2. Patients and Methods

- 1.

Aims and objectives

This study aims to describe the characteristics of COVID-19 diagnosed LTR throughout the successive pandemic stages or "waves", evaluating the particularities and changes over the course of the disease and its management over time, determining the risk factors for severe COVID-19 disease in LTR and assessing the previously described in literature.

- 2.

Study design

A single-center observational descriptive study was carried out on a 307 COVID-19 cases cohort at the 12 de Octubre University Hospital in Madrid, from February 2020 to December 2023, in LTR.

A case-registry database was created. The patients were recruited through communications to the transplant clinic, whether they required or not admission due to the infection, plus those who were admitted to the hospital due to COVID-19 disease. Data were obtained by conducting a survey during the follow-up consultation in person or by telephone, completing the information with the hospital electronic medical record and medical reports from other centers.

- 3.

Data collection

Epidemiological data (sex, age), comorbidities (history of obesity, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, chronic and/or acute kidney disease, smoking), transplant-related data (indication and date of transplantation, immunosuppression), COVID-19-related data (symptoms, technique and date of diagnosis, treatment received, vaccination, association with altered liver enzymes), survival data (death due to COVID or other causes, overall survival) and follow-up data were collected.

The development of thrombotic events such as infarction, pulmonary thromboembolism or deep vein thrombosis [

20] in the context of COVID-19 disease was also investigated and/or questioned.

- 4.

Definitions

Comorbidities. The following comorbidities were considered independently:

- (1)

Obesity (Body mass index ≥ 30 kg/m 2).

- (2)

Acute or chronic kidney disease (presence at diagnosis of plasma creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL due to acute kidney injure, or as the baseline creatinine in patients with chronic kidney disease).

- (3)

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

- (4)

Bronchial asthma.

- (5)

Hypertension (HTN).

- (6)

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2D).

- (7)

Cardiovascular events or cardiovascular risk factors: arrhythmia, infarction, cardiomyopathy, heart failure or coronary artery disease or the combination of HTN, T2D and dyslipidemia as cardiovascular risk factors.

- (8)

Altered liver enzymes (elevation of liver enzyme (aminotransferase) above the upper limit of normal).

Diagnostic criteria for COVID-19. The following have been considered diagnostic for COVID-19:

- (1)

A positive real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test for SARS-CoV-2.

- (2)

A positive antigen detection test [

21].

- (3)

Patients with compatible symptoms and radiological findings suggestive of COVID-19, during the first weeks of the study, prior to the establishment of diagnostic tests [

22].

- (4)

A positive antibody test result before vaccination [

23,

24].

Severe COVID-19 disease. Five scenarios were described [

9]:

- (1)

Required hospitalization.

- (2)

Required admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU).

- (3)

Associated respiratory failure: baseline oxygen saturation

≤ 93%, partial blood pressure of oxygen (PaO2) / oxygen concentration (FiO2)

≤ 30 mmHg [

25]. Need for non-invasive ventilatory support.

- (4)

Required invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV).

- (5)

Died from COVID-19 disease.

6. Statistital Analysis

The data set of the study was summarized with descriptive statistical analysis. Quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median (p50) and interquartile range (IQR, p25-p75). Normality of the distributions was tested with Saphiro-Wilk. Qualitative variables were expressed in absolute numbers (number of cases) and relative frequencies (percentage).

Relationships and comparison between groups [

1] patients hospitalized vs. COVID-19 disease outpatient management, [

2] admitted or not to the ICU; [

3] with or without respiratory failure; [

4] patients who required or did not require invasive mechanical ventilation; [

5] patients who did or did not die from COVID-19 and [

6] differences between the waves] were evaluated using the chi-square test (χ2) or Fisher's exact test, Student's t test, Mann-Whitney U test, ANOVA or Kustal-Wallis test, as appropriate.

Binary logistic regression was used to analyze the risk factors associated with each one of the severe COVID-19 scenarios. The results were expressed as odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Subsequent multivariate analysis was performed in those severe COVID-19 scenarios groups with a N ≥ 30 (respiratory failure group and hospital admission group), considering risk factors that were found to be statistically significant in the univariate analysis and those considered relevant within the study objectives, using the stepwise regression method.

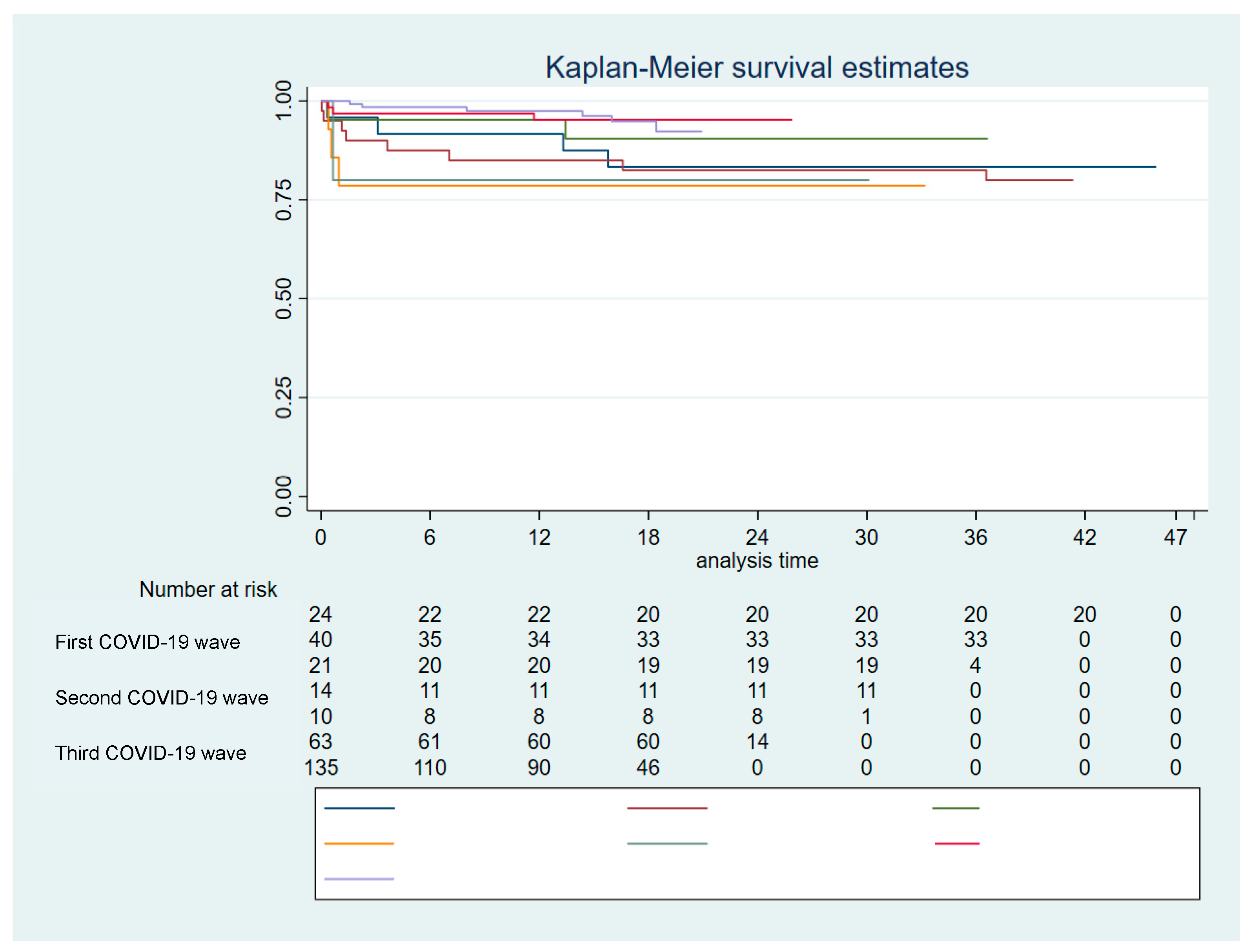

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier method. Log rank test was used to statistically compare the curves. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was used to explore predictors of death related to COVID-19.

The statistical software used was Stata for Windows version 16 (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC). All analyses were conducted using an alpha significance level of 5% for a two-tailed p-value.

Ethical and Regulatory Approval

The local Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved the study protocol (ref. no. 20/151) and granted a waiver of informed consent due to its retrospective observational design.

Results

- 1.

Characteristics of the study population

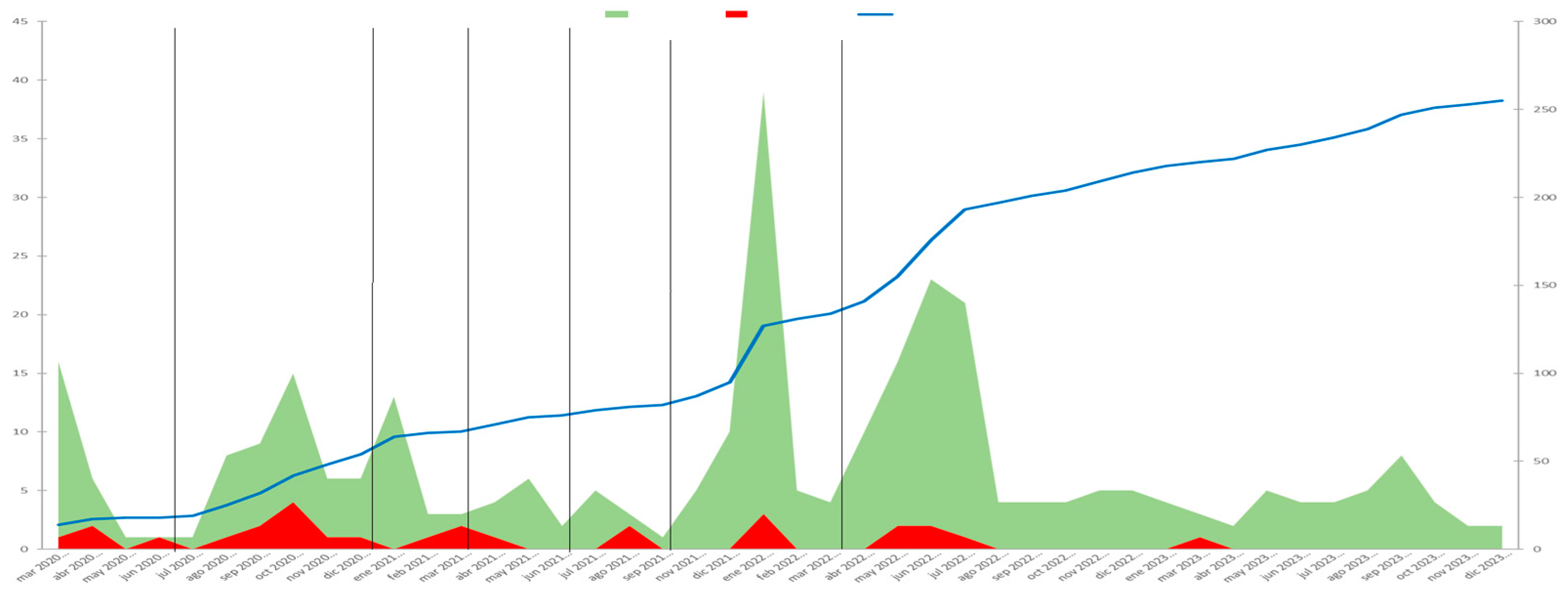

542 patients who attended follow-up consultations or were admitted to hospital during the study period were contacted in person and/or by telephone. Of these, 281 patients were identified as having been diagnosed with COVID-19. A total of 307 cases of COVID-19 disease were diagnosed, as 1 patient suffered 2 reinfections, and 24 patients had 1 reinfection. 24, 40, 21, 14, 10, 63 and 135 cases of disease were diagnosed in each period, respectively.

Of the 281 patients, 194 (69.04%) were male. The median age at diagnosis was 61 years (IQR 55 - 69). Regarding medical history, 13 (4.64%) had a history of COPD, 6 (2.14%) were asthmatic, 109 (38.93%) had hypertension and 115 (41.07%) had T2D. Obesity was reported in 57 patients (20.73%), and 46 (16.85%) were smokers.

171 patients (61.29%) had a history of cardiovascular events or a combination of multiple cardiovascular risk factors. In 23 cases (7.52%) the creatinine at diagnosis was greater than 2 mg/dl.

The main indications for liver transplantation were alcoholic cirrhosis in 99 patients (35.23%), followed by HCV cirrhosis in 94 patients (33.45%) and hepatocellular carcinoma in 82 (29.18%).

- 2.

Symptoms

The median time from transplantation to diagnosis was 94.46 months (IQR 41.44 - 185.21).

Symptons at diagnosis are given in

Table 1A. The main symptoms were cough in 120 cases (39.74%), asthenia in 98 (32.45%), fever in 77 cases (25.50%) and myalgia in 73 cases (24.17%). In 60 cases (19.87%) the disease was asymptomatic.

In this study, there were two thrombotic events associated with COVID-19 disease: one patient was diagnosed with a partial thrombosis of the inferior vena cava and another patient was diagnosed with an asymptomatic pulmonary thromboemnolism. No cases of acute graft dysfunction associated with COVID-19 disease were identified.

- 3.

Immunosupression

At the time of diagnosis, 189 patients (61.76%) were receiving calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), 184 (60.13%) mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), 40 (13.07%) mTOR inhibitors (mTORi), 17 (5.56%) were on corticosteroid treatment and 3 (0.98%) were receiving azathioprine (AZT).

- 4.

Diagnosis of COVID-19 disease

The diagnosis was established by antigen detection testing in 186 cases (60.59%), by RT-PCR in 110 (35.83%), was serological in 6 cases (1.95%), and clinical in 5 cases (1.63%). In asymptomatic patients, diagnosis was carried out by performing a PCR prior to a scheduled admission or test or by obtaining a positive RT-PCR test after having been in close contact of confirmed COVID-19 cases.

A chest X-ray was performed in 84 cases, with a diagnosis of lobar pneumonia in 10 cases (3.64%) and bilateral pneumonia in 46 cases (16.73%). Radiological findings throughout the waves are given in

Table 1B.

- 5.

Treatment for COVID-19 disease

Treatment for COVID-19 disease is given in

Table 2. 64 cases (20.84%) required antibiotics. Administered antibiotics included beta-lactams, macrolides, quinolones or oxazolidinones. Corticosteroids were administered in 45 cases (14.66%). Patients received prophylactic anticoagulation in 38 cases (12.38%). 27 patients received Remdesivir 27 (8.79%), 13 patients received hydroxychloroquine (4.23%), 3 patients received Kaletra (0.98%), and 3 patients received Paxlovid (0.98%).

- 6.

Vaccination

The median time from vaccination to onset of symptoms was 5.87 months (IQR 3.23 - 9.03). In 211 cases (68.95%) patients had received at least one dose of the vaccine at diagnosis, in 93 cases (30.39%) they had not received any dose.

Table 3 shows the number of doses administered at diagnosis along the periods.

- 7.

Severe COVID-19 disease

34 patients (11.07%) had respiratory failure, 5 (1.63%) required IMV, 72 (23.45%) were admitted to the hospital and 12 of them (3.91%) were admitted to the ICU. 12 patients (3.91%) died from COVID-19.

Characteristics of patients who suffered respiratory failure, required mechanical ventilation, were hospitalized, were admitted to the ICU and died from COVID-19 are given in

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 9 respectively.

Table 4.

Respiratory failure in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

Table 4.

Respiratory failure in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

| Table 4. Respiratory failure in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19 |

Logistic Regression Analysis |

| |

Respiratory failure |

|

|

|

| |

Total (N = 307) |

No (N = 273) |

Yes (N = 34) |

p-value |

OR (p-value) |

95%CI |

| Age (years), median (IQR) |

61 (54 – 68) |

61 (53 – 68) |

68 (59 – 73) |

0.002 |

1.05 (0.002) |

1.02 - 1.09 |

| IMC (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

26.3 (23 – 29) |

26.05 (22.7 – 29) |

28 (25.5 – 29.7) |

0.026 |

OR 1.09 (0.017) |

1.017 - 1.18 |

| Male sex, N (%) |

209 (68.08%) |

180 (65.93%) |

29 (85.29%) |

0.022 |

|

|

| Female sex, N (%) |

98 (31.92%) |

93 (34.07%) |

5 (14.71%) |

0.33 (0.028) |

0.12 - 0.89 |

| Number of vaccines at diagnosis |

3 (0 – 3) |

3 (0 – 3) |

0 (0 – 2) |

< 0.001 |

0.52 (< 0.001) |

0.39 - 0. 69 |

| Vaccination N (%) |

211 (68.95%) |

199 (73.16%) |

12 (35.29%) |

< 0.001 |

0.2 (< 0.001) |

0.094 - 0.42 |

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

5.87 (3.23 – 9.03) |

6.46 (3.31-9.11) |

2.89 (0.62-4.36) |

0.003 |

0.7 (0.011) |

0.54 - 0.92 |

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

94.46 (41.44-185.21) |

94.46 (41.44-184.49) |

95.08 (51.28-188.75) |

0.79 |

|

|

|

Kidney failure(Creatinine≥ 2 mg/dL)

|

23 (7.52%) |

16 (5.88%) |

7 (20.59%) |

0.002 |

4.12 (0.004) |

1.57 - 10.97 |

| COPD, N (%) |

13 (4.25%) |

10 (3.68%) |

3 (8.82%) |

0.16 |

|

|

| Asthma, N (%) |

6 (1.96%) |

6 (2.21%) |

0 |

0.38 |

|

|

| HTN, N (%) |

117 (38.24%) |

94 (34.56%) |

23 (67.65%) |

< 0.001 |

3.96 (< 0.001) |

1.85 - 8.47 |

| Cardiovascular events and / or risk factors |

181 (59.34%) |

152 (56.09%) |

29 (85.29%) |

0.001 |

4.54 (0.002) |

1.7 - 12 |

| T2D, N (%) |

125 (40.85%) |

102 (37.50%) |

23 (67.65%) |

< 0.001 |

3.48 (< 0.001) |

1.63 - 7.45 |

| Altered liver enzymes, N (%) |

20 (6.54%) |

16 (6.81%) |

4 (5.63%) |

0.73 |

|

|

| Smokers, N (%) |

50 (16.72%) |

44 (16.54%) |

6 (18.18%) |

0.53 |

|

|

| Asthenia, N (%) |

98 (32.45%) |

81 (30.22%) |

17 (50.00%) |

0.02 |

2.31 (0.023) |

1.12 - 4.75 |

| Dyspnea, N (%) |

45 (14.9 %) |

25 (9.33%) |

20 (58.82%) |

< 0.001 |

13.88 (< 0.001) |

6.25 - 30.82 |

| Fever, N (%) |

77 (25.5 %) |

59 (22.01%) |

18 (52.94%) |

< 0.001 |

3.98 (< 0.001) |

1.92 - 8.29 |

| Cough, N (%) |

120 (39.74%) |

103 (38.43%) |

17 (50 %) |

0.19 |

|

|

| Chest pain, N (%) |

12 (3.97%) |

9 (3.36%) |

3 (8.82%) |

0.12 |

|

|

| Diarrhoea, N (%) |

32 (10.6 %) |

27 (10.07%) |

5 (14.71%) |

0.41 |

|

|

| Anorexia, N (%) |

14 (4.64%) |

10 (3.73%) |

4 (11.76%) |

0.036 |

3.44 (0.047) |

1.02 - 11.65 |

|

Chest X-ray findings,N (%)

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

| Not performed |

191 (69.45%) |

189 (77.78%) |

2 (6.25%) |

|

|

|

| Normal |

28 (10.18%) |

27 (11.11%) |

1 (3.13%) |

|

|

|

| Bilateral pneumonia |

46 (16.73%) |

21 (8.64%) |

25 (78.13%) |

|

112.5 (< 0.001) |

24.87 – 508.84 |

| Lobar pneumonia |

10 (3.64%) |

6 (2.47%) |

4 (12.50%) |

|

63 (< 0.001) |

9.59 – 413.67 |

| Azathioprine, N (%) |

3 (0.98%) |

2 (0.74%) |

1 (2.94%) |

0.22 |

|

|

| Corticosteroids, N (%) |

17 (5.56%) |

17 (6.25%) |

0 |

0.13 |

|

|

| mTORi, N (%) |

40 (13.07%) |

35 (12.87%) |

5 (14.71%) |

0.76 |

|

|

| MMF, N (%) |

184 (60.13%) |

154 (56.62%) |

30 (88.24%) |

< 0.001 |

5.74 (< 0.001) |

1.97 - 16.76 |

| CNIs, N (%) |

189 (61.76%) |

177 (65.07%) |

12 (35.29%) |

< 0.001 |

0.29 (< 0.001) |

0.14 - 0.62 |

Table 5.

IMV in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

Table 5.

IMV in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

| Table 5. IMV in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19 |

Logistic Regression Analysis |

| |

Mechanical ventilation |

|

|

|

| |

Total (N = 306, 1 lost case) |

No (N = 301) |

Yes (N = 5) |

p-value |

OR (p-value) |

95%CI |

| Age (years), median (IQR) |

61 (54 – 68) |

61 (53 – 68) |

68 (62 – 74) |

0.1 |

|

|

| IMC (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

26.3 (23 – 29) |

26.3 (22.7 – 29) |

28 (25.5 – 29.7) |

0.21 |

|

|

| Male sex, N (%) |

208 (67.97%) |

203 (67.44%) |

5 (100 %) |

0.12 |

|

|

| Female sex, N (%) |

98 (32.03%) |

98 (32.56%) |

0 |

|

|

| Number of vaccines at diagnosis |

3 (0 – 3) |

3 (0 – 3) |

0 (0 – 2) |

0.2 |

|

|

| Vaccination N (%) |

211 (69.18%) |

209 (69.67%) |

2 (40.00%) |

0.15 |

|

|

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

5.87 (3.23 - 9.03) |

5.87 (3.25 - 9.02) |

4.61 (0.1 – 9.11) |

0.56 |

|

|

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

94.72 (43.31-185.21) |

94.46 (43.31-184.49) |

134.75 (78.23-191.93) |

0.48 |

|

|

|

Kidney failure (Creatinine≥ 2 mg/dL)

|

23 (7.54%) |

23 (7.67%) |

0 |

0.52 |

|

|

| COPD, N (%) |

13 (4.26%) |

13 (4.33%) |

0 |

0.63 |

|

|

| Asthma, N (%) |

6 (1.97%) |

6 (2 %) |

0 |

0.75 |

|

|

| HTN, N (%) |

117 (38.36%) |

114 (38.00%) |

3 (60 %) |

0.32 |

|

|

| Cardiovascular events and / or risk factors |

180 (59.21%) |

176 (58.86%) |

4 (80 %) |

0.34 |

|

|

| T2D, N (%) |

124 (40.66%) |

119 (39.67%) |

5 (100 %) |

0.006 |

|

|

| Altered liver enzymes, N (%) |

20 (6.56%) |

20 (6.67%) |

0 |

0.55 |

|

|

| Smokers, N (%) |

50 (16.78%) |

49 (16.72%) |

1 (20 %) |

0.94 |

|

|

| Asthenia, N (%) |

98 (32.56%) |

96 (32.43%) |

2 (40 %) |

0.72 |

|

|

| Dyspnea, N (%) |

45 (14.95%) |

41 (13.85%) |

4 (80 %) |

< 0.001 |

24.87 (0.004) |

2.71 – 228.14 |

| Fever, N (%) |

77 (25.58%) |

74 (25.00%) |

3 (60 %) |

0.075 |

|

|

| Cough, N (%) |

120 (39.87%) |

119 (40.20%) |

1 (20 %) |

0.36 |

|

|

| Chest pain, N (%) |

12 (3.99%) |

12 (4.05%) |

0 |

0.65 |

|

|

| Diarrhoea, N (%) |

32 (10.63%) |

31 (10.47%) |

1 (20 %) |

0.49 |

|

|

| Anorexia, N (%) |

14 (4.65%) |

14 (4.73%) |

0 |

0.62 |

|

|

|

Chest X-ray findings,N (%)

|

|

|

|

0.008 |

|

|

| Not performed |

191 (69.71%) |

190 (70.63%) |

1 (20%) |

|

|

|

| Normal |

28 (10.22%) |

28 (10.41%) |

0 |

|

|

|

| Bilateral pneumonia |

45 (16.42%) |

42 (15.61%) |

3 (60%) |

|

13.57 (0.025) |

1.37 – 133.71 |

| Lobar pneumonia |

10 (3.65%) |

9 (3.35%) |

1 (20%) |

|

21.11 (0.036) |

1.22 – 365.44 |

| Azathioprine, N (%) |

3 (0.98%) |

2 (0.67%) |

1 (20%) |

< 0.001 |

37.25 (0.006) |

2.78 – 499.16 |

| Corticosteroids, N (%) |

17 (5.57%) |

17 (5.67%) |

0 ( |

0.58 |

|

|

| mTORi, N (%) |

40 (13.11%) |

40 (13.33%) |

0 |

0.38 |

|

|

| MMF, N (%) |

183 (60%) |

179 (59.67%) |

4 (80%) |

0.36 |

|

|

| CNIs, N (%) |

188 (61.64%) |

186 (62%) |

2 (40%) |

0.32 |

|

|

Table 6.

Hospital admission in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

Table 6.

Hospital admission in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

| Table 6. Hospital admission in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19 |

Logistic Regression Analysis |

| |

Hospital admission |

|

|

|

| |

Total (N = 307) |

No (N = 235) |

Yes (N = 72) |

p-value |

OR (p-value) |

95%CI |

| Age (years), median (IQR) |

61 (54 – 68) |

60 (52 – 67) |

64.5 (56 – 71.5) |

0.002 |

1.04 (p = 0.001) |

1.02 – 1-07 |

| IMC (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

26.3 (23 – 29) |

26.1 (22.5 – 29) |

27.32 (24.2 – 29.7) |

0.009 |

1.08 (p = 0.011) |

1.02 – 1.15 |

| Male sex, N (%) |

209 (68.08%) |

156 (66.38%) |

53 (73.61%) |

0.25 |

|

|

| Female sex, N (%) |

98 (31.92%) |

79 (33.62%) |

19 (26.39%) |

|

|

| Number of vaccines at diagnosis |

3 (0 – 3) |

3 (1 – 4) |

0 (0 – 3) |

< 0.001 |

0.63 (p < 0.001) |

0.53 – 0.75 |

| Vaccination N (%) |

211 (68.95%) |

178 (76.07%) |

33 (45.83%) |

< 0.001 |

0.23 (p < 0.001) |

0.15 – 0.46 |

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

5.87 (3.23 – 9.03) |

6.26 (3.28 – 9.18) |

3.61 (2.2 – 6.79) |

0.073 |

|

|

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

94.46 (41.44-185.21) |

93.05 (40.85-177.64) |

101.98 (43.74-192.44) |

0.26 |

|

|

|

Kidney failure (Creatinine≥ 2 mg/dL)

|

23 (7.52%) |

12 (5.13%) |

11 (15.28%) |

0.004 |

3.33 (p = 0.006) |

1.4 – 7.93 |

| COPD, N (%) |

13 (4.25%) |

7 (2.98%) |

6 (8.45%) |

0.0.45 |

3 (p = 0.055) |

0.97 – 9.26 |

| Asthma, N (%) |

6 (1.96%) |

6 (2.55%) |

0 |

0.17 |

|

|

| HTN, N (%) |

117 (38.24%) |

78 (33.19%) |

39 (54.93%) |

< 0.001 |

2.45 (p = 0.001) |

1.43 – 4.21 |

| Cardiovascular events and / or risk factors |

181 (59.34%) |

127 (54.27%) |

54 (76.06%) |

0.001 |

2.67 (p = 0.001) |

1.46 – 4. 89 |

| T2D, N (%) |

125 (40.85%) |

85 (36.17%) |

40 (56.34%) |

0.002 |

2.28 (p = 0.003) |

1.33 – 3.9 |

| Altered liver enzymes, N (%) |

20 (6.54%) |

16 (6.81%) |

4 (5.63%) |

0.73 |

|

|

| Smokers, N (%) |

50 (16.72%) |

41 (17.75%) |

9 (13.24%) |

0.14 |

|

|

| Asthenia, N (%) |

98 (32.45%) |

70 (30.43%) |

28 (38.89%) |

0.18 |

|

|

| Dyspnea, N (%) |

73 (24.17%) |

62 (26.96%) |

11 (15.28%) |

0.043 |

24.56 (p < 0.001) |

10.91 – 55.25 |

| Fever, N (%) |

77 (25.50%) |

41 (17.83%) |

36 (50.00%) |

< 0.001 |

4.61 (p < 0.001) |

2.6 – 8.17 |

| Cough, N (%) |

120 (39.74%) |

80 (34.78%) |

40 (55.56%) |

0.002 |

2.34 (p = 0.002) |

1.37 – 4.01 |

| Chest pain, N (%) |

12 (3.97%) |

3 (1.30%) |

9 (12.50%) |

< 0.001 |

10.81 (p < 0.001) |

2.84 – 41.12 |

| Diarrhoea, N (%) |

32 (10.60%) |

15 (6.52%) |

17 (23.61%) |

< 0.001 |

4.43 (p < 0.001) |

2.08 – 9.42 |

| Anorexia, N (%) |

14 (4.64%) |

8 (3.48%) |

6 (8.33%) |

0.087 |

|

|

|

Chest X-ray findings,N (%)

|

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

| Not performed |

191 (69.45%) |

182 (87.92%) |

9 (13.24%) |

|

|

|

| Normal |

28 (10.18%) |

19 (9.18%) |

9 (13.24%) |

|

|

|

| Bilateral pneumonia |

46 (16.73%) |

4 (1.93%) |

42 (61.76%) |

|

212.33 (p < 0.001) |

3.39 – 27.04 |

| Lobar pneumonia |

10 (3.64%) |

2 (0.97%) |

8 (11.76%) |

|

80.89 (p < 0.001) |

14.96 – 437.44 |

| Azathioprine, N (%) |

3 (0.98%) |

1 (0.43%) |

2 (2.78%) |

0.077 |

|

|

| Corticosteroids, N (%) |

17 (5.56%) |

14 (5.98%) |

3 (4.17%) |

0.56 |

|

|

| mTORi, N (%) |

40 (13.07%) |

23 (9.83%) |

17 (23.61%) |

0.002 |

2.84 (p = 0.003) |

1.42 – 5.67 |

| MMF, N (%) |

184 (60.13%) |

132 (56.41%) |

52 (72.22%) |

0.017 |

2.01 (p = 0.018) |

1.13 – 3.58 |

| CNIs, N (%) |

189 (61.76%) |

155 (66.24%) |

34 (47.22%) |

0.004 |

0.46 (p = 0.004) |

0.27 – 0.78 |

Table 7.

ICU admission in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

Table 7.

ICU admission in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19.

|

Table 7.ICU admission in LTR diagnosed with COVID-19

|

Logistic Regression Analysis |

| |

Total (N = 306, 1 lost case) |

Admission to the ICU |

|

|

|

| |

|

No (N = 301) |

Yes (N = 5) |

p-value |

OR (p-value) |

95%CI |

| Age (years), median (IQR) |

61 (54 – 68) |

61 (53 – 68) |

60 (62 – 74) |

0.1 |

|

|

| IMC (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

26.3 (23 – 29) |

26.3 (23 – 29) |

29 (25.5 – 34.4) |

0.21 |

|

|

| Male sex, N (%) |

208 (67.97%) |

203 (67.44%) |

5 (100%) |

0.12 |

|

|

| Female sex, N (%) |

98 (32.03%) |

98 (32.56%) |

0 |

|

|

| Number of vaccines at diagnosis |

3 (0 – 3) |

3 (0 – 3) |

0 (0 – 3) |

0.2 |

|

|

| Vaccination N (%) |

211 (69.18%) |

209 (69.67%) |

2 (40%) |

< 0.001 |

|

|

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

5.87 (3.23 - 9.03) |

5.87 (3.25-9.02) |

4.61 (0.10-9.11) |

0.56 |

|

|

| Time (months) from vaccination to the onset of symptoms, median (IQR) |

94.46 (41.44-185.21) |

95.28 (45.51-185.31) |

46.26 (24.16-137.70) |

0.12 |

|

|

|

Kidney failure (Creatinine≥ 2 mg/dL)

|

23 (7.54%) |

23 (7.67%) |

0 |

0.52 |

|

|

| COPD, N (%) |

13 (4.26%) |

13 (4.33%) |

0 |

0.63 |

|

|

| Asthma, N (%) |

6 (1.97%) |

6 (2.00%) |

0 |

0.75 |

|

|

| HTN, N (%) |

117 (38.36%) |

114 (38%) |

3 (60%) |

0.32 |

|

|

| Cardiovascular events and / or risk factors |

180 (59.21%) |

176 (58.86%) |

4 (80.00%) |

0.34 |

|

|

| T2D, N (%) |

124 (40.66%) |

119 (39.67%) |

5 (100%) |

0.006 |

|

|

| Altered liver enzymes, N (%) |

20 (6.54%) |

19 (6.44%) |

1 (9.09%) |

0.73 |

|

|

| Smokers, N (%) |

50 (16.78%) |

49 (16.72%) |

1 (20%) |

0.94 |

|

|

| Asthenia, N (%) |

98 (32.56%) |

96 (32.43%) |

2 (40%) |

0.72 |

|

|

| Dyspnea, N (%) |

45 (14.95%) |

41 (13.85%) |

4 (80.00%) |

< 0.001 |

21.17 (< 0.001) |

5.47 – 81.85 |

| Fever, N (%) |

77 (25.58%) |

74 (25.00%) |

3 (60.00%) |

0.075 |

4.4 (0.014) |

1.35 – 14.3 |

| Cough, N (%) |

120 (39.87%) |

119 (40.2%) |

1 (20%) |

0.36 |

|

|

| Chest pain, N (%) |

12 (3.99%) |

12 (4.05%) |

0 |

0.65 |

|

|

| Diarrhoea, N (%) |

32 (10.63%) |

31 (10.47%) |

1 (20%) |

0.49 |

|

|

| Anorexia, N (%) |

14 (4.65%) |

14 (4.73%) |

0 |

0.62 |

|

|

|

Chest X-ray findings,N (%)

|

|

|

|

0.008 |

|

|

| Not performed |

191 (69.71%) |

190 (70.63%) |

1 (20%) |

|

|

|

| Normal |

28 (10.22%) |

28 (10.41%) |

0 |

|

|

|

| Bilateral pneumonia |

45 (16.42%) |

42 (15.61%) |

3 (60%) |

|

28.5 (0.002) |

3.34 – 243.27 |

| Lobar pneumonia |

10 (3.65%) |

9 (3.35%) |

1 (20%) |

|

21.11 (0.036) |

1.22 – 365.44) |

| Azathioprine, N (%) |

3 (0.98%) |

2 (0.67%) |

1 (20%) |

< 0.001 |

13.27 (0.041) |

1.12 – 157.67 |

| Corticosteroids, N (%) |

17 (5.57%) |

17 (5.67%) |

0 |

0.58 |

|

|

| mTORi, N (%) |

40 (13.11%) |

40 (13.33%) |

0 |

0.38 |

|

|

| MMF, N (%) |

183 (60%) |

179 (59.67%) |

4 (80%) |

0.36 |

|

|

| CNIs, N (%) |

188 (61.64%) |

186 (62%) |

2 (40%) |

0.32 |

|

|

Table 8.

Multivariate analysis of respiratory failure and hospital admission.

Table 8.

Multivariate analysis of respiratory failure and hospital admission.

| Table 8. Multivariate analysis |

| |

Respiratory failure |

Hospital admission |

| |

Area under ROC curve = 0.851 |

Area under ROC curve = 0.896 |

| |

OR (p-value) |

95%CI |

OR (p-value) |

95%CI |

| Age |

1.056 (0.045) |

1 – 1.1 |

|

|

| Vaccination |

0.16 (< 0.001) |

0.072 – 0.37 |

0.2 (< 0.001) |

0.09 – 0.44 |

| Kidney injury |

5.33 (0.006) |

1.62 – 17.52 |

4.29 (0.013) |

1.35 – 13.58 |

| HTN |

3.69 (0.002) |

1.61 – 8.45 |

3.25 (0.002) |

1.54 – 6.89 |

| Dyspnea at diagnosis |

|

|

18.83 (< 0.001) |

7.61 – 46.56 |

| Fever at diagnosis |

|

|

4.08 (< 0.001) |

1.9 – 8.74 |

| mTORi |

|

|

2.8 (0.036) |

1.07 – 7.32 |

| MMF |

2.73 (0.008) |

1.49 – 14.71 |

|

|

Table 9.

Death from COVID-19.

Table 9.

Death from COVID-19.

| Table 9. Death from COVID-19 |

| |

Death due to COVID-19 |

|

Univariant survival analysis |

| |

Total (N=307) |

No (N = 295) |

Yes (N = 12) |

p-value |

Hazard ratio (p-value) |

95% CI |

| Age (years), median (IQR) |

61 (54.00-68.00) |

61(53-68) |

68 (61.5-71.5) |

0.034 |

|

|

| Age (years), mean (SD) |

59.03 (14.03) |

58.72 (14.16) |

66.50 (7.24) |

0.06 |

|

|

| IMC (kg/m2), median (IQR) |

26.30 (23 – 29) |

26.10(22.9 - 29) |

29.05 (26.8 - 35.25) |

0.008 |

|

|

| IMC (kg/m2), mean (SD) |

26.35 (4.68) |

26.17 (4.56) |

30.54 (5.59) |

0.001 |

|

|

| Obesity, N (%) |

62 (20.67%) |

56 (19.44%) |

6 (50.00%) |

0.01 |

3.94 (0.002) |

1.27 - 12.22 |

| Male sex, N (%) |

209 (68.08%) |

199 (67.46%) |

10 (83.33%) |

0.25 |

|

|

| Doses of vaccination at diagnosis |

3 (0 – 3) |

3 (0 – 3) |

0 (0 – 1.5) |

0.002 |

0.56 (0.006) |

0.32 - 0.83 |

| Vaccine (doses) |

|

|

|

0.062 |

|

|

| 0 |

93 (30.39%) |

85 (28.91%) |

8 (66.67%) |

|

|

|

| 1 |

16 (5.23%) |

15 (5.1%) |

1 (8.33%) |

|

|

|

| 2 |

38 (12.42%) |

36 (12.24%) |

2 (16.67%) |

|

|

|

| 3 |

92 (30.07%) |

91 (30.95%) |

1 (8.33%) |

|

|

|

| 4 |

54 (17.65%) |

54 (18.37%) |

0 |

|

|

|

| 5 |

13 (4.25%) |

13 (4.42%) |

0 |

|

|

|

|

Kidney injury (creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL) |

23 (7.52%) |

19 (6.46%) |

4 (33.33%) |

<0.001 |

6.9 (0.002) |

2.08 - 23.02 |

| COPD, N (%) |

13 (4.25%) |

11 (3.74%) |

2 (16.67%) |

0.030 |

4.64 (0.047) |

1.02 - 21.22 |

| Asthma, N (%) |

6 (1.96%) |

6 (2.04%) |

0 (0.00%) |

0.62 |

|

|

| HTN, N (%) |

117 (38.24%) |

109 (37.07%) |

8 (66.67%) |

0.039 |

|

|

| Cardiovascular events and / or risk factors |

181 (59.34%) |

170 (58.02%) |

11 (91.67%) |

0.020 |

|

|

| T2D, N (%) |

125 (40.85%) |

115 (39.12%) |

10 (83.33%) |

0.002 |

7.39 (0.01) |

1.62 - 33.76 |

| Altered liver enzymes, N (%) |

20 (6.54%) |

19 (6.46%) |

1 (8.33%) |

0.80 |

|

|

| Smokers |

50 (16.72%) |

48 (16.72%) |

2 (16.67%) |

0.14 |

|

|

| Azathioprine, N (%) |

3 (0.98%) |

3 (1.02%) |

0 |

0.73 |

|

|

| Corticosteroids, N (%) |

17 (5.56%) |

16 (5.44%) |

1 (8.33%) |

0.67 |

|

|

| mTORi, N (%) |

40 (13.07%) |

39 (13.27%) |

1 (8.33%) |

0.62 |

|

|

| MMF, N (%) |

184 (60.13%) |

172 (58.5%) |

12 (100%) |

0.004 |

|

|

| CNIs, N (%) |

189 (61.76%) |

187 (63.61%) |

2 (16.67%) |

0.001 |

0.12 (0.006) |

0.026 - 0.55 |

| Period |

|

|

|

<0.001 |

|

|

| 1th wave |

24 (7.82%) |

23 (7.80%) |

1 (8.33%) |

|

|

|

| 2nd wave |

40 (13.03%) |

36 (12.20%) |

4 (33.33%) |

|

|

|

| 3rd wave |

21 (6.84%) |

20 (6.78%) |

1 (8.33%) |

|

|

|

| 4th wave |

14 (4.56%) |

11 (3.73%) |

3 (25.00%) |

|

|

|

| 5th wave |

10 (3.26%) |

8 (2.71%) |

2 (16.67%) |

|

|

|

| 6th wave |

63 (20.52%) |

62 (21.02%) |

1 (8.33%) |

|

|

|

| 7th wave |

135 (43.97%) |

135 (45.76%) |

0 (0.00%) |

|

|

|

7.1. Respiratory failure

Patients with respiratory failure were significantly older, with a median age of 68 years (59 – 73) and had a higher median BMI, of 28 (IQR 25.5 – 29.7), with an obesity rate of 50% (N = 6). HTN (67.65%, N = 23), a history of cardiovascular events or risk factors (85.29%, N = 29) and D2T (67.65%, N = 23) were more frequent. The number of vaccinations was lower in this group with a median of 0 doses (IQR 0 – 2). In 22 cases, patients (64.70%) had not received any dose of the vaccine.

30 patients (88.24%) were on MMF and only 12 (35.29%) were on CNIs.

Univariate regression logistic analysis revealed that older age (OR = 1.05, 95%CI: 1.02 - 1.09), BMI (OR = 1.09, 95%CI 1.017 - 1.18), creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL (OR = 4.12, 95%CI: 1.57 - 10.97), a history of cardiovascular events or risk factors (OR = 4.54, 95%CI: 1.7 - 12), T2D (OR = 3.48, 95%CI: 1.63 - 7.45), MMF (OR = 5.74, 95%CI: 1.97 - 16.76), bilateral pneumonia (OR = 112.5, 95%CI: 24.87 – 508.84) or lobar pneumonia (OR = 63, 95%CI 9.59 – 413.67) were risk factors for developing respiratory failure. Female sex (OR = 0.33, 95%CI: 0.12 – 0.89), CNIs (OR = 0.29, 95%CI: 0.14 - 0.62) and vaccination were protective factors (OR = 0.7, 95%CI: 0.54 – 0.92), as well as the months from vaccination to the onset of symptoms (OR = 0.7, 95%CI: 0.54 – 0.92).

7.2. Invasive mechanical ventilation

100% of patients that needed IMV (N = 5) had a history of D2T and 20% (N = 1) were on AZT. Univariate regression logistic analysis showed that dyspnea (OR = 24.87, 95%CI: 2.71 – 228.14), AZT (OR = 37.35, 95%CI: 2.77 - 499.16), bilateral pneumonia (OR = 13.57, 95%CI: 1.37 – 133.71) and lobar pneumonia (OR = 37.25, 95%CI: 2.78 – 499.16) were risk factors for requiring IMV.

7.3. Hospital admission

Patients requiring hospital admission were significantly older, with a median age of 64.5 years (IQR 56 – 71.5), and a higher median BMI of 27.32 (IQR 24 – 29.7). The median length of hospital stay was 18 days (IQR 13 – 26). Significantly more frequent comorbidities in this group were kidney disease with creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL (15.28%, N = 11), COPD (8.45%, N = 6), HTN (54.93%, N = 39), T2D (56.34%, N = 40) and a history of cardiovascular events or risk factors (76.06%, N = 54).

23.61% (N = 17) were on mTORi and 47.22% (N = 34) were on CNI.

The number of vaccinations was lower with a median of 0 doses (IQR 0 – 3). 54.17% of patients that were hospitalized (N = 39) had not received any dose of the vaccine. Univariate regression logistic analysis showed that vaccination was a protective factor for hospital admission (OR 0.23, 95%CI: 0.15 – 0.46).

Risk factors for hospital admission were age (OR = 1.04, 95%CI: 1.01 – 1.07), BMI (OR = 1.08, 95%CI: 1.02 – 1.15), creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL (OR = 3.33, 95%CI 1.4 – 7.93), HTN (OR = 2.45, 95%CI 1.43 – 4.21), a history of cardiovascular events or risk factors (OR = 2.67, 95%CI: 1.46 – 4.89), T2D (OR = 2.28, 95%CI: 1.33 – 3.9). mTORi and MMF were risks factors for admission (OR = 2.84, 95%CI: 1.42 – 5.67 and OR = 2.01, 95%CI 1.13 – 3.58, respectively) while CNI was a protective factor (OR = 0.46, 95%CI: 0.27 - 0.78).

7.4. Admission to the ICU

The 5 patients admitted to the ICU were male and one of them (20%) was in AZT, which resulted a risk factor of admission to the ICU in the univariable regression logistic analysis (OR = 13.27, 95%CI: 1.12 – 157.67). Dyspnea and fever were the only symptoms related to ICU admission (OR = 21.17, 95%CI: 5.47 – 81.85 and OR = 4.4, 95%CI 1.35 – 14.3), as were the radiological findings of bilateral pneumonia (OR = 28.5, 95%CI 3.34 – 243.27) and lobar pneumonia (OR = 21.11, 95%CI 1.22 – 365.44).

7.5. Multivariate analysis of respiratory failure and hospital admission

Multiple models were evaluated to carry out a multivariate analysis considering risk factors described in the univariate analysis. Results are shown in

Table 8.

For respiratory failure (N = 34), the model with the largest area under the ROC curve (0.851) included: age (OR = 1.06, 95%CI: 1 – 1.1), HTN (OR = 3.69, 95%CI: 1.61 – 8.45), creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL (OR = 5.54, 95%CI: 1.62 – 17.52), immunosuppression with MMF (OR = 2.73, 95%CI: 1.93 – 14.71) and vaccination (OR = 0.16, 95%CI 0.072 – 0.37).

For hospital admission (n = 72) the model with the largest area under the ROC curve (0.896) included: creatinine ≥ 2 mg/dL (OR = 4.29, 95%CI 1.35 – 13.58), HTN (OR = 3.25, 95%CI: 1.54 – 6.89), dyspnea (OR = 18.83, 95%CI: 7.61 – 46.56), fever (OR = 2.8, 95%CI: 1.9 – 8.74), immunosuppression with mTOR inhibitors (OR = 2.8, 95%CI: 1.07 – 7.32) and vaccination (OR 0.2, 95%CI 0.09 – 0.44).

7. Discussion

Repercussions of the pandemic on liver transplant activity. The COVID-19 pandemic has repercussed on liver transplantation activity with a decrease in the number of organ donors and even in the temporary suspension of the activity in several centers [

3,

4]. A study which analyzed the data base from the Global Observatory for Organ Donation and Transplantation between 2019 and 2020 observed a global decrease of 17.5% in the number of donors, with a 11.3% decrease in liver transplants [

27]. In an observational study which analyzed the transplant activity over 22 countries during the same period showed a global decrease of 16% [

5]; more notable during the first months of the pandemic.

Inayat F et al. [

28] studied retrospectively a cohort of over 15,000 liver transplant patients hospitalized between 2019 and 2020. They found that the COVID-19pandemic did not translate into an increase in the risk of hospitalization in these patients. It did however show to have an effect in the increased in intrahospital mortality and in organ rejection among the patients hospitalized during said period.

In Spain a study was conducted on organ donation among patients with a positive CRP for SARS-CoV-2 in 69 organ receptors with negative CRPs. The CRP resulted positive in 4 of the receptors (5.8%) with 20 days of transplantation without it being able to be attributed to the transplant. Noe among the 18 receptors of a liver transplant suffered mayor complications that could be linked to infection in the donor [

29]. Another multicentric study evaluated viral RNA in the liver biopsy of 10 grafts, with negative results in all of them [

30].

Characteristics of the transplanted patients. Kulkarni et al. conducted in 2021 the only meta-analysis published to date [

1], including 18 observational studies with a total of 1522 patients. According to this study, the most common etiologies for transplant were viral (38%), alcohol (22.23%), NASH (2.5%), autoimmune (7.4%) and hepatocarcinoma (5.26%). In our study viral liver disease, alcoholic liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma were the primordial reasons for transplantation. The comorbidities more frequently registered were hypertension (44.3%), diabetes (39.4%), cardiovascular disease (16.43%), renal failure (13,7%), pulmonary disease (9%) and obesity (23.6%) [

9]. In our study the frequency of diabetes mellitus, hypertension and obesity is similar, with a frequency of 41.07%, 38.93%v and 20.73%, respectively. The frequency of pulmonary disease (COPD or bronchial asthma) is 6.78%, while the frequency of cardiovascular events or a combination of multiple cardiovascular risk factors goes up to 61.29%.

COVID-19 in orthotopic liver transplant. It was during the first wave of the disease that large series of cases of adult liver transplant patients infected with COVID-19 were published contributing greatly to the current knowledge of the particularities of the disease in this subgroup of patients. [

8,

19,

20,

31,

32,

33].

The most common symptoms described in LT are fever (49.7%), cough (43.79%) and dyspnea (29.7%); with a 27.26% of gastrointestinal symptoms [

9], myalgia or asthenia (36.66%), anosmia (36.66%) or dysgeusia (33.33%) [

7].

In our cohort, the predominant symptoms have not been severe, cough, asthenia and myalgias encompassing the majority. Gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting and diarrhea) were only alluded to by 14.9% of patients. Among our patients 25.5% referred fever and 14.9% dyspnea with an observed progressive decrease of this latter symptom in the subsequent waves. Presenting at the time of diagnosis with asthenia, dyspnea, fever or anorexia has proven to be a risk factor for developing respiratory insufficiency in this study, being dyspnea the only symptom that proved to be a risk factor for the need of mechanical ventilation. The presence of fever and dyspnea were the only symptoms at the time of diagnosis that resulted in a higher risk of requiring intensive care.

The median time between receiving the transplant and COVID-19 diagnosis is variable, from 5.7 to 13.1 years [

7,

9,

34]. Guarino M et al. observed it was significantly shorter in patients with asymptomatic COVID-19 [

2]. These, however, did not show any differences in regard to comorbidities or immunosuppressive treatment. In a 16-patient series Eren-Kutsoylu et al. [

34] found a correlation between respiratory symptoms or fever and the need for hospitalization. In this series, 14 patients remained asymptomatic (46.67%), in contrast with the series by Colmenero et al., with 7/111 asymptomatic patients (6.3%) [

8]. In this study we find 19.87% of asymptomatic patients, with a variable frequency among different waves, higher in the third and sixth (25.81% - 33.33%) versus the first and second (16.67% - 19.87%), and the last one (14.50%).

Kulkarni et al describe a 72% rate of admissions, higher than in non-transplanted patients and three times higher than the one observed in our study; and a cumulative incidence of intensive care unit admissions of 16%, compared to the 3.9% in our study [

9].

A mean hospital stay In LT between 8-11 days was reported [

7,

32,

35] similar to the non- transplanted controls [

35], and shorter to that found in our study which was 18 days. The incidence of invasive mechanical ventilation described in the above-mentioned meta-analysis was 21.1%, again higher in LT than in the non-transplanted controls [

9]. In our study only 5 patients (1.63%) required intubation.

The lower rate of severe COVID-19 in this study is justified by the inclusion in the same of a higher number of patients towards the end of the pandemic. As can be observed in

Table 10, the rate of severe COVID-19 decreases towards the sixth and seventh waves, at which time over 60% of the cases were diagnosed. It draws attention however that the rate of Intensive care unit admissions and need for mechanical ventilation have shown no statistically significant differences during these periods.

In regard to thrombotic complications, the incidence among transplanted patients lies around 6% [

9]. Mansoor et al [

20] found no differences when comparing them to the thrombotic rate of the general public.

The median age at the time of diagnosis is lower (59.55 years) in transplanted patients compared to their controls (63.2 years). The median age at the time of diagnosis was similar in our study; 61 years. Colmenero et al. and Belli et al. Describe that patients with less severe symptoms form COVID-19 were younger, had fewer comorbidities and received more frequently immunosuppressive therapy with tacrolimus [

8,

19]. When compared to the general public, the course of the disease hasn’t shown more severity in LT patients [

7,

32].

In this cohort, the median age and BMI were significantly higher in patients who suffered respiratory insufficiency or required a longer hospital stay. In the logistic regression analysis, older patients, high BMI, renal failure with creatinine

over 2 mg/dL, history of cardiovascular events or risk factors, HTN, and T2D have been shown to be risk factors for respiratory insufficiency or hospital admission while female sex proved to be a protective factor.

History of COPD was a risk factor for hospital admission, as well as mTORi immunosuppressive therapy, while the number of vaccinations before diagnosis proved to be a protective factor for hospital admission and development of respiratory insufficiency.

Time between vaccination and the start of symptoms was significantly shorter in patients who later developed respiratory insufficiency, but no significant differences were observed for hospital admission, admission in the ICU or need for intubation.

Altered x-rays were observed to be a significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 (Hospital admission, intensive care unit admission, respiratory insufficiency or need for mechanical ventilation).

COVID-19 related mortality in orthotopic liver transplant. The factors related to death from COVID-19 have been exhaustively studied. The results in mortality in LT are heterogenous in the published series [

9], with a 16.5% incidence and similar when compared to non-transplanted patients. Webb et al, in a multicentric study with 151 LT among 18 countries described a significantly lower mortality rate in LT (19% versus 27% in non-LT; p = 0.046). The main causes of death described are COVID-19 related complications (62.54%) and respiratory failure (29.88%) [

8,

9,

19].

Increased levels of transaminases during COVID-19 infection have been documented [

9]. Rabiee et al. described the association between changes in hepatic biochemistry and increase in mortality in a series of 112 LT patients [

33]. Despite this no differences were apparent in this study when analyzing alterations y hepatic biochemistry and death by COVID-19.

Concerning acute renal failure, a 33.22% incidence was reported in LT patients with COVID-19 [

9], considering the increase in basal serum creatinine concentration a risk factor for severe COVID-19 and mortality [

31,

36].

Other contributing factors to COVID-19 mortality are the presence of malignant extrahepatic neoplasia [

31], advanced age [

8,

19,

31], dyspnea at the time of diagnosis [

8], male sex, D- dimer or ferritin levels elevation and lymphopenia [

8,

32,

37].

In our study, the variable related to death by COVID-19 were obesity, renal failure, COPD, and DM2 while vaccination and immunosuppressive therapy with CNIs were protective factors.

Immunosuppression. Immunosuppression schemes in previously published studies are based in CNIs, cyclosporine, MMF or mTORi in monotherapy or in combination. [

8,

9,

19,

31,

32]. Colmenero et al. showed the prejudicial and dose-dependent effect of MMF immunosuppression [

8] possibly in relation to a synergic mechanism in cytotoxicity on CD8+ with the COVID-19 virus. They didn’t find worse results in terms of severity in immunosuppressed patients with CNIs or mTORi. Belli et al did prove an association between CNIs and reduced mortality which could be related to an inhibitory mechanism of viral replication [

19]. mTOR inhibitors, AZT, and MMF can induce cytopenia which could worsen the course of infection since lymphopenia isa parameter associated with severe COVID-19 [

38,

39].

A change in immunosuppressive therapy has not shown to have an impact on mortality [

19,

31,

34,

37,

40].

The consensus among the AASLD and the EASL is an individualized evaluation of each case of COVID-19 infection, preferably reducing the dosage of mycophenolate in patients in higher risk of developing severe forms of the disease [

41,

42].

Vaccination against COVID-19. LTR have shown a lower prevalence of anti-SARS-CoV-2 antibodies long term when compared to the general public, with higher levels of antibodies in vaccinated patients [

43,

44,

45] and in patients with a longer period between receiving the transplant and being infected by COVID-19 [

43].

Currently, 12 vaccinations comprise the Emergency Use Listing of the WHO, including inactivated viral vaccines, protein-based and DNA or RNA viral vector- based vaccines [

46,

47]. The development and prompt distribution of the different vaccines has meant a change in the course of the COVID-19 disease, protecting against more severe forms and death. In LTR it has proved to reduce the rate of infection, symptomatic disease [

48], hospitalization [

49], need for intensive care and mechanical ventilation [

13] and mortality, particularly in patients with a complete course [

13,

48,

49]. The associations for the study of liver disease recommend a complete vaccination, as well as a booster dose to achieve or maintain immunity in LTR [

50,

51]. This subgroup reaches a lower immunological response than the general public, due to immunosuppressive therapy -particularly with MMF-, achieving a higher seroconversion dose in dose patients with repeated doses [

44,

52,

53,

54]. Long term LT patients show a better immunological response than recent recipients [

55].

This study shows a lower prevalence of severe COVID-19 in vaccinated patients, with a higher number of doses in those patients who did not present with complications.

Treatment for COVID-19 infection in LT patients. Together with general measures such as hand washing, use of facemasks and social distancing, multiple drugs have been evaluated as potential treatments for COVID-19, including

hydroxychloroquine, antibiotics, antivirals, steroids, immunomodulators, anticoagulants or plasma [

9].

Antimalarials such as hydroxychloroquine were considered during the first stages of the pandemic for their immunomodulator and antiviral effects, but their efficacy hasn’t been clearly proven [

17,

56]. Remdervir, a SARS-CoV-2 RNA polimerase inhibitor has been widely used since it is a medication with an acceptable safety level, but it has not shown strong benefits in patients with a solid organ transplant [

57,

58] which induce the WHO to discontinue its use in hospitalized patients [

57]. Nonetheless, it´s still recommended for outpatient treatment in those with high risk of hospitalization [

59]. Favipiravir [

60] and Lopinavir/Ritonavir which showed in vitro activity against SARS-CoV-2 [

56,

61] were discouraged. Dexamethasone has proved to reduce mortality in those who require mechanical ventilation [

62]. Tocilizumab, an IL-6 receptor inhibitor, is considered a safe medication in transplanted patients, even though it must be used carefully owing to its hepatotoxicity [

56,

61]. Other monoclonal antibodies such as bamlanivimab, casirivimab and imdevimab have proven to reduce viral load in patients with non-severe COVID-19 [

57].

In our study we observed that antimalarials, interferon and kaletra were used during the first period in selected cases. When bacterial superinfection was suspected empiric antibiotics were prescribed and later adjusted to antibiogram. Prophylactic anticoagulation was prescribed in 50% of the patients up to the fifth wave, with a decrease in the last to waves, following the same tendency as corticoid treatment.

Tocilizumab and remdesivir were used in 2.61% (N = 8) and 8.79% (N = 27) of the patients respectively. The use of Paxlovid requires careful monitorization in immunosuppressive therapy therefore its use is limited transplant patients [

63]. In our study, it has been only used in 1.02 % of patients (N = 3).