primary aim was to evaluate the impact of the double feature CCN (created using genAI, mnemonics, and edutainment) on exam performance and engagement during their antiparasitic pharmacology education.

2.1. Participants

The participants included first-year medical students from six different locations or sites. All students received the same lecture content and exam questions. The experimental group comprised 40 students (n=40) from one site (site 6) while the remaining 235 students served as the control group across the other 5 sites.

2.2. Intervention

All students were enrolled in a 6-week infections and immunology (I&I) course during which they received a one-hour pharmacology lecture covering material related to antiparasitic medications (Presentation S1). This covered the pharmacology of both antimalarial medications as well as antihelminth medications. The end of the lecture involved clinical cases where students were able to apply knowledge from the lecture to treat malaria and helminth infected patients. The experimental group (n=40) received the dual feature CCN, which involved watching the Alien: Parasites Within short film (Video S1), and listening to the narration of the Wormquest CCN (Video S2), while also answering questions relating to each case as an active learning exercise. The control groups received traditionally presented clinical cases which involved reading the case material on the slide (either the lecturer or student volunteer) and then answering similar questions as the experimental group.

A suite of genAI tools were utilized in the production of the Dual Feature CCN (

Figure 1).

2.3. Script Writing

For Script Writing, the initial plot and mnemonics representing drug mechanisms or adverse effects were conceptualized. First an optimized prompt for generating CCNs was generated with ChatGPT 4o utilizing the method of LLMs as prompt optimizers [

15]. The researcher then modified the prompt to include the general outline of the CCN plot. These elements were then input into ChatGPT o1-preview to generate the initial script. Subsequent iterations were made until the final version was completed. This workflow is presented in

Figure 2 and the full optimized prompt can be viewed in Methods S1.

2.4. Art Production

In the Art Production phase, we developed both character and environment art using a combination of advanced AI tools. Character art was initially generated using Stable Diffusion XL within ComfyUI, employing a custom workflow provided by Muckmumpitz [

16] to produce anime-style representations of George Clooney, Rebel Wilson, and the Alien (ComfyUI S1). Post-processing was conducted using Adobe Firefly for in-painting and out-painting the character art, ensuring visual consistency and refinement.

For the environment art, we utilized BlackForest Labs' Flux.1 [dev] in ComfyUI to create immersive and detailed locations that complemented the character designs (ComfyUI S2). Prompts for Flux.1 [dev] image generation were automized with the glif Flux Prompt Enhancer [

17]. This combination of tools allowed for the creation of a visually cohesive and engaging setting for the narrative.

2.5. Facial Animations

For Facial Animations, Live Portrait within ComfyUI was utilized. The process involved uploading images of the characters on a green screen background, followed by recording the lines while performing the facial expressions. These recordings were then used to transfer the facial animations onto the AI-generated character art using a custom ComfyUI workflow provided by Jason Stone [

18] (ComfyUI S3), creating realistic and dynamic expressions and lip movements.

2.6. Voice Changer

For actor voices, Eleven Labs' voice-to-voice feature was utilized. Audio from the videos created for facial animation using Live Portrait was extracted and uploaded to Eleven Labs. The voice-to-voice feature then transformed the user's own voice into a different voice provided by Eleven Labs, ensuring diverse vocal effects.

2.7. Animation and Camera Movement

For Animation and Camera Movement, Kling 1.0 and 1.5 were employed. The process involved uploading either starting, final, or both starting and final frames. The AI was then prompted with the desired animation or camera movements. The "draw arrows" feature in Kling 1.0 was used to indicate the motion path, ensuring smooth and accurate transitions. For scenes involving explosions, such as the RBC and ship explosion, Pika AI's explode functionality was utilized. Starting frames were uploaded on a green screen, and Pika generated the exploding video, which was then composited into the final frame. Kling 1.5's text-to-video functionality was also used to create the space scenes. Additionally, Medimon animations incorporated into the video were not AI-generated but were hand-done in Adobe After Effects.

2.8. Soundtrack and Sound Effects

For the soundtrack, Udio 1.5 was used to generate various thematic audio elements. Special attention was given to the final song, a version of "Like a G6" by Far East Movement, where the original track was uploaded into Udio. ChatGPT 4o was used to rewrite the lyrics into mnemonic-based lyrics about malaria infection and how G6PD deficient patients can get hemolytic anemia when treated with the antimalarial medication primaquine (Methods S2). After iterating on the lyrics with ChatGPT 4o, the final version along with the original song were uploaded to Udio to produce the final version of the song with their Remix feature.

For sound effects, Eleven Labs was employed to generate audio from text prompts, which were then integrated along with the soundtrack into the final product.

2.9. Post-Production

In the Post-Production phase, Adobe Premiere Pro was utilized to bring all the elements together. This process involved compositing the images and video clips generated during production, integrating the soundtrack and sound effects, and synchronizing the audio with the animations and visual elements. Attention was paid to ensure seamless transitions and alignment of all components. The final step was rendering the completed video. An overview of the entire production can be viewed with Video S3.

2.10. Assessments

Students were assessed throughout the course with weekly exams (n=5) as well as a cumulative exam at the end of the course (N=6). The educational intervention was performed before exam 5. Students were assessed on their knowledge of antiparasitic pharmacology on two questions on Exam 5 which occurred 5 days after the intervention, and then an additional question on the final course exam (Exam 6) which occurred 9 days after the intervention. The same exams were administered to all students at all sites at similar times.

2.11. Data Collection

Following the final exam, students in the experimental group were invited to participate in a survey. A total of 34 students (n=34) from the experimental group completed the Situational Interest Survey of Multimedia (SIS-M) which is designed to assess different aspects of situational interest in multimedia learning environments. This includes the measurement of triggered situational interest (initial engagement with multimedia), feeling interest (perceived preference of the content), and value interest (perceived usefulness of the content). Initially used to assess the effectiveness of multimedia in promoting engagement and motivation in higher education and adult learning [

19,

20], the SIS-M has recently been applied to medical education research [

9,

21], making it a suitable tool for evaluating learner engagement in this study.

The survey included questions that asked students to consent to participate and respond to the 12-item SIS-M twice, first referencing the Dual Feature CCN and then the traditional lecture-based cases (

Table S1). The survey includes items to rank on a 1-5 scale (1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree), a question asking for preference of case format, and an open-ended question asking, “Why do you think this is your preference.”

Student exam grades and specific grades on the material-specific exam questions were recorded to measure baseline achievement and material-specific achievement, respectively.

2.12. Data Analysis

Researchers utilized SPSS to analyze the students' grades and SIS-M survey results. Achievement data were reported as the average exam score at each site and the average score on material-specific exam questions for each campus. Since we did not have access to individual student grades, but instead the average site grades for each exam and exam question, we could not perform statistical analysis between groups.

The SIS-M survey analysis considered multiple dimensions of situational interest: triggered interest (Trig), maintained interest (MT), maintained-feeling (MF), and maintained-value (MV). Given the parametric nature of the data, four paired t-tests were used to evaluate experimental group students' interest in traditional cases and the dual feature CCN.

For the open-ended question in the SIS-M survey, thematic analysis was conducted using ChatGPT (GPT4o, o1-mini, and o1) and Claude 3.5 Sonnet (

Figure 3). This involved generating initial codes and identifying themes [

9,

22]. Prompt engineering techniques used included Persona Prompting [

23,

24], Zero-Shot Chain of Thought (CoT) [

25], Self-Criticism [

26], and Mixture-of-Agents (MoA) [

27]. The Zero-Shot Chain of Thought prompting was omitted in prompts utilizing any of the reasoning ChatGPT o1 line of models as they have built in Tree-of-Thought functionality in every output. The workflow involved submitting the responses to the less proficient, but faster and cheaper “amateur models” first (ChatGPT 4o, o1-mini, and Claude 3.5 Sonnet), followed by having a reasoning, more expensive “judge model” (ChatGPT o1) review and combine the outputs of the amateur models. This was followed by the researcher combining and refining these themes for overlap and relevancy. The workflow and prompts are presented in

Figure 3.

2.13. Ethical Considerations

This educational research was approved as exempt by the institutional review board of the University of Idaho (21-223). Given the incorporation of references to real celebrities and the use of AI-generated images resembling actual individuals, legal counsel was consulted to ensure compliance with applicable guidelines. The counsel confirmed that, within the educational context and with the use of non-photorealistic and non-easily recognizable depictions of the individuals, this usage was permissible. To further address potential concerns, the CCN concluded with a brief discussion of the real-life health struggles of the referenced celebrities, utilizing only publicly available information. Additionally, disclaimers were included at the beginning of the CCN short film and reiterated at the conclusion of the lecture, explicitly clarifying that the celebrities were not involved in the project. Despite these precautions, the use of AI-generated representations of real individuals remains a legally ambiguous area, and we recommend future projects approach this technique with careful consideration and, where possible, additional legal review.

To ensure the confidentiality of participants, the SIS-M survey was conducted anonymously. No identifying information was collected, allowing students to provide candid feedback without concerns about personal attribution. This approach ensured the integrity of the data while protecting the privacy of all participants.

3. Results

3.1. Achievement

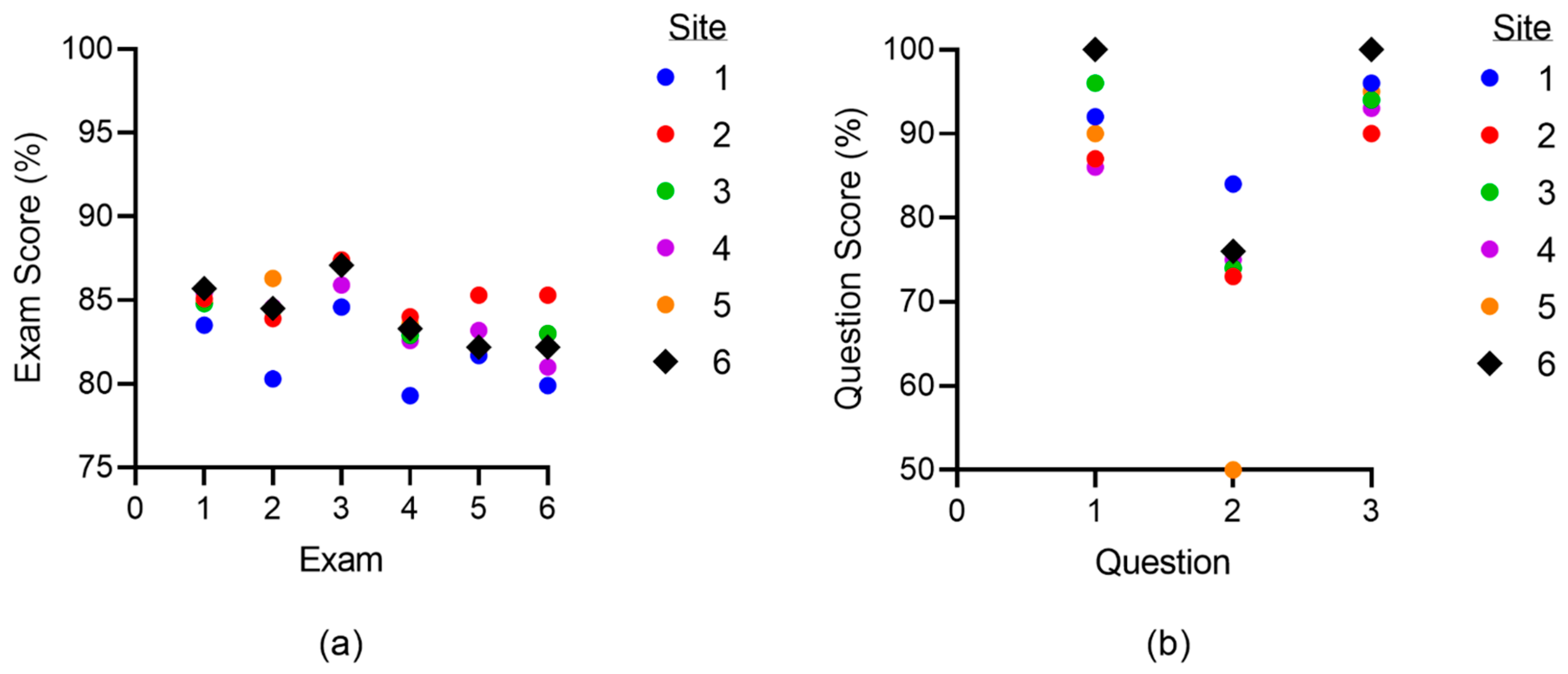

Exam grades across all sites and all exams in the course were analyzed to establish baseline knowledge levels among students (Figure XA). The results indicated that the experimental site (Site 6) demonstrated comparable performance to that of the other sites, indicating a similar level of knowledge of the students prior to the intervention. This baseline comparison ensures that any observed differences in performance can be attributed to the dual-feature cinematic clinical narrative (CCN) intervention. When examining average scores for each site on exam questions specifically testing material covered by the dual-feature CCN, the experimental site (site 6) demonstrated enhanced performance (Figure XB). Site 6 was the only site that scored a perfect 100% on two out of three material-specific questions suggesting the potential effectiveness of the CCN in enhancing understanding and retention of the covered pharmacology topics. A comparative analysis between the average scores of the experimental site and the combined average of the other sites revealed higher scores for the experimental site on all three material-specific questions (average increase of 8% ± 2%), further suggesting the impact of the dual-feature CCN in improving student achievement on targeted educational content.

Figure 4

3.2. Interest and Engagement

Notably, 21 out of 34 (61.76%) participants preferred the dual feature CCN, four out of 34 (11.76%) preferred the traditional clinical case, and nine out of 34 (26.47%) participants reported “no preference” for using these learning materials.

To address the differences in situational interests between using the dual feature CCN and traditional clinical case, four paired sample t-tests were conducted to explore the participants’ multiple dimensions of situational interest: triggered situational interest (Trig), maintained-feeling interest (MF), maintained-value interest (MV), and maintained interest (MT). The results, presented in

Table 1, revealed a significant difference in triggered situational interest (Trig), maintained-feeling interest (MF), and maintained interest (MT) among the 34 participants. However, the maintained-value interest (MV) did not show a significant difference while using different cases.

The participants' average triggered situational interest (Trig) of the dual feature CCN (M=4.78, SD=0.39) was significantly higher than the traditional clinical case (M=3.79, SD=0.99), t=-5.88, p<.001. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was -1.33 to -0.64, suggesting a preference for the dual feature CCN.

The results for maintained-feeling (MF) interest revealed that the participants’ interest rating of the dual feature CCN (M=4.33, SD=0.64) was significantly greater than that of the traditional clinical cases (M=4.02, SD=0.78), t=-2.69, p=0.011. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was -0.54 to -0.08.

The outcomes for maintained-value (MV) interest suggested that the participants’ interest rating of the dual feature CCN (M=4.49, SD=0.65) was not significantly different from that of the traditional clinical cases (M=4.43, SD=0.71), t=-0.64, p=0.526. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was -0.22 to 0.11.

The findings for maintained (MT) interest indicated that the participants’ interest rating of the redesigned learning materials (M=4.41, SD=0.6) was significantly greater than that of the original learning materials (M=4.23, SD=0.71), t=-2.09, p=0.045. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was -0.36 to -0.004.

The thematic analysis of the open-ended survey responses in the SIS-M provided insights into why students preferred the dual feature CCN over traditional lecture cases.

Engagement and Memorability: CCNs capture student interest through entertaining storytelling and relatable characters, leading to higher engagement and enjoyment. Learners cite outlandish plots, vivid visuals, and catchy songs as key drivers for deeper retention of complex medical concepts.

Active Learning and Visual Aids: Narratives encourage students to synthesize new information by weaving medical details into a cohesive storyline. Strong visual elements further support comprehension, transforming abstract material (e.g., parasites) into memorable imagery.

Practicality and Realism of Traditional Cases: Traditional case formats remain valuable for their structured presentation, ease of reference, and clear clinical relevance. This straightforward approach is often preferred for quick review and focused study sessions.

Preference for a Balanced Approach: Many respondents advocate blending CCNs with traditional cases to maximize learning. This dual strategy meets a range of learning styles, offering both entertainment-driven engagement and concise clinical clarity.

Potential Distractions and Overload: Some students find CCNs overstimulating, struggling to separate essential content from the surrounding “movie” elements. Overly elaborate storytelling can risk obscuring key information if not carefully balanced with clear learning objectives.

Overall, the findings suggest that most students appreciate the novelty and engagement of Cinematic Clinical Narratives, citing enhanced enjoyment, memorability, and active learning. However, a subset of learners prefers the straightforwardness and realism of traditional case studies, especially for targeted review and test preparation. Many respondents ultimately advocate for a balanced or blended approach, leveraging the best of both CCNs and conventional case-based learning to maximize engagement, retention, and clinical relevance.

4. Discussion

The use of cinematic clinical narratives (CCNs) in pharmacology lectures demonstrated a significant impact on learning outcomes when compared with traditional text-based cases. The results showed that CCNs improved material retention, leading to higher exam scores on antiparasitic pharmacology topics. Furthermore, student satisfaction, as assessed by the SIS-M survey, indicated a marked preference for CCN-based learning materials. These findings suggest that CCNs effectively reduce cognitive load by presenting contextually meaningful and memorable content, a stark contrast to the static and often disengaging nature of traditional text-based cases. While text-based cases remain a valuable tool for delivering large quantities of information efficiently, the immersive and engaging narratives inherent to CCNs enhance retention and comprehension by making complex material more approachable and enjoyable.

The increased engagement and intrinsic motivation observed among students further underscore the value of CCNs. The SIS-M survey revealed that students found the CCNs not only preferable but also more engaging than traditional text-based cases. By transforming challenging pharmacology concepts into captivating, memorable experiences, CCNs foster intrinsic motivation, encouraging students to take ownership of their education. Self-determination theory posits that intrinsically motivated learners exhibit higher engagement and are more likely to pursue knowledge independently [

28,

29,

30]. Visual aids and mnemonics featured in the CCNs, such as likening helminth parasites to

Dune-inspired sandworms, likely played a pivotal role in driving this engagement and facilitating memory retention. Such creative approaches elevate the learning experience beyond rote memorization, providing students with vivid, lasting impressions of the material.

Generative AI was instrumental in the creation of the CCNs, highlighting its advantages in medical education. Although the precise role of AI in academia continues to evolve [

31,

32], genAI has proven to be a powerful tool for developing visually engaging and contextually rich educational materials. By streamlining the production of high-quality resources, genAI democratizes access to engaging learning materials, enabling educators to produce personalized content rapidly [

33]. Previously, creating such materials would have required significant time and effort from skilled artists and writers, resources often unavailable to educators. GenAI bridges this gap, empowering instructors to meet the diverse needs of their students while reducing the cognitive burden associated with traditional learning methods. By optimizing learning objectives through personalized content, students can focus on meaningful engagement rather than the mechanics of studying, fostering a more equitable and accessible educational environment.

While the CCNs discussed here focused on antiparasitic pharmacology, this approach is readily applicable to other specialties, including pathology, embryology, or other content-intensive fields beyond medicine. Thought-provoking and enjoyable educational materials show promise in boosting retention and comprehension while also battling the burnout often experienced by high-performing students who may lack access to engaging and personalized resources. By adopting innovative strategies like CCNs, educators can better meet the needs of their students, fostering a positive and resilient approach to learning.

4.1. Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the novelty of both generative AI and cinematic case-based narratives (CCNs) in medical education may have artificially amplified student engagement. It is plausible that the originality of this new approach, rather than genuine interest in the material, contributed to the observed increase in engagement. This phenomenon, often referred to as the novelty effect [

34], may diminish over time as students become more familiar with these methods. Larger, longitudinal studies are necessary to determine whether the positive effects of CCNs and generative AI persist over the long term and across diverse educational settings.

Second, while genAI significantly reduces the time and resources required to create engaging educational materials, there are legitimate concerns about over-reliance on this technology. Dependence on genAI may present challenges for educators, particularly in institutions with limited access to technological infrastructure or where funding constraints hinder the adoption of AI-based tools. Additionally, there is a risk that the use of generative AI could reduce the development of creative and pedagogical skills among educators, as reliance on automated tools may discourage innovation and hands-on material creation.

Third, the study was conducted within a single pharmacology course and focused on a specific set of topics (antiparasitic pharmacology), which may limit the generalizability of the findings. While CCNs demonstrated positive outcomes in this context, their effectiveness across other medical disciplines, such as pathology or anatomy, remains to be evaluated. Further research is required to explore the applicability of CCNs to various specialties and student populations. Furthermore, CCNs may run the risk of making already difficult content more confusing in cases where students are not familiar with the pop culture/entertainment franchise utilized by the CCN.

Finally, the integration of genAI in educational settings raises ethical concerns, particularly regarding the accuracy and appropriateness of AI-generated content. While efforts were made to ensure the quality and relevance of the materials produced for this study, the potential for errors or biases in AI-generated content underscores the need for careful review and oversight. As generative AI continues to evolve, guidelines and best practices for its use in medical education must be established to mitigate these risks and ensure equitable access to its benefits.

Addressing these limitations through future research and practice will be essential to fully realize the potential of genAI and CCNs in medical education while minimizing their drawbacks.

5. Conclusions

The integration of cinematic clinical narratives (CCNs) with genAI has demonstrated promising potential for enhancing educational outcomes and engagement among medical students. The observed improvements in exam performance and the clear preference for CCNs over traditional text-based cases underscore the value of this innovative approach. By making medical education more enjoyable and memorable, CCNs provide a scalable and equitable framework for producing learning materials that inspire enthusiasm and engagement in high-stakes learning environments, historically a significant challenge in medical education.

While concerns about the novelty effect and the accessibility of this approach remain valid, the findings of this study highlight the importance of continued exploration and refinement of creative educational tools, such as the utilization of genAI. These technologies offer unique opportunities to address the cognitive and emotional demands of medical training, paving the way for more effective and equitable learning experiences. As medical education evolves, prioritizing the development and implementation of such innovative strategies will be critical to meeting the needs of future generations of healthcare professionals.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Presentation S1: Antiparasitic pharmacology lecture slides; Video S1: Alien-Parasites Within short film; Video S2: Wormquest short film; ComfyUI S1: Anime character sheet workflow; ComfyUI S2: Flux.1 dev workflow; ComfyUI S3: LivePortrait workflow; Methods S1: Optimized prompt for script generation; Methods S2: ChatGPT 4o generation of the mnemonic Like a G6 song lyrics; Video S3: Making of the Alien-Parasites Withing short film; Table S1: SIS items.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Benjamin Worthley and Tyler Bland; Data curation, Tyler Bland; Formal analysis, Meize Guo and Tyler Bland; Investigation, Benjamin Worthley and Tyler Bland; Methodology, Lucas Sheneman and Tyler Bland; Resources, Lucas Sheneman; Supervision, Tyler Bland; Visualization, Tyler Bland; Writing – original draft, Benjamin Worthley and Tyler Bland; Writing – review & editing, Meize Guo and Tyler Bland.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved exempt by the institutional review board of the University of Idaho (21-223).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the sensitive nature of students’ grades. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Tyler Bland (tbland@uidaho.edu).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the Idaho site students for their participation in this study, Dr. Fehrenkamp at the University of Idaho for her review of the achievement tests, and Ciara Bordeaux for the Medimon animations.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| genAI |

Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| CCN |

Cinematic Clinical Narrative |

| SIS-M |

Situational Interest Survey for Multimedia |

References

- Klatt, E.C.; Klatt, C.A.M. How Much Is Too Much Reading for Medical Students? Assigned Reading and Reading Rates at One Medical School. Acad. Med. 2011, 86, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Densen, P. Challenges and opportunities facing medical education. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2011, 122, 48–58. [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast, M.; Pinto, A.M.C.; Harvey, C.-J.; Muir, E. Burnout in early year medical students: experiences, drivers and the perceived value of a reflection-based intervention. BMC Med Educ. 2024, 24, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenu, S.; Zachariah, A.M.; Balakrishnan, S. Effectiveness of mnemonics based teaching in medical education. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 9635–9640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, F.S. Mnemonic Devices: Classification, Characteristics, and Criteria. Rev. Educ. Res. 1981, 51, 247–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajayi, T.A.; Shaw, D.; Edmonds, K.P. Feasibility and Effectiveness of a Mnemonic Approach to Teach Residents How to Assess Goals of Care. J. Palliat. Med. 2019, 22, 696–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksakal, N. Theoretical View to The Approach of The Edutainment. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 186, 1232–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, A.; Deviatnikova, K. Edutainment as a New Educational Technology: A Comparative Analysis. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems 2023, 830, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, T. Enhancing Medical Student Engagement Through Cinematic Clinical Narratives: Multimodal Generative AI–Based Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Med Educ. 2025, 11, e63865–e63865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, S.; Ramakrishnan, R.; Durairaj, E.; Das, A. Artificial Intelligence Revolutionizing the Field of Medical Education. Cureus 2023, 15, e49604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- S. N. Chu and A. J. Goodell, “Synthetic Patients: Simulating Difficult Conversations with Multimodal Generative AI for Medical Education,” May 2024, Accessed: Jan. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.19941v1.

- Chassignol, M.; Khoroshavin, A.; Klimova, A.; Bilyatdinova, A. Artificial Intelligence trends in education: a narrative overview. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 136, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Aktay, “The usability of Images Generated by Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Education,” International Technology and Education Journal, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 51–62, Dec. 2022, Accessed: Sep. 19, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/itej/issue/75198/1233537.

- Y. Ma et al., “Promoting AI Competencies for Medical Students: A Scoping Review on Frameworks, Programs, and Tools,” Jul. 2024, Accessed: Jan. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.18939v1.

- C. Yang et al., “Large Language Models as Optimizers,” 12th International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2024, Sep. 2023, Accessed: Jan. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.03409v3.

- NEW VIDEO + WORKFLOWS] Make your own ANIME with this new mind-blowing AI TOOL! | Patreon.” Accessed: Jan. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.patreon.com/posts/new-video-make-106483196.

- glif - Flux Prompt Enhancer by, AP. ” Accessed: Jan. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://glif.app/@angrypenguin/glifs/clzbm2qvb000113zgz4a9r1wj.

- LivePortrait Omni(LivePortrait 全能版) | ComfyUI Workflow.” Accessed: Jan. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://openart.

- Dousay, T.A. Effects of redundancy and modality on the situational interest of adult learners in multimedia learning. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2016, 64, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dousay, T.A.; Trujillo, N.P. An examination of gender and situational interest in multimedia learning environments. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 50, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, T.; Guo, M.; Dousay, T.A. Multimedia design for learner interest and achievement: a visual guide to pharmacology. BMC Med Educ. 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, T.; Guo, M.; Dousay, T.A. Multimedia design for learner interest and achievement: a visual guide to pharmacology. BMC Med Educ. 2024, 24, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Wu, Z.; Ma, C.; Yu, S.; Dai, H.; Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. Review of large vision models and visual prompt engineering. Meta-Radiology 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. White et al., “A Prompt Pattern Catalog to Enhance Prompt Engineering with ChatGPT,” Feb. 2023, Accessed: Sep. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2302.11382v1.

- T. Kojima, S. S. T. Kojima, S. S. Gu, M. Reid, Y. Matsuo, and Y. Iwasawa, “Large Language Models are Zero-Shot Reasoners,” Adv Neural Inf Process Syst, vol. 35, 22, Accessed: Sep. 23, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2205.11916v4.

- Huang, J.; Gu, S.; Hou, L.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yu, H.; Han, J. Large Language Models Can Self-Improve. Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Singapore; pp. 1051–1068.

- J. Wang, J. J. Wang, J. Wang, T. Ai, B. A. Together, C. Zhang, and J. Zou, “Mixture-of-Agents Enhances Large Language Model Capabilities,” Jun. 2024, Accessed: Jan. 08, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.04692v1.

- Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Wind, S.A.; Gill, C. A systematic review and meta-analysis of self-determination-theory-based interventions in the education context. Learn. Motiv. 2024, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R. Ryan, E. D.-A. R. Ryan, E. D.-A. psychologist, and undefined 2000, “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.,” psycnet.apa.orgRM Ryan, EL DeciAmerican psychologist, 2000•psycnet.apa.org, 1985, Accessed: Jan. 09, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://psycnet.apa.org/journals/.

- Cate, O.T.T.; Kusurkar, R.A.; Williams, G.C. How self-determination theory can assist our understanding of the teaching and learning processes in medical education. AMEE Guide No. 59. Med Teach. 2011, 33, 961–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irfan, M.; Murray, L.; Ali, S. Integration of Artificial Intelligence in Academia: A Case Study of Critical Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Glob. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2023, VIII, 352–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, D.; Fagan, T.R.; Wright, J.T. ChatGPT. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2023, 154, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F.; Calonge, D.S.; Gurrib, I. New Era of Artificial Intelligence in Education: Towards a Sustainable Multifaceted Revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Novelty Effect in Large Display Deployments - Experiences and Lessons-Learned for Evaluating Prototypes,” ECSCW Exploratory Papers, 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).