1. Introduction

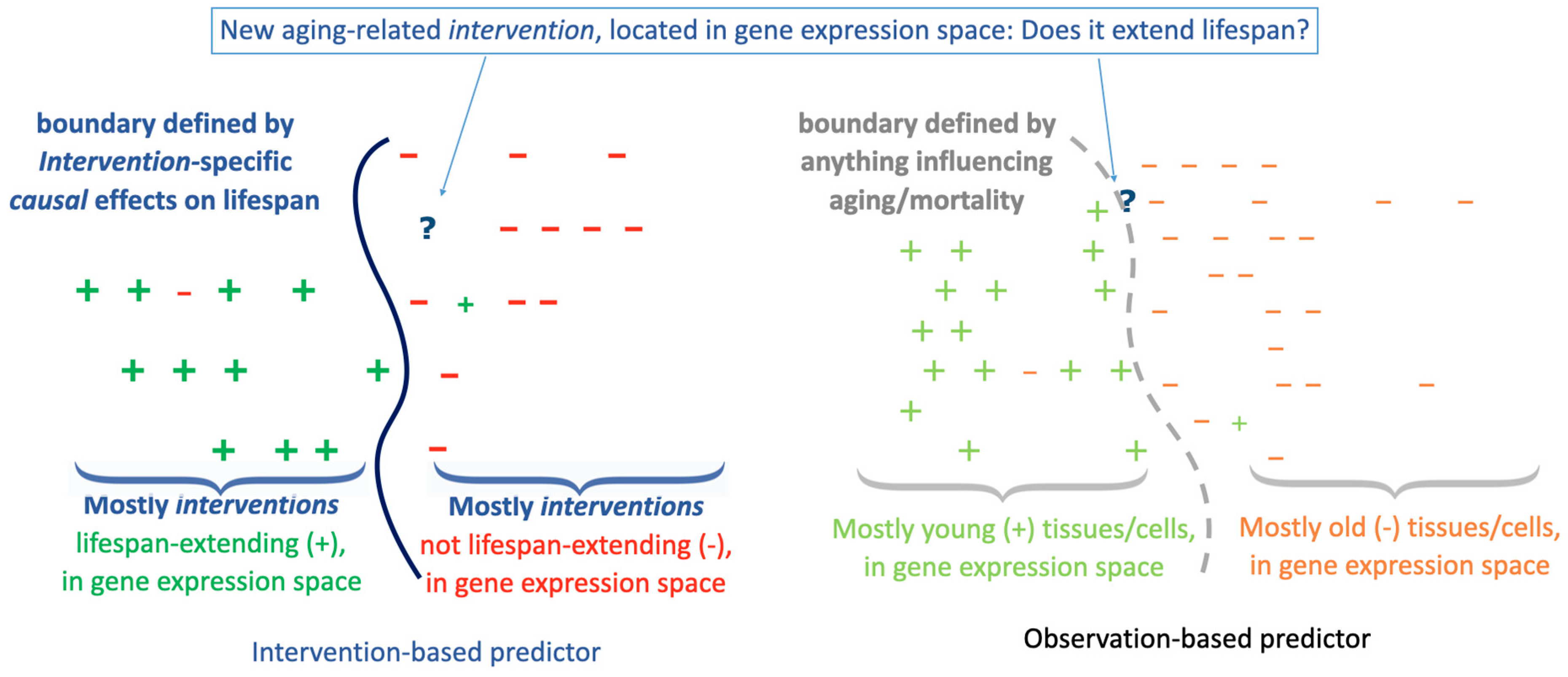

Aging research increasingly focuses on identifying and testing interventions — pharmacological, genetic, dietary or behavioral — that might slow, stop or reverse aging processes and improve health in later life (Lopez-Otin et al., 2013; Lopez-Otin and Kroemer, 2021). Yet, demonstrating long-term health and lifespan benefits and low toxicity in humans is inherently challenging, and clinical studies of long-term health would require to follow participants for decades. Surrogate biomarkers, including blood values, gene expression and methylation data, have risen to prominence, enabling the training of “phenotypic”, transcriptomic and epigenetic aging clocks to predict intervention effects (Fuellen et al., 2019; Hartmann et al., 2021; Hartmann et al., 2023; Moqri et al., 2023; Moqri et al., 2024). However, almost all of these surrogate-based predictors are established exclusively on observational data, not on interventional outcome data. The resulting domain shift can lead to misguided predictions of intervention efficacy, as already noted for reprogramming interventions (Kriukov et al., 2024). Only very recently, (Belikov et al., 2024) published intervention-based predictors to identify compounds that may extend the lifespan of mice (see

Box 1).

In this Review, we examine the rapidly evolving field of in-silico intervention analytics, with a focus on learning from

intervention data rather than observational data whenever possible, see

Figure 1. We also discuss why safety/toxicity considerations are critical in preventive interventions. In depth, we highlight

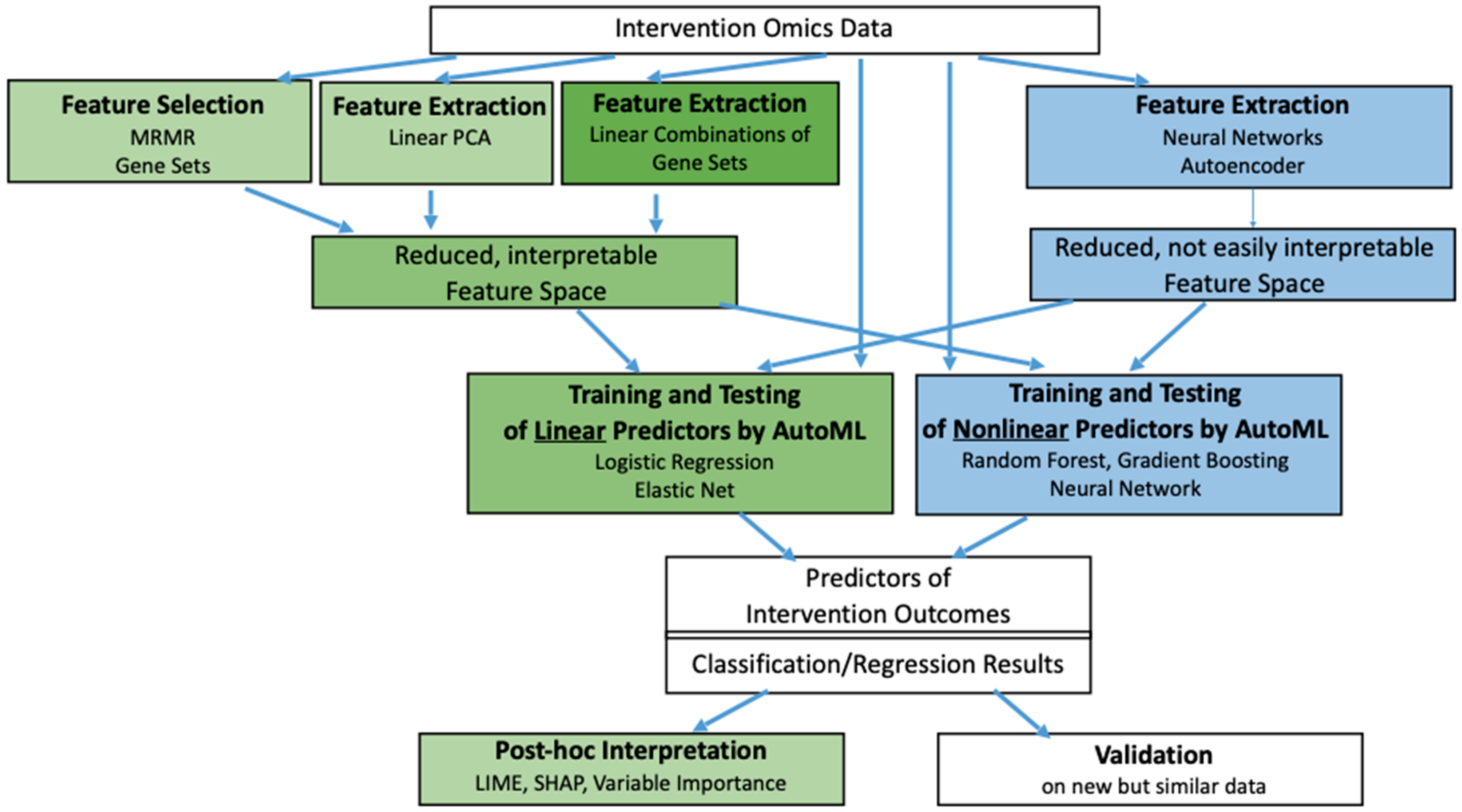

intervention-based benchmarks that enable the comparison of prediction methodologies, see

Table 1. We then delineate two steps important for robust predictions — feature selection/extraction and predictor learning — and survey a variety of established and emerging approaches, see

Figure 2. Feature extraction methods such as principal component analysis (PCA) reduce complexity and can highlight biologically interpretable signatures; predictive modeling approaches range from linear regressors and classifiers to non-linear machine learning methods such as random forests, gradient-boosted trees, and neural networks (Eckhart et al., 2024; Pantazis et al., 2020; Piccolo et al., 2022). Finally, we discuss the emerging use of generative AI and large language models (LLMs) in this context. Although preliminary and often challenging, LLMs could eventually provide excellent assistance in extracting features, building models, and generating mechanistic hypotheses.

Box 1. Predicting Lifespan-Extending Compounds in Mice.

Belikov and colleagues (Belikov et al., 2024) used machine

learning to identify compounds that can extend the lifespan of mice,

leveraging murine lifespan data sourced from the DrugAge database. The

authors used three different kinds of features: (i) direct protein target

annotations, capturing gene ontology and pathway descriptors of a compound’s

protein interactors; (ii) gene expression signatures from the LINCS

repository, using consolidated expression values for each compound; and (iii)

PubChem-based chemical substructure representations. Random Forest models

were trained and tested via cross-validation. Both area under the ROC curve

(AUC) and geometric mean (GMean) metrics were reported; the latter was

usually more appropriate because of imbalances in the dataset. The best

performance arose from the target-based annotations. By contrast, LINCS gene

expression data and chemical substructure representations underperformed,

perhaps because no feature extraction/selection was done. Finally, the study

used selected top models to identify potentially novel lifespan-extending

compounds from DrugBank.

2. The Challenge of Predicting Intervention Outcomes

Predictive modeling of intervention outcomes (e.g., lifespan, health, toxicity) is central to aging research. Yet, most surrogate-based predictors, known as “aging clocks”, are derived from observational data, such as blood cell counts or other laboratory values, transcriptomics or methylation data, from individuals of varying age (Fuellen et al., 2019; Hartmann et al., 2021; Hartmann et al., 2023; Moqri et al., 2023; Moqri et al., 2024). Instead, training predictors directly on intervention data, when interventions with known outcomes and corresponding omics profiles are available, should provide more reliable inference. Why is that so? For a detailed description, let us consider the specific example of training on transcriptomic (gene expression) data after compound intervention, to predict health and lifespan outcomes, as compared to the standard use of aging clocks.

In the conceptual example of

Figure 1 left, the decision boundary of a predictor is visualized, which was learned to decide between interventions that extend lifespan (

+) and interventions that do not (

–), where the feature space is defined by the similarity of the gene expression effects of the interventions. In

Figure 1 right, predictor training was instead based on samples of young (

+) versus old (

–) tissues or cells, again in gene expression similarity space. If the predictors are then asked to classify a new intervention (marked by

?), the predictor on the right suffers from the domain shift from observational to intervention data. Everything else being equal, that is, assuming the same input data quality, etc., the domain shift is expected to trigger inferior results, because

the similarity of interventions can only be directly measured in the space of intervention effects. This domain shift was very recently described for the special case of using aging clocks to assess reprogramming interventions (Kriukov et al., 2024), including ample empirical evidence that the use of observational data for the interpretation of intervention data may be problematic. Moreover, unlike cancer drug development, this difference is not simply about the control imposed by an interventional trial (optimally a randomised controlled clinical trial), to minimise confounding factors and to better establish causality. Judging longevity interventions by standard aging clocks is a unique situation in that the clocks themselves rely solely on observational data; the only “intervention” is the passage of time. Of note, moving from the classification task considered in

Figure 1 to the analogous regression task, the scenario on the right corresponds to the standard way of using observational data for learning aging clocks that are then used to assess intervention effects.

Use of intervention training data is conceptually straightforward as visualized in

Figure 1, but practically challenging: high-quality interventional datasets with paired phenotypic outcome data are scarce. Yet, resources are improving. For long-term health, studies that associate lifespan outcomes in model organisms with intervention-induced omics changes have begun to appear (Belikov et al., 2024), see

Box 1. It thus becomes easier to train predictors directly on intervention data, producing models that are expected to generalize better to new interventions and reduce the uncertainty arising from the conceptual domain shift from observational to interventional data. For toxicity, where the use of intervention data is standard, these are now consolidated in repositories like TOXRIC, which provide large-scale transcriptomic data and well-defined toxicity outcomes (Wu et al., 2023), see

Box 2. Toxicology is not just a role model for predictor learning, though; it is an important and sometimes overlooked aspect of assessing any aging-related intervention.

Box 2. The TOXRIC Database.

TOXRIC (TOxicology Resources for Intelligent Computation) (Wu

et al., 2023) is a large-scale database aimed at supporting the development

and benchmarking of toxicity prediction models. At time of publication, it

contained more than 113,000 compounds, spanning 13 toxicity categories (e.g.,

acute toxicity, ecotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, endocrine disruption) and 1,474

in vivo or in vitro endpoints. A key strength of TOXRIC is its “ML-ready”

focus: the database provides curated, standardized toxicity labels and up to

39 feature types (e.g., molecular fingerprints, transcriptomic profiles,

target annotations), so that these can be used directly as input (features)

or output (labels) for machine learning. For instance, the database offers

transcriptomic readouts from LINCS, Open TG-GATEs, and DrugMatrix, providing

high-dimensional gene expression information after compound exposure.

Structural descriptors and target protein annotations are also included,

broadening the scope of potential modeling strategies. Benchmarking plays a

central role in TOXRIC. Multiple classification and regression tasks are

established (e.g., predicting toxic vs. non-toxic status or estimating LD50),

and performance metrics are reported for four “baseline” algorithms

frequently used in toxicity modeling—eXtreme Gradient Boosting, Random

Forest, Support Vector Machine, and Deep Neural Network. Researchers can

quickly compare how different feature types or model classes perform for each

endpoint, and then download the corresponding data subsets for further

experiments; the website also offers a range of results, visualized

appropriately. In the context of in-silico intervention analytics, TOXRIC’s

standardized datasets and benchmark results offer a comprehensive source of

toxicity information that can be leveraged to train or validate predictive

models focused on toxic effects.

3. The Importance of Safety and Toxicity Assessments

In the context of promoting aging-related interventions, especially in healthy individuals, safety is paramount. Unlike interventions in severely ill patients where some toxicity might be acceptable if the therapeutic benefit is high, preventive aging-related interventions must meet a much higher safety threshold. Predictive modeling efforts must therefore emphasize toxicity and side-effect prediction (Janssens and Houtkooper, 2020; Uner et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2023). Moreover, safety/toxicity considerations can specifically influence the selection of the features on which to focus in the intervention analysis pipeline. For example, when using gene expression data to establish predictors, features may be specifically selected or extracted with toxicity in mind, based on genes known to be involved in toxicity-related processes and pathways (Saarimaki et al., 2023a; Saarimaki et al., 2023b), see also below.

4. Establishing Benchmarks for Model Comparison

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for progress. Without standardized benchmarks, it is difficult to compare methods or assess generalizability. Benchmark datasets should represent various intervention types (e.g., drug treatments, dietary changes) and outcomes (e.g., lifespan, toxicity), and include both successful and neutral or harmful interventions.

Table 1 outlines our suggestions for such intervention-based benchmarks. For toxicity, TOXRIC provides large-scale transcriptomic data linked to various toxicity endpoints (Wu et al., 2023), see also

Box 2. For lifespan extension, data from DrugAge and the Interventions Testing Program (ITP) (Nadon et al., 2008) have recently been curated and connected to LINCS gene expression profiles (Belikov et al., 2024), see also

Box 1. Side-effect data (Kuhn et al., 2016) were also connected to LINCS (Uner et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2016). Integrative datasets, featuring aging-related interventions with functional outcomes and gene expression data, are becoming available (Tyshkovskiy et al., 2024), also, for example, with a focus on partial reprogramming (Browder et al., 2022; Hishida et al., 2022; Sarkar et al., 2020). Additional benchmarks can be constructed for senotherapeutics (Smer-Barreto et al., 2023), nutritional interventions (Ford et al., 2023), and for in-vivo rat toxicity (Gwinn et al., 2020). Using these benchmarks, researchers can systematically compare feature extraction and predictor learning pipelines and monitor performance improvements.

5. Feature Selection/Extraction and Predictor Learning

A pipeline for the interpretable machine learning of intervention effects is described in

Figure 2, consolidating existing approaches already described in (Wu et al., 2023) and (Belikov et al., 2024), and taking inspiration from machine learning of cancer drug sensitivity and cancer type (Eckhart et al., 2024; Pantazis et al., 2020; Piccolo et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2020), in a single unified scheme. In the next sections, the various steps of the pipeline will be discussed in more detail. In our case, the input is high-dimensional high-throughput molecular data, which may, e.g., be the gene expression (transcriptomics), protein abundance (proteomics) or methylation data (epigenomics) measured in control versus intervention samples. These data are frequently undergoing feature processing, by selection (keeping features as they are) or by extraction (calculating new features based on formulas). The consequent reduction of the feature space can avoid overfitting (see below). Training, testing and validation of predictors is then performed based on these features, using the labels associated with the samples, such as lifespan extension or toxicity for classification. Predictors can also employ regression, learning numerical labels. Training/testing refers to the (automated) machine learning of predictors (see below), and validation to the use of the learned predictors on new but similar data, testing their generalizability. (In the literature, the term “testing” sometimes refers to what we call “validation”, and vice versa.) Method choice can strongly influence the ability to assign biological/biomedical meaning to the features underlying the prediction results, enabling various grades of interpretability, which may be intrinsic to the method, but can also be offered by post-hoc analyses, see

Figure 2.

6. Feature Selection/Extraction

Omics data, particularly transcriptomics, often measure thousands of genes. Directly applying machine learning on these high-dimensional, noisy data can lead to overfitting (Eckhart et al., 2024; Smith et al., 2020). Feature selection/extraction simplifies the feature space, generating a smaller set of features.

Linear Methods: MRMR, PCA and Contrastive PCA. A wide variety of feature selection methods are available, exemplified here by Maximum Relevance Minimum Redundancy (MRMR), which is often highlighted for its strong empirical performance and its theoretical appeal, as it aims for features strongly dependent on the outcome but weakly dependent on one another, see (Eckhart et al., 2024). This principle can be implemented in a linear way based on correlation as well as in a non-linear way based on mutual information. A popular linear method for feature extraction is principal component analysis (PCA), which produces features as linear combinations of genes (or other molecular variables) that explain the greatest variance in the data (Ringner, 2008). On that basis, PCA can separate samples by intervention type or outcome and reveal underlying biological processes. Because PCA features are linear, they are often easier to interpret biologically. For instance, certain principal components may correspond to activation of proliferative pathways or stress responses. However, PCA may also capture confounders such as batch effects or differences in experimental conditions. Contrastive PCA (cPCA) is a variant that uses “background” or control datasets to highlight features specific to the intervention condition (Abid et al., 2018; Boileau et al., 2020; de Oliveira et al., 2024). This may be particularly valuable in aging-related intervention studies, where differences in age, species, or tissue can obscure the signal of interest. cPCA may help isolate the molecular signatures of the interventions beyond baseline variability (Iturria-Medina et al., 2022), but this conjecture lacks confirmation for aging-related interventions.

Linear Methods: Gene Set Approaches. Interpretable features can also be derived from annotated gene sets, including biological pathways or processes, and specifically hallmarks of aging, or adverse outcome pathways (Basili et al., 2022; Pun et al., 2022; Saarimaki et al., 2023a; Saarimaki et al., 2023b; Subramanian et al., 2005). Such gene sets may simply define the features to be selected. More frequently, by summarizing expression levels for sets of genes with shared biological meaning, highlighted by their significant up- or downregulation, one obtains “enrichment features” that reflect the activity of entire pathways or processes. Tools like gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), single-sample GSEA, and gene set variation analysis (Hanzelmann et al., 2013; Subramanian et al., 2005) can therefore translate gene expression into biologically interpretable pathway or process enrichment scores, enabling more meaningful comparisons between interventions. Enrichment-based features can also reduce dimensionality and mitigate the risk of overfitting. These gene-set–based features can be visualized in low-dimensional embeddings and network maps, helping researchers identify clusters of interventions that share similar mechanistic signatures (Merico et al., 2010; Nguyen et al., 2021). Such visualization can guide the generation of mechanistic hypotheses and highlight potential safety concerns if certain pathways are associated with toxicity.

Non-linear Dimensionality Reduction. Non-linear methods for feature processing can be based, e.g., on Neural Networks (incl. Autoencoders) (Eckhart et al., 2024). Moreover, non-linear alternatives to PCA, such as UMAP or t-SNE can be used to represent samples in lower-dimensional spaces (Yang et al., 2021), and these representations can be used to define features. While powerful for visualizing complex relationships and subgroups, the results of these methods are harder to interpret biologically. Since interpretability is crucial in preventive health interventions, linear or gene set–based approaches may be preferable.

7. Predictor Learning

Once features are defined, the next step is to train and test predictive models. Such predictors then estimate intervention outcomes (e.g., lifespan extension, toxicity) from the extracted (or selected) features. However, feature processing is an optional step, and generally, predictors can be given all features as-is, even if these are high-dimensional, potentially at the risk of overfitting; some methods can also combine feature selection and predictor definition into a single formula.

Linear Predictors. Linear predictors, including logistic regression or elastic nets, can be combined with PCA-based or gene set–based features to produce interpretable models (Eckhart et al., 2024). The weights assigned to each feature can then highlight biologically meaningful signals and simplify the interpretation of predictions. However, purely linear models may not fully capture the non-linear relationships between gene expression changes and the outcome phenotype.

Non-linear Machine Learning Models. Non-linear models like random forests, gradient boosting (e.g., XGBoost), and neural networks can often but not always yield better predictive performance (Eckhart et al., 2024; Pantazis et al., 2020; Piccolo et al., 2022). In particular, gradient boosting methods have shown strong performance on toxicity benchmarks (Wu et al., 2023) Nevertheless, non-linear models tend to be less interpretable. Techniques like LIME or Shapley values can offer post-hoc explanations (Ortigossa et al., 2024). Random forests also provide variable importance scores that indicate which features are most influential, fostering interpretability. However, balancing accuracy with interpretability remains a challenge. Since safety and transparency are vital, especially for interventions in healthy individuals, simple but interpretable models may sometimes be preferred over complex black-box models.

Automated Machine Learning (AutoML) and Model Ensembles. Given the complexity of feature extraction and the multitude of available predictors, automated machine learning (AutoML) frameworks can expedite the search for optimal intervention analysis pipelines (Tsamardinos et al., 2022). These frameworks systematically test different feature extraction methods, prediction model types, and hyperparameters. Furthermore, ensemble strategies that combine multiple prediction models can yield more robust predictions (Campager et al., 2023). Incorporating uncertainty estimates as suggested by (Kriukov et al., 2024) can further increase the reliability and safety of intervention recommendations.

8. Early Experiences With Generative AI and LLMs

Large language models and related AI techniques hold promise for integrating disparate knowledge sources and generating new hypotheses (Joachimiak et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2024; Pickard et al., 2024; Simm et al., 2024; Tang et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2024; Xin et al., 2024; Zhou et al., 2024). They could assist with data preprocessing, identifying confounders, or proposing candidate gene sets. However, early attempts have shown limitations — such as difficulties in handling complex, messy biological datasets and improper statistical analyses (Joachimiak et al., 2024). In the near future, LLMs might help design improved intervention analysis pipelines, facilitate interpretability, or assist in evaluating interventions against curated benchmarks. At present, generative AI is best viewed as a coding assistant or brainstorming partner rather than a fully autonomous analyst. Ensuring correctness and interpretability remains a major challenge (Fuellen et al., 2024). As such, LLMs should be integrated cautiously, with human oversight and rigorous validation.

9. Perspectives and Future Directions

As the field advances, several key priorities emerge. First, expanding and refining high-quality intervention datasets, both in model organisms and in humans, will improve training and testing of predictive models. Notably, large-scale multi-intervention trials for mice are being run with increasing size and sophistication, e.g. the Robust Mouse Rejuvenation trials (Lewis and de Grey, 2024), and the same holds for human intervention trials, such as DO-Health (Kistler-Fischbacher et al., 2024), CALERIE (Ryan et al., 2024) and Cosmos (Vyas et al., 2024). Second, developing methods that integrate safety and efficacy predictions simultaneously is paramount; aging interventions must be safe if they are to be recommended for healthy individuals. Third, consistent benchmarking and publication of standardized protocols will foster reproducibility and progress. Fourth, the tension between model complexity and interpretability will continue to shape methodological choices. Achieving explainability without sacrificing accuracy, and providing robust uncertainty estimates to guard against overconfident predictions, will be crucial. Finally, incorporating generative AI tools in a transparent and carefully monitored manner may lead to innovative modeling strategies and new insights.

10. Conclusions

Validated and explainable predictive models for intervention outcomes would profoundly enhance our ability to identify strategies that extend lifespan and reduce disease and dysfunction. By prioritizing training on intervention data, consideration of safety/toxicity, and embracing robust benchmarks, we can better predict real-world outcomes, optimally with strong interpretability. As the available datasets and computational tools improve, in-silico evaluation can become an indispensable asset for aging-related intervention research, complementing experimental studies and ultimately informing clinical and public health decisions.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant DFG FU 583/7-1 to G.F.), by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant FKZ 01ZX1903A to G.F.), and by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs (grant FKZ 03EGTMV007 to D.P., R.A.A., supporting the development of innovative startups originating from academic research).

Conflicts of Interest

G.F. received funding from Karls Erdbeerhof (Karls strawberry farm), Rövershagen, Germany. C.F. received consulting fees from the Rostock University Medical Center. G.F., D.P. and R.A.A. are planning a startup related to this research. The authors declare that they have no other known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work the authors used the GPT family of tools in order to survey the literature and for structuring the text. After using this tool/service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article. All contents of the text and the figures were originally drafted by the authors, and the final text was scrutinized word-by-word by the first author, with the assistance of the other authors.

References

- Abid, A. , Zhang, M.J., Bagaria, V.K., Zou, J. 2018. Exploring patterns enriched in a dataset with contrastive principal component analysis. Nat Commun 9, 2134. [CrossRef]

- Basili, D. , Reynolds, J., Houghton, J., Malcomber, S., Chambers, B., Liddell, M., Muller, I., White, A., Shah, I., Everett, L.J., Middleton, A., Bender, A. 2022. Latent Variables Capture Pathway-Level Points of Departure in High-Throughput Toxicogenomic Data. Chem Res Toxicol 35, 670-683. [CrossRef]

- Belikov, A.V. , Ribeiro, C., Farmer, C.K., de Magalhaes, J.P., Freitas, A.A. 2024. Predicting Mouse Lifespan-Extending Chemical Compounds with Machine Learning. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Boileau, P. , Hejazi, N.S., Dudoit, S. 2020. Exploring high-dimensional biological data with sparse contrastive principal component analysis. Bioinformatics 36, 3422-3430. [CrossRef]

- Browder, K.C. , Reddy, P., Yamamoto, M., Haghani, A., Guillen, I.G., Sahu, S., Wang, C., Luque, Y., Prieto, J., Shi, L., Shojima, K., Hishida, T., Lai, Z., Li, Q., Choudhury, F.K., Wong, W.R., Liang, Y., Sangaraju, D., Sandoval, W., Esteban, C.R., Delicado, E.N., Garcia, P.G., Pawlak, M., Vander Heiden, J.A., Horvath, S., Jasper, H., Izpisua Belmonte, J.C. 2022. In vivo partial reprogramming alters age-associated molecular changes during physiological aging in mice. Nat Aging 2, 243-253. [CrossRef]

- Campager, A. , Ciucci, D., Cabitza, F. 2023. Aggregation models in ensemble learning: A large-scale comparison. Information Fusion 90, 241-252. [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, E.F. , Garg, P., Hjerling-Leffler, J., Batista-Brito, R., Sjulson, L. 2024. Identifying patterns differing between high-dimensional datasets with generalized contrastive PCA. bioRxiv. [CrossRef]

- Eckhart, L. , Lenhof, K., Rolli, L.M., Lenhof, H.P. 2024. A comprehensive benchmarking of machine learning algorithms and dimensionality reduction methods for drug sensitivity prediction. Brief Bioinform 25. [CrossRef]

- Ford, M.L. , Cooley, J.M., Sripada, V., Xu, Z., Erickson, J.S., Bennett, K.P., Crawford, D.R. 2023. Eat4Genes: a bioinformatic rational gene targeting app and prototype model for improving human health. Front Nutr 10, 1196520. [CrossRef]

- Fuellen, G. , Jansen, L., Cohen, A.A., Luyten, W., Gogol, M., Simm, A., Saul, N., Cirulli, F., Berry, A., Antal, P., Kohling, R., Wouters, B., Moller, S. 2019. Health and Aging: Unifying Concepts, Scores, Biomarkers and Pathways. Aging Dis 10, 883-900. [CrossRef]

- Fuellen, G. , Kulaga, A., Lobentanzer, S., Unfried, M., Avelar, R.A., Palmer, D., Kennedy, B.K. 2024. Validation Requirements for AI-based Intervention-Evaluation in Aging and Longevity Research and Practice. Ageing Res Rev 104, 102617. [CrossRef]

- Gwinn, W.M. , Auerbach, S.S., Parham, F., Stout, M.D., Waidyanatha, S., Mutlu, E., Collins, B., Paules, R.S., Merrick, B.A., Ferguson, S., Ramaiahgari, S., Bucher, J.R., Sparrow, B., Toy, H., Gorospe, J., Machesky, N., Shah, R.R., Balik-Meisner, M.R., Mav, D., Phadke, D.P., Roberts, G., DeVito, M.J. 2020. Evaluation of 5-day In Vivo Rat Liver and Kidney With High-throughput Transcriptomics for Estimating Benchmark Doses of Apical Outcomes. Toxicol Sci 176, 343-354. [CrossRef]

- Hanzelmann, S. , Castelo, R., Guinney, J. 2013. GSVA: gene set variation analysis for microarray and RNA-seq data. BMC Bioinformatics 14, 7. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, A. , Hartmann, C., Secci, R., Hermann, A., Fuellen, G., Walter, M. 2021. Ranking Biomarkers of Aging by Citation Profiling and Effort Scoring. Front Genet 12, 686320. [CrossRef]

- Hartmann, C. , Herling, L., Hartmann, A., Kockritz, V., Fuellen, G., Walter, M., Hermann, A. 2023. Systematic estimation of biological age of in vitro cell culture systems by an age-associated marker panel. Front Aging 4, 1129107. [CrossRef]

- Hishida, T. , Yamamoto, M., Hishida-Nozaki, Y., Shao, C., Huang, L., Wang, C., Shojima, K., Xue, Y., Hang, Y., Shokhirev, M., Memczak, S., Sahu, S.K., Hatanaka, F., Ros, R.R., Maxwell, M.B., Chavez, J., Shao, Y., Liao, H.K., Martinez-Redondo, P., Guillen-Guillen, I., Hernandez-Benitez, R., Esteban, C.R., Qu, J., Holmes, M.C., Yi, F., Hickey, R.D., Garcia, P.G., Delicado, E.N., Castells, A., Campistol, J.M., Yu, Y., Hargreaves, D.C., Asai, A., Reddy, P., Liu, G.H., Izpisua Belmonte, J.C. 2022. In vivo partial cellular reprogramming enhances liver plasticity and regeneration. Cell Rep 39, 110730. [CrossRef]

- Iturria-Medina, Y. , Adewale, Q., Khan, A.F., Ducharme, S., Rosa-Neto, P., O'Donnell, K., Petyuk, V.A., Gauthier, S., De Jager, P.L., Breitner, J., Bennett, D.A. 2022. Unified epigenomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic taxonomy of Alzheimer's disease progression and heterogeneity. Sci Adv 8, eabo6764. [CrossRef]

- Janssens, G.E. , Houtkooper, R.H. 2020. Identification of longevity compounds with minimized probabilities of side effects. Biogerontology 21, 709-719. [CrossRef]

- Joachimiak, M.P. , Caufield, J.H., Harris, N.L., Kim, H., Mungall, C.J. 2024. Gene Set Summarization Using Large Language Models. ArXiv.

- Kistler-Fischbacher, M. , Armbrecht, G., Gangler, S., Theiler, R., Rizzoli, R., Dawson-Hughes, B., Kanis, J.A., Hofbauer, L.C., Schimmer, R.C., Vellas, B., Da Silva, J.A.P., John, O.E., Kressig, R.W., Andreas, E., Lang, W., Wanner, G.A., Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A., Group, D.-H.R. 2024. Effects of vitamin D3, omega-3s, and a simple strength training exercise program on bone health: the DO-HEALTH randomized controlled trial. J Bone Miner Res 39, 661-671. [CrossRef]

- Kriukov, D. , Kuzmina, E., Efimov, E., Dylov, D.V., Khrameeva, E.E. 2024. Epistemic uncertainty challenges aging clock reliability in predicting rejuvenation effects. Aging Cell, e14283. [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. , Letunic, I., Jensen, L.J., Bork, P. 2016. The SIDER database of drugs and side effects. Nucleic Acids Res 44, D1075-1079. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, C.J. , de Grey, A.D. 2024. Combining rejuvenation interventions in rodents: a milestone in biomedical gerontology whose time has come. Expert Opin Ther Targets 28, 501-511. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. , Yang, M., Yu, Y., Xu, H., Li, K., Zhou, X. 2024. Large language models in bioinformatics: applications and perspectives. arXiv:2401.04155.

- Lopez-Otin, C. , Blasco, M.A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., Kroemer, G. 2013. The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194-1217. [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Otin, C. , Kroemer, G. 2021. Hallmarks of Health. Cell 184, 33-63. [CrossRef]

- Merico, D. , Isserlin, R., Stueker, O., Emili, A., Bader, G.D. 2010. Enrichment map: a network-based method for gene-set enrichment visualization and interpretation. PLoS One 5, e13984. [CrossRef]

- Moqri, M. , Herzog, C., Poganik, J.R., Justice, J., Belsky, D.W., Higgins-Chen, A., Moskalev, A., Fuellen, G., Cohen, A.A., Bautmans, I., Widschwendter, M., Ding, J., Fleming, A., Mannick, J., Han, J.J., Zhavoronkov, A., Barzilai, N., Kaeberlein, M., Cummings, S., Kennedy, B.K., Ferrucci, L., Horvath, S., Verdin, E., Maier, A.B., Snyder, M.P., Sebastiano, V., Gladyshev, V.N. 2023. Biomarkers of aging for the identification and evaluation of longevity interventions. Cell 186, 3758-3775. [CrossRef]

- Moqri, M. , Herzog, C., Poganik, J.R., Ying, K., Justice, J.N., Belsky, D.W., Higgins-Chen, A., Chen, B.H., Cohen, A.A., Fuellen, G., Hagg, S., Marioni, R.E., Widschwendter, M., Fortney, K., Fedichev, P.O., Zhavoronkov, A., Barzilai, N., Lasky-Su, J., Kiel, D.P., Kennedy, B.K., Cummings, S., Slagboom, P.E., Verdin, E., Maier, A.B., Sebastiano, V., Snyder, M.P., Gladyshev, V.N., Horvath, S., Ferrucci, L. 2024. Validation of biomarkers of aging. Nat Med 30, 360-372. [CrossRef]

- Nadon, N.L. , Strong, R., Miller, R.A., Nelson, J., Javors, M., Sharp, Z.D., Peralba, J.M., Harrison, D.E. 2008. Design of aging intervention studies: the NIA interventions testing program. Age (Dordr) 30, 187-199. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H. , Tran, D., Galazka, J.M., Costes, S.V., Beheshti, A., Petereit, J., Draghici, S., Nguyen, T. 2021. CPA: a web-based platform for consensus pathway analysis and interactive visualization. Nucleic Acids Res 49, W114-W124. [CrossRef]

- Ortigossa, E.S. , Gonçalves, T., Nonato, L.G. 2024. EXplainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI)—From Theory to Methods and Applications. IEEE Access 24, 80799-80846. [CrossRef]

- Pantazis, Y. , Tselas, C., Lakiotaki, K., Lagani, V., Tsamardinos, I. 2020. Latent Feature Representations for Human Gene Expression Data Improve Phenotypic Predictions, 2020 IEEE International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedicine (BIBM). IEEE, pp. 2505-2512. [CrossRef]

- Piccolo, S.R. , Mecham, A., Golightly, N.P., Johnson, J.L., Miller, D.B. 2022. The ability to classify patients based on gene-expression data varies by algorithm and performance metric. PLoS Comput Biol 18, e1009926. [CrossRef]

- Pickard, J. , Choi, M.A., Oliven, N., Stansbury, C., Cwycyshyn, J., Galioto, N., Gorodetsky, A., Velasquez, A., Rajapakse, I. 2024. Bioinformatics Retrieval Augmentation Data (BRAD) Digital Assistant. arXiv:2409.02864.

- Pun, F.W. , Leung, G.H.D., Leung, H.W., Liu, B.H.M., Long, X., Ozerov, I.V., Wang, J., Ren, F., Aliper, A., Izumchenko, E., Moskalev, A., de Magalhaes, J.P., Zhavoronkov, A. 2022. Hallmarks of aging-based dual-purpose disease and age-associated targets predicted using PandaOmics AI-powered discovery engine. Aging (Albany NY) 14, 2475-2506. [CrossRef]

- Ringner, M. 2008. What is principal component analysis? Nat Biotechnol 26, 303-304. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, C.P. , Corcoran, D.L., Banskota, N., Eckstein Indik, C., Floratos, A., Friedman, R., Kobor, M.S., Kraus, V.B., Kraus, W.E., MacIsaac, J.L., Orenduff, M.C., Pieper, C.F., White, J.P., Ferrucci, L., Horvath, S., Huffman, K., Belsky, D.W. 2024. The CALERIE™ Genomic Data Resource. BioArxiv 10.1101/2024.05.17.594714. [CrossRef]

- Saarimaki, L.A. , Fratello, M., Pavel, A., Korpilahde, S., Leppanen, J., Serra, A., Greco, D. 2023a. A curated gene and biological system annotation of adverse outcome pathways related to human health. Sci Data 10, 409. [CrossRef]

- Saarimaki, L.A. , Morikka, J., Pavel, A., Korpilahde, S., Del Giudice, G., Federico, A., Fratello, M., Serra, A., Greco, D. 2023b. Toxicogenomics Data for Chemical Safety Assessment and Development of New Approach Methodologies: An Adverse Outcome Pathway-Based Approach. Adv Sci (Weinh) 10, e2203984. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, T.J. , Quarta, M., Mukherjee, S., Colville, A., Paine, P., Doan, L., Tran, C.M., Chu, C.R., Horvath, S., Qi, L.S., Bhutani, N., Rando, T.A., Sebastiano, V. 2020. Transient non-integrative expression of nuclear reprogramming factors promotes multifaceted amelioration of aging in human cells. Nat Commun 11, 1545. [CrossRef]

- Simm, A. , Grosskopf, A., Fuellen, G. 2024. Detailing the biomedical aspects of geroscience by molecular data and large-scale "deep" bioinformatics analyses. Z Gerontol Geriatr 57, 355-360. [CrossRef]

- Smer-Barreto, V. , Quintanilla, A., Elliott, R.J.R., Dawson, J.C., Sun, J., Campa, V.M., Lorente-Macias, A., Unciti-Broceta, A., Carragher, N.O., Acosta, J.C., Oyarzun, D.A. 2023. Discovery of senolytics using machine learning. Nat Commun 14, 3445. [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M. , Walsh, J.R., Long, J., Davis, C.B., Henstock, P., Hodge, M.R., Maciejewski, M., Mu, X.J., Ra, S., Zhao, S., Ziemek, D., Fisher, C.K. 2020. Standard machine learning approaches outperform deep representation learning on phenotype prediction from transcriptomics data. BMC Bioinformatics 21, 119. [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A. , Tamayo, P., Mootha, V.K., Mukherjee, S., Ebert, B.L., Gillette, M.A., Paulovich, A., Pomeroy, S.L., Golub, T.R., Lander, E.S., Mesirov, J.P. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102, 15545-15550. [CrossRef]

- Tang, X. , Qian, B., Gao, R., Chen, J., Chen, X., Gerstein, M.B. 2024. BioCoder: a benchmark for bioinformatics code generation with large language models. Bioinformatics 40, i266-i276. [CrossRef]

- Tsamardinos, I. , Charonyktakis, P., Papoutsoglou, G., Borboudakis, G., Lakiotaki, K., Zenklusen, J.C., Juhl, H., Chatzaki, E., Lagani, V. 2022. Just Add Data: automated predictive modeling for knowledge discovery and feature selection. NPJ Precis Oncol 6, 38. [CrossRef]

- Tyshkovskiy, A. , Kholdina, D., Ying, K., Davitadze, M., Molière, A., Tongu, Y., Kasahara, T., Kats, L.M., Vladimirova, A., Moldakozhyev, A., Liu, H., Zhang, B., Khasanova, U., Moqri, M., Van Raamsdonk, J.M., Harrison, D.E., Strong, R., Abe, T., Dmitriev, S.E., Gladyshev, V.N. 2024. Transcriptomic Hallmarks of Mortality Reveal Universal and Specific Mechanisms of Aging, Chronic Disease, and Rejuvenation. BioRxiv 10.1101/2024.07.04.601982. [CrossRef]

- Uner, O.C. , Kuru, H.I., Cinbis, R.G., Tastan, O., Cicek, A.E. 2023. DeepSide: A Deep Learning Approach for Drug Side Effect Prediction. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform 20, 330-339. [CrossRef]

- Vyas, C.M. , Manson, J.E., Sesso, H.D., Rist, P.M., Weinberg, A., Kim, E., Moorthy, M.V., Cook, N.R., Okereke, O.I. 2024. Effect of cocoa extract supplementation on cognitive function: results from the clinic subcohort of the COSMOS trial. Am J Clin Nutr 119, 39-48. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. , Wang, J., Athiwaratkun, B., Zheng, C., Zou, J. 2024. Mixture-of-Agents Enhances Large Language Model Capabilities. arXiv:2406.04692.

- Wang, Z. , Clark, N.R., Ma'ayan, A. 2016. Drug-induced adverse events prediction with the LINCS L1000 data. Bioinformatics 32, 2338-2345. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L. , Yan, B., Han, J., Li, R., Xiao, J., He, S., Bo, X. 2023. TOXRIC: a comprehensive database of toxicological data and benchmarks. Nucleic Acids Res 51, D1432-D1445. [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q. , Kong, Q., Ji, H., Shen, Y., Liu, Y., Y, S., Zhang, Z., Li, Z., Xia, X., Deng, B., Bai, Y. 2024. BioInformatics Agent (BIA): Unleashing the Power of Large Language Models to Reshape Bioinformatics Workflow. bioRxiv 2024.05.22.595240.

- Yang, Y. , Sun, H., Zhang, Y., Zhang, T., Gong, J., Wei, Y., Duan, Y.G., Shu, M., Yang, Y., Wu, D., Yu, D. 2021. Dimensionality reduction by UMAP reinforces sample heterogeneity analysis in bulk transcriptomic data. Cell Rep 36, 109442. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. , Zhang, B., Li, G., Chen, X., Li, H., Xu, X., Chen, S., He, W., Xu, C., Liu, L., Gao, X. 2024. An AI Agent for Fully Automated Multi-Omic Analyses. Adv Sci (Weinh), e2407094. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).