Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

24 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Growth Associated Protein-43 (GAP-43) is a calmodulin-binding protein, originally found in neurons, that in skeletal muscle regulates handlings of intracellular Ca2+ dynamics. According to its role in Ca2+ regulation, myotubes from GAP-43-null mice display alterations in spontaneous Ca2+ oscillations and evoked Ca2+ release. Emerging hypothesis is that GAP-43 regulates CaM interac-tions with RyR and DHPR Ca2+ channels. Loss of GAP-43 promotes cardiac hypertrophy in new-born knockout mice, extending the physiological role of GAP43 in cardiac muscle. We investigated the role of GAP-43 in cardiomyocytes deriving from GAP-43 knockout (GAP-43-/-) mice, evaluating intracellular Ca2+ variation and its correlation with the levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS), considering their importance in cardiovascular physiology. In GAP-43-/- cardiomyocytes we found increased expression of markers of cardiac hypertrophy, Ca2+ alterations and high mitochondria ROS levels (O2.¯) together with increased oxidized functional proteins. The treatment with a CaM inhibitor (W7) restored Ca2+ and ROS alterations possibly due to high mitochondrial Ca2+ entry by mitochondrial Ca2+ uniporter. Indeed, Ru360 was able to abolish the O2.¯ mitochondrial production. Our results suggest that GAP-43 has a key role in the regulation of Ca2+ and ROS homeostasis, whose alterations could trigger heart disease.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Materials

2.2. Animal Models

2.3. Isolation of Primary Cardiomyocytes from Neonatal Mouse Heart

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. Cytosolic and Mitochondrial Ca2+ Imaging

2.6. ROS and Mitochondrial Superoxide Anion Levels Measurements

2.7. Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Measurements

2.8. Immunofluorescence Staining

2.9. Measurements of Glucose and Lactate Levels in Cell Culture Medium

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

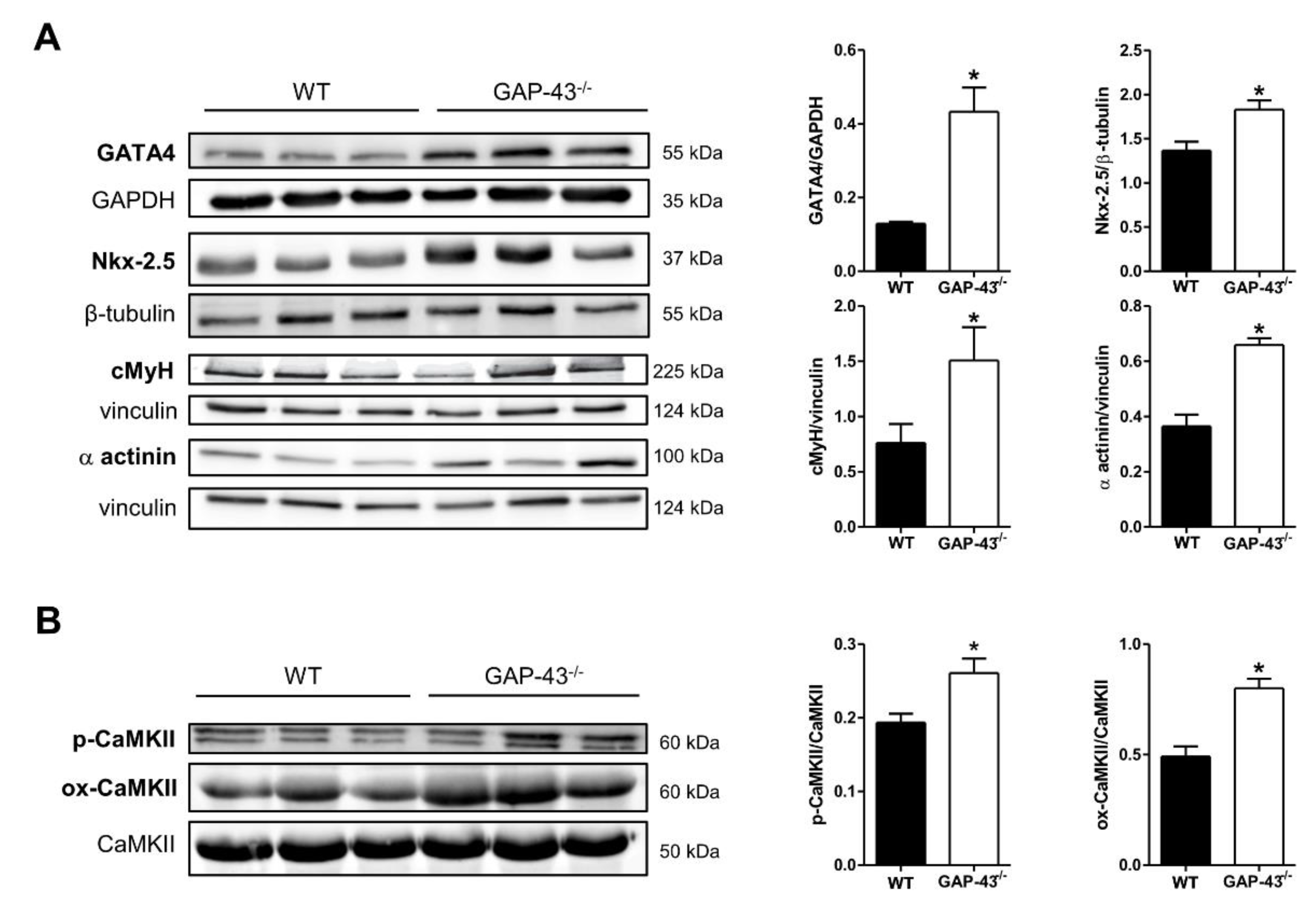

3.1. GAP-43 Knockout Cardiomyocytes Express a Hypertrophic Phenotype

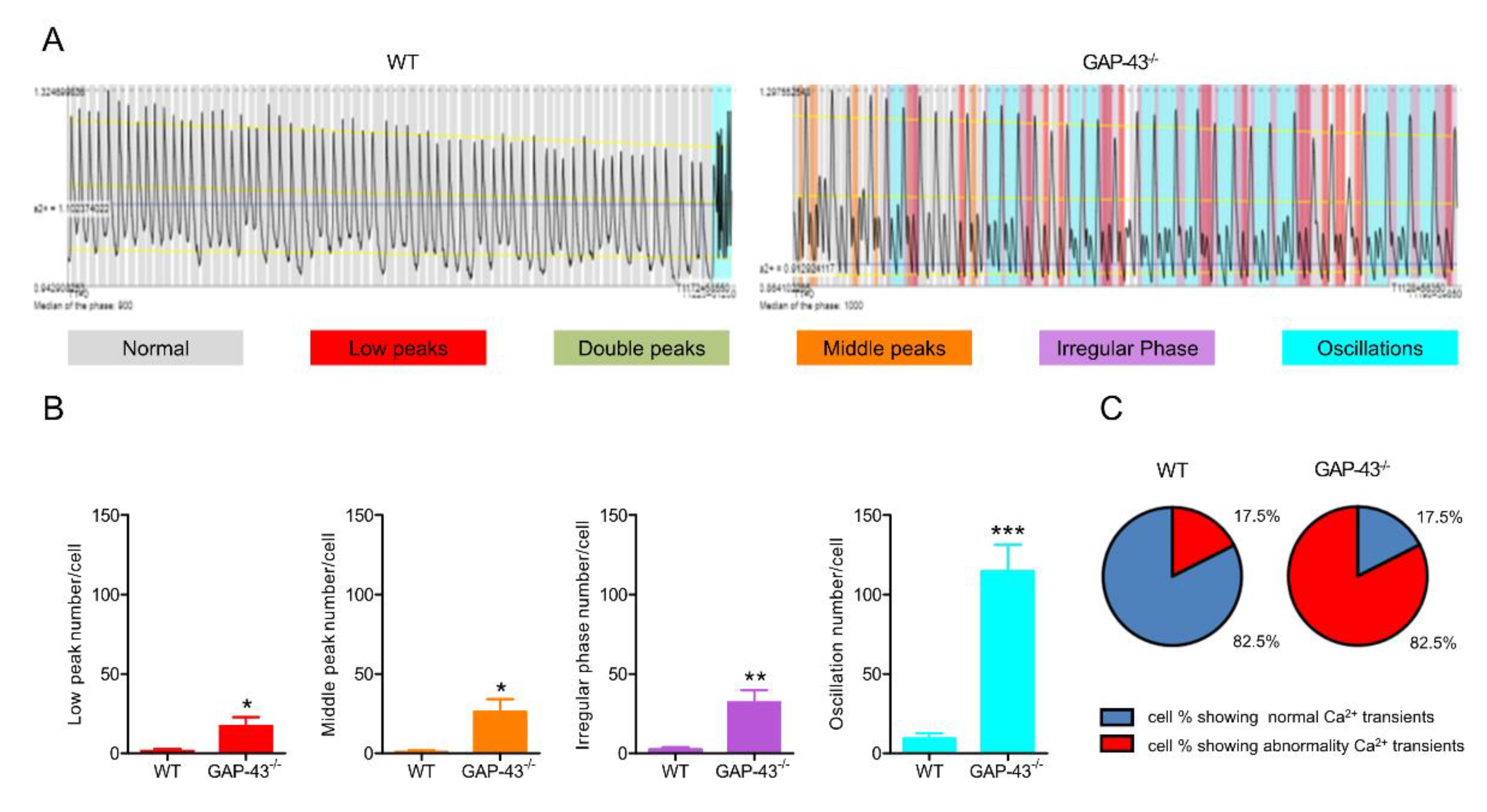

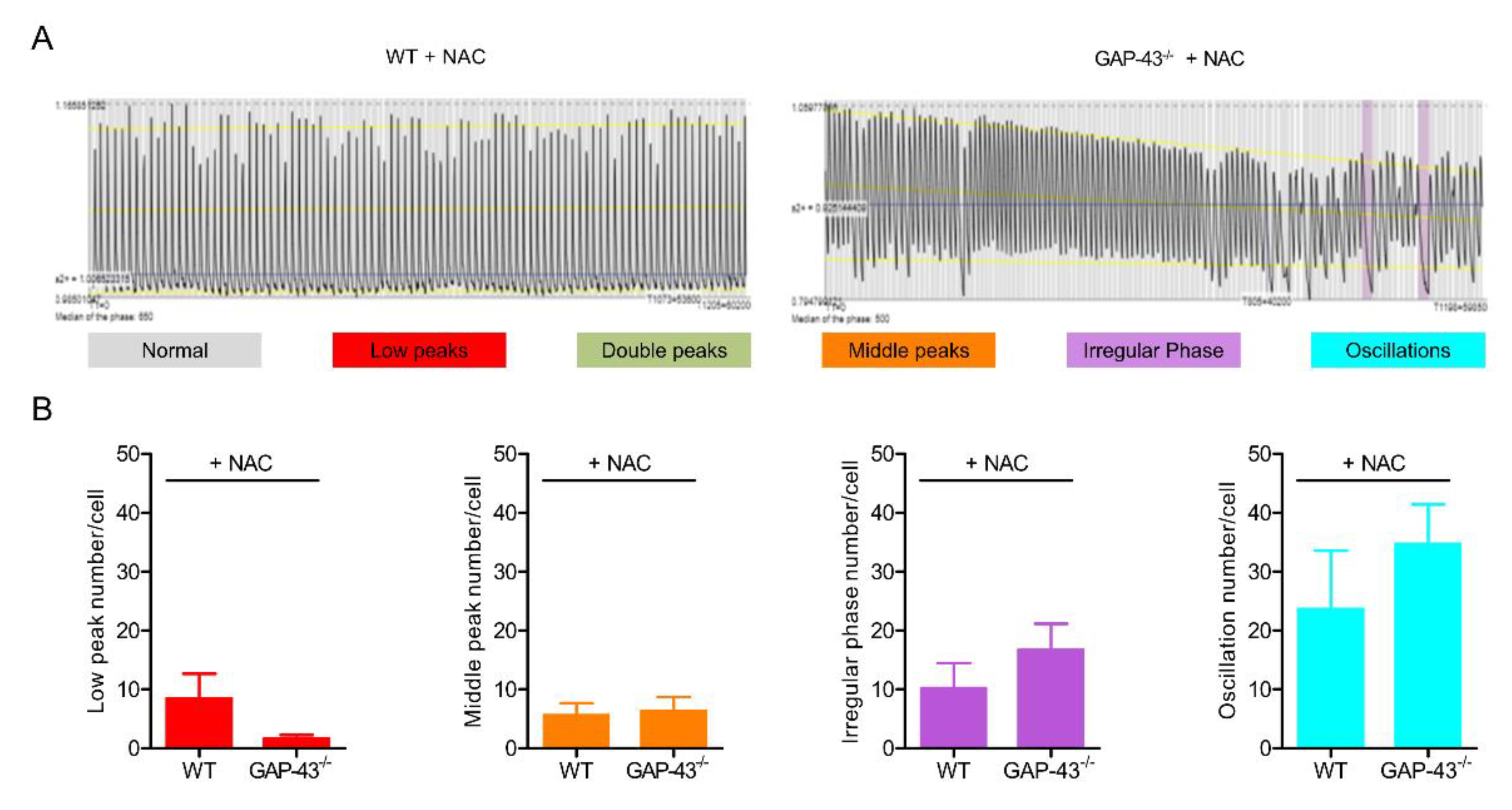

3.2. GAP-43 Knockout Cardiomyocytes Show Intracellular Ca2+ Dyshomeostasis.

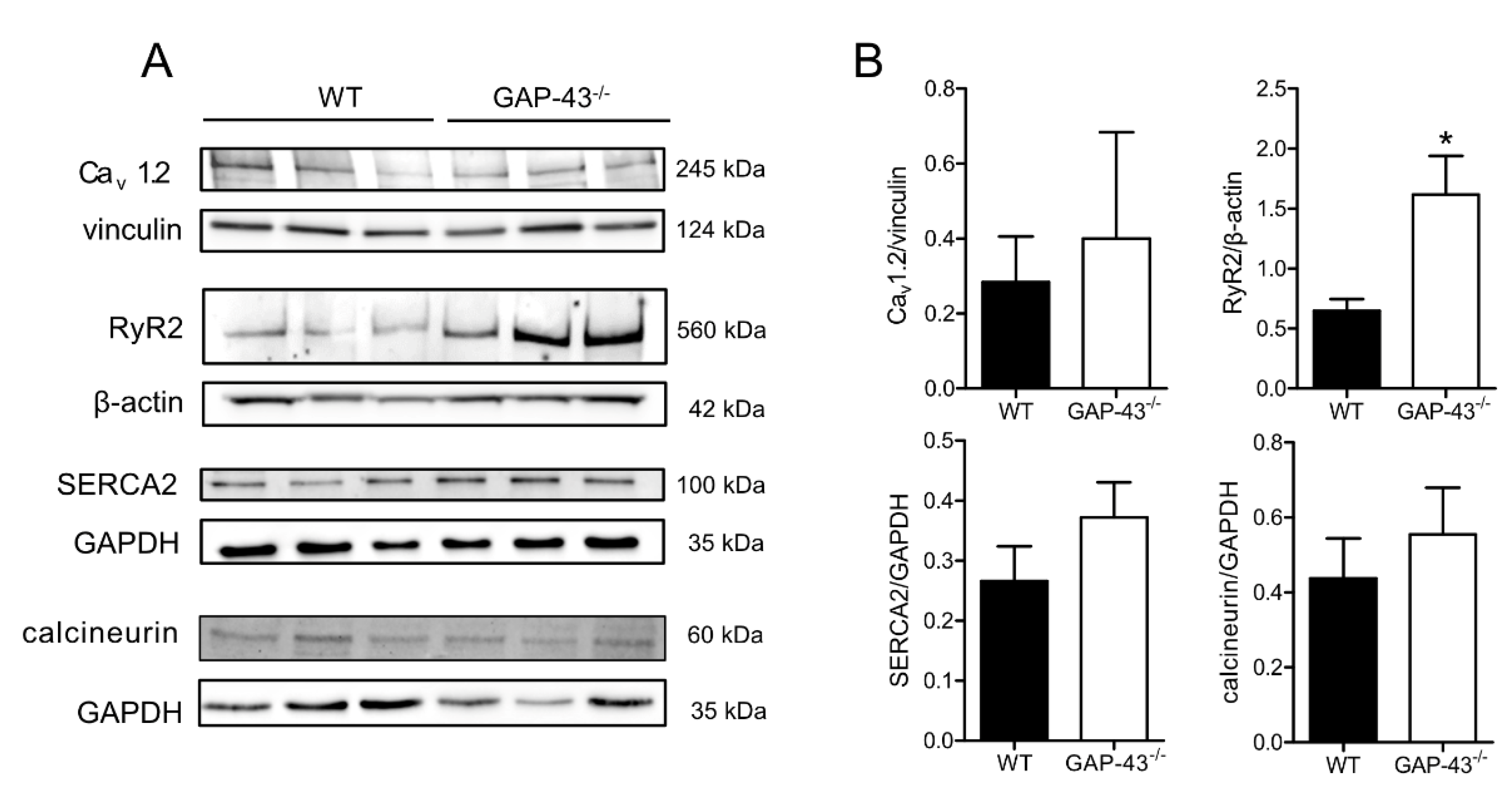

3.3. Expression Levels of Ca2+ Handling Proteins

3.4. GAP43-/- Cardiomyocytes Produce Increased Amounts of ROS.

3.5. GAP-43-/- Mitochondria Show Altered Morphology and Metabolism

3.5. GAP-43-/- Mitochondria Shows Ca2+ Overload and Superoxide Production

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Strittmatter, S.M.; Fankhauser, C.; Huang, P.L.; Mashimo, H.; Fishman, M.C. Neuronal pathfinding is abnormal in mice lacking the neuronal growth cone protein GAP-43. Cell 1995, 80, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cunha, A.; Vitkovic, L. Regulation of immunoreactive GAP-43 expression in rat cortical macroglia is cell type specific. J Cell Biol 1990, 111, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deloulme, J.C.; Janet, T.; Au, D.; Storm, D.R.; Sensenbrenner, M.; Baudier, J. Neuromodulin (GAP43): a neuronal protein kinase C substrate is also present in 0-2A glial cell lineage. Characterization of neuromodulin in secondary cultures of oligodendrocytes and comparison with the neuronal antigen. J Cell Biol 1990, 111, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stocker, K.M.; Ciment, G.; Baizer, L. GAP-43 in non-neuronal cells of the embryonic chick limb: clues to function. Perspect Dev Neurobiol 1992, 1, 53–62. [Google Scholar]

- Heuss, D.; Schlotzer-Schrehardt, U. Subcellular localization of phosphoprotein B-50 in regenerating muscle. An immuno-electron microscopic study. Neurol Res 1998, 20, 360–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarnieri, S.; Morabito, C.; Paolini, C.; Boncompagni, S.; Pilla, R.; Fano-Illic, G.; Mariggio, M.A. Growth associated protein 43 is expressed in skeletal muscle fibers and is localized in proximity of mitochondria and calcium release units. PLoS One 2013, 8, e53267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.A.; Perni, S.; Morabito, C.; Mariggio, M.A.; Guarnieri, S. Specific association of growth-associated protein 43 with calcium release units in skeletal muscles of lower vertebrates. European journal of histochemistry : EJH 2014, 58, 2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosevitsky, M.I. Nerve ending "signal" proteins GAP-43, MARCKS, and BASP1. Int Rev Cytol 2005, 245, 245–325. [Google Scholar]

- Caprara, G.A.; Morabito, C.; Perni, S.; Navarra, R.; Guarnieri, S.; Mariggio, M.A. Evidence for Altered Ca(2+) Handling in Growth Associated Protein 43-Knockout Skeletal Muscle. Frontiers in physiology 2016, 7, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmati, M.; Taherabadi, S.J. The effects of exercise training on Kinesin and GAP-43 expression in skeletal muscle fibers of STZ-induced diabetic rats. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 9535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevere, M.; Morabito, C.; Guarnieri, S.; Mariggio, M.A. Mice lacking growth-associated protein 43 develop cardiac remodeling and hypertrophy. Histochemistry and cell biology 2022, 157, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helms, A.S.; Alvarado, F.J.; Yob, J.; Tang, V.T.; Pagani, F.; Russell, M.W.; Valdivia, H.H.; Day, S.M. Genotype-Dependent and -Independent Calcium Signaling Dysregulation in Human Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2016, 134, 1738–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turrens, J.F. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol 2003, 552, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aon, M.A.; Cortassa, S.; Marban, E.; O'Rourke, B. Synchronized whole cell oscillations in mitochondrial metabolism triggered by a local release of reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 44735–44744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penttinen, K.; Siirtola, H.; Avalos-Salguero, J.; Vainio, T.; Juhola, M.; Aalto-Setala, K. Novel Analysis Software for Detecting and Classifying Ca2+ Transient Abnormalities in Stem Cell-Derived Cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0135806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morabito, C.; Rovetta, F.; Bizzarri, M.; Mazzoleni, G.; Fano, G.; Mariggio, M.A. Modulation of redox status and calcium handling by extremely low frequency electromagnetic fields in C2C12 muscle cells: A real-time, single-cell approach. Free Radic Biol Med 2010, 48, 579–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berardini, M.; Gesualdi, L.; Morabito, C.; Ferranti, F.; Reale, A.; Zampieri, M.; Karpach, K.; Tinari, A.; Bertuccini, L.; Guarnieri, S.; et al. Simulated Microgravity Exposure Induces Antioxidant Barrier Deregulation and Mitochondria Enlargement in TCam-2 Cell Spheroids. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tham, Y.K.; Bernardo, B.C.; Ooi, J.Y.; Weeks, K.L.; McMullen, J.R. Pathophysiology of cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure: signaling pathways and novel therapeutic targets. Arch Toxicol 2015, 89, 1401–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; De Windt, L.J.; Witt, S.A.; Kimball, T.R.; Markham, B.E.; Molkentin, J.D. The transcription factors GATA4 and GATA6 regulate cardiomyocyte hypertrophy in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 2001, 276, 30245–30253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akazawa, H.; Komuro, I. Roles of cardiac transcription factors in cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 2003, 92, 1079–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridinger, H.; Rutenberg, C.; Lutz, D.; Buness, A.; Petersen, I.; Amann, K.; Maercker, C. Expression and tissue localization of beta-catenin, alpha-actinin and chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan 6 is modulated during rat and human left ventricular hypertrophy. Exp Mol Pathol 2009, 86, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, A.B.; Sondergaard, M.T.; Overgaard, M.T. Calmodulin in a heartbeat. FEBS J 2013, 280, 5511–5532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bers, D.M. Altered cardiac myocyte Ca regulation in heart failure. Physiology (Bethesda) 2006, 21, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazeto, I.F.S.; Okoshi, K.; Silveira, C.; Sant'Ana, P.G.; Silva, V.L.D.; Mota, G.A.F.; Souza, S.L.B.; Vileigas, D.F.; Padovani, C.R.; Cicogna, A.C. Calcium homeostasis behavior and cardiac function on left ventricular remodeling by pressure overload. Braz J Med Biol Res 2021, 54, e10138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yano, M.; Ikeda, Y.; Matsuzaki, M. Altered intracellular Ca2+ handling in heart failure. J Clin Invest 2005, 115, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muth, J.N.; Bodi, I.; Lewis, W.; Varadi, G.; Schwartz, A. A Ca(2+)-dependent transgenic model of cardiac hypertrophy: A role for protein kinase Calpha. Circulation 2001, 103, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamaguchi, N.; Takahashi, N.; Xu, L.; Smithies, O.; Meissner, G. Early cardiac hypertrophy in mice with impaired calmodulin regulation of cardiac muscle Ca release channel. J Clin Invest 2007, 117, 1344–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yano, M.; Uchinoumi, H.; Hino, A.; Suetomi, T.; Ono, M.; Tateishi, H.; Oda, T.; Okuda, S.; Doi, M.; et al. Defective calmodulin binding to the cardiac ryanodine receptor plays a key role in CPVT-associated channel dysfunction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2010, 394, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Yano, M.; Hino, A.; Suetomi, T.; Xu, X.; Susa, T.; Uchinoumi, H.; Tateishi, H.; Oda, T.; Okuda, S.; et al. Dissociation of calmodulin from cardiac ryanodine receptor causes aberrant Ca(2+) release in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 2010, 87, 609–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Koninck, P.; Schulman, H. Sensitivity of CaM kinase II to the frequency of Ca2+ oscillations. Science 1998, 279, 227–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bers, D.M. Ca(2)(+)-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulation of cardiac excitation-transcription coupling. Heart Rhythm 2011, 8, 1101–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bers, D.M.; Grandi, E. Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II regulation of cardiac ion channels. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2009, 54, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takimoto, E.; Kass, D.A. Role of oxidative stress in cardiac hypertrophy and remodeling. Hypertension 2007, 49, 241–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabri, A.; Hughie, H.H.; Lucchesi, P.A. Regulation of hypertrophic and apoptotic signaling pathways by reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. Antioxid Redox Signal 2003, 5, 731–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitter, J.G.; Maechler, P.; Wollheim, C.B.; Spat, A. Mitochondria respond to Ca2+ already in the submicromolar range: correlation with redox state. Cell Calcium 2002, 31, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, A.V.; Margreiter, R.; Ausserlechner, M.J.; Hagenbuchner, J. The Complex Interplay between Mitochondria, ROS and Entire Cellular Metabolism. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves-Figueiredo, H.; Silva-Platas, C.; Estrada, M.; Oropeza-Almazan, Y.; Ramos-Gonzalez, M.; Bernal-Ramirez, J.; Vazquez-Garza, E.; Tellez, A.; Salazar-Ramirez, F.; Mendez-Fernandez, A.; et al. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Uniporter-Dependent Energetic Dysfunction Drives Hypertrophy in Heart Failure. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2024, 9, 496–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, S.; Terentyeva, R.; Kim, T.Y.; Bronk, P.; Clements, R.T.; J, O.U.; Csordas, G.; Choi, B.R.; Terentyev, D. Pharmacological Modulation of Mitochondrial Ca(2+) Content Regulates Sarcoplasmic Reticulum Ca(2+) Release via Oxidation of the Ryanodine Receptor by Mitochondria-Derived Reactive Oxygen Species. Frontiers in physiology 2018, 9, 1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaglia, T.; Ceriotti, P.; Campo, A.; Borile, G.; Armani, A.; Carullo, P.; Prando, V.; Coppini, R.; Vida, V.; Stolen, T.O.; et al. Content of mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU) in cardiomyocytes is regulated by microRNA-1 in physiologic and pathologic hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E9006–E9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson, J.R.; Joiner, M.L.; Guan, X.; Kutschke, W.; Yang, J.; Oddis, C.V.; Bartlett, R.K.; Lowe, J.S.; O'Donnell, S.E.; Aykin-Burns, N.; et al. A dynamic pathway for calcium-independent activation of CaMKII by methionine oxidation. Cell 2008, 133, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.Z.; Wang, S.Q.; Chakir, K.; Yang, D.; Zhang, T.; Brown, J.H.; Devic, E.; Kobilka, B.K.; Cheng, H.; Xiao, R.P. Linkage of beta1-adrenergic stimulation to apoptotic heart cell death through protein kinase A-independent activation of Ca2+/calmodulin kinase II. J Clin Invest 2003, 111, 617–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, W.; Woo, A.Y.; Yang, D.; Cheng, H.; Crow, M.T.; Xiao, R.P. Activation of CaMKIIdeltaC is a common intermediate of diverse death stimuli-induced heart muscle cell apoptosis. J Biol Chem 2007, 282, 10833–10839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, M.; Cheng, H.; Zhu, W.; Cao, C.M.; Xiao, R.P. Cardioprotection by CaMKII-deltaB is mediated by phosphorylation of heat shock factor 1 and subsequent expression of inducible heat shock protein 70. Circ Res 2010, 106, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Little, G.H.; Saw, A.; Bai, Y.; Dow, J.; Marjoram, P.; Simkhovich, B.; Leeka, J.; Kedes, L.; Kloner, R.A.; Poizat, C. Critical role of nuclear calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase IIdeltaB in cardiomyocyte survival in cardiomyopathy. J Biol Chem 2009, 284, 24857–24868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).