3.2. Shock Absorber Model

The SA model is intended to be used in full-vehicle models to simulate SA inspection methods and safety-relevant driving maneuvers. The model is derived on the basis of the measurements shown. The model is parameterized using the quasi-static and harmonic measurements. The model is validated by comparing the measured and simulated harmonic excitations of all SAs. In addition, the measured and simulated damping forces and the damping work performed for stochastic excitations for SAs 7 and 8 are compared.

A parallel arrangement of a spring, a Dahl- friction model and a F-v characteristic curve is used to represent the intact SA [

29,

30]. The oil and gas loss in the SA affects all three parts. The models for calculating the gas force

and the friction force

remain unchanged. However, the parameters are adjusted according to the degradation condition. The damping force of fluid friction

is multiplied by a degradation factor

at each time step of the numerical simulation. This factor is calculated using a degradation model that can calculate the reduction in damping force in relation to the potential damping force of the intact SA. Formula (

1) represents the calculation of the total damping force.

Table 4.

Formula symbol definition

Table 4.

Formula symbol definition

| Formula Symbol |

Description |

|

Simulation timestep |

| z |

Piston rod displacement; stroke |

|

Piston rod velocity |

|

Area of the piston valve to the rebound chamber |

|

Area of the piston valve to the compression chamber |

|

Volume of the rebound chamber |

|

Volume of the compression chamber |

|

Volume of the reserve chamber |

|

Preasure in rebound chamber |

|

Preasure in compression chamber |

|

Total shock absorber force |

|

Shock absorber gas force |

|

Shock absorber friction force |

|

Shock absorber fluid friction force |

|

Degradation factor |

|

Gas spring stiffness |

|

Slope of the hysteresis loop |

|

saturated quasi-static friction force |

|

Exponent of the hysteresis friction gradient |

|

F-v-characteristic |

|

Volume flow rate |

|

Relative oil volume flow |

|

Relative oil volume flow change |

|

Cavitation treshold velocity |

|

Cavitation factor |

|

Total measured shock absorber force |

|

Total simulated shock absorber force |

|

Total measured shock absorber work |

|

Total simulated shock absorber work |

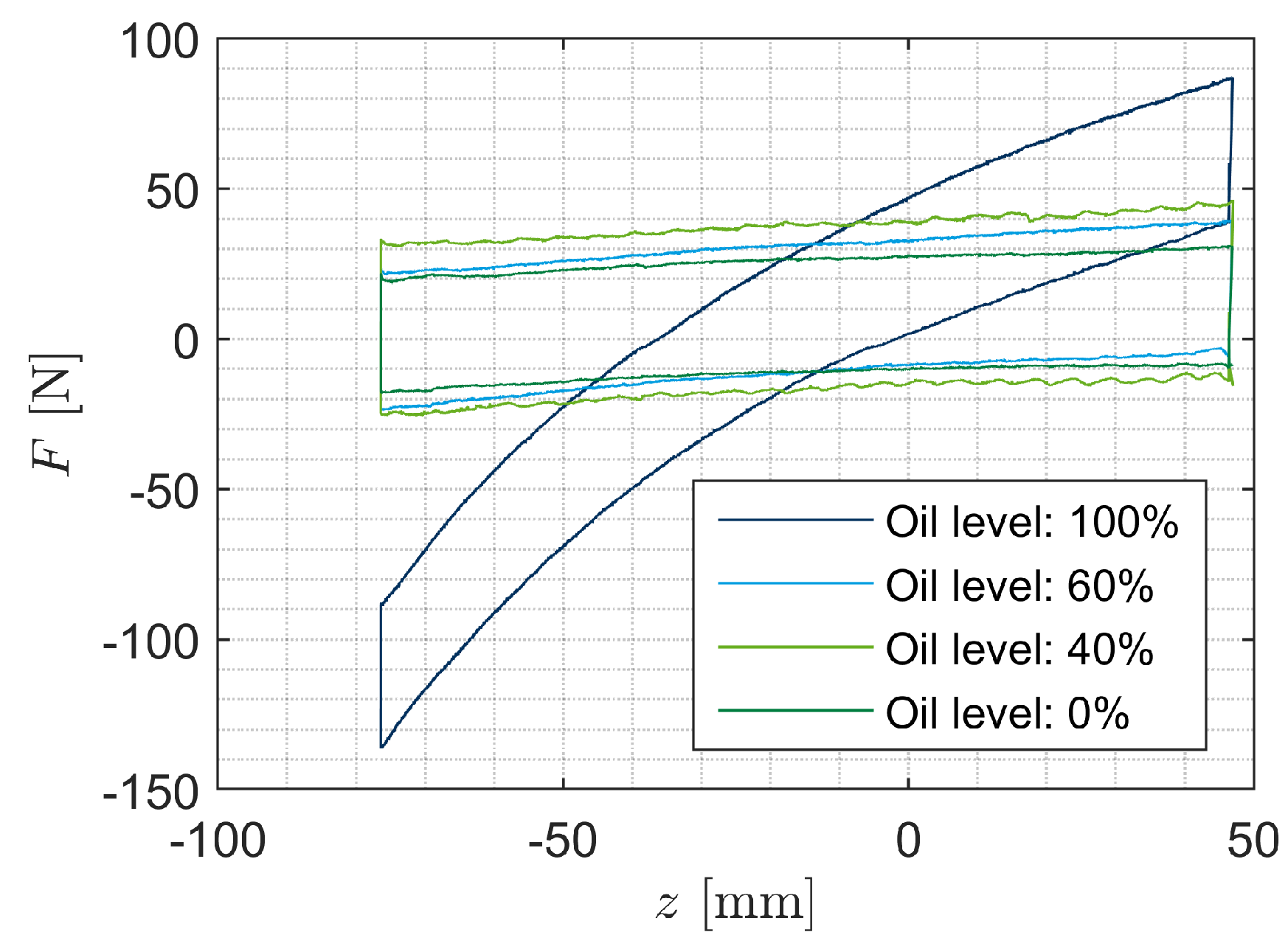

In case of gas loss, the gas pressure and therefore the considered spring force of the SA is reduced. In case of oil loss, the gas volume also expands and the gas pressure in the SA is reduced. The spring force of the SA is defined by the increase in the F-s characteristics of the quasi-static measurements. In case of oil loss, the friction force of the SA increases [

31]. According to Stribeck, the friction force also depends on the velocity [

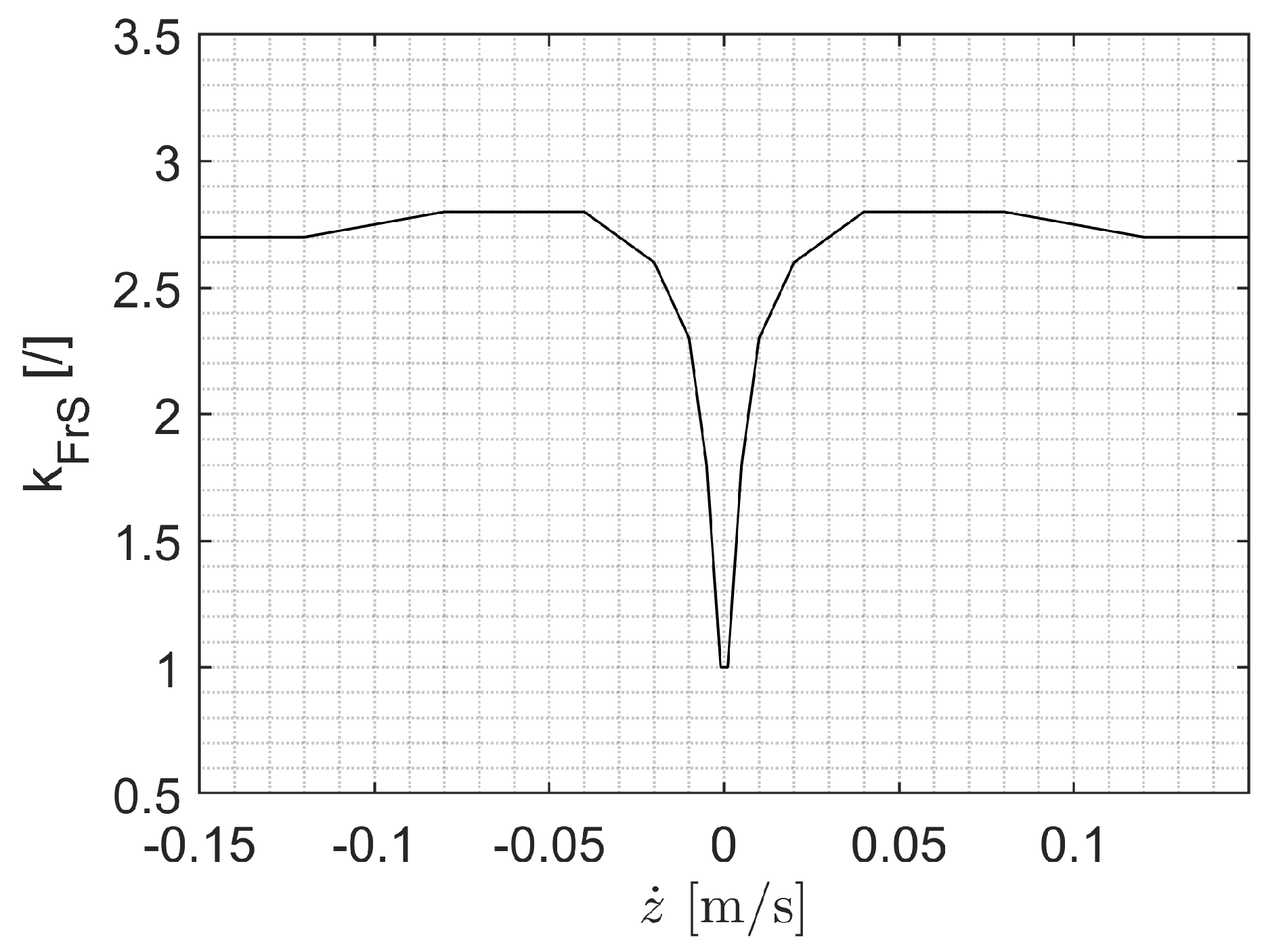

32]. A Dahl-friction model is therefore used, which is scaled via the velocity with a SA-specific Stribeck curve. The saturated Dahl-friction is determined with the quasi-static friction measurements and corresponds to half the hysteresis width of these measurements. The velocity dependence of the friction force is taken from Deubel and is shown in

Figure 12. The parameter

defines the velocity dependence of the friction force. Equation (

2) describes the calculation of the friction force in the SA model.

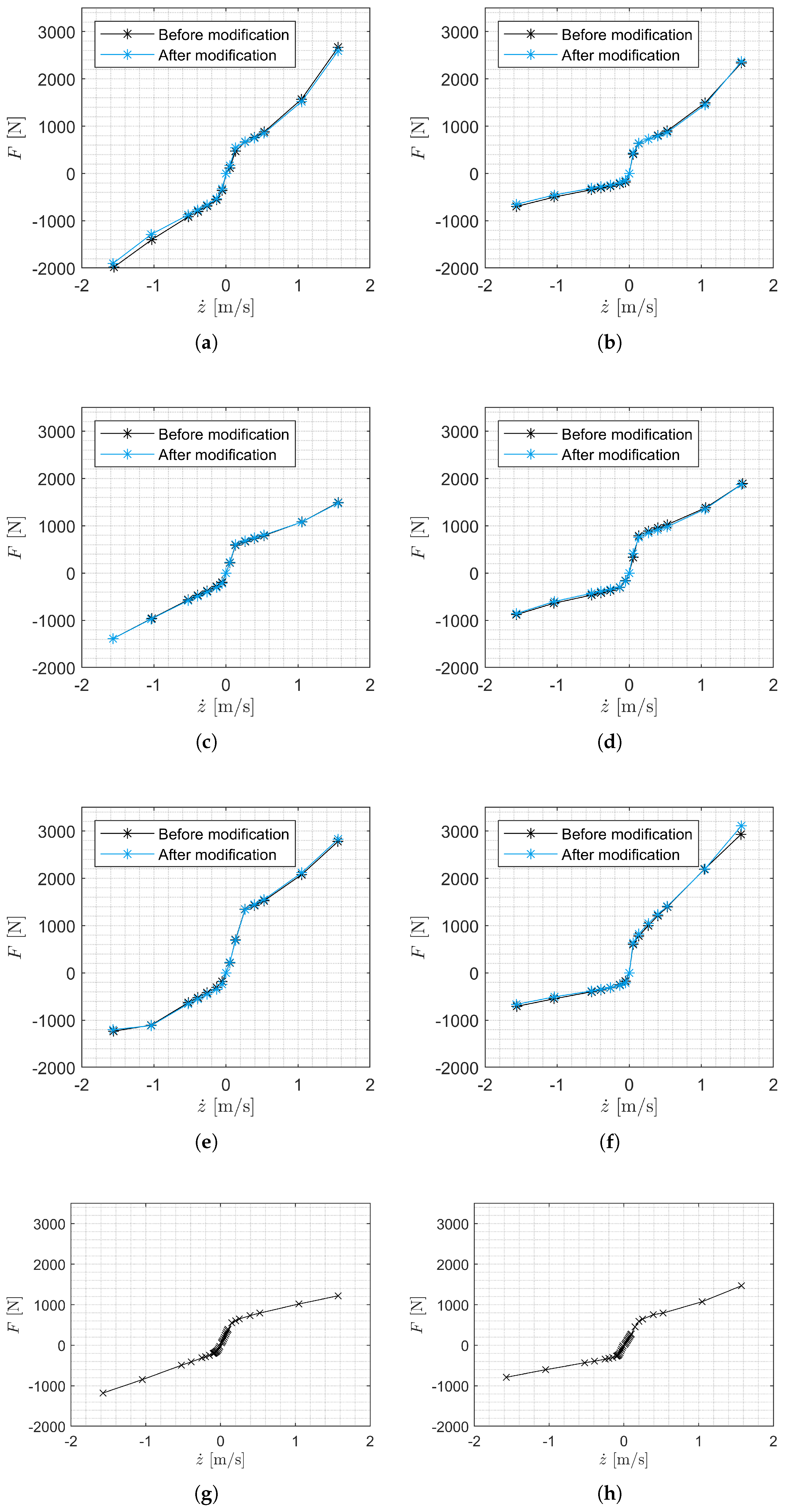

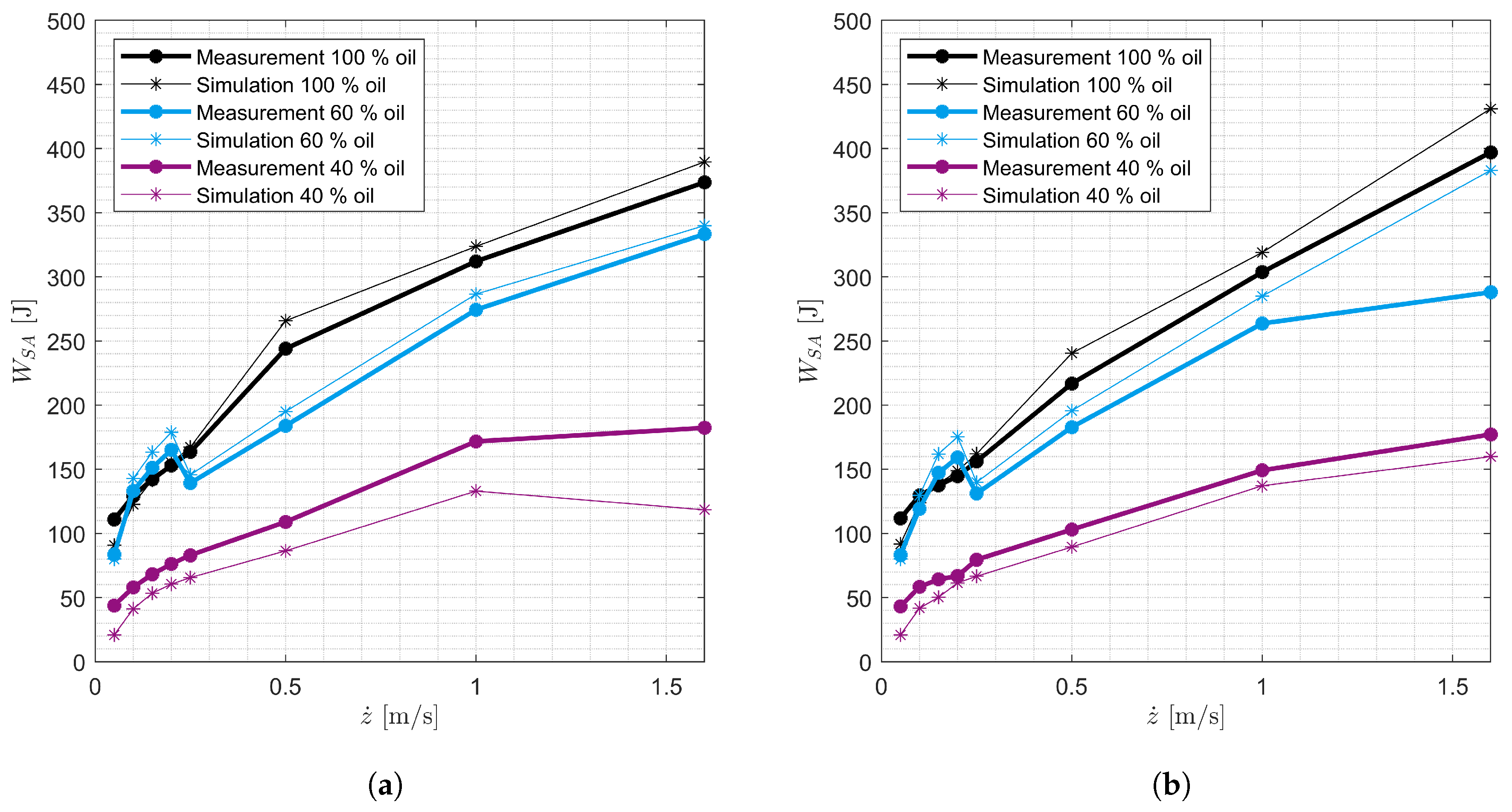

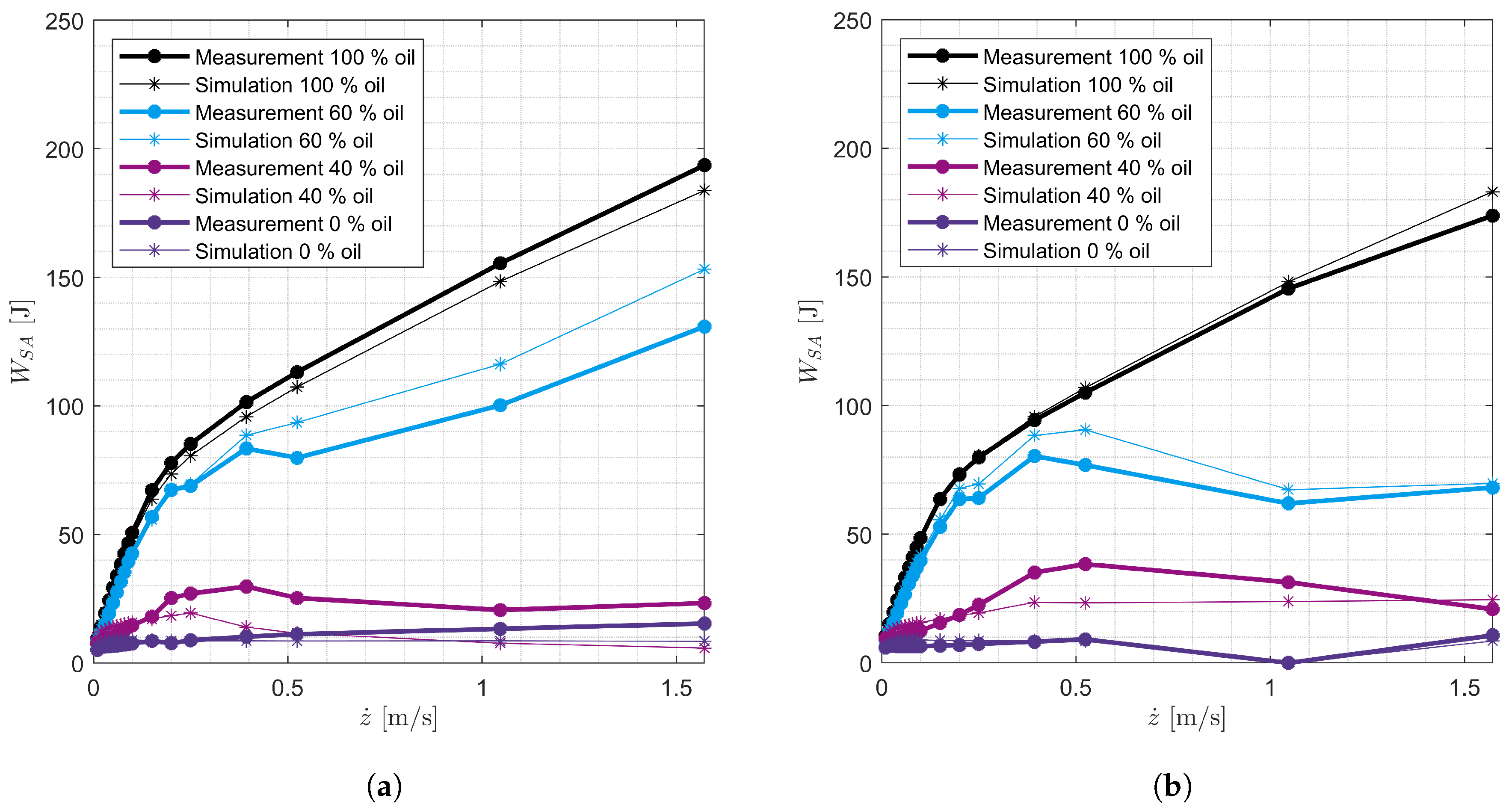

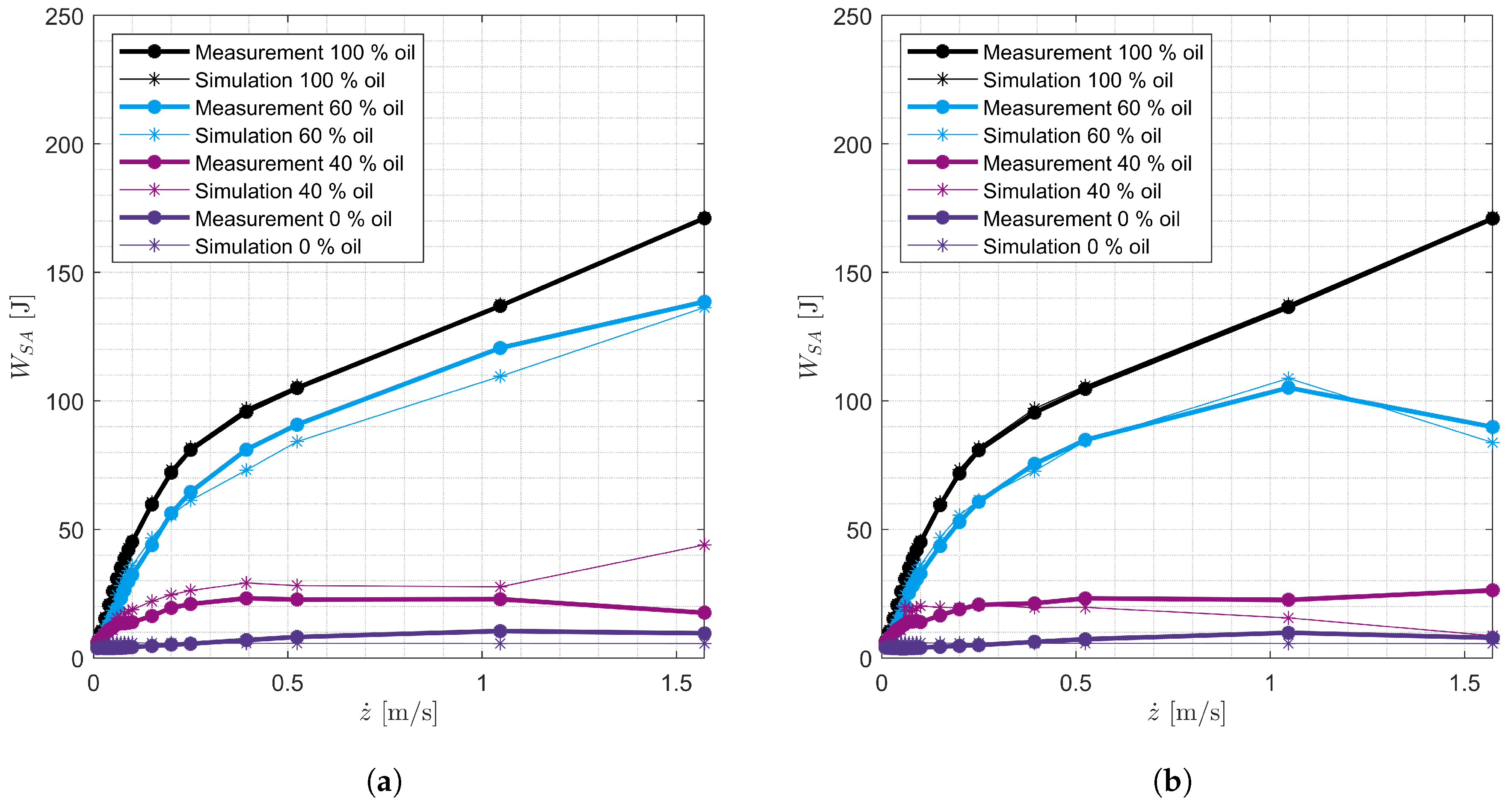

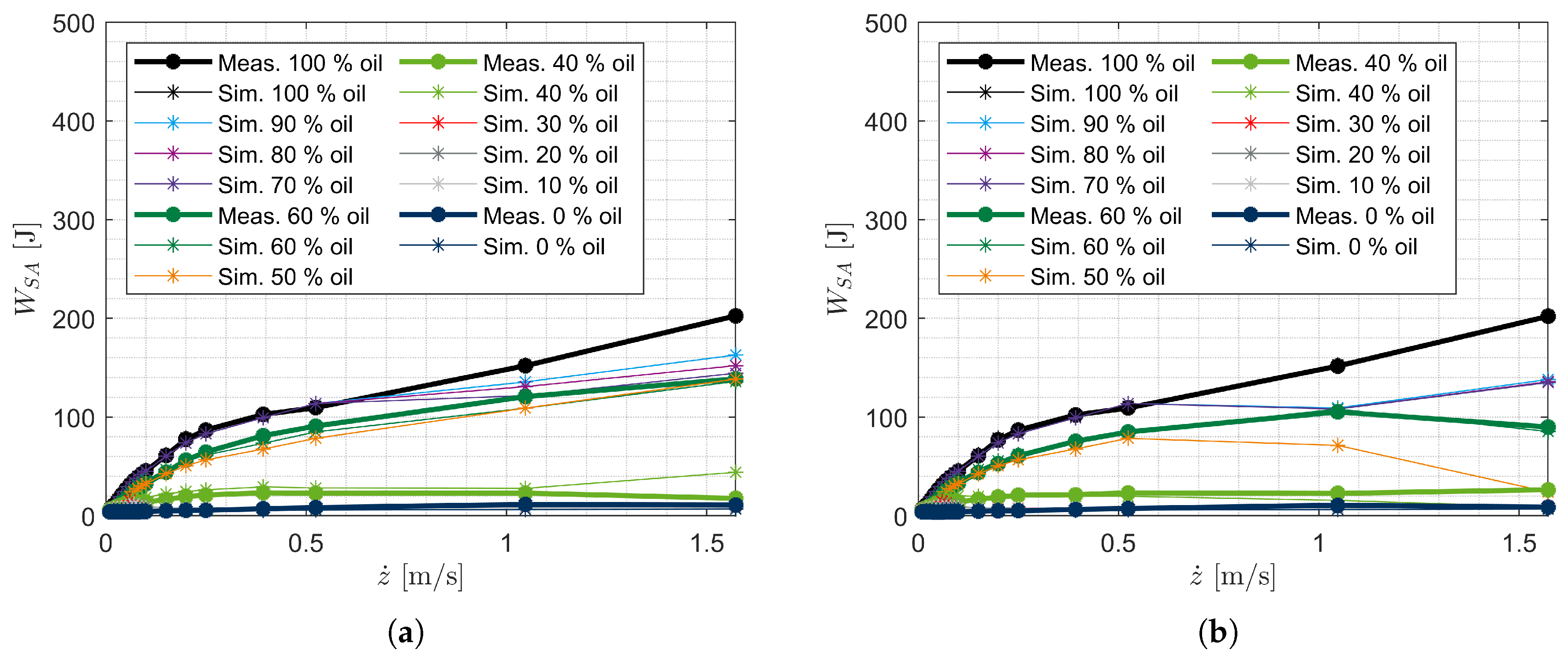

The loss of oil and gas affects the fluid force of the SA the most. The fluid force of the intact SA is calculated using a friction-reduced F-v curve. This characteristic curve is determined from the harmonic measurements of the intact SA at a displacement of 0 mm. The F-v curves of the SAs are shown in

Figure 3. The loss of oil and gas reduces the potential fluid force of the SA depending on its geometry, displacement, and hydraulic characteristics. To represent this reduction in force, the calculated potential damping force of the F-v curve is modeled using a degradation model, which is presented here.

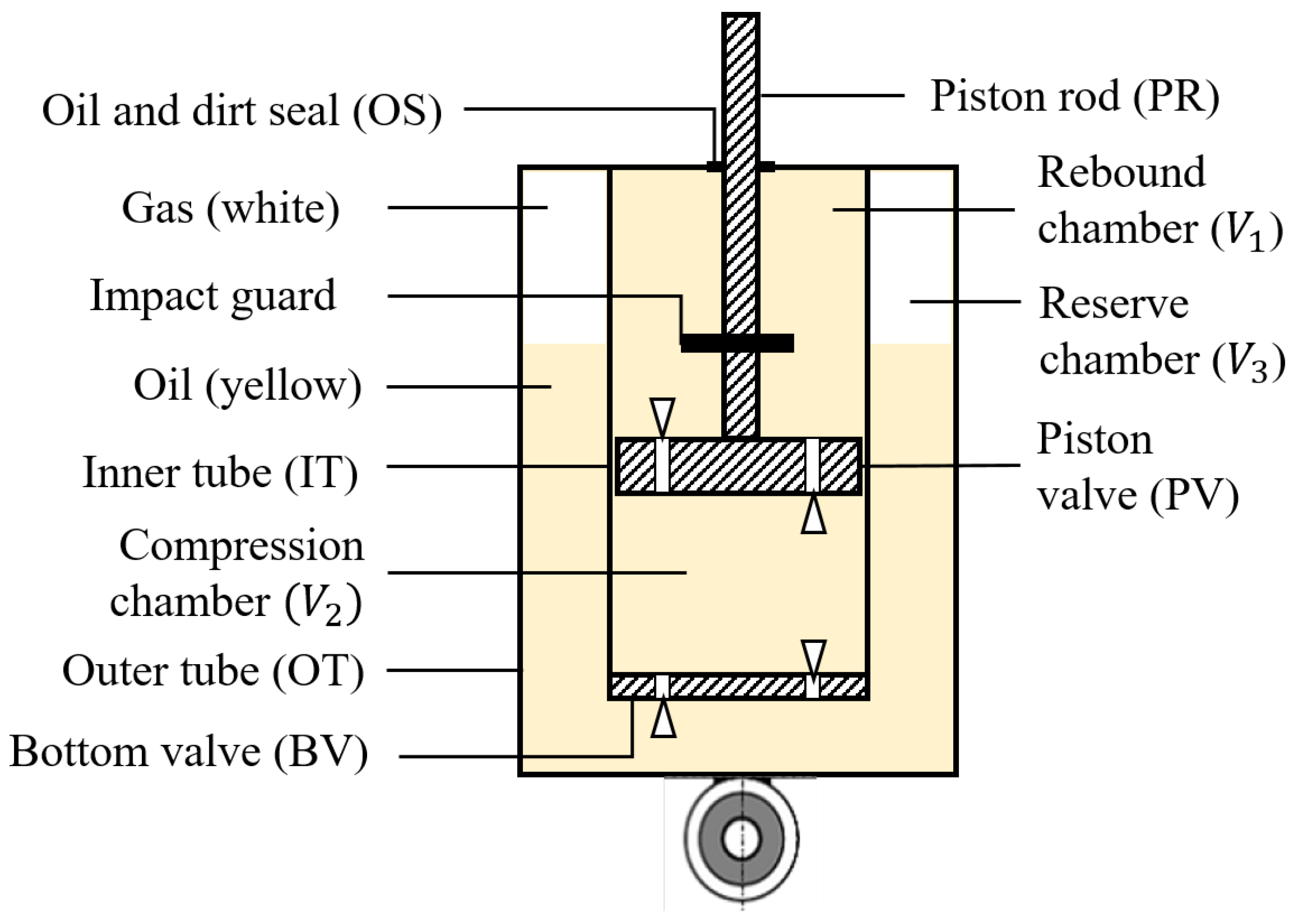

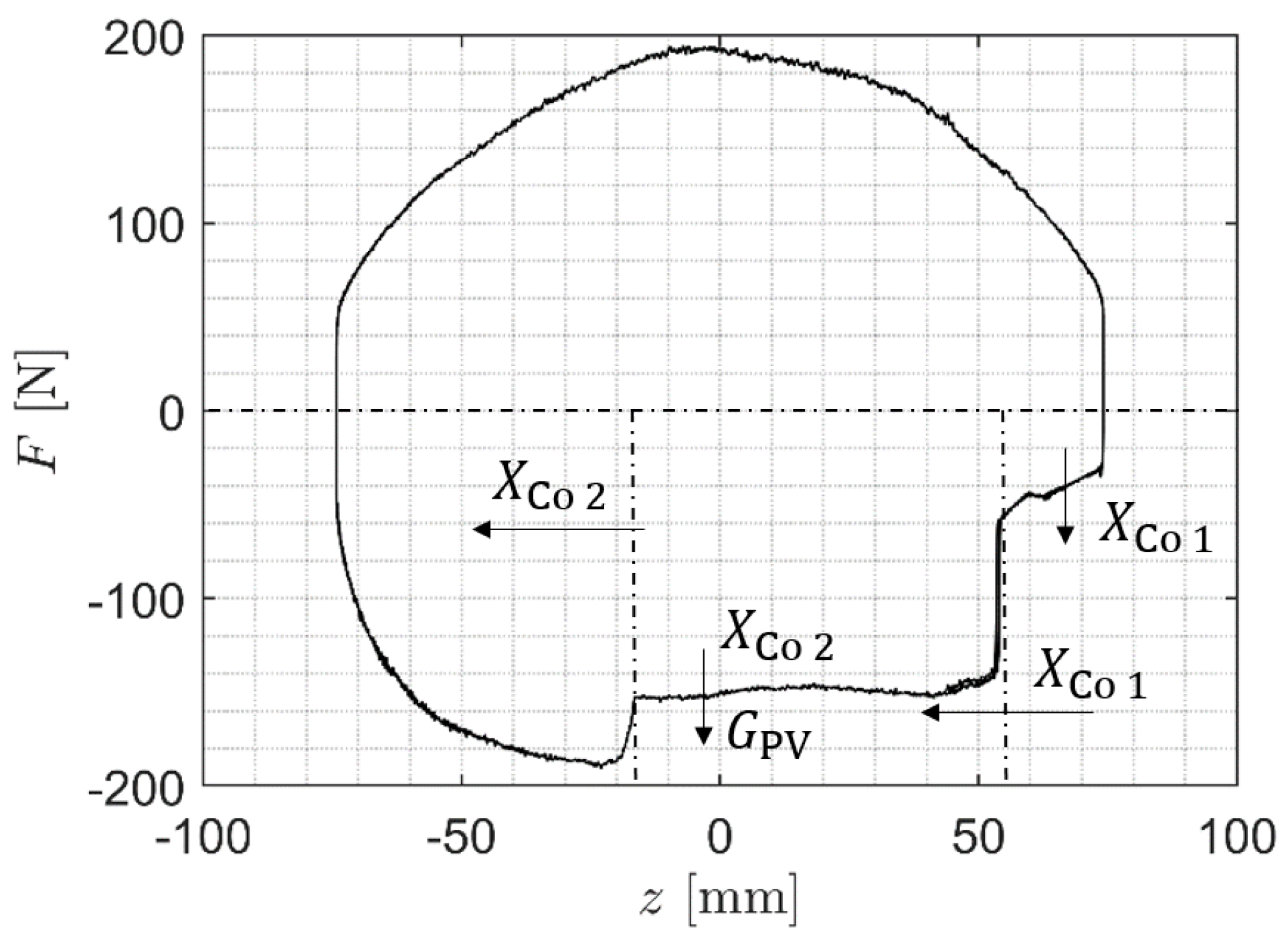

Figure 13 shows the twin-tube passenger car SA. The force between the connection points of the SA is caused by the pressure difference between the top and bottom of the piston valve (PV), the different sizes of the top and bottom of the PV and by friction forces between the piston rod (PR) and seal (OS) as well as between the PV and the inner tube wall of the SA (IT). Equation (

3) shows the calculation of the SA force calculated on the basis of the pressure and area difference in the PV.

The pressures on the top and bottom of the PV can be calculated from the flow of the oil and the gas pressure in the reserve chamber (RC). When the PR and the PV move, the SA oil flows through the PV and the bottom valve (BV) to equalize the pressure in the working chambers and . The oil flow through the valves causes fluid friction, which is largely responsible for the force of the twin-tube SA. This force is only generated when the oil flows through the valves. If gas flows through the valves, this force is not generated.

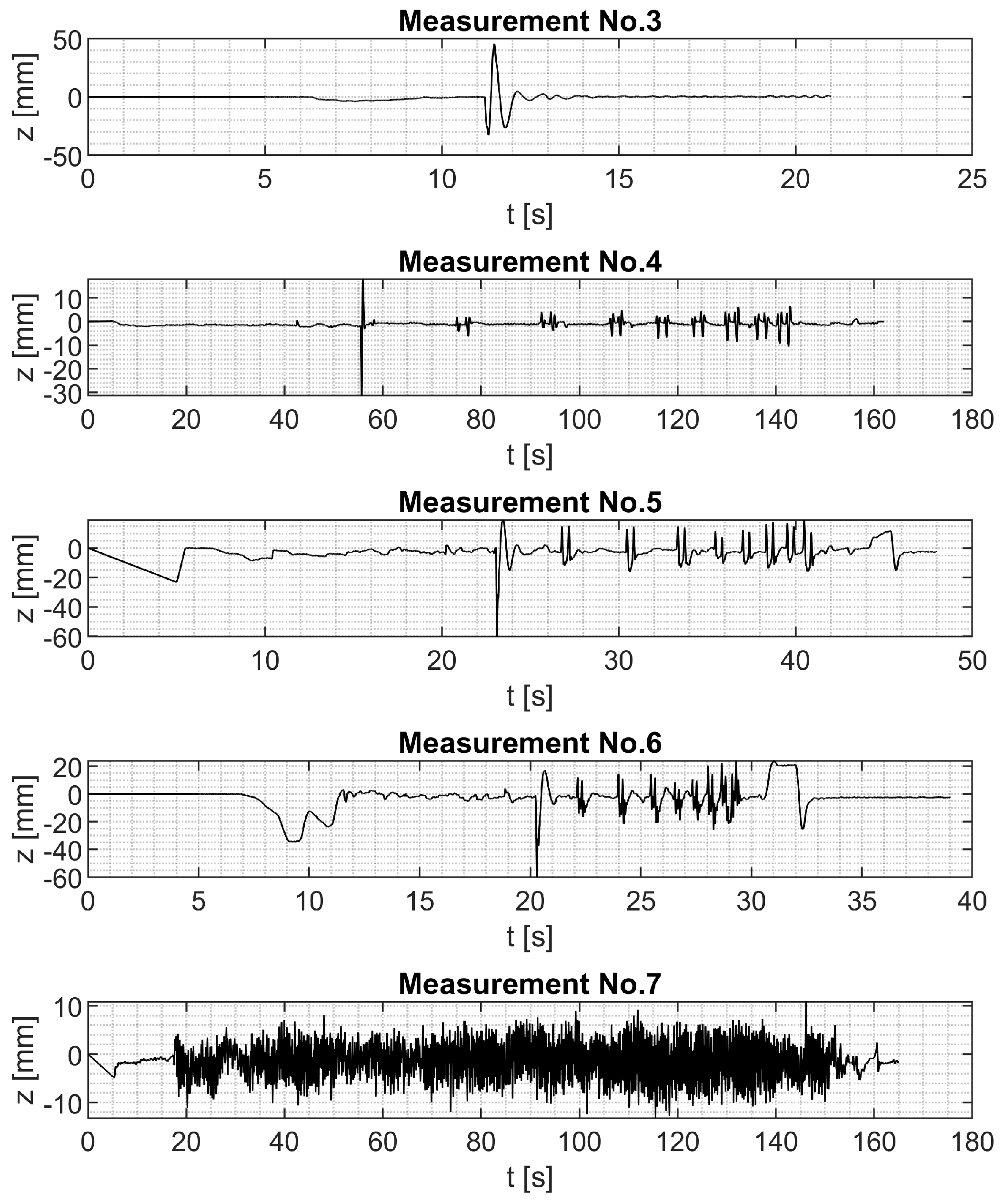

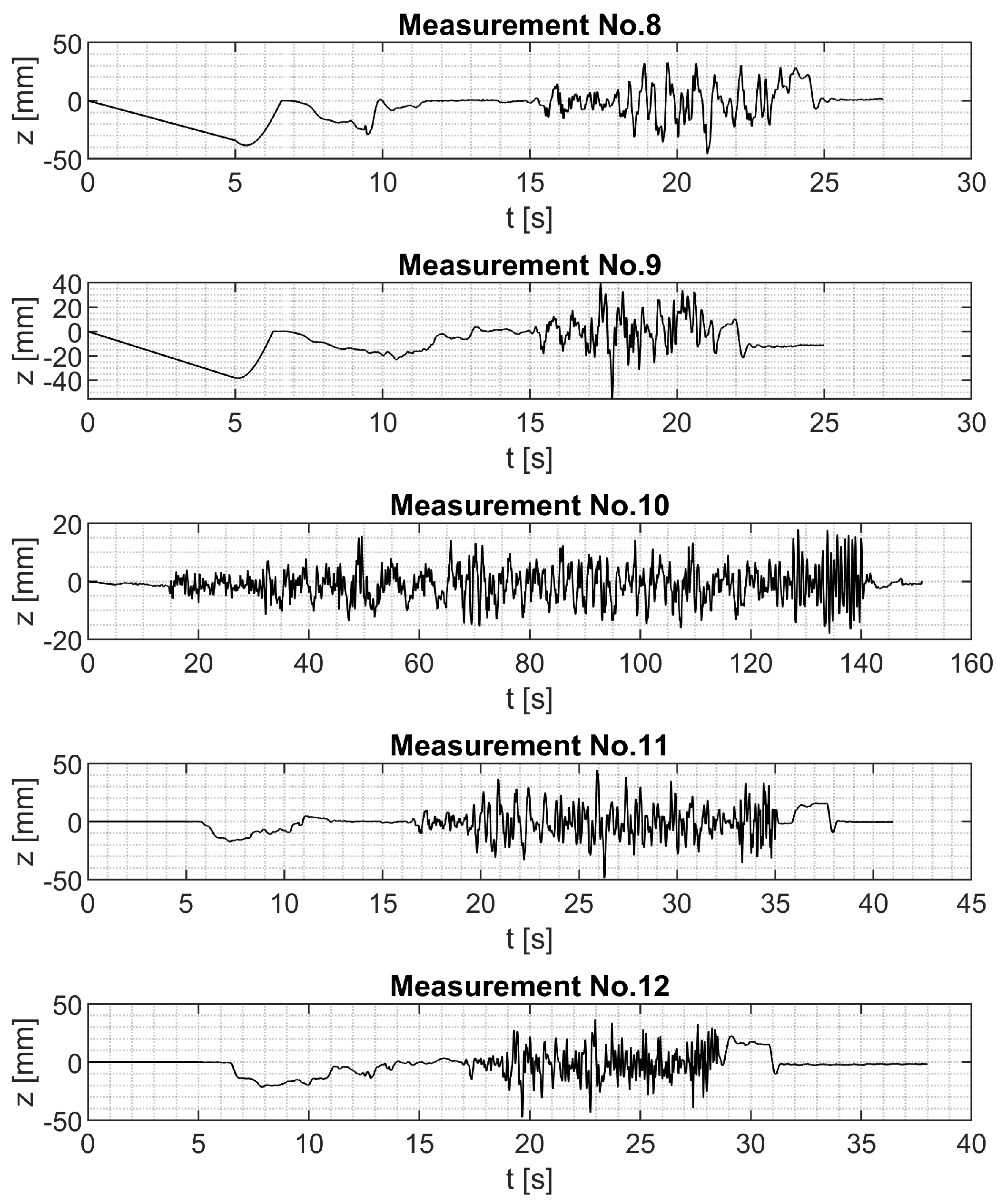

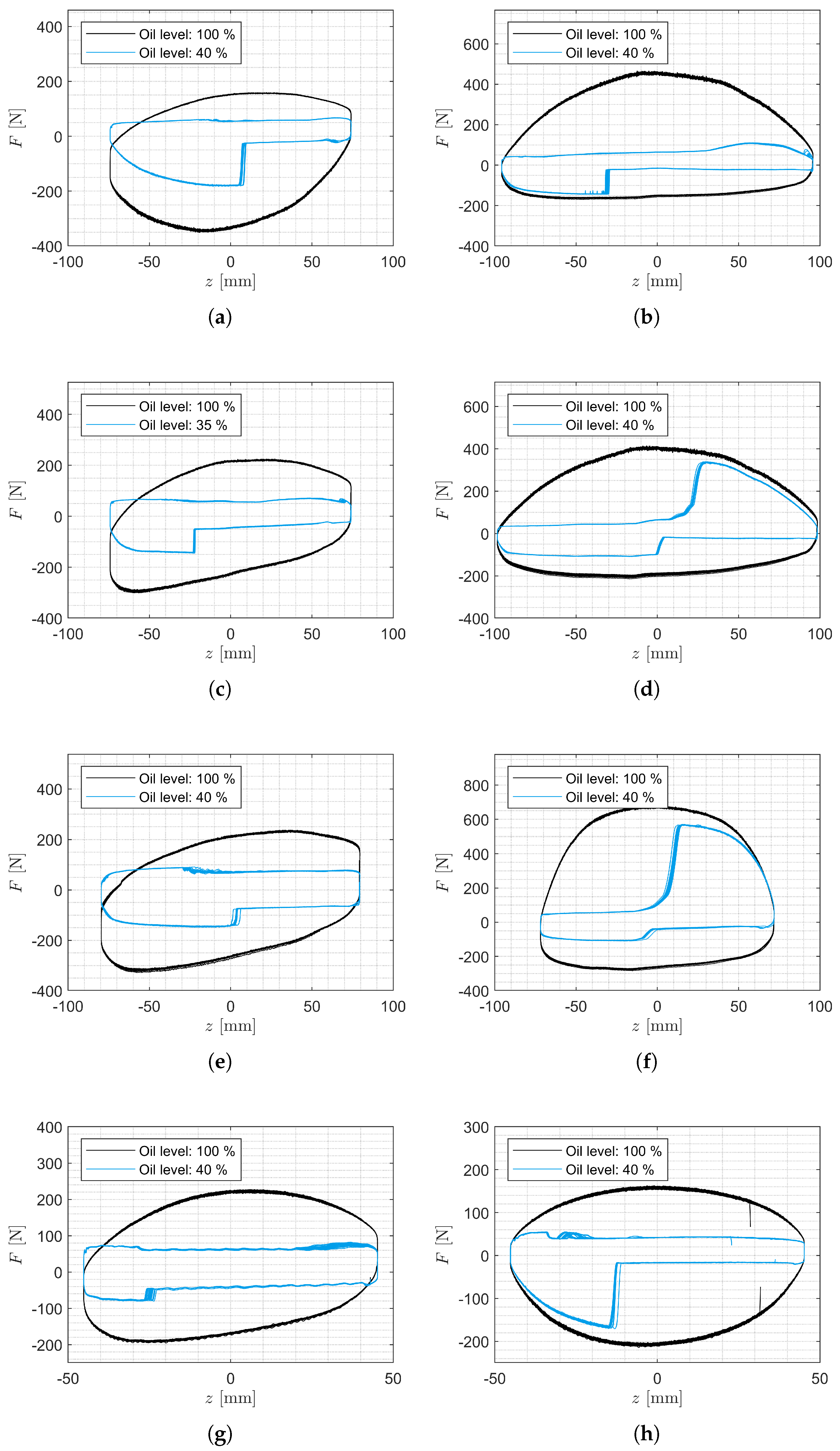

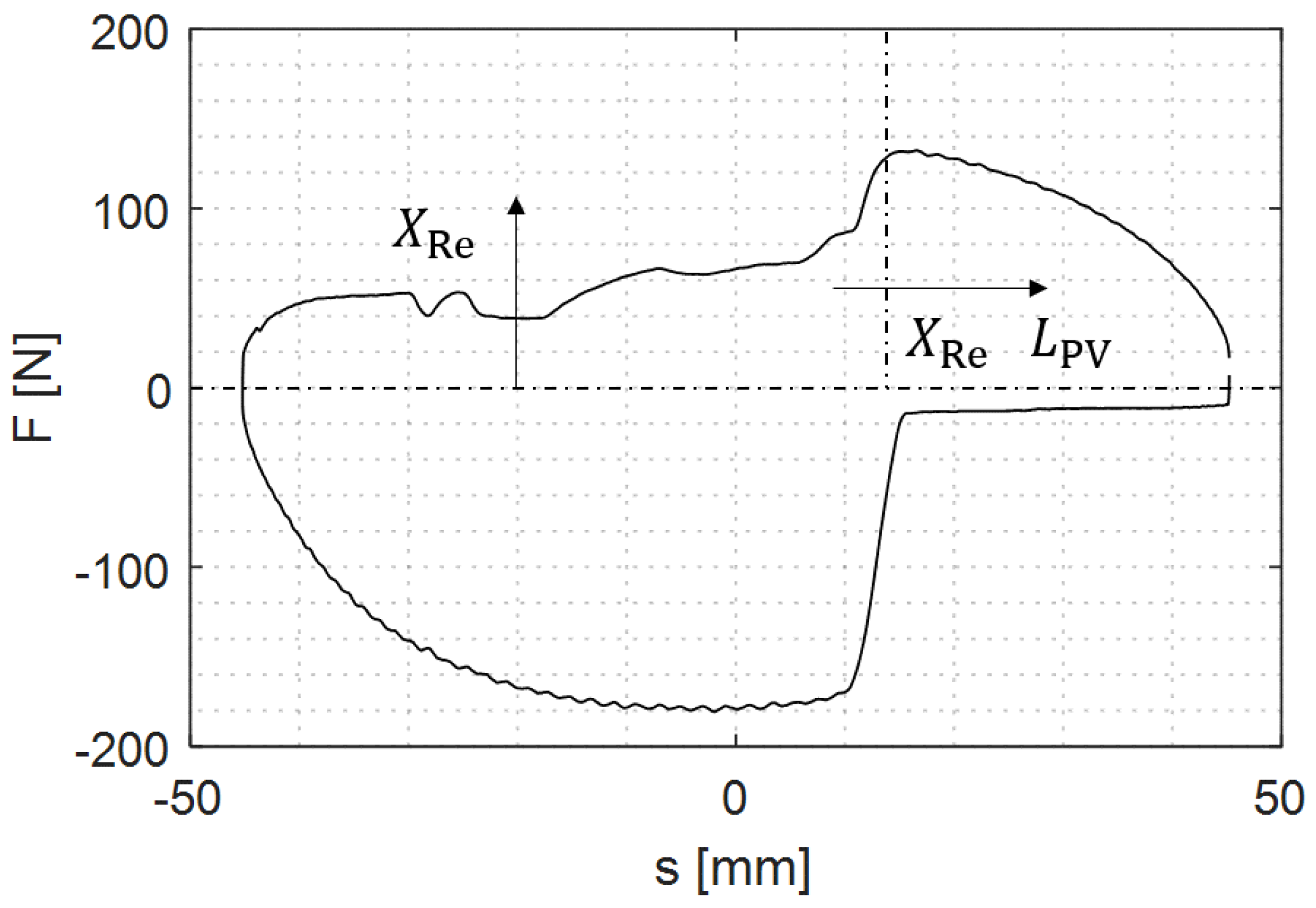

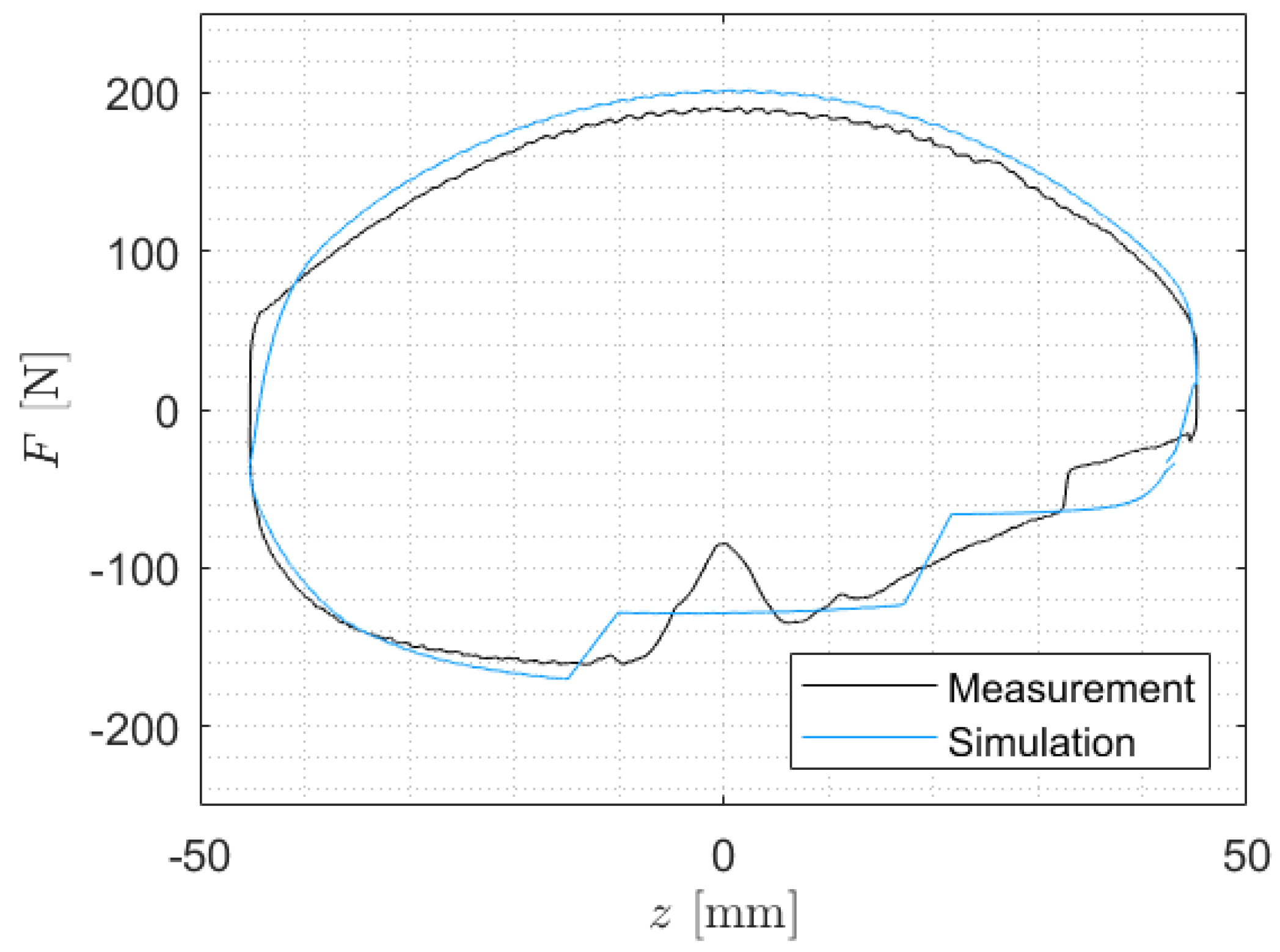

Figure 8 shows that the fluid force of the degraded SA depends on the deflection of the SA. The figure suggests that the respective increase in force during rebound and compression is caused by an oil flow through the SA valves, which did not take place before. It can be assumed that the PV is immersed in a volume of oil at this point. The figure also shows that the force of the intact condition is not reached after the increase in force. The force achieved after the force increase is different for each SA in relation to the force of the intact SA. Therefore, it is assumed that this difference is caused by the volume flow of oil through the two SA valves. To calculate these forces, the degradation model calculates the volumes of the individual working chambers and the volumes of the media in the working chambers at each time step in the numerical simulation.

The parameters

and

each describe the relative flow of oil volume through a SA valve in relation to the oil volume flow through a SA valve when the SA is intact (equations (

14) and (15)). If the parameters

and

are equal to one, the oil volume flow through the valves corresponds to the oil volume flow through the valves when the SA is intact (equations (17) and (19)). It is assumed that the oil performs the full potential work on the valves. If a volume flow of gas or foam is detected through the valves, the work performed on the valves is relatively reduced. If only gas flows through a valve, no work is performed and the parameters

and

become zero (formulae (

16) and (18)). In order to calculate the volume flows of the various media through the valves and to correctly reduce the potential damping force, case distinctions are made. It is assumed that in the rebound stage, the damping force is generated exclusively by the flow of oil through the PV, whereas in the compression stroke the damping force is generated by the flow of oil through the PV and BV [

33].

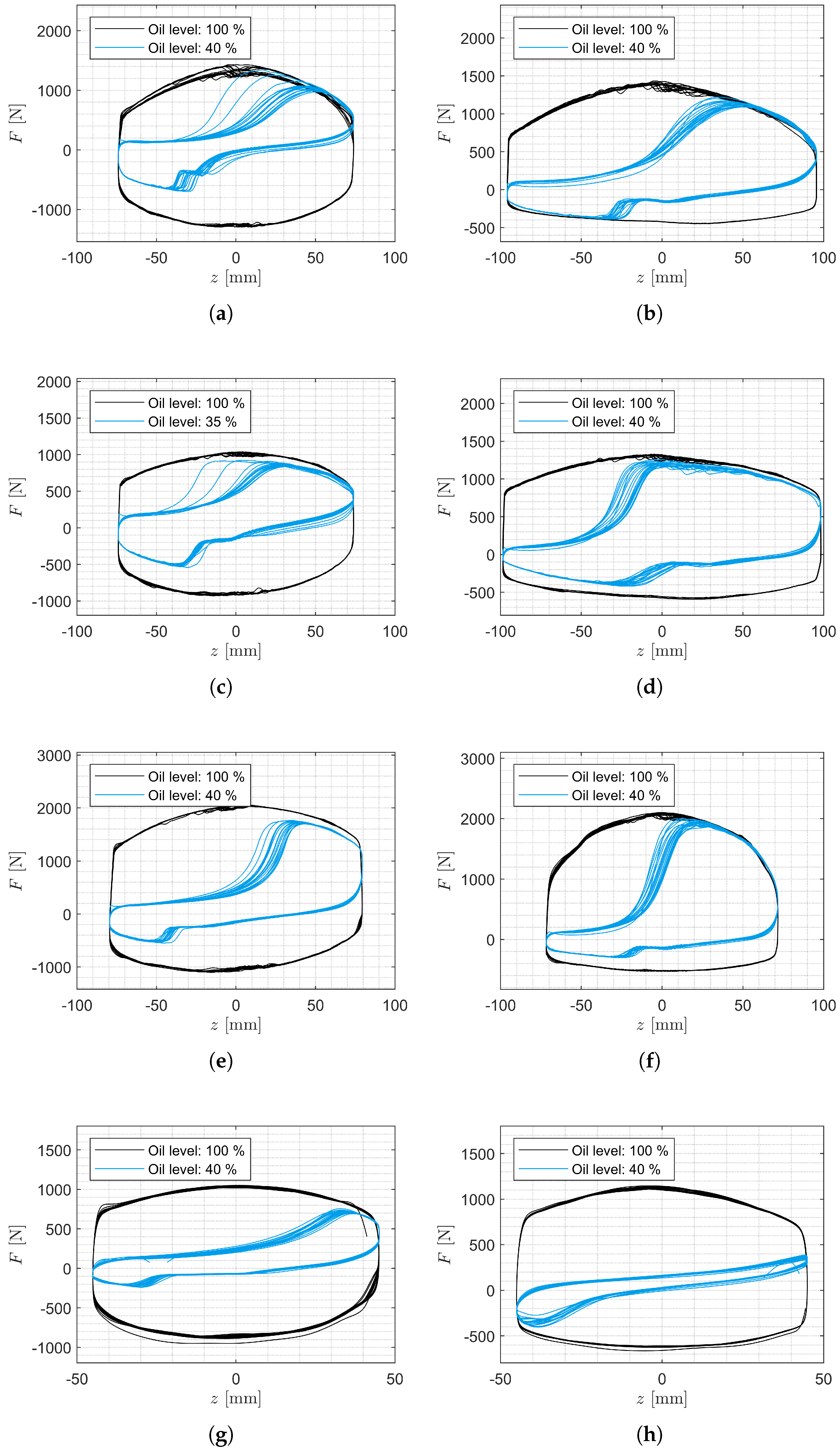

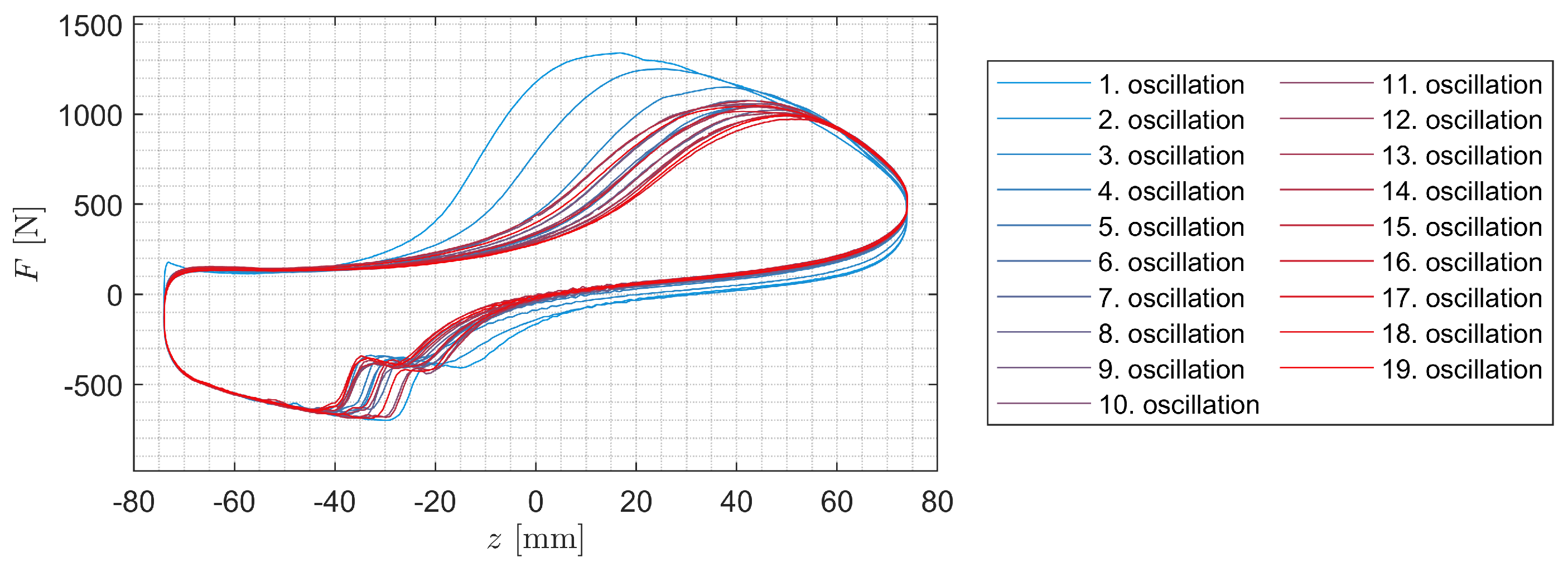

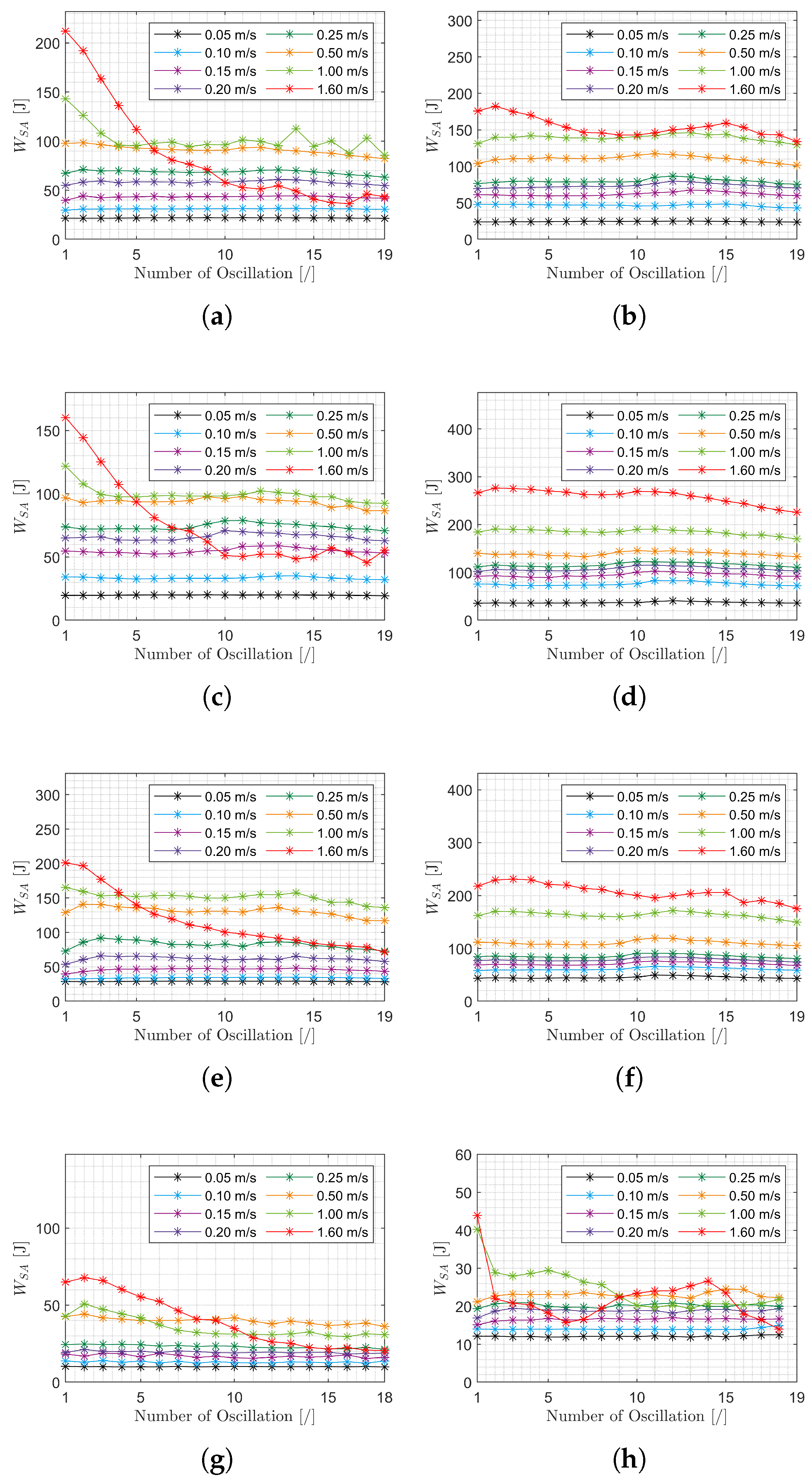

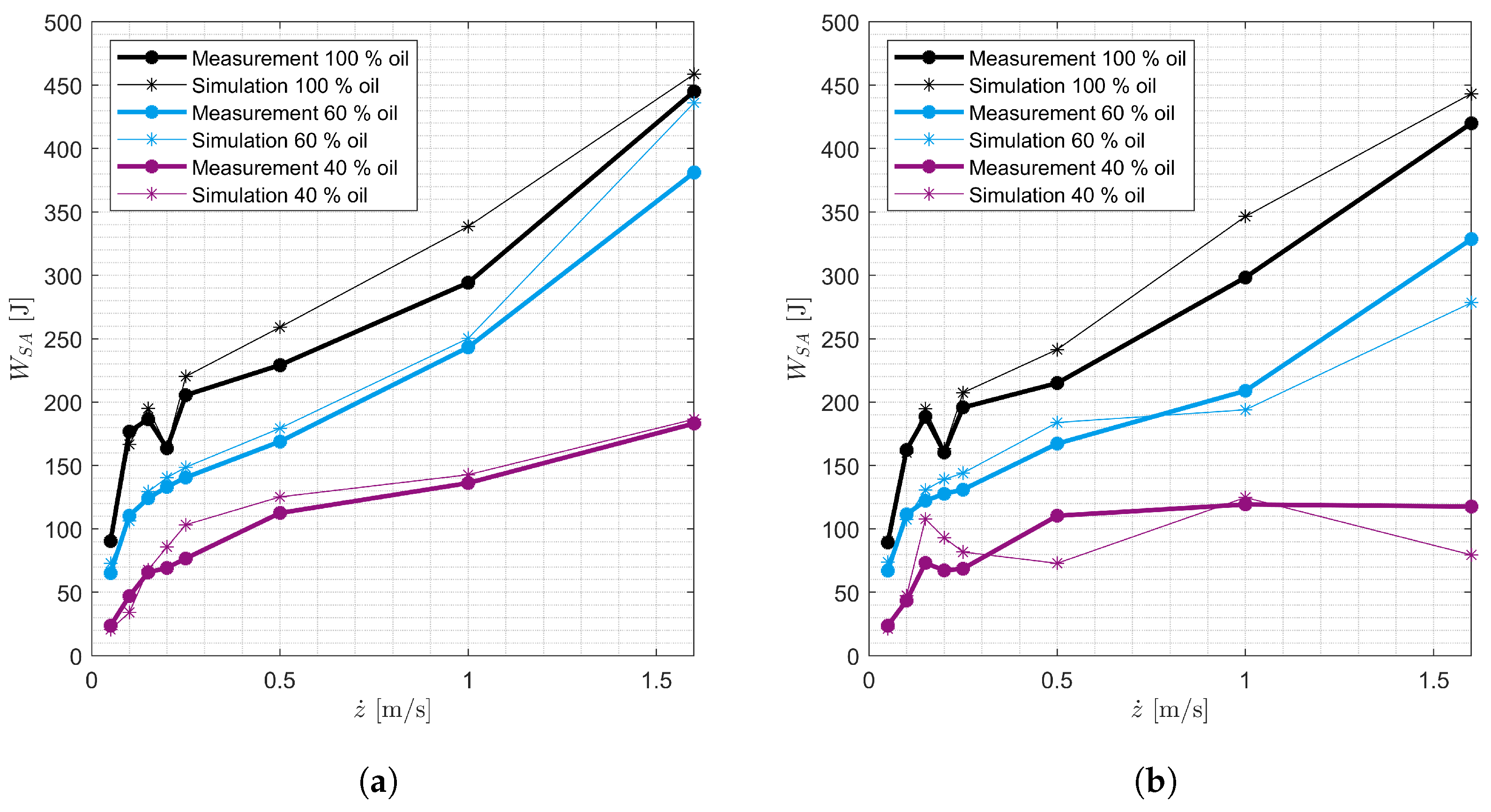

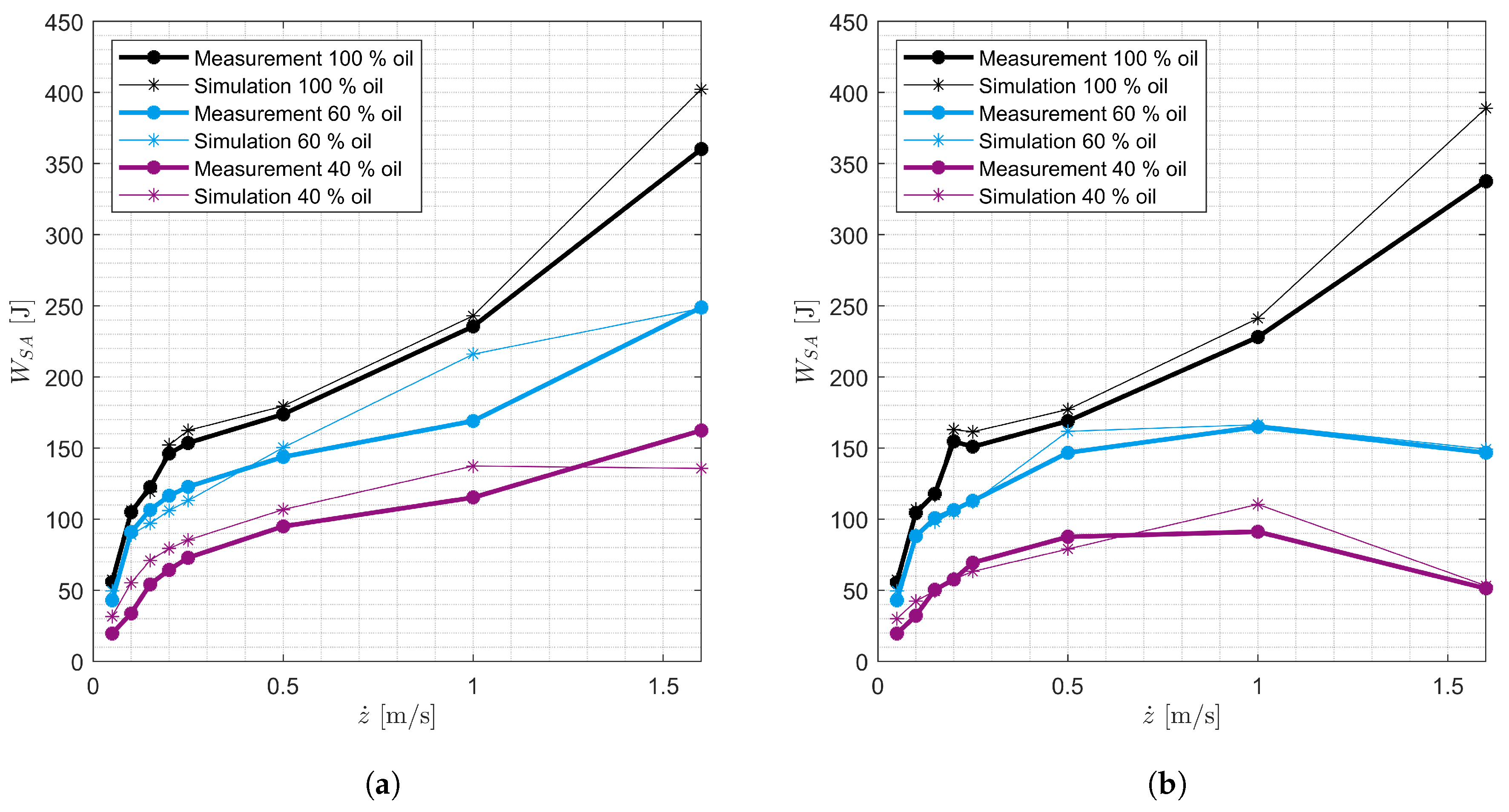

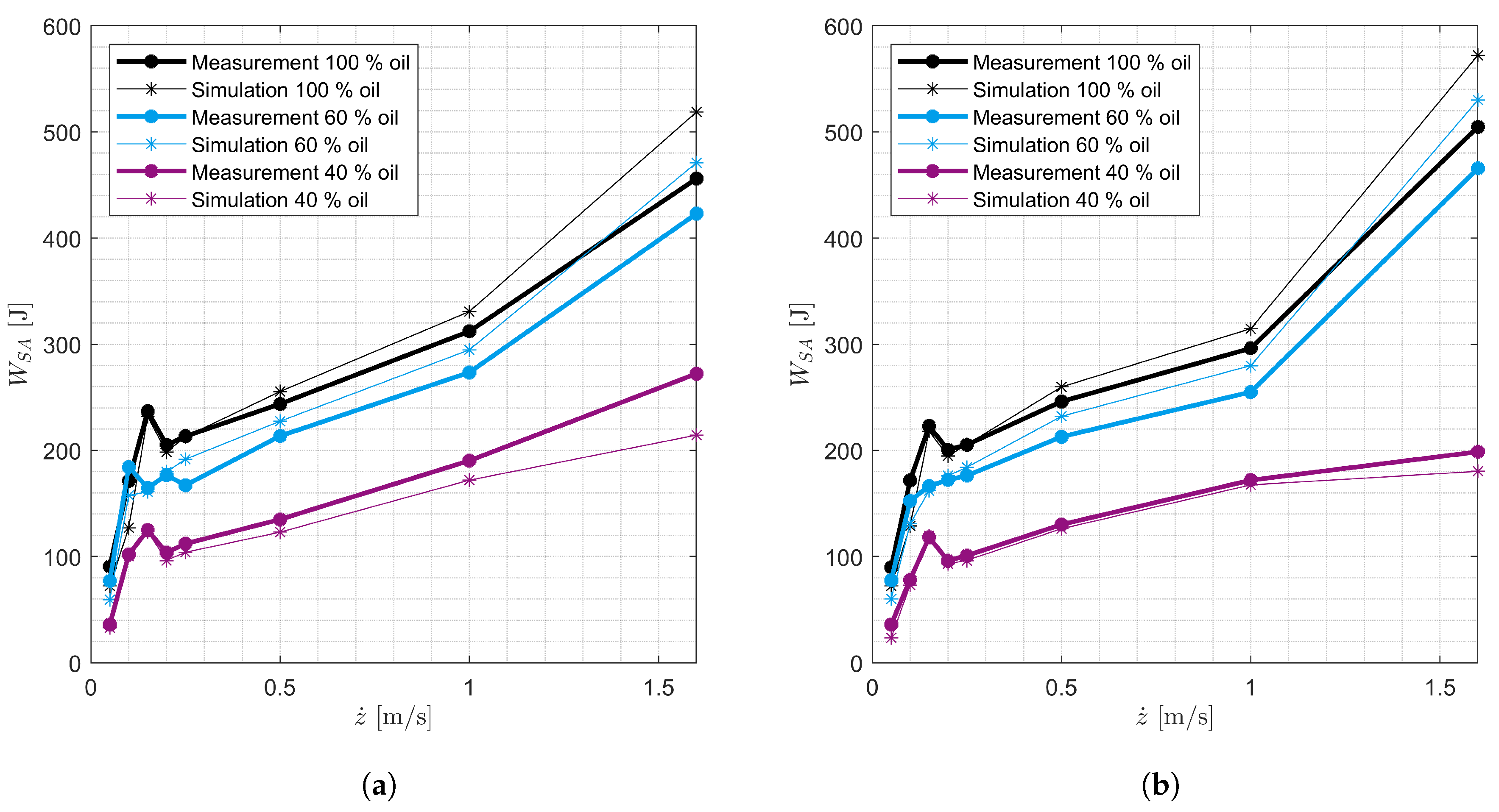

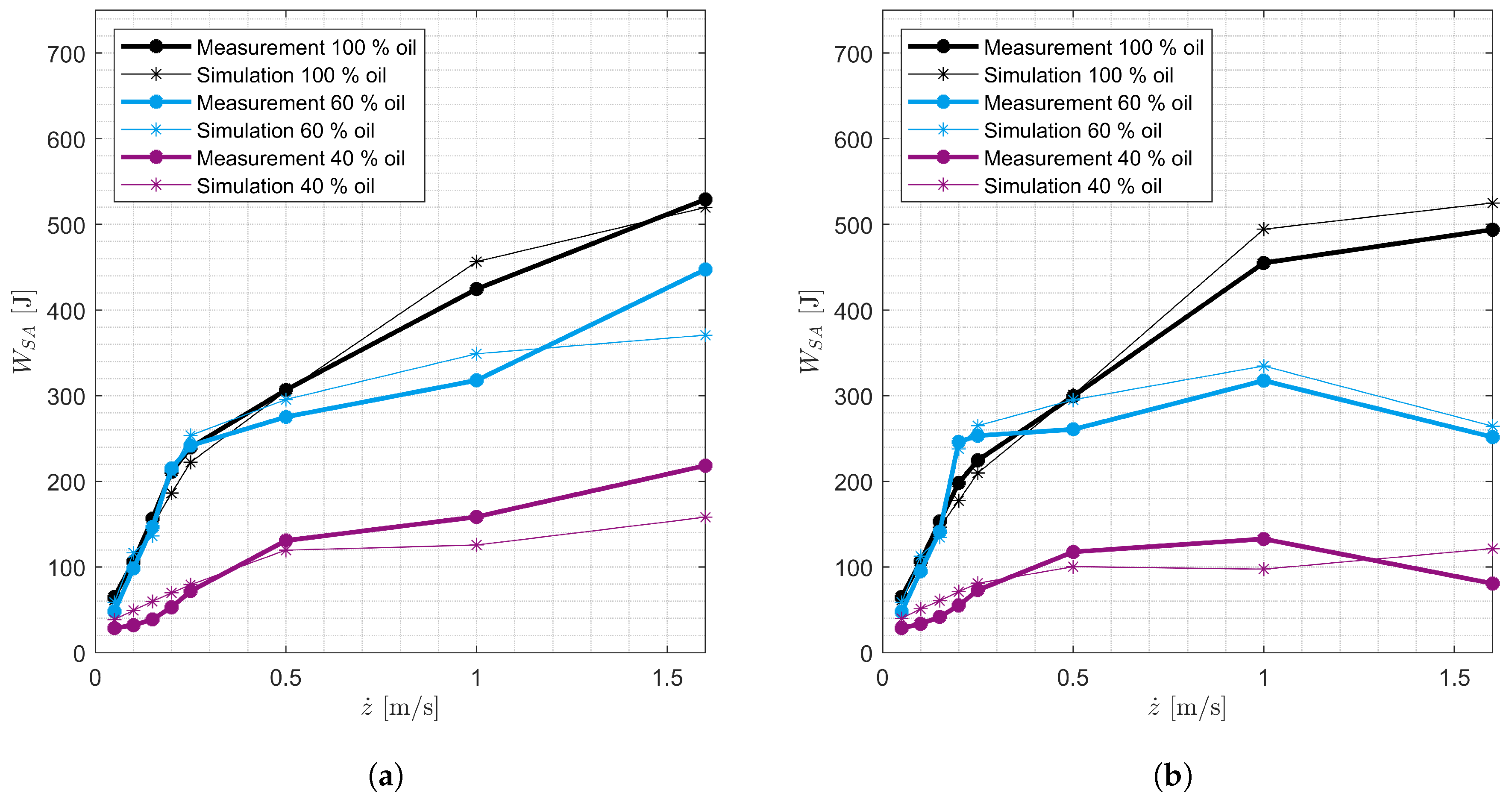

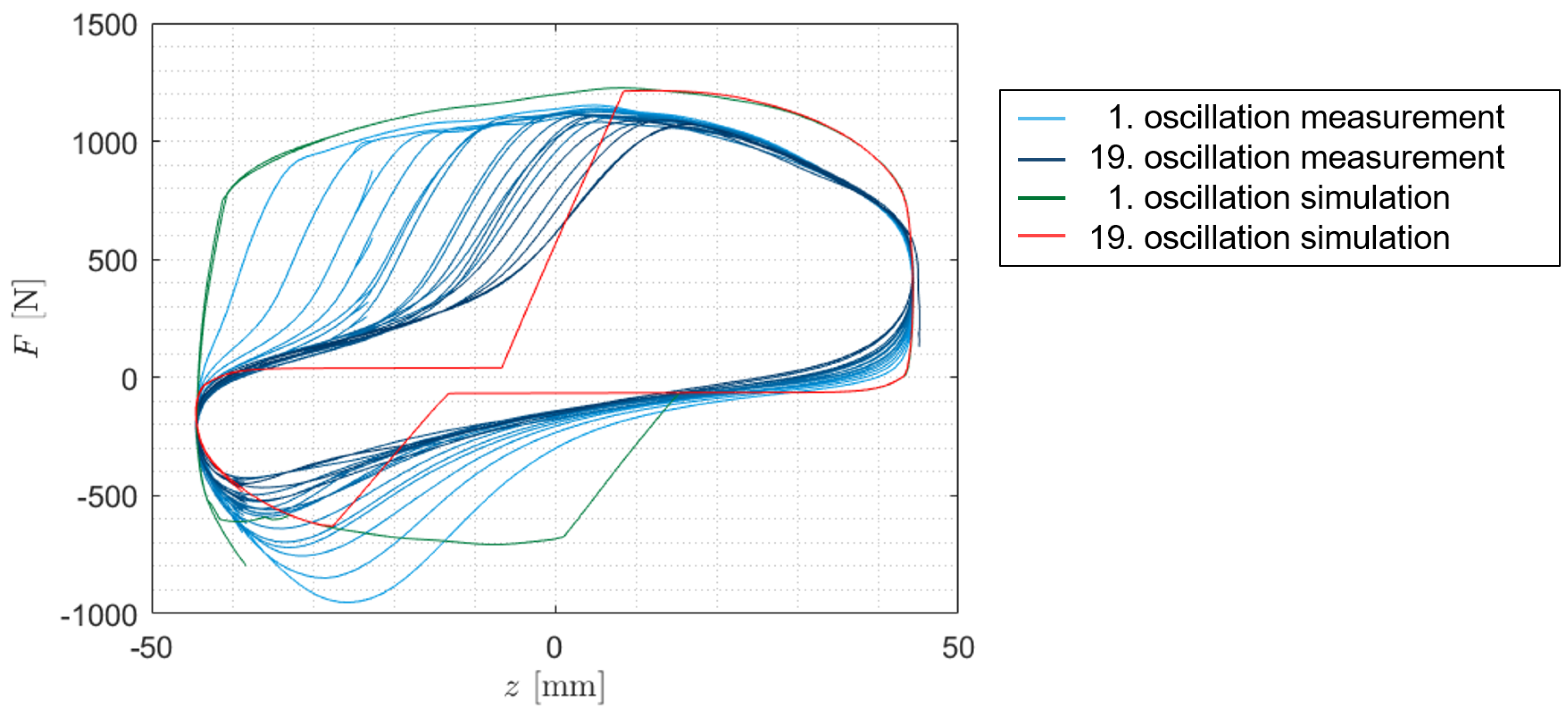

For higher SA velocities, it can be observed in

Figure 11 that the damping force decreases with increasing number of oscillations. It can be observed that the damping force in the rebound and compression stages builds up later during the 19th oscillation than during the first oscillation.

Gao and Czop present models that describe the reduction in SA force as a result of cavitation [

18,

19,

21]. These models calculate the dissolving of gas from the SA oil and the foaming of the SA oil with gas. The model presented here also calculates the oil, gas, and foam volume fraction in the individual working chambers at each timestep according to

Figure 13. For simplified later application in full-vehicle models, the model presented here calculates the volume fractions using a phenomenological approach. Starting from an initial state, the change in the volume of the rebound working chamber

(equation (6)) and the compression working chamber

(equation (7)) is calculated when the PR is displaced. Additional oil or oil foam volume loss through the upper SA seal is neglected (equation (13)). The volume change of the compression working chamber

(equation (9)) takes place through the PV (equation (11)) and the BV (equation (12)). Only the volume of oil and foam is taken into account in the reserve chamber. The volume change of oil and foam in the reserve chamber

only takes place through the BV (equation (10)).

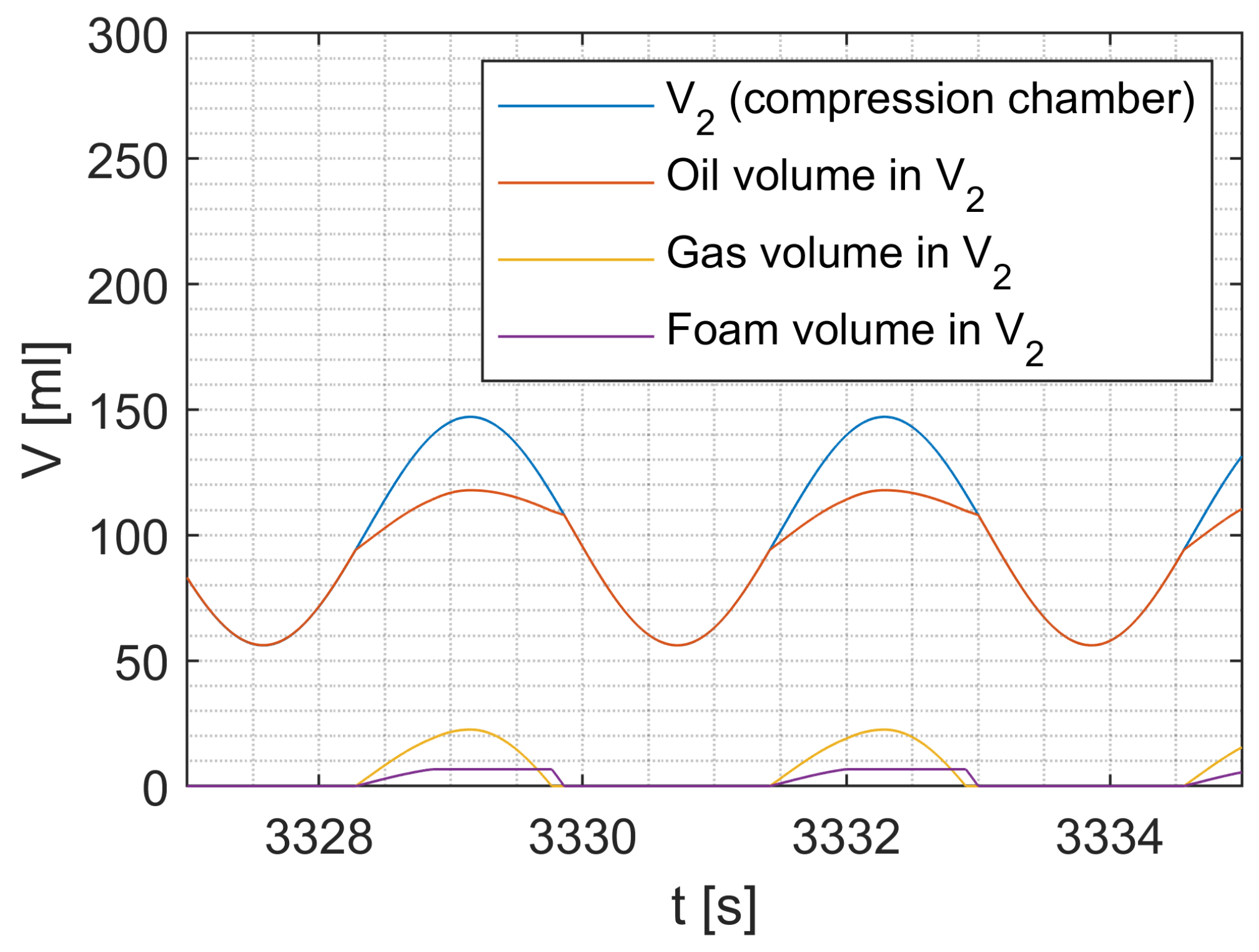

Figure 14 shows the volume of the compression chamber and the corresponding volume fractions of oil, gas and oil foam of SA 1 as an example for a harmonic excitation with an amplitude of 45 mm. It can be seen that the oil in the SA is not sufficient to completely fill the compression chamber to its maximum volume. When the working chamber is at maximum volume, it also contains a gas volume and an oil foam volume.

The initial state of the SA is defined before starting the simulation. For this purpose, the oil volumes in all three working chambers are defined and the displacement of the SA is adopted at the start of the measurement. During the simulation, a distinction is made between the SA states. A distinction is made as to whether the SA is in rebound or compression, whether the velocity of the SA is greater or less than 0.05 m/s and whether there is only oil, only gas, oil and gas, oil and foam or oil, gas and foam in the individual working chambers of the SA. The damping force component at both SA valves is calculated for the compression stage. Therefore, all working chambers are relevant. If the SA is in the rebound stroke, only the oil flow through the PV is taken into account.

If the velocity of the SA displacement is less than 0.05

, it is assumed that the oil does not foam and there is no cavitation. This threshold velocity was determined by Zwosta and could also be observed for all measurements presented here and is shown in

Figure 8 [

17]. Without foam in the working chambers, gas can flow through the valves first and then oil, or only oil if there is no gas volume in the working chamber. If only gas flows through the SA valves, the fluid force component is reduced to 0 N for the valve in question. If only oil flows through the valve, the full potential damping force is applied.

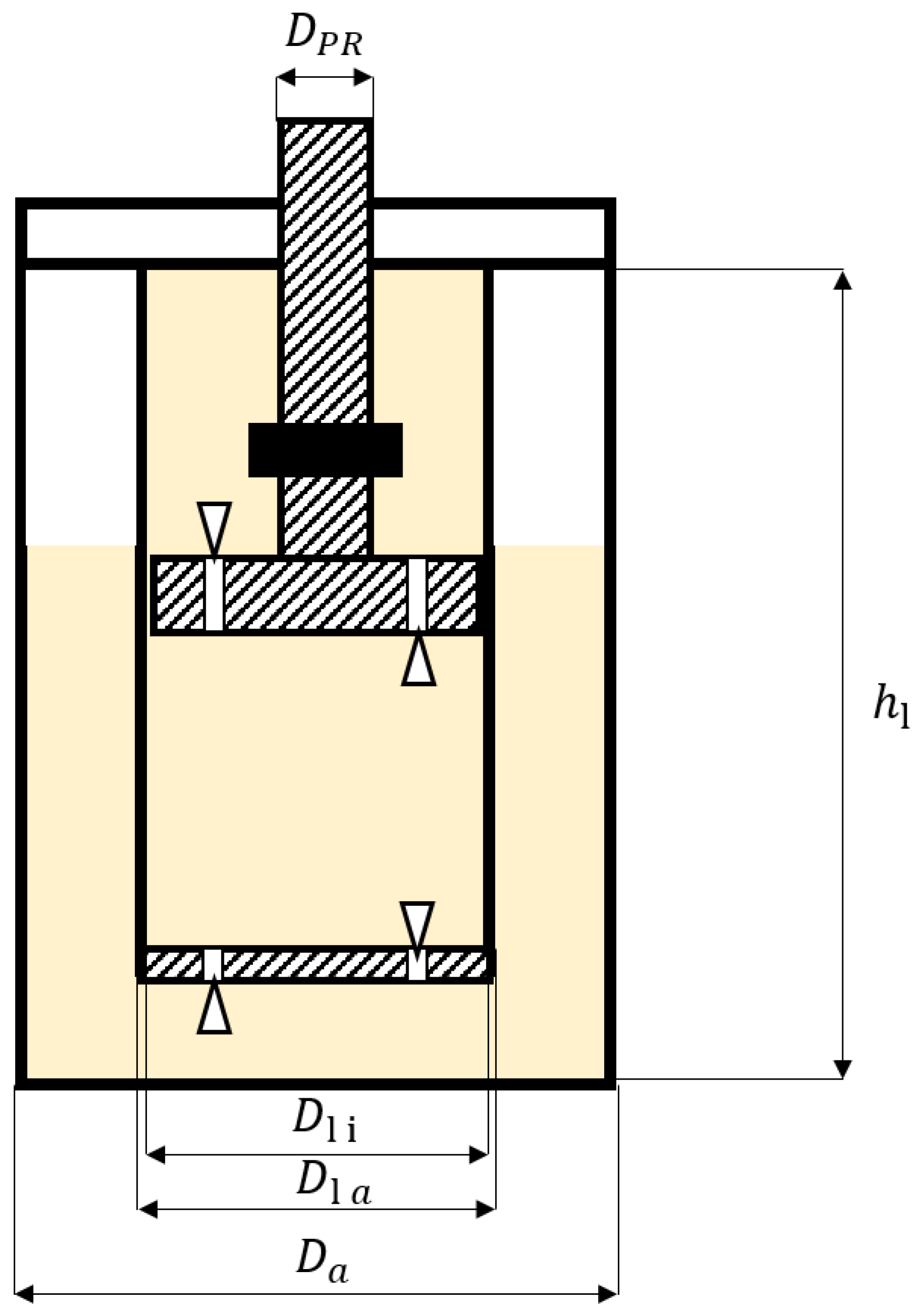

For simplified calculation of the volume flows through the SA valves, the volumes of all working chambers and the oil volume in the SA must be known. For the parameterization of the model, all SAs were disassembled.

Figure 15 and

Table 5 show the relevant dimensions of the SAs.

Hu found that oil and gas can also flow through the SA valves at the same time [

20]. This process can also be seen in

Figure 8. Therefore, the parameter

X is introduced, which describes for each SA valve the proportion of oil that flows through a valve simultaneously with a proportion of gas.

The leakage factor

is introduced, which defines the proportion of oil that flows from one working chamber to another but does not generate a damping force. The parameters

X and

can each range from 0 to 1.

Figure 16 shows the influence of both parameters on the calculation of the force in the rebound stroke in the F-s diagram. The change in the relative flow of oil volume through PV is calculated using the leakage factor

and the parameter

(equation (

22)). Equations (23) to (25) describe the calculation of the damping force in the rebound stroke for low velocities. The

Table 6 and

Table 7 list and explain all parameters of the degradation model.

During compression stroke, SA oil can flow through both the PV and the BV. The parameter

defines the proportion of oil flow through the PV in the total oil flow out of the compression chamber (

). This parameter also varies between 0 and 1. The complement part to 100 % of the oil flow flows through the BV (equation (

26)). If there is only gas in

, then only gas flows through the PV. Therefore, no fluid force is generated. If oil and gas are in

at the same time, oil flows through the BV into the reserve chamber and gas flows through the PV into the rebound chamber. The volume change in the compression chamber

is described by equation (

26). The parameter

defines the proportion of oil in the volume flow from

through the BV. If

is completely filled with oil and there is gas in the rebound chamber, the venting of the rebound chamber also results in a state with a proportional damping force. Oil flows from

to both the rebound chamber (

) and the reserve chamber (

). In this case, the proportion of volume flow through the BV in the volume change of

depends on parameter

, which can range from zero to one.

Due to the venting of the rebound working chamber, the oil volume flow through the PV can be larger than in the intact condition. Therefore, the parameter

is introduced. This parameter can also range from zero to one and describes the proportion of the damping force due to the increased oil volume flow through the PV. This results in the following calculation of the proportional damping force in relation to the potential damping force:

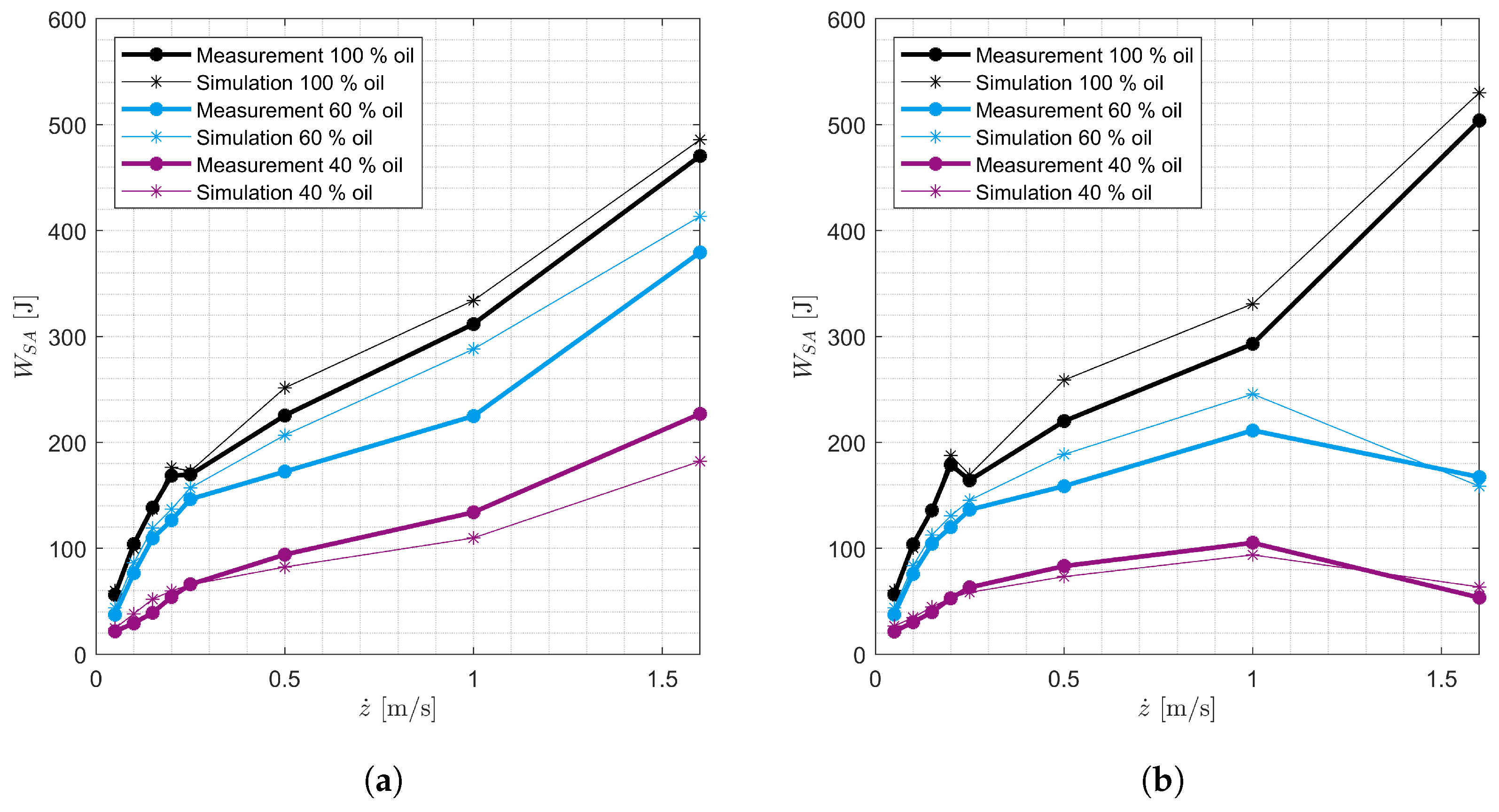

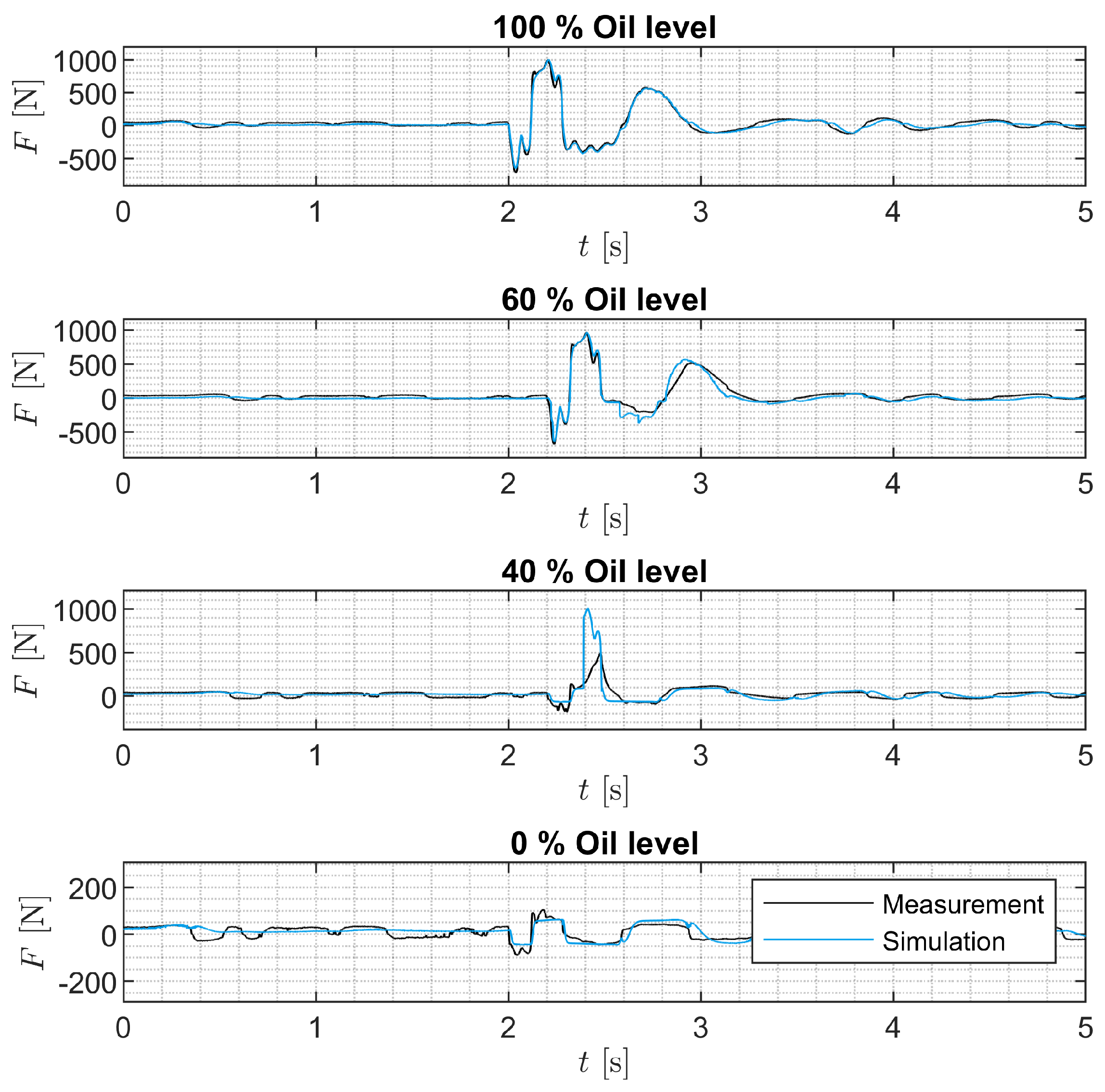

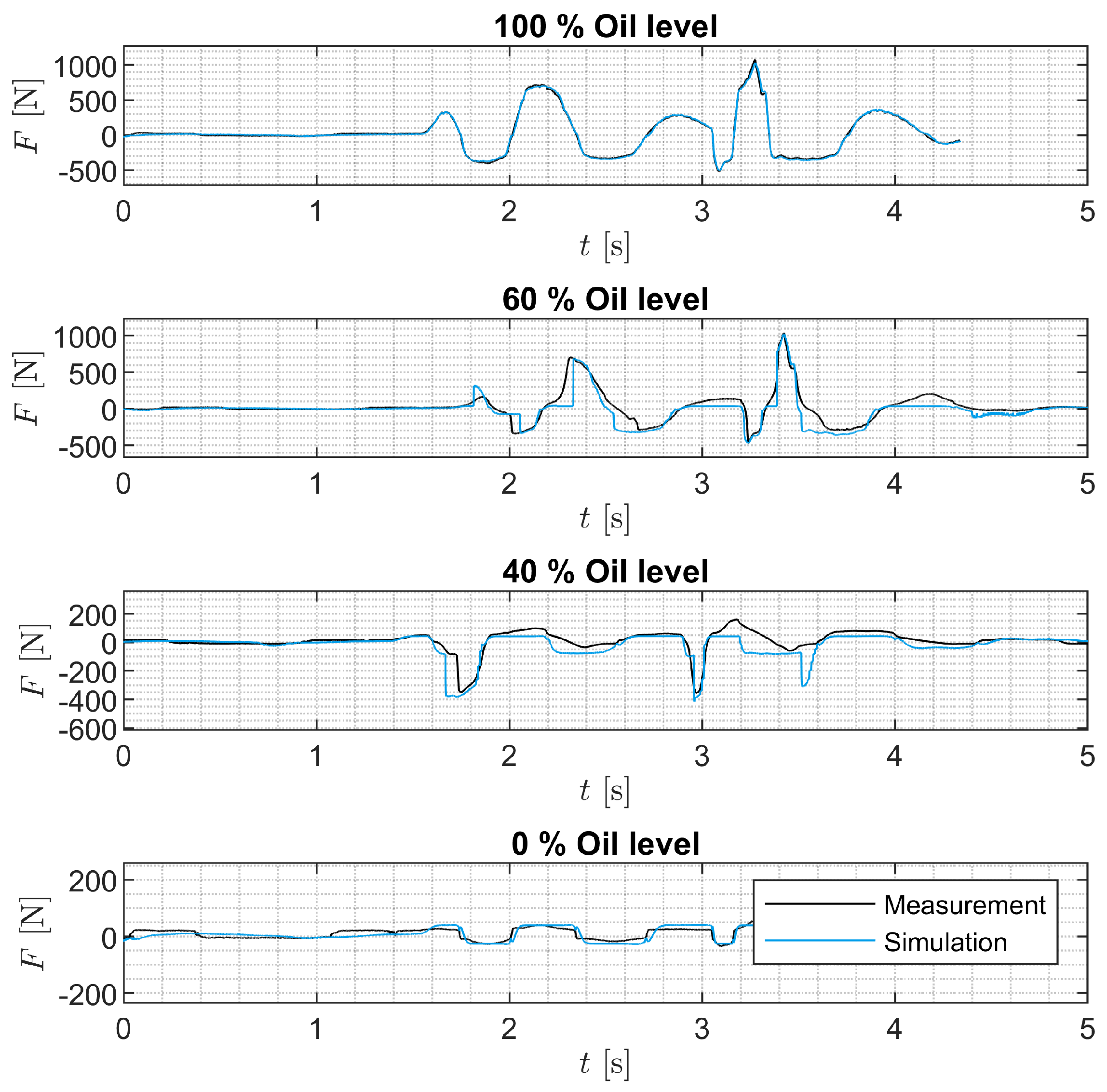

The measurement data show that the damping force decreases continuously over the number of oscillations when the SA is excited at high velocities and contains less than

oil. This behavior can also be seen in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11. This observation is explained by the foaming of the oil and cavitation in the degraded SA. Foam generation is assumed to be maximized when gas flows through oil. Other processes that could lead to foam generation, such as the flow of oil through a valve or the further foaming of existing foam, are neglected. In addition, the foam is generated without a time delay. When foam is generated, the foam volume corresponds to the sum of the proportions of air volume and oil volume. Overall, the sum of all volumes in the working chambers remains constant. The foam decomposition occurs only during rebound if the rebound working chamber is partially filled with foam and oil. The dissolution of foam during standstill is neglected due to the air separation capacity of the oil.

If gas flows through an oil volume at a SA velocity of more than 0.05 m/s, foam is generated in the working chamber, which initially contains oil. Foam generation is treated separately for BV and PV and is characterized by the respective parameters

S and

.

S and

can range from 0 to 1.

S specifies the proportion of the gas volume flow that is converted to foam.

specifies the oil proportion of the foam. A value of one means that the foam consists equally of gas and oil. If all conditions are met, it is checked whether there is enough oil (

) in the working chamber of the possible foam generation for complete foam generation in line with the parameters (equation (

30)).

The change in foam volume due to foam formation

results from the sum of the proportions that are converted from the gas volume flow and the existing oil volume (equation (

31)).

The oil proportion of the generated foam

is determined accordingly by the parameter

(equation (

34)).

If there is not enough oil, it is completely converted into foam. This means that only part of the actual foam volume can be generated. If further foam is formed in a working chamber in which foam is already present, or if additional foam flows in, mixing occurs. It is possible that the respective foams

and

have different oil proportions

and

. Consequently, the oil proportion of the total mixed foam

must be recalculated with the individual volume proportions as weighting in equation (

35).

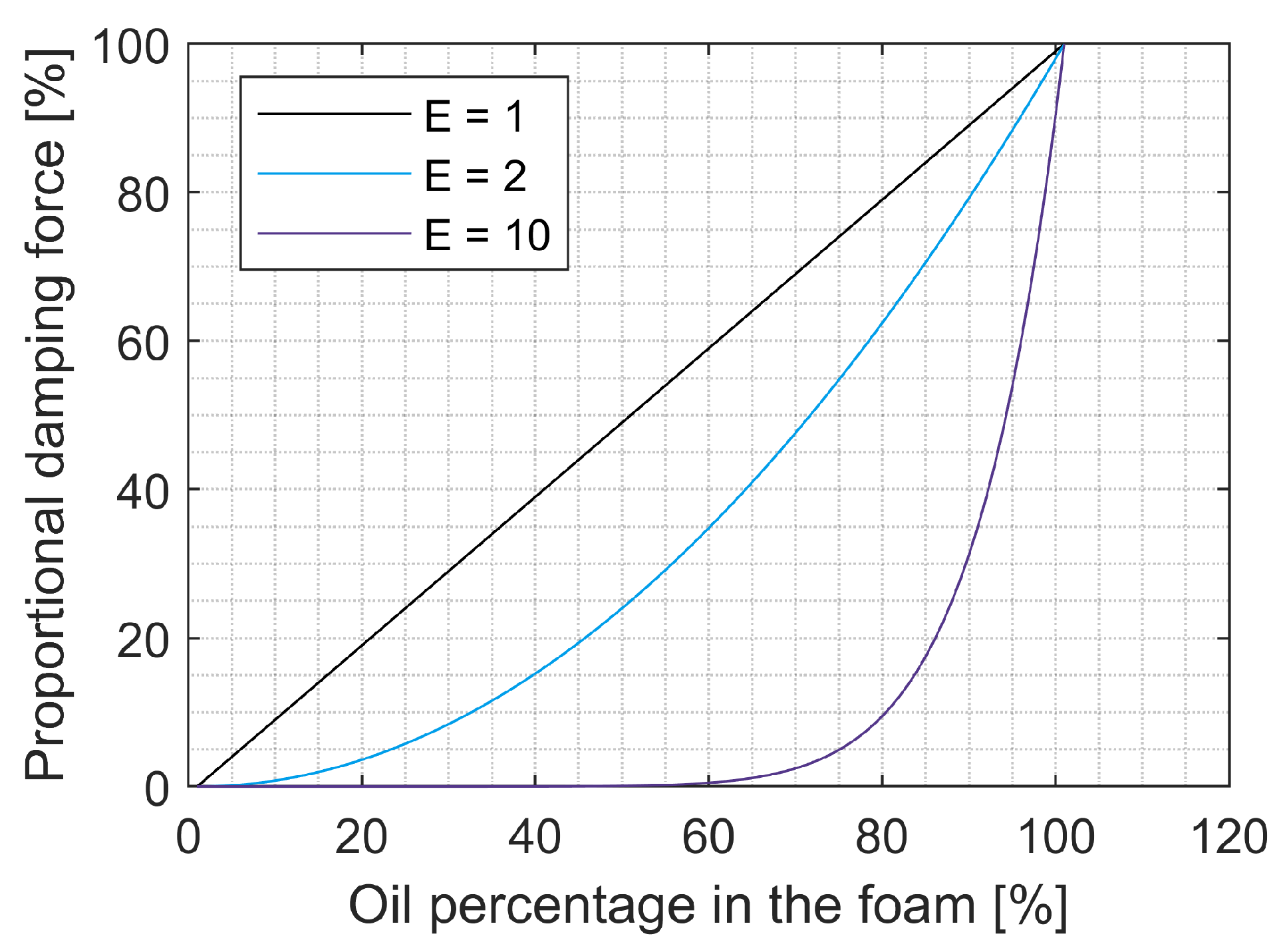

Foam can decompose during rebound. To characterize the proportional damping force at certain foam volume flows through the valves, an exponential approach is used with the parameter

B as a factor, which ranges from zero to one, and the parameter

E as an exponent (equation (

36)).

The factor

B indicates whether the foam generally behaves more like a gas, with a value of zero, or like oil, with a value of one. Exponent E describes the relationship between the proportion of oil in the foam and the proportionate damping force. A value of one results in a linear relationship and as the exponent increases, the proportional damping force for a certain proportion of oil decreases due to a non-linear, progressive relationship (

Figure 18).

The resulting damping force therefore results from the foam properties in combination with the described calculation of the volume flows of oil, gas, and foam through the SA valves. An increase in the parameter

S leads to increased foaming and therefore to a decrease in the volume of pure gas. A reduction in the parameter

leads to a reduction in the proportionate damping force of the foam. This effect is intensified by reducing the parameter

B and increasing the parameter

E. Equations (

37) to (39) show the calculation of the degradation coefficient

for high stroke velocities during the rebound stroke.

The foaming of the oil is not sufficient to explain the significant decrease in damping force and therefore the work performed by the SA at high excitation velocities (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11). Like other mineral oils, the oil in vehicle SAs dissolves gas [

34]. In steam cavitation, gas is released in the oil when the local pressure falls below the saturated vapor pressure. Mineral oil dissolves a maximum of 9.3 % - 11.3 % of its own volume as gas at normal ambient pressure and temperature. If the local pressure of the oil falls below the saturated vapor pressure, it takes between 3.6 and 7.6 s for half of this gas volume to be released. If the pressure does not fall below this value, it takes 6.1 to 10.2 s until half of the gas is dissolved.

At high excitation velocities, a significant pressure decrease can occur in the SA valves, resulting in the release of gas due to cavitation [

35]. Therefore, it is assumed that the sharp decrease in SA work in

Figure 10 and

Figure 11 at high excitation velocities is a result of cavitation. To model this effect, it is assumed that the oil flowing through a valve is converted into gas above a SA-specific threshold velocity

. Equations (

40) and (41) illustrate this relationship. It is assumed that cavitation occurs only in the PV. A cavitation parameter

is introduced for each of the compression and rebound directions.

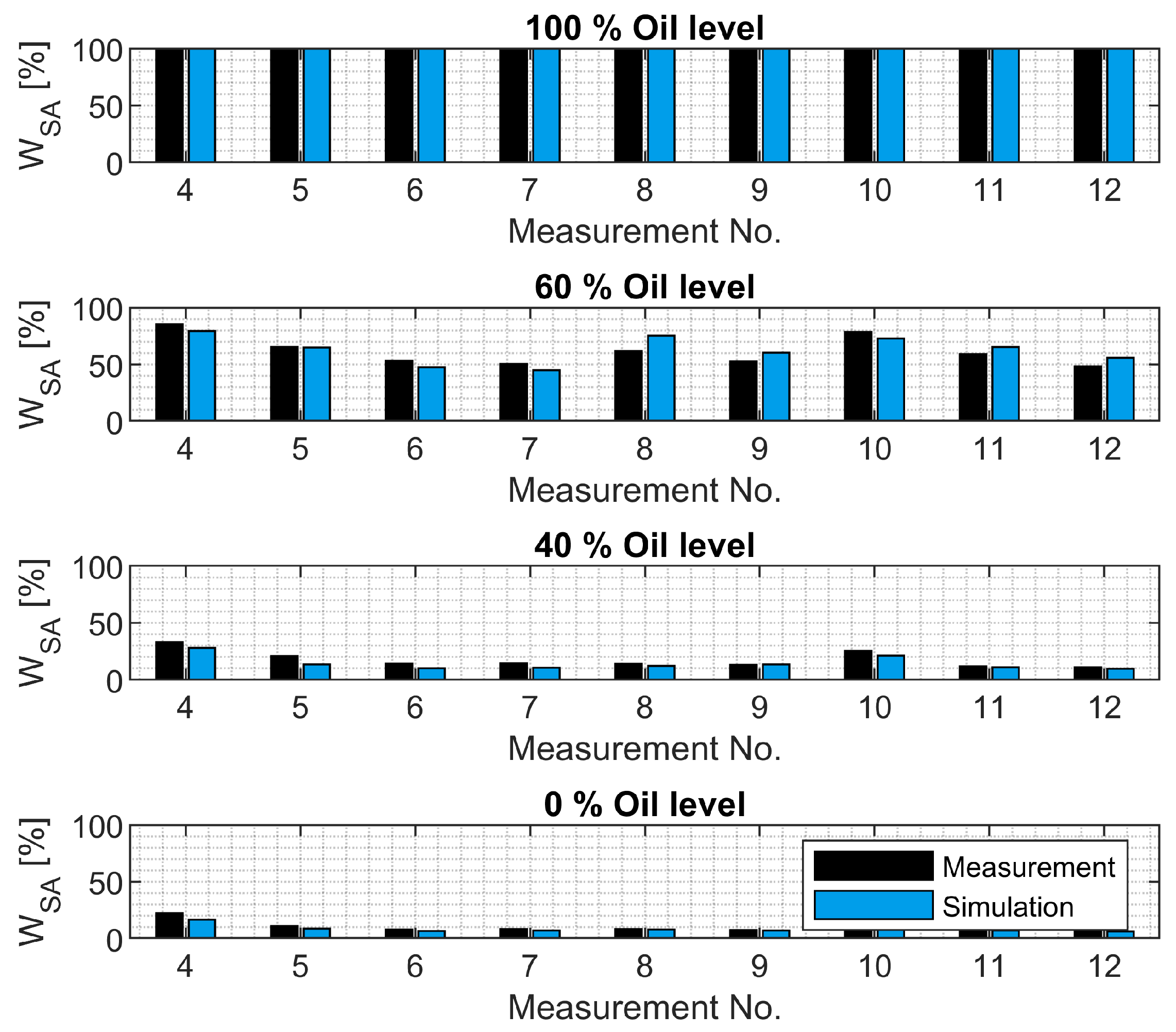

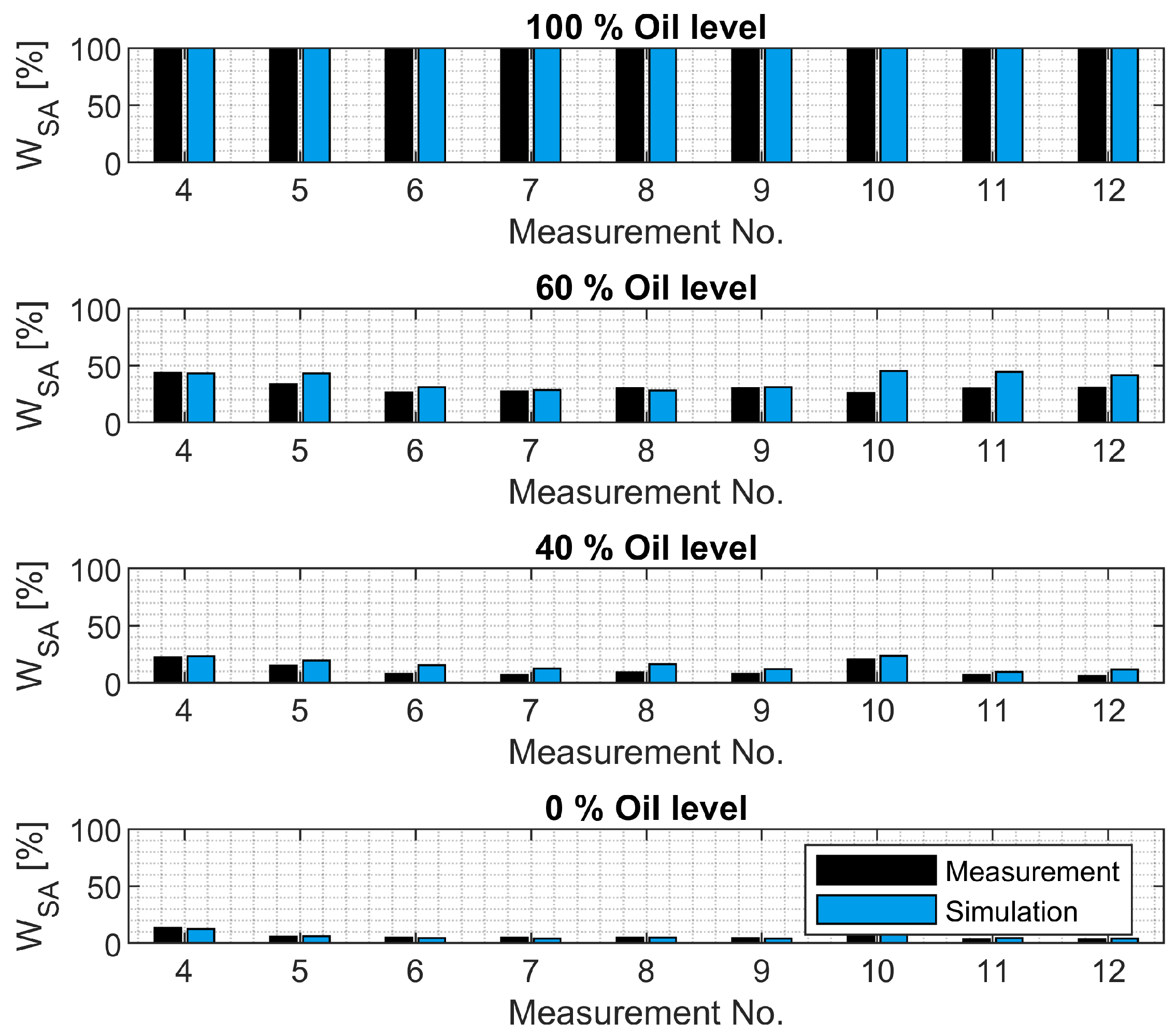

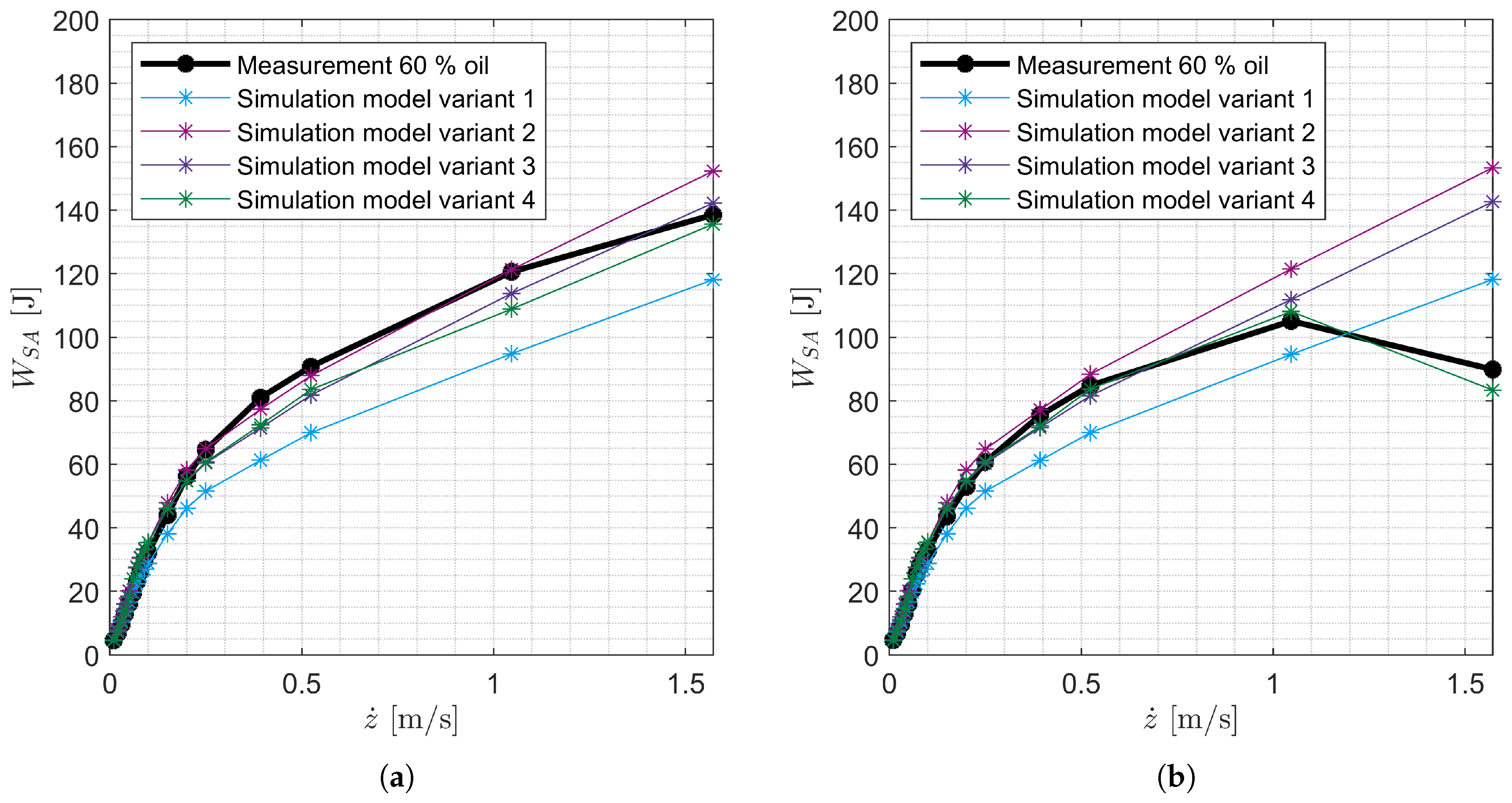

The parameters in

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8 are SA-specific. They are optimized on the harmonic measurements of the SAs with the oil levels 40 % and 60 % by means of particle swarm optimization. It is assumed that these 14 parameters are the same for all oil levels of a SA. The parameters are optimized in two steps. In the first step, the five parameters for the basic model (

Table 6) are optimized with the harmonic measurements up to and including a maximum SA velocity of 0.5

. In the second step, the six parameters of the foaming model (

Table 7) and the three parameters of the cavitation model (

Table 8) are optimized using the harmonic measurements with a maximum SA velocity of 1.6

. The sum of the Root-Mean-Square-Errors (RMSE) of the damping forces and the damping work performed from measurement and simulation is used as the optimization function. The formula (

42) represents the calculation of the optimization function with the data points

i and the length of the signal

n.