1. Introduction

Industrial hemp (

Cannabis sativa L.), an annual herbaceous plant from the

Cannabaceae family [

1], has historically been a significant crop originating in Asia and extensively cultivated in Europe for textile and food production. Over the centuries, it has been regarded as one of the most essential crops, providing a range of materials and products, including rope, fabric, food, lamp oil, and medicinal products [

2].

Hemp is recognised for its agronomic efficiency, high productivity and minimal technical input requirements. It is resilient to drought and pests, making it a low-maintenance crop. Environmentally, hemp is beneficial as it requires minimal water and no pesticides and effectively suppresses weeds, reducing the need for additional weed control measures [

3]. Moreover, industrial hemp is well-suited for carbon sequestration due to its rapid growth across diverse agroecological zones [

4].

While hemp seeds are primarily used as animal feed, there is growing interest in their potential for human nutrition, leading to increased demand for hemp-derived products such as oil, meal, flour, and protein powder. These products offer a natural, nutrient-rich alternative for human consumption, providing all essential amino and fatty acids required for optimal health [

5]. Nutrient-wise, hemp seeds comprise approximately 25–35% oil, 20–25% protein, 20–30% carbohydrates, 10–15% insoluble fibre, and a rich profile of vitamins and minerals [

6]. Deficiencies in minerals such as Fe, I, and Zn are a growing nutritional problem in human populations. At the same time, the uptake of other elements like Ca, K, Mg, and Se can be poor in specific diets [

7].

Hemp seed oil is notably rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids, presenting a beneficial balance of α-linolenic acid (omega-6) and linoleic acid (omega-3) with an ideal ratio of 2.5–3:1, which is particularly favourable for human dietary needs [

8]. These attributes contribute to the robust market value of hemp seeds, likely leading to their predominant use in human food and nutritional supplements [

9].

Hemp seeds are also a rich source of natural antioxidants and other bioactive components, including bioactive peptides and phenolic compounds such as coumarins, hydroxybenzoic acids, and xanthones. These polyphenols have significant anti-ageing properties, protecting against various age-related conditions, including cardiovascular disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders [

10]. Phenolic compounds confer various physiological benefits in humans, including cardioprotective and anti-inflammatory effects [

11].

Ensuring the availability of these bioactive compounds and achieving high recovery rates from any plant matrix is paramount. The extraction process plays a critical role in this, ensuring efficient acquisition of the compounds while preserving their integrity and maximising yield. It is a pivotal step in the overall process.

Traditional methods such as Soxhlet extraction, maceration, and hydro-distillation have been extensively used to extract bioactive compounds from plant materials [

12]. However, these techniques have limitations, including lengthy extraction times, the need for costly high-purity solvents, and potential degradation of heat-sensitive compounds. These limitations have prompted researchers to explore and develop alternative extraction methods that are more efficient, cost-effective, and better at preserving the integrity of delicate compounds [13, 14].

Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) is an effective method that offers significant advantages over traditional techniques. The benefits of UAE include shorter processing times, a simpler operational procedure, reduced solvent usage, lower temperatures, energy savings, and higher extraction yields [

15]. UAE enhances extraction efficiency by exploiting cavitation effects and improving mass transfer [

16].

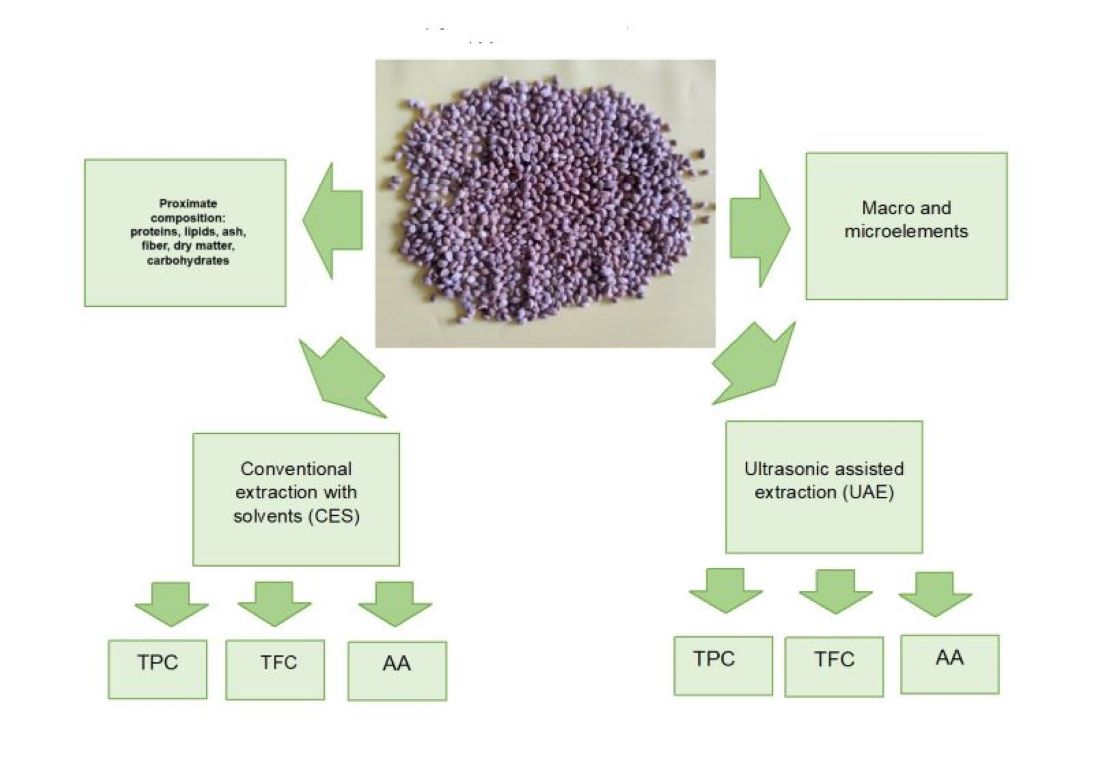

This study aims to evaluate the nutritional, phytochemical, and antioxidant activity of six varieties of dioecious hemp seeds cultivated in Romania. For this purpose, the proximate composition and content of macro and microelements in hemp seeds was determined. In addition, the impact of conventional extraction (CES) and ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) on the phytochemical profile and antioxidant activity was investigated.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

The reagents ethanol, hydrochloric acid, Folin–Ciocalteu, gallic acid and quercetin standard, 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), and ascorbic acid were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemie GmbH (München, Germany), while sodium carbonate, sodium nitrite, and aluminium chloride were purchased from Geyer GmbH (Renningen, Germany). All the reagents utilised for the chemical analysis were of analytical quality.

2.2. Plant Material

The varieties and lines were developed and are cultivated at the Lovrin Agricultural Research and Development Station located at 45°57′03″N 20°46′32″E. The hemp seed varieties analysed in this study were Lovrin 110 (HSLO), Silvana (HSSI), Armanca (HSAR), and Teodora (HSTE), while LV 585 (HSLV585) and LV 300 (HSLV300) are lines in the process of being certified. Before all analyses, the hemp seed was ground with a Grindomix GM200 mill and used immediately.

2.3. Determination of Proximate Composition and Energetical Values

The proximate chemical analysis of the hemp seed samples aligned with standardised methodologies established by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC) [

17]. Specifically, moisture content was determined using method 930.15, while ash content was analysed using method 942.05. The crude protein content was measured by applying the Kjeldahl technique, as outlined in method number 2001.11, utilising a Kjeltec system (Velp, Padua, Italy) for accuracy. Method number 978.10 was used to assess crude fibre, with measurements taken via the Fibertec™ 2010 system (Foss, Padua, Italy). Lipid content was evaluated using method 920.39 through the Soxtest Extraction Systems (Raypa SX-6 MP). The carbohydrate content was not directly measured but instead calculated by subtracting the total percentages of moisture, lipids, proteins, and ash from 100%. Additionally, the caloric or energy value of the samples was computed following the procedure detailed by Das P. C. et al. [

18]. This method utilised Equation (1), applying the caloric conversion factors where each gram of carbohydrates contributes four calories, each gram of protein provides four calories, and each gram of fat supplies nine calories.

2.4. The Preparation of Plant Extracts

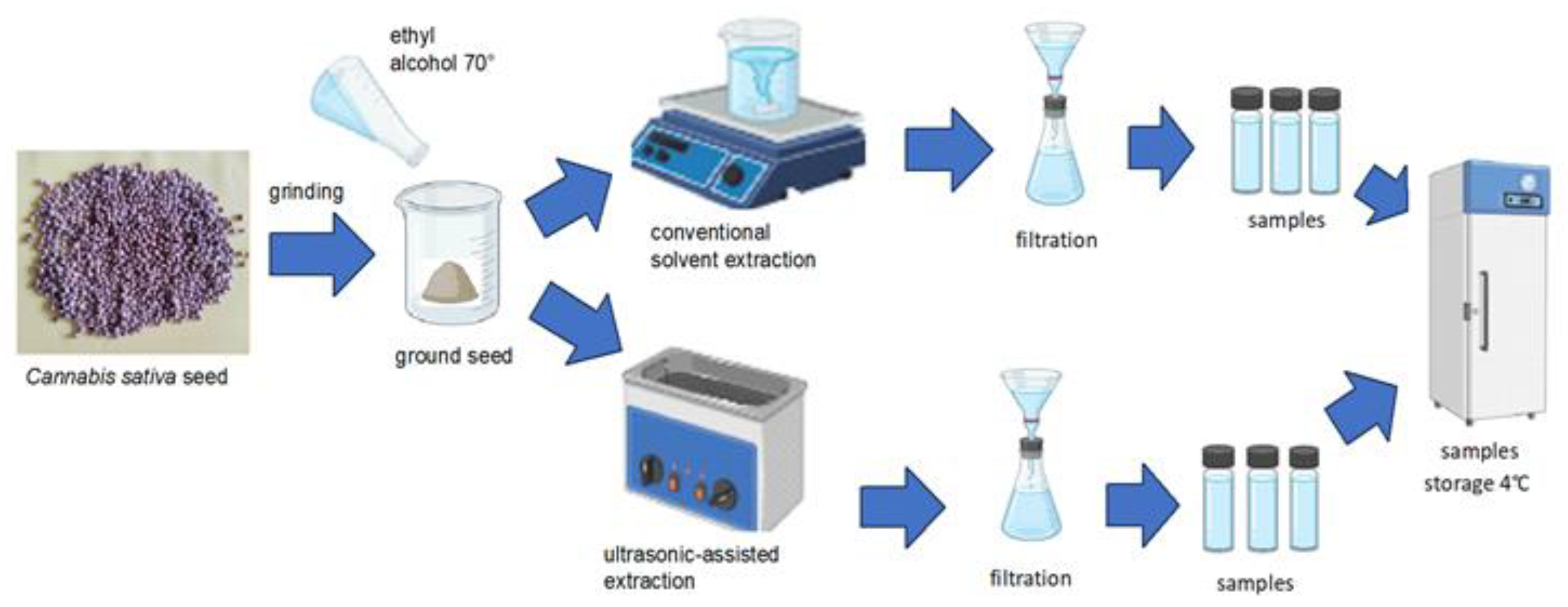

The ground seeds of each variety were mixed with a 70% alcohol solution to prepare the sample for extraction. Subsequently, the mixture was subjected to two distinct extraction techniques: the traditional conventional extraction method (CES) and an alternative approach utilising ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE).

2.4.1. Conventional Extraction with Solvents (CES)

The sample (1.0 g) was subjected to extraction with 10 mL of 70% ethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) using a Holt plate stirrer (IDL, Freising, Germany) for 60 minutes. After extraction, the mixture was filtered through filter paper and stored at 4° C until analysis.

2.4.2. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction (UAE)

A 1.0 g sample was combined with 10 mL of 70% ethanol and subjected to extraction in an ultrasonic water bath (FALC Instruments, Treviglio, Italy). The process was conducted at room temperature for 30 minutes, with the ultrasonic bath set to a power of 216 watts and a frequency of 40 kHz. After extraction, the mixture was filtered through filter paper and stored at 4° C for subsequent analysis.

2.5. Macro and Microelements Determination

The macro- and microelement composition of Cannabis sativa seeds was analysed following calcination of the sample at 800°C in a kiln (SLN 53 STD, POL-EKO-Aparatura SP, Wodzislaw, Poland) and subsequent extraction using 20% hydrochloric acid (HCl) (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany). Atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) was employed to quantify these elements. Details of the identification and quantification procedure are provided by Dossa et al. [

19]. The results are presented in µg/g; each experiment was conducted in triplicate.

2.6. Antioxidant Profile

2.6.1. Determination of Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

The Folin–Ciocalteu assay measured twelve hemp seed extracts' total polyphenol content (TPC). For each extract, 0.5 mL was sampled as previously prepared and then mixed with 1.25 mL of Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (diluted 1:10 in water), which was sourced from Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany. The mixture was then permitted to stand at room temperature for five minutes, after which 1 mL of Na₂CO₃ containing 6% (Geyer GmbH, Renningen, Germany) was added. Subsequently, each prepared sample was incubated in a Memmert INB500 thermostat (Schwabach, Germany) at 50 °C for 30 minutes. Following incubation, the absorbance was determined at 750 nm using a Specord 205 UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany). Each sample was analysed in triplicate, and the results were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) in mg GAE/ kg [

20]. A calibration curve was constructed with gallic acid as the standard, in the 0–200 µg/mL range, and the calibration equation was y = 0.0174x + 0.0354 (R

2= 0.9986).

To compare the TPC content obtained through the two extraction methods, UAE and CES, the following indicator was used:

where:

TPC UAE — TPC of the UAE sample (mg GAE/Kg)

TPC CES — TPC of the CES sample (mg GAE/Kg)

2.6.2. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The total flavonoid content was determined by the methodology proposed by Cocan et al. [

21] Precisely, 1 mL of the extract was placed into a test tube, followed by adding 0.3 mL of a 5% NaNO₂ (Geyer GmbH, Renningen, Germany) solution and 0.3 mL of a 10% AlCl₃ (Geyer GmbH, Renningen, Germany) solution. The mixture was then left to stand at room temperature for 6 minutes, after which 2 mL of 1 M NaOH (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany) solution was added, and the final volume was adjusted to 10 mL with 70% ethanol. After an additional 15-minute rest at room temperature, the absorbance of the solution was measured at 415 nm using a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Specord 205; Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany), with 70% ethanol as the reference. The analysis was conducted in triplicate, and the results were reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) in mg QUE/100 g. A calibration curve was prepared using quercetin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany) in a 0–500 μg/mL concentration range, and the calibration equation was y = 0.0013x + 0.0081 (R

2= 0.9955).

To compare the TFC content obtained through the two extraction methods, UAE and CES, the following indicator was used:

where:

TFC UAE — TFC of the UAE sample (mg GAE/Kg)

TFC CES — TFC of the CES sample (mg GAE/Kg)

2.6.3. Antioxidant Capacity by 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Assay

A 0.1 mM solution of 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany) in ethanol was prepared to evaluate antioxidant activity. 1 mL of the extract was combined with 2.5 mL of the DPPH solution, and the mixture was shaken thoroughly before being incubated in darkness at room temperature for 30 minutes. After incubation, absorbance was measured at 518 nm with a UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Specord 205; Analytik Jena AG, Jena, Germany). A 70% ethanol solution served as the control. Each sample was analysed in triplicate, and the average result was recorded. The antioxidant capacity was quantified as the percentage of radical scavenging activity (RSA) using the formula:

where: A

c = absorbance value of the control sample,

A s = absorbance value of the extract sample.

The antioxidant capacity was expressed as the IC50 value and compared to ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Munich, Germany)

To compare the RSA content obtained through the two extraction methods, UAE and CES, the following indicator was used:

where:

RSA UAE — RSA of the UAE sample (mg GAE/Kg)

RSA CES — RSA of the CES sample (mg GAE/Kg)

2.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using JASP 0.19. Descriptive statistics, including mean and standard deviation, were calculated to evaluate the study data. Group comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Tukey test for post hoc analysis. The threshold for statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Principal component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was performed for dimensionality reduction to provide a concise and optimal description of the data, using OriginPro 2025.

3. Results

3.1. Determination of the Proximate Composition of Hemp Seed Varieties

Table 1 comprehensively summarises the variability in moisture content, protein, mineral, lipid, fibre, and carbohydrate composition across various hemp seed samples.

The moisture content across the samples ranged from 4.84 ± 0.06% in HSLO to 5.96 ± 0.04% in HSSI, with an average of approximately 5.50%. Ash, representing the total mineral content, averaged 5.21% across the samples, with HSTE having the lowest (4.71 ± 0.04%) and HSLV585 the highest (6.38 ± 0.03%). The highest protein content was found in HSLV585 at 25.39 ± 0.03%, while HSAR had the lowest at 20.93 ± 0.03%. The average protein content was 22.31%.

Each sample demonstrated notably high lipid content. HSSI had the highest lipid concentration at 28.43 ± 0.05 g/100 g, while HSTE had the lowest at 24.92 ± 0.07 g/100 g. The mean lipid concentration was 27.17 g/100 g.

Fiber content varied considerably, from 25.92 ± 0.08 g/100 g in HSLV300 to 31.21 ± 0.04 g/100 g in HSTE, with an average of 28.52 g/100 g.

Total carbohydrates were calculated by subtracting moisture, protein, lipid, and mineral contents from 100%. Carbohydrate levels ranged from 35.05 ± 0.06% in HSLV585 to 43.58 ± 0.07% in HSTE.

Finally, the energy content, derived from carbohydrates, lipids, and proteins, showed that HSLO had the highest energy value at 502.40 ± 0.12 kcal per 100 g, while HSTE had the lowest at 483.25 ± 0.05 kcal per 100 g.

3.2. Macro and Microelements Composition of Hemp Seed Varieties

The experimental results of the mineral composition, as shown in

Table 2, show that potassium was the macronutrient with the highest concentration in the analysed seed samples, following magnesium and calcium. Potassium, calcium, and magnesium contribute to the development of vital cellular functions, particularly in relation to the heart's excitability. They are key elements in the movement of the heart muscle and the activation of enzyme systems [

22].

The potassium content across the samples ranged from 5533.20 μg/g in sample HSLV300 to 3743.08 μg/g in sample HSSI, with an average of 4391.95 μg/g reported in all analyzed samples. Among the certified and traditionally grown varieties in Romania, HSLO stood out with a potassium content of 5000.95 μg/g, while the other three varieties had similar potassium levels. Both varieties undergoing certification also exhibited high potassium content.

Magnesium is the next prevalent macro element in the analyzed hemp seeds. The magnesium content ranged from 1969.9 μg/g in sample HSSI to 2616.3 μg/g in sample HSLV585. Calcium content in the analyzed samples varied between 1161.2 μg/g in sample HSLV585 and 1853.51 μg/g in sample HSLO, with no significant differences (p >0.05) between samples HSLV585 and HSSI.

Among the varieties, HSLO had the highest quantities of potassium, calcium, and magnesium, followed by the varieties undergoing certification, which had high potassium and magnesium levels but lower calcium content compared to the already cultivated varieties.

Among the microelements listed in

Table 2, iron was found in the highest concentrations in all hemp resources, followed by manganese, zinc, and copper, while nickel and cadmium were present in lower amounts.

The iron content across the samples ranged from 96.94 μg/g in sample HSTE to 189.49 μg/g in sample HSLV585, with an average of 136.39 μg/g reported in all analyzed samples. The current research revealed significant variation in zinc concentrations across various hemp varieties, with values fluctuating between 39.88 μg/g and 75.25 μg/g. Similarly, the copper concentrations ranged from 9.29 μg/g in sample HSLV300 to 13.08 μg/g in sample HSTE. No statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were found between the zinc content of samples HSLV300 and HSSI and between samples HSLO and HSAR.

The manganese content in the analyzed samples ranged from 87.70 μg/g in sample HSTE to 138.26 μg/g in sample HSLV585, with an average of 107.59 μg/g reported in all analyzed samples. Nickel, which typically occurs naturally in soil at low concentrations, was found in the samples at levels ranging from 0.17 μg/g to 2.82 μg/g, with an average of 1.34 μg/g. No significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between samples HSLO and HSTE.

The mean cadmium concentration in the analyzed samples was 0.077 μg/g, with a minimum of 0.041 μg/g in sample HSLO and a maximum of 0.092 μg/g in sample HSLV300. No statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between samples HSSI, HSAR, HSTE, and HSLV585.

3.3. Antioxidant Profile

3.3.1. Determination of Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

Hemp seeds are abundant in phenolic compounds, recognized for their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory benefits.

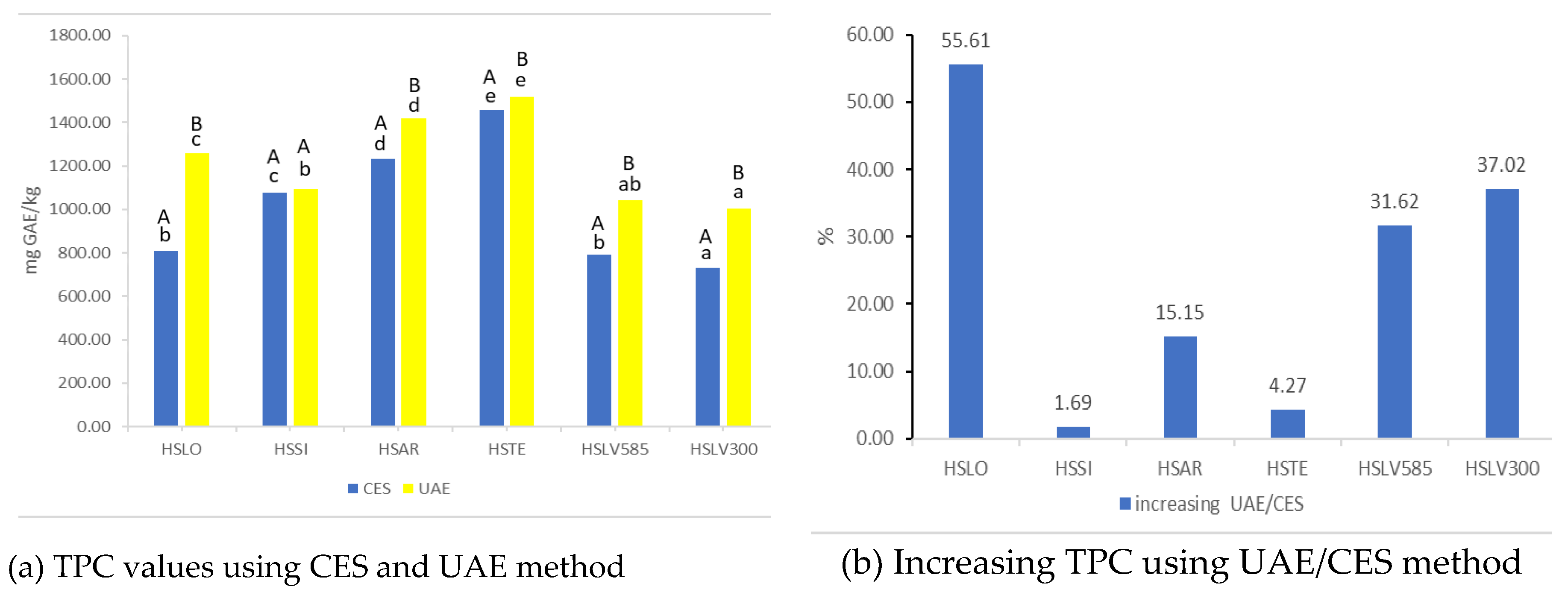

Figure 1 demonstrates the Total Phenolic Content (TPC) for samples processed using CES and UAE methods.

Figure 1a shows TPC values derived from CES and UAE methods, expressed in mg GAE/kg.

Figure 1b illustrates the percentage change in TPC after different sample preparations, calculated using Equation (2).

According to the findings for CES (

Figure 1a), the Total Phenolic Content (TPC) values ranged from 732.36 to 1457.60 mg GAE/kg. In comparison, UAE results showed TPC values ranging from 1003.48 to 1519.87 mg GAE/kg. For CES extraction, no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were found between samples HSLV585 and HSLO. In the case of UAE extraction, no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between samples HSSI and HSLV585, as well as HSLV585 and HSLV300. Additionally, sample HSSI showed no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) in polyphenol content when comparing the two extraction methods, CES and UAE.

A notable increase in TPC was observed following UAE extraction compared to CES extraction (

Figure 1b). The maximum increase was for the HSLO extract (55.61%), while the minimum was for the HSSI extract (1.69%).

3.3.2. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The antioxidant capacity of flavonoids is influenced by their molecular structure, specifically the number and position of hydroxyl (–OH) groups, the effects of conjugation and resonance, the surrounding environment that affects the preferred antioxidant site, and the specific antioxidant mechanism of each compound [

23].

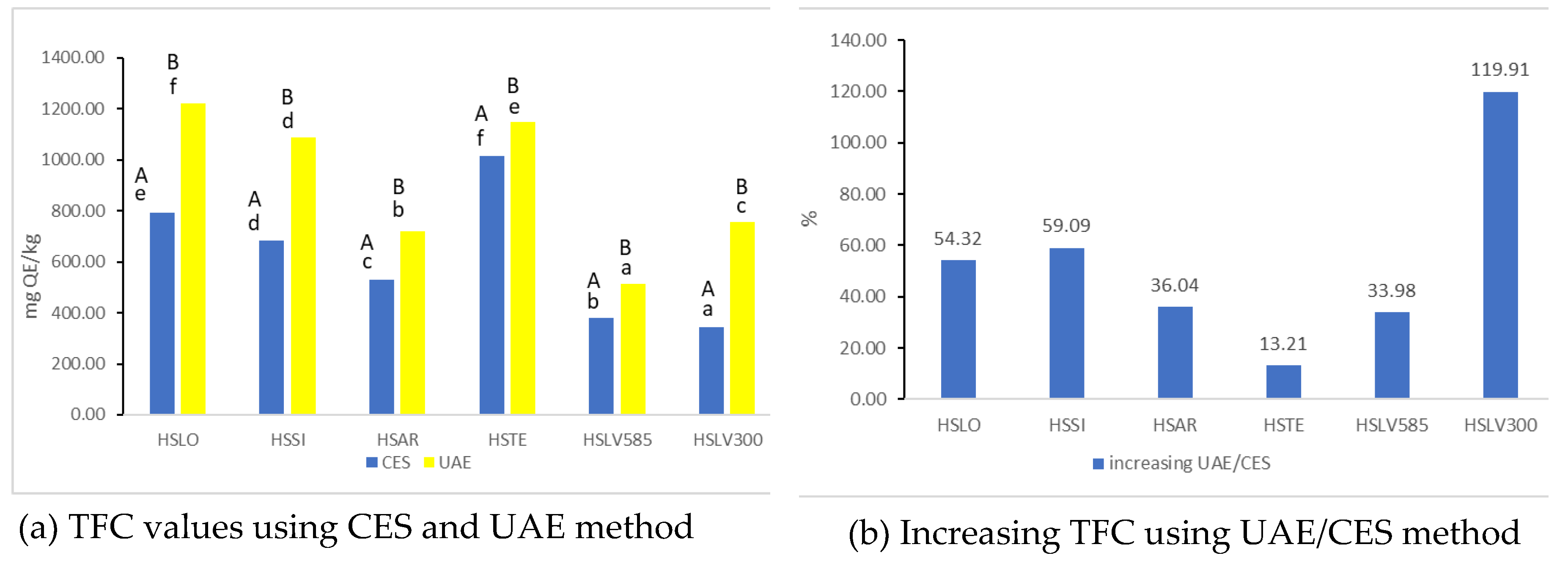

Figure 2 presents the Total Flavonoid Content (TFC) for samples processed using CES and UAE methods.

Figure 2a shows TFC values obtained from CES and UAE methods, expressed as mg QE/kg.

Figure 2b illustrates the percentage variation in TFC following different sample preparations, calculated using Equation (3).

TFC levels ranged from 343.91 to 1013.40 mg QE/kg in samples extracted via the CES method, and from 511.92 to 1222.14 mg QE/kg in those obtained using the UAE method. The highest flavonoid content for the CES procedure was observed in HSLO and HSTE extracts, while for the UAE process, the highest values were noted in HSTE and HSLO extracts. Statistical analysis showed significant differences (p < 0.05) between samples extracted using CES and UAE methods. A significant increase in TFC was observed with the UAE method compared to CES (

Figure 2b), with the most substantial increase in the HSLV300 extract (119.91%) and the smallest increase in the HSTE extract (13.21%).

3.3.3. Antioxidant Capacity by 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Assay

To assess the radical scavenging activity using the DPPH method, five concentrations of each extract were prepared: 100.00 mg/mL, 40 mg/mL, 20 mg/mL, 13.33 mg/mL, and 5 mg/mL for the twelve tested samples. Simultaneously, the antioxidant activity of five ascorbic acid solutions at various concentrations (0.02–0.1 mg/mL) was measured as a positive control, with the highest concentration (0.1 mg/mL) showing 91.45% inhibition (

Table 3). The IC

50, which represents the concentration needed for each extract to achieve 50% inhibition of DPPH, was calculated, and expressed in mg/mL (

Table 4).

As shown in

Table 3, the highest radical scavenging activity was observed at the maximum concentration (100 mg/mL) for all samples. For the conventional extraction method, the highest antioxidant activity was found in the HSTE extract (56.6%), followed by HSAR (48.28%) and HSLO (45.21%). The lowest radical scavenging activity was seen in HSLV300 (38.01%), followed by HSLV585 (33.54%) and HSSI (32.90%).

For the ultrasound extraction method, the HSTE extract exhibited the highest antioxidant activity (60.48%), followed by HSLO (54.20%), HSAR (51.74%), and HSLV300 (47.62%). HSSI (42.80%) and HSLV585 (39.41%) had the lowest radical scavenging activity.

Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were found in most samples extracted using the conventional method across all tested concentrations. However, exceptions included HSSI and HSAR, which did not show significant differences (p > 0.05) at a concentration of 5 mg/mL; HSLO and HSSI, which showed no significant differences at 13.33 mg/mL; and HSAR and HSLV300, which exhibited no significant differences at 20 mg/mL.

No statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between HSAR and HSTE, and between HSLV585 and HSLV300 in the ultrasonic extraction at a 5 mg/mL concentration. Additionally, at a concentration of 13.33 mg/mL, no statistically significant differences (p > 0.05) were observed between HSLO and HSLV585.

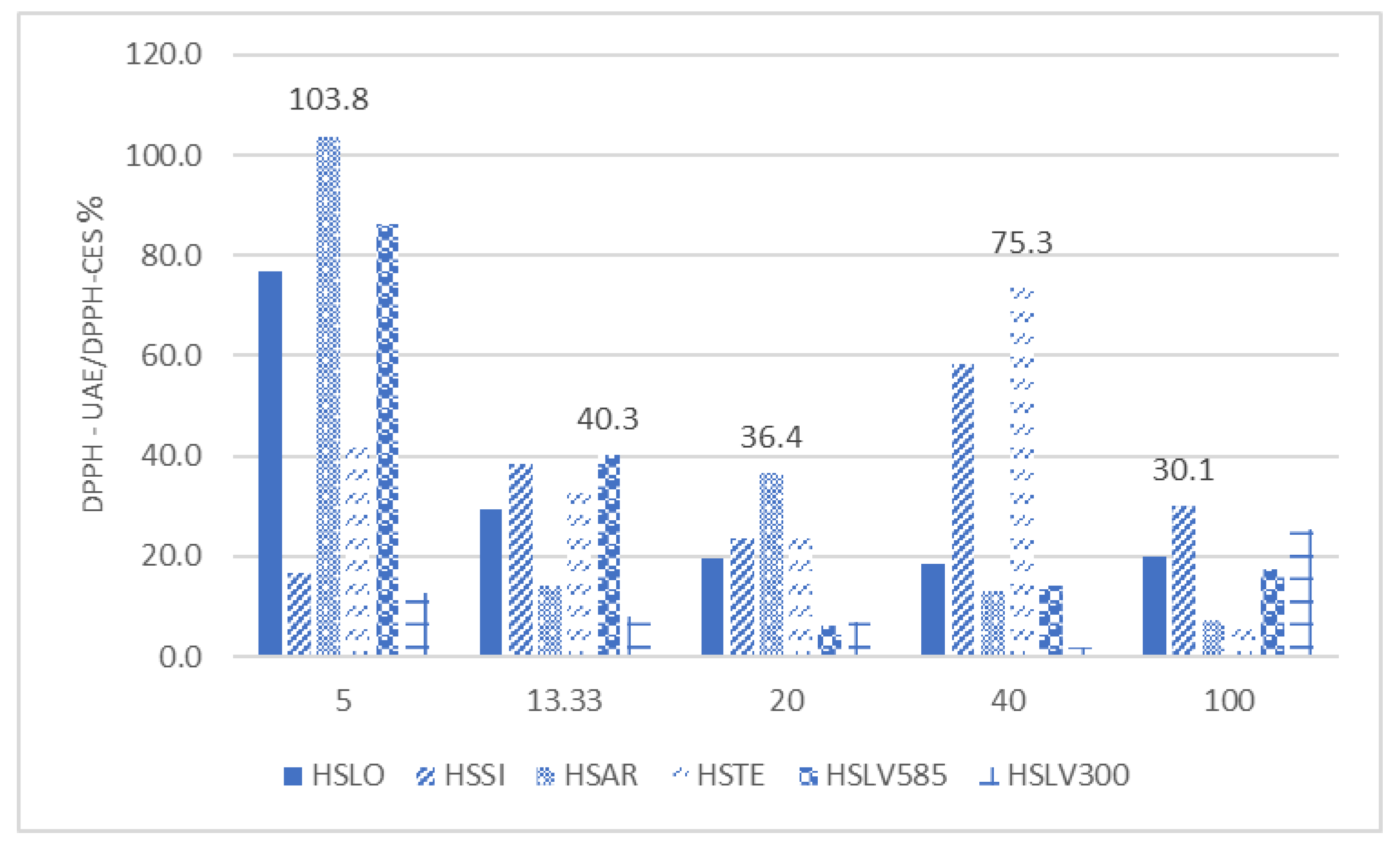

Regarding the influence of the extraction technique,

Figure 3 shows that ultrasound-assisted extraction (DPPH – UAE) led to increases in DPPH values ranging from 1.72% to 103.77%, compared to the values obtained using the conventional extraction method (DPPH – CES).

Table 4 shows that the highest antioxidant activity was achieved for all samples during the UAE process, followed by the CES process. Significant differences were observed between the two methods across all analyzed samples. For the UAE method, the IC

50 values of the samples varied significantly, highlighting differences in their antioxidant efficacy. Sample HSTE exhibited the highest antioxidant activity with an IC

50 value of 4.85 mg/mL, while sample HSLV585 had the lowest activity with an IC

50 value of 7.50 mg/mL. Most hemp seeds analyzed showed significant differences (p < 0.05), except for sample HSLO, which was paired with sample HSAR.

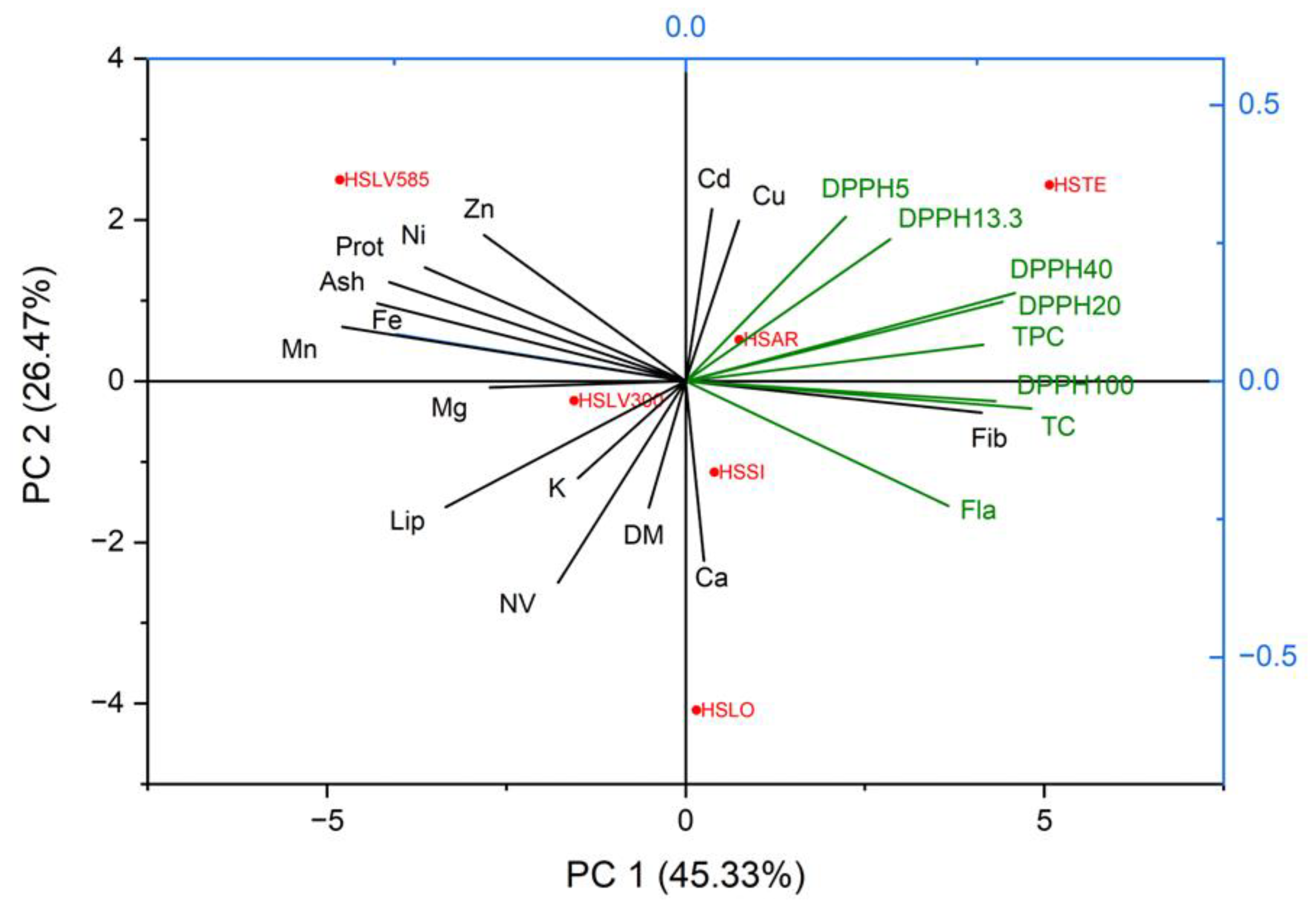

Based on the values obtained for the Eigenvalue, 3 principal components were selected. PC1 – contributing with 45.33% of the total variance, is strongly correlated with antioxidant activity at extract solution concentrations of 20, 40, and 100, and TC. PC2 accounts for the next 26.47% and is correlated with the content of Cd and Cu, as well as antioxidant activity at a concentration of 5 of the extract solution. PC3 (14.48%) is correlated with the content of Ca and DM.

Analysing the boxplot in the figure, it is observed that the HSTE variety is characterised by high values of antioxidant activity (DPPH20, DPPH40, DPPH100) and TC, HSLV – high content of ash, protein, Zn, Fe, Mn, and Ni, while HSLO has a high content of Ca and DM.

4. Discussion

4.1. Proximate Composition of Hemp Seeds

According to Leonard et al. and El-Sohaimy et al., hemp seeds have a proximate composition of 18–23% protein, 25–30% oil, 30–40% fiber, and 6–7% moisture [6, 24]. The moisture content obtained aligns with findings from other studies. Allonso-Esteban et al. [

25] reported moisture values ranging between 4.53 and 7.06 g/100g for eight hemp varieties, while Siano et al. found a moisture content of 7.3% in Fedora cultivar seeds [

7]. Rosso et al. noted moisture content from 6.54% to 7.9% in three different hemp varieties cultivated in Central Italy [

26]. These variations could be attributed to environmental and storage conditions, particularly temperature.

The ash content is consistent with Vonapartis et al. [

8], who observed ash values ranging from 5.1 to 5.8 g per 100 g in ten different hemp cultivars, and with Siano et al., who reported 5.3 g per 100 g in Fedora seeds [

7]. Similar results were obtained by Arango et al. (2024), with ash values between 4.40 and 7.49% in 29 hemp varieties [

27].

Hemp seed proteins are mainly storage proteins, with albumin accounting for 25%−37% and the legumin protein edestin for 67%−75% [

28]. These proteins make hemp seeds particularly beneficial for vegetarian diets. Our results regarding the protein content of hemp seeds are consistent with other findings. Oseyko et al. [

29] reported protein content of 22.5% in hemp seeds, while Siano and colleagues found 24.8% [

7]. House et al. observed protein content ranging from 21.3 to 27.5 mg/100g across 30 hemp seed samples [

9]. Hemp proteins are primarily located in the internal layer of the seed, with minimal quantities in the hull [

10].

The lipid composition of the analyzed hemp seed varieties aligns closely with existing research. Siano et al. reported a lipid content of 24.5%, House et al. found 25.4–33.0 mg per 100 g, and Vonapartis et al. observed 26.9 to 30.6 mg per 100 g [7, 9, 8]. Rosso et al. found crude fiber content varying between 20.98 and 25.58 g/100g [

26].

Reduced carbohydrate content in the improved samples suggests potential hypoglycemic benefits and suitability for diabetic-friendly diets. Siano et al. found a carbohydrate prevalence of 38.1% [

7]. Callaway et al. [

5] reported 27.6 g per 100 g in Finola hemp seeds, while Mattila et al. found carbohydrate content comparable to flaxseed (34.4 ± 1.5 g/100 g vs. 29.2 ± 2.5 g/100 g) [

30]. Mattila et al. also reported an energy value of 2301 kJ/100 g dw for hemp seeds [

30].

Observed differences in chemical composition can be attributed to environmental conditions, soil characteristics, agricultural practices, and natural botanical variation.

4.2. Macro and Micronutrients Composition of Hemp Seed Varieties

Due to the different hemp varieties analyzed across various studies, comparing mineral content results can be challenging. Our findings on potassium levels in hemp seeds surpass those reported by Siano [

7] but are lower than those obtained by other researchers studying macro elements in hemp seeds [5, 30, 31, 32,25]. Magnesium is an essential mineral crucial for activating numerous biochemical processes vital to human health [

33] content in certain hemp seeds ranges from 240 mg/100 g [

29] to 694 mg/100 g [

31], which exceeds the values obtained in our study. Calcium levels reported in prior research vary from 90 mg/100 g [

29], 94 mg/100 g [

7], 94-121 mg/100 g [

32], 127 mg/100 g [

30], 145 mg/100 g [

5], to 175.6 mg/100 g [

25], aligning with our findings.

Iron is essential in the human diet for hemoglobin production. However, inorganic iron, commonly found in plant-based foods, is less readily absorbed by the body compared to organic (heme) iron present in animal products [

34]. Consequently, vegetarians are advised to increase their iron intake by up to 80% above the recommended levels to compensate for the lower bioavailability of plant-based iron [

35]. Reported iron concentrations in hemp seeds show significant variation in the literature [5, 7]. High values of up to 240 mg/100 g have been associated with iron-rich soils used in experimental hemp cultivation [

36].

Typical zinc levels in hemp seeds range from 4 to 7 mg per 100 grams, as documented by Mihoc, Oseyko, and Mattila [29, 30, 36]. Copper concentrations in hemp seeds span from 0.5 mg to 2 mg per 100 grams, according to Siano and Callaway [

7,

5]. Our study's results for both zinc and copper are consistent with these previous findings.

Manganese concentrations in earlier studies vary from 6 mg/100 g [

29] to 12-15 mg/100 g [

32], which matches our results. In their research on heavy metal and micronutrient content in hemp seeds from northwest Turkey, Korkmaz and colleagues reported nickel content between 0.36 and 1.66 mg/kg, comparable to our findings [

37]. Mihoc reported higher micronutrient values of 1.6 to 6.1 mg/kg in hemp seeds, exceeding our study's results [

36].

Cadmium, a heavy metal present in soil, poses significant environmental and health risks due to its toxicity and plant absorption ease. The EU limits cadmium levels in seeds used for oil production and cereals to 0.1 mg/kg [

38]. Korkmaz's study of 21 hemp seed samples from northwest Turkey revealed cadmium concentrations ranging from 0.5 to 2.3 µg/100 g, significantly higher than those in our studied hemp varieties [

37].

Mineral profiles in hemp seeds can vary significantly due to environmental conditions, soil mineral composition, fertilizer application, and plant variety. Proper fertilization and nutrient management can enhance mineral accumulation. Additionally, antagonistic interactions occur when one mineral inhibits the uptake or utilization of another, leading to deficiencies or imbalances. For instance, high levels of calcium, magnesium, and potassium can compete with iron and zinc absorption. Anti-nutrient components like phytates and oxalates in hemp seeds can also bind minerals, reducing their bioavailability [

39].

4.3. Total Polyphenols Content (TPC)

The phenolic compounds in hemp seeds are predominantly distributed among three major classes: flavonoids, stilbenes, and lignans [6, 10]. These compounds play a vital role in preventing diseases associated with oxidative stress due to their remarkable antioxidant capacity. Some specific phenolic compounds found in hemp seeds include ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, and N-trans-caffeoyltyramine [

28]. Studies have shown that the phenolic content can vary based on factors such as the geographical location where the hemp is grown and the specific hemp cultivar.

The determined values for TPC align with those documented in previous research. Siano et al. reported a TPC value of 767 mg GAE/kg for seeds in their comparative study of the chemical, biochemical, and characteristic properties of seeds, oil, and flour from the Fedora hemp cultivar [

7] Mattila and colleagues found a total phenolic content of 96 ± 35 mg GAE/100 g for whole hemp seeds [

40]. Moccia et al. reported a total polyphenol content of 0.92 ± 0.04 mg GAE/g for polar extracts from Fedora hemp seeds, flour, and oil [

41]. Frasinetti et al. documented a higher total polyphenol content of 2.33 ± 0.07 mg GAE/g dw for hemp seeds and sprouts [

42]. Similarly, Vonapartis et al. analyzed ten industrial hemp cultivars approved for cultivation in Canada, revealing TPC values from 1.37 to 5.16 mg GAE/g [

8]. Irakli and colleagues documented an average TPC of 588.8 mg GAE/100 g in their study on seven hemp seed varieties grown in Greece, which is higher than previously reported values [

43].

Polyphenol levels exhibit quantitative variation due to biotic and abiotic factors affecting their biosynthesis pathway. Ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) yields plant extracts with higher concentrations of active compounds and improved biological activity. The advantages of this method over traditional techniques are well-established.

4.4. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

Findings regarding TFC align with previously documented research in the specialist literature. In their comparative study on hemp seeds and steam, Allo et al. identified active principles and biological properties, reporting a total flavonoid content of 107.502 mg/100 g CAE [

44]. Barčauskaitė and colleagues, in their investigation of the potential for industrial hemp cultivation in the Nordic-Baltic region, reported TFC values ranging from 2.52 to 4.74 mg/g RUE [

45]. Frassinetti et al., in their study on the nutraceutical potential of hemp seeds and sprouts, reported a total flavonoid content of 2.93 ± 0.23 mg QE/g DW, which was higher than the values found in our study [

42].

4.5. Antioxidant Capacity by 1,1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

Antioxidant activity is a crucial biological property with significant implications for industries such as cosmetics, food, and beverages. Since antioxidant potential is vital for determining the therapeutic benefits of plants, this study employed antioxidant assays, specifically the radical scavenging (DPPH) method. This assay is favoured for its simplicity, speed, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness, making it an ideal tool for evaluating plant antioxidant activity.

Our study's findings on DPPH radical scavenging activity are consistent with those reported in the literature. Siano et al. observed a DPPH free radical scavenging activity value of 51.5% for hemp seed extracts [

7]. Frasinetti et al. reported the antioxidant activity of hemp seeds as 40 ± 2% DPPH inhibition [

42].

Judžentienė et al., in their study on the chemical composition and antioxidant activity of various hemp parts cultivated in Lithuania, reported a DPPH radical scavenging activity Trolox value of 1.556 ± 0.004 mmol/L for seed extracts [

46].

In another study by Babiker E. et al., the effects of different roasting durations (7, 14, and 21 minutes) at 160 °C on the proximate composition, color properties, bioactive compounds, and fatty acid profile of hemp seeds were examined. The DPPH scavenging activity of unroasted seeds was 18.37%, which significantly decreased to 6.65% and 10.99% for seeds roasted for 7 and 14 minutes, respectively. Interestingly, the antioxidant activity of the seeds significantly increased with longer roasting times, reaching 33.08% after 21 minutes [

47].

The findings related to the extraction method are consistent with the literature. In a study by Szydłowska-Czerniak, A. et al., two extraction methods were used to obtain total antioxidants from winter and spring rapeseed cultivars: ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) and conventional solid-liquid extraction. The researchers found that rapeseed extracts obtained after 18 minutes of ultrasonication had the highest levels of total antioxidants, indicating that UAE is more effective than traditional extraction techniques in extracting antioxidant compounds [

48].

Regarding IC

50 values, Benkirane et al. reported IC

50 values ranging from 1.64 to 4.37 mg/mL for the DPPH test for two hempseed varieties collected from four different Moroccan regions [

49]. Chen et al. extracted forty samples from defatted kernels and hulls of two hempseed varieties using ten polar solvent systems, reporting IC

50 values ranging from 0.58-4.55 mg/mL for defatted kernels and 0.09-2.21 mg/mL for hulls [

50].

Manosroi and colleagues evaluated the antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from Thailand's hemp seeds, finding that the extract had an IC

50 value of 14.39 mg/mL in the DPPH free radical scavenging assay [

51].

Alonso-Esteban et al. studied the chemical composition and biological activity of eight varieties of hemp seeds, both hulled and dehulled, reporting DPPH test (EC

50) antioxidant activity ranging from 2.5 to 9.2 mg/mL for hulled seeds [

25].

Additionally, Rosso et al. examined three distinct varieties of hemp seeds grown in a Mediterranean area, reporting DPPH test (EC

50) antioxidant activity ranging from 0.06 to 0.13 mg/mL [

26].

5. Conclusions

Due to their high nutritional properties and support from numerous recent studies, hemp seeds are increasingly being incorporated into various food products and are emerging as a significant alternative in the food and nutraceutical industry. They are packed with antioxidants, including a diverse range of phenolic compounds that inhibit lipid oxidation by preventing radical reactions, thus protecting products from degradation. Although many studies have been conducted on the nutritional value and antioxidant capacity of hemp seeds, comparisons can be challenging because these studies often focus on regional hemp varieties. Additionally, the results can vary widely due to environmental factors, soil mineral content, plant variety and the application of fertilizers. Our study reveals that Romanian hemp varieties contain approximately 20-25% easily digestible protein, 35-43% carbohydrates, 25-31% fibre, and several biologically important minerals. When examining the influence of the extraction technique, our findings indicate that ultrasound-assisted extraction resulted in increased TPC, TFC, and DPPH values compared to the conventional extraction method. PCA analysis demonstrates that the HSTE variety is characterized by high antioxidant activity (DPPH20, DPPH40, DPPH100) and TC. HSLV shows a high content of ash, protein, Zn, Fe, Mn, and Ni, while HSLO has a high content of Ca and DM. The higher antioxidant compounds and, consequently, the higher antioxidant capacity of hemp seeds obtained using the UAE method compared to the CES method is of significant interest to the food and pharmaceutical industries, as it reduces extraction times and solvent quantities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.F.(O). and I.R.; methodology, D.O., A.H. and I.H.; software, D.F.(O).and A.B..; validation, I.R., D.F.(O). and C.B.; formal analysis, L.A.S, A.O.P.; investigation, D.F.(O).; data curation, I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.F.(O).; writing—review and editing, A.B.; visualization, I.H.; supervision, I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquires can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

This paper is published from the project CNFIS-FDI-2024-F-0351 of the University of Life Sciences “King Mihai I” from Timisoara, financed by Romanian National Council for Higher Education Financing. The researches were supported during the Research project no.8662/20.12.2018.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- McPartland, J.M. Cannabis Systematics at the Levels of Family, Genus, and Species. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2018, 3, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McPartland, J.M.; Hegman, W.; Long, T. Cannabis in Asia: Its center of origin and early cultivation, based on a synthesis of subfossil pollen and archaeobotanical studies. Veg. Hist. Archaeobotany 2019, 28, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupasinghe, H.P.V.; Davis, A.; Kumar, S.K.; Murray, B.; Zheljazkov, V.D. Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa Subsp. Sativa) as an Emerging Source for Value-Added Functional Food Ingredients and Nutraceuticals. Molecules 2020, 25, 4078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.; Fahad, S.; Du, G.; Cheng, X.; Yang, Y.; Tang, K.; Liu, L.; Liu, F.-H.; Deng, G. Evaluation of Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) as an Industrial Crop: A Review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 52832–52843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callaway, J.C. Hempseed as a nutritional resource: An overview. Euphytica 2004, 140, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, W.; Zhang, P.; Ying, D.; Fang, Z. Hempseed in Food Industry: Nutritional Value, Health Benefits, and Industrial Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2020, 19, 282–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siano, F.; Moccia, S.; Picariello, G.; Russo, G.L.; Sorrentino, G.; Di Stasio, M.; La Cara, F.; Volpe, M.G. Comparative Study of Chemical, Biochemical Characteristic and ATR-FTIR Analysis of Seeds, Oil and Flour of the Edible Fedora Cultivar Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.). Molecules 2019, 24, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonapartis, E.; Aubin, M.-P.; Seguin, P.; Mustafa, A.F.; Charron, J.-B. Seed Composition of Ten Industrial Hemp Cultivars Approved for Production in Canada. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2015, 39, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- House, J.D.; Neufeld, J.; Leson, G. Evaluating the Quality of Protein from Hemp Seed (Cannabis sativa L.) Products Through the use of the Protein Digestibility-Corrected Amino Acid Score Method. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010, 58, 11801–11807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinon, B.; Molinari, R.; Costantini, L.; Merendino, N. The Seed of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.): Nutritional Quality and Potential Functionality for Human Health and Nutrition. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertelli, A.; Biagi, M.; Corsini, M.; Baini, G.; Cappellucci, G.; Miraldi, E. , Polyphenols: From Theory to Practice. Foods 2021, 10(11), 2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bitwell, C.; Indra, S. S.; Luke, C.; Kakoma, M. K. , A review of modern and conventional extraction techniques and their applications for extracting phytochemicals from plants. Scientific African 2023, 19, e01585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horablaga, N.M.; Cozma, A.; Alexa, E.; Obistioiu, D.; Cocan, I.; Poiana, M.-A.; Lalescu, D.; Pop, G.; Imbrea, I.M.; Buzna, C. Influence of Sample Preparation/Extraction Method on the Phytochemical Profile and Antimicrobial Activities of 12 Commonly Consumed Medicinal Plants in Romania. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floares, D.; Cocan, I.; Alexa, E.; Poiana, M.-A.; Berbecea, A.; Boldea, M.V.; Negrea, M.; Obistioiu, D.; Radulov, I. Influence of Extraction Methods on the Phytochemical Profile of Sambucus nigra L. Agronomy 2023, 13, 3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xiong, X.; Huang, G. , Ultrasound-assisted extraction and analysis of maidenhairtree polysaccharides. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 95, 106395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vilkhu, K.; Mawson, R.; Simons, L.; Bates, D., Applications and opportunities for ultrasound assisted extraction in the food industry — A review. Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies 2008, 9 (2), 161-169.

- AOAC. Official Methods of Analysis of Association of Official Analytical Chemists International, 21st ed.; AOAC: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Das, P.C.; Khan, M.J.; Rahman, M.S.; Majumder, S.; Islam, M.N. Comparison of the physico-chemical and functional properties of mango kernel flour with wheat flour and development of mango kernel flour based composite cakes. NFS J. 2019, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, S.; Dragomir, C.; Plustea, L.; Dinulescu, C.; Cocan, I.; Negrea, M.; Berbecea, A.; Alexa, E.; Rivis, A. Gluten-Free Cookies Enriched with Baobab Flour (Adansonia digitata L.) and Buckwheat Flour (Fagopyrum esculentum). Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 12908.

- Obistioiu, D.; Cocan, I.; Tîrziu, E.; Herman, V.; Negrea, M.; Cucerzan, A.; Neacsu, A.-G.; Cozma, A. L.; Nichita, I.; Hulea, A.; Radulov, I.; Alexa, E. , Phytochemical Profile and Microbiological Activity of Some Plants Belonging to the Fabaceae Family. Antibiotics 2021, 10(6), 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cocan, I.; Cadariu, A.-I.; Negrea, M.; Alexa, E.; Obistioiu, D.; Radulov, I.; Poiana, M.-A. Investigating the Antioxidant Potential of Bell Pepper Processing By-Products for the Development of Value-Added Sausage Formulations. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houston, M. C.; Harper, K. J. , Potassium, magnesium, and calcium: their role in both the cause and treatment of hypertension. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension 2008, 10(7), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Munir, S.; Badshah, S. L.; Khan, N.; Ghani, L.; Poulson, B. G.; Emwas, A.-H.; Jaremko, M. , Important Flavonoids and Their Role as a Therapeutic Agent. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 25 (22), 5243.

- El-Sohaimy, S. A.; Androsova, N. V.; Toshev, A. D.; El Enshasy, H. A. , Nutritional Quality, Chemical, and Functional Characteristics of Hemp (Cannabis sativa ssp. sativa) Protein Isolate. Plants (Basel, Switzerland) 2022, 11 (21).

- Alonso-Esteban, J. I.; Torija-Isasa, M. E.; Sánchez-Mata, M. d. C., Mineral elements and related antinutrients, in whole and hulled hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2022, 109, 104516.

- Rosso, E.; Armone, R.; Costale, A.; Meineri, G.; Chiofalo, B. , Hemp Seed (Cannabis sativa L.) Varieties: Lipids Profile and Antioxidant Capacity for Monogastric Nutrition. Animals 2024, 14 (18), 2699.

- Arango, S.; Kojić, J.; Perović, L.; Đermanović, B.; Stojanov, N.; Sikora, V.; Tomičić, Z.; Raffrenato, E.; Bailoni, L. Chemical Characterization of 29 Industrial Hempseed (Cannabis sativa L.) Varieties. Foods 2024, 13, 210.

- Montero, L.; Ballesteros-Vivas, D.; Gonzalez-Barrios, A. F.; Sánchez-Camargo, A. D. P. , Hemp seeds: Nutritional value, associated bioactivities and the potential food applications in the Colombian context. Frontiers in nutrition 2022, 9, 1039180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseyko, M.; Sova, N.; Lutsenko, M.; Kalyna, V. Chemical Aspects of the Composition of Industrial Hemp Seed Products. Ukr. Food J. 2019, 8, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P.; Mäkinen, S.; Eurola, M.; Jalava, T.; Pihlava, J. M.; Hellström, J.; Pihlanto, A. , Nutritional Value of Commercial Protein-Rich Plant Products. Plant foods for human nutrition (Dordrecht, Netherlands) 2018, 73 (2), 108-115.

- Mihoc, M.; Pop, G.; Alexa, E.; Radulov, I. , Nutritive quality of romanian hemp varieties (Cannabis sativa L.) with special focus on oil and metal contents of seeds. Chemistry Central Journal 2012, 6 (1), 122.

- Lan, Y.; Zha, F.; Peckrul, A.; Hanson, B.; Johnson, B.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Genotype x Environmental Effects on Yielding Ability and Seed Chemical Composition of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Varieties Grown in North Dakota, USA. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2019, 96, 1417–1425.

- Volpe, S. L. , Magnesium in Disease Prevention and Overall Health. Advances in Nutrition 2013, 4(3), 378S–383S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piskin, E.; Cianciosi, D.; Gulec, S.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E. , Iron Absorption: Factors, Limitations, and Improvement Methods. ACS omega 2022, 7(24), 20441–20456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, A. V.; Craig, W. J.; Baines, S. K.; Posen, J. S. , Iron and vegetarian diets. Medical Journal of Australia 2013, 199 (S4), S11–S16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihoc, M.; Pop, G.; Alexa, E.; Dem, D.; Militaru, A. , Microelements distribution in whole hempseeds (Cannabis sativa L.) and in their fractions. Revista De Chimie 2013, 64 (7), 776-780.

- Korkmaz, K.; Kara, S. M.; Ozkutlu, F.; Gul, V. , Monitoring of heavy metals and selected micronutrients in hempseeds from North-western Turkey. African Journal of Agricultural Research 2010, 5(6), 463–467. [Google Scholar]

- European Union (EU). Commission Regulation (EU) 2023/2015 of 25 April 2023 on maximum levels for certain contaminants in food and repealing Regulation (EC) No 1881/2006. Available online: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2023/915/oj (accessed on 09 November 2024).

- Romero-Aguilera, F.; Alonso-Esteban, J. I.; Torija-Isasa, M. E.; Cámara, M.; Sánchez-Mata, M. C. , Improvement and Validation of Phytate Determination in Edible Seeds and Derived Products, as Mineral Complexing Activity. Food Analytical Methods 2017, 10(10), 3285–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattila, P. H.; Pihlava, J.-M.; Hellström, J.; Nurmi, M.; Eurola, M.; Mäkinen, S.; Jalava, T.; Pihlanto, A. , Contents of phytochemicals and antinutritional factors in commercial protein-rich plant products. Food Quality and Safety 2018, 2(4), 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moccia, S.; Siano, F.; Russo, G. L.; Volpe, M. G.; La Cara, F.; Pacifico, S.; Piccolella, S.; Picariello, G. , Antiproliferative and antioxidant effect of polar hemp extracts (Cannabis sativa L., Fedora cv.) in human colorectal cell lines. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2020, 71 (4), 410-423.

- Frassinetti, S.; Moccia, E.; Caltavuturo, L.; Gabriele, M.; Longo, V.; Bellani, L.; Giorgi, G.; Giorgetti, L. , Nutraceutical potential of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds and sprouts. Food Chemistry 2018, 262, 56-66.

- Irakli, M.; Tsaliki, E.; Kalivas, A.; Kleisiaris, F.; Sarrou, E.; Cook, C. M. , Effect οf Genotype and Growing Year on the Nutritional, Phytochemical, and Antioxidant Properties of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Seeds. Antioxidants (Basel, Switzerland) 2019, 8 (10).

- Aloo, S. O.; Kwame, F. O.; Oh, D.-H. , Identification of possible bioactive compounds and a comparative study on in vitro biological properties of whole hemp seed and stem. Food Bioscience 2023, 51, 102329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barčauskaitė, K.; Žydelis, R.; Ruzgas, R.; Bakšinskaitė, A.; Tilvikienė, V. , The Seeds of Industrial Hemp (Cannabis Sativa L.) a Source of Minerals and Biologically Active Compounds. Journal of Natural Fibers 2022, 19 (16), 13025-13039.

- Judžentienė, A.; Garjonytė, R.; Būdienė, J. , Phytochemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Various Extracts of Fibre Hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) Cultivated in Lithuania. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2023, 28 (13), 4928.

- Babiker, E. E.; Uslu, N.; Al Juhaimi, F.; Mohamed Ahmed, I. A.; Ghafoor, K.; Özcan, M. M.; Almusallam, I. A. , Effect of roasting on antioxidative properties, polyphenol profile and fatty acids composition of hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds. LWT 2021, 139, 110537.

- Szydłowska-Czerniak, A.; Tułodziecka, A., Antioxidant Capacity of Rapeseed Extracts Obtained by Conventional and Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction. Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society 2014, 91 (12), 2011-2019.

- Benkirane, C.; Mansouri, F.; Ben Moumen, A.; Taaifi, Y.; Melhaoui, R.; Caid, H. S.; Fauconnier, M.-L.; Elamrani, A.; Abid, M., Phenolic profiles of non-industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seed varieties collected from four different Moroccan regions. International Journal of Food Science & Technology 2023, 58 (3), 1367-1381.

- Chen, T.; He, J.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Zhang, H.; Hao, J.; Li, L., The isolation and identification of two compounds with predominant radical scavenging activity in hempseed (seed of Cannabis sativa L.). Food Chemistry 2012, 134 (2), 1030-1037.

- Manosroi, A.; Chankhampan, C.; Kietthanakorn, B.O.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Chaikul, P.; Boonpisuttinant, K.; Sainakham, M.; Manosroi, W.; Tangjai, T.; Manosroi, J. Pharmaceutical and cosmeceutical biological activities of hemp (Cannabis sativa L. var. sativa) leaf and seed extracts. Chiang Mai J. Sci. 2019, 46, 180–195. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).