Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies Detection

2.2. RNA Extraction and Detection of Dengue Serotypes Using qRT-PCR

2.3. Protein Integrity

2.4. Label-Free Based Quantitative Proteomic Analysis of Serum Proteome

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

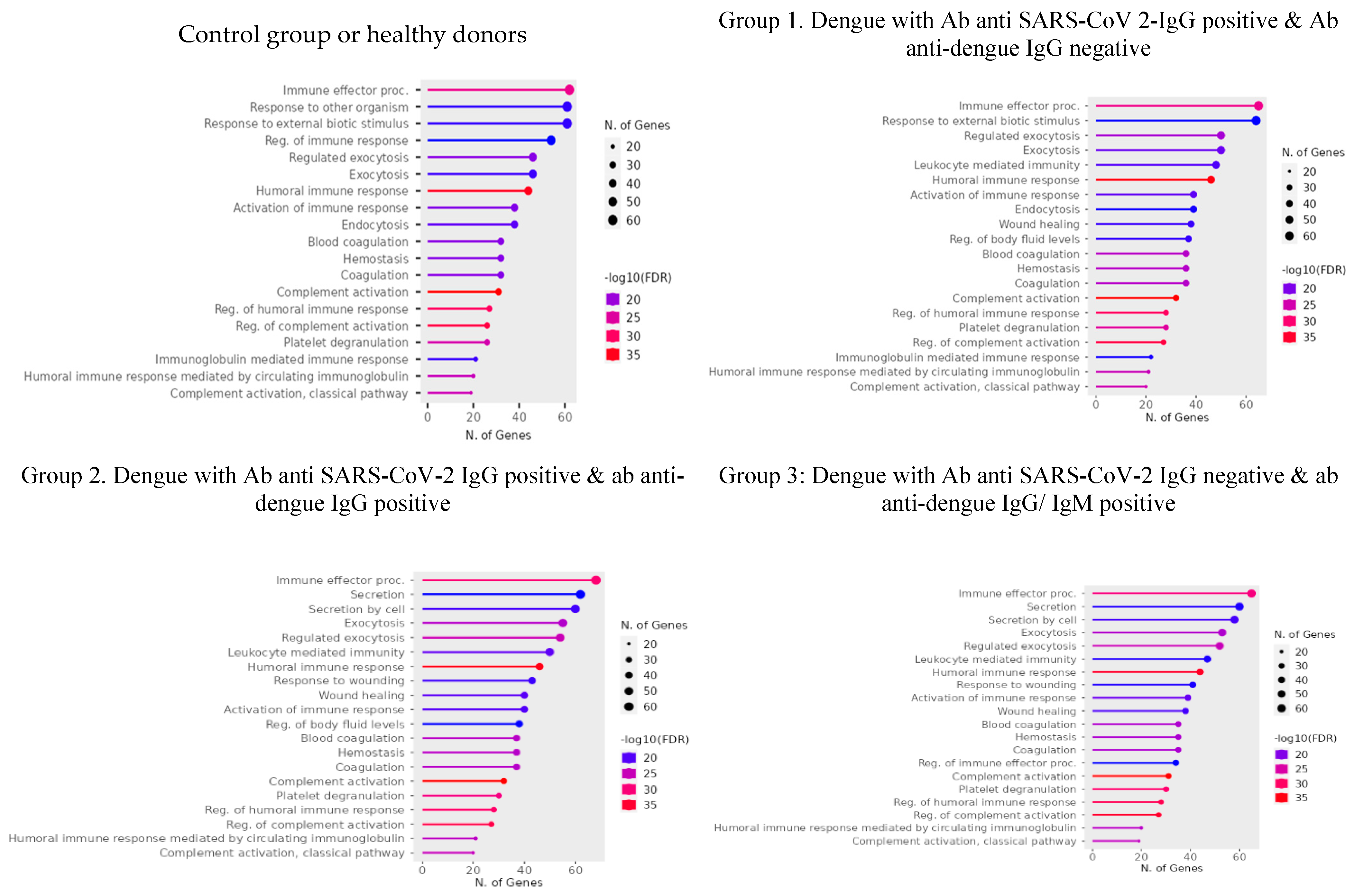

3.1. Serum Proteome Analysis

3.1.1. Differentially Expressed Proteins (DEPs)

3.2. Protein Abundance Index

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dengue and Severe Dengue. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue (accessed on 9 January 2025).

- Katzelnick, L.C.; Gresh, L.; Halloran, M.E.; Mercado, J.C.; Kuan, G.; Gordon, A.; Balmaseda, A.; Harris, E. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Severe Dengue Disease in Humans. Science 2017, 358, 929–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, C.Y.Y.; Low, J.Z.H.; Gan, E.S.; Ong, E.Z.; Zhang, S.L.-X.; Tan, H.C.; Chai, X.; Ghosh, S.; Ooi, E.E.; Chan, K.R. Antibody-Dependent Dengue Virus Entry Modulates Cell Intrinsic Responses for Enhanced Infection. mSphere 2019, 4, e00528–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigo, W.W.S.I.; Jin, X.; Blackley, S.D.; Rose, R.C.; Schlesinger, J.J. Differential Enhancement of Dengue Virus Immune Complex Infectivity Mediated by Signaling-Competent and Signaling-Incompetent Human FcγRIA (CD64) or FcγRIIA (CD32). J. Virol. 2006, 80, 10128–10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayan, R.; Tripathi, S. Intrinsic ADE: The Dark Side of Antibody Dependent Enhancement During Dengue Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 580096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ubol, S.; Phuklia, W.; Kalayanarooj, S.; Modhiran, N. Mechanisms of Immune Evasion Induced by a Complex of Dengue Virus and Pre-existing Enhancing Antibodies. J. Infect. Dis. 2010, 201, 923–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Cheng, Y.; Ling, R.; Dai, Y.; Huang, B.; Huang, W.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, Y. Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Coronavirus. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 100, 483–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawant, J.; Patil, A.; Kurle, S. A Review: Understanding Molecular Mechanisms of Antibody-Dependent Enhancement in Viral Infections. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonheur, A.N.; Thomas, S.; Soshnick, S.H.; McGibbon, E.; Dupuis, A.P.; Hull, R.; Slavinski, S.; Del Rosso, P.E.; Weiss, D.; Hunt, D.T.; et al. A Fatal Case Report of Antibody-Dependent Enhancement of Dengue Virus Type 1 Following Remote Zika Virus Infection. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jain, D.; Salunke, D.M. Antibody Specificity and Promiscuity. Biochem. J. 2019, 476, 433–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, G.; Lee, C.K.; Lam, L.T.M.; Yan, B.; Chua, Y.X.; Lim, A.Y.N.; Phang, K.F.; Kew, G.S.; Teng, H.; Ngai, C.H.; et al. Covert COVID-19 and False-Positive Dengue Serology in Singapore. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembuan, G.J. Dengue Serology in Indonesian COVID-19 Patients: Coinfection or Serological Overlap? IDCases 2020, 22, e00927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spinicci, M.; Bartoloni, A.; Mantella, A.; Zammarchi, L.; Rossolini, G.M.; Antonelli, A. Low Risk of Serological Cross-Reactivity between Dengue and COVID-19. Mem. Inst. Oswaldo Cruz 2020, 115, e200225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, H.; Mallick, A.; Roy, S.; Sukla, S.; Biswas, S. Computational Modelling Supports That Dengue Virus Envelope Antibodies Can Bind to SARS-CoV-2 Receptor Binding Sites: Is Pre-Exposure to Dengue Virus Protective against COVID-19 Severity? Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 459–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lustig, Y.; Keler, S.; Kolodny, R.; Ben-Tal, N.; Atias-Varon, D.; Shlush, E.; Gerlic, M.; Munitz, A.; Doolman, R.; Asraf, K.; et al. Potential Antigenic Cross-Reactivity Between Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and Dengue Viruses. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2021, 73, e2444–e2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.-L.; Chao, C.-H.; Lai, Y.-C.; Hsieh, K.-H.; Wang, J.-R.; Wan, S.-W.; Huang, H.-J.; Chuang, Y.-C.; Chuang, W.-J.; Yeh, T.-M. Antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 S1-RBD Cross-React with Dengue Virus and Hinder Dengue Pathogenesis. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 941923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beig, I.; Talwar, D.; Kumar, S.; Hulkoti, V. Post Covid Fatal Antibody Dependent Enhancement of Dengue Infection in a Young Male: Double Trouble. 2021.

- Kumar, Y.; Liang, C.; Bo, Z.; Rajapakse, J.C.; Ooi, E.E.; Tannenbaum, S.R. Serum Proteome and Cytokine Analysis in a Longitudinal Cohort of Adults with Primary Dengue Infection Reveals Predictive Markers of DHF. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2012, 6, e1887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Ao, X.; Lin, S.; Guan, S.; Zheng, L.; Han, X.; Ye, H. Quantitative Comparative Proteomics Reveal Biomarkers for Dengue Disease Severity. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garishah, F.M.; Boahen, C.K.; Vadaq, N.; Pramudo, S.G.; Tunjungputri, R.N.; Riswari, S.F.; Van Rij, R.P.; Alisjahbana, B.; Gasem, M.H.; Van Der Ven, A.J.A.M.; et al. Longitudinal Proteomic Profiling of the Inflammatory Response in Dengue Patients. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2023, 17, e0011041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Yamakuchi, M.; Ture, S.; De La Luz Garcia-Hernandez, M.; Ko, K.A.; Modjeski, K.L.; LoMonaco, M.B.; Johnson, A.D.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Takai, Y.; et al. Syntaxin-Binding Protein STXBP5 Inhibits Endothelial Exocytosis and Promotes Platelet Secretion. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 4503–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.; Huang, Y.; Joshi, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, F.; Zhang, G.; Smyth, S.S.; Li, Z.; Takai, Y.; Whiteheart, S.W. Platelet Secretion and Hemostasis Require Syntaxin-Binding Protein STXBP5. J. Clin. Invest. 2014, 124, 4517–4528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toledo, K.A.; Fermino, M.L.; Andrade, C.D.C.; Riul, T.B.; Alves, R.T.; Muller, V.D.M.; Russo, R.R.; Stowell, S.R.; Cummings, R.D.; Aquino, V.H.; et al. Galectin-1 Exerts Inhibitory Effects during DENV-1 Infection. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e112474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhamarapravati, N. Hemostatic Defects in Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1989, 11, S826–S829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Funahara, Y. ; Sumarmo; Wirawan, R. Features of DIC in Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever. In Current Studies in Hematology and Blood Transfusion; Abe, T., Yamanaka, M., Eds.; S. Karger AG, 1983; Vol. 49, pp. 201–211 ISBN 978-3-8055-3726-1.

- Yang, E.-J.; Seo, J.-W.; Choi, I.-H. Ribosomal Protein L19 and L22 Modulate TLR3 Signaling. Immune Netw. 2011, 11, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, E.; Gracias, S.; Beauclair, G.; Tangy, F.; Jouvenet, N. Uncovering Flavivirus Host Dependency Factors through a Genome-Wide Gain-of-Function Screen. Viruses 2019, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qing, M.; Yang, F.; Zhang, B.; Zou, G.; Robida, J.M.; Yuan, Z.; Tang, H.; Shi, P.-Y. Cyclosporine Inhibits Flavivirus Replication through Blocking the Interaction between Host Cyclophilins and Viral NS5 Protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3226–3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isenberg, J.S.; Romeo, M.J.; Yu, C.; Yu, C.K.; Nghiem, K.; Monsale, J.; Rick, M.E.; Wink, D.A.; Frazier, W.A.; Roberts, D.D. Thrombospondin-1 Stimulates Platelet Aggregation by Blocking the Antithrombotic Activity of Nitric Oxide/cGMP Signaling. Blood 2008, 111, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimanda, J.E.; Ganderton, T.; Maekawa, A.; Yap, C.L.; Lawler, J.; Kershaw, G.; Chesterman, C.N.; Hogg, P.J. Role of Thrombospondin-1 in Control of von Willebrand Factor Multimer Size in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 21439–21448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigglekow, N.D.; Pangon, L.; Brummer, T.; Molloy, M.; Hawkins, N.J.; Ward, R.L.; Musgrove, E.A.; Kohonen-Corish, M.R.J. Mutated in Colorectal Cancer Protein Modulates the NFκB Pathway. ANTICANCER Res. 2012.

- Edwards, S.K.; Baron, J.; Moore, C.R.; Liu, Y.; Perlman, D.H.; Hart, R.P.; Xie, P. Mutated in Colorectal Cancer (MCC) Is a Novel Oncogene in B Lymphocytes. J. Hematol. Oncol.J Hematol Oncol 2014, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqueda-Alfaro, R.A.; Marcial-Juárez, E.; Calderón-Amador, J.; García-Cordero, J.; Orozco-Uribe, M.; Hernández-Cázares, F.; Medina-Pérez, U.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Flores-Langarica, A.; Cedillo-Barrón, L.; et al. Robust Plasma Cell Response to Skin-Inoculated Dengue Virus in Mice. J. Immunol. Res. 2021, 2021, 5511841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohrbach, M.S.; Wheatley, C.L.; Slifman, N.R.; Gleich, G.J. Activation of Platelets by Eosinophil Granule Proteins. J. Exp. Med. 1990, 172, 1271–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunder, M.; Lakshmaiah, V.; Moideen Kutty, A.V. Plasma Neutrophil Elastase, A1-Antitrypsin, A2-Macroglobulin and Neutrophil Elastase–A1-Antitrypsin Complex Levels in Patients with Dengue Fever. Indian J. Clin. Biochem. 2018, 33, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.T.; Yurtseven, A.; Dadmand, S.; Ozcan, G.; Akarlar, B.A.; Kucuk, N.E.O.; Senturk, A.; Ergonul, O.; Can, F.; Tuncbag, N.; et al. Plasma Proteomics Identify Potential Severity Biomarkers from COVID-19 Associated Network. PROTEOMICS – Clin. Appl. 2023, 17, 2200070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Y.; Nakai, Y.; Shin, J.; Hara, M.; Takeda, Y.; Kubo, S.; Jeremiah, S.S.; Ino, Y.; Akiyama, T.; Moriyama, K.; et al. Identification of Serum Prognostic Biomarkers of Severe COVID-19 Using a Quantitative Proteomic Approach. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Flora, D.C.; Dionizio, A.; Pereira, H.A.B.S.; Garbieri, T.F.; Grizzo, L.T.; Dionisio, T.J.; Leite, A. de L. ; Silva-Costa, L.C.; Buzalaf, N.R.; Reis, F.N.; et al. Analysis of Plasma Proteins Involved in Inflammation, Immune Response/Complement System, and Blood Coagulation upon Admission of COVID-19 Patients to Hospital May Help to Predict the Prognosis of the Disease. Cells 2023, 12, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padwad, Y.S.; Mishra, K.P.; Jain, M.; Chanda, S.; Karan, D.; Ganju, L. RNA Interference Mediated Silencing of Hsp60 Gene in Human Monocytic Myeloma Cell Line U937 Revealed Decreased Dengue Virus Multiplication. Immunobiology 2009, 214, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollenberg, R.; Tepasse, P.-R.; Fobker, M.; Hüsing-Kabar, A. Significantly Reduced Retinol Binding Protein 4 (RBP4) Levels in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients. Nutrients 2022, 14, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramer, L.M.; Hontz, R.D.; Eisfeld, A.J.; Sims, A.C.; Kim, Y.-M.; Stratton, K.G.; Nicora, C.D.; Gritsenko, M.A.; Schepmoes, A.A.; Akasaka, O.; et al. Multi-Omics of NET Formation and Correlations with CNDP1, PSPB, and L-Cystine Levels in Severe and Mild COVID-19 Infections. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soe, H.J.; Yong, Y.K.; Al-Obaidi, M.M.J.; Raju, C.S.; Gudimella, R.; Manikam, R.; Sekaran, S.D. Identifying Protein Biomarkers in Predicting Disease Severity of Dengue Virus Infection Using Immune-Related Protein Microarray. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018, 97, e9713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upasani, V.; Ter Ellen, B.M.; Sann, S.; Lay, S.; Heng, S.; Laurent, D.; Ly, S.; Duong, V.; Dussart, P.; Smit, J.M.; et al. Characterization of Soluble TLR2 and CD14 Levels during Acute Dengue Virus Infection. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, G.-Q.; Zeng, H.-X.; Li, Z.-L.; Chen, C.; Zhong, J.-Y.; Xiao, M.-S.; Zeng, Q.; Jiang, W.-H.; Wu, P.-Q.; Zeng, J.-M.; et al. Differential Proteomic Analysis of Children Infected with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2021, 54, e9850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.-H.; Liu, C.-C.; Wang, S.-T.; Lei, H.-Y.; Liu, H.-S.; Lin, Y.-S.; Wu, H.-L.; Yeh, T.-M. Activation of Coagulation and Fibrinolysis during Dengue Virus Infection. J. Med. Virol. 2001, 63, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R.; Mudaliar, P.; Jaleel, A.; Srikanth, J.; Sreekumar, E. High Throughput Proteomic Analysis and a Comparative Review Identify the Nuclear Chaperone, Nucleophosmin among the Common Set of Proteins Modulated in Chikungunya Virus Infection. J. Proteomics 2015, 120, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.-L.; Lin, C.-L.; Chen, Y.-C.; Lu, I.-A.; Su, B.-H.; Chen, Y.-H.; Liu, K.-T.; Wu, C.-L.; Shiau, A.-L. Prothymosin α Accelerates Dengue Virus-Induced Thrombocytopenia. iScience 2024, 27, 108422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riswari, S.F.; Tunjungputri, R.N.; Kullaya, V.; Garishah, F.M.; Utari, G.S.R.; Farhanah, N.; Overheul, G.J.; Alisjahbana, B.; Gasem, M.H.; Urbanus, R.T.; et al. Desialylation of Platelets Induced by Von Willebrand Factor Is a Novel Mechanism of Platelet Clearance in Dengue. PLOS Pathog. 2019, 15, e1007500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trugilho, M.R. de O. ; Hottz, E.D.; Brunoro, G.V.F.; Teixeira-Ferreira, A.; Carvalho, P.C.; Salazar, G.A.; Zimmerman, G.A.; Bozza, F.A.; Bozza, P.T.; Perales, J. Platelet Proteome Reveals Novel Pathways of Platelet Activation and Platelet-Mediated Immunoregulation in Dengue. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouysségur, J.; Marchiq, I.; Parks, S.K.; Durivault, J.; Ždralević, M.; Vucetic, M. ‘Warburg Effect’ Controls Tumor Growth, Bacterial, Viral Infections and Immunity – Genetic Deconstruction and Therapeutic Perspectives. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2022, 86, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panes, O.; Matus, V.; Sáez, C.G.; Quiroga, T.; Pereira, J.; Mezzano, D. Human Platelets Synthesize and Express Functional Tissue Factor. Blood 2007, 109, 5242–5250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Larragoiti, N.; Kim, Y.C.; López-Camacho, C.; Cano-Méndez, A.; López-Castaneda, S.; Hernández-Hernández, D.; Vargas-Ruiz, Á.G.; Vázquez-Garcidueñas, M.S.; Reyes-Sandoval, A.; Viveros-Sandoval, M.E. Platelet Activation and Aggregation Response to Dengue Virus Non-structural Protein 1 and Domains. J. Thromb. Haemost. JTH 2021, 19, 2572–2582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, A.; Nandi, D.; Batra, H.; Singhal, R.; Annarapu, G.K.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Seth, T.; Dar, L.; Medigeshi, G.R.; Vrati, S.; et al. Platelet Activation Determines the Severity of Thrombocytopenia in Dengue Infection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 41697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, A.; Bisht, P.; Bhattacharya, S.; Guchhait, P. Role of Platelet Cytokines in Dengue Virus Infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 561366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, S.; D’Abrosca, G.; Antolak, A.; Pedone, P.V.; Isernia, C.; Malgieri, G. Host and Viral Zinc-Finger Proteins in COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dengue - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Available online: https://www.paho.org/es/arbo-portal/dengue (accessed on 9 January 2025).

| Group | ID | Ab anti SARS-CoV-2 IgG | Ab anti dengue IgG | Ab anti dengue IgM | Dengue NS1 | Dengue RT PCR cT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Group | 1 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Neg | - |

| 2 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | - | |

| 3 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Neg | - | |

| Group 1. SARS-CoV 2-IgG & Dengue NS1 | 5162 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | 23.2 |

| 4810 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | 19.3 | |

| 4658 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | 27 | |

| 4972 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | 30.5 | |

| 5088 | Pos | Neg | Neg | Pos | 32.3 | |

| Group 2. SARS-CoV 2-IgG, Dengue NS1 & IgG | 5063 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | 24.8 |

| 4947 | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | 30.7 | |

| 4548 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | 25 | |

| 4375 | Pos | Pos | Pos | Pos | 26.2 | |

| 4452 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | 26.6 | |

| 4556 | Pos | Pos | Neg | Pos | 23 | |

| Group 3. Dengue NS1 & IgG | 5098 | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | 32.9 |

| 5134 | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | 22.1 | |

| 4376 | Neg | Pos | Neg | Pos | 20.2 | |

| 5062 | Neg | Pos | Pos | Pos | 24.8 |

| Protein | Uniprot ID | Gen | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control group of healthy donors | |||

| Syntaxin-binding protein 5 | Q5T5C0 | STXBP5 | STXBP5 inhibits endothelial exocytosis and promotes platelet secretion. In KO STXBP5 cells increase vWF & P-selectin secretion [21]. In platelets it is important for cargo release from dense granules, α granules, and lysosomes as well as for packaging of some cargo into granules [22]. |

| Galectin-1 | P09382 | LGALS1 | Gal-1 binds to DENV-1 and inhibits its adsorption and internalization processes in ECV-304 cells [23]. |

| Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase | P06744 | GPI | In the cytoplasm, catalyzes the conversion of glucose-6-phosphate to fructose-6-phosphate, the second step in glycolysis. |

| Group 1. Dengue with Ab anti SARS-CoV 2-IgG positive & Ab anti dengue IgG negative | |||

| Coagulation factor IX | P00740 | F9 | Participates in the intrinsic pathway of blood coagulation. Alteration of coagulation in dengue infection [24,25]. |

| Ribosomal protein L19 | P84098 | RPL19 | Component of the large ribosomal subunit. Ribosomal Protein L19 and L22 Modulate TLR3 Signaling [26]. RPL19 is required for efficient YFV and WNV protein production [27]. |

| Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B | P23284 | PPIB | Catalyze the isomerization of peptide bonds from trans to cis form at proline residues and facilitates protein folding. Knockdown of CYP isoforms reduces the replication of flavivirus VLPS [28]. |

| Group 2. Dengue with Ab anti SARS-CoV-2 IgG positive & ab anti dengue IgG positive | |||

| Thrombospondin-1 | P07996 | THBS1 | TSP1 is a major protein component of Alfa platelet-granules from which it is rapidly released during platelet activation. It stimulates platelet aggregation [29].TSP1 binds to A3 domain of vWF and may compete with ADAMTS13 for interaction with vWF [30]. |

| Colorectal mutant cancer protein | P23508 | MCC | Play role in cell proliferation. Colorectal Cancer Protein Modulates the NF-κB Pathway [31]. Knockdown of MCC induced apoptosis and inhibited proliferation in human MM cells [32]. |

| Coagulation factor XIII B chain | P05160 | F13B | The B chain of factor XIII is not catalytically active, but is thought to stabilize the A subunits. Alteration of coagulation in dengue infection [24,25]. |

| Antigen KI-67 | P46013 | MKI67 | Widely used as a marker to assess cell proliferation, as is detected in the nucleus of proliferating cells only. Expressed in plasmatic cells infected with dengue [33]. |

| Bone marrow proteoglycan | P13727 | PRG2 | Cytotoxin and helminthotoxin. It causes platelet activation [34]. |

| Group 3. Dengue with Ab anti SARS-CoV-2 IgG negative & ab anti dengue IgG/ IgM positive | |||

| Putative uncharacterized zinc finger protein 814 | B7Z6K7 | ZNF814 | Unknow function |

| Uniprot ID | Abundance ratio | Protein | Function | ||

| Group 1 | Group2 | Group 3 | |||

| P01023 | 0.67 | 2.49 | 0.28 | Alpha-2-macroglobulin | Antiprotease plays a role in hemostatic balance. Decreased levels during dengue infection as part of a normal immune response [35]. |

| P19823 | 0.55 | 2.10 | 0.63 | Inter-alpha-trypsin inhibitor heavy chain H2 | Decreased expression in patients with COVID 19 [36]. |

| P04217 | 2.70 | 2.66 | 2.44 | Alpha-1B-glycoprotein | Increased expression during dengue infection [18]. |

| P02750 | 2.28 | 2.18 | 2.51 | Leucine-rich-alpha-2glycoprotein* | Increased expression during dengue infection [18]. |

| P02748 | 2.04 | 4.75 | 0.91 | Complement component C9 | Elevated during dengue infection [18]. |

| P35542 | 2.17 | 0.90 | 1.01 | Serum amyloid A-4 protein | Unknow function in viral infection. |

| P02746 | 1.90 | 2.13 | 1.53 | Complement C1q subcomponent subunit B | First component of the serum complement system. |

| P35858 | 2.60 | 2.48 | 3.31 | Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein complex acid labile subunit | Involved in protein-protein interactions. Reduced levels in patients with severe COVID 19 [37]. |

| P04003 | 0.66 | 2.48 | 0.61 | C4b-binding protein alpha chain | Decreased in patients with severe COVID 19 [38]. |

| P03952 | 1.57 | 2.29 | 1.94 | Plasma kallikrein. | Participates in blood coagulation. |

| Q96PD5 | 1.56 | 1.41 | 2.24 | N-acetylmuramoyl-L-alanine amidase. | Decreased in patients with severe COVID 19 [38]. |

| P10643 | 2.39 | 4.36 | 3.43 | Complement component C7 | Constituent of the membrane attack complex (MAC). |

| P10809 | 1.19 | 3.09 | 0.14 | 60 kDa heat shock protein, mitochondrial | elevated levels of expression during dengue infection in U937 cells [39]. |

| Q96L50 | 7.51 | 4.20 | 8.03 | Leucine-rich repeat protein 1 | Involve in protein modification and ubiquitination. Unknow function in viral infection. |

| P02753 | 3.61 | 1.91 | 2.81 | Retinol-binding protein 4/ RBP4 | Low level in acute phase of patients with critical COVID 19 [40]. |

| P29622 | 0.86 | 3.01 | 1.92 | Kallistatin | Inhibits human kininogenase activities of tissue kallikrein. |

| P35269 | 3.70 | 0.54 | 1.25 | General transcription factor IIF subunit/ GTF2F1 | Promote transcription elongation. Unknow function in viral infection. |

| P02745 | 1.69 | 3.45 | 1.33 | Complement C1q subcomponent subunit A | C1q is associated with the proenzymes C1r and C1s to yield C1. |

| P02741 | 2.10 | 6.97 | 0.00 | C reactive protein | Elevated during acute phase in patients with DHF [18]. |

| Q96KN2 | 2.59 | 0.52 | 1.03 | Beta-Ala-His dipeptidase/ CNDP1 | Up regulation in mild COVID patients as a protective mechanism of oxidative stress [41]. |

| O75882 | 2.41 | 1.13 | 0.61 | Attractin | Involved in the initial immune cell clustering during inflammatory response and may regulate chemotactic activity of chemokines. Unknow function in viral infection |

| Q9NZP8 | 2.08 | 2.39 | 1.25 | Complement C1r subcomponent-like protein | Mediates the proteolytic cleavage of HP/haptoglobin in the endoplasmic reticulum. |

| P09493 | 2.48 | 2.69 | 2.66 | Tropomyosin alpha-1 chain/TPM1 | Binds to actin filaments. Hight levels in patients with severe dengue [42]. |

| P08571 | 6.01 | 4.27 | 4.22 | Monocyte differentiation antigen CD14 | Elevated levels in plasma during acute phase of dengue fever [43]. |

| P07195 | 2.24 | 2.18 | 1.89 | L-lactate dehydrogenase B chain | Interconverts simultaneously and stereospecifically pyruvate and lactate. Unknown function in viral infection. |

| P60174 | 1.78 | 2.84 | 2.05 | Triosephosphate isomerase/ TPI1 | Participation in glycolysis and gluconeogenesis. Up regulated during acute phase of infection with RSV [44]. |

| P02679 | 0.69 | 0.95 | 2.06 | Fibrinogen gamma chain/ FGG | Major function in hemostasis. Alteration of coagulation in dengue infection[45]. |

| P43251 | 1.71 | 3.44 | 2.47 | Biotinidase/ BTD | Catalytic release of biotin from biocytin. Unknow function during viral infection. |

| P06748 | 4.46 | 6.20 | 3.16 | Nucleophosmin/ NPM1 | Involved in diverse cellular processes. Enhanced expression in HEK293cells infected with CHIKV [46]. |

| P06454 | 3.89 | 5.17 | 5.75 | Prothymosin alpha/ PTMA | May mediate immune function by conferring resistance to certain opportunistic infections. DENV infection upregulates PTMA expression, leading to suppressing megakaryopoiesis. Plasma levels are elevated in dengue patients and DENV-infected megakaryoblasts [47]. |

| Proteins with AR>2 | 18 | 23 | 14 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).