1. Introduction

The standard model of cosmology, rooted in the Big Bang paradigm and the theory of General Relativity (GR) with the addition of cosmological constant () and cold dark matter (CDM), has been remarkably successful in explaining key observations, such as the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), the large-scale structure of the Universe, and the accelerating cosmic expansion attributed to dark energy. However, several fundamental questions remain unresolved, such as the nature of the initial singularity, the flatness and horizon problems (or the origin of inflation), and the physical origin of dark energy. These challenges have spurred the development of alternative frameworks that seek to extend or complement the standard cosmological model. The nature of CDM and the origin of the smallness of the have been the central issues of modern cosmology.

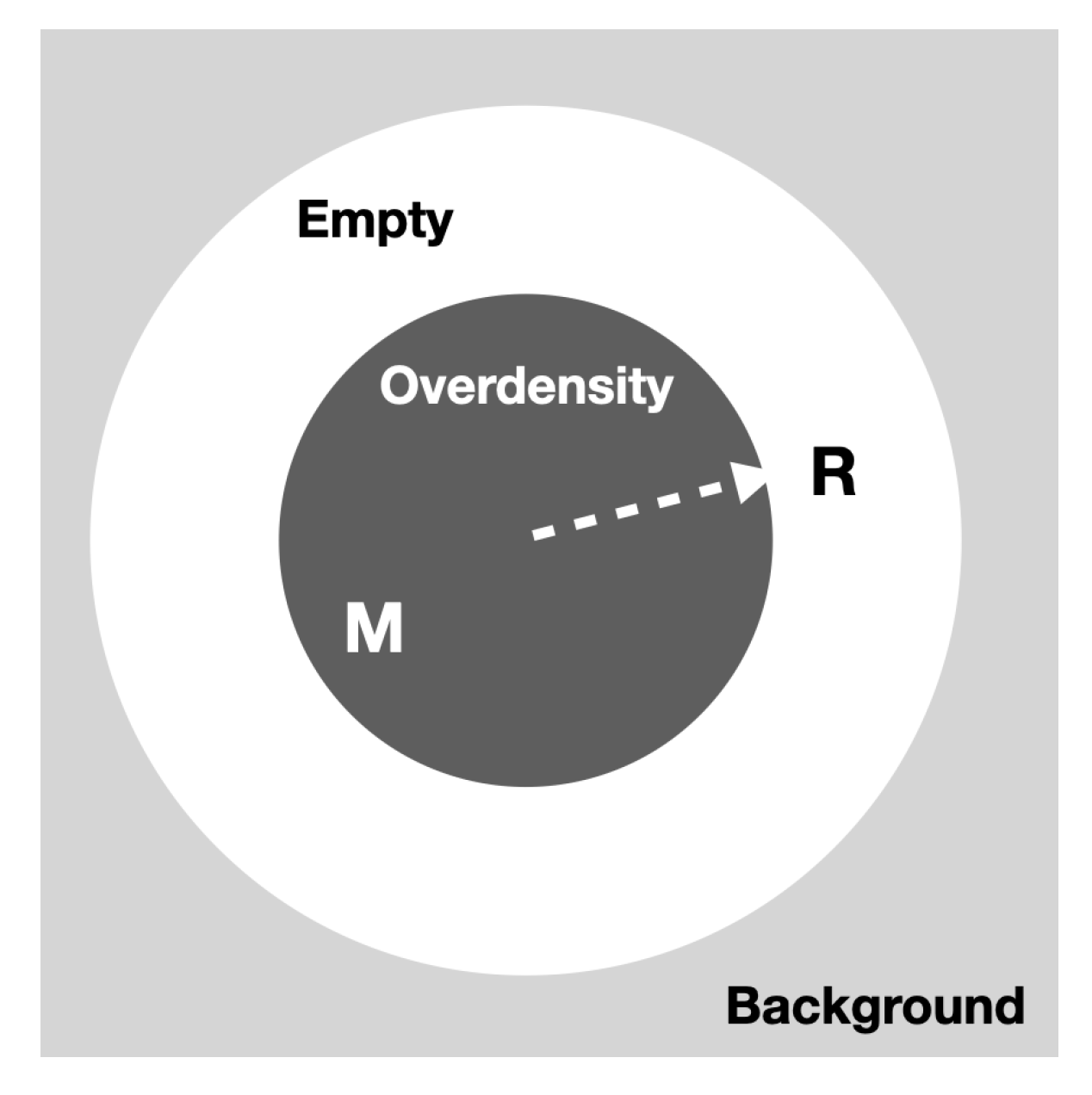

A related problem is that of understanding the singular collapse into a Black Hole. Both problems can be addressed when we consider the relativistic spherical collapse of a local (finite) FLRW cloud within a larger background, as shown in

Figure 1. A cosmological bounce and an inflationary phase can emerge naturally from two fundamental assumptions:

and

, which simply follow from considering a finite over-density of matter obeying the quantum exclusion principle, which prevents the density from overcoming some threshold value or ground state

.

Crucially, this quantum mechanism violates the strong energy condition (SEC) in classical GR. As was shown in [

1], the bounce requires a non-zero local curvature

. Both conditions sidestep the singularity GR theorems proposed by [

2], allowing us to formulate a novel solution to a pivotal issue in cosmological theory.

The bouncing scenario we formulate naturally extends to the subsequent stage of inflationary expansion when spatial curvature effects become negligible, resulting in the resolution of the horizon and flatness problems. Since the model is confined to a finite comoving region of spacetime, it introduces a finite comoving cutoff for super-horizon perturbations, potentially explaining anomalies in the CMB, such as the absence of structures beyond 66 degrees [

3]. This is a unique aspect of the model that is actually compatible with CMB observations, unlike the standard framework of inflationary cosmology. The value of this cut-off directly relates to a prediction of spatial curvature

.

A recent paper ([

1]) has numerically solved the Newtonian spherical collapse equations with a polytropic equation of state (EoS) inspired by neutron star (NS) conditions. It found bounces at or above nuclear saturation density with equivalent GR behavior in a closed FLRW metric. The GR bounce corresponds to the ground state of the matter, characterized by

(which is often termed a meta-stable state or quasi-deSitter in the framework of standard inflation). Here, we elaborate on the underlying mechanisms of this phenomenon and its implications for cosmic evolution, and we find new analytical and numerical solutions for the bounce, which are fully relativistic and within classical GR with a perfect fluid

.

Our approach relates closely to [

4,

5,

6], who studied the full general relativistic problem of a uniform and finite FLRW fluid ball (also called patch or cloud) expanding or contracting in a surrounding Schwarzschild vacuum. The contracting balls with pressure were also considered by Thompson and Whitrow [

7] and Bondi [

8], mainly to study gravitational collapse to black holes. Smoller and Temple [

9] consider exact solutions of the Einstein equations representing spherical shock waves that extend the Oppenheimer-Snyder model [

10] to the case of nonzero pressure inside the black hole.

Our approach is also related to cosmological bouncing scenarios (such as [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]) with some critical distinctions. Unlike other approaches, which modify gravity or try to quantize matter to explain the bounce, we find a solution for a perfect fluid EoS within standard GR, which is analogous to an effective scalar field in standard cosmic inflation models. It is worth noting here that when we include quantum effects in curved spacetime, even if we initially start with classical fluid with positive pressure, one gets negative pressure contributions as is shown in the studies of semi-classical gravity [

17,

18,

19]. The quantum exclusion principle sets a new universal goal for the theories of quantum gravity [

20,

21,

22]. Although the full study of quantum gravity is beyond the scope of this current study, it lays a foundation for what the actual theory of quantum gravity is supposed to achieve or to be consistent with. However, a pre-requirement for a complete theory of quantum gravity is the robust development of quantum field theory in curved spacetime [

23,

24,

25], which we aim to develop in the future for the non-singular origin of the Universe we present here.

The FLRW cloud bounce and subsequent inflation are driven by the degenerate pressure

, and this is supported by the hypothesis of the quantum exclusion principle, i.e., GR with quantum matter avoids singularities, which aligns very well with Misner’s thoughts on how quantum theory should avoid singularities [

26]. A new key ingredient for our approach is to consider a finite cloud, which allows us to incorporate spatial curvature, demonstrating its essential role in enabling the bounce. Finally, we address how cosmic acceleration emerges as a natural consequence of the bounce.

This work stands on its own, but it can also be used to extend and complement the Black Hole Universe (BHU) model ([

27,

28]) with a closed FLRW cloud

. The flat case

used previously is a good approximation all the way to the point where we approach the singularity but does not allow for a bounce to occur. By connecting the early and late phases of cosmic evolution, it provides a unified model that bridges gravitational collapse, cosmic inflation, and the present accelerated expansion of the Universe. Grounded in physical principles and supported by numerical simulations, this model offers a compelling alternative to the standard cosmological paradigm while addressing its unresolved challenges. We use

except when otherwise stated.

2. Spherical Collapse

Here, we want to model the collapse of a finite cloud or perturbation within a larger background. We will assume that the initial cloud is a spherical overdense region of a perfect fluid that is surrounded by an empty space, as shown in

Figure 1. This configuration is embedded in a larger volume containing a homogeneous, more diluted fluid. We also assume that

or negligible to start with. For an observer moving with a perfect fluid, the energy-momentum tensor is diagonal:

, where

is the relativistic energy density and

is the pressure. The cloud is initially very large and has a very low density, so the pressure and temperature can be neglected. The relativistic solution to this problem was given by [

29] `atom universe’ and is known today as the Lemaitre-Tolman-Bondi (LTB) model. The most general spherically symmetric metric in the comoving frame (i.e., moving with the fluid) is:

where

with

. The physical radius (or aerial coordinate)

corresponds to the area distance and reflects spherical symmetry. The functional form of

results from

in the comoving frame. The general solution to the Einstein field equation is:

where the over dots correspond to partial time derivatives. The mass-energy

M was introduced by [

29] and is sometimes called the active gravitational mass and coincides with the relativistic Misner-Sharp mass ([

30]), which is defined for the more general case with pressure [

31].

Assuming a homogeneous cloud

requires

H to also be homogeneous. Consequently,

and

k has to be constant. We then have:

where

and

are the initial density and comoving radius of the cloud so that the mass

m inside

remains constant. Note that we use comoving units such that

at present. This is the same solution as the FLRW solution, as expected. In general, we can choose

k to have any sign depending on the initial conditions. The case of interest here is

with

, which corresponds to an overdensity. The value of

relates to the initial velocity

of the cloud when

:

This reproduces the well-known result that a closed FLRW model exactly reproduces the relativistic spherical collapse model (see §87 in [

32]). In the Newtonian approximation, positive curvature (

) corresponds to a system with negative total energy, where gravitational attraction exceeds kinetic energy, leading to the collapse of the cloud under its own gravity. In GR, spatial curvature provides the geometric representation of a gravitationally bound system. Just as a bound orbit in Newtonian gravity (like a planet around a star) is confined, a closed universe (or a collapsing region) in GR is “confined” by its own curvature. The metric of our initial perturbation for

is therefore the same as the one of a closed FLRW metric:

Note that because

is cosmologically large, the corresponding curvature term

is subdominant until

. The solutions in Eqs.

5-, and also for Eqs.

2-, with

are the same as those in the Newtonian collapse studied in [

1] (note that the corresponding Newtonian energy

neglects the effects of

k). The FLRW cloud is a local and finite LTB solution in contrast to the standard FLRW metric, which is usually assumed to be global and infinite.

What happens in the LTB solution for

in the region of empty space

surrounding

R? [

29] also found a solution to this question. In his §11, he shows how variables can be changed to transform the LTB solution into the static Schwarzschild metric. This change of variables corresponds to a frame that is not comoving with the fluid, just as in the case of the static version of the de-Sitter metric (i.e., see [

33]). Another way to approach this question is to show that the FLRW metric matches the Schwarzschild metric without discontinuities. Two different versions of this approach were presented in [

34] and in §12.5.1 in [

35]. Such matching solution is what we call the FLRW cloud, which has the FLRW metric inside

and the Schwarzschild metric outside

([

36] also presented the case

and

for timelike and null junctions).

As the FLRW cloud collapses under its own gravity (

), the outer physical radius

shrinks and eventually crosses inside the corresponding Schwarzschild radius:

. When this happens, the FLRW cloud becomes a BH. For the cosmological case, both

and

are very large, which means that the corresponding densities are very small (this is not the case for stellar masses). The density at a given time

before the collapse to the singularity in the absence of any pressure is

This is the solution to Eq.

5 when the spatial curvature term is neglected. If we take

m to be as large as the mass of our observable Universe (

), we find from Eq. that at horizon crossing:

the density of the BH,

is:

At these low densities, it is reasonable to assume that the thermal pressure

P and temperature

T are negligible because the time scale of the collapse is negligible compared to the time scales for any interactions between neutral particles. The cold collapse proceeds inside the BH event horizon. Note in Eq.

9 how even up to one second before the singularity occurs, the density is small compared to nuclear saturation in a NS:

4. Degeneracy Pressure

Here, we draw an analogy of our understanding of the Universe with NSs and astrophysical black holes. As the collapsing cloud approaches the singularity (), the density increases without bound. However, once any fermionic constituent of the cloud reaches its quantum ground state, the Pauli Exclusion Principle generates a degeneracy pressure, , independent of temperature. Remarkably, this degeneracy pressure and the corresponding equilibrium density apply universally to systems ranging from atoms to NS despite their vast difference in mass—approximately times. For even larger masses, such as the mass of the Universe (about times greater than that of a NS), the degeneracy pressures of electrons, neutrons, or even quarks may not suffice to halt the collapse. Indeed, for masses exceeding the Tolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff (TOV) limit of 2–3 , a black hole forms, and the collapse proceeds within the event horizon, leaving the internal physics largely unexplored. A version of the Pauli Exclusion Principle should remain valid even under extreme conditions, as no two fermions can occupy the same quantum state. Thus, a new quantum ground state, characterized by a maximum density , could also emerge if electrons and quarks are not fundamental, preventing a true singularity. This notion lies at the heart of applying principles of quantum theory in the context of gravity, which offers a framework to circumvent singular collapse and explore the limits of physical laws in extreme conditions.

In the central regions of the collapsing cloud, where the bounce occurs, the pressure and density can be treated as approximately uniform in the comoving frame. The validity of this assumption was demonstrated in [

1] using hydrodynamical simulations.

We can see from Eq. that as , the relativist pressure . Appendix A shows one way to understand this in terms of scalar fields, where the EoS plays the role of the scalar potential .

We can define a cloud radius

from Eq.:

which corresponds to the radius

of the cloud when it reaches

if we neglect the effects of pressure. For the mass of the Universe

and when assuming nuclear saturation density (SD) as a lower limit

(Eq.

11):

This value of represents the beginning of the transition into the ground state. The model transitions from a state of constant total energy-mass (with a uniform but evolving energy density) to a state of uniform and time-invariant energy density.

We have found that the quantum exclusion principle leads to a ground state where the relativistic equation of state (EoS) becomes:

. This EoS is fundamentally distinct from the one typically considered under nuclear saturation in NSs. A key assumption for NS is that GR is negligible at scales of inter-quantum interactions. However, it is crucial to recognize that gravity is inherently nonlinear. The active mass-energy, as defined in Eq., includes not only matter but also gravitational energy, which can not be neglected. Notably, around the ground state, the active mass exhibits exponential growth or decay in the comoving frame, highlighting a purely gravitational effect. This behavior is also captured in the relativistic continuity equation (Eq.):

where we have included

c to illustrate that the second term

is purely relativistic and does not appear in the Newtonian equation. This equation demonstrates that once a constant density is reached, the EoS naturally transitions to

(back in units of

). This behavior is not captured by Newtonian dynamics (or relativistic corrections) and is therefore not present in conventional EoS models for NS, emphasizing the necessity of considering relativistic effects in describing such ground states. In the Newtonian approach, the pressure only appears as a force in the Euler equation. The GR analog of the Euler equation (or its first integral) is the Hubble-Lemaitre law in Eq.

12, which is independent of pressure. The two approaches come together when we combine the Euler equation with the continuity equation.

The other important difference between our comoving EoS and the NS modeling is that we are considering the collapse (and later expanding) phases and not a static solution. So, our EoS lives in the comoving frame, while NS EoS refers to a Newtonian rest frame. What does the relativistic EoS look like in the rest frame? This is presented in Appendix B.

5. Bouncing Solution

Bringing together the insights from the two previous sections, we can now explore what happens during the collapse of an FLRW cloud as it reaches its ground state density somewhere above nuclear saturation. For a constant

, Eq.

12- become:

This corresponds to a gravitational bounce (

and

) at:

Note how it is critical that

(or

) to have a bounce before the singularity (

) occurs. The bounce is only possible because both

and the cloud is finite (that is,

and

). It is physically inconsistent to perceive a bouncing scenario in an infinite FLRW cloud. This is reflected above by the mathematical fact that an infinite FLRW cloud has no bounce. The existence of

imposes a natural cutoff in the spectrum of super-horizon perturbations generated during collapse, bounce, or inflation. This cutoff shows up in the CMB sky as:

where

Gpc is the comoving radial distance to the CMB for

and

km/s/Mpc. Strong evidence for such a cutoff has been known since COBE and confirmed by WMAP and Planck ([

37,

38,

39]). [

40] estimated the homogeneity scale to be:

which implies:

which is the Gaussian curvature scale. This interpretation predicts a value

today (

) of:

which, for

, is consistent with a critical reanalysis of the Planck Legacy 2018 data [

41]. This result also agrees with a previous independent way of modeling the low quadrupole

measured in the WMAP power spectrum [

42]. The limits for

above assume that the homogeneity scale is the result of only

. This also explains the low quadrupole

[

40]. However, if the homogeneity scale or the low value of

has a different origin, then the value of

in the floating FLRW cloud could be smaller. Inflation preceded by a bounce requires

, and this could be found in upcoming cosmic surveys, as indicated by the analysis in [

41].

The exact solution to Eq. is:

where

is the time to/from the bounce (

) with

, and

is the radius of the cloud when it bounces:

which happens to be the gravitational radius of the ground state

.

6. Cosmic Inflation

The solution in Eq.

24 corresponds to an exponential expansion (or collapse) after (or before) the bounce, leading to a de-Sitter phase, just as in standard cosmic inflation. As mentioned before, the EoS plays the role of the inflation potential, and the actual solution is quasi-de-Sitter as we approach the respective ground state of the matter.

As an example, we can take the following toy ansatz to interpolate from

to

:

where

at the time when the density is half of

and quantities with a star index (

*) are given in units of

. Eq.

12 becomes:

Solving this numerically, we can obtain the exact equation of state

, using Eq.. For single field inflation like Starobinsky:

(where

is the scalar spectral index) [

43]. The current bound on the tensor-to-scalar ratio is

([

44]). This solution corresponds to

and is shown in

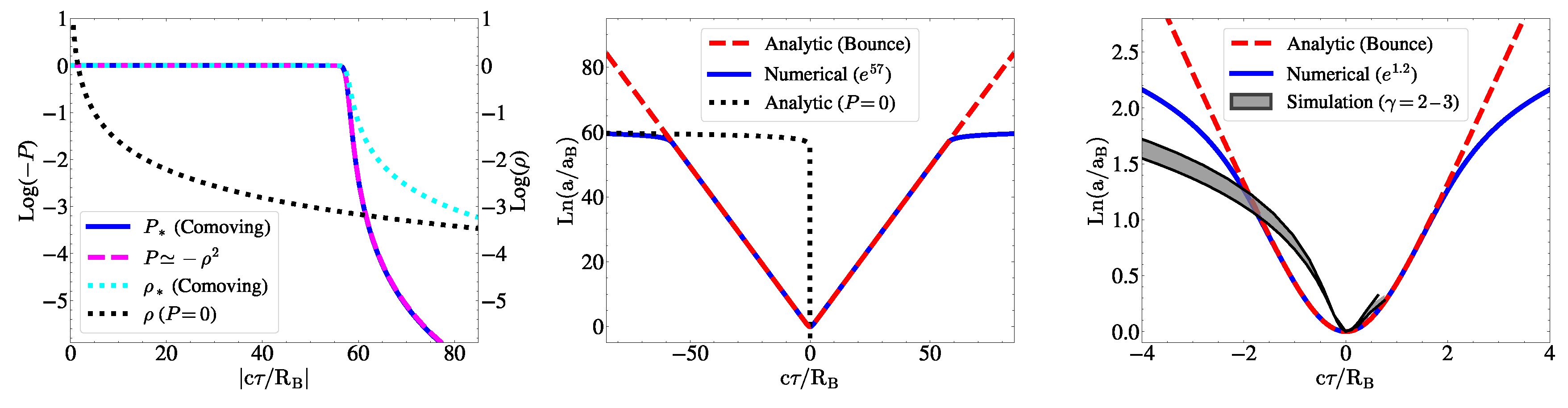

Figure 2. The corresponding EoS follows:

which corresponds to the generalized Chaplygin gas with

[

45].

The ground state is approached asymptotically, with the density remaining constant even as the scale factor grows or decreases exponentially. This behavior arises because the active mass m is no longer constant, a purely relativistic effect where the gravitational field itself contributes non-linearly to the source term. Consequently, the model transitions from a regime of constant energy-mass, characteristic of a Newtonian solution, to one of constant energy-density, which is inherently relativistic.

As mentioned before, the saturation densities in NSs and the nucleus of an atom are comparable with Eq.

11 despite the former having a mass

times larger than the latter. However, as discussed in [

1], the densities at which the condition

is fulfilled for masses much larger than that observed for NSs could be significantly higher than that of Eq.

11 so that the energy

of the corresponding cosmic inflation could be much larger. In Appendix A, we show a more detailed comparison of

with inflation parameters and CMB observations. The amplitude of CMB fluctuations relates to a ground state that has energy densities much larger than nuclear saturation. The quasi-scale invariant spectrum and quantum parity features observed in the CMB (see [

46]) will also be reproduced with our bouncing solution.

In summary, a bounce driven by degeneracy pressure could give rise to an epoch of cosmic inflation and reheating. This opens the possibility for an epoch of nucleosynthesis and recombination similar to that in the standard model (e.g., see [

47]). Note that in standard inflation, reheating requires an oscillatory scale factor around the matter-dominated phase after the exponential expansion, in typical single field inflation

where

M is inflaton mass. The equivalent process in terms of

is detailed in Appendix A. This process has the potential to enable nucleosynthesis and recombination in a manner similar to the standard Big Bang model. More importantly, it also provides an alternative framework for understanding both early and late-time cosmic acceleration.

7. Cosmic Acceleration

There is compelling observational evidence that the cosmic expansion is accelerating:

[

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53]. This acceleration appears to be dominated by the cosmological constant

. The

term can be interpreted as either a fundamental modification of General Relativity (GR), denoted as

, or as an effective dark energy (DE) fluid,

, analogous to the ground state

described earlier, but with a much smaller energy density,

.

Regardless of the interpretation, the corresponding characteristic length scale,

is vastly larger than the nuclear saturation scale

(i.e.,

). Consequently,

can be neglected in our discussion of the gravitational bounce and the corresponding inflationary period.

The measured value of

is extremely small but non-zero, and its fundamental origin remains an open question. Although its connection to the fundamental laws of physics is unclear, its effect is well understood: it induces an event horizon,

, in FLRW space-time:

beyond which regions (

) are not causally connected to the interior (

). The standard assumption in cosmology is that the universe beyond

is identical to the interior. However, this assumption presents two fundamental issues:

Lack of causal explanation: The standard approach cannot provide a mechanism to explain how the universe could be the same beyond . Cosmic inflation does not solve this puzzle because even under exponential expansion , we have that R is always . This is because the comoving distance travel by light during domination exactly cancels the exponential expansion in .

Violation of the variational principle: Einstein’s field equations require that the metric asymptotically approaches Minkowski space at large distances, which is not satisfied if the universe extends indefinitely.

Instead, if we assume that the region beyond

is empty, both of these issues are resolved. This leads to a finite universe with size

and a finite total mass

m contained within it. The exterior is then naturally described by the Schwarzschild metric. This agrees well with the FLRW cloud model presented here in previous sections and in

Figure 1. For consistency, we need to identify

with the Schwarzschild radius:

as both quantities are constant. This immediately provides a physical interpretation of

:

Thus, simply corresponds to the total mass m of our finite universe. This also explains why is small but nonzero: it is directly linked to the total mass of the universe as in our FLRW cloud model. Thus, the measurement of a can be interpreted as a measurement of m and a confirmation that we live within a large, but finite FLRW cloud model. This is also consistent with our new interpretation of the origin of the bounce and cosmic inflation presented here.

This reasoning provides a straightforward and intuitive explanation of

without requiring detailed calculations. Such calculations are presented in [

36]. By applying the relevant matching conditions, it is found that the radial null geodesics

satisfy Israel’s matching conditions and that the action principle correctly includes the extrinsic curvature boundary term,

.

This boundary interpretation of

corresponds to the Black Hole Universe (BHU) model. For observational values

and

km/s/Mpc, we obtain:

with uncertainties from [

54]. Note that

in Eq.

22, which indicates that the perturbation form before becoming a black hole.

8. Discussion and Conclusion

This paper presents a novel solution to the relativistic spherical collapse model for a bounded perturbation (

). The key innovation lies in the introduction of a variable equation of state,

, which asymptotically evolves from a pressureless, homogeneous state to a ground state characterized by a time-independent energy density. This transition naturally gives rise to a de Sitter phase in the final stages of collapse—immediately preceding the bounce—and persists throughout the ensuing expansion. The bounce itself admits an analytical expression, provided in Eq.

24.

The cosmological implication of this new approach is a novel understanding of the origin of the universe that emerges from the collapse and subsequent bounce of a spherically symmetric matter distribution. We show that upon reaching a quantum ground state, the relativistic matter equation of state (EoS) transitions from

to

in the comoving frame. The relativistic degenerate pressure generated in this state halts the collapse and initiates a bounce and an inflationary expansion. We discussed how this mechanism parallels phenomena in NS physics and core-collapse supernovae (see reviews by [

55,

56,

57,

58]), where the ground state is determined by nucleonic or quark interaction potentials within proto-NS. On the other hand, the expansion mechanism right after the bounce also parallels with that of cosmic inflation as detailed in Appendix A.

The non-singular bounce that happens inside a closed FLRW cloud (i.e., a finite-sized Universe trapped inside an event horizon) is induced by quantum matter EoS, which results in degenerate negative pressure. This same process drives an exponential expansion analogous to cosmic inflation, offering a novel solution to key challenges in standard cosmology, such as the origin of inflation and dark energy. Our findings highlight the profound implications of relativistic quantum principles in shaping the early Universe.

We start from a low-density cloud with

where

is the adimensional scale factor in units of the value today

. The key simplicity of this model is that the BH is not an ad-hoc initial condition to our system but a consequence of gravitational collapse. Without this, there is no argument for

. This will happen for any initial condition where the initial density is sufficiently low. Harrison-Zeldovich-Peebles (1970) [

59,

60,

61] independently argued that gravitational instability alone (without inflation) would naturally produce a scale-invariant spectrum of perturbations out of an FLRW metric. Such perturbations will give rise to overdensities such as the ones considered here as the starting point to our Universe. This is our new guess for the “initial condition".

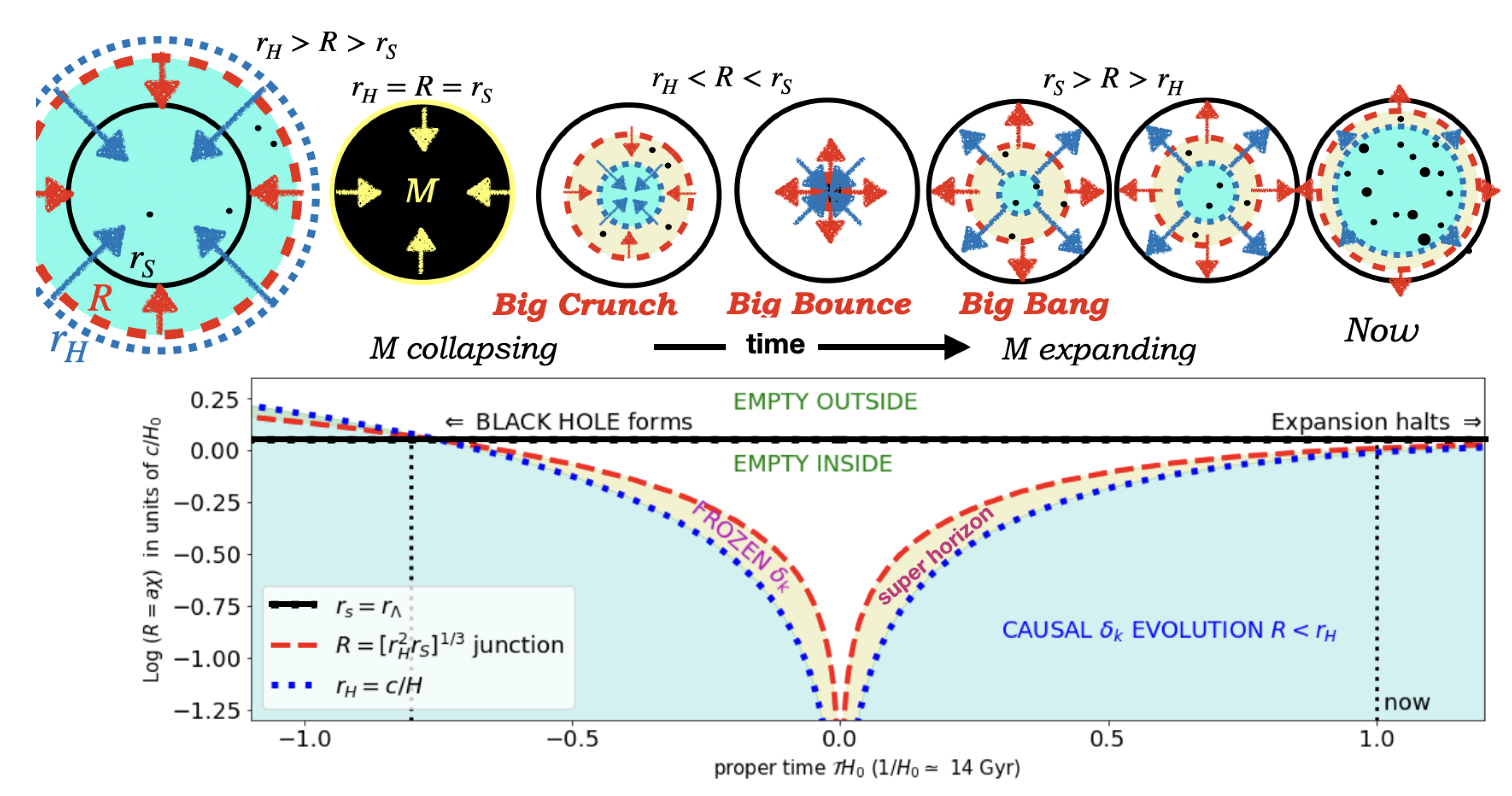

Figure 3 shows the full evolution of the finite FLRW cloud radius,

, illustrating how the horizon problem is resolved within the bounce model. In the middle panel of

Figure 2, we now present the exact bouncing solution, comparing the analytical expression for the scale factor

given in Eq.

24 with the numerical solution of Eq.

27. For reference, we also plot the singular analytic solution for

. Such singular behavior is unavoidable for an infinite cloud (

or

) or in a flat or open geometry (

). Note how the inflationary phase has the right number of e-folds

consistent with the scalar spectral index

measured by Planck [

43].

It is evident that the analytic solution in Eq.

24 is valid only for the inflationary phase, i.e., near the bounce, whereas the numerical solution accounts for the entire evolution, including the pre-bounce phase when

. Before reaching the bounce, the numerical solution follows the pressureless analytic case closely, which is expected since the pressure is initially vanishing and then transitions smoothly into a constant (negative) degeneracy pressure (

), as shown in the left panel. In this regime, the equation of state (EoS) is well approximated by

(dashed line). When we plot the Pressure calculated for the numerical model (labeled

) as a function of the corresponding density and fit it, the fitting curve is

with

and

. This can be interpreted as a polytropic EoS with

.

Furthermore, the transition point is clearly marked: as soon as pressure begins to build up, the numerical solution in the middle panel shifts from the analytic solution (dotted line) to the analytic bounce solution (dashed line), denoting exponential collapse and vice-versa for exponential expansion.

The right panel provides a zoomed-in view of the bounce region, where we compare our asymptotic analytical solution with the numerical Newtonian simulations of [

1], which adopt an equation of state of the form

. This type of EoS serves as a reasonable approximation for nuclear degenerate matter, with

to 3, in the Newtonian framework [

62]. While the Newtonian simulations remain an approximation, we observe that both models yield a strikingly similar exponential expansion post-bounce, as also noted by [

1]. Note that the Newtonian simulation results presented here are for a 20 M

⊙ cloud, for which the bounce occurs at around nuclear saturation densities and the expansion has

e-folds. For larger masses, we will have a larger number of e-folds as in the middle panel for the mass of our Universe.

The analytic solution we found in Eq.

24 is one of the cases considered in Eq.7 in [

12], which corresponds to a de-Sitter Universe with closed curvature. Instead of degeneracy pressure, this model arises from quadratic curvature modification of the Einstein-Hilbert action motivated by 1-loop self-energy contributions due to quantum matter, which leads to the first model of cosmic inflation ([

63]). But the reason to consider closed curvature (other than to produce a bounce as in [

11]) is not clear in this model. In the BHU model, the spatial curvature naturally results from the spherical collapse of a large overdensity confined to a finite region of spacetime.

Figure 3 in [

36] illustrates how the boundary

of the FLRW cloud is always outside the observational window for any (off-centered) observer inside the cloud. This is a general property of quasi-de-Sitter space and implies that the BHU does not result in observed anisotropies in the background of the cloud boundary. But the bounce and the initial cloud’s comoving radius

can result in a cutoff of the super-horizon quantum perturbations generated during inflation, which can be observed in the CMB [

3,

40,

64] and results in the constraint given by Eq.

22. Such cutoff, together with parity asymmetry, predicts a lower quadrupole, which can explain several other CMB anomalies (see [

25,

46,

65]).

Our analysis shows that the observed cosmological constant

can be interpreted as a boundary effect from the gravitational radius of the BHU, aligning with the idea of an effective

term without invoking exotic physics. The implications of this model extend to the generation of super-horizon perturbations, the observed entropy ratio of baryons to photons, and the potential origins of dark matter ([

66]). Future studies should explore the role of temperature and radiation in nuclear fusion during the bounce to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the transition from collapse to expansion.

The smoking gun for our bouncing scenario is the presence of both a small spatial curvature and a small

term. While the latter has already been measured with high precision, the former remains a testable prediction (given here in Eq.

23) for upcoming cosmological surveys. The Planck PR3 lensed power spectrum revealed a

preference for positive curvature [

67], with

, in agreement with our Eq.

23. Recent results from ACT [

68] similarly suggest a slight preference for positive curvature (see their Fig. 9), although the current uncertainties remain too large to decisively rule out a flat universe. The latest DESI data [

69] echo this trend, also hinting at a mild preference for positive curvature. Together, the ACT and DESI results support a growing pattern: when multiple high-precision datasets are combined, persistent tensions with the standard

CDM model begin to emerge. Notably, the combination of DESI and CMB data reveals

evidence for a

term that evolves slowly over cosmological time. In our framework, where

, this corresponds to a decreasing FLRW cloud mass

m over time. If confirmed, such behavior could be interpreted as a signature of quantum horizon effects—such as black hole evaporation via Hawking radiation [

23,

24,

70]. Nonetheless, individual cosmological measurements have not yet yielded definitive evidence for departures from the standard

CDM scenario.