1. Introduction

Nephrology is traditionally a difficult subject for medical students to learn during their preclinical training. The concept of acid-base metabolism in particular is especially difficult to master due to its inherent complexity and the current limitations in the approach to teaching it (Leehey & Daugirdas, 2016). Instructors, drawing from their own expertise, often default to methods that make intuitive sense to them—such as dense, text-heavy flowcharts and lists of lab values—but these approaches can overwhelm novices with excessive cognitive load, leading to confusion, disengagement, and reduced learning (Besche et al., 2025; Evans et al., 2024; Tackett et al., 2022). The sterile nature of these charts not only makes them hard to follow, but also to retain and recall when attempting to formulate diagnoses for patients (Lyra et al., 2016).

Perhaps the biggest failure of this current approach to teaching acid-base metabolism is that it fails to adequately address the high cognitive load associated with learning it (Sweller, 1994; Young et al., 2014). While attempting to learn, a person must funnel new information through their working memory, a hypothetical space in the conscious mind that is unfortunately quite limited in size (Ghanbari et al., 2020). The high complexity of these disorders can easily surpass the capacity of the working memory (Cowan, 2001). To effectively diagnose these disorders, a person must hold onto a broad range of acceptable lab values (e.g., for arterial carbon dioxide), understand the extent to which other organ systems attempt to compensate for changes in blood pH, and recognize situations in which multiple disorders are occurring simultaneously (Morikawa & Ganesh, 2025).

Thankfully, there are a handful of studying tools capable of addressing the issue of cognitive load, such as mnemonics and algorithms. Mnemonics refer to any sort of image, pattern, phrase, or other mental concept that aid in the retention of information via the process of dual-coding (Clark & Paivio, 1991). For example, rather than trying to memorize the order of colors in a rainbow by learning them individually, it is far simpler to just learn the mnemonic “Roy G. Biv” (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, violet). The same applies to other complicated material such as tax systems (Smith & Shimeld, 2014), or in the case of this study, the components involved in diagnosing acid-base disorders. An algorithm, on the other hand, refers to a systematic, stepwise approach to thinking that can be used to reach one of many end goals (e.g., a diagnosis). This formulated approach allows for mental streamlining by reducing the amount of cognitive load normally involved in trying to organize large chunks of information (Grover & Pea, 2013). In these ways, both mnemonics and algorithms help students to learn and retain information by reducing the high cognitive load associated with complex material.

Another avenue to help promote both increased motivation and learning is the utilization of serious games. These types of games provide entertainment in similar ways to any other type of game but are developed as tools that simultaneously educate players by incorporating learning material directly into the core aspects of the game(Avila-Pesántez et al., 2017). Serious games have been found to be effective in aiding students with long-term retention of course material (Fung & Oyibo, 2024). Zhao et al. (2025) built upon this growing interest in serious games with their incorporation of AI-generated characters (Zhao et al., 2025). The use of these generated characters not only increased student engagement with the game but additionally improved their absorption of the educational material.

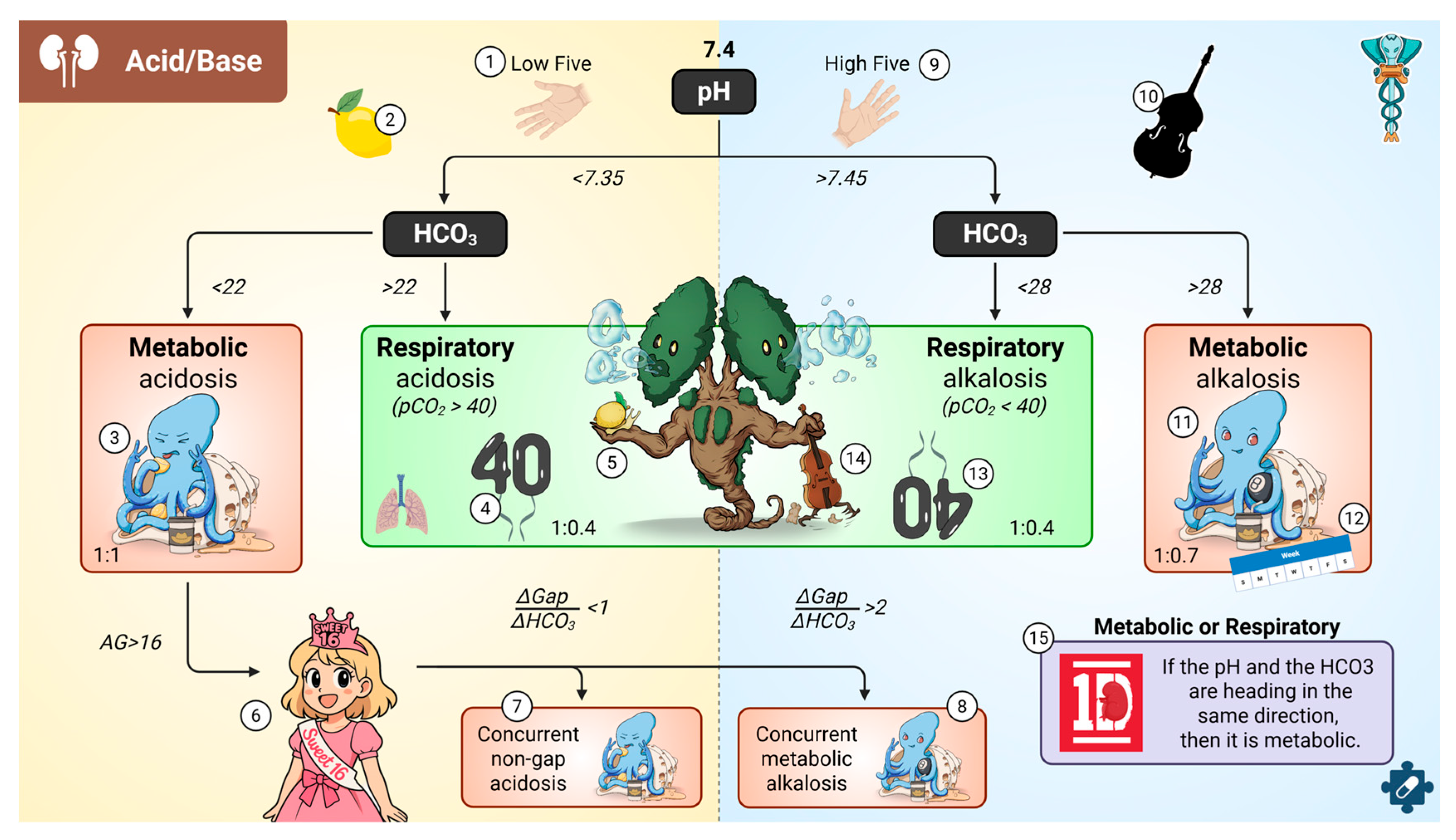

Capitalizing on the benefits of mnemonics, algorithms, and serious games, an education tool has been developed that synthesizes all three: Medimon (Bland & Guo, 2024; Hundrup et al., 2025; Singleton et al., 2025). Medimon is a serious, health science game that utilizes an extensive universe of characters and items with built-in visual mnemonics aimed towards helping students remember organ systems, disorders, pharmacologic treatments, and the key characteristics associated with each (Medimon - Fun and Engaging Medical Science Learning Game, n.d.). Recurrent characteristics between topics are utilized throughout the platform to retain consistent imagery and reduce cognitive load. For example, topics pertaining to pH will show characters interacting with a lemon (citric “acid”) or upright bass (alkaline base). In the case of acid-base metabolism, we utilized the Lung and Kidney characters, both systems that regulate body pH, in situations of both acidosis and alkalosis in an algorithmic fashion. Each character is positioned alongside important lab values involved in the diagnosis of acid/base disorders, allowing for strong, visual-based mnemonic associations to be formed between the values and the disorders.

To assess the impact of implementing this Medimon-centered acid-base algorithm, a portion of University of Washington School of Medicine students were provided with this learning tool while others not receiving the Medimon algorithm served as a control group. Short-term and delayed exam results were recorded. Situational interest and perceived usefulness of those provided with the Medimon algorithm were additionally collected via the use of a Situational Interest Survey for Multimedia (SIS-M). We hypothesized that there would be no difference in short-term scores between the student groups while long-term scores would be higher in those provided with the Medimon algorithm. We additionally hypothesized that high SIS-M scores would correlate with high levels of performance on the delayed exam.

2. Materials and Methods

This mixed-methods study was conducted within the WWAMI regional medical--education program, which delivers an identical pre-clerkship curriculum to first- and second-year medical students (MS1/MS2s) at six distributed campuses (Sites 1–5 = control campuses; Site 6 = experimental campus). All campuses followed the standard six-week Respiration & Renal (R & R) block schedule. The experimental campus integrated a visual-mnemonic algorithm featuring Medimon characters (Medimon algorithm), whereas the five control campuses used the traditional text-based flowchart only (original algorithm). The primary quantitative aim was to compare immediate and delayed achievement across sites; the secondary quantitative aim and qualitative aim were, respectively, to measure situational interest and explore learners’ explanatory comments about the two algorithms.

2.1. Participants

All enrolled MS1s at the six campuses were eligible (N = 273). A total of 231 students (n = 231) at control campuses and 42 students (n = 42) at the experimental campus completed the unit examination 7 days post-lecture. All but one control-campus student (n = 230) and all experimental campus students completed the final examination 11 days post-lecture. No demographic data were collected in order to maintain campus anonymity.

2.2. Intervention

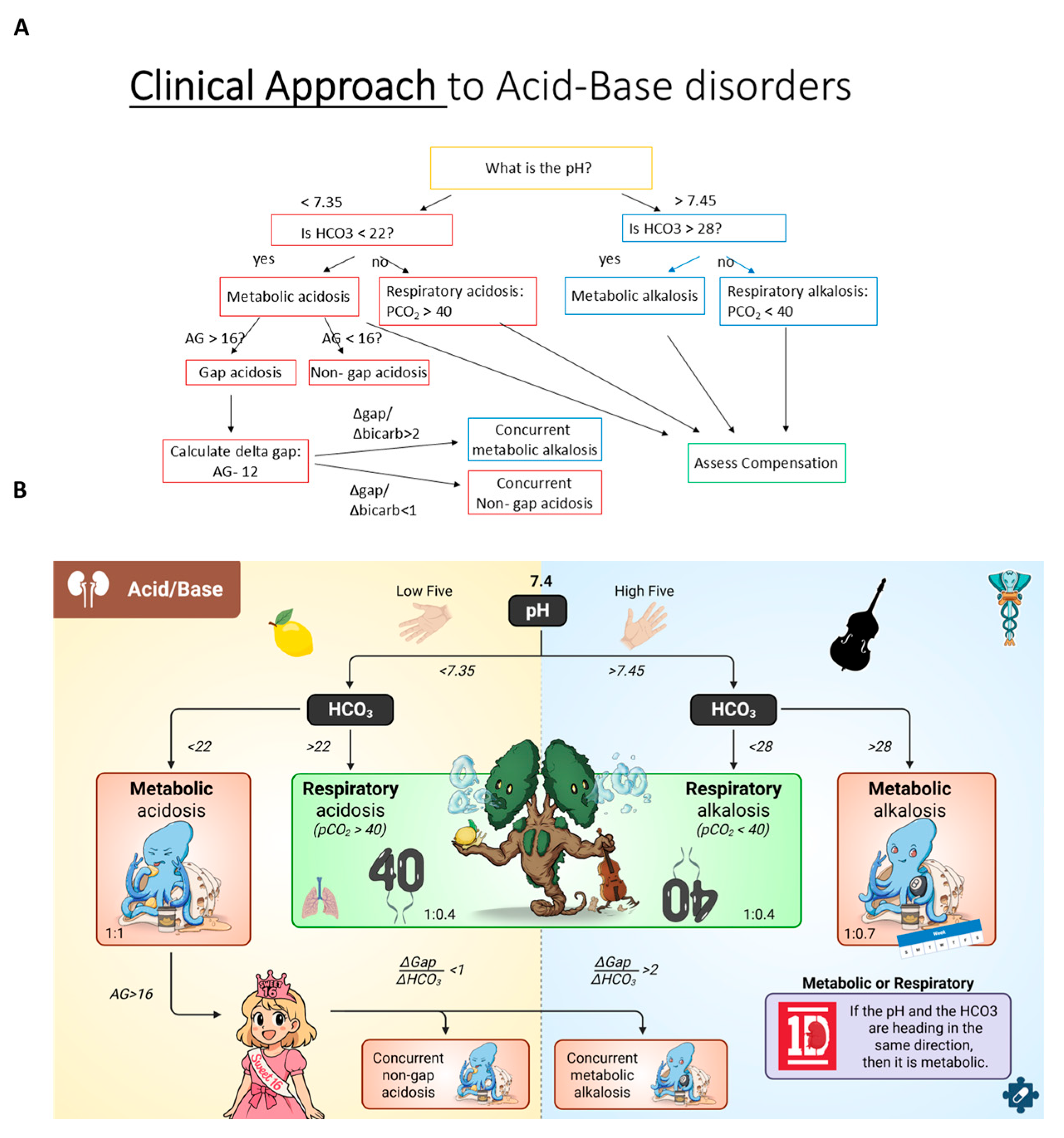

During the R&R block, all students were provided with an identical 60-minute live lecture on renal acid–base analysis, covering the diagnosis of metabolic acidosis/alkalosis, respiratory acidosis/alkalosis, and expected physiologic compensation. A text-based algorithmic flow diagram was provided to every student for use during problem solving (original algorithm,

Figure 1A). Students at the experimental site received, in addition, an illustrated algorithm that overlaid the diagnostic workflow with visual mnemonics (Medimon algorithm,

Figure 1B). A high-resolution image can be accessed at

https://blandpharm.com/renal-remedies

2.2.1. Medimon

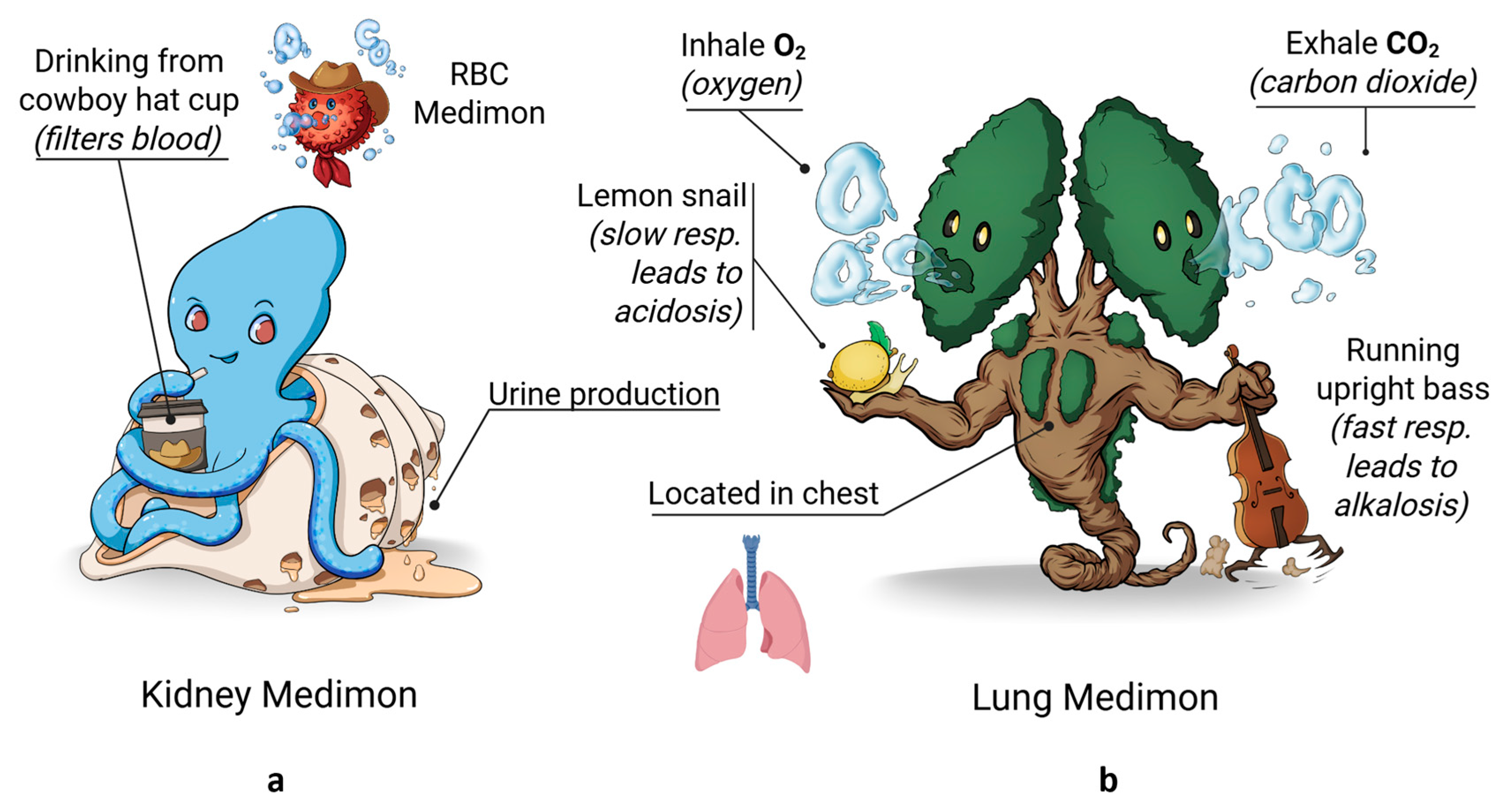

The Kidney Medimon and Lung Medimon served as central educational tools within the Medimon algorithm. The Kidney Medimon, representing the adult stage of the Kidney family, was conceptualized as an octopus-like creature encased in a shell (

Figure 2A). This design symbolized key functions such as blood filtration and urine production. In addition to the base version, two alternate Kidney Medimon variants were created with visual mnemonics illustrating acid/base balance, highlighting renal compensation mechanisms. The Lung Medimon, also in its adult stage, was depicted as a plant-like character to represent alveolar and bronchial structures and gas exchange (

Figure 2B). It incorporated both gas exchange and acid/base regulation mnemonics, aligning with the physiological role of the lungs in respiratory acid handling.

2.2.2. AI Image Generation

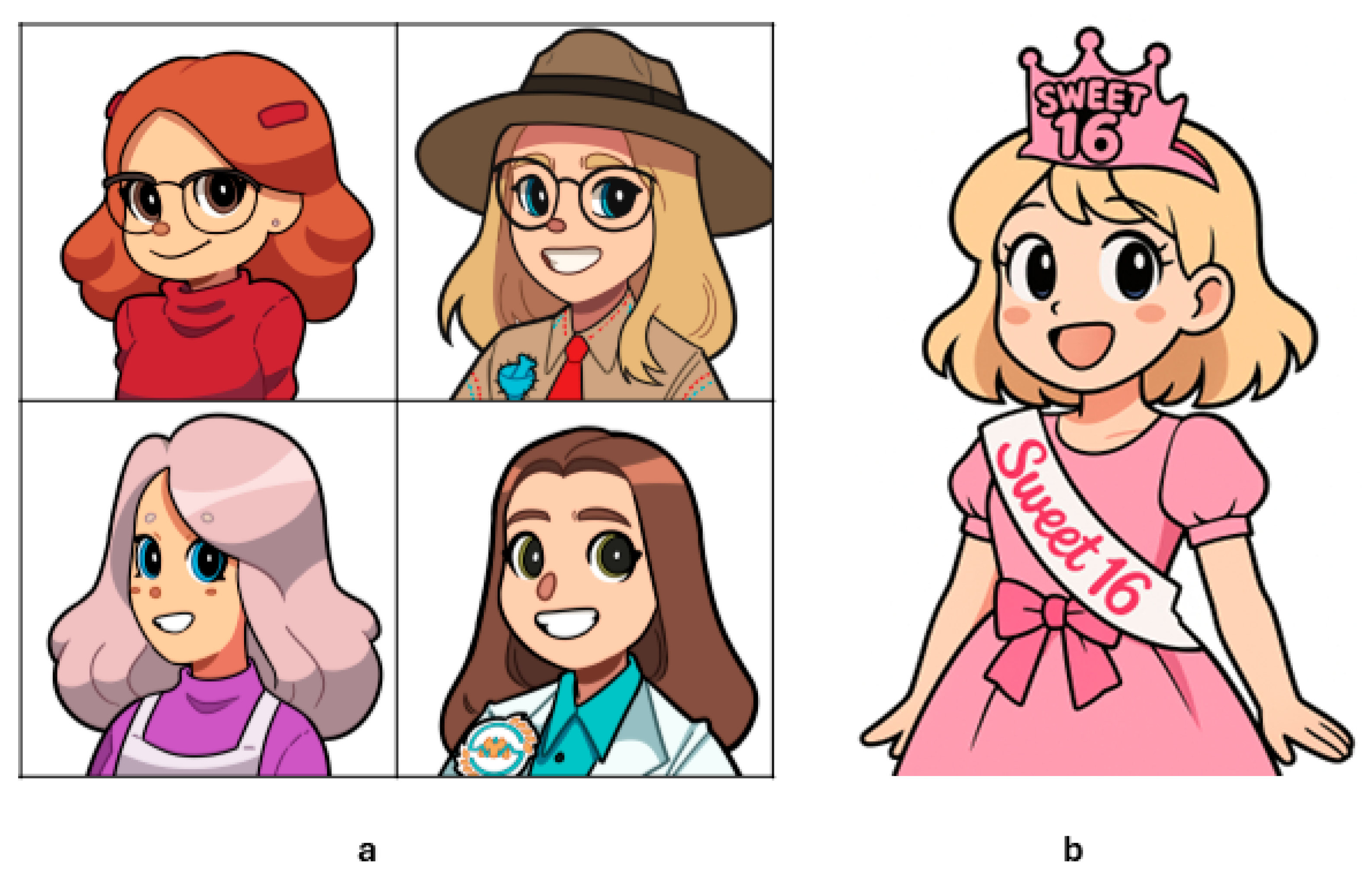

To supplement visual engagement, an additional character was created using the native image generation capabilities of ChatGPT 4o (

Figure 3). Four human artist-drawn Medimon non-playable character (NPC) images were provided as style references. The prompt utilized was: “Please generate an image of a character wearing a cute dress. She is also wearing a sweet “16” crown and a “Sweet 16” sash. Please match the art style of the attached images.” The platform was further used to remove the background of the generated image, allowing easy integration into the final Medimon algorithm.

2.2.3. Mnemonic Integration

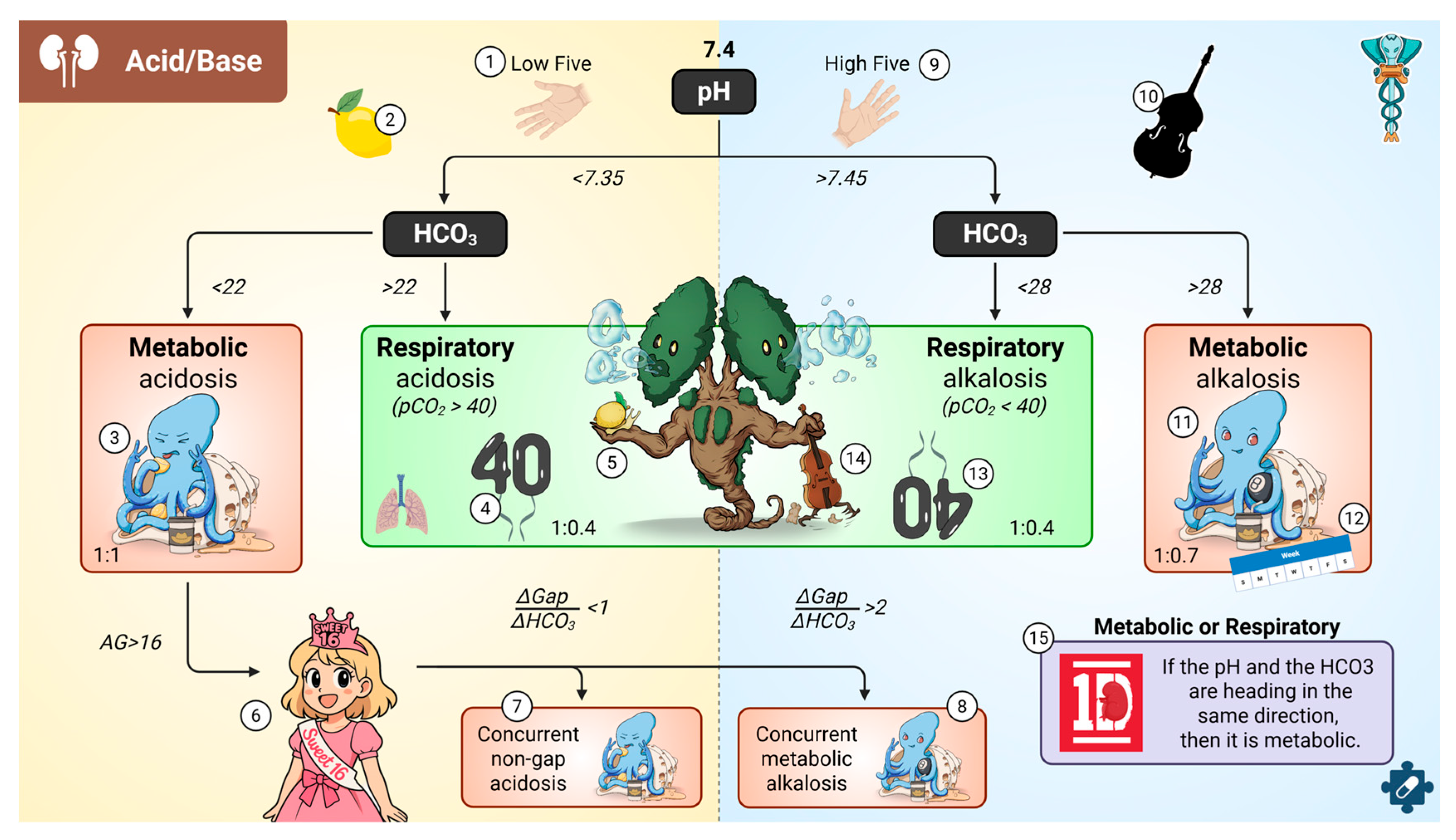

Visual mnemonics were systematically incorporated into the Medimon algorithm to enhance diagnostic recognition and recall (

Figure 4). These included Medimon character imagery, pop-culture references such as the logo for the band One Direction, and symbolic visual cues like lemons (for acidity), an upright bass (for base), and birthday balloons (for pCO

2 levels). Each visual element was chosen for its ease of recognition and visual connection to the underlying medical concept.

2.3. Assessments

Student learning was assessed through a multiple-choice unit examination administered seven days after the acid/base analysis lecture. This exam included nine questions specifically targeting content from the acid/base analysis lecture. A subsequent assessment occurred 11 days post-lecture as part of the cumulative course final exam, which included four acid/base-related questions. All students, regardless of site, received the same assessments at similar time points to ensure consistency across groups.

2.4. Data Collection

After course completion, students at the experimental site were invited to complete the Situational Interest Survey for Multimedia (SIS-M) (

Appendix A1) to assess their engagement with the two acid/base instructional formats. The survey required participants to provide consent and respond to the 12-item SIS-M twice—once while referencing the experimental image and once while referencing the original image. Each item was rated on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Additionally, the survey included a question asking students to indicate their preferred image format and an open-ended question prompting them to explain their preference. Participants who completed the SIS-M survey received a

$5 gift card as a thank you for their participation.

2.5. Data Analysis

2.5.1. Achievement

Microsoft Excel and ChatGPT o3 were utilized to analyze the achievement results (Alomar et al., 2025; Hundrup et al., 2025). Because only campus-level aggregate item data were available, percent-correct means for each exam question were treated as group scores. Items were categorized as focal (acid–base) or baseline (all other content). A Differences-in-Differences (DiD) approach compared (i) focal vs. baseline performance within each campus and (ii) the resulting difference between Site 6 and the individual and pooled control campuses. A Welch t-test with exact two-sided p values were calculated and Hedges g quantified effect size.

2.5.2. SIS-M Quantitative

SIS-M data were analyzed using SPSS (30.0.0.0 (172)). Paired t-tests were conducted across four dimensions of situational interest—triggered situational interest (Trig), maintained situational interest-total (MT), maintained situational interest-feeling (MF), and maintained situational interest-value (MV)—to compare student responses to the original and experimental image formats.

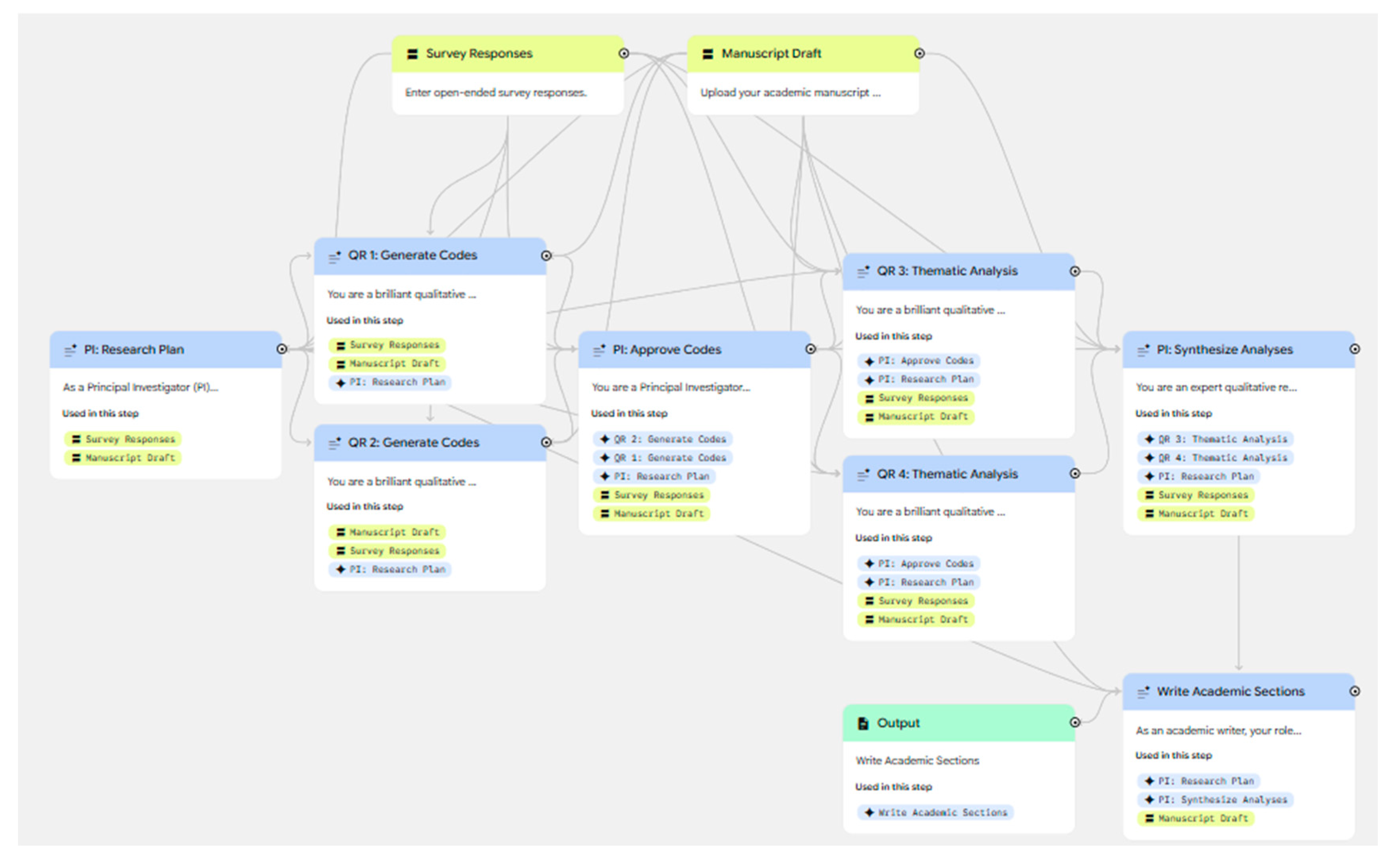

2.5.3. SIS-M Thematic Analysis

The open-ended survey responses from the experimental site were analyzed using a generative artificial intelligence (genAI)-assisted thematic analysis pipeline developed on the Google Opal platform (Welcome - Opal [Experiment], n.d.). This custom web application was designed to operationalize an agentic large language model (LLM) workflow, leveraging three types of role-specific agents powered by the Gemini 2.5 Pro (thinking model). Each agent was assigned a distinct system prompt that defined its responsibilities in the analytic process (Methods S1). The application allowed the user to supply both the raw survey responses and the rough manuscript draft, providing context to the agents and enabling alignment between coding, theme development, and manuscript framing. The workflow was organized into six sequential stages:

Planning (PI Agent): The Principal Investigator (PI) agent analyzed the full set of survey responses and the draft manuscript. Based on this input, the agent produced a detailed, stepwise plan for conducting the thematic analysis.

Initial Coding (QR Agents): The plan was independently executed by two Qualitative Researcher (QR) agents. Each QR agent performed initial coding of all survey responses, generating codebooks that reflected distinct interpretive perspectives.

Code Review (PI Agent): The PI agent reviewed the two independent codebooks, identifying overlapping codes, resolving disagreements, and refining the code structure to maintain coherence and analytic rigor.

Theme Generation (QR Agents): The revised coding framework was then passed to two additional QR agents, who independently organized the codes into higher-order categories and articulated candidate themes.

Synthesis (PI Agent): The two independent thematic analyses were reconciled by the PI agent, who synthesized them into a single cohesive set of themes, ensuring that all salient ideas from the student responses were represented.

Manuscript Integration (Academic Writer Agent): Finally, the synthesized thematic analysis was provided to an Academic Writer agent. This agent integrated the themes into narrative text aligned with the manuscript draft, producing prose that was ready for inclusion in the Results and Discussion sections.

Although the workflow was automated through the genAI agents, researcher oversight was maintained throughout. At the end of the process, human investigators reviewed the final themes and supporting exemplar quotes to ensure validity and faithfulness to the original data. Discrepancies or interpretive ambiguities were resolved by consensus among the research team (

Figure 5). The application can be accessed at

https://opal.withgoogle.com/?flow=drive:/1g2tSryKKFjRUh6Gm4bO9Cokh5FC8N-WP&shared&mode=app

2.6. Ethical Considerations

The University of Idaho Institutional Review Board determined the study was exempt (protocol 21-223). All students received routine instruction independent of research participation; survey participation was voluntary and anonymous. OpenAI’s terms grant users ownership of generated images, and no sprite depicted any real individual, mitigating privacy concerns.

3. Results

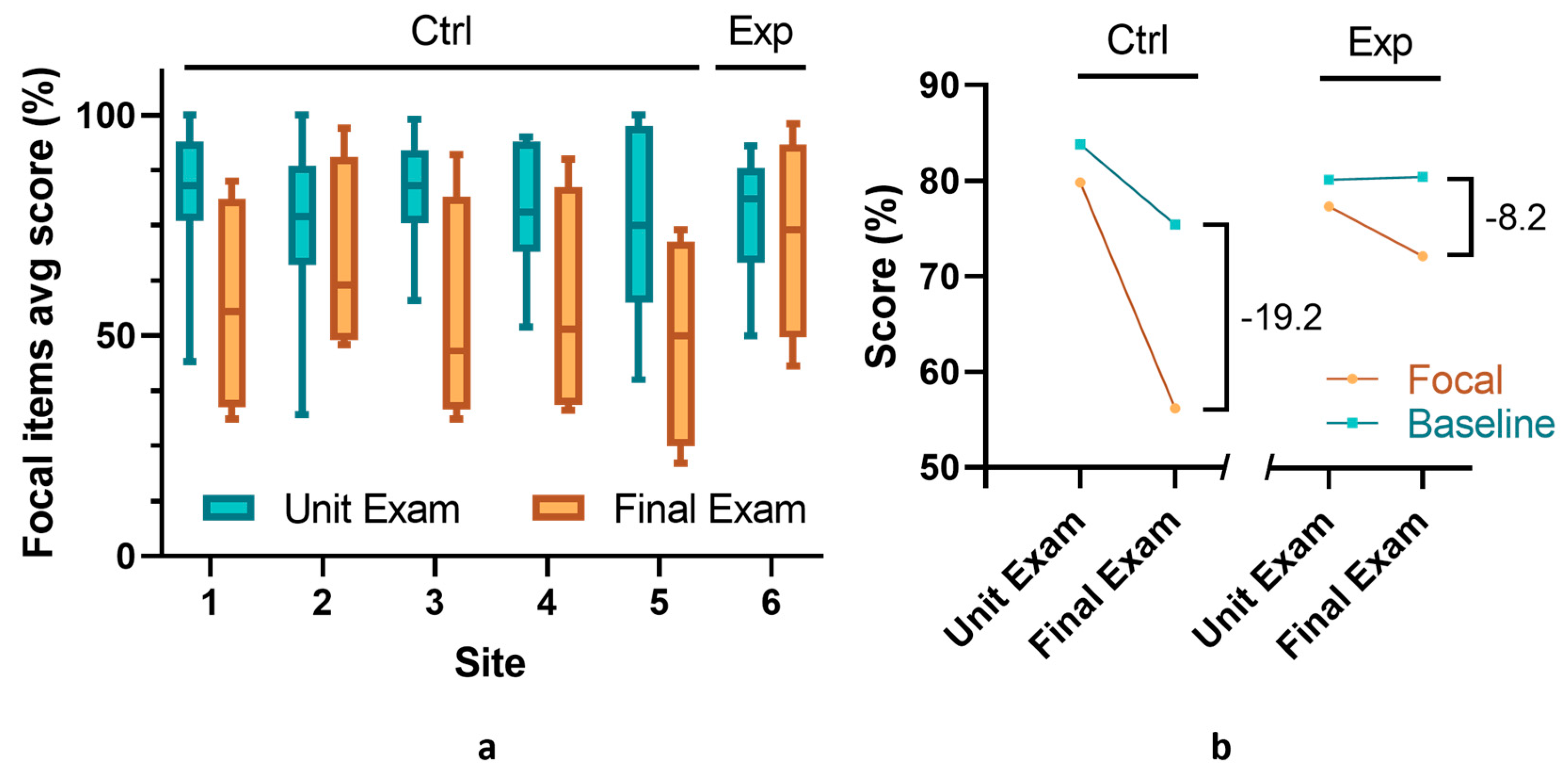

3.1. Achievement

Across both assessments, 273 first-year medical students completed the unit exam and 272 completed the final exam. The experimental site contributed 42 students; the remaining 231 students were distributed across the five other peer sites (1-5). Each exam contained a small set of “focal” items that mapped directly to the instructional innovation (9 items on the unit exam; 4 items on the Final exam,

Figure 6) and a much larger block of “baseline” items covering the other content taught in the course.

The instructional effect was evaluated with a difference-in-differences (DiD) approach (

Figure 6B,

Table 1). For each site we first calculated the drop in performance from the untargeted baseline items to the focal items that were taught with either the original or Medimon algorithms. This within-site contrast normalizes the analysis to each group’s overall ability level. We then subtracted the individual control sites contrast and the pooled weighted average of the five control sites from the contrast of the experimental site (

Table 1, Appendix Table B1 and B2). If the Medimon algorithm added value, its focal-item drop should be smaller, producing a positive DiD estimate. When comparing the contrast of the weighted pool of the control sites and the experimental site on the unit exam, the DiD estimate was positive but small and did not reach significance (DiD = +1.2 , p = 0.612), and became larger but still not statistically significantly on the final exam (DiD = +11.0, p = 0.272). Thus, once general test performance was held constant, the experimental site showed no early advantage but a trending end-of-course gain on the targeted material.

To gauge the practical magnitude of those differences we computed Hedges g (

Table 1). On the unit exam the experimental site outperformed their peers on focal items once adjusted for baseline performance by a small effect (g = 0.12; 95% CI –0.62 to 0.86). By the final exam, the experimental site students outperformed their peers by a medium-to-large effect size (g = 0.85; CI -0.17 to 1.87). Together, the DiD and effect-size results indicate that the Medimon algorithm had little immediate impact but was associated with a large, statistically insignificant, but trending, improvement on the specific learning objectives by the end of the course.

3.2. SIS-M Quantitative

From the 42 experimental site participants, a total of 39 students (n=39) completed and submitted the SIS-M. Among the 39 participants, a substantial majority (n=36, 92%) indicated a preference for the learning materials embedded within Medimon algorithm, while a small proportion (n=3, 8%) expressed no preference. No participants responded that they preferred the original algorithm over the Medimon algorithm.

To evaluate potential differences in situational interest between using the Medimon algorithm and original algorithm, four paired sample t-tests were conducted. These analyses focused on four dimensions of situational interest: triggered situational interest (Trig), maintained-feeling interest (MF), maintained-value interest (MV), and overall maintained interest (MT). As presented in

Table 2, the findings demonstrated statistically significant differences across all situational interest dimensions.

Participants reported significantly higher levels of triggered situational interest (Trig) when interacting with the Medimon algorithm (M=4.47, SD=0.77), compared to the original algorithm (M=1.85, SD=0.67), t=16.04, p<.001. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was 2.29 to 2.95, indicating a strong preference for the Medimon algorithm.

Similarly, the Medimon algorithm elicited greater maintained-feeling (MF) interest (M=4.35, SD=0.81) than the original algorithm (M=2.89, SD=1.11), t=8.08, p<.001. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was 1.10 to 1.83.

The outcomes for maintained-value (MV) interest suggested that the participants’ interest rating of the Medimon algorithm (M=4.67, SD=0.79) was significantly different from that of the original algorithm (M=3.74, SD=1.08), t=5.58, p<.001. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was 0.59 to 1.26.

Finally, the overall maintained interest (MT) scores were also significantly higher for the Medimon algorithm (M=4.51, SD=0.76) compared to the original algorithm (M=3.31, SD=0.98), t=7.53, p<.001. The 95% confidence interval for the mean difference between the two ratings was 0.87 to 1.51.

Thematic Analysis

A thematic analysis of the 39 open-ended responses from students in the experimental group was conducted to explain the significant quantitative preference for the Medimon algorithm. Four primary themes were identified: (1) Enhanced Clarity and Cognitive Accessibility; (2) Improved Memorability and Recall via Visual Mnemonics; (3) Increased Engagement and Affective Appeal; and (4) Barriers to Use and Interpretation. These themes are summarized in

Table 3.

The most prevalent theme was the Medimon algorithm’s superior clarity and organizational structure, which participants reported as reducing the cognitive load of learning acid-base metabolism. Students repeatedly described the experimental resource as “easier to follow” (P1, P4, P8, P21, P30), “more organized” (P12, P15, P23), “streamlined” (P3), and having a “more natural flow” (P14). This improved structure provided a logical and intuitive pathway through the diagnostic process. As one participant stated, the algorithm “outlined the approach to Acid/Base in a logical way. The original algorithm presented in the slides did neither” (P30). This clarity contrasted sharply with perceptions of the traditional flowchart, which one student characterized as “an example of exactly what not to do with technical communication... less organized and more difficult to follow” (P6). By simplifying the thinking process, the experimental design was perceived as “less overwhelming to look at” (P20) and “less daunting” (P29).

The second major theme relates to the powerful role of visual mnemonics in enhancing memory, consistent with dual-coding theory. Participants reported that the integration of images, characters, colors, and symbols created robust mental anchors that facilitated learning and recall. As one student noted, “Visual mnemonics... can help the flow of information to better stick and be retrieved later” (P9). This enhanced memorability had clear practical benefits for assessment, helping students “remember important numbers for the exam” (P1) and internalize the algorithm so effectively they could form a “mental map” (P3) and “easily imagine the image in my head while doing practice questions and while taking the exams” (P4). This approach also increased learning efficiency, as one participant noted, “I had the new algorithm mostly memorized after the first time I saw it” (P24).

Participants’ preference was also strongly driven by the algorithm’s ability to generate interest and positive affect, directly corresponding to the high situational interest scores observed quantitatively. The resource was frequently described in aesthetic terms, such as “visually appealing” (P3, P25, P26, P38), “visually interesting” (P19), and “captivating” (P13, P39). This visual appeal served to “visually [grab] my attention” (P10) and “kept my attention while studying” (P4). Beyond aesthetics, the perceived quality and effort invested in the design appeared to enhance the material’s perceived value and credibility. One student commented, “Seeing someone put effort into a branching diagram makes it easier to take seriously” (P7), while another cited “trust in the brand” (P38).

While the vast majority favored the Medimon algorithm, a small subset of responses offered a crucial counterpoint. Two participants indicated a lack of significant engagement with either resource (“I didn’t really use either algorithm,” P16; P32). More substantively, one student who expressed no preference noted a key drawback of the mnemonic-heavy approach: “sometimes I would need to refer back to original if I didn’t make my own key to decipher the medimon algo” (P37). This comment suggests that while the visual mnemonics were effective for most, their symbolic nature was not universally intuitive and could represent a potential limitation of the design.

4. Discussion

As hypothesized, the Medimon algorithm served as a strong tool for long-term retention in medical students. While there was a slight difference between site scores on the unit exam (DiD = +1.2%, p = 0.612), there was a much larger increase in scores on the final exam for the experimental site (DiD = +11.0%, p = 0.272), suggesting that the algorithm directly led to an improvement in retention. The results of the SIS-M additionally confirm that the experimental site strongly preferred the Medimon algorithm to the original alternative. Paired sample T-tests for each of the four dimensions of situational interest returned values with p < 0.001 in favor of the Medimon algorithm.

The results of this study provide additional evidence for, and build upon previous research into, the benefits of specialized learning tools. As suggested by Clark and Paivio (1991), the mnemonic offered students an ideal way to dual-code the information they were presented (Clark & Paivio, 1991). This was strongly supported by our qualitative findings, in which students reported that the algorithm’s visual elements helped them create a “mental map” that was easily retrieved during exams, a core component of the theme Improved Memorability and Recall via Visual Mnemonics. The pairing of salient visual cues with key information significantly boosted their retrieval of the content in the long term. The simple, yet memorable, flow of the algorithm additionally helped to decrease the students’ cognitive load while attempting to learn the content, allowing them to absorb it much more freely (Grover & Pea, 2013). This finding was corroborated by our primary qualitative theme, Enhanced Clarity and Cognitive Accessibility, where students repeatedly described the experimental resource as “easier to follow,” “less overwhelming,” and “streamlined.” As for the use of AI-generated characters, their incorporation into the mnemonic clearly lead to a high level of engagement and interest, supporting similar findings from other groups (Zhao et al., 2025). This aligns with our third theme, Increased Engagement and Affective Appeal, where students found the algorithm “visually appealing” and “captivating,” which in turn fostered trust and perceived value. Their unique designs, fun imagery, and pop culture references all played a role in eliciting students’ triggered interest, a critical aspect of learning as explained by situational interest theory (Bernacki & Walkington, 2018).

These findings support the results of our other Medimon-involved studies as well. Medimon has been presented to medical students through a variety of different media types such as pictures (Bland & Guo, 2024), playing cards (Singleton et al., 2025), and even educational short films (Worthley et al., 2025). Our research studies on these short films, or Cinematic Clinical Narratives (CCNs), which integrated Medimon characters, showed both increased student learning and long-term memory as well as increased student preference over traditional materials (Worthley et al., 2025). The current study’s results showed a similar, positive impact on retention and engagement with medical school curricula, further supporting the integration of Medimon into medical school pre-clinical curriculum.

The current study boasts a number of important strengths. The multi-institutional design allowed for a more diverse sample of students than if it had been performed within just one institution. Additionally, each student received the same base lecture and the same exam questions, allowing for a high degree of consistency between learning sites. The implementation of the SIS-M component of the study provided information on the perspective of the learners in addition to their performance, thus adding another dimension to help understand the full impact of the Medimon algorithm. This study is also innovative in that it is the first to make use of a pop culture-themed Medimon algorithm for teaching acid-base metabolism.

However, the current study is not without its limitations. The assignment of learning sites to the control and experimental conditions was non-randomized, opening the study to potential institutional confounds. The number of questions that were sampled was also limited with only 9 (unit test) + 4 (final exam) questions pertaining to acid-base metabolism, thus leading to a small amount of achievement data to pull from. It should also be noted that SIS-M data was only collected from the experimental site, so there is no comparative data available from the control sites. Additionally, the time between the unit test and the final exam was only four days long. This stretch of time may be too short to effectively represent the jump from short-term to long-term retention. Finally, the qualitative data revealed an important counterpoint in the theme Barriers to Use and Interpretation, where a minority of students found the symbols difficult to decipher without a key, suggesting that the mnemonic approach may not be universally optimal for all learners.

Further research is still needed to learn more about the effectiveness of Medimon-inspired algorithms. Future studies can provide evidence of its teaching benefits for a wider variety of medical topics beyond acid-base metabolism. They can also be used to address some of the limitations of the current study such as utilizing a randomized control trial to avoid institutional and student confounds between the control and experimental groups. Future studies can also incorporate larger numbers of test questions to pull data from, as well as longer periods of time between the short-term and long-term memory tests. In addition to addressing these limitations, further study of these Medimon algorithms could include qualitative assessments for how students actually use the tool while problem solving, providing greater insight into how it leads to such a significant increase in retention.

5. Conclusions

The Medimon algorithm for acid-base metabolism demonstrated a clear benefit for the preclinical education of medical students. Those that were provided with this tool tested higher on related questions during their final exam, reflecting a substantial increase in their retention of the course material. Students additionally expressed a strong preference for the Medimon algorithm as opposed to the original flowchart. They showed increased engagement with the material, as well as increased situational interest while using the Medimon algorithm. The improved engagement and test scores both suggest that serious game-inspired materials and mnemonics integrated into clinical algorithms are promising learning tools that can be easily incorporated into medical school curriculum. Further research, development, and implementation of these tools have the potential to improve learning outcomes by utilizing new technological improvements to more effectively convey complex information.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: Preprints.org, Methods S1: System prompts for Google Opal app agents.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization T.B.; data curation, C.M. and T.B.; formal analysis, C.M., M.G., and T.B.; investigation, T.B.; methodology, C.M. and T.B.; visualization, T.B.; writing—original draft, C.M., H.H., M.G., and T.B.; writing—review and editing, C.M., H.H., and T.B.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved as exempt by the institutional review board of the University of Idaho (21-223).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of the sensitive nature of students’ grades. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Tyler Bland (tbland@uidaho.edu).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the students at the experimental site for contributing to this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MS1/MS2 |

First-year medical student / Second-year medical student |

| NPC |

Non-playable character |

| MCQ |

Multiple-choice question |

| SIS-M |

Situational Interest Survey for Multimedia |

| Trig |

Triggered situational interest |

| MF |

Maintained-feeling situational interest |

| MV |

Maintained-value situational interest |

| MT |

Maintained total situational interest |

| DiD |

Differences-in-Differences |

| LLM |

Large Language Model |

| genAI |

Generative Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

Table A1.

SIS items. X was replaced with “original” and “BlandPharm/Medimon” for the original and Medimon algorithm survey, respectively.

Table A1.

SIS items. X was replaced with “original” and “BlandPharm/Medimon” for the original and Medimon algorithm survey, respectively.

| SIS Type |

Survey Item |

| SI-triggered |

The X algorithm was interesting. |

| The X algorithm grabbed my attention. |

| The X algorithm was often entertaining. |

| The X algorithm was so exciting, it was easy to pay attention. |

| SI-maintained-feeling |

What I learned from the X algorithm is fascinating to me. |

| I am excited about what I learned from the X algorithm. |

| I like what I learned from the X algorithm. |

| I found the information from the X algorithm interesting. |

| SI-maintained-value |

What I studied in the X algorithm is useful for me to know. |

| The things I studied in the X algorithm are important to me. |

| What I learned from the X algorithm can be applied to my major/career. |

| I learned valuable things from the X algorithm. |

Appendix B

Table 1.

Unit exam analysis.

Table 1.

Unit exam analysis.

| Site |

Focal items % (SD) |

Baseline items % (SD) |

Within-site gap

(F – B, %) |

DiD

(ES – Ctrl, %) |

t |

p

(two-tailed) |

| ES |

77.4 (14.6) |

80.2 (13.7) |

-2.8 |

|

|

|

| 1 |

82.2 (16.9) |

86.7 (13.0) |

-4.5 |

1.7 |

0.51 |

0.612 |

| 2 |

74.8 (19.9) |

86.2 (13.2) |

-11.4 |

8.6 |

1.65 |

0.119 |

| 3 |

81.9 (12.3) |

82.8 (10.4) |

-0.9 |

-1.9 |

-0.54 |

0.598 |

| 4 |

79.2 (14.5) |

83.7 (12.0) |

-4.5 |

1.7 |

0.60 |

0.558 |

| 5 |

76.7 (21.5) |

82.0 (15.9) |

-5.3 |

2.5 |

0.43 |

0.670 |

| 1-5 (pooled) |

79.8 (14.5) |

83.8 (10.5) |

-4.0 |

1.2 |

0.38 |

0.707 |

Table 2.

Final exam analysis.

Table 2.

Final exam analysis.

| Site |

Focal items % (SD) |

Baseline items % (SD) |

Within-site gap

(F – B, %) |

DiD

(ES – Ctrl, %) |

t |

p

(two-tailed) |

| ES |

72.3 (22.9) |

80.5 (20.1) |

-8.2 |

|

|

|

| 1 |

56.8 (24.7) |

75.0 (21.1) |

-18.2 |

10.0 |

1.26 |

0.289 |

| 2 |

67.0 (22.4) |

76.0 (16.7) |

-9.0 |

0.8 |

0.15 |

0.889 |

| 3 |

53.8 (26.4) |

75.0 (16.7) |

-21.2 |

13.0 |

1.26 |

0.293 |

| 4 |

56.5 (26.4) |

76.1 (17.4) |

-19.6 |

11.4 |

1.32 |

0.274 |

| 5 |

48.8 (24.1) |

74.9 (18.4) |

-26.2 |

17.9 |

1.44 |

0.240 |

| 1-5 (pooled) |

56.2 (24.2) |

75.4 (16.6) |

-19.2 |

11.0 |

1.32 |

0.272 |

References

- Alomar, Z.; Guo, M.; Bland, T. (2025). AI-Generated Mnemonic Images Improve Long-Term Retention of Coronary Artery Occlusions in STEMI: A Comparative Study. Technologies 2025, Vol. 13, Page 217, 13(6), 217. [CrossRef]

- Avila-Pesántez, D., Rivera, L. A., & Alban, M. S. (2017). Approaches for serious game design: A systematic literature review. Computers in Education Journal, 8(3).

- Bernacki, M. L., & Walkington, C. (2018). The role of situational interest in personalized learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(6), 864–881. [CrossRef]

- Besche, H. C., King, R. W., Shafer, K. M., Fleet, S. E., Charles, J. F., Kaplan, T. B., Greenzang, K. A., Hoenig, M. P., Schwartzstein, R. M., Cockrill, B. A., & Fischer, K. (2025). Effective and Engaging Active Learning in the Medical School Classroom: Lessons from Case-Based Collaborative Learning. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 12, 23821205251317148. [CrossRef]

- Bland, T., & Guo, M. (2024). Visual Mnemonics and Gamification: A New Approach to Teaching Muscle Physiology. Journal of Technology-Integrated Lessons and Teaching, 3(1), 73–82. [CrossRef]

- Clark, J. M., & Paivio, A. (1991). Dual coding theory and education. Educational Psychology Review, 3(3), 149–210. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87–114. [CrossRef]

- Evans, P., Vansteenkiste, M., Parker, P., Kingsford-Smith, A., & Zhou, S. (2024). Cognitive Load Theory and Its Relationships with Motivation: a Self-Determination Theory Perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 36(1), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Fung, K., & Oyibo, K. (2024). Examining the Effectiveness of Mnemonics Serious Games in Enhancing Memory and Learning: A Scoping Review. Applied Sciences, 14(23), 11379. [CrossRef]

- Ghanbari, S., Haghani, F., Barekatain, M., & Jamali, A. (2020). A systematized review of cognitive load theory in health sciences education and a perspective from cognitive neuroscience. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9(1), 176. [CrossRef]

- Grover, S., & Pea, R. (2013). Computational Thinking in K–12. Educational Researcher, 42(1), 38–43. [CrossRef]

- Hundrup, M., Holte, J., Bordeaux, C., Ferguson, E., Coad, J., Soule, T., & Bland, T. (2025). Space Medicine Meets Serious Games: Boosting Engagement with the Medimon Creature Collector. Multimodal Technologies and Interaction 2025, Vol. 9, Page 80, 9(8), 80. [CrossRef]

- Leehey, D. J., & Daugirdas, J. T. (2016). Teaching renal physiology in the 21st century: focus on acid–base physiology. Clinical Kidney Journal, 9(2), 330–333. [CrossRef]

- Lyra, K. T., Isotani, S., Reis, R. C. D., Marques, L. B., Pedro, L. Z., Jaques, P. A., & Bitencourt, I. I. (2016). Infographics or Graphics+Text: Which material is best for robust learning? Proceedings - IEEE 16th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies, ICALT 2016, 366–370. [CrossRef]

-

Medimon - Fun and Engaging Medical Science Learning Game. (n.d.). Retrieved January 28, 2025, from https://medimon.games/.

- Morikawa, M. J., & Ganesh, P. R. (2025). Acid-Base Interpretation: A Practical Approach. American Family Physician, 111(2), 148–155. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2025/0200/acid-base-interpretation.html.

- Singleton, V., Bordeaux, C., Ferguson, E., & Bland, T. (2025). An Educational Trading Card Game for a Medical Immunology Course. Education Sciences, 15(6), 768. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B., & Shimeld, S. (2014). Using pictorial mnemonics in the learning of tax: A cognitive load perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 565–579. [CrossRef]

- Sweller, J. (1994). Cognitive load theory, learning difficulty, and instructional design. Learning and Instruction, 4(4), 295–312. [CrossRef]

- Tackett, S., Steinert, Y., Whitehead, C. R., Reed, D. A., & Wright, S. M. (2022). Blind spots in medical education: how can we envision new possibilities? Perspectives on Medical Education, 11(6), 365. [CrossRef]

-

Welcome - Opal [Experiment]. (n.d.). Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://opal.withgoogle.com/landing/.

- Worthley, B., Guo, M., Sheneman, L., & Bland, T. (2025). Antiparasitic Pharmacology Goes to the Movies: Leveraging Generative AI to Create Educational Short Films. AI 2025, Vol. 6, Page 60, 6(3), 60. [CrossRef]

- Young, J. Q., Van Merrienboer, J., Durning, S., & Ten Cate, O. (2014). Cognitive Load Theory: implications for medical education: AMEE Guide No. 86. Medical Teacher, 36(5), 371–384. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Jingru, Z., & Lu, Y. (2025). Enhancing Design Historical Education Through AI Virtual Characters Role-Playing Narratives in Serious Games. International Journal of Gaming and Computer-Mediated Simulations (IJGCMS), 17(1), 1–20. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Image to support acid/base analysis and diagnosis. A, Image presenting the original algorithm for analyzing acid/base disorders. B, Medimon algorithm with mnemonic-based illustrations and Medimon for analyzing acid/base disorders.

Figure 1.

Image to support acid/base analysis and diagnosis. A, Image presenting the original algorithm for analyzing acid/base disorders. B, Medimon algorithm with mnemonic-based illustrations and Medimon for analyzing acid/base disorders.

Figure 2.

Medimon characters utilized in the Medimon algorithm. (a), The Kidney Medimon character with labeled mnemonics. The Medimon algorithm utilized two different versions of this character with additional mnemonics specific for acid/base analysis. (b), The Lung Medimon character with labeled mnemonics. The “lemon snail” and “running upright bass” visual mnemonics were mostly utilized in the Medimon algorithm.

Figure 2.

Medimon characters utilized in the Medimon algorithm. (a), The Kidney Medimon character with labeled mnemonics. The Medimon algorithm utilized two different versions of this character with additional mnemonics specific for acid/base analysis. (b), The Lung Medimon character with labeled mnemonics. The “lemon snail” and “running upright bass” visual mnemonics were mostly utilized in the Medimon algorithm.

Figure 3.

Sweet 16 anime image generation. (a) ChatGPT 4o with native image generation was provided artist drawn Medimon character images for reference (a) and the prompt: “Please generate an image of a character wearing a cute dress. She is also wearing a sweet “16” crown and a “Sweet 16” sash. Please match the art style of the attached images.” (b) ChatGPT 4o with native image generation output from (a). This was followed by the prompt: “Please remove the background.” to produce the final image for the Medimon algorithm.

Figure 3.

Sweet 16 anime image generation. (a) ChatGPT 4o with native image generation was provided artist drawn Medimon character images for reference (a) and the prompt: “Please generate an image of a character wearing a cute dress. She is also wearing a sweet “16” crown and a “Sweet 16” sash. Please match the art style of the attached images.” (b) ChatGPT 4o with native image generation output from (a). This was followed by the prompt: “Please remove the background.” to produce the final image for the Medimon algorithm.

Figure 4.

Mnemonic breakdown of the Medimon algorithm. (1) Low Five represents that if the pH drops lower than 0.05 (<7.35) this is classified as an acidemia. (2) Lemon represents acid (think citric acid). (3) Kidney Medimon holding a lemon and “double-peace” sign representing that if the HCO3 is lower than 22 (double-peace sign) then this is a metabolic (Kidney) acidosis (lemon). (4) Black “40”th birthday balloons floating upwards by the Lung Medimon represents that if the pCO2 is >40 (40th birthday balloons) then this is a respiratory (Lung) acidosis. (5) Lung Medimon holding a lemon snail represents that a slow respiratory rate (snail) can cause a respiratory (Lung) acidosis (lemon). (6) Girl at Sweet 16 party represents that if the anion gap (AG) is >16, this is a high AG acidosis. (7, 8) Alternate Kidney Medimon representing metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis. (9) High Five represents that if the pH raises higher than 0.05 (>7.45) this is classified as an alkalemia. (10) Upright bass represents base. (11) Kidney Medimon holding up two fingers and a magic 8 ball representing that if the HCO3 is >28 (two fingers + magic 8 ball) then this is a metabolic (Kidney) alkalosis. (12) Week calendar represents the respiratory compensation calculation of 1 HCO3: 0.7 pCO2 (7 days in a week). (13) Black “40”th birthday balloons sinking downwards by the Lung Medimon represents that if the pCO2 is <40 (40th birthday balloons) then this is a respiratory (Lung) alkalosis. (14) Lung Medimon holding a running upright bass represents that a fast respiratory rate (running) can cause a respiratory alkalosis (upright bass). (15) The band One Direction logo having a kidney superimposed over the “D” represents that if the pH and the HCO3 are changing in the same direction (One Direction) then this is a metabolic (kidney) problem.

Figure 4.

Mnemonic breakdown of the Medimon algorithm. (1) Low Five represents that if the pH drops lower than 0.05 (<7.35) this is classified as an acidemia. (2) Lemon represents acid (think citric acid). (3) Kidney Medimon holding a lemon and “double-peace” sign representing that if the HCO3 is lower than 22 (double-peace sign) then this is a metabolic (Kidney) acidosis (lemon). (4) Black “40”th birthday balloons floating upwards by the Lung Medimon represents that if the pCO2 is >40 (40th birthday balloons) then this is a respiratory (Lung) acidosis. (5) Lung Medimon holding a lemon snail represents that a slow respiratory rate (snail) can cause a respiratory (Lung) acidosis (lemon). (6) Girl at Sweet 16 party represents that if the anion gap (AG) is >16, this is a high AG acidosis. (7, 8) Alternate Kidney Medimon representing metabolic acidosis and metabolic alkalosis. (9) High Five represents that if the pH raises higher than 0.05 (>7.45) this is classified as an alkalemia. (10) Upright bass represents base. (11) Kidney Medimon holding up two fingers and a magic 8 ball representing that if the HCO3 is >28 (two fingers + magic 8 ball) then this is a metabolic (Kidney) alkalosis. (12) Week calendar represents the respiratory compensation calculation of 1 HCO3: 0.7 pCO2 (7 days in a week). (13) Black “40”th birthday balloons sinking downwards by the Lung Medimon represents that if the pCO2 is <40 (40th birthday balloons) then this is a respiratory (Lung) alkalosis. (14) Lung Medimon holding a running upright bass represents that a fast respiratory rate (running) can cause a respiratory alkalosis (upright bass). (15) The band One Direction logo having a kidney superimposed over the “D” represents that if the pH and the HCO3 are changing in the same direction (One Direction) then this is a metabolic (kidney) problem.

Figure 5.

Google Opal application layout. The agentic genAI workflow for the thematic analysis of survey open-ended questions utilized qualitative research (QR) agents, principle investigator (PI) agents, and an academic writer agent. All QR and PI agents had access to the survey response and rough draft of the manuscript. The academic writer agent had access to the rough draft of the manuscript.

Figure 5.

Google Opal application layout. The agentic genAI workflow for the thematic analysis of survey open-ended questions utilized qualitative research (QR) agents, principle investigator (PI) agents, and an academic writer agent. All QR and PI agents had access to the survey response and rough draft of the manuscript. The academic writer agent had access to the rough draft of the manuscript.

Figure 6.

Student performance analysis. (a) Average scores for exam questions related to the acid/base analysis lecture (focal items) on the unit exam and the course final exam for each site. Sites 1-5 only received the original algorithm (Control sites) while site 6 (Experimental site) also received the Medimon algorithm. (b) Difference-in-Differences (DiD) analysis between the average score for the focal items on both exams and the remainder of the exam questions (baseline items) to correct for exam difficulty and baseline student knowledge. The statistical analysis represents a significant difference between the differences in focal: baseline scores between the Experimental and combined average of the Control sites. Exp: Experimental, Ctrl: Control.

Figure 6.

Student performance analysis. (a) Average scores for exam questions related to the acid/base analysis lecture (focal items) on the unit exam and the course final exam for each site. Sites 1-5 only received the original algorithm (Control sites) while site 6 (Experimental site) also received the Medimon algorithm. (b) Difference-in-Differences (DiD) analysis between the average score for the focal items on both exams and the remainder of the exam questions (baseline items) to correct for exam difficulty and baseline student knowledge. The statistical analysis represents a significant difference between the differences in focal: baseline scores between the Experimental and combined average of the Control sites. Exp: Experimental, Ctrl: Control.

Table 1.

Effect size of achievement differences between the experimental site vs all control sites. ES: Experimental site, Ctrl: Control sites.

Table 1.

Effect size of achievement differences between the experimental site vs all control sites. ES: Experimental site, Ctrl: Control sites.

| Exam |

DiD (ES - Ctrlpooled) |

Hedges g

|

95% CI |

Effect Size |

| Unit Exam |

1.2 |

0.12 |

-0.62 to 0.86 |

Small |

| Final Exam |

11.0 |

0.85 |

-0.17 to 1.87 |

Medium-to-large |

Table 2.

Paired sample t-tests for SIS-M categories. Trig: triggered situational interest, MT: maintained interest, MF: maintained feeling, MV: maintained value, MA: Medimon algorithm, OR: Original algorithm, SD: standard deviation, SEM: standard error of the mean, df: degrees of freedom.

Table 2.

Paired sample t-tests for SIS-M categories. Trig: triggered situational interest, MT: maintained interest, MF: maintained feeling, MV: maintained value, MA: Medimon algorithm, OR: Original algorithm, SD: standard deviation, SEM: standard error of the mean, df: degrees of freedom.

| |

Paired Differences |

t |

df |

Significance |

| |

Mean |

SD |

SEM |

95% Confidence Interval of the Difference |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

|

One-Sided p |

Two-Sided p |

| MA-OR (Trig) |

2.62 |

1.02 |

0.16 |

2.29 |

2.95 |

16.04 |

38 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

| MA-OR (MF) |

1.46 |

1.13 |

0.18 |

1.10 |

1.83 |

8.08 |

38 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

| MA-OR (MV) |

0.92 |

1.03 |

0.17 |

0.59 |

1.26 |

5.58 |

38 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

| MA-OR (MT) |

1.19 |

0.99 |

0.16 |

0.87 |

1.51 |

7.53 |

38 |

<.001 |

<.001 |

Table 3.

Thematic analysis results.

Table 3.

Thematic analysis results.

| Theme |

Definition |

Representative Codes |

|

1. Enhanced Clarity and Cognitive Accessibility |

The perception that the Medimon algorithm’s structure, layout, and simplicity made the complex topic easier to understand, follow, and process, thereby reducing cognitive load. |

Ease of following; Improved organization; Streamlined design; Simplicity; Logical structure; Reduced cognitive load; Less overwhelming. |

|

2. Improved Memorability and Recall via Visual Mnemonics |

The belief that visual elements (characters, images, colors) created memorable associations with medical concepts, facilitating more efficient encoding, retention, and retrieval of information, particularly for application in exams. |

Ease of memorization; Visual mnemonics; Illustrations aid recall; Mental visualization; Improved retention; Pictures facilitate mental recreation. |

|

3. Increased Engagement and Affective Appeal |

The experience of the algorithm as visually attractive, interesting, and captivating, which captured attention, increased motivation, and fostered a positive emotional and professional connection to the material. |

Visually appealing; Engaging/Captivating; Aesthetic appeal; Visually interesting; Perceived design effort; Brand trust; Perceived value. |

|

4. Barriers to Use and Interpretation |

The minority perspective indicating that the mnemonic-based approach was not universally effective, with some students not using the materials or finding the symbols difficult to decipher without additional aids. |

Non-use of materials; Limited engagement; Difficulty deciphering mnemonics; Required cross-referencing. |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).