Submitted:

23 January 2025

Posted:

23 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Analytical Instrumentation

2.3. Theory/Computations

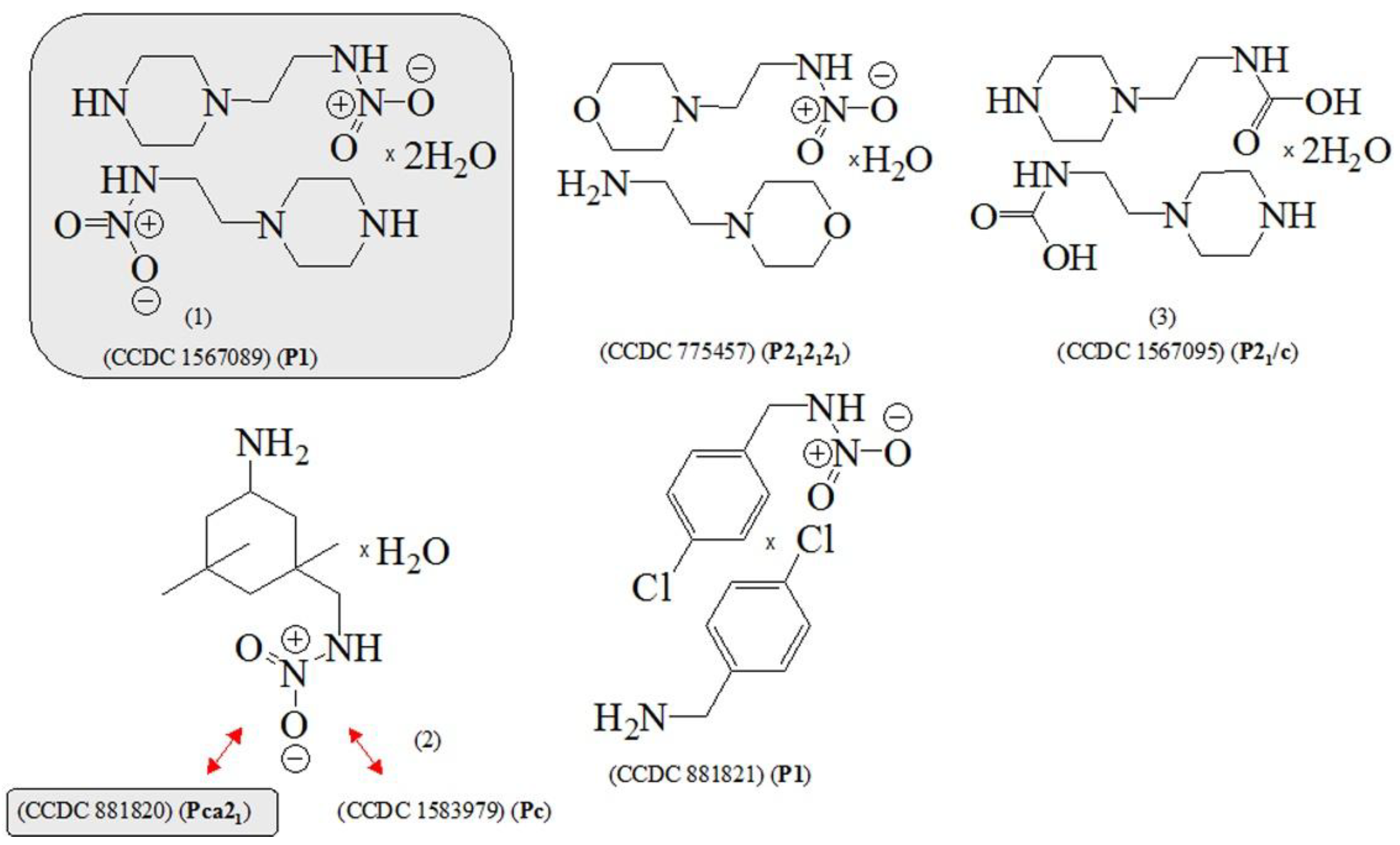

| Compound | (1) | (2) | |||

| CCDC | 1567089 | (s.i.) | 1583979 | 881820 | 1583979 |

| Polymorph I | Polymorph II | ||||

| Ref. | This study | This study | [54,55] | [55,56] | [59,60] |

| Empirical formula | C6H15N4O3 | C6H15N4O3 | C11H22N3O3 | C11H22N3O3 | C20H34N6O6 |

| Moiety formula | C6H15N4O3 | C6H15N4O3 | C11H22N3O3 | C11H22N3O3 | C20H34N6O6 |

| Formula mass | 191.22 | 191.22 | 244.32 | 244.32 | 454.53 |

| Crystal system | Triclinic | Triclinic | Monoclinic | Orthorhombic | Orthorhombic |

| Space Group | P-1 | P1 | Pc | Pca21 | Pca21 |

| a [Å] | 9.646(2) | 9.646(2) | 7.9820(18) | 10.9481(15) | 10.951(2) |

| b [Å] | 10.321(2) | 9.646(2) | 14.438(3) | 14.463(3) | 28.852(6) |

| c [Å] | 11.047(3) | 10.321(2) | 10.9433(19) | 8.0063(12) | 7.9923(18) |

[o] [o] |

108.944(6) | 11.047(3) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

[o] [o] |

95.120(7) | 108.944(6) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

[o] [o] |

105.960(6) | 105.960(6) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V [Å3] | 980.7(4) | 790.6(3) | 1261.1(5) | 1267.8(3) | 2525.2(9) |

| Z | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

[g.cm-1] [g.cm-1] |

1.282 | 1.190 | 1.287 | 1.217 | 1.196 |

| F000 | 408 | 378 | 532 | 508 | 976 |

(Mo-K) [mm-1] (Mo-K) [mm-1] |

0.100 | 0.095 | 0.094 | 0.090 | 0.089 |

| T [K] | 293(2) | 199(2) | 199(2) | 198(2) | 199(2) |

range range |

2.59–25.07 | 2.59–25.07 | 2.55–24.76 | 2.33–25.04 | 2.33–25.04 |

| Refl. collected | 3395 | 9254 | 7635 | 7565 | 4281 |

| Unique refl. | 2602 | 6569 | 3544 | 2223 | 3415 |

| R1[2σ(I)] | 0.1127 | 0.1060 | 0.0515 | 0.0617 | 0.1224 |

| R1 (all data) | 0.3194 | 0.3313 | 0.1254 | 0.1548 | 0.3277 |

| wR2 | 0.1305 | 0.1306 | 0.0699 | 0.0804 | 0.1659 |

| GooF | 2.151 | 1.274 | 1.139 | 0.985 | 1.479 |

| Diff. peak/ hole [e/Å3] | 0.854/-0.574 | 0.898/-0.590 | 0.222/-0.358 | 0.278/-0.398 | 1.517/-0.885 |

3. Results

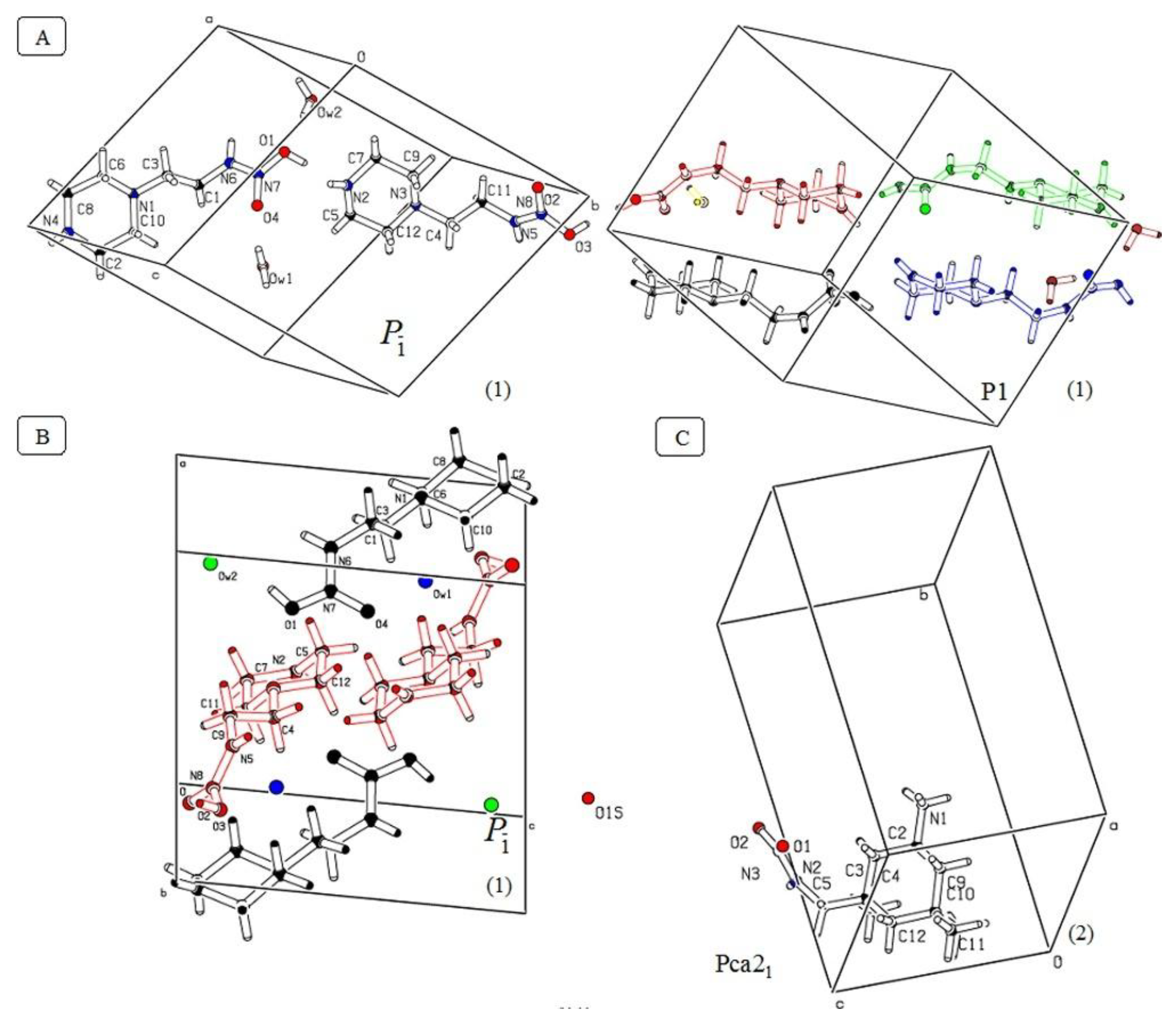

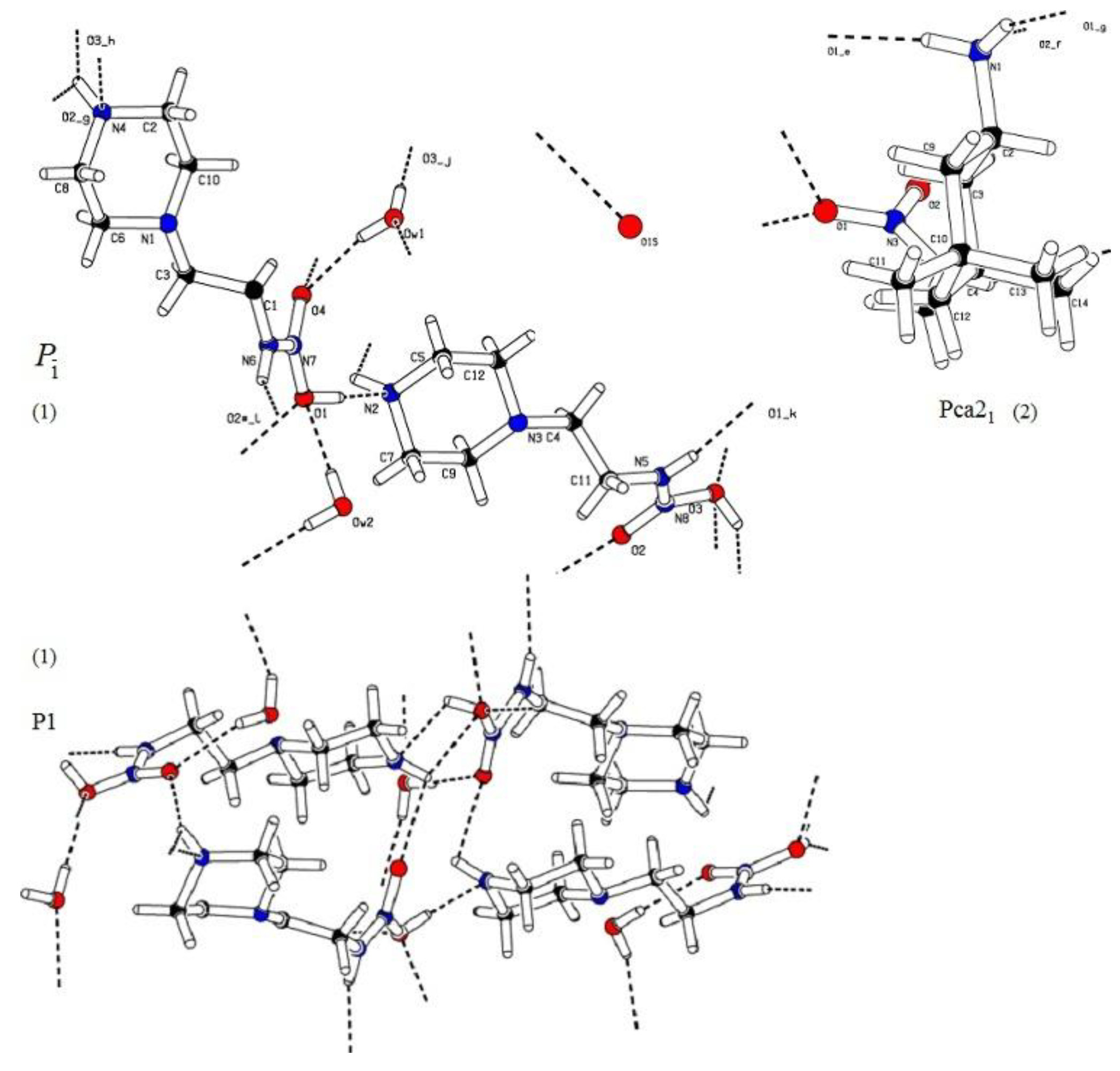

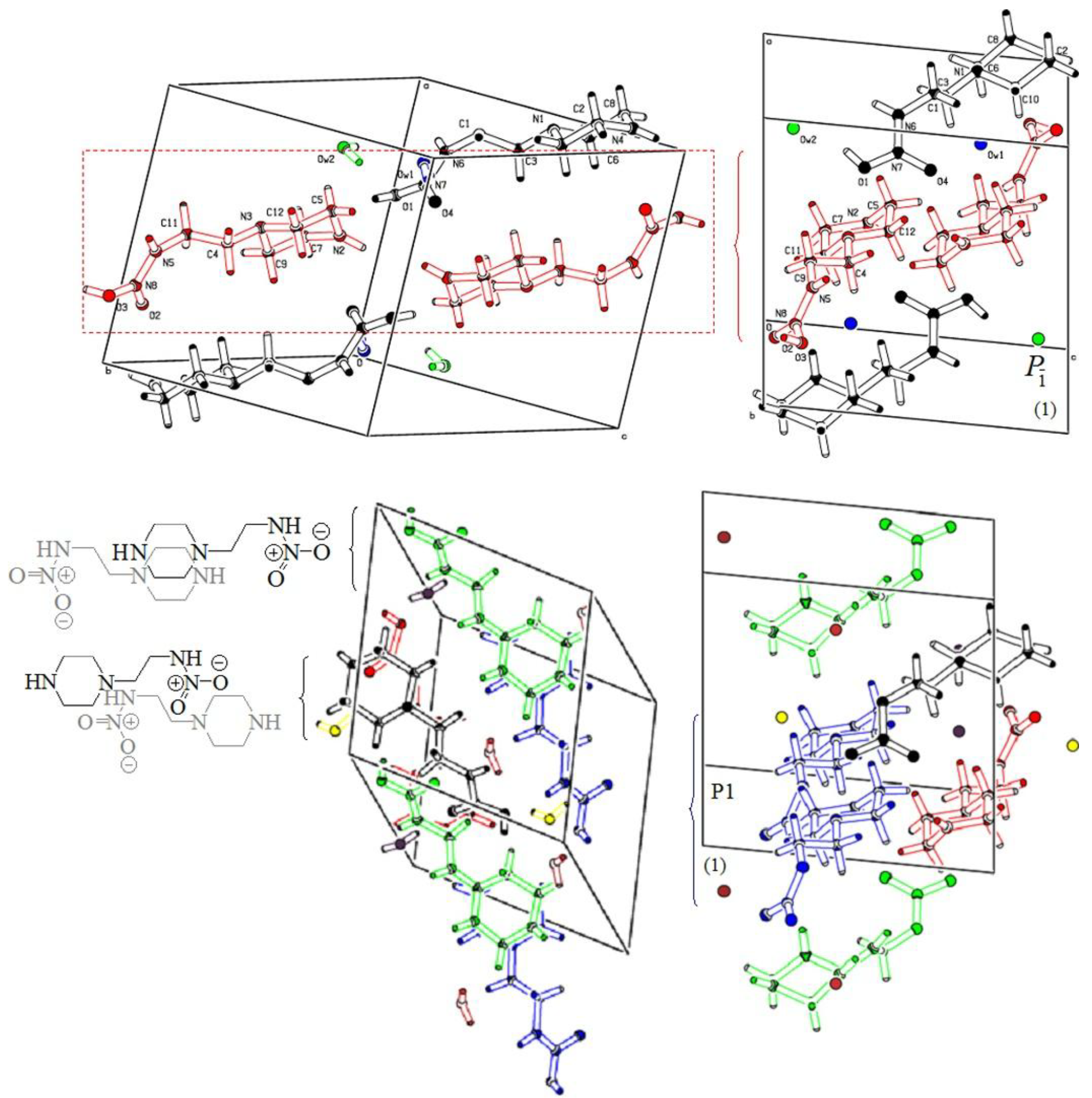

3.1. Crystallographic Data

3.2. Electronic Transmission Spectra

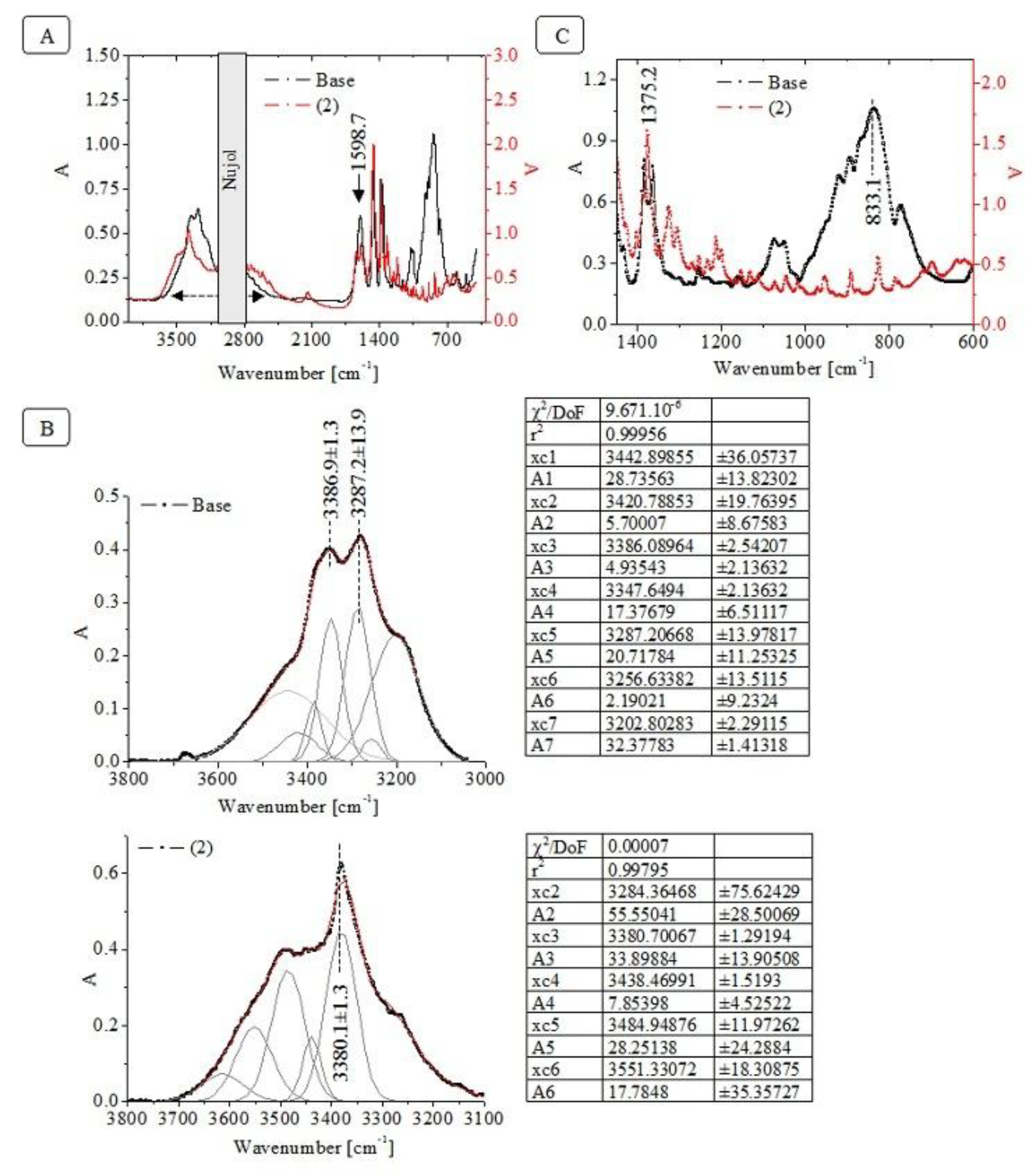

3.3. Vibration Spectroscopic Data

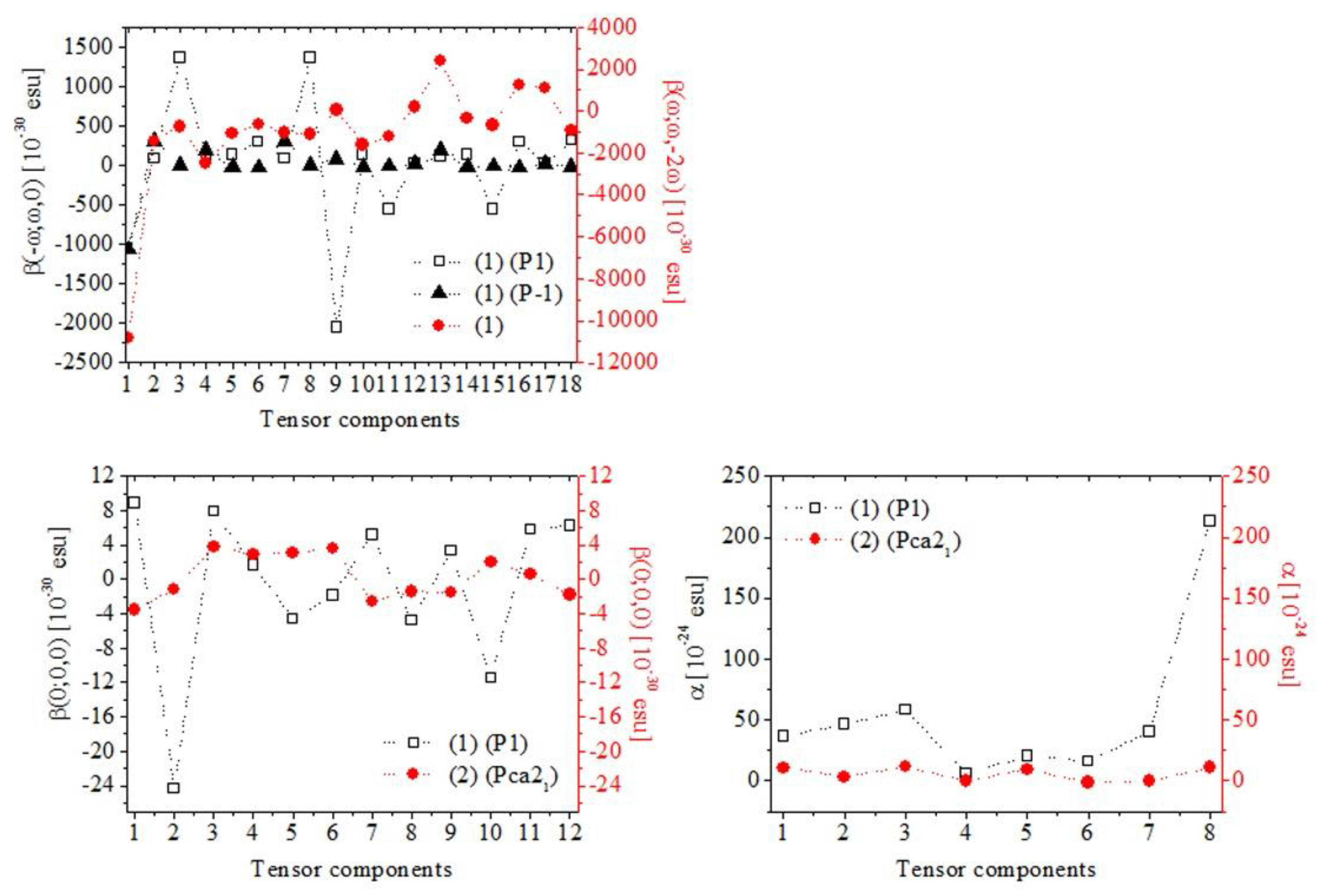

3.4. Theoretical Data

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vermeulen, N.; Espinosa, D.; Ball, A.; Ballato, J.; Boucaud, P.; Boudebs, G.; Campos, C.; Dragic, P.; Gomes, A.; Huttunen, M.; Kinsey, N.; Mildren, R.; Neshev, D.; Padilha, L.; Pu, M.; Secondo, R.; Tokunaga, E.; Turchinovich, D.; Yan, J.; Yvind, K.; Dolgaleva, K.; Van Stryland, E. Post-2000 nonlinear optical materials and measurements: data tables and best practices. J. Phys. Photonics 2023, 5, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annadhasan, M.; Basak, S.; Chandrasekhar, N.; Chandrasekar, R. Next-generation organic photonics: The emergence of flexible crystal optical waveguides. Adv. Optical Mater. 2020, 8, 2000959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Kumar, A.; Chandrasekar, R.; Takamizawa, S. Spatially controllable and mechanically switchable isomorphous organoferroeleastic crystal optical waveguides and networks. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 74781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalton, L.; Guenter, P.; Jazbinsek, M.; Kwon, O.; Sullivan, P. Organic Electro-Optics and Photonics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Kim, J.; Khoury, R.; Saghayezhian, M.; Haber, L.; Plummer, E. Surface sum frequency generation spectroscopy on non-centrosymmetric crystal GaAs (001). Surface Sci. 2017, 664, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinman, D. Theory of second harmonic generation of light. Phys. Rev. 1962, 128, 1761–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, P.; Hill, A.; Peters, C.; Weinreich, G. Generation of optical harmonics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1961, 7, 118–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Shao, D.; Gan, W.; Wang, H.; Han, H.; Sheng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, H. Classification of second harmonic generation effect in magnetically ordered materials. npj Quantum Mater. 2023, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Bruch, A.; Lu, J.; Gong, Z.; Surya, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Yan, J.; Tang, H. Beyond 100 THz-spanning ultraviolet frequency combs in a non-centrosymmetric crystalline waveguide. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ye, Z.; Suzuki, R.; Ye, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Iwasa, Y.; Zhang, X. Atomically phase-matched second-harmonic generation in a 2D crystal. Light: Sci. Appl. 2016, 5, e16131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, K.; Dutta, S.; Munshi, P. Concomitance, reversibility, and switching ability of centrosymmetric and non-centrosymmetric crystal forms: Polymorphism in an organic nonlinear optical material. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 1126–1135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, A.; Wang, P.; Wang, X.; Lei, X.; Bian, Q.; Li, S.; Yuan, B.; Gao, J.; Li, F.; Pan, M.; Liu, F. Large-scale 2D heterostructures from hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks and graphene with distinct Dirac and flat bands. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 5934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiebig, M.; Pavlov, V.; Pisarev, R. Second-harmonic generation as a tool for studying electronic and magnetic structures of crystals: review. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 2005, 22, 96–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, S.; Paiva, S.; Fritz, R.; Herrera, F.; Colón, Y. First-principles screening of metal-organic frameworks for entangled photon pair generation. Mater. Quantum Technol. 2024, 4, 015404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B. Crystallographic and optical spectroscopic study of metal-organic 2D polymeric crystals of silver(I)– and zinc(II)-squarates. Crystals 2024, 14, 905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagadevan, S. A simple theoretical approach to analyze the second harmonicgeneration of single crystals. Optik 2015, 126, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Rasskazov, I.; Carney, P. Clausius–Mossotti relation revisited: Media with electric and magnetic response. Optics Commun. 2023, 549, 129844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renugadevi, S.; Vijayaraghavan, G.; Mohaideen, H.; Balu, R. Optical and structural characterization of chemical components of Calotropis procera on semi-organic single crystal. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 35, 1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maschio, L.; Rérat, M.; Kirtman, B.; Dovesi, R. Calculation of the dynamic first electronic hyperpolarizability β(−ωσ; ω1, ω2) of periodic systems. Theory, validation, and application to multi-layer MoS2. J. Chem. Phys. 2015, 143, 244102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Pandey, R.; Karna, S. Enhanced nonlinear optical response of graphene-based nanoflake van der Waals heterostructures. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 5590–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rerat, M.; Maschio, L.; Kirtman, B.; Civalleri, B.; Dovesi, R. Computation of second harmonic generation for crystalline urea and KDP. An ab initio approach through the coupled perturbed Hartree-Fock/Kohn-Sham scheme. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016, 12, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; De Kee, D. The frequency dependence of nonlinear optical processes. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 104, 9876–9887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.; De Kee, D. The frequency dependence of hyperpolarizabilities for noncentrosymmetric molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 1996, 105, 8247–8249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Shao, D.; Gan, W.; Wang, H.; Han, H.; Sheng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, H.; Li, H. Classification of second harmonic generation effect in magnetically ordered materials. npj Quantum Mater. 2023, 8, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrero, M.; Rérat, M.; Kirtman, B.; Dovesi, R. Calculation of first and second static hyperpolarizabilities of one- to three-dimensional periodic compounds. Implementation in the CRYSTAL code. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 129, 244110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B. Comment on “Comment on “Crystallographic and theoretical study of the atypical distorted octahedral geometry of the metal chromophore of zinc(II) bis((1R,2R)-1,2-diaminocyclohexane) dinitrate””. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1287, 135746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalla, V.; Medishetty, R.; Wang, Y.; Bai, Z.; Sun, H.; Weid, J.; Vittal, J. Second harmonic generation from the ‘centrosymmetric’ Crystals. IUCrJ 2015, 2, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, R. Centrosymmetric or noncentrosymmetric? Acta Cryst. 1986, B42, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, R. The centrosymmetric-noncentrosymmetric ambiguity: some more examples. Acta Cryst. 1994, A50, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, J.; Kurtz, S. A second harmonic analyzer for the detection of non-centrosymmetry. J. Appl. Cryst. 1976, 9, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, R. P1 or P-1? Or something else? Acta Cryst. 1999, B55, 931–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskii, A.; Bohaty, L.; Becker, P.; Eichler, H.; Rhee, H.; Maczka, M.; Hanuza, J. Monoclinic ethylenediamine (+)-tartrate (NH3CH2CH2NH3)((+)-C4H4O6) (EDT) – a new organic non-centrosymmetric crystal for Raman laser converters with large (3000 cm-1) frequency shifts. Laser Phys. Lett. 2007, 4, 291–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomono, T. Potential of P1 organic crystal for compact SHG green laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2015, 68, 2015–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, M.; Valverde, C. Synthesis, crystal structure, spectroscopic and nonlinear optical properties of organic salt: A combined experimental and theoretical study. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1210, 128039. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, H.; Hu, W. Organic semiconductor single crystals for electronics and photonics. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1801048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Zhuo, M.; Wang, X.; Liao, L. Two-dimensional organic semiconductor crystals for photonics applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 1080–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Xu, C.; Mao, X.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Xu, L.; Zhuo, M.; Lin, H.; Zhuo, S.; Wang, X. Oriented self-assembly of hierarchical branch organic crystals for asymmetric photonics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 9285–9291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedorenko, E.; Mirochnik, A.; Gerasimenko, A.; Lyubykh, N.; Beloliptsev, A.; Mayor, A.; Egorov, A.; Kostyukov, A.; Burtsev, I.; Nguyen, T.; Shibaeva, A.; Markova, A.; Kuzmin, M. Molecular design of substituted boron difluoride curcuminoids: Tuning luminescence and nonlinear optical properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A 2025, 460, 116110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, V.; Chosenyah, M.; Mamonov, E.; Chandrasekar, R. Crystal photonics foundry: geometrical shaping of molecular single crystals into next generation optical cavities. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 12220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Lv, Q.; Wang, X. Low-dimensional organic semiconductor crystals for advanced photonics. Moore More 2024, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, A.; Banerjee, R.; Narayan, A. Pressure-induced magnetic and topological transitions in non-centrosymmetric MnIn2Te4. J. Phys. 2024, 36, 505807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaranjani, R.; Suvitha, A.; Garg, M.; Arumanayagam, T. Exploring linear and nonlinear optical behaviour of morpholine p-nitrophenol crystal: Computational and experimental analysis. Chem. Phys. Impact 2023, 7, 100363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Sun, D.; Dang, Y.; Wu, K.; Xu, T.; Hou, R.; Chen, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, D. (C4H10NO)PbX3 (X = Cl, Br): Design of two lead halide perovskite crystals with moderate nonlinear optical properties. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 42–16936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sudhakar, G.; Babu, D. Synthesis and characterization of piperazine nitrate monochloride semi-organic single crystal for NLO applications. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2024, 6, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Wu, H.; Xu, M.; Wang, M.; Chen, Q.; Li, B.; Hu, C.; Du, K. Halide-driven polarity tuning and optimized SHG-bandgap balance in (C4H11N2)ZnX3 (X = Cl, Br, I). Inorg. Chem. Front. 2024, 11, 5587–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffy, A.; Dhas, D.; Joe, I.; Balachandran, S. Computational study on piperazine-1,4-diium acetate using dft investigations: Structural aspects, topological and nonlinear optical properties. Cryst. Res. Technol. 2024, 59, 2300151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudhakar, G.; Babu, D. Growth and characterization of piperazine oxalic acid monochloride semiorganic NLO single crystals. Opt. Mater. 2024, 150, 115123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patent: UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA RESEARCH FOUNDATION - WO2020/163823, 2020, A2.

- Patent: JANSSEN PHARMACEUTICA - WO2022/159976, 2022, A1.

- Li, S.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, W. Synthesis and characterization of aliphatic thermoplastic poly(ether urethane) elastomers through a non-isocyanate route. Polymer 2015, 57, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patent: HIBERNIA-Chem. - BE62 1259, 1962, A [ChemAbstr, 1963, vol 59, #8616h.

- Patent: HIBERNIA-US3352913, 1961, A [Chem.Abstr., 1968, vol. 68, #12553z.

- Zagidullin, R. Aminomethylation of N-(β-amonoethyl)piperazine and its derivatives. J. Gen. Chem. USSR 1991, 61, 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 1583979: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Heptachlorepoxides: theoretical versus experimental study of the embedded samples in the matrixes of organic crystals. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2013, 76, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 881820: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 775457: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 881821: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2013. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Chapter: Experimental mass spectrometric and theoretical treatment of the effect of protonation on the 3D molecular and electronic structures of low molecular weight organics and metal-organics of silver(I) ion; In Protonation: Properties, Applications and Effects, A. Germogen (Ed.). NOVA Science Publishers, New York, 2019; pp. 1–141. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 1584573: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. A short history of SHELX. Acta Cryst. 2008, A64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheldrick, G. Experimental phasing with SHELXC/D/E: combining chain tracing with density modification. Acta Cryst. 2010, D 66, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G. Phase annealing in SHELX-90: direct methods for larger structures. Acta Cryst. 1990, A 46, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, L.; Dolomanov, O.; Gildea, R.; Howardd, J.; Puschmann, H. The anatomy of a comprehensive constrained, restrained refinement program for the modern computing environment – Olex2 dissected. Acta Cryst. 2015, A71, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Dolomanov, O.; Bourhis, L.; Gildea, R.; Howard, J.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spek, A. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003, 36, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: An Update. J. Appl. Cryst. 2012, 45, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.; Schomaker, V.; Trueblood, K. Interpretation of atomic displacement parameters from diffraction studies of crystals. J. Phys. Chem. 1988, 92, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunitz, J.; Maverick, E.; Trueblood, K. Atomic motions in molecular crystals from diffraction measurements. Angew. Chem., Int Ed. 1988, 27, 880.

- Frisch, M.; Trucks, G.; Schlegel, H.; et al. (2009) (1998), Gaussian 09, 98. Gaussian Inc, Pittsburgh [www.gaussian].

- Dalton2011 Program Package. [https ://www.dalto nprogram.org/downl oad].

- Gordon, M.; Schmidt, M. Advances in electronic structure theory: GAMESS a decade later. In: Dykstra C, Frenking G, Kim K, Scuseria G (eds) Theory and Applications of Computational Chemistry: the first forty years. Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2005, pp 1167-1189.

- GausView03 Program Package [www.gauss ian.com/g_prod/gv5.htm].

- Zhao, Z.; Truhlar, D. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Accts. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acct. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hay, P.; Wadt, W. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 82, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkert, U.; Allinger, N. Molecular mechanics in ACS Monograph 177. American Chemical Society, Washington DC, 1982, pp 1-339.

- Allinger, L. Conformational analysis. 130. MM2. A hydrocarbon force field utilizing V1 and V2 torsional terms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 8127–8134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casida, M. Time-dependent density functional response theory for molecules. in Recent Advances in Density Functional Methods 155–192, World Scientific, 1995.

- Van Gisbergen, S.; Snijders, J.; Baerends, E. Implementation of time-dependent density functional response equations. Comput. Phys. Comm. 1999, 118, 119–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirata, S.; Head-Gordon, M. Time-dependent density functional theory within the Tamm–Dancoff approximation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 314, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.; Bazzi, H. Charge-transfer complexes of 1-(2-aminoethyl) piperazine with σ- and π-acceptor. J. Mol. Struct. 2010, 983, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patent: UBE INDUSTRIES - US2012/302782, 2012, A1.

- Chankeshwara, S.; Chakraborti, A. Indium(III) halides as new and highly efficient catalysts for N-tert-butoxy-carbonylation of amines. Synthesis 2006, 16, 2784–2788. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero, M.; Rérat, M.; Orlando, R.; Dovesi, R. Coupled perturbed Hartree-Fock for periodic systems: The role of symmetry and related computational aspects. J. Chem. Phys. 2008, 128, 014110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, H.; Sommer-Jörgensen, M.; Gubler, M.; Goedecker, S. Targeting high symmetry in structure predictions by biasing the potential energy surface. Phys. Rev. Res. 2023, 5, 013189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, R. Space group P1: an update. Acta Cryst. 2005, B61, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steed, K.; Steed, J. Packing problems: High Z′ crystal structures and their Rrelationship to cocrystals, inclusion compounds, and polymorphism. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 2895–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanapriya, E.; Janczak, J.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.; Al-onazi, W.; Kanagathara. N.; Marchewka, M. Structure, vibrational characterization and SHG of the recrystallization product of L-phenylalanine from aqueous HCl solution. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Silva, M. Experimental and calculated second harmonic generation of a guanidinium salt in the solid state. Solid State Commun. 2020, 314-315, 113853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [91], T. Hrivnák, M. Medved, W. Bartkowiak, R. Zalesny, Hyperpolarizabilities of push-pull chromophores in solution: Interplay between electronic and vibrational contributions. Molecules 2022, 27, 8738. [Google Scholar]

- Potla, K.; Nuthalapati, P.; Osorio, J.; Valverde, C.; Vankayalapati, S.; Adimule, S.; Armakovic, S.; Armakovic, S.; Mary, Y. Multifaceted study of a Y-shaped pyrimidine compound: Assessing structural properties, docking interactions, and third-order nonlinear optics. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 7424–7438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Li, Y.; Ok, K. Hafnium-based chiral 2D organic-inorganic hybrid metal halides: Engineering polarity and nonlinear optical properties via para-substituent effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, X.; Yuan, K.; Chen, W. A lithium cycloparaphenylene as an emerging second-order non-linear optical molecular switch. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2023, 4, 101653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simsek, M.; Tamer, Oe.; Dege, N.; Avci, D.; Atalaz, Y. Investigation on the effect of complex formation on prominent high static/dynamic first and second hyperpolarizability of Co(II) complex including 4-chloro-pyridine-2-carboxylic acid. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Proc. 2025, 188, 109179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhoday, H.; Knotts, N.; Glaser, R. Perfect polar alignment of parallel beloamphiphile layers: Improved structural design bias realized in ferroelectric crystals of the novel methoxyphenyl series of acetophenone azines. Chem. Eur. J. 2024, 30, e202400182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Zhou, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, L.; Li, M.; Xu, J.; Wu, S.; Naumov, P.; Gong, J. Low-temperature flexibility of chiral organic crystals with highly efficient second-harmonic generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, e202416856. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, R.; Abegão, L.; Ribeiro, C.; Rodrigues Jr, J.; Valle, M.; Alencar, M. Unveiling nonlinear optical behavior in benzophenone and benzophenone hydrazone derivatives. Appl. Phys. B 2024, 130, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swamynayaka, S.; Venkatesha, K.; Harish, K.; Revanna, B.; Venkatesh, C.; Madegowda, M.; Hegde, T. Third-order nonlinear response of a novel organic acetohydrazide derivative: Experimental and theoretical approach, Opt. Mater. 2023, 139, 113826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziadi, K.; Messaoudi, A. A theoretical investigation of second-order nonlinear optical properties in push-pull π-conjugated compounds, including phenoxazine-based systems. Comput. Theor. Chem. 2025, 1244, 115049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, R.; Abegão, L.; Ribeiro, C.; Rodrigues Jr, J.; Valle, M.; Alencar, M. Unveiling nonlinear optical behavior in benzophenone and benzophenone hydrazone derivatives. Appl. Phys. 2024, B 130, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachaiyappan, S.; Kumaresan, P.; Kamatchi, T.; Nithiyanantham, S.; Logeswari, J.; Kumar, K. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP), thermodynamic properties and spectral analysis ofmethyl orange doped L–lysine sulfate (MLLS) semi organic crystals. Vietnam J. Chem. 2024, 62, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometric analysis of herbicides in dication-containing organic crystals. Anal. Meth. 2012, 4, 4360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 760142: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 882498: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Solid-state UV-MALDI mass spectrometric quantitation of fluroxypyr and triclopyr in soil. Environm. Geochem. Health 2015, 37, 557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 770390: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2012. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Chapter: Mass Spectrometric Experimental and Theoretical Quantification of Reaction Kinetics, Thermodynamics and Diffusion of Piperazine Heterocyclics in Solution, In. Advances in Chemistry Research, J. Taylor (Ed.), NOVA Science Publishers Inc. N.Y., 2019, pp.1-82.

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 775456: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Lamshoft, M.; Storp, J.; Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Gas-phase CT-stabilized Ag(I) and Zn(II) metal–organic complexes – Experimental versus theoretical study. Polyhedron 2011, 30, 2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamshoft, M.; Storp, I.; Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. CCDC 832306: Experimental Crystal Structure Determination, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. E: 792094, 7920. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, B.; Spiteller, M. Factors stabilizing the gas-phase ionic species of crystals of organic salts – Experimental and theoretical study. J. Mol. Struct. 2013, 1036, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivas, M.; Barboza, C.; Germino, J.; Fonseca, R.; Silva, D.; Vazquez, P.; Atvars, T.; Mendonc, C.; De Boni, L. Molecular structure-optical property relationship of salicylidene derivatives: A study on the first-order hyperpolarizability. J. Phys. Chem. A 2021, 125, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electric dipole moment [Debye] | First dipole hyperpolarizability, β [.10-30 esu] | ||

| αtot | 0.241711.101 | ||

| αx | 0.0 | β||(z) | 0.884883.101 |

| αy | 0.0 | β_|_(z) | -0.243294.102 |

| αz | 0.241711.101 | βxxx | 0.792536.101 |

| Dipole polarizability, α [10-24 esu] | βxxy | 0.160591.101 | |

| αiso | 0.367945.102 | βyxy | -0.456727.101 |

| αaniso | 0.464008.102 | βyyy | -0.184039.101 |

| αxx | 0.583943.102 | βxxz | 0.521545.101 |

| αyx | 0.607893.101 | βyxz | -0.478818.101 |

| αyy | 0.204121.102 | βyyz | 0.327977.101 |

| αzx | 0.162562.102 | βzxz | -0.114679.102 |

| αzy | 0.401414.102 | βzyz | 0.579436.101 |

| αzz | 0.213094.103 | βzzz | 0.625282.101 |

| α(-ω;ω) ω=455.6 nm [10-24 esu] | β(-ω;ω,0) ω= 455.6 nm | ||

| αiso | -0.373816.102 | β||(z) | -0.425821.103 |

| αaniso | 0.139823.103 | β_|_(z) | -0.184992.105 |

| αxx | -0.124242.103 | βxxx | -0.625373.104 |

| αyx | 0.283544.102 | βyxx | -0.347627.103 |

| αyy | 0.537980.101 | βyyx | -0.129018.103 |

| αzx | -0.400332.101 | βzxx | -0.624656.103 |

| αzy | 0.614927.101 | βzyx | 0.142934.103 |

| αzz | 0.671765.101 | βzzx | 0.535172.102 |

| βxxy | -0.162021.104 | ||

| βyxy | 0.217864.103 | ||

| βyyy | -0.584540.102 | ||

| βzxy | 0.355250.102 | ||

| βzyy | 0.329955.102 | ||

| βzzy | -0.517619.102 | ||

| βxxz | -0.780140.103 | ||

| βyxz | -0.659689.10-1 | ||

| βyyz | -0.112060.102 | ||

| βzxz | 0.113699.103 | ||

| βzyz | 0.191883.102 | ||

| βzzz | -0.514790.102 | ||

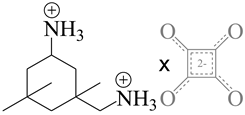

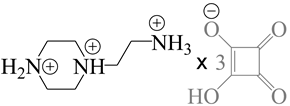

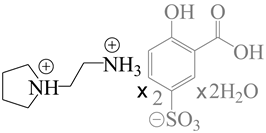

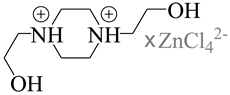

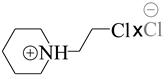

| CCCDC | Space group | Chemical diagram | Ref. |

| 760142 | Pca21 |  |

[103,104] |

| (3-(ammoniomethyl)-3,5,5-trimethylcyclohexanaminium 3,4-dioxocyclobut-1-ene-1,2-diolate) | |||

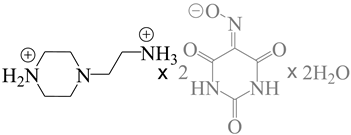

| 882498 | C2/c/Cc |  |

[103,105] |

| 9-aza-3,6-diazoniaspiro [5.5]undeca-2,8-diene bis(5-nitroso-2,6-dioxo-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyrimidin-4-olate) monohydrate | |||

| 770390 | P21/P21/c |  |

[106,107] |

| 2-(piperazine-di-ium-1-yl)ethylammonium tris(hydrogen squarate) monohydrate | |||

| 775456 | P212121 |  |

[108,109] |

| 1-(2-ammonioethyl)pyrrolidinium bis(3-carboxy-4-hydroxybenzenesulfonate) trihydrate | |||

| 832306 | Pca21/Pmna |  |

[110,111] |

| 1,4-bis(2-Hydroxyethyl)piperazinedi-ium tetrachloro-zinc(ii) | |||

| 792094 | Pca21/Pmna |  |

[112,113] |

| 1-(2-chloroethyl)piperidinium chloride | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).