1. Introduction

We present a case documenting the changes in pain and disability in a patient suffering from low back and neck pain for several years. The patient received prior conservative chiropractic therapy, but did not demonstrate measurable improvements either subjectively nor objectively until receiving a specific therapeutic approach; namely, Chiropractic BioPhysics

® (CBP

®) technique. Chronic low back pain (CLBP) and chronic neck pain (CNP) are major contributors to the global burden of disease (GBD) [

1] and they are frequently rated amongst the greatest causes of disability world-wide with CLBP listed as first and CNP listed at fourth. It is estimated that annually, more than

$40 billion dollars (USD) and more than

$2000 USD per patient is spent on the treatment of low back pain in the US and globally [

2]. This burden of suffering for the patient and the societal financial burden significantly contributes to years lived with disability (YLDs) and is an important research topic for the biomedical healthcare fields in order to elucidate effective strategies that offer safe, effective, and economical treatment protocols [

3].

Abnormal spine and postural alignment are known contributors to chronic pain and recent studies have shown that conservative therapies can reduce abnormal spine parameters, improve posture and reduce pain following treatment [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Continued evaluation of biomechanical approaches for the assessment and treatment of CLBP is important as emerging evidence is pointing to successful outcomes using such methods. Thus, the purpose of this case is to document successsful treatment of a patient with chronic spine pain by methods that have shown efficacy in improving pain and dysfunction by improving postural muscle strength and function, reducing abnormal postural loads and improving the normal configuration of the spine [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. The (CBP

®) protocol used on this patient will be outlined and described in detail. This case details the history and subjective complaints, intake evaluations including radiography and postural analysis, and the outcome measure questionnaires used at the initial, re-examination, and long-term follow-up exams.

2. Methods

2.1. Patient History, Examination Results, Subjective and Objective Findings

A 38-year-old male suffering with constant, severe (7/10 on a numeric rating scale (NRS) of 0-10 where 0 is no pain and 10 is max pain) CLBP for over 5 years presented for treatment of his dysfunction and disability due to the ailment. The original cause of the low back pain was insidious and worsened over several years. Chronic intermittent neck pain was reported without a known cause. The pain would worsen with long days at work and with prolonged driving.The patient sought treatment with chiropractic spinal manipulation sporadically over five years with minimal short-term improvement in symptoms and disability with no long-term resolution. Due to the worsening of his condition, he sought out a spine rehabilitation facility in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, USA, specilizing in CBP conservative physical medicine methods.

The patient received a thorough history, physical examination, neurological and orthopedic testing, and subjective and objective assessment using outcome measures. Patient reported outcomes (PROs) were assessed for multiple regions of the spine and general health. The revised Oswestry low back pain disability index (RODI) [

10] questionnaire was completed to determine how his CLBP pain affected his daily life and to assess self-rated LBP disability. His initial RODI score was 54% indicating severe disability due to low back pain. The patient completed a short-form 36 (SF-36) health-related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaire to assess self-reported wellness. [

11] The SF-36 outcome assessment provides scaled scores for eight different HRQoL domains on a scale of 0 to 100, where 0 is the lowest and 100 is the highest possible score. All of the initial SF-36 scores measured below normal indicating a significant impact of the chronic pain on the patient’s quality of life (

Table 1).

2.2. Postural Analysis and Radiographic Findings

Posture examination and analysis was performed using PostureScreen

® mobile posture analysis software (PostureCo, Inc., Trinity, FL, USA) and revealed the following: in the sagittal plane, the patient stood with anterior head translation (+T

zH), posterior thorax translation (-T

zT), and anterior pelvic translation (+T

zP) (

Figure 1A)

Radiography of the spine was performed with the patient upright in neutral position. Anterior-posterior (AP) and lateral films were assessed using the PostureRay

® digital radiographic mensuration software (PostureCo, Inc., Trinity, FL, USA) [

14]. The program uses the Risser-Ferguson measurement for the AP views and the Harrison posterior tangent method (HPTM) of measurement for the lateral views. The program also compares the patient alignment of both segmental and global measurements to models of ideal spine parameters; prior studies have shown exceptionally high reliability using this system [

15]. The sagittal spine absolute rotation angle (ARA) from the 2

nd cervical vertebra to the 7

th (ARA

C2-C7) measured -18.1° (average is -34°, ideal is -42°, pain threshold is -20° [

16]) (

Figure 2A-C,

Figure 3A-C,

Figure 4A-C and

Figure 5A-C) and the AP cervical X-ray demonstrated a right lateral flexion angle relative to true vertical of the lower cervical and upper thoracic spine (cervico-dorsal angle (CDA)) measuring 5.6° (ideal is 0° [

16]) with a right translation of C2 with respect to T5 (T

XC2-T5) measuring -17.2 mm (ideal is 0 mm). There was an increased mid-thoracic angle with a right-sided concavity from T1 to T12 (MTA

T1-T12) of 9.1° (ideal is 0° [

16]) with an increased translation at T8 apex of mid-thoracic angle with respect to T12 (+T

XT8-T12) measuring 15.2 mm (ideal is 0 mm). There was a decreased sagittal curvature of the lumbar spine from L1 to L5 (ARA

L1-L5) measuring -17.9° (ideal is -40°, average range is 35°-45° [

16]). The modified Ferguson pelvic radiograph demonatrated a sacral base unleveling in the frontal plane measuring -11.3 mm, being lower on the right. There was a lumbosacral angle from L1 to L5 with an L3 apex (LSA L1-L5) of -84.9° (ideal is 90°).

2.3. Treatment Protocols

Following the examination and analysis the patient agreed to participate in a multi-modal regimen to reduce the measured abnormal postural findings, reduce abnormal spine parameters and reduce pain and dysfunction. The patient was treated 36 times in-office over 3 months [

16]. The patient received manual spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and CBP Mirror Image

® (MI

®) adjustments using a chiropractic drop table and instrument adjusting using an Impulse

® high velocity low amplitude (HVLA) adjusting instrument (Neuromechanical Innovations, Chandler, AZ, USA) [

17]. These MI

® adjustments involve positioning the patient in the mathematical opposite direction of the measured postural and spine abnormalities. Once the patient is properly positioned, a drop table mechanism or mechanical instrument is used to place the patient in the corrected posture.

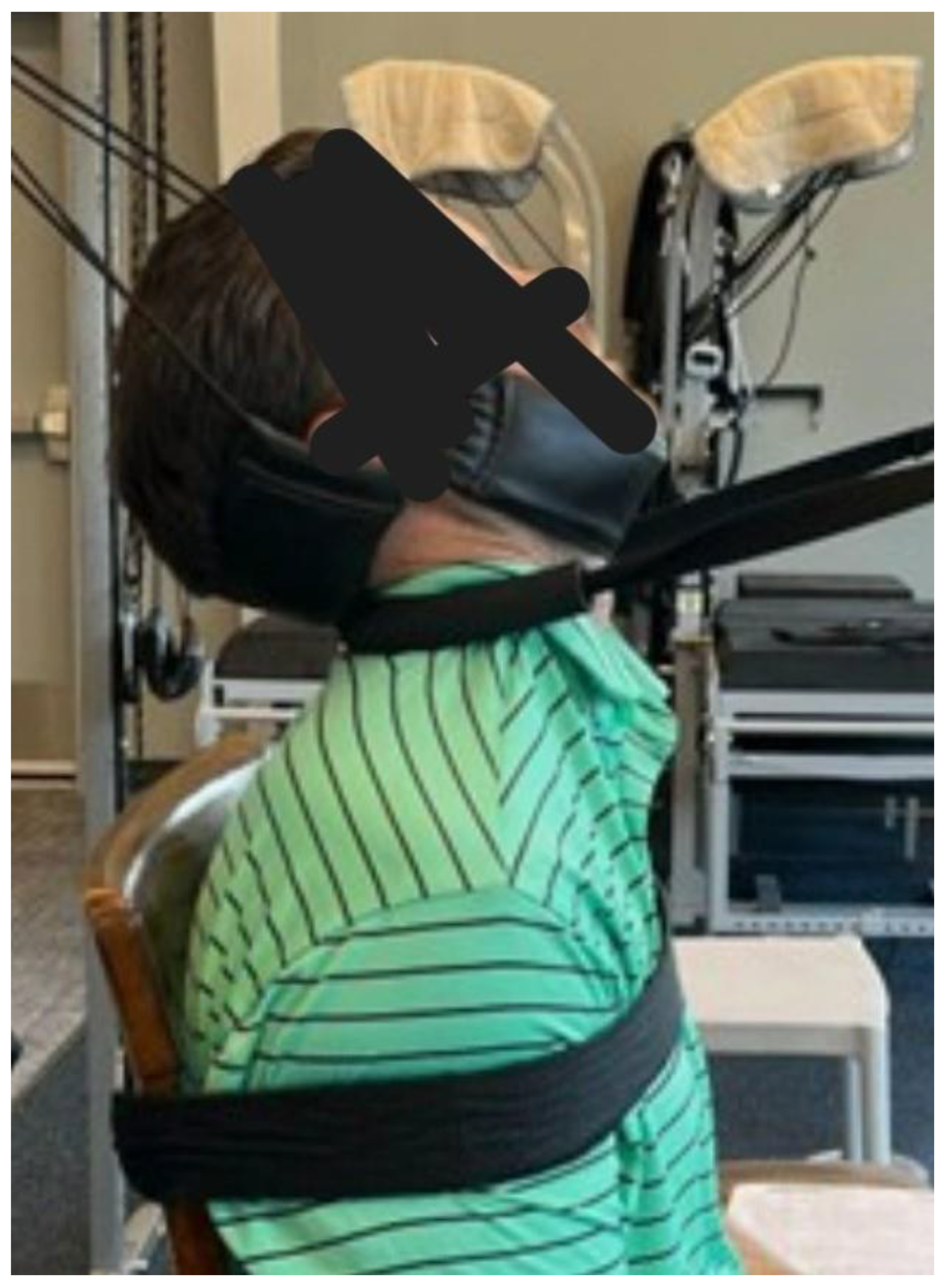

MI

® traction was performed using a Universal Tractioning Systems

® (UTS

®) total spine device (Universal Tractioning Systems, Inc., Las Vegas, NV, USA) with the patient in a semi-seated position on a stool with a cervical extension strap holding the skull and upper cervical spine in extionsion with a counter stress pulling from posterior to anterior through the mid cervical spine. The traction was applied for 5-12 minutes with 12 lbs in the posterior and 20 lbs in the anterior. Further, a posterior-to-anterior (PA) static pull using a comfortable strap on a pully system was positioned at L3-L4 through the disc plane line. Additionally, an AP static pull with a comfortable padded strap at T6-T8 to stabilize the thorax, while a PA dynamic weighted cervical pull at the mid-cervical spine is applied with a small, circular padded comfortable strap angled at the mid cervical spine (

Figure 6). Further, a posterior and superior static distraction pull to the head and neck using an padded occipital and chin harness. The patient also performed seated UTS

® MI

® traction with a left head translation (+T

xH) pull and a right thoracic counterstress [

18].

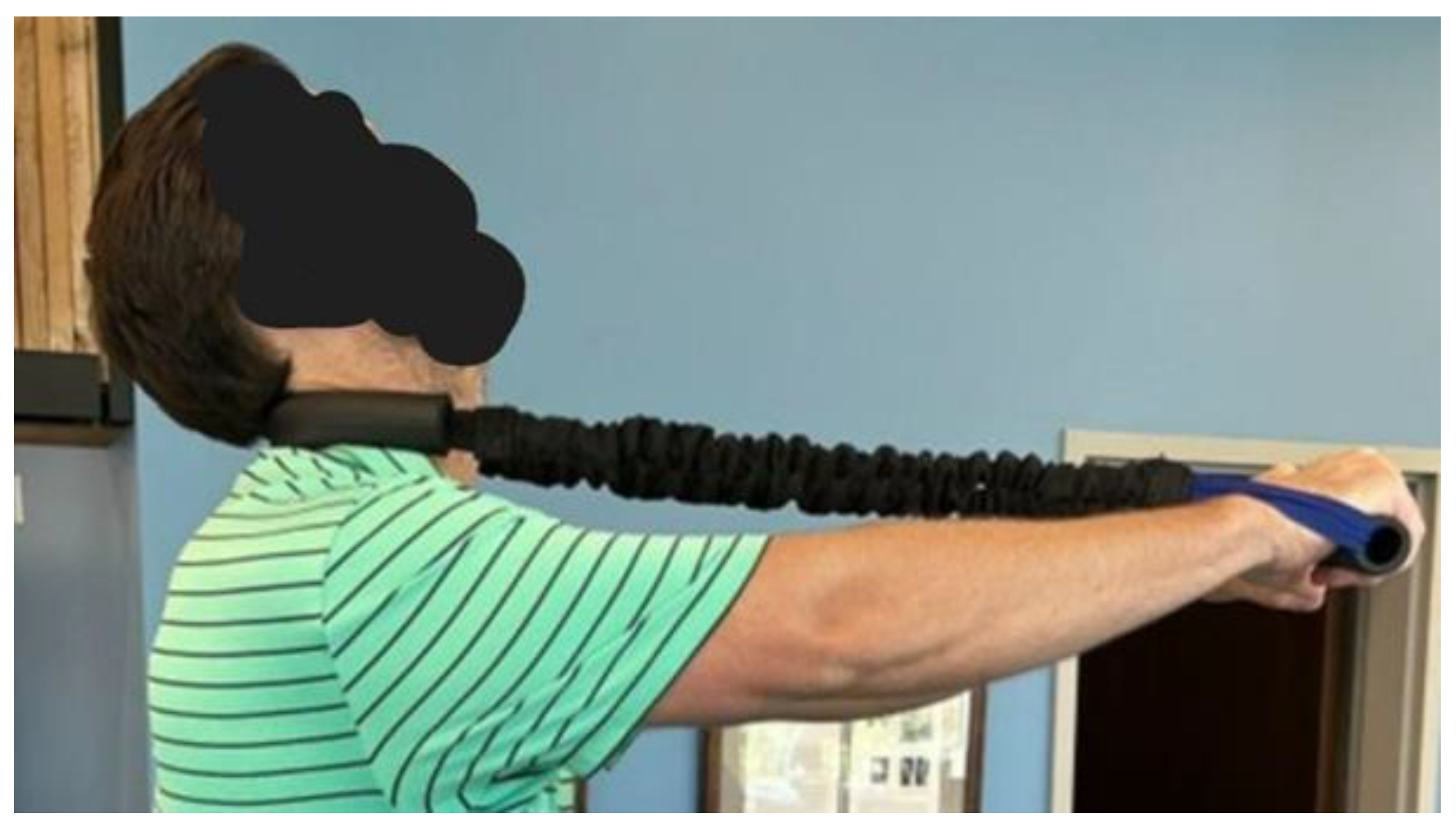

MI

® exercises were performed including +T

xH, left thoracic rotation or lateral flexion (-R

zT), and extension exercises for the strengthening the lumbar spine musculature. The patient was prescribed daily home care consisting of MI

® traction and exercises held for no longer than 15 seconds and worked up to 50 repetitions a day. The exercises and traction was completed at increasing tolerance to soreness using a Pro-Lordotic Neck Exerciser

TM (Circular traction, LLC. Huntington Beach, CA, USA) (

Figure 7) [

19] and cervical and lumbar Dennerolls

® (Denneroll™ cervical traction orthotic (DCTO) and Denneroll

TM lumbar traction othotic (DMTO)) to create cervical and lumbar extension moments based on previously published average, ideal and pain threshold models (14,15). The DCTO/DLTO have a very specific peak that is placed at the area of the spine that requires extension moment as measured on the PostureRay

® sagittal spine profile mensuration parameters. The patient was also prescribed a 12 mm cork full foot lift to be worn in the right footwear to correct for a right short anatomical leg length inequality (ALLI) that was measure on the AP modified Fergusion radiograph for ALLI assessment. All exercises wer to patient tolerance, beginning with few repititions and increasing to as many as 50 repetitions per day with an intensity and duration beginning at 3-5 seconds and increasing to as sustained hold of no more than 15 seconds. Similar traction protocols were followed with the patient beginning the traction for 2-5 minutes per session depending on tolerance and increasing to up to 15 minutes of traction wth progressively increased tension in the stresses on the spine in the MI

® position.

3. Results and 1-Year Follow-Up:

Post-treatment posture analysis showed improved posture (

Figure 1A-C). Post-treatment radiographic examination revealed the following: improved ARA

C2-C7 measuring -29.4° (vs. -18.1°); Rotation around the z-axis of the thorax (R

ZT5) measured 1.8° (vs. normal 0°); improved -T

xC2-T5 measuring -5.7 mm (vs. -17.2 mm); improved MTA T1-T12 measuring 2.1° (vs. 9.1°); improved +T

xT8-T12 measuring 3.5 mm (vs. 15.2 mm); improved ARA

L1-L5 measuring -25.1° (vs. -17.9°); improved sacral base unleveling in the frontal plane measuring -1.0 mm low on the left (vs. -11.3 mm low on the right); and improved LSA L1-L5 of -88.0° (vs. -84.9°) (

Figures 2B-5B). Post-treatment RODI score was 12% (vs. 54%) indicating minimal disability. All post-treatment SF-36 scores showed improvements (

Table 1). One-year follow-up posture analysis showed a maintenance of the improved posture. One-year follow-up radiographic examination revealed maintained sagittal balance and coronal spinal alignment correction improvements (Figures 2C–5C). One-year follow-up RODI score was 2% indicating minimal or resolved disability from baseline (54%). Post-treatment SF-36 scores showed maintained or further improved HRQoL measures reported by the patient. Long term follow-up found minimal forward head posture on the lateral posture photograph, a slight return to baseline on the A-P cervical radiograph with a right head translation measuring 7mm. Lateral cervical radiograph assessment at long-term found the lordosis to be well maintained at 34° ARA with minimal C2-vertical anterior head translation of 6mm. lateral lumbar radiograph showed a slight loss of lordosis at follow-up of 19°. All subjective initial symptoms were reported to be resolved at long-term follow-up. Long term follow-up SF-36 scores were the same as post-treatment with the exception of vitality which was slightly improved. There were no positive orthopedic or neurological tests at follow-up. The patient continued to use the ProLordotic neck exerciser at home 1-3 times per week for up to 10 minutes. (

Figure 7)

4. Discussion

This case documents the successful treatment of a male who suffered from chronic spine pain and significant disability. After CBP® conservative spine rehabilitation, there was an increase in cervical and lumbar lordosis, decrease in lateral head and thoracic translation; all the postural improvements corresponded with improvements in pain, disability and function after only 3 months. The imporoved posture and symptom reductions were maintinaed at a long-term follow-up.

The treatment outcomes for the present case were consistent with prior reported case reports [

19], cohort and case series [

20], randomised controlled trials [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], systematic reviews of the literature and other prior investigations [

26,

27,

28,

29]. This protocol is designed to target abnormal postural permutations by addressing musculature asymmetries. Based on the abnormal postural and radiographic findings, a specific program of MI

® exercises that use repetition and sustained contraction to improve coronal and sagittal balance. The exercise begin with minimal intensity and progressed to contractions being held for a longer period of time as well and increased repetitions. The presence of abnormal postural postitions causing musculature asymmetries has been reported for many decades [

30].

SMT has been used for a very long time to treat spine pain with variable results. General spinal manipulation is known to increase range of motion and decrease pain temporarily, however no studies have shown consistent long-term improvement in subjective and objective outcomes for SMT. This is consistent with our patient who received traditional SMT from a chiropractor without long-term reduction in symptoms [

31]. The MI

® SMT used in this study was different due to the fact that each manipulation is based on moving the patient toward improved sagittal and coronal balance. Improving postural abnormalities has previously been shown to reduce abnormal loads on soft tissues such as disc and spine ligaments as well and improve latency and amplitude in the central nervous system [

32]. It has been theorized that abnormal postures increase energy expenditure in the spinal musculature and reduce efficiency in the nervous system centers involved with postural control [

7,

33,

34]. MI

® SMT involves placing the patient in the mathematical opposite of the measured spinal abnormalities and introducing a force via a drop-table mechanism or a HVLA instrument to improve neuroplastic changes in postural control areas in the CNS [

6].

Postural MI

® traction is designed to influence visco-elastic tissues such as the spinal ligaments and intervertebral discs that do not respond to rapid impulses from SMT, but require time-dependent forces to cause creep in the direction of normal spine curvatures in the sagittal plane and toward a straight spine in the coronal plane [

35]. The traction forces are applied according to the measured abnormal spine parameters and involve as-comfortable-as-possible patient positioning to hold the spine in a closer-to-normal position and slowly increased traction intensity and time so as to stretch the visco-elastic structures towards a more neutral and balanced posture. The results of this case is consistent with prior studies of the MI® traction and were found in conjunction with the positive subjective outcome measures and PRO’s following treatment and correction was sustained at long-term follow-up. These methods of improving sagittal balance and cervical and lumbar lordosis are found have been shown to be repeatable and reliable to induce increases in lumbar and cervical lordosis toward a more ideal angulation in both conservative and surgical studies [

5,

6,

8,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

22,

23].

Radiography in the treatment of spine conditions has a long reported history, however, there are those who claim that radiography is dangerous [

36,

37,

38]. Radiography has historically been a fear-inducing topic, due to concerns surrounding the genetic damage induced, but this traditional idea is not currently supported by data [

39,

40,

41] that shows the hormetic effects that occur in the body. That is, although damage occurs initially, the body is an adaptive organism, whereby, any initial damage gets repaired. Thus, low-dose exposures including spinal X-rays do not present a net effect of damage. Therefore, the clinical effectiveness of radiography is supported as only a net benefit results as there are no risks from a risk-to-benefit perspective [

35,

39,

41,42].

Chronic spine pain including CLBP and CNP are a global epidemic and are consistently rated as the 1st and 4th leading causes of disability globally [

1]. These conditions produce a significant burden for health care providers, patients, and societal financial burden [

2]. Having repeatable, reliable and consistent protocols for the diagnosis and treatment of spine conditions is important to improve the assessment and recommendations for this patient population which grows larger each year [

3]. Treatment cost should be considered in treatment recommendations and in the regulation of physicians and therapits who treat these patients. Having reliable and affordable treatment options is desireable across multiple levels of administrative and provider care. This case demonstrating the effectiveness of CBP® care offers an alternative treatment protocol, with reliable and economical results.

Further studies are necessary to warrant the inclusion of these protocols in governing bodies’ recommendations and best practice guidelines for the treatment of these and other conditions. Limitations of this study are the reportage of results on only one patient, however these results are consistent with prior literature. Limitations also include the relatively short long-term follow-up (1 year); longer term (5-year or 10-year) follow-up studies would provide better confirmation of long-term benefits.

5. Conclusion

The results of this single case indicates that CBP® corrective chiropractic care may be an effective method to treat abnormal spinal alignment parameters and abnormal posture which contributes to CLBP, CNP and disability causing decreased HRQoL and abnormal PROs. A simple multi-modal conservative threatment protocol could reduce financial burden for treating low back and neck pain and reduce risks associated with pharmacologic and more invasive interventions. Improvement in spinal alignment and posture may result in long-term reduction or resolution of cLBP and improved HRQoL. This case shows the need for more conservative research involving spinal biomechanics and rehabilitation in patients with spine pain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.H. and K.S.; methodology, K.S., J.W.H., P.A.O., D.E.H.; validation, J.W.H, P.A.O, D.E.H.; data curation, K.S., J.W.H.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.H., P.A.O.; writing—review and editing, K.S., J.W.H., P.A.O., D.E.H.; supervision, D.E.H.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Chiropractic BioPhysics, Non-Profit, Inc., not-for-profit spine research foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not Applicable due to the retrospective nature of the study. Informed consent and patient consent to publish was acquired prior to publication.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient obtained informed consent prior to treatment and publication.

Data Availability Statement

These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain. The authors declare that this literature review is not based on original data.

Conflicts of Interest

Author K.S. declares no competing interests. J.W.H. is a compensated researcher for CBP Non-Profit, Inc. P.A.O. is a compensated consultant and researcher for Chiropractic BioPhysics, NonProfit, Inc. D.E.H. is the CEO of Chiropractic BioPhysics® (CBP®) and provides post-graduate education to health care providers and physicians. Spine rehabilitation devices are distributed through this company. D.E.H. is the president of CBP Non-Profit, Inc., a not-for-profit spine research foundation.

References

- GBD 2021 Low Back Pain Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of low back pain, 1990-2020, its attributable risk factors, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol. 2023 May 22;5(6):e316-e329. [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, L.J. Global burden of disease estimates of low back pain: Time to consider and assess certainty? Int J Public Health. 2024 Feb 14;69:1606557. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wulf, H.S.; Culbreth, G.; et al.; Assessing the impact of health-care access on the severity of low back pain by country: a case study within the GBD framework. The Lancet Rheumatology, 2024 2024 Sep;6(9):e598-e606. [CrossRef]

- Du, S.H.; Zhang, Y.H.; Yang, Q.H.; et al. Spinal posture assessment and low back pain. EFORT Open Rev. 2023 Sep 1;8(9):708-718. [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Ehsani, N.N.; Moustafa, I.M.; Harrison, D.E.; Restoring cervical lordosis by cervical extension traction methods in the treatment of cervical spine disorders: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Phys Ther Sci. 2021 Oct;33(10):784-794. [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.; Harrison, D.E. The efficacy of cervical lordosis rehabilitation for nerve root function and pain in cervical spondylotic radiculopathy: A randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6515. Published 2022 Nov 2. [CrossRef]

- Quek, J.; Pua, Y.H.; Clark, R.A.; Bryant, A.L. Effects of thoracic kyphosis and forward head posture on cervical range of motion in older adults. Man Ther. 2013 Feb;18(1):65-71. [CrossRef]

- Norton, T.C.; Oakley, P.A.; Haas, J.W.; Harrison, D.E. Positive outcomes following cervical acceleration-deceleration (CAD) injury using chiropractic BioPhysics® methods: A pre-auto injury and post-auto injury case series. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caneiro JP, O'Sullivan P, Burnett A, Barach A, O'Neil D, Tveit O, Olafsdottir K. The influence of different sitting postures on head/neck posture and muscle activity. Man Ther. 2010 Feb;15(1):54-60. [CrossRef]

- Koivunen, K.; Widbom-Kolhanen, S.; Pernaa, K.; Arokoski, J.; Saltychev, M. Reliability and validity of Oswestry disability index among patients undergoing lumbar spinal surgery. BMC Surg. 2024 Jan 3;24(1):13. [CrossRef]

- Ware, J.E.Jr. SF-36 health survey update. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000 Dec 15;25(24):3130-9. [CrossRef]

- Iacob, S.M.; Chisnoiu, A.M.; Lascu, L.M.; et al. (2018). Is PostureScreen® Mobile app an accurate tool for dentists to evaluate the correlation between malocclusion and posture? CRANIO®, 2020 38(4), 233–239. [CrossRef]

- Boland, D.M.; Neufeld, E.V.; Ruddell, J.; Dolezal, B.A.; Cooper, C.B. Inter- and intra-rater agreement of static posture analysis using a mobile application. J Phys Ther Sci. 2016 Dec;28(12):3398-3402. [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.M.; Mahoor, M.H.; Haas, J.W.; Ferrantelli, J.R.; Dupuis A.L.; Jaeger, J.O.; Harrison, D.E. Intra-examiner reliability and validity of sagittal cervical spine mensuration methods using deep convolutional neural networks. J Clin Med. 2024 Apr 27;13(9):2573. [CrossRef]

- Arnone, P.A.; McCanse, A.E.; Farmen, D.S.; Alano, M.V.; Weber. N,J.; Thomas, S.P.; Webster, A.H. Plain Radiography: A unique component of spinal assessment and predictive health. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Mar 12;12(6):633. [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.D.; Harrison, D.E.; Haas, J,W.; Evidence-based protocol for structural rehabilitation of the spine and posture: review of clinical biomechanics of posture (CBP) publications. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2005 Dec;49(4):270-96.

- Colloca, CJ.; Cunliffe, C.; Hegazy, M.A. et al. Measurement and analysis of biomechanical outcomes of chiropractic adjustment performance in chiropractic education and practice. JMPT 2020;July43(3):212-224.

- Harrison, D.E.; Oakley, P.A. A Systematic review of CBP® methods applied to reduce lateral thoracic translation (pseudo-scoliosis) postures. JCC. 2022;5(1):13-18.

- Oakley, P.A.; Kallan, S.Z.; Haines, L.D.; Harrison, D.E. The treatment and rationale for the correction of a cervical kyphosis spinal deformity in a cervical asymptomatic young female: a Chiropractic BioPhysics® case report with follow-up. J Phys Ther Sci. 2023 May;35(5):389-394. [CrossRef]

- Haas, J.W.; Oakley, P.A.; Ferrantelli, J.R.; Katz, E.A.; Moustafa, I.M.; Harrison, D.E. Abnormal static sagittal cervical curvatures following motor vehicle collisions: A retrospective case series of 41 patients before and after a crash exposure. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 957. [CrossRef]

- Niemistö, L.; Lahtinen-Suopanki, T.; Rissanen, P.; Lindgren, K.A.; Sarna, S.; Hurri, H. A randomized trial of combined manipulation, stabilizing exercises, and physician consultation compared to physician consultation alone for chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(19):2185-2191. [CrossRef]

- Suwaidi, A.S.A.; Moustafa, I.M.; Kim, M.; Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. A comparison of two forward head posture corrective approaches in elderly with chronic non-specific neck pain: A randomized controlled study. J Clin Med. 2023 Jan 9;12(2):542. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.A.; Scheer, J.K.; Smith, J.S.; Deviren, V.; et al. The impact of standing regional cervical sagittal alignment on outcomes in posterior cervical fusion surgery. Neurosurgery. 2012 Sep;71(3):662-9; discussion 669. [CrossRef]

- Barrey, C.; Jund, J.; Noseda, O.; Roussouly, P. Sagittal Balance of the Pelvis-Spine Complex and Lumbar Degenerative Diseases: A Comparative Study about 85 Cases. Eur. Spine J. 2007, 16, 1459–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moustafa, I.M.; Diab, A.A.; Harrison, D.E. The efficacy of cervical lordosis rehabilitation for nerve root function and pain in cervical spondylotic radiculopathy: A randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betz, J.W.; Lightstone, D.F.; Oakley, P.A.; Haas, J.W.; Moustafa, I.M.; Harrison, D.E. Reliability of the biomechanical assessment of the sagittal lumbar spine and pelvis on radiographs used in clinical practice: A systematic review of the literature. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, P.; Kallan, S.; Harrison, D. Structural rehabilitation of the lumbar lordosis: A selective review of CBP® case reports. JCC. 2022;5(1):206-211.

- Oakley, P.A.; Ehsani, N.N.; Moustafa, I.M.; Harrison, D.E. Restoring cervical lordosis by cervical extension traction methods in the treatment of cervical spine disorders: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Phys Ther Sci. 2021 Oct;33(10):784-794. [CrossRef]

- Koźlenia, D.; Kochan-Jacheć, K. The impact of interaction between body posture and movement pattern quality on injuries in amateur athletes. J Clin Med. 2024 Mar 2;13(5):1456. [CrossRef]

- Rubinstein, S.M.; de Zoete, A.; van Middelkoop, M.; Assendelft, W.J.J.; de Boer, M.R.; van Tulder, M.W. Benefits and harms of spinal manipulative therapy for the treatment of chronic low back pain: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2019 Mar 13;364:l689. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Yang, J.H.; Chang, D.G.; Lenke, L.G.; Suh, S.W.; Nam, Y.; Park, S.C.; Suk, S.I. Adult spinal deformity: A comprehensive review of current advances and future directions. Asian Spine J. 2022 Oct;16(5):776-788. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Yang, J.H.; Chang, D.G.; Lenke, L.G.; Suh, S.W.; Nam, Y.; Park, S.C.; Suk, S.I. Adult spinal deformity: A comprehensive review of current advances and future directions. Asian Spine J. 2022 Oct;16(5):776-788. [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.Y.; Lee, Y.B.; Kang, C.K. Effect of forward head posture on resting state brain function. Healthcare (Basel). 2024 Jun 7;12(12):1162. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, S.Y. The Effects of Forward Head Posture on the Brain’s Resting State Functional Connectivity. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadano, S.; Tanabe, H.; Arai, S. et al. Lumbar mechanical traction: a biomechanical assessment of change at the lumbar spine. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019 20;155. [CrossRef]

- Oakley, P.A.; Harrison, D.E. Radiophobia: 7 Reasons why radiography used in spine and posture rehabilitation should not be feared or avoided. Dose Response. 2018 Jun 27;16(2):1559325818781445. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.J.; Downie, A.S.; Maher, C.G.; Moloney, N.A.; Magnussen, J.S.; Hancock, M.J. Imaging for low back pain: is clinical use consistent with guidelines? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine J. 2018 18(12):2266-2277. [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H.J.; Downie, A.S.; Moore, C.S.; French, S.D. Current Evidence for Spinal X-Ray Use in the Chiropractic Profession: A Narrative Review. Chiropr Man Therap 2018, 26, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jargin, S.V. Radiation safety and hormesis. Front Public Health. 2020 Jul 24;8:278. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Baldwin, L.A. Hormesis as a biological hypothesis. Environ Health Perspect. 1998 Feb;106 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):357-62. [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, E.J.; Blain, R. The Occurrence of Hormetic Dose Responses in the Toxicological Literature, the Hormesis Database: An Overview. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2005, 202, 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up sagittal posture. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal sagittal posture. The red line represents the actual sagittal posture of the patient. The yellow circles with the black ring inside are anatomical landmarks made to analyze the patient’s posture.

Figure 1.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up sagittal posture. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal sagittal posture. The red line represents the actual sagittal posture of the patient. The yellow circles with the black ring inside are anatomical landmarks made to analyze the patient’s posture.

Figure 2.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up neutral lateral cervical radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal sagittal cervical spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual posterior tangent lines of the C2-T1 vertebrae.

Figure 2.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up neutral lateral cervical radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal sagittal cervical spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual posterior tangent lines of the C2-T1 vertebrae.

Figure 3.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up AP cervical radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal frontal cervical spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual frontal cervical alignment of the C1-T5 vertebrae. The right side of the radiographs are the left side of the patient.

Figure 3.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up AP cervical radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal frontal cervical spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual frontal cervical alignment of the C1-T5 vertebrae. The right side of the radiographs are the left side of the patient.

Figure 4.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up AP thoracic radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal frontal thoracic spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual frontal alignment of the T1-T12 vertebrae. The right side of the radiographs are the left side of the patient.

Figure 4.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up AP thoracic radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal frontal thoracic spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual frontal alignment of the T1-T12 vertebrae. The right side of the radiographs are the left side of the patient.

Figure 5.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up lateral lumbar radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal sagittal lumbar spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual lumbar alignment of the T12-L5 vertebrae.

Figure 5.

A-C. Pre-treatment, post-treatment, and 1-year follow-up lateral lumbar radiographs. Image Features: The green line represents a normal, ideal sagittal lumbar spinal alignment. The red line represents the actual lumbar alignment of the T12-L5 vertebrae.

Figure 6.

Cervical extension Mirror Image® traction. Image description: A sample image of a patient undergoing Mirror Image® traction with a comfortable padded strap on the jaw and occiput and a counter strap through the mid cervical spine in a posterior-anterior and cephalad direction. The front load was 25lbs and the posterior load was static with a fixed pulley.

Figure 6.

Cervical extension Mirror Image® traction. Image description: A sample image of a patient undergoing Mirror Image® traction with a comfortable padded strap on the jaw and occiput and a counter strap through the mid cervical spine in a posterior-anterior and cephalad direction. The front load was 25lbs and the posterior load was static with a fixed pulley.

Figure 7.

The ProLordoticTM neck exercise device. Image Description: An elastic strap through the mid cervical spine is lengthened against extension resistence of the cervical paraspinal muscles. The contraction is held for 15 seconds and performed for no longer than 10 minutes.

Figure 7.

The ProLordoticTM neck exercise device. Image Description: An elastic strap through the mid cervical spine is lengthened against extension resistence of the cervical paraspinal muscles. The contraction is held for 15 seconds and performed for no longer than 10 minutes.

Table 1.

Pre-treatment, Post-Treatment, and 1-Year Follow-Up Results of the SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire.

Table 1.

Pre-treatment, Post-Treatment, and 1-Year Follow-Up Results of the SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire.

| SF-36 Quality of Life Scales |

Normative Mean Scale Scores |

Pre-CBP® Treatment Exam 05/31/2018 |

Post-CBP® Treatment Exam

01/09/2019 |

Post-CBP® Follow-Up Exam

08/07/2019 |

| PF |

72.0 |

25.0 |

90.0 |

90.0 |

| RP |

81.0 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| RE |

81.0 |

0.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

| VT |

61.0 |

45.0 |

60.0 |

65.0 |

| MH |

81.0 |

32.0 |

80.0 |

80.0 |

| SF |

83.0 |

12.5 |

87.5 |

90.0 |

| BP |

75.0 |

22.5 |

77.5 |

77.5 |

| GH |

72.0 |

50.0 |

80.0 |

80.0 |

| ΔH |

84.0 |

45.0 |

100.0 |

100.0 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).