1. Introduction

In recent years, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have been playing an important role in critical missions such as reconnaissance, tracking, and mapping in harsh environmental conditions [

1,

2]. Especially in civilian and military applications, the autonomous navigation and mission planning capabilities of UAVs are becoming increasingly important [

1]. In order for these missions to be successfully accomplished, it is critical for UAVs to be able to accurately and reliably measure their altitude.

Traditional altitude measurement methods, such as Global Positioning System (GPS) and barometric sensors, are sometimes inadequate due to the adverse effects of weather conditions and signal constraints [

3,

4]. For example, in environments where the GPS signal is weak or obstructed, altitude information may lose its accuracy. Similarly, barometric sensors can be affected by changes in air pressure, producing inconsistent data [

4]. This situation directly affects the safety and effectiveness of UAV operations. Cost is also an important issue for laser measurements [

5].

Therefore, alternative and more reliable methods for altitude estimation of UAVs are needed. Image-based altitude and state estimation has recently emerged as an approach that has attracted attention in this field [

6,

7]. In particular, estimating altitude using NADIR (downward-facing) images obtained from cameras mounted under UAVs offers a potential solution in overcoming the limitations of existing sensors [

8].

Deep learning techniques have achieved great success in the fields of image processing and computer vision, and are increasingly being used in UAV applications as well [

9,

10]. Deep learning models that can estimate depth or altitude from a single image increase the autonomous navigation and environmental sensing capabilities of UAVs [

8]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs), in particular, have become an effective tool in this field due to their ability to learn and generalize complex image features [

9].

This study investigates altitude estimation using deep learning techniques with NADIR images obtained by UAVs. In the literature, there are several studies on depth and altitude estimation using monocular cameras [

8,

11]. For example, Zhang et al. [

8] estimated altitude with deep learning from monocular images and obtained successful results. However, these studies were often conducted with limited data sets and not NADIR images or under specific conditions.

This approach aims to explore the potential of altitude estimation using a large dataset of NADIR images collected at different altitudes and locations, potentially contributing to improved performance in various environmental conditions. For this purpose, a deep learning-based altitude estimation model has been developed using a pre-trained CNN model. The model has been trained and tested with real flight data.

he results suggest that this model could serve as a potential alternative or complement to traditional GPS and barometric sensors. Especially in cases where the GPS signal is weak or barometric sensors produce inconsistent data, the proposed method can contribute to the safe and effective operation of UAVs.

In the continuation of this study, firstly, the method and data set used will be explained in detail, then the performance of the model will be evaluated and the results will be discussed.

2. Materials and Methods

This study aims to estimate altitude using deep learning techniques from unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) images. The method consists of three main stages: data preprocessing, model training, and model testing.

2.1. Data Preprocessing

In the first stage, NADIR images taken by the UAV were processed and made suitable for the deep neural network model. The images were collected by the Mavic 2 Pro and Mavic 2 Zoom UAVs equipped with GPS-enabled cameras at different altitudes and locations. GPS latitude, longitude and altitude information were obtained using the EXIF data of each image, and

Piexif and

Exifread libraries were used for these data [

12].

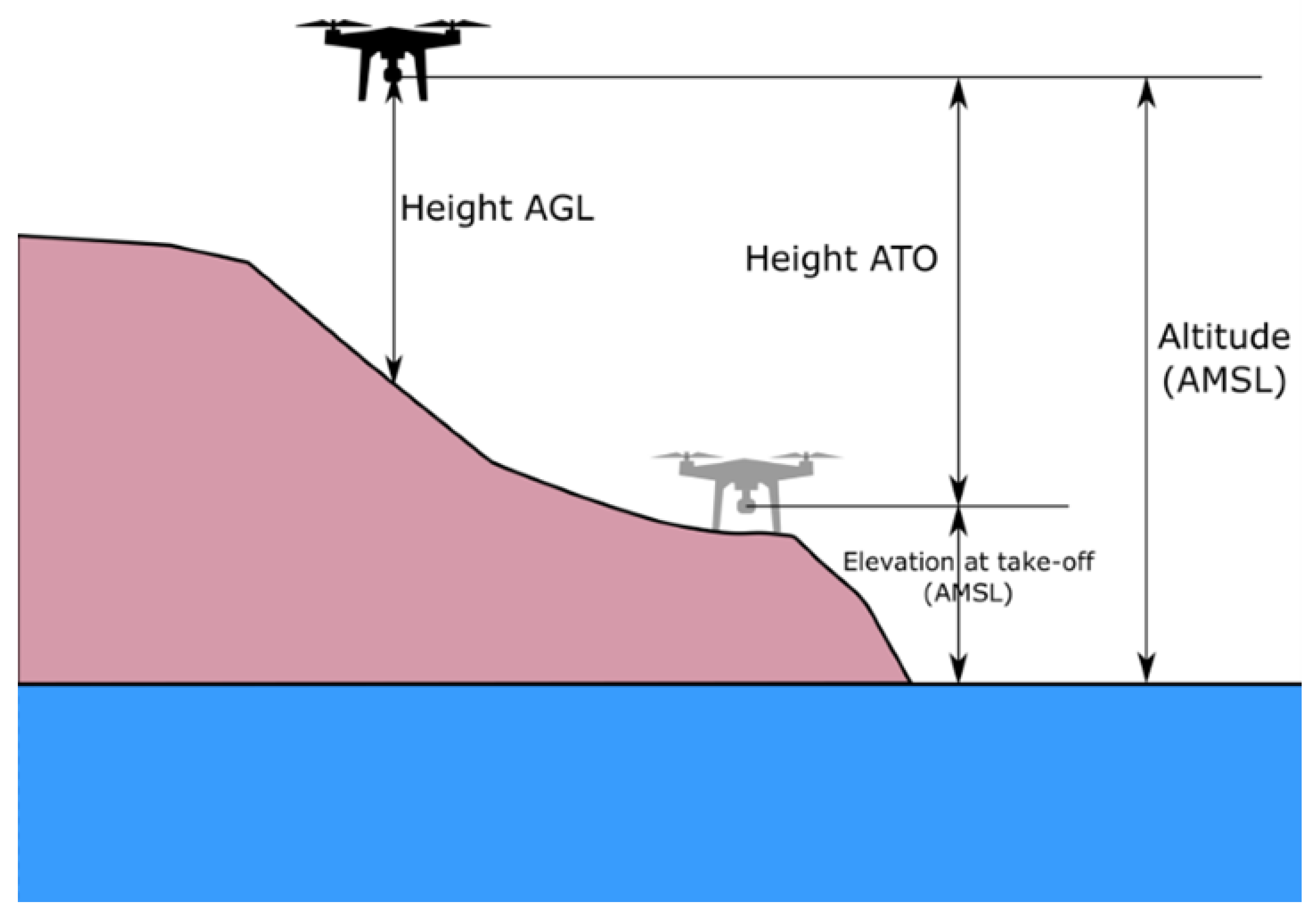

Figure 1 visualizes the process of obtaining the altitude value through Digital Elevation Map.

A high-resolution (25 meters GSD) Digital Elevation Model (DEM) file was used to obtain above ground level (AGL) altitude values [

14]. The GPS coordinates (WGS84) have been converted to DEM’s coordinate system (UTM Zone 36N) using the Pyproj library for a more accurate calculation. Thanks to this transformation, it was ensured that the coordinates for each data point were exactly matched and the most accurate ground surface height information was obtained through DEM. The conversion of GPS coordinates to UTM coordinates [

15] is performed with the following equation:

Here,

is the longitude,

is the central meridian,

is latitude,

is the scale factor (usually 0.9996),

N is the radius of curvature, calculated as

.

2.1.1. AGL Determination

The flight altitude (AGL) of the UAV is calculated by subtracting the altitude in the numerical altitude model from the GPS altitude information obtained from the image’s EXIF data:

Since different camera models have different focal lengths and sensor sizes, altitude values are scaled depending on the camera model. For example, for the L1D-20c (Mavic 2 Pro) camera model, the scaling coefficient

k is calculated as follows [

16]:

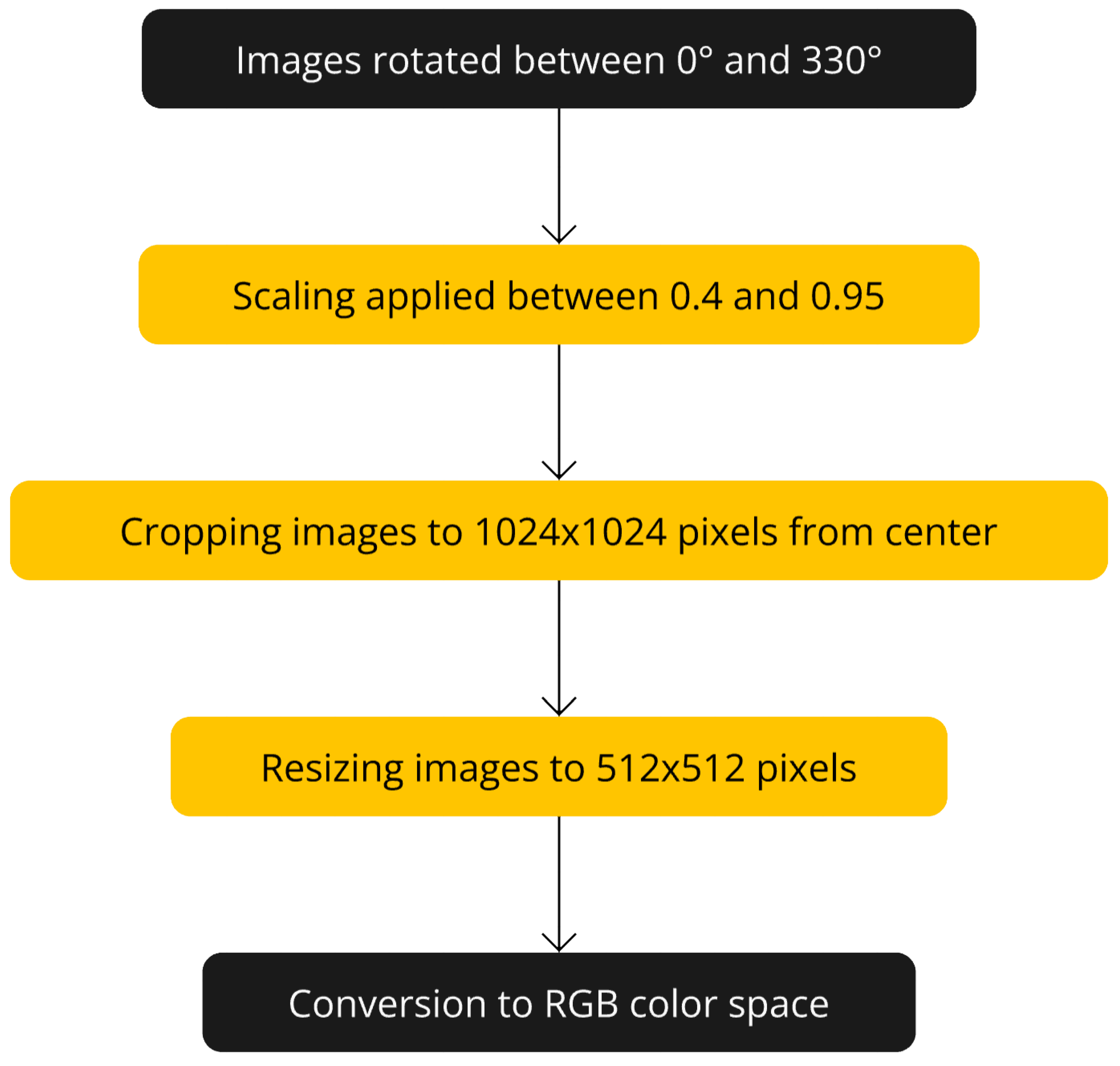

Images were rotated from

to

at 30-degree intervals to increase the model’s ability to generalize to images at different angles (see

Figure 3). To simulate images captured from various altitudes, zooming transformations with scaling factors ranging from 0.4 to 0.95 were applied during the preprocessing stage. This approach generated data samples resembling images taken from different heights, enhancing the model’s robustness to variations in altitude. After rotating and zooming, the images were cropped from the center to

pixels and resized to

pixels. All images have been converted to RGB color space.

Figure 4 shows a flowchart of the data increment steps.

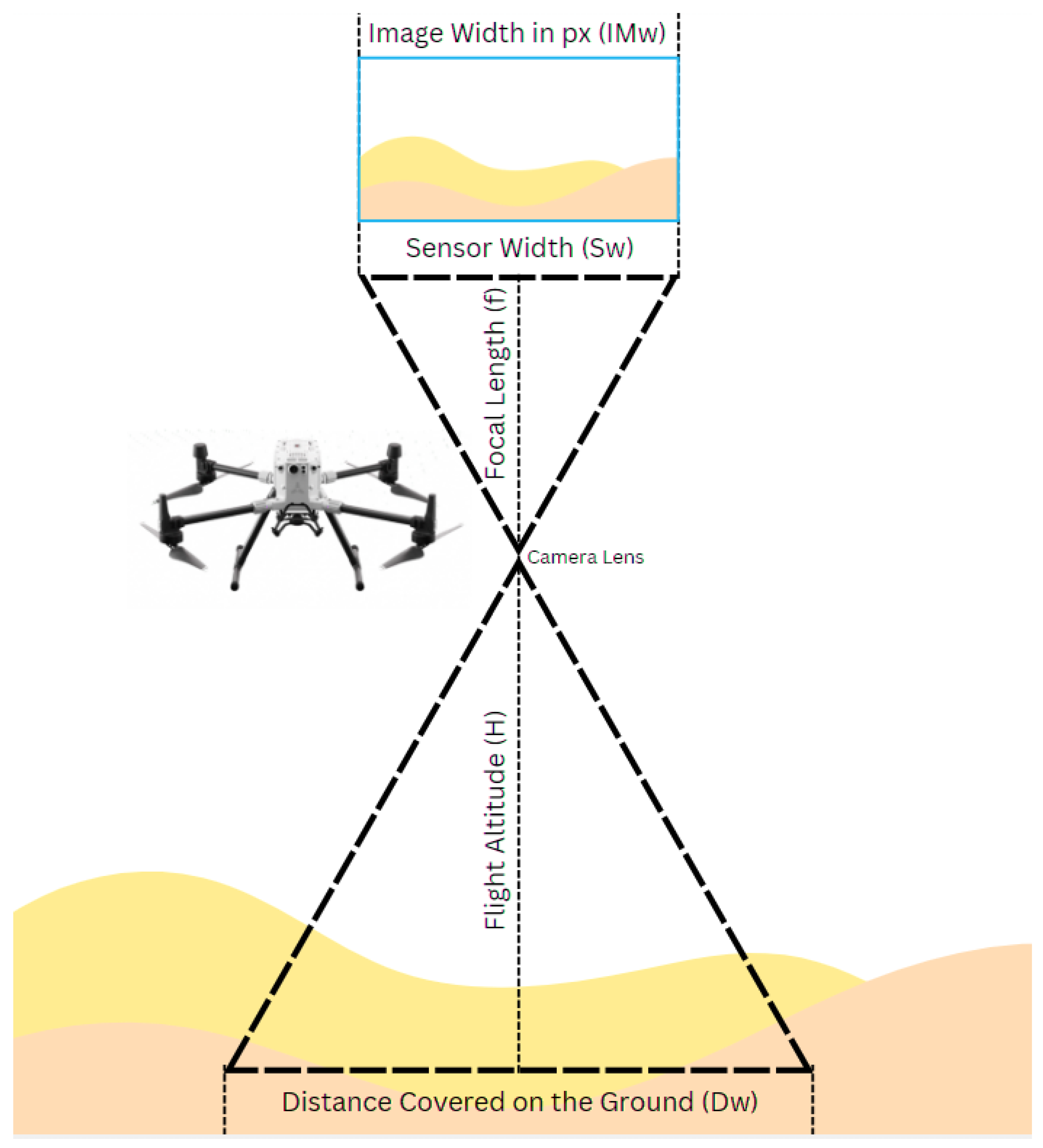

Figure 2.

Ground distance covered based on camera parameters and altitude [

17].

Figure 2.

Ground distance covered based on camera parameters and altitude [

17].

The dataset contains more than 300,000 images in total and covers different weather conditions (sunny, cloudy), different light conditions (sunrise, sunset, noon) and different terrain types (city, forest, farmland). This diversity aims to increase the generalization ability of the model. The calculated flight altitude has been added to the EXIF data of the images under the GPS Altitude label. The processed images are saved in a specific output directory with file names that reflect the transformations applied.

2.2. Neural Network Training

In the second stage, a deep neural network model was trained using pre-processed images. The file names and corresponding altitude values of the processed images are collected in a CSV file. The data was randomly divided into 80% training and 20% validation. The image pixel values are scaled to the range [0,1]. However, no additional augmentations have been made here because the basic data increments have already been implemented.

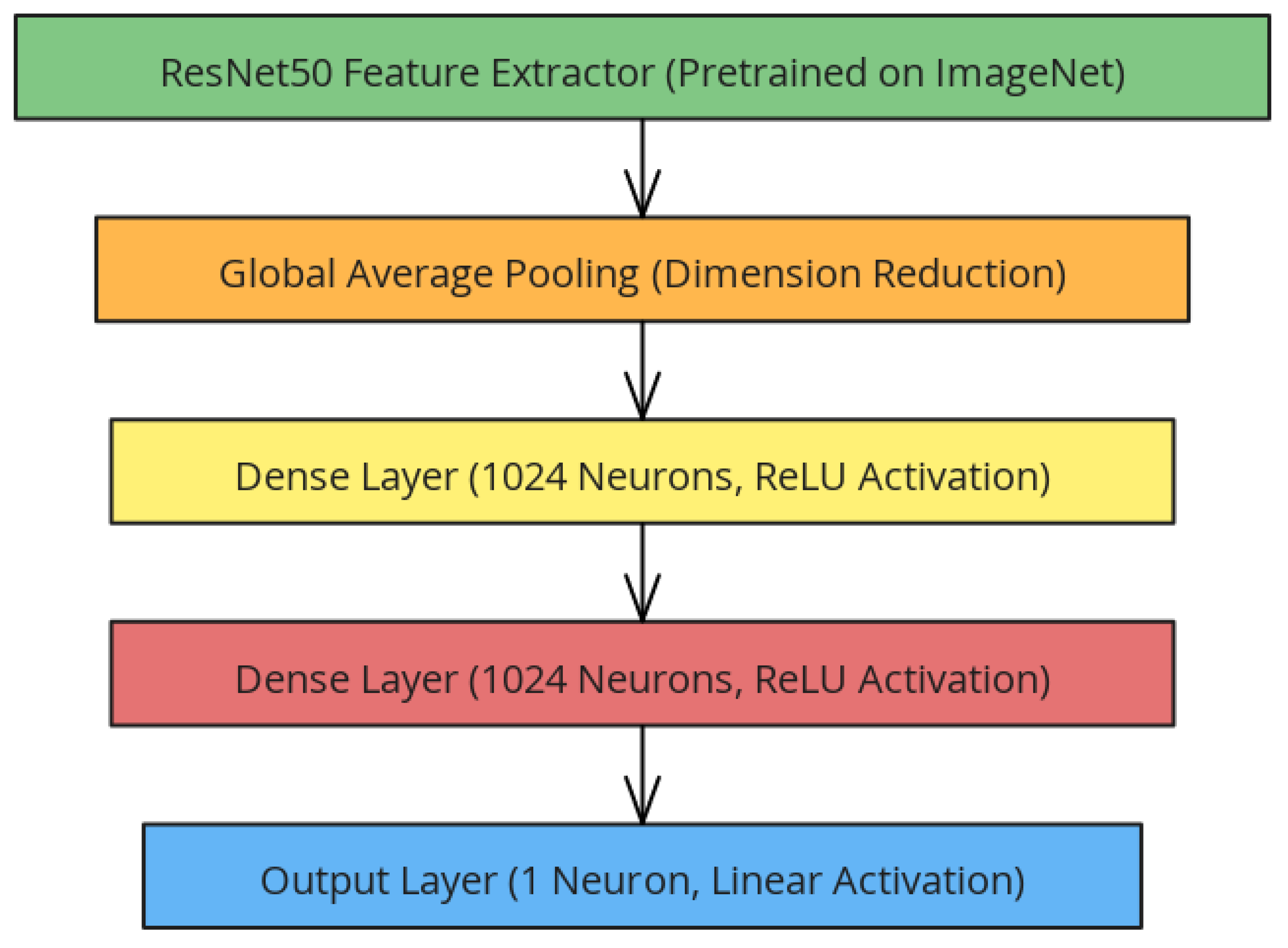

The ResNet50 model, which was previously trained on the ImageNet dataset, was used as a base model. The final classification layers of the model are removed and adapted for transfer learning. Global average pooling was used to reduce the size of the feature maps, then two fully connected layers with 1024 neurons were added, and ReLU was used as the activation function. A single neuron with a linear activation function has been added for altitude estimation. With this structure, the total number of parameters of the model is 26,736,513, of which 26,683,393 are trainable and 53,120 are non-trainable parameters (see

Figure 5).

The model is compiled using the Adam optimization algorithm and the mean square error (MSE) loss function, and a learning rate is set as

. During the training process, the model was trained over 200 epochs with a batch size of 16. Special callback functions were used to record the model at specific steps and at the end of each epoch. The mean square error (MSE) used as a loss function is defined as follows:

where

is the real altitude value,

is the altitude value predicted by the model.

2.3. Evaluation

In the final stage, the trained model was tested on new images and its performance was evaluated. GPS latitude, longitude and altitude information of each test image were extracted using the Exifread library.

The distance of the locations where the test images were taken to the terrain was obtained using the DEM and coordinate transformations used earlier.

Test images were processed by reading them in RGB format, cropping them to

pixels from the center, and subsequently resizing them to

pixels using the nearest neighbour interpolation method. The pixel values are scaled to the range [0,1]. Processed test images were given to the model and altitude estimates were obtained. The difference between the estimated altitude value and the actual altitude value was found for each image. The mean absolute error (MAE) was calculated as:

3. Results

The performance of the trained deep learning model was evaluated using metrics such as MAE, MSE, RMSE and (coefficient of determination) calculated on the test dataset.

At the end of the training process, the model with the best performance was recorded. The performance metrics of this model in the test dataset are as follows:

Mean Absolute Error (MAE): 11.804 meters

Mean Square Error (MSE): 500.569

Root Mean Square Error (RMSE): 22.3734 meters

Score: 0.9712

Number of Instances: 170

The MAE value shows that there is an average deviation of about 11.8 meters in the predictions of the model. This means that the model has an acceptable level of accuracy in practical applications.

The RMSE value of 22.3734 meters provides information about the standard deviation of the prediction errors, allowing us to evaluate the overall error distribution of the model.

The score of 0.9712 shows how well the model fits the data and its predictive power. An value close to 1 indicates that the model is able to predict the dependent variable (altitude) from the independent variables (image data) with high accuracy.

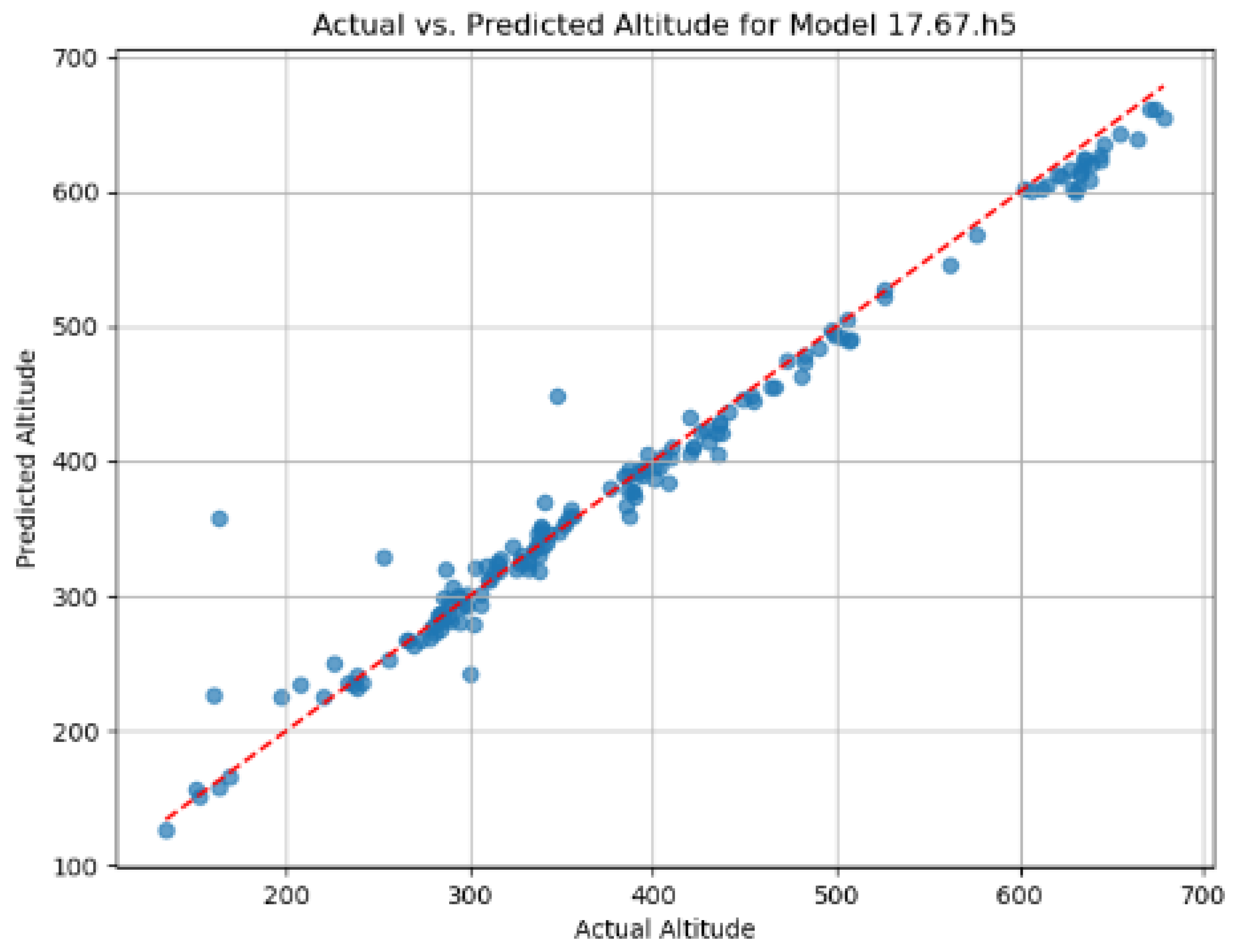

Figure 6 compares the model’s predicted altitude values with the actual altitude values. The red dashed line in the graph represents the ideal direction, and the fact that the majority of the data is distributed close to this line reveals that the model’s predictions are highly accurate.

In

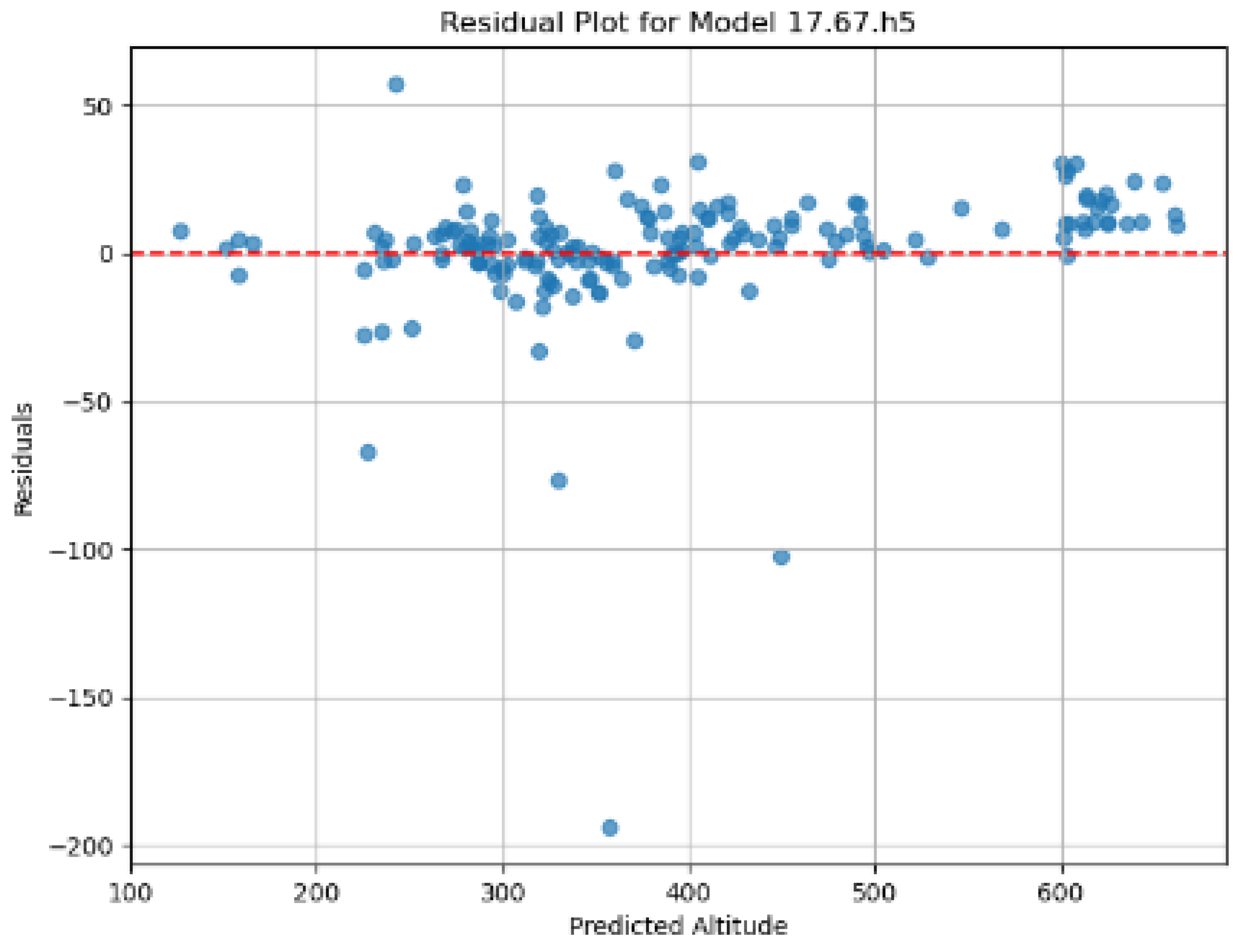

Figure 7, which shows the distribution of residuals (errors) calculated according to the predicted altitude values, the random distribution of residuals around the zero line shows that the model does not make a systematic error and has a balanced error distribution in the estimates. Although there are some outliers, the model appears to fit well with the data overall.

4. Discussion

In the analysis of the model’s prediction errors, relatively low deviations were observed at low and medium altitudes (100–300 meters). However, occasional significant deviations appear at higher altitudes (especially above 300 meters), indicating that the model’s predictive accuracy may decline at these altitudes. Instead of a uniform increase in error, the model shows sporadic larger errors at higher altitudes. Additionally, a slight decrease in model performance was observed in some images, potentially due to complex surface characteristics such as dense vegetation or water surfaces. Future studies could explore whether these surface characteristics impact model accuracy. These findings suggest that the model may be influenced by altitude and surface characteristics, and it could be valuable to examine the impact of these factors in more detail in future research.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to estimate altitude with deep learning techniques using NADIR images obtained from cameras mounted under UAVs. The developed deep learning model demonstrated promising results in estimating altitude from UAV images. The obtained error rates and the coefficient of determination suggest the potential of the model for practical applications.

These results suggest the potential of the model for UAV applications in urban environments, such as autonomous navigation and mission planning. This study also presents an alternative approach to altitude estimation compared to traditional methods relying on GPS and barometric sensors, potentially contributing to the field of UAV technology.

5.1. Future Work

In the future, the adaptation of the model to different UAV platforms, training it with more diverse data sets, and integration with other navigation systems can be worked on. It is aimed to improve the performance of the model in challenging conditions such as dense vegetation and water surfaces. In addition, the performance of the model can be improved by combining it with other sensor data (e.g., IMU data) and making more accurate labeling with a LIDAR sensor.

Sharing the dataset and model as open source will contribute to other researchers making progress in this field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E.A.; methodology, A.E.A.; software, A.E.A.; validation, A.E.A.; formal analysis, A.E.A.; investigation, A.E.A.; resources, A.E.A.; data curation, A.E.A.; writing—original draft preparation, A.E.A.; writing—review and editing, A.E.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is not publicly available.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank everyone who provided support for data collection and valuable feedback throughout the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Valavanis, K.P.; Vachtsevanos, G.J. (Eds.) Handbook of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles; Springer Reference: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Colomina, I.; Molina, P. Unmanned aerial systems for photogrammetry and remote sensing: A review. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 92, 79–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eling, C.; Klingbeil, L.; Wieland, M.; Kuhlmann, H. A Precise Position and Attitude Determination System for Lightweight Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spatial Inf. Sci. 2013; XL-1/W2, 113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Barshan, B.; Durrant-Whyte, H.F. Inertial navigation systems for mobile robots. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1995, 11, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siwiec, J. Comparison of Airborne Laser Scanning of Low and High Above Ground Level for Selected Infrastructure Objects. J. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2018, 8, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrabar, S. 3D path planning and stereo-based obstacle avoidance for rotorcraft UAVs. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Nice, France, 22–26 September 2008; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Arafat, M.Y.; Alam, M.M.; Moh, S. Vision-Based Navigation Techniques for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Review and Challenges. Drones 2023, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; He, Z.; Ma, Z.; Jun, P.; Yang, K. VIAE-Net: An End-to-End Altitude Estimation through Monocular Vision and Inertial Feature Fusion Neural Networks for UAV Autonomous Landing. Sensors 2021, 21, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupervasser, O.; Kutomanov, H.; Levi, O.; Pukshansky, V.; Yavich, R. Using deep learning for visual navigation of drone with respect to 3D ground objects. Mathematics 2020, 8, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fragoso, A.T.; Lee, C.T.; McCoy, A.S.; Chung, S.-J. A seasonally invariant deep transform for visual terrain-relative navigation. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurram, A.; Tuna, A.F.; Shen, F.; Urfalioglu, O.; López, A.M. Monocular Depth Estimation through Virtual-World Supervision and Real-World SfM Self-Supervision. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2103.12209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, D. Guide to GPS Positioning, Lecture Notes; 1999.

- Kozmus Trajkovski, K.; Grigillo, D.; Petrovič, D. Optimization of UAV Flight Missions in Steep Terrain. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szypuła, B. Digital Elevation Models in Geomorphology. In Hydro-Geomorphology—Models and Trends; InTech, 2017.

- Snyder, J.P. Map projections: A working manual. Prof. Pap. 1987. [Google Scholar]

- DJI. DJI Mavic 2 Product Information. 2018. Available online: https://www.dji.com/mavic-2/info (accessed on 3 August 2018).

- Skycatch. Ground Sampling Distance (GSD) in Photogrammetry. Available online: https://support.skycatch.com/hc/en-us/articles/12586674429843-FAQ-What-is-Ground-Sampling-Distance-GSD-in-Photogrammetry (accessed on 1 November 2024).

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).