1. Introduction

Variegated plants represent a significant part of the ornamental plant market due to their aesthetic appearance [

1]. This variegation results from a partial or total deficit of chlorophyll in certain regions of the plant, leading to colorations ranging from yellowish to whitish. The presence of leaves and/or stems with a different color or coloring patterns than those typical of the original species gives variegated plants a greater visual beauty and ornamental value, making them highly valued among both, amateur and professional gardeners or floriculturists [

2,

3]. Therefore, although these plants tend to be less vigorous than the non-variegated ones, due to their lower amount of chlorophyll, which affects their photosynthetic capacity [

4], it is not surprising that commercial nurseries work intensively to obtain plants with new colorations or patterns to annually introduce into the market.

Nowadays, the presence of a wide range of variegated plants, including popular ones like pothos, alocasias and monsteras, reflects their significance in gardening and landscaping. Also, certain cactus cultivars developed from

Gymnocalycium mihanovichii (Frič and Gürke) Britton and Rose, are commercially important due to their diverse coloration [

5] (

Figure 1). Many of these variants are clonally propagated through grafting [

6,

7], although the success of this process can be influenced by the ability of the parent plants to produce shoots with the expected patterns of coloration or color percentage.

The grafting technique is widely used in the mass propagation of cacti due to its advantages against plants grown from their roots [

8]. Grafting allows: (i) enhanced plant development, (ii) increased shoot production, (iii) accelerate blooming, reducing the time between generations and (iv) intensify flowering (i.e. more flowers per season) [

9]. Additionally, rootstocks are usually more vigorous and resistant to humidity, pests and diseases, minimizing losses from rot and simplifying their cultivation [

8,

9].

Nevertheless, grafting may alters the natural morphology of the plants, leading to an atypical appearance that may not appeal to collectors, who prefer visually natural plants capable of growing on their own roots. Completely achlorophyllous plants must remain grafted due to their inability to photosynthesize [

4,

10], so they are generally unpopular among collectors. This situation underscores the need for protocols to optimize the production processes of cacti with specific percentage of colorations that are able to develop on their own roots. Such protocols could significantly benefit large-scale cactus producers by improving efficiency and allowing for the selection of plants with desired variegation levels for the collector market.

In this context,

in vitro cultivation can play a determinant role, since the regenerative capacity of different structures (mainly areoles) has been observed in a range of cacti species [

7,

11,

12,

13]. However, most of these studies have been focused on edible species that have interest on food industry, such as pitahaya and prickly pear [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Therefore, there is a lack of information regarding many ornamental species that could have a significant impact on the market, in particular when propagating variegated individuals or those with particular color patterns, as in most cases the cellular mechanisms that cause them are unknown [

21].

Thus, the study focuses on the

in vitro response of

Gymnocalycium plants with varying degrees of variegation (

Figure 2). Therefore, the objective of the experiment is to establish an efficient protocol for

in vitro propagation of

Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy plants with varying degrees of variegation. This will be achieved through evaluating the organogenic response and

in vitro behavior of diverse explants (apical, central disc, hypocotyl, and epicotyl) from plants of different sizes (small, medium, and large) under three previously tested plant growth regulators (PGRs) used on chlorophyll-containing plants of the same cultivar [

22].

The aim is to determine the effect of these plant growth regulators on variegated plants and the relationship between the initial plants' variegation proportion and the productivity of shoots with varying degrees of variegation. This information could be highly relevant in a commercial context, whether it improves graft propagation efficiency or optimizes the production of partially variegated plants for cactus collectors. Furthermore, the results could be applicable to other cactus species that may attract interest from consumers and collectors.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Material and Disinfection

Plants were obtained by

in vitro sowing of

Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy seeds, kindly donated by Cactusloft OE (Cullera, Valencia, Spain). This commercial hybrid developed by Cactusloft O.E. (Cullera, Valencia, Spain) originated from controlled crosses between

Gymnocalycium mihanovichii and

Gymnocalycium fiedrichi (Werdermann) Pažout, resulting in progenies with diverse morphologies and colorations due to their broad genetic background. This circumstance gives

Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy an enormous potential from a commercial point of view, given that plants with different degrees of variegation can be obtained and selected, and color variants with different morphologies can also be identified [

22] (

Figure 2). For their disinfection, seeds were treated under aseptic conditions in a laminar flow cabinet (model AH-100, Telstar, Terrassa, Spain) for 1 min in 70% ethanol (v/v), continued by 25 min in 15% domestic bleach solution (v/v; 4% sodium hypochlorite) supplemented with 0.08% of the surfactant Tween-20 (v/v). Finally, seeds were rinsed 3 times in distilled sterilized water before sowing.

3.2. In Vitro Establishment and Culture Conditions

Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal media (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, Netherlands)[

56] at half strength (1/2MS, 2.2 g L

-1) supplemented with 15 g L

-1 of sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, Missouri, USA) and 7 g L

-1 of bacteriological agar (Duchefa Biochemie, Haarlem, Netherlands) was used as a sowing media. pH was adjusted to 5.7 before autoclaving at 120ºC for 20 min [

57]. Disinfected seeds were sown into sterile plastic disposable Petri dishes containing 20 seeds each. Seedlings developed under

in vitro conditions inside a growth room at 26±2ºC on shelves with a 16 h light / 8 h dark photoperiod and photosynthetic photon flux of 50 molm

-2 s

-1 for 8 months. Seedlings were subcultured monthly to a fresh media.

3.3. Induction and Tissue Culture Conditions

With the aim of assessing the morphogenic potential of variegated seedlings of

Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy with different degree of coloration, three specific concentration of cytokinins (Duchefa Biochemie Company, RV Haarlem, The Netherlands) that generated responses in chlorophyllous plants in previous works [

22] were studied: 6-Benzylaminopurine 8µM (BAP8), Kinetin 4 µM (KIN4) and Thidiazuron 1µM (TDZ1).

The explants were placed on a culture 1/2MS media (2.2 g L-1), supplemented with sucrose (15 g L-1), agar (7 g L-1) and each of the three cytokinins (BAP8, KIN4 and TDZ1), adjusting the pH to 5.7, to activate their induction. Besides, a control group in absence of PGRs was included for each plant size and each type of explant. Furthermore, the explants were placed maximizing the contact between the sectioned tissue and the culture medium. The culture in the induction medium lasted for two months. A subculture was performed after the first four weeks to ensure that the hormone concentration was constant throughout the induction period. After the induction period, explants were subcultured to the initial basal 1/2MS media at pH 5.7 in absence of PGRs.

3.4. Experimental Design

After an 8 month period of

in vitro growth, a total of 180 plants were selected and classified depending on their initial size (

Table 11). From medium and large-sized plants, two types of explants were obtained: apical and central disc, that were in turn sectioned into two halves, i.e. four explants were obtained for each medium or large-sized plant. From small-sized plants, epicotyl and hypocotyl were obtained, through cutting transversally the seedlings into two parts. Roots were completely removed in all cases. Therefore, four different types of explants were evaluated in this study: apical explants, central disc explants, epicotyls and hypocotyls (

Table 11).

Plants were visually classified into four groups depending on the proportion of coloration observed (25%, 50%, 75% and 100%). Considering their initial sizes, plants were randomly distributed in each group before obtaining the explants (

Table 11). Fully colored plants were only included in the small-sized group, as their lack of chlorophyll provoked sizes < 8 mm of diameter. Furthermore, plants fully covered by chlorophyll (i.e. 0% color) were also included as a different control groups (

Figure 9): (a) on one hand, medium-sized plants subjected to the presence of PGRs and, (b) on the other hand, plants of all evaluated sizes (small, medium and large-sized) in absence of PGRs (

Table 11).

A total of five 574 explants from plants with different color percentages, including 214 of each apical explants and central disc explants and 73 of each epicotyl and hipocotyl explants, were evaluated during the experiment (

Table 11). The explants were analyzed considering the degree of variegation and size of the original plant for each of the hormonal treatments and the control group. They were distributed in groups of four explants per Petri dish for their evaluation.

The percentage of activated explants was calculated as the number of explants that showed some type of response during the assay, either organogenic or callogenic, relative to the total number of explants (

Table 1). The appearance of shoots and the formation of calluses were noticed monthly for 5 months, only from those explants that responded to the treatments. Considering the different number of areolas present in each one of the starting explants (

Table 4), the results were interpreted taking into account both: (i) productivity (i.e. total number of shoots per explant) and (ii) efficiency (i.e. ratio of the activated areoles with respect to the total of areoles of each explant). The emission of roots was also recorded in terms of percentage during the first three months.

3.4.1. Areole Evaluation

Using a magnifying glass (Kern OZO, 551), all activated areolas from colored plants were visually classified into three groups based on their coloration: green areolas "G" (where both the mamilla and areola were completely green), mixed areolas "M" (showing a combination of chlorophyllous and variegated tissue in both the mamilla and areola), and colored areolas "C" (where both the mamilla and areola were fully colored) (

Figure 7). Chlorophyllous plants from the control groups were not included in this evaluation, since all the sprouts obtained in previous trials were totally green [

22].

Subsequently, the obtained shoots were counted considering the percentage of coloration of the source plants and classified into four groups based on their final coloration: shoots completely green (without variegation, group "S0"), shoots with a coloration percentage below 50% (group "S1"), shoots with a coloration percentage above 50% (group "S2"), and completely colored shoots (without chlorophyllous tissue, group "S3") (

Figure 10). The relationships between the percentage of coloration of the activated areolas and the coloration of the shoots obtained based on the percentage of color of the initial plants, as well as the coloration of the shoots obtained based on the coloration of the activated areolas, were evaluated.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

In order to analize our data sets, multivariate ANOVA analysis was performed to check the effect of the different factors at a level of p < 0.05. The software used for performing this ANOVA analysis was Statgraphics Centurion XVIII (Statgraphics Technologies Inc., The Plains, Virginia, USA). The presence of the three different hormones (BAP8, KIN4 and TDZ1) in the culture media, the relevance of the initial size (small, medium and large-sized plants), the presence of diverse degree of variegation in the initial plants and the activation capacity of the various explants (apical explants, central disc explants, epicotyls and hipocotyls) were analized only in those explants that responded to some treatment.

Means differing significantly were compared using the Student-Newman-Keuls test with a probability level of the 5%. Transformation of the data was previously made to normalize the dataset using the following formulas:

- -

For numerical and absolute data, including shoot emission, callus production and averages.

- -

For percentages and efficiency values, including rooting capacity.

The linear combinations between the initial color of the plants, the color of the activated areolas, the color of the shoots obtained and the hormones used in the trial were studied through canonical correlation analysis, establishing a confidence level of 95%. Statgraphics Centurion XVIII (Statgraphics Technologies Inc., The Plains, Virginia, USA) was also used for these analysis.

4. Conclusions

In this work, a specific micropropagation protocol focused on obtaining shoots with varying degrees of variegation in Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy plants has been successfully optimized. The use of central disc explants in the presence of TDZ1 in the culture medium yielded the best results in terms of initial explant activation, shoot productivity and efficiency related to areolar activation per explant. Furthermore, it was observed that the coloration percentage of the starting plants (excluding completely achlorophyllous plants) did not limit the response capacity of the evaluated explants. Hence, a strong correlation exists between the initial variegation percentage of the plants and the type of activated areola.

Additionally, the type of activated areola correlated with the color percentage of the obtained shoots, highlighting a situation of somatic mosaicism in the areolas that determines the variegation percentage of the final shoot. These results allow for adjusting and optimizing propagation protocols to obtain plants with different variegation proportions based on commercial objectives. So that, for obtaining fully variegated shoots, colored areolas would be selected, while for obtaining shoots with partial variegation, explants carrying mixed areolas would be chosen.

Therefore, this protocol is extremely valuable from a commercial standpoint as it enables control and prediction of the coloration of the obtained plants, thus allowing them to be directed towards high-impact markets (wholesale or collector). Consequently, achieving greater efficiency and resource optimization in commercial plant production processes would be possible.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.P., C.C.-O., V.M.G.-S. and A.R.-B; methodology, C.C.-O., A.F. and A.R.-B; software, C.G.-R. and A.B.-G; validation, C.C.-O., A.F. and A.R.-B; formal analysis, C.C.-O. and C.G.-R.; investigation, C.C.-O., V.M.G.-S., A.B.-G. and A.R.-B; resources, A.F. and A.R.-B; data curation, C.C.-O., V.M.G.-S; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.-O., V.M.G.-S. and A.R.-B; writing—review and editing, C.C.-O., C.G.-R., A.F., B.P. and A.R.-B.; visualization, A.R.-B; supervision, A.R.-B; funding acquisition, A.F. and A.R.-B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Commercial selections of Gymnocalycium mihanovichii with different colorations and color distribution patterns.

Figure 1.

Commercial selections of Gymnocalycium mihanovichii with different colorations and color distribution patterns.

Figure 2.

Morphological heterogeneity observed in one-year-old Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy shoots obtained in vitro and subsequently acclimatized. (a, b) Expected morphologies within the usual range of variation of the cultivar. (c, d) Unexpected morphologies obtained, monstrous (c) and caespitose forms (d). (e) Variegated plants with different degrees of variegation.

Figure 2.

Morphological heterogeneity observed in one-year-old Gymnocalycium cv. Fancy shoots obtained in vitro and subsequently acclimatized. (a, b) Expected morphologies within the usual range of variation of the cultivar. (c, d) Unexpected morphologies obtained, monstrous (c) and caespitose forms (d). (e) Variegated plants with different degrees of variegation.

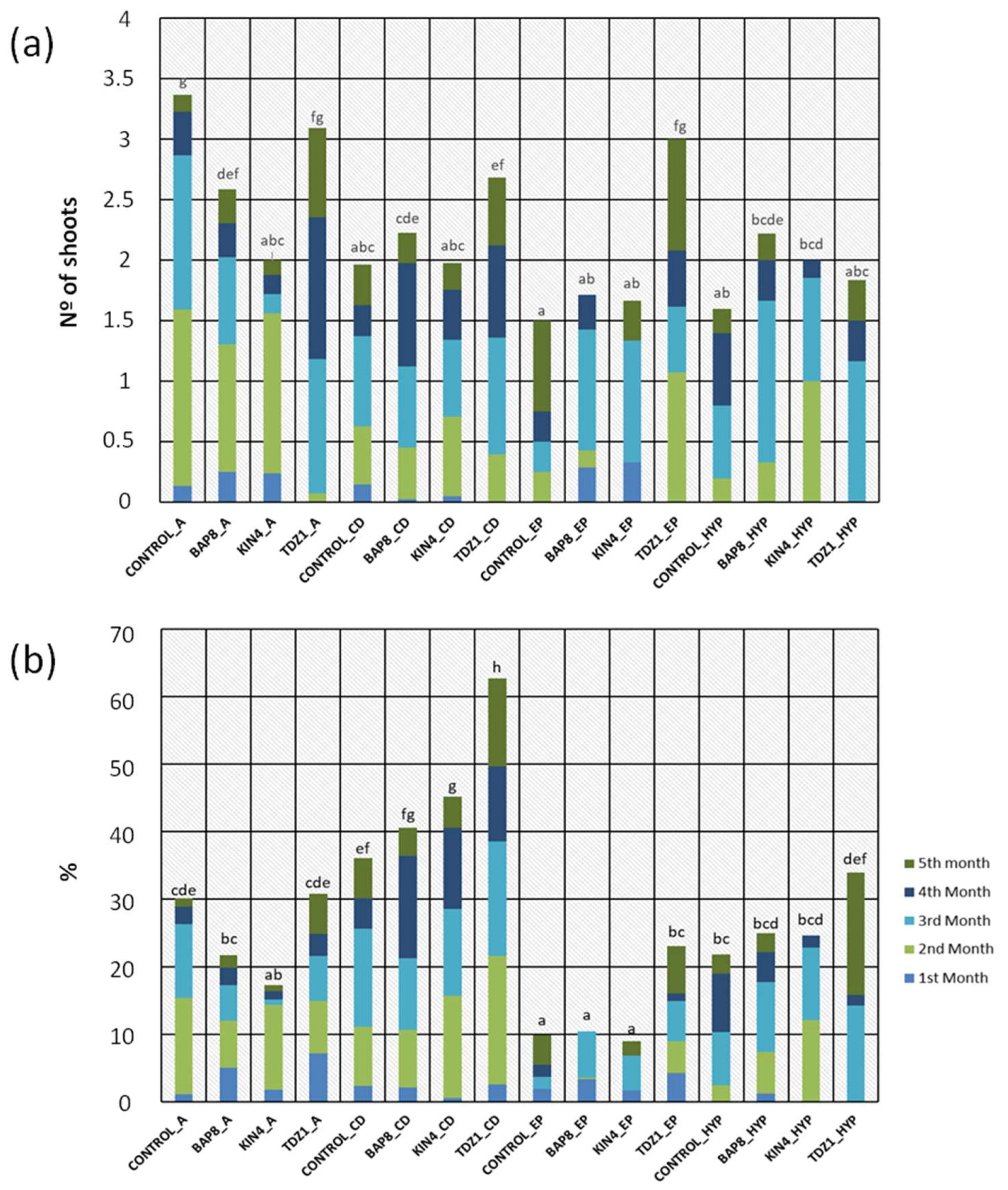

Figure 3.

(a) Average number of shoots obtained for each "Hormone + Explant Type" combination during each month of cultivation. (b) Average percentage of areoles activated by each "Hormone + Explant Type" combination during each month of cultivation. Hormone: CONTROL (control group), BAP8 (6-Benzylaminopurine), KIN4 (Kinetin) and TDZ1 (Thidiazuron). Numbers following the conditions indicate the hormonal concentration (1, 4 or 8 µM). Capital letters indicate the explants used in each combination: A (apical), CD (central discs), EP (epicotyl) and HYP (hypocotyl). Letters (a, b, c, d, e, f) above the bars represent significant differences based on sample means at the fifth month of evaluation, for p = 0.05 according to the Student–Newman–Keuls test.

Figure 3.

(a) Average number of shoots obtained for each "Hormone + Explant Type" combination during each month of cultivation. (b) Average percentage of areoles activated by each "Hormone + Explant Type" combination during each month of cultivation. Hormone: CONTROL (control group), BAP8 (6-Benzylaminopurine), KIN4 (Kinetin) and TDZ1 (Thidiazuron). Numbers following the conditions indicate the hormonal concentration (1, 4 or 8 µM). Capital letters indicate the explants used in each combination: A (apical), CD (central discs), EP (epicotyl) and HYP (hypocotyl). Letters (a, b, c, d, e, f) above the bars represent significant differences based on sample means at the fifth month of evaluation, for p = 0.05 according to the Student–Newman–Keuls test.

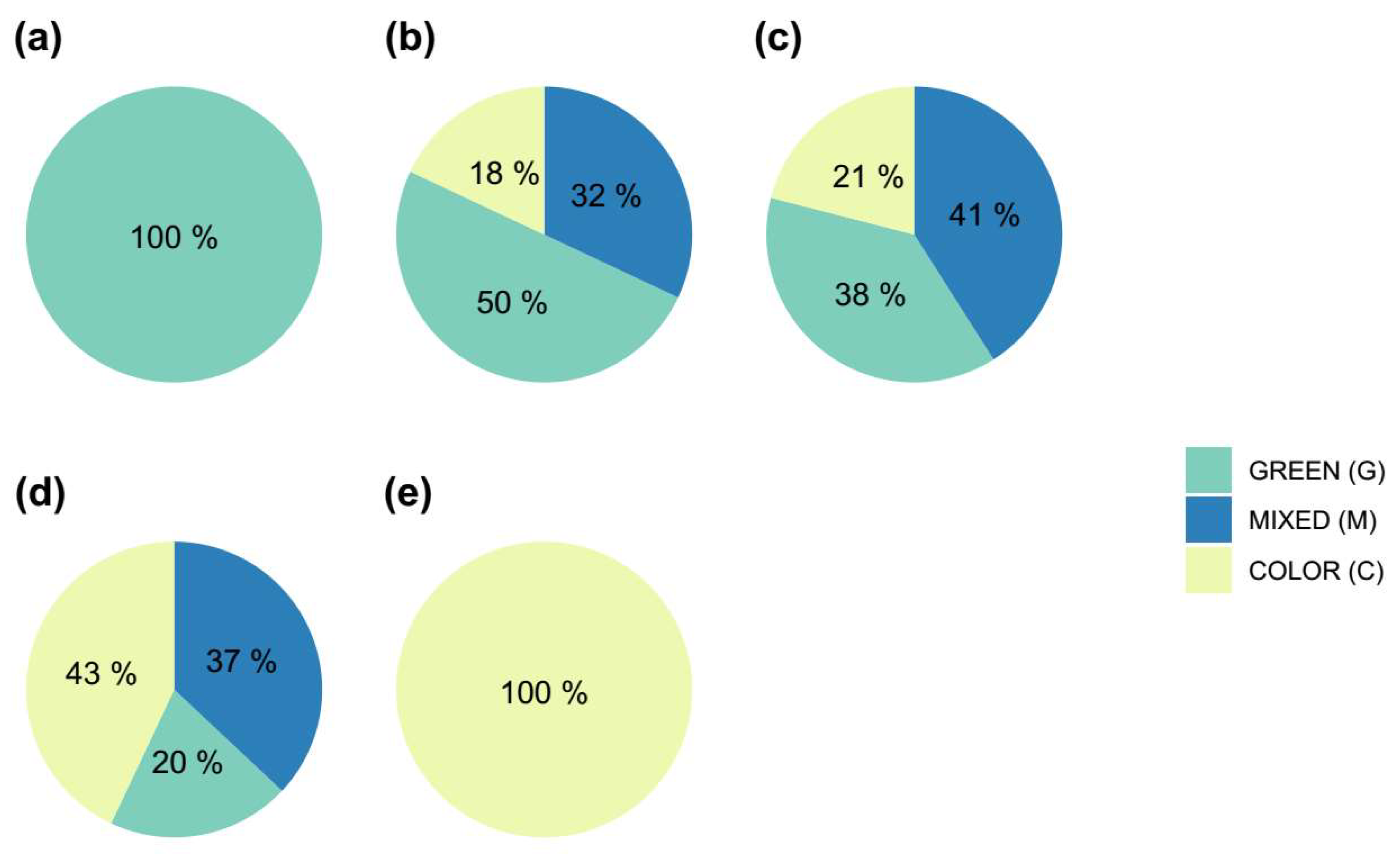

Figure 4.

Percentage of activated areoles of each type (green = G, mixed = M or color = C) as a function of the initial coloration of the plants. (a) Green plants without variegation; (b) plants with 25% of variegation (c) plants with 50% of variegation, (d) plants with 75% of variegation and (e) plants completely colored (100% variegation).

Figure 4.

Percentage of activated areoles of each type (green = G, mixed = M or color = C) as a function of the initial coloration of the plants. (a) Green plants without variegation; (b) plants with 25% of variegation (c) plants with 50% of variegation, (d) plants with 75% of variegation and (e) plants completely colored (100% variegation).

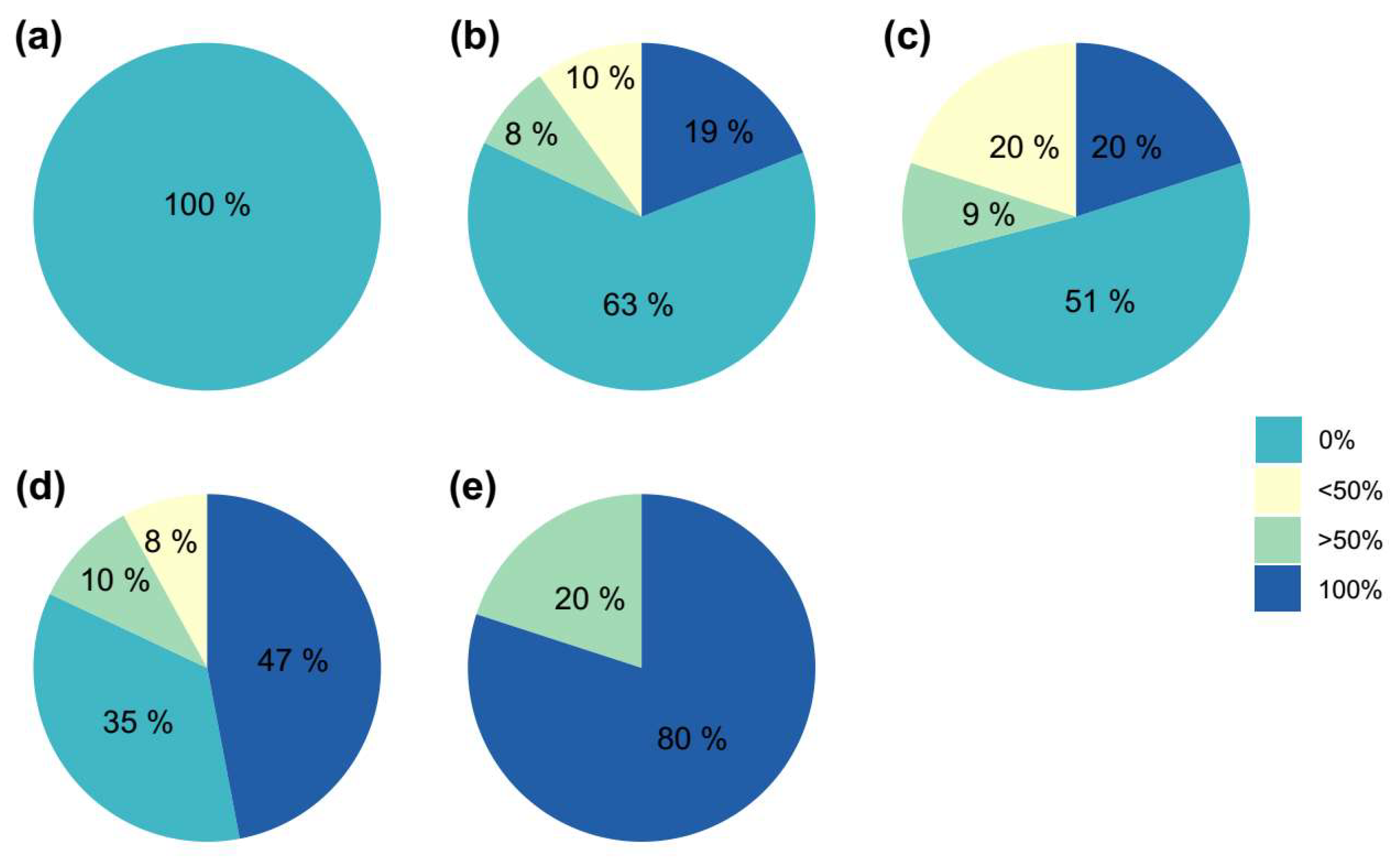

Figure 5.

Percentage of obtained shoots with different degrees of variegation (0%, less than 50%, more than 50% and totally variegated, 100%) with respect to the percentage of variegation of the initial plants. (a) Green plants without variegation; (b) plants with 25% of variegation (c) plants with 50% of variegation, (d) plants with 75% of variegation and (e) plants completely colored (100% variegation).

Figure 5.

Percentage of obtained shoots with different degrees of variegation (0%, less than 50%, more than 50% and totally variegated, 100%) with respect to the percentage of variegation of the initial plants. (a) Green plants without variegation; (b) plants with 25% of variegation (c) plants with 50% of variegation, (d) plants with 75% of variegation and (e) plants completely colored (100% variegation).

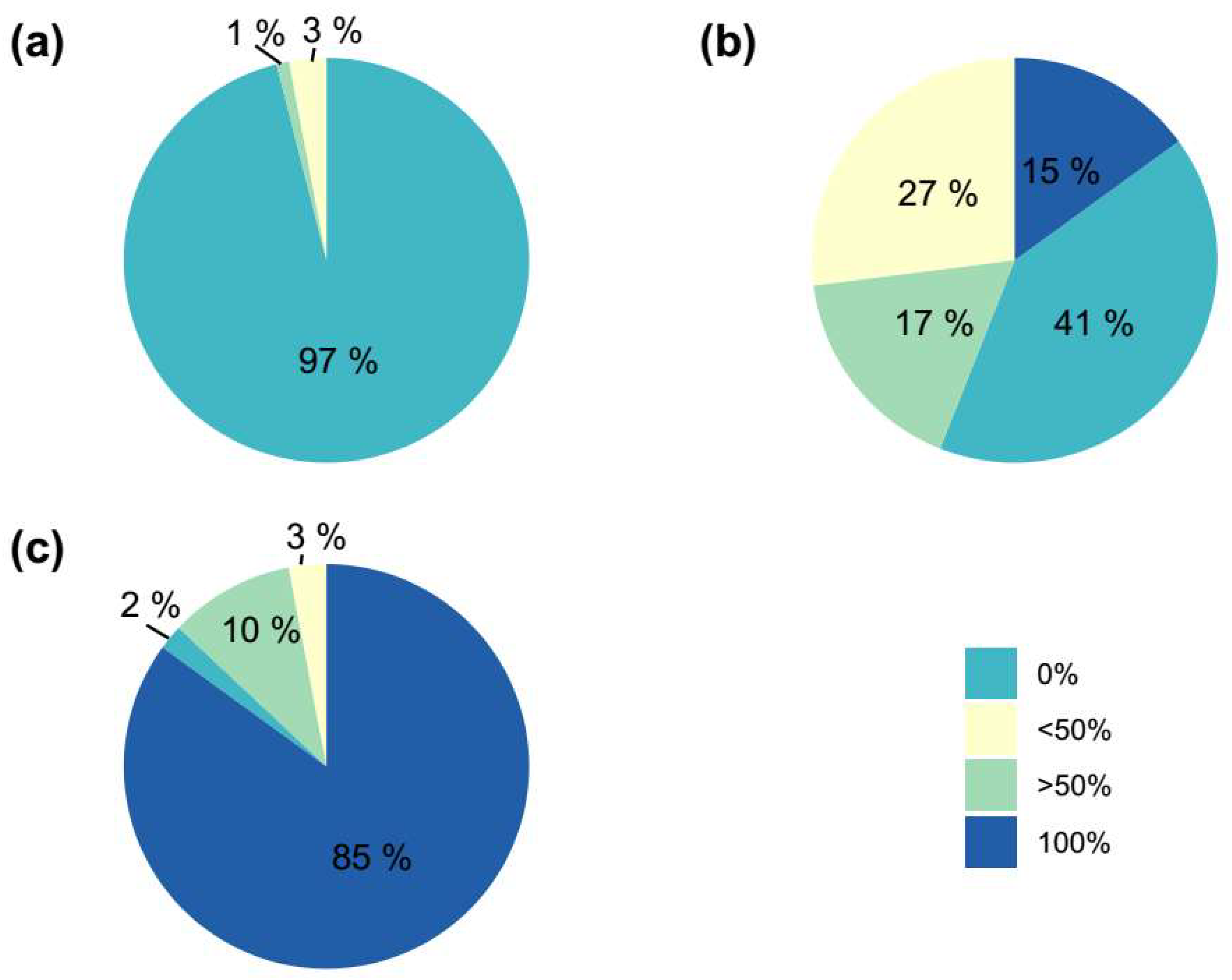

Figure 6.

Percentage of shoots obtained with different degrees of variegation (0%, less than 50%, more than 50% and totally variegated, 100%) with respect to the coloration of the starting areoles ((a) - Green; (b) - Mixed; (c) - Color).

Figure 6.

Percentage of shoots obtained with different degrees of variegation (0%, less than 50%, more than 50% and totally variegated, 100%) with respect to the coloration of the starting areoles ((a) - Green; (b) - Mixed; (c) - Color).

Figure 7.

Classification of the types of areolas according to their coloration. (a) View of the apical part of the plant. (b) Transverse section of a variegated plant. Letters indicates: “G”, green areolas (where both the mamilla and areola were completely green); “M”, mixed areolas (showing a combination of chlorophyllous and variegated tissue in both the mamilla and areola); and “C”, colored areolas (where both the mamilla and areola were fully colored).

Figure 7.

Classification of the types of areolas according to their coloration. (a) View of the apical part of the plant. (b) Transverse section of a variegated plant. Letters indicates: “G”, green areolas (where both the mamilla and areola were completely green); “M”, mixed areolas (showing a combination of chlorophyllous and variegated tissue in both the mamilla and areola); and “C”, colored areolas (where both the mamilla and areola were fully colored).

Figure 8.

Varied shoots with different colorations and different color patterns observed in the trial.

Figure 8.

Varied shoots with different colorations and different color patterns observed in the trial.

Figure 9.

Initial plant variegation percentage classification system: (a) completely chlorophyll plant (no variegation, 0%), (b) plants with more chlorophyll than nonchlorophyll tissue (25% variegation), (c) plants with equal proportion of chlorophyll and nonchlorophyll tissue (50% variegation), (d) plants with more than 50% nonchlorophyll tissue (75% variegation), and (e) plants with completely nonchlorophyll tissue (100% variegation). White bars = 10 mm.

Figure 9.

Initial plant variegation percentage classification system: (a) completely chlorophyll plant (no variegation, 0%), (b) plants with more chlorophyll than nonchlorophyll tissue (25% variegation), (c) plants with equal proportion of chlorophyll and nonchlorophyll tissue (50% variegation), (d) plants with more than 50% nonchlorophyll tissue (75% variegation), and (e) plants with completely nonchlorophyll tissue (100% variegation). White bars = 10 mm.

Figure 10.

Grading system of the obtained shoots according to their final coloration. (a) completely green shoots (without variegation, group "S0"); (b) shoots with a percentage of coloration lower than 50% (group "S1"); (c) shoots with a percentage of coloration higher than 50% (group "S2"), and (d) completely colored shoots (without chlorophyll tissue, group "S3").

Figure 10.

Grading system of the obtained shoots according to their final coloration. (a) completely green shoots (without variegation, group "S0"); (b) shoots with a percentage of coloration lower than 50% (group "S1"); (c) shoots with a percentage of coloration higher than 50% (group "S2"), and (d) completely colored shoots (without chlorophyll tissue, group "S3").

Table 1.

Percentage of activated explants as a function of evaluated factors at the 5th month.

Table 1.

Percentage of activated explants as a function of evaluated factors at the 5th month.

| Factor |

Total Number of Explants |

Activated Explants |

% of Response (1)

|

| Treatment (2)

|

|

|

|

| BAP8 |

152 |

92 |

60.53 a |

| KIN4 |

150 |

76 |

50.67 a |

| TDZ1 |

148 |

123 |

83.11 b |

| CONTROL |

124 |

58 |

46.77 a |

| Plant Size |

|

|

|

| Large |

96 |

67 |

69.79 b |

| Medium |

332 |

228 |

68.67 b |

| Small |

146 |

54 |

36.99 a |

| % of Color |

|

|

|

| 0 |

220 |

136 |

61.82 b |

| 25 |

110 |

74 |

67.27 b |

| 50 |

60 |

41 |

68.33 b |

| 75 |

156 |

95 |

60.90 b |

| 100 |

28 |

3 |

10.71 a |

| Type of Explant |

|

|

| Apical |

214 |

137 |

64.02 b |

| Central Disc |

214 |

158 |

73.83 c |

| Epicotyl |

73 |

27 |

36.99 a |

| Hypocotyl |

73 |

27 |

36.99 a |

| Total |

574 |

349 |

60.8 |

Table 2.

Average number of calli with their standard errors obtained monthly per factor and condition.

Table 2.

Average number of calli with their standard errors obtained monthly per factor and condition.

| Factors |

Cases |

Induction Period in Presence of PGRs (1)

|

Development Period in Absence of PGRs |

| 1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

4th Month |

|

p-Value |

Average (4)

|

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

| Treatment (2)

|

|

0.000 * |

|

0.000 * |

|

0.000 * |

|

0.000 * |

|

| BAP8 |

92 |

|

0.28±0.10 b |

|

0.17±0.06 a |

|

0.03±0.02 a |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

| KIN4 |

76 |

|

0.01±0.01 a |

|

0.03±0.02 a |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

|

0.07±0.03 a |

| TDZ1 |

123 |

|

0.55±0.09 c |

|

1.12±0.12 b |

|

0.89±0.12 b |

|

0.41±0.08 b |

| CONTROL |

58 |

|

0.02±0.02 a |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

| Plant Size (3)

|

|

0.949 |

|

0.041 * |

|

0.504 |

|

0.37 |

|

| Large |

67 |

|

0.36±0.13 a |

|

0.48±0.11 ab |

|

0.19±0.07 a |

|

0.17±0.05 b |

| Medium |

228 |

|

0.25±0.05 a |

|

0.50±0.07 b |

|

0.39±0.07 a |

|

0.21±0.04 b |

| Small |

54 |

|

0.26±0.08 a |

|

0.17±0.07 a |

|

0.20±0.09 a |

|

0.07±0.07 a |

| % of Color |

|

0.12 |

|

0.045 * |

|

0.045 * |

|

0.049 * |

|

| 0 |

136 |

|

0.23±0.06 a |

|

0.34±0.08 a |

|

0.33±0.08 ab |

|

0.24±0.06 b |

| 25 |

74 |

|

0.26±0.07 ab |

|

0.69±0.12 b |

|

0.57±0.15 b |

|

0.22±0.08 ab |

| 50 |

41 |

|

0.61±0.22 b |

|

0.51±0.15 ab |

|

0.07±0.04 a |

|

0.02±0.02 a |

| 75 |

95 |

|

0.21±0.06 a |

|

0.39±0.09 a |

|

0.22±0.06 a |

|

0.05±0.04 a |

| 100 |

3 |

|

0.33±0.33 ab |

|

0.33±0.33 ab |

|

0.33±0.33 ab |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

| Type of Explant |

|

0.000 * |

|

0.000 * |

|

0.001 * |

|

0.043 * |

|

| Apical |

137 |

|

0.55±0.09 b |

|

0.77±0.10 b |

|

0.55±0.10 b |

|

0.26±0.07 c |

| Central Disc |

158 |

|

0.04±0.02 a |

|

0.26±0.05 a |

|

0.17±0.05 a |

|

0.10±0.03 a |

| Epicotyl |

27 |

|

0.48±0.15 b |

|

0.19±0.08 a |

|

0.37±0.17 ab |

|

0.15±0.15 ab |

| Hypocotyl |

27 |

|

0.04±0.04 a |

|

0.15±0.12 a |

|

0.04±0.04 a |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

| Total |

349 |

|

0.28±0.04 |

|

0.45±0.05 |

|

0.32±0.05 |

|

0.16±0.03 |

Table 3.

Average number of shoots (±SE) obtained monthly per factor and condition.

Table 3.

Average number of shoots (±SE) obtained monthly per factor and condition.

| Factors |

Cases |

Induction Period in Presence of PGRs (1)

|

Development Period in Absence of PGRs (1)

|

| 1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

4th Month |

5th Month |

|

p -Value (4)

|

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

| Treatment (2)

|

|

0.015 * |

|

0.000 * |

|

0.142 |

|

0.433 |

|

0.000 * |

|

| BAP8 |

92 |

|

0.13±0.04 b |

|

0.77±0.13 b |

|

1.55±0.15 ab |

|

2.09±0.15 a |

|

2.33±0.15 a |

| KIN4 |

76 |

|

0.12±0.06 b |

|

1.00±0.12 b |

|

1.51±0.12 ab |

|

1.80±0.12 a |

|

1.97±0.11 a |

| TDZ1 |

123 |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

|

0.31±0.07 a |

|

1.30±0.11 a |

|

2.19±0.12 a |

|

2.85±0.13 b |

| CONTROL |

58 |

|

0.12±0.07 b |

|

0.93±0.21 b |

|

1.83±0.26 b |

|

2.16±0.26 a |

|

2.43±0.25 a |

| Explant Size (3)

|

|

0.589 |

|

0.693 |

|

0.529 |

|

0.167 |

|

0.199 |

|

| Large |

67 |

|

0.13±0.06 a |

|

0.79±0.07 a |

|

1.69±0.21 a |

|

2.21±0.21 a |

|

2.58±0.20 a |

| Medium |

228 |

|

0.07±0.02 a |

|

0.68±0.07 a |

|

1.47±0.09 a |

|

2.11±0.09 a |

|

2.49±0.10 a |

| Small |

54 |

|

0.07±0.04 a |

|

0.56±0.12 a |

|

1.41±0.14 a |

|

1.74±0.16 a |

|

2.13±0.16 a |

| % of Color |

|

0.196 |

|

0.149 |

|

0.042 * |

|

0.622 |

|

0.792 |

|

| 0 |

136 |

|

0.12±0.04 b |

|

0.73±0.10 a |

|

1.40±0.14 a |

|

2.14±0.14 a |

|

2.46±0.13 a |

| 25 |

74 |

|

0.00±0.00 a |

|

0.57±0.13 a |

|

1.34±0.15 a |

|

2.04±0.15 a |

|

2.42±0.18 a |

| 50 |

41 |

|

0.07±0.04 ab |

|

0.98±0.26 a |

|

2.05±0.25 b |

|

2.22±0.23 a |

|

2.66±0.25 a |

| 75 |

95 |

|

0.10±0.05 ab |

|

0.56±0.09 a |

|

1.52±0.12 ab |

|

1.92±0.14 a |

|

2.36±0.12 a |

| 100 |

3 |

|

0.00±0.00 ab |

|

1.67±0.88 a |

|

2.00±0.58 ab |

|

2.67±0.88 a |

|

3.00±1.00 a |

| Type of Explant |

|

0.081 |

|

0.047 * |

|

0.086 |

|

0.013 * |

|

0.005 * |

|

| Apical |

137 |

|

0.13±0.04 b |

|

0.91±0.13 b |

|

1.77±0.15 b |

|

2.39±0.14 b |

|

2.80±0.15 b |

| Central Disc |

158 |

|

0.04±0.02 a |

|

0.53±0.07 a |

|

1.30±0.10 a |

|

1.91±0.10 a |

|

2.26±0.10 a |

| Epicotyl |

27 |

|

0.11±0.08 ab |

|

0.70±0.18 ab |

|

1.37±0.19 ab |

|

1.70±0.24 a |

|

2.30±0.27 ab |

| Hypocotyl |

27 |

|

0.00±0.00 ab |

|

0.41±0.15 a |

|

1.44±0.22 ab |

|

1.78±0.22 ab |

|

1.96±0.19 a |

| TOTAL |

349 |

|

0.08±0.02 |

|

0.69±0.06 |

|

1.50±0.08 |

|

2.07±0.08 |

|

2.45±0.08 |

Table 4.

Average number of areoles per explant according to initial plant size and explant type.

Table 4.

Average number of areoles per explant according to initial plant size and explant type.

| Factor |

Cases |

Average (1)

|

| Plant Size |

|

| Large |

96 |

9.30 ± 0.43 a |

| Medium |

332 |

9.37 ± 0.27 a |

| Small |

146 |

10.21 ± 0.54 a |

| Type of Explant |

|

| Apical |

214 |

13.15 ± 0.25 b |

| Central Disc |

214 |

5.51 ± 0.13 a |

| Epicotyl |

73 |

15.30 ± 0.51 b |

| Hypocotyl |

73 |

5.12 ± 0.43 a |

Table 5.

Average number of the percentage of activated areoles with their standard errors obtained monthly by factor and condition.

Table 5.

Average number of the percentage of activated areoles with their standard errors obtained monthly by factor and condition.

| Factors |

Cases |

Induction Period in Presence of PGRs (1)

|

|

Development Period in Absence of PGRs |

| 1st Month |

2nd Month |

|

3rd Month |

4th Month |

5th Month |

|

p-Value |

Average (4)

|

p-Value |

Average |

|

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

| Treatment (2)

|

|

0.000 |

|

0.006 |

|

|

0.015 |

|

0.207 |

|

0.006 |

|

| BAP8 |

92 |

|

3.263±0.765 bc |

|

10.291±1.572 a |

|

|

18.488±1.897 a |

|

26.509±2.364 a |

|

29.313±2.188 a |

| KIN4 |

76 |

|

0.961±0.475 a |

|

14.414±1.968 ab |

|

|

22.767±2.491 ab |

|

29.755±3.065 a |

|

32.667±3.151 a |

| TDZ1 |

123 |

|

4.629±0.718 c |

|

16.293±1.559 b |

|

|

27.384±1.854 b |

|

33.533±2.474 a |

|

43.107±3.222 b |

| CONTROL |

58 |

|

1.629±0.931 ab |

|

11.336±2.336 a |

|

|

22.995±3.162 ab |

|

26.996±3.164 a |

|

30.727±3.040 a |

| Explant size |

|

0.707 |

|

0.002 |

|

|

0.009 |

|

0.000 |

|

0.000 |

|

| Large |

67 |

|

4.071±1.152 a |

|

14.692±2.102 b |

|

|

22.715±2.375 b |

|

27.452±2.607 b |

|

32.699±2.463 b |

| Medium |

228 |

|

2.899±0.458 a |

|

14.929±1.184 b |

|

|

25.679±1.508 b |

|

33.634±1.850 b |

|

39.160±2.155 b |

| Small |

54 |

|

1.914±0.491 a |

|

5.845±1.129 a |

|

|

14.006±1.424 a |

|

16.344±1.651 a |

|

21.191±2.186 a |

| % of Color |

|

0.742 |

|

0.379 |

|

|

0.849 |

|

0.003 |

|

0.136 |

|

| 0 |

136 |

|

3.298±0.704 a |

|

13.574±1.599 a |

|

|

24.742±2.113 a |

|

35.214±2.553 b |

|

39.862±2.770 b |

| 25 |

74 |

|

2.250±0.579 a |

|

15.962±2.002 a |

|

|

23.722±2.116 a |

|

28.844±2.056 b |

|

33.596±2.282 b |

| 50 |

41 |

|

4.058±1.209 a |

|

14.706±2.380 a |

|

|

22.836±2.850 a |

|

24.828±2.959 ab |

|

28.937±2.981 b |

| 75 |

95 |

|

2.604±0.677 a |

|

10.880±1.503 a |

|

|

21.378±1.946 a |

|

25.246±2.675 ab |

|

32.749±3.437 b |

| 100 |

3 |

|

2.778±2.778 a |

|

13.333±7.265 a |

|

|

15.185±5.614 a |

|

16.852±5.830 a |

|

19.630±8.021 a |

| Type of explant |

|

0.000 |

|

0.003 |

|

|

0.001 |

|

0.000 |

|

0.000 |

|

| Apical |

137 |

|

4.670±0.641 b |

|

14.150±1.118 b |

|

|

20.025±1.416 b |

|

22.614±1.407 b |

|

25.824±1.545 b |

| Central Disc |

158 |

|

1.861±0.587 a |

|

15.504±1.664 b |

|

|

29.325±2.001 c |

|

40.568±2.448 c |

|

47.984±2.760 c |

| Epicotyl |

27 |

|

3.416±0.800 b |

|

5.605±1.296 a |

|

|

11.105±1.559 a |

|

11.926±1.780 a |

|

16.124±2.286 a |

| Hypocotyl |

27 |

|

0.412±0.412 a |

|

6.085±1.874 a |

|

|

16.906±2.278 ab |

|

20.763±2.538 ab |

|

26.258±3.504 ab |

| Total |

349 |

|

2.972±0.380 |

|

13.478±0.905 |

|

|

23.304±1.127 |

|

29.772±1.371 |

|

35.140±1.560 |

Table 6.

Average and standard error of root emission frequency (calculated as number of rooted explants based on the total number of explants) obtained monthly by factor and condition.

Table 6.

Average and standard error of root emission frequency (calculated as number of rooted explants based on the total number of explants) obtained monthly by factor and condition.

| Factors |

Cases |

Induction Period in Presence of PGRs(1)

|

Development Period in Absence of PGRs |

| 1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

|

p-Value |

Average (5)

|

p-Value |

Average |

p-Value |

Average |

| Treatment (2)

|

|

0.000 |

|

0.000 |

|

0 |

|

| BAP8 |

92 |

|

0.228±0.044 b |

|

0.348±0.050 b |

|

0.413±0.052 b |

| KIN4 |

76 |

|

0.368±0.056 c |

|

0.461±0.058 bc |

|

0.487±0.058 bc |

| TDZ1 |

123 |

|

0.008±0.008 a |

|

0.008±0.008 a |

|

0.024±0.014 a |

| CONTROL |

58 |

|

0.517±0.066 d |

|

0.569±0.066 c |

|

0.552±0.066 c |

| Explant size (3)

|

|

0.1329 |

|

0.2903 |

|

0.5802 |

|

| Large |

67 |

|

0.298±0.056 ab |

|

0.343±0.058 a |

|

0.343±0.058 a |

| Medium |

228 |

|

0.232±0.028 b |

|

0.294±0.030 a |

|

0.294±0.030 a |

| Small |

54 |

|

0.130±0.046 a |

|

0.204±0.055 a |

|

0.370±0.066 a |

| % of Color |

|

0.0006 |

|

0.0008 |

|

0.0165 |

|

| 0 |

136 |

|

0.346±0.041 b |

|

0.412±0.042 b |

|

0.404±0.042 c |

| 25 |

74 |

|

0.189±0.046 a |

|

0.257±0.051 a |

|

0.270±0.052 a |

| 50 |

41 |

|

0.195±0.063 a |

|

0.244±0.068 a |

|

0.366±0.076 b |

| 75 |

95 |

|

0.116±0.033 a |

|

0.168±0.039 a |

|

0.200±0.041 a |

| 100 |

3 |

|

0.000±0.000 ab |

|

0.000±0.000 ab |

|

0.333±0.333 ab |

| TE(4)

|

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

0 |

|

| Apical |

137 |

|

0.431±0.042 b |

|

0.511±0.043 b |

|

0.504±0.043 b |

| Central Disc |

158 |

|

0.089±0.023 a |

|

0.127±0.027 a |

|

0.133±0.027 a |

| Epicotyl |

27 |

|

0.222±0.082 a |

|

0.296±0.090 a |

|

0.519±0.098 b |

| Hypocotyl |

27 |

|

0.037±0.037 a |

|

0.111±0.062 a |

|

0.222±0.082 a |

| Total |

349 |

|

0.229±0.022 |

|

0.289±0.024 |

|

0.315±0.025 |

Table 7.

Percentage of rooting during the first three months per combination of factors.

Table 7.

Percentage of rooting during the first three months per combination of factors.

| Plant size(1)

|

Type of explant |

% Color |

TREATMENT (2)

|

| BAP8 |

KIN4 |

TDZ1 |

CONTROL |

| 1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

1st Month |

2nd Month |

3rd Month |

| Large |

Apical |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

| 25 |

16.67 |

66.67 |

66.67 |

66.67 |

66.67 |

66.67 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 50 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

| 75 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| Central Disc |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

14.29 |

28.57 |

50.00 |

| 25 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

16.67 |

16.67 |

16.67 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 75 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

25.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| Medium |

Apical |

0 |

50.00 |

93.75 |

93.75 |

87.50 |

93.75 |

93.75 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

84.38 |

96.88 |

96.88 |

| 25 |

50.00 |

80.00 |

80.00 |

90.00 |

90.00 |

90.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 50 |

50.00 |

75.00 |

75.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 75 |

28.57 |

28.57 |

28.57 |

42.86 |

42.86 |

42.86 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| Central Disc |

0 |

12.50 |

12.50 |

12.50 |

18.75 |

31.25 |

31.25 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

6.25 |

12.50 |

21.88 |

| 25 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

10.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

20.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

25.00 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 75 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

21.43 |

21.43 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| Small |

Epicotyl |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

93.75 |

93.75 |

100.00 |

| 25 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 50 |

25.00 |

50.00 |

100.00 |

25.00 |

50.00 |

50.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 75 |

12.50 |

50.00 |

87.50 |

62.50 |

75.00 |

87.50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 100 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| Hypocotyl |

0 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

6.25 |

6.25 |

6.25 |

| 25 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

33.33 |

0.00 |

100.00 |

100.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 50 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

50.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

25.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 75 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| 100 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

- |

- |

- |

| Total for treatment |

21.71 |

33.55 |

38.82 |

36.67 |

46.67 |

48.00 |

0.68 |

0.68 |

0.68 |

49.19 |

55.65 |

61.29 |

Table 8.

Number and type of the activated areolas and the percentage of coloration of the obtained shoots in relation to the percentage of coloration of the initial plants.

Table 8.

Number and type of the activated areolas and the percentage of coloration of the obtained shoots in relation to the percentage of coloration of the initial plants.

| % color of the original plant |

Nº of activated areolas |

Color of activated areola(1)

|

Percentage of shoot coloration |

| C |

M |

G |

0% |

<50% |

>50% |

100% |

| 0 |

368 |

0 |

0 |

368 |

368 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 25 |

177 |

31 |

57 |

89 |

112 |

18 |

14 |

33 |

| 50 |

107 |

22 |

44 |

41 |

55 |

21 |

10 |

21 |

| 75 |

217 |

94 |

79 |

44 |

77 |

18 |

21 |

101 |

| 100 |

5 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

| Total |

874 |

150 |

182 |

542 |

612 |

59 |

46 |

157 |

Table 9.

Canonical correlation between evaluated factors and their corresponding significance values (p-value) for each combination.

Table 9.

Canonical correlation between evaluated factors and their corresponding significance values (p-value) for each combination.

| Interactions |

p-Value |

| Color percentage of the initial plant * Color of the activated areolas |

0.000 |

| Color percentage of the initial plant * Color percentage of the obtained shoots |

0.000 |

| Color of the activated areolas * Color percentage of the obtained shoots |

0.000 |

| Hormonal treatment * Color of the activated areolas |

0.133 |

| Hormonal treatment * Color percentage of the obtained shoots |

0.766 |

Table 10.

Number of shoots obtained from the initial variegated plants as a function of the type of activated areola. Number of shoots obtained from areoles derived from the initial variegated plants classified according to the type of areola (shoots from the activated areoles of the initial chlorophyllic plants are not included).

Table 10.

Number of shoots obtained from the initial variegated plants as a function of the type of activated areola. Number of shoots obtained from areoles derived from the initial variegated plants classified according to the type of areola (shoots from the activated areoles of the initial chlorophyllic plants are not included).

| Type of areola |

Coloration of shoots (1)

|

| S0 |

S1 |

S2 |

S3 |

| Color (C) |

3 |

4 |

15 |

129 |

| Mixed (M) |

74 |

48 |

31 |

28 |

| Green (G) |

166 |

5 |

1 |

0 |

| Total |

243 |

57 |

47 |

157 |

| Total of shoots |

504 |

Table 11.

Experimental design of the trial.

Table 11.

Experimental design of the trial.

| Plant size |

% Color |

Nº plants |

N° of explants evaluated (1)

|

Treatment (2)

|

| A |

CD |

EP |

HYP |

BAP8 |

KIN4 |

TDZ1 |

CONTROL |

| |

0 |

7 |

14 |

14 |

- |

- |

- |

- |

- |

28 |

| Large |

25 |

9 |

18 |

18 |

- |

- |

12 |

12 |

12 |

- |

| (12-16 mm) |

50 |

2 |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

4 |

4 |

- |

- |

| |

75 |

6 |

12 |

12 |

- |

- |

8 |

8 |

8 |

- |

| |

0 |

40 |

80 |

80 |

- |

- |

32 |

32 |

32 |

64 |

| Medium |

25 |

15 |

30 |

30 |

- |

- |

20 |

20 |

20 |

- |

| (8-12 mm) |

50 |

7 |

14 |

14 |

- |

- |

8 |

8 |

12 |

- |

| |

75 |

21 |

42 |

42 |

- |

- |

28 |

28 |

28 |

- |

Small

(4-12 mm)

|

0 |

16 |

- |

- |

16 |

16 |

- |

- |

- |

32 |

| 25 |

7 |

- |

- |

7 |

7 |

6 |

4 |

4 |

- |

| 50 |

12 |

- |

- |

12 |

12 |

8 |

8 |

8 |

- |

| 75 |

24 |

- |

- |

24 |

24 |

16 |

16 |

16 |

- |

| 100 |

14 |

- |

- |

14 |

42 |

10 |

10 |

8 |

- |

| Total for condition |

214 |

214 |

73 |

73 |

152 |

150 |

148 |

124 |

| Total trial |

180 |

574 |

574 |