1. Introduction

Nowadays, 1.2 billion people worldwide are affected by water shortage, which negatively affects their health, food, and energy [1]. Population growth, increased industrialization, and increased energy needs, on the one hand, and loss of snow melt, glacier shrinkage, and other circumstances, on the other hand, will exacerbate the situation in the coming years [2]. According to the World Water Council, the number of people affected will rise to 3.9 billion in the coming decades [3]. As one of the most promising approaches to alleviating water scarcity, desalination can increase water supply beyond what is available from the hydrological cycle. Seawater desalination provides an unlimited and stable supply of high-quality water that does not harm natural freshwater ecosystems [4]. Thus, freshwater scarcity is a pressing global problem, and desalination – the extraction of freshwater from seawater – has proven to be a critical solution. With only 2.7% of the world’s water being freshwater and only 0.3% being directly usable by humans, freshwater scarcity is a growing problem. Population growth, economic development, and increased freshwater consumption have exacerbated this problem. It is predicted that three-quarters of the world’s population will suffer from freshwater shortages by 2050 [5]. Desalination plants, which remove salt and minerals from seawater, are crucial in combating water scarcity. Over 19,000 desalination plants worldwide produce more than 100 million cubic meters of fresh water daily. These plants are primarily located in water-scarce regions with abundant energy resources, such as the United States and the Gulf States. China and India have also significantly progressed in seawater desalination research [6]. Classification of desalination technologies: thermally driven, mechanically driven, and electrically driven. Thermally driven uses heat as driving energy, i.e., multi-effect distillation and solar desalination. Mechanically driven is based on mechanical energy, such as Reverse osmosis (RO) and electrodialysis. Electrically powered uses electrical energy, including electrodialysis and capacitive deionization [7]. The challenges and gaps in desalination technology are generally related to energy consumption, high investments, environmental concerns, membrane performance, and innovative approaches. Traditional desalination technologies require significant energy input in energy consumption, resulting in high operating costs and environmental impact. However, high investments, including initial investments for desalination plants, remain challenging. The ecological challenge is that brine disposal (concentrated salt water) can harm marine ecosystems. With the latest membrane technologies, membrane performance challenges remain, including critical challenges in improving membrane permeability, boron rejection, and chlorine resistance. In addition, there are challenges in innovative approaches, where research is currently underway to develop desalination methods based on renewable energy sources such as solar and marine thermal energy [8,9].

Micro- and nanobubbles (MNBs) have emerged as powerful tools in water purification and treatment [3]. Their unique properties make them valuable for various applications. Due to their small size and large surface area, MNBs have tiny dimensions and provide a large surface area for interactions with pollutants. Additionally, MNBs have a long residence time, meaning that MNBs remain suspended in water for extended periods, extending contact time with contaminants. In addition, MNBs have high mass transfer performance, so MNBs enable efficient transfer of gases and solutes. In addition, MNBS has good zeta interface potential, where MNBs have a high surface charge, which aids particle removal. What is unique is that MNBs generate hydroxyl radicals that oxidize organic pollutants. Therefore, applications of micro- and nanobubbles play quite an essential role in flotation. MNBs improve flotation processes by binding to particles, giving them buoyancy and facilitating separation. Therefore, flotation with MNBS removes suspended solids, algae, and organic matter. Applying flotation with MNBs also improves aeration, where MNBs improve oxygen transfer efficiency in aeration systems to improve the biological treatment and oxidation of pollutants. In addition, flotation with MNBS is also used in ionization, where MNBs improve ozone dissolution, resulting in better disinfection and oxidation and effective removal of color, taste, and odor compounds. MNBs hold promise for sustainable development of seawater desalination. However, researchers continue to innovate, addressing challenges and pushing the boundaries of clean water production. [10]. The best and most practical desalination plants offer a cost-effective solution for removing suspended salt or solids from the seawater to produce potable water while being environmentally friendly. [11].

The most important phenomenon in the nanobubble flotation process is the interactions between bubbles and pollutant particles. These interactions include ion flotation for the seawater process in the exchange of ions [12] and the mechanism of ion flotation. Interestingly, nanobubbles possess several unique properties compared to MNBs, including high mass transfer [13], long-term stability [14], high zeta potential, high surface-to-volume ratio, and generation of free radicals upon collapse [15]. Due to their ability to generate highly reactive free radicals, one of the best applications of nanobubbles is the treatment of wastewater and drinking water [16]. Different types of nanobubbles have different applications. Hydrogen nanobubbles fuel mixes can further develop burning execution, contrasted, and customary gas [17]. A Nitrogen nanobubbles water expansion can upgrade the hydrolysis of waste-actuated slime and further develop methane creation during the time spent on anaerobic absorption [18]. Oxygen nanobubbles produce methane during the anaerobic assimilation of cellulose [19], and bulk carbon dioxide nanobubbles can be used in food processing [20]. Ozone micro-nanobubbles can increase ozone mass transfer to achieve high dissolved ozone concentration in the aqueous phase, prolong the reactivity of ozone in the aqueous phase, and be widely used to decompose organic contaminants [21]. The gas nanobubbles injected into the flotation tank interact with the coarse particles. The gas nanobubbles injected into the flotation tank interact with the coarse and fine particles [22]. The physiochemical phenomena for this process are presented in column flotation [23]. According to the purpose of this review article, based on their application and usefulness, flotation has been classified into different types such: e.g., ore flotation [24], cell flotation [25], dissolved air flotation [26–28], ion flotation [29,30] and nanobubble flotation [31]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there are no concerns regarding the effective application of the NB flotation column in the separation of dissolved ions and suspended solids during the seawater desalination process and also the corresponding success mechanism.

Therefore, this review aims to provide an updated analysis of nanobubbles’ interaction with seawater, including the ion interaction and the effect of gas types in the conversion of seawater to drinking water for a specific flotation column in the ion flotation perspective. This review focused on Nanobubble flotation regarding the interaction of NBs with salt ions and heavy metals in the flotation column, including ion flotation connected to ion separation, attachment, and detachment.

2. Materials and Methods

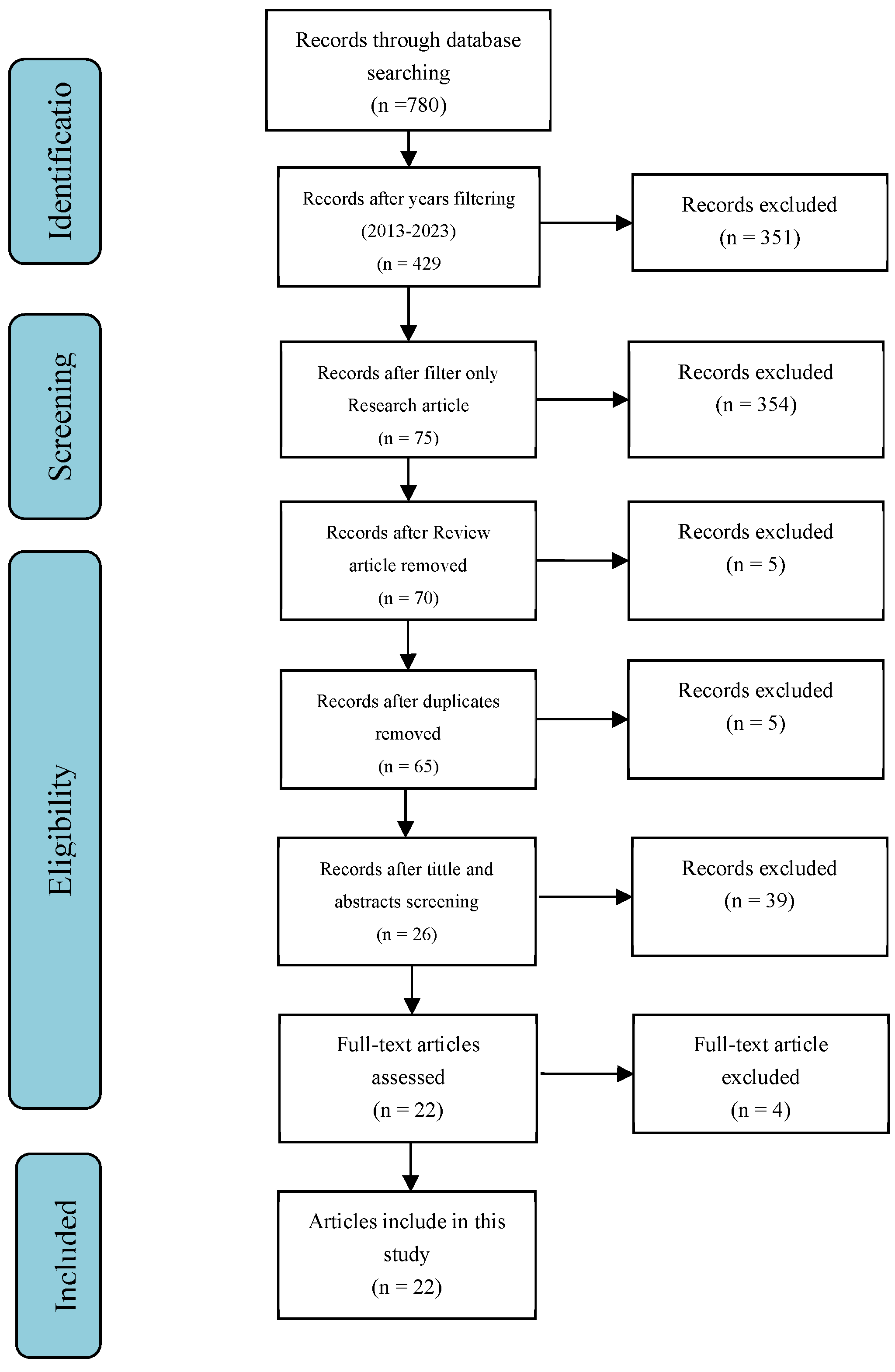

This review sought to comprehend the effects and mechanisms of NBs flotation on various gas nanobubble types used in seawater desalination for drinking water, including ion flotation, especially for application in the salt ion and heavy metals. To achieve this objective, a four-step systematic review was carried out. After locating the database in the first step, the title and abstract were used to filter the results. In addition, the selected papers in the full text were analyzed, and selecting a group of documents to include was the final step. The PRISMA guideline was also adopted during this review.

2.1. Objective

The main objective of this study was summarized in four research questions (RQ).

RQ1: What makes NBs flotation technology more useful for seawater desalination?

RQ2: How do the physical, chemical, electronic, and mechanical interactions between nanobubbles flotation with seawater?

RQ3: What does the nanobubbles technology give efficiency ion separation for seawater desalination?

RQ4: How is the mechanism of salt ion interaction with bubbles and the water quality due to the desalination process?

The research questions were used to identify some keywords. The components that make up the keywords are the bubble (and its synonyms, such as gas nanobubbles and nanobubbles), seawater, and ion flotation. Using these keywords as a search expression, the Boolean operator was created. Science Direct and Google Scholar were used for the search. From the search, 429 documents were found, as shown in

Table 1, and advanced to the screening step.

2.2. Screening

In this step, the extended time of distribution is not set in stone from the complete distinguished reports. The year of publication was limited to 2013 to January 2024 in Science-Direct, whereas the year was limited to 2013 to 2024 in Google Scholar. Consequently, 49 Science Direct documents and 380 Google Scholar documents were chosen. After that, the kind of paper screening is used to keep out documents other than research papers. The result in Science Direct using the “research article” type of paper filtering is 15 documents, whereas, in Google Scholar, the result is 224. The title and abstract were checked during the screening; if they contained one or more keywords or search queries, they were included in the full-text analysis. As a result, 369 documents were left out of this step. In November 2023, the screening step was not completed.

2.3. Eligibility

The first step in determining eligibility was downloading 75 documents from two search engines. The 75 documents were then analyzed to determine how seawater conversion interacts with nanobubbles and the mechanism behind the various gas nanobubbles. Five documents out of 75 were ruled out because they contained review articles, and five were ruled out because they contained double articles. The 65 documents were, therefore, left out of this step.

2.4. Inclusion

This study included twenty-two documents after full-text analysis. These papers discussed how nanobubbles and graphene oxide interact with seawater conversion and the mechanisms behind the various gas nanobubbles and membranes. The distribution reports were reviewed in the reach season between 2013 and 2024.

Figure 1 depicts how the steps of analysis followed the PRISMA diagram.

3. Types of Gas Nanobubbles and Flotation in the Seawater Desalination

In this review, the application of nanobubbles for the flotation process and the effect of gas types in the conversion of seawater for drinking water were highlighted in terms of concern for the water molecule mobility, free radical formation, mass transfer, and degradation of waste chemicals [12]. This section describes the water molecule mobility, free radical formation, mass transfer, generation, and stability bubbles for nanobubbles technology. [13]. However, different gas nanobubbles are used for seawater desalination based on nanobubble flotation and the atomic interaction between bubbles and particles. [14]. In addition, every kind of gas nanobubble has its application not only for seawater desalination but also for other applications. [15].

3.1. Type of Gas Nanobubbles

There are a variety of potential applications for different kinds of nanobubbles. Hydrogen nanobubble gas mixes can further develop burning execution, contrasted, and regular fuel. [16]. Adding water containing nitrogen nanobubbles can improve the hydrolysis of waste-activated sludge and methane production during anaerobic digestion. [17]. In the anaerobic digestion of cellulose, oxygen nanobubbles produce methane. [18], and CO2 bulk nanobubbles can be utilized in food processing [19]. Some parameters, such as bubble size and zeta potential (ZP) capability, made of a few gases in various arrangement conditions, were estimated to concentrate on nanobubble strength. [20]. The bubble size is the critical boundary utilized to order the bubble. [21]. Another significant boundary of nanobubbles is the electric charge on the bubble surface, which can be utilized to examine the dependability of a colloidal framework. [22]. Consequently, the electric capability of the colloidal framework can be communicated concerning zeta potential, and subsequently, zeta potential estimations were utilized to make sense of the air pocket strength. [23]. Other physical aspects of this technology are pressure and differences. [24], high-speed cavitation [25], ultrasonic waves, and ultrafine pores [26].

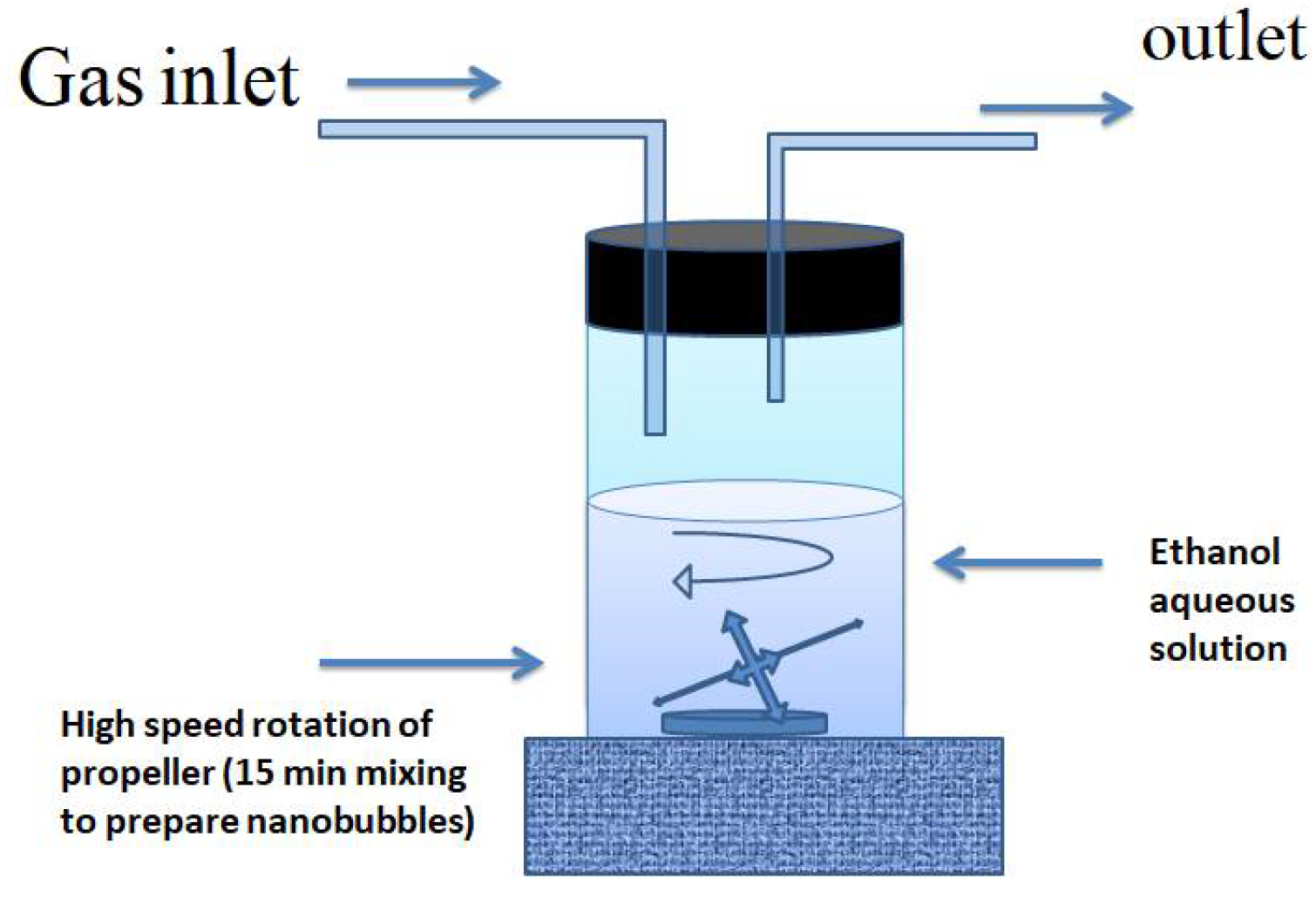

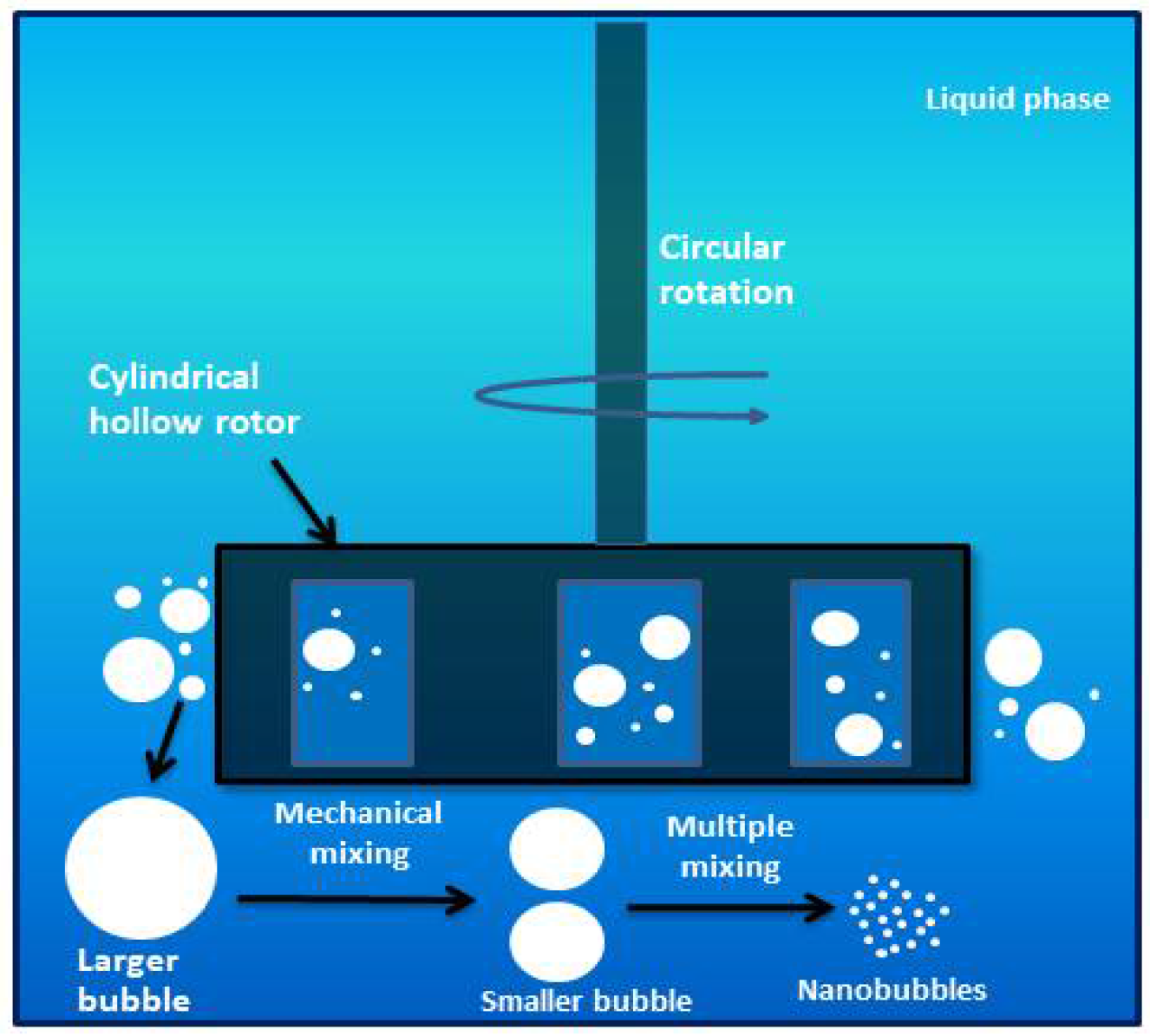

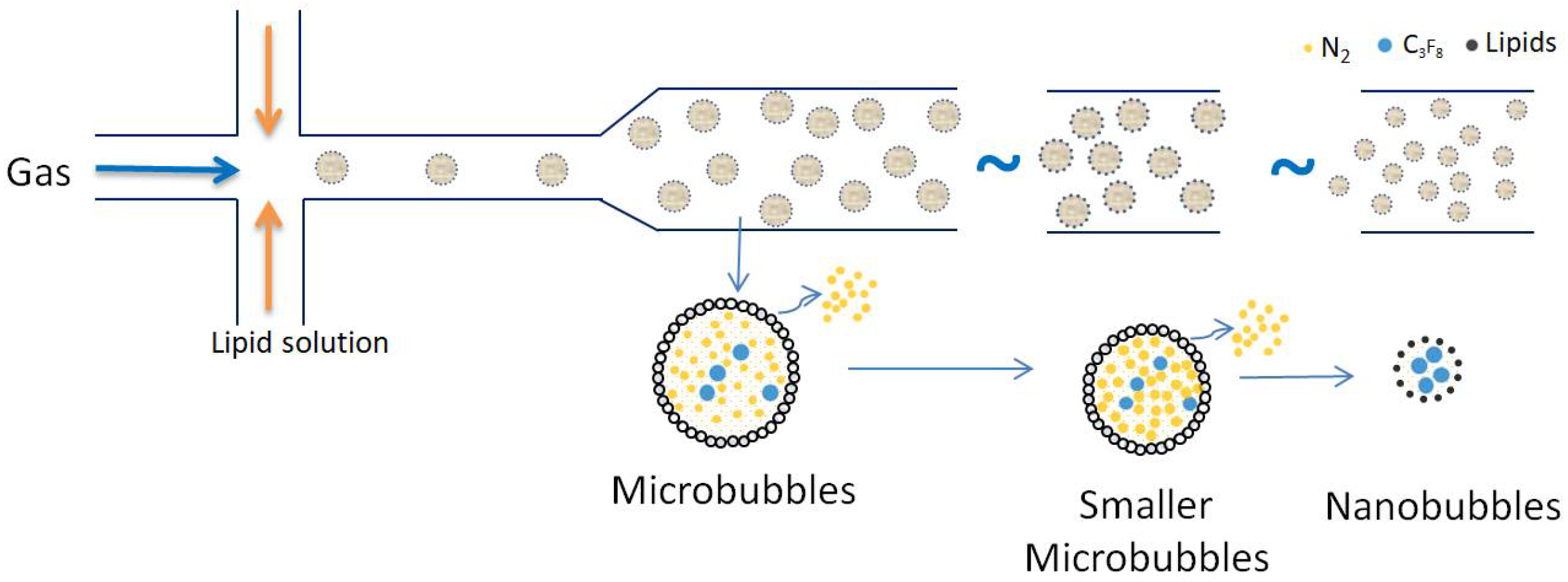

High-speed cavitation, pressure difference with circulation [27], ultrasonic waves, and passing ultrafine pores are just a few of the bulk nanobubble preparation methods [28], Khan (2020) mentioned. In this review, the gear displayed in

Figure 2 was used to create many nanobubbles in fluid in a quick way. The bubble size, zeta potential [9,29], and interfacial characteristics all play a role in nanobubble’s stability and reactivity [30]. The energy the system supplies to generate nanobubbles and solution properties also significantly impact their characteristics. [23]. The solution’s temperature, pressure, ion type, concentration, pH, surfactant presence, organic matter or impurities, and saturated gas concentration are important factors. [31]. The properties of a bubble can also be affected by the kind of in-filled gas and its solubility and reactivity. [32]. In addition, the size of the bubble, the formation of radicals, and the associated chemical reactions are significantly influenced by the generation mechanism and the energy provided to the system (e.g., hydrodynamic method, ultrasound) [33].

NBs can be produced by a few strategies, as displayed in

Figure 2. The production of NBs through simple, inexpensive, stable, and scalable methods is one of the significant issues in the expanded market [34]. Several businesses in the United States, South Korea, Canada, and Japan have produced such bubbles using special techniques, including cavitation chambers, electrolysis [53], shear planes, pressurized dissolution, and swirling fluids in a mixing chamber [35]. A critical number of works zeroed in on bubble age and properties after 2000, initially revealed by Kim et al. Later, in 2007, Kikuchi and colleagues used electrolysis to make NBs [36]. According to Oeffinger and Wheatley’s findings, the addition of some surfactants to a perfluorocarbon gas resulted in the formation of NBs [37]. Najafi et al. (2018) investigated the temperature-dependent NB formation in a closed cuvette [56]. Ohgaki, et.al. [40], said that the concentration of NBs was 1.9 x 10

16 bubbles per dm

3 and stayed the same for up to two weeks. Etchepare et al. (2017) investigated the use of a multiphase pump to generate NBs [42]. The findings demonstrated that the average size and concentration of the bulk NBs remained constant for more than 60 days [24]. Nazari et. al. investigated NBs produced by hydrodynamic cavitation in water using various reagents [42]. Counter-flow hydro and bulk NBs made with oxygen and air in the water dynamic cavitation were studied [43].

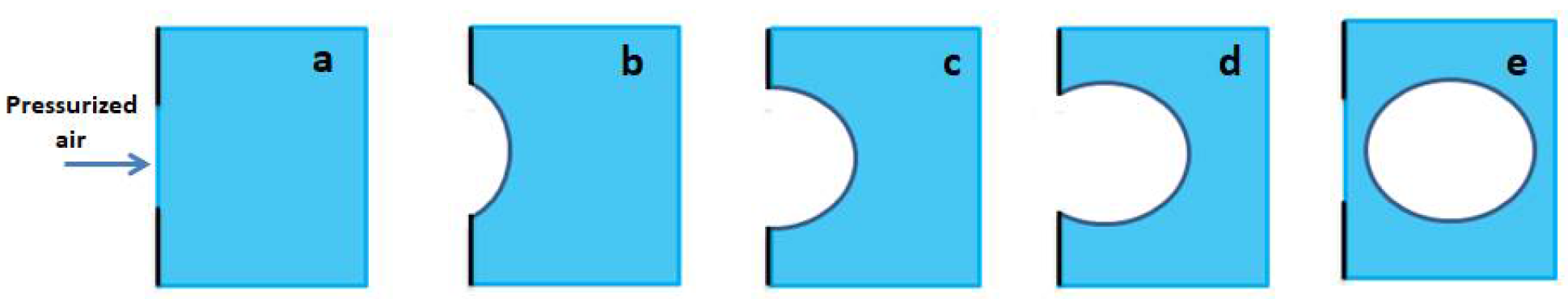

3.2. Generation of Nanobubbles

Cavities are frequently used to generate nanobubbles in solutions. [44]. Pressure drops below a particular critical value, causing cavitation. [45]. Considering the strain decrease component, cavitation systems can be grouped into four distinct sorts. [46]

▪ Hydrodynamics— system geometry-induced variation in the pressure of liquid flux [47].

▪ Acoustic—a sound made when ultrasound is applied to liquids [48].

▪ Particle— passing light photons with a high intensity through liquids [49].

▪ Optical— lasers with short pulses focused on solutions with low absorption coefficients [50].

▪ According to Tsuge (2019), nanobubbles’ hydrodynamic generation typically occurs. [51].

▪ Compress gas flows in liquids to dissolve them and then release the resulting mixtures through nano-sized nozzles to form nanobubbles [52].

▪ Use focusing, fluid oscillation, or mechanical vibration to break up gas into bubbles by injecting low-pressure gases into liquids [19].

In addition, ultra-fine bubbles have been made by electrolysis, applying Nano pores membranes, sonochemistry with ultrasound, and mixing water and solvent. [53]. Numerous factors, including pressure, temperature, the type and concentration of the dissolved gas and electrolyte solution, influence the formation of nanobubbles. [54]. There are currently many commercially available nanobubble generators, most intended for small pilot projects or the laboratory. [34].

Investigation about the nanobubbles generators that can produce nanobubbles in the flotation process for ion separation, especially [55]. The issue of waste chemical degradation and ion separation is investigated at the microscopic scale, the ion scale. The separation process for this flotation process is ion flotation, which will be discussed in the next section. Ion flotation has been proposed since the 1960s and has been a promising method for removing heavy metals.

3.3. Generation and Production of Different Gas Nanobubbles

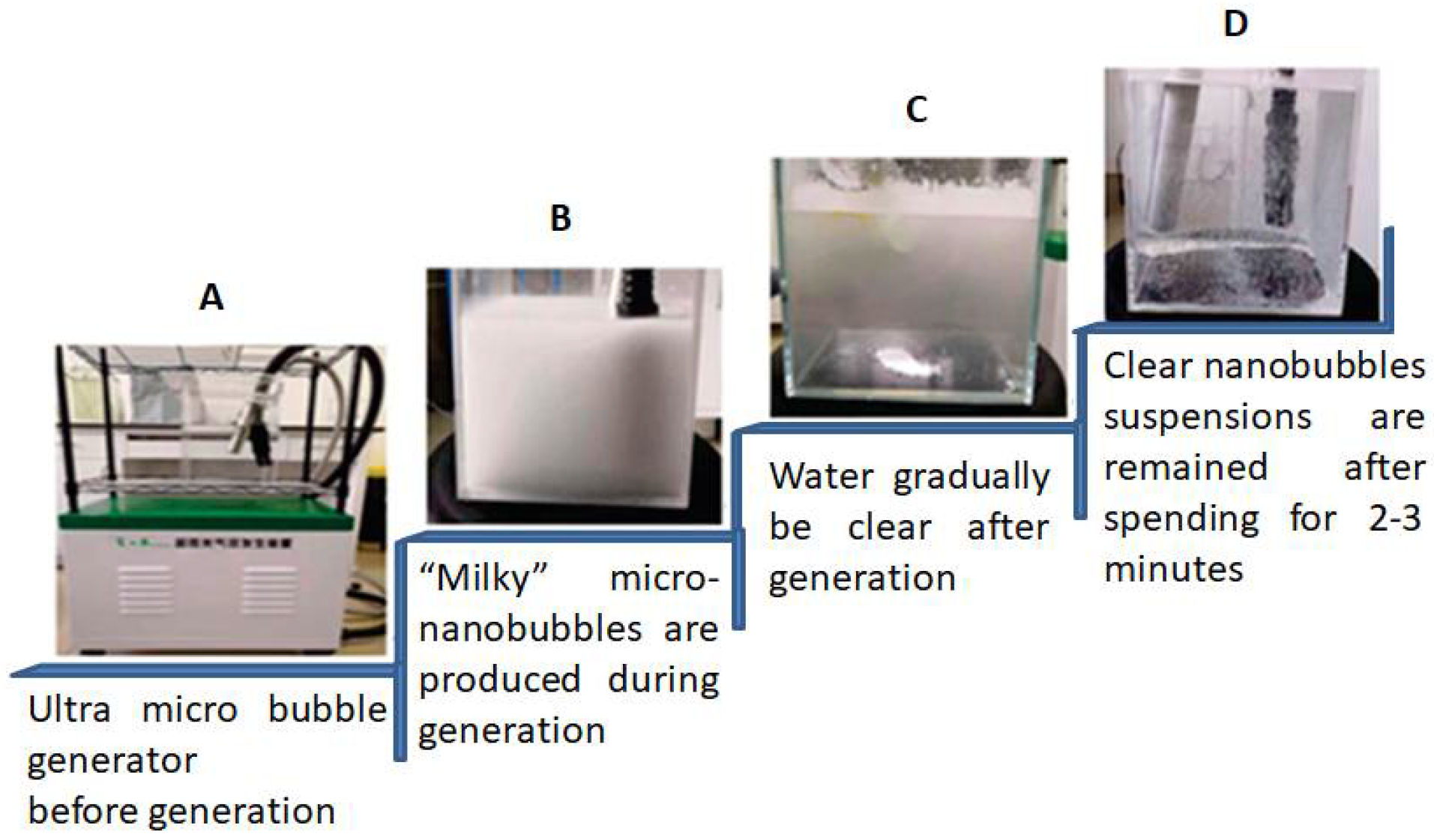

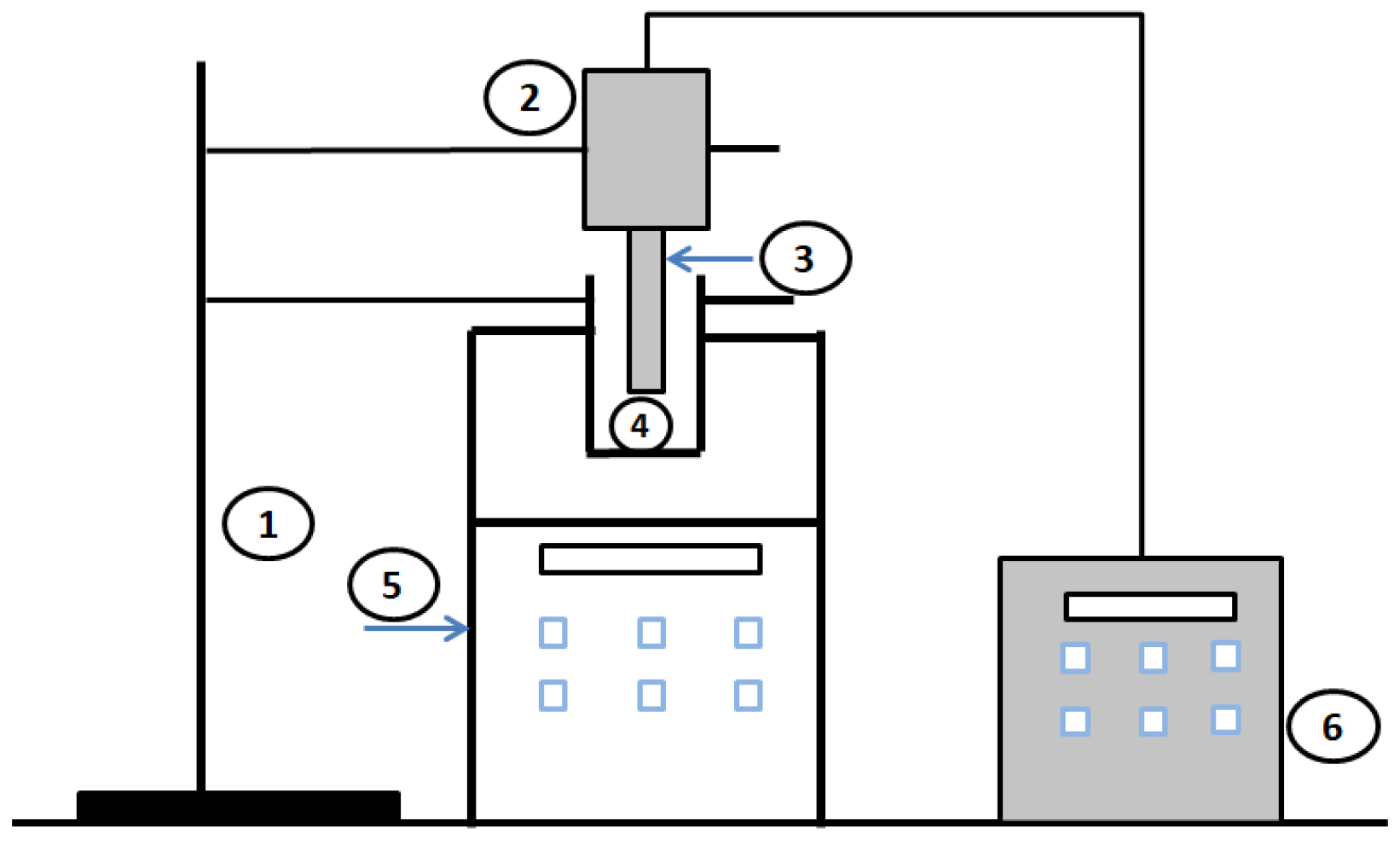

The following section shows the generation of different types of gas nanobubbles with different treatments. To create water nanobubbles, a Xiazhichun Co. Ltd. ultra-micro bubble generator (XZCP-K-1.1) with a range of 100 nm to 10 m was used [56]. In the 10 L glass container with a circulation between the inlet and outlet, as shown in

Figure 3A, inlet and outlet pipes were immersed in deionized water/electrolyte solutions. The machine mixed the gas and liquid, and then high-density, uniform, and “milky” nanobubbles of water were produced (

Figure 3B) through a nozzle using the hydrodynamic cavitation method. When the generator was turned on, damaging pressure gas was pumped into the machine from a gas. As the micro-bubbles rose and fell at the air-water interface, the cloudy and milky nanobubbles water gradually became clear (

Figure 3C). This cycle took 2 to 3 min (

Figure 3D). Using Nano Sight, NS300, Malvern (Worcestershire, UK) outsourcing, the machine produced many density nanobubbles of water with a density of more than 108 bubbles per milliliter after working for 15 minutes. The nanobubble water reached a temperature of 313 K following the preparation above steps and was left to cool to room temperature. The large bubble sizes of 1 to 10 m were then removed from the prepared nanobubble water using centrifugal treatment in the following manner. A centrifuge tube of 50 mL was used to store the nanobubbles water; following that, a six-minute centrifugal treatment at 6000 rpm, or 31.4 m/s peripheral velocity, was carried out to eliminate any potential impurities and giant bubbles. One sealed centrifuge tube containing nanobubbles of water was kept at room temperature (298 K) for continuous measurements. At the same time, the size distribution, zeta potential, Eh (Energy of Harvesting), and pH were all measured after centrifugation to record the first day’s data.

3.4. Nanobubbles Application in the Water Treatment

According to the literature, Nanobubbles, or called Micro-nanobubbles (MNBs) have been helpful in water treatment and aeration procedures. [57], flotation [58], and disinfection [28]. The primary areas of MNB applications in water treatment, according to studies, are the reduction of system structure size, as shown above, the generation of nanobubbles, operating time, processing plant operating costs, and efficiency in the removal of water pollutants, particularly seawater. [59]. This review gives the details of the flotation process in the water treatment. Accordingly, people worldwide are affected by the lack of freshwater due to organic and inorganic contaminants. [60]. Many methods have been developed to remove contaminants from aqueous solutions, such as oxidation or reduction, chemical precipitation, adsorption, ion exchange, reverse osmosis (RO), electrochemical treatment, membrane technology, evaporation, and electroflotation. These methods have many disadvantages, such as high cost, generation of large amounts of sludge, high reagent or energy requirements, time consumption, incomplete removal of target ions, and difficulty treating large volumes of wastewater. [61]. Due to the lack of various methods in water treatment, ion flotation has been evaluated as an excellent alternative treatment process for wastewater treatment due to its low energy requirements, rapid operation, small space requirements, simplicity, etc.

3.4.1. Aeration Process

Aeration is the process of introducing or penetrating oxygen into water. It plays a crucial role in supplying oxygen necessary for biochemical substrate reactions and aquatic life in water treatment [62]. Numerous studies have examined the effects of aeration processes on wastewater, biological water treatment, and groundwater recovery [63]. Enhancing the effectiveness of the factors that influence the speed of mass transfer was one of many studies’ primary goals. Dissolved oxygen (DO) plays a significant role in overcoming this inefficiency in typical aerobic systems [64]. Most of the contact equipment in these systems uses diffusers or mechanical aerators, both of which necessitate significant electrical input and high maintenance costs [65]. In order to enhance mass transfer aeration, research has primarily focused on optimizing conventional bubbles and aerator design [66]. However, there is little industrial-scale research on using high-mass transfer bubbles [34]. Weber and Agblevor (2005) concluded that MB aeration is better suited to bioreactors after describing the characteristics of the transfer rate of gas-liquid mass in stirred-tank reactors [67]. They examined how MB aeration affected the mesophilic filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei’s fermentation, limited by oxygen mass transmission. This study showed that the concentration of broken-up oxygen was higher than the focus at a lower unsettling rate because of the utilization of MB air circulation [68].

In addition, compared to conventional bubbling, the concentration of cellular mass increased rapidly during the rapid growth phase, rising from 0.1 to 0.18 g/LH. Patel et. al., (2021) reported that NBs in aerated water resulted in better seed germination than in regular water. [63]. Similarly, Malik (2020) researched the growth of lettuce (Lactuca sativa) using MB aeration. [69]. They discovered that the dry and fresh bulk of appropriately aerated MB lettuce were 1.7 and 2.1 times higher than those of macro bubble lettuce. The researchers hypothesized that the specific surface area of MNBs and their more remarkable ability to attract positive ions were related to higher germination and growth rates in these studies. [70]. In addition, oxygen MNBs outperform air micro-NBs in terms of mass transfer efficiency by 126 times and dissolved oxygen (DO) by three times. The longer MBs remain in the water and the greater the mass transmission at the bubble interface, the more effective oxygen transmission becomes. Khan (2020) studied the use of NBs for the degradation of aerobic waste in wastewater treatment using MNBs [28]. The findings demonstrated that the volume transfer rate and oxygen utilization rate of the synthetic aerated NB treatment plants were nearly twice as high as those of conventional air bubbles.

3.4.2. Flotation Process

Flotation has also played a significant role in water purification as a separation method (Hopper & McCowen, 1952) [71]. Dust, chemicals (heavy metal especially), organic matter, metal ions, and oils are the most specific substances that must be removed from flotation (Azevedo et al., 2016) [57]. For instance, Dockko and Han (1998) discussed the possibility of improving flotation efficiency by altering the bubbles’ characteristics, i.e., the size of the surface and particle properties. [72]. The efficiency of the separation process is closely linked to the size of the bubbles. NBs and MBs are frequently utilized in flotation to remove pollutants from the water more effectively. Subsequent experimental studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of this method for collecting bubbles and particles. [73]. According to Ahmed & Jameson (1985), the speed of flotation increased 100 times when the bubble size decreased from 655 to 75 m, indicating that the size of the bubbles had a significant impact on the process. [74].

In addition, Zhang (2021) stated that a strong correlation exists between the possibility of tiny particles colliding with small bubbles and the reduction in bubble size in flotation, which increases separation efficiency. [75]. Unlike standing molecule sizes and little air pockets, surface charges play a massive part in buoyancy (Collins & Jameson, 1976) [76]. According to Maeng et al., (2021), positively charged MBs are expected to effectively remove algae from the water at a rate of 90% cell elimination and 92% chlorophyll reduction. [77]. The MBs could achieve an elimination rate of more than 30% for organic substances, such as dissolved and organic carbon and aliphatic or aromatic mixtures. [78]. Sumikura also investigated the possibility that the NBs increased surface hydrophobicity and expanded the area of flotation particles, both of which improved flotation efficiency (Sumikura et al., 2007) [79].

3.4.3. Disinfection Process

Ozone oxidation of pollutants and pathogens is a promising wastewater purification technique (Zhang et al., 2021) [80]. According to studies, ozone gas bubbles successfully treat water entirely, even with a short contact time and low concentration, due to their potent disinfection properties. This method’s application for chemical-resistant spore-forming bacteria, such as Cryptosporidium partum and Bacillus subtilis, has frequently increased due to its effectiveness. Also, MBs make this process more efficient because kinetic disinfection reduces Escherichia coli (the type of bacteria) faster (by 99 percent) with a smaller water tank and less ozone (for applying MBs) than traditional ozone disinfection. [79]. Using 490 Watt/Liter energy, another experiment to stop E. coli multiplication achieved a 75 percent reduction in just three minutes (Mezule et al., 2009) [81]. Simultaneously, the efficacy of MNBs as a non-reagent method for water disinfection was demonstrated by hydrodynamic cavitation results from various experiments. [80]

4. Results & Discussion

4.1. Types of Flotation

Masses of macro-scale experiments have improved and verified the flotation performance of various minerals in the presence of BNBs. Furthermore, flotation can be seen in different applications for different purposes. This section will show the type of flotation from the industrial and scientific perspectives.

Table 2 shows the differences in flotation based on its application; this review article requires advantages, especially for ion flotation. Ion flotation is one potential technique to remove hazardous ions from drinking water at low-level concentrations. It is environmentally friendly and biodegradable. [87]. The flotation techniques used in these processes are froth flotation, dissolved air flotation, precipitation flotation, and ion flotation. [75,80]. The ion flotation derives from the mineral separation industry. This technique can remove organic and inorganic contaminants from wastewater in anionic or cationic forms. Today, ion flotation is used for recovering precious metals, ion separation, and wastewater treatment because of its low-cost ancillary devices, flexibility, low energy consumption, and a negligible amount of sludge (Liu et al., 2012) [90].

4.2. Effect of the NBs to Enhance the Desalination Process

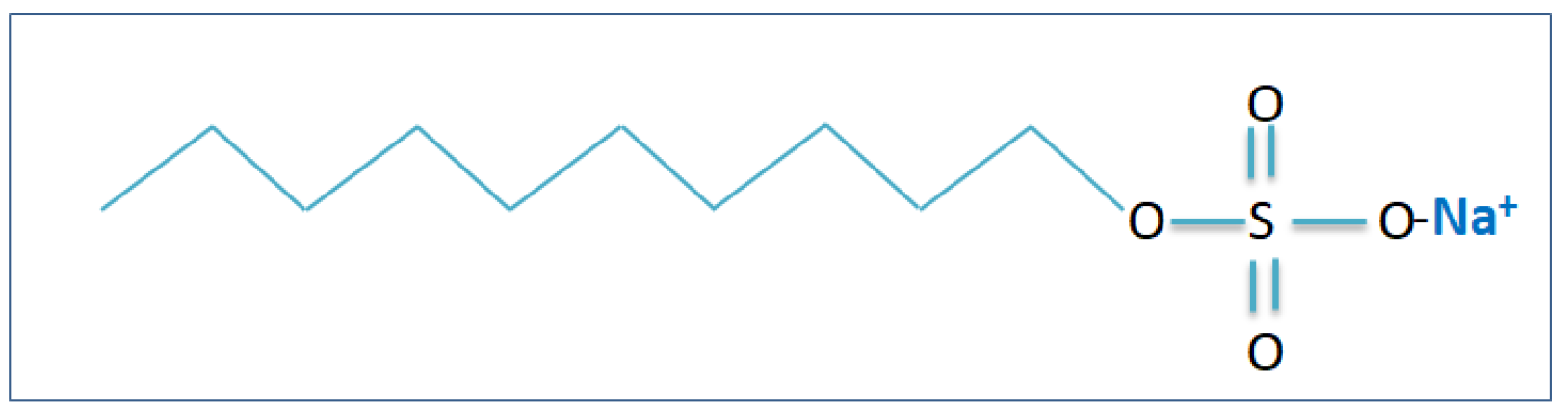

Furthermore, in the removal of pollutants from water, there is no significant way for ion flotation in terms of heavy metal separation [23,68]. This is a technique capable of removing organic and inorganic contaminants either anionic or cationic from wastewater and in the ion flotation for which the simple explanation is different but close to the froth flotation [91]. The important process is that the surfactants adsorb the nanobubbles from the bottom of column flotation which will interact with the heavy metal ion to be collected specifically and as the bubbles rise, surfactant ions can be collected in the froth [92]. One of the most well-known chemical synthetic surfactants that is used widely in industries is sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) [93–95]. This surfactant is also known as sodium lauryl sulfate.

Figure 4 illustrates the molecular structure of this anionic surfactant. The SDS is a surfactant that is effective in removing heavy metals. Kukizaki M. et al., have reported that applying the SDS as the collector in an ion flotation process for removing the Mn

2+, Cu

2+, and Zn

2+ from water [96].

Table 3 shows the results obtained from various studies of the various pollutants and removal using the SDS to remove different kinds of heavy metal ions through ion flotation.

According to

Table 3, even though the axillary ligand metals are used the removal rate percentage is relatively lower than by the surfactant of SDS. Besides it, the Tea Saponin was used to remove the cadmium (Cd (II)), copper (Cu (II)), and lead ions in an aqueous solution [101,102]. The removal efficiency was decreased rapidly with the increasing ionic strength of the sodium chloride (NaCl) with an average concentration of about 0.001 to 0.004 M. Further research and methodological work are needed on how to treat the other valuable ions, such as gold, etc., to reduce the significant costs of current refining processes. The surfactant also showed in

Table 5 that high efficiency for the removal of relatively high concentrations of copper ions could be used as a promising alternative for the treatment of different industrial and mining wastewater.

In addition, nanobubbles have enhanced the desalination process through the interaction of the bubbles and the seawater which have a few types of interactions. The theory of buoyancy explains that when bubbles in water decrease in size, their rising speed decreases as well. Micro-nanobubbles (MNBs) are less likely to collapse compared to regular bubbles because they have a stronger surface, a smaller volume, and less buoyancy. Studies suggest that MNBs with a diameter of less than 1 μm remain stable in water for a long time due to their significantly slower rising speed than Brownian motion [103].

Nanobubbles—those tiny, ephemeral spheres of gas suspended in liquid—have been making waves (also intended) in the field of water desalination. This is their influence on enhancing the desalination process. Some factors of the influence on enhancing the desalination process based on the studies. The first factor is about the nanobubbles and membrane; Researchers have explored the use of nanobubbles (NBs) to improve the performance of thin-film composite (TFC) polyamide membranes in forward osmosis (FO) desalination [104]. These NBs are generated by adding sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO₃) to the aqueous phase during membrane preparation [105]. Secondly, by adjusting the Micro-Nano structure of the polyamide (PA) rejection layer, NBs alter the membrane’s roughness. With enhanced NBs, the PA layer exhibits more blade-like and band-like features. These features effectively reduce the reverse solute flux of the PA layer and improve salt rejection in the FO membrane [106]. Thirdly, the influence of the surface area and its interaction. One of the primary advantages of utilizing 30 nm nanobubbles is the substantially increased surface area they provide. This increased surface area allows for more effective interactions with contaminants, facilitating better separation during desalination. In essence, NBs enhance the membrane’s ability to reject salts and impurities. The fourth aspect is about reducing chemical dependency; the efficiency of NBs in removing impurities minimizes the reliance on chemical additives commonly used in traditional desalination. This reduction in chemical dependency contributes to cost savings and lessens the environmental footprint of the water treatment process. In summary, these minuscule bubbles play a pivotal role in advancing desalination technology.

4.3. Interactions of NBs and Seawater: Physical, Chemical, Electronic, and Mechanical Interactions

The interactions between nanoparticles (NBs) and seawater can be diverse and multifaceted, involving physical, chemical, electronic, and mechanical aspects. Also, this interaction plays an important role in conducting a deeper investigation into water treatment. This is the following of these interactions: (a) physical interactions; (b) chemical interactions; (c) electronic interactions and (d) mechanical interactions.

4.3.1. Physical Interactions

Nanobubbles (NBs) have tiny particles in size of particle distribution (nanoscale). When nanoparticles (which means nanobubbles) interact with seawater, they may undergo dispersion, where they become evenly distributed throughout the water due to Brownian motion and other forces [107]. However, they can also agglomerate, forming larger clusters due to attractive forces such as van der Waals interactions or electrostatic forces. Another aspect of nanoparticles is they may adsorb onto various surfaces in seawater, such as sediments, organic matter, or biological surfaces [108]. This adsorption can affect the behavior and fate of the nanoparticles in the marine environment [109]. NBs have been well-known due to their advantages, which include the small size distribution (nanoscale) [110], large specific surface area which is evidence of the surface tension [110], long residence time in the water during the interaction [73], high mass transfer efficiency [73], high interface zeta potential which concludes the distribution of particle charge on the surface of the bubble [23], and the ability to generate hydroxyl radicals (which produces the free radical) [111]. These characteristics are significantly distinct from those of the traditional large bubbles.

4.3.2. Chemical Interactions

The surface of nanoparticles can undergo chemical reactions with any substances in seawater, leading to changes in their properties and behavior. For example, nanoparticles may undergo oxidation, reduction, or dissolution processes depending on the composition of the nanoparticles and the chemical environment [112]. The presence of hydrated ion functional groups degrades the stability of GO based on water treatment in water. The oxidized regions act as spacers to separate adjacent GO sheets and allow water molecules to intercalate between the GO sheets. Instability of GO structures in water is the main challenge ahead of their application in aqueous media as separation membranes, as GO structures disintegrate over time [113]. For application to water treatment, GO membranes should be stabilized by reduction or chemical crosslinking [114]. Moreover, nanoparticles may exchange ions with seawater constituents, leading to changes in their surface charge and reactivity. This ion exchange can influence the stability and interactions of the nanoparticles in seawater [55,115].

4.3.3. Electronic Interactions

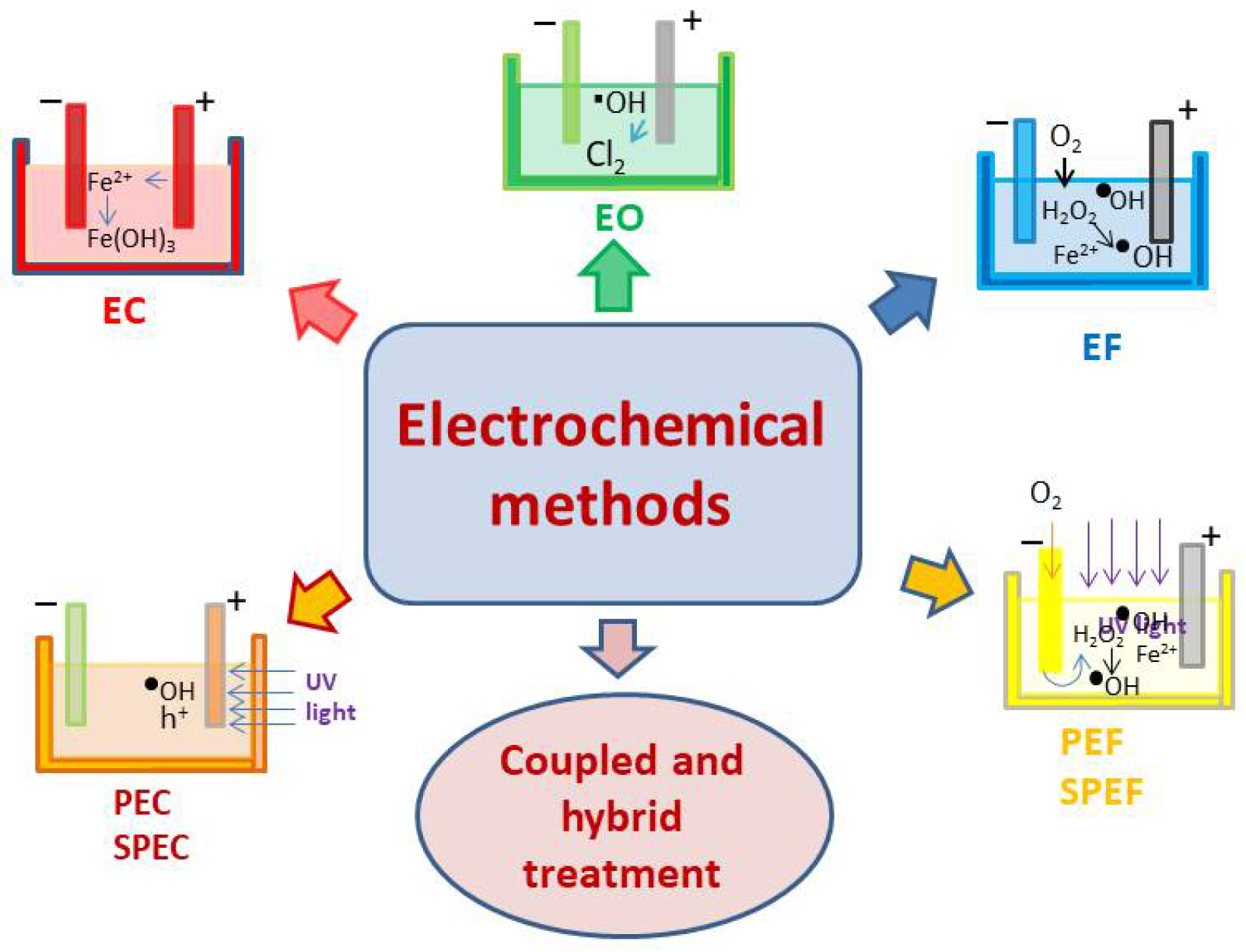

The electronic structure of nanoparticles can influence their interactions with seawater constituents. Electrochemical water treatment technology utilizes applied potential or current to drive processes such as electron transfer [116] or multiple proton-coupled electron transfer [117], leading to chemical processes such as the oxidation, reduction, adsorption, and migration of pollutants [66]. Otherwise, it applied in situ generated chemical processes to remove the contaminants [118]. Depending on the process principle, it could be divided into electrochemical oxidation, electroreduction, and so on [119] as seen in

Figure 5. For example, nanoparticles with certain electronic properties may exhibit enhanced reactivity toward specific chemical species in seawater [34]. In addition, the surface potential of nanoparticles, which depends on factors such as surface charge and composition, can affect their interactions with charged species in seawater through electrostatic interactions.

4.3.4. Mechanical Interactions

Nanoparticles in seawater can experience mechanical forces such as sedimentation due to gravity or transport by water currents. The size, shape, and density of nanoparticles influence their sedimentation rates and transport behavior [120]. The perception of hydrodynamics forces around particles, drops, or bubbles moving in Newtonian liquids is modestly mature. It is possible to get the predictions of the attractive–repulsive interaction among particles for moving ensembles of dispersed particulate objects [121]. Gravity-driven flows: rise or sedimentation of single spheroidal objects, pairs, and dispersions are focused on the mechanical interactions [122]. It could be identified the effects of two main rheological attributes—viscoelasticity and shear-dependent viscosity—on the interaction and potential aggregation of particles, drops, and bubbles [34].

The presence of salt ions can greatly impact the process of mineral flotation when using process water that has a high salt content [123]. This can be attributed to the fact that high salt concentrations can alter the pH and ionic strength of the pulp phase, as well as the properties of the bubbles involved. Moreover, dissolved salt ions can impact the wetting properties of salt crystal surfaces, and therefore, directly influence the interaction between the salt surfaces and the collectors in the flotation process e.g., ion flotation [124]. Ion flotation is a method of separation that involves the addition of surfactants or collectors with opposite charges to those of the target ions, which results in the formation of a surfactant complex. The ions can then be collected by passing gas bubbles through the solution [60].

4.4. Nanobubbles Technology in Desalination

Bubbles are a fascinating hydrodynamic phenomenon that has significant impacts on both natural and social activities. Unfortunately, when bubbles collapse, they can create negative effects such as high-speed jets and shock waves [125–127]. However, engineers have found ways to utilize the dynamic characteristics of bubbles in various applications, including ultrasonic cleaning [125], shock lithotripsy, and air-gun detection. Investigating the complex interaction between bubbles and incomplete boundaries is a crucial area of research [128]. In underwater explosions, an oscillating bubble can cause high-speed in rushing water through an opening, which can impact the inner structures of a ship and cause secondary damage [129]. Researchers are working hard to uncover the mechanisms behind this nonlinear multiphase interaction problem.

Nowadays, nanobubbles are used widely in several industries, including manufacturing [130], agriculture [131], and medicine [132]. Nanobubbles are useful in medicine for drug delivery [133] and medical imaging [134] because of their superior contrast and material transport properties. By increasing water permeability, nanobubbles are well-known to encourage plant growth in agriculture [135]. In industry, nanobubbles boost, not only a solution’s oxidation capacity but also conduct chemical interactions with contaminants; thus, they are frequently employed in wastewater treatment [136] and surface cleaning [137] industries. In the seawater desalination process, nanobubbles are able to enhance the concentration of dissolved oxygen in water while they can do an ion separation due to the interactions such as physical, chemical, electronic, and mechanical interactions between seawater and nanobubbles [138]. Nanobubbles will be employed more frequently as preparation technology advances and study on them advances. As such, the development and optimization of processes for the stable and effective production of nanobubbles will be crucial.

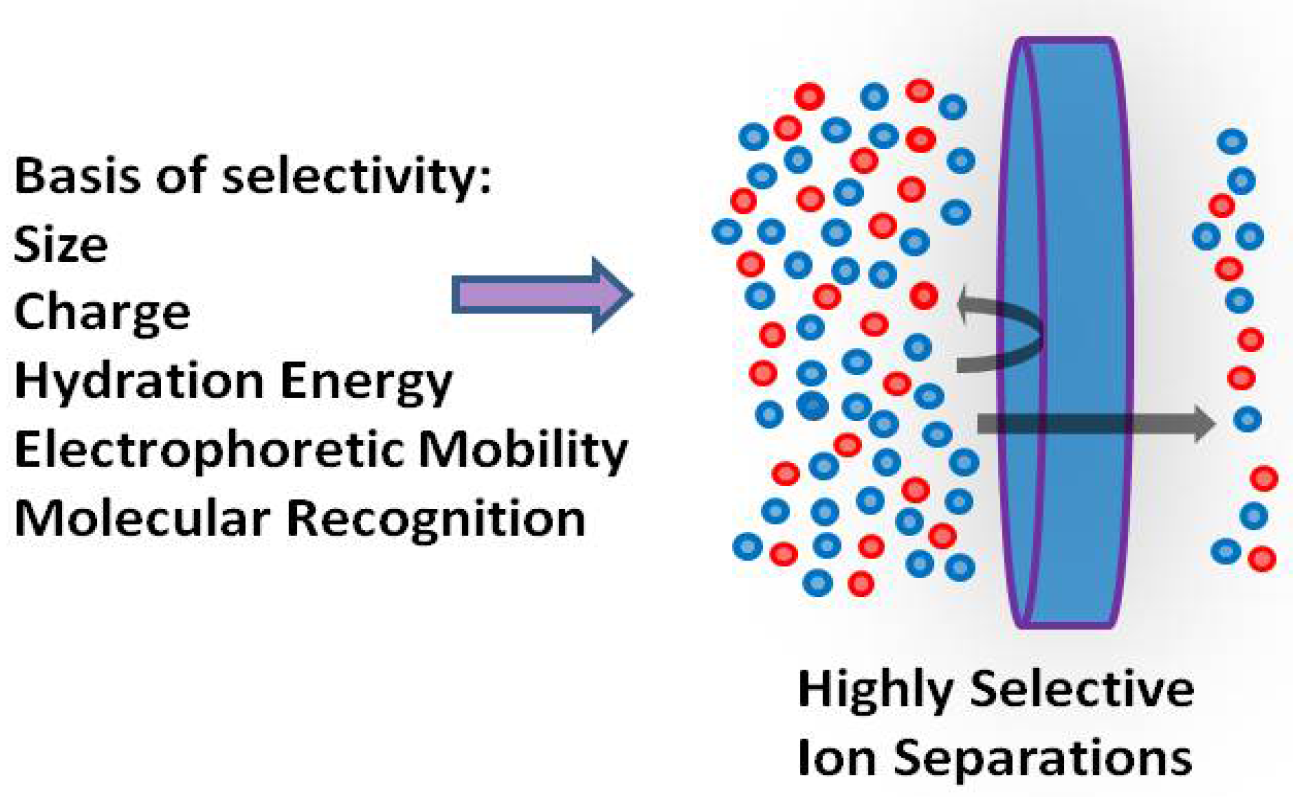

4.4.1. Ion separation in Seawater Desalination

The separation of ions is crucial for various applications such as resource recovery, water treatment, and energy production and storage [115]. While techniques like chemical precipitation, selective adsorption, and solvent extraction have proven effective, membranes offer a continuous separation of ions with minimal waste and lower energy costs [139]. Nanofiltration and electrodialysis membranes already can separate monovalent and multivalent ions, enabling water softening and edible salt purification [140]. These membranes are also promising separators for vanadium redox flow batteries. It is possible to transport divalent counter-ions against their concentration gradients in salt mixtures by selectively partitioning them into ion-exchange membranes. However, separating ions with the same charge presents a greater challenge. Recent studies have shown highly selective ion “sieving” at small scales [141]. Separations using electrical potentials and differences in ion electrophoretic mobilities are promising but relatively unexplored [139,142]. While carrier-mediated transport offers high selectivity in liquid membranes, these systems are unstable, and selective transport via hopping between anchored carriers remains elusive.

Desalination of brackish water and seawater has become an increasingly popular solution to global water scarcity [143]

. According to

Table 4, reverse osmosis (RO) is the most widely utilized desalination technology due to its energy efficiency and space-saving design. In recent years, numerous efforts have been made to enhance membrane performance, specifically in terms of higher permeability, to further improve RO’s energy efficiency.

4.4.2. Nanobulles Generations Methods

The formation of BNBs in a liquid can be achieved through various means, such as adjusting gas pressure, ultrasonic intensity, or stirring intensity. Preparing NBs typically involves mechanical stirring, gas dissolution release, pressure variation, and cavitation. Additionally, microfluidic and nanoporous membrane methods are also utilized for BNB preparation. This section offers an overview of the methods used for BNB preparation and concludes with a comprehensive summary of the pros and cons of each method, presented in the form of a table.

- 1)

>1) Mechanical Stirring Method

The preparation of BNBs involves mechanical agitation, which entails the iterative rotational stirring of a surfactant-containing liquid phase through a mechanized mechanism [151]. This process promotes interactions between the gas and liquid phases, resulting in the formation of bubbles [28]. BNBs can be created with a pump and circular column under varying pressures and air-liquid interfacial tensions, and they can maintain their stability for up to 60 days [23]. Using nanobubbles generated via mechanical stirring can enhance heat transfer oil’s thermal conductivity and viscosity [152]. Various hollow-shaped rotating mechanisms can be utilized to generate BNBs in pure water, and increasing the rotational speed, extending the operating time, and elevating the temperature can increase the concentration of bubbles generated.

- 2)

>2) Nanoscale Pore Membrane Method

BNBs can be created using the nanoporous membrane method by forcing gas into the Nanoscale pores of the membrane. The diameters of the nanobubbles increase as they expand, and the drag force causes them to detach from the pore, creating BNBs larger than the pore diameter. The SPG membrane is a uniform and adjustable inorganic membrane that can prepare monodisperse nanobubbles. BNBs can be generated by adjusting the pore size of the membrane. BNBs can be prepared using tube ceramic membranes by injecting air at different pressures into the water through the tube. Finally, a membrane-based physical sieving method can adjust the size range of generated BNBs by controlling the gas filtration rate and membrane quality.

- 3)

>3) Microfluidic Method

The preparation of BNBs through microfluidics involves regulating mixed gas and liquid flow using microfluidic chips. [122]. To create microbubbles, a gaseous mixture is introduced through a gas inlet and passes through the liquid phase, which exerts viscous forces on the gas. Some of the gas within these microbubbles’ dissolves into the aqueous phase and eventually shrinks, giving rise to BNBs. Xu et al. [153] Were the first researchers to use a microfluidics-based approach to prepare BNBs, using the experimental setup shown in

Figure 9. They employed a mixed gas of water-soluble nitrogen and water-insoluble perfluorocarbon (PFC) as the gaseous phase for the microfluidic bubble generator. Initially, monodisperse microbubbles are generated, which gradually shrink as the water-soluble nitrogen dissolves, ultimately resulting in BNBs of a specific size. The degree of bubble contraction can be controlled by adjusting the ratio of water-soluble nitrogen and water-insoluble PFC. This method is advantageous because it provides precise control over the size and uniformity of the resulting BNBs.

- 4)

>4) Acoustic Cavitation Method

The acoustic cavitation method is utilized for BNB preparation to create a localized negative pressure in the liquid medium. This can be achieved by either high-speed propeller rotation or high-intensity sound waves, forming micro- and nano-scale bubbles near small gas nuclei. Nirmalkar et al. (2019) conducted experiments on BNB preparation using this method, with the experimental setup illustrated in

Figure 10. Their research found that BNBs exist in pure water but not in organic solvents, disappearing when a particular organic solvent-to-water ratio is reached. This is because of the electrostatic charge on the surface of the BNBs, stabilized by hydroxyl ion adsorption generated by water’s auto-ionization. Pure organic solvents do not undergo auto-ionization, resulting in this outcome.

- 5)

>5) Hydrodynamics Cavitation Method

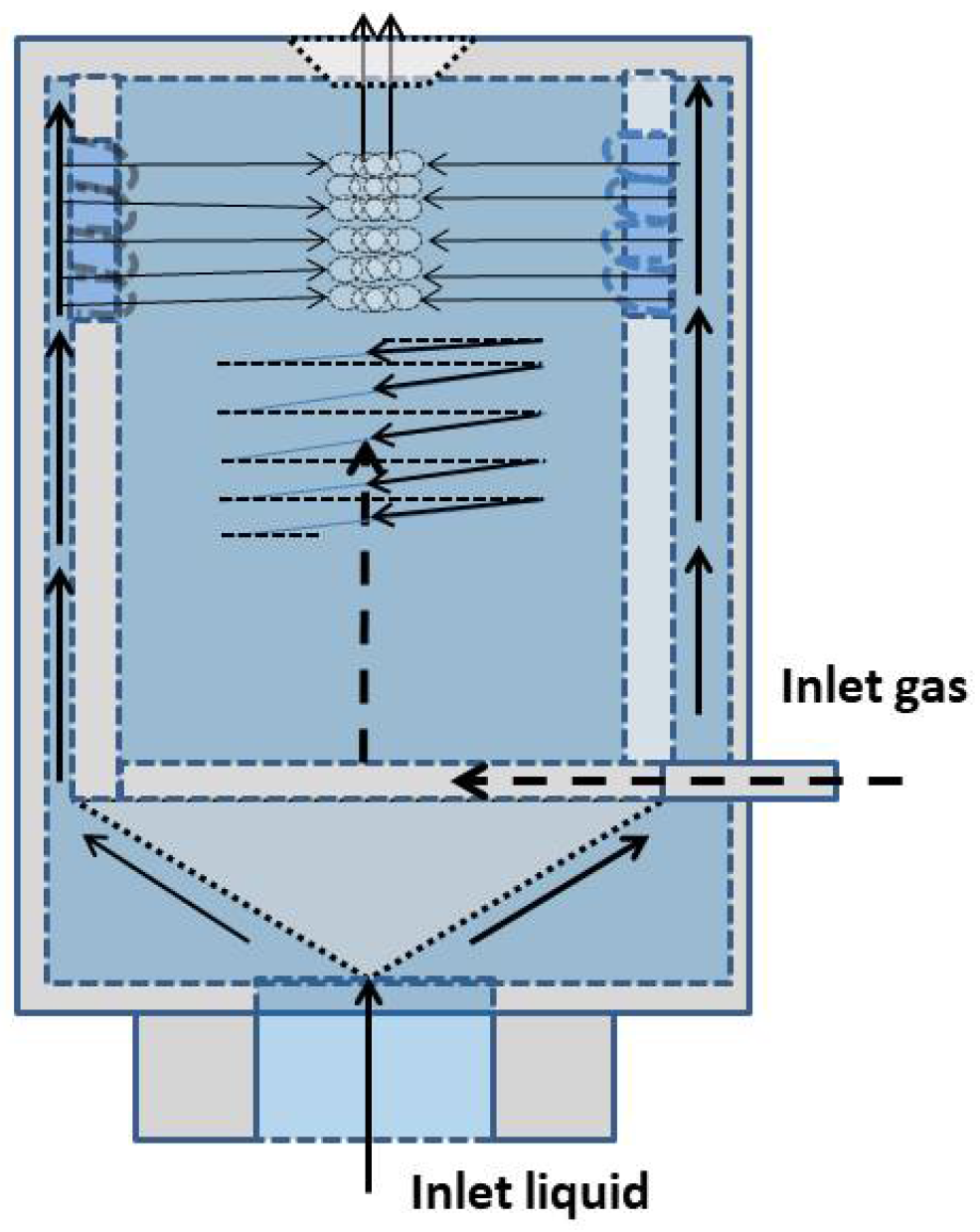

The hydrodynamic cavitation technique has several advantages, such as being highly energy efficient, low cost, and scalable. Its primary aim is to create cavitation in a medium by altering its flow velocity, causing pressure fluctuations similar to those produced by acoustic cavitation techniques [37]. Therefore, hydrodynamic cavitation can replace acoustic cavitation for the generation of nanobubbles. Chang et al. (2022) experimented with generating nanobubbles via hydrodynamic cavitation. They used a two-chambered swirling jet nozzle to produce nanobubbles in a saturated or supersaturated solution through a circulation system, as shown in

Figure 11 [151]. The results indicated that the device successfully generated nanobubbles with diameters of less than 200 nm, and these nanobubbles carried a negative charge when present in water. Zheng et al. (2022) refined the cavitation reactor in their study, using numerical simulation to examine the impact of various geometric parameters on the flow field structure [154]. They identified the optimal design and fabricated a laboratory-scale vortex-type micro-nanobubbles generator. Flow experiments were conducted, resulting in the production of bubbles with diameters as small as 301 nm. This undertaking provided valuable insights into exploring the methodologies of micro-nano bubble generation and the quest for their optimal structural configuration.

4.5. Effect of Gas Nanobubbles on the Seawater Desalination

Water’s bulk nanobubbles are compressed by a gas-liquid interface, which causes them to continuously shrink as they rise to the surface of the water and exhibit a self-pressurization effect. According to Tuziuti et al. (2018), the pressure gradient is inversely proportional to the rate of gas diffusion from the high-pressure region to the low-pressure region, and as the bubble shrinks, the rate of mass transfer from the inside to the surrounding liquid increases [112]. Additionally, because the surface area of a bubble is inversely proportional to its radius (Shen et al. (2022), bulk nanobubbles exhibit a large specific surface area [110]. Due to the self-pressurization effect of the bulk nanobubbles, long residence times, and large specific surface areas, more gas can dissolve into water through the bubble interface, and the gas transfer efficiency to the liquid phase is effectively improved. [19]. Bubbles eventually burst and vanish until their internal pressure reaches a specific limit. To consider various applications, the existence period, average size, zeta potential, and suspension pH and Eh as a function of time of five distinct kinds of nanobubbles of O3, N2, O2, and 8% H2 in Ar, CO2, and air were compared in this review. The effects of salt on the properties of nanobubbles over time were observed and discussed. The extended DLVO theory was used to interpret and discuss our experimental findings regarding the stability of nanobubbles. [16].

According to

Table 5 in the flotation result, the effect of different gases on heavy metal ion removal efficiency in the ion flotation process was also examined [159,160]. Pure nitrogen and dry air were introduced separately to the bubble column to produce bubbles with an average of about 2 mm diameter. The results presented in

Table 4 show that air gas was slightly better for ion flotation than nitrogen, removing 99.9% of the arsenic compared with 99.4% for nitrogen. Mercury was found to have the highest removal rate in the presence of nitrogen gas, at 99.9%; with air, 99.6% was removed. The data indicates the results of removing arsenic, lead, and mercury from water using S-octanoyl- cys as the collector and N

2 and air as the inlet gases to produce bubbles. It is necessary to produce the nanobubble for this flotation results [28]. Because it can impact the other contaminants in water treatment to remove heavy metals through the rising bubble from the bottom of the flotation column.

4.6. Effect of Surfactant on the Ion Flotation for Seawater Desalination

Flotation technology is an effective method for treating industrial wastewater, which includes ion flotation, precipitation flotation, and adsorption flotation, as stated by Santander et al. (2011) [161]. Precipitation and adsorption flotation can generate significant amounts of toxic sludge, which is hard to treat. Ion flotation is a technique that can help extract heavy metal ions with low concentration (0.01 ppm) from wastewater solutions. It has multiple benefits, such as low energy consumption, large processing capacity, low cost, easy operation, and low sludge volume, as indicated by Deliyanni et al. (2017) [162]. The ion flotation process combines metal ions and surfactants in an aqueous solution, which creates flocculated precipitates. These precipitates are then removed and recovered by a foam flotation process, where the surfactant acts as both an adsorbent and foaming agent, as stated by Saleem et al. (2020) [163]. Traditional synthetic collectors used in ion flotation have some limitations, such as low chelating ability with metal ions, nondegradable residual surfactants, and toxicity to the environment, as pointed out by Doyle (2003) [164], and Santander et al. (2011).

To solve these problems, the researchers propose using biosurfactants with high chelating capacity in the flotation of heavy metal ions. Biosurfactants are like chemically synthesized surfactants, having hydrophobic and hydrophilic ends. The hydrophilic group is generally polar and comprises peptides, amino acids, monosaccharides, or polysaccharides. At the same time, the hydrophobic end is typically made up of unsaturated or saturated hydrocarbon chains or fatty acids, as described by Drakontis and Amin (2020) [165] and Shekhar et al. (2015) [166]. Compared to traditional synthetic collectors, biosurfactants have lower toxicity, higher selectivity, and are biodegradable, as Hernández-Expósito et al. (2006) [167], Mekwichai et al. (2020), and Mulligan et al. (2004) have pointed out [168]. Additionally, biosurfactants can be made from inexpensive organic waste and remain active even at extreme pH and salinity levels, as demonstrated by Menezes et al. (2011) [169]. Furthermore, macromolecular biosurfactants have a strong chelating ability to heavy metal ions, forming stable complexes, and are widely used in the remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soil, as noted by Zang et al. (2017) [170].

5. Author Outlook

The existence of bulk nanobubbles in water was initially controversial, but recent experimental research has proven their presence due to the exponential increase in research efforts in recent years. Nanobubbles have unique features such as high stability, long lifetimes, large surface-volume ratio, high mass transfer efficiency, and the ability to generate free radicals, which can improve conventional technologies in the water treatment field. To further exploit their usage and gain a better in-depth understanding of the parameters that have profound impacts, it is crucial to consider the broad applications of nanobubbles for future perspectives. With their small size and existence of a surface charge, nanobubbles have significant potential as a new environmentally friendly method to remove organic compounds, as shown in Figure 12. They also effectively improve the air flotation process to separate suspensions due to their large specific surface area and durability, which enhances the oxygen mass transfer efficiency; furthermore, the ability to generate free radicals with strong oxidation capabilities is essential in decomposing organic substances. As a result, this technology can prove immensely valuable in purifying wastewater that contains organic pollutants. Nevertheless, additional investigation is necessary to overcome the obstacles bulk nanobubbles pose. Confronting these intricate challenges is pivotal to establishing a solid theoretical foundation for the large-scale implementation of bulk nanobubbles in industrial settings. In industrial issues, it might be separated the heavy metal ions in the contaminant water.

Heavy-metal ions are contaminants that the flotation process must recover.

Table 6 shows that

several flotation techniques use froth flotation, dissolved air, precipitation flotation, and ion flotation. [38]. Besides, salt ion is an important thing that should be considered in water treatment, especially for seawater treatment. For this kind of water treatment, ion flotation technology is used. The ion flotation derives from the mineral separation industry. This technique can remove organic and inorganic contaminants from wastewater, either in anionic or cationic forms [171]. Currently, ion flotation is in use for the recovery of precious metals, ion separation, and wastewater treatment because of its low-cost ancillary devices, flexibility, low energy consumption, and a negligible amount of sludge [128]. Ion flotation has been used for the recovery of precious metals because it plays in the ionic ode and has physical and chemical interactions to separate the salt and metals ionic which are used the surfactants, as well as its characteristics and factors, are mentioned in the section the effect of surfactants on the ion flotation.

Salt is an ion dissolved in water, and for some kinds of seawater, it is bonded to heavy metals. The ion separation with membranes integrated into nanobubbles needs to be investigated to produce pure and fresh water from seawater.

6. Conclusions

The recent study of seawater conversion with nanobubbles flotation has been reviewed. Types of gas nanobubbles with characteristics include free mobility water molecules, mass transfer, charged electricity at the interface (zeta potential), and chemical wastewater degradation. The interaction between seawater and gas nanobubbles is degraded due to the change of the nanobubble’s stability because of ion exchange and attractive force that acted in the interface water-gas. It also has the mass transfer of the flotation tank.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.M.J., F.F. and G.J.A.; methodology, P.A.S. and I.M.J.; review investigation, G.J.A.; data curation, P.A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.J.A.; writing—review and editing, I.M.J., C.P. and F.F., supervision, I.M.J.; funding acquisition, I.M.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges the scholarship given to John Alezander Gobai from Beasiswa Program Doktor Padjadjaran (BPDP), contract number 1766/UN6.3.1/PT.00/2024.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- S. Homaeigohar and M. Elbahri, “Graphene membranes for water desalination,” NPG Asia Mater., vol. 9, no. 8, pp. 1–16, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Nicolai, B. G. Sumpter, and V. Meunier, “Tunable water desalination across graphene oxide framework membranes,” Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys., vol. 16, no. 18, pp. 8646–8654, 2014.

- S. Homaeigohar and M. Elbahri, “Nanocomposite electrospun nanofiber membranes for environmental remediation,” Materials (Basel)., vol. 7, no. 2, pp. 1017–1045, 2014.

- M. Elimelech and W. A. Phillip, “The future of seawater desalination: Energy, technology, and the environment,” Science (80-.)., vol. 333, no. 6043, pp. 712–717, 2011. [CrossRef]

- S. M. Park et al., “Influence of hydraulic pressure on performance deterioration of direct contact membrane distillation (DCMD) process,” Membranes (Basel)., vol. 9, no. 3, 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. Rameshkumar, G. Senthilkumar, and R. Subalakshmi, “Purification of tap water to drinking water: Nanobubbles technology,” Desalin. Water Treat., vol. 233, no. October, pp. 11–18, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Buonomenna and J. Bae, “Membrane processes and renewable energies,” Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, vol. 43. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Halali, Electrically Conductive Membranes for Water and Wastewater Treatment: Their Surface Properties, Antifouling Mechanisms, and Applications. macsphere.mcmaster.ca, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://macsphere.mcmaster.ca/handle/11375/26707.

- S. A. Hewage et al., “Recent advances in fundamentals and applications of nanobubble enhanced froth flotation: A review,” Miner. Eng., vol. 57, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. P. Favvas, G. Z. Kyzas, E. K. Efthimiadou, and A. C. Mitropoulos, “Bulk nanobubbles, generation methods and potential applications,” Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 54, p. 101455, 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Sarai Atab, A. J. Smallbone, and A. P. Roskilly, “A hybrid reverse osmosis/adsorption desalination plant for irrigation and drinking water,” Desalination, vol. 444, no. July, pp. 44–52, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. C. E. Leung et al., “Emerging technologies for PFOS/PFOA degradation and removal: A review,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 827, p. 153669, 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Xiao and G. Xu, “Mass transfer of nanobubble aeration and its effect on biofilm growth: Microbial activity and structural properties,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 703, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. F. Bunkin et al., “Effect of Gas Type and Its Pressure on Nanobubble Generation,” Front. Chem., vol. 9, no. March, pp. 1–13, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Patel et al., “Advances in micro- and nano bubbles technology for application in biochemical processes,” Environ. Technol. Innov., vol. 23, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Han et al., “Stability and Free Radical Production for CO2 and H2 in Air Nanobubbles in Ethanol Aqueous Solution,” Nanomaterials, vol. 12, no. 2, 2022. [CrossRef]

- X. Yang et al., “Enhanced hydrolysis of waste activated sludge for methane production via anaerobic digestion under N2-nanobubble water addition,” Sci. Total Environ., vol. 693, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Wang, Z. Pan, F. Jiao, and W. Qin, “Understanding bubble growth process under decompression and its effects on the flotation phenomena,” Miner. Eng., vol. 145, no. October 2019, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. K. T. Phan, T. Truong, Y. Wang, and B. Bhandari, “Formation and Stability of Carbon Dioxide Nanobubbles for Potential Applications in Food Processing,” Food Eng. Rev., vol. 13, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. A. Mørch, “Cavitation inception from bubble nuclei,” Interface Focus, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 1–13, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Azhin, K. Popli, A. Afacan, Q. Liu, and V. Prasad, “A dynamic framework for a three phase hybrid flotation column,” Miner. Eng., vol. 170, no. June, p. 107028, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang et al., “Nanomechanical insights into hydrophobic interactions of mineral surfaces in interfacial adsorption, aggregation and flotation processes,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 455, no. October 2022, p. 140642, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. N. Meegoda, S. Aluthgun Hewage, and J. H. Batagoda, “Stability of nanobubbles,” Environ. Eng. Sci., vol. 35, no. 11, pp. 1216–1227, 2018. [CrossRef]

- R. Etchepare, H. Oliveira, M. Nicknig, A. Azevedo, and J. Rubio, “Nanobubbles: Generation using a multiphase pump, properties and features in flotation,” Miner. Eng., vol. 112, no. June, pp. 19–26, 2017. [CrossRef]

- C. Wu, K. Nesset, J. Masliyah, and Z. Xu, “Generation and characterization of submicron size bubbles,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 179–182, pp. 123–132, 2012. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu and G. Cao, “Effectiveness of the Young-Laplace equation at nanoscale,” Sci. Rep., vol. 6, no. April, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Farzanegan, N. Khorasanizadeh, G. A. Sheikhzadeh, and H. Khorasanizadeh, “Laboratory and CFD investigations of the two-phase flow behavior in flotation columns equipped with vertical baffle,” Int. J. Miner. Process., vol. 166, pp. 79–88, 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. Khan, W. Zhu, F. Huang, W. Gao, and N. A. Khan, “Micro-nanobubble technology and water-related application,” Water Sci. Technol. Water Supply, vol. 20, no. 6, pp. 2021–2035, 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Il Lee, J.-G. Han, and J.-M. Kim, “Formation and stability of bulk nanobubbles generated by gas-liquid mixing,” 2022, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1600295/v1. Available. [CrossRef]

- C. Chen, J. Li, and X. Zhang, “The existence and stability of bulk nanobubbles: a long-standing dispute on the experimentally observed mesoscopic inhomogeneities in aqueous solutions,” Communications in Theoretical Physics, vol. 72, no. 3. 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. T. Bui, D. C. Nguyen, and M. Han, “Average size and zeta potential of nanobubbles in different reagent solutions,” J. Nanoparticle Res., vol. 21, no. 8, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Z. Guo et al., “Effects of nanobubble water on the growth of: Lactobacillus acidophilus 1028 and its lactic acid production,” RSC Adv., vol. 9, no. 53, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Kim, H. Kim, M. Han, and T. Kim, “Verifying sub-micron (nano) bubbles generation and their fundamental characteristics,” pp. 0–2, 2019.

- J. Atkinson, O. G. Apul, O. Schneider, S. Garcia-Segura, and P. Westerhoff, “Nanobubble Technologies Offer Opportunities to Improve Water Treatment,” Acc. Chem. Res., vol. 52, no. 5, pp. 1196–1205, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. S. Hanam, D. R. Sofia, S. Y. Azhary, C. Panatarani, and I. M. Joni, “Effect of Gas Sources on the Oxygen Transfer Efficiency Produced by Fine Bubbles Generator,” J. Phys. Conf. Ser., vol. 2376, no. 1, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. Kikuchi, S. Nagata, Y. Tanaka, Y. Saihara, and Z. Ogumi, “Characteristics of hydrogen nanobubbles in solutions obtained with water electrolysis,” J. Electroanal. Chem., vol. 600, no. 2, pp. 303–310, 2007. [CrossRef]

- H. Oliveira, A. Azevedo, and J. Rubio, “Nanobubbles generation in a high-rate hydrodynamic cavitation tube,” Miner. Eng., vol. 116, no. October, pp. 32–34, 2018. [CrossRef]

- F. Zhang et al., “Statistical analysis and optimization of reverse anionic hematite flotation integrated with nanobubbles,” J. Mater. Res. Technol., vol. 293, no. 6, p. 106799, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Д. М. Кузьменкoв, А. В. Ольхoвский, В. С. Юнин, and..., “ПРИМЕНЕНИЕ НАНОЧАСТИЦ ДЛЯ ПРОИЗВОДСТВА ПАРА ПОД ДЕЙСТВИЕМ СОЛНЕЧНОГО ИЗЛУЧЕНИЯ,” Вестник Иванoвскoгo …, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://cyberleninka.

- K. Ohgaki, N. Q. Khanh, Y. Joden, A. Tsuji, and T. Nakagawa, “Physicochemical approach to nanobubble solutions,” Chem. Eng. Sci., vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 1296–1300, 2010. [CrossRef]

- R. Sarhan, J. Naser, and G. Brooks, “CFD Modeling of Three-phase Flotation Column Incorporating a Population Balance Model,” Procedia Eng., vol. 184, pp. 313–317, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Nazari, A. Hassanzadeh, Y. He, H. Khoshdast, and P. B. Kowalczuk, “Recent Developments in Generation, Detection and Application of Nanobubbles in Flotation,” Minerals, vol. 12, no. 4, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. D. Michailidi et al., “Journal of Colloid and Interface Science Bulk nanobubbles: Production and investigation of their formation / stability mechanism,” J. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 564, pp. 371–380, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2019.12.093.

- K. K. Thi Phan, T. Truong, Y. Wang, and B. Bhandari, “Nanobubbles: Fundamental characteristics and applications in food processing,” Trends Food Sci. Technol., vol. 95, no. February 2019, pp. 118–130, 2020. [CrossRef]

- El Arwadi and A. S. Zuruzi, “Towards Bulk Nanobubble Generation: Development of a Bulk Nanobubble Generator Based on Hydrodynamic Cavitation,” Int. J. Recent Adv. Mech. Eng., vol. 11, no. 2, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Folden and F. Aschmoneit, “A classification and review of cavitation models with an emphasis on physical aspects of cavitation,” no. August, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ganguli and A. B. Pandit, “Hydrodynamics of liquid-liquid flows in micro channels and its influence on transport properties: A review,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 19, pp. 1–56, 2021. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Simon, O. A. Sapozhnikov, V. A. Khokhlova, L. A. Crum, and M. R. Bailey, “Ultrasonic atomization of liquids in drop-chain acoustic fountains,” J. Fluid Mech., vol. 766, no. March, pp. 129–146, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Sangal, C. H. Keitel, and M. Tamburini, “Observing light-by-light scattering in vacuum with an asymmetric photon collider,” Phys. Rev. D, vol. 104, no. 11, p. L111101, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Barraza, J. G. Ortega-Mendoza, P. Zaca-Morán, N. I. Toto-Arellano, C. Toxqui-Quitl, and J. P. Padilla-Martinez, “Optical cavitation in non-absorbent solutions using a continuous-wave laser via optical fiber,” Opt. Laser Technol., vol. 154, no. January, 2022. [CrossRef]

- H. Tsuge, Micro- and Nanobubbles, Fundamental and Application.

- J. Lee et al., “Refractory oil wastewater treatment by dissolved air flotation, electrochemical advanced oxidation process, and magnetic biochar integrated system,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 36, no. May, pp. 1–11, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. C. O’Hern et al., “Selective ionic transport through tunable subnanometer pores in single-layer graphene membranes,” Nano Lett., vol. 14, no. 3, 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Nazari, A. Davoodabadi, D. Huang, T. Luo, and H. Ghasemi, “On interfacial viscosity in nanochannels,” Nanoscale, 2020, [Online]. Available: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2020/nr/d0nr02294b.

- Abidli, Y. Huang, Z. Ben Rejeb, A. Zaoui, and C. B. Park, “Sustainable and efficient technologies for removal and recovery of toxic and valuable metals from wastewater: Recent progress, challenges, and future perspectives,” Chemosphere, vol. 292, p. 133102, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kurita, I. Chiba, and A. Kijima, “Physical eradication of small planktonic crustaceans from aquaculture tanks with cavitation treatment,” Aquac. Int., vol. 25, no. 6, pp. 2127–2133, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, R. Etchepare, S. Calgaroto, and J. Rubio, “Aqueous dispersions of nanobubbles: Generation, properties and features,” Miner. Eng., vol. 94, no. September 2019, pp. 29–37, 2016. [CrossRef]

- S. Mondal, A. Acharjee, U. Mandal, and B. Saha, “Froth flotation process and its application,” Vietnam J. Chem., vol. 59, no. 4, pp. 417–425, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Liu, Z. Zhang, W. Li, R. Liu, J. Qiu, and S. Wang, “Water purification performance and energy consumption of gradient nanocomposite membranes,” Compos. Part B Eng., vol. 202, no. September, p. 108426, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Peng, L. Chang, P. Li, G. Han, Y. Huang, and Y. Cao, “An overview on the surfactants used in ion flotation,” J. Mol. Liq., vol. 286, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. Yan et al., “Air nanobubbles induced reversible self-assembly of 7S globulins isolated from pea (Pisum Sativum L.),” Food Hydrocoll., vol. 133, no. February, 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Wu, K. Zhang, C. Cen, X. Wu, R. Mao, and Y. Zheng, “Role of bulk nanobubbles in removing organic pollutants in wastewater treatment,” AMB Express, vol. 11, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Patel et al., “Advances in micro- and nano bubbles technology for application in biochemical processes,” Environ. Technol. Innov., vol. 23, p. 101729, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Qin et al., “Impact of Dissolved Oxygen on the Performance and Microbial Dynamics in Side-Stream Activated Sludge Hydrolysis Process,” Water (Switzerland), vol. 15, no. 11, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bianca-Ștefania Zăbavă et al., “Types of Aerators Used in Wastewater Treatment Plants,” 5th Int. Conf. Therm. Equipment, Renew. Energy Rural Dev., no. July, pp. 455–460, 2016, [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/305325229_TYPES_OF_AERATORS_USED_IN_WASTEWATER_TREATMENT_PLANTS.

- H. Sharma and N. Nirmalkar, “Enhanced gas-liquid mass transfer coefficient by bulk nanobubbles in water,” Mater. Today Proc., vol. 57, no. June, pp. 1838–1841, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Reichmann, J. Herath, L. Mensing, and N. Kockmann, “Gas-liquid mass transfer intensification for bubble generation and breakup in micronozzles,” J. Flow Chem., vol. 11, no. 3, pp. 429–444, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Aaltonen et al., “Improving Nickel Recovery in Froth Flotation by Purifying Concentrators Process Water Using Dissolved Air Flotation,” Minerals, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 319, 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. N. Malik, P. C. Ghosh, A. N. Vaidya, and S. N. Mudliar, “Hybrid ozonation process for industrial wastewater treatment: Principles and applications: A review,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 35, p. 101193, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xia and L. Hu, “Theoretical model for micro-nano-bubbles mass transfer during contaminant treatment,” J. Environ. Eng. Sci., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 157–167, 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Hopper and M. C. McCowen, “A Flotation Process for Water Purification,” J. AWWA, vol. 44, no. 8, pp. 719–726, 1952. [CrossRef]

- B. M. Han and S. Dockko, “Zeta potential measurement of bubbles in DAF process,” Water Supply, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 461–466, 1998.

- S. Haris, X. Qiu, H. Klammler, and M. M. A. Mohamed, “The use of micro-nano bubbles in groundwater remediation: A comprehensive review,” Groundw. Sustain. Dev., vol. 11, no. July, p. 100463, 2020. [CrossRef]

- N. Ahmed and G. J. Jameson, “The effect of bubble size on the rate of flotation of fine particles,” Int. J. Miner. Process., vol. 14, no. 3, pp. 195–215, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, L. Ren, and Y. Zhang, “Role of nanobubbles in the flotation of fine rutile particles,” Miner. Eng., vol. 172, p. 107140, 2021. [CrossRef]

- G. L. Collins and G. J. Jameson, “Experiments on the flotation of fine particles. The influence of particle size and charge,” Chem. Eng. Sci., vol. 31, no. 11, pp. 985–991, 1976. [CrossRef]

- M. Maeng, N. K. Shahi, and S. Dockko, “Enhanced flotation technology using low-density microhollow beads to remove algae from a drinking water source,” J. Water Process Eng., vol. 42, no. May, p. 102131, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Habib and S. T. Weinman, “A review on the synthesis of fully aromatic polyamide reverse osmosis membranes,” Desalination, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0011916421000102.

- M. Sumikura, M. Hidaka, H. Murakami, Y. Nobutomo, and T. Murakami, “Ozone micro-bubble disinfection method for wastewater reuse system,” Water Sci. Technol., vol. 56, no. 5, pp. 53–61, 2007. [CrossRef]

- L. Xie et al., “Surface interaction mechanisms in mineral flotation: Fundamentals, measurements, and perspectives,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 295, p. 102491, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Mezule, S. Tsyfansky, V. Yakushevich, and T. Juhna, “A simple technique for water disinfection with hydrodynamic cavitation: Effect on survival of Escherichia coli,” Desalination, vol. 248, no. 1–3, pp. 152–159, 2009. [CrossRef]

- Z. Pourkarimi, B. Rezai, and M. Noaparast, “Nanobubbles effect on the mechanical flotation of phosphate ore fine particles,” Physicochem. Probl. Miner. Process., vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 278–292, 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. Amaral Filho, A. Azevedo, R. Etchepare, and J. Rubio, “Removal of sulfate ions by dissolved air flotation (DAF) following precipitation and flocculation,” Int. J. Miner. Process., vol. 149, pp. 1–8, 2016. [CrossRef]

- R. Prakash, S. K. Majumder, and A. Singh, “Flotation technique: Its mechanisms and design parameters,” Chem. Eng. Process. - Process Intensif., vol. 127, pp. 249–270, 2018. [CrossRef]

- H. Polat; D. Erdogan, “Heavy metal removal from waste water by ion flotation.” pp. 267–273, 2007.

- Virginia Mazzini; Neil R. Cameron; Stephen Hyde; Erns Kenndler, “Substantia,” An Int. J. Hist. Chem., vol. 4, no. September, 2020.

- F. Asghar et al., “Fabrication and prospective applications of graphene oxide-modified nanocomposites for wastewater remediation,” RSC Adv., vol. 12, no. 19, pp. 11750–11768, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, H. Oliveira, and J. Rubio, “Bulk nanobubbles in the mineral and environmental areas: Updating research and applications,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 271, p. 101992, 2019. [CrossRef]

- D. Su, L. Zhang, J. Guo, S. Liu, and B. Li, “Adsorption and accumulation mechanism of N2 on groove-type rough surfaces: A molecular simulation study,” J. Mol. Liq., vol. 366, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. N. Narayanan et al., “Synthesis of reduced graphene oxide-Fe 3O 4 multifunctional freestanding membranes and their temperature dependent electronic transport properties,” Carbon N. Y., vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 1338–1345, 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. Matsumoto et al., “An investigation of nanobubbles in aqueous solutions for various applications,” Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp., vol. 8, no. 6, pp. 91–97, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Jiang et al., “Surface change of microplastics in aquatic environment and the removal by froth flotation assisted with cationic and anionic surfactants,” Water Res., vol. 233, no. January, p. 119794, 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang et al., “A feasible strategy for separating oxyanions-loaded microfine Fe-MOF adsorbents from solution by bubble flotation,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 454, no. P3, p. 140299, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Q. Long et al., “Enhancing flotation separation of fine copper oxide from silica by microbubble assisted hydrophobic aggregation,” Miner. Eng., vol. 189, no. September, 2022. 2022. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhang, H. Y. Li, C. G. Xu, Z. Y. Huang, and X. S. Li, “Research progress on the effects of nanoparticles on gas hydrate formation,” RSC Adv., 2022, [Online]. Available: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2022/ra/d2ra03376c.

- M. Kukizaki and M. Goto, “Size control of nanobubbles generated from Shirasu-porous-glass (SPG) membranes,” J. Memb. Sci., vol. 281, no. 1–2, pp. 386–396, 2006. [CrossRef]

- S. Velusamy, A. Roy, S. Sundaram, and T. Kumar Mallick, “A Review on Heavy Metal Ions and Containing Dyes Removal Through Graphene Oxide-Based Adsorption Strategies for Textile Wastewater Treatment,” Chem. Rec., vol. 21, no. 7, pp. 1570–1610, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. Eisavi and F. Ahmadi, “Fe3O4@SiO2-PMA-Cu magnetic nanoparticles as a novel catalyst for green synthesis of β-thiol-1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazoles,” Sci. Rep., vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–19, 2022. [CrossRef]

- G. Z. Kyzas et al., “Nanobubbles effect on heavy metal ions adsorption by activated carbon,” Chem. Eng. J., vol. 356, no. September 2018, pp. 91–97, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. C. Madzokere, K. Rusere, and H. Chiririwa, “Nano-Silica based mineral flotation frother: Synthesis and flotation of Platinum Group Metals (PGMs),” Miner. Eng., vol. 166, no. April, pp. 1–10, 2021. [CrossRef]

- X. L. Yu and Y. He, “Development of a rapid and simple method for preparing tea-leaf saponins and investigation on their surface tension differences compared with tea-seed saponins,” Molecules, vol. 23, no. 7, 2018. [CrossRef]

- X. Z. Yuan, Y. T. Meng, G. M. Zeng, Y. Y. Fang, and J. G. Shi, “Evaluation of tea-derived biosurfactant on removing heavy metal ions from dilute wastewater by ion flotation,” Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp., vol. 317, no. 1–3, pp. 256–261, 2008. [CrossRef]

- W. Zhou, J. Niu, W. Xiao, and L. Ou, “Adsorption of bulk nanobubbles on the chemically surface-modified muscovite minerals,” Ultrason. Sonochem., vol. 51, no. August 2018, pp. 31–39, 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. Li et al., “Synergistic effect of polyvinyl alcohol sub-layer and graphene oxide condiment from active layer on desalination behavior of forward osmosis membrane,” J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng., vol. 112, pp. 366–376, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhou et al., “Generation of Nano-Bubbles by NaHCO3 for Improving the FO Membrane Performance,” Membranes (Basel)., vol. 13, no. 4, 2023. [CrossRef]

- K. Wang, X. Wang, B. Januszewski, Y. Liu, D. Li, and ..., “Tailored design of nanofiltration membranes for water treatment based on synthesis–property–performance relationships,” Chem. Soc. …, 2022, [Online]. Available: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlehtml/2022/cs/d0cs01599g.

- F. Eklund, M. Alheshibri, and J. Swenson, “Differentiating bulk nanobubbles from nanodroplets and nanoparticles,” Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 53, p. 101427, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Rajapakse, M. Zargar, T. Sen, and M. Khiadani, “Effects of influent physicochemical characteristics on air dissolution, bubble size and rise velocity in dissolved air flotation: A review,” Sep. Purif. Technol., vol. 289, p. 120772, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ferrari and A. Benedetti, “Superhydrophobic surfaces for applications in seawater,” Adv. Colloid Interface Sci., vol. 222, no. January, pp. 291–304, 2015. [CrossRef]